Linnea Dunne's Blog, page 3

September 7, 2017

To the woman who told me all my child needed was a hug

You came into our lives at about 8.10am this morning. I was standing outside my house, my youngest kid kitted out and ready to go, his older brother screaming hysterically at the top of his lungs, quite possibly waking every single person in Drumcondra our side of Griffith Park. See, he didn’t want to go to school by scooter. “Awww,” you said, tilted your head and looked at my son, and I ignored you.

“Give him a hug,” you said then, with a tone that struck the perfect balance between empathy and demand. If my morning had started off in a bad way, it shot up on the crappy-morning metre at this exact moment, but I kept ignoring you. You couldn’t know that I’d had no more than four hours of very broken sleep, that I had a splitting head ache and was running out of patience as well as hugs.

Then you walked through the gate, into our garden, right up beside me to where my child was now hiding behind my legs from the strange woman suddenly practically in our home, repeating your “awwww”, and I couldn’t ignore you anymore. “I think I’d better deal with this myself – thanks,” I said, softly, and it suddenly became clear that you were not going to listen to me. “But the child needs a hug,” you repeated.

“You need to let me deal with this myself,” I said again, colder this time, possibly even raising a hand slightly. “Please leave now.” I was getting upset but holding it together. You were definitely crossing a line or five, but you couldn’t know that he’d had plenty of hugs and the clock was ticking and we’d reasoned it out and gone through options and choices, and I was desperate.

Then you turned around, returned to the path, stood there and looked at me: “It’s very clear he doesn’t want to go wherever he is going.” I don’t know what you thought I would do with this information; child doesn’t want to go to school, so child stays at home – was that your thinking? But the thing is, Sherlock, that the child did want to go to school, and he was starting to miss out. It was the scooter he didn’t want, and a long list of other things that had already happened and I could no longer do anything about, such as me having closed the door, us having had no ham for his lunch box, and a million other things that probably had very little to do with scooters and doors and ham but became really very important and hysteria-inducing at this very moment in time.

“I’ve worked with children for years, it’s very clear that…” and that’s when I lost it. See, I’m a great parent of other people’s children too. I know how to prevent their meltdowns, how to get them to eat what’s on their plate and maybe even sleep through the night. I know how to help them snap out of hysterical meltdowns and distract them through a long walk they don’t want to take. Perspective is a beautiful thing, but it requires exactly that – perspective; it can’t be passed down in a moment of desperation.

I was angry, shaking, and could no longer stop the tears. I told you that this isn’t how it works; you don’t get to go around giving unsolicited advice to parents in stressful situations, especially when they explicitly ask you to leave them alone. I told you that you didn’t know a thing about my morning, how long this had been going on, how many hugs I’d already tried and how we got to a situation where we were standing outside of our house waking the entire neighbourhood. And I put on quite the show. I had to, because you didn’t take a hint, nor did you get it the first few times I told you to take your unsolicited advice and shove it somewhere it hurts, far away from my sight.

So how did we get to a situation where we were standing outside of our house waking the entire neighbourhood? Why was the scooter so important, why had I run out of hugs, how did my son get so tired and overwhelmed that the only way he could communicate with me was through a meltdown over a scooter, and why, when things went from bad to worse, did we not simply step back in? These are all questions worth asking, and questions I’ll be asking myself for the rest of the day – note: I’ll be asking myself. Because as much as I believe in democratic principles in parenting, my parenting is not a democracy. You don’t get a vote. You don’t have to live with the guilt and regret either, so happy days.

I’m not proud of my performance as a parent this morning. I mean, it was definitely in my top-five worst parenting moments ever even before you came along, and by the time you walked away I think I can say that it had raced all the way up to the very top. I hope that makes you feel good. I hope you’re proud of approaching a mother who was just holding it together, and tipping her over the edge.

We made it to school, my son happily skipping in only about five minutes late – scooter in hand – and I said I was sorry and gave him a big hug, and he kissed me and told me he loved me. Maybe there’ll be extra hugs tonight. I’d say most certainly there will be extra hugs tonight – but not because you said so. My relationship with my child has nothing to do with you, stranger, and my hugs are not yours to give away. I know that the job of being a parent comes with a responsibility to provide endless hugs, and that by running out, I failed. I know that the first rule of parenting is never ever to be in a rush, but then life happened, and school, and lunch boxes and unexpected toilet trips and insomnia. I’m a person too, complete with feelings and frustrations and flaws and occasionally very insufficient patience – and I’d like to think that I’m teaching my kids that that’s OK. I guess I’m also teaching them that when someone crosses that line and starts to interfere with your business in a way you’re very much not comfortable with, you have every right to tell them to get lost. It’s kind of ironic when you think about it, isn’t it?

