Carly Findlay's Blog, page 25

December 29, 2020

Dr Dinesh Palipana is a doctor of many talents

Dr Dinesh Palipana OAM works in the Emergency department of the Gold Coast University Hospital. It’s the busiest emergency department in the country, and Dinesh loves his job. Every single day is different. He could be starting your day with someone who’s having a stroke or a heart attack, or treating a kid who’s fallen off a bike and broken their arm.

Image: Dr Dinesh Palipana, who is a man with brown skin, wearing blue hospital scrubs, smiling.

Image: Dr Dinesh Palipana, who is a man with brown skin, wearing blue hospital scrubs, smiling.He acquired a spinal cord injury in a car accident in 2010, when he was 24. He was completing his medical degree at the time, and returned to study after a long period in hospital and then rehabilitation.

Dinesh’s spinal cord injury affects his fingers and everything below his chest. He has home support, which comprises “a team of awesome guys” and his Mum, who he says is his “biggest supporter”. Getting ready before work takes some time. “We’re like a big family and we make we make it happen.”

Dinesh can do the majority of his job independently, thanks to support from his colleagues and also Job Access – the Federal Government program that funds accessibility provisions in the workplace. The Gold Coast University Hospital has made modifications for Dinesh to help him do his work – and these modification benefit not just him but other patients and their families, and current and future healthcare staff too. “If there’s a heavy door, and you make it automatic that benefits everyone”, Dinesh says.

Even though he started working as a doctor in 2017, and was named Junior Doctor of the Year at the Gold Coast University Hospital in 2018, he has encountered some unconscious bias and low expectations from some within the medical profession. But his Emergency department colleagues are supportive, and he has had wonderful interactions with his patients.

“My patients have been amazing”, Dinesh says. “Every single one of them has been so positive and supportive and we’ve had amazing journeys together, when they’re going through such a hard time.”

He’s also able to give other patients – and their families – hope, particularly if they’re in similar situations to him, like experiencing chronic illness and disability.

Dinesh is the first quadriplegic doctor to graduate from medical school in Queensland and the second in Australia. While he’s paving the way for future doctors and healthcare workers, why did it take so long?

Dinesh thinks it’s because when it comes to disability, society takes a deficit-based approach, looking at what people can’t do. “We will look at the deficits, rather than the strengths of people”, he says. “But we need to play to these people’s strengths and foster that.”

Before he had the accident, he didn’t know a lot about disability at all, and he’s ashamed to say, he didn’t know how to think and talk about disability either.

“Even before I had the injury myself, I had no idea what it involved to be someone with spinal cord injury, I had no idea what their life looked like, and I kind of had no idea what their capabilities were.”

Now he’s a strong advocate for medical students and medical workers who are people with disability, and wants to see better supports for them, as well as better education around disability in medical school.

Dinesh co-founded Doctors with Disabilities Australia – a disability-led organisation that advocates for people with disability working in the medical and healthcare profession. The organisation aims to eliminate the physical, attitudinal and systemic barriers people with disability experience in medicine, create resources for doctors and medical students, and also provide mentoring and peer support within the profession.

Dinesh co-founded Doctors with Disabilities Australia with Dr Harry Eeman and Dr Hannah Jackson – who are both people with disability.

“The three of us thought there’s a lot of there were a lot of policy barriers then for medical students with disabilities. This is four or five years ago.”

Dinesh notes some big changes since Doctors with Disabilities Australia was founded.

“The Australian Medical Association Queensland Council has just passed a position statement saying that we support an inclusive medical profession, both employment and education and that we support diverse group of abilities. The body that provides policy guidance to medical schools is starting to do that now as well.

“In such a short period of time it’s come through a fair, fair amount of change. When we saw that we wanted to do something about it, and we founded this organisation and started advocating, and we’ve we’ve made progress.”

Outside of working at the hospital, Dinesh is incredibly busy. He is the doctor for the Gold Coast Titans physical disability rugby team. He runs a research project in spinal cord injury with a dedicated team of people. He’s also studied law in addition to working as a doctor, and has recently been admitted as lawyer.

And he engaged to be married. Dinesh and his fiancé Rachael met working in the Emergency department. Rachael is a nurse. But they haven’t set a date for the wedding yet. “We’re just chilling. I figured I made the biggest step now”, he laughs.

Dinesh is hopeful, and he’s grateful, and he will continue to advocate for better access and inclusion in medicine.

“If we see some injustice in the world, or something worth fighting for, we need to speak up”.

This piece was written for the International Day of People with Disability website. An edited version is here.

Since writing this piece, Dinesh has been named Queensland’s Australian of the Year for 2021.

Image: a doctor, in a hospital ward, monitoring a patient’s foot. The doctor is looking at a screen. .

December 27, 2020

Response to Diving Into Glass by Caro Llewellyn

Content warning: disability slurs, allusion to violence toward disabled people.

The below piece was written and then edited for The Stella Prize website, as part of their response to the 2020 shortlisted books. It was never published there.

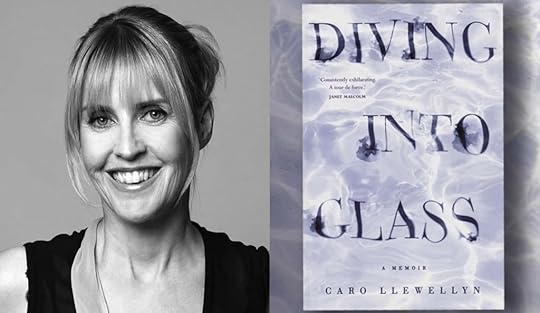

Image: A black and white photo of a woman’s head and shoulders and a book cover, side by side. The woman has fair hair framing her face, fair skin and a wide smile. She’s wearing a dark sleeveless top. The book cover depicts a pool of water – pale blue and white. It’s got the text “Diving Into Glass” written in large darker blue capital letters, spanning from the top to 3/4 down, and “A memoir Caro Llewellyn” in smaller capital letters at the bottom of the cover. “Consistently exhilarating. A tour de force – Janet Malcom” is quoted towards the top left.

Image: A black and white photo of a woman’s head and shoulders and a book cover, side by side. The woman has fair hair framing her face, fair skin and a wide smile. She’s wearing a dark sleeveless top. The book cover depicts a pool of water – pale blue and white. It’s got the text “Diving Into Glass” written in large darker blue capital letters, spanning from the top to 3/4 down, and “A memoir Caro Llewellyn” in smaller capital letters at the bottom of the cover. “Consistently exhilarating. A tour de force – Janet Malcom” is quoted towards the top left.Caro Llewellyn’s Diving into Glass (Penguin, April 2019) was a daring choice by the Stella Prize judges. The book took her more than fifteen years to write, and she told me it was very challenging to write such a personal story.

Part memoir, part biography of her late father, Richard Llewellyn AM, the book strongly focuses on disability – Richard’s disability as a result of acquiring Polio when he was 20, and Caro’s own diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) when she was 44. The book also details the minutiae of her often difficult early life growing up in Adelaide, various romantic relationships, the birth of her son when she was 23 and becoming a single mother at 24, and her career. Caro also writes about her mother, writer Kate Lewellyn, who at times, had violent outbursts. Her parents met when her Dad was in hospital in an iron lung – her Mum nursed him. They married against family members’ wishes, and separated 12 years later.

Caro’s career has been illustrious – working as a band booker, in publishing houses, as the director of four world class writers festivals and and most recently at the Melbourne museum. Though it hasn’t been without struggle – she experienced sexual harassment as a cafe worker, workplace bullying at an international writers festival, and loneliness, and perhaps regret, as a result of leaving her son in Australia while she worked overseas. She also glossed over the three previous books she‘s written, a detail I felt was rushed.

