C.L.R. Peterson's Blog, page 5

September 8, 2020

Netherlands, ahoy!

As I continue to trace my characters’ journeys, I discover new places or interesting new things about places I thought I knew—including the Netherlands.

Since many of us are limited in our travels now, it’s a perfect time to travel back in time to experience life in this part of the world in the late sixteenth century.

I’m highlighting a historical novel with a history of its own:

The Dove and the Rose was written more than two decades ago by Ethel Herr, one of my early fiction mentors. I recently re-read this novel, whose success inspired me to write historical fiction dealing with the consequences of the Protestant Reformation in an often-overlooked part of Europe—in this case, the Netherlands.

Although romance is an important aspect of this story, the historical context is key to understanding the struggles of the main characters. The author does a commendable job of providing background information (maps, historical background, a glossary of Dutch terms).

Central to the plot are the many competing expressions of Christianity in the late 1500s. Conflicts between these groups escalated as rulers at all levels became involved. Often, common people suffered most.

This novel doesn’t sugarcoat the suffering produced by these conflicts, but it left me admiring the heroism of several characters (even though they were complex, flawed people). I enjoyed the story and being transported to this unfamiliar setting—an engaging, off-the-beaten-track read.

Do you have a hidden gem historical novel to recommend to other readers?

The post Netherlands, ahoy! appeared first on C.L.R. Peterson, Author.

August 8, 2020

Wish you were a genius like Michelangelo?

When you hear the name of Michelangelo, what comes to mind?

Painter of the Sistine Chapel in Rome?Sculptor of the monumental David statue, symbol of Renaissance Florence?Architect whose vision led to the completion of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome?Poet who wrote more than 300 sonnets and madrigals about death, shortness of life, faith, love, etc.?

Michelangelo’s creations showed his genius,

but make us wonder*:

Was he born with these artistic gifts?If not, how did he develop his talent?How did he come up with his revolutionary new approaches to sculpture, painting, and architecture?Was Michelangelo a model of how to develop or become a genius?

Was there a downside to his genius?

Powerful people virtually forced him to work on projects and in places he wouldn’t have chosenAs a rock star of his era, he attracted fans, but had few true friends. His peers (artists like Raphael and Bramante) were jealous of his success.

Did his success make for a happy life?

Michelangelo was a complex character with a complicated life.

Although he created masterpieces demanded by popes, he belonged to a group of independent-thinking lay people, called spirituali, who embraced some of Martin Luther’s religious ideas, such as emphasis on the Bible as the only source of truth, and faith as the only way to salvation.Did he secretly follow Luther? We can’t know, but his spirituality shines through in this passage from a poem he wrote 10 years before he died:

“Neither painting nor sculpture will be able any longer to calm my soul, now turned toward that divine love that opened his arms on the cross to take us in.”

(from Sonnet, poem 285, 1554, translated by James M. Saslow)

*For answers to these questions, I recommend The Giant, a recent novel by Laura Morelli, which approaches the complexities of Michelangelo’s personality through his friendship with fellow artist, Jacopo Torni. In contrast to Irving Stone’s Agony and the Ecstasy, which covers Michelangelo’s life story (1495-1564) in depth, The Giant is told from the perspective of Jacopo Torni, and focuses primarily on Michelangelo’s creation of the David statue (1501-1504).

This month, I’m excited to share an interview about The Giant with the author, Laura Morelli.

Q: Was there an event that triggered your decision to tell the story of Michelangelo’s creation of his monumental David statue?

Laura Morelli: The Giant: A Novel of Michelangelo’s David, was originally intended to be a nonfiction book in the spirit of Ross King’s Brunelleschi’s Dome. But then I put the project away for nearly twenty years! It was only after I pulled my old book proposal out of a drawer that I knew it was meant to be a novel instead.

For three decades, the story of Michelangelo’s David pestered me nearly as much as real-life Jacopo, the protagonist of THE GIANT, pestered his genius friend. I kept putting this project away, but it wouldn’t let me go. The story kept coming back to me over years.

Q: How did you discover a new angle that hadn’t been written about?

LM: I have always wondered what it was about Michelangelo’s David that changed the course of art history. How did that happen? How did a single man–and a single sculpture–have the power to transform the course of art history? As I began to look for answers in traditional art history research, I discovered a drama so incredible that you could not make it up! (Well, OK, I made a few things up… It’s a novel.)

As I looked for the right person to tell the story of Michelangelo’s gigante, I came across historical references to a Florentine fresco painter called Jacopo Torni, also known as L’Indaco.

