Christian Monö's Blog, page 2

January 17, 2025

Our Leader-Centric Mindset Is Eroding Democracy

© Envato

© EnvatoIn a speech last week, Magdalena Andersson, the former Swedish Prime Minister and head of the Social Democrat party, made a peculiar statement. She observed that “an increasing number of countries are moving in an authoritarian direction.” Yet, in these troubling times, she argued, the world “requires stronger leadership.”

What Andersson meant by “strong leadership” wasn’t entirely clear, but it’s a phrase used increasingly often in politics – especially in countries with authoritarian decision-makers.

The Democratic ErosionAndersson is right—we are seeing a shift towards more authoritarian behaviours in politics. In their wonderful book, The Origins of Elected Strongmen, Erica Frantz, Andrea Kendall-Taylor, and Joe Wright describe a nearly three-decade decline in democracy. They link this development to a global rise of personalist political parties, “a trend consistent with the growing personalization of politics observers have documented in democratic systems.”

I’ve noticed similar trends in my own work. While many factors contribute to this personalization of politics, there’s one root cause we often overlook—our leader-centric mindset.

© EnvatoHow Leadership Has Changed Our Thinking

© EnvatoHow Leadership Has Changed Our ThinkingIn my book Why We Follow, I explore how leadership became a global phenomenon around the mid-1970s. Since then, the concept has come to influence our thinking, shaping both our worldview and our behaviour.

This shift has given rise to a range of paradoxes, some of which I’ve mentioned before. For example, while people still believe in democracy—“rule of the people”— they also insist that people need leaders to guide them.

We're not born with these contradictory thoughts. Rather, I believe they stem from decades of being conditioned to see leaders as the solution to all our problems. This mindset has shaped us far more than we often recognize.

Consider the evolution of election posters in Sweden. Early 20th-century posters focused on ideologies and collective visions. By the 1990s, that had changed, and most posters featured the head of the party. For instance, during the 1998 elections, the Swedish Centre Party ran a poster featuring its head, Lennart Daléus, with the simple caption: “This is Lennart.”

Our Belief in Leadership Makes Us PassiveImagine you’re on a boat that’s taking on water through a crack in the hull. You grab a bucket and start bailing water, urging your friend to find the captain. As the water rises, the captain appears and assures you, “Don’t worry, the pumps will take care of it.”

Twenty minutes later, you’re treading water as the boat disappears beneath the surface.

This is the danger of a leader-centric mindset. When experts tell us that leaders will solve our problems, we’re more likely to adopt a passive stance. Whether it’s a minor issue at work or a major crisis like climate change, we’ve been conditioned to wait for a “leader” to take charge.

This passivity creates fertile ground for authoritarian figures. By identifying—or even manufacturing—problems that no one has addressed, they can position themselves as the “strong leader” we’ve been waiting for. The rest of us lean back, hoping they’ll deliver. But as The Origins of Elected Strongmen illustrates, once such individuals gain power, they often dismantle democratic systems. And once democracy is dismantled, it’s incredibly difficult to restore.

A Call to Action

A Call to ActionWe need to rethink our fixation on leadership. Democracy isn’t about waiting for a saviour; it’s about collective action and shared responsibility.

If we want to protect democracy, we must shift our mindset. Instead of asking who will lead us, we should ask: what can we do together?

The future of democracy doesn’t depend on finding the perfect leader. It depends on rediscovering the power of the people—the power of natural followership.

New books on this topic

The Origins of Elected Strongmen by Erica Frantz, Andrea Kendall-Taylor, and Joe Wright. Although academic, this book is highly accessible and incredibly engaging.

To Stop a Tyrant by Ira Chaleff. While I haven’t read this book yet, having enjoyed Chaleff's previous works and seen the positive reviews, I’m confident this will be a compelling read.

And of course:

Why We Follow - Coming January 31, 2025.

January 2, 2025

Mastering the Art of Unlearning

Learning is an essential part of life. From the moment we’re born, we observe, explore, and absorb knowledge. We try, practice, and develop skills—some more deeply than others.

As we grow, learning becomes methodical. In many countries, children spend over a decade in structured education, where they’re even taught how to learn—how to find, analyze, and articulate information.

