Tiago Forte's Blog, page 36

June 11, 2019

The Story Behind Building a Second Brain

I first started taking notes on a computer at the age of 22, when I came down with a mysterious illness in college. The pain was inconsistent, varying a lot from day to day. At first I thought it was a temporary thing, that it would soon go away. But it grew steadily worse, over months and then years. I started seeing every kind of doctor and specialist I could find. But none of them could pin down the cause, much less a solution.

I found myself sitting in a neurologist’s office one day, as the doctor recommended a powerful painkiller that might fix the problem at the cost of dulling sensation throughout my entire body. Considering such a drastic measure, I realized that I was at rock bottom. I felt like I had no future, that the things I wanted in my life were permanently out of reach because of this condition I couldn’t explain. Sitting in that chair and watching the doctor write the prescription, I had a realization: I could spend years bouncing back and forth between different specialists, taking various medications, and never find true relief. I realized that no one person was going to solve this problem for me. I had to be my own advocate. I had to take charge of my own treatment.

I began asking the receptionists for my patient records and scanning them into my computer. Before long I had an extensive file to manage, and I started organizing it by date, by specialty, and by doctor. I would arrive at each doctor’s appointment with a list of questions I wanted answered by the time I left. I started doing my own research, reading about obscure findings in medical journals, and guiding the process according to what I thought might help.

Eventually, it became clear that there wouldn’t be a definitive remedy. After every diagnostic test and scan imaginable, and tens of thousands of dollars spent, there didn’t seem to be any single cause for my symptoms. I began to realize that what I had was not a temporary illness, but a chronic condition. I needed to manage it, not fix it. My notes again came in handy: in a matter of hours, I was able to search through years of observations and findings, tagging anything that seemed to help. I was able to identify almost a dozen practical measures – for sleeping, eating, exercising, and stretching – that when practiced regularly, helped minimize the pain and allowed me to function normally. It seemed like a miracle, but the answers I needed were waiting right there in my notes.

Speaking with people about my experience over the years, I’ve been surprised to find that many of them have some sort of chronic condition. A bad knee, a mysterious allergy, a recurring infection, or an addiction that they can’t kick no matter how hard they try. The medical system isn’t designed to treat us holistically. If it can’t be fixed with a pill or a surgery, it falls on you to organize your records and change things up when they’re not working. It was around this time that I began to seriously think about the potential of digital notes to improve people’s health, whether they are sick or just need better self-care. What if instead of a patient chart with indecipherable scribbles only available to doctors, we had an organized and accessible database of our entire health history across every doctor?

I returned from the Peace Corps in 2012 and moved to San Francisco, plunging directly into the epicenter of Silicon Valley for my first “real” job at a boutique consulting firm. The transition was a total shock: the pace of work and the volume of information I was expected to handle were utterly overwhelming.

In an effort to keep my head above water, and to document the immense amount of learning I was expected to take on, I again turned to digital notes. I began writing down everything I learned, from facts gleaned from research reports, to interesting insights I saw on social media, to feedback from my more experienced colleagues. As time passed, this repository of notes became a valuable tool in delivering my work quickly and at high quality. My colleagues commented that I seemed to have an incredible memory. But I wasn’t remembering at all. I was retrieving things from my notes. I became the go-to person for finding that one file, or retrieving that one fact, or remembering exactly what the client said.

I learned a lot in that job about how knowledge is acquired and sold. The consultancy is essentially being paid by their clients to learn about cutting-edge new trends, such as machine learning, big data, gamification, online marketplaces, or chatbots. This learning is inevitably time-consuming and messy, but once the analysts have been through that difficult learning process, the company can turn around and convert that knowledge into all kinds of other formats like workshops, talks, panels, conferences, social media posts, and white papers. I began to see my growing collection of notes not just as a professional asset for a single job, but as potentially a business asset I could one day use to start a business of my own.

As much as I enjoyed the experience that consulting gave me, I was getting tired of the relentless work schedule required. I had no desire to climb the corporate ladder, only to take on an even more demanding schedule. I knew that I had something to offer from what I had learned and experienced in my life. I had always been a teacher – of English as a second language and computer skills. But I wanted to contribute my own ideas directly to people who could benefit from them. I wanted to take control of my destiny, but wasn’t quite sure how.

I discovered online courses in 2013, and quickly fell in love with the idea of teaching people all over the world what I knew. I decided to make one of my own, and once again, my digital notes came to the rescue. I found that my habit of writing everything down in one place meant that my knowledge was already in a tangible form. I had all the most interesting points from all the articles and books I’d read over years summarized succinctly on my computer. From there, it was a small step to making it into not only an online course, but the social media posts, blog posts, and videos required to promote that course. In other words, I didn’t start a business with some grand strategic plan. I didn’t even consider it a “business” until a couple years later. Instead, I built a portfolio of products one at a time, by converting my knowledge into formats that could be packaged up and sold online.

