Charlie Sheldon's Blog, page 23

December 13, 2016

Dowsing Stories That Are True

I have a lot of dowsing stories. I remember as a small child in Shutesbury Massachusetts watching this old man (he was probably not old at all of course) wandering the field next to our little house with a stick in his hand. My dad explained he was a dowser, there to find water. The well drilling company had struck three “dry holes” and so they’d called in a dowser. He found the place to drill in ten minutes. Now, I know this. Some of you will nod, recalling similar stories yourself, and the rest of you, probably most, will roll your eyes, thinking the whole dowsing thing is a primitive myth. What I love about it is there is no explanation (yet) for why it works. It works with me. I can cut a stick from a living tree and hold it and when I pass over buried water, or something, the stick turns down so strongly it will tear the bark away from the wood.

I first discovered this when I was 19 and spending a summer defoliating a power line right of way in the high hills of Western Massachusetts. We’d spray the brush with a chemical, later known as Agent Orange, and once between spells out on the line spraying the brush we played around with sticks and dowsing. One guy on the crew seemed to have the knack, and I saw the bark come off in his hands, and when I tried it the same happened to me.

Since then I’ve had way too much fun with dowsing. Most people don’t believe it, and for sure I know the chances are that whoever might be reading this is shaking their head and and muttering, but for me it works, and it works for others, too. There is no revenge so sweet as listening to abuse from a “denier” and watching him or her walk with the stick and nothing happens, and then walking before that person while touching the ends of the stick with my fingertips and seeing the stick pull, pull, pull while the “denier” goes white and gets all weird.

You can dowse for water. You can dowse for like metals, too. My dad had a friend, now long dead, he was a uranium prospector, and he said to me, very quietly, once, that most uranium is found with dowsing rods. Bob Goode, an engineer with the Port Authority, told me in 1985 that they’d take bent pieces of round rod and hold them in their hands, one in each hand, and walk until the rods turned parallel, which showed where a buried pipe lay.

Still with me, here? In 1983, I think it was, Sten, my fishing skipper, and his mate Bill Crockett undertook an effort to find Sam Bellamy’s ship the Whydah, the same year that Barry Clifford was seeking the ship. Barry found it, became famous, and became rich, and nobody ever knew about us, but we were out there first and might have found the gold had Sten followed my direction. Instead, he acted toward me like you, dear reader, must now be reacting as you read. I told him, back then, “Forget these magnetometers, give me a gold coin and I’ll stand on the stern of the boat while you range the shore and when the stick goes down, that’s where the gold and ship is.” Of course, Sten did not do this, because he did not believe me and running a boat costs money.

Your scribe

[image error]Charlie studied at Yale University (American Studies) and the University of Massachusetts (Master’s Degree in Wildlife Biology and Resource Management). He then went to sea as a commercial fisherman off New England, fishing for cod, haddock, lobster, red crab, squid, and swordfish. Active in the fight for the 200-mile Fisheries Conservation Zone, he later worked as a consultant for Fishery Management Councils, developing fishery management plans and conducting gear development projects to develop more selective fisheries. He spent 28 years working for seaports (New York, Seattle, and Bellingham) as a project and construction manager and later as an executive. In addition to overseeing habitat cleanup projects, he worked with Puget Sound Tribes establish a system whereby tribal fishing could coexist with commercial shipping in Seattle Harbor and Elliot Bay. Then, nearly ancient, he returned to sea, shipping out with the Sailor’s Union of the Pacific as an Ordinary Seaman, Able Bodied Seaman, and Bosun. Starting with commercial container vessels, on the New York to Singapore run, he finished his career aboard naval ships for Military Sealift Command. His last gig was as bosun aboard USNS Shughart, New Orleans to New York, in 2016. Always a writer, he published Fat Chance with Felony and Mayhem Press in 2005. He began working on ideas for Strong Heart long, long ago and began serious research in 2010. These days he hikes in the Olympics whenever he can, cooks for his wife, and continues to write tales in Ballard, Washington.

December 11, 2016

Imagine facing this

photo by Randa Williams

photo by Randa Williams

December 10, 2016

The Dory Men

Denny was born up Pubnico way in eighteen and ninety two,

In nineteen eleven to Boston he came, a dory man tried and true.

He fished from a dory for thirty two years till the war put an end to the trade

Moved to Chatham and fished alongshore in good weather, not much, but a living he made,

At age seventy-two he fetched up on the beach in a shack in the woods by the Bay,

Rigged gear for the fleet and cleared our bad snarls, recoiled in a tight perfect lay.

