Corey Lee Wrenn's Blog, page 5

January 9, 2022

Should Vegans Be Organ Donors?

Her logic? Organs would probably be donated to nonvegans who would go on to eat, wear, and use other animals for years to come. Saving human lives would mean ensuring nonhuman deaths, potentially several hundred nonhuman deaths, within those human lifetimes.

My colleague is a deeply compassionate person and is devastated by humanity's violence against other animals. Her heart (excuse the pun) is in the right place. Practically speaking, however, this approach is debatable, to say the least.

First, Nonhuman Animals are often killed so that their organs can be harvested for humans. I would much rather pass on my unneeded organs that would otherwise be cremated and spare a pig or a monkey.

Second, letting nonvegans die supports the noxious stereotype that vegans are misanthropes.

Most fundamentally, however, it is not fair or ethical to punish individuals for structural problems. By my colleague's logic, humans in all sorts of unfortunate situations should be abandoned: victims of genocide, survivors of domestic violence, cancer patients, and more. Most of them are not vegan. Should vegans withhold resources and support? Certainly not.

The vegan community too often makes the mistake of conflating individuals with systems. Just as it would be problematic for vegans to kill obligate carnivores (like cats) to prevent them from eating the flesh of cows, pigs, chickens, fishes, and others whose bodies comprise "pet food," we would not want to let humans in need die because they might not be vegan.

Often, vegan advocates assign much more agency to individuals than is appropriate. Everyone enjoys some degree of "choice" and "free will," but the choices available to us and our capacity to recognize them are greatly dependent on preexisting structural conditions. Placing blame on nonvegans for consuming Nonhuman Animals, in other words, is a fraught enterprise. Speciesist industries have amassed considerable power which is applied to all major social institutions to reproduce this power and normalize a deeply unequal system. It is the job of vegans to disrupt this normality, not to punish those who fall victim.

Readers can learn more about sociological vegan ethics in my 2016 publication, A Rational Approach to Animal Rights.

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.

Is It Vegan to Eat Mock Meats?

My answer? We might ask the reverse of the flesh-eater. If one is in favor of eating "meat," why would they eat flesh-based hot dogs? Why not gnaw on a joint of flesh directly? Veggie dogs and flesh dogs are both essentially protein links that are heavily seasoned and conveniently shaped for easy and tasty eating. Neither of them look, smell, or taste very much like a pig's corpse.

That said, the ubiquitousness of mock meats is culturally relevant in the same way as pornography is to women. The mock meat industry and the pornography industry exist as symbolic representations of violence against vulnerable groups. The consumption of these products has become detached from the actual harm women and other animals experience in slaughterhouses and film sets, but the prevalence of these products normalizes sexist and speciesist oppression. There is reason, then, to be at least somewhat critical of mock meat as a cultural matter. Purchasing a McPlant vegan burger from McDonalds, for example, could symbolically support hamburger culture and the notion that Nonhuman Animal bodies are food.

But is this a battle worth fighting? Mock meats do not take up a huge part of the vegan diet, and most people who remain vegan long enough transition off of them. Mock meats and analogs are usually marketed to flexitarians. For that matter, mock meats, while convenient, are frequently expensive and unhealthy. For those living in food deserts and underserved communities, they're also difficult to source for most.

It is also likely that, in the future, mock meats will become culturally detached from the Nonhuman Animals they are supposed to be mimicking. The objectification and commodification process is a sophisticated one that easily removes the "person" from the product. For most consumers who have not had their consciousness raised (which is true of most nonvegans), Nonhuman Animal products are already shaped and flavored in a way that removes them from the being they once were. Few are consciously aware of the pig behind the pork, for instance. Hamburgers, by way of another example, were once muscles from living, breathing persons, but marketing works hard to eliminate that guilt-inducing, not-so-pleasurable association.

Few people really, truly do think about what's in processed food. Food consumption is a socially constructed behavior. Foodways are structured to encourage mindless eating, eliminate critical thinking, and manipulate our choices. If this happens so seamlessly for actual animal products, then plant-based analogs will probably absorb fully into unconscious consumption patterns.