I don’t want to give the impression that starting a business was easy. I was often broke, barely able to pay the rent. I took many wrong turns, investing in projects that led nowhere. But my salvation was always my ability to create new content out of what I was learning. Some of my biggest failures became my best pieces of writing.

Starting a blog about a year later, I found that having a rich collection of notes at my disposal made writing much easier. All I had to do was gather a few related notes, string them together into an outline, add transitions and supporting points, and I could regularly publish long, detailed articles diving deep into topics that interested me. The blog soon became the key driver of my entire business. It functioned as an idea laboratory, allowing me to test out ideas before making them into products and services. It functioned as a marketing funnel, attracting readers with free content who later became paying customers. It brought me collaborations and partnerships, because people could see upfront what I stood for and what I had to offer. And eventually, I had enough posts to compile into ebooks, which I sold online to provide extra income.

At some point I realized that my digital notes were much more than a few interesting ideas jotted down somewhere. They constituted a “second brain” full of ideas, insights, theories, facts, research, and other valuable knowledge. I was able to accomplish difficult things – starting and growing a business, teaching thousands of people online, consulting with companies on their productivity, and coaching clients – while working no more than 30 hours per week, traveling extensively, and pursuing hobbies like sailing. I was able to produce a lot of content, writing hundreds of blog posts and 5 books, without being a full-time writer. My notes allowed me to live a life of creative and intellectual exploration without sacrificing security and quality of life.

Talking to my customers about the struggles they faced with their productivity, I realized that everyone could benefit enormously from such a tool, but that almost no one had one. Note-taking is a universal way to save and interact with knowledge that goes back hundreds of years. Yet no one teaches it, not in the workplace and especially not in digital form. We are expected to consume huge volumes of information in our work, and then we spend our free time reading books and listening to podcasts. Yet so little of this valuable knowledge gets saved and put to use. I knew that I had something that could change this situation, and that people would benefit so much from not trying to keep it all in their heads.

I set out to develop the world’s first course on what I began to call Personal Knowledge Management. I wrote blog posts describing my approach and got feedback as people tried what I recommended. I gave talks advocating for a new way of thinking about knowledge management. I started doing live trainings walking people step-by-step through setting up a note-taking system. And eventually, I put everything I had learned into an online course called Building a Second Brain. That course has now been taken by more than 800 people from all over the world, in a wide variety of industries and professions. Every day I receive testimonials on how it has given them freedom and clarity in their professional lives, as well as the confidence to take on new creative challenges.

I’ve had the privilege of serving tens of thousands of people with my online courses, and hundreds of thousands with my content. I’ve worked with many of the most prestigious and influential companies, governmental agencies, and non-profit organizations in the world – such as Toyota, Nestle, Genentech, Sunrun, and the Inter-American Development Bank – helping them maximize the potential of their institutional knowledge. Most gratifyingly, I’ve received many messages telling me stories of how building a second brain has made such a difference, from entrepreneurs in Argentina, to college students in North Carolina, to NASA scientists, to well-known writers and intellectuals.

At each stage of my journey, I’ve found that having my research, my knowledge, and my ideas in a tangible, external form allowed me to adapt more quickly, bounce back from disappointments and failures, and produce value no matter what situation I found myself in. Having a second brain has very much been like having a loyal collaborator and thought partner. When I am forgetful, it remembers. When I lose the plot, it reminds me where we’re going. When I’m stuck and at a loss for ideas, it seems to always point the way forward.

I’ve come to believe that knowledge management is one of the most fundamental challenges, as well as one of the most precious opportunities, for people today. How many books and articles do you read every year? How many podcasts and videos do you consume? How many courses or conferences do you attend? How many interesting and insightful conversations do you have? How much have you learned in your job and over the course of your career?

What have you done with all this knowledge you’ve gained? Where is it? What do you have to show for it? We feel this pressure to constantly be improving ourselves, to constantly be learning, but so much of what we consume just goes in one ear and out the other. We invest countless hours of our lives reading and consuming the knowledge of others, yet so few turning it into something of our own.

The course I created to teach everything I’ve learned is called Building a Second Brain. It is an online, video-based course on personal knowledge management. The course teaches participants how to capture, organize, and share their valuable knowledge using digital tools. Instead of allowing ideas and insights to slowly fade from memory, it provides a systematic approach to cultivating and resurfacing them over time.

