Jane Little Botkin's Blog, page 2

February 21, 2020

The Pink Dress

My parents initiated a truce the year I won a beauty-queen title. Actually, I was promoted to queen, but to my mother, how I received the title was of no consequence. In effect, I moved from a dysfunctional middle-class family into a theatrical ménage of high performers, intent on managing all aspects of my life for one year. Along with me, my parents were elevated into the glitzy world of GuyRex, the brainstorm of El Pasoans Richard Guy and Rex Holt. Fondly called “the boys” by those in their widening circle of distinctive friends in 1971, they were inordinately creative and flamboyant. This aspect initially caused my father to dig in his heels even as my mother relinquished my custodianship to the Miss El Paso-Miss America franchise. One would expect this to be a no-win-win for me, though my year was thrilling and certainly eye-opening for an over-protected teenager.

The world I entered was pure allure. It fringed on El Paso’s underbelly where a top stratum of the moneyed and theatrical artists melded with the city’s wilder, but popular element. Bank presidents, country-club auxiliary members, military officers, and actors, along with drug kingpins, high rollers, Hollywood detectives, bail-bondsmen, and defense attorneys, shared a mutual passion for the Las Vegas pizzazz that GuyRex brought the Sun City. Like the shifting desert sands that squeezed the city between the Rio Grande and the Rocky Mountains, El Paso thirsted for such refreshment, welcoming novel and creative ideas that could help exalt the Wild West city to a cosmopolitan destination.

Guy and Rex understood that their success was about showmanship and illusion. There were no nuances. They created pageants like theatrical shows— wildly imaginative, lively musical, and colorfully garbed—with a multitude of post-production acts so that everyone could share a piece of the new queen as her year progressed at events in their own neighborhoods. Not surprisingly, almost everyone invested in the excitement of a new Miss El Paso beauty queen and city-ambassador, from the Chihuahuan governor in Juárez, Mexico, to downtown El Paso city officials; from poor residents in El Paso’s southern barrios to the affluent in El Paso’s upper valley to the west; from soldiers at Fort Bliss Army Base to corporate presidents on Montana Street. And GuyRex did, indeed, deliver. They molded and marketed a beauty contestant in a way that Miss America and Miss USA pageant officials had never foreseen, making the city’s mantra—“El Paso, You’re Looking Good!”—come true.

The premiere GuyRex-Miss El Paso pageant of 1971 was just the beginning for the boys. GuyRex would go on to own the Miss Texas and Miss California USA pageants, and the term GuyRex Girl would be trademarked. From 1985 through 1989, five GuyRex Girls, all Miss Texas title-holders, went on to win Miss USA. Called the Texas Aces (four aces and a wildcard), these women became semi-finalists or runners-up to Miss Universe, catapulting Richard Guy and Rex Holt into beauty-pageant fame. Every one of GuyRex’s girls journeyed a singular experience compared to other traditional beauty contestants. Already gorgeous, the women were re-chiseled, sculpted and refined until a distinctive GuyRex-look emerged.

I know. I was a first generation GuyRex Girl—Version 1.0—an experiment as unique and bold as the new queen-makers themselves. And like all first versions in experimentation, I was flawed, as were my creators. Only in retrospect many years later, do I sense that, like beauty, my year with GuyRex was just skin-deep in my personal growth, and though pivotal, not the watershed of my life. But if I pick at the year’s scab until it hurts, I finally understand how I came to be who I am today.

The post The Pink Dress appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

September 30, 2019

David Street, Hollywood Actor

I just returned from interviewing Jane Street’s grandson and gained a wealth of information. He had already destroyed some of her work, and I was prepared to find little. Imagine my excitement to discover about a 1 ½” stack of her type-written writings. Poems, short stories, jokes, protest articles. Who knew there would be so much more to Jane Street—artist, musician, author. Oh my!

Last year when I was beginning my early research in Denver, I looked for Jane in the Colorado History Center archives and Denver Public Library’s Western History Collection. I was able to investigate Denver’s strong women’s suffrage movement, even holding original Susan B. Anthony letters. Yet I discovered Jane was a ghost—all knew of her presence, some details about her work—but no physical evidence remained. Thrilling and disappointing at the same time. Where was Jane’s DNA, remnants of her work?

Now I am holding her papers in my hands. I have begun reading them and will likely read them dozens of times before I can fully assess what she wanted the reader to know.

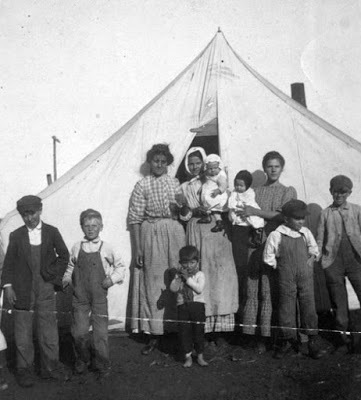

One strand I will have to address in my final manuscript is her motherhood. Without a doubt, she loved her children dearly, so much that some individuals criticized her devotion to the children over the cause of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), affecting her profoundly. With all the turmoil in her life, her children certainly bore the scars, despite her care. As a result, Jane’s sons and daughter traveled similar life-paths as their mother, enduring tragedies of their own. In particular is her youngest son, Charles Patrick Devlin, stage name David Street.

David Street is an unmemorable individual that some of you may have actually seen on the big screen. You wouldn’t have noticed much since David Street was a “B” actor in Hollywood from 1949 until 1962. Yet, the paparazzi followed his activities intently, furnishing black and white glossies for Hollywood rags, generally because he was usually in the company of well-known, glamorous leading ladies, including Jayne Mansfield, Ava Gardner, and Marilyn Maxwell. Though David inherited his mother’s musical talent, he also bore her self-destructive proclivities.

“Tall, dark and handsome singer David Street seemed to have all the necessary credentials for musical film stardom in the 1940s, but his career fell drastically short and today is better remembered, if at all, for his tabloid-exposed private life.” From IMDb.

