Charles Atkins's Blog, page 4

January 7, 2012

A Road Well Traveled: The Physician-Author and the Contin...

A Road Well Traveled: The Physician-Author and the Continuum of StoryByCharles Atkins, MD

"Thereis no more difficult art to acquire than the art of observation, and for somemen it is quite as difficult to record an observation in brief and plainlanguage."

--William Osler

It'sno accident that there are so many physician authors, from Somerset Maugham andArthur Conan Doyle to modern best-sellers like Robin Cook, Tess Gerritson,Michael Palmer, Michael Crighton and F. Paul Wilson. As I pursue dual careers of author andpsychiatrist I realize that this connection is logical and rooted in ourprofession's reliance on stories: hearing them, using them and tellingthem. How we get from one end of thestorytelling spectrum to the other is a well-trod road that takes us from theclinical record through authoritative non-fiction to the mainstream novel. Itstarts with the doctor's training. Welearn to take a history. "So, whatbrings you in today?" It's thesimplicity of an open-ended question that invites any response. "I've had a cough that won't go away," "I gotthis rash after I came back from Vegas," "Every time I walk up a flight ofstairs I feel heaviness in my chest." The answers come with emotion and body language; we observe it all: thepain, the fear, the embarrassment. Weshape the story, and even enter it, as our attitude and willingness to listenhave a strong bearing on whether our patient will trust us enough to give usthe truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. The more interested, relaxed andnon-judgmental we are, the greater the chances of getting the information. We generate hypotheses about the cough, therash, and the heaviness. We ask morequestions, "How long have you had the cough?" "What happened in Vegas?" "Tell me about the feeling in yourchest." We're careful not to jump tooquickly to a diagnosis, as missteps in the gathering of a history lead to wastedtime and bad treatment. A cough could bethe common cold, or the only symptom of a malignancy. The rash could be from the detergent used onthe hotel's sheets or a psychosomatic concern over an extramaritalliaison. Is the chest pain indigestion,angina, panic? Ultimately, it's thephysician's skill in taking and interpreting a history that is our singlemost-important tool. It's all aboutgathering the data, interpreting it, and putting together a story that makessense. AsI think back through medical school and residency, I can see that I was taughtbasic truths about the nature of story that have helped me both clinically andas a writer: Common things are common; when you hear hooves, don't think zebras.Consider all angles, who, what, when, where, why?Don't jump to conclusions; generate a differential.Consider your reader. Oncewe've fleshed out the story, it's time to write it down. As medical students and trainees we learnedhow to present and write up a case. Iremember how as a med student I would be assigned a patient in the emergencyroom, work them up, and then, with little or no sleep, present them to a roomfull of other trainees and a Chief of Services who delighted in grilling us. He wanted the whole story and he wanted itwith multiple possible endings. "So Dr.Atkins, please enlighten us with the story of your patient, Mr. Jones…" Ipresented in the time-honored way. It'sclinical, it's dry as dust, but it is a story. "Mr. Jones is a 42 year old never-married Caucasian man who presentswith three days of sub-sternal chest pain that he describes as, 'crushing, likesomething is sitting on me'. It's worsewith exertion, is relieved with rest and radiates to his jaw, but not down hisarm…" Learningto obtain a history and present a case—in both written and oral fashion--lays muchof the groundwork for the doctor-writer. Obviously, there's a difference between what and how we write in amedical record and what's likely to become a blockbuster novel, but similarskills are required for both. I've cometo view these different approaches to story as points on a continuum. On one end we have the most-objectiveclinical reporting and on the other, personal narrative and finally fiction. Similarto popular non-fiction and fiction, the medical record as a repository of storyserves multiple purposes and has multiple readers. All of which must be considered when leavinga note in a medical record. Thehistories we write lay out the clinical data upon which we arrive at ourdiagnostic impressions and conclusions. Our notes reflect why we're prescribing various treatments and whether,and how, they're working. Our chartsmust meet criteria for 'medical necessity' as defined by various insurers,Medicare and Medicaid should we wish to get paid and not get hauled into courtfor fraud. We need to remember the JointCommission reviewer who will look at what we've written to see that we'restaying current, are avoiding confusing abbreviations and are cognizant of allaspects of the human being—as defined in their hundreds of published standardsof care. What we write needs to be clearso that a colleague covering in the middle of the night knows what is goingon. Should there be a bad clinicaloutcome, the chart is a legal record where the written story is all thatmatters, 'if it's not in the chart, it didn't happen'. Justas when writing a novel or non fiction book, I need to consider my readerswhenever I document in a chart. Assomeone who teaches clinical documentation I stress the importance of imaginingeveryone who could one day read your note standing over your shoulder: theinsurance reviewer, the attorney for a patient wishing to sue you, the hospitalrisk manager, the patient's mother, the patient, your colleagues, and ofcourse, you. Themedical record requires a particular type of storytelling. It must be factual and free fromeditorializing. Judgment-laden words andphrases like, patient is manipulative,non compliant, difficult, should be eliminated. Just stick to what happened, what was observed. Or as they say in writer's lingo "show, don'ttell". Evenwith this attention to the facts, the medical record is highly subjective. When teaching, I'll give a class of studentsthe data from a single patient and instruct them to write up their formulationand present the case aloud. If there areten students I'll hear ten different stories. From the case presentationor case study we come to the jumping off point that separates clinical writingfrom narrative and fiction. Forphysician-authors this leap is not far or difficult. Take the following examples of a standardHistory of Present Illness, which is then rewritten as a personal narrative (itcould also be viewed as the inner monologue of a character in a novel).Case 1: Case Presentation: Patientis a 48 year old Caucasian man brought by ambulance to the emergency roomfollowing a near fatal suicide attempt by carbon monoxide poisoning in thecontext of multiple recent stresses—loss of job, separation from spouse andchildren and severe financial difficulties. For the past four weeks the patient has experienced worsening symptomsof depression including diminished sleep with difficulty falling asleep, earlymorning awakening and mid-night arousal, feelings of worthlessness andhopelessness and increased thoughts of suicide with a plan to kill himself,which he attempted earlier today. Clientwas discovered by a neighbor who was concerned by the sound of the car enginein the closed garage.

Case 1: Personal Narrative:It'sso hard to find words. Everything insideme feels dead. I don't want to writethis, or think. I'd like to go away andbe done with everything. I'm sosorry. I've screwed up everything; mylife…Peg's the kids. I can't shake this,and they'll be better off without me. Ishould be looking for a job. John toldme the layoff wasn't anything to do with my performance. Others got laid off—I know this--but how doyou not take it personally? I feel likea total failure. Like everything I'veworked for all of these years didn't matter. You're with a company for 20 years and they tell you it's not personalwhen you have two weeks to say goodbye, clean out your desk, and go for jobcounseling, which was pointless. I can'tsleep. I lay there, the same thoughtsover and over through my head, everything is coming undone. Two month's of not paying the mortgage. I don't have the money for the taxes. No one's going to hire me, not for anythingclose to what I was making. I'm almostfifty. My whole life is unraveling andthere's nothing I can do to stop it. Iget up and even the television is too much. I can't focus. I hear Leno tell ajoke, I used to think he was hysterical; it's not funny, even though I hear theaudience laugh. I used to laugh all thetime. People would come up to me andtell me what a happy person I must be because I'm always smiling. Every day, every hour I think about the carand how easy it would be to do this. Theweird part is that thinking about killing myself doesn't feel bad, more like a relief, just bedone with it. I think that's what I'lldo. I'll do it in the morning.