The sixteenth-century art historian Giorgio Vasari tells us that L’Indaco lived “in close intimacy” with Michelangelo, and that Michelangelo found L’Indaco the funniest and most entertaining of his friends. We also know that Michelangelo invited L’Indaco to work with him on the Sistine Chapel in 1508. According to some sources, it was a friend who convinced Michelangelo to return to Florence to take on the David commission in 1501, and I like to think it was L’Indaco.

Michelangelo is one of the most notoriously temperamental artists in history, and I wondered about this relationship of seeming opposites. It is this push and pull of two creative friends, in combination with the creation of two of the most seminal works of art history—the David and the Sistine Chapel ceiling—that drew me to this story and made me want to explore this complicated friendship further.

Q: What sources helped you fill in the details and context for this story?

LM: I always start with primary sources—things written at the time. For the Italian Renaissance, there are so many great primary sources! My personal favorites are legal accounts. Sometimes the laws are so weird! And consider that laws are only made when someone does something considered egregious at the time; it really helps you understand what a culture valued and what they condemned.

For The Giant, I started with the fascinating primary accounts of Michelangelo’s David, then added the scant yet tantalizing known details of Jacopo Torni’s life.

Q: Did you discover any surprises while researching this novel?

LM: We know just enough about Jacopo to make him an incredibly interesting character: he was in Michelangelo’s inner circle, he worked on the Sistine ceiling, he may have invented a way to inhibit mold on fresco, he was funny, lazy, a practical jokester. Giorgio Vasari gives us one anecdote to hint at the complicated friendship he had with Michelangelo. Little more. What an interesting character! He’s the perfect protagonist for a historical novel, especially woven into the rich tapestry of the known facts around the creation of Michelangelo’s David.

Building out Jacopo’s character gave me the chance to delve into parts of Florentine history I didn’t know about before—life in the taverns, Renaissance card games, and (spoiler alert) what it was like to be in jail in 16th-century Florence. There were lots of fascinating surprises down each of those research rabbit holes!

Q: How much did you have to deviate from history to create a satisfying story? (What’s the ratio of fact to fiction?)

LM: For me, the fun of historical fiction is taking the facts as far as they go, then realizing there’s a whole lot of stuff we don’t know. It’s like putting together a complex jigsaw puzzle with a bunch of missing pieces. You make up the rest. For this period, there are so many rich sources that there was always at least a hint to get started.

Q: How did the events and changes happening at this time in Renaissance Florence impact the lives of your characters?

LM: It’s incredible to realize that while Michelangelo was sculpting his David, just down the street, Leonardo da Vinci was painting his famous Lisa. You can’t make that up! And that’s just one small thread in the rich tapestry of Renaissance Florence.

Q: What were the most challenging aspects of writing your novel?

LM: Honestly, this book was a long slog! Whenever you write about a real historical person—especially a “giant” like Michelangelo—you feel the burden of responsibility to do justice to your subject. I thought about this a lot as I was writing.

Q: What did you enjoy most about writing The Giant?

LM: I enjoyed living vicariously in Florence circa 1500 for many years—if only in my head.

Q: What do you hope readers will take away after reading The Giant?

LM: My readers tell me they read historical fiction to transport themselves to the past—and to learn something new. They don’t want to be hit over the head with a textbook but they want to come away smarter. I hope they also come away entertained and enriched by an armchair trip to Renaissance Italy.

Reader, would you want to be a genius if you had to go through what Michelangelo experienced?

The post Wish you were a genius like Michelangelo? appeared first on C.L.R. Peterson, Author.

July 4, 2020

Detour off the beaten track…to Wales

LeAnne Hardy’s new novel,

Black Mountain

LeAnne Hardy’s new novel,

Black Mountain

Topics off the beaten track intrigue me, and a new novel, Black Mountain, fits the bill for its location as well as the story. Here’s why I enjoyed it:

It took place mainly in rural Wales (not London, Paris, Rome…)Set in the early phase of the Reformation in England, it focused not on Henry VIII or his court, but on how King Henry’s Reformation affected the lives of common peopleThe protagonist was a witchThe suspense propelled meThe characters are well-drawn and unique

The author, Leanne Hardy, was kind enough to answer a few questions about her story, and my interview with her follows.

Black Mountain is the third book in your Glastonbury Grail series. Does this novel work well as a stand-alone, or do you recommend reading Glastonbury Tor and Honddu Vale first?

Leanne Hardy: Readers of the first two books will enjoy becoming reacquainted with old friends, but Black Mountain works fine even if you jump in here.

What led you to sixteenth-century Wales as the main setting for this novel?

