Chuck Wendig's Blog, page 144

March 5, 2015

Carrie Patel: Five Things I Learned Writing The Buried Life

The gaslight and shadows of the underground city of Recoletta hide secrets and lies. When Inspector Liesl Malone investigates the murder of a renowned historian, she finds herself stonewalled by the all-powerful Directorate of Preservation – Recoletta’s top-secret historical research facility.

When a second high-profile murder threatens the very fabric of city society, Malone and her rookie partner Rafe Sundar must tread carefully, lest they fall victim to not only the criminals they seek, but the government which purports to protect them. Knowledge is power, and power must be preserved at all costs…

***

JUST GO WITH IT

Writing your first book is a dare to yourself.

It starts with the embryo of a story and the nagging suspicion that, just maybe, you could grow it into a real book. So you carve out quiet little moments after work or school, pecking away at the keyboard and thinking, “Ha ha, look at this, I’m putting one word after the other, just like a real author.”

You don’t tell anyone about your little hobby—not yet. It feels too soon. Like introducing the parents on the first date. But late evenings and early mornings speed by in front of the computer, and you catch your wandering mind turning more and more to the next scene, the next plot twist, or the next juicy bit of worldbuilding.

You’re not entirely sure you’ve got the stamina to make it to the end. But somehow, seven thousand words become twenty thousand words, and before you know it, you’re sitting on fifty thousand words, and you’re too invested to quit.

Nothing demystifies the writing process so much as attempting it yourself. There’s no professional certification for it, no real prerequisite. By the time you’re waist-deep in it, what keeps you going is the sheer curiosity to see what happens next (both in and for your manuscript) and the challenge you continually issue yourself to get through one more chapter.

…BUT IT’S OKAY TO TAKE A STEP BACK

The first draft of THE BURIED LIFE took about a year to write. That’s not terribly unusual, especially for a first effort.

But I finished that draft over eight and a half years ago. All that time between then and now? Most of that’s been revising, editing, querying, and catching my skills up with my ambitions.

Writing a book is hard. But cleaning up the lump of coal that emerges from your fingertips at one in the morning and polishing it into something shiny and wonderful?

That’s harder.

You write this first draft, and typing “THE END” feels like reaching the summit of Everest, even though your manuscript only clocks in at 60,000 words, which is about 20,000 too short for the genre you’re writing.

And that’s only the first of your problems.

Then, you look back at paragraphs of lovingly crafted description and see them weighed down with adverbs and redundancy. You read through your first halting efforts at dialogue, and you shudder.

You close your laptop with the jarring realization that this misbegotten child of a manuscript is not the book you sat down to write.

Worse, you don’t know how to fix it. You don’t know how to make your worldbuilding feel compelling and interesting, and you don’t know how to make your dialogue believable, let alone entertaining.

So you set it aside, you keep reading the authors you love, and you find a regular critique group. You start to notice how other writers solve the very problems you’re having. After a suitable moratorium, you go back to your neglected manuscript and realize that you know how to solve many of those problems, too.

So you solve them.

But you recognize other issues—bad habits you’d never noticed before, tendencies you’d never seen as problematic.

You make a note of these issues, take another hiatus, and get back to the business of reading and critiquing. You’ll come back when you’re ready.

KEEP YOUR FRIENDS CLOSE AND YOUR BETA READERS CLOSER

Most writers will, at some point, show their works in progress to trusted peers and mentors for feedback.

This is important for many reasons, only one of which is the actual feedback.

Beta readers help you develop your calluses for the long road ahead. They’ll get you used to hearing frank assessments of your work. They’ll help you adjust to having your flaws noted and remarked upon by others.

These tough love lessons will be invaluable when you start querying total strangers in hopes of interesting them in your writing. Even more so when you start to get reviews.

But even that isn’t the most useful function of beta readers. Beta readers help writers most of all simply by reading.

Writing can be a lonely endeavor. You spend months crafting your story, only to wonder: is anyone’s ever going to read it?

A beta reader is an answer to that question. He or she is a promise that you’re not doing the work alone. Someone’s waiting on the other side of that Dropbox folder, so you’d better switch off the television and finish your chapter.

The motivation that comes from having a reader—even one you’re bribing with pizza and beer—is not to be discounted. It presents a goal, and it fans that hope that, one day, you’ll find an even wider audience.

Meanwhile, it’s still great to have someone there to help you catch your mistakes and find your blind spots.

But don’t give your beta readers all the hard work. There’s plenty you can do on your own.

SHOUT IT FROM THE ROOFTOPS (OR JUST READ IT ALOUD)

Most of the problems in a manuscript—repeated words, unnatural dialogue, clunky phrasing, pages where nothing of interest happens—become apparent when the work is read aloud. Your ear catches the hiccups and doldrums that your forgiving eye skates past. And your ear is a better proxy for the first-time reader’s experience.

Those spots where you trip over your own wording? Revise ‘em.

The places where you bore yourself? Cut ‘em, or find a way to build in tension and action.

Reading 80,000-100,000 words aloud is time-consuming. But it’s a lot faster than the dozen-or-so silent reads that you’d need to catch the same problems. So think of that read-aloud as an investment, and promise yourself Scotch at the end.

Averse to the sound of your own voice? Even better. Just pretend it’s Idris Elba reading your work. Would he use “enthused” as a dialogue tag? No, he would not.

PUT IN FACE TIME

There comes a point when you’ve prettied up your manuscript as best you can, gotten feedback from your beta readers, and sent out some queries. Maybe you’ve even gotten some nibbles, but none of them have amounted to anything more than chapter requests.

It may be time to up your game.

There’s a whole bevy of conferences, conventions, and workshops you can attend virtually year-round. Some are places for writers to meet with editors and agents, some are venues for authors to hone their skills, and some are gatherings for fans and creators to celebrate and discuss the genres they love.

Some of these will cost more money than you’re willing to spend, and others will require time off that you don’t have. But chances are good that there’s something in your area that’s feasible for a weekend jaunt.

Case in point, I met my future editor at Worldcon in San Antonio and pitched THE BURIED LIFE to him there. A couple months later, I had a contract for a two-book deal.

Take my sample size of one and do with it what you will, but when I visited with the Angry Robot staff that weekend, they indicated that, while they usually require agented submissions, they sometimes make exceptions for authors they meet in person. I’ve heard similar sentiments from other industry professionals, too.

Now, it’s still entirely possible (and, for many people, preferable) to go through the entire process of selling a book without ever having a face-to-face meeting. But there’s always something to be said for the personal connection. It may not sell your book, but it will help you stand out above the thousands of faceless authors who are nothing more than names in an inbox. Hopefully in the best possible way.

