Phil Halton's Blog, page 2

June 23, 2023

On Algorithms and Genre

It’s generally accepted that in modern literature there are two broad kinds of fiction – literary fiction and genre fiction. While it is often said that the difference is that genre fiction is principally concerned with plot and convention, while literary fiction elevates character and theme, this is not the only difference. The sub-text, sometimes said aloud, is that literary fiction is art, while genre fiction is mere entertainment. One is to be savoured, the other consumed.

There is such a stark divide between the two that while many writers learn the conventions that set them apart, and divide genre fiction into a myriad of different parts, few people question the difference or recognize its origin. It’s also important to ask an even more important question – in its current incarnation, who does this division serve?

Classic western literature began in ancient Greece, where three broad genres were recognized. The epic poem was the first, and oldest, form of the three, epitomized by the Iliad and the Odyssey. The other two genres were forms of drama – the comedy and the tragedy. The characteristics of these separate genres were defined in Aristotle’s Poetics, the earliest known example of literary criticism. Most importantly, though, none of the three forms of literature were held to be above the other – they were different, but neither better nor worse.

Other genres came to be defined over time, though the modern division is a very recent innovation. The “novel” itself was first seen as its own genre, only appearing in the early 17th century (Miguel de Cervante’s Don Quixote). The novel as a genre became more popular, and more possible, with the invention of mass-produced books that were affordable, and meant to entertain the masses.

The modern genres that are more commonly recognized today – mystery, science fiction, fantasy and others – are divisions that only came into being in the early 20th century, and in many cases, did not become widely read until the latter half of that century. With their origins in magazines, they began as distinctly popular culture, differentiated from “high brow” literature.

The last twenty years have seen genre morph once again, driven much as the early novel was, but technology. Online sales platforms, as well as sites such as Wattpad, have created an economic incentive for the hyper segmentation of genre. While it could be argued that the creation of genres to categorize fiction served the consumer by giving them ready access to material that interested them, the new approach to defining genre is driven by purely by marketing, with negative effect.

Amazon as a platform is not only aware of all your browsing and your purchases, but also highly detailed information about how you consume e-books that you download. They are able to analyze how quickly you read a book, whether you finish it or not, and where you stop. All of this analysis is ostensibly to serve the consumer, by feeding the recommendation algorithms to offer you other choices that you will enjoy. But in order to do so, books have become categorized in ever more narrow segments, well below those shown on the website itself. Once you start to read (and assumedly enjoy) Young Adult-mermaid-vampire-mysteries, you are almost certain to only be shown ads for more of the same. This isn’t a problem if one assumes that this is all you want to read, or that writers want to produce material that naturally falls into a tight categorization. What’s critical to remember, however, is that unlike the division into genre that occurred in magazines of the 1920s and 30s, this segmentation isn’t being driven by the tastes of consumers directly, but by the needs of the algorithms that serve up recommendations. And this is the issue that I have with the modern approach to the question of genre.

Amazon has become not only the largest online bookseller, but also one of the largest publishers in the world. This centralization of power in the hands of one company has allowed them to reshape the book industry in ways that they do not even need to publicly reveal. One example of how they have done this is through the hyper-segmentation of genre. They have created over 13,000 different categories for books, more than are humanly useable. And because they know not only what books you buy, but in the case of e-books, which you actually read – as well as when, how fast, in what order and many other metrics – this information is coupled with their very precise categorization of genre to serve up exactly what they think you will want to read.

You might ask, “Why is this a problem?” If readers are better able to find books that they like at affordable prices, who is being harmed? My concern is simple.

The hyper-segmentation of genre has leaked out of the realm of AI and into the common understanding of human authors. Now, in order to find an under served niche audience, or to find a means to achieve a “#1 Amazon Bestseller,” authors are also conceiving of their works in artificially narrow terms. Gaming the Amazon system has created an impetus to turn all fiction into genre fiction, making general fiction – or anything else that does not fit into an easy category – seemingly unsellable.

Storytelling is an inherently human activity, and in fact is one of the few things that truly makes humans unique on Earth. I don’t believe that allowing algorithms to drive how we relate to stories serves humans well at all.

(As an aside, for someone who eschews being pigeonholed in any single genre, and undoubtedly causes the Amazon algorithms the AI version of a headache, take a look at the body of work of China Mieville, one of whose books I reviewed.)

The post On Algorithms and Genre appeared first on Phil Halton | Writer | Book Coach.

August 30, 2021

Women are the Price of Peace in Afghanistan

The rights and role of women in society has long been a thorny issue in Afghanistan, well before the Taliban regime that brought international interest to the subject. It’s useful to understand the history of the issue as a driver of conflict to also understand what is happening today. While the issue of women’s rights might seem like a modern one in the context of Afghanistan, it is actually one with deep roots.

First attempts at modernization Queen Soraya

Queen SorayaThe first attempt to secure equal rights for women was in 1919. Amanullah Amir had just ascended to the throne after the assassination of his father, and he saw himself as a modernizer, “Afghanistan’s Ataturk.” He enacted sweeping policies that would bring women fully into public life, creating an immediate and negative reaction in most of the country. His policies resulted in a series of brutally violent uprisings that lasted for a decade.

Interference by the central government into the question of who, how and at what age women could marry caused outrage. These questions had until that point been the purview of local religious and traditional authorities, outside the scope of the government’s power. Similarly, policies to allow women to pursue higher education, following western curriculums, alongside their male colleagues or even at universities outside of the country, were deeply unpopular outside a small circle of elites. The appointment of the Amir’s wife, Soraya, as the Minister of Education was seen as an outrageous break with tradition. The end result of Amanullah’s attempt at modernization was the death of thousands of people in a decade of fighting, his overthrow and exile, and a return to more conservative rule.

The Communist EraWomen only again regained their rights a half-century later when the government adopted communist ideology. The mujahideen uprising commonly seen as opposing the Soviet invasion actually predated it by several months, and was again based more in opposition to the issue of government interference in the personal lives of citizens than anything else. The issues that led to open rebellion in 1979 were much the same as those in 1919, though the presence of foreign soldiers further exacerbated the situation. In both cases, however, the rebels wrapped themselves in the mantle of religious rightousness, declaring a jihad against the government.

This uprising also lasted over a decade and eventually overthrew the government, although the disparate rebel groups were unable to turn their military success into a political victory and create a stable successor administration. Infighting between the rebel groups led to such chaos and destruction that when the Taliban emerged to oppose them, many Afghans saw this new group as a reasonable alternative to the anarchy they were experiencing.

Taliban RuleAs the Taliban gained control over the country, province by province, as often by bribery and guile as by combat, there was often no outcry over their repressive view of the correct role of women. In the predominantly Pashtun south they were not imposing some new religious or cultural regime, but merely enforcing what were already common cultural practices. The burkha was already ubiquitous in Pashtun communities. Taliban policies were not alien ones, but simply reflected the thinking of rural, conservative Pashtuns.

Real opposition to the Taliban‘s policies on women’s rights first occurred when they imposed it on relatively cosmopolitan cities such as Herat and Kabul, where women had become accustomed to having an active role in public life, pursuing education and employment alongside men. Similarly, the Taliban were opposed in places such as the Hazarajat where a rough sort of egalitarianism is a long-standing cultural tradition. In these places, the Taliban were as alien a force as foreign invaders, often not sharing a common language or culture with those they ruled over.

Post 2001When the Taliban were deposed by military intervention in 2001, the western-style government that replaced them guaranteed the rights of women. In fact, their policies mirrored those of the communist regime more than any other previous administration. As before, this was welcomed by some elements in society and despised by others. Opposition to the government’s interference in family life began to grow again. Widespread corruption undercut the perception of the government as a positive force in people’s lives. The Taliban, although utterly defeated by the Western invasion, took only a few years in this environment to rebuild into a serious threat.