Building a Second Brain draws on my work with Silicon Valley startups, multinational corporations, freelancers, entrepreneurs, and professionals that have to manage a large volume of information and deploy it effectively under high-stress conditions. All of us now have to manage large volumes of information to do our jobs and simply live our lives, while simultaneously doing our best and most creative work. It’s up to each of us to curate that information for lifelong learning. We can build a robust collection of personalized and useful knowledge to take from job to job. Such a collection can help us make unusual connections between ideas, incubate ideas over long periods of time, provide the raw material for new creative projects, and create opportunities for serendipity.

By offloading our thinking onto a “second brain” – a centralized, digital repository for the things we learn and work on – we free our mind to imagine, create, and simply be present. We can move through life confident that we will remember everything that matters, instead of floundering through our days struggling to keep track of every detail. This gives us the confidence to take on new creative challenges that have a greater impact on our organizations and customers and colleagues. The ability to capture things we learn, recycle and resurface our ideas, and retrieve them right when we need them becomes a cognitive superpower, amplifying our intellectual and creative abilities while preserving our time and peace of mind.

I’ve distilled everything I’ve learned about personal knowledge management into one unified curriculum, providing a blueprint for using technology to extend and expand the capabilities of the human mind. If you ever wished you could learn faster, work less, or more effectively manage all your ideas and projects, then you’ll definitely want to build a second brain.

Click here to join version 8.0 of the course, kicking off July 3, 2019

Thank you to Zhan Li, Jaylene Wallick, Jordan Ayres, Thiago Ghisi, Cam Houser, Hibai Unzueta, Ben Mercer, Ablorde Ashigbi, Deepum Patel, Deepak Rao, Evan Driscoll, Alexander Hugh Sam, Juvoni Beckford, David Perell, and Alex Schleber for their feedback and suggestions on this piece.

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

June 3, 2019

Adapting to PARA using GitLab

This post was originally published on Julius Gamanyi’s blog

It’s almost 2 months since I started walking through Tiago Forte‘s series on PARA Method (Projects. Areas. Resources. Archives) and implementing it. I’ve got Ben Mosior and Tasshin Fogleman to thank for the connection.

I loved these series, especially the fifth one, the Project List Mindsweep, because it’s broad enough to cover both home and professional life, and fine enough to manage “actionable systems” (To do lists) and non-actionable systems (where we store reference information), as read in:

the Project List was the lynchpin of not only P.A.R.A. and your broader PKM (personal knowledge management) system, but to your entire working life. . . your Project List is transmitting information between your actionable and non-actionable systems

Tiago Forte’s Project List Mindsweep

Pain points from Friction

The article and the corresponding Evernote templates were a great help. Yet, when it came to the practice, I found myself overwhelmed: there are at least 2 Evernote notes to keep open: the article itself and a copy of the template – this is where I’ll list the project titles, and if necessary, the descriptions. I followed the article, step by step, while updating the template. For each step in the article, I had to copy the project title into the relevant section in the Template, and then modify the project title a little bit, either to write the desired outcome or to review them. I couldn’t sustain that repetition after 3 projects.

Turning to Excel Spreadsheets

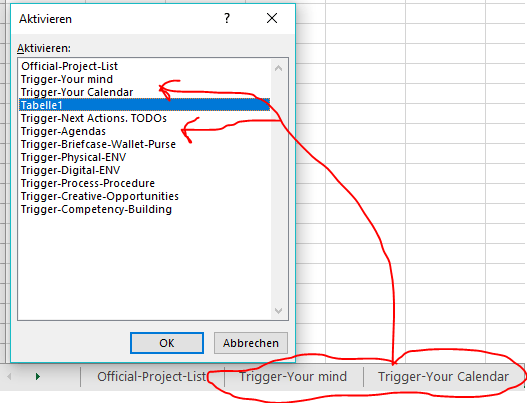

This prompted me to find a different way of dealing with these. I naturally turned to Excel, which was sufficient to start with. Each worksheet corresponded to a “trigger.”

Excel worksheets corresponding to each trigger mentioned in Part 5 of PARA

In the worksheet, each project with its title and description was a row; and each step, a column. Following the steps for all my projects became easier. But I have project ideas almost every week (when I’m commuting, in discussions with others, etc). Project ideas also come when doing the weekly/monthly reviews. Adding these to the Excel Spreadsheet was not appealing because Excel, working poorly on mobile, means I need to have a laptop to update it.

I ended up looking for a way to visualise all the projects, the steps described for Project Lists, and the PARA workflow (especially the weekly and monthly review). Trying a visual board like Trello/Jira/GitLab seemed like the next step to me.