***

Carrie Patel is an author, narrative designer, and expatriate Texan. When she isn’t working on her own fiction, she works as a narrative designer for Obsidian Entertainment and writes for their upcoming CRPG, Pillars of Eternity. Her work has also appeared in Beneath Ceaseless Skies.

Carrie Patel: Website | Twitter

The Buried Life: Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Goodreads | Robot Trading Company

Matt Richtel: Five Things I Learned Writing The Doomsday Equation

Computer genius Jeremy Stillwater has designed a machine that can predict global conflicts and ultimately head them off. But he’s a stubborn guy, very sure of his own genius, and has wound up making enemies, and even seen his brilliant invention discredited.

There’s nowhere for him to turn when the most remarkable thing happens: his computer beeps with warning that the outbreak of World War III is imminent, three days and counting.

Alone, armed with nothing but his own ingenuity, he embarks on quest to find the mysterious and powerful nemesis determined to destroy mankind. But enemies lurk in the shadows waiting to strike. Could they have figured out how to use Jeremy, and his invention, for their own evil ends?

Before he can save billions of lives, Jeremy has to figure out how to save his own. . . .

ONE: The things that ultimately can save us are the same ones that got us in this mess to begin with.

At the heart of The Doomsday Equation are a man and the computer program he created. The man is named Jeremy Stillwater. The program he created can predict war, the onset of armed conflict, and its duration. Trouble is, Jeremy is the worst person ever to predict and prevent conflict; that’s because he’s a conflict addict. He’s hostile, self-righteous, a first-class jerk. He’s alienated all the people who once believed in his genius, including his girlfriend, investors, military liaisons who once thought his program could help predict the next big terrorist attack. And, so there’s nowhere left for Jeremy to turns when his computer tells him the dire news: global nuclear war, three days and counting. In the end, Jeremy must confront his own demons – his penchant for hostility and interpersonal conflict – if he is to save the world. In this way, the books forced me to ask (and learn the answer to) a question: do our modern tools help make the world safer by protecting us from ourselves or do they make the world danger by becoming powerful extenders of our darkest leanings?

Two: Writing naughty bits is scary.

One of the antagonists in The Doomsday Equation, a near-term sci-fi thriller, is named Janine. She’s smart, well-read, philosophical, spiritual, murderous and, sometimes, horny. Sometimes, between feats of violence, she likes to relax with a little carnal action. So I decided to show one such act. My fingers blushed as I typed. I’ve written many, many hundreds of thousands of words (and five books), but never this kind of scene. I thought: will my mom read this and know I’ve done it (I figure she knows; I am in my 40s and have two children so, y’know…something happened somewhere along the line). I didn’t precisely go for it when I wrote the sex scene but I didn’t pull my punches either. I made it clear who was doing what to whom. No, I won’t tell you what page. You’ll have to read it and let me know if, at least that part of the book, strikes a proverbial nerve.

Three: What can computers already predict?

I always try to base my books in some semblance of reality. After all, what is scarier than that? So I spent time looking at how computers make predictions. They’re doing it all the time, more so by the day. So named: Predictive Analytics. It’s not so complex a concept actually, though it is a bit of an overstated one. The simple part is this: the computers look for patterns that precede an event – say a weather event or change in stock market – and then predict future events as similar or related patterns emerge. Simple, right. But a bit overstated. It’s not the same as predicting the future. It’s not the same as saying: this is what will happen. Rather, it’s the same as saying: this is what has happened when such-and-such events have occurred before. A small but powerful distinction. At the same time, predictive analytics appear all over the place, helping businesses predict demand, meteorologists weather, doctors disease patterns. The Centers for Disease Control, the world’s premier medical institution, uses our Internet habits — what we search for, what we say online — to predict the intensity and timing of a flu epidemic. Who and where are people searching for medicines, vaccines? Google calls it Google Flu.

Four: Computers can actually predict – yep, you guessed it – war. Sort of.

A real paper in the journal Nature says: yes. The paper called it “the mathematics of war.” It looked at 54,000 attacks from 11 wars and, by doing so, established patterns. What kinds of groups attack (how big, what is the nature of their relationship? What sort of social ecosystem presages attack? How many will be killed? What kind of military or strategic response can forestall such an attack). The journal proposed an equation. They called it “The Power Law.”

The real-world person behind this equation is named Sean Gourley. He’s a Silicon Valley wunderkind. His ideas helped spark The Doomsday Equation. He’s much nicer than the protagonist in the book, far more gracious, no less genius.

Five: It never hurts to ask.

Over the years (and books), I’ve gotten lots of terrific blurbs from world-class writers. On this one, I thought I’d try to get a copy to Lee Child, a guy I’ve chatted with from time to time but never reached out to for a blurb. Through an intermediary, I asked. Our mutual friend said: he’s too busy. But you could always ask him yourself. I did. Boy, am I glad. He wrote of the Doomsday Equation: “It’s a mile-a-minute, lone guy against the world masterpiece.” Thank you, Lee. This exquisite blurb I could never have predicted.

* * *

Matt Richtel is a Pulitzer Prize-winning technology reporter for the New York Times. He is the author of A Deadly Wandering and the novels The Cloud and Devil’s Plaything.

Matt Richtel: Website | Twitter | Facebook

The Doomsday Equation: Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Goodreads

March 4, 2015

Goodbye, Mookie. Hello, Mookie.

Some of you may have noted that the March 3rd release of The Hellsblood Bride has come and gone. I noted earlier that the book was canceled, though not every site carried that update — I think Goodreads was still insisting it was coming out, despite reality’s insistence otherwise. Which suggests we should be keeping an eye on Goodreads, because it may have gained sentience. I’m just saying. Weaponized book reviews? THAT SHIT IS COMING. Just you watch.

Anyway.

So, Mookie Pearl is dead.

But long live Mookie Pearl.

Because, as it turns out, I am once again in possession of those rights.

Which means, Mookie Pearl is getting a resurrection.

Lightning and fire and a smudge of the ol’ Blue Blazes around the temples. That’s right, I’m talking Cerulean, Peacock Powder, Smurf Jizz, the ol’ blue, ol’ boy.

No firm release date on this, as yet. I’ll likely give it a late-in-the-year release so as not to clog up my release schedule (there’s a lot coming out: The Harvest, Zer0es, plus the re-release of the Miriam Black books across e-book first and then print, and oh yeah, that Miriam Black novella, and hey let’s not forget that REDACTED book I can’t even talk about, yet). I think given the tenor of the book, it makes sense to aim for Halloween — so, expect a release in the weeks leading up to everyone’s favorite spookypants holiday.

Plus, that’ll give me time to spit-and-polish the sequel to my heart’s delight.

