John Draper's Blog: A Danger to God Himself

July 24, 2016

Emmett’s Day Out

Emmett awoke early to find himself invisible so he figured he’d go to the girls’ college upstate. The prospect filled him with animal lust as he kicked his pajamas to the corner of his containment unit. A simple matter, he reasoned, to quit the grounds, being invisible and all. Some rats, some peckerheads, tipped off security, though. How else to explain inviso-scanners? In short order, Emmett found himself in the chief nurse’s office and from thence back into his unit. Peckerheads! Around about noon, his visibility restored, his humor improved, he was drawn cafeteria-ward by the smell of hot lunch.

Emmett awoke early to find himself invisible so he figured he’d go to the girls’ college upstate. The prospect filled him with animal lust as he kicked his pajamas to the corner of his containment unit. A simple matter, he reasoned, to quit the grounds, being invisible and all. Some rats, some peckerheads, tipped off security, though. How else to explain inviso-scanners? In short order, Emmett found himself in the chief nurse’s office and from thence back into his unit. Peckerheads! Around about noon, his visibility restored, his humor improved, he was drawn cafeteria-ward by the smell of hot lunch.

The post Emmett’s Day Out appeared first on A Danger to God Himself.

June 20, 2016

Learning to be moral, Part 5

In my last post, I began talking about the role scripture can play in our moral instruction. I explained that scripture can remind us of what we’ve already learned on our own about right versus wrong. Said differently, our ever-developing moral sense helps us discern the moral teachings of scripture. It’s not the other way around. Scripture doesn’t shape our moral sense. Thank God—because a lot of scripture is morally dubious.

In my last post, I began talking about the role scripture can play in our moral instruction. I explained that scripture can remind us of what we’ve already learned on our own about right versus wrong. Said differently, our ever-developing moral sense helps us discern the moral teachings of scripture. It’s not the other way around. Scripture doesn’t shape our moral sense. Thank God—because a lot of scripture is morally dubious.

At best, the Bible’s a mixed bag. The Bible presents different ideas about God and His inclinations/preferences—reflecting the different cultures and circumstances in which the various biblical writers found themselves. Some of those depictions of God are worthy. Some aren’t.

For example, Israel didn’t adopt a monotheistic view of the universe until after the Babylonian Exile. You see this reflected in the Torah. Before the Babylonian Exile, the Israelites viewed Yahweh as just one of the many gods in the near east.

You doubt me? Take a second look at the first commandment. “I am Yahweh your God, who brought you forth from the land of Egypt, out from the house of slavery; you shall have no other gods in my presence” (Exod 20:2). Notice what it does not say: “I am Yahweh your God, who brought you forth from the land of Egypt, out from the house of slavery; you shall not worship false gods, but only me, the one true God.”

Again and again in the Torah, God makes big deal of how He is superior to the other gods. Think about it. Why would it be a big deal for Yahweh to be superior to false gods? Anybody can be better than nobody. Next to nobody, Bob Dylan is a great singer. No, the text is clearly saying Yahweh is just one of many valid deities the Israelites could choose from.

Anyway, I’m not here to pound on polytheistic religions, although I think they are mistaken. If God exists, He is One—without parts and utterly simple. Imagine the chaos if there were multiple gods—one saying the Law of Gravity makes you fall down and another saying the Law of Gravity is bollocks and you’re liable to ascend into the ozone in your cowboy pajamas when you go out for the morning paper.

So . . . what was I talking about? Oh yeah, the Bible’s differing views of God. I’m not here to trash polytheism per se. What I’m criticizing is the pathology embedded in the ancient Israelites’ polytheism. In the ancient near east, each nation had its own patron God and each was pitted against the others. Each God fought for His or Her people in exchange for their unconditional allegiance. If your nation got its butt kicked by another nation, it was because their God kicked your God’s butt.

It was a tribal view of the world—an us against them view of the world.

You see this worldview clearly advocated in the first five books of the Bible. Of course God commanded the Israelites to slaughter every man, woman, and child in Canaan. They deserved it, pagan malefactors.

That said, scriptures like this can still be of use to us. The portions of scripture that paint an unfitting portrait of God and His preferences need to be retained in our liturgies as cautionary examples. They need to be anathematized. (There. I did it. I used the word anathematized in a post.)

These texts remind us not to be too quick to assume we know God’s will—not to be so sure we’re God’s Chosen People. They remind us that we have room to grow. They remind us that we can learn from those we consider “other.” In fact, the essence of wisdom is to put ourselves into the other’s shoes.

We figure out how to live morally on our own. We don’t just blindly follow scripture. When all’s said and done, most scripture performs a descriptive function rather than a prescriptive function. In other words, the text tells you how the author was thinking/acting when he wrote the text—rather than how you should live now. Sometimes the insights from the ancient author are spot on—which is what you would expect from any human work. Other times, it’s just ancient nonsense.

So stay on your toes.

Note: I am indebted to Thomas Stark’s jarring book, The Human Faces of God: What Scripture Reveals When It Gets God Wrong (And Why Inerrancy Tries to Hide It, for many of the ideas in this post.

Did you like this blog post? Why not share it with friends? See social media icons below.

Also, you can subscribe to the blog by signing up on the home page sidebar.

The post Learning to be moral, Part 5 appeared first on A Danger to God Himself.

June 14, 2016

Learning to be moral – Part 4

In Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3, I asserted that morality is discovered by humans, not revealed by God. Specifically, religious folks say the superstructure of morality is erected by God in scripture. I think that’s not the case. But I think we’re stuck with the Bible. It’s too embedded in our culture. The Bible influences believers and nonbelievers alike.

In Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3, I asserted that morality is discovered by humans, not revealed by God. Specifically, religious folks say the superstructure of morality is erected by God in scripture. I think that’s not the case. But I think we’re stuck with the Bible. It’s too embedded in our culture. The Bible influences believers and nonbelievers alike.

That being the case, it behooves us to use scripture wisely.

