Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 30

December 19, 2011

This is Your Wake-Up Call

The realist in me is resigned to the fact that little will change for North Korea's long-suffering citizens in the wake of Dear Leader's demise. But upon learning the news late last night, I immediately thought of a strangely optimistc scene from Barbara Demick's Nothing to Envy, one set in the immediate aftermath of Kim Il-sung's death in 1994. It involves a university student named Jun-sang, who always considered himself an ardent believer in North Korea's greatness. But then something unexpected happened one July day in Pyongyang:

In the courtyard, nearly three thousand students and faculty were lined up in formation, ranked by their year, major, and dormitory affiliation. The sun beat down with full force, and they were sweating in their short-sleeved summer uniforms. At noon a disembodied female voice, tremulous and sorrowful, came booming through loudspeakers. The loudspeakers were old and produced scratchy sounds that Jun-sang could barely understand, but he picked up a few words&mdash"passed away" and "illness"—and he grasped the meaning of it all from the murmur going through the crowd. There were gasps and moans. One student collapsed in a heap. Nobody knew quite what to do. So one by one each of the three thousand students sat down on the hot pavement, heads in hands.

Jun-sang sat down, too, unsure of what else to do. Keeping his head down so nobody could read the confusion on his face, he listened to the rhythm of the sobbing around him. He stole glances at his grief-stricken classmates. He found it curious that for once he wasn't the one crying. To his great embarrassment, he often felt tears welling in his eyes at the end of movies or novels, which provoked no end of teasing by his younger brother, as well as criticism from his father, who always told him he was "soft like a girl." He rubbed his eyes, just to make sure. They were dry. He wasn't crying. What was wrong with him? Why wasn't he sad that Kim Il-sung was dead? Didn't he love Kim Il-sung?

Here's to hoping that more than a few young North Koreans are experiencing similarly jarring epiphanies today.

December 16, 2011

"Today's Most Devastating Polemicist"

I was reluctant to read my first Christopher Hitchens work, a thin volume that bore the decidedly loaded title The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice. I figured the flap copy told me all I needed to know about the author's point of view, and that he'd written the polemic more as an exercise in contrarianism than a genuine attempt to alter our view of a then-living saint. I mean, who could possibly pick on a woman who had dedicated her life to helping the sick and needy?

Yet I gave The Missionary Position a go, and I'm so glad I did—the book is a masterclass in how to counter emotion with logic, a feat made possible by Hitchens' legendarily deft way with words. I didn't come away from the experience thinking that Mother Teresa was some sort of monster, but I did see her as thoroughly human—which, caustic title aside, was really Hitchens' point. This line, in particular, is something that I've ended up turning to again and again, as perhaps the most insightful passage ever written about our species' penchant for cloaking our true intentions:

All claims by public persons to be apolitical deserve critical scrutiny, and all laims made by those who affect a merely "spiritual" influence deserve a doubly critical scrutiny. The naive and simple are seldom as naive and simple as they seem, and this suspicion is reinforced by those who proclaim their own naivety and simplicity. There is no conceit equal to false modesty, and there is no politics like antipolitics, just as there is no worldliness to compare with ostentatious antimaterialism.

Above all, Hitchens was a true pro—a man who banged out top-notch copy with such stunning rapidity that he made all other writers seem like layabouts. In life he was envied; in death he'll be missed.

December 14, 2011

Above the Allegheny

Hanging out in the great city of Pittsburgh today, doing some Wired work and hoping to catch up with an archaeologist pal of mine. Back shortly.