Actress Mary Beth Hughes, One of David Street’s Many Starlet-Wives

He was married seven times to starlets of incredible beauty—Sharon Lee; Marilyn Maxwell; Mary Beth Hughes; Mary Francis Wilhite; Cathleen Gourley, stage name Lois Andrews; Elaine Perry; and probably the most famous of his wives was Debralee Griffin, stage name Debra Paget. Some of these marriages lasted mere days, some divorces due to addiction and/or spending problems. Jane’s grandson reported that spending $300 on shoes definitely caused stress in one marriage when David was not earning enough to support his lavish lifestyle. Yet he loaned Jane money when she needed it.

Did Jane’s personal relationships and care differ among her children, perhaps because of her life experiences? Possibly. How much impacted the lives of her children? Her papers reveal much. I will have to see what Jane tells me.

The post David Street, Hollywood Actor appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

September 3, 2019

My Book on Feisty Jane Street, Finished!

I have finally finished my book on Jane Street. While researching and writing the book has been an enjoyable journey, so many of the book’s themes are, unfortunately, evident today.

I first came across Jane Street, supposedly a housemaid who

organized other domestics against mistresses on Denver’s Capitol Hill, while

researching for Frank Little and the IWW: The Blood That Stained an American

Family (University of Oklahoma Press, 2017). My own Danish grandmother, product

of a frontier mining environment, had been a housemaid in an elite neighborhood

in Boulder, Colorado, at the exact time of Jane’s story. She had run away, like

many young girls who became domestics, hiding from a forced marriage in Iowa

and searching for work. Regarding Denver’s Scandinavian domestics, a Denver

Public Library historian later confirmed an old adage, “Good girls become

housemaids.” Would my grandmother have heard of Jane?

I have a habit of chasing rabbits, so I immediately paused

to discover exactly who Jane was and if she was significant to Frank Little’s

story. I discovered she wasn’t, but he was surely significant to hers. Frank

Little, indeed, had met Jane, even helped her, but few specifics completed the

circumstances of their meeting. Generally, women, such as Jane, in the

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were not historically well-documented

with the exception of Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and a few other prominent

activist-women. In fact, when I searched for Jane in western labor histories

and women’s studies, she was mentioned marginally, though credited with

starting a housemaids’ union long before significant national conversations

seriously discussed legislative protections for the lowest class of women’s

professions, prostitution excepted.

Only one document seemingly existed, a 1917 letter written to Mrs. Elmer Bruse, previously hidden in the bowels of the National Archives Records Center, where Jane detailed methods that she employed to organize maids. Jane also provided new revelations, how IWW men sabotaged her efforts, even assaulted her. In the age of #Me, Too—with heated national discussions and disagreements concerning victimhood, survivorship, sexual assault, gender discrimination, and false accusations—I was intrigued. This was not just a western labor story, but perhaps a narrative that might shed some light on disparate views today.

Discovering David D. Kilpatrick’s 1992 Princeton thesis, “Jane Street and Denver’s Rebel Housemaids: The Gender of Radicalism in the IWW,” sealed my decision to research the rebel-girl’s story even further. Kilpatrick, a New York Times international correspondent, introduced me to virile syndicalism, basically men joining together to sabotage female trespassers in traditionally male environments (my definition, not Kilpatrick’s). He wrote that Jane’s presence seemed deliberately “almost nonexistent,” an “aberration in a masculine organization in its least adulterated and most radical region [the West].” Kilpatrick primarily used the Bruse letter, contemporary newspaper accounts, and general labor studies to discuss events of 1916 through 1917, a step toward unpeeling the layers of Jane Street that no other historian had ever done. I had to find more about this story that involved core western views.

Being adept with researching old Bureau of Information files, I located a 70-page dossier on Jane Street. Information collected between 1917 (when it was finally legal to confiscate and read suspected radicals’ mail) and other case histories filed well into the 1920s contributed even more information. But it was my final discovery that propelled my decision to actually write Jane’s life story. Through Ancestry.com, I located Jane’s extended family. She had left a pile of writings—poems, essays, short stories—expressing her deepest sorrows and greatest joys, her regrets and hopes, her protests at societal injustices and acceptance of nature’s changes, and her fervent desire for motherhood. Just as wonderful, her grandson, keeper of Jane’s papers, was alive and eager to talk about the grandmother he knew and adored.

By searching Denver’s well-known characters, their homes,

and own correspondences, I was able to paint images of Denver’s Capitol Hill

and flesh-out residents relevant to Jane’s story. Many of the mansions still

exist with little change in appearance, easily helping this Denver sightseer to

envision life in the late teens of the twentieth century. Sometimes I was

fortunate, and a particular mansion came on to the real estate market. The

Campbell mansion’s interior, in particular, is detailed in this narrative by

studying marketing photos. I researched women’s attire, pre-war language and

attitudes, and historical context in order to set Jane into a narrative that,

hopefully, reads better than a generic nonfiction account. Finally, framing

Jane’s unusual life are the labor wars in the western mining camps and the

first Red Scare—its leaders, villains, and victims—when Americans’ xenophobic

and patriotic attitudes melded together to produce a troubling picture of what

our nation can become again.

This book is not a purposeful study of feminism, the IWW, or domestic studies although these subjects are surely present. Instead, the book traces the life of a woman who was not even a maid, her indoctrination into the IWW, her remarkable success organizing the “unorganizable,” and her downfall due to sex. Jane’s two worlds collide—that of traditional motherhood and wife, and that of an unencumbered revolutionary, fighting for an unconventional new world. Themes involving sexual exploitation, violent assault, misogyny, and virile syndicalism permeate the narrative. In the book’s periphery, western women, with their unique spirits and backgrounds, strive to bring independence to all classes of women—except for the housemaids. Thus, Jane Street, who originally supports the IWW’s fight as a class war and not a gender war, evolves into an organizer for female domestics in a battle staged against some of Denver’s well-known suffragists and club women, even as she fights her male counterparts along the way. Both groups betray her, and as the resulting tragedy unfolds, the reader is left with a surprising ending.