I write this piece as a disabled woman, a writer, a writer passionate about disability inclusion and representation in literature, and also an advocate for accessibility in bookstores, publishing houses, and writers festivals.

Caro and my experiences and acceptance of disability are very different. I was born with my disability (a rare, severe skin condition), although didn’t identify as disabled until my mid 20s. It took a lot of practice to get proud, especially because so many people believe I can’t possibly be proud looking like I do, and tell me I’m unworthy of love, happiness and equality – through overt discrimination, exclusion and subtle microaggressions. I imagine this was the same for Richard, and indeed Caro.

I am passionate about increased positive representation of disability in literature and media. Tragic stories around disability are the default, and I strive to change that in my work.I think it’s excellent that a large mainstream publisher published a disability memoir and biography, and that it’s been shortlisted for The Stella Prize. I hope that Diving Into Glass paves the way for many other types of disability stories to be published and win awards.

When she was diagnosed with MS, Caro experienced anger and shame. In a brief written interview between Caro and I (below), she confirmed something she wrote in the book.

“Dad always told us that he was our fall guy, so we could live life safe in the knowledge nothing would physically harm us, so imagine my surprise when a neurologist told me I should move into a house with no steps!”

But that’s not how the life lottery works. Ed Roberts, known as the father of the independent living movement, and who was also in an iron lung like her father was right when he said,

“There are only two types of people in this world. The disabled and the yet to be disabled.”

At a recent feminist writers panel event that I was able to attend unexpectedly, I heard Caro say that she has a lot to be thankful for since her MS diagnosis. She said,

“I’m not going to write that book, because that would be boring. No one wants to read that happy story”.

But many of us want to read stories of hope.

Not in an inspiration porn way, as Stella Young talked about, but in a way that shows us what’s possible. The story of disability as a tragedy is hard to escape, and it shapes how we are all seen, keeping expectations of disabled people low.

(That night, Caro also told host Jamila Rizvi and the packed audience that she didn’t see Diving Into Glass as a disability memoir, nor only for a disabled audience – “it’s for everybody”, she said.)

Like Caro, Richard Llewellyn also had an incredible career. He was clever and adaptable, and overcame immense discrimination. Before he contracted polio and then became disabled, he was sailor. And as a disabled man, he worked hard to provide for his family – making table mats and coasters, buying a mixed business store and an art gallery with his first wife, and then working in the Public Service – at first as a volunteer to prove himself, and then with pay but not equal rights as non disabled people, as a disability advisor to South Australian Premier John Bannon, and as a fierce disability activist. Since his death, a fund for Deaf and disabled artists has been established in his name.

While Caro wrote at length about her father’s disability and the barriers he faced – including unbelievable discrimination, I felt she also skimmed over his major achievements.

Caro wrote

“Future generations of Australians have my father, and Becky in the wings making his work possible, to thank for for accessible public buildings, taxis that can transport people in wheelchairs, footpaths with ramps and accessible toilets. His tireless campaigning made it impossible not to hire someone with a disability if they were the best candidate for the job”.

I only wish his achievements – personally, and the way he made Australia and the world a better place could have been written about without being surrounded so much shame and stigma from his daughter. Becky Llewellyn, his second wife, wrote a 12 page detailed, compassionate and assertive submission to the Productivity Commission in 2011, outlining his personal achievements, career and the many improvements he made for disabled people.

From Becky’s submission:

“Richard also fathered 4 children, travelled interstate and overseas, invented key disability equipment and challenged conventional welfare blocks in Adelaide, then nationally, to listen to the voices of people with disabilities. He believed in self‐interest but also in creating a society without barriers so that people could make choices to participate as they wished. He was an advocate for raised expectations of people with disabilities but with structural and systemic supports to enable this citizenship to flourish.

He began his wider role of encouraging more people to be advocates by mobilizing people in the late 1970s in a Club for Physically Handicapped. It met alternately at the Home for Incurables or Regency Park Centre for Crippled Children. People came together to learn how to be more active, participate and run committees. In the process, this Club started a movement that created many national leaders from SA in this field. Individuals count and it is in all of our interests that people with disabilities, not those of us who work with, live with and love them, push the agendas forward. Disability led initiatives, which tap the principle of self‐interest, are the most efficient market mechanism to ensure progress happens. People who are living this experience have the passion, commitment, black humour and crap‐detecting instincts to give over and above the normal because they are stakeholders in a larger vision of progress.“

In my work, I’ve been vocal about how people write about disability – especially the power imbalance that comes with non disabled storytellers. I am passionate about disabled people writing on disability – and so I’m grateful for this very writing opportunity, and also appreciative of Astrid Edwards’ review of Diving Into Glass (Astrid also has MS). And I also constantly question whose story is it to tell? The themes of people’s stories about disability – especially of a family member – are often burden, grief and shame. I believe this narrative not only impacts on the disabled person being written about, but the disability community as a whole. It’s hard to find pride when people show little respect and value for you.

But it becomes tricky when a disabled person writes about their own ableism towards others. On one hand, Caro’s feelings of abandonment and the shame she felt around her father’s disability are valid parts of her story. On the other hand, her father is dead – with no right of reply. While she writes about the discrimination and humiliation he faces by the public, his workplace and also family, she also writes about the shame and resentment she harboured towards her father, often very ableist.

While Caro has acquired her disability just over a decade ago, and the feelings she had towards her father were when she was much younger, she still wrote about her Dad with an ableist and shameful lens. This goes to show even disabled people aren’t always respectful when writing disability.

Caro wrote a lot about the shame and resentment she harboured for her father and his disability (which she also talked about on ABC Conversations) – that she was embarrassed when he came to parent teacher nights, she almost ridiculed him for claiming the success of growing tomatoes in a garden – even though he didn’t do any of the physical work, that she believed he tricked her mother into a relationship for his own freedom. She also used the word “cripple“, and laughed at the memory of her young son giving Richard the dehumanising nickname of “Chair”, stating “My father was his wheelchair.”

There was one story in the book that horrified me, especially in light of the current Disability Royal Commission. She wrote,

“Despite all the proof to the contrary – the wheelchair, the lifting device by the bed, despite not once being picked up by my father, I didn’t really believe he couldn’t walk, I thought that he was just being lazy, that he simply liked all the attention of us doing everything for him… I was eight when I came to the firm conclusion that my father wasn’t a cripple, he was a fake”. “I decided the only thing to be done was to set my father on fire.”

Caro believed setting her Dad on fire would make him walk, because she had heard a story about a man in a wheelchair who had been miraculously cured after his house caught on fire.

She told Richard her plan, and wrote that Richard was convinced she would proceed with this idea, so he asked Becky to hide the matches.

“Meanwhile I searched for matches, dreaming of roaring heat so hot my father would have no choice but that my father would walk from that damn chair.” , she continued.

She read this passage out at Byron Writers Festival, when we both spoke at a panel about disability memoir .She described it as “a strange way of me showing my love for my father”, and the audience laughed, awkwardly. I also laughed awkwardly before reading a piece out about how I stopped apologising about my own disability, surprised at what I’d just heard.

In my interview, I asked Caro how she is involved in the disability rights movement – given her Dad’s work. She told me,

“I’ve lived with disability all my life – first my father’s; now my own. I guess you could say I have been championing disability rights since the day I was born.”

I didn’t get that impression from Diving Into Glass. Only a few times did she write about her regret over how she viewed her father’s disability, and at times, she was very othering towards disabled people, and showed a lot of internalised ableism that I hope she works through.

I was challenged by reading this book and in writing this piece. It surprised me that a book like this would be shortlisted for a prestigious award, especially in a time when own voices are prioritised. Yes, Caro told her own story, but in doing so, she cast her father as a burden, manipulative and unable. Disabled does not mean unable, especially with the right supports and love around disabled people. (I acknowledge that many of the barriers Richard faced were due to being in a different era, where disabled people did not have access to equal rights and adequate support.)