There is truth in scripture. But we—not God—put it there. Scripture plays two roles. One, it reminds us of what we’ve already figured out on our own. Two, by providing us inadequate descriptions of the character of God, scripture provides a picture of what not to do.

This post will look the first of those two propositions, that all scripture does is remind us of what we’ve already worked out on our own. Said differently, God doesn’t reveal His moral will for us through scripture—any more than He does with any literary work of human hands. What we have in scripture is the word of man—for good and for ill.

For example, we know the noblest parts of Jesus’ teaching are true—and there a scattering of Jesus’ teachings that are ignoble—because they resonate with our humanity.

Take the Good Samaritan.

Everyone knows the story. Jesus’ parable flowed out of a discussion he had with someone about “how to inherit eternal life.” Jesus asked, “What Does the Law Say?” The man answered that the Law teaches one must first love one’s God and then love one’s neighbor. “But who’s my neighbor?” the guy continued, wanting—scripture tells us—to justify his hard-heartedness.

So Jesus tells the story of this guy who was robbed and beaten en route to Jericho. A priest encountered the unfortunate man lying wounded in the ditch, as did a Levite, both respected religious leaders, and they passed him by. In fact, they even moved to the other side of road.

Then a Samaritan happened by—a hated Samaritan—and he took pity on the man, tending to his injuries, taking him to an inn, and paying for his continued care.

Jesus asks, “Which one of the three men who happened upon the road was a neighbor to the beaten man?”

“The one who had mercy on him,” the man said.

“Go and do likewise,” Jesus concluded.

At first blush, Jesus comes across as some sort a moral savant. But Jesus just framed his response in terms of what the law already said. Jesus was no moral innovator. He was all about obeying the Law. “Truly I tell you, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished.” He was a real prickly pear when it came to obeying the law.

In other words, what Jesus said was common knowledge. If that common knowledge had become uncommon, it was because we had suppressed it. It’s so much easier to find villains to blame than to see everyone as our neighbor. What Jesus did was show this man what he knew to be true in his deepest self. I mean, it’s not like Jesus revealed a new primary color or some such thing. The man didn’t say, “I never would have thought of that, not in a million years!” Instead, he averted his eyes, shamefaced at what a sinner he’d become.

Jesus’ words rang true.

So it goes with the worthwhile portions of scripture. Believers talk about “being cut to the quick” by a passage from the Bible. In those cases, scripture brought to mind the lessons we’d already learned. That’s why so many “aha” experiences with scripture are accompanied with repentance. The scripture tells the believer to get back on the Narrow Way. The value of biblical truth is that it’s the same thing over and over again until we get it through our thick skulls.

Any other human literary work could fulfill the same role. If you doubt that, attend a meeting of a local book club and see the revelations people draw from current bestsellers. More lessons have been drawn from scripture because the words have been pored over for centuries. We’ve polished the words so as to reveal new facets of truth. In fact, sometimes we surprise ourselves—humans are clever.

That’s not to say that everything in scripture is laudatory. Far from it. There’s plenty of dross peddled as the word of God. I will turn to those passages in my next post.

Did you like this blog post? Why not share it with friends? See social media icons below.

Also, you can subscribe to the blog by signing up on the home page sidebar.

The post Learning to be moral – Part 4 appeared first on A Danger to God Himself.

June 8, 2016

Learning to be moral, Part 3

In Part 1 and Part 2, I introduced my premise that morality is discovered by humans, not revealed by God—in particular, not revealed through scripture.

In Part 1 and Part 2, I introduced my premise that morality is discovered by humans, not revealed by God—in particular, not revealed through scripture.

Now, to that Still, Small Voice: personal revelation independent of scripture. Religions allow some latitude for personal revelation—but always within the boundaries of scripture. That is, God would never tell you to do something that He had revealed in His written word to be wrong. You don’t need to wrestle in prayer to determine whether it’s right to jimmy open your neighbor’s marmalade safe. Just put away the crowbar and read your bloody Bible.

What happens is that religious folks use scripture for the Big Questions and leave the mundane matters of living day-to-day life to personal revelation—whom to marry, how to cut our hair, whom to vote for, where to hide your marmalade.

But we all know that God doesn’t speak to us, even on mundane matters. C’mon, be honest. When we rely on personal revelation to decide whom to marry, etc., we’re really just saying that it feels right—not that God actually told us something. How many times when I was Christian did I hear other believers say they were certain they were on God’s predestined path because they just felt “a peace about it”?

However, when the stakes are really high—when it really matters if you’re right or wrong (when, say, you’re deciding whether to snip the red or blue wire going into the bomb)—even this “peace” isn’t good enough. It doesn’t provide us the specifics we need. “Where are you, Oh Lord!” they cry. “Why won’t you speak to me?”

That’s what I’m saying.

A cautionary tale from Planet Mormon

I’m reminded of the story of Spencer Kimball, onetime prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. As such, Kimball was God’s mouthpiece—a “special witness of Christ” who was said to converse with the savior as one would talk to one’s shift supervisor at the cranberry plant—amiably but never so amiably as to be anything but obsequious. (Kimball probably laughed too hard at Jesus’ jokes trying to make a good impression, get a leg up. A sober glance from Christ would tell Kimball if he was getting too familiar.) Mormons are very proud that they are a church that rests on Modern-Day Revelation. God still speaks! To Mormons!

How could that not be the case in a religion that was founded by a guy who said he found golden plates from God buried in the hard-packed earth of upstate New York? Modern-day revelation. That’s their shtick. Funny thing, though: The revelations kind of dried up after old Joe Smith was gunned down. In fact, pretty much the only Thus Sayeth The Lord revelations that have surfaced after Brigham Young (who snatched the mantle of prophet from the bullet-ridden body of Smith) have been to reverse revelations from Smith and Young.

First, the church was under tremendous pressure from the federal government to renounce polygamy, and it finally caved, releasing the so-called Manifesto in 1890 swearing off the practice of celestial marriage. (At least on earth, for now. Polygamy is still practiced in heaven. In fact, Heavenly Father has a whole bevy of Godwomen. And like any male who finds himself in such a pickle, He copulates nonstop.)