I am so anxious to hold this book in my hands. Hopefully you will want to read it too. Unfortunately, university presses do not move quickly, so you will have to wait until late next year or early 2021 to meet Jane. I think the wait will be worth it!

The post My Book on Feisty Jane Street, Finished! appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

August 30, 2019

Always Look Under the Floorboards!

Never know what you can discover in old mining camps—under the floorboards, that is. Forget the hardware lying around, or even grains of gold. So far, my friends have found old photos, food cans (labels still-colorful), tobacco cans, and even cans of condoms. But a miners’ union entire ledger? Letters?

This is a rich treasure, at least to me. I am so excited to announce the discovery of ten letters and documents, originating from Frank Little or Fred Little, Frank’s brother. If you have read Frank Little and the IWW, then you know the relevance of Fred Little’s story. These papers were discovered twenty years ago in the crawl space of a building once housing Mojave’s WFM Local #51 in Mojave, California. The building no longer exists due to an open pit mine, but the discoverer had the foresight to know their significance and save the papers. And, he contacted me. Since the letters are not mine, I cannot publish them, but I will share what is significant with each document should you be one of those folks who can’t get enough of Frank Little or just labor history. Yes, these letters are the “real thing”!

January 13, 1904 – Letter to W. O. Emory in Mojave, CA, from Fred Little in Bisbee, AZ, concerning initiation and membership dues. Emory is the secretary-treasurer of WFM #51. Significance: This is when Frank Little (and Fred Little) first joined the WFM though he is not working in California. Fred Little is in Bisbee where evidently, he worked with Frank. He mentions lots of Mojave boys in Bisbee. Since he and Frank are joining the Mojave local while working in Bisbee, it must be assumed that a transient miner population used Mojave as their WFM base even if not working in that area. No unions were permitted in Bisbee. Further importance is that we now know where Frank first worked when he arrived in California in 1900.

July 16, 1905 – Letter to W. O. Emory in Mojave, CA, from Fred Little in Stauffer, CA, where he is working on a “grubstake.” He sends money for his dues to the Mojave Miners Union and asks that his card be sent to Tulare. He states that he is “about sick of mining,” no money in it, and the mine is hot. He is about to quit. Significance: While I have documented Fred as working as a laborer in Tulare, he also continues to have mining fever.

July 20, 1905 –Letter to W. O. Emory in Mojave, CA, from Frank Little in Tulare, CA, where Frank is recuperating from illness or an accident. He hopes to be back at work by August 1. Frank is behind on his Mojave dues, and asks not to be put on the delinquent list. Significance: Frank Little and IWW catalogs all Frank’s injuries and illnesses. Just added another one!

October 23, 1905 – Letter to W. O. Emory in Mojave, CA, from Frank Little at 405 8th street in Oakland, CA, [Socialist Headquarters] with his upcoming dues [$3] and his WFM card. He asks that Emory stamp and send his card back quickly since he will be leaving soon. He has just had his leg stitched up and plans to return to the mines. The letter is written on Socialist Voice stationary. Significance: Frank Little arrived in Bisbee in October 1903, and now we know he had been in nearby Oakland. While researching the book, I had tried to determine why he was in San Francisco, and investigating this letter clearly proves he was staying at the socialist hall. Is this why he was in San Francisco? Also, another injury. Mining was not for the faint-hearted!

March 26, 1906 – Letter to W. O. Emory in Mojave, CA, from Frank Little in Globe, AZ. Frank inquires about certain individuals while in his new job. Frank is now a “walking delegate” for Globe WFM #60. Significance: We now know the hierarchy of duties that Frank assumed as he rose in the ranks in Globe.

March 28, 1906 – Letter to W. O. Emory in Mojave, CA, from Fred Little in Tulare, CA, sending his 1906 dues to Mojave Miners Union. He is apparently struggling with finding work. Significance: Fred is still trying to work as a miner, and his and Emma’s move to Fresno, CA, may be a result of his not finding work in mining (besides his later, failed political race).

May 27, 1906 – Letter to W. O. Emory in Mojave, CA, from Fred Little in Tulare, CA. Fred states he has had a bad time due to taking care of Emma for month while she was sick. He could not work during this time. He discusses his intention to run for office on the Socialist ticket. He talks about the money necessary to run a campaign, out of poor men’s pockets. He asks for Emory to help raise money to support his campaign. Significance: The letter provides rich details about this failed political race.

July 28, 1906 – Frank Little signed a Physician’s Certificate for G. M. Dodd. Frank is now business agent for Globe Miner’s Union, WFM. Significance: The hierarchy of Frank’s WFM duties continues.

August 7, 1906 –Letter to W. O. Emory in Mojave, CA, from Frank Little in Globe, AZ., on Globe stationary regarding membership information. Frank signs as business agent for Globe #60. The envelope has an IWW stamp. Significance: Love that IWW stamp!

August 16, 1906 – Another letter to W. O. Emory in Mojave, CA, from Frank Little in Globe, AZ. Significance: Frank states that the “Socialist Party [of America] is a pure and simple Reform Party” and that he is a “revolutionist… a member of the S. L. P. the fighting organization.” He plans to go to Colorado in the fall.

I don’t regret what I did not know. Yes, the letters would have added so much more to Frank’s experiences in Arizona. I would love to have just one of these letters. Besides these documents, we have discovered one more photo of Frank. That makes three Frank Little photos existing in the world.

Maybe one day I will get lucky and discover some floorboards that need examining.

The post Always Look Under the Floorboards! appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

August 3, 2019

Researching Wyoming’s Boedekers, Truth or Legend?

