Harry Harrison's Blog, page 2

March 18, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 2: The Second World War

Harry Harrison received his draft notice on his eighteenth birthday in March 1943. As he put it, the letter marked the end of his childhood and the beginning of his adult life. He was told to report to Grand Central Palace in Manhattan for a physical examination which would determine whether he was fit enough to join the military. In his memoir, Harrison writes about this experience with grim humour, but it’s clear it was an unpleasant and dehumanising one. “Was this deliberate sadism?” he asks. “Probably not. Just the military’s total indifference to the individual as a thinking, separate human being.”

Certified fit, Harrison was ordered to report to Camp Upton on Long Island. He spent a month there, finding escape in the novels of H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, and then learned he was to join the Army Air Corps. Perhaps it was just luck or perhaps learning about aircraft instruments at night school had paid off. Either way, as he ironically puts it, “I never saw an aircraft instrument again.”

He was sent for basic training to Keesler Field, Biloxi, Mississippi. It was July, ninety degrees Fahrenheit (32°C) and humid. The young soldiers were subjected to intense physical exercise and mental stress to see if they would break. Harry Harrison discovered in himself an instinct for survival and also a streak of stubbornness – he would not let the bastards grind him down. These two things got him through the ordeal with heat rash being his biggest complaint. The physical training that reduced him to “…a 135 pound weakling, had built me back up to a fit, tanned and strong 160 pounds.”

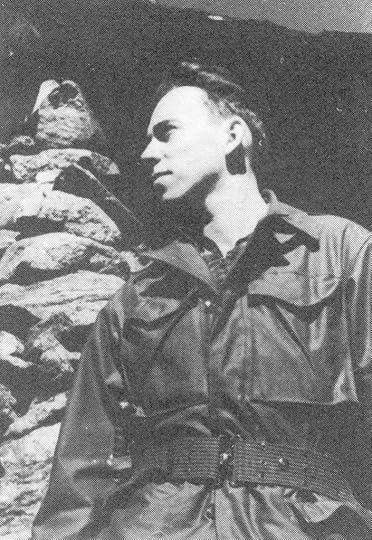

Harry Harrison in military uniform

Harry Harrison in military uniformHe couldn’t become an aircraft pilot because of his eyesight – he’d worn glasses since he was young; but there was a possibility that he could become a glider pilot. When his orders finally came through, Harrison discovered that he was being sent to a ‘secret military school’ at Lowry Field in Denver, Colorado. This was a result of his having scored 156 out of 160 in the Mechanical Aptitude test – “The best score I ever got in my life!” It was almost the end of 1943 when he shipped out.

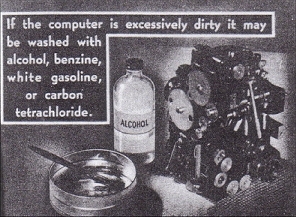

Keep Your Computer Well-GreasedAt Lowry Field, Harry Harrison was trained to operate and maintain a Sperry Mark 3 Computing Gunsight. He described it as “…a lumpish black object with an angled piece of glass on its top that was framed by a metal cage. Nothing about it resembled any device I had ever seen before. I realized with a touch of panic that I had a lot to learn.” And “…the gunsight was mounted in the top of a tub-like revolving turret, ominously close to two gigantic machine guns. There was a complex handgrip and a folding seat for the gunner … With the aid of the computer the gunner aimed and fired the two .50 caliber guns that framed his head.” This was the Power Operated Turret, and the young trainees would also need to become gunsmiths, learning how to service the machine guns.

When we think of computers today, we think of laptop devices with microchips inside. The ‘computing gunsight’ that Harrison worked on was nothing like that. It was an analog computer, not a digital one.

“Gears, rollers, gear trains and ball cages, cams and cam followers and plenty of grease made these remarkable machines function – and function well,” Harrison wrote in an unpublished text on this type of computer.

There are some excellent images of the gunsight computer on the Glenn’s Museum website here. Click on the images to enlarge them.

By the end of Spring 1944, Harrison had finished his training. “I was now the proud owner of a triangular patch with a bomb on it – representing my new ranking as an armaments specialist. I sewed it onto my sleeve.” Officially, he was a Power Operated Turret and Computing Gunsight Specialist – 678. After a year’s experience he could add a three on the end to become 678-3, an indication that he was ‘skilled.’ “Having qualified on a number of weapons during training I also wore a sharpshooter’s medal on my pocket with pendant details: caliber .50, Garand rifle, Riesling submachine gun.”