The beauty of learning is that the knowledge and skills we acquire are truly ours. People can take away your possessions, your job, or even your relationships, but no one can take your knowledge and abilities.

The Things That StickI’ll never forget the pride in my grandfather’s eyes.

“I still remember it,” he said, his voice steady as he raised his arms with confidence. He was 97 years old, his mind slowly succumbing to dementia, yet at that moment, he was 17 again—reliving his days in the Swedish Navy.

He had lied about his age to enlist and was trained in flag semaphore, a method of communication using flags held in various positions to spell out messages. Nearly 80 years later, he could still recall the semaphore alphabet.

Once you learn something thoroughly, it’s hard to unlearn it. For instance, unlearning how to speak your native language is practically impossible. Most of the time, this permanence works to our advantage. Imagine having to relearn your language every time you wanted to have a conversation!

The Learning CurseBut there are times when unlearning is not only useful—it’s necessary.

Sometimes, the things we’ve learned are outdated, inefficient, or just plain wrong. In such cases, unlearning becomes essential.

Take leadership and followership, for example. Many people struggle to adopt a natural followership mindset because they keep reverting to old habits. They continue viewing managers as leaders and followers as subordinates—a perspective that perpetuates hierarchical thinking. (Here’s why that’s a problem.) Despite their best efforts, they unconsciously fall back into viewing the world from a leader-centric perspective.

How to UnlearnSo, how do we unlearn something? After years of reshaping my own thinking on leadership and followership, here’s what I’ve learned:

1. Willingness to Change

It’s easier to want change than to make changes. Many of us want to lose weight but resist exercising more or eating differently. The same applies to unlearning. To succeed, you must embrace change, which often means altering ingrained behaviours and mindsets.

2. Replace the Old with the New

Unlearning isn’t about forgetting—it’s about replacing. To unlearn a behaviour, replace it with a new one. To unlearn outdated knowledge, replace it with updated insights. Replacement is the foundation of unlearning.

3. Be Consistent

Consistency is the toughest part of unlearning. Once we’ve learned something well, it becomes second nature—we act or think without even realizing it. Unlearning requires us to become conscious of these automatic habits and deliberately override them.

Progress may be slow, but small, gradual changes over time yield the best results. If you’re looking for a guide, I highly recommend the book Atomic Habits by James Clear.

Unlearning is challenging, but it can also be incredibly rewarding. By replacing outdated habits and mindsets, we open ourselves to growth and innovation.

If this topic resonates with you, check out this article: Learning to Unlearn.

For more information on natural followership, check out Why We Follow: Natural Followership in a World Obsessed with Leadership

December 16, 2024

Natural Followership vs. Followership

Image from Envato

Image from EnvatoThe questions we ask ourselves determine the answers we get. This may seem obvious, but we rarely pay attention to it. When I first started exploring followership, I had one objective in mind: to understand what makes people want to follow someone else.

I initially phrased the question like this: What makes me want to follow someone else? I figured that if I could explain my own reasons for following somebody, it would be a first step toward understanding why others do the same.

In hindsight, I realize that if I had phrased my question just a little differently, the outcome of my work might have been completely different.

Consider these two questions:

What makes me want to follow a leader?

What makes me want to follow someone else?

To answer the first question—why we want to follow a leader—we need to know what a leader is. This tends to narrow our field of view because most of us already have a preconceived notion of leadership.

The second question is different. It doesn’t assume we’re following a leader. It simply acknowledges that there are moments when we follow other people. That distinction proved critical in uncovering the concept of natural followership.

Followership with a Leader Perspective?When I started exploring natural followership in the early 2000s, the idea got about as much respect as a talking-cat video on Facebook. People were curious, but they weren’t taking it seriously.

Today, the interest in followership is on the rise. Next year, the fourth global followership conference will be held in Los Angeles. There will be people from all over the world, which is amazing. I hope to see you there, by the way!