Most mock meat products, just like "real" meat products, are shaped, flavored, and textured to encourage consumption. They no more resemble Nonhuman Animals than potato chips resemble potatoes, or fruit punch resembles fresh fruit. It is all more or less processed junk that appeals to human propensities for fat, sugar, and carbohydrates.

I would be remiss, finally, if I were to overlook the cultural role of mock meats outside of the West. Buddhists have been creating soy- and wheat-based protein products for centuries. It is a practice also based on ethics, and mock "meats" are understood to be foundational to living non-violently. Western markets may have corporatized plant-based proteins (and The Vegan Society actually encourages the development of animal-free alternatives),1 but, long rooted in Asian traditions, their history is much older. Sweeping rejections of mock meats as inherently unethical run the risk of ethnocentrism.

So, to answer your question, Mom, if we're talking about mock meats that strongly resemble the corpses of other animals, this is problematic in the context of a deeply speciesist society. However, if we are talking about chunks of protein that are shaped and flavored for palatability and don't particularly resemble anyone, then these are foods we need not be especially worried about.

1. The definition of veganism according to The Vegan Society (emphasis added): "A philosophy and way of living which seeks to exclude—as far as is possible and practicable—all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals for food, clothing or any other purpose; and by extension, promotes the development and use of animal-free alternatives for the benefit of humans, animals and the environment. In dietary terms it denotes the practice of dispensing with all products derived wholly or partly from animals."

Readers can learn more about the politics of veganism in my 2016 publication, A Rational Approach to Animal Rights.

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.

December 18, 2021

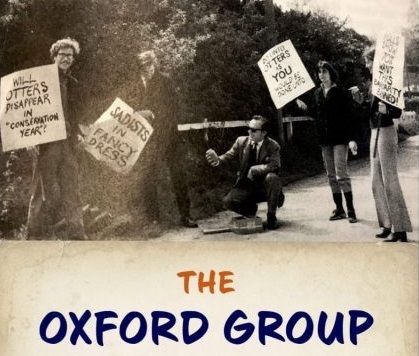

Collaborating Against Speciesism: The Oxford Group and Social Innovation

Most Nonhuman Animal rights historians have heard tell of the mythical Oxford Group, a small group of Oxford philosophy graduate students, their partners, and a smattering of associated scholar-activists responsible for some of the first and most influential advances in modern anti-speciesist thought. Most Nonhuman Animal rights academics and activists, for that matter, are familiar with the work of Oxford star and movement ‘father’ Peter Singer. Yet, despite this notoriety, few are actually familiar with the inner workings of the group, nor the development of Singer’s work in context. What was it about Oxford that made this magic happen? What was it about the philosophical discipline at that time? What about the group dynamic itself? In The Oxford Group and the Emergence of Animal Rights, longtime Nonhuman Animal rights theorist Robert Garner and scholar-activist Yewande Okuleye bring substance to the hazy mythology surrounding the mid-20th century incarnation of Western Nonhuman Animal rights. Admirably, they do so before the knowledges and memories are lost to the ages, as the original members are well into their golden years with some having already passed.

The aim of this project is twofold. First, the authors seek to explore Michael Farrell’s sociological theory of collaborative groups. It is argued that such collectives pass through predictable stages and with particular characteristics that culminate in creative and innovative output that could only be possible as a result of the group membership. Members of the Oxford Group exemplified this magic formula with their multilayered entanglement and mutual inspiration. They ate together, lived together, protested together, and, of course, worked and studied together. Through many intimate conversations and key writing collaborations, a new understanding of Nonhuman Animal rights was developed, one that would go on to majorly transform advocacy organizations, campaigning strategy, public policy, and academic thought. For the most part, then, Farrell’s theory seems well suited to explaining the experiences and output of these pioneering anti-speciesists.