(This means I’ll be releasing both Blue Blazes and Hellsblood Bride on one day.)

You can, of course, read the opening chapter from The Blue Blazes to get a taste.

And then you have to wait.

But soon! By the end of the year. Soon.

P.S. Zer0es cover reveal tomorrow, I think, at B&N book blog.

March 2, 2015

The Toxicity Of Talent (Or: Did You Roll A Natural 20 At Birth?)

Is talent real?

I don’t know.

And for my purposes, it doesn’t matter.

In fact, I’d prefer it doesn’t exist at all.

Yesterday I wrote a ranty-panties response to that MFA creative writing teacher post — and if there’s one area of pushback to what I said, it’s that a lot of writers still believe that:

a) talent exists

and

b) talent matters.

Some of them think it matters a little, some of them think it matters a lot. The author of the MFA article seems to think it matters almost supremely — a factor significant above all others.

For my part, and your mileage may of course vary here, I think it’s irrelevant whether it exists — what I think matters is that for authors, it’s a very, very bad thing on which to focus. In fact, I’d argue you shouldn’t care about it.

At all.

Here’s why:

What Is It, Where Does It Come From, And How Do You Measure It?

The simplest definition of talent would be: “A natural aptitude.” Meaning, something intrinsic. Something self-possessed — not built up, not worked to, but some ingrained, encoded ability. Maybe it’s a flower in full bloom or maybe it’s just the seed. But it’s something internal. You can’t buy it. You can’t create it. It’s there when you start.

All right. Where, then, does it come from? If it’s innate, it’s likely something we’re born with — and already, for me, that starts ringing big bonging bells in my head because, then what? Is it genetic? Folks use “genetic aptitude” to make all sorts of specious, spurious assumptions. If it’s not in our genes, from where? Environment? Whether we’re breastfed or not? Whether we had the perfectly balanced combination of mashed peas and smushed bananas and parental neglect? Shit, maybe it’s global warming. Or–or!–maybe it’s from outer space, you guys. Alien Architects! Beaming pure talent into a select chosen few. Thanks, Venusian Astronauts!

Okay, so assuming… some part of that is accurate, how, then, do you measure it? Is it binary? YOU HAVE TALENT (checkbox) or YOU DON’T HAVE ANY TALENT AT ALL, LOSER (checkbox). Is it a spectrum? “You are 63% talented, 27% worker bee, and 10% babbling vagrant.” Is there a blood test I can take? Will Qui-Gon Jinn administer it? Or is it like in John Carpenter’s The Thing, where someone presses a hot wire into a petri dish of my blood?

Is there nuance to it? When it comes to writing, is talent singular? HE IS TALENTED WRITER. Or is there a breakdown? She’s talented with dialogue! He’s talented with description. That sentient spambot is talented at writing beautiful spam poetry. (CIALIS: A POEM. BY @OENAPJIZZ7823)

What does all this mean?

Talent Often Aligns With What We Like

Talent, as it turns out, is wildly subjective.

I have been told I am talented — I was able to read at a fairly early age, I was able to write, I wrote stories often and early. I know plenty of others who did the same, and I have been told they were talented where I was decidedly not.

Some writing professors gave me A+’s, others thought I was a mediocre genre-loving twerp.

I have seen young writers praised as talented.

I have seen talent condemned as overwrought, overdone, incorrectly assumed.

Here’s the thing: where we see talent, particularly in the arts, it’s often born of us praising the things we like or connect with. Genre writers are labeled as hacks, literary writers as the true talents. And then inside the genre, the award winners are the talented ones, the populist authors are seen as less so — they’re basically just hobos with pens, those chumps.

Mostly, we just call the things we like, and the things to which we relate, the products of talent. Everything else is something lesser. And therein lies a further problem.

Talent Is An Elitist Idea

If talent is subjective, it means the governance of and assignment of talent is done so by — who? Usually, the people in power. And here, “power” is a really hazy, gauzy idea — I don’t mean that there’s a literal LITERARY POWER COUNCIL somewhere sitting in their star chamber library on some distant asteroid. But in this I mean, other authors, bloggers, award juries, publishers. Talent becomes a thing determined by other people who are viewed as having retroactive talent by having made it to a certain point. (Talent introduces a chicken-and-egg problem: did the talent precede the success, or do we label success as a thing that came from talent because duh that’s just how it works? The overnight success rarely is. Is the talented success really talented?)

When you give that power to others to determine whether someone is talented, you risk undercutting anything that’s not in their field of vision. That can mean genre voices. That can mean diverse voices, or marginalized ones. That can mean the voices of those who haven’t sold — or, conversely, who have sold too much. (Stephen King has routinely been chided as just some popular hack while demonstrating incredible skill — or “talent,” if you subscribe to the notion.)

Talent is not just a set of moving goalposts — these goalposts do not merely move, but rather, they teleport erratically about like a coked-up Nightcrawler (*bamf!*).

Worse is when you begin to huff your own vapors. Talent is a very good way for an author to feel gloriously self-important — not just capable, but gasp, talented. Given a gift by the gods, the magic muse-breath vurped into your mouth — an emberspark of raw, unmitigated ability.

What talent means, though, is that you can very easily eliminate other authors. You can vote them right off the island because, mmmnope, they don’t have it. The gift. The spark. The talent. But if talent is subjective, isn’t that a dangerous assumption? That some have it? And others don’t?

Oh, and I’ll leave this little tidbit right here:

Professors of philosophy, music, economics and math thought that “innate talent” was more important than did their peers in molecular biology, neuroscience and psychology. And they found this relationship: The more that people in a field believed success was due to intrinsic ability, the fewer women and African-Americans made it in that field.

(That, from this article: “The Dangers Of Believing That Talent Is Innate“)

The Insecurity Of Expectation

When our son was born, we read an interesting tidbit of advice.

This advice said: “Do not call your child ‘smart.'”

I railed at this. Because, of course, my child is a genius. I’m surprised his cranium is not comically swollen in order to contain his mega-brain. If he turns out to be a bestselling novelist, Cy Young-winning pitcher, and psychic president of outer space all in one lifetime? I won’t be surprised. Of course, most parents think that about their kids, don’t they?

And then I think back:

They said I was smart.

(*hold for laughter*)

When I was a kid, that’s how they labeled me. At one point, they even labeled me — wait for it — gifted. And here’s the trick about receiving that label: suddenly, it’s something you have to live up to. Not a thing you chose. Not a thing you desired. But a tag. It’s like telling a kid, “You can jump ten feet straight up in the air because I know you can,” and then when they can’t, it becomes terribly frustrating. And any time I failed, I didn’t understand it. “But I’m smart,” I’d say. “But you’re smart,” my parents would say. A failure ceased to be a learning opportunity and instead became a deficit — an inability to live up to my potential. I was supposed to be one thing, and I demonstrated another thing.

