Young-Im Lee's Blog

February 19, 2019

Author’s Note on Translating Culture

I am delighted to be able to share the new preface to my novel, Forgotten Reflections, available in the ebook version! While this preface has an academic tilt, I hope that it will provide some insight into the difficult task of “translating” culture.

** Please note that this preface contains spoilers.

Author’s Note on Translating Culture

In an attempt to write a preface to my own work, I have abandoned all claims to objectivity. Instead, I write this author’s note with the full force of authorial intent that in the aftermath of Ronald Barthe’s “The Death of The Author” had previously nudged me to hide behind a pseudonym, though with good reason so as to keep alive a part of my late grandmother, Lee Young-Im whose generation has died out or is in the process of dying out as it is replaced with the bright lights of Seoul’s undying nightlife that mask the stars that had once stood witness to my ancestors. This is the premise of my book. Though, in the process of using a quintessentially “Korean” pseudonym, and a cover page of an iconic “Korean” image of a lady in a hanbok (the Korean traditional dress), I have in turn masked my own ‘unusual’ identity that like modern-day Seoul, seems vaguely out of place, disjointed in time as if our all-important ‘traditions’ have somehow been irredeemably lost. Yet, a close-reader would surely know (if I may presume the position of the reader) that the forgotten reflections I speak of is not so much to prompt a reflection of the past in hopes to return to it, but is, as I have asserted in my closing remarks, a vehement call against such a backward-looking reflection:

I cannot help but think there is only so much the previous generation can imagine about what a better future looks like. All the while, I wonder if we are doing the right thing, just adopting the American mask as if it were our own. And to those who look at Korea’s skeletal bright lights and mourn for our lost history and culture, I plead you do not. This story is not meant to romanticize a past that will never return. Certainly not! It is to ask: how can we move forward mindfully without forgetting the past or becoming lost in it. (504-5)

As I look back on a very violent history (of roughly the people of Han that make up the geopolitical ‘nation(s)’ of Korea, (Han-guk, 한국 or “Han Nation”) that spans more than just a few hundred years, I feel compelled to feel a sense of anxiety, or perhaps even presume to portend: “This is our brief interlude of freedom before the bright lights [bombs] come raining down on us again to destroy then rebuild us into their own image. In this brief idyll of freedom and peace, between generations before and after us that will wage war, what will we do?” (505). This author’s note, I hope, will be a small contribution to this reflection that allows us to conceive of a new identity built not on the artifice of a pseudonym that holds on to a dying tradition, nor of staunch nationalism, but on the processes that have brought this book into being and into circulation. Situating this novel as a born-translated work, I seek to place pressure on the notion of the “native” that, in the wake of postcolonial discourse, has already been slowly dismantling. Please note, this preface contains spoilers.

***

Edward Said’s foundational book, Orientalism foregrounds the issue of cultural difference as perceived as “one of its [Europe’s] deepest and most recurring images of the Other,” in which difference as seen as other leads to the perplexing paradox in translation in which the translator’s invisibility “that aims to bring back a cultural other as a recognizable, the familiar, even the same… always risks a wholesale domestication of the foreign text.” The end result is what Lawrence Venuti claims is the inevitable violence that occurs—a violence that is “felt at home as well as abroad.” As Schleirmacher’s astutely observes, “Either the translator leaves the author in peace as much as possible and moves the reader towards him; or he leaves the reader in peace, as much as possible, and moves the author towards him,” and with this acknowledgment of the inevitability of violence, Venuti’s solution is to leave the reader and move the author towards him, with linguistic choices that aim to foreignize the translation so as not to remove the ‘essence’ of author’s cultural and linguistic choices in the original work (Venuti 19-20). Again, we return to the paradox: how can the translator ensure that the same essential difference that is preserved in a foreignized translation is not then perceived as another way to other the text? For instance, how does a translator translate “han,” a word that appears prominently throughout this book, which for the Korean people mean so much more than “resentment?” By keeping it in its phonetically Korean “han,” or by using the hangul (the Korean alphabet) “한”? Perhaps a definition would be needed in the margins of the text in the form of a footnote. Here is one such definition by Suh Nam Dong who astutely defines ‘han’ as:

A feeling of unresolved resentment against injustices suffered, a sense of helplessness because of the overwhelming odds against one, a feeling of acute pain in one’s guts and bowels, making the whole body writhe and squirm, and an obstinate urge to take revenge and to right the wrong—all of these combined. (Yoo 221)

In such a case where one-to-one correspondence is impossible, there emerges a crack in the reader’s understanding—a form of realization that can emphasize the distance of such a word, its corresponding difference in culture, thereby its otherness; yet this is precisely the difference that matters—a difference that shows, in a single word, the gut-feeling that is almost instinctively shared by all Koreans who hear the phrase, “한이 맺히다.”

Yet, for Venuti, whose notion of linguistic foreignization situates the translator between two languages, each tied neatly into their respective geographical location and people group, it is hard to imagine a work that is foreignized, not through its use of language, but through the fundamental altering of the story itself. As Born Translated author Rebecca L. Walkowitz notes, Venuti’s How to Read a Translation “takes for granted that the reader of an original work is supposed to have access to its language and that all books have a single language in which they begin. The distinction Venuti offers between the native and the foreign reader, for example, relies on New Critical standards of comprehension while also invoking confidently the boundaries between insiders and outsiders, between one’s own literary tradition and the literary traditions that belong to others” (173). Instead, born translated works that modify Venuti’s model as David Damrosch has done, begin to conceptualize language as “homes” (66), suggesting that “translated books, like migrants, can make their homes many times, though not without effort, and some more easily than others” (174).

