K.E. Lanning's Blog, page 3

January 18, 2020

Author K.E. Lanning Interview on PBS for The Melt Trilogy

Rose Martin of Write Around the Corner Interviews author K.E. Lanning. First aired on January 14, 2020 on Blue Ridge PBS

I hope you enjoy it, and please forward as you will! Link url: https://www.pbs.org/video/write-around-the-corner-k-e-lanning-x8easy/ Now I have to get back to finishing my next novel, Where the Sky Meets the Earth - my editor awaits!Best wishes for 2020 and welcome to a new decade!K.E. Lanning

October 10, 2019

Review of Author Margaret Atwood's "The Testaments"

Author Margaret Atwood (photo credit: Liam Sharp)

Master Puppeteer of Dystopian Theater

“Praise be!” It has been thirty-four years since the controversial, and even banned novel, The Handmaid’s Tale was published (1985), and on September 10, 2019, Margaret Atwood published its sequel, The Testaments. Her latest novel has already garnered critical praise and was named to the shortlist for the Booker Prize.

In The Testaments, her characters bear witness to the inevitable corruption of power in the totalitarian regime of Gilead. Extreme societies tend to end extremely, and as phrased succinctly by Gilead's Aunt Lydia: “In time like ours, there are only two directions: up or plummet.”

The Handmaid’s Tale introduced us to the country of Gilead—a nation based on strict theocracy, and though the interlude has been long, the final act of the play is The Testaments, in which we observe the increasingly corrupt machinations of a state, or perhaps a twisted royal court, which hasn’t as yet recognized its internal wounds, bleeding away the strength of its original “truths.”

Margaret Atwood, born in Ottawa, Canada in 1939, knew by the age of sixteen that writing would be her profession. Atwood graduated in 1961 with a Bachelor’s degree in English from Victoria College in the University of Toronto, and in 1962, received a Master’s Degree from Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA. In 1961, she won the E.J. Pratt Medal for her book of poems, Double Persephone. Atwood has also been a writer of feminist works such as The Edible Woman, published in 1969.

As a novelist, Atwood is a master puppeteer of dystopian theater, pulling the strings of character and scene on a macabre stage of her choosing. But her repertoire is not limited by time nor subject—she’s exquisitely adept at her craft—a frankly stunning career of writing—not only of speculative fiction like The Handmaid’s Tale and the MaddAddam Trilogy, but with novels such as Alias Grace, based on the true story of an infamous double murder in Canada during the nineteenth century.

Her latest novel, The Testaments, is told in an epistolary style via three points of view: Aunt Lydia, arguably the most powerful woman in Gilead; Agnes, a young coming-of-age woman in Gilead—a perilous journey in this male dominated sphere; and Daisy, a teenager living in Canada, who is everything that Agnes is not—but with a secret, and infamous, past.

Atwood's delicious character development is especially effective with Aunt Lydia, a central figure in The Handmaid’s Tale. Now in The Testaments, we see her fleshed out, discovering who she was before the rise of Gilead. In a reflective passage by Aunt Lydia, she asks herself:

“How will I end? I wondered. Will I live to a gently neglected old age, ossifying by degrees? Will I become my own honored statue? Or will the regime and I both topple and my stone replica along with me, to be dragged away and sold off as a curiosity, a lawn ornament, a chunk of gruesome kitsch?

Or will I be put on trial as a monster, then executed by a firing squad and dangled from a lamppost for public viewing? Will I be torn apart by a mob and have my head stuck on a pole and paraded through the streets to merriment and jeers? I have inspired sufficient rage for that.”

Her character Agnes, a young woman of Gilead, grapples with the twists and turns of political and social intrigue: “And this is not heaven. This is a place of snakes and ladders, and though I was once high up on the ladder propped against the Tree of Life, now I’ve slide down a snake.”

As the story unfolds, we are introduced to the character of Daisy, a teenager trying to unearth her mysterious past, finding herself vulnerable and confused as she parses her fate: “The world was no longer solid and dependable, it was porous and deceptive.”

Atwood leads us to the conclusion of this terrifying fictional world of Gilead, but as the curtain falls and the crowd disperses from the theater, what real world do we encounter through the exit doors?