The idea is not to tell your kids in the overall how smart they are, but rather, to praise individual efforts — to measure their actual successes and not to inflate them with expectations. Do that, and reality will callously — and with great swiftness — pop that ego balloon.

Talent is like that, I wager.

Being told you’re talented? It’s a burden. And I don’t mean some burden like — *presses back of hand to forehead and swoons* — OH WHAT A BURDEN IT IS TO BE SO TALENTED. But I mean, what a burden to live up to. Someone, somewhere, some arbiter of taste, some professor, some parent, some reviewer, has labeled you with a generic stamp of innate ability. When you fail to live up to that label, it means you have failed the thing inside you. You have taken the gift you have been given, and you have messily shat all over it.

Further, what if you are labeled as having a talent in one thing?

But really, you don’t want to do that thing?

What if you have “talent” as a musician — but you’d much rather play baseball?

Suddenly talent sounds a lot like destiny. (Another foolish, made-up idea.)

The Uncertainty Of The Impostor

The other side of this nasty little penny is:

If some people are talented, then you have to ask yourself:

Am I?

And some or all of the time you will decide, “No, I am not.”

And if we’re told that talent really matters, and that some people are born with it, we will be forced to conclude: I was not born with it. I do not possess the One Thing That Truly Matters. I am, therefore, superfucked.

And that means: “I quit.”

Because, with that, you start to feel like an impostor. Like a stowaway on somebody else’s ship — as if eventually they’ll catch you and toss you into the foam-churned seas. If you’re told “Some people have talent, and some don’t,” then you’ll start seeing OTHER PEOPLE as in possession of the Golden Apple and you’ll start seeing YOURSELF as someone who has just a regular old shitty apple. A shitty-ass who-gives-a-worm-turd apple.

Of course, golden apples aren’t real.

You feel like a Muggle, but Harry Potter wasn’t real, was it?

Writing isn’t magic. It feels like it! But it ain’t it.

Talent Is Easy — And Lazy

As a wee kidlet, it was easier to believe in Santa than it was to believe someone actually had to work to buy my presents and wrap them and hide them under the tree. Far easier to believe in the myth of the thing than the thing itself. And as a parent, I wish like hell I could believe in Santa. I wish some genial red-suited Time Lord would scoot down my non-existent chimney and unfuck the holidays and make my son’s every Christmas the best and brightest it could be. It would save me a half-dozen trips to Target, probably.

But reality is, my son gets presents because we buy them. We wrap them. We think very hard about what to buy him. And we work very hard to make the money and take the time necessary to do that. If he has a good holiday, that is in part on us: not just about the commercial side of it, but about the time and work it takes to make the day a special one.

Talent is like this, mostly.

It’s probably just a myth.

It’s shorthand. And lazy shorthand, at that.

The real deal is: work and thought and desire really, really matter.

You want to be special, but nobody is special, not really.

Work is what makes you unique, because true story: a lot of people don’t do the work.

If It Matters, It Matters Very Fucking Little

Maybe talent is real.

I don’t know.

Certainly you can see it in some areas. We call Mozart talented, and we say Salieri was a hack — though stories suggest that Salieri was no such chump, and that history is the only thing unkind to him. A kid may be able to throw a 95MPH fastball in high school. A student in elementary school may be able to pick up an instrument and play it more beautifully than an adult who has been practicing for decades.

I’ve known a few of those — artists, musicians, athletes. Folks who demonstrably excelled early on. And most of them have gone nowhere with it. A few have made careers — not newsworthy careers, but a life. None have gone on to change the world.

Someone on Facebook noted — quite correctly — that desire and effort isn’t really enough. It’s true, of course. Luck matters (though here I note that you can indeed maximize your luck — though that may be a post for a better day). Instinct exists — though I do argue instinct is a thing you can cultivate. This commenter said, again correctly, that he is older and out of shape and that no matter how much he wants it or works for it, he will never be an Olympian.

True. Sadly, woefully, almost certainly true.

But — holy shitkittens, that’s a pretty high bar, isn’t it? Olympian? You’re talking one percent of the one percent. Not just the cream on top of the yogurt — but a precise layer of perfectly scrumptious molecules atop the yogurt. We’re talking gold leaf. Let’s take the bar down a little bit, where “success” is still in play but it doesn’t necessitate being BEST OF THE BEST.

Let’s talk about running a marathon.

That is achievable. And it’s a big success. Running a marathon is no small feat, but it’s something even someone old and out-of-shape can train to — if they want it, if they work for it.

Apply that to writing:

No, you may not become a bestseller. No, you may not be a writer history remembers.

But you can still be a published author. You can still make a living off of it.

That is achievable.

Achievable in the traditional space. Achievable in the self-publishing space.

And it takes a whole lot of work — and love, and timing, and luck, and desire — to get there. (And for some, it means conquering the prejudices that exist — prejudices be they against genre writers or marginalized voices or prejudices against how you publish.)

But talent? Enh. A lot of talented writers haven’t done shit. A lot of not-so-talented writers have sold millions or billions of copies of books. Who knows? Who cares?

Okay.

Let’s say that talent is real.

We must also assume then that talent will mean nothing without work. It is a dead, inert thing unless you do something with it. It’s still a thing that must be seized, must be trained, and you still have to level up your game every chance you get. And given that talent is a subjective idea, and one that is unproven, and one that is not measurable, maybe it’s better instead to assume that it isn’t real at all. Because cleaving to talent — believing it’s real and that we must possess it — does you no favors. It only creates a false sense of what must be done or what should be possessed. It’s as invisible as a ghost, as insubstantial as a a breeze, and as noxious as a gassy dog in a small car. If you assume that work is needed to make something of your talent, then worry only about that.

Worry only about the work.

That’s the only part of this that you control. You control the time. You control you effort. You can measure how much you’re putting into something — and, eventually, you can measure how much you get out of it. You can control how much space you give it. You can authorize its importance and your devotion to it.

Reject the caste that talent implies.

Talent, if it exists, does not matter one sticky whit. Because you cannot control it.

The work, though? The work matters.

So do the work. Control what you can control. And fuck talent.

March 1, 2015

Whatcha Reading?

Once in a while, I like to poke my head in and ask:

So, whatcha reading?

Like, right now.

What is it?

Is it good?

Should we be reading it?

(My own update: I just finished reading Peter Clines’ The Fold, which is a twisty little sci-fi thriller about a group who creates a teleportation technology based on folding reality — and, duh, it doesn’t go so well. It was really good! Also just polished off Delilah Dawson’s Wake of Vultures, which is so good it’ll make you hate her because it’s too good. Weird Westy fantasy stuff, different from but in line with John Hornor’s totally amazing The Incorruptibles.)