The second aim of the project is perhaps more interesting to the Nonhuman Animal rights community: Garner and Okuleye’s oral history method preserves precious theoretical and activist processes for future generations. In the fast-paced push for Nonhuman Animal liberation, too little time is reserved for recollection and taking stock. There is much to learn from these interviews, such as how to successfully contend with resistant institutions and unreceptive publics. We also learn how to take advantage of political opportunities as they arise such as the moral turn in the philosophical discipline, the democratization of the academe, and the success of the American Civil Rights movement.

These interviews also teach us about the many contributions of women thinkers, notably that of Brigid Brophy and Ros Godlovitch, both of whom had a huge influence on Singer’s work (culminating in his seminar Animal Liberation in 1975). Unfortunately, the history books frequently marginalize or erase women’s contributions, but Garner and Okuleye’s oral history approach allows women to speak for themselves (supported by their male allies who were there in the trenches with them and can vouch).

The Oxford Group will be of considerable importance to the Nonhuman Animal rights annals and presents a perfectly useful oral record of a highly endangered activist and scholarly history. Perhaps more importantly, it illustrates to activists and scholars alike the dramatic potential for a small group of people who click to move mountains.

April 11, 2021

Vegan Geographies in Ireland

Ireland today is stereotyped as a country that eats a lot of meat and dairy products. However, Ireland is actually not much different from other Western countries in this regard. For that matter, for much of Ireland's history, its people ate nearly vegetarian and sometimes nearly vegan diets.

Historically, Ireland was a cattle-raiding society, and cows represented wealth and power. As such, they were far more valuable alive than dead. Until the modern era, most Irish people ate very few animal products given their expense. Under colonialism, this diet became even more restrictive, as the Irish peasantry were pushed off the land to make way for cows and sheep and most animal products were exported to feed Britain and its growing empire. Some vegetarian reformers of the 19th century recognized that the colonial exploitation of nonhuman animals was greatly responsible for the suffering of Irish humans.

My chapter in Dr. Laura Wright's Routledge Handbook of Vegan Studies explores this history of vegan politics in Ireland. The legacy of both traditional Gaelic vegetarianism and restrictive colonial vegetarianism highlights the fascinating (and tragic) relationship between colonialism and speciesism. Ireland is more than just a "land of meat and potatoes"; it has much to contribute to contemporary vegan studies.

Read the chapter here.

Readers can learn more about Irish vegan studies in my 2021 publication, Animals in Irish Society: Interspecies Oppression and Vegan Liberation in Britain's First Colony.

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.

March 18, 2021

The Extraordinary Monks of Skellig Michael and the Human/Nonhuman Boundary in Early Ireland

Little is known about the monks who once inhabited this place, but their inhabitation appears to be consistent with ascetic practices typical of early Christianity. The monks deliberately chose the site in order to eschew the comforts of civilization. Life on this slippery, cold, isolated craggy island made day-to-day existence precarious at best (skeletal analysis of the monks interred in the lonely monastery cemetery attests to this).

Monks would have absorbed into the ecosystem, preying on seabirds and fishes, tending to small gardens, and collecting rainwater. Respite was found only in beehive huts constructed out of the island's copious rocks, returning the practitioners to a cavernous, primordial existence.

As an animal studies scholar, I wonder whether this eschewing of civilization for precarious living on the skellig was an intentional troubling of the human/nonhuman boundary. In the medieval era of Europe, social hierarchies were still very much under construction, and human supremacy was not yet solidified. It would not be until Norman colonization several hundred years later that the blurred boundary between humans and other animals would cement in Ireland. Indeed, the Normans actively sought to rein in the wayward Irish Church with the installation of various new laws to regulate social behaviour.

As Western society transitioned from animist paganism to anthropocentric Christianity, the Skellig Michael outpost (which survived into the 1300s) offers a fascinating glimpse into the social construction of humanity and the permeability of such a project.

Read the full article now published with the Irish Journal of Sociology here.

January 2, 2021

How to Celebrate the New Year the Vegan Feminist Way

As each new year unfolds on December 31st and January 1st bringing millions to contemplate new beginnings, the same period marks the annual massacre of marginalized nonhumans. Free-living animals, domesticated animals (such as dogs and horses), and even human children are traumatized, harmed, or killed by fireworks. In the United States, where fireworks are also discharged on July 4th, the number of accidents can exceed 10,000 each year.

