Murdo Morrison's Blog, page 2

February 14, 2012

Immigration- A Personal Story

We hear a great deal these days about immigration and ‘The American Dream.’ It seems appropriate now, after the events of the past few years, to place quotes around the latter term. My perspectives on both issues are influenced by personal experience.

I came to the United States in 1973 as an immigrant. Few possessions arrived with me beyond a holdall with some clothing. My only important asset was a wonderful wife. Passage to the country was achieved with the aid of a low cost ticket sold by Pan American intended, as I recall, as an economical means for students and young adults to travel to the US. The ticket was for a round trip. I purchased it knowing that I would not be using the other half.

My wife, an American I met while she was working in Britain, had saved a modest sum of money while in college. We used it to acquire a serviceable vehicle. With only half a college degree resulting from my studies in the UK I embarked on a rather typical immigrant path, working at what jobs I could find while attending school at night. One of those early jobs was with Friendly Ice Cream Corporation as a trainee manager. A typical day shift began early. My morning routine before opening included washing the windows, cleaning the floor, emptying (and scrubbing) the trash bins and cleaning both bathrooms. After restocking any needed items I made sure that the parking lot was free of trash. With that series of tasks complete I began my day cooking hamburgers, scooping ice cream cones, serving customers or washing dishes, whatever was necessary. Daytime shifts were usually twelve hours in length. Afternoon/evening shifts continued until the work was complete, sometimes at one or two in the morning.

In 1974, we accepted a position as houseparents in a group home. This allowed me to attend college full time and complete an undergraduate degree. At this point we had a young daughter. Like most (or all) social work jobs, the pay was poor. One advantage (and disadvantage) was that we had accommodation in the house. While providing a place to live it left us exposed to the inevitable stresses of the situation.

In 1975 we decided to move on and relocated in the town where my college was located, removing the need for a daily commute. I found work in a pharmacy delivering prescriptions in the evenings. Eventually I became the night manager of the small section of the store that sold cigarettes and liquor. Following graduation in 1976 I found work with a payroll processing company, first as a data clerk then as a delivery driver.

In 1978 I was accepted to graduate school in Massachussetts. Before school started I spent the summer as a parts picker in an industrial supply outlet. The first couple of years of school were taken up with course work and the selection of a thesis topic. While completing the research and writing I worked at a number of jobs. Apart from an unsatisfying stint selling insurance, the rest of these were in retail. For a time I was a trainee and later manager of two Radio Shack stores. The first was a a small store in a remote, ostensibly dying plaza. For a week that typically exceeded 70 hours my reward (after taxes) was around $134. This was in the early to mid 1980s. I had already sought and been offered another job when the unexpected happened. I was ‘promoted’ to another store.

This was not straightforward. Each time a manager moved the process included a closing inventory and an opening inventory. In those times inventories were counted by hand and were lengthy and demanding. There was no way that I could reveal my imminent departure and risk several weeks of no income so I said nothing. I think you might imagine the nature of the telephone conversation with the District Manager a few weeks later when I informed him.

Other retail jobs followed selling insurance, a job taken because it was available and got me out of the thankless situation at Radio Shack. For a time I was manager of candy, stationery and health and beauty aids at a department store. Immediately following that I managed two shoe stores, both owned by the same family, again for long hours and little reward. My most extreme job move came next, from shoe store to college lecturer.

In all of these moves I had kept my college education hidden as much as possible, knowing that it would likely keep me from employment.

In the interim my wife had also worked at a series of jobs, including stints at Friendly’s and as a cashier in a grocery store. I will be eternally grateful to her for the invaluable contribution she made, which allowed me to complete my education. She also attended college at night, acquiring a qualification in Medical Records to add to her undergraduate degree.

Two decades of hard work began to pay off. A move to New Jersey took us away from the worsening economic situation in Massachussetts. We were able to obtain professional work that finally allowed a standard of living that was a great improvement over what we had experienced before. In the meantime two additional children had been added to the family. We were able to send all three to college though each had to work hard to supplement what we were able to provide.

I have shared this story to make a point. As an immigrant who worked hard to become established I do not condone breaking the law by entering the country illegally. However, we need to find a way to solve this issue in an equitable manner. Immigrants represent a huge potential resource. They also represent some of our most grateful, loyal and patriotic citizens. The immigration issue has, in my opinion, been used by politicians to distract the average person from the real reasons why unemployment is so high.