However, I am grateful that I learnt so much about Richard Llewellyn AM through reading this book. I went on to research his work further.

When I encounter ableism, I often return to the work of proud disabled people, to remind me that I am worthy – that all disabled people are. The late writer, disability activist and comedian Stella Young had a tattoo saying “You get proud by practicing” on her arm – the title of Laura Hershey’s famous poem on disability pride.

“Remember, you weren’t the one

Who made you ashamed,

But you are the one

Who can make you proud.

Just practice,

Practice until you get proud, and once you are proud,

Keep practicing so you won’t forget.

You get proud

By practicing.”

I hope Caro can read this poem, and the work of other disabled people, and become proud too.

Author Q&A

I did a written interview with Caro as part of the research for this piece – here’s our Q&A. My questions are in bold and Caro’s answers are below.

1. Diving into Glass is your fourth book. It’s your most personal – a memoir and biography of your father. How did it feel to write about such personal stories?

Caro: “It was very challenging to write such a personal story – hence the time (15+ years) to write the book. I had to process and do a lot of self-reflection in order to make sense of what was happening to me and it was very challenging for me to speak my truth, tell my story!”

2. I understand that even though you grew up with a disabled Dad, you struggled to come to terms with your MS, describing your Dad as your “fall guy” – you assumed he took the hit of tragedy for your family. (Note – I don’t believe disability is a tragedy, or means for a tragic life.) Was writing this memoir, and talking with other disabled writers in events (like the panel with Jessica White and I, and also with Jamila Rizvi) helpful for you in processing your grief of acquiring MS?

Caro: “Yes, absolutely. Dad always told us that he was our fall guy, so we could live life safe in the knowledge nothing would physically harm us, so imagine my surprise when a neurologist told me I should move into a house with no steps! Writing the book made me understand my life experiences better and I was able to heft off a lot of shame, which has been very liberating. And, yes, talking with you and Jessica and Jamila has been hugely affirming – to be with such amazing women, living such amazing and inspiring lives has been a great privilege.”

3. Has writing this book (and seeing the reactions to it) changed your views of disability as a tragedy?

Caro: “You are so wonderfully right that disability doesn’t have to mean that you lead a tragic life. Life with a disability might mean it’s different from other people’s daily experiences, but it doesn’t necessarily have to mean it’s sad or helpless or tragic – it’s different. I don’t want to sugar-coat it, life with disability presents challenges. Sadly, the world is simply not yet set up for diversity, but we’re all working on it and it’s getting better all the time. But I think the thing to really celebrate and acknowledge is that there are all sorts of unexpected joys and discoveries. So often when people are walking with me (which means walking slowly) they say, “Wow, this is so nice. I’m forever rushing everywhere. It feels good to slow down. I feel like I can breathe.”

4. One of the biggest privileges I’ve found with writing disability related memoir has been other disabled people writing to share their stories with me – especially how my work has helped them find self-worth and the courage to disclose their disability (to others, and even to themselves). Have you found this too? How do you hold space for their stories, and yours?

Caro: “You’re so right that it’s a great honour and privilege to have people share their personal stories and experiences having read the book or heard my story. It’s the greatest joy to learn that someone has gained insight or hope or learned something that makes their journey easier than mine.”

5. I personally became to identify as disabled when I met and read the work of other disabled people – even though I’ve had a life-long severe skin condition. I realised we experience very similar barriers and discrimination, even though we have different impairments. I cherish disabled writers’ work – it makes me feel less alone – and am so excited to connect with many disabled writers in person and online. What other disabled writers have inspired you?

Caro: ”It’s so wonderful to hear that reading helped you in your journey and enabled you to make connections with others. Seeing the lives of others through a different lens and identifying with them even when the specific details might be different is one of the very best and most important outcomes of literature and reading. Brava to that!”

6. How have you benefited from your Dad’s work in the disability rights movement?

Caro: “People with disabilities are not the only people who benefit from my father’s work – ramps and easy access are also good for parents with prams, the elderly, the injured…. Buildings designed well with access in mind are inclusive to all people and that’s a thing of beauty.“

7. How are you involved in the disability rights movement – through writing, your wider work and personal life?

Caro: “I’ve lived with disability all my life – first my father’s; now my own. I guess you could say I have been championing disability rights since the day I was born.”

8. I think it’s excellent that a large mainstream publisher published a disability memoir, and that it’s been shortlisted for The Stella Prize – well done! What adviceand encouragement do you have for other disabled and chronically ill writers, following the critical acclaim of your book?

“Tell you story as honestly as possible.”

9. You have worked in literary festivals and also publishing, and now have this book out – which touches on your disability, and your Dad’s too. Are you still seeing barriers to the literary industry (festivals and publishing and book events), and what changes have you seen/have you helped make?

Caro: “I have seen terrible oversights at literary events. Once I watched on heartbroken as Toni Morrison had to receive a big prize from a human rights organization off stage where no one could see her, because no-one had thought to organize a ramp for her wheelchair to get on to the stage. There is a lot of training to be done in the industry to make sure it becomes second nature to allow access. Strange thing is, it benefits everyone not just the person with the disability.”

10. What are you plans for future writing?

Caro: “I’m so excited to be almost finished a novel, which I started last year. I figure the memoir took 15-years, so this can be a bit faster! It’s about a woman who returns home after living in New York for many years and wonders where she belongs. Sound familiar….?!”

Caro Llewellyn has created Together Remotely – a virtual writers festival – as a response to COVID-19. Find out more information about Together Remotely here.

December 26, 2020

Book review: Beauty – Bri Lee

Content warning: eating disorder, self harm and fat phobia

Disclaimer: I know Bri Lee -I have socialised with her at writers festivals and have worked with her three times – in the capacity of writing for her magazine and speaking on panels with her. I have sat on this review for 10 months, as I know how important it is to support writing colleagues. But my work as an appearance activist, and also living with a facial difference and skin condition meant I didn’t want to stay silent on the messages this book. I also acknowledge my thin privilege and I’ve never experienced an eating disorder.

Beauty is an academic research project made accessible through writing it in a memoir style. It’s about Bri’s experience with an eating disorder and self harm, particularly after the release of Eggshell Skull. It was written as part of her Masters of Philosophy. It is well researched and the references are mainly literary rather than academic, and it’s very Introspective about her desire to achieve great things, and achieve her ideal weight.

While it is her own experience, the level of detail about her eating disorder and self harm is graphic – which I believe might not conform to eating disorder and mental health media guidelines. I am surprised to see the absence of eating disorder and mental health helplines in the book. These are important given how influential Bri is to young people.

Beauty also demonstrated fat-phobia – of herself and of others. Two particular sections stood out to me in relation to her fat phobia.

The first was when she asked her boyfriend ”Would you still love me even if I was really fat?”. He said yes. “This couldn’t be good”, she wrote.

I was shocked. Does she believe “really fat” people aren’t deserving of love? Does she?

Appearance and size doesn’t make people unloveable.

I can’t help wonder if this is similar to asking if she became disabled, would she still be loveable?

The other part was when “in the middle of [her] starvation routine], [she] was in a restaurant and a very large woman sat down at a table near [her]. Bri wrote about how beautifully dressed and groomed” this woman was, and observed her eating habits – dumplings and champagne. She wrote “from this information I determined she enjoyed life and was accustomed to doing precisely as she pleases. I liked that and I warmed to her immediately, but I also feared that if I too did exactly what I wanted I would end up big like her.”

She went on to grapple with the idea that by thinking that, she must dislike the woman, and believed if she was fat, she would respect herself less.