In times of turmoil, we humans rush to elusive havens advertising peace and prosperity. But we must be on guard—perhaps the carny at the gate is simply fooling us with a ‘switch and bait’ in which we give away hard won freedoms for false promises. A timely and poignant line from The Testaments: “How much of belief comes from longing?”

This review was initially published on FUTURISM .

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

SUBSCRIBE TO K.E. LANNING TO RECEIVE BLOG ARTICLES AND AUTHOR UPDATES

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?

August 29, 2019

Review of Author Cixin Liu's "Supernova Era"

Author Cixin Liu

A different side of China's Revered Sci-Fi Author

Cixin Liu’s latest work, Supernova Era (launching this October & published by Tor Books), begins with a terrifying event—eight light-years from Earth, a dying star explodes into a supernova. Undetected by the world’s astrophysicists, the Earth takes a direct hit from massive waves of radiation, with disastrous effects rippling across the globe.

Though many of the fauna and flora of the Earth wither, miraculously, the chromosomes of children thirteen years and younger are unaffected, and the dying parents discover their children will survive the maelstrom. But what happens when children inherit the Earth?

For readers not familiar with Liu Cixin (publishing under the name Cixin Liu), he burst onto the western scene with his novel, The Three-Body Problem, by winning the Hugo Award in 2015, the first Asian writer to snag the award. The novel was also a 2015 Campbell Award finalist and garnered a nomination for the 2015 Nebula Award. In China, his works have received multiple awards and he has risen to be one of the leading voices in Chinese science fiction. He cites Author C. Clarke's intricate world-building as a major influence in his works.

Liu was born in 1963 (Yangquan, China) during the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution—a major impact on his life. Liu was educated at the North China University of Water Conservancy and Electric Power, and then worked as a computer engineer. [primary source: Wikipedia]

Liu’s artistic side blends seamlessly with his engineering chops. In his hands, physics becomes a palette of color and texture—he illustrates the supernova’s impact on the world in poetic prose: “... its light scattered in the atmosphere, turning it into an enormous, blinding, poison spider hanging in the western sky.”

However, unlike his Remembrance of the Earth’s Past Trilogy, Liu’s Supernova Era reveals another side of this creative science fiction author as he spins a tale, written like a history book, of how a random stellar occurrence kills off the adults of the planet, leaving the children to run the world.

Excerpts from the book:

In those days, Earth was a planet in space.

In those days, Beijing was a city on Earth.

On this night, history as known to humanity came to an end.

Influenced by writers such as George Orwell and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (written as a reaction to World War II), Supernova Era takes on a nightmarish societal treatise. Liu wrote the novel in 1989 while in Beijing just before the Tiananmen Square massacre. He describes that night:

In June of that year [1989] I was in Beijing, a city in the midst of political turmoil, and on the night of June 4, I listened in my hotel to the chaotic noise outside, and the muffled sounds of gunfire. That night I dreamed of a limitless expanse of snow, whipped up by the wind into a ground blizzard, and an object—perhaps the sun or a star—glowing with a blinding blue light that painted the sky an eerie color between purple and green. And beneath that dim glow, a formation of children advanced across the snowy ground, white scarves wrapped around their heads, rifles fitted with gleaming bayonets, singing some unrecognizable song as they moved forward in unison. . . . When I recall the horror of that grim scene it still gives me palpitations. I awoke in a cold sweat and couldn’t get back to sleep, and that’s when the germ of the idea for Supernova Era first took shape.

In Supernova Era, an innocent child’s voice recites the terror of a chaotic world held hostage by puerile leaders. Though Cixin Liu writes from a Chinese perspective, his stories highlight the universality of the human experience—the darkness and light—the love and fear—that exist within us all.

Supernova Era was translated into English by Joel Martinsen.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

SUBSCRIBE TO K.E. LANNING TO RECEIVE BLOG ARTICLES AND AUTHOR UPDATES

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?

July 10, 2019

Deep Break

“Deep Break” is an antiquated method of plowing when the soil is overturned and exposed in the early spring to ready the soil for new growth. As I construct my work-in-progress, Where the Sky Meets the Earth, I, too, dig for roots deep in history to create my novel, gathering research to develop both plot and character.