PS. A Freudian analysis of the above would quite possibly look back at my childhood and a moment when my mother threw me out the door into inches-deep snow wearing nothing but moccasins, and my snow joggers after me, in pure frustration. It would suggest, I guess, that I’m acting out trauma from childhood experience. Or, I don’t know, maybe it would simply say that I’m getting what I deserve. Maybe this is it: it’s payback time.

The post To the woman who told me all my child needed was a hug appeared first on LINNEA DUNNE.

August 21, 2017

So you think you were hired on merit? Gender quotas and the perception gap

‘So, I guess you support gender quotas too, then?’

I’m sure I’ll have to fend off heaps of pantsuit accusations for writing this post, but a colleague asked, and I’m not going to turn down the chance to explain why yes, indeed, I do support gender quotas.

I think the thing that makes gender quotas hard for some liberals to stomach is that, in contrast to issues like bodily autonomy and ending violence against women, they don’t seem quite as immediately right and fair. If equality is what we want, surely we should be treating everyone equally?

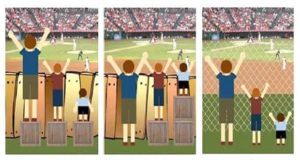

Cue that illustration that’s been doing the rounds lately, explaining how the word ‘equality’ can in and of itself be a tad problematic: if social justice is what we’re after, giving each and every one ‘equal’ treatment won’t get us very far, because we’re all born in very different and in fact unequal circumstances. Instead, we should be focusing on equal opportunity, and to provide that we’re going to have to rely on all kinds of different support systems – including breaking down a whole horde of barriers preventing us from building a truly just society.

I do find it funny how many people look around, shake their heads at the thought of gender quotas and say that, no, we can’t do that because nothing is fairer than merit. We have offices and boardrooms full to the brim of straight, white, middle or upper class men, and yet people talk about merit. Even in environments traditionally dominated by women, we see a load of men at the helm – and they keep talking about merit. What these people are really saying is this: men are simply better at all this stuff. They think all these men have got where they are just because they worked hard.

I hate to burst that bubble (OK, I don’t). Not the one about hard work, that is; I’m sure they all had top marks in school and studied very hard and are paying off a load of student loans and have taken their career oh so very seriously. It’s just a bit smug to think it’s that simple.

Let’s talk about objectivity and non-partisanship. Because of what the world looks like, and because of how women’s experiences are routinely silenced and invisibilised, we have developed a skewed perception of gender equality. As the Geena Davis Institute for Gender in Media found, crowd scenes on screen tend to be made up of about 17% women – and we’ve gotten used to it as the new (old?) normal. Men experiencing said crowd in a room tend to estimate that it consists of about 50/50 men and women. Increase the number of women to 33% and men will say that there are more women than men.

Sady Doyle writes in In These Times that:

“… men “consistently perceive more gender parity” in their workplaces than women do. For example, when asked whether their workplaces recruited the same number of men and women, 72 percent of male managers answered “yes.” Only 42 percent of female managers agreed. And, while there’s a persistent stereotype that women are the more talkative gender, women actually tend to talk less than men in classroom discussions, professional contexts and even romantic relationships; one study found that a mixed-gender group needed to be between 60 and 80 percent female before women and men occupied equal time in the conversation. However, the stereotype would seem to have its roots in that same perception gap : “[In] seminars and debates, when women and men are deliberately given an equal amount of the highly valued talking time, there is often a perception that [women] are getting more than their fair share.”

Our perception is so severely twisted we wouldn’t know merit if it slapped us in the face. Since we perceive women and men differently, we can’t hold them to the same standards, no matter how hard we try. The job description might be the same, but what does ‘forthright’ mean and how do we perceive it in a woman and a man respectively? If we expect of a candidate to demonstrate leadership qualities, can we be sure we won’t find one of them ‘bossy’? You think one candidate talks too much – but does she really? I’m not sure we even know what objectivity and non-partisanship look like anymore. TV3 sure doesn’t, and neither does Newstalk. Academia? Nope.

More explicitly HR-related research is unequivocal, too: so-called ‘resume whitening’ at least doubles job applicants’ chances of being called for an interview, while women are consistently ranked as weaker candidates than men with identical CVs. In addition to such ‘latent biases’ in regards to gender, there’s a cultural bias as people tend to employ candidates they can relate to and understand – future buddies, basically. At the extreme end, we tend to hire people who remind us of ourselves.

Too long; didn’t read: lads hire lads, and male-dominated boards won’t change because women get more qualified and ‘lean in’.

With gender quotas, at best, we get a few women into positions of hiring power, and we start to see change as they begin to hire people who are more or less like themselves and girls grow up to see people other than duplicates of their grandads in positions of power. At worst, these women too carry the biases so ingrained in society and media narratives, for instance in the form of internalised misogyny, that this simply isn’t enough.

A reactionary drop in the ocean? Sure. Gender quotas won’t smash the patriarchy, nor will they undo capitalism. Here’s what else they won’t do: address the injustice.