I understand this book contains her own experiences of an eating disorder, but it also sheds a light on privilege and her feelings about fat people. As well as writing two successful books, contributing to sexual abuse law reform in Queensland, appearing in the media and being a (now non practicing lawyer, Bri has been a Sportsgirl model, and collaborated with other fashion brands. Shes spoken at prominent events, and featured in fashion magazines She’s very accomplished.

While her beauty and size privilege is not acknowledged in this book, she does acknowledge this privilege – and also education and class privilege in her talks – including one I participated in.

Bri has been afforded many privileges in the media and in fashion (as have I to a lesser extent). This Masters thesis is also now a popular literary publication. I couldn’t help think though, as Bri was starving her body to be in a glossy magazine, and fearful of how she might be portrayed, myself and many others are constantly making noise for more appearance diverse people to be included in such magazines. I know so many people who would love similar media and fashion opportunities.

Beauty contained references to many publications and thought leaders in media and the beauty sphere, but the research was not intersectional. There was mention of talking to a woman of colour about her beauty standards. (Bri admits she was “deaf to this” – which is an ableist term).

I was curious about why appearance diversity wasn’t mentioned, especially since those of us with diverse appearances like facial differences, skin conditions and disability experience a high level of discrimination and also struggle with self esteem.

I know Bri’s talent as a writer and speaker – and also her physical appearance (as she writes) – will ensure she will have a stellar career. I hope her future research and exposure to others’ experience makes her work more intersectional and inclusive. And I hope Bri makes peace with her body soon – it has done so many great things, and will continue to do many more.

Beauty is published by Allen and Unwin.

Image: a book cover. It’s grey with an artist I’d depiction of a face. The face has different coloured brush strokes. In the bottom right there is text. “Beauty” and Bri Lee” are written in white and black text – the title is in lower case and her name is in upper case. Below her name is “The acclaimed author of Eggshell Skull” in black text.

Image: a book cover. It’s grey with an artist I’d depiction of a face. The face has different coloured brush strokes. In the bottom right there is text. “Beauty” and Bri Lee” are written in white and black text – the title is in lower case and her name is in upper case. Below her name is “The acclaimed author of Eggshell Skull” in black text.Find support:

Lifeline: 131114

Kid’s Helpline: 1800 55 1800

Butterfly Foundation: 1800 33 4673

December 17, 2020

It’s still ableism if you have proximity to disabled people

So many people tell me they work with disabled people, or they’re a parent of a disabled child, or they know a disabled person – and that gives them a free pass to be ableist. They often say “I know a disabled person and they don’t have a problem with the R word”, or justify sheltered workshops paying well below the minimum wage, or don’t even consider accessibility when planning events or writing content, or never including actually disabled voices – only listening to and amplifying people who have proximity to disability .

Whether it’s ableist slurs, or discriminatory behaviour, or justifying ableism – it’s not ok to be ableist if you’ve got proximity to a disabled person.

It’s also still ableism if you’re disabled and are *also* being ableist – like saying “I’m not disabled like them”, or using slurs, or punching down and making fun of someone with a different impairment to you.

I love this meme from @strengthcenteredspeech on Instagram – follow and support them.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Strength-Centered Speech (@strengthcenteredspeech)

Image description – via @strengthcenteredspeech: “Cream background with colorful shapes (pink, tan, green) along the edges.

Text: it’s still Ableism if you…

Study or teach about disabilities but ignore or speak over disabled people in real life.

Have family or friends with a disability but refuse to accept their wishes or preferences.

Make art about disabled people but don’t include disabled people in the process.

Hire disabled people but pay them less or refuse to accommodate them.

Call you setting a safe space but disregard accessibility.

Call yourself an ally but only advocate when it’s convenient.”

December 14, 2020

Spaghetti strap dress

Image: selfie of a woman with a red face and shoulder length curly hair, wearing a green, yellow and pink leopard print strappy dress over a pink tee. Her necklace is a large green bottle of green champagne, tipped upside down, spilling gelder champagne and streamers. She’s smiling near a white door.

Image: selfie of a woman with a red face and shoulder length curly hair, wearing a green, yellow and pink leopard print strappy dress over a pink tee. Her necklace is a large green bottle of green champagne, tipped upside down, spilling gelder champagne and streamers. She’s smiling near a white door.If you think you shouldn’t wear something because your face and body doesn’t conform to patriarchal beauty standards – put those thoughts out of your mind.

There is always time to start dressing how you’ve always wanted to – in clothing that makes you happy.

You deserve to be seen. You deserve to take up space. You deserve to spend your money how you like, with whatever budget you have. You deserve to get joy from fabulous clothes. You deserve to wear bright colours (or blacks or more subdued colours if that’s your thing). You deserve to wear amazing clothes – and to be seen – at any age. Your skin and your body deserves to be seen – with skin conditions, scars, stretch marks, pigmentation, wobbly bits – or you can cover up if it makes YOU more comfortable (which is what I do). Don’t let others make you feel like you should hide away.

You shouldn’t need my permission to wear loud prints, fun clothes like you wore as a kid, shoes that aren’t black or brown, and sequins on a Thursday! Just do it. I promise you’ll feel amazing! And you might even attract compliments about your outfit – so you should!

In the 90s, these strappy slip dresses were in. I read Dolly and shopped at The Miss Shop. I think I had a navy one with small white print. But I’d never wear it, as I would be self conscious of showing off my red, scaly skin, and I’d also be cold, or get sunburnt in the summer. But then I wouldn’t wear it over a top like I have done here because no one else was, and I didn’t want to stand out anymore than I already did.

But now – I’m wearing the dress over a long sleeved pink top, (and green leggings) because it makes me happy. And that’s fucking fabulous.

Don’t wait to wear something fun. Wear it now.

December 5, 2020

A falling out of love letter to Gorman

I posted this on Instagram today.

Dear Gorman clothing,

I’ve been a loyal, frequent customer of yours for five years. Your clothes have changed my style – they make me very happy. I wore my favourite print of yours on my book cover.

But I’ve fallen out of love.

I’ve bought far fewer Gorman items – party due to the pandemic changing how I work, but also because you have disappointed me.

I bought this dress a few weeks ago, & I did buy another today. I can’t see myself buying anything further until you change your ways.

You’re mot size inclusive. Yes you go from a size 4 to a size 16 (not all of your clothing though), but you rarely show anyone plus sized wearing your clothes. Your sizing is inconsistent.

You appropriate designs from artists – the latest being the very talented Aretha Brown.

When you do pay artists, your payment is very low.

Your pricing is inconsistent – and you take us on a rollercoaster ride with sales. Up and down and up and down – all in a week.

Disabled people make up almost 20 percent of the Australian population – that is, we make up almost 20 percent of the Australian economy.

Yet you don’t reflect the disabled population in your advertising or in your stores.

Many of your stores are not wheelchair accessible – no wheelchair accessible entrances, and steps within the stores. I am talking about those south of the Yarra – I wonder if there are others? Your online content is not accessible either.

You’ve never featured a visibly disabled model – but you’ve featured a dog with a mobility aid wearing a dog coat!

And you totally ignored International Day of People with Disability on 3 December. What a missed opportunity.

I know so many people have bought your clothes because I wear them & post them. But you don’t show the same love. I was lucky to be featured once in a group photo on your Instagram feed, but you’ve never liked my posts nor shared my stories. Never. I wear your clothes often, posting them to a significant following – as do other disabled people.

The best thing to happen from being a Gorman customer has been the friendships made – a group of wonderful women who share a love of rainbow clothes.

This post is me holding me accountable. I will continue to wear the Gorman I have, but I will try to sell some. I will not be tagging them on my social media posts when I do wear them. I will support smaller, ethical brands who *are* committed are* committed to diversity, inclusion and access.