My 2 main requirements were to be able to have multiple boards and to be able to create a card/issue by sending an email. Why email? Take a look at One-Touch to Inbox Zero.

GitLab Setup

Since I already had a GitLab account, I chose to use that one instead of the other tools. GitLab offers multiple boards at the project level, and group level.

The bronze level subscription ($4/month) gives you multiple boards on one project. This is the one I’ve started with. For silver subscriptions, multiple boards are also available at the group level. I’ve encountered 2 limitations with GitLab:

I can’t duplicate items – it’s copy and paste (at least for now).

A board’s description is not formatted and ends up as one long line. Nevertheless, it’s still useful to have.

[image error]

I’ve configured my GitLab to allow me to do this. In the GitLab project, “jg-para,” I’ve setup boards to match the Workflow.

I took my brain dump Project List, combined all worksheets into one, with two columns (title, description), saved it as a csv file and imported them all into GitLab.

In my day-to-day work, when I think of an idea that could be a project, or from any of the “triggers,” I send an email to the relevant project in GitLab and an issue is created. Much the same way that emailing our Evernote account’s email address creates a corresponding note in Evernote.

Now I know that all project ideas are in one place. Later, maybe during one of the review cycles, I’ll still be able to follow the steps in that article to deal with these project ideas.

Because each GitLab “issue” represents a potential PARA “project”, after an issue goes into the “Executable” board, it gets its own Notebook in Evernote. Before using GitLab, I used to create an Evernote notebook for potential projects. After the steps of “Organise” and “Reflect,” I’d delete the project notebooks that are no longer relevant.

This setup has made the PARA steps, workflows, and my projects visible. In turn, I no longer feel so overwhelmed.

Of course, none of this would be possible without these series on PARA.

Animated GIF as Summary

Summarised in a visual gif :

[image error]

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

May 17, 2019

Introducing the Forte Labs OneNote Resource Guide

We’re very proud to introduce version 1.0 of the Forte Labs OneNote Resource Guide. It is a public, shared notebook containing videos, tutorials, add-ons, technical and reference information, and other resources. The notebook was created with Microsoft OneNote and is designed to allow anyone to quickly learn the ins and outs of the popular digital note-taking program.

Click here to view the Resource Guide

Watch the video below for instructions on how to view the shared notebook and, if you’d like, save it to your own account. Keep reading below to find out why we created it.

Why have we created it?

Our mission is to enable everyone in the world to build a “second brain” – an external, centralized, digital repository for the things they learn. This starts with digital note-taking apps, which we believe are the category of software best-suited to this endeavor.

While Evernote was the first official note-taking app we supported, the Building a Second Brain (BASB) methodology doesn’t require any specific app to work. As long as it meets most of the essential requirements, any software program can do the job.

We are beginning to do more live workshops and corporate trainings, and we’ve learned that not everyone has total freedom to use any tool they want. Especially in institutions (from schools and libraries to nonprofits and companies), many people don’t have the ability to install new programs, or work under strict regulatory or privacy rules, or simply don’t want to use something different than their colleagues use.

For that reason, we’re going to be developing resources on how to use a range of the most popular note-taking apps out there, starting with Microsoft’s official note-taking app OneNote. OneNote is installed on many millions of machines around the world, either by itself or as part of the Office productivity suite. It is free to download and use indefinitely, available on a wide variety of devices, and well-supported by an active development team.

We believe that OneNote represents one of the most accessible and widespread opportunities to give everyone the chance to build a second brain of their own. We hope this Resource Guide helps you adopt digital note-taking as an essential part of your productivity, no matter which particular program you use.

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

May 14, 2019

Top 10 Things I Learned from Chimp Essentials

I recently completed an online course called Chimp Essentials, by well-known writer and freelancer Paul Jarvis. The course teaches everything you need to know to be able to effectively use the email service provider Mailchimp for your online communication and marketing.

I took Chimp Essentials to finally get serious about email marketing after years of running a (mostly) online business. I had opened a free account years ago and used its basic features to start sending emails to a couple hundred people. But it had grown steadily over the years into a tangled mess.

I had numerous vaguely defined lists, with overlapping subscribers I was paying for two or three times over, and no ability to target specific groups or track their interests. I knew that email could be my most powerful communication and sales tool, and that getting a handle on it was going to be essential for future growth.