Back to the illustration. Gender quotas are in the middle, a far-from-perfect image number two, propping up a broken system by making its flaws less ugly, but surviving it – sometimes marginally, other times beautifully. And I don’t like it either. I don’t like hiring by numbers, I don’t like box ticking, and I don’t like focusing on those who have already done so well that they can even begin to think about what that glass ceiling looks like. But until we remove the systemic barrier that is all of the above, all the patriarchal indoctrination and the new normal, it is better than nothing, better than the status quo.

Nobody wants to need those supports – or, as the anti-quotas camp likes to put it, no one wants to be hired because they tick the quota box. But by the same token, I don’t think anyone wants to be hired based on a skewed perception of what they are, or what their competition is not.

What’s that, you’re sure you were hired on merit alone? Really?

The post So you think you were hired on merit? Gender quotas and the perception gap appeared first on LINNEA DUNNE.

June 6, 2017

Infighting on the left and a real left-wing alternative

Oh, the infighting on the left. If only they could get along and get their act together, and maybe they’d achieve something.

In the aftermath of #coponcomrades, and after a couple of years of complete lack of consensus around Corbyn’s Labour leadership in the UK, it is easy to feel like the infighting on the left has become a pet peeve of many, interestingly especially those who aren’t actually that far out on the left. And I’m starting to feel frustrated by it. Not the infighting, that is – but the opinions.

As things stand in Ireland, billionaire business man Denis O’Brien is the owner of Communicorp and significant minority shareholder of INM, the companies that control significant media outlets including the Irish Independent, the Sunday Independent, the Herald, the Irish Daily Star, Newstalk and Today FM. News Corp, of which the Murdoch family controls 39% of the voting rights, owns the Irish Sun and the Irish edition of the Sunday Times. Our government, at the same time, is fighting the European commission’s call for Apple to repay billions in back taxes, while adding new tax breaks to make up for the phasing out of the double Irish tax structure – anything to please the big multinational players.

What I’m saying is this: Ireland is a fan of neoliberal fiscal policy, and its mainstream media isn’t going to be asking any questions.

But what’s that got to do with infighting? Quite a lot, if you ask me.

I had already left London when Jeremy Corbyn, somewhat controversially, took the helm of the UK Labour party, but the divisions were clear: there was no way he’d ever be a successful leader of a Labour party in a country with a first-past-the-post electoral system, centrist Labour voters said. The hard left was told to give in and accept a softer, more liberal leader. In Ireland, their peers are singing to a similar tune, as the left decries the lack of a viable left-of-centre alternative to end the Fianna Fáil-Fine Gael ping-pong game. If only the infighting on the left would stop – then we could all hold hands, laughing all the way to the Dáil.

Except, of course, a conversation like that around #coponcomrades is never going to go mainstream enough to impact on the potential for a real left-wing alternative in Irish parliamentary politics. And sure enough, if we had a Corbyn equivalent, the O’Briens and the Murdochs would fry them long before they became party leader – just like the UK media tried to do.

My problem with the criticism of the infighting on the left is that it’s almost always populist; the idea is that we’ll never make a realistic enough alternative to Varadkar and his crew. We need to get it together and seem like we’re all on the same page; we need to agree on some not-too-leftist policies and bring them to the ballot box – and then we can iron out the details. It’s almost as if people thought that ‘the left’ was this homogenous anti-Varadkar gang, all subscribing to the same politics and the same worldview; as if anyone who doesn’t tick O’Brien’s boxes must be anti-market liberalism enough to be happy to throw just about any other principles under the bus for the chance of a bit of redistribution of wealth.

A republic with a single-transferable-vote system and a neoliberal mainstream media will never make a good breeding ground for new lefty alternatives. The voting system alone is designed to perpetuate status quo in order to favour stability, and a media that plays by the rules of the free market is bound to play into the hands of neoliberal values. Combined, they’re a Fine Gael dream and couldn’t care less about infighting on the left – though given the chance, I’m sure they’d use it if they had to.

If I can’t dance, it’s not my revolution. Give me a left-wing alternative that throws working class women under the bus, and I’ll pass. If it’s not intersectional, it doesn’t matter how proud Robin Hood would be.

The left, in and of itself, is anti-establishment; it feeds on the criticism of the neoliberal status quo, not the waltzing with it. So you say we need to play by the rules of the market to get in the door, before we can change the rules of the game? Fine – who will we sacrifice along the way? How much can we play ball and still call ourselves a lefty alternative?

I know so many people who are burnt out right now, activists who are on a break, who care too deeply to stop – until they’re so broken they have no other choice. People give and give and give, because that’s how important this is.

