Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 8

February 12, 2013

The Hieroglyphics of Vagabonds

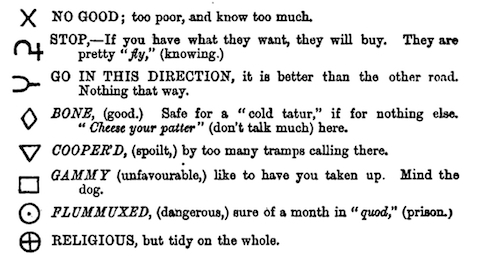

Last summer we marveled at the complexity of hobo pictographs, which we took to be a uniquely American phenomenon. But as this 1872 dictionary of slang from London makes clear, the tradition of wordless transient communication traces back to the Old World. In decidedly non-PC language, the author argues that this code was created by the semi-nomads we now call Travellers, who used markings to alert comrades to meeting spots. And as discussed in our earlier post, this mode of communication was attuned to the Western habit of processing information from left to right:

Last summer we marveled at the complexity of hobo pictographs, which we took to be a uniquely American phenomenon. But as this 1872 dictionary of slang from London makes clear, the tradition of wordless transient communication traces back to the Old World. In decidedly non-PC language, the author argues that this code was created by the semi-nomads we now call Travellers, who used markings to alert comrades to meeting spots. And as discussed in our earlier post, this mode of communication was attuned to the Western habit of processing information from left to right:

Gipsies (sic) follow their brethren by numerous marks, such as strewing handfuls of grass in the daytime at a four lane or a crossroads; the grass being strewn down the road the gang have taken; also, by a cross being made on the ground by a stick or a knife–the longest end of the cross denotes the route taken. In the nighttime a cleft stick is placed in the fence at the cross roads, with an arm pointing down the road their comrades have taken. The marks are always placed on the left-hand side, so that the stragglers can easily and readily find them.

The dictionary’s whole list of bygone slang is worth a read, too. So many great words to add to my everyday vocabulary, starting with “akeybo” and “albertopolis.”

February 8, 2013

Male Ruffled Grouses in the Mist

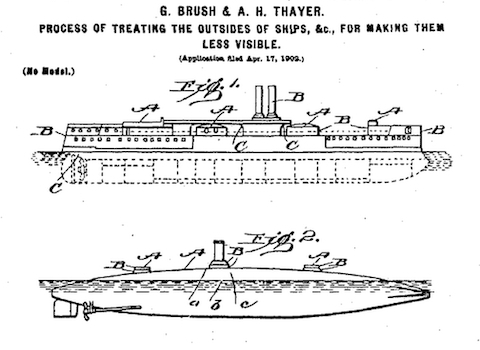

The latest post from the indispensable Camoupedia recounts the career of Gerome Brush, an artist with whom I was previously unfamiliar. His anonymity is undeserved, however, as he played an instrumental role in the advent of military camouflage; he helped fellow artist Gerald Thayer patent the first concept for the visual concealment of ships in 1902, an innovation that was later put to excellent use in the bedazzling of World War I naval vessels. There is perhaps no greater example of the practical application of artistic skill.

The latest post from the indispensable Camoupedia recounts the career of Gerome Brush, an artist with whom I was previously unfamiliar. His anonymity is undeserved, however, as he played an instrumental role in the advent of military camouflage; he helped fellow artist Gerald Thayer patent the first concept for the visual concealment of ships in 1902, an innovation that was later put to excellent use in the bedazzling of World War I naval vessels. There is perhaps no greater example of the practical application of artistic skill.

An expert of camouflage history would surely argue, however, that Thayer deserves greater credit. It was his 1898 book Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom that is considered the foundational work of this highly functional art form; I highly recommend his painting of the male ruffled grouse as the perfect way to understand the thought process that led Thayer to his eureka moment.