LH: It started with visiting the museum at Glastonbury Abbey in Somerset, England, and learning about the dramatic events surrounding the closure of the abbey in 1539 under King Henry VIII. That became the setting for Glastonbury Tor. At the end of that book my main character, Colin, returns to his home in Wales, and the other books follow from there.

Major changes were going on in the world during the era of this novel. How did these changes impact the lives of peasants, nobles, and clergy in your story?

LH: You’re right; the changes were revolutionary. Most of the books I have seen set at this time concern themselves with events at court, including Henry’s multiple marriages. (Wolf Hall, The Other Boleyn Girl, etc) I was more interested in ordinary people.

This is the time of the early English Reformation, and the lines between Catholic and Protestant were not yet clearly drawn. Good people on both sides sincerely sought God; corrupt people on both sides took advantage of unrest for personal gain—not the least of which was Henry himself, who was more interested in justifying his divorce of Queen Katherine, who had failed to give him a son, than he was in biblical doctrine.

Henry closed down all the monasteries and appropriated their wealth for the crown, more accurately, he squandered it to win friends. Those monasteries ran the soup kitchens and travelers’ lodgings of the time. And now they were gone.

Peasants were expected to follow the lead of “their betters.” Owning a copy of William Tyndale’s English translation of the Bible could draw severe punishment, even death. As one of my readers of Glastonbury Tor commented, “It sounds like a police state!” It was.

Which historical figures did you include in your novel?

LH: Henry VIII, of course, although he never appears in person. Throughout the trilogy characters make reference to various historical characters and events at court. Those are “current events” for them. The officials Henry sent to dissolve the abbey in Glastonbury Tor are historical. I used the names of actual monks who were there at the time, including those who were arrested at the end. But the personalities I gave them were entirely fictitious, and by the time I got to Black Mountain all the characters were invented, although they seemed very real to me.

Where did you discover the details of life in this time?

LH: Thanks to inter-library loan, I read more than thirty books about the time, the setting, life in monasteries, etc. Even so, after the first book was published, I discovered information that revealed a geographical error that I had no choice but to carry over to future books.

The second book in the series was set in Wales. I was frustrated that all the books I found in the US lumped Wales in with England after the conquest in the thirteenth century. I was pretty sure the Welsh did not all instantly think like Englishmen.

When I traveled to Wales for research and stayed with college students in Cardiff (fabulous experience!), they arranged a library card I could use. The Cardiff library had two bookcases full of books on Wales from the Welsh point-of-view! Before I came home, I bought the history written by a raving Welsh nationalist. I figured he would give me the best perspective on how my characters would really feel.

By the time I started Black Mountain, I had a pretty good handle on sixteenth-century life in Britain, but when my beta readers asked for more information on Teg’s journey, I had to do a lot of digging about the places and cultures she passed through. Fortunately, the most significant were places I had visited and knew something about already.

What were the most challenging aspects of writing this novel?

LH: When I started, I was unsure about attempting to write first person of two different points-of-view, but then I realized that a bitter old woman and a blooming bride were enough different that it was worth a try. I think it worked. Other than that, the most challenging aspect was sticking with it through years of interruptions and distractions.

What did you enjoy about writing this novel?

LH: The surprises. By this time I knew my characters pretty well. They directed where the story should go, and that is always so much fun.

What do you hope readers will take away after reading Black Mountain?

LH: Teg thinks she knows what Christianity is about. After all, her father was a priest and prior of the local abbey. (Yes, you read that correctly.) She is bitter and wants nothing to do with the church, but she has never met Jesus Christ, the owner of the mysterious cup whose power she wants to control. My hope is that readers will put aside what they think they know and meet Jesus.

Readers, I hope you’ve enjoyed this journey to 16th-century Wales! Can you share an experience or knowledge of Wales?

The post Detour off the beaten track…to Wales appeared first on C.L.R. Peterson, Author.

May 29, 2020

Wanderlust Then and Now

First voyage around the World, by Antonio Pigafetta

First voyage around the World, by Antonio PigafettaImagine you lived in the 16th century and dreamed of seeing new sights—just like we do today, especially if we’ve spent more time at home than we’d have preferred.

If you were a 16th-century European, how would you learn about distant places?

While we can look online or browse books, photos, or films to find out what we’re likely to experience, our ancestors had few options:

Fortunate listeners at a village inn might hear stories from returned travelersLiterate people might have access to guides for pilgrims—to places like the Holy Land, Greek holy sites, or the Spanish pilgrim route to the shrine of St. JamesOnly the most privileged and rich (kings, popes, and their associates) had access to travelers’ journals (described below)

Why did people travel?