When you say that we need to stop the infighting, you are inadvertently saying that the details don’t matter, that maybe some minorities can wait. Or, if that’s not your intention, you are blind to the power of the status quo and a media that funds the already rich and drinks pints with those already in power. A left-wing alternative was never going to walk in the front door all suited up, shaking hands with Varadkar. And if it wasn’t willing to take the difficult conversations, it was never a true alternative in the first place.

The post Infighting on the left and a real left-wing alternative appeared first on LINNEA DUNNE.

May 19, 2017

If it’s not your identity, it’s your privilege

It’s funny when a straight, white man denounces the three-word descriptor as unfair because those are not the words he would personally choose to describe himself. Talk about missing the point – or helping to hammer it home. That’s exactly what privilege is: the identities that are so deeply accepted as societal norms that they become invisible. I didn’t grow up introducing myself as a straight, white, middle class person either. Why would I? Nine out of ten of my friends ticked all those boxes too. Woman, though – I describe myself as that on the regular.

People who take issue with identity politics tend not to like the way we use the word ‘privilege’. I’d be happy to use a different word; I just don’t know of one that hits the nail on the head so well. I’m privileged too – in some ways, maybe more privileged than a working-class Dub, even if he happens to be a straight, white man. But this isn’t a privilege competition and I’m not here to pass blame. As Frankie Gaffney points out so well in his anti identity politics piece in the Irish Times, he didn’t choose those attributes – it’s just how he was born.

Think about that for a moment. He didn’t choose it; he was lucky compared to many, but it was nothing more than a luck of the draw. And that of course goes for those who weren’t so lucky as well, which is exactly why we call it privilege – it’s not earned, it’s not chosen, nor is it in and of itself a sign of ignorance or arrogance. It just is.

When Gaffney sets out his vision for a world of equality, he writes: “We should all be subject to the same laws, all have the same opportunities, all have the same rights, all have the same responsibilities…” What he doesn’t want is politics that sets out to divide us. But can’t he see we’re already divided? Can’t he see that plugging that gap between society’s divisions requires a mapping out of the same? If our privileged identities are so normative that we can’t even see them, how are we going to break down the oppressive ideas and prejudices against those who don’t fit within the norm, these ideas we’ve all internalised by virtue of growing up in a divided world? Equality is not about blindly giving everyone the same, like sweets divided into bowls for kids at a birthday party; equality is about looking at the unfair starting points, working to dismantle what caused them and distributing resources accordingly.

Should we talk about suicide rates amongst men, the homelessness crisis and how and why it’s gendered, how toxic masculinity is killing both men and women and how we can destroy it? Of course we should. I want more of that kind of talk, and I have yet to meet a feminist who doesn’t. What I don’t want is for these concerns to grow louder and more frustrated every time a woman talks about women’s rights or a person of colour about racial privilege. We can do both. There’s not a finite space for discussing societal problems and fighting for a more equal world. Keep talking.

Did I ever go hungry? No, not once. I’ll say it again: I’m bathing in privilege. I’m still scared of walking home alone at night; I still panic every month in the days before my period arrives; and I’ve learnt to always wrap my opinions in soft cotton wool, lest I be called out as hysterical – but hey, that’s just being a woman. I’m still regularly reminded of my privilege on an almost daily basis, but while it’s hard, I suck it up. Because this is about inclusive equality for everyone, so screw my hurt feelings.

I could spend my days defending my right as a white middle-class person to use whatever words I choose, regardless of my ignorance around their heritage and the hurt they cause, or I can focus my energy on listening to those who have fallen deep into the cracks of society’s divisions, with the aim of lessening the divides and building bridges. Gaffney has the same choice, and here’s a clue: it’s not the people fighting back against oppression who are to blame for society’s great divides, no matter how uncomfortable they make you feel.

The post If it’s not your identity, it’s your privilege appeared first on LINNEA DUNNE.

May 16, 2017

Police brutality and punching down

I was standing in the airport security queue at Heathrow Airport when a group of middle-aged women started laughing, indiscreetly, at a trans woman just in front of me in the queue; and I wanted to say something, yet I didn’t want to cause a scene, didn’t want to make the experience any worse for the woman in front of me than it already was. Then we approached the security belt and staff started laughing and pointing, even less discreetly than the women had done, and I couldn’t contain the rage. I ended up telling them off; I ended up in tears, shaking. The woman informed me that she was fine – this was her everyday life, after all. She was used to it.

With hindsight, perhaps it wasn’t the security staff that broke me. With hindsight, I was definitely already sad, probably already broken. What broke me was the story of the woman who killed herself, the activist whose mental illness episode ended in police arrest as she wandered the streets of Dublin naked – an arrest that was videoed, shared, watched on Facebook by 130,000 people before, just a few days later, she took her own life.

More than upsetting, frightening and enraging, the behaviour of the gardaí proved a point, proved that she’d never been a real, valued person in their eyes, having grown up in an estate they didn’t touch but sneered at, a world they didn’t care for – one they protected the privileged classes from, despite exclusion being the heart of the problem in the first place. From being ignored to being abused, she was worthless to them. And people are offended when they hear people say that all cops are bastards. That’s what broke me.