Where the Sky Meets the Earth is a work of literary fiction delving into the consequences of the recent economic fallout entangled with a perceived second coming of a messiah (think a twist on Stranger in a Strange Land set during the Great Recession). A nuclear family has exploded—unemployment, opioid addiction, and divorce. The son, a fourteen-year-old mixed-race boy, disappears into the mountains of Wyoming, seeking a true way of living.

Preliminary cover art

In order to weave a complex story such as this, it takes hours of sifting through threads of history; research on the causes of the Great Recession and the impact on the lives of ordinary people. In order to build the Arapaho shaman character who becomes the lightning rod at the center of the story, I read indigenous history books such as The Wisdom of the Native Americans and In the Hands of the Great Spirit.

But a book that truly resonated with me was an incredible work by Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, published initially in Hebrew (2011), then in English in 2014. This is a stunning book on the anthropology of homo sapiens, and various competitor humanoids, up to the present time. This is not a dry rendition, it is filled with Harari’s philosophical spin on the effects of capitalism, government, and religion.

I was particularly interested in researching the hunter/gatherer period before homo sapiens became trapped into the agricultural revolution, which begs the speculative question—how would society look if that leap hadn’t occurred? And as my novel will attempt to reveal—what if a new messiah led us back to the hunter/gatherer life—turning away from modern society?

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds

SUBSCRIBE TO K.E. LANNING TO RECEIVE BLOG ARTICLES AND AUTHOR UPDATES

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?

March 19, 2019

Cli-fi Meets Biopunk?

Paolo Bacigalupi (Photo by JT Thomas Photography)

Author Paolo Bacigalupi’s debut novel, The Windup Girl [published in 2009 by Night Shades Books], celebrates its 10th anniversary this fall. Critically acclaimed, it was named one of the top 10 fiction books in 2009 by TIME Magazine and won the 2010 Nebula Award, the Campbell Memorial Award, and the 2010 Hugo Award in a tie with China Miéville’s The City & the City. The novel has become one of the defining works of biopunk, a sub-genre of science fiction which explores dystopic worlds of genetic manipulation by power brokers.

The Windup Girl is set in 23rd century Thailand, barricaded with a massive levee system shielding the island from rising sea levels due to global warming. The kingdom, thus isolated from the human-induced plagues of the world, contains the remaining genetically viable seeds on Earth. Within this climate fiction (cli-fi) and biopunk fusion, Bacigalupi weaves an intricate tale of political intrigue between mega-corporations and politicians fighting for control over the last untouched seedbank, complicated by Emiko, an illegal Japanese “windup,” a genetically modified human created as a pleasure doll, but who revolts from her programmed impulses in order to free herself from sexual slavery.

However, this mashup of biopunk and cli-fi subgenres started with Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy of speculative fiction: Oryx and Crake [2003; shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and the Orange Prize for Fiction], The Year of the Flood [2009; 10-year anniversary], and MaddAddam [2013]. Though global warming has affected Atwood’s near-future Earth, the multifaceted trilogy revolves around genetic engineering gone bad—really bad.

Margaret Atwood (Photo by Liam Sharp)

In this apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic saga, Atwood tells an exquisite story of love and madness, but whether the insanity lies within the brilliant geneticist or within the malaise of a broken world is left for the reader to decide. Reminiscent of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses, Atwood masterfully pieces together flashbacks and parallel scenes from different viewpoints, until the overarching story clicks deliberately into place, like a brilliant Rubik's Cube. For you CliffsNotes folks, let me break it down: A complex tale of love in a f#%k-upped world. Get it. Read it. Rumor is the trilogy might be coming to the screen…

The terrifying reality is that our world of genetic engineering is no longer fiction. Like Aldous Huxley’s “fantasy” novel, Brave New World, ready or not, we are on the cusp of a biotechnology revolution. CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) has its roots in the mid-1980s, but major advances in genome editing sprang up in this century. On November 28, 2018, a Chinese scientist, Jiankui He, announced that he had created the world’s first gene-edited babies. And so Pandora’s Box has opened.