Merchants, explorers, diplomats, soldiers, pilgrims, and missionaries — all needed to travel to succeed in their careers and religious callings

What appealed to readers about travel writing?

Wonderful, terrible, or amazing new information about the sights and peoples of the world stimulated people’s curiosity, spirit of adventure, quest for riches, and religious passion, and also allowed people to travel vicariously from the safety of their homes.

What did they learn? A few highlights from this vast genre:

Kublai Khan meeting Marco Polo

Kublai Khan meeting Marco PoloMarco Polo—the son of a Venetian merchant, his Book of the Marvels of the World described his travels through Asia between 1271 and 1295, and his experiences at the court of Kublai Khan. Even though this book had to be hand-copied (no printing press yet!), it became wildly popular. His description of Japan provided a goal for Columbus in his 1492 journey; his identification of spice-producing areas encouraged Western merchants’ new ventures; European explorers of the late 15th and the 16th centuries used the abundant new geographic information he recorded during their voyages of discovery.

Christopher Columbus—after his (1492) first voyage to the West Indies, he wrote a letter to King Ferdinand of Spain describing the wonders of the island he called Hispana: many great rivers and high, beautiful mountains; many trees bearing fruit; full of spices, cotton, aloe-wood, gold, and metals (except iron). Inhabitants were fearful, reverent, and friendly, and open to conversion to Christianity

Niccolò de’ Conti (1395–1469)–an Italian merchant, he explored India, China and Indonesia from 1419 to 1444. He wrote an account of his travels, including details about the Spice Islands, huge ships (1000-2000 tons) built in Asia, and confirmed it was possible to sail around the tip of Africa.

Antonio Pigafetta (c. 1491 – c. 1531)–a Venetian explorer who traveled with Magellan in the first circumnavigation of the globe. He wrote Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo (1524) (The First voyage Around the World). Of the two hundred thirty-seven men who left Spain, he was one of only eighteen who returned. His account mentions: sharks, fierce storms, cannibals, giants, near starvation, wild boars, crocodiles; execution, robbery by natives, near drowning, and the killing of Magellan in 1521 by islanders of Matan.

Giovanni Battista Ramusio (1485–1557)–a Venetian geographer, he didn’t travel widely but compiled Navigationi et Viaggi (“Navigations and Travels”) (1555-1559), a large collection of explorers’ first-hand accounts of their travels around the world, the first one of its kind. They were translated into Italian from Spanish, French, and Latin, plus some from works never before published.

Religious pilgrims wrote guides to the Holy Land and Greek pilgrimage sites

Missionaries wrote about lands they visited

Which of these accounts would have motivated you to travel?

Would you have wanted to travel if your options were ships, horses, mules, camels?

How about if you had no resources but your own two feet?

Would you have risked attacks by robbers or pirates along the way?

These brief examples reveal that however enticing travel seemed, it was difficult for most people in the 16th century. As I research my characters’ travel options for my upcoming novel, I constantly admire the courage and strength of people who lived 500 years ago.

Have you recently wished you could get away and see a new or faraway place? What inspired you to visit?

The post Wanderlust Then and Now appeared first on C.L.R. Peterson, Author.

April 26, 2020

When Contagion Strikes

Compassion, cruelty, or escape? Why do people act in such different ways when confronted with threats of contagious disease? Ignorance of a disease’s cause sometimes led to extreme reactions. Spiritual beliefs also played a role. Both Catholic and Protestant traditions reveal merciful as well as cruel responses. We’ll look back over the centuries and suggest novels and nonfiction that dive deeper.

LEPROSY

Before and after the plague, leprosy was a much-feared contagious and often fatal bacterial nerve disease for thousands of years.

Disfiguring symptoms (rash-like skin patches and loss of extremities due to inability to feel pain) meant people afflicted with leprosy were shunned and often forced to live in leper colonies.

Most people avoided lepers, but not these heroes:

Francis of Assisi and followers caring for lepers, artist unknown

Francis of Assisi and followers caring for lepers, artist unknownFrancis of Assisi—(1181-1226) was a rich young man who abandoned his life of luxury for a life of poverty devoted to living like Jesus, preaching and serving people. Although he had felt a long-standing revulsion, he not only gave lepers coins for food, but also embraced them. Evidence suggests he may have contracted leprosy from these contacts.