Drop in the comments.

Tell us what you’re reading omg right now.

DO IT OR I RELEASE THE BEES

An Open Letter To That Ex-MFA Creative Writing Teacher Dude

“It it the — flame! Flames, flames on the side of my face, breathing, breathless–“

(Alternate title: Things I Can Say About That Article Written By That Creative Writing Ex-MFA Teacher Guy Now That I’ve Read It And Gotten So Angry It’s Like My Urethra Is Filled With Bees.)

Okay, fine, go read the article.

I’ll wait here.

*checks watch*

Ah, there you are.

I see you’re trembling with barely-concealed rage. Good on you.

I will now whittle down this very bad, very poisonous article — I say “poisonous” because it does a very good job of spreading a lot of mostly bad and provably false information.

Let us begin.

“Writers are born with talent.”

Yep. There I am. Already angry. I’m so angry, I’m actually just peeing bees. If you’re wondering where all these bees came from? I have peed them into the world.

This is one of the worst, most toxic memes that exists when it comes to writers. That somehow, we slide out of the womb with a fountain pen in our mucus-slick hands, a bestseller gleam in our rheumy eyes. We like to believe in talent, as if it’s a definable thing — as if, like with the retconned Jedi, we can just take a blood test and look for literary Midichlorians to chart your authorial potential. Is talent real? Some genetic quirk that makes us good at one thing, bad at another? Don’t know, don’t care.

What I know is this: your desire matters. If you desire something bad enough, if you really want it, you will be driven to reach for it. No promises you’ll find success, but a persistent, almost psychopathic urge forward will allow you to clamber up over those muddy humps of failure and into the eventual fresh green grass of actual accomplishment.

Writers are not born. They are made. Made through willpower and work. Made by iteration, ideation, reiteration. Made through learning — learning that comes from practicing, reading, and through teachers who help shepherd you through those things in order to give your efforts context.

No, not everyone will become a success because nothing in life is guaranteed.

But a lack of success is not because of how you were born.

Writers are not a caste. They are not the chosen ones.

We work for what we want. We carve our stories out of stone, in ink of our own blood.

“If you didn’t decide to take writing seriously by the time you were a teenager, you’re probably not going to make it.”

[becomes Madeline Kahn]

FLAMES. ON THE SIDE OF MY FACE.

This is one of those “provably false” things.

Because lots and lots and lots and lots of writers — successful writers, writers with books, with audiences, with money, with continued publishing contracts — did not start getting serious about writing until their 20s, 30s, 40s, and even beyond that.

Sidenote: teenagers are rarely serious about anything at all ever.

I, admittedly, was serious about writing as a teenager.

I was also serious about sandwiches, Star Wars, Ultima, vampires, masturbation.

I don’t think “what you took seriously as a teenager” is ever going to be a meaningful metric to see how the rest of your life is going to turn out. Your pubescent years are not prophecy.

“If you complain about not having time to write, please do us both a favor and drop out.”

This is one of those points he makes that almost sounds right-on. Because, sure, you shouldn’t complain about not having time to write. Wanna be a writer? Find the time to write.

Except, he’s talking to students. Students, who routinely do not have enough time. Students, who of course are going to complain because complaining is part and parcel of life. So, “just drop out” seems maybe a little presumptuous, don’t you think?

“If you aren’t a serious reader, don’t expect anyone to read what you write.”

Wait. Yes! I agree with this! If you want to be a writer, you need to be a serious reader, and so — *keeps reading the article* — oh, goddamnit. He doesn’t mean ‘serious’ as in, ‘committed to the act,’ he means ‘serious’ as in, “I read the hoitiest-toitest of books.”

Dude, I tried reading Finnegans Wake and it didn’t give me a writing career. It just gave me a stroke. I have a copy of Infinite Jest around here somewhere — oh, ha ha, not to read, but rather, to bludgeon interlopers when they try to steal my sex furniture.

Wanna be a writer? Just read. Read all kinds of stuff. Read broadly. Read from a wide variety of voices. Do not read by some prescription. Do not read because of some false intellectual rigor. Read a biography of Lincoln, then mainline a handful of Dragonlance novels, then read Rainbow Rowell before figuring out why anybody gives a fuck about Tom Clancy. Read a book about space, about slavery, about bugs, about hypnosis. Read anything and everything. Your reading requires a serious commitment, not a commitment to serious books.

“No one cares about your problems if you’re a shitty writer.”

Ah, yes, Alex, I’ll take THINGS SHITTY HUMANS SAY for $500.

Author goes onto say:

“Just because you were abused as a child does not make your inability to stick with the same verb tense for more than two sentences any more bearable. In fact, having to slog through 500 pages of your error-riddled student memoir makes me wish you had suffered more.”

Wh… whuuuuuh… why would… whhh.

That whistling sound is the dramatic whisper of oxygen keening through my open, slack-jawed mouth. Because holy fucking fuck, why would you ever say that and think anybody is ever going to feel good about it? Man, I am a huge fan of the TAKE YOUR MEDICINE LIFE IS HARD school of teaching writing, but never in a zajillion years would I suggest you suffer more child abuse because you’re a bad writer. Thanks, teacher, you’re so helpful.

That’s colder than a snowman’s asshole, dude.

I mean, dang.

“You don’t need my help to get published.”

Once again: skirting truth. It’s true that you do not need an MFA to get published. Actually, you need almost nothing at all in terms of qualifications. You don’t need a BA, either. You don’t need a high school diploma or even a GED. Publishing doesn’t care if you even graduated your preschool. Your audience has no interest in when you learned to walk.

All it cares about is if the book is good.

Now, you of course go through all the schooling not for the pieces of paper it provides but rather for the skills you learn along the way. I don’t have an MFA but I did have writing professors in college and they helped hone who I was as an author. It had real meaning, and I don’t regret it.

Of course, the author of the article goes on to say:

“But in today’s Kindle/e-book/self-publishing environment, with New York publishing sliding into cultural irrelevance, I find questions about working with agents and editors increasingly old-fashioned. Anyone who claims to have useful information about the publishing industry is lying to you, because nobody knows what the hell is happening. My advice is for writers to reject the old models and take over the production of their own and each other’s work as much as possible.”

Advice that runs considerably counter to the rest of his piece, I think — and again, provably false. You could self-publish and you could do well. You might even want to try that. But to assume that the other ways are so outmoded that they’re equivalent to buggy-whips and phonographs is absurd. Lots of good information out there on both traditional and self-publishing. You already know this, of course, but this article cheeses me off enough that I’m pretty sure my salivary glands are producing actual cobra venom.