Successive Canadian governments have used the idea of fighting for women’s rights to justify and even sell the Canadian military presence in Afghanistan to a domestic audience. But despite twenty years of relatively modern, western-style government, the burqa has remained an ubiquitous sight even in the streets of the enlightened capital. This is true despite the fact that 75% of the Afghan population is under the age of 25, and so has no memory of the Taliban regime.

While there are Afghan women who have pursued higher education, become politicians, run businesses or humanitarian organizations, wore their hair loose and drove cars, they are both exceptional and the exception. No matter how many inspiring stories of womens’ successes in Afghanistan one reads in the newspaper, most Afghan women have remained cut off from public life. The reasons vary – whether due to their own religious or cultural views, the demands of their family, their personal preferences or simply out of fear for their safety. Despite pockets of progress, the lot of the vast majority of women in Afghanistan (particularly widows and those living in rural areas) has not improved much in the past two decades despite intense Western interest in their welfare.

Bargaining for PeaceDuring the “peace” negotiations undertaken by the Trump administration, no known demands regarding respect for the rights of women were made. During the subsequent negotiations between the Afghan government and the Taliban, there were several female negotiators who spoke strongly in favour of ensuring the rights of women. But the recent Taliban military victory has meant that all this talk has come to naught.

In the current negotiations between the Taliban and what remains of the Afghan government, the role of women has been relegated to the level of an unimportant detail. The Taliban will not accept a prominent role for women in Afghan society and the former government officials representing the citizens of the country are not willing to insist upon it. The truth of the matter is that there isn’t widespread support in Afghan society for the equality of women. The international community will make much noise in support of women but are taking no actions to ensure that women will be treated equally or even fairly.

Understandably, after decades of war, there is a strong desire throughout society for the fighting to end. But the peace that seems achievable isn’t an equal one. The Taliban will once again impose heavy restrictions on the lives of women, and most of Afghan society will acquiesce. The grassroots organizations in support of women’s rights are being abandoned. There are no power brokers left in Afghanistan willing to stand up for the rights of women, and without women at the negotiating table, these rights are too easily bargained away or simply ignored.

While it is long past time for the fighting in Afghanistan to end, we should be aware of the cost involved. It seems that women will be the price of peace in Afghanistan. Is this a cost that we are willing to pay?

The post Women are the Price of Peace in Afghanistan appeared first on Phil Halton | Literary Fiction Writer.

July 10, 2021

An Interview with Chris Wattie

Chris Wattie is a veteran, journalist and writer whose book Contact Charlie: The Canadian Army, The Taliban and the Battle that Saved Afghanistan was based on his experiences as an embedded journalist in Kandahar in 2006.

Phil: What first attracted you to becoming a journalist?

Chris: I’ve always believed that journalism is as much a personality disorder as a profession.

Kind of like being a writer!

Exactly! You don’t do it because you want to; you do it because you have to. I started writing for student papers when I was at University of Saskatchewan (The Sheaf), and discovered it was a) fun; b) a potential source of work in summers and post graduation; and c) most importantly, a great way to meet women. I was an English/History major, so it’s not like I could go door-to-door selling people my analysis of the trochaic level of allegory in Canterbury Tales. I transferred to Carleton after one year, and although I briefly considered taking Journalism there, I stayed with the English/History program – mainly because the people I met who were in journalism were almost exclusively middle-class, imitation preppy, tight asses. This was absolutely the right decision: I use my English and certainly my history degree almost every day. Journalism can be taught to anyone who can form clear sentences in a matter of a week or two, and there are a LOT of people working in journalism these days who couldn’t form a clear sentence if you put a gun to their heads.

I agree that a liberal arts education isn’t meant to be vocational training. It’s meant to give you the skills (critical thinking, persuasive writing, etc.) that you apply to some other field. Journalism seems like a way to take those skills and apply them in an immediate way to things that are happening in society.

Very much so. But there’s also an element of compulsive voyeurism: an interest or need in getting a front-row seat to history. I liked being a ground level spectator to things happening: whether it was the mission in Afghanistan or the 9/11 attacks or the Bernardo trials or the South Asian Tsunami in 2006 or whatever. But I liked almost as much the work of processing these experiences or events and portraying them in a way that most people would understand and hopefully relate to. Not all journalists share that second trait, which explains some of the appallingly dreadful writing you see in the media. As George Orwell said, people assume “yellow journalism” is committed by talented writers stooping to make ends meet; in fact, it’s produced by people doing their very best work. When I was embedded, I would wrestle with how best to write stories that would convey what it’s like to be on patrol in a place like Kandahar, for instance. Not many of my colleagues did – it was much easier (and safer) to stay on Kandahar Air Field (KAF) and cover news releases or conferences from the HQ, and of course the all-too-frequent ramp ceremonies. Getting out with the soldiers could be an emotionally draining process, and at times hugely difficult, but also incredibly rewarding. Almost – but not quite – rewarding enough to make up for all the other bullshit that goes on in the media industry.

I see how your education in English/History impacts your approach to journalism, but how does your experience in journalism impact your other writing?

After 20 plus years of writing 100- to 400-word stories in I find it hard as hell to write long. News writing (at least the way I was taught) is a pretty tightly constrained writing style: third person impersonal; inverted pyramid structure; limited or no adjectives, adverbs, or description. As a result, I’m deeply awkward about writing dialogue or long descriptive passages – which may be a good thing in some ways. My tendency is to devolve into long, pretty boring descriptions of scenery, people, etc. which I have to guard against. One thing I’ve taken away from journalism is that less is more. But there’s less and then there’s LESS: it’s hard to sell a publisher on a 1,000 word “novel.” So really, the biggest challenge for me was writing more than a few hundred words: it was very hard for me to avoid repeating words, or phrases in longer-form writing. One of my first editors/mentors in the business was a Canadian Press desk editor named Wally Krevenchuk: a great editor, with a painfully dry sense of humour and sardonic wit. When I was working for him in CP Edmonton, and taking too long to write a story about police busting another crack house (for instance), Wally’s favourite words of encouragement (delivered in a voice aged by decades of whisky and cigarettes) were: “Hey Dostoyevsky: when’s that novel coming out in paperback?”

Ouch! There is a lot of critique in those eight words!

I didn’t take it personally. Wally was a lovely guy, and a great newspaperman. He passed away a few years ago and there are few like him still in the business of journalism. It’s a measure of his success at teaching that I still haven’t quite gotten over the resulting flinch reaction to keep thing short and to the point. Easier to do with a cop brief than fiction.

That said, there is an awful lot of successful fiction out there that could use a heavy structural edit. I can point to a few authors whose work was commercially successful enough that they could dictate the length of their work to the publisher and opted to write novels that weigh in close to 200,000 words. And while that might work in some cases, it certainly doesn’t work in all cases. It’s almost as if they are too important, or it’s too much bother, to have to write concisely.

God yes! The best recent example I can think of (John Milton not being really what I’d call recent) is G.R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones series. Obviously, it’s been a hugely successful series, even before the Netflix specials, and more power to him. But he desperately needs an editor: there were so many parallel plotlines, characters, and frankly fluff that I go too frustrated to finish them. I’ve heard theories that this sort of overly complex writing is the fallout from the advent of the computer. Writers can move plots and subplots around pretty easily thanks to MS Word, but if you have to write on a manual typewriter, or – heaven forfend – by hand, then you have built-in incentive to keep it down to a reasonable length and complexity.

I’m curious to know what was it like being an embedded journalist while doing the research behind “Contact Charlie”?