Then, in 1978, the church capitulated again to the federal government—this time for its insistence that black men couldn’t hold the priesthood. I won’t bore you with Mormon doctrine other than to say that this meant black folks couldn’t get into heaven. By the middle of the 20th century, this sounded positively benighted to non-Mormons. Not surprisingly, Jimmy Carter was threatening to take away the church’s tax-exempt protection—and he didn’t get angry too easily. But the priesthood ban was doctrine.

You can see the pinch this put on Kimball, the prophet at the time.

How could he reverse the doctrine without saying the past prophets were wrong? A prophet can’t be wrong, can he? On top of this, it seems that Kimball was personally troubled by the priesthood ban, as well he should be, drawing breath during the second half of the Twentieth Century as he was. Kimball prayed and prayed for Heavenly Father to show him a way out of this pinch.

Nothing. And, remember, this is the prophet we’re talking about. He talks to Christ, according to the Party Line. (The Party Line doesn’t mention all that stuff about Jesus being Kimball’s supervisor at the cranberry plant and such. I just made that up to be clever.)

Finally, at his wit’s end, Kimball struck a bargain with God. Kimball decided that he would reverse the priesthood ban—unless Heavenly Father intervened and told him not to. God was predictably silent, so the church reversed more than 150 years of practice. God’s One True Church decided to treat black men with dignity and fairness 14 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

Halleluiah.

Why couldn’t Kimball just come before the faithful and say, “Look, folks, I just don’t hear Heavenly Father on this one. I know I’m the prophet and all, but I just don’t feel it. If you ask me, I think we should stop this silly priesthood ban. Isn’t that good enough?”

Because religions don’t do that kind of thing. They’ve fully bought into the myth that God speaks plainly to us.

My point is, why not just give up the pretense that God reveals His moral will to us—through scripture or through our intuition? Let’s accept responsibility for our moral development. Let’s admit when we’re boneheaded. We will find the answers we need by ourselves.

Did you like this blog post? Why not share it with friends? See social media icons below.

Also, you can subscribe to the blog by signing up on the home page sidebar.

Photo: Shiva Praying by Tom Maisey CC BY 2.0

The post Learning to be moral, Part 3 appeared first on A Danger to God Himself.

June 4, 2016

Learning to be moral, Part 2

In Part 1, I introduced the idea that morality is discovered by humans bit by bit over the slow roll of the centuries.

In Part 1, I introduced the idea that morality is discovered by humans bit by bit over the slow roll of the centuries.

Of course, that’s not what religious folks believe. They say we know the difference between right and wrong because God tells us. Their idea is that the bulk of morality—the Law of Moses—was revealed by God all at once, right around the invention of barbecue, as best as I can tell. At least that’s what the fundamentalists insist. Evangelicals won’t quibble about specific dates other than to venture that morality was first revealed by God in a megadose in the Olden Days, more or less. We call that megadose scripture. After that, God adds the filigree to our moral code—the mundane daily decisions about right versus wrong—through personal revelation, also known as The Still, Small Voice.

That’s The System. That’s where morals come from. This post and the next consist of a critique of that system. Long story short, we like to believe that God actually reveals His moral will to us, but the truth is in both cases—scripture and personal revelation—that we’re just talking to ourselves.

First, scripture.

Did the Bible drop from the sky?

It’s not as miraculously clear-cut as the fundamentalists would have us believe. They talk like the Bible just dropped from the sky, fully annotated and leather-bound. Actually, they know that scripture was written by men, but it might as well have dropped from the heavens. To them, the humans were just conduits—stenographers.

The premise is problematic. First off, in our hearts we know that God doesn’t possess people in that way, taking over their free will and precluding the various boners to which we are prone. Inspiration, if there is such a thing, is much more subtle. Imprecise. Big-picture stuff maybe, but not schematics of the plan. Even the most hair-shirted fundamentalists would have to eventually admit—after you applied the thumbscrews—that God acts vaguely in their lives. Opaquely. In fact, if fundamentalists hear anyone claim to know God’s will too specifically, they will think someone is trying to con them—or that people who claim such things are off their rocker.

And that’s the actual authorship of scripture. Someone had to choose which of the “inspired” writings were to become scripture. Humans, fallible humans with ancient worldviews, had to make those decisions.

Ardent Catholics are quick to point out the fallacy of the Protestant notion of Sola Scriptura—that all authority rests in the Bible. The reality is that the Bible is authoritative because the church said so. In other words, the authority of the Bible rests in the authority of the church. As noted before, the Bible didn’t just fall out of the sky.

So, as harebrained as it sounds, humans wrote and canonized scripture—the same people who made Kim Kardashian famous. So, in effect, what religious folks are really saying is, “Well, God doesn’t speak to me plainly, but He did to the people wrote scripture and catalogued it.” That, plainly, is a statement of faith—highly dubious on its face, knowing what we know about how God speaks to humans.

Through a glass darkly

But it doesn’t end there. The Bible doesn’t interpret itself.

Words are malleable, which makes literature so wondrous. Everyone gets something different from a given work, which led to the invention of the book club and has been the cause of no end of bar fights. Any given word means one thing you, quite another perhaps to whoever’s sitting on the stool next to you.

Picture the fine stream of inspiration entering the mind of the Apostle Paul, precise and explicit. That same stream of inspiration then gets sprayed all over the landscape when it goes from the page to your brain. If God can constrain one human brain to write the words of a biblical book, why can’t He constrain the minds of everyone reading the book? Said differently, what’s the point of making sure the biblical author got your ideas just right if that book’s teachings will get splayed into a thousand different interpretations? If a biblical passage can mean anything, it means nothing.

Certainly God knows this. He is God, after all. So why did He choose to speak through scripture? Well, He didn’t choose it. We chose it for Him. Frankly, we panicked. We weren’t hearing from God, so we created scripture. But it didn’t really clear things up, did it?