“It’s not important that people think you’re smart.”

Finally.

Finally!

Something I agree with. In its entirety.

Writing isn’t set dressing. The words are not themselves the end of their function — they have to dance for their dinner, and so must be enlightning, engaging, entertaining. I take some umbrage with the idea of being only entertaining or pleasurable (seriously, has he actually read Gravity’s Rainbow?), and would instead correct to say:

You write to tell a story.

You don’t tell a story in order to write.

The language is there as a tool. Words are not preening peacocks.

“It’s important to woodshed.”

Once more, a moment of almost truth.

Writing is a solitary act, and a lot of the early writing you will do will be fit only for the manure pile. This is true of most writers, I think, where we iterate early (and ideally, iterate often) in order to figure out what the fidgety fuck we’re doing. We trunk novels not because we strive for perfection but because we have to learn. Of course the first stories we produce aren’t going to be sublime shelf-burners and bestsellers, just as a toddler’s first steps are clumsy drunken ones, not an elegant Olympian sprint.

But I disagree that nobody should see it. That’s ultimately what he’s saying — write in the dark, some fungal producer of literary mushroom caps. Tell no one. Iterate in shadow and shame. Which is not functional — we write to be read, and writing demands readers. We let our friends read our early work. Our parents. Other writers. We let editors take a crack when we’re at a certain level. Agents if we get that far. Working in isolation and sharing nothing often nets you nothing — we are the worst judges of our own work. Creative agitation is an essential, and that agitation comes from readers. Readers with comments. Critiques. Complaints. And, of course, compliments.

Here’s the thing. I joke that the article makes me pee bees and roll my eyes so hard that I’ll break my own neck, and it does that, a little bit. Mostly, though, it just makes me sad to think that there might be writers out there who believe these things. Particularly who believe them because a teacher has told them this. (Teachers, like parents, are supposed to be good for us. They’re supposed to help us. Ironic how often the reverse ends up true, then.)

If you want to write:

Write.

Write a lot. As much as you are literally able.

Read a lot, too. And not just one thing. But all things. A panoply of voices. A plethora of subjects.

Read, write, read, write.

And be read, in turn.

If you want schooling? Do it. If you want critique? Do it. But go in, eyes open. Do not believe in your own inherent talent, or ego, or ability. Find ways to turn up the volume. Gain new skill-points in this Authorial RPG. Level up. Don’t be complacent.

You don’t have to suffer for your art.

You don’t have to do it in some hyperbaric isolation chamber.

You don’t have to just put it out in the world, nor do you have to keep it from the world.

Find your own way.

And go with your gut.

Want it.

Work it.

Write it down.

NOW SOMEBODY SET THAT TO A COOL BEAT AND LET’S DANCE

February 27, 2015

Flash Fiction Challenge: The Four-Part Story (Final Part)

Aaaaand, FINAL ROUND.

Go, visit the page for Part Three of this challenge.

Once again we return to the four-part story you’re all choatically cumulatively writing. Your task is to go to the comments of that link above, find the third part of a continued story, and then continue it by writing the fourth and final part of that story. Meaning: it’s time to write the ending.

You have another 1000 words to do this.

Make sure to identify which story you are continuing and who the writer was.

Do not continue your own story.

Definitely do end this story — you’re writing the final of four total parts.

You can partake in round two even if you didn’t participate in round one.

You must finish your next and final entry by noon, EST, next Friday (the 6th of March).

If you can and the original author approves — please compile all the stories into the single page, and credit the original author. (That may save folks from having to track back through multiple links to get the whole story so far.)

Time to stick the landing.

February 26, 2015

Marion Grace Woolley: Five Things I Learned Writing Those Rosy Hours At Mazandaran

It begins with a rumour, an exciting whisper — anything to break the tedium of the harem for Afsar, the Shah’s eldest daughter.

A trader knows of a wondrous circus. Traveling with it is a man with a face so vile it would make a hangman faint, but a voice as sweet as an angel’s kiss. He is a master of illusion and stealth. A masked performer, known only as Vachon.

On her birthday, the Shah gifts Afsar the circus. She is captivated by Vachon, and they are swiftly bound together by a heady web of fascination, jealousy, and murder.

Those Rosy Hours at Mazandaran gives life to the Little Sultana from Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera, and takes us on forbidden adventures through a time that has been written out of history books.

You Know When You Come of Age

All writers start somewhere. No one ever arrived on the page fully fledged. In yea olden days, that process was fairly private. People wrote in the secrecy of their own homes, fingers stained with ink, shoulders hunched about their ears, until they had something worth submitting.

Nowadays, we’re not so bashful. If it’s not worth submitting, you can always blog it, self-publish or even vanity-press it. Our mistakes are there for all to see.

It wasn’t until 2008 that I seriously tried to write my first novel – just to prove I could. Everything after that has been practise. I’ve explored different genres, from horror to chick lit. I’ve fumbled my prose and played with pastiche.

With Rosy Hours, I feel as though I’ve come of age. There is a maturity to it that was missing in previous attempts. I’m not ashamed of what I wrote before, but this is on another level. I have found something that is mine.

A Little Encouragement Goes a Long Way

I published three other novels before Rosy Hours. For me, getting published has never been particularly difficult. Selling books, on the other hand, requires Sisyphean effort. My previous publishers were high on enthusiasm but low on marketing mulla.

Add to that a spell of crippling self-doubt in which I wrote a manuscript that will never see the light of day (my writing was getting worse, not better!), and you have the recipe for a quitter. I almost packed everything in. One hundred thousand words is a long slog when no one’s going to read what you write.

Ghostwoods Books really turned me around. One minute everything was crap, no point, why bother. The next the sun was shining, there’s a grin on my face, the world is a beautiful place. What a difference a year makes.

They reminded me that it isn’t all about sales. It’s about being proud of your creation. Knowing that you’ve given it the very best you can. Knowing that what you’ve written has been loved.

I’ve got my mojo back.

Moustaches are Sexy on Women

Rosy Hours is set in 1850s Northern Iran. The Shah at the time was busy selling off the country’s assets to expand his harem. One of the things I learned during my research is that beauty is extremely subjective. When I thought harem, I thought wispy Persian beauties draped in silk, dancing the seven veils.

When the Shah of Iran thought harem, he thought unibrows and coffee-stain moustaches.

It’s Really Emotional Hearing Your Characters Speak

One of the reasons I’m so excited about this book, is that it’s being turned into an audiobook.

It’s been a fascinating experience. Author and Hugo Award nominee Emma Newman has provided the voice. I’ll never forget receiving the sample chapter. Opening it up and hearing my words read back to me for the first time, the voices inside my head speaking to me in somebody else’s voice. It gave me goosebumps.