February 6, 2013

So Far from the Zenith

It is tough not to be saddened by the unraveling of English soccer hero Paul Gascoigne, who is currently drying out at an American rehabilitation facility after a very long, very public battle with a virulent strain of alcoholism. Like so many celebrities who we adore for their bad behavior, Gazza became trapped in a destructive feedback loop—the more he pushed his body to the limit, the more we marveled that this obviously troubled man could have once been among the planet’s foremost athletes. And the demon inside Gazza seems to have taken perverse pleasure in creating that logic-defying persona—though, inevitably, that pleasure melted into self-hate, and the cycle of addiction became ever-more firmly entrenched.

To truly appreciate the bind that Gazza now finds himself in, one must understand the heights that he reached. Doing so does not require knowledge of his sporting feats, but rather a familiarity of the perks those feats created—most notably, entree to the world of music, an aspiration of many a successful athlete filled with hubris. This extremely well-researched piece details every in and out of Gazza’s brief but energetic musical career, in which his will to top the charts was exceeded only by his irredeemable narcissism. He seemed genuinely surprised when his songs were greeted with derision more than love—it was the first time in ages that he realized that he could, in fact, do wrong. For someone with the massive ego required to succeed at the topmost levels of sport, such an epiphany is about the most unwelcome thing imaginable.

Another of Gazza’s party anthems here. You can blame the man for lack of talent, but you certainly can’t blame him for lack of spirit.

February 4, 2013

Supreme Mathematics

A great illness has swept the royal Microkhan yurts in Queens, and so I must dedicate the bulk of today to making sure the clan recuperates in fine style. Back soon with something tasty—in the meantime, please enjoy another sample from our burgeoning collection of book-related images and info.

A great illness has swept the royal Microkhan yurts in Queens, and so I must dedicate the bulk of today to making sure the clan recuperates in fine style. Back soon with something tasty—in the meantime, please enjoy another sample from our burgeoning collection of book-related images and info.

February 1, 2013

The Hidden Beauty of the Panelaks

Working-class apartment blocks—particularly those built by authoritarian governments—don’t exactly have stellar aesthetic reputations. When you think of the high-rises erected for the proletariat, adjectives such as “brutish,” “drab”, and “grim” are what immediately pop to mind. Yet it is important to remember that even when budgetary constraints and government ideology factored into the construction equation, the buildings were still the work of human beings. And humans have a penchant for finding some way to make their surroundings tolerable.

Working-class apartment blocks—particularly those built by authoritarian governments—don’t exactly have stellar aesthetic reputations. When you think of the high-rises erected for the proletariat, adjectives such as “brutish,” “drab”, and “grim” are what immediately pop to mind. Yet it is important to remember that even when budgetary constraints and government ideology factored into the construction equation, the buildings were still the work of human beings. And humans have a penchant for finding some way to make their surroundings tolerable.

That truism is well documented in the nascent International Mass Housing Image Bank, which consists largely of photographs taken in the 1970s and ’80s. At first glance, many of the buildings portrayed look positively dreary—a bit like the banged-up “estate” that the anti-hero of A Clockwork Orange called home. But take a closer look and you can see where architects made small efforts to create something elegant, even warm, despite having to work with the cheapest materials and the dourest bureaucratic overseers.

Of particular note: Images from Microkhan fave Ulaanbaatar, as well as this eerie series from Belgrade.

January 30, 2013

Deathboats, Cont’d

A treasured microblog correspondent alerted us to this heap of bad news from the maritime realm: cruise-ship crews will henceforth be receiving more lifeboat training than ever before. This decision by the Cruise Lines International Association was surely made with the best of intentions, as the organization doesn’t want a repeat of the chaos that marred the evacuation of the Costa Concordia last January. But as previously discussed on Microkhan, lifeboat drills are invariably far more lethal than the disasters they’re supposed to guard against. Let us quote once more from this damning report:

A treasured microblog correspondent alerted us to this heap of bad news from the maritime realm: cruise-ship crews will henceforth be receiving more lifeboat training than ever before. This decision by the Cruise Lines International Association was surely made with the best of intentions, as the organization doesn’t want a repeat of the chaos that marred the evacuation of the Costa Concordia last January. But as previously discussed on Microkhan, lifeboat drills are invariably far more lethal than the disasters they’re supposed to guard against. Let us quote once more from this damning report:

In 2001 the Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) studied the UK’s merchant fleet accident reports for ten years and it showed that alongside entering confined spaces and falling overboard, lifeboat practice was the most dangerous area of operation. Sixteen per cent of fatalities happen during lifeboat drill – one death in eight – a chilling statistic.