A master, was Denny, rerigging our gear, each bundle a near work of art,

With his help all that summer we landed huge trips and a half share we left in his cart.

Denny was tiny, a lone quiet man, no family he had of we knew,

We’d leave him some beer and groceries to hand in the winter when gear work was few.

Then one day next winter Denny was sick, in his shack stone cold and in pain,

To a hospital bed in Hyannis he went not far from our boat on the bay.

We’d travel to see him, kids twenty five years, he’s lost in the bed, thin and pale,

Hated that hospital food, he did, wouldn’t eat and was wasting away.

So we went to the fish store and bought us some haddock which we cooked on our boat at the dock,

Wrapped it in foil and raced to the hospital, still hot when he reached for his fork.

Oh that fish he did eat, every bit, every bite, and a smile we’d see in his eyes,

So each day we’d cook and bring him his lunch, hear his stories which Denny called lies.

Later he moved to an old people’s home in South Chatham for hospice care,

The food there was better, but Denny was failing, companionship was all he could share.

And always with Denny, those last weeks he had, three men sat with him for hours,

Old dory mates all, telling tales of the days they all shared in their youth and their power,

Harold and Peter and Edward their names, first sailing then steaming offshore,

From their dories through years of weather and waves, saw men lost in the fog evermore.

I can hear those four men, all old, one quite ill, in that pale late afternoon light,

Their memories and laughter of days now long gone when from dories they worked with such pride.

Denny came to Boston a century ago, a dory man he and his mates,

I was lucky to know him, see his art working gear, he was small but to us he was great.

His lies now all lost, the memories too, but I hold in my heart that rare sight,

Four dory men true, gathered together, keeping real their lost way of life.

Now Denny’s long gone, it’s nigh forty years since the kid in me brought gear to his shack,

And just as his memories are lost now forever mine soon will fade in the black.

When you see an old fisherman, hands like burled wood, skin pale and eyes watery and dim,

Unshaven, clothes rumpled, slumped deep in a chair, never judge there’s no glory in him,

His story not written, his memories mist, his whole way of life but a dream,

Whaler, salt banker, dory man he, now one with the unchanging sea.

December 9, 2016

Back country

Muncaster Basin

December 7, 2016

Manis Mastodon spear point

December 6, 2016

The agony of writing (2): Impatience, humiliation, despair

I’d have to say, honestly, I have been a lazy writer most of my life. Winging it. Floods of words, tons of self-edits, but always blinded by self, and hence unable to see where changes are needed. In 2003 I asked one of my oldest friends, Beth Richards, to edit a couple of my tales and she did a great job with the tiny budget I had, and from this I knew if I were to be serious I needed to find an editor and have it done properly (ie put my money where my mouth was.)

So after Christmas in 2013, having to my astonishment a 155,000 word draft of a big sprawling tale, I gathered my breath and asked Pete Wise, a classmate in the fiction class and former journalist, and a damn good editor, to have at it. A month, maybe six weeks later he comes back with a 105,000 word tale. He’d cut a THIRD of the words away, yet this much improved the story. Just about then I learned that in March 2014 the big national AWA Writer’s conference was in Seattle, so I spent a couple hundred dollars and went. I also learned that Amazon had this Breakthrough Novel contest, for new novels, with a submission date at the end of March. I went to the conference and that was an absolute eye opener. So many damn people. So many. All of them doing what I was doing, I thought. I learned enough to understand that the process of sale and production is just as intimidating as a blank page before a novelist. Based on that conference, and the seminars, and listening, I set up a web page – this one here, an earlier version – I joined Twitter and I looked at joining a writers group. These are all things I loathe, by the way, well, not a good writers group, I have one of those, the Edge of Discovery Group, made up of a few of us from Lyn Coffin’s class, including Lyn, which we started in the fall of 2015. At the same time as that national conference in March 2014 I submitted my tale to the Amazon contest, which takes 10,000 entries in a bunch of categories. First you need to get through the “pitch” round, then the first 5,000 word round, then the full book. Just about then, too, I took a consulting gig in Cleveland at the Port there, moved to Amish country, and continued with my literary fiction class via Skype.

My Amazon tale got through the pitch round and a few weeks later the first 5000 word round and I thought, maybe I have a chance, but in the quarterfinal round, now down from 10,000 to I think 2,000 entries, my tale stopped. I got some great reviews along the way and took the first 80 ages and produced a little Kindle novel on Amazon which some people liked but which didn’t move much (the being noticed issue I think).

