Peter Clothier's Blog, page 4

March 25, 2021

MISSING THEM...

So, no, it's the other three I feel lonely for. The circumstances of their parents' lives have always kept us geographically far removed: Alice, our oldest, now in her early twenties, was born in Tokyo, where my son Matthew and his wife Diane worked for quite a number of years. The twins, Joseph and Georgia, were born in London when the family returned to Europe, in part to be closer to their other grandparents as they grew up. They have lived in and near London ever since. and thanks to the great distance, the cost of airfare, the obvious need for longer visits if we were to make the journey and the consequent inevitable disruption in our lives, our visits there--or theirs here--have been pretty much biannual, or annual at best.

Which is clearly no way to be a grandparent. Of my own two grandfathers, I knew my father's father only through a single photograph of myself and my sister sitting on his knee when I was about one year old; and a family portrait of a distinguished gentleman with a genial smile, a smart tweed suit and an ascot tie. He died quite suddenly on a business trip to New Zealand before I reached the age of two, so I never got to know him. I did know my maternal grandfather, though. "Grimp", as he was affectionately known to all his grandchildren, was, by the time I knew him, the Chancellor emeritus of Brecon Cathedral in Wales. For the better part of his life he had served as a parish priest in Swansea, and had retired with my grandmother to the village of Aberporth on the Cardiganshire coast. They lived in Penparc Cottage, a low, single-story, white-washed home with a gray slate roof. I remember Grimp as a gentle man with thinning silver hair and a wry sense of humor. He was hardy, too, a strong swimmer, and even into his eighties he would don his bathing suit each day for a morning swim in the frigid waters of the bay. In my mind's eye I best recall him sitting at the breakfast table in the front room of that little cottage, patiently chopping the top off his boiled egg and dipping into the yolk with toast "fingers".

To me, as a child, even this grandfather seemed remote. The west coast of Wales, in those days, was a very long trek from the midlands, Bedfordshire, where my father had his parish. But we did manage the trip almost every year, in the summer, even during the war when petrol was strictly rationed and hard to come by. And Grimp lived on until I was in my late teen years, so at least I knew him as a grandfather. And he remains the model for me until today: kindly and patient, quietly attentive to childhood hurts and fantasies, tolerant of moods and childish outbursts, and at the same time totally secure in his own aging adult world. I certainly remember having felt the power of his blessing, even though it went unspoken.

Perhaps--I would like to think this--I am a similar presence to Luka. For the others, I remain known more by my absence than my presence. From everything I know about my distant grandchildren, they are thriving. After several months of Covid-related socially-removed work, Alice has now returned full-time to her job at a school not far from where she still lives with her parents. Having started out after university as a teacher's assistant (as I understand it), she is now herself a teacher and will be studying for her full qualifications as she works. Of the three, she is the one we know best because she came out a couple of years ago and spent some time with us in California. That was a special joy.

The twins, two years Alice's junior, both started out at university this year, Joseph at Nottingham, where Alice graduated, and Georgia, to my huge pride and joy, at my old Cambridge college where my father also studied in the 1920s. I feel so sorry that their university experience--and their first time away from home--had to start out with all the strictures imposed by our current pandemic; with isolation and social distancing, at a time when the university experience should be one not only of educational opportunity and shared learning in lecture halls and seminars, but also of the first social experience of adult life. (My own first year, in the 1950s, after twelve years of lockdown in boys' boarding schools and adolescent emotional interaction almost exclusively with other boys, was a splurge of beer and ill-fated, fumbling attempts to adjust to the wondrous world of girls!)

In short, I have a grandfather's pride in the achievements of my grandkids, but lack the opportunity to spend time with them as a grandfather would want to. As it is, I send anonymous blessings from afar, and wish them well in everything they do, and hope for wonderful relationships in lust and love, and send the fondest of thoughts their way. And miss them. There was a time--before even I was born, and that's a long, long time ago!--when families of custom and necessity stayed close, fathers and mothers and their children, uncles and aunts, even; and, of course, the grandparents. Our world today is very different, with different social mores, different opportunities for dislocation, different modes of travel. There is something deeply human lost in this, something perhaps to do with the ancient tribal gene, the sense of belonging, of solidarity, of communal life, of family.