Once across thisdivide, how far we go as writers is limited only by our interest, perseverance,talent and skill. My interest as anovelist has been to take psychiatric and forensic topics and explore them infiction. I picked the mainstream genreof the psychological thriller, 'A' because I like to read these, 'B' becausethey're commercially viable and 'C' because as a psychiatrist I know somethingabout human nature and why we do the things we do -- even bad things. The medium of novels is ideal for in-depthexploration of complex subject matter. For the would-bedoctor-writer, there aren't a lot of absolute rules, but there are some helpfulhints. Go with your expertise and writewhat you know. Beyond that most of theprinciples of clinical writing continue to apply, you need to think of yourreader, and pay attention to the conventions of whatever genre you'vepicked. Just as you consider theMedicare, Managed Care and Joint Commission reviewers when writing in a chart,think about who's going to read your book and give them what they want. In novels thefirst goal is to entertain—why else would someone purchase one? Because I write thrillers they need togenerate tension, suspense and fear; they must snag the reader at the firstpage and not let up. Beyond that I wantto educate, both the reader and myself about topics I find interesting,confusing and important. This is whereclinical skill and experience can inform fiction. For instance, inmy first book, THE PORTRAIT (St. Martin's Press 1998) I wrote a thriller thathad a hero with a serious mental illness, in this case an artist with Bipolar Disorder(manic depression). I wanted to createan insider's view of what it's like to have a serious mental illness, to becomepsychotic, paranoid and even suicidal. Ichose a first-person narrative so that the reader could have this voice insidetheir head. "It was funny, the times I had beenin the hospital; they didn't seem quite real, that this, my real life, would bea memory, like a trick done with mirrors. So many ghosts followed me—quick friendships on locked wards, endlessmouth checks with hard-faced nurses. Theghosts filled my paintings, worlds populated with earthbound saints andtormented devils. My own Faustiandilemma became a little clearer each year. If I took the pills, so I was told repeatedly, I could avoid thehospital. I could also kiss paintinggood-bye. So I juggled."

When I came to mysecond book, it was at a time when I was working with troubled teenagers whowere coming for evaluations at the request of the court, the schools, orparents faced with an out-of-control kid. RISK FACTOR (St. Martin's Press 1999), allowed me to demonstrate infiction the process by which a child grows up to become a sociopath. I relied heavily on the theory ofexperimental psychologist John Bowlby, combined with what I was seeing in myclinical practice. I created situationsand a cast of characters that allowed me to show many sides of AttachmentTheory. My protagonist was a singlemother of two working with troubled teenagers in both inpatient and outpatientsettings. In a sense, thenovel can be a delivery system for information. Material that might otherwise be dry and conceptually difficult can bebrought to life in ways that are crisp and evocative.More recently, inthe wake of 911, Hurricane Katrina and some personal tragedies, I took thetopics of Trauma, PTSD etc. and wove them into a thriller, THE CADAVER'S BALL (St. Martin's Press 2005/Leisure Books 2006). I wanted to demonstrate through multiplecharacters how life-threatening events change us, how some people recover andothers are destroyed by the experience. In this case my protagonist is a psychiatrist who has been severelytraumatized.

"After a year of intensive therapy,I know this. I feel it claw at mysanity. Oh, God, make it stop!My fingers claw at smolderingsteel, as black smoke burns my eyes, "come on, Beth!" I can't see, I can't breathe. The smell of gas. Help me! Somebody help me! She's notmoving, her hair caught in the shoulder strap? I smash the window, but I can't get the door. She's not breathing. I suck in and put my head through shatteredglass, my mouth over hers, tasting her lipstick. Headlights come through the fog. I stagger into the road. My hands wave, "stop!" The whites of a man's eyes stare through thedarkened glass. "Please stop." He slows and I grab for the closed window;it's cold against my blistering palm. Why isn't he stopping? I bang myhand against his window. "She's dying!Help me!" My palm print, smeared inblood, slips away; he's speeding up. Iscream. A blue sparks turns to flames; it's in her hair. Help me! I startledand blinked as a hand tapped my shoulder. "DoctorGrainger. Peter, are you okay?" Icoughed and fought back the nausea that always comes. "I'm fine," I said, not knowing where I was,wondering how long I'd been gone.

While thecharacters are products of my imagination, what they go through is real. This is what I find most-exciting aboutfiction; we can get to truths about mental illness and human nature and presentthem in ways that are easily understood by the reader. When physicians spanthis continuum of clinical storytelling, from the medical record and casepresentations to narrative and fiction, something has been completed. It's taking what we're taught in our trainingand in our clinical practice and giving it life. It's a practical fusion of the science we learnas medical professionals and the art of being both a doctor and a writer. Beyond that, pushing clinical material intothe realm of fiction offers endless opportunities to gather insight into thewonderful complexity of being human. Forphysicians, this is a well-trod path that's worth the trip. Our training as doctors starts us on theroad; should we choose to follow, it brings us to the whole story, the wholeperson and the bigger truth.

Published on January 07, 2012 10:14

January 1, 2012

The Wall of Unwanted Books

The Wall of Unwanted Books

By

Charles Atkins

" I have learned, that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours."

--Henry David Thoreau

Do all authors have a drawer of unpublished books? Or is this just me? As I hit the final pre-release weeks of one-such manuscript that will finally be published, there are numerous lessons to be learned. But as so much with writing it's more about the showing than the telling.

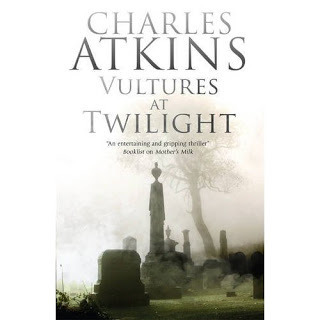

So here's the story of how VULTURES AT TWILIGHT, which I wrote over a decade ago as a charming Connecticut cozy with two older female protagonists (for those not used to the term "cozy" it refers to a not-terribly gory murder mystery often set in a small town--Agatha Christie's Miss Marple is the archetype), will now come out as my first lesbian-themed novel.

How does this happen? Well, in the late 1990's I achieved a major score--or more accurately my agent did--by landing a two-book deal with St. Martin's Press. My first novel--THE PORTRAIT--did well and so I set about crafting a follow up book. My editor at St. Martin's was Ruth Cavin--a legend in the field--who at the time was in her early eighties. I was also working as a geriatric psychiatrist. My thought--write what you know--was to do a mainstream mystery but this time have heroines in their late seventies and early eighties. I set the book in a fictional Connecticut town that thrives off the systematic fleecing of its older residents as they downsize and die. It was a theme I knew well from my day job, and so I constructed a darkly comic mystery where the local antique dealers were getting bumped off one by one. I finished the manuscript, had a few people read it, did a rewrite or two, then off to my agent who submitted it to Ruth at St. Martins...who hated it.

Her rejection letter was scathing. This was not going to be the second book in that contract. And therein lies one of the many lessons I've learned--read your contracts carefully. A multi-book deal does not mean that the publisher is obliged to print whatever you send. Ruth did not care for the book, and so it was not going to press, at least not then and not with St. Martin's.

My then agent, shopped it around a bit, but clearly I needed to get back to the drawing board and come up with something to fulfill my contract and so VULTURES AT TWILIGHT--at the time it was actually named DOILIES UNDER GLASS--landed in a drawer. To be fully accurate this is more of a shelf that over the years has taken on the look of a brick wall made out of tightly stacked manuscript boxes with titles of the enclosed, often with dates, written on the side in black sharpie. Time elapsed I came up with two more books for St. Martin's, which they did publish. Between books I'd dust of VULTURES AT TWILIGHT, give it a rewrite, send it out, read the rejection letters and then slide it lovingly back into my wall of unwanted books.

At one point there was a near hit with a small specialty publishing house--they will go unnamed. They had a series of professional readers review the manuscript, it looked promising. They held onto VULTURES for eighteen months as an exclusive submission, before ultimately rejecting it. At least here, I could read the critiques from their readers, and came away with the conviction that indeed this book was publishable. I gleaned anything of value from the reviews and I re-worked the manuscript yet again. But with no likely buyers in site the options were limited. Do I self publish? Or...back onto the shelf?