In short, the leadership community can no longer ignore followership. But here’s the catch: When leadership experts turn their attention to followership, they tend to do so with a leader-centric mindset. They generally ask: What makes people follow a leader? or How should people follow leaders? They then interpret what they see from a traditional leadership perspective. After all, they already have a preconceived definition of a leader

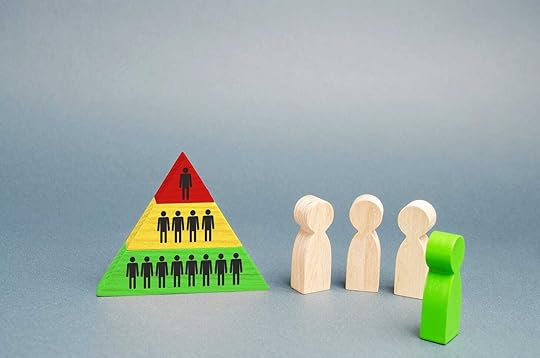

Image from EnvatoNatural Followership vs. Traditional Followership

Image from EnvatoNatural Followership vs. Traditional FollowershipWhen exploring natural followership, we don’t assume that followers are subordinates. Nor do we assume that followers obey orders. Instead, we look at how people naturally collaborate and follow each other in non-hierarchical environments.

For most of human history, our ancestors appear to have lived in small, egalitarian groups. Studying these societies gives us a window into how people lead and follow when there’s no hierarchy involved.

Another example is how a group of friends makes decisions. Although there are no bosses or CEOs, friends still manage to solve a wide variety of problems or challenges together. They do this by building what I’ve come to call collaborationship through the process of natural followership.

I explain this in more detail in my coming book, Why We Follow: Natural Followership in a World Obsessed with Leadership. But in a nutshell, natural followership explains how we humans naturally follow one another to achieve shared goals. Compare this to traditional followership, which tends to focus on how people act (or are expected to act) when they’re in subordinate roles.

Why Does This Matter?While I’m thrilled to see followership gaining traction worldwide, I’m also worried.

If we’re not careful, the followership could end up as just another branch of the leadership tree. If we keep assuming followers are subordinates, that managers are supposed to be leaders, and that learning followership is just a way to improve management skills, then we’re missing the point.

To make followership truly valuable, we need to go beyond the boundaries of traditional leadership thinking. We need to ask bold questions like:

What if the way we organize businesses and societies actually stifles real followership?

What if everything we thought we knew about leadership and followership is wrong?

What if there’s a better way to collaborate than having a so-called “formal leader”?

The answers to these and similar questions could change everything. I’m just not sure the leadership and followership community is ready to take that leap.

Please check out the 2025 Global Followership Conference at https://www.followershipconference.com

December 1, 2024

Patriotism as a Tool

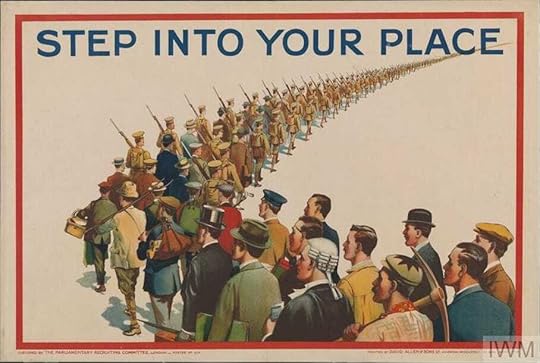

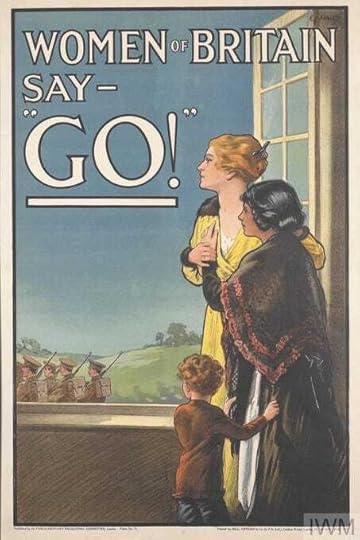

British WW1 poster © IWM (Art.IWM PST 0318)

British WW1 poster © IWM (Art.IWM PST 0318)Americans are renowned for their patriotism. According to a 2023 Pew Research Center study, 20% of Americans believe that the U.S. “stands above all other countries in the world.” Meanwhile, only 27% think “there are other countries that are better than the U.S.”