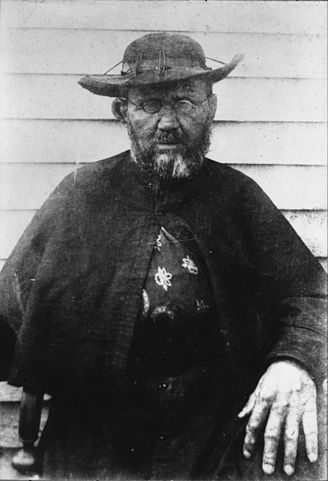

Father Damian, afflicted with leprosy, in Molokai

Father Damian, afflicted with leprosy, in MolokaiFather Damian—(1840-1889) was a Catholic priest who ministered to lepers’ physical, spiritual. and emotional needs on the Hawaiian island of Moloka’i, where the state ordered them to live in isolation. He lived there for eleven years and contracted the disease himself. He continued his work on Moloka’i and died six years later.

Read about them:

Saint Francis of Assisi, biography by G.K. Chesterton

Moloka’i, historical novel by Alan Brennert

Or watch: Brother Sun, Sister Moon (popular 1972 movie about life of Francis)

PLAGUES (beginning in the mid-1300s):

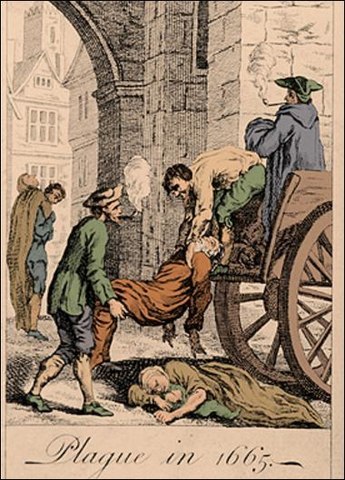

Loading plague victims onto a cart

Loading plague victims onto a cart“The mystery of the contagion was ‘the most terrible of all the terrors,'” author Barbara Tuchman wrote about the Black Death (Bubonic Plague) of the 14th century, in her novel, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century.

Because people didn’t understand the causes of the plague, Christian men and women known as flagellants wandered through town and countryside flogging themselves, trying to atone for the world’s evil. They believed this might persuade God to end the plague.

Others scapegoated Jews, believing they had caused the plague by poisoning water. As was common through the centuries, people turned to violence, expulsions and massacres against their Jewish neighbors (including burning to death nearly two hundred Jews in Strasbourg in 1349).

Yet others sacrificed their lives to care for the sick, such as in Wittenberg, Saxony, in 1527:

The plague arrived in the town of Wittenberg, where Martin Luther taught and lived, in August, 1527. Then:

The university shut down.Many students and professors fled.Luther’s patron, the Elector of Saxony, ordered Luther to leave.Luther refused, insisting he needed to stay to minister to the townspeople.Luther and his wife, Katharina, opened their home to shelter and treat plague victims.Luther’s own son became ill, but survived.

Read about it:

Decameron—written during Italian Renaissance, characters escape the Plague by retreating to a villa in the Italian countryside to wait out the end of the plague

A Distant Mirror, by Barbara Tuchman (novel, mentioned above)

Katharina Fortitude, by Margaret Skea—novel about Katharina von Bora’s marriage and life with Martin Luther, including the time of Plague

The Reformation of Suffering: Pastoral Theology and Lay Piety in Late Medieval and Early Modern Germany, by Ronald K. Rittgers—(nonfiction) scholarly examination of responses to the plague and other suffering

Plague in 17th-Century England:

Plague arrived in London in Spring, 1665.Theaters, Oxford and Cambridge Universities were closed.In 1666, King Charles II commanded an end to all public gatherings.Many wealthy Londoners fled to the countryside to escape infection. In London, the sick and those in their households were quarantined, with the government supplying their food.

Read about it:

Samuel Pepys’ diary: (nonfiction) his entries from Spring,1665-1666 chronicled London’s bubonic plague epidemic

For more on this Plague outbreak, see this recent article: “What Social Distancing Looked Like in 1666.”

A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe—Over 50 years after the epidemic, Defoe drew upon historical documents to write this realistic novel about the plague’s effects on London.

The Weight of Ink, by Rachel Kadish—a fascinating time-split novel set partly in 17th-century London at the time of the Plague

Year of Wonder, by Geraldine Brooks. Fictionalized account of how a town in the English countryside isolated itself to prevent the spread of the Plague

EPIDEMICS IN THE HABSBURG EMPIRE:

In 1710, Emperor Joseph I attempted to isolate his territories from the spread of disease

He created a “sanitary cordon” several miles deep along the thousand-mile-long southern border with the Ottoman Empire.He died of smallpox the following year, in spite of his efforts.