Meanwhile, out in Cleveland, I had some time when not working, and something was nagging at me, the threads of another story, some things from the first tale needing more to be told, and so while out there I began another novel, Adrift, set a few months after the first tale and beginning with a terrible ship fire in the Gulf of Alaska, an abandoned ship, the salvage effort, the fate of the two lifeboats. Part of this tale had been in the first, because the frame I was using, stories within stories, meant that some shipwrecked sailors were being told a story by one of their shipmates, William, about the summer before, as a way to keep everyone sane. For some of my readers that worked, but for others the frame was awkward, as some felt I should just tell the wilderness journey without it being told around a fire. I guess the frame I was trying was the same as Conrad’s in Heart Of Darkness, where the real story is told while some people are in a boat waiting for the tide to reach a ship.

So while in Cleveland I wrote Adrift, a rough first draft of about 100,000 words, and then came back to Seattle. The Amazon effort had not proceeded and now I had two books. I looked at them and made a decision somewhere along the way, that summer and early fall, to change the frame of the first book, make it just the direct wilderness journey, and add to the second tale the chapters from the cast away lifeboat, with some kind of story being told but no focus on it, the real story being about what happens to the sailors and the abandoned ship. My assumption was then, and remains today, that if both books are published, either one must stand alone, and those readers who read Strong Heart will know right away the story William is telling in the second, and those readers who haven’t read Strong Heart but read Adrift might then pick up Strong Heart to read later.

By the way, all the winter before I had been querying agents about the first tale. I was early, too impatient, should have waited, as I now see that a book, as written by me, anyway, needs two to three years to evolve, season, get revised, and settle into its proper place. This long period for settling is the total difference between something that is worth reading and something not. I bet I queried 200 agents. I queried my first and only agent, from Fat Chance and the 1990s, and she was polite but refused me, and recommended someone else who essentially told me she didn’t like stories about the woods and suffering and dark places, and she, too, refused me. A couple other agents asked for the first chapter (and I mean, just one or two) and nothing happened there (as it should not have because the tale was still raw). But I kept on, being persistent, if nothing else.

I went to “pitch sessions” at another writers conference in Seattle, this one the PNW conference, at a huge cost, and aside from realizing this was mostly a scam to pay agents and others to run around from conference to conference acting self important (the wrong attitude, I know) and was again unsuccessful.

That fall, the fall 2014, I went to weapons training school in San Diego for work on military reserve ships, as it was way beyond time to earn more money. Down there, being there three weeks, I started querying small publishers, having had zero success with agents, and this effort – the small publisher chase – lasted from November 2015 until June 2015. I bet I queried 150 of them, too. Maybe more. It is a lot easier to query with internet, I am sorry to say.

I had one small publisher respond, the first of three or four, with rave reviews and asking to publish the whole thing, and I thought, great. Finally. I had queried a publisher with a focus on environmental tales, but then they wrote to me and demanded I rewrite my tale and turn it into a screed against global warming. I didn’t want any screeds in my tales, at all, so I wrote them back and said I wasn’t sure I believed in global warming as totally man-made, because orbital cycles argued we should be about to enter a new ice age. I never heard from them again. Another house, this time I am in Baltimore on a ship, the Gilliland, says they want the book so I check them out and learn they have stiffed their authors. A few others ended up being self publishing rackets, really set up to squeeze editing dollars out of you.

But, in Baltimore, ship at the dock being maintained, sort of like a warehouse with mooring lines, I had time and still felt there were threads from Strong Heart and Adrift that needed more weaving, and so I wrote another novel, Bear Valley. This one, 110,000 words, I finished in the spring of 2015. And so when I came back from Baltimore in the summer of 2015 I had three novels. I asked Pete Wise to edit Adrift, which he did, that summer. I worked on Bear Valley myself as much as I could. Actually I worked on all my drafts. The beauty of working on those military ships, they are reserve ships and you have much more time (and make less money) than while at sea, and so I disciplined myself to write every day after dinner, and on many weekends I forgave overtime to write, and as I have said many times if you stick at it you can produce a book damn fast. Once the first draft was done, about March 2015, I found a printing place, printed off the draft, bound it, at a hideous cost, and then used that to edit, which I love. I bet I have printed and bound over the last three years 30 drafts of the three books. So be it.

By the start of June, 2015, when I left the ship, I was feeling pretty good in that I had three books, now, which told one broad tale (and I feel there are more tales, out there, if I can get the time to reach for them) but I was also feeling pretty bad, because after 200+ agents and 150+ small publishers and the Amazon Breakthrough stall and two expensive and frustrating writer’s conferences I was nowhere, I mean, zero, it seemed, as far as getting published. No where.