It pains me also to hear people who are running for office talk about class warfare while demonstrating a disturbing cluelessness (and lack of concern) of the plight of those at the lower end of the economic spectrum. There is much talk of the ‘middle class’ and virtually none about the poor or those falling out of the ‘middle class’ at alarming rates. Any attempt to question the role of the rich in the state of the common weal is described as class warfare. This is a willful distraction. If anything, the class warfare is being directed at large numbers of the population by candidates whose goal seems to be to favor those at the upper end of the economic spectrum. It is politicians who seek to divide and distract us from the real issues and to turn one group against another.

Having been a grateful beneficiary of the opportunities offered by this country I worry greatly that our democracy is being coopted by those who mask greed with talk of values. The founding principles and ideals of our country mean a great deal to me. Though not born here it has become home as surely as if I were a native son. In my heart I am.

January 23, 2012

The Difference That Sixty Years Can Make

I am writing a book the timeline of which extends from the late 1940s to the present. This process involves quite a bit of research. Inevitably, the process makes me think of how much life has changed in 60 years. This is particularly true of the state of medicine. We take a lot now for granted that simply did not exist, or was not expected, in a previous time.

In the book a character has a heart attack in the year 1960. The setting, Glasgow, Scotland. I needed to discover what the treatment would have been in that year. The answer came quickly and was a revelation. The only tools in the medical arsenal then was administration of a pain killer such as morphia and bed rest.

Philippa Roxby, a health reporter for BBC News tells the story in an online article dated July 9, 2011. According to the article if heart attack victims “died in their 50s and 60s it was considered a fact of life.” The article also reports that,

“In 1961, there were 322,917 deaths from cardiovascular disease, accounting for nearly half of all deaths in the UK. Heart attacks and angina chest pain were common, but little understood.”

My grandfather, like the character in my book, died of a heart attack in 1960. He was stricken at work and walked home. His family called the doctor and he was admitted to hospital. Today, such an event would result in an immediate call to the emergency number. Subsequent events would have proceeded with some urgency. My grandfather survived the initial heart attack but not the subsequent one that took his life. He was 65.

In 1955, at age five, I had my own brush with death. My event began in school. I experienced extreme abdominal pain. My mother was summoned and she took me home and put me in bed. My father came home from work. It was now early evening. Our family doctor was called. This would have involved going to a public telephone box since no working class family like ours had access to a personal telephone. This was an era when your doctor would visit your home. Before he arrived my abdominal pain abruptly stopped. My acute appendicitis had now become peritonitis, a potentially life threatening condition.

It is interesting to note the mindset of the time period. In the current world, I think the majority of people would consider severe abdominal pain in a five year old child to be a medical emergency. An adult experiencing a heart attack would not walk home. I don’t know whether this reflected family attitudes or a more general approach to illness and medical services. My sense is that people in this time period had fewer expectations. I have the impression that people were more likely to wait to be told what to do, to place considerable weight on the word of key members of the community such as the doctor. Perhaps also, since medicine offered far fewer options in those days, people tended to be more fatalistic.

Interestingly, our doctor, reportedly, gave my parents a hard time about their delay in seeking attention. He immediately instructed my father to call for an ambulance. In those days, ambulances functioned mainly as transportation. No treatment was available en route. On arrival at the hospital I was wheeled immediately into the operating theater.

It is clear to me that, if I had experienced peritonitis 15 or 20 years prior to when I did, my survival would have been unlikely. Antibiotics such as penicillin were only them becoming available. My survival and recovery took quite a bit of post-operative care. Antibiotics doubtless played a significant role.

I wonder if, perhaps, our expectations of what medicine can do have swung rather too far the other way. Certainly, enormous progress has been made. However, for many conditions, satisfactory treatments have yet to be found. I suspect that finding a cure for many of them will remain elusive. The progress that has been made has raised the hopes and expectations of many patients to levels that may not be justified in every case.

Fifty years ago, heart attacks were poorly understood and there was no good treatment available for those who experienced them. Fifty years from now, will we have found treatments for medical conditions such as some forms of cancer for which no good solutions exist today? Let’s hope so.

January 13, 2012

The Recipes of Roses of Winter

An American reader who liked Roses of Winter commented that I might, perhaps, have included too many scenes in which tea drinking is an important activity. It may appear so but I doubt that anyone who grew up in the culture would see much exaggeration. A regular accompaniment to the tea was homemade scones.