In the end, scripture is a cheat. It’s a shortcut we created to avoid doing the end hard work of figuring out on our own how to live. Our mistake is in assuming that God is overly eager to tell us what He thinks. Truth is, He’s perfectly happy just watching things and nudging them along now and then—to the extent He nudges.

This is on us.

Did you like this blog post? Why not share it with friends? See social media icons below.

Also, you can subscribe to the blog by signing up on the home page sidebar.

Photo: On Legality and morality by Quinn Dombrowski CC BY-SA 2.0

The post Learning to be moral, Part 2 appeared first on A Danger to God Himself.

May 29, 2016

Learning to be moral, Part 1

There’s a great episode on The Simpsons that opens on the scene when Moses descends to the foot of Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments. Homer the Thief is chatting in a friendly, nonjudgmental manner with Hezron the Carver of Graven Images and Zohar the Adulterer, when Moses emerges from around a rock.

There’s a great episode on The Simpsons that opens on the scene when Moses descends to the foot of Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments. Homer the Thief is chatting in a friendly, nonjudgmental manner with Hezron the Carver of Graven Images and Zohar the Adulterer, when Moses emerges from around a rock.

“The Lord has handed down to us Ten Commandments by which to live,” Moses announces. “I will now read them in no particular order: Thou shalt not make any graven images!”

Hezron the Carver of Graven Images throws down his chisel angrily. “Oh my God!” he says.

Moses continues: Thou shalt not commit adultery!

Zohar the Adulterer looks down sadly. “Ah well,” he says, “looks like the party’s over.”

And Homer the Thief is loving all this, reveling in his friends’ misfortune. “Hey, Moses,” he chuckles, “keep ’em coming!”

To which Moses announces: Thou shalt not steal!

And we all know what Homer the Thief says next: “D’oh!”

Processed morality

Like all effective satire, the scene from The Simpsons works because it pokes fun at humanity’s solemn absurdities. Do we really think the ancient Israelites didn’t know the difference between right and wrong before the Ten Commandments showed up? Conservative Christians would have us believe so. It takes that lovable oaf Homer Simpson to show us just how silly that notion is.

The truth is much more nuanced, as is the case with reality, God love it. That is, we’re learning to distinguish right from wrong. It’s a process. Everything in the universe is a process.

I’m not saying that morality is something we invent—as if Do Not Murder could just as easily have been Do Not Macramé.

Nor am I saying that morality is just what’s evolutionarily advantageous. I’ll admit that much of what we consider moral is good for the perpetuation of the species. However, there’s a lot that’s triumphantly moral that evolution can’t explain—for example, jumping into a freezing river to save a stranger.

What I’m saying is that we discover morality over time—reveal it to ourselves bit by bit—the way we uncover the laws of physics, for example. Like physics, morality is hardwired into the universe/reality. Murder is wrong simply because it’s wrong. An object at rest tends to stay at rest. You’ve no choice but to play by the rules.

In other words, we don’t need God in order to be moral.

Mistakes get made

Just as God doesn’t meddle in our intellectual grasp of the universe—say, stuffing the secrets of General Relativity into Albert Einstein’s fortune cookie—He also doesn’t tip His hand when it comes to the superstructure of morality. He just waits for us to figure it all out—morality, mathematics, medicine, macramé. The whole Magilla. Consequently, mistakes get made. The ancient Israelites stone their children for disobedience. Ridiculously elaborate flying machines careen hopefully into barns. Blood gets let. Countless innocents get burned at the stake. And schoolchild after schoolchild in preindustrial America hands in wildly inaccurate dioramas of the known solar system.

No argument. It’s a messy way to go about managing reality.

Not that God’s unconcerned, though it can look like that from our perspective. He’s not unconcerned. Just uninvolved—maddeningly, mind-bogglingly patient. All is process—and the processes God uses (to the extent He actually uses them) are . . . inexact. The other day on Facebook, I watched a computer simulation of how in 5 billion years, the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy are going to collide into one another, shredding each other to dazzling, vast parabolas of gas and dust and bright lights. The result will be a new galaxy of raw possibilities. Milkdromeda! It’s going to be rough, though, on any earthlings who are around when that happens—if the expanding sun hasn’t already swallowed us whole.

You can’t blame the fundamentalists, I suppose, for insisting on a literal six days of orderly creation. It’s so much more comforting. New species materializing out of thin air rather than enduring eons of suffering and malformations. The ground beneath our feet fixed and firm, not prone to cataclysmic thrusts of tectonic plates. A veritable storybook scene. Like I said, you can’t blame the fundamentalists.

Likewise, the idea that we have to hammer out on our lonesome how to lead moral lives makes us very uncomfortable. The reality is that we must wrestle with moral dilemmas in order to achieve new moral insights. That’s hard work. We want morality fixed—from the mouth of God—as soon as possible. Probably comes from our moms lecturing us about our disordered bedrooms. (“It looks like a bomb went off in here!”) So we look around and we see our dirty underwear and comic books all over the floor, and we panic. We rush to codify our moral discoveries, sometimes before they’re fully formed. So what we insist is the truth is sometimes the truth only partially, or the truth misapprehended.

Sometimes we get it right from the get-go—for example, Love Thy Enemy. Other times we prop up systemic injustice. For example, the ancient Israelites said homosexuality turned God’s stomach simply because that was The Way Things Have Always Been. Truth is, they found homosexuality distasteful, so they arrived at God’s opinion for Him. (Imagine the alternative: They had been casually engaging in man-on-man love until shown the error of their ways by the Voice of God a la Homer the Thief.) Rather than set a moral agenda, the Law of Moses codified the status quo, in large part. Sometimes that was fine. Other times not so much. Messes got made.