Fears over climate change and genetic engineering are threads within the stomach-knotting anxieties of the new millennium. The beginning of the 2000s saw horrific terror attacks around the globe, unending wars in the Middle East, and instability in Europe. As the century continued, a financial meltdown sent economic woes rippling across the world, with unemployment exacerbated by the rise of technology. (Is the angry backlash of populism truly a surprise?)

Behind the curtains of our partisan battles and economic instability, puppet masters jerk the strings of political “hostages” for their own benefit. And we capricious humans play god—global warming melts the Earth’s ice caps and genetic engineering leapfrogs over human morality. But as the tenets of society erode amidst the angst of this new century, a thirst for “why” and “what if” drive writers to attempt to make sense of it all, spinning parables of warning to an unsuspecting, or simply complacent, humanity.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds {2019]

What if the ice caps melted . . . in one human lifespan?

This article was also published in FUTURISM magazine: Cli-Fi Meets Biopunk

January 20, 2019

I’m OK, You’re Not so Great

For a brief moment, I breathe a sigh of relief at the completion of a trilogy (The Melt Trilogy) which has consumed me for years. But there is no rest for the weary—I leap into my next Work-in-Progress, Where the Sky Meets the Earth, outlining the plot and characters, letting my mind wander as I step into the cold, dark waters of a new novel. The other day, musing over my nascent characters, a book that I had read decades ago popped into my consciousness: I’m Okay, You’re Okay, written by Thomas A. Harris, M.D [1967]. Harris linked studies performed by brain surgeon Wilder Penfield, who stimulated the brains of conscious patients during surgery, eliciting vivid memories from his patients, with experiments from Eric Berne, who developed the ego-state models we acquire as humans interacting in the world: Parent-Adult-Child [Transactional Analysis].

In his book, Harris simplified these internal/external feelings and subsequent interpersonal transactions into four categories: 1) I’m Not OK, You’re OK, 2) I’m Not OK, You’re Not OK, 3) I’m OK, You’re Not OK, and finally (Whew) 4) I’m OK, You’re OK. According to the studies, people who were abused as children may conclude that 1 or 2 is their go-to place, whereas a con-artist may be happiest in the I’m OK, You’re Not OK existence. But Harris goes on to describe hybrids of these positions; contaminated Adult states via forms of prejudice by a Parent, or delusions from childhood memories influencing the Child within us. Hopefully, most “normal” folks are in the I’m OK, You’re OK in their attitudes, but who wants normal in their novels?

As a writer interested in creating flawed humans, not caricatures, sculpting realistic characters from clay can benefit from utilizing these various “programmed” human responses. Did the character have a happy or horrible childhood? How might a damaged soul react when confronted?

An editor once told me that one of my male characters should immediately respond to a rather personal question posed to him. I disagreed—many people simply change the subject, and either never respond or respond only when they feel secure. For those characters, body language is their primary communication.

Can these rather simplistic interpersonal responses help guide an author as to whether the dialogue or action is appropriate for the character given their specific background? Perhaps, for we humans are creations of our past, regardless of how we attempt to mask the scars beneath the surface.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds {2019]

What if the ice caps melted . . .

in one human lifespan?

November 14, 2018

Review of Claire Vaye Watkins' novel, Gold Fame Citrus

As California burns . . .

Claire Vaye Watkins - Photo credit: Lily Glass Photography

No matter how you slice and dice author Claire Vaye Watkins, she is an important new voice in literature. Watkins was born in 1984 in Bishop, California to her dynamic mother, Martha Watkins, and her father, Paul Watkins, a former member of the Charles Manson Family. She grew up in the Mohave Desert, in Tecopa, California and Pahrump, Nevada—the desolate landscape a clear influence on her writing. She graduated from the University of Nevada Reno and then earned her MFA from Ohio State University where she was a Presidential Fellow.

Watkins sprang onto the scene with Battleborn [2012], and her debut short story collection won a multitude of literary prizes: the Story Prize, the Dylan Thomas Prize, the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Fiction Award, the Rosenthal Family Foundation Award, and a Silver Pen Award from the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame. Her writing chops led to several honors: a Guggenheim Fellow, one of the National Book Foundation’s “5 under 35” and Granta’s “Best Young American Novelists.” Her stories and essays have appeared in respected publications, such as Granta, Tin House, Freeman’s, The Paris Review, Story Quarterly, New American Stories, Best of the West, The New Republic, The New York Times, and Pushcart Prize XLIII.