Most of these victims are children. The number of nonhuman victims is, of course, unknowable, but presumably many times that. Following the 2021 celebrations in Rome, the bodies of hundreds of roosting starlings were found dead or dying on the streets as the sun rose on January 1st.

The fascination with fire, noise, gunpowder, and other explosives marks the practice as distinctly masculinized. The entitlement to the sky and landscape for the pleasure of a relatively small group of people is also patriarchal.

Fireworks may be clearly macho, but other forms of aerial celebrations demark anthropocentrism in our relationship to Nonhuman Animals and the environment. Balloon and lantern releases, while much more peaceful, cause horrific silent suffering for the animals who ingest the remains when they fall to earth or sea. Glitter and plastic confetti, likewise, collect in ecosystems (and digestive systems), slowly suffocating land and animal bodies. Closer to the ground, bonfires can set unsuspecting shelterers ablaze, such as hedgehogs and owls. They also run the risk of starting wildfires, a "natural disaster" that claims millions of lives every year.

Must we destroy and litter in order to celebrate? New Year's Day is part of the larger yuletide season in which the western hemisphere enters a period of rest, death, and decay. As the spring returns, new birth and growth begin with another rotation around the sun. Perhaps this explains humanity's penchant for grievousness at times of celebration. Renewal requires destruction. Yet, while there may be an element of necessity to this process in the natural world, in the cultural world, we can certainly sustain one another through the process in communal, less violent means.

One of my favorite ways to celebrate is with vegan food! On the desirability of this practice, most of us, human or not, can agree. I often leave bits out for the animals in my community to share. We can make our celebrations opportunities for inclusion and togetherness, rather than another opportunity to terrorize other animals.

Neopagans and modern witches often leave offerings of food for the "fae" as part of their ritual practice. Faeries are, of course, fictional representatives of the seemingly magical unseen workings of the natural world outside our door. When I leave squash or berries out in the evening, in the morning they are gone. Was it the fae? A fox? A hedgehog? It's fun to imagine.

A witch feeding her 'familiars'

A witch feeding her 'familiars'Although paganism often practiced celebrations that were violent to other animals (including animal sacrifices, feasts of animal flesh, ceremonial "hunts," and wildlife-threatening bonfires),1 the pagan way also encourages communion. As Christianity colonized the West, the animistic pagan lineage, a threat to the newly establishing order, was through to survive in women. Witches were believed to be closely bound to other animals, as both represented the wild, potentially dangerous, natural world. Women's relationship with other animals was thought highly suspicious, in fact. The stereotype of the "crazy old cat lady" is a vestige of this distrust of independent women who treat other animals as persons and reject traditional, patriarchal institutions like marriage and child production.

The witch's new year begins at Samhain (literally "November" in Gaelic). Samhain Oiche2 ("Halloween" or "Samhain's night") is the traditional day of celebration. New Year's Day came to be celebrated on January 1st with the spread of Roman culture across the West. It is a Christian and colonial imposition. How fitting that the witch's new year, November 1st, also falls on World Vegan Day.

Caring for other animals and building relationships with them, both inside the home and outside, is an act of vegan feminist resistance. By celebrating the new year with attentiveness to others in our community, we can make the yuletide truly a season of rest and rejuvenation. Forgo the fireworks and feed your familiars!

1. Stonehenge, a neolithic site designed to celebrate the winter solstice and new year is now known to be a major site of animal sacrifice and feasting given the vast number of butchered bones left behind.