Imagine meeting someone who genuinely believes they are the world’s greatest human being. How would you react? We all know there’s no such thing as the “world’s greatest human.” Greatness requires context. For example, we can’t call a hammer the world’s greatest tool because its utility depends on the situation. Try eating soup with a hammer, and you’ll see my point.

The same principle applies to people and countries. To measure greatness, we need context.

“The Greatest Democracy in the History of the World”

During the 2024 U.S. elections, Vice President Kamala Harris declared, “We are the heirs to the greatest democracy in the history of the world.” Her statement might seem clear as she’s referring to democracy, but what does "greatest" really mean?

If Harris meant “largest democracy,” then India surpasses the U.S. by population. If she meant “best democracy,” how do we define “best”? Democracy means “rule of the people,” but at least 20 nations granted women the right to vote before the U.S. did. Is a democracy still the "greatest" if half the population couldn’t vote for much of its history?

According to the Democracy Index by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), the U.S. downgraded from a “full democracy” to a “flawed democracy” in 2017. Despite this, more than 70% of Americans still believe their country is one of the greatest in the world.

“It’s Sweet and Fitting to Die for One’s Country”

Merriam-Webster defines a patriot as someone “who loves and supports their country.” How patriotism is expressed varies from person to person, but history shows it’s a powerful tool for uniting and mobilizing populations.

Consider World War I. In Britain, posters proclaimed, “Britons. Join Your Country's Army!” or “Women of Britain Say 'Go!'” In the U.S., similar messages read, “I Want YOU for U.S. Army” or “The Navy Needs You—Don’t Read American History—Make It!” Such calls to action relied on a willingness to sacrifice. As Roman poet Horace famously wrote in 23 BC: “It’s sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.”

Biritsh WW1 poster © IWM (Art.IWM PST 2763)

Biritsh WW1 poster © IWM (Art.IWM PST 2763)China’s Patriotic Education Law

On January 1, 2024, China implemented a “Patriotic Education Law.” Consider Article 2 of the law:

“The state is to carry out patriotic education among all the people, cultivating and enhancing the attachment of the Chinese people to the great motherland, passing on the spirit of the people, enhancing the perception of the state, solidifying and uniting all patriotic forces, making patriotism a resolute belief, spiritual force, and conscious action for all the people.”*

Why would a country feel the need for such a law? What does it aim to achieve?

Patriotism as a Tool

Humans possess an innate desire to belong. This need is so powerful that many are willing to compromise their values to maintain membership in a group. Wartime observations have shown how ordinary individuals can commit unimaginable atrocities, such as killing innocent civilians, simply to preserve a sense of belonging.

Patriotism taps directly into this need for belonging. The more patriotic we feel, the greater our willingness to make sacrifices for our country. Political decision-makers can exploit this. By employing patriotic rhetoric, they try to strengthen group identity and influence what thoughts and behaviors are accepted by the public.

Now, patriotism isn’t all bad. It unites people and encourages us to strive toward a common goal. The danger arises when patriotism is misused, particularly by those in power, to serve personal agendas.

Another problem is when patriotism becomes so excessive that it blinds people to their country’s flaws. This can stifle a country’s growth—why strive for improvement if perfection has already been achieved? It can also lead to a collective rewriting of history, making the state seem better than it really is, thereby reinforcing the belief that it’s exceptional.

Final Thoughts

Patriotism is a double-edged sword. It can inspire and unite, but it can also be manipulated to suppress dissent and justify harmful actions. The key is to recognize patriotism for what it is—a tool. Like any tool, it should be used wisely, with accountability and reflection, lest it become a weapon turned against us.

*Translated by China Law Translate (CLT)

Have you read:November 17, 2024

Attack Behaviors, Not Opinions

Over the years, I've encountered managers and leadership experts who’ve been frustrated—and even angry—about my views on natural followership. This has made me think about how we handle opposing opinions.

Do We Have the Right to Our Opinions?

Of course, we do. But what about the right to express them? Throughout history, societies have tried to control what people think and say, often with devastating effects. In 1934, shortly after the Nazis took power in Germany, it became illegal to criticize the government. News was censored, anti-Nazi newspapers were shut down, and so-called “un-German” books were banned and burned. We see similar behavior today in places like Russia and Afghanistan, where speaking out against the regime can result in punishment or even death.