December 13, 2011

Days of Quiet Rage

In exploring the nuttiness of the Symbionese Liberation Army as part of my book research, I came across this bygone Congressional document: a transcript of a 1976 hearing entitled "Threats to the Peaceful Observance of the Bicentennial." The artifact's real gold is not to be found in the back-and-forth between various Congressmen and witnesses, but rather in the appendices that catalog pamphlets from the protest movements of the day. This was a difficult period for the organizers of popular discontent, given that both Vietnam and Watergate had vanished as rallying points. The focus of their ire was instead something that should sound quite familiar to contemporary ears: the concentration of wealth in very few hands, a situation made possible by the overly cozy relationship between industry and politics. It's instructive to check out the typical rhetoric these protestors employed, to note the similarities and differences with today's Occupy movement:

We've been robbed of the fruits of our labor by that class of parasites that runs the government and all of society for their profits and luxury. And even the gains of our struggle, like our unions, they try to turn against us. What is this "common interest" between us and the owners? For 200 years our hard work and all it has produced has carried a small handful of bosses and enabled them to live in riches and luxury, while this constant drive for profit has held back our labor from being used to meet the needs of the millions. Nothing has ever been handed to us by them, everything we ever got we had to fight for, even in so-called good times…

Now in this 200th year the bosses and politicians are hoping they can cool off our anger and struggle against these conditions by trying to play off our genuine feelings of pride in our hard work and its accomplishments. This is what's really the point of their Bicentennial blitz and the calls for us to come to a July 4th festival in Philadelphia to celebrate life under this system which enables them to live like kings.

The bicentennial protestors' core sentiment has a lot in common with what drives the Occupiers—the feeling that the wealthy few are totally oblivious to the increasingly difficult lives of the many. (See here for a bit of street-theater that would be right at home in Zucotti Park.) But take heed of the explicit notes of class conflict that echo the rhetoric employed by the totalitarian regimes of the '70s—check out, for example, that line about labor being "held back" from providing for the masses. That sort of lingo obviously seems archaic in a post-Berlin Wall world, which is why—at least at its most successful—the Occupy movement has replaced broad ideology with heartfelt personal narrative. The movement's participants may not convey a politically coherent message, but to criticize that aspect of the protests is to miss the point entirely; the participants are the message.

The other major difference between 1976 and today: the protestors back then were apparently really terrible artists.

December 9, 2011

Legend of the Eggs

I am regrettably a few days late in noting the untimely passing of Vasily Alexeev, the famed Soviet athlete who dominated the sport of weightlifting for most of the 1970s. Alexeev was an object of great fascination in the West, for he seemed to embody our deepest fears about the world behind the Iron Curtain: that somewhere east of Leningrad, the Communists were breeding supermen who would help the "Evil Empire" win the future. When we cast our eyes upon Alexeev's bear-like frame and prodigious gut, we stared into the Cold War abyss. And, per Nietzsche, the abyss stared back and told us we were weak little girlie men whose great cities would soon be overrun by the Soviet hordes.

Yet we were also sucked into the mythology surrounding Alexeev's physical prowess, as if the man himself emitted a gravitation field on par with that of Saturn. This was most evident in the rumors surrounding Alexeev's appetite, particularly in regards to eggs. In one Canadian obituary, his pre-Olympic breakfast was reported as 26 eggs. Elsewhere, he is credited with devouring a 36-egg omelette, though more contemporary accounts detail a pre-noon diet of a dozen eggs plus an entire leg of lamb. (There are additional reports that he enjoyed his eggs whipped in milk.) Yet the reality, as observed by a young Tony Kornheiser, was somewhat more prosaic: At a New York deli, Alexeev was observed eating a mere "two orders of ham and eggs, five glasses of orange juice, and God knows how many rolls."

I feel no sense of shame in asserting that I could have done likewise in my eating heyday. Though, obviously, Alexeev's feats of strength have always been well beyond me. His water-skiing prowess, too.

December 8, 2011

Working the Phones

You'll have to make do with some Filipino disco today, since I'm absorbed in reporting for multiple projects. Just spent the better part of the morning trying to track down an amnesia victim, only to be frustrated by his overprotective 78-year-old mother. May have to Irish up this coffee to push through that early-in-the-day disappointment.