2. Gaelic is sure fun to pronounce! Samhain Oiche should be read as "sah-win ee-heh".

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and is a member of the Research Advisory Council of The Vegan Society. She has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute and has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Environmental Values, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Dr. Wrenn is Lecturer of Sociology. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology with Colorado State University in 2016. She received her M.S. in Sociology in 2008 and her B.A. in Political Science in 2005, both from Virginia Tech. She was awarded Exemplary Diversity Scholar, 2016 by the University of Michigan’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. She served as council member with the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section (2013-2016) and was elected Chair in 2018. She serves as Book Review Editor to Society & Animals and is a member of the Research Advisory Council of The Vegan Society. She has contributed to the Human-Animal Studies Images and Cinema blogs for the Animals and Society Institute and has been published in several peer-reviewed academic journals including the Journal of Gender Studies, Environmental Values, Feminist Media Studies, Disability & Society, Food, Culture & Society, and Society & Animals. In July 2013, she founded the Vegan Feminist Network, an academic-activist project engaging intersectional social justice praxis. She is the author of A Rational Approach to Animal Rights: Extensions in Abolitionist Theory (Palgrave MacMillan 2016).

Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.

December 19, 2020

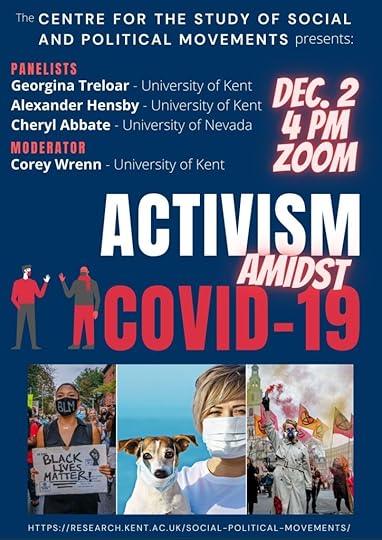

Activism Amidst COVID-19

On December 2nd, I moderated a panel on UK/US activism in the midst of COVID-19 as co-director of the Centre for the Study of Social and Political Movements. My panelists included Dr Alex Hensby, co-director of the Centre, graduate student Georgina Treloar, Dr Ellie Jupp, and my colleague Dr Cheryl Abbate of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Unfortunately, I was not able to record the event, but a fascinating discussion on astounding resilience in social justice spaces was offered. Some movements, like environmentalism, have taken a real hit in mobilization under the pandemic, but others, like Black Lives Matter, have experienced an upsurge in public and media attention.

COVID has also inspired new movements, notably the mutual aid movement in the UK, a community-organized response to inequality, vulnerability, and need when state measures have failed. We also discussed the animal rights movement, which, strangely, has not garnered anywhere near the attention that would be expected given the speciesist origins of the pandemic.

Lastly, our panelists reported on a clear intersectional theme running through various movements. The animal rights movement, in particular, has worked to raise the profile of racial injustice in food production, specifically with regard to ethnocentric racism against Chinese persons and the disproportionate impact of COVID infection in Latinx slaughterhouse communities.

Readers can learn more about intersectional activist politics in my 2016 publication, A Rational Approach to Animal Rights. Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.

Brexit, Dog-knapping, and Otherized Dogs of the EU

In the UK, the demand for "purebred" dogs and puppies has risen so sharply under COVID that "breeders" are unable to keep up and dog-knapping has skyrocketed. Dogs are literally being stockpiled for the holiday shopping season. In fact, some criminal operations have abandoned the drug trade for the more lucrative dog trade. Purpose-bred and stolen dogs can bring in thousands of pounds apiece to well-meaning "customers" who have been socialized to see living persons as commodities.

Meanwhile, millions of dogs and cats suffer and die for want of home in nearby Eastern Europe, Eurasia, and parts of the developing world where the long shadows of war and colonialism continue to wreak havoc on the world's most marginalized. In a capitalistic world in which the lifeworld becomes commodified, animals living without homes outside of Britain's kingdom are thought bottom-shelf at best and discards bound for disposal at worst.

I adopted my beautiful intersex and deaf dog Mishka with her different colored eyes and extra toes from Bulgaria this summer after my beloved cat Keeley died. I love her quirks--they are what makes her an individual and not a mass-produced product of consumption. Unfortunately, postmodern life encourages us to construct our identity through the things we buy, own, and display. This is bad news for quirky dogs like Mishka. Indeed, dogs are objectified in the cruelest of ways in order for humans to express themselves with canine commodities.