Here, I was a torn. Self publishing has become increasingly acceptable and affordable. Yet part of me clings to the notion that if no one in the "real" publishing world is ready to give it a go, maybe it needs to stay on the shelf. And while the differences between self-publishing and having a publisher bring out a book have become fewer there are still some big hurdles that the self-published author must consider. Most notably, how do you get a self-published book reviewed in the bigger publications? Not to mention I really do like that initial advance check.

So VULTURES sat on the shelf until I got a call from my agent Al Zuckerman--and any author should be so lucky to have an agent like Al. He'd just had lunch with the editor at a gay-themed publishing house, and he'd brought up my name. He wondered if I was interested in writing a mystery or thriller series with a gay protagonist. Looking back at my wall of unwanted books, I spotted my very first manuscript--a rambling six-hundred page story of a conflicted gay surgeon. It's part love story, part action adventure, part mystery, part buddy book and total mess. It's quite possibly the worst thing I've ever written. So I told him I'd think about it, and while I was deep into another project gave it serious thought.

Which is when it hit me. What if...What if the two women protagonists in VULTURES fell in love with another? They were already the best of friends, was it such a leap? As it stood, the book had no love line and this made tremendous sense. In discussing it with a gay friend of mine she thought it would work, but I'd need to make them a bit younger--and so I did. It took a solid two months to get a strong rewrite, and what emerged is a book that is a tremendous amount of fun. However....

By the time it was ready to be submitted to the gay-themed publishing house, they'd gone through radical restructuring and the editor I'd written this for, had left. So back to the shelf...or so I thought. And this is where we get our happy ending, or maybe a fresh start. Unbeknownst to me, my agent had forwarded the new gay-themed VULTURES AT TWILIGHT to Severn House, a British independent who's published my last two hard covers. Sure enough they wanted it, but only as a series. If I could commit to at least a second book with my two heroines--Lil and Ada--it was a go. And now VULTURES AT TWILIGHT will be released in January 2012 in the U.K. and later this year in the U.S. with the e-version to follow a few months later. And the moral of this story, which is old and worth revisiting, persistence does pay, and often in unexpected and wonderful ways.

Vultures at Twilight

By

Charles Atkins

" I have learned, that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours."

--Henry David Thoreau

Do all authors have a drawer of unpublished books? Or is this just me? As I hit the final pre-release weeks of one-such manuscript that will finally be published, there are numerous lessons to be learned. But as so much with writing it's more about the showing than the telling.

So here's the story of how VULTURES AT TWILIGHT, which I wrote over a decade ago as a charming Connecticut cozy with two older female protagonists (for those not used to the term "cozy" it refers to a not-terribly gory murder mystery often set in a small town--Agatha Christie's Miss Marple is the archetype), will now come out as my first lesbian-themed novel.

How does this happen? Well, in the late 1990's I achieved a major score--or more accurately my agent did--by landing a two-book deal with St. Martin's Press. My first novel--THE PORTRAIT--did well and so I set about crafting a follow up book. My editor at St. Martin's was Ruth Cavin--a legend in the field--who at the time was in her early eighties. I was also working as a geriatric psychiatrist. My thought--write what you know--was to do a mainstream mystery but this time have heroines in their late seventies and early eighties. I set the book in a fictional Connecticut town that thrives off the systematic fleecing of its older residents as they downsize and die. It was a theme I knew well from my day job, and so I constructed a darkly comic mystery where the local antique dealers were getting bumped off one by one. I finished the manuscript, had a few people read it, did a rewrite or two, then off to my agent who submitted it to Ruth at St. Martins...who hated it.

Her rejection letter was scathing. This was not going to be the second book in that contract. And therein lies one of the many lessons I've learned--read your contracts carefully. A multi-book deal does not mean that the publisher is obliged to print whatever you send. Ruth did not care for the book, and so it was not going to press, at least not then and not with St. Martin's.

My then agent, shopped it around a bit, but clearly I needed to get back to the drawing board and come up with something to fulfill my contract and so VULTURES AT TWILIGHT--at the time it was actually named DOILIES UNDER GLASS--landed in a drawer. To be fully accurate this is more of a shelf that over the years has taken on the look of a brick wall made out of tightly stacked manuscript boxes with titles of the enclosed, often with dates, written on the side in black sharpie. Time elapsed I came up with two more books for St. Martin's, which they did publish. Between books I'd dust of VULTURES AT TWILIGHT, give it a rewrite, send it out, read the rejection letters and then slide it lovingly back into my wall of unwanted books.

At one point there was a near hit with a small specialty publishing house--they will go unnamed. They had a series of professional readers review the manuscript, it looked promising. They held onto VULTURES for eighteen months as an exclusive submission, before ultimately rejecting it. At least here, I could read the critiques from their readers, and came away with the conviction that indeed this book was publishable. I gleaned anything of value from the reviews and I re-worked the manuscript yet again. But with no likely buyers in site the options were limited. Do I self publish? Or...back onto the shelf?

Here, I was a torn. Self publishing has become increasingly acceptable and affordable. Yet part of me clings to the notion that if no one in the "real" publishing world is ready to give it a go, maybe it needs to stay on the shelf. And while the differences between self-publishing and having a publisher bring out a book have become fewer there are still some big hurdles that the self-published author must consider. Most notably, how do you get a self-published book reviewed in the bigger publications? Not to mention I really do like that initial advance check.

So VULTURES sat on the shelf until I got a call from my agent Al Zuckerman--and any author should be so lucky to have an agent like Al. He'd just had lunch with the editor at a gay-themed publishing house, and he'd brought up my name. He wondered if I was interested in writing a mystery or thriller series with a gay protagonist. Looking back at my wall of unwanted books, I spotted my very first manuscript--a rambling six-hundred page story of a conflicted gay surgeon. It's part love story, part action adventure, part mystery, part buddy book and total mess. It's quite possibly the worst thing I've ever written. So I told him I'd think about it, and while I was deep into another project gave it serious thought.

Which is when it hit me. What if...What if the two women protagonists in VULTURES fell in love with another? They were already the best of friends, was it such a leap? As it stood, the book had no love line and this made tremendous sense. In discussing it with a gay friend of mine she thought it would work, but I'd need to make them a bit younger--and so I did. It took a solid two months to get a strong rewrite, and what emerged is a book that is a tremendous amount of fun. However....

By the time it was ready to be submitted to the gay-themed publishing house, they'd gone through radical restructuring and the editor I'd written this for, had left. So back to the shelf...or so I thought. And this is where we get our happy ending, or maybe a fresh start. Unbeknownst to me, my agent had forwarded the new gay-themed VULTURES AT TWILIGHT to Severn House, a British independent who's published my last two hard covers. Sure enough they wanted it, but only as a series. If I could commit to at least a second book with my two heroines--Lil and Ada--it was a go. And now VULTURES AT TWILIGHT will be released in January 2012 in the U.K. and later this year in the U.S. with the e-version to follow a few months later. And the moral of this story, which is old and worth revisiting, persistence does pay, and often in unexpected and wonderful ways.

Vultures at Twilight

Published on January 01, 2012 13:43

•

Tags:

charles-atkins, connecticut, glbt, glbtq, lesbian, mystery, ruth-cavin, severn, vultures-at-twilight

The Wall of Unwanted Books

The Wall of Unwanted Books

By

Charles Atkins

" I have learned, that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours."

--Henry David Thoreau

Do all authors have a drawer of unpublished books? Or is this just me? As I hit the final pre-release weeks of one-such manuscript that will finally be published, there are numerous lessons to be learned. But as so much with writing it's more about the showing than the telling.

So here's the story of how VULTURES AT TWILIGHT, which I wrote over a decade ago as a charming Connecticut cozy with two older female protagonists (for those not used to the term "cozy" it refers to a not-terribly gory murder mystery often set in a small town--Agatha Christie's Miss Marple is the archetype), will now come out as my first lesbian-themed novel.