But What About in Democracies?

One of the most fundamental rights in a democracy is the right to express one’s views. Yet, in every country—democratic or not—certain opinions are considered unacceptable. Whether the reason is social, cultural, religious, or moral, expressing certain opinions can lead to aggressive repercussions from others.

Take J.K. Rowling. In 2020, she faced intense backlash after making comments about gender identity that many labeled transphobic. Despite claiming to support trans rights, her opinion sparked widespread criticism from fans and LGBTQ+ advocates.

Politicians face similar challenges. When Republican Congressman Tom Rice voted to impeach Donald Trump after the Capitol riot, his own party turned on him. He received death threats and angry emails, eventually requiring police protection.

Why Do We Find Opposing Opinions So Threatening?

Why do we react so strongly to opposing opinions? There are a few reasons. First, opposing opinions can feel like an attack on our core values or our identity. Sometimes, they just hurt our feelings. Other times, we interpret them as a sign of disloyalty. In some cases, opposing views simply frighten us because we don’t know what might happen if the opinion takes hold in society. Put simply, it’s probably not the opinion itself that bothers us, but how it makes us feel or what it might lead to.

What Happens When We Suppress Opinions?

We all have opinions—whether we express them or not—so forcing people to repress their views doesn’t solve anything. In fact, the more we try to dictate which opinions are valid and which are not, the more likely we are to create conflict. You and I don’t want to be told what to think or believe, so why would anyone else?

When people feel silenced, they’re more likely to seek out like-minded groups. This means we might not know how many people share a certain opinion until the group becomes strong enough to push back. This may be one reason why populist movements can rise seemingly out of nowhere—because we’ve silenced or discredited certain opinions.

Attack Actions, Not Opinions

We need to draw a line between opinions and actions. While we may disagree with someone’s views, it’s their actions that matter. We can express harmful opinions, but we don’t have the right to act on them. For example, we can say that all green-eyed people should be imprisoned, but acting on that opinion crosses a line.

Society has the right to push back when actions cause harm, but expressing an opinion—no matter how troubling—shouldn’t lead to aggression. Instead, it should be met with reasoning

The Power of Tolerance

Tolerance isn’t about agreeing with every opinion. It’s about accepting that people will have different beliefs—and that’s okay. As the Cambridge Dictionary puts it, tolerance is “the willingness to accept behavior and beliefs that are different from your own, even if you don’t agree with them.” Most of us want others to tolerate our opinions, but we often struggle to extend that same tolerance to those who disagree with us.

Maybe the first step in building a more tolerant world is recognizing the difference between someone’s opinion and their actions. If you ask me, not all opinions are equal, some are better than others, but all of them deserve the respect to be voiced. Only then can we engage in meaningful dialogue without the impulse to shut others down.

Worth Considering

Do we have the right to express our opinions, no matter what they are?

Are there opinions that should be kept to ourselves? If so, why?

October 27, 2024

The Lost Art of Listening in Meetings

Many years ago, before my hair turned grey, I was asked to make a short presentation for my company's executive team. Young and eager to impress, I spent hours preparing, imagining every possible question and rehearsing potential answers.

On the big day, I arrived ten minutes early. As I waited outside the meeting room, I did a few breathing exercises to calm my nerves. Twenty minutes later, I was still waiting. The executive team was behind schedule, and I ended up waiting a full thirty minutes before it was finally my turn.

When I finally entered, I found myself facing ten or so highly senior managers, including my boss and the CEO. Nearly all of them were preoccupied with their computers, and yet the CEO told me to begin.

Am I boring you?

The presentation was a disaster. Except for my boss and the HR manager, the participants spent most of my presentation working on their computers or fidgeting with their phones. I even caught one manager scrolling through her Facebook feed.

I was deflated. Why had I been invited to speak if the executive members weren't going to listen? They didn’t even give me a chance. My respect for the team plummeted and it never improved.

That day, I learned a valuable lesson: no matter who you are, if you want to be respected, give others your attention. Especially if you've invited them to your meeting.

“No matter who you are, if you want to be respected, give others your attention.”