I wonder: are we witness to a new, perhaps more rapid stage in the evolution of our human species? Must we now, as we set our sights on previously unimaginable distances--the moon, the planet Mars?--adapt to the effects of dislocation, disconnection, separation?

March 24, 2021

THE GREAT MYSTERY

I wake from this strange and beautiful dream. I have been invited to the studio of David Hockney, to view, or review, his newest paintings--perhaps to write about them for some national magazine. David--yes, I know him, because I wrote that book about him many years ago--David is his familiar, gnomish, shyly gregarious, incessantly cigarette-smoking self. He leaves me alone with the paintings.

Untypically, they are abstractions. There are a number of smaller ones, quite colorful and energized, but these do not first attract my interest. I find myself engaged in a massive canvas, nearly all white. It is perhaps more like a Sam Francis than a David Hockney, but there it is. I find myself lost in that vast expanse of whiteness, the color only in the periphery of my vision. There is an awareness somewhere at the back of my mind that I am supposed to have something to say about these paintings, something to write, but now I realize that I have no words. I have nothing to say.

Rather than being worried about that familiar obligation, though, as I would have expected, I am overwhelmed instead by a sense of serenity. Lost in the whiteness of the painting, I come to terms with the simple understanding that this is a great mystery...

And then, no. That this is the great mystery.

And I am content to have nothing to say.

March 18, 2021

THURSDAY

March 16, 2021

SURGERY

I have to say that I'm relieved to have the surgery sooner rather than later. Friends who have been through the procedure assure me that it's a suprisingly easy process, and that recovery is very fast. They have you back on your feet almost immediately following surgery, and there are follow-up physical therapy dates the same day, the next day, and several days thereafter. I hear, too, that it's a great release from the pain that has become familiar in recent months, almost a friend. The pace of progress in medical interventions such as this has been little short of miraculous. Hip and knee replacement have become pretty much routine procedures. Just twenty years ago, did these things even exist? I suppose so, but they were certainly far less common than they are today.

Today is a bright one, sunny and cold in Southern California, as I sit looking out over our balcony, past the city of Hollywood to the hills. We seem to be nearing not the beginning of the end, as Churchill said, but at least end of the beginning of the battle against the pandemic that besets us. If public health experts are to be believed, as I think they should be, we need more patience than many are now showing if we are to persist. We could very easily mess this up and find ourselves back at that proverbial square one. Let's hope not!

March 15, 2021

NO MORE EXCUSES

From what, then, have I been excusing myself? What's the Big One? Obviously, undeniably, it's a return to the not-quite-yet-finished and not-quite-yet abandoned novel on which I worked for a full half-year and which got shelved after the completion of a second--and what I imagined to be the final--full-length draft. Just as I imagined I was done with it, a glaring flaw became unavoidably apparent. I had known all along that it was setting there in the back of my mind as I was writing but I chose not to recognize it because... well, perhaps because I was just too lazy and chose to brush it off in my haste to get the damn thing finished.

So anyway, there it was. There it is. A piece of work that requires a whole lot more time and effort than I have already devoted to it, and I have chosen to let it sit and allow the fear to build.

There is, to be honest, another factor that's at play here: self judgment. Or perhaps instead, or also, the fear of others' judgment. That (significant!) part of me that embraces the teachings of the Buddha raises thorny questions of Right Speech, Right Action, Right Effort, Right Everything, when it comes to the novel's dominant theme--human sexuality; and I ask myself why this theme continues to haunt me, even at my now advanced age? Should I not know better?