MAIB concluded that there were major three factors in lifeboat training accidents which in the studied decade killed 12 seafarers and injured a further 87. Ironically over the same period they did not record one single instance where someone was saved by a lifeboat.

The report emphasized deficiencies in lifeboat design, maintenance and training. Their findings were confined to UK waters and therefore only pointed towards the global problem, but they were backed up by the Norwegian and Australian authorities with their separate investigations coming to similar conclusions. The Norwegians estimate that globally there are about 214,000 drills a year causing 1,000 accidents and as many as half causing fatalities.

The fact that this data is so difficult for policy makers to process speaks volumes about the limits of human decision making.

(Image via Martin’s Marine Engineering Page)

January 29, 2013

Upside-Down World

There is a certain breed of non-fiction story that I call the bridge burner—a tale so damning that it ensures that the writer will never again enjoy access to a vast swath of trusted sources. A prime example would be Jon Lee Anderson’s recent “Slumlord,” in which he paints a vivid portrait of the chaos that Hugo Chavez has created in Venezuela. Although “chaos” is perhaps too mild a word to characterize the atmosphere that Anderson describes—the place he describes more closely resembles the dystopian prison in Escape from New York than a functioning nation.

There is a certain breed of non-fiction story that I call the bridge burner—a tale so damning that it ensures that the writer will never again enjoy access to a vast swath of trusted sources. A prime example would be Jon Lee Anderson’s recent “Slumlord,” in which he paints a vivid portrait of the chaos that Hugo Chavez has created in Venezuela. Although “chaos” is perhaps too mild a word to characterize the atmosphere that Anderson describes—the place he describes more closely resembles the dystopian prison in Escape from New York than a functioning nation.

There are many stellar set pieces in the story, including a lengthy exploration of life in the Torre de David, an unfinished skyscraper now inhabited by squatters and ruled by a quasi-religious gangster chieftain. But the anecdote that will always stick with me is this passage, in which Anderson visits one of the many prisons now entirely controlled by armed inmates:

A prison official drove me on a dirt road around the perimeter fence. We stopped, and I saw two tall cellblocks with scores of bullet holes in their facades; where te windows should have been there were jagged holes, and a large group of shirtless, rough-looking men looking down at us. A thick black line of human excrement ran down an exterior wall, and in the yard below was a sea of sludge and garbage several feet deep. “We can’t hang around here,” the official said. “If we stay too long, they might shoot at us.” As we drove off, he explained that there were only six guards at a time inside the prison. The inmates allowed one handpicked guard to retrieve dead bodies they left there.

I very much doubt that Anderson will get any sit-downs with Chavez’s successor. But he has placed himself in excellent position to report on the nascent opposition to the Chavista “dynasty,” which seems to be taking shape outside of Venezuela’s borders.

(Image via Caracas Chronicles)

January 25, 2013

Knife Tricks

The effervescent young lady above worked for an early manufacturer of handheld metal detectors. Here she shows a Congressional panel how the skyjackers of the the late 1960s managed to sneak knives aboard planes, even when selected for manual frisking by airline employees.

The effervescent young lady above worked for an early manufacturer of handheld metal detectors. Here she shows a Congressional panel how the skyjackers of the the late 1960s managed to sneak knives aboard planes, even when selected for manual frisking by airline employees.