In view of this particular novel that seems to be written in Korean for a Korean audience, then subsequently translated into English for an English-speaking audience, Walkowitz’s Born Translated provides a conceptual framework through which such national bounds are questioned and thereby weakened. Bolstered by Benedict Anderson’s “Imagined Communities,” that places print as the means for a national consciousness to be crafted, the same print can then become the means through which a new community can be imagined. Forgotten Reflections: A War Story is a “born-translated” novel, not in terms of what can be seen on the front cover, but what can be discovered within and through the lives it has lived not just in the linguistic differences that are emphasized, but through such differences that become part and parcel of the narrative itself. It is not necessarily born translated because of the lives and the paths the book has already taken in the western world, but that the work remains proleptic in the lives that it could have taken or could still take if the original Korean script is made available, and as the novel continues to reach a wider audience both in the West, and in the non-western, English-speaking parts of the world. As Walkovich notes, “they [born translated works] are trying to be translated, but in more important ways they are also trying to keep being translated.” In this sense, Forgotten Reflections “occup[ies] more than one place, [is] produced in more than one language, [and] address[es] multiple audiences at the same time” (6). Using Walkovich’s framework, the remainder of this note will briefly trace the life this English version has taken and juxtapose it to Korean version to address the aforementioned paradox of different and other in the linguistic and narrative choices I have made.

If Venuti’s moments of foreignizing linguistic translation accounts for such a difference, but may in turn inflict violence domestically, causing the balance to tip towards reader’s ultimate othering of the text, Walkowitz’s blurring of the boundaries of what is considered “foreign” and “native” not necessarily only through linguistic manipulation but also through altering the narrative plot points may bring the balance back towards a difference that is not completely othered. In such moments of difference (either linguistically or on the narrative scale), the reader is either triggered to 1) make the difference feel at home and/or 2) ultimately reject/other it. As such, Gerald Genette’s narratological concept of metalepsis can further provide a conceptual tool that can account for this moment of trigger. Gerald Genette’s defines metalepsis as “any intrusion by the extradiegetic narrator or narrate into the diegetic universe (or by diegetic characters into a metadiegetic universe, etc.), or the inverse” (234-5), a concept that can simply be understood as narrative moments that call attention to the “the shifting but sacred frontier between the two world, the world in which one tells and of which on tells,” blurring the boundaries between the world of fiction and the extratextual world the reader resides in (Smith 236). If we modify Genette’s concept (not in terms of the paradoxical effect that occurs when the literary fourth wall breaks, drawing the reader’s attention to the artifice of the work thereby causing a mimetic break and/or further drawing them into the work), metalepsis as applied to our moment of difference can function as a trigger of a different sort in which the breaking of the fourth wall draws attention to the foreignness that is either made at home in the reader or is ultimately othered.

On the linguistic level, the novel notes the various instances of metalepsis that showcase transitions from English, Romanized Korean to even Hangul words in the midst of a largely “fluent-sounding” text with ample use of colloquial English expressions. For instance, the aforementioned phonetically preserved word, ‘han’ is used in three different languages (“한,”

“恨” and “Han”) in tandem with a peripheral English definition that appears before its use throughout the narrative in Romanized hangul. Among the many examples of romanization is the colloquial word, “oppa” (오빠) that, in its continued use in the Romanized form does not necessitate a peripheral definition or footnote: “‘Yeong-Hoon oppa! I don’t know why it isn’t working.’ Iseul called her fiancé as she banged the side of the radio” (28). Yet, in a book that largely gives voice to characters in colloquial English, it would be easy to believe that the characters are disjointed in time and place, as if these are “American” or “native English” characters living not in the small rice farming village of Yeoju in 1945, but in modern times, coming from the traditions and cultures that are infused in the English language they seem to speak so fluently. The difference then is reiterated not only by the interspersed use of Romanized hangul, but through the use of hangul in strategic narrative moments such as the retelling of Korea’s foundational myth of the “Legend of Tangun” (420), implying that this story too is likewise another modern retelling of a fundamentally Korean tale. The most prominently featured example of a metaleptical narrative moment is in a play on the Korean word “영혼”:

영혼: Spirit/ Soul*

* Pronounced Yeong-Hon

* Not to be confused with the common Korean name, Yeong-Hoon

* Not to be phonetically confused with the capital of the Republic of Korea, Seoul (477)

Here, the concept of “영혼” (Spirit/ Yeong-Hon) is the play on the phonetically similar character, “영훈” (Yeong-Hoon) whose identity remains a mystery throughout the novel. In this final revelatory moment on Iseul’s deathbed (the protagonist and grandmother figure who is dying of Alzheimer’s), Yeong-Hoon, one of two love interests who first emerge in Iseul’s childhood on the precipice of the Korean War, is finally revealed to be a figment of Iseul’s imagination, though this ghostly figure’s exact genesis (and eventual path) still remains largely unknown by the end of the novel. The various implications are clear:

Is it so hard to believe that an old lady dying of Alzheimer’s would imagine a person into being? She had made up the character, Yeong-Hoon after the disease had taken hold. Furthermore, she had retrospectively reconfigured her memories of her war-ridden childhood and painstaking adult life in post-war South Korea to include the man she had always planned to build her life with, though the war had taken him too soon.

“The man [Yeong-Hoon] laughed. ‘You’ve always had an overactive imagination.’” Here, I imply that Iseul had always imagined the character from her youth and Iseul’s own realization of the fact devastates her: “…realization washed over her. Yeong-Hoon oppa—the man she was betrothed to, the man who had a limp and was her father’s apprentice, the man who had spoon-fed her in those weeks after her father was murdered and Jung-Soo disappeared—was never there.”