December 7, 2011

The Popular Cannon

This blog has occasionally featured my half-baked ruminations on the symbolic power of tangible objects. I've always been puzzled by the extraordinarily high values that people can ascribe to non-personal items, as if those items' absence or destruction might somehow affect the intangible ideas they embody. A great case in point is the developing spat over the fate of this cannon, currently a tourist attraction at the Arsenal of Brest in northwestern France. The weapon was taken from Algeria in 1830, and now the Algerians want it back. The cannon has deep sentimental value for both sides, as this pro-Algerian news item makes clear:

Merzoug Baba, a bronze cannon of twelve tons built in 1542, seven meters long with a range of about 5 km, defended Algiers for more than two hundred years, before being taken by the French in 1830 during the colonization.

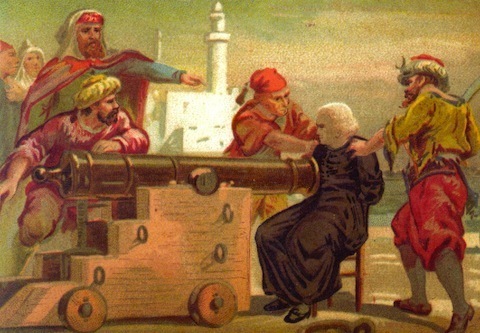

The French have renamed it the "Consular", in reference to two French consuls; missionary Father Jean Le Vacher, consul of Algiers, who was attached to the muzzle of the cannon and shredded in July 1683 (see painting above), in retaliation for the bombing of Algiers by Admiral Duquesne who claimed that all the Christian slaves be released, and the consul André Piolle in 1688 during a similar attack committed by Marshal Jean d'Estrees against Algiers.

For the Algerians, this gun is more than a symbol, it was the most powerful in the Mediterranean, and had defended Algiers for two centuries. It must find its place in Algiers by July 5, 2012 after 182 years of absence.

There's clearly a lot of bad blood between these two nations, for screamingly obvious reasons. Yet I personally find it odd that the two former enemies would engage in such a heated diplomatic tussle over an antique cannon. This actually strikes me as a case where the vast majority of French and Algerian citizens could care less about the matter, but jingoist voices are always heard loudest in the halls of power.

Good luck to them in sorting this all out. Might I propose a winner-take-cannon soccer match, with the loser getting the television revenues as a consolation prize?

December 5, 2011

Betting on the Wrong Horse

When you're in the midst of agonizing over the relative merits of two competing technologies, the choice can seem oh-so-important. I still have vivid memories, for example, of the raging household debate that surrounded my family's selection of a first computer—the Mac and the Amiga both had points in their favor, after all. But in the end, there are no grave consequences if the wrong decision is made—you lose a small-yet-meaningful chunk of money, you learn some lessons, and you join the vast hordes in relying upon the winning technology.

But for one legendary Congolese musician, Papa Ntita Albert, the decision to go with one technology over the other effectively stunted his career. The sad tale of a mistime gambit forms the heart of this excellent yarn from Voice of America's "African Music Treasures" series:

Encouraged by a wealthy patron, who paid for his plane tickets to Kinshasa and financed a long stay in the capital, Ntita Albert recorded a half-dozen singles for the Bukebi-Kebi label; singles that he hoped would relaunch his career. The tracks were laid down by the Pere Buffalo at the Studio Renapec in downtown Kinshasa, and Papa Albert returned to Mbuji Mayi in 1982 with a few thousand 45s.

Unfortunately, Papa Albert's vinyl investment coincided with the arrival of the cassette tape in Mbuji Mayi. He never sold his stock of 45s and his career never regained its momentum. For the last several decades Ntita Albert has continued to perform, making occasional appearances on local television programs, or at local events, but he has not played outside of Mbuji Mayi since 1982.

As the piece goes on to show, Papa Albert ended up stuck with bags and bags of unsold 45s, which he eventually shares with the writer. I can only imagine how tough it must be for the musician to see those records lying around his house, providing a constant reminder that his downfall was caused not by a lack of musical skill, but by a single bad bet on technology. How blessed are we not to have to feel likewise when we spot a bricked Toshiba Gigabeat in the back of some closet.