It was simultaneously incredibly rewarding and hugely frustrating. I was embedded when the whole concept was still new to the Canadian Armed Forces, and as a result the bureaucracy in Ottawa hadn’t quite gotten their heads around how to “manage” embedded reporters. So I got levels of access to the officers and men of Task Force Orion that later embeds never really did – partly because I worked at developing relationships and a rep among the troops, but also because nobody in the Department of National Defence Public Affairs machinery (let alone the Prime Minister’s Office/Privy Council Office) realized how much access I had to the troops and what that meant in terms of news stories. After the first year or two of embedded reporting, Public Affairs and Privy Council Office, even Prime Minister’s Office, started directly attempting to control reporters with the battlegroups: to the point that by the end of the mission, decisions on whether or not reporters were allowed to go on section-level presence patrols were being made in Ottawa. That’s literally the central command reaching down to make decisions at the sergeant level. But until then, it was just an incredible privilege to be able to spend time with soldiers on an actual war-fighting operation. The guys were – as you’d expect – unbelievably helpful and accommodating: they did more for the reputation of the CAF than the Public Affairs branch has done over its entire history.

The war in Afghanistan definitely brought out the tendency to try to control everything from on high, whether that was tactical operations or the flow (and tone) of information. It’s contrary to Canadian military doctrine, and common sense, but there is some aspect of the war that seemed to affect the whole institution that way. And no amount of evidence that showed it wasn’t working seemed to sway anybody. It must have been frustrating for you.

It was frustrating because I didn’t get to stay with the troops 100% of the time: which would have been my preference. And not only because I found most of the other journalists irritating at best. I estimate we were out with the soldiers about half the time, at the most. The rest of the time we were cooling our heels in the Media Tent at KAF. Some of that was due to the Public Affairs Officers trying to manage – they would say “balance” – the access reporters from different outlets got. They were trying, in my opinion, to micro-manage reporters’ access to the soldiers, whereas it all seemed pretty simple to me: assign a reporter to a subunit, or rotate them among 2 or 3 subunits, and leave them alone. That’s pretty much what was done in Kabul in 2004, and it worked well.

I was in Afghanistan at various points over that decade, and looking back, I am amazed at how loose everything was near the start, and how over time institutions and rules grew. This wasn’t just in the military – it’s just as true of the Afghan government and Afghan society.

Very true. Gen. Hillier tells a story about how he was able to ram through some key spending and acquisition programs through the system in record time at the beginning of the mission (the Chinooks, new trucks, Leopard 2 tanks, for eg). After a couple of these successes, the rest of the bureaucracy – according to Hillier – realized DND was being successful and started applying the institutional brakes to procurement, largely out of jealousy. But a lot of the issues with the embed program can be blamed on the media, historically not a well-managed industry. Getting an embed spot became a sort of “door prize” for some outlets; a way of rewarding their favourite reporters by letting them play war correspondent for a few weeks. That’s how Michelle Lang, the Calgary Herald reporter killed by an IED in 2009, wound up in Afghanistan: she was a health care reporter. As a result, journalists with no background, understanding, or often even interest in the military wound up covering a shooting war in one of the most dangerous countries on earth. Naturally, they tended to get scared and listened to their editors in Toronto or Ottawa who told them to stay close to Kandahar Airfield “in case something happened.” The something of course being a Canadian soldier getting killed. People with foreign reporting experience realized that this was a trap: you wound up spending all your time writing pretty much what the military and political leadership fed you instead of going out on the ground and reporting what the troops were actually doing. It became deathwatch journalism.

You saw that in the military as well, as people rushed into theatre near the end to get the medal and not miss out on the war. It’s such a strange, but very human, reaction to the whole thing.

There were exceptions to this of course: Murray Brewster of Canadian Press being the best example. But they were very much exceptions. All in all, the embedding program turned out to be pretty much a textbook example of how to screw up a public affairs/StratCom messaging program. It was a recipe for losing support for the mission, in much the same way the “Five O’Clock Follies” in Vietnam turned journalists and eventually the American public against the war in Vietnam.

After 2004 in Kabul, when I was one of the first embedded Canadian reporters with the Canadian mission, I told a Public Affairs Officer I knew that the embedding program was such a brilliant idea that even the Canadian Armed Forces couldn’t screw it up. Turns out I underestimated the institution’s ability to screw up.

Well, add it to the list of things that gotten screwed up in the past year alone. Society has really shifted in a number of ways since March 2020. Has the pandemic changed your view on the role of the artists/writers within society?

You always make me think about things I wouldn’t normally think about… please cut it out.

I can make no promises…

Seriously, it seems to me that with all of us spending a year or more under lockdown of one kind or another, it’s more important than ever for writers to provide or support the kind of ties that bind us together as a society. Yet, judging from the news we’re more divided than ever: although as always, it’s far, far worse south of the border than it is here.

That’s interesting. I hadn’t thought of what artists owe society, essentially creating the stories (in whatever form) that lift us up and build a cohesive narrative about who we are and why we’re better together. The counter-narrative seems to have the upper hand in some parts of the world, though to a lesser degree here in Canada.

It reminds me a lot of what we were doing in Information Operations in Iraq and Syria: narratives are the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and where we come from. And they can be powerful things: ISIS had a narrative, that was well-constructed and appealing to a lot of disenfranchised Sunnis in the Middle East, and indeed around the world. And that was powerful enough to launch a particularly brutal war that’s still being fought.

Canada’s issue is that we haven’t quite figured out what our narrative is – Vimy Ridge? The War of 1812? Bilingualism and multiculturalism? Or is it (my best guess) what Northrop Frye called the great question of Canadian literature: “Where is here?”

I don’t think we’ve really answered that question, and all the questions and issues that follow. And I don’t think that’s necessarily the fault of Canadian writers: our means of distributing our work are paradoxically more open than they’ve ever been (blogs, social media, web zines, etc.) but also have more fractured and smaller audiences than ever. So as usual, it’s difficult to make a living as a writer: probably more difficult than it has been for a long time.

But it’s also fair to say that Canadian writers haven’t exactly risen to the challenge, to overcome these distribution issues and speak to the issues that we face, and the things that tie us together as Canadians: social distancing notwithstanding. I think there are reasons for this, including the trend in Canadian writing/literature to become increasingly self-referential, self-congratulatory, and out of touch with most Canadians’ daily lives. Most of our self-proclaimed literary elite seem consumed with things that James Carville dismissed (and rightly so) as “faculty lounge jargon.”

I would tend to agree with you, and I think that’s the case of small groups everywhere. We become consumed with the matters right under our noses. The literary set in Canada is a pretty small demographic, and so can be insular, though I’m not sure that its really intentional.

Part of the solution is to get a more diverse set of people telling a greater diversity of stories. What advice would you give to other writers looking to make a full-time job of it?

Seek out experiences, by which I mean real experiences. Go out in the bloody world and see what’s actually happening. There’s far too much navel-gazing in the literary world, particularly in CanLit. Nobody cares about the internal monologue of a 20-something, sexually ambiguous, vegan, anarcho-syndicalist moaning about their struggle against online colonialism. Or whatever. Now a vegan anarcho-syndicalist who solves crimes – that I would read.

I’d suggest that some people might be interested in that book, actually! But what we need is a wider set of experiences represented in our literature, that has space for that inner-monologue book alongside lots of other things as well. And that the best education for a writer isn’t in a workshop somewhere, but out in the real world living life.

This is not to say everything Canadian writers produce has to be detective novels, or thrillers, or plot-driven mysteries. But it has to be about something real; something relevant. Joe Boyden’s Three Day Road is a great example: he was writing fiction based on the very real experiences of aboriginal soldiers in the First World War, and what they went through when they returned home. Timothy Findlay’s The Wars is another great read: although I am clearly biased towards war novels.

That is a great example, as I think it appeals to different audiences and represents an important part of Canadian history that has otherwise been overlooked. And Boyden didn’t have to have first-hand experience of the First World War to write it – he could draw on his other experiences instead.

Exactly. Personally, I’d love to read what Boyden makes of the Afghan mission, although I would guess that’s not something he’s particularly interested in writing about. But the best way – really the only way – to get the kind of experience that leads to such great writing is to go out and see the world, look at what’s happening through a lens other than your iPhone or social media. I’m a big believer in digging down into the nitty gritty level of what’s happening, and you can only see that if you get out and look for yourself.