Yeong-Hoon’s ghostly figure doesn’t stop him from holding his own agency as he clarifies, “‘I was there,’ he corrected. ‘I witnessed every second of it. But you did it all by yourself; you are stronger than you remember. You got back on your own two feet, buried your father’s ashes by your mother, started making drums for war, and started the paper-making movement in your village’” (482).

And in a story that is meant to carry the weight of war into a modern city like Seoul that holds no remnant of its own tragic past “other than a cemetery and museums that come in vogue once a year—a true testament of how our people tried our very best to forget the problems we cannot fix, as if the war isn’t still ongoing, marching to the rhythm of progress made in the past sixty years to eradicate all memories of our most recent trauma,” Yeong-Hoon is the liminal figure who lives between the past rice-farming villages like Yeoju and modern-day Seoul, between life and death, and perhaps even between this war and the next, whose ghostly presence/non-presence stand for the unseen hand that has guided us to where we are today, but also calls us to usurp the agency he himself cannot fully wield.

On a metaleptic level in which the use of Hangul may jar the reader in its persistent use of peripheral footnoting, phonetic Romanizing and outright use of 한글, the visibility of the foreignizing difference that is maintained at the core of the narrative (not just on the linguistic level) may tip the balance of the paradoxical moment ultimately made at home in the reader. Yet, I hope I have not masked such moments of metaleptic foreignization to stand as symbols for an “authentic” or “native” culture that presumably exists behind such a word like “han,” or any other quintessentially “Korean” aspects of the novel such as my retelling of the legend of Tangun. Instead, as a born-translated novel, moments of foreignization also allude to the multiple “homes” (Damrosch 66) the novel have (or potentially have) as the reader begins to question: what would a moment like the play on the words, ‘Yeong-Hoon’ and ‘yeong-hon,’ ‘Seoul’ and ‘soul’ look like in their original language? The answer is clear: there can be no such thing as the source language! In fact, I would dare argue that that which is conceived of as “authentically” Korean is an image of a past that never existed in the first place.

In this final section, I turn my attention to the other home I wish this novel to be housed—in Korea. Should this novel be completed in its preliminary Korean version I wrote before I began writing the English version, I am certain there will be another “home” for this narrative where moments of metalepsis, though different, would still occur and function in much the same way they do in English.

In evaluating the function of metalepsis in broader sense, the moments in which the author reaches out from the pages of the book to directly address the reader and/or draw attention to the artifice of the work, serve as ways of conjoining the disjointed state of time (and vice versa) that cannot possibly account for novel that is read after the fact (of being written), while the reader is in here-and-now of the present act of reading. Acts of foreignization that I have already elaborated on serve this function, though “foreignization” in the way that it draws attention to itself, can exist as a smaller subset in the larger category of metalepsis. Thereby, in a novel that weaves from the present to the past, purposefully disjoins and conjoins time through methods akin to magical realism (this subject matter could be its own preface), and whose main character, Yeong-Hoon remains the ambiguous figure who literally appears out of nowhere with an unexplained knock on Iseul’s door and disappears, not into death as Iseul does, but whose eventuality is forgotten (or neglected); such moments of metalepsis serve as a method to fold time. The past is made to feel more present in the colloquial language I use for my characters in the Korean War era and the present made to feel stunted in the sparse characterization of my modern granddaughter protagonist. They also bring the readers into this disjointedness, in which their cozy positions as extradiegetic figures outside the immediate action is brought to a halt in a dizzying spread of metalepsis in which the past made present (and vice versa) and ‘foreignness’ of the Korean language made to converge from its peripheral footnoting towards the core of the narrative. And in this brief metaleptic moment when space-time is made other in the reader, the other is then made to fold into the self.

All such moments, I hope, are captured in the English version, yet there are aspects still left ‘untranslated’ or left “hidden” that would serve the same purpose for the Korean reader. The Korean reader would not need me to explain, “Jung-Soo?… It doesn’t sound like a name from that era. Doesn’t it sound like a common name someone your age would have?” (486) as we would immediately know that none of us would have grandparents named Jung-Soo from the moment his name is mentioned on page nineteen. Instead, Jung-Soo would be a friend, a name so common that perhaps we would all know at least one. Neither would it take so long for a Korean to figure out that the Seoul I paint is estranged (almost as if the author herself is estranged from the place), just as my modern-day protagonist, Jia would not resemble a “native” Seoulite we have grown accustomed to. What is instinctive then, are how such folds in time connote the fundamental generational disjoint we have all been experiencing, from a generation that was unanimously and profoundly altered by a war so devastating that there isn’t a mark to be seen in the first world South Korea has become in the span of just two generations. This book is equally for us. I leave this author’s note with a remark that is echoed at the end of the book: “I hope that this particular exploration of the topic of identity will be a source of enlightenment and curiosity for all those looking from inside of Korea, outside or somewhere in between” (506).

Works Cited

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, 2006.

Barthes, Roland. The Death of the Author. London, England: Routledge, 2002, pp. 221–24.

Damrosch, David. Comparative World Literature. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Rodopi, 2011, pp. 169–178.

Genette, Gérard. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1980.

Lee, Young-Im. Forgotten Reflections: A War Story. Young-Im Lee, 2017.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Smith, Barbara Herrnstein, “Narrative Versions, Narrative Theories.” Critical Inquiry 7.1 (1980. 213-36)

Venuti, Lawrence. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. London; New York: Routledge, 2008.

Walkowitz, Rebecca L. Born Translated: The Contemporary Novel in an Age of World Literature. New York, NY: Columbia UP, 2015.

Yoo, Boo-Woong. Korean Pentecostalism: Its History and Theology. P. Lang, 1988.

March 22, 2018

FREE on Amazon

Head over to Amazon for your free copy of “Forgotten Reflections: A War Story”

Free until March 24th.