All cops aren’t bastards, yet everything they touch turns to muck. Records of millions of imaginary breath tests; false allegations of sexual abuse, leaked personal information, lives ruined. Once entangled in a system of corrupt power relationships, even the most well-intended citizen will struggle to tell right from wrong. But what breaks me is that those who know that indeed all cops aren’t bad are so busy defending them that they refuse to see the abuse by those who are, refuse to see how one thing leads to another, how police brutality is killing working class people, literally.

All cops aren’t bastards – just like #notallmen, indeed #notallmedia. But try to tell the same people that not all travellers trash hotels, that not all muslims are terrorists, and they’ll insist that it’s hard to see the wood for the trees, that when you see it happening more than once it’s hard not to come to expect it. The good and righteous should take responsibility for their tribe, they say. But who takes responsibility for the gardaí when they share footage of a distressed woman at her most vulnerable?

‘I don’t get it,’ some say about transsexuality, as if their ability to empathise and identify with others writes the rules, as if ‘not getting it’ equals forgetting everything they’ve ever known about human decency and thinking it’s OK to point and laugh at a person who is never allowed to feel normal. There are a lot of things to feel sad about in the world right now, but perhaps that’s what’s worst of all: the fact that so many so often will fail to stand up for other people who don’t already have the upper hand, fail to empathise with anyone but those already in power. That so often, people are willing to tar everyone with the same brush as long as they’re already oppressed and powerless, to play along with Varadkar’s game of ratting on those most desperate in society, those already left out. That #notallanything only ever punches down, never up; that it only ever serves to silence.

And that’s what breaks me – that I’m only really feeling this now, protected my entire life by the privilege of boredom. That I’m crying in an airport while the security staff roll their eyes at me and keep on laughing, and the trans woman soldiers on – because this is the world she’s used to.

The post Police brutality and punching down appeared first on LINNEA DUNNE.

April 18, 2017

Why have kids if you don’t want to spend time with them?

A few days ago, I snapped at a friend I haven’t spoken to in years. It was on Facebook, which I guess just makes it less surprising and more pathetic, but anyway, I did*. She put up an article entitled ‘Why have kids if you don’t want to spend time with them?’ and I thought ‘finally a piece that rips that stupid question to threads!’ and clicked on it. But the article did no such thing; it was just another entitled article describing the selfish behaviour of parents who put themselves first sometimes, who want ‘me time’, who don’t cherish every moment with their children enough.

It’s worth talking about the choices we make and how they impact on our children. Actually, it’s crucial that we do. It’s important that we, as a society, have an ongoing conversation about the needs of children and how their many relationships affect them, not least their relationships with their parents. They don’t get a say in this, so we have to take that responsibility. Articles that ask why you’d bother to have kids in the first place if you don’t want to be with them, however, don’t tick that box.

The article in question was published in a Swedish tabloid, so it must be understood in the context of Swedish norms; childcare is heavily subsidised and all children over the age of one have the right to a full-time place in crèche, most of them funded by the local council, with the huge majority of parents working. Workers have a right to a minimum of two consecutive weeks off work, and most white-collar employees take at least a full month off during the summer, with the country almost going into shut-down for two months after Midsummer. This particular article was triggered by a crèche note about planning the summer season, reminding parents of the importance of giving their children a break and spending your holidays with them.

‘All this never-ending talk of me time. I hear it everywhere,’ the writer complained, insisting that the fact that a crèche even needs to remind parents to spend time off with their kids is a sign that our need for ‘me time’ has gone overboard. And I get where she’s coming from; it’s sad that some parents feel that their children are happier and more stimulated in crèche than they are at home, and it sucks that many parents are so exhausted that they’ll consider using their holidays for a break over time with their probably just as exhausted children. What pushes all my buttons is the question: ‘Why have kids if you don’t want to spend time with them?’

I went for a morning stroll by the sea the other day before I started working. I’m lucky that my job allows me to do that, and boy did I need it; it’s been a hectic few months. But it wasn’t without a moment of guilt – because I know how people talk, and I know people like the author of that article. Where were my kids? In childcare, of course. Other times, I’ll go for a run instead of taking a lunch break – again, I’m lucky that way. I could meet a friend for a coffee at 11am and work through my lunch; if I’m really tired and stuck for inspiration, I could even wrap up early, get some fresh air, and pick up work after the kids have gone to bed at night.

Not everyone’s lucky. Many people are stuck in their remote office building even on their breaks, can’t check in on personal messages and social media in work, and can just about leave five minutes early even in exceptional circumstances. When they’re run down and having a bad month, where are they supposed to catch their breath? Compare those who live in the same town as grandparents, old friends and cousins and can easily get a Saturday afternoon to themselves to run errands or hit the gym, to those with no family support at all. No one’s asking parents why they had children in the first place when they leave them with the grandparents for the weekend, do they?