Read about it:

For more, see this article: “Joseph I’s Coronavirus Solution.”

Nonfiction:

The Habsburg Monarchy 1618-1815, by Charles Ingrao

The Grand Strategy of the Habsburg Empire, by A. Wess Mitchell

Readers, are there lessons we can draw from these stories from the past?

The post When Contagion Strikes appeared first on C.L.R. Peterson, Author.

March 27, 2020

Historical novels to enjoy during quarantine

Health and peace to you in these uncertain times! Since life has changed and many of us must spend our days isolated from people and our normal activities, I’m offering suggestions of some of my favorite titles of historical fiction set in Europe. Fortunately, these novels are available as ebooks you can access from home free through your local library or purchase them online.

I just finished reading a terrific novel published last fall, The Last Train to London, by Meg Waite Clayton. What made it so special?

The author cleverly structures this historical novel so that even readers familiar with the Kindertransports prior to World War II will find it suspenseful. She humanizes her characters so we root for them, even as we see their flaws. Given the dark times in which this novel is set, readers can assume that not all the sympathetic characters will survive, but which ones? She masterfully interweaves several plot threads in fast-paced scenes with life-and-death stakes, compelling readers to the conclusion to find out who will live to see another day. Clayton’s notes reveal her impressive research to achieve historical accuracy, including her meticulous study of the autobiography of one of the main characters (a real historical figure).

I

highly recommend this novel, with the warning that it will be hard to put down.

My favorite historical novels set in Europe:

These books encompass a wide variety of locations, topics, and points of view, so I’d suggest reading a blurb or sample to see if a title suits your taste. I’ve included only one book per author, although I’ve enjoyed multiple novels by several of these authors.

Gutenberg’s Apprentice, by Alix Christie (Germany, late 1400s)Wolf Hall, by Hilary Mantel (England, 1500s)Girl with a Pearl Earring, by Tracy Chevalier (Holland, 1600s)Trial of Sören Qvist, by Janet Lewis (Denmark, 1600s)Suite Française, by Irène Némirovsky (France, World War II)

The following novels are set in Renaissance Italy:

The Agony and the Ecstasy, by Irving StonePainter’s Apprentice, by Laura MorelliSecret Book of Grazia dei’Rossi, by Jacqueline ParkSecond Duchess, by Elizabeth LoupasBirth of Venus, by Sarah Dunant

Thanks to reader Pam S.! She responded to last month’s question and reminded me of a fascinating novel about quarantine set in the Hawaiian Islands: Moloka’i, by Alan Brennert.

Readers, what are your favorite novels set in Europe that you’d add to my list?

The post Historical novels to enjoy during quarantine appeared first on C.L.R. Peterson, Author.

February 27, 2020

Quarantine–whose genius idea ?

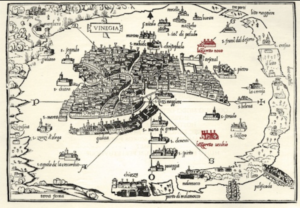

Old Venice map with quarantine islands in red

Old Venice map with quarantine islands in redQuarantines are in the news again, as nations around the globe isolate people suspected of carrying a contagious, sometimes lethal, illness.

Believe it or not, quarantine is a practice that’s been around for over 500 years. The term came from the Italian word, quaranta, which means 40.

Why am I, a historical novelist, writing about quarantine?

The same research that prepared me to write Lucia’s Renaissance, my novel set mostly in Venice, also informed me about this important part of Venice’s history:

Not just once (in 1348), but multiple times, the black (Bubonic) plague ravaged Venice—killing up to 1/3 of the population.Venice was a trade center with ships arriving from many places, so it’s not surprising it was the first city that forced people to stay quarantined for 40 days to stop diseases from spreading.Venice was built on islands, and after its leader, Doge Giovanni Mocenigo, died of the plague in 1485, the city funded a hospital on a nearby island, eventually calling it the lazzaretto vecchio, (old quarantine site) which cared for people ill with the plague.Another island, called the lazzaretto nuovo (new quarantine site), housed newcomers and traders who might bring diseases into the city. Reports indicated the food was good.The lucky people who survived the lazzaretto vecchio and recovered convalesced at the lazzaretto nuovo.At the end of each of five onslaughts of the plague, Venice built a church to thank God for deliverance (San Sebastiano, San Giobbe, San Rocco, Il Redentore, Santa Maria della Salute).

Redentore (Redeemer) Church in Venice, built after 1576 plague

Redentore (Redeemer) Church in Venice, built after 1576 plague

Were quarantines

effective?