I came back to Seattle and spent the summer fixing stuff around the house with Randa and I went back to Rambo school refresher that August, figuring I’d do another seagoing gig, wanting to work into my 70th year, needing the money, and thinking, this military ship thing is great for editing and writing and there’s more to do, on these books.

Looking back at this I am wondering why the hell I didn’t just give up. Surely an intelligent rational person would. I have never said I was the brightest bulb in the room.

You will note that never in all this did I ever consider for a second self publishing as I had done in 2004. This was for a couple reasons. One, the blow your own horn thing. If I had a publisher backing these tales then I wasn’t alone, then someone else believed, too, and had skin in the game, and this made things not totally and entirely a self absorbed exercise in ego. Two, and much more important, if you’re self published then you cannot get proper reviews, you cannot get into libraries and volume buyers, not really, and biggest of all bookstores cannot return your books if they don’t move which means bookstores don’t want self published books except maybe as consignment sales from the author and that means the author is driving all over all the time replenishing stocks.

Then, it seems, in the fall of 2015, things changed. Maybe. But that’s another story.

December 3, 2016

The agony of writing (1): Punishment, mostly

I am beginning to think that writing must be a genetic condition that influences some of us, or maybe many of us, based on the hundreds of people who pay good money for writer’s conferences all over the country. I have no idea why anyone else does this. I have no idea why I do this, and hence have concluded I must carry a defect, a sort of self-punishment and humiliation gene. Actually maybe I should amend that. It isn’t the writing itself that brings pain, at least not for me. In fact the process of writing is a form of serenity, a timeless place where things happen and flow from somewhere within the background onto a page. There is magic in that, and even more magic when things start to happen that could never have been imagined going in.

I think it is in the area of bringing your writing to public view that is where the pain lies. Even that is inaccurate, honestly, because these days there are a million ways to go public (witness this never read blog for example). No, the pain lies in the drive or belief or sickness that says, this story should be “out there” meaning as a BOOK. Of course in the last twenty years with print-on-demand systems and computers and the web it is now easy to publish a book. I think I read somewhere that there are 50,000 new novels produced each year, most of them self published. It used to be just getting a book published was a huge effort – setting type, printing, distributing. Now that is simple and almost free. Now the problem is, getting noticed. But, in either case, those among us who try to go the “traditional” route of finding a publisher and putting out books are, in most cases, doomed to a track of unrelenting pain, rejection, disappointment, and grief.

I now see I was spoiled when I sold the first full novel I wrote in about 1989. I had tried a few before then, the first back in 1971, but this one I finished, learning along the way all about the issues of how you write and rewrite and then correct, this in the days before many computers or word processors worth anything and the old dot matrix printers that ran for hours. I finished the book, sent it to an agent recommended to me by the one guy I knew who had published some books, and she picked me up, and then in a few months sold the book to Pocketbooks for a $ 5,000 advance. It was so easy (I now see).

Being encouraged, I wrote another book while waiting for the first to be sold, then another soon after, but these the agent didn’t like, they were not a series, I wanted to do what I wanted to do, I was in no writing group, had no comments, nothing. My agent fired me, eventually. She should have.

I kept on, this when self publishing was just starting, wrote more books, lined myself up with a company to self publish, designed the covers myself, and produced them after rewriting them all in 2004, mostly to get them in book form. Disaster, though, because when it came to – when it comes to – the self promotion thing, the marketing thing, the blow your own horn thing, in this sector and area I am crippled, inept, shy, lazy, afraid.

For a few years I put writing aside. I had this “big” job running around being an executive (which I hated and am entirely unsuited for because I don’t kiss ass well at all) and besides when you’re working in an office all day and writing memos and emails all day your writing gene withers and eventually dies, or mine did, but then, in the last such job I had, I knew there was nothing but a bad ending ahead, and so I thought well, if I’m going to go down I might as well learn something on the way, and so started again with research (something I had done little of before), building notebooks of ideas, themes, lessons, desires (something I had also never done, because I simply would start and a book would emerge), and then I was fired and went to sea to clear my head and earn money and soon learned that at sea there is no time to write, not working 12-14 hours a day, but plenty of time to ponder. Then, back from sea, I decided, OK, if you are serious about this, then get serious, so I entered this literary fiction course at UW and the day the class started I started my current novel, Strong Heart, though it had a different name then, and before I knew it (three months) I had a 155,000 word draft and the real work and “fun” began. I started the book Octotber 8 2013 and had the first draft done by December 30 the same year.