How does this happen? Well, in the late 1990's I achieved a major score--or more accurately my agent did--by landing a two-book deal with St. Martin's Press. My first novel--THE PORTRAIT--did well and so I set about crafting a follow up book. My editor at St. Martin's was Ruth Cavin--a legend in the field--who at the time was in her early eighties. I was also working as a geriatric psychiatrist. My thought--write what you know--was to do a mainstream mystery but this time have heroines in their late seventies and early eighties. I set the book in a fictional Connecticut town that thrives off the systematic fleecing of its older residents as they downsize and die. It was a theme I knew well from my day job, and so I constructed a darkly comic mystery where the local antique dealers were getting bumped off one by one. I finished the manuscript, had a few people read it, did a rewrite or two, then off to my agent who submitted it to Ruth at St. Martins...who hated it.

Her rejection letter was scathing. This was not going to be the second book in that contract. And therein lies one of the many lessons I've learned--read your contracts carefully. A multi-book deal does not mean that the publisher is obliged to print whatever you send. Ruth did not care for the book, and so it was not going to press, at least not then and not with St. Martin's.

My then agent, shopped it around a bit, but clearly I needed to get back to the drawing board and come up with something to fulfill my contract and so VULTURES AT TWILIGHT--at the time it was actually named DOILIES UNDER GLASS--landed in a drawer. To be fully accurate this is more of a shelf that over the years has taken on the look of a brick wall made out of tightly stacked manuscript boxes with titles of the enclosed, often with dates, written on the side in black sharpie. Time elapsed I came up with two more books for St. Martin's, which they did publish. Between books I'd dust of VULTURES AT TWILIGHT, give it a rewrite, send it out, read the rejection letters and then slide it lovingly back into my wall of unwanted books.

At one point there was a near hit with a small specialty publishing house--they will go unnamed. They had a series of professional readers review the manuscript, it looked promising. They held onto VULTURES for eighteen months as an exclusive submission, before ultimately rejecting it. At least here, I could read the critiques from their readers, and came away with the conviction that indeed this book was publishable. I gleaned anything of value from the reviews and I re-worked the manuscript yet again. But with no likely buyers in site the options were limited. Do I self publish? Or...back onto the shelf?

Here, I was a torn. Self publishing has become increasingly acceptable and affordable. Yet part of me clings to the notion that if no one in the "real" publishing world is ready to give it a go, maybe it needs to stay on the shelf. And while the differences between self-publishing and having a publisher bring out a book have become fewer there are still some big hurdles that the self-published author must consider. Most notably, how do you get a self-published book reviewed in the bigger publications? Not to mention I really do like that initial advance check.

So VULTURES sat on the shelf until I got a call from my agent Al Zuckerman--and any author should be so lucky to have an agent like Al. He'd just had lunch with the editor at a gay-themed publishing house, and he'd brought up my name. He wondered if I was interested in writing a mystery or thriller series with a gay protagonist. Looking back at my wall of unwanted books, I spotted my very first manuscript--a rambling six-hundred page story of a conflicted gay surgeon. It's part love story, part action adventure, part mystery, part buddy book and total mess. It's quite possibly the worst thing I've ever written. So I told him I'd think about it, and while I was deep into another project gave it serious thought.

Which is when it hit me. What if...What if the two women protagonists in VULTURES fell in love with another? They were already the best of friends, was it such a leap? As it stood, the book had no love line and this made tremendous sense. In discussing it with a gay friend of mine she thought it would work, but I'd need to make them a bit younger--and so I did. It took a solid two months to get a strong rewrite, and what emerged is a book that is a tremendous amount of fun. However....

By the time it was ready to be submitted to the gay-themed publishing house, they'd gone through radical restructuring and the editor I'd written this for, had left. So back to the shelf...or so I thought. And this is where we get our happy ending, or maybe a fresh start. Unbeknownst to me, my agent had forwarded the new gay-themed VULTURES AT TWILIGHT to Severn House, a British independent who's published my last two hard covers. Sure enough they wanted it, but only as a series. If I could commit to at least a second book with my two heroines--Lil and Ada--it was a go. And now VULTURES AT TWILIGHT will be released in January 2012 in the U.K. and later this year in the U.S. with the e-version to follow a few months later. And the moral of this story, which is old and worth revisiting, persistence does pay, and often in unexpected and wonderful ways.

Vultures at Twilight

By

Charles Atkins

" I have learned, that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours."

--Henry David Thoreau

Do all authors have a drawer of unpublished books? Or is this just me? As I hit the final pre-release weeks of one-such manuscript that will finally be published, there are numerous lessons to be learned. But as so much with writing it's more about the showing than the telling.

So here's the story of how VULTURES AT TWILIGHT, which I wrote over a decade ago as a charming Connecticut cozy with two older female protagonists (for those not used to the term "cozy" it refers to a not-terribly gory murder mystery often set in a small town--Agatha Christie's Miss Marple is the archetype), will now come out as my first lesbian-themed novel.

How does this happen? Well, in the late 1990's I achieved a major score--or more accurately my agent did--by landing a two-book deal with St. Martin's Press. My first novel--THE PORTRAIT--did well and so I set about crafting a follow up book. My editor at St. Martin's was Ruth Cavin--a legend in the field--who at the time was in her early eighties. I was also working as a geriatric psychiatrist. My thought--write what you know--was to do a mainstream mystery but this time have heroines in their late seventies and early eighties. I set the book in a fictional Connecticut town that thrives off the systematic fleecing of its older residents as they downsize and die. It was a theme I knew well from my day job, and so I constructed a darkly comic mystery where the local antique dealers were getting bumped off one by one. I finished the manuscript, had a few people read it, did a rewrite or two, then off to my agent who submitted it to Ruth at St. Martins...who hated it.

Her rejection letter was scathing. This was not going to be the second book in that contract. And therein lies one of the many lessons I've learned--read your contracts carefully. A multi-book deal does not mean that the publisher is obliged to print whatever you send. Ruth did not care for the book, and so it was not going to press, at least not then and not with St. Martin's.

My then agent, shopped it around a bit, but clearly I needed to get back to the drawing board and come up with something to fulfill my contract and so VULTURES AT TWILIGHT--at the time it was actually named DOILIES UNDER GLASS--landed in a drawer. To be fully accurate this is more of a shelf that over the years has taken on the look of a brick wall made out of tightly stacked manuscript boxes with titles of the enclosed, often with dates, written on the side in black sharpie. Time elapsed I came up with two more books for St. Martin's, which they did publish. Between books I'd dust of VULTURES AT TWILIGHT, give it a rewrite, send it out, read the rejection letters and then slide it lovingly back into my wall of unwanted books.

At one point there was a near hit with a small specialty publishing house--they will go unnamed. They had a series of professional readers review the manuscript, it looked promising. They held onto VULTURES for eighteen months as an exclusive submission, before ultimately rejecting it. At least here, I could read the critiques from their readers, and came away with the conviction that indeed this book was publishable. I gleaned anything of value from the reviews and I re-worked the manuscript yet again. But with no likely buyers in site the options were limited. Do I self publish? Or...back onto the shelf?

Here, I was a torn. Self publishing has become increasingly acceptable and affordable. Yet part of me clings to the notion that if no one in the "real" publishing world is ready to give it a go, maybe it needs to stay on the shelf. And while the differences between self-publishing and having a publisher bring out a book have become fewer there are still some big hurdles that the self-published author must consider. Most notably, how do you get a self-published book reviewed in the bigger publications? Not to mention I really do like that initial advance check.

So VULTURES sat on the shelf until I got a call from my agent Al Zuckerman--and any author should be so lucky to have an agent like Al. He'd just had lunch with the editor at a gay-themed publishing house, and he'd brought up my name. He wondered if I was interested in writing a mystery or thriller series with a gay protagonist. Looking back at my wall of unwanted books, I spotted my very first manuscript--a rambling six-hundred page story of a conflicted gay surgeon. It's part love story, part action adventure, part mystery, part buddy book and total mess. It's quite possibly the worst thing I've ever written. So I told him I'd think about it, and while I was deep into another project gave it serious thought.