The author of the article is clearly disgusted that some parents occasionally add a few hours to their children’s schedule when they’re not actually working – hours they instead spend cleaning, resting or just enjoying themselves. The children, she argues, are stuck in crèches with overworked staff who don’t have time for the children’s individual needs. Funnily enough, she doesn’t seem to take issue with the children being there on a full-time basis. She doesn’t argue with the fact that parents have full-time jobs. No, it’s when parents stop being productive, when they’re being selfish – that’s when the children come into view. Sure if we’re working, we’re working, right?

In Ireland, the situation is different. Childcare is a costly thing – a ‘second mortgage’, we’ve come to call it – and it’s far from a given that both parents in a two-parent household will work. As there’s no such thing as paid paternity leave, bar the recently introduced two weeks, the by far most common scenario is that mothers stay at home with babies and then choose whether to return to work or not. If they do, they tend to go back much earlier than Swedish mothers – and not always by choice.

Ironically, the ‘why have kids if you don’t want to spend time with them’ question is still a thing, but in Ireland mostly directed at mothers who work. It’s funny, that – isn’t it? Swedish norms allow mothers to work, because working is the done thing and not really deemed selfish, but as soon as they clock out they become greedy if they want to do anything bar being with their kids. In Ireland, because returning to work after having a baby is a new thing, comparatively speaking, that’s what’s seen as a mother’s road to freedom – her little bit of ‘me time’, her being selfish. Why have kids if you’re going to spend all day every day in an office? Unless you’re a man, of course. If you’re a man, who knows why you’d have children at all anyway, other than to make your wife happy.

I thought about the fact that the criticism of parents, or mothers, is the same despite the culturally different norms, and I realised that there is one very clear exception to the rule in both countries. Not once did I ever hear a straight couple asked the why-have-kids question when getting a babysitter for a romantic night out. Everyone agrees that relationships require a bit of effort every now and then; couples need make-up and nice drinks and a change of scenery to keep that spark alive. See, a night with your spouse doesn’t qualify as ‘me time’, no matter how much your kids are being minded by somebody else. A woman isn’t being selfish when she’s out with her man.

‘If you choose to have one or more kids, ‘me time’ isn’t something you can take for granted the first ten years,’ writes the mother-of-two, who works as an account manager for a big IT company and still lives in the town where she grew up. I don’t know how much family and friends she’s got nearby, nor do I know how many struggling single parents she knows, how much her friends talk to her about their post-natal depression or the fact that they regret having kids and can’t wait for the next ten years to pass. ‘Being with my children beats everything else in life,’ she adds. ‘I enjoy every moment they want to be with me.’ She’s one of the good mothers, in case you’d missed her point.

But seriously though: why have kids if you don’t want to spend time with them? To those of you desperate for ‘me time’, who had kids and fear that it might have been a big mistake, those of you who love your children above all else but would kill for a day away just to remember who you are underneath it all, who are stuck in the house and haven’t been able to get out for a drink in years, those who hate your jobs but can’t manage without the salary and love the weekends with the kids but would just like to be really, really selfish and alone for once – there’s the question you should ask yourselves. I hope it helps.

*And here’s where I apologise for snapping and acknowledge that I do that to the people I love and admire all the time, because I suck at keeping my thoughts to myself and think talking stuff through is good and healthy – and, clearly, inspiring.

The post Why have kids if you don’t want to spend time with them? appeared first on LINNEA DUNNE.

January 12, 2017

Down Syndrome, reproductive choices and the need for a social welfare state

On January 2nd, the Irish Times reported that Irish women have been advised to start having babies younger. The contextual hypocrisy aside (think housing crisis, sky-high childcare costs, poorly paid graduate jobs – the list goes on), one aspect of the story jumped out: Dr. Fishel, of a Dublin IVF fertility clinic, said that Down Syndrome occurs in one of 700 pregnancies in women aged 32, while the same figure for women ten years older is one in 67, and 70-80% of a 40-year-old woman’s eggs have a chromosomal abnormality. Why it’s important? Because Irish women aren’t having enough babies to keep society going with our ageing population. We need to keep producing healthy, productive sprogs.

Last weekend, Down Syndrome appeared in the media yet again, as the Citizens’ Assembly met to consider the medical, legal and ethical implications of ante-natal screening and foetal abnormalities. 40 Irish women, they were told, had abortions last year after screening showed that their babies would have Down Syndrome.

The assembly was also informed that no babies with Down Syndrome have been born in the past four years in Iceland, where highly accurate non-invasive screening procedures are standard, and the development in Denmark, where screening routines are similar, is going in the same direction. The point Professor Peter McParland, director of Foetal Maternal Medicine at the National Maternity Hospital, was trying to make was that “science has got way ahead of the ethical discussion”. And we don’t want that, do we?