The course contains 49 short videos with basic to intermediate lessons on how to use Mailchimp to:

Manage an email list

Send out regular emails for newsletters, sales pitches, or other purposes

Customize an email template and signup form

Create automated email series that are triggered by certain events

Integrate Mailchimp with popular web platforms

Keep your subscriber list healthy and engaged

Below are the top 10 most useful things I learned from the course, and how I’ve put them to use in my business.

If you’re interested in taking Chimp Essentials, just join the waitlist here and you’ll receive an email a few days later with a one-time chance to purchase the course for $30 off (otherwise it opens publicly twice per year). Purchase the course and forward your email receipt to hello@fortelabs.co and I’ll invite you to an exclusive virtual workshop for Forte Labs followers.

My productivity and knowledge management methods are a great complement to email marketing, helping you consistently produce and publish quality work to send to your subscribers. I’ll answer any questions you have, show you my best tips and tricks, and share a few templates and tools I use to make email marketing as easy and effective as possible.

#1 – Authenticate (not just validate) your sending domain

I knew that I needed to “validate” any domain I wanted to be able to “send from.” In other words, if I wanted my mass emails to appear to come from hello@fortelabs, then I needed to validate the fortelabs.co domain.

Here’s what it looks like once that’s done (in Account > Settings > Domains):

[image error]

But I didn’t know that, if I wanted the maximum number of my emails to reach subscribers and not be classified as spam, I needed to also “authenticate” the domain. This takes a few extra steps, but will improve my deliverability.

It’s really hard to be successful at email marketing if your emails aren’t even being delivered!

#2 – Redesigning the default email signup form

For years I had used the default email signup form provided by Mailchimp. I thought, “If Mailchimp recommends it, it can’t be that bad right?” Boy was I wrong. The thing is ugly as hell:

[image error]

Jarvis led us through the process of making a few simple design tweaks, resulting in an equally simple, yet far more attractive signup page:

[image error]

This is now a page that I’m proud to put in my social media profiles and send to anyone who might want to follow me.

#3 – The difference between groups, merge tags, and segments

This terminology had long bedeviled me. No matter how many explanations I read or examples I saw, I could never quite wrap my head around how I should use these features.

But after this course I got it:

Merge tags are specific labels or attributes that are “applied” to a subscriber to save details about them (such as where they signed up or which product they purchased)

Groups can be based on merge tags, and put people who share certain tags into a group that you can send an email to (such as people who purchased a particular product)

Segments are groupings of subscribers based on conditions that you set (for example, people who signed up on a certain page AND haven’t purchased a certain product)

You can think of these three features as “layers” of groups, each one drawing on the one below. So groups can be made up of combinations of merge tags, and segments can be made up of combinations of groups. This allows you to set finely tuned criteria for who receives a given email.

Merge tags

Think of merge tags as changing a single field in a subscriber profile. For the page on my website collecting email addresses for people interested in my coaching program, I set Squarespace to change the “Coaching” field to “Yes.” Here’s what it looks like for one subscriber:

[image error]

Now I can add everyone who shares that tag to a group or segment, and send them a targeted email without bothering everyone else.

Groups

Groups are like multiple-answer questions, where every subscriber can choose as many as they want. For example, I set up an integration between Teachable (my online course platform) and Mailchimp to automatically add anyone who purchased a course to a master list called “Teachable students,” and also assign them to a group according to which course or courses they have purchased.

Here are all the groups, with abbreviations for each course name. I haven’t set up the integrations for a couple courses because I haven’t needed to send them an email yet:

[image error]

Now I can send specific emails to each of these groups, or see which courses a specific subscriber has purchased:

[image error]

Segments

Unlike groups, segments can only be created within Mailchimp. So I was able to “import” people to groups using an external integration with Teachable, but the more sophisticated capabilities of segments are exclusive to Mailchimp.

What are these capabilities? Basically, I can create “conditional statements” to automatically place people into segments based on specific criteria. For example, I created a new segment called “Coaching Upsell,” with the following conditions:

Subscriber HAS expressed interest in coaching (i.e. they have submitted their email address on my coaching page)

Subscriber IS in BASB group (indicating they have purchased the course)

If I save this segment, it will be automatically populated with any subscriber who meets those two conditions in the future. Why would I want to do this? For example, to periodically send an email to graduates of the course asking if they’d be interested in coaching.

#4 – The best strategy for managing email lists: One List

I’ve known for some time that the best strategy for managing Mailchimp is to have a single, all-encompassing list of ALL subscribers, and then to break them into groups and segments based on different criteria.

This is the best strategy because groups and segments can only be created within a single list. So the more you break up your following into separate lists, the more you limit your ability to create broad-based groups and segments that apply equally to everyone.