I also posted this reply to a comment on a Gorman Instagram post, in response to someone saying shame on me for asking why Gorman overlooked Disability Day on Thursday? – don’t I know how much they’ve done for charity?

My reply: yes I have been to many Gorman events, and I’ve bought many items. But I call on them to do better. I’ve felt this for a while. I am not sorry that calling for better accessibility and inclusion, and for them to treat artists (and factory workers) better disappoints you. My stance on access and inclusion isn’t a new stance for me – I’m just calling for one of my favourite brands to do better.

I also want to add, I’m not worried about likes or shares or follows but I wanted to make the point of who they select to be seen. Because it’s not women like me.

And apart from regular sales, and gift bags from their launch events (one time I won a voucher) I’ve never received payment or free items. I’ve paid for it all.

December 1, 2020

IsoCreate – cubbie mako

This is a project supported by The City of Melbourne Covid Quick Response Grant. I have interviewed disabled and Deaf artists about how their creative practice has been impacted by Covid-19.

Below are words from cubbie mako – a writer and founding member of Disabled QBIPOC Collective. cubbie’s pronouns are they/them, they are hard of hearing and #ActuallyAutistic.

[image error]Image: a photo of a person’s head and shoulders. They have brown skin. Their face is barely visible because bright shaggy, red hair with dark highlights frames their head. They are a dark brick wall.

cubbie mako – writer

cubbie began writing fanfiction almost a decade ago – after spending many months in an exceptionally clean environment – when they were in self-isolation with then two-year-old child.

By 2013, cubbie attended art classes at Footscray Community Art Centre for art therapy, where cubbie’s artwork progressed to creating digital fanart.

Wanting to improve their storytelling, cubbie found themself writing non-fiction under the mentorship of Lee Kofman.

cubbie didn’t know they were Hard-of-Hearing until they joined a writing group. When cubbie couldn’t hear them across the table, in very echo-y room with lots of ambient noise, cubbie would ask to repeat what they said, and able-bodied BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) took offense.

Unfortunately, many BIPOC and QBIPOC hide their disabilities and their gender for fear of backlash or abuse from friends or even their families.

Many migrant communities silence and exclude those who do not follow the (mythical) ‘model minority’. The abuse towards disabled QBIPOC within their families and communities could be twice more difficult due to their invisible disability—which may not have a direct translation into the BIPOC language—and their queerness, because of strict mainly patriarchal structures within these communities.

Is it because of too many intersections the normal, able-bodied people to understand and empathise?

cubbie eventually wrote their experience into a poem titled ‘In the Air’, published via The Suburban Review Issue 12. This ekphrastic poem, in collaboration with media artist MJ Flamiano, who created a video of Deaf Poet Walter Kadiki performing cubbie’s poem.

This collaborative, ekphrastic work between cubbie and MJ was eventually shortlisted in the Queensland Literary Awards.

There is a recently published essay about how cubbie experienced COVID19 in the early weeks of March 2020.

Having been formally diagnosed with Autism a week before COVID19 lockdown began, cubbie had a difficult time dealing with a new diagnosis and the logistical problems faced when in quarantine with their two kids.

Finding food to feed a family of four with an already tight budget and searching for liquid hand sanitisers online to clean accessibility equipment of their disabled child, and assisting in homelearning at the start of school term 2 (mid-April 2020) proved to be overwhelming and challenging for cubbie.

And then, they remembered what they used to do during their first isolation a decade ago: colouring! Together with their child, home learning during the pandemic isolation as a Year 4 student, enrolled in a mainstream public primary school, they would play and colour together.

[image error]Image: a colouring book, open with coloured textas in a container on the table. A mandala is brightly coloured.

[image error]Image: a colouring book, open with coloured textas are lying on the table. A mandala is brightly coloured.

Even before COVID19, cubbie had no capacity to attend or travel to literary events in Melbourne. As a full-time carer and late-diagnosis autistic, cubbie found crowds and noise overwhelming.

When their self-isolation started, Creatives of Colour organised a Zoom meeting for the Disabled QBIPOC Collective to meet online for the first time. cubbie never heard of Zoom before the pandemic, but towards middle of April to May 2020, things started changing. After receiving the one-off $750 stimulus from the government, things became easier and less stressful, and routines emerged. cubbie was even able to attend a webinar on speculative fiction via Writers Victoria.

And then cubbie attended a Zoom meeting, hosted by Creatives of Colour, where the organisers included live captions.

It was an information session on Covid-19 opportunities facilitated by Auspicious Arts Projects. cubbie was not aware such opportunities existed for artists.

The next day, cubbie applied for a couple of grants. Cubbie never applied for a grant before. But somehow, the organisations made the grants application process simpler and easier because of the urgency of the situation in a pandemic.

And looks like the people in positions of privilege and power have listened to what Disabled artists have been asking since their event at The Wheeler Centre: include the Disabled in the mainstream narrative. Because in the Creative Victoria’s grant called ‘The Sustaining Creative Workers initiative’, the arts grants organisation added a stream for Deaf/Disabled artists living in Victoria.

When we do go out, like, once a week, to replenish medication, or buy food, we wear masks, and sometimes gloves, too. We bring little bottles of hand sanitisers with us. It is a struggle to simply step out of the house.

Also, cubbie observed that the only way Disabled artists get paid gigs during a pandemic are through invitations by white allies who are in positions of privilege and power. Otherwise, our pitches get rejected by able-bodied, white, mainstream narrative.

Finally, because we are in isolation, with libraries closed, we mainly depended on reading via libraries’ digital apps, downloading free ebooks and audiobooks. But where are the Australian BIPOC QBIPOC authors’ books in digital editions? #WeNeedDiverseBooks in digital platforms and libraries e-collections. The trifecta of having a print edition, ebook, and audiobook means accessibility and inclusion for the Disabled, including myself, who needs a print edition to read while listening to the audiobook, and an ebook makes reading easier at night, reading larger fonts in a digital device.

Surprisingly, the Disabled QBIPOC Collective have received multiple invitations to write, to be included in an international panel, to be showcased in Zoom events centring either QBIPOC artists or disabled artists.

The paid gigs gave us the capacity to buy food for our families, for ourselves, especially when we were excluded in government benefits like Jobseeker or Jobkeeper. The petition #RaiseTheDSP wasn’t supported anymore once the other COVID19 benefits were approved.

My top tips to artists and arts organisations for making art digitally accessible:

To literary arts publishing gatekeepers: #WeNeedDiverseBooks in Australia, which means Australian BIPOC and QBIPOC authors’ books must include #ebook #audiobook because #Accessibility and #InclusionMatters. Moreso now with NDIS continues to roll out across Victoria;

For online events programmers: from the very start – grant application or budget allocations, please include budget for Auslan interpreters, live captions, and audio descriptions;

For podcasters please include transcriptions in your podcast, in your grant budget allocation.

In a post-COVID19 world, make accessibility the norm and not an afterthought;

For someone who does not drive a vehicle but prefers to cycle using a three-wheeled cargo-bike or trike, that university courses, the academia and those who hold power and privilege in education to rethink their design principles and make the basic principles include accessibility. (i.e. design, architecture, and (civil) engineering schools’ degrees);

That schools be more inclusive. No one is left behind in a pandemic or in a disaster situation. Include the Disabled in disaster planning strategies. All means all.