[image error]

January 24, 2018

Interview with Books and Bao

I’m very excited to share my latest interview with Books and Bao!

The original interview post can be found here.

Interview with Young-Im Lee, Author of Forgotten Reflections: A War Story

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 24TH, 2018

Forgotten Reflections is a tale of survival and the ability to flourish through adversity during a devastating period of modern Korean history: The Korean War.

Young-Im Lee has painted a truly staggering and diverse world that seems entirely removed from the modern day, and yet is immediately recognisable.

I had the opportunity to get in touch with Young-Im Lee and ask her a few questions about her novel, her own life, and her feelings about modern day Korea. Her answers were as thought-provoking and insightful as her fiction.

As a Korean national who spent her youth away from home, you have a unique perspective on your own country. Moving to Seoul, what were your initial impressions with regards to social issues, politics, and education?

When I first moved to Seoul, I was eighteen, young enough to be enthralled by my prospects of studying in Seoul, but also only viscerally aware of the social issues that made the news. Growing up in the Philippines, our family would often host kids who visited from Korea to study English for a few months.

These students tended to be the ones who were having a difficult time adjusting to the rigorous Korean education system and were considering relocating abroad. Because of this, I think had quite a negative impression of the Korean education system from a young age and was quite nervous to relocate to Korea.

Nevertheless, I jumped into teaching when I began my studies in Seoul to earn what I could, only to realize that my fears of the Korean education system seemed to be mostly true.

Rote memorization was the norm and kids were not encouraged to ask questions. Worse yet, I saw children scolded for asking the same questions that I remember being praised for as a child, and the same seemed to occur at home where the parents’ authority was not to be questioned, so reasons were never given for why certain things were the way they were.

I believe a large part of my identity formed around being “different” from these kids, but as I grew older and the kids I taught grew younger, I began seeing the larger social issues that stem from these issues. In an academic setting, I would call this critical thinking (or a lack of imagination), but in a larger social setting, I could see how Korea’s development as a first world country would surely be stunted if the next generation isn’t trained to be leaders, critical thinkers, and imaginative forward-thinkers.

This novel, in essence, is my way of showing how various social, historical and cultural issues have led to the modern generation and is also a cautionary tale that urges us to break the trends of our past to move beyond our traumatic history.

Reading your novel, it only throws into sharp relief how incredibly far Korea has advanced since the Korean war, especially in terms of politics and economics.

We all have ideas on how we would like our own nations to progress; what aspects of Korean life would you like to see develop further (such as in the areas of laws, international relations, feminism, or education)?

I can’t say much about the economy and politics, but lately, I have become more acutely aware of issues that stem from our patriarchal social structure. If my early twenties were marked by struggles of national and ethnic identity, my mid-twenties have been marked by a growing awareness of gender inequality in Korea.

My first real wake-up call occurred sometime during university.

My calculus 101 professor had been extremely generous with his time and had often invited us to expensive lunches. I even went to him for support when my grades were suffering and I didn’t think twice about his generosity other than how impressed I was that an internationally-acclaimed mathematician would be so giving to his students.

A few years later, I received news of a math professor—the very same one from my university who was being prosecuted for sexual misconduct! I was confused, grateful nothing had happened to me but mostly shocked. Before then, it never occurred to me that someone in that position would take advantage of the naiveté of those under his supervision.

Although I do not claim that this case is solely the product of a patriarchal culture, it opened my eyes to various safety concerns and inequality that could stem from not only the physical differences in strength but also the social conditions that keep women silent.

Just a few months ago, I had witnessed first-hand, a couple bickering in the streets outside of my apartment. The conversation became violent and the police were called on to stop the fight. I had walked up to the police officer to make certain he knew the man had beaten her, but the police officer told me (in no uncertain terms) that such cases of domestic violence are never prosecuted and how the woman will not be pressing charges so I shouldn’t bother speaking up.

I can only imagine how much courage it takes for a woman in this situation to run from abuse. But to think the social systems in place are more likely to discourage action from women who are already in quite a vulnerable state made me angry.

There is certainly a long way to go! I believe issues of gender inequality are entrenched in a system, history, and culture that touches every part of our daily lives. I hope to bring more awareness to this issue as I gain a deeper understanding of it.

You’ve cited Murakami as an influence on your writing. Are there any other East Asian authors that have also inspired you as a writer or simply as a reader?

Perhaps because of my international upbringing, I have always felt somewhat limited by categories like “Korean Fiction.” (Although I must admit, I still categorize my book under the “Asian Historical fiction” subsection on Amazon). Of course, I admire many East Asian authors for their ability to represent their respective cultures to an English-speaking audience; however, most of all, I appreciate the way in which authors strive to represent universal issues and values that go far beyond their respective geopolitical borders. For instance, I admire Kazuo Ishiguro’schameleon voice that convincingly depicts various ages, genders, and ethnicities.

As I develop my next writing project, I am becoming more aware of the expectations a reader might have of a Korean writer. In fact, while I am very happy that so many people enjoyed this story, I am also aware that many of the people who have read and commented on my work were from the U.S. or Europe.

While it was always my intention to write for an international audience to encourage those who are coming of age, and to help bring some foreign aspects of Korean culture into context, I had also intended for this book to be read by Koreans or others nation groups who have had a similar historical trajectory of imperialism or colonization to encourage people who have gone through such a turbulent past to understand why we may be having a crisis of identity.

Despite the struggles of reaching an international audience (a struggle that I believe is also universal for many writers), I hope to continue to write with universal issues and values in mind.