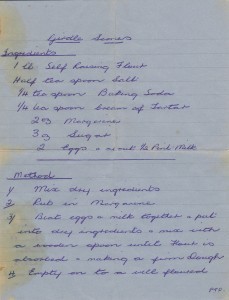

Page one of Aunt Betty's handwritten recipe

While usually the province of women in that time, one of the male characters, Jimmie Gow, takes up baking. He produces wonderful baked goods but is reluctant for it to be widely known. His wife Pearl is required to take the credit.

As a teenager in the 1960s, I also learned how to bake, although it didn’t bother me who knew it. On many occasions that baking took place in the kitchen of my Aunt Betty. Forty years (and more) later I still bake. These days, it’s mostly bread but I can produce acceptable scones and other items. I know they are acceptable based on the rapidity of their disappearance.

I would like to share with you an authentic recipe for girdle scones. Girdle scones are baked on a stove top griddle or girdle. A flat cast iron cooking surface or griddle works well for this. This is my Aunt Betty’s original recipe, published here for the first time.

Page 2 of the scone recipe

Girdle Scones

Ingredients:

1 lb (pound) self-raising flour

1/2-teaspoon salt

1/4-teaspoon baking soda

1/4-teaspoon cream of tartar

2 ozs (ounces) margarine (or butter)

3 oz sugar

2 eggs

approx. 1/2-pint of milk.

Method:

1. Mix the dry ingredients.

2. Rub in the margarine.

3. Beat eggs and milk together, put into the dry ingredients and mix with a wooden spoon until flour is absorbed and makes a firm dough.

4. Empty on to a well-floured baking board enough at a time to make a round. Roll out the dough to a thickness of 1/4-inch and cut into 4 quarters.

Bake on a moderately hot girdle or hot plate. Finding the right temperature in your particular set up will take some practice. When the scones are brown on one side turn them over and brown the other side.

Important: Handle the dough as little as possible

New Year (or Hogmanay) is an important holiday in Scotland. There are two scenes in Roses of Winter set on New Year’s Eve. A common item on the table at such family gatherings (and on other special occasions) is dumpling.

I have made quite a few dumplings in my time, though not as many in recent years. The images below are of one I made a few years ago. Each individual or family has their own favorite recipe. First, a brief explanation about what a dumpling is. A dumpling is made from a mix of flour and a range of ingredients that can include dried fruit or even fresh apple. Some like to use beef suet. The defining ingredients are the mix of spices, which give dumpling its distinctive rich flavor and aroma. The dough is not baked but placed in a heavy, plain cloth that will hold up to boiling. Here is my mother’s recipe for dumpling.

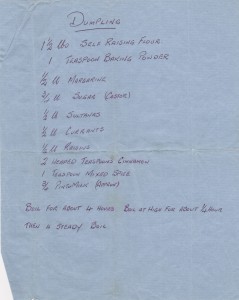

Dumpling

Ingredients:

1-1/2 lbs self-raising flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

My mother's handwritten recipe for dumpling

1/2 lb margarine (or butter)

3/4 lb sugar (castor)

1/2 lb sultanas (golden raisins)

1/2 lb currants

1/2 lb raisins

2 heaped teaspoons cinnamon

1 teaspoon mixed spice

approx. 3/4 pint of milk

fl

flDumpling dough in the cloth ready to go in the pot for boiling

Method:

Mix the ingredients and place the resulting dough in a floured plain cloth (such as a sturdy unbleached muslin). Flouring the cloth is an important detail that should not be omitted. Tie the bag with string leaving enough space for some expansion of the dough. Place in a large pot. It is recommended that you place a plate that can stand up to the process inverted in the bottom on which the bag will rest. Boil for 4 hours (high for about 15 minutes then at a steady boil).

My mother left out a few details in her recipe probably because she knew that I was well aware of how to complete the process without help. Here is what to do once the dumpling has been boiled. Untie the string and carefully peel back the cloth just enough to expose what will become the base of the dumpling. Place a large plate on top of the exposed surface of the dumpling. Carefully (and you might need help) turn the dumpling over 180 degrees. Now carefully complete the removal of the cloth. The goal is to preserve the surface of the dumpling. The dumpling should then be placed in a warm oven to dry it off, not to bake it further. The dumpling that results will have a brownish hue (see illustration).