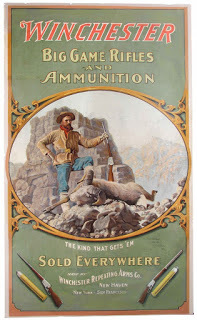

A famous quote best describes the written lore of Lawman Hank Boedeker: “When confronted with the truth or the legend, print the legend.” Though not much is in print about Henry E. Boedeker, during the 1950s, campfire stories embellished tales of well-known past residents including Marshal Boedeker to impress visiting dudes at ranches across western Wyoming. Most specifically, he was reported to be more than an associate of Butch Cassidy’s, whose own history is so thick with folklore, it takes a machete to cut through to the truth. Boedeker did escort an unmanacled Cassidy to Laramie’s federal penitentiary. The exception to Hank Boedeker’s own apocrypha is a common narrative regarding a poster that the Winchester Repeating Arms Company distributed nationally in 1904, after its original presentation at the St. Louis World’s Fair. That, and Hank Boedeker is my grandsons’ third great-grandfather.

A few months ago, I needed to distract myself from thoughts about my mother’s terminal illness and all the stuff that comes along with the impending death of a loved one–in short, an abandon from autopiloting for the next day. As in the past, I found comfort lurking online with Ancestry.com where I could wrap myself around others’ internet lives and the circumstances of their deaths with detached interest. As expected, worries about phone calls, groceries, and doctor appointments soon melted away, along with my reality. To augment the routine joys and tragedies of their digital lifetimes, I searched for all the “hints” Ancestry had posted on various family members in my tree, adding and updating pertinent information to various individuals’ “fact” pages. A mindless, analytical activity, at least for me. And then I shifted to Sarah’s family tree.

Sarah is my daughter-in-law, and like me, she was struggling with her mother’s imminent death. I was instantly ashamed of my pity-party. Sarah’s mom began her death-dance almost thirty years ago when she was diagnosed with Huntington’s Disease, or HD, at about the age of twenty. Most of Sarah’s childhood and adult life has revolved around her mother’s decline. Like me, she has detached herself as best she can from some realities, looking for daily joys in my two challenging grandsons. Sarah laughs at them.

Her detachment from her Boedeker ancestry (pronounced “bed-e-ker”) was primarily because the disease was introduced when her great-grandfather “Bump” Boedeker fell in love and married an immigrant girl from a Polish ghetto known for the disorder. It was not until 1993 that the HD heredity gene was identified. In mid-century Dubois, Wyoming, the Boedeker family had become alarmed and ashamed of the disease’s manifestation in family members, no doubt not understanding that they were procreating the disease’s reoccurrence through their progeny. In fact, as I looked at Sarah’s family tree, I was reminded that she had told me Bump became aimless after his wife Mary had to be institutionalized. He must have felt lost and confused, perhaps even condemned.

My interest began to peak as I filled in family-member facts on Sarah’s Ancestry tree. Then I switched to browsing the internet.

I searched Bump Boedeker, real name John Franklin Boedeker. The first hit was a blog written by Don M. Ricks called “Wyoming History Written in the First Person.” Ricks self-identified as both a historian and storyteller who grew up knowing the pioneers from the 1800s in Dubois, Wyoming. Specifically, he claimed to have known the Boedeker family. I became fully engaged, my misery evaporating, when I found a blog entry titled “Fecundity vs. Ancestry.com: The Boedecker Story” (July 10, 2016). Fecundity was not a word I have ever used: defined, it means “fertility or the production of new ideas.” Every idea would be new to me regarding the Boedekers.

Ricks believed a new street in 1950 was named Boedeker Street after Bump. Apparently Bump hauled the mail and freight from Riverton to Dubois five days a week for years. He drove for the Barnes Truck Company, and Ricks’ grandfather was Cordon Barnes’ partner. This did not sound like the story I heard. A street would not have been named after a freighter. Ricks’ mother lived with a fellow named Little Mike, a bartender, who likely would have known about Bump. Ricks had elaborated that Dubois was a two-bartender town, where Little Mike worked at the Rams Horn and a Big Mike tended bar at the Branding Iron.

Ricks even went to school with two of Bump’s daughters, Nancy and Barbara, and he had had a crush on the latter. I immediately went to my Ancestry tree and made certain this information matched. It did. So far, so good.

Ricks told of living in one of Mrs. Boedekers’ white tourist cabins and boarding at her table for several months. I wondered, which Mrs. Boedeker? He appeared to have an intimate relationship with this family, closer than even its grandchildren and great-grandchildren.The blog continued. Boedeker Street was not named after Bump Boedeker after all. The street was named after Hank Boedeker as was Boedeker Butte on the T-Cross Ranch. This must be the new idea, the fecundity part of the blog’s title, I surmised. I recalled that Sarah had, indeed, told me about a Boedeker ancestor who was a hunter, maybe even a trapper, and who owned a large property that had a mountain on it called Boedeker Mountain. He lost the property because he couldn’t pay the taxes or something like that. Perhaps a bereaved Bump Boedeker had lost interest.

Sarah told how this Boedeker left a photograph on the wall of the old cabin depicting him and his rifle with a mountain sheep he had killed. When the new owners, the Winchester family of firearms fame, saw the photo, they immediately turned it into a hunting poster, and Bump/Hank’s likeness became famous. Turns out the gun in the photo was a Winchester rifle. Where could I can get that poster? I once asked Sarah. She could only recall that her family had misplaced it long ago. When disease consumes a family like HD has done to this branch of the Boedekers, family heirlooms become trivial and irrelevant, and associated family stories bring pain and are best forgotten. My heart broke for the family who had lost touch with a beautiful western heritage.

Ricks continued his story, telling how Hank Boedeker arrived in Wyoming via Illinois and Nebraska in 1883, eventually settling in the Dubois area. As a family genealogist and new historian, I knew I would have to prove these revelations. I began by creating a timeline on Hank noting the source of each new fact and possible fiction. Next Ricks wrote, “Hank was a larger than life Wild West hero.” My heart began pounding. “As a lawman his historical apocrypha are enhanced because he shared the Wind River country with Butch Cassidy in the early 1890s.”

Here was a story, perhaps fiction, but if actually true, then perhaps I could redeem the Boedeker name for my daughter-in-law, even leave a legacy for my grandsons to be proud of. I was now hooked on the Boedeker family, and thoughts of what I needed to be doing for my mother’s care were not all-consuming. I needed this story.