With separate lists, you might end up sending the same email to the same people multiple times if they have subscribed to more than one list. I found that every time I launched a new product or service and sent it to all my lists, I was “punishing” my best customers by sending them multiple identical emails, since they tended to be subscribed to multiple lists.

Mailchimp’s pricing also penalizes the multiple list approach. Monthly pricing is calculated based on “subscriber per list,” meaning that you will pay for each list the same person is subscribed to. Ugh.

Although I’m not yet able to completely move to One List, due to various restrictions with external integrations, I’ve made considerable progress since taking this course. I merged about 5 lists into other lists, differentiating subscribers by groups instead.

I’m now down to only 5 lists, instead of 10:

[image error]

#5 – The 3 ways to add people to groups

One of the biggest challenges I had previously was how to track the various interests and opt-ins of my subscribers. For example, if someone signed up to be a beta tester for a new product, how could I keep track of them until the next time I had something to get feedback on?

The only way that I knew of was to create a completely new email list, send them the signup form to subscribe, and then just pay for that list over months and months until the next time I needed to email them. With all the interests and special projects I am managing at any given time, this was quickly becoming untenable.

The solution was groups. Instead of giving each interest its own list, I could add everyone to my master newsletter list and then assign them to an “Interest group.” This has the added benefit of sending them my occasional newsletters, keeping in touch between long periods of inactivity.

I only have two interests so far, but will add more over time:

[image error]

What I learned that made this possible is the three ways to add someone to a group:

Add them in a behind-the-scenes way using WordPress or Zapier (in case you don’t want them to see which group they’re being added to)

Manually add them to a group (if it’s a one-time thing that doesn’t need to be automated)

Let them pick groups for themselves on a signup form (if you’re okay with groups being public)

I’m currently only using “behind-the-scenes” methods of adding people to groups, but eventually I want to allow subscribers to select from a menu of interests, and then only receive emails related to those interests.

Here’s an example of what those checkboxes will look like when someone is subscribing to my list:

[image error]

#6 – Landing pages for specific interests

Related to the problem above, I’ve needed a way to allow people to follow certain interests, without me having to pay for numerous lists. I had previously created a new list each and every time, which was breaking the bank.

When I transitioned these interests into groups, suddenly I had a new problem: how could existing subscribers add themselves to these groups? If I sent them the standard signup form for my newsletter list, it would give them a “You’re already on this list” error. This was a big problem, since I tend to have a core group of followers who are involved in many different things I’m doing.

Enter landing pages.

This is a relatively new feature from Mailchimp, which allows me to create dedicated web pages for specific interests. It also allows me to customize the page and make it visually attractive. Here’s the one I created for people interested in the Mesa Method, which I linked to from my blog and from my ebook of the same name:

[image error]

On this signup page, even my existing (and most loyal) followers can choose to follow this interest. All I have to do is create a new segment based on this “signup source,” and it will include everyone who signed up on this particular landing page.

#7 – Welcome email

I had heard many times that sending new subscribers a “welcome email” was a crucial practice for keeping them engaged. But in Chimp Essentials I learned just how critical it is. Welcome emails typically have higher engagement rates than any other kind of email, and help new subscribers remember what they signed up for and why.

Instead of the standard, quite ugly “Subscribe confirmation” email, I designed a new welcome email to automatically be sent to every person who subscribes here:

[image error]

Besides welcoming them to my newsletter, telling them what they will and won’t be receiving from me, and the purpose of my work, I included links and short descriptions for my top 10 all-time most popular articles. The goal is to show them what to expect, and to get them “hooked” with some of my very best free content.

In the last two weeks this email has been sent out to 158 people, with a 67% open rate and 30% click rate, which is absolutely phenomenal as email campaigns go:

[image error]

#8 – Email newsletter template

One of the key principles in effective email marketing seems to be consistency: using the same kinds of words, the same style and tone, sticking to the topic they signed up to hear about, etc.

While I refuse to stick to a publishing schedule, I learned that I could improve consistency another way: through the look and feel of my email design. I followed Jarvis’ instructions and created a very simple, standardized template for all future Forte Labs newsletters. You can see an example here:

[image error]

I learned that the best email designs are very simple, without a lot of graphics and ornamentation. I also changed the font and colors to match my website as closely as possible, so it looks like something that came from me.