Although thousands died in Venice, quarantines certainly spared many livesPeople who were sent to the quarantine island for the sick, lazzaretto vecchio, rarely survived. Recent archaeological excavations have revealed mass graves containing thousands of skeletons dating back to the plague epidemics.

Is there a lesson for

today?

Quarantines are a good idea anytime there is a deadly and infectious disease with no known

cure or vaccination

(This conclusion from a helpful physician friend—many thanks!)

Quarantine and the plague in fiction:

Plagues and quarantine in Lucia’s Renaissance, my novel:

Plague strikes Verona, killing many and causing panicA scene takes place on one of Venice’s quarantine islandsAfter the 1576 plague in Venice kills over 25% of the population, families are upended by their lossesWhen the 1576 plague ends, Venice builds the magnificent Church of the Redeemer (Redentore),

Many other novels feature plagues and quarantine in their plots. I’m mentioning a few titles by well-known authors. I haven’t read them all, but suggest caution: given the topic, in some of these, details may be graphic:

The Decameron, by Giovanni Boccaccio—a rollicking story set during the plague, written in the Renaissance eraA Journal of the Plague Year, by Daniel Defoe—a fictional journal of a doctor working with the sick in London during the plagueThe Betrothed, by Alessandro Manzoni—his best-known work, a three-volume historical novel that depicts a plague that struck Milan two centuries earlierThe Scarlet Plague, by Jack London—takes place far into the future, charting sixty years of the “Red Death” that depopulates the planet before the novel begins in 2073The Plague, by Albert Camus—story of a cholera outbreak in Oran, Algeria A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, by Barbara Tuchman—incorporates both the great rhythms of history and the nitty-gritty of domestic life (including the plague)World Without End, by Ken Follett– a sweeping tale that deals with the fallout from both the 100 Years war and the plagueYear of Wonders, by Geraldine Brooks—set in an English town during the plague of 1666, deals with death, superstition, and paranoia

Can you recommend a favorite novel about quarantine or plague?

The post Quarantine–whose genius idea ? appeared first on C.L.R. Peterson, Author.

January 26, 2020

Who saved England from Spanish conquerors?

Spanish Armada galleass

Spanish Armada galleassWhat

if

the Spanish Armada had invaded England in 1588?

If Spain had conquered England

and deposed Queen Elizabeth I, our lives would surely be different today:

The Protestant Reformation probably wouldn’t have

enduredSpanish explorers would have claimed much more of

the world for Spain Science, philosophy, and literature would have

developed very differently.

Many people credit Sir Francis Drake with defeating the Spanish Armada. But without ordinary people, Drake couldn’t have succeeded. How did ordinary people help ?

Spies (often civilians in the right place at the right time) passed on important military information to England, and codebreakers interpreted it. Merchants and even pirates supplied 192 of the 226 ships the British navy assembled to face the Spanish Armada in 1588—only 34 ships belonged to Queen Elizabeth I. Civilian ships carried supplies and troops, as well as battling to defend themselves or others.Shipbuilders (shipwrights) designed and built ships that could function both to carry cargo and defend themselves or battle hostile ships.

Even

after the defeat of the Armada, England still faced danger.

Here’s a dramatic true example of the power of an ordinary person in England in the early 1600s:

One lit fuse could blow up a king and all his Parliament members. BUT one brave man could save all those lives by speaking up about a letter he received.

This was the Gunpowder Plot, which took place in England in 1605. Religious divisions had fractured the English nation for decades, and now a group of unhappy Catholics wanted to rid England of King James I.

One of the plotters—his identity is still debated—wanted to protect his friend, Lord Monteagle, who would normally attend Parliament meetings. The plotter sent Monteagle a letter warning him to stay far away on November 5th, because Parliament would receive “a terrible blow.”

Letter to Monteagle

Letter to MonteagleLord

Monteagle took the letter to Robert Cecil, England’s Secretary of State, who instructed

his officers to search the upper and lower levels of the House of Lords.

On November 4th, the night before King James and Parliament gathered, Guy Fawkes was caught in the cellar of the House of Lords with barrels of gunpowder and fuses—just in time to prevent the plot from succeeding!

One man’s courage and effort saved King James I and many others.

What examples can you share of other situations where ordinary people changed the course of history?

The post Who saved England from Spanish conquerors? appeared first on C.L.R. Peterson, Author.

July 25, 2019

Those Stubborn Waldensians!

“The stubbornest bunch of people you would

ever want to meet“—a Waldensian family, as described by a contemporary

descendant.