Flouring the cloth creates a distinctive rind on the dumpling that is one of its unique characteristics. When I was a child it was not unusual for people to place ‘favors’ in cakes or in a dumpling. One tradition was to wrap an old silver threepence bit in wax paper and place it in the mix. Modern sensibilities about the risk of choking have long since ended this practice.

A finished dumpling sliced to reveal the interior

Note for non-British readers:

Mixed spice is a mix of various spices sold in Britain under the name ‘mixed spice’. Recipes for making this mix can be found on the internet. I have found that American apple pie spice works well as a substitute.

Conversion from British to American kitchen measures can also be found on the internet. Just a reminder that a British pint is 20 fluid ounces, not 16.

If you like this blog you can subscribe and receive updates when new posts appear.

January 8, 2012

Volunteering – How it Changes Lives

We hear a great deal about parents who push their children into activities designed to increase their competitiveness in the effort to enter the best universities and colleges. While I see nothing wrong in studying hard and striving to be better, my sense is that sometimes parents lose sight of what it takes to create a well-rounded individual.

I question the notion that one can draft a foolproof plan for success in life, however one defines that goal. My experience has been that some of the best things in my life have resulted from not taking what some might consider to be the safe and sensible path.

In 1971 at age 21, I dropped out of university and signed on as a volunteer with an organization called Community Service Volunteers. The experience literally changed my life, a story I tell in my book A Hole Without Sides. Read Chapter 1.

Community Service Volunteers (CSV), a British organization that connects volunteers of all ages with a variety of opportunities to serve, is celebrating its 50th year. When I was a volunteer, the organization was not yet 10 years old. It has greatly expanded the range of its activities in the interim.

In 1971, CSV acted as a clearing house that connected volunteers with organizations. I spent time at two quite different facilities. The first was a halfway house for ex-prisoners in a small village in Rutland, now part of Leicestershire. The second was a closed unit for adolescents in Bristol.

Volunteers received the cost of travel from CSV, the organizations provided room and board. I believe there was also a small allowance from CSV. The minimalist structure of those early days encouraged volunteers to be self-reliant. You had to learn to deal with the situations that came up. As a volunteer, I received a comprehensive course in the university of life, not only from the residents in the locations where I volunteered, but also from the variety of staff and other volunteers I met. In a short space of time I gained a lot of experience in many aspects of human behavior. Until then I had led a somewhat narrow, restricted life. Volunteering opened a window and let in some much needed air.

Volunteers gain at least as much as the organizations and people they try to help. It can be very hard to measure any potential impact you might have as a result of your service. The changes in you as an individual are often easier to gauge, although it may take you some time to realize their full extent.

For those readers who are also parents, realize that I am not advocating that you have to go to the extreme of dropping out of school to be of service. That was just the way it played out for me. What I am suggesting is that including service in the education of a young person is a very valuable experience. So much of life these days seems to have taken on the form of a competition, a game, where the value of activities and goals assumed to be important is not necessarily examined or questioned. While community service is often included in the activities encouraged in high school, I believe that intent makes a difference. Doing something for its own sake matters.

I would make an argument for encouraging an interval of service between high school and college. I spent several years teaching at a university and found that many students were ill-prepared for the experience. Many had never been given the opportunity to experience independence of thought or action, or had the ability to make decisions for themselves. Six months or a year of volunteering, time spent in the university of life, might make a lot of difference in the personal growth of young people. Our fractured society needs more people with empathy for others. Volunteering is one way to encourage that.

And volunteering is not just for the young. Our society often undervalues the experience of older people. This is a huge mistake. Just as CSV’s range has greatly expanded, opportunities can be found for a diverse group of people, young and old, to be of service. In giving you also receive riches.

If you would like to support the valuable work of Community Service Volunteers learn how here. Many other fine organizations could also use your help. Seek out the ones in your area and support them.

If you like this blog you can subscribe and receive updates when new posts appear.

January 5, 2012

My Grandfather at Dunkirk

My novel Roses of Winter, set in World War 2 Glasgow and various theaters of the war, includes several chapters that describe the evacuation of British troops at Dunkirk. Although fiction and intended to be an engaging story, Roses of Winter is based on extensive research. I would like to share some of that background information in this blog post.