A few years of drama school and working in development have taught me that to create is fine, to collaborate, divine. I get a real buzz when art sparks art. When something I’ve written inspires someone else’s creation. After all, I was inspired by Leroux. Each piece of audio, or fan art, gives a sort of validation to the characters I’ve created. It attests that they have lived, and that their lives extend beyond what I imagined for them.

When It’s Good, It’s Easy

There’s this transcendental space, just above your head, where thoughts cease and good stuff happens. It’s like when you’re flying in dreams. You’re not thinking about flying, you’re just doing it. It’s the same with writing, there’s a zone. When you’re in it, everything is easy. The story just happens.

Rosy Hours is both the most complex novel I’ve written, and also one of the easiest. I look back at it now and I’m honestly surprised. Sometimes it doesn’t feel as though I wrote it. Sometimes I wonder where I got certain phrases from. Mostly, I don’t remember writing it.

You can’t force that zone, but when you’re sure that you have a great story to tell, the pieces sometimes just fall into place.

The story writes itself.

* * *

Marion Grace Woolley is the British author of four novels (historical, dark fantasy and LGBT) and a collection of short stories. She’s currently living in Kigali, Rwanda where — when she’s not writing — she’s an international development consultant. She’s just been appointed country head of a human rights organization, is up to her eyeballs in CVs, and is moving house on Thursday. She is fluent in British Sign Language, and plays the tin whistle.

Marion Grace Woolley: Twitter | Blog

Those Rosy Hours At Mazandaran: Amazon | B&N | Ghostwoods | Google Play | Kobo

Dave White: Five Things I Learned Writing Not Even Past

Finally, Jackson Donne has it figured out. After leaving the private investigation business, he’s looking toward the future — and getting married to Kate Ellison. Donne is focused on living the good life — planning the wedding, finishing college, and anticipating a Hawaiian honeymoon — until he receives an anonymous email with a link and an old picture of him on the police force. Once Donne clicks the link, nothing else in his life matters. Donne sees a live-stream of the one thing he never expected. Six years ago, his fiancée, Jeanne Baker died in a car accident with a drunk driver. Or so Donne thought. He’s taken to a video of Jeanne bound to a chair, bruised and screaming, but very much alive. He starts to investigate, but quickly finds out he’s lost most of his contacts over the years. The police hold a grudge going back to the days when he turned in his corrupt colleagues, and neither they nor the FBI are willing to believe a dead girl’s been kidnapped. Donne turns to Bill Martin — the only man to love Jeanne as much as he did — for help. And that decision could cost him everything.

I Could Do It Myself

That may sound ridiculous, but it is true. I’ve always had beta readers at very early stages in my novels. Seriously, like after first draft stages. Sometimes I’d show people very early chapters just to keep my confidence up. Not with this one. I wanted to try and keep things quiet, and write for myself. Screw everybody else.

When I finally got feedback from editors and readers, they were more enthusiastic than critical and there was less to fix. That taught me to trust my instincts. I could now yell DON’T TELL ME WHAT TO DO at editors. (Note: I would never yell, “Don’t tell me what to do at editors.”) Hearing the positive feedback was so important for my confidence as a writer and going forward. I don’t feel as daunted by revisions. Given enough time, I can find what needs to be fixed.

Nope. Can’t Read.

I love to read fiction. Crime novel after crime novel after crime novel. But when I’m writing, I just can’t. Too often I’m distracted or can’t follow the plot. I get nitpicky about what I’m reading. I’m never drawn to a book. Probably it’s because I’m subconsciously focused on my own book. Plots are hard to follow because I’m still working on mine.

However, for some reason, I am really enthusiastic about reading when I’m writing. I always think I’m going to be able to plow through all this new and exciting books by authors I love. Instead, they sit—untouched—on my nightstand for months.

What I can read however, is some lighter fare. I can read comics—Marvel gets a lot of my money when I’m writing. And journalism. I love sports reporting and I read a lot of that for enjoyment.

Scheduling Writing Time with a Kid Is Tough

When I wrote my first three novels, I didn’t have a kid. Heck, I wasn’t even married. I could write all willy-nilly. Nights? SURE until 1 am if I wanted. Mornings? Afternoons? Whenever the inspiration struck—I could be at that computer pounding away at the keys.

Now I have a two year old. And he naps, so that’s good. But he doesn’t always nap consistently. I have had to figure out times when Ben is distracted or when someone will watch him for me. I get a good hour or two of writing in right after work—and when I do promotional work, it’s after he goes to sleep. All right, I lied. Right now I’m typing this blog post as Ben is watching a video. BAD DAD.

But it was something I had to learn. I always wrote every day when I was single or childless, but it was easier to wait for when it was convenient. Now it’s like Chuck says, Art Harder, Mother Fucker. You can’t just wait around. You have an hour now? Use it. Get it done. That was the tough adjustment.

Retroactive Character: Who is Jackson Donne?

Jackson Donne is my series character. He is a former private investigator that was mourning the death of his fiancée, Jeanne, in the first novel. But, as I came up with the hook for NOT EVEN PAST—Jeanne is actually alive—I had to learn more about Donne himself. And some of what I learned was retroactive.

Donne is more unhinged than I had already thought. He’s not the smartest guy, and his more impulsive than expected. These realizations kind of synced with the first two novels in a way I didn’t expect. I was able to look back at those novels—and at Donne going forward.

In a way, this is my comic book novel. Some retcons, a character coming back from the dead and I’m sure some continuity issues. I love that. This book and Donne are raw to me–their edges aren’t sanded. It comes at you in a flurry, I hope. And because of that I know more about Donne going forward and how he can grow and change.

I’m Different as a Writer, and That’s Okay

How do I put this? I learned a lot about myself as a writer with this one—and I think you can see that in what I’ve learned. I’d gone away from writing novels for almost two years when I started this one, and I was afraid it wouldn’t be like riding a bicycle.

And it wasn’t.

But that doesn’t mean I couldn’t still write. But I had a different process this time around. I wrote the first 100 pages of this book and then went back and started over. I outlined my revisions. I’d never done that sort of thing before. I always just pushed through, forced it when it wasn’t there and then fixed it later. Now, I’m more patient. I’m more willing to re-work mid-novel. People ask how many drafts of my novels I write. One my first 3 books I could have told you a true number on front to end revisions. Now I go back and play much more. I tweak a lot more.

I think that’s part of growing as a writer, maturing. And I was able to do it by myself, which was very cool to me.