#9 – Subscriber onboarding

Although most of Chimp Essentials focuses on practical, how-to steps, toward the end Jarvis discusses the psychology of good email marketing. He teaches that when onboarding new subscribers, there are three things you need to accomplish:

Accommodation: Introduce yourself and tell them what to expect from your list

Assimilation: Make them feel like they belong and connect with them

Acceleration: Get them involved by consuming your most popular content or responding to a question

For me this involved making just a few small adjustments in my welcome email:

Accommodation: Promising them my “Top 10 All-Time Most Popular Articles” if they sign up for my newsletter (instead of just “news and updates”), and then delivering on that promise in the welcome email

Assimilation: Including a link to my Manifesto in the welcome email, in case they want to know what I stand for

Acceleration: Encouraging them to read one of my most popular articles with short summaries (and the main topic bolded)

#10 – How to avoid list decay

I learned that typically about 25% of an email list “decays” (or stops reading) each year. This made me feel a lot better about the unsubscribes I regularly receive!

Jarvis explains some of the best ways to minimize list decay:

Determine signup sources that give you the most inactive subscribers (pop-ups often generate signups who are more likely to become inactive)

Check your opt-ins (free bonuses offered in exchange for an email address) to make sure they’re still relevant

Have a more specific or actionable welcome email

Always consider why someone would open your emails

Email them regularly, and not just with pitches

Although I tend to follow these guidelines already, they were a great reminder that someone signing up to my list is a big deal. They are giving me explicit permission to contact them – about the topic of productivity, of course, but also with pitches and launches.

The miracle of email is direct, unfettered, (nearly) free access to people’s inboxes. That is a great privilege in a world of constant noise and competition. The work I did in this course was my effort to honor that permission as best I could, by consistently delivering the value I’ve promised, in the most accessible and consumable way possible.

Looking back on the course, I think the greatest value was simply having a forcing function to sit down and dedicate a solid block of time to reforming my email practices. I already “knew” much of this information and could probably have Googled the rest, but that is not the same as having it all in one place, at one time, in a consistent format. Having a complete curriculum of step-by-step video walkthroughs, along with an extremely active and helpful Slack community channel, made this one of the best investments in online education I’ve ever made.

If you’re interested in taking Chimp Essentials, just join the waitlist here, purchase the course, and forward your email receipt to hello@fortelabs.co. I’ll invite you to an exclusive virtual workshop for Forte Labs followers (or send you the recording if it’s already taken place) where I’ll show you how to use my best productivity methods to make email marketing as seamless and effective as possible.

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

May 10, 2019

Real Magick Deconstructed (Interview with Chloe Good)

A few months ago I was wasting time on Twitter as usual, and came across a tweet by an online acquaintance referring to “magick.” I figured it was a typo, and messaged him to find out more.

That was the beginning of my introduction to the mysterious, strange, paradoxical world of “real magick.”

This isn’t about gimmicky magic tricks, hippie drum circles, or small-town goth teenagers on ouija boards. It’s a whole underground subculture of people who freely borrow ideas and techniques from the occult, religion, science, psychology, history, and anywhere else in order to “manifest their will into reality.” They sometimes distinguish their practice by adding a “k” at the end of “magic.”

I was recommended and read the book Advanced Magick for Beginners by Alan Chapman, a self-professed “magician” who recounts some of the history of magick through the ages, right up to the modern movement of “chaos magic,” which has predominated in recent years.

In the book, Chapman demystifies the field, boiling it down to a practical tool grounded in the laws of physics, while also maintaining the mystery and intrigue so necessary to inspire (self-)belief. I found it to be an intriguing mix of fact and fiction, story and theory, means and ends, all tied together as “the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will.”

Here’s my complete highlights from the book if you’d like a preview.

Sometime later, talking to my friend Chloe Good, I realized that she is an experienced practitioner of this brand of practical magick. She had always displayed a curious mix of hard-edged scientific knowledge with inexplicable metaphysical abilities, and now I understood why.

Chloe has a coaching practice in which she works with high-performers to discover their purpose, overcome internal barriers, and ultimately create the life they want to live. Part life coach, part therapist, part spiritual guide, and part business consultant, she embodies better than anyone I know the post-modern way of life that “real magick” entails.

She’s also a leader in her field, consulting with Silicon Valley leaders and executives at companies like eBay, Accenture, Square, Facebook and various Bay Area start-ups. She also teaches a strengths-based leadership course at Stanford University. Most recently, she has launched an online course called Own Your Magic in which she teaches her methods for living a life of your own creation.

Chloe has generously agreed to join us for the May Town Hall on 5/17 at 9am PST, to share her 4-step framework and extensive coaching experience. Click here to register for the live Zoom call, and come with your best questions!

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

My Top 10 All-Time Most Popular Articles

These are my Top 10 all-time most popular articles based on number of unique visitors:

1. One-Touch to Inbox Zero

A step-by-step guide to streamlining your email workflow, which will save you hours every week and consistently take you to “inbox zero.”