But at a certain point you need to buckle down and do the work. Being a journalist gives you lots of experience with deadlines, and the discipline to write even when you don’t feel like it. Are there any new projects that you’re working on now?

I’m working on a few ideas for a science fiction novel, inspired by Joe Haldeman’s Forever War, but where Haldeman was talking about Vietnam, obviously I’d be talking about Afghanistan.

That is a book I would read.

This was the first war Canada fought since Korea, and the longest war in our history, and it doesn’t seem to have made much of an impact on the national narrative. This is mind-boggling to me. It’s true that it takes time for these things to emerge: witness the gap between the end of the Vietnam War and the emergence of movies and books that really dug into that conflict and its impact on the U.S. So my thinking is that the way around this is to write about Afghanistan without writing about Afghanistan, in the same way that M*A*S*H wasn’t really about Korea and Forever War wasn’t really scifi. But it’s coming slowly so far… it turns out that writing a roman a clef is harder than it looks.

It’s not easy to write something simple! That is my experience, at least. The war in Afghanistan has shaped my writing in a lot of ways, even when it’s not the subject of my work directly. It’s weird to think that my experiences in Afghanistan were really the formative ones of my adult life, but it seems to be true.

It’s interesting to me that the war in Afghanistan (and Iraq) don’t seem to have been the spark for a whole new generation of writers in the way that the First and Second World Wars were. Perhaps veterans have other outlets for their messages. But there is something to the fact that, throughout history, being a writer and being a soldier have gone hand in hand.

There’s a long line of soldiers/writers going as far back as Aeschylus – basically, the father of all playwrights – and more recently Churchill or Hemmingway. But that seems to have fallen off in the past few decades, with a few notable exceptions like Sebastian Junger. I think that’s partly because of the nature of the military experience and the military’s role in post-modern societies – we’re very much a tiny minority, even a warrior caste if you will, within most Western democracies. Where the experience during the First and Second World War was mass enlistment and a full societal commitment to war, since the 1980s most people in Canada or the U.S. have only experienced wars on TV – in the Balkans, Iraq, or Afghanistan. The number of soldiers fighting these wars is an ever-shrinking percentage of the population and warfare just hasn’t been part of most people’s experience. There’s also been a growing disconnect between the “arts” community and the military – most self-proclaimed artists (including authors) tend to define themselves as vaguely left wing, if not aggressively anti-military.

That disconnect is true. Mass conscription meant that having been a soldier (or sailor or aviator) was a more common experience, and so harder to see as an “other.”

So that leaves Canadian readers looking for writing (fiction or non-fiction) about Afghanistan with either soldiers’ memoires or semi-autobiographical books by journalists – neither of which tend to be particularly well-written. Memoirs by soldiers can be very hit or miss in terms of quality – John Conrad’s What The Thunder Said is a good example of the better class of these – and aren’t particularly literary. Books by journalists can be painful to read: Christie Blatchford’s Fifteen Days for instance is not a particularly good read although I loved Christie dearly; and the less said about Patrick Graham’s Afghan Luke the better.

And don’t get me started on Hyena Road…

Because we couldn’t call the movie Route Molson! Canadian writers just don’t seem to “get” the military, its culture and foibles, characters, and many, many absurdities. I don’t see anyone in CanLit circles capable of producing anything even close to the quality or command of the subject matter you find in Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, for instance.

Though that’s a high bar, perhaps even a once in a generation kind of thing.

Even so, it’s a shame. Afghanistan was Canada’s longest war ever, and the literary community seems to be happy to pretend it didn’t really happen. Maybe because the general public seems happy to do the same.

I’m always curious to know what writers are reading, because to me the two things are inseparable. What have you discovered recently that you’d recommend?

I’m working my way through the great Expanse series by James S.A. Corey, which is the first classic scifi stuff I’ve read in ages. They have really re-invigorated a genre that everyone assumed was pretty much played out after authors like Heinlein or Larry Niven (Star Wars notwithstanding).

I just finished Erik Larsen’s The Splendid and the Vile, which is a fabulous look at the daily life of Churchill during the crucial first years of the Second World War. Who knew that he favoured brightly coloured floral patterned silk bathrobes after his daily bath?

It nearly inspired me to go out and buy one, to be honest. Nearly.

Thanks for that mental image. I’m also working my way through The Ministry of Truth: A Biography of George Orwell’s 1984 by Dorian Lynskey. I actually got to meet the author at an English bookstore in Paris – just around the corner from the garret where Orwell lived and upon which he based Down and Out in Paris and London – and had a great chat with him about what Orwell was like as a person, which is best summed up as: “a complicated son of a bitch.” It’s a book about a book, but manages to touch on a lot of things I find fascinating, particularly how the ideas in books weave their way into our collective consciousness and there’s no better example of this than 1984.

It was interesting watching my kids read that book in high school, and see their minds get blown by it. They didn’t know much about Orwell and thought that it must have been written sometime around 1984 (which is of course ancient history to them). That his work is so relevant today, eighty years after he wrote it, is both fascinating and frightening.

I’m going to find Lynskey’s book and read it myself!

I’ll loan it to you: as you know I’m a book socialist.

The post An Interview with Chris Wattie appeared first on Phil Halton | Literary Fiction Writer.

May 20, 2021

An Interview with Ben Fox

Ben Fox is a serial entrepreneur and avid reader whose latest venture is a new platform for book discovery, www.shepherd.com. I was curious to know more about what drove him to pursue this new venture, and he kindly agreed to be interviewed.

Phil: You have a number of businesses behind you already, mostly very tech focused. What attracted you to starting a new business focused on authors and books?

Ben: I love books and I love reading. I think books are half the reason for my tremendous optimism about humanity. I wanted to do something that helped readers bump into books they might not otherwise find. I love wandering through a bookstore and seeing what catches my eye. I want to build an experience like that, but the online version (nothing replaces a bookstore).

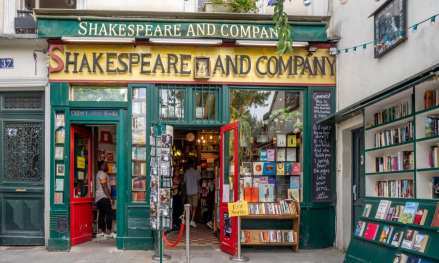

A bookstore is a great example of a commercial entity that can also form a sense of community. Some bookstores, like Shakespeare and Company in Paris, are legendary for supporting writers and readers.

Yep, and I would like to see if I can create a new version of that same community and support for writers and readers online. A big part of this is I want to help authors meet more readers. The pressure being put on authors to build and grow their own audience is insane. My hope is I can help them as the publishing world evolves.

And evolving is something that the publishing world has been doing a lot of in the past twenty years. Between the aggregation of publishers worldwide, and the same happening with vendors online, power is shifting within the industry. It’s becoming both more democratic (with a boom for self-publishing) and also less so (with fewer viable sales channels).

A lot of people might expect an entrepreneur to have a business degree or a similar education. How does your liberal arts degree impact your approach as an entrepreneur?

I think my liberal arts background is a symptom of my curiosity for the world and how things work. And being an entrepreneur is a natural extension of that. I love trying to figure out how things work and try to find new approaches to challenges.

That’s a great way to describe entrepreneurship. It’s that “try-fail-try again” mentality that seems to be a big predictor of success.

The pandemic has also changed a lot about how we shop for and consume books, accelerating existing trends towards digital. How does the Shepherd fit into this “new normal?”

Shepherd is focused on helping readers discover books. This is our entire focus, and we will be trying to find new ways to do this (what you see now is just the first step). I think book discovery is something Goodreads and Amazon do very poorly. And so, my goal is to replace them in this capacity.

I hope to eventually help local bookstores by freely licensing our book lists and book recommendations to use in their physical stores. I think local bookstores do discovery very well and this is how they are going to compete against Amazon and other changes in the publishing industry.