I do not have an answer to that question, but I know that it contributes to my reluctance to return to what I started. And it occurs to me that to be attached to having an answer is simply one more excuse and that the (significant!) part of me that is a writer will not rest easy if I continue to prevaricate. It's time to find the courage to return to work!

March 12, 2021

A PUZZLE

And then there is this book that I still keep trying to finish. It's a piece of fiction. I thought to have finished it a couple of times already, the first time as a "novella." Then a friend read it and made some rather astute comments about a dark side to the story that remained unexplored. She was right. There was much more work to do. So I set about the work and thought to have finished it yet again, this time as a full-length "novel"; and had in fact sent it off to this same friend for a second read when I stopped short and realized that I still had a very basic question that remained unanswered: what was the point?

That's a pretty fundamental problem. It was something I had "known" all along, with a kind of uncomfortable awareness, but without the kind of clarity that would have helped me recognize and address it. I had all these events taking place and people participating in them without any particular reason for doing so. There was a story, in other words--well, a string of stories--but no "arc" to connect them, no initial issue for which to provide a resolution at the end. It lacked the kind of necessity that's required for compelling reading.

And with the realization of this problem came the glimmer of a promise for its solution, a change in the early pages of the book that could motivate my characters and provide a reason for them behaving in the way they do. With it, they would have something to gain and something to lose by their actions. There would be, in other words, a point.

It has been several weeks now since I arrived at this insight and I have still not found the kind of energy and motivation it would take to make the changes. It's as though I have so thoroughly worked through what the book was asking of me that have no longer any reason to actually write it. It's a curious and uncomfortable place in which I find myself. I have given myself leave to sit with it a while longer to see what happens. Meantime, I keep promising myself to come back to The Buddha Diaries--which, today, I have!

February 26, 2021

ONE HOUR/ONE PAINTING

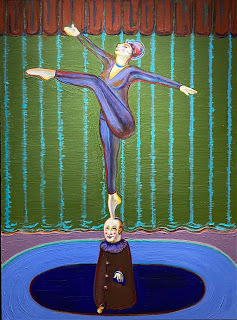

I offered this current session at Laguna Art Museum. The painting is one in a new series of clown paintings by (now 100-year-old!) Wayne Thiebaud. I'm not keen on the impression of myself that I create (no one likes looking at pictures of themselves!) but once you get past me and my blurb to the painting I think you'll find the experience worthwhile.

I offered this current session at Laguna Art Museum. The painting is one in a new series of clown paintings by (now 100-year-old!) Wayne Thiebaud. I'm not keen on the impression of myself that I create (no one likes looking at pictures of themselves!) but once you get past me and my blurb to the painting I think you'll find the experience worthwhile.

February 19, 2021

THEY KEEP COMING...

... the lessons, that is. They keep coming...

I woke this morning early with a feeling of release. I thought to have finished the book I have been working on with a completed second draft, and had decided to put aside at least for a few days the work on taxes that will need to be done soon. From that perspective, early on, waking up in bed, the day promised to be one in which I could enjoy doing absolutely nothing except those things I felt like doing. It was a good feeling.

Then...

In my morning sit, I had a sudden insight about the book. I have suspected at some restless place in the back of my mind that there remains a basic, unaddressed problem that could be boiled down to one simple, rather devastating question: what's the point? And the answer popped up unexpectedly, annoyingly, provocatively this morning, as I sat in meditation. It's a good answer, but it means a lot more work. It means going back to the beginning again and making changes throughout. It might mean a radical change at the end. I don't know yet. But I do know that this new idea would improve the book immensely--and that it will take a whole lot more time.

Damn!

Worse. I checked my email, as I usually do first thing (by this time there may be fifty, sixty, seventy new arrivals, most of them of no earthly interest), and found a blizzard of alerts from the site I use to stand guard over my passwords, all notifying me of a possibly serious compromise to my dozens of password-protected accounts. Which means--unless I find some other way to deal with this--revisiting all those websites to make changes to my profile and security, at the cost of a huge amount of time and aggravation.

Damn again!

