Roland Kelts's Blog, page 73

April 27, 2011

Monkey takes Manhattan

April 26, 2011

Monkey in Brooklyn

April 19, 2011

See you in Seattle

Roland Kelts is a half-Japanese American writer, editor and lecturer who divides his time between New York and Tokyo. He is the author of

Roland Kelts is a half-Japanese American writer, editor and lecturer who divides his time between New York and Tokyo. He is the author of

April 9, 2011

Distance and disaster

Distance and disaster

I was in Oregon when the quake and waves first struck Japan last month. More specifically, I was in a little farmhouse-style comfort food eatery called Belly in downtown Eugene, sipping a martini. I had landed roughly 24 hours earlier from Tokyo. I had given two talks, answered questions, and chatted with students and faculty from the university that day, mostly about my usual topics: Japan's contemporary popular culture, its images, and its apocalyptic visual narratives.

I was speaking on the 66th anniversary of the fire-bombings of Tokyo, March 10, 1945. Discussing destruction seemed apt.

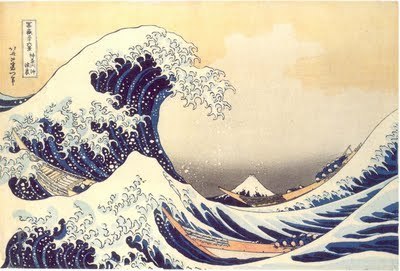

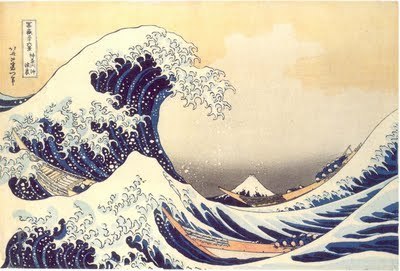

Japanese popular culture has long depicted disasters, I'd said, from Katsuhika Hokusai's world-renowned "Great Wave off Kanagawa," an ukiyo-e print depicting a tsunami, to Godzilla films in the 1950s and now-classic anime features like Akira, Evangelion and Grave of the Fireflies. Even Hayao Miyazaki's last film, Ponyo, animated the destructive powers of a tsunami in a small seaside village. The audience nodded, took notes, smiled appreciatively. As usual when I'm speaking to Americans in the US, the Japan I know and inhabit felt both curiously intimate and terribly far away.

For over a decade, I have been traveling between two cities in two countries, both of which have come to feel like 'homes' to me, certainly more than any other towns or nations in the world. Family and friends are at both ends of that journey, and they are all dear to me. I have had some kind of residence in New York since 1991; since 2000, the same has been true of Tokyo. What started as a nervy, sometimes jarring or exhilarating experience—exchanging one country and culture for another, adapting on the fly to different cultural expectations and behaviors, refraining from bowing in NYC, resisting my wayward American gait in Tokyo—hasn't exactly become commonplace, but neither does it feel quite as glamorous or disruptive as it once did.

But when I'm arriving in a city in which I don't live, the disjunctions of jet lag are sharpened, and a sense of detachment is an almost willful gesture, a way of retreating into the shell of the self to observe the new world, its contours and shapes and signage.

I was in that state, that frame of suspended mental pauses between scenes, when I got the news about Japan. I immediately went online, clicking from site to site, sending emails pinging across the Pacific and around the US. The great tsunami wave sweeping and then oozing across farmland, sucking down houses and trees, ships and automobiles, was probably the apotheosis of apocalyptic imagery, at least as divined by the natural world.

After it became clear that my family and friends were okay—or not okay, not even well, but unharmed physically—I tried to get on with work and life in Oregon, and during subsequent trips to Los Angeles and New York. Living and working in two countries with disparate time zones means that two clocks tick in your brain. At midnight in one, the color of the sky in the other at midday spools like film through your mind. You start to feel like you're here and there simultaneously, working to meet a deadline as the afternoon sky dims in your here here, because you know that morning in your there there is fast approaching. And if you don't finish on time, no matter where you are, you'll be late.