Capitalism encourages us to charge fashionable breeds to our credit card but abandon unfashionable mixed breeds to the gas chamber. Ironically, even pure breeds find themselves in the disposal stage of this consumption cycle, often when their expression of individualism clashes with their object status (for instance, when they grow out of puppyhood or exhibit "bad behavior").

The nexus of identity, consumption, and right-to-life takes on new meaning in Britain's current political situation. Identity is more than what we consume, it is also defined by the borders of the nation-state. Britain's exit from the EU has highlighted that the British identity is perceived by the dominant class to mean native-born, Anglo, and white. This identity is also perceived to be under threat by non-British "others" who are thought to challenge the economic privileges of the dominant class.

It might not surprise readers to know that the period of intensified British dog breeding also coincided with its period of imperialism. Defining "us" and "them," "civilized" and "savage" was exemplified in bordermaking, colonial expansion, and "breeding."

As outsiders and "mutts," curs like Mishka are at a distinct disadvantage compared to "British" dogs and cats who are in such high demand they are now being stolen for resale. Not only are they rendered "foreign," but they face borders now shut to "others." It is not clear how animals from Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, and other parts of the EU will fare once free movement is brought to a halt. Rescue operations in these countries have relied on adoption in Britain to save thousands of lives each year. Brexit's nationalistic anti-immigration platform not only means immense suffering for human "others," but also for nonhuman "others."

When capitalism is given unrestricted reign over the lifeworld, the sad result is that inequality festers. Identity divides, and separation becomes justification for unequal distribution of resources and care. Although less recognized, Nonhuman Animals are perhaps the most vulnerable to these politics of the nation-state. What if we defined ourselves not by our nationality and not by the things we consumed? This is the type of radical work we need to engage to truly challenge the injustices facing dogs, cats, and other animals.

Readers can learn more about the nationalist politics of animal rights in my 2021 publication,

Animals in Irish Society: Interspecies Oppression and Vegan Liberation in Britain's First Colony . Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.

July 3, 2020

Gender and Victorian Animal Advocacy

Although the nonhuman animal rights movement in the West is frequently framed by activists and remembered by historians as gender-neutral, Donald’s (2020) Women against Cruelty (which examines meeting notes and campaigning documents reaching back to the movement’s founding in the early 19th century) demonstrates just the opposite. Women’s affinity for anti-speciesist activism within the context of a prevailing sexism which pitted all female pursuits as lesser-than would prove a difficult hurdle to surmount with regard to social movement resonance. This is not to reify or reduce women’s contributions. Women against Cruelty catalogs a diversity of feminine and feminist approaches to advancing the interests of nonhuman animals: some religious, some scientific, and some intersectional. Many women favored educational outreach, while others relied on rational debate, shocking images, direct intervention, and legal resistance.

Donald showed that women’s efforts in some ways discredited the movement through feminine associations, but, in other ways, women also buoyed it with their consistent and energetic support. Women, it is clear, existed as the movement’s foundation, providing critical insight, labor, donations, and tactical innovations. As Donald uncovers, women consistently made up the majority of various organizations’ memberships as well. However, the strict gender norms of Victorian Britain ensured that their desire to participate in the public affairs of anti-speciesism would be difficult to reconcile with their expected domestic role as caretakers (and their supposed natural affinity to other animals, a connection that many women saw as a strength but many men saw as a reason to discredit them). The Royal Society for the Protection of Animals (RSPCA), for instance, routinely confined women’s participation and restricted their leadership in campaigning.

To an extent, the tension between feminine and masculine social spheres actually reflected a tension between religiosity and the changing mores of the Industrial Revolution. Activism of the 18th and early 19th centuries was imbued with Biblical doctrine, but adherence to this approach would diverge under the growing influence of capitalism. Women, responsible as they were for upholding society’s morals, became agents of a romanticized Christian vision of equality and compassion, while men, privileged with the duty to advance society through industry and politics, became immediate opponents given the importance of speciesism (and other forms of domination) to this agenda. Thus, on one level, women and girls policed speciesist cruelty, but, on another, they also came to police the unchecked power of men who increasingly pushed the boundaries of social order through conquest, colonialism, and science. The treatment of nonhuman animals, in other words, came to symbolize the uncomfortable and monumental transition into modernity.