As a writer, cubbie wishes webinars, Zoom still be included in face-to-face workshops for audiences who have no capacity to attend events on location.

cubbie’s bio:

CB Mako (cubbie) is a non-fiction, fiction, and fan-fiction writer. Winner of the Grace Marion Wilson Emerging Writers Competition, shortlisted for the Overland Fair Australia Prize, Queensland Literary Awards-QUT Digital Literature; and longlisted for the inaugural Liminal Fiction Prize, cubbie has been published in The Suburban Review, Mascara Literary Review, The Victorian Writer, Peril Magazine, Djed Press, Overland, Liminal Fiction Prize Anthology (arriving in 202X), and Growing Up Disabled in Australia (via Black Inc Books, February 2021). cubbie is on Twitter and Instagram.

This project has been curated by Carly Findlay and supported by the City of Melbourne Covid grants.

IsoCreate – Larissa MacFarlane

This is a project supported by The City of Melbourne Covid Quick Response Grant. I have interviewed disabled and Deaf artists about how their creative practice has been impacted by Covid-19.

Larissa MacFarlane’s is a visual artist, specialising jin lino cuts and paste ups. words are below. Larissa’s pronouns are she/her, and she identifies as disabled.

[image error]Image: a photo of a woman doing a handstand on a wall. She has fair skin. She is wearing brightly coloured layered clothes ans has long dreadlocks and a red tartan peak cap on her head. Next to her is a colourful cane. On the wall is a black and white paste up of the same woman doing a handstand.

“I am a visual artist and disability activist. I am based in Naarm and live and work on the lands of the Kulin Nation. My visual art encompasses printmaking, especially linocuts, street art, such as my handstand paste up girls, and community art with my disabled community. I also work in the Self Advocacy movement with my peers with cognitive disability (Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) and Intellectual disability), and the Consumer/Survivor movement of peers with lived experience of mental health/trauma issues.

I became an artist after experiencing a brain injury 21 years ago. I literally woke up and the world looked different. I was also different so there was a long period of learning/practicing new skills to support this new me, as well as learning/practicing new skills around my new passion of visual art.

Much of my art work has been and continues to be informed by my own and others experiences and challenges of living with disability. My work is particularly influenced by my passion for Disability Justice and enabling Disabled led, safe and creative peer spaces. But I see many barriers for people being able to identify with disability, which limits our ability to access strength and knowledge from each other, and undermines our ability to access our everyday rights. Internalised ableism, a big issue for myself and so common for so many disabled people, has been a particular focus. In recent times, this focus has led to my artwork about Disability Pride, which has included leading several collaborative and solo Disability Pride murals since 2017.

Images a series of Larissa, who is a woman with fair skin. She is wearing brightly coloured layered clothes ans has long dreadlocks and a red tartan peak cap on her head. She is making art in every photo.

[image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error]

I make art because I need to. I also do it because it usually makes me feel better and I learn more about myself and the world. I often persist in making art because it gives me an identity, a community and life meaning. But I also make art, because I want to communicate and because I believe in the power of art to make change and make all of our lives richer and more just.

I have faced many barriers, and so many of them have seemed senseless. I started making art in disability services. But getting access to materials and skills/knowledge was really hard. Art in disability services often seemed to be a room to put people in, rather than something to do of value. And more often than not, ‘Art’ was (and often still is) a very poor watered-down version of art therapy.

Accessing mainstream art education was also a real battle. I finally gained a Diploma of visual art (it took 10 years!), but I had to give up on my tertiary education mid-way.

Much networking in visual arts happens at openings, which for the most part is often inaccessible to me. (These are often very busy, loud, bright, with flashing lights and very little seating, up many stairs away from accessible PT). Fortunately, I have my own pretty good independent networking skills to make up for this.

The contemporary art world is also quite elitist and mostly supports those who engage in tertiary education and particular forms of art making. I have found that Disability Arts, as well work by Deaf/disabled artists, and also Community Art, is not highly valued.

I want to add that I have also had lots of opportunities, but I want to emphasise that I recognise that many of these have come from the hard work of so many people around me and before me, who have worked to forge pathways, as well as create opportunities for others. I am literally standing on the shoulders of others who have come before me. Sometimes, these opportunities can look like good luck or my own hard work, but they are also due to the privilege and access that I have, especially as a white, cis gendered, verbal, mostly mobile and educated woman.

Covid has had a huge impact on my life, my health and thus on my arts practice and my creativity. Loss of many therapies, most especially my daily hydrotherapy, has dramatically decreased my physical and mental health and increased my experience of pain and fatigue. Trying to re-establish and renegotiate health care and disability support has been ridiculously hard. This has been made more difficult because whilst these are all service that operate within a medical model of disability, Covid seems to have exacerbated their medical and charity model structure. The accompanying increased ableism within these health services has been very difficult for me to negotiate. I am so much less able now to shut up and be passive, which has led to being effectively excluded from several disability and health services. This is discrimination, but I currently lack the energy, health or support to effectively deal with this. I know that I am not alone in this experience.

The increase in ableist attitudes, that seems to be permeating our culture, our health and support systems and the media, has ramped up my own internalised ableism, which has had an immeasurable impact on my confidence in my art practice. At times is has also led me to feel like Disability Pride is a luxury for less dramatic times. However, at the same time, we need Disability Pride more than ever, as so many of us fight to retain access to our supports and thus connected to society beyond our homes and/or institutions.

The sudden increase of the word ‘vulnerable’ to refer to disabled and other people, has personally been so disheartening. I spent several years and much energy pre-Covid, actively challenging its use. Disabled (and other) people are not inherently vulnerable. It is systems of discrimination and oppression that place us at risk.

The uncertainty about my future heath, especially whilst health services are still gatekeeping and creating access issues for me, has made it difficult for me to plan for future art projects. This has made applying for grants also difficult.

My disability and chronic illness puts me somewhere indeterminable between high and low Covid risk. This also creates extra uncertainty.

At the time of lockdown, I was part of 12 exhibitions that were either cancelled or rescheduled online. Of course, this has been disappointing. A couple of these were quite exciting as they were invitations to be part of some more mainstream exhibitions in well regarded gallery spaces. (Since strongly identifying as a disabled artist a few years ago, it was very disappointing to experience a sudden decline in invitations to exhibit in mainstream, contemporary and non disabled spaces. This weird exclusion was just starting to shift.) These opportunities also had some much-needed payment. I am hopeful that these will be rescheduled at some point.

I have certainly lost some income through Covid. However, I am also fortunate to have access to the Disability Support Pension DSP). (I am lucky to have applied many years ago, before the eligibility requirements became almost impossible to meet). But with the increased costs of health, medication, utilities and food delivery costs, things have certainly been uncertain. It has been disappointing to see the federal government exclude the DSP in the income support packages.

Also, of impact to me, has been the loss of studio space. At the time of covid I was undertaking a residency and had a lovely studio. This was cut short. I was also making plans to take up a new paid studio space, to continue the larger artworks that were in progress. These plans were also halted. Although, given my current health and finances it is possible that I would have needed to exit any paid studio that I set up. But I am still missing have a space to continue works in progress on days that I feel well enough.

I have also lost access to my regular weekly shared studio space. This is located in a disability service that has not communicated if/when they will reopen. This loss of access to a supported peer community has surprised me in its huge impact upon me.

It has been difficult and interesting to notice the ongoing pressure I have felt to apply for grants and make new exciting work. I also feel less connected to community and the wider world. I think this makes me less sure of myself, and questioning of my judgement about things.

Due to my ABI, I normally have to limit my use of screens. I also find many websites and much social media is problematic. (hint. Please stop using gifs or flashing or unnecessary moving parts in your websites and social media posts. These can trigger things like migraines and nausea, for those with photosensitivity, vestibular and neurological sensitivities). So, the move of everything online, has not been super welcomed by me. In terms of art events online, I have found it often too difficult to navigate to either find it or register to attend.

Sadly, I have found the bigger galleries are presenting exhibitions online using methods and software that are inaccessible for me. They trigger a lot of vestibular symptoms like nausea, dizziness and headaches. Some galleries have put more work on their websites as images, which I have enjoyed, although this is of course inferior to the real thing.