Charles Burnett in the 1950s

My grandfather Charles Burnett was born in Fraserburgh, Scotland in 1895. When writing the chapters about Dunkirk, I drew upon the few known details of his service in that time period of the war. Since he died in 1960, when I was just ten years old, I never had the opportunity to ask him about his experiences. One enduring family anecdote relates that he was stranded with the troops at Dunkirk after his ship, delivering gasoline for the British Expeditionary Force, was disabled in Dunkirk harbor. The family remembers little else except that he was eventually taken off on a ship called the Royal Daffodil. My mother, Ella Morrison, remembers him appearing on their doorstep in Maryhill, Glasgow after being missing with no word for several weeks.

I found the family story intriguing and built two chapters of my historical novel, The Roses of Winter, around the few known facts. Researching ship arrivals and departures at Dunkirk, I found a ship that fit the known circumstances. The Spinel, a small coastal vessel of about 750 tons, arrived in Dunkirk on May 24, 1940 and was reported lost on May 25. The ship carried what was known as ‘cased petroleum,’ essentially gasoline in cans for use by motor transport. This was a potentially dangerous cargo – the cans were not well constructed and could leak as they rubbed together in the ship’s hold. At least one known explosion resulted in another ship.

Spinel as she appeared in the post-war years (image source unknown)

Further research indicated that the Spinel was salvaged by the Germans and returned to service as a British merchant vessel after the war. It survived until 1971 when it was scrapped at Renfrew on the Clyde. Inquiries on the Internet resulted in my corresponding with a crew member who sailed on the ship long after the war.

The Spinel was owned by the William Robertson Company, often known as the Gem Line because its ships were named after precious stones. In Roses of Winter, the Spinel is the model for the Jasper. Mentioning the name Spinel appeared to trigger long-forgotten family memories. My Aunt, Betty Campbell, on hearing the name, believed that the Spinel was the ship her father served on.

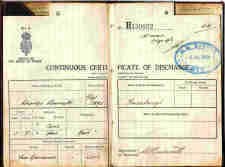

The later rediscovery of my grandfather’s wartime service documents has redefined his actual history, appearing to confirm part of it while leaving the remainder a mystery.

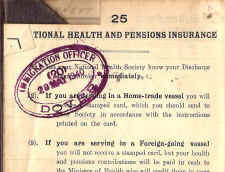

Immigration stamp

To the left is shown an immigration stamp dated May 29, 1940. This provides intriguing evidence that the family memory of his return from Dunkirk is accurate. However, no corresponding entry for a ship during that time has been found.

The stamp is in one of two book-like documents known as a Continuous Certificate of Discharge. This was a record of a seaman’s service listed by ship, including date of signing on and off. There may have been yet another book that was lost, perhaps during the evacuation.

So little is known about my grandfather’s real experiences that the Dunkirk chapters in Roses of Winter are almost entirely fictional. The events going on the background of the fictional action are, however, real and match the actual timeline of events at Dunkirk. This involved a great deal of research. Even the weather conditions reflect the actual history. Every ship mentioned except the Jasper was a real ship.

My grandfather's Continuous Certificate of Discharge

When I knew my grandfather he was working for a laundry in Anniesland, Glasgow looking after their boilers. He would take me to see them sometimes, usually when the laundry was closed. I remember the deserted laundry and the boiler room. He would occasionally start up a small steam engine or pump to let me see it working.

My grandfather was a very unique sort of man who enjoyed life. He had an almost childlike appreciation of fun and his many unconventional deeds were and are legendary in the family. I was involved with him in many of them and have some very special memories. He died when I was ten years old. I wish he had survived into my adult years. There is so much now that I would like to find out.

If you like this blog you can subscribe and receive updates when new posts appear.

January 2, 2012

Zamalek, a rescue ship in World War 2

My novel Roses of Winter, set in World War 2 Glasgow and various theaters of the war, includes several chapters that describe the adventures of a convoy rescue ship, the Izmir. The Izmir was based on a real ship, the Zamalek. Rescue ships and the invaluable service of the merchant navy in the war have not received the attention they deserve. One goal of Roses of Winter was to address that omission. Although fiction and intended to be an engaging story, Roses of Winter is based on extensive research. I would like to share some of that background information in this blog post.