This is something that I love to hear, because as much as I love the convenience of “one click” shopping for a book that has caught my eye, I will always love bookstores.

Agreed, nothing will replace the magic of bookstores. My hope is to reimagine online book discovery and create a more serendipitous experience.

The world seems to be heading towards more AI driven processes that promise to “know us better than we know ourselves.” Certainly, Amazon’s algorithms already doing that for a huge percentage of book shoppers. Why the focus with Shepherd on hand curated lists?

We live in a time where social-media and shopping algorithms serve only to reinforce our world view. I want Shepherd to play a role in combating that. A book is one of the best ways to help someone see the world through different eyes. We need a lot more of this right now.

I couldn’t agree more. Books can open new vistas for people.

This is why I am doing hand curated lists by people who are passionate about a topic. I’ve found that the recommendations I receive from an individual with passion/expertise are a hundred times better than any machine. And, getting their reason why they love the book is more powerful than any marketing description. It also has the side effect of exposing their voice to the reader which drives even more interest in their book.

That is so true. We typically look to friends for these kinds of recommendations, but I gravitate to bookstores that I know are really well curated by their owners or staff. I know that they can help me find just the right book in whatever category they have expertise in, and so depending on what book I want to buy, I go to a different store. (I’m also lucky to live in a big city where this is possible). I love the idea of being able to access authors and their recommendations as well.

All of this makes me curious, though – are you a writer yourself?

Writer yes, author no. I’ve kept a very detailed personal blog since 2008 and that process of writing has helped me in so many ways. When I feel stuck, I love to sit down and write out a few pages of thoughts. It has been a very good habit to build. I do hope to one day write a children’s or YA book. I love to make up stories for my 4-year-old son Calico.

I identify much more as a storyteller than a writer, so that makes sense to me. Writing is just one way to convey those stories and telling them to my kids has been an outlet for me for years too.

Finally, a question I ask nearly everyone I meet, much less interview: what are you reading right now that you’d recommend?

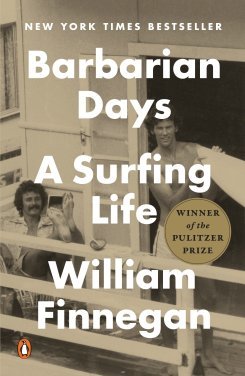

Yep, so far this year my favorites have been Fatherland by Robert Harris, The Girl and the Bombardier by Susan Tate Ankeny, the Empires of Bronze series by Gordon Doherty, and Achtung Baby by Sara Zaske. Last year my three favorite books were Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, Who Is Michael Ovitz, and the Dresden Files series.

Barbarian Days is a favourite of mine as well! I wonder what books William Finnegan would recommend!

The post An Interview with Ben Fox appeared first on Phil Halton | Literary Fiction Writer.

April 27, 2021

An Interview with Ele Pawelski

Ele Pawelski is a lawyer, former humanitarian worker and the author of The Finest Supermarket in Kabul, published in 2017 by Quattro Books. Many of the works written recently that are set in Afghanistan have been by soldiers who served there, and so I was interested in talking to someone whose experience in the country was as a humanitarian. Ele graciously agreed to be interviewed and to share her thoughts and experiences.

Phil: What first attracted you to becoming a humanitarian worker?

Ele: A flub in my law career. After my Articling year, as I hesitated about what next – that’s a whole different story – an opportunity to work with UN Women in Kenya came my way. I jumped at it. While there, my research supported the development of an Africa-wide women’s economic empowerment platform. It was momentous and energizing. The kind of work that makes you feel like you’ve just climbed a mountain to witness the best sunrise in the world.

I know what you mean. There are a few humanitarian projects that I supported in different places that I really felt good about, and that made any other work I did elsewhere pale in comparison. I think that a lot of humanitarian workers are sustained by that “high” when a project really moves the yardsticks forward in some way.

Something about being outside your home country elevates the thrill of accomplishment. Stakes seem higher or the projects more tangible. But to be fair, that adrenalin can be found everywhere.

Very true. Do you think that your background in humanitarian work impacts your writing?

Having lived and worked overseas has a bigger impact on my writing than the projects themselves. I see stories from other places or times that crave an audience.

That’s an interesting observation, because I think that when travel is done well, it gets us out of our comfort zones and really observing things with fresh eyes. In my opinion, observation skills are critical for writers. I see or hear or smell things all the time that get worked into my stories in different ways, sometimes in completely different contexts than where I’ve drawn them from. Where are some of the places you’ve travelled where you’ve seen these stories in need of an audience?

Let’s see: hiring a teacher in Bosnia to learn how to drive standard while my work colleague interpreted his instructions from the back seat; flying from Khartoum to my post in South Sudan and all the way back because my luggage had remained on the tarmac, literally; meeting a Kurdish activist in Syria who wanted his story told; getting stuck in Turkey for two days after I missed a connection to Tajikistan; learning where NYE parties happen in Antarctica; tracing where my father lived in post-WW2 Germany and talking to current inhabitants.

That’s enough fodder for a lifetime of writing! How about Afghanistan? What was your experience in Afghanistan like?

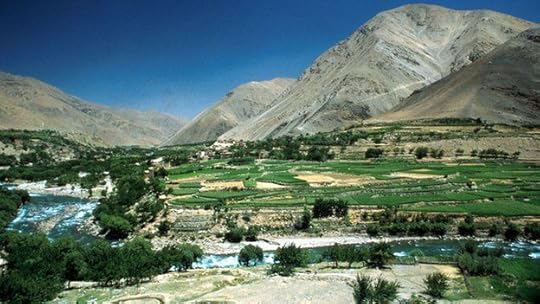

Kabul was a cozy neighbourhood for me. But mostly an ex-pat one. Like other places I’d lived, I met locals keen to be part of positive change. Yet the steps we took were so damn small. A few of my memories made it into my book – being on a plane from Delhi to Kabul that was packed with Pashtu men who were so out of place when the pop music blared after we landed; magnificent garden parties in the summer; breathtaking streams and mountains in Panjshir province; hours of tea drinking while shopping for rugs.

Panjshir Valley

Panjshir ValleyThe landscapes in Afghanistan can be amazing, particularly in the Panjshir valley. I drove down to Kabul from the north through the Salang tunnel, in winter, and I had to stay focused on the task at hand, otherwise I would have spent the whole time gawking out the window. Carpet shopping, with the endless rounds of tea and haggling, was something I really enjoyed too, and actually quite miss. I also recall some pretty crazy stores in Afghanistan, whose selection of goods was both limited and ever-changing. Expired-but-frozen Russian cheese, 20L buckets of pickles, bags of hot sauce – all might fill the shelves one day and be gone the next. Do you have any particular memories of shopping in Afghanistan?

An aisle dedicated to just Coke and Pepsi at The Finest Supermarket, where the main action of my book takes place.

That sounds familiar! The “bizarre bazaar” aspect of what was available was in the earlier days after 9/11, when there was so much disruption to trade, as well as all kinds of traders rushing to get goods they thought could sell into the market. Very chaotic times, really, especially for the Afghan people who had already weathered years of difficult times.

By the mid-2000s, bombings had become very common in Afghanistan, particularly in Kabul. What kind of impact do you think constant threat of violence, over long periods of time, has on a society?

Over time, a constant threat of violence begets acceptance and normalization of that violence and chaos, which is good for coping in the short term. Overseas, I worked in six different countries. With each new contract and country, my own tolerance for comfort and threat of violence stretched further and further. At the time, I didn’t notice. I don’t think anyone does. But over long periods, where people don’t have a choice to live differently, it stunts growth and slashes opportunity. Nothing good comes of long-term violence.

There have been some good studies written about this, but I don’t think that its widely enough understood that conflict creates a psychological impact on a society-wide scale. This becomes one of the root causes of further conflict as well, creating cycles that any society would struggle to pull itself out of.