This one is a lesson I've had to relearn too many times already. Nothing is stable, fixed, immutable. There is absolutely nothing that can be absolutely counted on. Everything is subject to the whims of change. The only constant is inconstancy. And the only reasonable strategy is to flow with the change with as much equanimity as I can muster. I fall back on more than 20 years of practice--only to find that the supposed wisdom gleaned from its undoubted benefits can suddenly and ignominiously be snatched away. And I'm back, as they annoyingly say, to square one: beginner's mind.

February 12, 2021

Dedication

This morning I woke early with words in my head. I could not get back to sleep without finding what they wanted to say and committing them to memory, so that they'd not be lost by morning. I have been working toward completion of a new book, and these words came to me as the...

Dedication

To those who love& those who have been loved

To those who touch& those who have been touched

To those who hold& those who have been held

To those who posses& those possessed

To those who need& those whom others need

To those who use& those whom others use

To those abused& those who are abused

May we all findforgiveness, redemptionand restoration of lost innocencein our hearts

January 18, 2021

LATE BLOOMER

Late-Bloomer: Thoughts on the Work of Ellie Blankfort By Peter Clothier

We have seen them before—art world professionals who have turned to making their own art in their later years. I think of the dealer Nicholas Wilder, who represented the most prominent of contemporary artists at his Los Angeles gallery in the 1960s; and of Henry Hopkins, who, along with the museum curator Walter “Chico” Hopps, helped cultivate the first great wave of contemporary art collectors in Southern California, to the eventual benefit of our museums.

There are others, among them the subject of this essay, Ellie Blankfort, a multi-talented professional who started her career in the art world as director of the Art Rental Gallery at the Los Angeles County Museum, where she associated with many of the aspiring young artists of the early 1970s. She went on from there to open her own gallery, representing young contemporaries—several of whom used it as a springboard for their own distinguished careers.

To better serve their interests, she worked to qualify herself in the field of interior design and began to offer her services as an art consultant to both private and corporate clients; among other projects, she directed an art program at the Frank Gehry-designed Loyola Law School and oversaw public installations at CalTech and other institutions. And tiring eventually of the commercial aspects of consultantship, she turned her natural talents and insights to an artists’ advisory service, working one-on-one to guide artists in their studio and professional lives.

It was to better understand the challenges of the working artists she advised that she first tried her hand a making art herself. She brought no formal training to the effort, but a formidable eye and a grounded knowledge of art history—particularly contemporary art history—that stood her in good stead. From her earliest years she had been surrounded by art in her home; her parents were among those early collectors groomed by Hopps and Hopkins. At their dining table they frequently played host to prominent artists—Claes Oldenberg, R.B. Kitaj among others; her first car was purchased by her father from Ed Kienholz, making ends meet as a used car dealer before his subsequent fame; the clunker bore an uncomfortable resemblance to that artist’s notorious “Back Seat Dodge.” Later, throughout her professional life, she honed her eye to discern for her clients the best of the best.

Her first foray into the creative world was in the studio of a long-time friend, the artist Marsha Barron, who gave her the space, both physical and creative, to experiment in form and color with different media, mostly on paper—pencil and paper, watercolor and pastel—striving to give expression to an emerging personal vision that was at once free-form and lyrical, visually astute yet unhampered by formal convention. Well aware that her representational skills were inhibited by the absence of art school training, she allowed herself to play between abstraction and evocative suggestions of imagery. The results were a validation of her natural, innate sense of color and painterly composition, and gave her the confidence she needed to take her efforts further.

That “further” was enabled by the opportunity to construct a studio for herself in the course of a remodel at her Laguna Beach cottage. Over the years, it has proved both a beloved invitation and an intimidation as she moves—as do the great majority of artists—between confidence and self-doubt, creative assurance and self-critical disapproval of her work. No one who has stepped inside her studio, however, and looked around at the dozens of pictures that crowd each other out against the walls could doubt the fecundity of her vision and her dedication to the pursuit of an ever more accomplished realization of her creative talent.