2. The Rise of the Full-Stack Freelancer

My prediction for the future of jobs, including a “portfolio approach” of multiple income streams instead of one paycheck.

3. The Secret Power of ‘Read It Later’ Apps

My best advice for how to use “Read Later” apps like Pocket and Instapaper as critical tools in your reading and learning.

4. How to Use Evernote for Your Creative Workflow

An essay on the power of digital note-taking for productivity, learning, and effectiveness, including practical techniques for how to effectively organize and use your notes.

5. Building a Second Brain: An Overview

A summary and overview of my online course Building a Second Brain, in which I teach people how to use digital notes as a “second brain” that remembers everything.

6. The Throughput of Learning

A metaphysical journey through the mysteries of flow, and how it ties together old-school manufacturing and modern knowledge work.

7. Progressive Summarization: A Practical Technique for Designing Discoverable Notes

A guide to Progressive Summarization, a method I’ve developed for systematically distilling the things you read into nuggets of actionable wisdom.

8. The PARA Method: A Universal System for Organizing Digital Information

A guide to the PARA Method, a method for organizing your digital life across all the platforms you use, and using your files to consistently reach your goals.

9. Theory of Constraints 101: Applying the Principles of Flow to Knowledge Work

My 11-part guide to the Theory of Constraints, a powerful framework for understanding and improving any kind of system (from your to do list all the way to large companies)

10. The Digital Productivity Pyramid

The model I’ve developed for professional development for the modern knowledge worker, each skill and tool building on the one before.

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

The BASB Customer Persona

I recently compiled all my notes, findings, and ideas about the “ideal customer” for Building a Second Brain, and put them into a single document. I’m working with my editor to narrow down and refine this customer profile from here, so I can have a crystal clear person in mind as I write the sample chapters for the book proposal.

I’m publishing it here to gather any feedback or ideas you may have about the kind of person I should be writing this book for. Hopefully it will also be useful for any creative projects you are working on that require identifying a target customer. The prompts and questions were pulled from various courses, books, and marketing exercises I’ve collected over the years.

To read this story, become a Praxis member.

Praxis

You can choose to support Praxis with a subscription for $10 each month or $100 annually.

Members get access to:

1–3 exclusive articles per month, written or curated by Tiago Forte of Forte Labs

Members-only comments and responses

Early access to new online courses, ebooks, and events

A monthly Town Hall, hosted by Tiago and conducted via live videoconference, which can include open discussions, hands-on tutorials, guest interviews, or online workshops on productivity-related topics

Click here to learn more about what's included in a Praxis membership.

Already a member? Sign in here.

May 3, 2019

Anti-Book Club 3.0: Group Knowledge Management

Last year I launched the Anti-Book Club, a new take on traditional book clubs in which everyone reads a different book on the same topic, and shares their summary notes. Instead of duplicating time and effort reading the same book, this process allowed us to combine our efforts and create an archive of distilled knowledge in an organized format.

The two rounds of the Anti-Book Club were a great success, and I recently published my learnings about its potential for crowdsourced research. Now it’s time for the next stage of evolution: pushing forward the frontier of group knowledge management for a specific organization.

Forte Labs has been hired by Global IO, a consulting firm that works with large companies with complex supply chains to improve their “integrated operations.” They’ve asked us to develop an “enterprise-grade group knowledge management system” that will help onboard new employees faster, capture tacit learning from projects, and share their most valuable knowledge in an effective way. We’ll use their company as a testing ground, and if it goes well, potentially expand to their clients.

To read this story, become a Praxis member.

Praxis

You can choose to support Praxis with a subscription for $10 each month or $100 annually.

Members get access to:

1–3 exclusive articles per month, written or curated by Tiago Forte of Forte Labs

Members-only comments and responses

Early access to new online courses, ebooks, and events

A monthly Town Hall, hosted by Tiago and conducted via live videoconference, which can include open discussions, hands-on tutorials, guest interviews, or online workshops on productivity-related topics

Click here to learn more about what's included in a Praxis membership.

Already a member? Sign in here.

My interview on the Justin Brady Podcast

Here’s a short interview I recently recorded with Justin Brady on his podcast, about the role of creativity in modern knowledge work. Listen below or click here to visit the official website.

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

My interview on the Mindhack Podcast: Finding the Achiever’s Mindset

I recently sat down with Cody McLain to talk about productivity, achievement, and personal growth. We went deep on the relationship between internal experiences like personal growth and self-awareness, and external measures of success that people usually associate with “achievement.”

Click here to visit the Mindhack website for the audio recording and full transcript.

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.