Which is when it hit me. What if...What if the two women protagonists in VULTURES fell in love with another? They were already the best of friends, was it such a leap? As it stood, the book had no love line and this made tremendous sense. In discussing it with a gay friend of mine she thought it would work, but I'd need to make them a bit younger--and so I did. It took a solid two months to get a strong rewrite, and what emerged is a book that is a tremendous amount of fun. However....

By the time it was ready to be submitted to the gay-themed publishing house, they'd gone through radical restructuring and the editor I'd written this for, had left. So back to the shelf...or so I thought. And this is where we get our happy ending, or maybe a fresh start. Unbeknownst to me, my agent had forwarded the new gay-themed VULTURES AT TWILIGHT to Severn House, a British independent who's published my last two hard covers. Sure enough they wanted it, but only as a series. If I could commit to at least a second book with my two heroines--Lil and Ada--it was a go. And now VULTURES AT TWILIGHT will be released in January 2012 in the U.K. and later this year in the U.S. with the e-version to follow a few months later. And the moral of this story, which is old and worth revisiting, persistence does pay, and often in unexpected and wonderful ways.

Vultures at Twilight

Published on January 01, 2012 13:43

•

Tags:

charles-atkins, connecticut, glbt, glbtq, lesbian, mystery, ruth-cavin, severn, vultures-at-twilight

The Wall of Unwanted BooksByCharles Atkins" I have learn...

The Wall of Unwanted BooksByCharles Atkins" I have learned, that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours." --Henry David ThoreauDo all authors have a drawer of unpublished books? Or is this just me? As I hit the final pre-release weeks of one-such manuscript that will finally be published, there are numerous lessons to be learned. But as so much with writing it's more about the showing than the telling. So here's the story of how VULTURES AT TWILIGHT, which I wrote over a decade ago as a charming Connecticut cozy with two older female protagonists (for those not used to the term "cozy" it refers to a not-terribly gory murder mystery often set in a small town--Agatha Christie's Miss Marple is the archetype), will now come out as my first lesbian-themed novel.How does this happen? Well, in the late 1990's I achieved a major score--or more accurately my agent did--by landing a two-book deal with St. Martin's Press. My first novel--THE PORTRAIT--did well and so I set about crafting a follow up book. My editor at St. Martin's was Ruth Cavin--a legend in the field--who at the time was in her early eighties. I was also working as a geriatric psychiatrist. My thought--write what you know--was to do a mainstream mystery but this time have heroines in their late seventies and early eighties. I set the book in a fictional Connecticut town that thrives off the systematic fleecing of its older residents as they downsize and die. It was a theme I knew well from my day job, and so I constructed a darkly comic mystery where the local antique dealers were getting bumped off one by one. I finished the manuscript, had a few people read it, did a rewrite or two, then off to my agent who submitted it to Ruth at St. Martins...who hated it. Her rejection letter was scathing. This was not going to be the second book in that contract. And therein lies one of the many lessons I've learned--read your contracts carefully. A multi-book deal does not mean that the publisher is obliged to print whatever you send. Ruth did not care for the book, and so it was not going to press, at least not then and not with St. Martin's.My then agent, shopped it around a bit, but clearly I needed to get back to the drawing board and come up with something to fulfill my contract and so VULTURES AT TWILIGHT--at the time it was actually named DOILIES UNDER GLASS--landed in a drawer. To be fully accurate this is more of a shelf that over the years has taken on the look of a brick wall made out of tightly stacked manuscript boxes with titles of the enclosed, often with dates, written on the side in black sharpie. Time elapsed I came up with two more books for St. Martin's, which they did publish. Between books I'd dust of VULTURES AT TWILIGHT, give it a rewrite, send it out, read the rejection letters and then slide it lovingly back into my wall of unwanted books.At one point there was a near hit with a small specialty publishing house--they will go unnamed. They had a series of professional readers review the manuscript, it looked promising. They held onto VULTURES for eighteen months as an exclusive submission, before ultimately rejecting it. At least here, I could read the critiques from their readers, and came away with the conviction that indeed this book was publishable. I gleaned anything of value from the reviews and I re-worked the manuscript yet again. But with no likely buyers in site the options were limited. Do I self publish? Or...back onto the shelf?Here, I was a torn. Self publishing has become increasingly acceptable and affordable. Yet part of me clings to the notion that if no one in the "real" publishing world is ready to give it a go, maybe it needs to stay on the shelf. And while the differences between self-publishing and having a publisher bring out a book have become fewer there are still some big hurdles that the self-published author must consider. Most notably, how do you get a self-published book reviewed in the bigger publications? Not to mention I really do like that initial advance check. So VULTURES sat on the shelf until I got a call from my agent Al Zuckerman--and any author should be so lucky to have an agent like Al. He'd just had lunch with the editor at a gay-themed publishing house, and he'd brought up my name. He wondered if I was interested in writing a mystery or thriller series with a gay protagonist. Looking back at my wall of unwanted books, I spotted my very first manuscript--a rambling six-hundred page story of a conflicted gay surgeon. It's part love story, part action adventure, part mystery, part buddy book and total mess. It's quite possibly the worst thing I've ever written. So I told him I'd think about it, and while I was deep into another project gave it serious thought. Which is when it hit me. What if...What if the two women protagonists in VULTURES fell in love with another? They were already the best of friends, was it such a leap? As it stood, the book had no love line and this made tremendous sense. In discussing it with a gay friend of mine she thought it would work, but I'd need to make them a bit younger--and so I did. It took a solid two months to get a strong rewrite, and what emerged is a book that is a tremendous amount of fun. However....By the time it was ready to be submitted to the gay-themed publishing house, they'd gone through radical restructuring and the editor I'd written this for, had left. So back to the shelf...or so I thought. And this is where we get our happy ending, or maybe a fresh start. Unbeknownst to me, my agent had forwarded the new gay-themed VULTURES AT TWILIGHT to Severn House, a British independent who's published my last two hard covers. Sure enough they wanted it, but only as a series. If I could commit to at least a second book with my two heroines--Lil and Ada--it was a go. And now VULTURES AT TWILIGHT will be released in January 2012 in the U.K. and later this year in the U.S. with the e-version to follow a few months later. And the moral of this story, which is old and worth revisiting, persistence does pay, and often in unexpected and wonderful ways.

Published on January 01, 2012 13:24

The Wall of Unwanted BooksByCharlesAtkins" I have learned...