But it's a delusion, of course—silly wabbit, tricks are for kids, as the old American cereal commercial said. You're never there when you're here. The desire to bridge distances and difference—via art and language, stories, music and cuisine—embodies the pathos of impossibility. And the technologies we have devised, the supersonic jets, the emails and web cams and Skype calls, are belittled in an instant by the stone physicality of the world. When something happens over there, something transformative and overwhelming, it didn't happen to you here.

I am back on the road again, presenting on Japan's popular culture in Baltimore, DC and Seattle. This week, I'm in London. During my talks, Hokusai's "Great Wave" flashes upon the projection screens above and behind me. It looks more menacing now. And at night in my hotel rooms, I sit in front of smaller screens, clicking through updates and real-time TV broadcasts, absorbed in tracking time through information, feeling stuck and very local: roughly thrust by disaster back into my only home—the organs, skin, blood and bones I will inhabit till death. I've been made bereft by distance, yearning so hard in these times of heartache to bridge it.

Disaster and Distance

Distance and disaster

I was in Oregon when the quake and waves first struck Japan last month. More specifically, I was in a little farmhouse-style comfort food eatery called Belly in downtown Eugene, sipping a martini. I had landed roughly 24 hours earlier from Tokyo. I had given two talks, answered questions, and chatted with students and faculty from the university that day, mostly about my usual topics: Japan's contemporary popular culture, its images, and its apocalyptic visual narratives.

I was speaking on the 66th anniversary of the fire-bombings of Tokyo, March 10, 1945. Discussing destruction seemed apt.

Japanese popular culture has long depicted disasters, I'd said, from Katsuhika Hokusai's world-renowned "Great Wave off Kanagawa," an ukiyo-e print depicting a tsunami, to Godzilla films in the 1950s and now-classic anime features like Akira, Evangelion and Grave of the Fireflies. Even Hayao Miyazaki's last film, Ponyo, animated the destructive powers of a tsunami in a small seaside village. The audience nodded, took notes, smiled appreciatively. As usual when I'm speaking to Americans in the US, the Japan I know and inhabit felt both curiously intimate and terribly far away.

For over a decade, I have been traveling between two cities in two countries, both of which have come to feel like 'homes' to me, certainly more than any other towns or nations in the world. Family and friends are at both ends of that journey, and they are all dear to me. I have had some kind of residence in New York since 1991; since 2000, the same has been true of Tokyo. What started as a nervy, sometimes jarring or exhilarating experience—exchanging one country and culture for another, adapting on the fly to different cultural expectations and behaviors, refraining from bowing in NYC, resisting my wayward American gait in Tokyo—hasn't exactly become commonplace, but neither does it feel quite as glamorous or disruptive as it once did.

But when I'm arriving in a city in which I don't live, the disjunctions of jet lag are sharpened, and a sense of detachment is an almost willful gesture, a way of retreating into the shell of the self to observe the new world, its contours and shapes and signage.

I was in that state, that frame of suspended mental pauses between scenes, when I got the news about Japan. I immediately went online, clicking from site to site, sending emails pinging across the Pacific and around the US. The great tsunami wave sweeping and then oozing across farmland, sucking down houses and trees, ships and automobiles, was probably the apotheosis of apocalyptic imagery, at least as divined by the natural world.

After it became clear that my family and friends were okay—or not okay, not even well, but unharmed physically—I tried to get on with work and life in Oregon, and during subsequent trips to Los Angeles and New York. Living and working in two countries with disparate time zones means that two clocks tick in your brain. At midnight in one, the color of the sky in the other at midday spools like film through your mind. You start to feel like you're here and there simultaneously, working to meet a deadline as the afternoon sky dims in your here here, because you know that morning in your there there is fast approaching. And if you don't finish on time, no matter where you are, you'll be late.

But it's a delusion, of course—silly wabbit, tricks are for kids, as the old American cereal commercial said. You're never there when you're here. The desire to bridge distances and difference—via art and language, stories, music and cuisine—embodies the pathos of impossibility. And the technologies we have devised, the supersonic jets, the emails and web cams and Skype calls, are belittled in an instant by the stone physicality of the world. When something happens over there, something transformative and overwhelming, it didn't happen to you here.