Absolutely. We have our own issue of long-term, intergenerational harm of Indigenous Peoples. So much to sort out, to try to get right or better. Part of the reason I ended my international career is there are needs here that make more sense to me to work on.

There certainly is a lot of work to be done here in Canada, and Indigenous issues (which are actually Canadian issues) need to be at the top of our list.

Why did you decide to write “The Finest Supermarket in Kabul”?

In 2009, I made a rash decision to move home to Toronto – also another story.

I love that you have stories nested in stories nested in stories. To borrow from John Green (and Bertrand Russell), it’s as if its “stories all the way down.”

Friends suggested a memoir project while I sorted out a new career. Around the same time, I joined a writing group with the idea of expanding my circle of friends and finding a group of like-minded artists. As time passed, I absorbed more and more fiction written, and scribed some of my own.

Writing groups are an interesting thing. I joined one as well when I first started writing full-time, and I found some friends there who have endured. But I was pretty quickly tired out by the politics of the group, and after about two years, a few of us left to just do our own thing. A solid writing group is worth its weight in gold!

Honestly, my writing group was fabulous for a really long time – both for great writing and friendships that keep going even today. You and I connected through Heather Wood, from the writing group. I would never have published The Finest Supermarket without it. Recently, I joined another one. Hopefully it’ll get me through my next book. Plus, lots of wine.

I might have to get more details on this writing group of yours. It sounds great.

Truth be told, I couldn’t quite get the memoir going. Then, in January 2011, I read a very personal news story: a suicide bomber had targeted a convenience store in Kabul where I’d frequently shopped. I recognized the ads in the shop windows from online photos of the incident. Thankfully I didn’t know anyone who’d been hurt in the attack. But it felt like I did.

Just like that, I knew the tale I wanted to write. Seven years later, The Finest Supermarket in Kabul was published.

How much of “The Finest Supermarket in Kabul” is drawn from your own experience, beyond your reaction to that news article?

Tons! I’d say maybe forty percent. I had a driver like Asif; the male judge in Elyssa’s chapter is real, ug; the Friday midday gathering at Gandamack Lodge was a weekly event…

A great spot for a cozy gathering, and with a name drawn from the Flashman series as well! (it was the name of Flashman’s fictional estate) I’m a sucker for literary references.

I’m curious about your decision to use three point of view characters in your story, and to write in each case from the first-person point of view. Can you explain what led you to this approach?

When a bomb goes off in a place like Kabul, there’s a national impact, but at the core so many individuals are affected in different ways for a long time. I wanted to get into how that looked. I also wanted to show how different the same events can be depending on where you are and who you are: a politician who just happens to be there and jumps in to help, a journalist who deliberately goes there to cover the story, and a human rights lawyer who wants to be distant but is drawn closer as the afternoon unfolds. First person gives the reader connection and intimacy with each character.

It certainly does. I appreciate how your novella takes an event that seems very flat to most people – bombings are things that happen “somewhere else” to most Canadians, and they don’t give much thought to who might be impacted – and gives it depth.

What we get here are short, newsy snippets. The long read is missing. It’s more real, more human to find out what happens after the bomb.

Exactly. That same idea is what drove me to write This Shall Be a House of Peace, which is essentially the origin story of the Taliban, because otherwise all we know is the surface reality presented in the news.

This has been a hard year for a lot of people. Has the pandemic changed your view on the role of the artists/writers within society?

Creativity and artistry are such important yet often undervalued pursuits. The closure of so many events and activities has been hard. It’s cool to see subtle reinventions so creators and audiences can meet. I really hope we hang on to some of it.

Amen to that! And so, are there any new projects that you’re working on now?

I always have writing projects on the go! My current list includes research for my next book: when Grete and her daughter are evacuated from their small German town in WWII, she assumes her son will be safe at the children’s camp in the south. Instead, the leaders callously abandon the camp and the boys. Josef resolves to get home not knowing his mother isn’t there. They’re desperate to reunite, somehow. I also have a short story featuring a film camera in three distinct time periods, and another one set in Toronto’s art scene in the 1980s that I’m trying to get published.

All those projects sound interesting, but I love the idea of following a camera in different periods of time. I’m a history buff and a museum curator, and I am sometimes in awe when I think of the “journey” that different objects have taken to find their way into my hands.

I’m always curious about what other writers are reading. Is there anything that you’d recommend?

I try to read Canadian as much as possible: The Break by Katherena Vermette, The Sweetest One by Melanie Mah. Recently finished A Constellation of Vital Phenomena by Anthony Marra, and just picked up Petra’s Ghost by C.S. O’Cinneide after reading your interviews – I love the Camino!

Petra’s Ghost is amazing, and I’m glad that you heard about it from me!

The post An Interview with Ele Pawelski appeared first on Phil Halton | Literary Fiction Writer.

April 2, 2021

Review: The Caravan

There has been a lot written in the last twenty years about “global jihad,” although finding good analysis rather than rhetoric can be hard. Thomas Hegghammer does a great service with his latest book, The Caravan, which sheds light on a previously dim corner of the subject.

Part of the issue with the general Western understanding of political Islam and Islamic extremism is that there is a major disconnect between the material written (and being written) about it in Arabic and that available in English. Many works by men seen as “arch villains” in the West, such as Azzam and Sayyid Qutb, are widely read in Arabic as political philosophy, even by those whose views would not be seen as extreme. There is also a lot of material that is unavailable in English, limiting its influence on Western thinking, tough Hegghammer takes a major step in addressing that as well.

The Caravan is an expansive biography of Palestinian warrior-scholar-activist Abdullah Azzam. Known in the West primarily as a mentor to Osama bin Laden, his life and impact on Islamist thinking are much greater than that. Despite having been murdered in 1989, his works continue to influence extremists today, making understanding the man and his writing of continuing importance.

Hegghammer’s work is very detailed and extremely well cited, but at the same time, very readable. He weaves the heavy historical detail into a convincing story of a man whose life was dedicated to the idea of there being a duty to struggle against unbelief and injustice wherever in the world it might be. From growing up in the West Bank, to his involvement with the Muslim Brotherhood, and later as a leader and organizer of foreign volunteers in Afghanistan, Hegghammer details how Azzam’s thinking developed over the years.

Although scholars of the war in Afghanistan often refer to the presence of foreign fighters during the war against the Afghan Communist government and their Soviet backers, little has actually been written about the details of this aspect of the conflict. Steve Coll is one writer who has examined the issue, but as Azzam was one of the key organizers, Hegghammer’s work reveals how insignificant they really were in real terms.

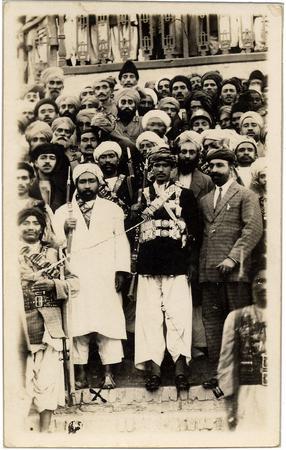

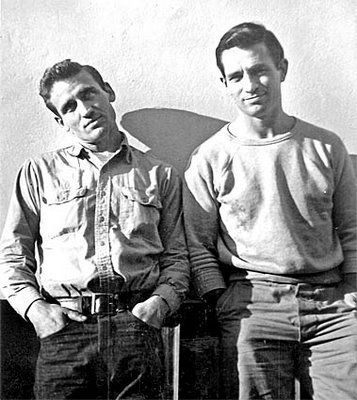

Abdullah Azzam (L) and Afghan mujahideen leader Ahmad Shah Massoud (R)

Abdullah Azzam (L) and Afghan mujahideen leader Ahmad Shah Massoud (R)Azzam is unusual in that he has been held up as an example of both moderate and extreme Islamism, seemingly fitted to the purpose needed by whoever is writing about him. Was he the extremist who laid the groundwork for Al Qaeda and who inspired the formation of the Islamic State? Or was he a moderate who tried to rein in Bin Laden and was eventually murdered for it? While Hegghammer does not have a neat answer to these questions, he shows the complexity of Azzam’s thinking, and how it evolved over time in response to events on the ground, giving the reader a better understanding of the true man.