I quickly scanned the rest of Don M. Ricks’ blog on the Dubois, Wyoming, Boedekers. He provided titillating information, such as Hank was Lander, Wyoming’s town marshal. As such, he escorted Butch Cassidy to Fort Laramie to serve a prison sentence for stealing thirteen horses near Meteetsee. In another Ricks’ story, Hank Boedeker disarmed Butch Cassidy and his gang when they rode into town. These anecdotes would need sound investigation, research that I determined I would do. Would I find enough to warrant a book?

Ricks lamented that much of the information on Hank Boedeker was both true and suspect, dependent on “old first-person reminiscences who knew him and casually collected information full of misremembered details, melded events, and enhanced narratives.” Just the type of information I sought when investigating history! These anecdotes, full of faulty information, always have a seed of truth. Their telling brings color to the subject and gives way to begin honest research. The difference between Mr. Ricks and me, I surmised, is that I know how to ferret out the facts once I have the stories. I am an excellent researcher.

The exception to Hank Boedeker’s apocrypha is the common narrative regarding the poster that the Winchester Repeating Arms Company distributed nationally in 1904. Ricks even supplied a photo of the poster. There stands Hank Boedeker on the butte named in his honor, right hand firmly placed on his hip, in his left hand a Model 95 Winchester rifle with its butt and his left boot atop a “record” bighorn sheep. Hank Boedeker presents a formidable character, and, clearly, he and Bump Boedeker are not the same person.

Then Ricks lost me. He next claimed that there were two unrelated Boedeker families in Dubois – Sarah’s great-grandfather, the freighter Bump, and the other Boedeker, Hank the lawman. Two Boedeker lines with no ties in a small Wyoming town? Impossible. Ricks spent a lengthy paragraph discussing anachronistic suppositions, and even he falls victim to dismissing the facts before his nose. He supplied erroneous information: Bump was a German immigrant who came to America following WWI, birth in 1908 and death in 1996. No way he could be Hank Boedeker’s son, Ricks asserts. Within this fog, Ricks still claimed to have known this family branch well.

I went back to my Ancestry tree. Our Bump Boedeker, my Sarah’s great-grandfather, was born 1899, in Lander, Wyoming, confirmed by ten sources, including his WWII selective registration card. Ricks also did not get Bump’s death correct. Ricks in his storytelling had unwittingly added incorrect information to the Boedeker story. Even more glaring was that Hank Boedeker, real name Henry Elmer Boedeker, was, indeed, Bump’s father.

Most disturbing in the blog was mention of an STD, discussion offered up by other Boedeker progeny, supposedly transmitted by a philandering Bump Boedeker, the freighter who spent much time out-of-town. Fortunately, Ricks noted that Bump should have slept in his own bed every night with the Riverton-Dubois trip being a short haul– only eighty miles–and the salacious story illogical. Yet mention of the STD rumor bothered me. I knew it was a shadow-rumor of the genetically-transmitted disease, HD. Don Ricks and other Boedeker family members simply had no idea, Bump’s children had not discussed their mother’s illness, and some had not yet understood their own tragedies would unfold.

Don Ricks ended the blog with colorful memories of his Dubois childhood. Pictured were both Dubois bars, noting that Bump Boedeker delivered a new movie in Friday’s freight for Sunday-night viewing at the Rustic Pine Tavern. The entire town attended regardless of what film he delivered. The other bar, the old Branding Iron, had once been owned by Ricks’ great-grandfather. Built into a sandstone bluff in full view of Main Street, his cases of whiskey were safe from burglars. I could not wait to begin the real research about the Boedeker family. Despite some misinformation, gratitude swelled in my chest–someone had taken the time to record the Boedekers.

The post Researching Wyoming’s Boedekers, Truth or Legend? appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

July 31, 2019

3-7-77, On the Anniversary of Frank Little’s Murder

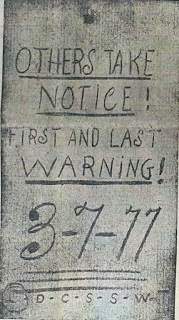

3-7-77. The only clue attached to Frank Little’s corpse swinging on a hemp rope from a Milwaukee Railroad trestle in Butte, Montana, on August 1, 1917. A Bureau of Intelligence agent in charge noted that the pasteboard placard warned the dimensions of a grave: 3-feet wide, 7-feet deep, and 77-inches long. If so, the warning pinned to Frank’s underwear would surely act as a deterrent to future labor agitation. But did 3-7-77 really indicate thus? Why not just write “six-feet under”? After my University of Oklahoma Press editor questioned the assessment, I was driven to do further research.

As it turns out, there are myriad theories concerning the significance of 3-7-7, known as the Montana Vigilante Code, and all stem from vigilante justice. Montanans are and were self-reliant. In a case of disorderly conduct, the code served as a dire warning. Get out of town–-or else. In Frank’s case, when the government would not step in to censor his incendiary language, a copper company acted on its own in Butte. Frank had had two prior warnings. The third warning pinned to his body was for the living.

One theory is that the numbered code first appeared on November 1, 1879, in Helena. The city had become home to desperados who murdered and robbed the citizenry. The Montana Vigilante Code, painted on tents, fences, and walls, strongly advised outlaws to leave town. While some considered the meaning to be that the bad guys had 3 hours, 7 minutes, and 77 seconds to leave town, why say 77 seconds? Why not 8 minutes and 17 seconds? Were the vigilantes poetic? Not likely.

Another theory, a date, March 7, 1877. But historians provide no evidence of a significant event on this day, though this appears to be the most concise, logical explanation.

Still another theory is that the original warning came from a group of 77 Helena men. A secret organization? Perhaps. Undesirables were to purchase a $3 train ticket and leave by 7 AM. Fredrick Allen in his book A Decent Orderly Lynching: The Montana Vigilantes, 2nd ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009), states such. Would recently arrived vagrants know the intended meaning of the code? Hmmm.