Remember, though, I had been spoiled, thinking, because that first book was easy, so would the rest, and here I was with one published and then republished mystery, Fat Chance, which has never really sold but is a very decent potboiler, three others self published, Guardian, Chasing Davy Jones, and Boomerang Heist, and a fourth finished and edited but in a box in my office gathering dust, Logger’s Landing. I removed Boomerang Heist because it is a book now dated and one element in it I want to use in a new book I am planning now. The other two are OK for what they were. But now I finally had a story, after getting great comments and huge reactions and hiring a editor and having great insights from people who knew what they were doing, and so, in the late winter of 2014, I began the process of getting this new book out.

I thought it would be easy. Instead I found nothing but pain, grief, humiliation, and rejection. Lots and lots of rejection. And it’s an ongoing story.

Punishment, mostly

I am beginning to think that writing must be a genetic condition that influences some of us, or maybe many of us, based on the hundreds of people who pay good money for writer’s conferences all over the country. I have no idea why anyone else does this. I have no idea why I do this, and hence have concluded I must carry a defect, a sort of self-punishment and humiliation gene. Actually maybe I should amend that. It isn’t the writing itself that brings pain, at least not for me. In fact the process of writing is a form of serenity, a timeless place where things happen and flow from somewhere within the background onto a page. There is magic in that, and even more magic when things start to happen that could never have been imagined going in.

I think it is in the area of bringing your writing to public view that is where the pain lies. Even that is inaccurate, honestly, because these days there are a million ways to go public (witness this never read blog for example). No, the pain lies in the drive or belief or sickness that says, this story should be “out there” meaning as a BOOK. Of course in the last twenty years with print-on-demand systems and computers and the web it is now easy to publish a book. I think I read somewhere that there are 50,000 new novels produced each year, most of them self published. It used to be just getting a book published was a huge effort – setting type, printing, distributing. Now that is simple and almost free. Now the problem is, getting noticed. But, in either case, those among us who try to go the “traditional” route of finding a publisher and putting out books are, in most cases, doomed to a track of unrelenting pain, rejection, disappointment, and grief.

I now see I was spoiled when I sold the first full novel I wrote in about 1989. I had tried a few before then, the first back in 1971, but this one I finished, learning along the way all about the issues of how you write and rewrite and then correct, this in the days before many computers or word processors worth anything and the old dot matrix printers that ran for hours. I finished the book, sent it to an agent recommended to me by the one guy I knew who had published some books, and she picked me up, and then in a few months sold the book to Pocketbooks for a $ 5,000 advance. It was so easy (I now see).

Being encouraged, I wrote another book while waiting for the first to be sold, then another soon after, but these the agent didn’t like, they were not a series, I wanted to do what I wanted to do, I was in no writing group, had no comments, nothing. My agent fired me, eventually. She should have.

I kept on, this when self publishing was just starting, wrote more books, lined myself up with a company to self publish, designed the covers myself, and produced them after rewriting them all in 2004, mostly to get them in book form. Disaster, though, because when it came to – when it comes to – the self promotion thing, the marketing thing, the blow your own horn thing, in this sector and area I am crippled, inept, shy, lazy, afraid.

For a few years I put writing aside. I had this “big” job running around being an executive (which I hated and am entirely unsuited for because I don’t kiss ass very well) and besides when you’re working in an office all day and writing memos and emails all day your writing gene withers and eventually dies, or mine did, but then, in the last such job I had, I knew there was nothing but a bad ending ahead, and so I thought well, if I’m going to go down I might as well learn something on the way, and so started again with research (something I had done little of before), building notebooks of ideas, themes, lessons, desires (something I had also never done, because I simply would start and a book would emerge), and then I was fired and went to sea to clear my head and earn money and soon learned that at sea there is no time to write, not working 12-14 hours a day, but plenty of time to ponder. Then, back from sea, I decided, OK, if you are serious about this, then get serious, so I entered this literary fiction course at UW and the day the class started I started my current novel, Strong Heart, though it had a different name then, and before I knew it (three months) I had a 155,000 word draft and the real work and “fun” began. I started the book Ocotber 8 2013 and had the first draft done by December 30 the same year.

Remember, though, I had been spoiled, thinking, because that first book was easy, so would the rest, and here I was with one published and then republished mystery, Fat Chance, which has never really sold but is a very decent potboiler, three others self published, Guardian, Chasing Davy Jones, and Boomerang Heist, and a fourth finished and edited but in a box in my office gathering dust, Logger’s Landing. I removed Boomerang Heist because it is a shitty book. The other two are OK for what they were. But now I finally had a story, after getting great comments and huge reactions and hiring a editor and having great insights from people who knew what they were doing, and so, in the late winter of 2014, I began the process of getting this new book out.