Young-Im Lee has also provided us with a short essay chronicling her own thoughts on the novel, what it speaks of, and where the initial idea came from:

I would like to think there are many threads to the story. On the surface level, this book was my attempt to not only shed light on the heroism of women during the war, but also highlight the deep suffering, they experienced and how these unseen joys and sorrows made a mark in the silent records of Korean history—a history that is quick to mark the deeds of men who, more obviously sacrificed their lives as soldiers.

Yet, on a more fundamental level, this is the story of men and women who must find a way to bury their childhood dreams as they face the harsh realities of adulthood ahead. This, I believe, is a universal experience that transcends time and place and affects all generations equally. We all grow up, but what happens when our hopes and dreams are met with reality?How do we come of age? And how do we revive our dreams later on in life and in future generations to fulfil the dreams we were never given the chance to pursue?

In many ways, this book was quite a self-indulgent project that helped me work through my identity crisis. I left Korea when I was one and have lived outside of my passport country for over 20 years. I had always been a “foreigner” and I was comfortable with that.

Like many third culture kids who return to their so-called “home countries,” I was bombarded with assumptions and generalizations from people who probably thought I was strange, developmentally challenged, or just one of those Korean-Americans.

Perhaps, it would have been easier if I could just identify as Korean American. But the reality is, I am Korean by ethnicity and by passport. Simple and clear cut. Or so everyone seemed to assume. It then struck me! These entangled struggles of growing up and dealing with an uncertain identity seemed to logically converge during the Korean War, an era that could encapsulate not only dashed childhood dreams but also the same thread of identity crisis I have been experiencing.

During this turbulent, confusing, but also hopeful period, I could imagine young adults lived with confused identities in the midst of political agenda (During the Japanese occupation, Korean children were given Japanese names and were not allowed to speak Korean). What happens when children, who are never given the opportunity to discover who they are, are suddenly given hope for a better future (in the form of Korea’s independence from Japan and the subsequent creation of the Korean governments), only for these hopes to be dashed by war less than two years later?

A simple line repeats itself throughout the novel: “We were born before our time.”

Each generation represented in the novel reiterates this phrase, whether it is from Jung-Soo’s father who declares he is born before his time because no one could understand the grand visions he had of a full-fledged, developed and thriving Korea, or Jung-Soo who spends the entire novel struggling with his identity, only to discover it at the very end, but never get the chance to live out his visions.

You can purchase this novel with free worldwide shipping here.

It is also available on amazon.

December 22, 2017

Author Talk and Book Signing in Seoul

Join me as I share my thoughts about my novel, “Forgotten Reflections: A War Story.”

Location: 2F, 86, Bokwangro, Yongsangu Seoul, Korea 04406

Time: 4-6pm

[image error]

November 9, 2017

The Legacy of Women in a Patriarchical Society (And a digression on racial issues)

Gender identity politics as seen in mainstream media seemed secondary to the more obvious racial issues that seemed to follow me as an international citizen. After all, my gender was less of an issue when a group of drunk English freshers would pass me by and yell out “Ni-Hao,” as if I were one of the thousands of Chinese students at the University. “I’m not Chinese, I’m Korean,” I wanted to say, but then again, I was hardly Korean, in my mind. Gender certainly didn’t cross my mind when the lady at the checkout counter at the university grocery store would slow her speech to make sure I understood what she was saying as if English were my second language. In these more racially charged interactions I had in the UK, none were blatantly hateful. Nevertheless, they seemed to cling onto me with relentless persistence like that ugly wallpaper you’ve gotten so used to that it barely bothers you anymore.

From my experiences abroad, racial tension is not bred from the blatant hatred one sees on the news and social media such as the cases of police brutality where a single incident is politicized to create an unassailable narrative of absolute right and wrong–of black versus white (though I do not deny that such absolute narratives do actually occur and I understand racism is not the same for all races). On the contrary, such matters are mostly subtle and insidious. They hide in the crevices of narratives that claim to have a clear logic and is unassailably justifiable. That is why they persist.

The same goes for gender issues, though I was blind to it for much of my young adult life. In fact, my own gender didn’t matter to me much while I was in university. I was so oblivious that it did not even occur to me that my Calculus 101 professor in Korea who had often taken us out to dinner, gave us extra tutorial sessions and loved to brag about his most recent international grant he’d received, was actually cozying up to his female students to pressure students into having sex with him. He was later prosecuted and sentenced to prison, and very publicly so. It was all over the news! I remember the chills that ran down my spine when I read the article about his incarceration. I told my parents and joked that I had received all the benefits of passing a class I would have surely failed without any of the negative consequences. Humor was the only way I could to mask my own chilling realization of what could have happened.

When I finally left university and entered into the so-called ‘real’ Korean Society, racial issues took the back seat. After all, I looked exactly the same as any other “native” Korean woman (though I confess the difference between how I felt on the inside and how others viewed me on the outside still bugged me. But I digress; this is a topic for another post).

All of a sudden, I began noticing how people were not allowed to say or do what they wanted because they were too young, too ugly, did not go to the right school, did not have enough money, were too old and had no money, was a woman, or was a younger woman. Patriarchy. It reared its ugly head and did not seem to discriminate; everyone was susceptible to discrimination of some sort if you were not in the right category, though it was clear that women were in the cross-section where the odds were clearly stacked up against us. And the sad thing is, women seemed just as likely to acknowledge their place in the bottom of the food chain, just to receive what seemed like the scraps from men who were charitable enough to share. Laws seemed to be useless. Yes, women were entitled to their equal share of the family inheritance, yet why did I see women forfeiting their right? I asked my mom about this and she explained, “it would be selfish for a woman to expect an inheritance from both her husband and her father. How would the son be able to provide for his wife and children then? It is what our dead parents would have wanted and we wish to honor their wishes.”