I read her speculative fiction/cli-fi novel, Gold Fame Citrus [2015] as California fires obliterated entire communities in the blink of an eye. The novel was named the Best Book of the Year by The Washington Post, NPR, Vanity Fair, LA Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Huffington Post, The Atlantic, Refinery 29, Men's Journal, Ploughshares, Lit Hub, Book Riot, Los Angeles Magazine, Powells, BookPage, and Kirkus Reviews.

The story is set in a near future of extreme drought on the West Coast when most have fled the Golden State as giant dunes devour the land. What remains in the desert are the dregs of society, skittering like bands of rats over the leftovers of the rich and famous. The two main characters, Luz, a former poster child, and Ray, an army deserter, flow through this landscape like grains of sand tossed in the wind, unable to direct their lives. At a gathering of vagabonds, a child appears, lost and yet not lost. Luz decides to take the child and raise her, but the decision shoves them onto a path they had not planned. They flee east into the sea of dunes, imperiling their lives—and their souls.

Gold Fame Citrus is not a happy-go-lucky novel—think Lord of the Flies meets The Treasure of the Sierra Madre—but Watkin adds touches of humor into the crevices of her story, particularly wrapped around the character of Sal, exposed to the outside world through a pin hole of bizarre television shows, such as “Embalming with the Stars” and “Midgets of Middle Management,” and who befriends Ray when he finds himself trapped in Limbo Mine.

Reminiscent of Huxley and LeGuin, Watkins expertly weaves strands of metaphor and angst into this dystopian parable reflecting the ugliness and tenuous nature of humanity on the edge of survival. The insane, the desperate, and the unlucky gather in the middle of the desert into a tribe, devolving into hunter-gatherers, and ruled by an enigmatic master. The fantastical world Watkins creates on an ocean of sand, scattered with peculiar and broken characters, is more akin to a disturbing Alice in Wonderland than “what if” climate fiction. In fact, Gold Fame Citrus is a searing revelation of our human condition and the deep wounds within that never heal, crippling us along our journey in life.

Both a writer and teacher, Watkins is currently a professor of creative writing in the Helen Zell Writers’ program at the University of Michigan, following assistant professorships in creative writing at Princeton and Bucknell. She is the director and co-founder, with spouse, Derek Palacio, of the Mojave School, a festival of art and literature, supporting young writers in Pahrump, Nevada.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds {2019]

This review was originally published on FUTURISM on November 13, 2018.

October 23, 2018

Review of Mary Doria Russell’s "The Sparrow Series" on its 20th anniversary

They meant no harm.

Mary Doria Russell Photo credit: Don Russell

Author Mary Doria Russell was born in Elmhurst, Illinois, into a military family, her father a drill instructor in the Marines and her mother a nurse in the Navy. Raised a Catholic, she left the church as a teenager, but the struggle to parse faith and the role of religion is etched into her works. Russell earned an undergraduate degree in Cultural Anthropology from the University of Illinois [Urbana-Champaign], a M.A. in Social Anthropology at Northeastern University in Boston, and a Ph.D. in Biology Anthropology at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor.

As an author, Russell refuses to be bound to writing within a specific genre—her WWII novel, A Thread of Grace, is a masterpiece of historical fiction based on well-researched accounts and interviews, and a story rarely told of the Italians’ role in saving Jews fleeing from the Nazis. With her superlative research chops, no matter if her novel is set in the future or in the past, she excavates the bones of a story, searching for the life below the surface, and creating characters from the dust to tell the tale.

Mary Doria Russell’s debut novel, The Sparrow, exploded on the scene in 1996, followed by the sequel Children of God in 1998, and this year marks the twentieth anniversary of the completion of The Sparrow series. Critically acclaimed, The Sparrow won multiple honors: The Arthur C. Clarke Award, the James Tiptree, Jr., the Kurd Laßwitz and the British Science Fiction Association Awards, to name a few.