I am back on the road again, presenting on Japan's popular culture in Baltimore, DC and Seattle. This week, I'm in London. During my talks, Hokusai's "Great Wave" flashes upon the projection screens above and behind me.

It looks more menacing now. And at night in my hotel rooms, I sit in front of smaller screens, clicking through updates and real-time TV broadcasts, absorbed in tracking time through information, feeling stuck and very local: roughly thrust by disaster back into my only home—the organs, skin, blood and bones I will inhabit till death. I've been made bereft by distance, yearning so hard in these times of heartache to bridge it.

April 8, 2011

April 7, 2011

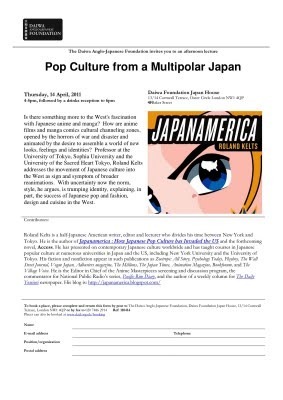

Japanamerica in London next week

Sign In HERE

Lecture

Pop Culture from a Multipolar JapanIs there something more to the West's fascination with Japanese anime and manga? How are anime films and manga comics cultural channeling zones, opened by the horrors of war and disaster and animated by the desire to assemble a world of new looks, feelings and identities? Lecturer at the University of Tokyo, Sophia University and the University of the Sacred Heart Tokyo, Roland Kelts addresses the movement of Japanese culture into the West as sign and symptom of broader reanimations. With uncertainty now the norm, style, he argues, is trumping identity, explaining, in part, the success of Japanese pop and fashion, design and cuisine in the West.

Roland Kelts is a half-Japanese American writer, editor and lecturer who divides his time between New York and Tokyo. He is the author of Japanamerica : How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US and the forthcoming novel, Access. He has presented on contemporary Japanese culture worldwide and has taught courses in Japanese popular culture at numerous universities in Japan and the US, including New York University and the University of Tokyo. His fiction and nonfiction appear in such publications as Zoetrope: All Story, Psychology Today, Playboy, The Wall Street Journal, Vogue Japan, Adbusters magazine, The Millions, The Japan Times, Animation Magazine, Bookforum, and The Village Voice. He is the Editor in Chief of the Anime Masterpieces screening and discussion program, the commentator for National Public Radio's series, Pacific Rim Diary, and the author of a weekly column for The Daily Yomiuri newspaper. Click here for his

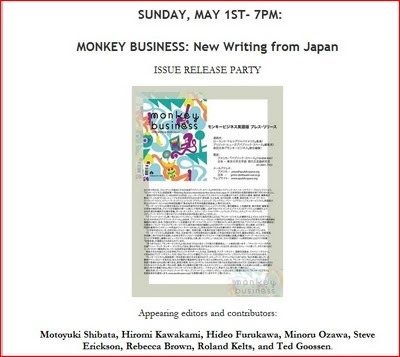

Japanese Press Release for the MONKEY

April 6, 2011

PEN American Center - Word from Asia: Contemporary Writing from Japan

Word from Asia: Contemporary Writing from Japan

[image error]When: Saturday, April 30

Where: Asia Society, 725 Park Ave., New York City

What time: 2:30–4 p.m.

With Joshua Beckman, Rebecca Brown, Hiromi Kawakami, Minoru Ozawa, andMotoyuki Shibata

Free and open to the public. No reservations required.

Co-sponsored by Asia Society, The Japan Foundation, Dalkey Archive, and Granta

Come celebrate the work of some of the most innovative novelists, poets and translators from Japan, Korea and Pakistan. Hear about the challenges (and the pleasures) of writing and translating across national, cultural, and linguistic borders.

One of Japan's most influential cultural critics and translators, Motoyuki Shibata, leads a discussion with four innovative and hybrid literary masters. They'll talk about their most formative Japanese-American influences, ranging from science fiction to manga (comics and print cartoons) and renga (collaborative poetry) to help launch the debut issue of Monkey Business: New Voices from Japan, the first of what will be an annual English-language edition of the acclaimed Japanese literary magazine.

MORE INFO HERE: PEN American Center - Word from Asia: Contemporary Writing from Japan