A more recent theory is presented below from the Montana Heritage Project:

The inner circle of vigilantes was composed of Masons, a fraternal organization with an ancient history, and the Masons chose the numbers.

According to John Ellingsen, Curator for Bovey Restorations in Virginia City as well as secretary of the Lodge of Masons there, a man died in Bannack in 1863 and requested a Masonic funeral. Though the Masons in Montana at that time were not authorized to hold meetings, they were allowed to conduct funerals. A few men put out the word and were surprised when 76 Masons showed up at the funeral. This was the first time this group of Masons met together and, counting the man whose funeral it was, there were 77 Masons present.

Surrounded by criminal violence, these men, who trusted each other because of their brotherhood in the Masonic Order, decided to fight back. Though their actions were not formally sanctioned by the Masonic Order, these men organized the Vigilance Committee in Virginia City. They decided that for a meeting to take place, the 3 principal officers and a quorum of at least 7 members would be needed. To these numbers, the vigilantes added the number of members present at their first meeting: 77. They took 3-7-77 as a sign, both for themselves and their opponents.

Perhaps. To me, this seems an awfully complicated reason for a simple warning, though Masons keeping the secret is logical.

Today Montana Highway Patrol officers wear 3-7-77 on their uniforms, honoring the early vigilantes in Montana Territory. While they may not know the origin of the enigmatic code, it is no matter—the emblem strikes fear for the criminal and peace of mind for the citizen. The code is part of their collective history and they are proud of it. They should be.

But for me, great-grandniece of Frank Little, the code recalls a despicable act, carried out on this anniversary—one that reminds us Americans how precious our free speech is, and if we don’t pay attention, how quickly a dissenting group can justify taking away our rights.

The post 3-7-77, On the Anniversary of Frank Little’s Murder appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

July 10, 2019

The Bisbee Deportation: An Ugly History That Has Not Been Rewritten

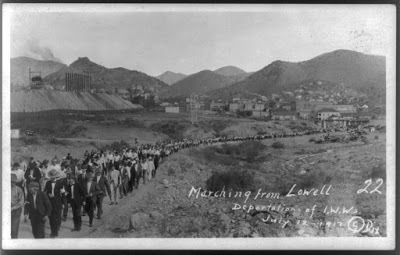

Tomorrow, July 12, is the 102nd anniversary of the infamous Bisbee Deportation. This horrendous action of Americans taking illegal action against other Americans will be memorialized in Bisbee, Arizona, with a host of speakers. Historians will try to explain the illogical hatred and misplaced patriotism of individuals responsible for the deportation, locals will bring to life the deportees themselves, and murdered victims will be remembered. After sweeping the infamous act away for generations, the old mining town will relive each moment of the events from that early summer morning. Most residents know that history by heart now, mostly because of certain individuals’ hard research and preparation used to prepare a centennial two years ago. In fact, Bisbee has done a remarkable job of accepting its history—not rewriting it—instead celebrating the unique role the town played in western labor history. I was present for the centennial and because of my personal family relationship and subsequent research, feel somewhat connected to the events that led up to the deportation. Below is an excerpt describing the deportation from Frank Little and the IWW: The Blood That Stained an American Family.

At precisely 6:30 A. M. on July 12, newsboys circulated an early edition of the Bisbee Daily Review, its banner screaming, “Women and Children Keep Off Streets Today.” A siren at the Douglas smelter blared, not for warning of a Mexican invasion or Pancho Villa attack, but to engage more gunmen. Simultaneously, vigilantes with white armbands ambushed men arriving for morning picket duty outside Bisbee mines and businesses. Other men, armed with machine guns, rifles, and clubs, went door to door without warrants, waking up sleeping families. Husbands, fathers, and sons, prodded with gun butts, were ordered into the streets amidst wails of protesting wives and mothers. While remembering their hats, many men dressed sockless.

A procession of over one thousand men, many of whom were not strikers or even miners, began a three-mile march to the Warren baseball park at 9:00 A. M. Their women followed, climbing into the bleachers to observe what was happening. On the Calumet and Arizona Mining Company office roof, a machine gun was pointed downward toward the captives.

At 11:00 A. M., a train with nineteen El Paso and Southwestern Railroad cattle-and-box cars arrived from tracks at the rear of the ball field on orders of Walter Douglas. Crammed into the cars, deep with manure, were 1,186 men while armed guards stood on top. A few lucky husbands received hastily wrapped bundles of food from wives who fully understood the gravity of the situation. As the temperature climbed above 110 degrees, the train departed. Deportees in smothering boxcars watched their women stumble alongside, slowly fading into the haze of Warren. Without food and little water, the deportees journeyed past gunmen lined on both sides of the track and machine guns on knolls leveled at them. After 52 hours of travel with few stops, the train finally drew into a siding in Hermanas, New Mexico. There the undesirables were abandoned in the hot desert sun. For Bisbee residents, July 12, 1917, would be the day when “patriotism was pitted” against principles.

Interestingly enough, I discovered Jane Street, subject of my newest book, in Bisbee. She arrived just before the deportation to meet with Frank Little. I am currently writing the chapter that describes this meeting, and events from the Bisbee Deportation Centennial flood my brain as I set up Bisbee’s context in relation to Jane. Funny how I have come full circle.

On Monday, July 15, PBS is hosting the American documentary Bisbee’17, that was produced while I was in Bisbee two years ago. Meeting Robert Greene, writer and director, in an ancient-but-neon-lit bar up Brewery Gulch is a memorable moment for me. He thanked me for allowing his crew to film my presentation. No, I am not in the documentary.

See http://www.pbs.org/pov/bisbee17/

A July 12, 2017, NPR recording regarding the Bisbee Deportation used small parts of my presentation, click http://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2017/07/12/bisbee-arizona-mining-deportation for a listen.