The convoy rescue ships were born of the bitter experience gained in the early months of the war. The convoy escorts, few in number compared with the need and strained to the limit, had little time or opportunity to stop for survivors as they tried to locate and destroy attacking U-boats. When they did pick up survivors they were ill-equipped to treat the often horribly injured and exhausted men. The answer was the conversion of a number of vessels for use as rescue ships.

Rescue boat

The Zamalek (known previously as Halcyon) was built by the Ailsa Shipbuilding Co. in 1921 in Troon, Scotland. In the years before World War 2 she served in the eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea, carrying cargo, mail and passengers.

Zamalek under way in heavy seas

Requisitioned in March, 1940, Zamalek underwent conversion for service as a rescue ship at Barclay Curle shipyard in Govan, Glasgow and was allocated to the rescue service in October, 1940. At 1566 tons, with a low freeboard and single screw, the Zamalek was typical of many small merchant ships that underwent conversion. As part of the Fleet Auxiliary she flew under the blue ensign. I have a personal connection with this ship in that my father, Donald Morrison served as Third Engineer on the Zamalek from 1942 until 1944.

In the course of the war, Zamalek served on Atlantic convoys, Arctic convoys, and off the West coast of Africa. She is probably best known for her service on Arctic convoys, most notably on convoy PQ 17. Only 11 of the ships in Convoy PQ 17 made it to port. Three rescue ships (Zamalek, Rathlin, and Zaafaran) accompanied the convoy. Zamalek and Rathlin survived, Zaafaran was lost.

An injured man is brought on board

Zamalek, like other rescue ships, had medical facilities on board, including an operating theater and sick bay. Well armed for her size, a rescue ship such as the Zamalek did not have the status of a hospital ship and would have played an important role in the defense of convoys in addition to picking up survivors.

Burial at sea

Included in this post are images from the wartime operation of the rescue ship Zamalek. Such photographs are rare. My thanks to George Graydon, an officer on the Zamalek, who took these photographs and gave permission for their use.

Finally, a word about the Captain of the Zamalek, Captain Owen Charles Morris. Born in Pwllheli Wales in 1905, Captain Morris served as Master of the Zamalek for over four wartime years while the ship picked up the most survivors of any Allied rescue ship in World War II. For his service, Captain Morris was awarded a very deserved Distinguished Service Order (DSO). George Graydon, who served under Captain Morris, told me that he was very highly regarded by the ship’s crew.

If you like this blog you can subscribe and receive updates when new posts appear.

December 28, 2011

My life in a Glasgow tenement in the 1950s

In my novel Roses of Winter, set in World War 2, the characters live in tenement apartments in Scotstoun and Maryhill, neighborhoods of Glasgow, Scotland. The description of the Scotstoun location is based on my memories of living in a Scotstoun tenement in the 1950s, an experience very similar to that of the 1940s. That lifestyle was very different from the one I currently enjoy in New Jersey, USA. In this blog post I share what that experience was like.

I spent the first seven years of my life in a tenement in Scotstoun, Glasgow at 2005 Dumbarton Road. It was in the middle of a long row of similar structures, built in the last decades of the nineteenth century. At the rear was a column of toilets, added to try to bring the building into the twentieth century. Several families shared each toilet, which was apportioned one to a landing. One of my earliest memories is of my father putting on his coat in the middle of the night and taking me out of the house and down the stairs to the WC.

The flat was of the kind commonly called a room and kitchen in Glasgow. The kitchen was connected to a small bedroom by a narrow passage we called a lobby. Cooking was done on a range built around a central fireplace, which also provided the heat for the oven. This was the sole source of heat in the apartment. The range had to be periodically cleaned with ‘black lead’ and emery cloth, an exhausting process. My sister and I slept in a box bed, an alcove curtained off from the kitchen. It was warm even in winter. We treated it as our own province, a walled off ‘castle,’ where we piled up pillows and sheets, and made ‘tents’ with the blankets.

We lived on the top floor and another early memory is sitting up on the sink, boxed in with rough, plain wood, from which emerged a swan neck water pipe and tap, to look at the tramcars clanking past on the street below. Most were double-decked, either the older models, many of which had been remodeled from versions built around the time of the Great War, or the newer ‘Coronation’ types. Sometimes we would see the rarer single-decked ‘Yoker’ car go whistling past.

It was a simple life with few material embellishments. We had an old tube (we called them valves) radio for our primary source of entertainment and news. But it was also a time when books and simple conversation whiled away an evening. ‘General knowledge’ was a very popular concept with our teachers who would ask us many, detailed questions about our world.