We needn’t panic. We’ll uncover the truth of morality by and by, as Andromeda and the Milky Way inch toward each other like a bashful twosome at a school dance. It will be a struggle. Whether or not we admit it, we all know that’s the case. In fact, if someone says they know God’s will too specifically, we think they’re crazy or trying to con us. Even the most uptight fundamentalist will have to admit that God is inscrutable. To insist on easy answers, as the fundamentalists do, is to abdicate our responsibility. Our duty. From God. Our duty to grow as moral beings. Once again, it’s damn hard work, fumbling about in the near dark as we are. We’re liable to knock our shins against the furniture.

Look at the bright side: We’re progressing, becoming more moral. And it’s going to get easier and easier to progress. That is, as we become more moral, we become less pig-headed, one would hope. And as we become less pig-headed, we’re more likely to see the error of our ways sooner—admit we’re wrong—and repent of our immoral behaviors. No way to avoid the messiness. But we can at least keep the mess to a minimum.

The post Learning to be moral, Part 1 appeared first on A Danger to God Himself.

April 25, 2016

How the Internet is killing religion – Part 2

In my last post, I said that the Internet is killing religion because of the profusion of information critical of the church. It works, whichever church is church to you. I went on to say that the church reeling most from the Internet was the Mormon Church, particularly because it had a paper trail not found in other monotheistic religions. You can fact-check the Mormon Church on the Internet, I said.

Now I want to move on to the most telling reason the Internet is killing religion—starting with the Mormon Church. The Internet isn’t just about information. It’s about connections. We’ve found truth doesn’t come from On High. It comes from the network.

Here’s how it used to work, pre-Internet:

You were some religion, probably because you were raised to be part of that religion. (For example, the Pew Survey found that Islam is the world’s fastest-growing religion, not because more people are converting to Islam but rather because Muslims have more babies than other religious folks. That means you’re going to have more and more children growing up with the default presumption that they’re Muslims.) And you encountered doubt, as religious folks will, surrounded by swirling enigma, as they find themselves to be. If you were lucky enough to have a fellow parishioner you could let down your happy mask with, you sought him out and you confessed your doubts. More than likely, you got one or more of these reactions:

Some things we’ll never understand until we get to heaven. His ways aren’t our ways.

I will pray for you.

You should pray and read your scriptures more.

Do you have some sin to confess?

Can I pray for you right now? (C’mon, we’ll go over to this corner where no one will see us.)

And then you walk away, shrug your shoulders, lay aside your cognitive dissonance, and get on with the chore of living. His ways aren’t our ways.

The Internet has changed all that. On the Internet, one thing leads to another. Online, you can express a doubt anonymously. You find countless people who experienced the same doubt you struggled with, persevered through their cognitive dissonance, and then came to an unorthodox answer. Some of them became ex-Mormons or ex-Christians or ex-Catholics or whatever.

Others became New Order Mormons or Progressive Christians or Liberal Muslims.

Yet others ash-canned the whole idea of God, usually not without a lot of huffing and puffing and kicking about of furniture.

Whichever, soon enough, you find you resonate with some of them. You find these people are as decent and well meaning as anyone in your congregation. You see they all have the same experience of the divine that you do—that is, a vague sense of peace and a bemused resignation that God Works In Mysterious Ways. All of them grow vertiginous upon considering the vastness of creation and our utter insignificance. Even atheists. (Between 2007 and 2014, the percentage of atheists who said they felt a deep sense of wonder about the universe on a weekly basis rose a full 17 points, from 37 percent to 54 percent.)

Finally, you see no religion is better than any other religion at producing good humans. We’re all just doing the best we can. No religion really works. Neither does atheism.

Suddenly, you realize how confining the four walls of your local congregation were.

You realize we can’t know the truth—and know that we know it. I mean, sure, some of us may have stumbled on to the Ultimate Truth. It’s about as likely as an army of chimps pounding out Hamlet, I suppose. But we won’t be able to prove it—beyond insisting that we feel really, really sure. Really.

Face it. We’re stuck in a universe of uncertainty, and the best way to navigate our way is not through dogma but by connecting with one another and learning from one another’s apprehensions of the Grand Mystery. That’s what the Internet does. That and porn.

We learn the best we can do is piece together whatever it is we choose to believe by taking pieces from the best of what we learn from the people in our network.

The point is, we don’t have to take the church’s word on anything anymore.

Churches are going to get out of the Telling You The Truth business. The transmogrified religions that survive the Internet age will be religions devoted to mystery, religions devoted to not knowing. We will see a flattening of traditional hierarchies, as it’s foolish to think anyone has a more direct line to God than anyone else. There will be more and more diversity, more and more openness, less credal exactitude. People’s religious affiliations will be more fluid.

This idea rankles orthodox folks. They think dogma is what is most important—because it was “revealed” by God. “Without correct doctrine,” they say, “you could just believe whatever you want.”

Exactly. I mean, if God was so concerned we believe a certain set of facts about Himself, He could have been a hell of a lot plainer.

But He wasn’t, so we’re left with mystery.

And really, it’s mystery that deserves worship, isn’t it? Something we have figured out . . . well, we have it figured out. Move on. But mystery . . . Mystery stirs us at our core.

The new religion is coming. Get ready.

Photo: Network by Rosmarie Voegtli CC BY 2.0

Did you like this blog post? Why not share it with friends?

See social media icons below.

Also, you can subscribe to the blog by signing up on the sidebar.

The post How the Internet is killing religion – Part 2 appeared first on A Danger to God Himself.

April 18, 2016

How the Internet is killing religion — Part 1

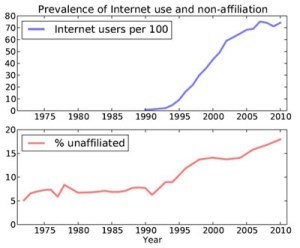

This chart comes from a study by Allen Downey, a computer scientist at the Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts. The two charts show the correlation between the rise in the use of the Internet (the blue line on the top) and the percentage of Americans who say they have no religious affiliation. As you can see, as more and more people use the Internet, more and more people have become less religious. Using data from the University of Chicago, Downey determined that the biggest influence on religious affiliation is religious upbringing. That is, people tend to believe what they were raised to believe. Similarly, college-level education correlates with the drop in religious affiliation. That is, people who go to college are less likely to be religious.