From my very nascent collection of skyjacking-related images, tied into the forthcoming release of that project y’all will be surely sick of hearing come June. Apologies—at least until there’s only a month to go before publication, I’ll try and limit these posts to one-per-week. Deal?

January 24, 2013

The Unapologetic Cipher

I’m midway through David Remnick’s biography of Muhammad Ali, which is pretty much as stellar as you would expect. Yet there are times when I wish the narrative would instead focus on the tragic figure of Sonny Liston—what can I say, I’m attracted to characters who will never be universally adored, and who perhaps take some modicum of pleasure in that fact. The snippets of Liston backstory that the book provides motivated me to delve more deeply into the man’s bittersweet arc. The most enjoyable contemporary story I’ve uncovered so far is this one, from a 1962 issue of Life. It’s hackneyed, for sure, especially in its structure; like every other account of Liston’s rise from convict to contender, it uses purplish prose to explore his moral fitness to wear the heavyweight crown. But the piece also contains plenty of gems based on interviews with the famously tight-lipped Liston; my favorite concerns the man’s pre-fight nutritional regimen:

When in hard training for a fight he eats only once a day. “When you get in the gym and start jumping the food hits the top of your stomach and sticks there,” he explains. His one meal never varies—steak eaten nearly raw. When he goes to camp he brings along 50 or 60 steaks packed in dry ice. “That’s why they have training camps,” he explains. “They take away women and feed you raw meat and this puts you in a fighting mood. It makes you angry and brings up the evil inside of you, so that when the man in your corner says, ‘Go in and kill ‘em,’ you do.”

For some reason, the one Liston bio written during his heyday is out-of-print and ludicrously expensive. If anyone has a copy they can loan out, I’ll send you a signed copy of Now the Hell Will Start.

January 22, 2013

The Talented Mr. Quan

The Phocea is one of the world’s largest superyachts, checking in at an impressive 75-meters in length. It has also proven to be a monkey’s paw of sorts, as great misfortune has befallen its ultra-successful owners:

The Phocea is one of the world’s largest superyachts, checking in at an impressive 75-meters in length. It has also proven to be a monkey’s paw of sorts, as great misfortune has befallen its ultra-successful owners:

The Phocea was built in Toulon in 1976 for yachtsman Alain Colas who called her Club Mediterranee. She competed in a Trans-Atlantic race for Colas, came second. Colas disappeared at sea the following year.

In 1982 French business man Bernard Tapie bought Phocea and had her converted to a private yacht at great expense. Tapie christened her Phocea, in honour of the Phoenicians who founded Marseilles where she was refitted.

Tapie later went to jail over corruption offences and in 1997 French Lebanese socialite Mouna Ayoub purchased the yacht – after she sold one of her diamonds, the largest yellow diamond in the world, and several other lesser jewels to pay for the US$17 million refit.

At some point after Ayoub’s sell-off of assets, the yacht fell into the hands of a man who goes by Pascal Anh Quan Saken. Quan claims to be the founder of the Billionaire Yacht Club, as well as the holder of an MBA from the “University of Minneapolis.” (Full curriculum vitae here.) But the PNG Post-Courier asserts that he is actually a trafficker of contraband who has no real ownership of the Phocea. In fact, Quan seems to have registered the ship in Malta by submitting forged documents; as a result, the Phocea was impounded by officials in Vanuatu, some of whom have been accused of illicit dealings with Quan. (Though he was apparently born in Vietnam, Quan appears to hold a diplomatic passport from Vanuatu.)

Quan is rumored to have flown to Papua New Guinea, to ask the government there to register the Phocea so it can be liberated from Vanuatu. I hope someone in Port Moresby asks him how, exactly, he got his hands on the yacht. My hunch tells me that it was exchanged for either arms or drugs, which is why there is no legit record of its sale. On a planet where large financial transactions are increasingly likely to come to the attention of the authorities, old-fashioned bartering may be the way of the future on the black market.

Check out a full list of stories on L’affaire Phocea here.