But there have been some highlights. And I have definitely seen art that is highly unlikely I would have seen if it was not online.

For example, I got to see disabled musician Liz Martin perform a live set. My ABI doesn’t process music and there is also an overlay of grief/loss, so I would never normally attend a gig. But for the first time in 20 years, I was able to attend a pub gig, by being able to have control over the sound levels and by limiting my exposure to 10 mins.

I also got to see disabled artist Leisa Prowd in an online burlesque performance, which is unlikely that I would have seen otherwise.

Images below: two photos from Subterranean Femmes show, 12 female street artists, Dirty Dozen Gallery. They feature black and white paste ups of Larissa doing handstands, as well as circular shapes,

[image error][image error]

I have had increased access to disabled artist voices from around the world, mostly US and UK, which has been great. One of these is the new Mad Covid blog, which comes from the UK and features many voices and artforms.

I was blown away by attending the Platform Live, an awesome line of Australian disabled artists, curated by Daniel Savage and Hanna Cormick.

I have also been able to attend a few professional arts workshops and artist talks, because they were online, as well as being free or low cost. This has been great as these are not normally available to me.

There are so many challenges for artists right now! But different challenges for different artists

I mostly have heard on mainstream and social media that visual artists are valuing this time. And I think if I was able to access the disability support and health care I need, then I too might be appreciating this time of isolation. However, this generalising of visual artists experience has led me to feeling very invisible and my experiences minimised. I have also found myself having to defend my position, after being told several times by (mostly non-disabled) friends and peers, that “I must be enjoying this time to make new work”. I wish!

Covid presents an enormous challenge for those many disabled artists who predominantly practice within community settings. Without being able to attend support programs or access support staff or communicate with peers in community settings, their art practice (and thus their wellbeing) has been severely curtailed. It is of great concern to me that a number of disability services that coordinate art programs have been very slow to set up digital online alternatives if at all. There also appears to be a failure by these same services to provide support to people who lack devices or internet connection or knowledge. As I said earlier, there seems to be a shift towards enforcing a much more medical charity model. The subsequent gate keeping of these disability service organisations is excluding not just current disabled artists, but those who are now finding themselves in health crises due to the effects of Covid and in need of support.

Since Covid has upped anxiety for everyone, people living with trauma and mental illness diagnoses, are really struggling now. I have noticed that this as well as non-person communication is making our communications harder.

I also think that the overall increase in ableism everywhere, has and continues to have a big and often unseen impact on disabled artists. It certainly has had on me. It has been very hard, particularly at the beginning of the Covid crisis, to be hearing messages through the media, about how some lives, such as the disabled and elderly are less Important. Such ableist and ageist attitudes, has certainly impacted my confidence.

For visual artists, a challenge is going to be finding new ways to exhibit and have openings, especially as in my experience, most of my income and sales are generated at openings.

As a printmaker, I also require access to shared printmaking studios. There are only a few of these in Melbourne and most are still closed to members.

For community artists, whose work often involves in person connection, there are some challenges ahead.

I haven’t had the health to be doing any street art. But my heart has been happy to see an increase of graffiti and tagging. I don’t normally enjoy seeing tagging, but at the moment I do as I like to see my streets alive!

The increase of access for homebound and chronically ill people has been amazing. I am also hopeful that this will lead to new art being presented by people we don’t often hear from.

I am also hopeful that Covid is leading to more disabled people getting skilled up to use the internet. People with intellectual disability as a group have generally had little access to the internet. However, some of my work colleagues at the Self Advocacy Resource Unit have been working extra hard to provide devices, internet data and skills for people with cognitive disability in self advocacy groups. However, this is only a few and there are many other groups of disabled people that are faring less well.

My tips for better accessibility are:

I highlighted before, the need to stop using gifs, and creating websites with unnecessary moving parts.

A really important step to making art accessible online for the long term, is to connect with and involve disabled people in your community and arts practice. If you are an organisation, you need to be employing disabled artists and making space on your boards. You could start by getting some training from places like Arts Access Victoria or Voice at the table (VATT).

I have many for the future. A world where the arts is recognised as integral and valuable in creating healthy and strong communities and economy! And where Disability Arts is recognised and given space.

I am hopeful that the bans on international travel, may mean more space for local artists.

I am hopeful that there is a real ongoing shift to recognising Disabled and diverse artists more.

I am hopeful that this may present opportunities for more collaborations, and an overall diversification of the arts. However, with more opportunities, Disabled and diverse artists from marginalised communities, will also need to be ever more vigilant against tokenism and find better ways to identify this and support each other.

Several months in, I am finally now finding the ability, the health and the space to make progress on some new artwork. It is so exciting and relieving!!!!!”

[image error]Image: the Disability Pride Mural wall in Footscray. On a brown wall, paste ups of art and people forming letters that spell out DISABILITY PRIDE. Photo by Anna Madden.

Read the essay about the Disability Pride Mural that Larissa co-wrote.

Larissa’s bio:

I am a Melbourne based artist and disability activist, working across wthe mediums of printmaking, artist books, street art and a community art practice. My work is inspired by the urban industrial landscapes of Melbourne’s West, as well as my experience of disability, to investigate ideas of belonging and place, healing and change, and ways that we can celebrate what we have here and now.

I began my visual art practice in my 30s after a brain injury rearranged my talents. I completed a Diploma in Visual Arts (CAE) in 2010, and have also undertaken some art studies at RMIT. I have been regularly exhibiting since 2006 and been a finalist in many and a winner of some art awards.

I have also become known for my street art practice that investigates my daily ritual of performing handstands, a key part of my disability self-management. In 2017, these handstand art works were exhibited at the Melbourne Arts Centre and the Warrnambool Art Gallery.

I have also led and collaborated on many community art projects, including working with Brain Injury Matters, the Self Advocacy Resource Unit, Arts Access Victoria, Arts Access Australia, Footscray Community Arts Centre and several local City Councils. I was a key member of Dangerous Deeds, a traveling multimedia exhibition (2015-2017), presenting a snapshot of the Victorian Disability Rights movement alongside self-advocacy workshops. In 2017, I staged two large collaborative paste-up murals in Footscray exploring Disability Pride. One of these was dramatically thrown into the media spotlight after it was destroyed a week later on International Day of Disabled People. This Disability Pride mural was reinstalled as part of the 2018 Melbourne Fringe Festival.

I am also currently vice president of Brain Injury Matters, Australia’s leading self advocacy ABI group, run by and for people with ABI.

I have had 12 local and International residencies, workshops and exhibitions cancelled due to COVID-19.

This project has been curated by Carly Findlay and supported by the City of Melbourne Covid grants.

IsoCreate – Jacci Pillar

This is a project supported by The City of Melbourne Covid Quick Response Grant. I have interviewed disabled and Deaf artists about how their creative practice has been impacted by Covid-19.

Jacci Pillar is a comedian and satirist. Their pronouns are They/Them. Jacci’s words are below.

[image error]Image: acci seated at their desk recording their community TV show, with costumes hanging behind them and a blonde wig on a stand next to them, dressed in a burgundy red velvet jacket and giving a thumbs up.

“I have been doing variety show style comedy and some stand up for four years now and started my comedy production business in 2017. It is an extension of my work in my representational anthropology career for over 15 years, the difference being I am putting myself on stage as the voice box through the medium of comedy. I do characters, skits, musical comedy with a dash of spoken word, monologues and stand up. My aim is to do more variety showcases on stage highlight diverse and marginalised voices and to launch a series of comedy documentaries made for TV or streaming on taboo social topics. The aim of these will be to shed light on community voices in a way that I take the heat for saying difficult things that need to be said. To be able to say things that others want to say but have safety concerns about saying, is a great use of my privilege as an artist. These productions aim to make pointed social commentary about the systems of injustice, punching upwards, so that my productions talk to the issues, the legislators and power brokers of privilege.