What is the legacy of women in this kind of a patriarchal society? Should we fight against the patriarch and become the odd one out in a society where your reputation and livelihood depends on knowing your place? My mother once told me, “Your time will come to choose. Let me decide the way I feel is right and ethical.” In my mother’s generation, the mere fact that she had the right to decide to play her role in the patriarchy is a step forward for feminism. Women, who were once proud of their position in the patriarchy, are now deemed inferior, not only by men but also all those who deem the working/independent woman above the woman who lives off her husband. Beyond the words my mother spoke, I could sense that giving up her inheritance was, in an odd way, her way of usurping her identity as a wonderful mother and wife amidst the voices that seem to demean her position.

When I began writing my book “Forgotten Reflections: A War Story,” I began wondering what the unnamed and unseen legacies of women are in a patriarchal society. When names, buildings, companies and entire fortunes are passed from father to son, what is passed down from mothers to daughters and to their daughters? While my grandfather’s legacy and modest inheritance are passed down to my uncle and his son, it almost seemed as if my grandmother had nothing left to give to her daughters and to me, her granddaughter.

When I was living with my grandmother, I slowly began to realize that her legacy is her love she gives abundantly to her daughters in the form of recipes and food that she still makes for all of us, despite her failing health and lack of money. But it was never enough. We resented her for discriminating, though we had resigned ourselves to our fate as women. I’m sad to say that we aren’t appreciative enough of her generosity as we should be. After all, nothing is as obvious, and as a result, taken for granted as a mother’s love for her children.

Yet, when the war broke out and all male-inheritance, land, and legacies were ground to a pulp, the unsung heroes of reconstruction were the women whose lasting legacy of sacrifice, unconditional love, educating the children, and food (yes, the food!) were ways in which the completely new and empty infrastructure of modern-day Korea were filled with more than just bricks and mortar. As much as it saddens and infuriates me to think that women bolstered the reconstruction of the same patriarchy that continues to treat women as second-class citizens, it is this sacrifice that allowed many of the other wonderful cultural aspects of Korean culture to survive the war. In my case, were it not for the “kimchi-stew” that persists for three generations in my novel, it may have been very difficult to string together a coherent narrative that spans over six decades.

When I reflect on my own family–both my father’s and mother’s side–it is clear that I am closer to one side than the other. While I think of my father’s family fondly, I had never quite had the insider’s perspective of my grandparents, aunts, and uncles as I have on my mother’s side. (This may just be my own personal experience, as I’m sure many people would claim they are closer to their paternal side of the family.) Personally, it is undeniable that my insight into family and culture is closely tied to the things my mother speaks to me about the personal struggles of my grandmother and the rest of her family.

Yet, as big of an impact my grandmother has had in my life, her legacy of maternal love and sacrifice seemed to be fading in this new era of dissent against the patriarchy. What would be left of her legacy if we continue on this path? Like other feminists, I would argue that more respect and compensation should be given to those who choose to take care of the household, while also providing the social construct that allows women to thrive in traditionally male-dominated workplaces. Yet for someone in the middle of this transitional period, I am fearful that everything that my grandmother stood for and has given up for us will be completely forgotten.

As another Korean woman who hopes this society will change in my time, if not in my future children’s time, I believe the power is in our hands. As much as we are tasked to break the glass ceiling in the workplace, I also believe it is worthwhile to consider the ways we might create change where we are. We as women in this society have the difficult task of both standing up for our place in the male-dominated workplace and understanding that, currently, we have the unique role as primary educators of family and social ideals. I admire my mother for this. Although she could not break the glass ceiling herself, she teaches us to do otherwise. Yet, unbeknownst to her, the subtext of her words had placed her as a second-class citizen, below my father who was doing the “real work” and her children who would go on to do “real work.” But until that day comes when both men and women can have equal footing in dictating the workplace and family culture, I wonder if this is a necessary sacrifice in our mother’s generation and even in my generation.

So what is the legacy of women in a patriarchal society? It is the beautiful role women played in bringing this nation out of war and into peace but is also the tragically under-celebrated role of these women that will likely be left in the shadows of the past until the glass ceiling is finally broken, and we as a society begin to appreciate what they’ve done for us.

I hope that this rather long post has been able to highlight the often subtle ways in which both racial and gender issues manifest. As an individual whose childhood and early adulthood was defined by confusion on so many levels, I am certain now that the black-and-white narratives we so often hear have done a disservice in painting a more truthful picture of both racial and gender issues.

I’d like to end this post by emphasizing that my opinions are limited to my personal experiences, and should probably be taken with a grain of salt

September 27, 2017

Author Interview: Modern-day South Korean Education, Dementia and Nursing homes, and Multi-cultural Perspectives

Thank you, Cindy Bohn for this amazing interview opportunity!

Check out the original full interview here.

INTERVIEW:

What research did you do for your book?

Researching for this book seemed to have no end. I visited one of the many museums here in Seoul and found that much of the relevant information could be found online. I tried to channel this feeling of being overwhelmed into the book where we see Jia, the granddaughter, feeling quite helpless in her own search for the truth of her grandmother’s past. After watching a few more documentaries about the Korean War, I did what I could to focus on letters and accounts of day-to-day occurrences in the lives of the soldiers coming from such a multi-national background.

In particular, I found an account of a Korean woman who remembered how grateful she felt as a young girl when the war had broken out. She explained how, for the first time, people focused on men dying, instead of her being a disgrace for having been born a daughter. As shocking as this statement was, it was somewhat understandable considering the status of women at the time. From this interview, the character “Mi-Jung” came into focus who can be found sharing the same sentiment as this woman from the interview since Mi-Jung is born as a daughter to a single mom who was pitied for having a daughter instead of a son.