The Importance of Listening

Over the years, I've attended countless meetings where managers reply to emails or read unrelated reports while someone else is speaking. I must admit, I’ve done the same when I feel I’ve got nothing to contribute or when I am overwhelmed with work. I’m not proud of this—quite the opposite—and so I’ve reflected on what causes me to lose my focus.

Why Do We Stop Listening?

Whenever I feel the urge to check emails in a meeting, it usually means one of two things:

1. I’m trying to be productive. Usually, this means I haven’t planned my day properly, and I’m now scrambling to catch up.

2. I feel that the meeting or discussion isn’t relevant to me and that there are other tasks I consider more important.

To avoid this situation, I try scheduling time for administrative tasks like emails and reports. I also practice the art of saying "no" to meetings. If I'm unsure whether I should attend, I'll ask for clarification or decline.

Be Respectful

I believe that no matter how senior we are, we owe the participants of our meeting our full attention. Ignoring someone to check our phone or laptop isn’t just rude—it signals that we’re either bored or uninterested. Consider it this way—are you impressed by someone who doesn’t have the time to give you their attention in a meeting?

I don’t think anyone likes so to be ignored, and so unless you want to appear arrogant or out of touch, put the device down and engage in the meeting.

Worth pondering:

What’s the most frustrating behavior you’ve encountered in a meeting? Why was it frustrating, and how did you handle it? Are there any meeting behaviors that put you off, and why?

October 13, 2024

The Fear of Being Visionary

“The risks of being visionary may explain why most companies choose to play it safe. “

The dream of being visionary. Image by Wirestock-Envato.

The dream of being visionary. Image by Wirestock-Envato.Not long ago, I read Henry Ford’s autobiography. In it, he stated, “The moment one gets into the ‘expert’ state of mind, a great number of things become impossible.”

Ford believed that once someone considers themselves an expert, they cease to evolve. As he put it, “No one ever considers himself an expert if he really knows his job. A man who knows a job…is always pressing forward and never gives up an instant of thought to how good and efficient he is. Thinking always ahead, thinking always of trying to do more, brings a state of mind in which nothing is impossible.”

Ford was a true visionary. Merriam-Webster defines the term as someone with “unusual foresight and imagination.” Ford didn’t just dream about the future; he actively set out to build it, surrounding himself with people who were “crazy” enough to share his vision.

Dreamers focus on the destination;

visionaries concentrate on how to get there.

Many organizations want—or even need—to stand out to survive in today’s competitive world. Yet, when it comes down to it, few display the courage to genuinely embrace what it means to be visionary.

Some confuse being a visionary with being a dreamer. As Martin Luther King Jr. put it, “The difference between a dreamer and a visionary is that a dreamer has his eyes closed, and a visionary has his eyes open.” Dreamers imagine possibilities but often fail to take action. In contrast, visionaries not only envision the future—they also possess the determination to realize it.

In other words, dreamers focus on the destination; visionaries concentrate on how to get there. In business, there are far more dreamers than visionaries.

The Dream of Being VisionaryBeing a visionary means taking risks and finding your own way, which can be challenging, time-consuming, and uncertain. Many businesses struggle with this issue. Rather than forging their own paths, they often imitate their competitors, measuring their success against others.

To embark on a visionary journey, companies must have a strong belief in their potential, the determination to overcome challenges, and the courage to move forward, even when the outcome is uncertain. Unfortunately, many companies prioritize quick wins, shy away from risks, and aim for incremental growth—none of which truly embodies visionary leadership.

Henry Ford was a true visionary. Image by Duallogic-Envato. Following the Herd

Henry Ford was a true visionary. Image by Duallogic-Envato. Following the HerdThe risks associated with being visionary may explain why most companies choose to play it safe. They adopt a traditional approach:

Benchmarking against competitors, tracking industry trends, and ensuring they don’t fall behind.

Improving products and services to enhance their market attractiveness.

Developing new, yet not radically different, products or services to maintain a competitive edge.

These strategies reflect a business mindset, not a visionary one. A business mindset focuses on short-term goals and validation from peers, while a visionary mindset seeks to break free from established norms.