Blankfort’s process has remained the same since her earliest efforts. She tends to start out each painting with a graphite rendering, meticulously drawn, or sometimes traced, and then transferred to the surface of a board prepared with a smooth coat of gesso. For a number of years she preferred to limit herself to a relatively small scale, usually a square foot in format; only fairly recently has she decided to accept the challenge of a larger scale and to expand the horizon of her possibilities. Once satisfied that the drawing meets with her intention, she adds color—gouache, oil, ink, or acrylic paint—filling in spaces, defining areas and lines, usually in smooth, thin layers, to complete the painting.

Where does this work belong? It combines a number of aspects of the work she grew up loving as a young person and admiring later in her professional capacity. There is, primarily, the thrill of color, which she embraces with the verve of a Kandinsky; the interplay of disparate, intricate elements of a Paul Klee. There is an element, too of hard-edge, sometimes geometric abstraction—a demanding, often reductive mode of expression that makes it possible for her to maintain the element of control she likes and indeed perhaps needs to compensate for a hesitation about still-developing technical skills. But ambition for growth and ever-increasing success in the implementation of her vision has pushed her far beyond the strictures of geometric straight edges, blending them with softer, more organic, more playful shapes and suggestive images---the Jungian anima, perhaps, arising to complementing the animus—that allows her to communicate a greater range of emotional complexity, something deeper and richer than form for form’s sake alone, or color exploited merely in the service of design.

Predominantly, Ellie Blankfort’s paintings project a sense of joy, an exuberance, a delight in the challenges of painting itself, the composition of line, space and texture, a complex dance of richly saturated color and a rhythmic interplay of forms. She has an unerring eye for the way a painting can be made to work, endowing her images with a natural and pleasing sense of balance—or carefully calculated imbalance—that engages and gratifies the viewer’s eye. Her abstract paintings end up looking as they should, and, for our pleasure, “just exactly right.”

Still, something—perhaps the dire nature of our times along with the threat of global social and ecological disharmony and the rages of a deadly pandemic—drew her back to a need for relevance, the need to “say something” with her art. She began to introduce unmistakable, if abstracted images of ocean, sky, interiors and exteriors of buildings, plants and artifacts, toying once again with the possibilities of representation in the context of overall abstraction. She brought in suggestions of a third dimension, doorways opening into ambiguous and disorienting spaces, calling to mind the lyrical spaces of a Helen Lundeberg or the confusing paradoxes of an M.C.Escher, thus finding a way to invite the viewer more intimately into the surface of the painting. The coronavirus also found a way into her images, black, organic, ominous—and yet somehow also humorous—sneaking through hidden cracks or windows and creeping, vine-like, across somehow innocent and unsuspecting surfaces, a quirky commentary on the odd, threatening nature of our times.

In recent work, she has been experimenting with the incorporation of metallic-hued medium, combining the eye-catching appeal of gleaming surfaces reflecting ambient light—they look particularly gorgeous, I have noticed, when mirroring the setting sun—with the geometric structure of painted areas and the natural simplicity of plywood surfaces, left exposed for effective contrast. These works speak quietly of the ever-shifting balance between artifice and nature, the work of the artist and the light that informs it with the immediacy of life. There is too, I believe, in these works, a more than casual reminder of the great Southern California school of artistic innovators who thrived in the source of her early years in the art world—those working in the realm of visual perception, employing the non-traditional properties of Light and Space.

The constant struggle in Blankfort’s paintings is to find the right balance between freedom and control, between whimsy and serious intent. In part this results from the tension between the well-honed, discerning sophistication of her eye and the largely self-taught nature of her technical skills. At their most successful, her paintings take advantage of this very peculiar—by which I mean, individual, unusual, indeed rather special—ground from which she works. Her paintings continue to inspire confidence that she will continue to test herself against her own rigorous expectations. I look forward, always, to seeing more.