Harrison was sent to Kelly Field, San Antonio to await his next assignment. That was to Laredo Air Force Base, an aerial gunnery school with an associated gunnery range, in Laredo, Texas, near the Mexican border. This would be his ‘home’ until the end of the war.

The purpose of the base was to train aerial gunners. Harrison was assigned to the ground range where students fired live rounds for the first time. A turret with two caliber .50 guns was mounted to the back of a six-by-six Chevy truck. Initially, it was his job to service and adjust the computing gunsight between the guns. Then he was given the job of servicing the guns as well. And then he took on the role of instructor. He also ended up driving the truck, despite the fact that he’d never driven even a car before – “I almost turned it over!”

The pounding of the massive guns damaged Harrison’s hearing and the food on the base was terrible, but at weekends he was allowed out on a pass and could enjoy the Mexican food and drink. Daily life was monotonous, and he compared it to serving time in prison: you serve one day at a time and look forward to your eventual release. At some point, to relieve the boredom, he attended a lecture about the ‘artificial language’ Esperanto. He picked up a book called Learn Esperanto in 17 Easy Lessons and learned enough to be able to correspond with other Esperantists. He was barely aware of the progress of the war in Europe – until the training base in Laredo was shut down.

Military PoliceHarrison was transferred to another gunnery school – Tyndall Field in Panama City, Florida – but when he got there, their gunnery training was shut down too. His expertise was no longer needed. By this stage, he had achieved the rank of sergeant. The only opening available was in the Military Police.

The other MPs were from south of the Mason Dixon line. As a Yankee from New York, Harrison wasn’t exactly welcome in their ranks. They decided to put him in charge of the stockade that housed black prisoners. The Army was segregated and so were their prisons. Harry was given a shotgun to guard his prisoners, and it was their job to go out in a garbage truck and collect the trash. And to add insult to injury, he also had to eat in the black mess hall. It could have been a nightmare situation, but it turned out to be the exact opposite.

Most of the black prisoners were also from the north. And many of them had ended up in the stockade for talking back to ‘superior’ officers. They just wanted to serve out the rest of their time in the military and get clean discharge. They didn’t cause Harrison any problems. And the cook in the black mess hall had been salad chef at the Waldorf Astoria in New York. He could take the basic ingredients the army provided and turn it into something that, unlike most military meals, was good to eat.

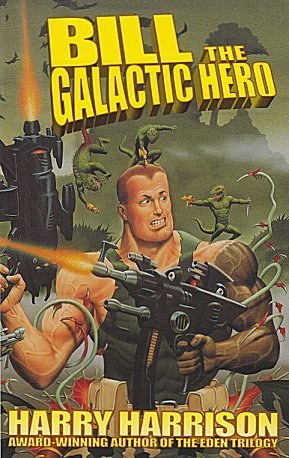

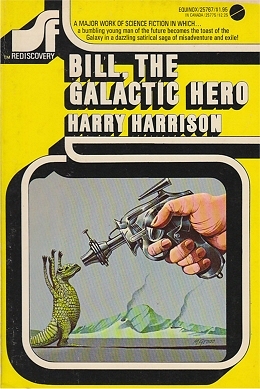

Artwork: Michael Gross

Artwork: Michael GrossIn 1946, Harry Harrison received his discharge and returned to New York as an adult who was “…totally adjusted to military life – and totally unprepared for my future as a civilian.” He took back with him a dislike of the military that stayed with him for the rest of his life. “If you read Bill, the Galactic Hero you’ll see how I feel about the army!” He also claimed to have learned something else from the black soldiers he supervised. “I was the first white person in New York to use the word motherf*cker!”

Next: Cartoonist & Illustrator

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

March 12, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 1: Early Life

Harry Harrison was born on the 12th March 1925 in Stamford, Connecticut. The name on his birth certificate was Henry Maxwell Dempsey, but he didn’t know this until he first applied for a passport as an adult. He was the only child of Henry Leo Dempsey and Ria Helen Dempsey (nee Kirjassoff). Henry Leo Dempsey was born in Oneida, New York, in 1888. He was a compositor and proof-reader working on the New York Daily News and elsewhere. Ria Kirjassoff was born in Riga, Latvia and grew up in St. Petersburg, Russia until her family emigrated to the United States. She was schoolteacher until she married.

In his memoir, Harry Harrison says little about his childhood except that it was ‘miserable.’ The Great Depression began in 1929 with the Wall Street stock market crash in October of that year. The Harrison family had moved to Brooklyn, New York in 1927, where Henry Leo adopted the surname of his stepfather, Billy Harrison. They moved to Queens in 1930. Like many other families, they struggled to survive financially and moved home – sometimes more than once in a year – to stay ahead of their creditors. During that period, a family could move into an apartment and pay a month’s rent. They would then stay for another three months, owing the rent, and then pack up all of their belongings and the ice man would come with his cart and move everything to a new apartment where the cycle would begin again.