There's a quote often attributed to Henry Ford (: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” Although Ford likely never said this, it serves as a great example of his visionary mindset. Companies with a business mindset seek faster horses, while visionary companies are less concerned with the actions of others. They keep their eyes fixed on the future they intend to create.

A business mindset focuses on short-term goals and validation from peers, while a visionary mindset seeks to break free from established norms.

Why Visionary Thinking MattersThe reason I chose this topic is that I believe now, more than ever, we need visionary individuals and companies.

Visionary thinking is essential for tackling many of the serious challenges the world faces today, such as the climate crisis. It’s also important from a business standpoint. While playing it safe may keep a company afloat in the short term, only those willing to embrace a visionary approach will truly stand out in the long run. True innovation emerges from venturing into the unknown, not from following others.

As Henry Ford demonstrated, being visionary isn’t about expertise or mastering what is already known—it’s about constantly looking forward, embracing uncertainty, and believing in the impossible. For businesses that wish to stand out, this is the only path worth pursuing. By having the courage to question the status quo and invest in ideas that others deem too risky, they lead us into the future.

Interested in Followership?

Save the dates for the 4th Global Followership Conference—May 28-30, 2025

Hosted by Claremont McKenna College, Claremont, California

September 30, 2024

Why We Need to Stop Equating Managers with Leaders

Many people, including leadership experts, use the terms leaders and managers interchangeably. They seem to do this even if they argue that leaders and managers are different things. I believe this has led to much confusion within the fields of leadership and followership.

The Confusion Between Leaders and ManagersEvery day, I hear people refer to managers as leaders. This is puzzling because many of them also argue that leadership has nothing to do with exerting authority over others. Despite this, their actions suggest they assume business leaders are managers. Let me give you a few examples:

Leadership training generally targets managers: Most programs designed to improve leadership skills are aimed at those in managerial roles.

Limited focus on employee leadership: When training does include employees, it’s often labeled as “self-leadership,” which suggests that these programs are about leading oneself rather than leading others.

Education efforts focus on managers: When organizations want to enhance leadership, they typically invest in training for managers instead of all employees.

Managers identify as leaders: Many managers see themselves as leaders, while employees rarely view themselves as leaders of their managers.

Followers are seen as subordinates: In most discussions about leadership or followership, followers are equated with subordinates, reinforcing the idea that leaders must hold a position of authority.

In other words, while many argue that decision-makers are not necessarily leaders, most assume that all leaders are decision-makers.

Explore Your Own ThoughtsConsider the following statements and see if you agree or not:

Leaders are people of authority.

Leaders have some form of decision-making rights over their followers (be it minor or absolute).

The role of a leader is semi-permanent, meaning they hold their position long-term.

Subordinates are followers because they report to someone else.

Leaders choose their followers (for example, through recruitment).

Leaders set the vision and/or goals for their followers.

Leaders are responsible for the success of their group.

The Natural ApproachIf you answered "no" to all the above questions, you’re less likely to assume leaders are managers. From a natural followership perspective, this is positive news. For one, as I’ve discussed before, we choose the leaders we naturally follow. We follow different leaders depending on what we want to achieve. Thus, the role of a leader is temporary and should be seen as a tool used by followers to achieve their objectives—not a position held by an authority figure.

Once this is clear to everyone in an organization, they can embrace aspects of natural followership by tapping into the innate human tendencies that have driven collective success throughout our species' history. This approach not only aligns with our social nature but also positions companies to adapt more effectively to the complex and rapidly changing business landscape of the 21st century.

Until next time – stay curious!

September 15, 2024

Are You Unknowingly Sabotaging Workplace Collaboration?

There’s a quote I like by Henry Ford: “Coming together is a beginning; keeping together is progress; working together is success.” So far, I haven’t met a single person who argues that cooperation between employees is a waste of time. In fact, most will argue that collaboration is key when building a successful team. Therefore, one would assume that improving collaboration would be a top priority for most employers. But that’s not the case.

Take a moment to reflect on your own workplace. How many intentional efforts to foster collaboration have you seen over the past year? What did those initiatives look like, who initiated them, and what were the results?