The post The Bisbee Deportation: An Ugly History That Has Not Been Rewritten appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

June 24, 2019

Home from the Western Writers of America Conference

Home from the Western Writers of America Conference. For my friends and family who have no idea what this entails–most of you, let me explain briefly! This is the premiere organization that supports Western authors (all stripes), historians, screen-play writers, song writers, poets, and by extension, producers and actors who benefit from the work that the writers produce. Some of them also belong to the organization, hence the fun with Peter Sherayco (Texas Jack Vermillion in Tombstone), Bobby Carradine (in lots of movies but you may remember him as the oldest boy-cowboy in John Wayne’s movie Cowboys), and Howard Kazanjian. And yes, David Morrell, who wrote First Blood that most of you know as Rambo, is even a WWA board member. He is a western writer too.

What is most important, in my opinion, aside from the organization’s support in helping authors craft their works, is trying to keep the genre alive, right down to our children in schools. Our organization raises money to enrich curriculum for schools to help in that regard. So proud of this.

As our world becomes smaller and countries’ cultures intermingle, we risk losing our particular history of identity – the beautiful and the ugly, which we should never candy-coat. If anyone read my blog about the young lady on the airplane who didn’t know who Butch Cassidy was, let alone Paul Newman and Robert Redford, you realize there is a cultural deficiency in America.

The western is not just a shoot-’em-up story. It is our history as Americans, our spirit even today, as evidenced in collections of individual stories about historic events, present-day individuals, landscapes, and American attitudes past and present. Yes, my book about my uncle radical Frank Little fit in beautifully, as will my upcoming book about rebel-girl Jane Street, and, in research-phase, Wyoming Lawman Hank Boedeker. All three individuals were dauntless.

While knowing who a famous western outlaw is not that important, it is essential that our youth understand their history and how it figures into the broader American story, no matter if that child’s family came as immigrants, or descended from a slave, is a card-carrying tribal member, or is a Viet-Nam refugee who embraced the American spirit, which is Western from the get-go. Western history and its stories are still being made–every day. I am so pleased to have found a place that supports my excitement in telling stories, my love of historical research, and networking with the most interesting people in the world!

The post Home from the Western Writers of America Conference appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

April 22, 2019

In Remembrance of the Ludlow Massacre, 1914

I found that Frank Little, subject of my first book Frank Little and the IWW: The Blood That Stained an American Family, often spoke of Ludlow in his last years. His final words regarding the Colorado coal miners’ tent colony were on July 20, 1917, during a fiery speech at Finn Hall in Butte, Montana. Immigrant women and children had suffocated and burned in a pit below a tent where they were hiding from Colorado National Guard’s Gatling gunfire in the 1914 attack. Frank was murdered for his words on August 1, 1917

Frank had been addressing a group of mine workers and others he ascertained to be “prostitutes of the press,” that is, reporters who had been contributing to a narrative against the Butte Metal Mine Workers Union’s strike.

He reminded miners that Rockefeller-employed train engineers and brakemen, members of the AFL, had carried Colorado National Guardsmen and company-hired gunmen to Ludlow to punish a coal miners’ strike against a Rockefeller-owned Colorado Coal and Iron Company. No true union man would have done that, he declared.

Afterwards, famous rebel-girl Elizabeth Gurley Flynn went even further, expressing deep disappointment in Colorado’s women, who sympathized with the mining company. She expected better of them—all mothers, wives, and daughters should have protested in a loud voice against the Ludlow episode. Now as I write Jane Street and the Rebel Maids, about a young woman who went up against the ladies of Denver’s Capitol Hill–some of whom sided with the militia’s thugs, I understand Mary Harris Jones’s statement

“God almighty made women and the Rockefeller gang of thieves made the ladies.”

Typical of labor events during this period, the ensuing deaths became called a “massacre.” My husband and I had been to Ludlow long before I began either book project. With Frank’s words, I wanted to know more.

I was already schooled about labor conflicts involving coal miners on Colorado’s Front Range. My Danish great-grandmother Peterson had married a second time to a Frenchman named Julian Gradel. Gradel had been a political heavyweight and a mine superintendent in Louisville, Colorado. He and my great-grandmother lived among other French and Italian immigrants in a solidly middle-class neighborhood. He was mine management, and they owned their home. Still, there had been multiple labor conflicts in Louisville over intolerable working and living conditions, unacceptable wages, company-hired thugs, union recognition, and martial law.

In 1910, the longest coal strike in Colorado history began, and miners in the Northern Coal Fields, where Louisville sat, were to be out of work almost five years. By 1913, coal miners statewide were on strike, including those in Ludlow.

One week after the Ludlow Massacre, on April 27, 1914, thousands of shots were fired in Louisville. One man was killed, and federal troops were called in. But my step-great-grandfather was already dead from a gunshot wound, though it had been accidentally self-inflicted three years earlier.

Unlike Louisville, Ludlow had been a tent colony of 1200, primarily poor Mexican and Italian immigrant mine workers and their families who had been forced out of their company houses. The camp was located about 18 miles northwest of Trinidad and about 25 miles south of Walsenburg, a historical town best known for its infamous inhabitant, Jesse James’ murderer, Robert Ford.

During a fourteen-hour standoff between hired strike breakers and the Colorado National Guard against the miners, a Gatling gun atop a hill fired thousands of shots into the camp. Women and children fled to their tents—and the cellars dug below them—for protection. After the gunfire ended, among the dead were two women and eleven children who had asphyxiated and burned below their fired tent. Bodies of two miners were displayed near the railroad tracks as a warning to other workers who might consider striking.

John D. Rockefeller claimed no responsibility for the deaths, stating there was no Ludlow massacre. He claimed the engagement started as a desperate fight for life by two small squads of militia against the entire tent colony. Decades later archaeological evidence reveals otherwise.

A monument of a man, woman, and child, in memory of the miners and their families who died that day, looms over the cellar where the women and children died. When my husband and I visited, the white-stone figures were missing their heads, a desecration to their memory, and the cellar’s maw was unsettling. Today all have been restored. Although the United Mine Workers of America own the site, the Ludlow Massacre, a watershed event in labor history, has been designated a National Historical Landmark.