* * *

Dave White is a Derringer Award-winning mystery author and educator. White, an eighth grade teacher for the Clifton, NJ Public School district, attended Rutgers University and received his MAT from Montclair State University. His 2002 short story “Closure,” won the Derringer Award for Best Short Mystery Story the following year. Publishers Weekly gave the first two novels in his Jackson Donne series, When One Man Dies and The Evil That Men Do, starred reviews, calling When One Man Dies an “engrossing, evocative debut novel” and writing that his second novel “fulfills the promise of his debut.” He received praise from crime fiction luminaries such as bestselling, Edgar Award-winning Laura Lippman and the legendary James Crumley.

Dave White: Twitter

Not Even Past: Amazon | B&N | Indiebound

February 25, 2015

Gareth L. Powell: A Trilogy Of Things I Learned Writing A Trilogy

Writing a trilogy is tricky business. I just finished writing my first official one (the Heartland series, with The Harvest being the final book coming out in July), and I’m still not sure how to codify it, yet. So when Gareth said he’d like to take the bullet, hey, who am I to stop him? So, here he is to talk about what it takes to write a trilogy:

* * *

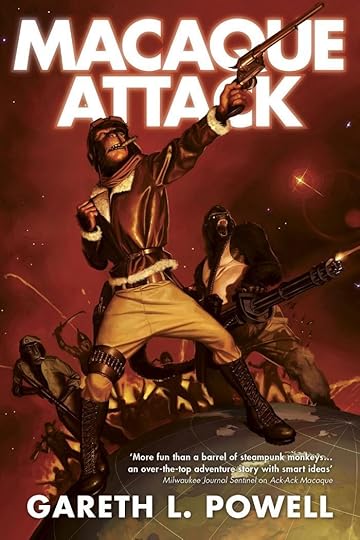

January 2015 saw the UK and US release of Macaque Attack from Solaris Books, the third novel in a trilogy that began with the BSFA Award-winning Ack-Ack Macaque in 2013, and continued with last year’s Hive Monkey. While I had previously written a couple of standalone space operas, these three ‘monkey books’ represented my first complete series, and I learned three main things while writing them.

1. CHARACTER ARCS

If you’re embarking on a multi-book epic, you need to make sure you’re writing about some compelling characters. Writing a trilogy is a huge commitment. Each of the books in the ‘Macaque’ trilogy took six months to write, which meant spending a year and a half of writing time immersed in the same fictional universe, in the company of the same fictional individuals.

And what I learned was this: if you’re going to be spending a lot of time – potentially years – in their heads, you have to give them the potential to develop and grow in interesting ways. Otherwise, you’re going to get bored of them, and if you do, you can be sure your readers will as well.

In the Macaque books, each of the characters has an arc that runs through the trilogy. For Ack-Ack Macaque, the titular simian at the centre of much of the action, that arc is a journey that takes him from loner to family man. He starts off as a traumatized escapee from a laboratory, angry and liable to lash out at the slightest provocation; and ends up (having gradually lowered his defences and allowed friends into his life) older, calmer and wiser. He goes from being indestructible and reckless to mortal and all-too-human, but gains so much along the way. He comes to understand the world, the true cost of his actions, and gathers around him a strange, barely functional ‘family’ of damaged individuals. In this sense, his story is the same one we all go through – of growing up, accumulating responsibilities and scars, and building meaningful relationships.

The other major character, Victoria Valois, is on the opposite journey. At the start of book one, she has lost her husband to a particularly brutal murderer. Through the course of the trilogy, she has to come to terms with this loss – a process made complicated by the presence of his electronic ‘ghost’, a self-aware download of his personality, taken shortly before his death. Her journey is one of shock, denial, grief and vengeance; but at the same time, it is one of empowerment. Through her pain and the situations in which she finds herself, she grows in confidence, ability and self-reliance.

These dual character arcs reflected and illustrated the main themes of the books, and allowed me to significantly change and develop the characters in each volume, creating an ongoing story over and above the main ‘plot’ of each novel. And the response I’ve had from readers has been fantastic, especially in Victoria’s case. A lot of people have been able to identify with her journey from lost and damaged accident victim to self-confident and resourceful badass.

2. CONTINUITY VS STANDALONE

With a series, it’s sometimes hard to know how much knowledge of previous installments you should assume on the part of the audience. Will everybody who picks up book three have read books one and two? How much should you recap and explain in order for them to enjoy reading it? And how much can you afford to explain before you start to bore those readers who’ve stuck with you from the beginning?

While the three books in the Macaque trilogy tell one continuous story, I also wanted to make each of them as accessible as possible to the casual reader. Therefore, each book opens with a short paragraph outlining the origin of the story’s world – a timeline where Great Britain and France merges in 1959. Beyond that, each book has its own self-contained adventure, with a beginning, middle and end, and it is the characters that provide the continuity and back story, via dialogue and moments of reflection.

I hope each book can be read and enjoyed on its own terms, but knowledge of the preceding books definitely adds to the understanding and enjoyment of the later volumes.

This is particularly true in Macaque Attack, in which characters from one of my earlier space operas [The Recollection, Solaris Books, 2011] make a surprise appearance. You don’t need to have read the space opera in order to enjoy the action, but you’ll get a lot more out of the story if you have.

3. EACH INSTALLMENT NEEDS TO CHANGE THE GAME

One of the things I was determined not to do was write the same book three times. If this was to be a trilogy, each book needed to add something significant. It had to justify its existence.

After book one introduced the world and brought the characters together, book two needed to turn everything on its head, introducing us to the darker side of our hairy protagonist, and the paths he might otherwise have taken. Then, with book three, I had to take everything up another notch, while simultaneously harking back to the beginning of book one, and the themes that had kicked everything off in the first place.

I had to provide a fitting conclusion while simultaneously tying up all the loose ends from books one and two, and bringing each character’s emotional and developmental journeys to a satisfying close.

TO RECAP:

1. Characters need to be strong enough to carry the weight of the story and hold the attention of the reader. They have to be characters we want to follow and find out more about.

2. Decide how accessible you want each volume to be for readers new to the series.

3. Each volume of the trilogy has to justify its position. It has to bring something new to the party – a new piece of the puzzle, more trouble for our protagonists, something we haven’t seen before. Think about the Empire Strikes Back and how it deepened and darkened the Star Wars universe after the bright optimism of A New Hope – every installment of your trilogy has to similarly turn the tables on the characters and the reader, taking the plot, the tension, the stakes, and the development of the characters themselves, up to a whole other level.

* * *

Gareth L. Powell is an award-winning science fiction and fantasy author from the UK. His third novel, Ack-Ack Macaque, co-won the 2013 BSFA Award for Best Novel (tying with Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice). He has also had shorter work featured in Interzone and 2000 AD. You can find more of his writing advice at www.garethlpowell.com, or follow him on Twitter at @garethlpowell.