The Wall of Unwanted BooksByCharlesAtkins" I have learned, that if one advances confidently in thedirection of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life he has imagined, hewill meet with a success unexpected in common hours." --HenryDavid ThoreauDo all authorshave a drawer of unpublished books? Oris this just me? As I hit the finalpre-release weeks of one-such manuscript that will finally be published, thereare numerous lessons to be learned. Butas so much with writing it's more about the showing than the telling. So here's the story of how VULTURES ATTWILIGHT, which I wrote over a decade ago as a charming Connecticut cozy withtwo older female protagonists (for those not used to the term "cozy"it refers to a not-terribly gory murder mystery often set in a small town--AgathaChristie's Miss Marple is the archetype), will now come out as my first lesbian-themednovel.How does thishappen? Well, in the late 1990's Iachieved a major score--or more accurately my agent did--by landing a two-bookdeal with St. Martin's Press. My firstnovel--THE PORTRAIT--did well and so I set about crafting a follow upbook. My editor at St. Martin's was RuthCavin--a legend in the field--who at the time was in her early eighties. I was also working as a geriatric psychiatrist.My thought--write what you know--was todo a mainstream mystery but this time have heroines in their late seventies andearly eighties. I set the book in afictional Connecticut town that thrives off the systematic fleecing of itsolder residents as they downsize and die. It was a theme I knew well from my day job, and so I constructed adarkly comic mystery where the local antique dealers were getting bumped offone by one. I finished the manuscript,had a few people read it, did a rewrite or two, then off to my agent whosubmitted it to Ruth at St. Martins...who hated it. Her rejection letter was scathing. This was not going to be the second book inthat contract. And therein lies one ofthe many lessons I've learned--read your contracts carefully. A multi-book deal does not mean that thepublisher is obliged to print whatever you send. Ruth did not care for the book, and so it wasnot going to press, at least not then and not with St. Martin's.My then agent, shoppedit around a bit, but clearly I needed to get back to the drawing board and comeup with something to fulfill my contract and so VULTURES AT TWILIGHT--at thetime it was actually named DOILIES UNDER GLASS--landed in a drawer. To be fully accurate this is more of a shelfthat over the years has taken on the look of a brick wall made out of tightlystacked manuscript boxes with titles of the enclosed, often with dates, writtenon the side in black sharpie. Timeelapsed I came up with two more books for St. Martin's, which they did publish. Between books I'd dust of VULTURES ATTWILIGHT, give it a rewrite, send it out, read the rejection letters and thenslide it lovingly back into my wall of unwanted books.At one pointthere was a near hit with a small specialty publishing house--they will gounnamed. They had a series of professionalreaders review the manuscript, it looked promising. They held onto VULTURES for eighteen monthsas an exclusive submission, before ultimately rejecting it. At least here, I could read the critiquesfrom their readers, and came away with the conviction that indeed this book waspublishable. I gleaned anything of valuefrom the reviews and I re-worked the manuscript yet again. But with no likely buyers in site the optionswere limited. Do I self publish? Or...back onto the shelf?Here, I was a torn. Self publishing has become increasingly acceptableand affordable. Yet part of me clings tothe notion that if no one in the "real" publishing world is ready togive it a go, maybe it needs to stay on the shelf. And while the differences betweenself-publishing and having a publisher bring out a book have become fewer thereare still some big hurdles that the self-published author must consider. Most notably, how do you get a self-publishedbook reviewed in the bigger publications? Not to mention I really do like that initial advance check. So VULTURES saton the shelf until I got a call from my agent Al Zuckerman--and any authorshould be so lucky to have an agent like Al. He'd just had lunch with the editor at a gay-themed publishing house,and he'd brought up my name. He wonderedif I was interested in writing a mystery or thriller series with a gayprotagonist. Looking back at my wall ofunwanted books, I spotted my very first manuscript--a rambling six-hundred pagestory of a conflicted gay surgeon. It'spart love story, part action adventure, part mystery, part buddy book and totalmess. It's quite possibly the worstthing I've ever written. So I told himI'd think about it, and while I was deep into another project gave it seriousthought. Which is when it hit me. What if...What if the two women protagonistsin VULTURES fell in love with another? They were already the best of friends, was it such a leap? As it stood, the book had no love line andthis made tremendous sense. Indiscussing it with a gay friend of mine she thought it would work, but I'd needto make them a bit younger--and so I did. It took a solid two months to get a strong rewrite, and what emerged is abook that is a tremendous amount of fun. However....By the time itwas ready to be submitted to the gay-themed publishing house, they'd gonethrough radical restructuring and the editor I'd written this for, had left. So back to the shelf...or so I thought. And this is where we get our happy ending, ormaybe a fresh start. Unbeknownst to me,my agent had forwarded the new gay-themed VULTURES AT TWILIGHT to Severn House,a British independent who's published my last two hard covers. Sure enough they wanted it, but only as aseries. If I could commit to at least a secondbook with my two heroines--Lil and Ada--it was a go. And now VULTURES AT TWILIGHT will be releasedin January 2012 in the U.K. and later this year in the U.S. with the e-versionto follow a few months later. And themoral of this story, which is old and worth revisiting, persistence does pay,and often in unexpected and wonderful ways.

Published on January 01, 2012 13:24

December 30, 2011

...

Pearls to get You Puiblished As I prep for the release of my latest mystery--VULTURES AT TWILIGHT (Severn House)I came upon the following that I wrote for the now defunct Byline Magazine. It's all about the circuitous route to getting published. For me, this is all about the journey. The product is great, but how we get from point "A" to "B" is endlessly interesting--at least to me.

Furrballs & Pearls

Published in Byline Magazine as "Pearls that Get you Published"

Charles Atkins, MD

At four-thirty on Monday morning my cat throws up on The Chicago Manual of Style. This is not an omen, I reassure myself while cleaning it up and moving on to the morning's writing.

This time in the dark, while the rest of the world sleeps is when I work on novels, map out marketing strategies, answer emails from my agent, publisher, and publicist and hammer out the next column or article. These are words written when my brain is sparking to life under the kindling effects of the day's first cup of coffee. I never know where the words will lead me, but that's the excitement of writing while half asleep. At seminars when people ask me how I do it, I tell them that the secret is one of trusting the process and trying not to think too much. Don't think . . . write.

The Chicago Manual of Style, from here on marred with a small brownish stain, was a concession to my first agent who harangued me about my ignorance of the comma, "Buy a book, learn this and move on," she instructed me after receiving a three-hundred page manuscript with the same comma error repeated several hundred times,

My path to becoming a writer, and now a published author, is constructed of thousands of such mornings. I'd always wanted to write a book, but I'd never had the discipline, at least that's what I'd thought. Then came medical school, internship, and residency. Like eight years of boot camp they trimmed away all of my self-defeating habits with endless chapters to memorize followed by sleepless nights on-call. As a writer this discipline gives me the stamina to start a book on one day and finish it two to three months later. It's easy; each day is a thousand words, and don't skip days.

For the past couple years I've taken that writing to the market place. It's like jumping hurdles; each one brings me further along on the road. Pearls of wisdom, like luminous guideposts, help steer the process. It's a path that others have been down, but it's obscured and like those three-D images that appear when your eyes have sufficiently lost focus, the way to publishing is not always clear.

So what are the pearls?

The first is the basic, "writer's write." If you don't make time on a regular basis, it's not going to happen. The book won't get written, the screenplay you've been carrying around in your head won't make it to the printed page, and that groundbreaking article on the perfect orgasm will never make it to Cosmo. All of the successful writers I've encountered have a writing habit. It's best to put something down on paper everyday. Beyond that, like other habits, it's helpful to set up a regular time and place. The "when" is unimportant, but it should be daily.

The next pearl has to do with creativity, and how to avoid writer's block. My understanding of creative process is what allows me to sit down at my computer and have perfect faith that what I'm going to write will make sense, and have a beginning, a middle, and an end. As a psychiatrist, I have years of experience in seeing what shuts down creativity. The number-one killer of the muse is criticism. More often than not, it's internally generated. When I worked at Yale providing counseling to graduate students, I mentally divided them into two groups, those that whizzed through their theses without a problem and those that stalled out. I found that the stymied pre-docs were critiquing their work as they tried to create it. Invariably, they found it wanting; it wasn't good enough, or important enough, or what their supervisor wanted. These self-critical messages made it impossible to maintain the creatively mushy brain state that allows for interesting writing. This phenomenon was articulated for me at a creative writing seminar where the instructor encouraged us to write without editing. You can always edit later, but when it's time to do a rough draft—for me at least—the goal is to get it down on the page. If it's horrible I can always come back later and burn it.

So once you have a book written, how do you take it to market? The first piece of advice I received about publishing was from another physician author. He said, "Publish something small first, like a short story. It'll help build your credentials." He was right, but this also falls under the category of easier said than done. This became my introduction to rejection letters. Like most authors, I have received many of these. But rejection is not all bad. In amongst the form letters that assure me it's not my writing but simply, "does not meet our requirements at this time," are often helpful hand-written lines and paragraphs that let me know the real reason. Sometimes they steer me in the direction of another publication, and sometimes they clue me in to some key element that I need to incorporate. Maybe it's not a rejection letter after all, but a request for me to redo the piece in a manner more in keeping with the needs of the publication.