Given that almost everything else written about Azzam is either hagiography or indictment, Hegghammer’s contribution is immensely important. Any serious student of Islamist extremism or the history of the Afghan conflict needs to read this book.

The post Review: The Caravan appeared first on Phil Halton | Literary Fiction Writer.

March 19, 2021

An Interview with Alastair Luft

Alastair Luft is an Ottawa based writer, whose two books—Jihadi Bride and The Battle Within—have both received a lot of praise. He’s also a veteran of the war in Afghanistan, and someone who took up writing in earnest later in life. Although I don’t know him personally, I know him through others, and wanted to find out more about his writing and what’s behind it.

Phil: I’m always curious when talking to other creatives about what got them started on that path. In your case, when and why did you start to write?

Alastair: In 2014, I took a parental leave of absence after the birth of my second daughter. My wife and I came up with a schedule that offered each of us a bit of down time from parenting, and—having left a busy job—what I found was that I didn’t have any creative outlets. I signed up for an introductory writing course online and enjoyed it so much that I decided to try National Novel Writing Month. By the end of November, I had a horrible first draft of The Battle Within, and also a newfound love of writing.

At what point did you decide that you wanted to publish what you’ve written?

I decided to keep working on what I had and when I’d taken the manuscript as far as I could, the only choice seemed to be either go for publishing or drop it. Since I didn’t feel quite done with the story—and also because I’d started to believe that writing was something I could see myself doing for many years—I went for publication.

In other parts of my life, I have a lot of agency, and so shifting gears to being a writer pitching agents and publishers that in many cases didn’t even reply was hard at first. I’ve found the sweet spot, I think, where I control the things I can and let go of the things I can’t. That’s not to say that I don’t slip sometimes, though. What was that experience like for you?

I found the business of writing – all things pitching, marketing, networking – overwhelming at first, and still do at times. Even by themselves, each of these activities could easily take hours of every day. At one point during the publication journey of my first novel, I realized I was spending most of my available time pitching marketing pieces or contacting people, and almost no time actually writing, which was totally backwards. Now, I set limits. Writing comes first, leaving me with whatever part of the day remains to get to the more business parts.

At times it seems like writing is the easiest part of the writing business when compared with pitching, editing, etc. That said, what’s the hardest part of writing for you?

I struggle most with letting the creative process take its course. I think my military background has maybe conditioned me to be timeline and output based, and so I’ll set goals for myself as to when I’d like to have a writing project done and then get caught up on meeting those timelines.

Oh man, I feel you on this. Being hyper-organized can sometimes feel like a superpower, and sometimes like a curse. I can show you excel spreadsheets with projected word counts by week…

While goals have their uses—and I should stress that I haven’t had to write a novel for a deadline—what I’ve found is that artificial deadlines can conflict with giving myself the time to get familiar with and have insights into the work-in-progress. Often I’m not ready to write a particular scene or story, and if I let my desire to ‘show progress’ drive my writing instead of telling the best story I can, that motivation can undermine the creative process itself. Many times, the best way for me to get out of being stuck on a project was to move to something completely different, which ended up giving me ideas on how to improve the project I set aside.

Writing to an outside deadline (something I’m doing right now) is definitely a whole different skill. I’ve found that when the writing work is the hardest, when I’m really working on something that has the potential to be great (even if just a sentence or two), my brain will find ways to try to wiggle out of doing the work. And the best way to distract me is to come up with a better, “shinier” idea. Some of my most creative ideas have popped into my head when I was up against a deadline or struggling with something else. I’ve become really careful to respect that part of the process too, and make sure that I capture those ideas, and maybe noodle on them for a while before getting back to what I’m “supposed to be doing.”

These are really great observations. It’s almost like the potential of greatness in a piece of writing can be the enemy of good, because somewhat ironically, you have to go through good to have a chance of the writing being anywhere close to great. I guess that’s the wisdom behind that old writer’s advice that, ‘you can’t edit a blank page.’ I’ve also had trouble respecting creative ideas when they appear, mostly because of an overinflated sense of my ability to remember them later. But each one of those ideas is an opportunity of some sort, and if you don’t give yourself time to explore them, they’ll almost certainly be missed opportunities.

We’ve both spent a good chunk of time in Afghanistan, and in some ways, I’d say that my experience there was the formative one of my adult life. What about your experience in Afghanistan works its way into your writing?

I spent almost three years there, so I’m sure a lot of that experience feeds my writing in ways I can’t even imagine. One thing that sticks out to me though is perhaps an appreciation of what Tim O’Brien meant when he wrote that, ‘a true war story is never moral.’ What was true in Afghanistan? Or better yet, what was one’s perception of what was true? The answers to those questions could be things you’d never tell another living soul. Like being with a person in their last moments. Or things that would never be believed, like a soldier walking away from the center of impact of a 500-pound bomb. If one is to be committed to the truth though—and I firmly believe that an artist’s warrant is absolutely to offer a version of the truth—then they have to get their hands dirty. They have to be as comfortable with obscenity as they are with beauty, because that’s the truth, and if they’re not prepared to do that, they risk making art that is really propaganda.

I think you’ve hit on something really important here, which is an artist’s obligation to truth. That doesn’t mean telling everything exactly as it occurred, it means servicing the underlying truth of a story, which sometimes is better achieved through fiction. This is what Tennessee Williams meant by the writers providing the “truth in the pleasant guise of illusion.”

I think that this is part of why I am drawn to setting my writing in conflict zones, despite the fact that war itself isn’t what I am writing about. War strips away a lot of the illusions, of individuals and of society, and lets you get to the truth faster.

I’d agree with that and I might add that as settings, war and conflict zones are also unique because of their proximity to death, which brings a corresponding proximity to life. Because of that, human emotions and actions in these places can be deeper and richer, in both good and bad ways. I mean, take the example of surviving an attack that might have killed a friend or a comrade-in-arms; it will be completely normal to feel both joy at still being alive, and guilt that your friend died, and this can provide wonderful fodder for storytelling because both of those feelings can be intensely true.

So all that said, what spurred you specifically to write “Jihadi Bride”?

I followed the rise of ISIS throughout 2014 to 2016, which was when I was writing my first novel. At the time, there were a number of stories about Canadian citizens being radicalized, like Martin Couture-Rouleau, who killed WO Patrice Vincent in St-Jean-sur-Richelieu with a car, or Michael Zehaf-Bibeau, who killed Cpl Nathan Cirillo and attacked Parliament Hill. One story that stood out for me, though, was about John Maguire, a 23-year-old from Ontario.

He was killed fighting with ISIS in Syria, no? His nom de guerre was Abu Anwar al-Canadi, I think.

That’s right. This was a man who grew up playing hockey in small-town Canada, and his radicalization caused me to wonder what circumstances would cause someone to follow this path. Closer to home, I wondered if it would be possible for my own children to radicalize, and if so, what would need to happen for them to think joining a group like ISIS was a good idea. Plus, what would I do if that happened? Exploring those ideas provided the primary building blocks for what became Jihadi Bride.

That’s really interesting. In a sense, the novel is a thought experiment about “what if this happened to someone I love.” That’s a much more nuanced and sympathetic view than what one might expect.

I can’t speak for anyone else, but one thing I took away from Afghanistan is that there are generally good reasons for why people do what they do, even if we might fundamentally disagree with their actions. That is, after all, one of the core tenets of counterinsurgency theory, which is that insurgent movements are often grounded in legitimate grievances, like being disenfranchised or alienated. And, if no attempt is made to understand – and I mean really understand – the fundamental motivations of those who might be in opposition to us, I think it really undermines any ability to identify realistic, long-term solutions. That said, I’m also not saying that violence should be ruled out as a potentially appropriate response, only that we should use violence with our eyes wide open about its chances of success, as well as its costs.