Damn you to hell, higher learning!

Here’s the kicker: Downey went on to say that 25 percent of the drop in religious affiliation can be correlated with the increase in Internet use.

Acknowledging that “correlation does not imply causation,” Downey goes on to say it’s a reasonable conclusion to say that Internet use decreases the chance of religious affiliation.

I think he’s right. The Internet is killing religion—starting with the Mormon Church. The others will follow in course.

The reason’s plain. Religions that insist on “right belief” rely on a closed information system. The power structure must have some level of control over the information the faithful receive.

The Internet has broken that closed information system.

So religion will be done in by its Enemy of Old. No, not Satan. Knowledge. (For all I know, Satan’s religious.) The church has always resisted the advance of knowledge. Consider Copernicus. This time, though, knowledge really has religion on the ropes, and I don’t think it’s going to survive. What will take its place? I will give my thoughts in part 2 of this post.

Right now, let’s pick on the Mormons. As I said, they’ll be the first to fold.

I mean, really, they were asking for it. At first blush, their doctrine is so harebrained. But from Day One, they’ve been insistent they are The One True Church. And from Day One, which—remember—was only 186 years ago, people have been pointing out the farces and fallacies in what they’ve preached. The Latter day-Saints’ response has always been some form of “I don’t care about your facts; I know it’s true.”

Like I said, they were asking for it.

Now there was nothing new about churches setting themselves up as The One True Church, but the difference is that for most of the major religions—I’ll argue in a bit that Mormonism is actually not that major of a religion—their founding events are obscured by the mists of time. Did Jesus really rise from the dead? Who’s to say?

Meanwhile, the Mormon Church has a paper trail. We can fact check Mormonism. That’s what you get when you found a religion after the invention of the printing press. Something’s going to come back and bite you in the butt.

Consider the case of the Book of Abraham, one of Mormonism’s sacred texts. Joseph Smith translated the book from some papyrus he purchased, along with two mummified former Egyptians, from a traveling salesman in 1835, saying they were scratched out by the hand of Abraham himself while in was in ancient Egypt. None of Smith’s followers blinked when he unveiled the book’s revelations that God lives on a planet near a star called Kolob—why would a star have a name?—and that He parades around in a body of flesh and bone, just like you and me. Check it out: God could sport an erection. God could be influenced. Think of the cosmic implications. See what I mean by harebrained?

There’s more. This God, as hopelessly prone to hard-ons as you or me, used to be a regular guy, on another planet somewhere. He advanced to godhood by following the dictums of Mormonism. Then once he became a God, he was given his own planet. Of course. From this base of operations, his job, into eternity, is to produce “spirit children” with his polygamous godwives. These spirit children are sent down into bodies on earth to see if they can live righteously enough to become gods and earn their own planets and their own bevy of godwives and produce their own spirit children, who will be sent down to other planets, where they will be given the chance to advance to godhood and keep the whole system chugging along. It never ends. Fiction is stranger than truth. (You can tell this was a religion fabricated by a horny male. The men get to spend eternity having sex, and the women get to spend eternity being pregnant.)

Unbelievers pointed out how inane this whole thing sounded, but Smith and his cronies were able to change the subject. After all, no one knew how to read Egyptian hieroglyphics, so who could gainsay Smith’s harebrained assertions?

Besides, people wanted to believe.

After Smith’s death at the hands of righteously indignant townsfolk, the scrolls got passed around until they were lost from history and assumed destroyed. However, they resurfaced in 1966 in the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. By 1966, of course, Egyptology had come a long way and Egyptologists all over the country had the expertise to decipher their meaning.

I’ll just put it bluntly. Brace yourselves, Mormons—as if there are still Mormons with us at this point. Smith’s translation of the scrolls couldn’t possibly be less correct. The scrolls date from the first century AD (some 2,000 years after Abraham’s time) and contain pretty standard Egyptian funerary texts. They were placed with the mummies to help usher the erstwhile Egyptians into the hereafter—a hall pass for heaven, if you will.

Finally, reluctantly, the Mormon Church responded, publishing a series of anonymously penned “essays” on their official website. The essays only muddied the waters. (For example, they quibbled over what Smith meant when he said he had “translated” the papyrus. Perhaps the papyrus just acted as a mnemonic device to inspire him. That’s “translation,” isn’t it?) What church members needed was the church coming out and saying, “OK, you caught us with our knickers at our knees! Can we move ahead together somehow and work this all out?” (One could sense the church’s desperation in these essays. They even pulled out Smith’s seer stone and offered a ham-handed explanation. This was the seer stone, it turns out, that he actually used to translate the Book of Mormon, sticking the stone in a hat and then shoving his face in the hat so he could see each successive word radiate out from the stone like a neon advertisement for shoe polish. The alleged golden plates? They were in another room, or out in the woods, hidden from prying eyes, which makes an unbiased observer wonder, “Why in the hell did he need the plates in the first place if he was just going to stick his head in a hat like a dope?” I must mention: This was the very same seer stone Smith used to defraud local villagers, saying he could use it—sticking it in a hat and sticking his head in the hat—to find buried treasure on their property. The mimeographed docket from the court case where old Smith was called to account as a “glass looker”—just months before he was to discover the Book of Mormon—is one of the many items now easily discoverable on the Internet.)

Such smokescreens don’t work anymore, now that we have the Internet. Before the Internet, when some Mormon leader would tell the faithful, in effect, “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain,” it was all too easy for the faithful to shrug their shoulders and go on with their daily lives. To fact-check the preacher, one would have to find the car keys, get in the car, drive to the library, find the right microfiche—oh, hell, let’s just stay home and watch Father Knows Best.

Now, though, everyone in America has the Internet in their homes, and they can easily research religious claims. Consequently, the Mormon Church is hemorrhaging members. (The church likes to claim it’s one of the world’s fastest-growing religions, thanks to those armies of well-scrubbed missionaries. That’s horseshit, as is their wont.)