Identifying Non-collaborative Behaviors

Now, let’s take it one step further. Have you ever considered how many processes, routines, behaviors, or habits exist in your workplace that hinder collaboration? For instance, are you working in a culture that unintentionally encourages competitiveness between individuals? Do you have bonuses based on individual performance, or an “employee of the month” ceremony? Identifying non-collaborative behaviors at work, be it in a team or an entire organization, can have huge cost benefits.

Have you ever considered how many processes, routines, behaviors, or habits exist in your workplace that hinder collaboration?

Short vs. Long-term Effects

It’s not unusual for management to organize conferences or hire motivational speakers to improve engagement and collaboration between employees. However, such activities are generally short-lived. You may see a sudden spike in collaborative efforts, but if nothing else changes, employees will soon fall back into old routines. Identifying and terminating non-collaborative behaviors, on the other hand, will most likely benefit the business in years to come.

For this reason, it’s far more cost-effective to focus on identifying collaborative obstacles. Once you do, set up a plan on how to manage these obstacles. This is often easier said than done. Behind every routine, process, or workflow lies a myriad of behaviors and habits. Changing a process is one thing; embedding it in the organization is another. As I’ve mentioned before, changing a behavior or habit is best done in small incremental steps. If you want to dive deeper into how to make sustainable changes, I highly recommend the book Atomic Habits by James Clear.

Conclusion

To improve teamwork, start by looking at how you unintentionally sabotage collaboration between employees. You may find it challenging at first, but I promise you it’s worth it. You’ll get a lot further removing collaborative obstacles than you will by organizing a conference or hiring motivational speakers.

If you have any questions or thoughts, feel free to reach out—I’m happy to help! Or maybe you’ve done this in your organization. If so, please share your experiences with us in the comments!

Until next time – stay curious!

Chris

August 30, 2024

No, you're not hired to do a job

Contrary to popular belief, we're not recruited to perform tasks – we're hired to solve one or several problems. There are several reasons why it’s important to understand the difference – especially if you want to make a career.

A Broader PerspectiveWhen we think we're hired to do a job, we tend to focus on our ability to perform certain tasks. Take a bus driver, for example. Their task is to get passengers from one stop to another on time. However, our perspective widens when we understand that we're hired to solve problems. Being a bus driver no longer just means transporting people, but ensuring that passengers reach their destinations safely, comfortably, and on time. It's not only a shift in focus but in mindset. Understanding that we're hired to solve problems helps us move from passive task-executors to proactive problem-solvers.

Behaviors and AttitudesIf we believe we're hired to do a job, we'll judge our performance based solely on how well we perform our tasks. How we behave or interact with others becomes less important. I've found this to be a common source of conflict between employees and managers. The former believe they've done a good job by completing their tasks, while the latter judge the employee's overall ability to solve problems for the company or organization. For instance, it's not uncommon to hear managers complain about employees who are good at their jobs but have behaviors or attitudes that stir up conflicts or negativity within their team or company. These people may be "doing their job," but what good is an employee who solves one problem but generates another? Problem-solvers, on the other hand, generally focus on how their work affects others and aim to make a positive contribution to the whole organization.

“What good is an employee who solves one problem but generates another?”

Improve your careerConsidering the above, problem-solvers tend to be appreciated by both co-workers and managers. Whenever challenges arise, they're the ones called upon to help. In my experience, these individuals are also more likely to make a career.

If you want to adopt a more problem-solving approach at work, here are three clear actions you can take:

Conclusion

1. Ask yourself what problems your tasks are meant to solve. Then focus on solving these problems effectively and efficiently.

2. Collaborate with those around you, even those you may not personally like. Remember, there's a difference between liking people and collaborating with them professionally.

3. Try to see the bigger picture. Are there other workplace-related problems you can solve? Are you unknowingly creating a problem for someone else? If so, how can you change that?

Remember, we're hired to solve problems, not create them. By shifting our perspective from task completion to problem-solving, we can significantly enhance our value in the workplace and boost our career prospects.

If you find that your efforts to solve problems are misunderstood or unappreciated, it might be time to consider a change. Working in an environment that doesn't value problem-solving will benefit neither you nor the organization.

So, take a moment to reflect on your current approach to work. Are you merely doing a job, or are you actively solving problems? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below – your insights might just help someone else transform their professional mindset!