The amount of knowledge we were expected to have at our fingertips, to be considered a member of the educated population, was phenomenal. For example, we were expected to know where cocoa was grown, or the capital of Australia, just as we were expected to be able to recite our multiplication tables. It would be anathema to many modern educators and yet, if it was so bad, why does my generation seem so better informed? We were preoccupied with ‘knowing’ things. It was possible to buy ‘quiz books’ inexpensively and we would sit around the fire with our parents testing our knowledge in each category. The older generation, though many had had to leave school early to augment their family income, valued education and wanted their children to have better opportunities.

Our playground was the house. There were no gardens, or lawns. From the street you entered our tenement along a dark ‘close,’ which went all the way through to the backcourt. The main stairs led from the close to each of the landings. The ‘backyard was a bleak area of mostly bare earth interspersed with blighted grass and grubby dandelions. Here were the ‘middens’ where housewives threw their trash and the ash from coal fires into large open cans. I can remember the lingering smell of rotting food and ashes even now. Immediately behind the middens was a railway embankment, along which clanked small goods trains with long lines of coal wagons leaving behind their lingering, sooty aroma.

Despite the air of poverty, the working class ladies who lived in the close took great pride in their domain. The close and stairs were washed carefully and made bright with pipe clay. Women generally stayed home. My father worked at Yarrow’s shipyard and could walk the short distance to his job in a few minutes. Its closeness meant that he could come home for ‘dinner’ at midday. The shipyard hooter regulated our day. In the mornings, men in dungarees hurried to punch their time cards so they wouldn’t get docked for being late. At night, they spilled out, tired, grubby and eager to get home and wash for their ‘tea.’ The measure of a good man in that society was that he went home and not to the local pub. Too many found comfort from their hard existence in a ‘beer and a hauf.’

The shipyards were a constant presence to us. The river lay just on the other side of the railroad and the air was often redolent with its greasy, decayed, diesel oil aroma. The cranes towered over everything, a commanding presence that paid tribute to the importance of shipbuilding to the city. Once small villages like Clydebank and Scotstoun became the focus of that great era which produced the Queens and many other important ships. Both areas had taken a terrible pounding from the Luftwaffe, as they tried to wipe out the shipyards. Yarrow’s had taken a direct hit, destroying a shelter packed with workers. Born in 1950, the war became for me a part of the folklore of living in Glasgow. It was a recent memory to my parents, and there were many reminders in the empty lots and derelict air raid shelters. Rummaging through our grandparent’s closets we would still find gas masks and ration cards.

One of our favorite things as children was to have Dad take us down to Yoker ferry to see the ‘boats.’ My father never called them that – to him they were ships. He had spent the war years in the Merchant Marine, mostly on convoys, first to America, then to Murmansk and Archangel. He was a modest man who didn’t like to talk about himself. Many years later I would read the true story about his ship the Zamalek, one of three rescue ships on the infamous convoy PQ 17, and tell him how proud I was of him and what he did.

Sometimes we would make the short return trip on the ferry at Renfrew. It was a drive on car ferry, open at both ends with a passenger walk up on top. It was driven by enormous chains, anchored on each bank that traveled into the engine compartment, and was used to haul the vessel across the river. Sometimes a cargo ship captain coming up river would get nervous and give short blasts on the steam whistle, warning the ferry out of the way. Then the decks of the ferry would rumble and the ferry would pick up to its top speed, which was still very slow. It was marvelous and inexpensive entertainment.

“The Clyde made Glasgow and Glasgow made the Clyde,” my father would say. On Sundays we would take the tram to Kelvingrove to visit the Art Galleries. Dad would always gravitate to the ship exhibits where he proudly pointed out the turbines of the old King George V. As a teenager he had worked through his apprenticeship to become a ‘blader,’ a skilled job. Then we would wander through the ship model gallery and look at the smaller versions of the ships that had made Glasgow famous. We all knew their stories, the Hood, built just a short distance away, and sunk by one unlucky shell from the Bismarck, the ‘Queens,’ and countless others. As a young man, my father had worked on the Queen Mary at John Brown’s shipyard in Clydebank. We knew the flags and colors of the big shipping lines. The river was in our blood, it was our blood.

© Murdo Morrison 2011

If you like this blog you can subscribe and receive updates when new posts appear.