I thought it would be easy. Instead I found nothing but pain, grief, humiliation, and rejection. Lots and lots of rejection. But that’s another story.

November 9, 2016

Out of America (modern man)

July 23, 2015 · by German Dziebel · in Amerindians

Science DOI: 10.1126/science.aab3884

Genomic evidence for the Pleistocene and recent population history of Native Americans

Raghavan, Maanasa, Matthias Steinrücken, Kelley Harris, Stephan Schiffels, Simon Rasmussen, Michael DeGiorgio, Anders Albrechtsen, …Eske Willerslev.

How and when the Americas were populated remains contentious. Using ancient and modern genome-wide data, we find that the ancestors of all present-day Native Americans, including Athabascans and Amerindians, entered the Americas as a single migration wave from Siberia no earlier than 23 thousand years ago (KYA), and after no more than 8,000-year isolation period in Beringia. Following their arrival to the Americas, ancestral Native Americans diversified into two basal genetic branches around 13 KYA, one that is now dispersed across North and South America and the other is restricted to North America. Subsequent gene flow resulted in some Native Americans sharing ancestry with present-day East Asians (including Siberians) and, more distantly, Australo-Melanesians. Putative ‘Paleoamerican’ relict populations, including the historical Mexican Pericúes and South American Fuego-Patagonians, are not directly related to modern Australo-Melanesians as suggested by the Paleoamerican Model.

Nature (2015) doi:10.1038/nature14895

Genetic evidence for two founding populations of the Americas

Skoglund, Pontus, Swapan Mallick, Maria C. Bortolini, Niru Channagiri, Tabita Hunemeier, Maria L. Petzl-Erler, Francisco M. Salzano, Nick Patterson, and David Reich.

Genetic studies have consistently indicated a single common origin of Native American groups from Central and South America. However, some morphological studies have suggested a more complex picture, whereby the northeast Asian affinities of present-day Native Americans contrast with a distinctive morphology seen in some of the earliest American skeletons, which share traits with present-day Australasians (indigenous groups in Australia, Melanesia, and island Southeast Asia). Here we analyse genome-wide data to show that some Amazonian Native Americans descend partly from a Native American founding population that carried ancestry more closely related to indigenous Australians, New Guineans and Andaman Islanders than to any present-day Eurasians or Native Americans. This signature is not present to the same extent, or at all, in present-day Northern and Central Americans or in a ~12,600-year-old Clovis-associated genome, suggesting a more diverse set of founding populations of the Americas than previously accepted.

Whole-genome and ancient DNA studies continue to topple conventional paradigms, befuddle academic researchers and fulfill out-of-America predictions. The two brand new studies by teams from the Reich lab at Harvard and the Willerslev lab at the University of Copenhagen postulate no fewer than three ancestry components in Amerindians related to three major population clusters in the Old World. Just 10 years ago the opinion was split between those scholars who imagined genetic and cultural continuity between Amerindians and East Asians and the peopling of the Americas at 15,000 years ago and those who postulated discontinuity from the ancestors of modern East Asians and the isolation of proto-Amerindians for some 15,000 years in Beringia. The latter model known as the “Beringian Standstill Hypothesis” (Tamm et al. 2007) sought to explain the presence of unique genetic signatures in modern Amerindians which required time and geographic isolation from the ancestral East Asian pool to accrue and stabilize. The Yana Rhinoceros Horn site located in close proximity to the East Siberian Sea shore and dated at 30,000 YBP provided the material evidence and the lowest chronological horizon for a proto-Amerindian source population presumably locked in a northern refugium during the LGM times and waiting for the ice shield to melt before spreading into the New World. While the two mental models differed in the extent to which they allowed for discontinuity between East Asians and Amerindians, they both imagined a homogeneous East Asian gene pool yielding an even more homogeneous Amerindian population.