The first novel I wrote, a medically based-action-adventure-gay-themed-romantic-comedy thriller—now safely buried at the bottom of a drawer--received the following comment scrawled in the margin of a quarter-sheet form letter, "this is very unprofessionally formatted!!!!" I overlooked the three exclamation marks, told myself it was written by someone with the emotional maturity of a seventh grader, but I did take the message to heart. I bought a book on manuscript formatting. Sure, I'd double-spaced and laser printed, but my headers were wrong and all of the other conventions that separated the pros from the amateurs hadn't been observed. It was a great, albeit snotty, rejection letter, that helped me clear a hurdle.

A rejection letter, and the emotions it can fuel inside of us, is a potential pitfall for many would-be authors. I often hear people talking about the one or two times they submitted something and had it returned. They feel devastated and defeated. For some, they never clear this hurdle. Rejection has an annoying way of finding deep resonance within us. This is where some careful reminders can help us stay on track. Rejection is not personal and more often than not, the piece we sent really isn't right for the publication, or they have no space to print it, or they just ran a similar piece, or…When I started submitting articles and essays, I told myself that I was doing well if one in ten were accepted. That's now down to about one in three. Rejection letters are part of the business of writing, not to be confused with the art of writing; it's important to keep these separate. When I receive a rejection letter, I read it, file it in a folder, and forget about it—unless of course there's something handwritten that is useful. They're not something to stew over. And as another author told me about rejected pieces, "don't let them sit longer than twenty-four hours in the house." What he meant was, look the piece over, revise it if necessary, and then send it somewhere else.

The next step is critical; if you want to get a book published you need an agent. When I started I wasn't certain that this was necessary—haven't we all read such success stories? But then I met the ex-owner of a publishing house at a conference. He set me straight with two sentences, "Sure we read unsolicited manuscripts. But in the twenty years I ran **** Press we never once published one." It was a pearl not to be overlooked. I refocused my efforts, bought a book on the subject, wrote a succinct query letter, and got an agent.

Once I had representation the quality of rejection changed. No longer were manuscripts getting returned from editorial assistants, but they now came back with letters from senior editors and vice presidents. And then, wonder of wonders, we got a nibble, and then another, and then a two-book deal.

Now that I've entered the realm of the published—my first book came out last year and I have another coming out this fall--I face a new series of hurdles. But as before the pearls are dropping and I'm just the little piggy who's going to pick them up.

I now spend considerable time on marketing and publicity—a subject that fills many books and more in-depth articles. What I've learned is that I am ultimately responsible for how my books sell. New authors, in the age of cost-conscious, downsized publishing houses, must not depend on the marketing department. They will provide some basics, but on beyond that you're on your own. But here again, there's a road. I do a lot of talks, charity events, and every television and radio interview I can land. An author friend of mine refers to it as being a "publicity slut", where she's been on Oprah seven or eight times, I'm not about to argue.

As I look back through this article, I can't help but think, "what an awful lot of work this is." And that's the truth. I write because I have to, because it's a passion--a labor of love. As a psychiatrist, I am all too aware that most people move through life with no passion. So I pay attention to those things that nurture my craft. I practice daily, and listen to the wisdom of those that are further down the path; I find this works.

Bio—Charles Atkins is a practicing psychiatrist and author. He has written both fiction and non-fiction. His latest mystery--VULTURES AT TWILIGHT (Severn House) will be released in the UK in January 2012, and May 2012 in the US.

Published on December 30, 2011 14:15

December 26, 2011

Pearls to get You Puiblished

As I prep for the release of my latest mystery--VULTURES AT TWILIGHT (Severn House)I came upon the following that I wrote for the now defunct Byline Magazine. It's all about the circuitous route to getting published. For me, this is all about the journey. The product is great, but how we get from point "A" to "B" is endlessly interesting--at least to me.

Furrballs & Pearls

Published in Byline Magazine as “Pearls that Get you Published”

Charles Atkins, MD

At four-thirty on Monday morning my cat throws up on The Chicago Manual of Style. This is not an omen, I reassure myself while cleaning it up and moving on to the morning’s writing.

This time in the dark, while the rest of the world sleeps is when I work on novels, map out marketing strategies, answer emails from my agent, publisher, and publicist and hammer out the next column or article. These are words written when my brain is sparking to life under the kindling effects of the day’s first cup of coffee. I never know where the words will lead me, but that’s the excitement of writing while half asleep. At seminars when people ask me how I do it, I tell them that the secret is one of trusting the process and trying not to think too much. Don’t think . . . write.

The Chicago Manual of Style, from here on marred with a small brownish stain, was a concession to my first agent who harangued me about my ignorance of the comma, “Buy a book, learn this and move on,” she instructed me after receiving a three-hundred page manuscript with the same comma error repeated several hundred times,

My path to becoming a writer, and now a published author, is constructed of thousands of such mornings. I’d always wanted to write a book, but I’d never had the discipline, at least that’s what I’d thought. Then came medical school, internship, and residency. Like eight years of boot camp they trimmed away all of my self-defeating habits with endless chapters to memorize followed by sleepless nights on-call. As a writer this discipline gives me the stamina to start a book on one day and finish it two to three months later. It’s easy; each day is a thousand words, and don’t skip days.

For the past couple years I’ve taken that writing to the market place. It’s like jumping hurdles; each one brings me further along on the road. Pearls of wisdom, like luminous guideposts, help steer the process. It’s a path that others have been down, but it’s obscured and like those three-D images that appear when your eyes have sufficiently lost focus, the way to publishing is not always clear.

So what are the pearls?

The first is the basic, “writer’s write.” If you don’t make time on a regular basis, it’s not going to happen. The book won’t get written, the screenplay you’ve been carrying around in your head won’t make it to the printed page, and that groundbreaking article on the perfect orgasm will never make it to Cosmo. All of the successful writers I’ve encountered have a writing habit. It’s best to put something down on paper everyday. Beyond that, like other habits, it’s helpful to set up a regular time and place. The “when” is unimportant, but it should be daily.

The next pearl has to do with creativity, and how to avoid writer’s block. My understanding of creative process is what allows me to sit down at my computer and have perfect faith that what I’m going to write will make sense, and have a beginning, a middle, and an end. As a psychiatrist, I have years of experience in seeing what shuts down creativity. The number-one killer of the muse is criticism. More often than not, it’s internally generated. When I worked at Yale providing counseling to graduate students, I mentally divided them into two groups, those that whizzed through their theses without a problem and those that stalled out. I found that the stymied pre-docs were critiquing their work as they tried to create it. Invariably, they found it wanting; it wasn’t good enough, or important enough, or what their supervisor wanted. These self-critical messages made it impossible to maintain the creatively mushy brain state that allows for interesting writing. This phenomenon was articulated for me at a creative writing seminar where the instructor encouraged us to write without editing. You can always edit later, but when it’s time to do a rough draft—for me at least—the goal is to get it down on the page. If it’s horrible I can always come back later and burn it.

So once you have a book written, how do you take it to market? The first piece of advice I received about publishing was from another physician author. He said, “Publish something small first, like a short story. It’ll help build your credentials.” He was right, but this also falls under the category of easier said than done. This became my introduction to rejection letters. Like most authors, I have received many of these. But rejection is not all bad. In amongst the form letters that assure me it’s not my writing but simply, “does not meet our requirements at this time,” are often helpful hand-written lines and paragraphs that let me know the real reason. Sometimes they steer me in the direction of another publication, and sometimes they clue me in to some key element that I need to incorporate. Maybe it’s not a rejection letter after all, but a request for me to redo the piece in a manner more in keeping with the needs of the publication.