As for the events/plot that transpires in the story, I was particularly taken by the battle of Chosin Reservoir where UN troops were surrounded by over 120,000 Chinese troops who were hiding in the mountains before mounting an attack in a strategic location that trapped UN forces in the Northern Territory. A task force was created to rescue those trapped, though so few survived that those who did were later nicknamed “The Chosin Few.”

As for the events/plot that transpires in the story, I was particularly taken by the battle of Chosin Reservoir where UN troops were surrounded by over 120,000 Chinese troops who were hiding in the mountains before mounting an attack in a strategic location that trapped UN forces in the Northern Territory. A task force was created to rescue those trapped, though so few survived that those who did were later nicknamed “The Chosin Few.”

While my story is not located in Chosin, I was inspired by this battle that highlighted the mountainous landscape of the Korean Peninsula, the international scale of this war and the heroism displayed by those who risked their lives to save those trapped in by the mountains.

This is a really long, detailed book. How long did it take you to write? Can you describe your writing process?

Yes, it is certainly long! I had been living with my grandmother when the idea first struck and that was over two years ago! While I had written a rough screenplay of this story soon after, I eventually abandoned the project for over a year before finally returning to it, this time opting to write the story in the novel form instead. It took eight months of full-time writing to complete this project.

Writing the screenplay first was helpful since it made me focus on scenes that pushed the plot forward. It made transcribing the story into the novel form somewhat easier, although it took a while to seamlessly integrate the thoughts of each character into prose. I had a notebook dedicated to scribbling my way towards a novel. It was certainly non-linear and possibly the most round-about way of writing, but it somehow resulted in a novel. Honestly, I don’t think I remember it being a “process” at all.

Is this your first book you wrote? What are you working on right now?

Yes, this is my first book. I am currently doing research on post-colonial orientalism. I am grateful for this novel since it inspired a new academic topic of interest. I would love to continue writing fiction, but at the moment, I have been consumed with my research and a part-time job (I teach English here in Korea, which was one major inspiration for the character, Jia).

Part of your book centers around an elderly woman suffering from dementia. Do you have any experience with relatives in nursing homes?

While living with my grandmother, I had visited her sister in the hospice center who was also suffering from some form of dementia. Likewise, my late grandfather showed symptoms while I was living with my grandparents. It was certainly an eye-opening experience and one that was quite scary. Nursing homes have become quite common in Korea and I think I am at that age where I see my parents, aunts, and uncles seriously consider the possibilities of how best to care for our grandparents.

Iseul lives in a tiny village. Her granddaughter lives in a big town. Which one more closely relates to your experience? What are the advantages to where you grew up?

Contrary to what many readers may think, my background is quite far removed from that of Jia’s (the granddaughter). I did not strictly grow up in a city, nor did I grow up in Korea. I actually grew up in a somewhat suburban area in Manila, Philippines which was a cross between a big city and a smaller city. When I first moved to Seoul, I was both enthralled and overwhelmed. At eighteen, I was also living alone in the dormitory with my parents in a different country, which made Seoul seem even more vast. But during the course of my studies in Seoul, I moved to some of the rural areas of Korea for months at a time and found the contrast so shocking! Likewise, my grandfather lives in one of the smallest villages in Mokpo which had always been uncomfortable, to say the least! The toilet was outside and a truck would come and empty it only once a week or so. The house would reek of hay and manure from the barn that was attached to the living space. I was quite shocked to know that people still lived in old-fashioned hanok houses. It was only through research into the tradition of hanok homes was I able to appreciate the structure and utility of these homes that adapted so well to the bitter cold winters and hot summers.

Hanok style house in modern city

Hanok style house in modern cityIseul’s granddaughter faces a lot of pressure about her education. What’s the difference between the American education system and the Korean one?

I grew up in the American-adapted international education system. I had always known about the so-called “horrors” of the Korean education system growing up, but it was never something I experienced first-hand. I now live vicariously through my students who are under the same pressure, and it makes my heart break. On the other hand, what I also see is the resilience of children, though honestly, I don’t think Korean students can imagine it any other way. It is a sobering thought and one that made me want to write about fostering the imagination in students. How else would things change if people can’t imagine a different future?

What do you like to do when you’re not writing? What writers do you admire?

Between my job teaching English and doing research, I feel like the day goes by so quickly!

Honestly, I love knitting! It does take up a lot of time so I’m trying to limit myself J I also enjoy playing the guitar and taking a long stroll around my neighborhood/ nearby Gwanak mountain. I’ve recently joined a writer’s group and it has been so nice to finally meet other aspiring authors.

If I had to pick a few of my favorite novels, it would be Murakami’s “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle,” Bronte’s “Jane Eyre,” Towle’s “A Gentleman in Moscow,” Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse-Five” and Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

If a reader wants to keep in touch with what you’re working on, where’s the best place to keep up with your work?

I currently have a facebook page and a website where I post a few blogs every once in a while, including upcoming writing projects and updates about this book. You can reach me through both of these channels.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/youngimleeauthor/

Website: youngimleeauthor.wordpress.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/youngimleewrite

Author’s Closing Remarks

The closing remarks from the book, Forgotten Reflections is one that I’ve gotten a number comments about so thought I’d share an excerpt from the essay. I hope that it will shed light on how the story took shape and my motivations behind the novel itself.

Author’s Closing Remarks

Why is the Korean War called the Forgotten War? It’s not that we forgot the war happened all together, nor did we forget it because not as many people died in the most gruesome and fashionable way possible in modern warfare.

Perhaps it is aptly named the Forgotten War because Korea had very little to do with why the war was fought in the first place. We were just caught in the middle of a story that is not our own, in an international dispute of those who deemed it more convenient that death and suffering are better contained outside their own borders.

Then again, that is an apt summation of our entire war history.