With the sequencing of the DNA from the Mal’ta boy located in South Siberia and dated at 24,000 YBP, this thinking proved to be false. The Mal’ta site itself was located thousands of miles south of the mouth of the Yana River. More importantly, its DNA showed affinity to modern Amerindians and West Eurasians to the exclusion of modern East Asians (Raghavan et al. 2014). So, during the LGM times distinct Amerindian ancestry was already detectable in a geographically northeast Asian sample, while East Asian ancestry was not. Contrary to the prediction of both the East Asian Continuity and the Beringian Standstill models, a distinctive Amerindian genetic signature predated a distinctive East Asian genetic signature in the heart of Siberia and its closest affinities were with modern Europeans and not East Asians. Amerindians turned out to be older, more heterogeneous and less East Asian than everybody thought. The academic community responded to this puzzling finding by postulating an extinct “Ancient Northern European” (ANE) population that admixed with an East Asian population to generate ancestors of modern Amerindians. The ANE signature was later also found west of the Urals in ancient Kostenki DNA at 36,000 YBP (Seguin-Orlando et al. 2014; also covered here) as well as across a wide range of modern European, Middle Eastern and Caucasus populations including the putative Yamnaya ancestors of Indo-European speakers (Haak et al. 2015). But the best living example of that ancient Eurasian population continue to be Amerindians. The genetic impact of ANE on West Eurasians is so significant that all of the ancient samples discovered in Europe, from La Brana foragers to Stuttgart farmers, as well as all of the modern European populations score closer to modern Amerindians than to modern East Asians or Australo-Melanesians.

Up until now, Australo-Melanesians have never been a factor in the population genetic theories of the peopling of the Americas. Whether imagined as the earliest and sovereign wave of modern humans emanating from Africa along a “southern” migratory route or an early offshoot of an East Asian population, Australo-Melanesians have always been considered too old in terms of their divergence time and too southern in their geographic distribution to play a role in the peopling of the Americas via the Bering Strait bridge. Linguists, ethnologists, folklorists and ethnomusicologists, on the other hand, have long pointed out suggestive parallels between grammatical traits, mythological motifs, rituals and musical styles and instruments between some New World regions (especially, Amazonia but also North America) and the Sahul (see more here).

Physical anthropologists, too, advanced an argument that the earliest craniological material from the Americas is closer to Australo-Melanesians than to modern Amerindians or East Asians. This observation was so consistent across their Paleoindian sample that it warranted a formalization into a theory of two large-scale migrations to the Americas: the first one followed a coastal route and brought populations related to Australo-Melanesians from the deep south of the Circumpacific region, while the second one was derived from an inland source in northeast Asia (Neves & Hubbe 2005). Historic Fuegians and Pericues from Baha California were presented as the only surviving examples of the ancient Australo-Melanesian craniological pattern in the Americas (Gonzalez-Jose et al. 2003). However, ancient mtDNA extracted from Paleoindian skulls has invariably showed close affinities to all of modern Amerindians, thus undermining claims for a two-migration scenario (see, e.g., Chatters et al. 2014). Raghavan et al. (2015) re-examined the Paleoindian, Fuegian and Pericue craniological dataset and rejected the original conclusion:

“The results of analyses based on craniometric data are, thus, highly sensitive to sample structure and the statistical approach and data filtering used. Our morphometric analyses suggest that these ancient samples are not true relicts of a distinct migration, as claimed, and hence do not support the Paleoamerican model.”

But while the Australo-Melanesian hypothesis cannot be defended using craniological material, Skoglund et al. (2015) and Raghavan et al. (2015) have now furnished whole-genome evidence for a distinct Australo-Melanesian, or Oceanic ancestry in modern Amerindians. (Note that, ironically, the craniologists failed to see the Australo-Melanesian signature in modern Amerindian skulls.) Raghavan et al. (2015) report results from their in-depth D statistic analysis of shared drift between various populations:

“We found that some American populations, including the Aleutian Islanders, Surui, and Athabascans are closer to Australo-Melanesians compared to other Native Americans, such as North American Ojibwa, Cree and Algonquin, and the South American Purepecha, Arhuaco and Wayuu (fig. S10). The Surui are, in fact, one of closest Native American populations to East Asians and Australo-Melanesians, the latter including Papuans, non-Papuan Melanesians, Solomon Islanders, and South East Asian hunter-gatherers such as Aeta.”

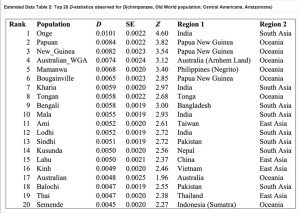

Two examples from their Fig. S10 can be seen below.

What it shows is that some Amerindian populations markedly shift in the direction of Papuans or Aeta compared to the majority of Amerindians. Importantly, this shift affects some of the same populations (e.g., Aleutians and Saqqaq) that also shift toward Han and Koryaks but, remarkably, the Australo-Melanesian pull is stronger than the East Asian pull! (see below from Fig. S10 in Raghavan et al. 2015, where negative D values are lower when Han and Koryaks are compared to Amerindians than when Papuans and Aeta are compared to them).