As a final aside, Mother (Mary Harris) Jones, the widow of a miner, is well-known for supporting the miners and their families during the Colorado coal miners’ strike. The folk song, “She’ll Be Coming Around the Mountain,” has been attributed to her travels among mining camps, though the original version was an old Southern spiritual titled, “When the Chariot Comes.”

The post In Remembrance of the Ludlow Massacre, 1914 appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

February 10, 2019

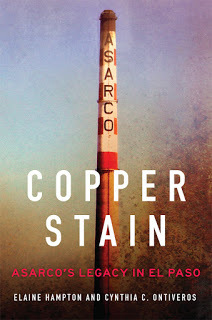

Growing up with ASARCO, EL Paso, TX

The University of Oklahoma Press recently released a new book that certainly caught my attention. Copper Stain, by Elaine Hampton and Cynthia C. Ontiveros, should be an excellent read. I was raised on El Paso’s northeast side but moved near ASARCO (the west side) after I turned 18. The smelter’s community plays a small role in my book Frank Little and the IWW: The Blood That Stained an American Family. I thought I would share an old blog post from my Frank Little website, though Copper Stain should tell a broader, poignant story about the people who suffered the most from ASARCO’s legacy. I congratulate its authors! The old posting begins below:

When I was an aspiring college student at the University of Texas at El Paso back in the early seventies, I had to park my car in a designated area beyond some low sand dunes and navigate a beaten trail just south of the dorms before my feet hit pavement. Immediately to my left was I-10, and beyond that, railroad tracks, the border fence, a corralled Rio Grande, and Mexico. On many occasions, my mouth immediately filled with a metallic taste—ASARCO was emitting fumes on these days. While I understood that the dingy-colored boulders and buildings next to I-10 and the university were due to these emissions, I, like many other students, had no idea that the fumes were laden with toxins. The discolored landscape and leaden taste just came with attending UTEP. I also had no idea that my uncle, Frank Little, had arrived near ASARCO over fifty years prior and barely escaped with his life. He likely was targeting Mexican workers who lived in Smeltertown, a poor community on the United States side of the river, that supplied labor for the American Smelting and Refining Company.

When we students parked on a “scenic” overlook above I-10, just below Sun Bowl stadium, we observed the dismal living conditions of Mexicans who occupied an area called “las colonias,” just on the other side of the interstate. Some families lived in ancient adobe buildings, others in shacks, constructed of cardboard boxes, or plywood, if they were lucky. We watched families bathe and get drinking water from the muddy river. In winter months, since wood was scarce, these families burned tires for warmth, sending black plumes of smoke upward. Before anyone seriously talked about pollution, El Paso’s winter inversion was astounding—and it made for spectacular sunsets.

We could also see ASARCO’s Smeltertown, with its plastered-adobe housing, elementary school, and cemetery. Many had died in Smeltertown. The Texas Historical Association reports that by the time the city of El Paso and the state of Texas filed a $1 million suit against ASARCO, charging the company with violations of the Texas Clean Air Act, the county health department found that the smelter had emitted more than 1,000 metric tons of lead between 1969 and 1971. In 1972, tests found that seventy-two Smeltertown residents, including thirty-five children who had to be hospitalized, were suffering from lead poisoning. A 1975 study found levels indicative of “undue lead absorption” in 43 percent of those living within one mile of the smelter and projected abnormal lead absorption in more than 2,700 local children between the ages of one and nineteen years old. Thus, the elementary school was shut down.

“El Paso sought to evacuate Smeltertown, which a local newspaper described as ‘a grimy feudal kingdom spread beneath the Company Castle,’ but many residents resisted. In May 1975, an injunction ordered ASARCO to modernize and make environmental improvements, which eventually cost some $120 million. Against their wishes the residents were forced to move; their former homes were razed, leaving only the abandoned school and church buildings to mark the site of El Paso’s first major industrial community.” Also remaining is the cemetery.

Despite all the attention to ASARCO and Smeltertown, in the 1970s UTEP’s athletic program provided its athletes summer jobs at the refinery. Go figure!

But what about Frank Little? He had arrived in El Paso likely between November 1916 and March 1917, prior to an IWW meeting. Gunmen, company-hired thugs, had jumped Frank, violently kicking him in the abdomen, the cause of a hernia that almost incapacitated him. By the time of the spring Chicago meeting, he was in great pain. Whether Frank just happened to take the El Paso route after visiting my great-great-grandmother or to agitate El Paso’s ASARCO plant and meet with Mexican agitators there is unknown.

In January 1916, Pancho Villa’s raid on a Chihuahuan ASARCO plant sent workers to El Paso’s refinery for protection. The Mexican Revolution had been raging since 1909 as various leaders (Díaz, Madero, the Magóns, Villa, Zapata, etc.) “ate their own.” The IWW had tried to organize labor against American-owned companies in Mexico but also disliked Villa. In Arizona, site of ASARCO’s corporate headquarters, the IWW was about to organize a strike of metal mine workers, and Frank was in charge.

Paid detectives also could have had information regarding Frank’s itinerary and sought him out for their own reasons. A network of spies operated throughout the mining districts. To facilitate encrypted messages, mining companies had implemented code books that spies and operators used when wiring warning of radical activities among camps and the locations of radical organizers. Could ASARCO’s management have received notice of Frank’s whereabouts?

As for ASARCO, the landmark smoke stacks were demolished on April 13, 2013. Crowds of El Pasoans arrived to view the historic event from the UTEP side of I-10. To many, ASARCO’s demise was long overdue. For me, I now feel slightly discombobulated driving on I-10 since the tallest concrete stack was my point of reference for the west side, aside from the Franklin Mountains. But for many Mexican and Mexican-American families, its destruction marks the end of a poverty-filled era, characterized by illness and death during the tenure of an American-owned corporate giant.

The post Growing up with ASARCO, EL Paso, TX appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.