December 2, 2011

Men Rule Everything Around Me

Interesting little tidbit in this excellent profile of Lady Carol Kidu, Papua New Guinea's only female legislator, who is pushing a controversial bill to allocate a set percentage of parliamentary seats for women:

Kidu knows that if the bill fails then when she retires next year PNG will likely become the 10th nation in the world without a single elected female representative. Six of those would be Australia's near neighbours in the Pacific, the others being Nauru, the Solomons, Micronesia, Palau and Tonga (where the King has installed one unelected woman in the Parliament).

Curious about the other four entires on that list, I tracked down the complete figures here. It's not the easiest dataset to parse, in part because the table doesn't mention which nations have quotas for female political participation. But there is plenty to chew over nonetheless, and not just the fact that the United States is tied with Turkmenistan. There are, in fact, several global powerhouses that rank far lower than the U.S., including Brazil and Japan (though, in the former case, a female president now reigns). And there are some mysteries at the top of the list, too, such as Seychelles, which doesn't have an official quota system (though political parties there are aware of the need for more female candidates).

In Papua New Guinea, the opposition to Kidu's bill basically boils down to a libertarian argument—that the government has no right to dictate the will of the people. But this ignores the fact that local votes are often controlled by power brokers such as tribal chiefs; to assume that the political playing field is level from the get-go is laughable. Quotas may seem heavy-handed, but sometimes extraordinary measures are necessary to break up what amount to power monopolies. And though feminizing Papua New Guinea's national politics will not magically make the country's problems disappear, it's worth the experiment. Anything is better than maintaining the status quo.

(Image via Daniel Pilar)

December 1, 2011

The Evolution of Bomb-Squad Armor

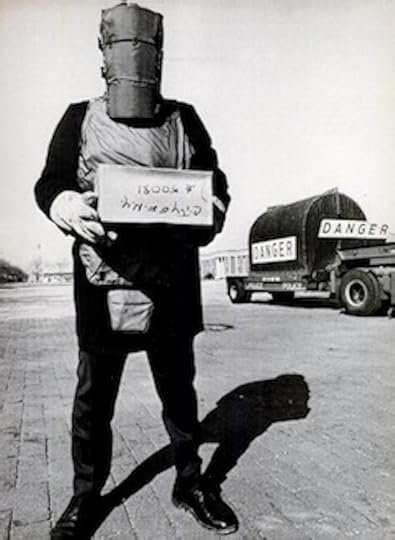

One thing my book research has taught me is that America used to have a serious problem with bombs. Every time I delve into the news archives from the early 1970s, I come away amazed at number of stories involving homemade explosive devices going off a nightclubs, bus depots, and Mafia social clubs. And I'm equally floored by the major cojones exhibited by the bomb-disposal experts who handled unexploded ordnance in that era, mostly because they operated with the most rudimentary of armor.

Though Kevlar was invented in the mid-1960s, it didn't became a standard component of armor until much later. Bomb squad members in the early 1970s thus had to make do with the get-ups you see above, which consisted of material no tougher than the standard military flak jacket. Note the shoes, in particular; bomb shrapnel is a great threat to the most distant human extremities, yet members of the New York City Police Department's explosives disposal squad did their dirty work in wingtips. (To their credit, though, the armor's designers installed a flap to protect the privates, another area frequently damaged by flying debris.)

This 1973 Navy study (PDF) actually vouches for the effectiveness of the armor, though you have to read closely to understand the important caveat: the armor only really worked when combined with a blast shield. Yet in reading contemporary accounts of early 1970s' bomb-disposal work, I have rarely come across descriptions of such shields; it seems the cops of that era liked to roll the dice.

Since then, of course, great thought has gone into developing the massive suits or armor that we're all familiar with today. The first great advance came in 1976, with this "personal blast protection armor." And the equipment has only gotten bulkier from there.

Tough to move around in, sure. But vastly preferable to the options in the early 1970s—or, for that matter, in 1922.