I’ve always thought the name of our country had some relevance to the topic at hand:

한국 (Hanguk): the nation of Han, or Korea

The Chinese root of the word “Han” has nothing to do with the phonetically identical words Han (one), or Han, the sorrow and suffering brought on by centuries of injustice that leaves our spirits aching. Yet, I wonder if Han (Korea), Han (one), and Han (such sense of injustice) are not one and the same, or at the very least, inextricably intertwined.

Han/ 한/ 恨 is defined as “A feeling of unresolved resentment against injustices suffered, a sense of helplessness because of the overwhelming odds against one, a feeling of acute pain in one’s guts and bowels, making the whole body writhe and squirm, and an obstinate urge to take revenge and to right the wrong—all these combined.” –Suh Nam-Dong (Yoo, 221)

We are not a nation of heroes. We are a nation of survivors who somehow made it out the other end and kept going, just waiting for the next bomb to drop. For a while, I wondered if we had all given up, stopped thinking about what we had fought for, or if we had fought for anything at all. We are all struggling and squirming towards an end that we have yet to figure out for ourselves. Sometimes, I fear we are a nation who has lost the ability to define ourselves.

In the two years it took to write this novel, I kept asking myself: what happens to a nation still fighting the same war three generations later—still fighting for the same reason for centuries on end? What does independence mean to a nation that has never known what it means to be its own nation?

I look at my grandmother and wonder what her generation would have to say to us before they all pass into history. All the more so because the Korea of my grandmother’s youth is nothing like the one I know, with barely any landmarks to show for her time in this world as The Miracle on the Han catapulted South Korea from a third world to a first world nation in less than four decades.

Once, I asked her what she thought about the American military presence in South Korea. She was neither thrilled nor hateful. “It is what it is,’ granny would say. They gave us democracy, but they too came and made us into their own image, like the rest of them. I guess that is what we do—morph so much that we don’t even realize this was never us to begin with.

This is just a story—one that imagines the world as I wish it were, or perhaps as I wish it weren’t.

I have two grannies, one who is just as opinionated, stubborn and loud-mouthed as Iseul. My other granny died a cripple, smiling because she had been beaten if she displayed any other emotion. I never knew this granny and I only know this by rumors whispered by my aunts and uncles. Sometimes, I feel the loss of something I never had in the first place. Perhaps the greater tragedy is never having known.

…

Reference:

Yoo, Boo-wong (1988). Korean Pentecostalism: Its History and Theology. New York: Verlag Peter Lang. p. 221.

September 2, 2017

Author Interview: Tell us about your grandmother’s story

Recently, I took part in an interview on Jill-Elizabeth’s blog that addresses a common question I get from readers. I’d like to thank Jill for the guest post. Here is the link to the original blog post: http://blog.jill-elizabeth.com/2017/0...

You mention that the book was inspired by your grandmother’s own experiences. Tell us about her story and your decision to write the book.

I had been living with my maternal grandmother for a year when one day, I went to watch a movie with her. It was one of those family-friendly comedies set during the Korean War. As I sat there watching my grandmother watch this somewhat “out of this world” film, I began wondering how jarring it might be for someone who has actually been through the war.

I began asking her questions about what she thought of the movie, and though she was polite and said she liked it, I felt I wasn’t getting the full story. I probed her and she began telling me snippets of her life during that era. This time, I was shocked by her response, not because she narrated her story full of emotion and gore, but because she was so nonchalant about the realities of war (bodies strewn everywhere and sounds of death and rape). She then proceeded to tell me one particular story that caught my attention: At around the age of seven, my grandmother stumbled on an underground bunker at her school where she found a particularly white sheet of paper. Without knowing the contents of the page, she had taken that peculiar sheet home. Her brother later discovered it to be a communist pamphlet and contacted the authorities, leading to the arrest and execution of over thirty communists, including my grandmother’s own teacher. For years after, my grandmother’s brother was on the run from family members of those executed that day.

From this story, I began piecing together a plot that included paper, contemplating on its various forms (trees that are cut down to make paper, household items to instruments that seem to give voice to inanimate pieces of wood). It was my way of creating an allegory of South Korea’s development as a country, rising from the ashes of war to become the modern first world nation we are today.

But most of all, I wanted to show South Korea in a more realistic light, not just another rags to riches story, and certainly not as merely the country next door to North Korea. This is a study of national and personal identity, wrapped up in a coming-of-age adventure. It is a warning, but also a call to action to begin to search for our own national and personal voice, despite our long history of foreign invasions.

Pieces of the plot have also been taken from my experience translating for U.S. and Filipino veterans of the Korean War who were visiting South Korea at the time. The little boy “Zion” in the story is dedicated to one Filipino soldier who had come back to Korea in search of a Korean boy who had been his “errand boy.” At the time, no newspaper or journalist was interested in an interview with a Filipino soldier. I am indebted to these nameless soldiers.

July 25, 2017

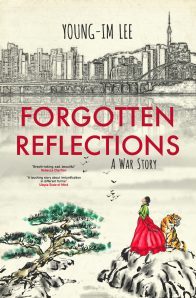

Book Cover Progression

I was very fortunate to find an excellent artist named :Liming:blush: who helped me create a simple but effective cover for my book. The entire process took about two weeks with additional edits about a month later, closer to the release of my book.

When I began looking for a cover artist, I had about two to three chapters left of my book to write and was running out of steam. Working with an artist to create a cover was definitely an excellent way motivate me to complete the book and it certainly made me believe this could actually become real!

I thank Liming:blush: for being patient with my requests. Without further ado, here is how the book cover came to be.

[image error] [image error]

July 20, 2017

Young-Im Lee

Thank you for visiting my blog. I will occasional jot down my thoughts and release new information about upcoming books or events.