One of the barriers I face is sensory accessibility. As an autistic person I have sensory challenges that most venues and producers simply do not cater for. You know that old “lights, camera, action!” expression. For me it should be changed to “the right kind of lights, camera position and stimming action space!”. Part of this is genuinely that autistic performers are an exceedingly small percentage and people don’t know or understand our accessibility needs. Part of that is lack of knowledge, and part of it, sadly, is lack of will or discrimination. You get used to “sorry, we don’t have dimmable lights and we can’t accommodate your headset mic” as though these are ‘extra demands’ and not accessibility needs. I’ve been told I pace on stage too much and my rolling of fingers and flappy actions (autistic stims) need to be ‘toned down’. I channel my stims as part of my performance, they are ways I communicate through my body, not extra communication. As for needing a quiet space or even a quieter space before and after a venue, this is often near impossible. Venue accessibility is still very much about patrons and not performers, and I often experience a level of unconscious bias about this. I have found able bodied comedians often expect a lot of open mic stage time from me, as this is considered a comedy rite of passage. They do not acknowledge the accessibility issues and there is a “suck it up” mentality or a perception that you shouldn’t be doing comedy unless you slog through this able-bodied rite of passage. I have heard stories about disabled comedians (including those with mental health or chronic illnesses) being told they are unreliable or not supporting the local comedy scene when accessibility prevents them actively participating in the comedy scene. A byproduct of this, for me, is that I am limited to daytime events and sensory friendly venues (Hares and Hyenas is wonderful). I tend to align with comedians and venues who are consciously supportive of accessibility conversations without getting defensive. It is enormous emotional labor trying to explain these things, and I have been designing a sensory accessibility checklist for venues (and I use Melbourne Fringes guide for producers as well for education purposes).

I was injured in my day job in October 2019 and was unwell to begin with. COVID extended isolation for me and it’s been a real struggle, but I’ve ended up being quite productive. But what it has allowed is me to formulate and write grant applications and scripts. I have designed a community arts project called “The Deadline” which I am really excited about and which had great external support from national peak bodies and prominent diversity activist-artists. It will be a darkly humorous comparison of two family stories of stigma and taboo, one from 1888 and one from 2018 about the taboos of talking about mental health and addiction inside families. I am collecting stories from my own family and other people’s families that will be delivered anonymously, woven into the story lines.

The limited amount of grants available compared to the numbers of artists (both before and during COVID) with quality projects has meant I have not been successful in grants programs. The reality is, because I have an auto immune disease, that for the next two years my live performance ability will be very much limited. So, I have had to redesign “The Deadline” to be a hybrid blog, podcast and short film series and remove the community theatre aspect.

I’ve also taken the time to learn piano and have just written my first complete comedy song composition after ten lessons and lots of hours of practice. This feels great after relying on others with musical composition, I am super proud of the first song “The Presidents Lament”, mocking the Trump administration. I am also starting a research post grad degree in 2021 focusing on political satire and hoping to launch a new political satire character, Bronwin Budget-Slap by the end of this year. I managed to put my planned Melbourne International Comedy Festival into a pre-recorded format for Melbourne Fringe and it had a run of eight digital shows. In the middle of it all, I started my community TV show, “Talk-ist” which is produced by BentTV and airs on Channel 31.

Yes! The digitalisation of art, due to COVID-19, made things more accessible for you as an artist and audience member. But then I have lived in remote Australia for a great deal of my life before moving to Melbourne, so this is not unfamiliar for me. When you live somewhere with limited options you tend to be a consumer of online streaming anyway. I loved Schizy Inc. Mojo Film Festival online, this was fantastic. It was great to see a range of small films about mental health as an online audience member. In fact, I haven’t been able to physically go in previous years, so the online option was welcomed. I am looking forward to launching my website for “The Deadline” on the 1st February 2021. Digital Melbourne Fringe was awesome! All of it.

[image error]Image: Image capture from Jacci’s Melbourne Fringe show, Tardy: Ready and Disabled. Jacci (dressed in striping pants and a t-shirt with a comical periodic table symbol for Um, the element of confusion on it) is standing next to an enlarged childhood photo of them, with a graphic of their assistance dog that superimposed on the screen. Pepper’s image has a speech bubble that says “Pepper Paws: Stereotype alert!”.

I think our mental health is a primary concern and we are starting to talk about this. Not only do we normally get asked for work for nothing (the game of “exposure”), now there is a proliferation of online opportunities, also unpaid.

The plight of the arts has been largely overlooked by government, however, I think the arts industry has banded together in solidarity, so that is a positive. I also think our networking has improved in the process. We are reaching out to each other more and talking more about the challenges, and collaborations are being strengthened. It has also meant people have had time (even if begrudgingly) to consolidate their efforts and invested in equipment and innovation like they have not before.

My top 3 tips to artists and arts organisations for making art digitally accessible?

Closed captions. We need to do our utmost to ensure we can CC. I am seeing a lot more CC on products. I know there are number of challenges in this regard, particularly for live CC, but I think we need to lobby together to make CC regular and frequent practice and hold software manufacturers accountable.

Livestreaming. Investing in livestreaming is not only good for the COVID world, but also good for communities who need to be able to control light and sound or who live in remote localities. Let us open up our art to the world!

Ask. Ask what people need and think about the physical (ramps, physical space, CC, number of faces on a screen, transcript availability), the sensory (light, sound, speed of information) and the emotional (content warnings, ability to take a break like in relaxed performances).

In a post Covid-19 worldly I hope to see more art because we will have, across the world, realised the value of small arts productions. I sincerely hope we do not have a world getting tired of TV reruns that we get on top of COVID soon. However, I hope it leads to more diverse availability of art and a reinvestment as a culture into developing and emerging artists rather than depend on large scale productions. A sort of redistribution of artist wealth (symbolically and physically) as a result. I also hope the government will take mental health more seriously and commit more funds to it as a result.”

Jacci’s bio:

Autistic person. Disabled. Nonbinary neurodivergent truth bomber. My community TV show, “Talk-ist” has facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/TalkistTV. Like my Facebook page (www.facebook.com/jaccipillar) and follow me on Twitter (@Scribeandcomic) for news on my new project “The Deadline” hybrid arts project commencing February 2021. If you have an Irish-Australian background and want to talk to me, about family taboos and stigma about mental health and addiction, please email me on info@ginandtitters.com. As an anthropologist with a specialty in ethical representation, all information will be treated confidentially and will not be reproduced (anonymously if needed) without your express permission and written consent. The Deadline will be available from the 1st February at http://the-deadline.org/

This project has been curated by Carly Findlay and supported by the City of Melbourne Covid grant.

IsoCreate – Deafferent Theatre

This is a project supported by The City of Melbourne Covid Quick Response Grant. I have interviewed disabled and Deaf artists about how their creative practice has been impacted by Covid-19.

This is an interview with Jess Moody and Ilana Gelbert from Deafferent Theatre. Jess (she/her) is Deaf and an Auslan user; and Ilana (she/her) who is an Auslan user. In their own words: “Formed in 2016 by Jessica Moody and Ilana Charnelle Gelbart, Deafferent Theatre exists as a reaction to the audism that dominates our stages. Deafferent Theatre aims to re-imagine possibilities. We incorporate own bi-cultural methodologies using authentic representation, sign language, and a deaf aesthetic. We create new productions, and repopulate familiar stories with deaf presence. We champion courage, and collaboration.”

Episode one of Deafferent’s My Blood, with English captions, is also included below.