The first novel I wrote, a medically based-action-adventure-gay-themed-romantic-comedy thriller—now safely buried at the bottom of a drawer--received the following comment scrawled in the margin of a quarter-sheet form letter, “this is very unprofessionally formatted!!!!” I overlooked the three exclamation marks, told myself it was written by someone with the emotional maturity of a seventh grader, but I did take the message to heart. I bought a book on manuscript formatting. Sure, I’d double-spaced and laser printed, but my headers were wrong and all of the other conventions that separated the pros from the amateurs hadn’t been observed. It was a great, albeit snotty, rejection letter, that helped me clear a hurdle.

A rejection letter, and the emotions it can fuel inside of us, is a potential pitfall for many would-be authors. I often hear people talking about the one or two times they submitted something and had it returned. They feel devastated and defeated. For some, they never clear this hurdle. Rejection has an annoying way of finding deep resonance within us. This is where some careful reminders can help us stay on track. Rejection is not personal and more often than not, the piece we sent really isn’t right for the publication, or they have no space to print it, or they just ran a similar piece, or…When I started submitting articles and essays, I told myself that I was doing well if one in ten were accepted. That’s now down to about one in three. Rejection letters are part of the business of writing, not to be confused with the art of writing; it’s important to keep these separate. When I receive a rejection letter, I read it, file it in a folder, and forget about it—unless of course there’s something handwritten that is useful. They’re not something to stew over. And as another author told me about rejected pieces, “don’t let them sit longer than twenty-four hours in the house.” What he meant was, look the piece over, revise it if necessary, and then send it somewhere else.

The next step is critical; if you want to get a book published you need an agent. When I started I wasn’t certain that this was necessary—haven’t we all read such success stories? But then I met the ex-owner of a publishing house at a conference. He set me straight with two sentences, “Sure we read unsolicited manuscripts. But in the twenty years I ran **** Press we never once published one.” It was a pearl not to be overlooked. I refocused my efforts, bought a book on the subject, wrote a succinct query letter, and got an agent.

Once I had representation the quality of rejection changed. No longer were manuscripts getting returned from editorial assistants, but they now came back with letters from senior editors and vice presidents. And then, wonder of wonders, we got a nibble, and then another, and then a two-book deal.

Now that I’ve entered the realm of the published—my first book came out last year and I have another coming out this fall--I face a new series of hurdles. But as before the pearls are dropping and I’m just the little piggy who’s going to pick them up.

I now spend considerable time on marketing and publicity—a subject that fills many books and more in-depth articles. What I’ve learned is that I am ultimately responsible for how my books sell. New authors, in the age of cost-conscious, downsized publishing houses, must not depend on the marketing department. They will provide some basics, but on beyond that you’re on your own. But here again, there’s a road. I do a lot of talks, charity events, and every television and radio interview I can land. An author friend of mine refers to it as being a “publicity slut”, where she’s been on Oprah seven or eight times, I’m not about to argue.

As I look back through this article, I can’t help but think, “what an awful lot of work this is.” And that’s the truth. I write because I have to, because it’s a passion--a labor of love. As a psychiatrist, I am all too aware that most people move through life with no passion. So I pay attention to those things that nurture my craft. I practice daily, and listen to the wisdom of those that are further down the path; I find this works.

Bio—Charles Atkins is a practicing psychiatrist and author. He has written both fiction and non-fiction. His latest mystery--VULTURES AT TWILIGHT (Severn House) will be released in the UK in January 2012, and May 2012 in the US.

Furrballs & Pearls

Published in Byline Magazine as “Pearls that Get you Published”

Charles Atkins, MD

At four-thirty on Monday morning my cat throws up on The Chicago Manual of Style. This is not an omen, I reassure myself while cleaning it up and moving on to the morning’s writing.

This time in the dark, while the rest of the world sleeps is when I work on novels, map out marketing strategies, answer emails from my agent, publisher, and publicist and hammer out the next column or article. These are words written when my brain is sparking to life under the kindling effects of the day’s first cup of coffee. I never know where the words will lead me, but that’s the excitement of writing while half asleep. At seminars when people ask me how I do it, I tell them that the secret is one of trusting the process and trying not to think too much. Don’t think . . . write.

The Chicago Manual of Style, from here on marred with a small brownish stain, was a concession to my first agent who harangued me about my ignorance of the comma, “Buy a book, learn this and move on,” she instructed me after receiving a three-hundred page manuscript with the same comma error repeated several hundred times,

My path to becoming a writer, and now a published author, is constructed of thousands of such mornings. I’d always wanted to write a book, but I’d never had the discipline, at least that’s what I’d thought. Then came medical school, internship, and residency. Like eight years of boot camp they trimmed away all of my self-defeating habits with endless chapters to memorize followed by sleepless nights on-call. As a writer this discipline gives me the stamina to start a book on one day and finish it two to three months later. It’s easy; each day is a thousand words, and don’t skip days.

For the past couple years I’ve taken that writing to the market place. It’s like jumping hurdles; each one brings me further along on the road. Pearls of wisdom, like luminous guideposts, help steer the process. It’s a path that others have been down, but it’s obscured and like those three-D images that appear when your eyes have sufficiently lost focus, the way to publishing is not always clear.

So what are the pearls?

The first is the basic, “writer’s write.” If you don’t make time on a regular basis, it’s not going to happen. The book won’t get written, the screenplay you’ve been carrying around in your head won’t make it to the printed page, and that groundbreaking article on the perfect orgasm will never make it to Cosmo. All of the successful writers I’ve encountered have a writing habit. It’s best to put something down on paper everyday. Beyond that, like other habits, it’s helpful to set up a regular time and place. The “when” is unimportant, but it should be daily.

The next pearl has to do with creativity, and how to avoid writer’s block. My understanding of creative process is what allows me to sit down at my computer and have perfect faith that what I’m going to write will make sense, and have a beginning, a middle, and an end. As a psychiatrist, I have years of experience in seeing what shuts down creativity. The number-one killer of the muse is criticism. More often than not, it’s internally generated. When I worked at Yale providing counseling to graduate students, I mentally divided them into two groups, those that whizzed through their theses without a problem and those that stalled out. I found that the stymied pre-docs were critiquing their work as they tried to create it. Invariably, they found it wanting; it wasn’t good enough, or important enough, or what their supervisor wanted. These self-critical messages made it impossible to maintain the creatively mushy brain state that allows for interesting writing. This phenomenon was articulated for me at a creative writing seminar where the instructor encouraged us to write without editing. You can always edit later, but when it’s time to do a rough draft—for me at least—the goal is to get it down on the page. If it’s horrible I can always come back later and burn it.

So once you have a book written, how do you take it to market? The first piece of advice I received about publishing was from another physician author. He said, “Publish something small first, like a short story. It’ll help build your credentials.” He was right, but this also falls under the category of easier said than done. This became my introduction to rejection letters. Like most authors, I have received many of these. But rejection is not all bad. In amongst the form letters that assure me it’s not my writing but simply, “does not meet our requirements at this time,” are often helpful hand-written lines and paragraphs that let me know the real reason. Sometimes they steer me in the direction of another publication, and sometimes they clue me in to some key element that I need to incorporate. Maybe it’s not a rejection letter after all, but a request for me to redo the piece in a manner more in keeping with the needs of the publication.

The first novel I wrote, a medically based-action-adventure-gay-themed-romantic-comedy thriller—now safely buried at the bottom of a drawer--received the following comment scrawled in the margin of a quarter-sheet form letter, “this is very unprofessionally formatted!!!!” I overlooked the three exclamation marks, told myself it was written by someone with the emotional maturity of a seventh grader, but I did take the message to heart. I bought a book on manuscript formatting. Sure, I’d double-spaced and laser printed, but my headers were wrong and all of the other conventions that separated the pros from the amateurs hadn’t been observed. It was a great, albeit snotty, rejection letter, that helped me clear a hurdle.