This is nothing new. I wrote about my thoughts on the situation in Denmark back in 2012, when a Swedish opinion piece posed a question similar to McParland’s: How narrow can the perception of the perfect child get? It’s an interesting and important question from a philosophical point of view, but when asked in the context of the reproductive justice discourse it becomes puzzling at best – not least because monitoring pregnant people’s motivations is tricky. Do you qualify for a termination if there are multiple reasons behind your request, not a diagnosis alone? If you expressed a wish to terminate before you even got the screening results, will your motives seem noble enough? If you’re broke and lonely and depressed and have no one around to help, and the chromosomal abnormality is deemed extremely serious, do we sympathise enough to budge on the moral high ground?

More often than not, the answer is no, because these arguments have little to do with concern and compassion and a great deal to do with religious, dogmatic principles. The more you pick them apart, the more these concerns tend to fall into the ‘slippery slope’ category (‘if they can terminate for this, they’ll soon be terminating for that’), which follows on from the idea that women are both cold-hearted and hysterical at the same time and don’t know what’s best for them; that the right to choose is not absolute, but must be handed down to women on a case-by-case basis. The slope in the analogy leads straight down into an imagined promiscuous hell, where women can engage in sexual pleasures as they please, almost without consequences.

Of course, talking about the kind of society we want to live in is incredibly important – I reiterate this every time it’s time to go out to vote. But is a concern for babies with chromosomal abnormalities and the kind of society we want to live in really, in practical terms, naturally linked to the view that reproductive choice must be restricted, with forced pregnancy and parenthood suddenly being a-ok?

Two weeks, two stories. And the takeaway? We should start early to minimise the risk of Down Syndrome – but if we terminate a pregnancy due to a chromosomal abnormality, we’re ethically compromised. We should want to avoid it – yet struggling to embrace the reality if we fail to avoid it is just not on. The hypocrisy is mind-numbing.

What’s ironic is what these two unrelated news stories have in common. Firstly, neither really has anything to do with Down Syndrome; they just use it, crassly, for the benefit of their own argument. Secondly, they rope in women’s sexuality as a tool to get what they want. The goal of the first news piece is optimal reproduction and an increased birth rate, and Down Syndrome is used to convince women to reproduce as required – whether they want to or not. The goal of the second is continued restrictions on abortion access, and Down Syndrome is used to convince those on the fence that liberalised abortion laws are ethically questionable. Both are straw-man arguments, because the crux here isn’t that women aren’t aware of the risks involved with postponing trying to conceive, or that they view people with Down Syndrome as in any way less human or worthy. Still we keep having babies later, and more advanced screening programmes lead to fewer Down Syndromes babies being born – so why on earth is no one asking why?

The third thing the two stories have in common is the solution (hint: it’s not the policing of women’s bodies). Ask the parent of a severely disabled child what they want. Ask a woman trying to conceive aged 43 what she would have wanted years ago. Support and a solid welfare state would go a long way; the modern individualist mantras we are continuously sold today are likely to receive less praise.

What we need is a shift in attitudes and a hugely increased support system, where you don’t need two degrees and a handful of unpaid internships in the bag before you can get paid work, and an additional ten years of career building before you can buy a house; where you can become a parent and afford to return to work should you want to; where the rental market is regulated, secure and tenant-friendly enough that long-term renting is considered a perfectly good option for a family with kids; where we don’t have to talk about childcare costs as ‘a second mortgage’; where social services are built on social values, not financial measures and market logic; where being a single mother does not automatically equate to being the lowest rung on the ladder of society; where you can become a carer of your much-wanted, disabled child and society is there to get you through. Laws controlling women and making them into vessels for steady population growth just won’t work – nor will fake concern for children with Down Syndrome that does nothing but pit them against the people who love them most.

The post Down Syndrome, reproductive choices and the need for a social welfare state appeared first on LINNEA DUNNE.

January 6, 2017

Normalising hate speech – on John Berger, the Irish Times, and the recontextualisation of meanings

I watched the first episode of Ways of Seeing, the BBC John Berger mini-series from 1972, last night. Explaining how images are given new meanings in different contexts, carrying ideological biases depending on their presentation and contextualisation, Berger ends the episode with a warning: “But remember that I am controlling, and using for my own purposes, the means of reproduction needed for these programmes. The images may be like words – but there is no dialogue yet. You cannot reply to me. […] You receive images and meanings, which are arranged. I hope you will consider what I arrange – but be sceptical of it.”