Speculative fiction at its best, The Sparrow weaves Russell’s beautifully developed characters into a story of multifaceted social commentary as fresh and searing as when it was first published. Russell infuses several of her novels with religious references, and the title of The Sparrow is no exception. In the Gospel of Matthew 10:29-31, “. . . not even a sparrow falls to the earth without God’s knowledge thereof.”

The Sparrow is set in the near future [year 2019!] when scientists at the Arecibo Observatory detect radio broadcasts of music from the vicinity of Alpha Centauri, originating from an earth-like planet named Rakhat. The Society of Jesus, the Jesuits, known for their missionary, linguistic, and scientific endeavors, underwrite a voyage to Rakhat, via a modified asteroid, to establish first contact with the planet. The main character, Father Emilio Sandoz, a Jesuit and a superb linguist, believes that God has assembled this group of people, with unique skills and talents, for this mission.

But all is not as it seems when they reach the planet of Rakhat. The crew descends to the surface and acclimate themselves to the new world, studying the fauna and flora of this Eden, and eventually make contact with a tribe of sentient herbivores, the Runa. Emilio Sandoz learns enough of the Runa language to communicate with the gentle creatures and realizes that they are not the ones broadcasting the music. A trader, Supaari VaGayjur, of the Jana’ata tribe, the dominant and carnivorous species on the planet, visits the Runa village, and the expedition discovers that these are the beings broadcasting the songs.

The story deftly flashes back and forth in time from the events during the trip to “present” day after the return to Earth of the only apparent survivor of the voyage, Emilio Sandoz, who is suffering from both physical and mental wounds—and facing a moral crisis in his faith in God.

The Children of God, the sequel to The Sparrow, picks up the story of a shattered Emilio Sandoz, who has rejected God and the priesthood. After the slow healing of his body and mind, Sandoz is now training a new crew for a return mission to Rakhat to find the lost crew members and re-establish contact with the beings on the planet. The story reveals that in the decades since the first mission, a rift has occurred in the social fabric on Rakhat—sparked from human influence.

In The Sparrow Series, Russell delves into the consequences of human interaction with alien life. When humans do make first contact with a sentient being, will they be prey or predator? Will our religious beliefs survive the brave new world of interstellar travel? Just as Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle predicts, observations and contact can affect those being observed, and potentially affect the observers as well, leading to moral dilemmas of epic proportions. A quote from the book says it all: They meant no harm…

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT TRILOGY: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds {2019]

This review was originally published on FUTURISM on October 23, 2018: https://futurism.media/review-of-mary-doria-russells-the-sparrow-series-the-20th-anniversary

July 8, 2018

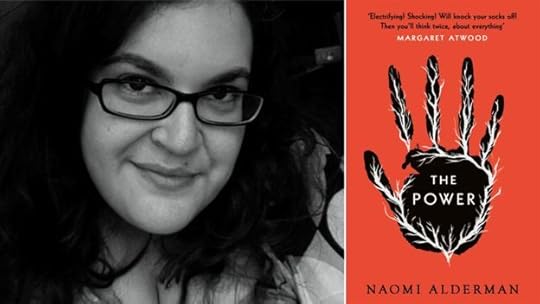

Review of Naomi Alderman's 'The Power'

Naomi Alderman

Never one to be pigeon-holed, Naomi Alderman is a British novelist, game writer, and radio host. As a writer, she is fearless. Her debut novel, Disobedience, published in 2006, immerses the reader into an Orthodox Jewish community through the eyes of a rabbi’s lesbian daughter. Controversial, the novel was critically acclaimed and the San Francisco Chronicle described the story as “acerbic and self-aware.” The Sunday Times named her their Young Writer of the Year in 2007 and Waterstones included Alderman in their 25 Writers of the Future. Her second novel, The Lessons, was published in 2010 and her third novel, The Liars’ Gospel, followed in 2012. Alderman was appointed professor of Creative Writing at Bath Spa University in 2012 and was included in the British Granta list of 20 best young writers in 2013. In 2012, during the writing of The Power, Margaret Atwood selected Alderman as her protégé as a part of the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative, an international philanthropic program, pairing masters with emerging talents.

A stunning work of speculative science fiction, The Power is Alderman’s fourth novel, dedicated to her mentor, the venerable Margaret Atwood. In its essence, The Power is a treatise on the human desire for dominance. From the Greek tragedies through Shakespeare’s plays and now our ‘civilized’ society, the mad pursuit of power and revenge stains our past and colors our future.