Harry Harrison aged six

Harry Harrison aged sixThere was one thing that helped alleviate the misery of those difficult early years. Harrison recalled the pleasure of discovering science fiction – which he referred to as ‘catching the rapture’ – in the introduction to World of Wonder (1969): “Science fiction is great stuff when you are young and has an impact not unlike the one received when putting the finger into a live electric light socket. Though for the most part I have only the vaguest of childhood memories, I do have one clear and sharp memory – that of reading my first science fiction story. The ancient cathedral-roofed radio, the sun in the window, the very texture of the carpet on which I lay, are all as clear as yesterday. My father gave me a copy of the old large-sized Amazing Stories, which appeared even larger in my seven-year-old hands, until it became a very bedsheet of a magazine. I plunged into those rocket ship filled, time machine, ancient alien, strange invention stuffed pages and emerged with my whole life changed. For the better, I sincerely hope, but changed it was indeed.”

In an afterword to Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419AD, Harrison wrote how the novel paved the way for the Buck Rogers comic strip – and the radio show that began with the famous words Buck Rogers in the Twenty-fifth Cent-tour-eeeeee. It’s clear from what he writes that Harrison enjoyed the comic strips more than Nowlan’s novel. And who but a young science fiction fan would recall something like this: “Woolworths did a good line of Buck Rogers devices, everything from small lead spaceships to stamped steel rocket guns. Mine broke instantly after purchase and I can’t remember if it clacked, popped or emitted a suction dart. The space helmet I had was more functional. It was made of some sort of fabric finished to look and feel like tan mouse fur and resembled a World War I flying helmet in most ways. It had an eye visor, broken off rather quickly, and stamped tin earphones. There was also a little vent on top whose function was never explained. I did love these future artefacts.”

Harrison also read the original Flash Gordon comic strips, begun in 1934 by Alex Raymond with the help of ghostwriter Don Moore. The young Harry could never have imagined that in a couple of decades time he would be writing Flash Gordon’s comic strip adventures.

As well as the comic strips and Amazing Stories, Harrison read other pulps – war titles, air war, railroad stories, Doc Savage, Operator 5, and The Spider.

In Hell’s Cartographers (1975), Harry Harrison wrote: “Loneliness is a word that has deepfelt meaning to me … I did not have a single friend among my classmates, nor did I belong to any gang or pack.” He read a lot, borrowing books from the Queens Borough Public Library. The stories of C.S. Forrester and John Buchan are named as favourite authors of that time. Things settled down when the family moved to Jamaica, Queens and Harry attended PS 117, Briarwood School. There he became friends with Henry Mann and Hubert Pritchard. These three engaged in a number of creative projects together in school and Harrison would again team up with Pritchard after the Second World War. It was at this school, in about 1937, that Harry Harrison began writing, a humorous musical play and poetry being mentioned.

Harrison became involved in science fiction fandom at the age of twelve. Hugo Gernsback, then editor of the magazine Wonder Stories, created the Science Fiction League to encourage and promote science fiction fan activities. The Queen’s chapter of the League was established in November 1937 and expanded to become the Greater New York branch in Spring 1938. In a brief account published in the Noreascon Three Souvenir Book (1989), Harrison wrote: “…Sam Moskowitz, Jimmy Taurasi, myself and about nine other juveniles had founded the Queens Science Fiction League…” He said that this took place ‘the year before’ the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention. Of that first Worldcon, Harrison wrote: “I took my cousin and we sneaked into the subway to save five cents. We must have really been broke because we even sneaked into Caravan Hall to save admission. Which was something like ten cents. I don’t remember the pros or the program – just the fanac. Joy of joys, an entire table filled with throwaways and sample fanzines. I loaded up…”

It was membership of the Science Fiction League that entitled Harry Harrison to join First Fandom, an organisation founded in 1959, with membership originally open to those who were active as fans before the First World Science Fiction Convention in July 1939.