The alt-right article and glossary* by Nicholas Pell published yesterday in the Irish Times has been called many things – propaganda, a shit storm, an utter disgrace. It is safe to say that readers were sceptical of it, and indeed, when the opinion editor justified the decision to publish the piece by arguing** that the stance of the paper itself has previously been made abundantly clear on its leader pages, Berger’s theses appear highly relevant. In the context of the paper, the words of an alt-right advocate on the opinion pages should not be interpreted as propaganda, the editor’s argument went, but rather as democratic viewpoint airing and an opportunity to face the debate head on. Clearly, readers were not convinced.

We are often fed a hands-off interpretation of our media outlets, told that involvement and meddling equals censoring, that no-platforming is discrimination, and that a laissez faire approach is always the most democratic. After all, the public reads what the public wants; as was pointed out, readers have the ability to make their own minds up. And it’s no coincidence, of course, that a media exposed to market forces adopts the language and logic of the market. It’s perhaps got less to do with consumer satisfaction than it tries to convey – or else the so-called shit storm would have justified the taking down of the original piece and not just the creation of another one in response – but sure enough, the clickbait must have brought home impressive figures for a decent advertising revenue boost, thus justifying the piece in purely financial terms. As readers, we voted with our clicks.

Yet the Irish Times stance in relation to the debacle remains far from unambiguous. The context of the paper as known by the public extends far beyond any position on far-right extremism expressed on the leader pages; for example, a range of articles dubbing both pro-choice and anti-abortion campaigners extreme have been published of late, boasting similar views of these campaigners as must have led to the opinion editor’s using their messages as examples of previously published material deemed just as questionable and contentious as the alt-right glossary. And perhaps this is exactly why I – while gobsmacked by the fact that said glossary was even considered for publication, and while entirely in agreement with others, including the paper’s own columnist Una Mullally, who insist that it was a terrible mistake – still struggle to back up my position with what feels like a reasonably rational argument. Because in the context of Ireland, in a highly conservative, Catholic country, what is there to say that the extreme, shrill pro-abortion brigade won’t be denied a platform next, should a paper like the Irish Times decide to turn away an extremist like Pell? While the difference is crystal clear to me, it clearly is not to the paper.

The bare minimum purpose of the controversial article, it was argued, was to decode the language of the alt-right movement. Not that the racism is ever explicitly labelled as such, and the sexism is allowed to pass by all but unnoticed; in fact, the refusal to label the so-called alt-right sympathisers as fascist, neo-Nazi, sexist, racist, misogynist, white supremacists tells a tale – they’re extreme, a bit like the abortion fanatics, and here they are explaining their funny little extreme views. Enjoy! While the Irish Times seems unwilling to go anywhere near the words describing the true ideologies behind the alt-right movement, it seems to find the expressions and worldview behind it just fine – somewhat extreme, but legitimate all the same.

I think the clue is in the fear of labelling. If the ideology you’re trying to decide whether or not to provide a platform for is one the name of which you wouldn’t touch with a barge pole, it’s probably one you shouldn’t amplify. The reason you shouldn’t publish Pell’s work is that he’s an unapologetic racist neo-Nazi – but no one’s explicitly admitting that, are they? And in failing to label him for what he is, the publishing of his glossary far from decodes the language of his movement – it normalises it. A pro-choicer, a socialist, an alt-righter – the Irish Times might be a tad uncomfortable with all of them, but each to their own, right? If the alt-right guys are everywhere – on Twitter, in the White House, in our biggest dailies – they can’t be that bad.

Lindy West expressed it very well in the Guardian earlier this week when she wrote about her decision to ditch Twitter:

The white supremacist, anti-feminist, isolationist, transphobic “alt-right” movement has been beta-testing its propaganda and intimidation machine on marginalised Twitter communities for years now – how much hate speech will bystanders ignore? When will Twitter intervene and start protecting its users? – and discovered, to its leering delight, that the limit did not exist. No one cared. Twitter abuse was a grand-scale normalisation project, disseminating libel and disinformation, muddying long-held cultural givens such as “racism is bad” and “sexual assault is bad” and “lying is bad” and “authoritarianism is bad”, and ultimately greasing the wheels for Donald Trump’s ascendance to the US presidency.

Lo and behold, our broadsheet print media is next in line.

In the context of an alt-right propaganda leaflet, the views of men like Pell are what they are: highly offensive, incredibly ignorant, but at least more-or-less clearly labelled. I wonder what Berger would have thought about the recontextualisation of these messages as presented in the Irish Times, told as part of the Irish media story, one that boasts about a commitment to provoking strong debate – even if the provocation comes in the form of something a little extreme. Perhaps a word of warning is in order: there is no dialogue yet; you receive meanings, which are arranged. Consider what they arrange – but be sceptical of it.

*I will refrain from linking to it for, I think, obvious reasons.

**As above.

The post Normalising hate speech – on John Berger, the Irish Times, and the recontextualisation of meanings appeared first on LINNEA DUNNE.

Linnea Dunne's Blog

- Linnea Dunne's profile

- 38 followers