Since our early evolution, women have, for the most part, been physically weaker than men. Our small tribal groups created a deep, instinctual need for close societal bonds, but also makes us vulnerable to abuse through this cultural hierarchy. Olivia Butler’s outstanding novel, Kindred, explores how humans, male and female, are conditioned to bondage, and ‘enslaved’ by the insidious mental, and sometimes physical, chains applied by their masters.

In Naomi Alderman’s novel, pollution has caused a mutation, primarily in women, which enables them to direct potent electrical charges through their fingers. The power structure of our society was built on the dominance of men over women. What happens in Alderman’s world when women are suddenly ascendant to men and our gender-based power roles switch?

This complex story is told from the viewpoint of four main protagonists, through the pen of a man conducting an archaeological dig, so to speak, as he researches this ancient and turbulent era. Alderman rips away the accepted facades of women when the taste of power reaches their lips. In a quote from the book, she writes, “Power doesn’t care who uses it.”

The plot is meticulously developed and the diverse characters fleshed out, but one aspect I would have been interested for Alderman to explore: how might this power shift have impacted an established love relationship between a woman and a man? Would the institute of marriage survive this sudden role reversal?

The Power is a fascinating, but terrifying look into a fun house mirror—what is up is down and what is down is up. Though published in 2016, it resonates in our ‘summer of discontent’ as it reveals the ugliness within the human beast, that place where the seed of fear germinates into societal madness.

In June of 2017, The Power won the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, and was named by The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, Entertainment Weekly and NPR as one of the 10 Best Books of 2017. The Power was one of President Barack Obama’s favorite books of 2017. Since its launch, the book has ridden the wave of the Me Too movement, pulling back the curtains on the ubiquitous, yet hidden abuses of power within our society.

K.E. Lanning is the author of THE MELT Trilogy: A Spider Sat Beside Her, The Sting of the Bee, and Listen to the Birds [2019].

This review was originally published on FUTURISM on July 6, 2018: https://futurism.media/review-of-naomi-alderman-s-the-power

March 2, 2018

Review of Adam Roberts’ The History of Science Fiction

Author Adam Roberts

I’m a long-time fan of science fiction. I love the genre in its ability to expand the reader’s mind into the ‘what-if.’ I ran across a review Adam Roberts had published on Margaret Atwood, while I was writing an article on speculative fiction. I ultimately sent the piece to Roberts, and in so doing, discovered his book The History of Science Fiction.

The History of Science Fiction (Palgrave Histories of Literature)

By Adam Roberts

Sometimes history can appear to be dry after the astringency of the moment has passed, but I found Roberts’ book fascinating in his meticulous excavation of ancient literature to discover the bones of science fiction. His thorough research progresses from ancient times to the opening of the twenty-first century to build a comprehensive history of science fiction, including sci-fi magazines, artwork, cartoons, film and television.

Roberts begins with a comparison of Greek mythology to science fiction by underlining how the human mind creates fantastical worlds in which to place heros and heroines into danger, both physically and morally. Particularly, the Greek tragedies were penned to magnify society’s ills and the weaknesses of the human soul. And because of our lingering humanity, these Greek tragedies are still compelling.

Likewise, many of the enduring modern science fiction stories delve into the psyche of society. Brave New World (Aldous Huxley), 1984 (George Orwell), Stranger in a Strange Land (Robert Heinlein), The Lathe of Heaven (Ursula K. Le Guin), and The Handmaid’s Tale (Margaret Atwood) dissect the extremities of the human condition, laying bare the diseased parts for all to examine.

As the book proceeds, Roberts speculates that without the Reformation, science fiction might not exist. I hold some skepticism of his entire premise, but there are points in favor of his theory. As Roberts expounds on the absolute power grip that the Catholic Church had on every aspect of society, including the sciences, I realized that he was on to something. For without liberty to freely research and publish the results, which might infringe on the centrist power of the Catholic Church, then to speculate in a science fiction sense is also forbidden. The blossoming of rational thought drove scientific discovery and the ‘what-if’ nature of science fiction, but the bonds of the Catholic Church had to be broken before free-thinkers could live without fear of excommunication or even death.