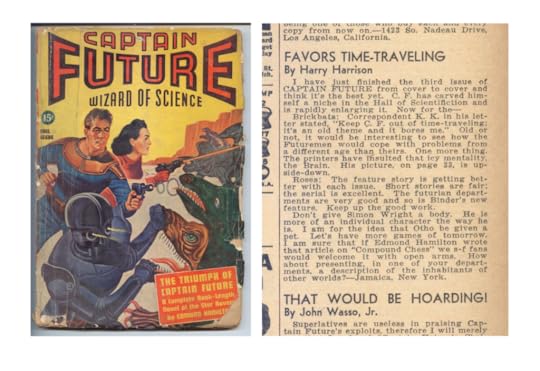

Harry’s letter in the Fall 1940 issue of Captain Future

Harry’s letter in the Fall 1940 issue of Captain FutureIn the Fall of 1940, Harrison had a letter published in Captain Future magazine. And he contributed to at least one fanzine, Gerry de la Ree’s Sun Spots, providing an illustration for the May-June 1941 issue. A note beneath the image states: ‘The original of “Robot” is better than the above, as it was difficult to stencil parts of it’ – a reference to the mimeograph process used to duplicate fanzines in the pre-photocopier era.

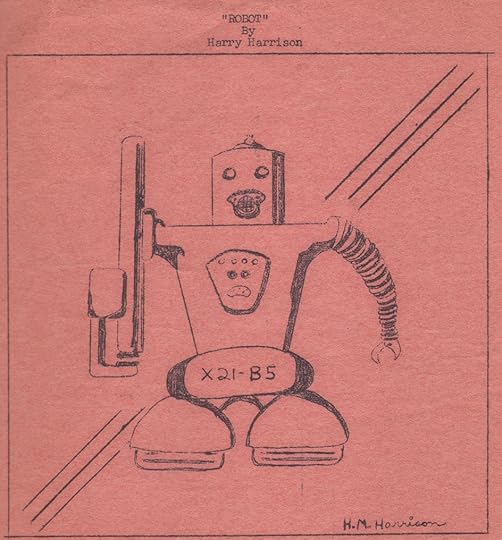

Harry’s drawing from the 1941 Sun Spots fanzine

Harry’s drawing from the 1941 Sun Spots fanzineHarrison and Hubert Pritchard attended Forest Hills High School which opened at the beginning of 1941. The attack on Pearl Harbor took place in December of that year. Harry Harrison was sixteen years old. The Second World War overshadowed Harrison’s high school years – he and his male friends knew they would be drafted on their eighteenth birthdays. They referred to themselves as the ‘no hope’ class. Reflecting on his education years later, Harrison said: “I did pretty rotten at school – or rather, I did well at things I enjoyed: I got the highest marks in class for Science and English, and the lowest marks in Spanish.”

Harry’s yearbook photo from 1943

Harry’s yearbook photo from 1943 Graduating from high school in 1943, Harrison decided that he didn’t want to drown, so he’d prefer to stay out of the navy, and as he didn’t want to get shot, he’d try and avoid the infantry. He would try and persuade the draft board to put him in the air force. After leaving school, he worked as a box boy in Macy’s department store during the day and used the money to attend night school at the Eastern Aircraft Instrument School, in Newark New Jersey. He received a CAA license as an Aircraft Instrument Technician just before he was drafted. When his call up came, he was sent for basic training in the United States Army Air Corps.

NEXT: In the Army Now

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

March 11, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary

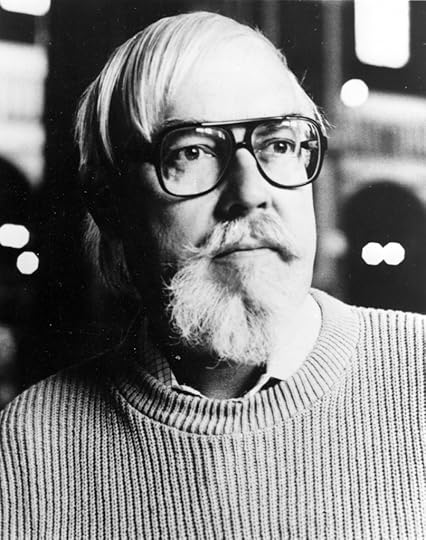

Harry Harrison (c) Jerry Bauer 1984

Harry Harrison (c) Jerry Bauer 1984Tomorrow, 12th March 2025, would have been Harry Harrison’s 100th birthday. We should all raise a glass to celebrate the pleasure his stories gave us when we first encountered them – and the pleasure we get in re-reading them today. Cheers, Harry!

To mark this centenary, I’m going to post a series of articles here, beginning tomorrow. They will be a more or less chronological celebration of his life and work. And over the coming weeks, I’ll include examples of some of his less well-known work – his writing and artwork – and links to previously posted pieces that you may not have found before.

If you have your own memories of Harry that you’d like to share, you can send them using the ‘Contact Us’ link or post them as a comment below – or on any of the articles that follow. Note that all comments are moderated to prevent spamming, so your comment won’t appear until it has been reviewed.