Importantly, the Australo-Melanesian shift is displayed by populations from both South America and North America, so it’s a low-frequency but pan-American phenomenon. Raghavan et al. (2013) showed that some North American populations are more East Asian shifted and less ANE-shifted than Central and South American populations. Now, they present evidence that those populations are more Australo-Melanesian-shifted than East Asian-shifted.

Working with a different sample, Skoglund et al. (2015) echo Raghavan et al. (2015) findings. They write:

“Andamanese Onge, Papuans, New Guineans, indigenous Australians and Mamanwa Negritos from the Philippines all share significantly more derived alleles with the Amazonians (4.6 . Z . 3.0 standard errors (s.e.) from zero). No population shares significantly more derived alleles with the Mesoamericans than with the Amazonians.”

Extended Data Table 2 in Skoglund et al. (2015) (see below) shows this excess of Australo-Melanesian alleles (Z values positive) in Amazonians (Surui, Karitiana and Xavante) compared to Central American Indians (as proxies for other Amerindians including the 12,000-year-old Anzick sample from Montana).

Interestingly, the “Australo-Melanesian” footprint in the Old World is geographically broad spanning South Asia, Southeast Asia as well as the Sahul. It’s clearly the pre-Mongoloid and pre-Austronesian “substrate” in the eastern provinces of the Old World.

Predictably, Skoglund et al. (2015) and Raghavan et al. (2015) struggled to interpret these results. Raghavan et al. (2015) concluded:

“The data presented here are consistent with a single initial migration of all Native Americans and with later gene flow from sources related to East Asians and, more distantly [this statement is contradicted by their own data, as I showed above. – G.D.], Australo-Melanesians.”

But the conclusion from Skoglund et al (2015) is radically different:

“[O]ur results suggest that the genetic ancestry of Native Americans from Central and South America cannot be due to a single pulse of migration south of the Late Pleistocene ice sheets from a homogenous source population, and instead must reflect at least two streams of migration or alternatively a long drawn out period of gene flow from a structured Beringian or Northeast Asian source. The arrival of Population Y ancestry in the Americas must in any scenario have been ancient: while Population Y shows a distant genetic affinity to Andamanese, Australian and New Guinean populations, it is not particularly closely related to any of them, suggesting that the source of population Y in Eurasia no longer exists…”

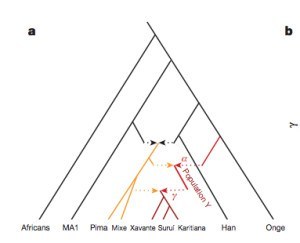

Skoglund et al. (2015) seem to be more reasonable in their judgment. Their phylogenetic tree with admixture arrows (see on the left) captures well the ever-more-complex prehistory of the New World.

It used to be that Amerindians were depicted as a simple offshoot of a Han-like population (see the tree on the right, from McEvoy et al. 2010, Fig. 1). The branch connecting them to East Asians has always been long but it was interpreted as the effect of a bottleneck induced by the Beringian Standstill and subsequent further isolation in a newly-colonized continent. Now, Amerindian ancestry, whether northern or southern, spans the whole gamut of extra-African genetic diversity. In addition, the Australo-Melanesian link in the New World is clearly connected to the discovery of a stronger Denisovan signal in Amerindians vs. East Asians (Qin & Stoneking 2015), which suggests that Amerindians must be older than the LGM time frame entertained by Raghavan et al. (2015).

While Raghavan et al. (2015) dismiss the Australo-Melanesian hypothesis advanced by craniologists, Skoglund et al. hope that direct DNA analysis of the Paleoindian material from Amazonia will yield support to their finding. Importantly, just like the mythical “Ancient Northern Eurasian” (ANE) population to which the Mal’ta boy belonged is claimed to no longer exist in the Old World, the ancient Population Y ceased to exist, too. But apparently their descendants are well and alive in the New World.

Out-of-America can end the torturous guesswork that the population genetic community is engaged in trying to explain the high allelic diversity and the diverse set of continental connections to the Old World exhibited by Amerindian genomes. Phenomenal linguistic and cultural diversity in the Americas (with its well-documented connections to West Eurasia, East Asia and the Sahul) now receives full corroboration from population genetics. One pulse from a single, structured ancient Amerindian population followed by long-range migrations to the Sahul, Middle East/Caucasus, Europe and East Asia around 60-40,000 YBP provides an elegant explanation to the observed cross-disciplinary pattern.