Who were the Waldensians, and why did they become so stubborn? In about 1170, Peter Waldo, a merchant in Lyon, France, was inspired by the story of St. Alexis. In an effort to draw closer to God, gave away most of his possessions to the poor. He also had the Gospels and other Biblical passages translated into French, and he began to preach in the streets. He focused on teaching the Bible rather than the Church’s added doctrines, such as offerings or prayers for the dead, purgatory, and payments to get souls out of purgatory.

His movement, which became known as the Poor of Lyon, allowed lay people, including women, to preach. Their main source of inspiration was the Sermon on the Mount, and they advocated non-violence. They refused to swear oaths and also rejected any compromise by the Church with those having political power.

As this movement gained followers, religious leaders began to condemn it. Persecution began by 1215, when the Roman Church declared Waldensians were heretics, to be excommunicated and punished if they didn’t repent.

In spite or because of this, the movement spread from the south of France to Italy, from Lyon to Bergamo, from Provence, in south of France, to Guardia Piemontese in Calabria (south Italy), from the Waldensian Valleys, in Piedmont (northwest Italy), to Venice (northeast Italy), and finally to Austria, Germany, Poland, and Czechoslovakia.

More

persecution followed:

1487-1507: anti-Waldensian crusade led by

Cremona’s Archdeacon

1545:

Waldensian community in Provence was exterminated

1560: first persecution of Waldensians by troops of Savoy’s Duke

Emanuele Filiberto

1561: Treaty of Cavour drove Waldensians out of the plains to

worship in remote mountains, halting the group’s spread

17th century:

persecution continued

1655: Piedmont Easter massacre–1700 Waldensians killed in a campaign of looting, rape, torture, and murder. News of these atrocities reached England and the Netherlands. John Milton wrote a poem about it, “On the Late Massacre in Piedmont.” Following are a few lines:

“Avenge, O Lord, thy slaughter’d saints,

whose bones

Lie scatter’d on the Alpine mountains cold,

Ev’n them who kept thy truth so pure of old,

When all our fathers worshipp’d stocks and stones…

Who were thy sheep and in their ancient

fold

Slain by the bloody Piemontese that roll’d

Mother with infant down the rocks…”

1685: after

the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, all the Waldensians (12,000) were

imprisoned

1687: the

few survivors (2,700) were deported from Piedmont to Geneva

In 1689 the Waldensians returned to their valley, armed, to regain

their lands and their right to exist (The Glorious Return).

Like the Jewish people, if the Waldensians weren’t strong in their beliefs and personality, they would have converted to Catholicism centuries ago to avoid persecution.

In

addition to northern Italy, Waldensian survivors have established communities

in southern Italy, Argentina, Brazil, Germany, Uruguay, and Valdese, NC (see http://www.waldensianheritagemuseum.org/

Why do I care

about the Waldensians? Their villages

offered a potential refuge to characters in my novel-in-progress.

Inspiring, tough

people, those Waldensians!

The post Those Stubborn Waldensians! appeared first on C.L.R. Peterson, Author.

April 11, 2019

Heretics and bunny trails

Readers of my debut novel, Lucia’s Renaissance, have insisted it needed a sequel “yesterday.” My apologies if you’re among those frustrated souls!

What’s taking me so long?

Research! I’ve been on a quest to pursue the trails of Italian followers of Martin Luther, and my penchant for getting the historical details right slows down the writing considerably.

Rome’s Inquisition kept its eyes and ears on those 16th-century Italian heretics, so they did their best to conceal their beliefs and activities (which makes it all the harder to track them down 500+ years later). But I’ve found breadcrumbs (heresy trial records, journals, histories) along the trail!

What

happened to Luther’s Italian followers?

Here’s what I’ve found so far:

Some managed to hide

in place (concealing or abandoning their beliefs) Some were arrested by

the Inquisition, tried, and executed or imprisonedSome fled to (temporarily)

safer parts of ItalySome emigrated to

northern Europe: Switzerland, Germany, England, FranceThe Waldensians, a

group living in the mountains and valleys near the French border, held reformed

beliefs long before Luther and survived longer than any other Italian followers

of the Reformation. Their story of persecution and resistance fascinates me,

and I’ll talk more about them in my next post.

Map of Europe in the times of Luther and Calvin, By Merle d’Aubigné, Jean Henri

Map of Europe in the times of Luther and Calvin, By Merle d’Aubigné, Jean HenriWith

so many trails to pursue, I’ve been busy deciding which way my characters will

go.

What

would you have done if you’d lived in Italy at that time?

The post Heretics and bunny trails appeared first on C.L.R. Peterson, Author.