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

July 2, 2021

Science Fiction Author Interviews

I was asked if I would answer some questions about Harry Harrison – here’s a link to the page where the interview appears – it’s under ‘H’. — Paul Tomlinson

Science Fiction Author Interviews

August 15, 2013

Remembering Harry Harrison

Harry Harrison passed away a year ago today.

This morning I received a message from S. Gruzov which said: Сегодня исполняется годовщина смерти Гарри Гаррисона – выдающийся человек. Помянем его.

Google translates that to: Today marks the anniversary of the death of Harry Harrison – an outstanding person. Pray for him.

I’m not a hundred per cent sure Harry would have wanted our prayers, but I think he’d appreciate people remembering him today.

Read from a favourite HH novel or short story, and recommend something of Harry’s to a friend – that way we can keep his memory alive forever.

– Paul

April 22, 2013

Bill, the Galactic Hero Movie is Go!

Alex Cox’s Bill, the Galactic Hero project reached it’s funding target on Kickstarter on Sunday, which means that the movie will actually happen!

I know Alex Cox has wanted to adapt Bill for a looooong time, and was in regular contact with Harry Harrison over the years as he worked on bringing the story to the big screen.

I’m really looking forward to reading the screenplay – Alex has exactly the right sense of humour to handle the adaptation, so I’m sure it will be great.

If you’re not familiar with his work, check out the website alexcox.com which includes free downloads of some of Alex’s screenplays – including Repo Man, Sid and Nancy and his drafts of a Mars Attacks! screenplay – and his Moviedrome guides.*

If you need a further incentive, the site also has a link to Alex’s Bill, the Galactic Hero movie blog.

—-

*In the late 1980s and early 90s Moviedrome was a late night slot on BBC tv which presented an eclectic collection of films, with introductions by Alex Cox. I remember watching on my little black and white portable tv and being entertained – and occasionally spooked – by those movies. There’s a list of the films shown here: http://www.kurtodrome.net/moviedrome.htm and if you check on You Tube you can see some of Alex’s introductions.

Alex Cox presenting BBC TV’s Moviedrome

April 19, 2013

Bill the Galactic Hero Movie – Deadline Sunday

Director Alex Cox reports that the Kickstarter project has reached its $100,000 funding target:

“Things look very good as we have passed our goal. But I would be remiss if I didn’t ask for yet another push! Some supporters may drop out at the eleventh hour; some credit cards will be maxed out and won’t deliver; you know the drill.”

The deadline for the project is 8:00pm EDT on Sunday 21st April — 62 hours to go as I write this. You can still pledge money and, as Alex says, be a part of filmmaking history. You’ll also become a part of HH history, as very few of Harry’s stories have (so far) been adapted into films of any kind.

You can read Alex’s latest update and pledge money on the Kickstarter website.

April 8, 2013

Bill, the Galactic Movie Kickstarter Update

Thirteen days left on the Kickstarter countdown. So far just over $72,000 has been raised towards the budget, so only $28,000 left to go.

It would be great to see a Bill, the Galactic Hero movie, and you can help make it happen by (a) pledging money, and (b) telling everyone you know to pledge money! Please spread the word.

Payments for Kickstarter projects are handled through Amazon Payments – you can use your Amazon .com or .co.uk login to complete your transaction. Your money will only be taken if the project reaches 100% funding by Sunday 21st April 2013.

Great Rewards are on offer to those who help fund the project, check out the details on the Bill, the Galactic Hero project page.

Artwork: Michael Gross

March 22, 2013

Bill, the Galactic Movie

Director Alex Cox’s plans for an adaptation of Bill, the Galactic Hero are moving on apace, and now you can help make the movie happen.

The aim is to raise a $100,000 budget via Kickstarter.com – find out more details and watch Alex’s video about the project here:

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/alexcoxfilms/alex-cox-directs-bill-the-galactic-hero

Pledge cash if you can – the deadline is 21st April 2013. Pledge $10 and you get to download the screenplay as a .pdf if the project goes ahead. Pledge more than $25 and you’ll get to download the movie as a .mov file once it is completed. Check out the Kickstarter page to see what rewards are on offer if you pledge even greater sums…

Alex Cox Directs Bill, the Galactic Hero

January 16, 2013

AbeBooks 50 Essential SF Books

Richard Davies has compiled a top fifty for the AbeBooks website — and of course there’s a Harry Harrison novel on the list. No prizes for guessing which HH novel he includes.

You can see the full list here.

Harry Harrison's Blog

- Harry Harrison's profile

- 1038 followers