Science fiction came into its own during the Enlightenment—the time of Newton, the poetry of physics and the satires of Jonathon Swift and Voltaire. Roberts shows us how Swifts’ Gulliver’s Travels and Voltaire’s Micromégas are classic science fiction in their world-building via the ‘voyage extraordinaire’ and speculation of the human condition. Political turmoil created excellent fodder for writers, and in France, the French revolution sparked a surge in science fiction novels.

Throughout my life, I’ve read voraciously, including classic science fiction, and I loved the writings of authors such as Ursula K. Le Guin and Margaret Atwood. But I was happy to learn of, or in some cases, be reminded of, the numerous female sci-fi authors leading up to contemporary science fiction, such as Margaret Cavendish (17th century), Marie-Anne de Roumier-Robert (18th century), Mary Shelley and Jane C. Loudon (19th century). Roberts notes that the best screenplay written for the Star Wars films, The Empire Strikes Back, was written by Leigh Brackett. The biases of the times don’t always stymie genuine voices, but the history of these authors is many times forgotten.

The industrial revolution created a clash of technology versus humanity—nothing like angst and fear to drive a good sci-fi story. Roberts details the lives and influences of great writers such as H.G. Wells and Jules Verne. And I was amazed to learn how many well-known authors, such as Edgar Allan Poe, had dipped their pens into the science fiction well from time to time (pun intended).

The first half of the twentieth century was chaotic: two world wars, the advent of the atomic age, and the dawn of space travel. The excitement and anxiety of the twentieth century triggered a new wave of sci-fi and, with the advent of modern media, expanded into magazines, comics, film and television.

The disillusionment of the second half of the twentieth century brought a social consciousness and mysticism to the genre. The deft hands of talented sci-fi authors revealed a dark underbelly of our humanity, like Robert Heinlein’s, Stranger in a Strange Land and Margaret Atwood’s, The Handmaid’s Tale. In our current century, sci-fi has developed new sub-genres, such as cyberpunk and a fresh wave of environmental novels.

I particularly enjoyed the subtle humor sprinkled through-out the book: “The unfortunately named Richard Head . . .” Roberts also makes clear his opinions of the novels and authors, which I found enlightening and quite impressive that he himself had read the incredible collection of works that are referenced in this book.

As a sci-fi author myself, I know the derision some critics have for the genre, so it was with interest to read a quote Roberts included from essayist and literary critic, Sven Birkerts:

“Science fiction will never be Literary with a capital L . . .”

But author Hugh Howey’s [WOOL, 2011] answer to a similar question I posed in an interview with him in 2017, as to disdain of SF, perfectly illustrates the issue:

“I noticed this in my years of working in bookstores. Anything from the genres that was considered great was moved into the literature section. Frankenstein, A Handmaid’s Tale, 1984, Brave New World. Others were called “classics,” like [novels written by] Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. Retailers and publishers pluck all the best genre works and decide that they can’t be genre, because genre sucks and these things are good.”

I believe it is the booksellers who place a novel on a science fiction “shelf” and the one variable in this selection appears to be any story in which a time element is twisted whether into the past or the future. With the alteration of that one element as a sole variable, it seems silly, and frankly arrogant, to “trash” science fiction as not literary. In writing, it’s about the quality of the story and characters, just as these criteria are used to judge any literary work, whether it is “genre” or not.

Because of its ability to magnify the excitement of discovery or the ills of our society, science fiction is an important thread in our cultural fabric. A quote from the Roberts’ book I believe wraps up the essence of science fiction:

“SF is exhilarated by and superstitiously fearful of technological advance, or alien life, or the scale of the cosmos.”

Roberts parses science fiction into its multitudes of sub-genres with knowledge, respect and a touch of humor. Beautifully researched, this is a book for readers who enjoy history as well as science fiction—not a light read, but like a good dinner of prime rib and a glass of Malbec—a satisfying one.

K.E. Lanning, author of speculative science fiction: A Spider Sat Beside Her, and The Sting of the Bee [4-4-2018 release]

This article has also been published on FUTURISM, March 2, 2018

The Margaret Atwood 2017 interview. This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.