Damn you to hell, Internet!

Indeed, the game is up. The LDS church is going to go first because of the embarrassing facts like the Book of Abraham, but the others will follow. Knowledge will win.

Now if you’ve been following along until this point, you’re probably irreligious or formerly religious or finding your way out of religion. (The religious folks probably won’t have lasted until now, if they even would have started reading the post in the first place.) You probably assumed I was headed toward some kind of climactic slur against the Almighty. Silly human. Far be it from me to the slur the Almighty. Religion’s going to die, but God’s not going anywhere. He has nothing to fear from knowledge. All truth is God’s truth. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be truth. God is the author of reality. He holds it together. He’s the reason there’s something rather than nothing.

So when religion’s gone, what are we to do about God? Actually, I think we’ll be in a better position to deal with God without religion. Religion just gets in the way, deluding us into thinking that we can apprehend divine matters. (Think “hall pass for heaven.”) Finally, we won’t have religion clouding our judgment. We’ll be able to see clearly that we know next to nothing. The more knowledge we gain, the further we realize we are from the truth. Life is an obstinate mystery. Knowledge will help us kill religion, but knowledge is powerless against God, bottomless font of truth. The ladder of knowledge doesn’t lead to God. It leads to more questions.

Get used to it.

Amen.

The post How the Internet is killing religion — Part 1 appeared first on A Danger to God Himself.

April 4, 2016

Occam’s Razor and the inactivity of God

Religious folks are often heard to say God works in mysterious ways. Ironically, when they say that, they’re usually trying to explain away an instance in which God apparently didn’t work. The child died of cancer. The promotion didn’t come through. The penis enlargement herbal remedy didn’t bear fruit.

His ways aren’t our ways.

The problem with this whole God Works In Mysterious Ways refrain is it turns Him into a . . . a . . . the right word eluded me as I was drafting this post. Originally I used a certain two-syllable expletive. You know the one. But my mom’s been asking me not to curse so much in my blog, so instead I used jerk in an early draft. When Mom read that early draft, she suggested the word wasn’t potent enough and offered monster. Seems to me that monster is more offensive than my two-syllable expletive. So . . . a mysterious expletive/jerk/monster. Take your pick. Whichever you use, He has a lot to answer for, which is why so many atheists are so ill-tempered, at least on the Internet. An atheist meme I saw on Facebook recently said, “Would you look the other way while a child is being raped? Then you’re more moral than your God.”

(As an aside, I should note that my mom also objected to the term “penis enlargement.” I hesitated but then figured she should be grateful I used “penis.”)

The only way out of this puzzle is to admit that God is impotent in important ways—that He’s not “all powerful.” The classic  refrain is God can’t be all good and all powerful, or there wouldn’t be suffering. Theologians have wrestled with this dilemma as long as there’s been monotheism.

refrain is God can’t be all good and all powerful, or there wouldn’t be suffering. Theologians have wrestled with this dilemma as long as there’s been monotheism.

I say we apply Occam’s Razor.

Do we want a God who could stop bad things from happening but chooses not to? (Easy for Him to say. It’s not His child being raped.) Or a God who hates the badness we suffer but can’t do a damn thing about it?

If those are the options, I’ll take Door Number 2.

In other words, God doesn’t do in so many, many instances because He can’t.

Can’t. It’s the simplest explanation.

It all boils down to the concept of power.

It’s no wonder God seems so powerless. Think about it. There is nothing that happens in the world that doesn’t happen in a physical/material basis. So God’s activity—to the extent He acts—is always unseen. There’s no miracle until the water becomes wine, but the mechanism of that transformation eludes us. Evolution we can explain. But what is the desire behind evolution? God’s power, like God Himself, remains invisible.

The best we can say—and salvage any idea of a powerful God—is that what God does in the world, He does subtly. He acts on the world the way a beautiful woman walking across the bar floor acts on a straight man. (I say that because it just happened to me, and the effect was subtle yet profound. She did nothing, yet she did everything.)

God romances creation.

Which means, from our point of view, that He’s frustratingly patient. He’s willing to wait millions of years for homo sapiens to emerge—with all the false starts and painful deformities—and then it’s hundreds of thousands of years after that before those hapless bipeds first form the rudimentary concepts that will lead to “God.”

He’s playing hard to get, as it were.

God is about process—incrementalism. (That’s a nod to my mom, who is a student of process theology.) That’s why He “uses” evolution. Even religious folks, if you push them, will admit that God works in their life in incremental ways. In the early years of the Christian church, leaders struggled with the conundrum that people continued to sin after being baptized. Imagine. The solution was the concept of sanctification—becoming more godly bit by bit—what Orthodox Christians now refer to as theosis. Essentially, it’s evolutionary salvation, which suits everyone fine, even the Young Earth Creationists. You can’t argue with the facts. No one become a Saint In A Day. (Though most religious folks, if they’re being honest, will confess to feeling better than nonbelievers.) Even Mormons, perfectionistic Mormons—God love ’em—will trot out the refrain that we learn “line by line.”

I’d go further. God’s activity in our lives—once again, to the extent He acts in our lives—is so incremental so as to be indiscernible. So it seems as if we’re on our own in this Grand Process, which brings up the importance of forgiving oneself on a daily basis, as we’re apt to misstep. To my way of thinking, that’s much more important than asking God to forgive us. He’s the one that put us in this situation. He gets incrementalism.

Now it’s our turn.

Photo: Straight razor (pre-restoration) by Jeff Vier CC BY0SA 2.0

The post Occam’s Razor and the inactivity of God appeared first on A Danger to God Himself.

March 27, 2016

What role should God play in your life?

So I wrote my first novel. It’s about a Mormon missionary who goes insane on his mission. And in the interest of research, when Mormon missionaries would knock on my door, I’d invite them in, every time. It usually didn’t end well. Invariably, they’d bear their testimony heatedly and storm off in a huff, insisting I had a “spirit of contention!”

They were probably right.