As a part-time writer, how do you balance your day job and the other demands in your life with your writing practice?

Finding opportunities to write while also working a full-time job and being present with my family is tough, that’s for sure. For me, I had to reconsider my priorities so I could make decisions about what I was prepared to sacrifice so I could write. As an example, although I was on track to be promoted when I began writing in earnest, I ended up opting out of career progression so I could protect time for my family and for writing. Ultimately, my continued development as a writer is more important to me than whether I make it to the next rank, which would come with increased responsibility and commitments. Compromises are important as well, and my wife and I have a constant dialogue about supporting my writing, which these days is mostly done in the early morning hours. It’s frustrating to make slow progress because of limited time, however, I try to adopt the attitude that every decision I make is support the intent of creating more opportunities for me to write in the future.

That’s a really important idea — building a writing practice/career over time, rather than seeing it as an all-or-nothing endeavour. And I think it cuts both ways, as I make choices to do things other than writing that supports me writing long term, just as I choose not to do things to focus on writing. I think that there are a lot of people who never start a creative career because they can’t bring themselves to quit their jobs, but that’s not really the right approach most of the time. (Full disclosure: I quit my job to become a writer, and it turned out fine)

The danger, I think, in an incremental approach is that at some point you still need to make the leap. I have a lot of respect for you in going all in because it’s very tempting to wait for the ‘perfect circumstances,’ but because of that, it’s also very easy to become comfortable with one’s circumstances. For me, I’m fairly confident I’ll be able to set the conditions to be a full-time writer, but my concern is making sure that I’ll have the courage to go for it when the time comes.

Has the pandemic changed your view on the role of the artists/writers within society?

Even before the pandemic, I felt that the role of artists—to include writers—was to hold up a mirror so society could see itself. If anything, the pandemic has only strengthened that viewpoint. I agree that a story should entertain, and it’s perfectly fine for some art to be purely about entertainment. That said, I also feel that really powerful art—the kind that sticks with you long after it has been experienced—involves more than entertainment. Tolstoy claimed that if thought is communicated through speech, then emotion is communicated through art, and I feel that this continues to be the role of artists and writers; to help people understand the world around them and the human condition through emotion. I think the best compliment I could receive about my novels is that they generated a feeling in a reader.

Yes, that connects back to the idea of having an obligation to truth. Truth, when revealed, can’t help but provoke emotion.

Both of us write in multiple genres or mediums. What are the challenges that you’ve found come with this?

By far, I think the greatest challenge is being able to adapt. Even within the same genre, a particular story might demand a different style than what a writer might be used to, and so the challenge becomes whether the writer will adjust their writing to serve the story, or whether they’ll force the story to change to fit their writing. This becomes even more complicated when writing in different genres because conventions and obligatory scenes of those genres all change to greater or lesser degrees. Even more challenge is added when switching between fiction and non-fiction, and even within non-fiction genres such as narrative or academic. The thing is though, I feel like crossing genres improves overall writing skill through interdisciplinarity; it adds tools to the toolbox that a writer can deploy to create artistic effect regardless of the story, even if that use might be in what others would consider non-standard ways.

I think you’ve already started to jump into the next question I had for you with that answer, but what advice would you give to other writers or artists?

What I would offer is that people should be clear with themselves about why they’re pursuing an artistic endeavor, writing or otherwise. This absolutely doesn’t have to be a multi-paragraph vision statement; it’s enough to know that you do it because it makes you happy. I say that because as much as I love writing, it’s not always fun and games. There are days I feel like I have no business being published at all, or that I will never be able to tell a story that way I see it in my head. I often feel like I’m wasting my time. Steven Pressfield would probably call these doubts, ‘manifestations of Resistance,’ and I think that one way to make it through these rough periods is to very much understand what reason compels us to do what we do.

I like a lot of what Steven Pressfield has to say about writing, and his concept of “resistance” really resonates for me, as well as his idea of an artist serving or accessing their muse. It doesn’t hurt that he used to be a Marine, either. He doesn’t shy away from the hard stuff.

I also got a lot out of Pressfield’s repurposing of parts of the Bhagavad-Gita, like having a right to our labour, but not the fruits of our labour. Whenever I get too caught up in process and output as opposed to content, I try to bring myself back to this idea so I can be as true to my art as I can.

Another reason to appreciate our motivation in pursuing art relates to how seriously to pursue professional development. If all you want to do is dabble—and that’s totally fine—then maybe paying for courses or professional feedback isn’t money well spent. For those who want to improve, however, these types of expenditures might be critical.

There is definitely a fine balance to be found. Thinking of writing as a business, it makes sense to invest in yourself. BUT…there are a lot of snake oil salesmen (and women) out there who know exactly how to prey on writer’s insecurities and desires. It seems that there are traps at every step of the writing game, in fact, and you really need to think about the value of what you are paying for.

We both took a certificate program in Creative Writing, and you’re pursuing a Masters in it. What’s the value that you get from those programs?

Both the certificate program I took through Humber College and the Masters were studio programs which consisted mostly of direct mentorship. As an older student, I think I was much more receptive to absorbing advice from established writers based on their experiences as opposed to maybe a more academic based program. Plus, the writers I was lucky enough to work with – Ashley Little at Humber, and Martin Randall at University of Gloucestershire – were outstanding critics who were able to dial in on possible shortcomings in my writing in an objective, professional manner that built me up and gave me confidence. The other benefit of the Masters program was the opportunity to look at specific artistic movements such as minimalism, which helped me understand a few of the available overarching strategies that can help influence what techniques and styles a writer might want to use for a particular story.

Can you talk about any new projects that you are working on?

I have several projects in development, the first of which is a literary thriller about a retired Navy SEAL who leads an assassination mission against the president of China. This novel was an opportunity to get out of my writing comfort zone, and provided me with the chance to experiment with nonlinear narratives and minimalism, which I felt was important because of a tendency for me to overwrite. One Kingdom Under Heaven comes out on June 17, 2021, and I’m currently searching for advance readers.

That’s coming up soon! How can prospective advanced readers get in touch with you?

If advanced readers are willing to leave a review of One Kingdom Under Heaven, they can sign up to receive an e-book at this link. Another option is to sign up for my mailing list at this link.

The second project I’m working on is an illustrated creative nonfiction book about civic engagement written for new / young adults. This one has turned into somewhat of a labor of love, and I find myself continually torn between giving up on it or pushing on. Although set aside for now, my plan is to run the manuscript through concept and line edits later this year and, if everything goes well, to begin development on the illustrated side of the project after that.

Lastly, I’m also on a very early draft of a novel about siblings at odds with each other when they inherit the family farm after their parents pass on. I would love for this story to be the setting to examine larger societal trends taking place in Canada right now, although progress to date has been very slow. I’ll get there though!

I take the same approach as you, I think. I always have several projects on the go at once, though I try to focus on one at a time. Writing is one thing, but publishing is such a slow-burn process that I feel like this is the only approach that makes sense.

And finally, what are you reading now or have read recently that you’d recommend?

In line with my work-in-progress, much of what I’m reading these days is about various perspectives on Canada and Canadian history. Seven Fallen Feathers, by Tanya Talaga, deserves every award it has won. I also greatly enjoyed The Best Laid Plans, by Terry Fallis, No Great Mischief, by Alistair MacLeod, and The Englishman’s Boy, by Guy Vanderhaeghe. Lastly, for something slightly different, I also enjoyed Stephen Graham Jones’ Mapping the Interior, which is part ghost-story, part coming of age.

I know some of those books, but I’m going to check out the ones that I don’t!

The post An Interview with Alastair Luft appeared first on Phil Halton | Literary Fiction Writer.

March 9, 2021

Habibullah Kalakani – The Bandit King