Read the full review here.

Readers can learn more about the history of women's activism in my 2019 publication,

Piecemeal Protest: Animal Rights in the Age of Nonprofits

. The beautiful cover art for this text was created by vegan artist Lynda Bell and prints are available on her website, artbylyndabell.com.

Readers can learn more about the history of women's activism in my 2019 publication,

Piecemeal Protest: Animal Rights in the Age of Nonprofits

. The beautiful cover art for this text was created by vegan artist Lynda Bell and prints are available on her website, artbylyndabell.com.Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.

June 28, 2020

Is Sociology Ready to Take Animals Seriously Now?

Originally published on Everyday Society, British Sociological Association; photo by Jo-Anne McArthur.

Originally published on Everyday Society, British Sociological Association; photo by Jo-Anne McArthur.

Since it began to gather momentum at the turn of the 21st century, the sociological study of animals and society has struggled for legitimacy. Although some sociology programs are beginning to provide courses on human/nonhuman relations, they remain sparse and elective. Academics and graduate students who specialize in the subfield have expressed experiencing considerable stigma (nearly half of animal studies scholars according to a recent study) (O’Sullivan et al. 2019). In graduate school, my own advisor suggested that I downplay my animal focus and sell myself as a social movement scholar. Publishing is no less frustrating, as any topic even remotely related to animals is subject to redirection by editors and reviewers to Society & Animals, arguably the journalistic ghetto for animal scholars where no one in mainstream sociology would realistically ever come across our research.

The devaluation of our work frankly boggles my mind. The climate change crisis worsens by the day with each record-breaking temperature, each melted iceberg, and each species lost to extinction. This is a crisis brought on, to an enormous extent, by animal agriculture via the heavy production and utilization of oil, soybeans and other fodder, water, land, transportation, and other resources necessary to sustain meat, dairy, eggs, and other animal products. Researchers are also pointing to this strain on the environment as the reason for shrinking wild spaces and subsequently greater contact between humans and free-living nonhuman communities. As COVID-19 and hundreds of other zoonotic diseases have demonstrated, humanity’s oppressive relationship with other animals is not only dangerous for nonhumans, but for humans as well (particularly vulnerable folks such as the very young, the elderly, those with disabilities, those living with limited material means, etc.).

Perhaps the COVID-19 crisis will finally bring home the fact that human societies are deeply and consistently shaped by our relationships with other animals. The pandemic has disrupted all that sociology holds dear, from major social institutions to the most minor of social interactions. As such, sociologists cannot afford to continue ignoring and devaluing the nonhuman factor in human social life. At the policy level, the task is formidable, but as the global response to COVID-19 has indicated, big change can happen fast when the impetus is there.

Governmental bodies will need to cease subsidizing animal agriculture and other animal-based industries, which are both unsustainable and inherently violent to animals and the earth on which we all reside. Instead, agricultural agencies will need to immediately begin transitioning farmers toward sustainable, plant-based production. Neo-colonial practices that spread Western dietary practices, entrench colonial regions in animal agriculture, and fan food insecurity must be challenged. Much of the non-Western world has traditionally relied on plant-based consumption, a diet that has been gradually undermined by Western capitalist expansion. Now is the time to reimagine our relationship with other animals and critically reassess our consumption patterns.

For sociologists, we must begin to include nonhumans in our research, not just as variables, but as sentient beings who, like ourselves, have a stake in our society’s present and future. At the very least, we can begin to lend support and recognition to the study of animals and society, as it will only grow more pressing in the coming years.

References

O’Sullivan, S., Y. Watt, and F. Probyn-Rapsey. 2019. “Tainted Love: The Trials and Tribulations of a Career in Animal Studies.” Society & Animals 27 (4): 361-382.

Corey Lee Wrenn's Blog

- Corey Lee Wrenn's profile

- 46 followers