Anyway, this one missionary sticks in my mind. I named my novel’s protagonist after him.

Let me set the scene. Things were getting dicey. You know me—push, push, push. Elephants in pre-Columbia America. The Book of Abraham papyrus. Joseph Smith’s wandering wangdoodle. All that. Every time I’d push, they’d bear their testimony. This corn-fed missionary clearly had spied my book shelf, heavy with “anti-Mormon” books and DVDs. He glared at it with resolute menace.

“You and your frickin’ videos!” He barked. “You have no concern for the things of God!”

Are you a fool?

Frickin’. That’s really harsh for a Mormon missionary. Usually, the closest they get to an F Bomb is flippin’. It was righteous indignation, I guess. His was the biblical view: The fool hath said in his heart, “There is no God.” Fools aren’t just dumb. They’re evil. Morally fatuous, if you will—all because they won’t orbit their existence around God and are left with no recourse but self-centeredness. Stupid is as stupid does.

And I was one of them, in his mind: a frickin’ degenerate.

Little did he know. I was actually on a mission from God at the time. I was an Evangelical hell-bent on skewering Mormonism through my debut novel—every bit as zealous as himself. Joke was on him. I wasn’t godless. I was, I guess, god-ful. The difference was I was worshipping the right Jesus.

Joke was on me: I ended up losing my religion through the process of writing my novel. So it goes.

What’s the greatest commandment?

Still, though, I understand where he was coming from. I still have ready access to the religious worldview. In that worldview, unbelievers are fools, as noted above, morally crippled by their self-centeredness. Our salvation, as the corn-fed missionary believed, was in centering of lives on the Things of God. To be the humans God wants us to be we must focus on God.

That was Jesus’ view. Asked what the greatest commandment was, Jesus said it was To Love The Lord Your God With All Your Heart And All Your Soul And All Your Might. The second most important commandment was to Love Your Neighbor As Yourself. The only reason we can’t serve others is we have our eyes on ourselves and off God. We can’t be good without God. Everything must be done for the Glory of God. The Bible refers to the good deeds of the ungodly as filthy rags, unclean because of their essential selfishness. If you’re not focusing on God, you’re left with no other recourse but to focus on yourself. Vanity of vanities!

Which circle best describes your life?

When I was in college, I joined Campus Crusade for Christ. As a member of that organization, I was expected to “witness,” which consisted of approaching students on campus and sharing the gospel. (Yes, I was a missionary, I guess.) Specifically, we would come up to unsuspecting people sunning on the lawn in the quad or eating lunch in the student union building and ask them, “Have you heard of the Four Spiritual Laws?”

Law 1: God loves you and has a wonderful plan for your life.

“However,” we’d ask, “why is it that most people are not experiencing God’s plan for their life?” That led to . . .

Law 2: All of us sin and our sin has separated us from God.

“We were created to have fellowship with God,” we’d say, “but because of our stubborn self-will, we chose to go our own independent way and fellowship with God was broken.” That led to . . .

Law 3: Jesus Christ is God’s only provision for our sin. Through Him we can know and experience God’s love and plan for our life.

“However,” we’d say, ‘it’s not enough just to know these three principles,” leading to . . .

Law 4: We must individually receive Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord. Then we can know and experience God’s love and plan for our lives.

“Receiving Christ involves turning to God from self and trusting Christ to come into our lives to forgive us and to make us what He wants us to be,” we’d say.

Then we would show them this diagram:

“Which circle best describes your life?” we’d ask. It was like asking somebody, “Have you stopped beating your wife?” No one wants to admit they’re selfish—and we were telling them the only alternative to selfishness was God-centeredness.

If they chose the Christ-directed circle, we’d lead them in The Sinner’s Prayer, the capstone of which is “Take control of the throne of my life and make me the kind of person You want me to be.”

In other words . . . we can’t be good without God, But what does that mean? How does one love God with one’s whole heart, practically speaking? How do you put Christ on the throne of your life on a daily basis? By reading the Bible? Please. You hear His voice? Call the folks from the Funny Farm. How can you focus on an invisible, silent being?

You can’t.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying God doesn’t exist. If you’ve raced to that conclusion, you’re mistaken. There is a thing called God that created space and time. He’s just not accessible.

Not to sell God short, but . . .

Religious folks cry, “Not true! God acts in my life.” Really? If you probe these religious folks about how God acts in their life you’ll find two things:

First off, most of the acts of God in a believer’s life are perceived in hindsight. God really taught me something through that trial or I can see there was a purpose to it all now. And so on. If God does act in our life, we can’t recognize Him doing it, for the most part. It’s so incremental so as to imperceptible, like the continents sloughing off into the ocean.

Secondly, when they can point to God acting in the present it’s always through humans. God really touched me with that song or God brought you into my life or God spoke through you.

So what can we learn from that? I think God’s intention is clear. He knows we can’t focus on Him, so he wants us to focus on each other. That’s the whole point—the point of life. The second commandment is actually the first commandment. Jesus was wrong. Turns out, the Things Of God are the Things Of Men.

I don’t want to sell God short. Nothing would exist without God. We owe God not just for our creation but for every second of our existence. We only keep on keeping on because God holds reality together. In fact, He’s the only Necessary Thing. We’re certainly not necessary.

But God is totally unnecessary in crucial one sense—when it comes to how we lead our lives. Let me be more plain: We Don’t Need God. We don’t need Him to be good. We don’t need Him to be selfless. God doesn’t act in our lives. He can’t act in our lives. That’s not the way things work.

So what good is God? Well, as I said, He holds reality together—no small matter, that—but, past that, we’re pretty much on our own. That’s why we need each other. That’s why a life focused on self is . . . foolish. Not because we’re not focusing on God. Rather, because we’re not focusing on others. Therein lies our salvation.

Photo: Christ as Judge 3 by Waiting for the word CC BY 2.0

The post What role should God play in your life? appeared first on A Danger to God Himself.

A Danger to God Himself

- John Draper's profile

- 12 followers