Kate Forsyth's Blog, page 50

October 22, 2013

SPOTLIGHT: On Historical Fiction Readers

Historical fiction is hotter than it has ever been, thanks to writers like Ken Follett, Hilary Mantell and Philippa Gregory. Its certainly one of my own favourite genres of fiction, whether written for adults or children.

But who reads historical fiction? The results may surprise you ....

[image error]

Image from Darcy Pattison's webpage

A 2012 reader survey conducted by M.K. (Mary) Tod uncovered insights about those who read historical fiction and those who do not – demographics, story preferences, favourite time periods, reasons for reading or not reading this genre, top authors, the different perspectives of men and women, sources of recommendations and so on.

For example, did you know that …

• Discovering historical fiction early in life makes a difference. Those who began reading historical fiction as children continue to read HF at higher rates than those who began reading HF later in life.

• While men represented 16% of all respondents, they only represented 7% of those reading more than 30 books per year.

• The time period preferred by readers is the 13th to 16th centuries while the least favourite time periods are prehistory and the 2nd to 5th centuries.

• The online world dominates as a source of recommendations for books to read. However, men use online sources for recommendations less frequently than women.

• Inaccuracies and too much historical detail are the two most significant aspects that spoil the enjoyment of historical fiction.

• The top five favourites authors are Sharon Kay Penman, Philippa Gregory, Elizabeth Chadwick, Diana Gabaldon and Bernard Cornwell.

Mary is now running a 2013 survey which will augment these results with a broader focus on reading habits as well as social media’s role in enhancing the reading experience. Survey questions were developed in collaboration with Richard Lee, Founder of the Historical Novel Society.

Whether you read historical fiction or not, please take a few minutes to complete the survey. To add to the robustness of data collected, please pass the survey URL along to men and women of all ages and in any part of the world you can reach!

Here's the link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/JCG7NYP

M.K. Tod writes historical fiction and blogs about all aspects of the genre at A Writer of History. Her debut novel, UNRAVELLED: Two wars. Two affairs. One marriage. is available in paperback and e-book formats from Amazon (US, Canada and elsewhere), Nook, Kobo, Google Play and iTunes. Mary can be contacted on Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads.

But who reads historical fiction? The results may surprise you ....

[image error]

Image from Darcy Pattison's webpage

A 2012 reader survey conducted by M.K. (Mary) Tod uncovered insights about those who read historical fiction and those who do not – demographics, story preferences, favourite time periods, reasons for reading or not reading this genre, top authors, the different perspectives of men and women, sources of recommendations and so on.

For example, did you know that …

• Discovering historical fiction early in life makes a difference. Those who began reading historical fiction as children continue to read HF at higher rates than those who began reading HF later in life.

• While men represented 16% of all respondents, they only represented 7% of those reading more than 30 books per year.

• The time period preferred by readers is the 13th to 16th centuries while the least favourite time periods are prehistory and the 2nd to 5th centuries.

• The online world dominates as a source of recommendations for books to read. However, men use online sources for recommendations less frequently than women.

• Inaccuracies and too much historical detail are the two most significant aspects that spoil the enjoyment of historical fiction.

• The top five favourites authors are Sharon Kay Penman, Philippa Gregory, Elizabeth Chadwick, Diana Gabaldon and Bernard Cornwell.

Mary is now running a 2013 survey which will augment these results with a broader focus on reading habits as well as social media’s role in enhancing the reading experience. Survey questions were developed in collaboration with Richard Lee, Founder of the Historical Novel Society.

Whether you read historical fiction or not, please take a few minutes to complete the survey. To add to the robustness of data collected, please pass the survey URL along to men and women of all ages and in any part of the world you can reach!

Here's the link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/JCG7NYP

M.K. Tod writes historical fiction and blogs about all aspects of the genre at A Writer of History. Her debut novel, UNRAVELLED: Two wars. Two affairs. One marriage. is available in paperback and e-book formats from Amazon (US, Canada and elsewhere), Nook, Kobo, Google Play and iTunes. Mary can be contacted on Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads.

Published on October 22, 2013 15:50

October 17, 2013

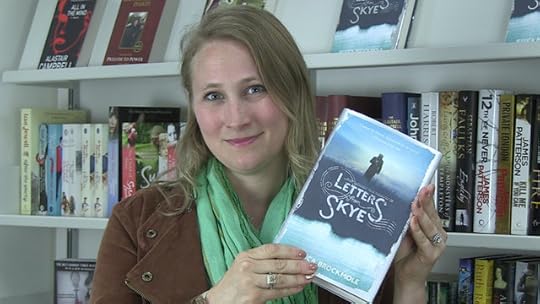

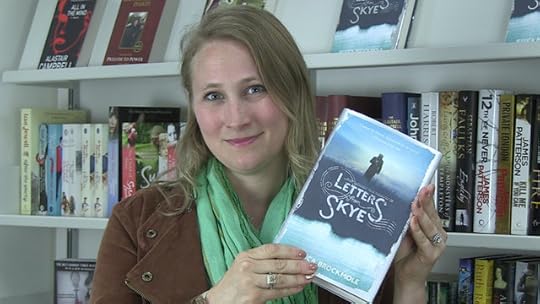

INTERVIEW: Jessica Brockmole, author of Letters from Skye

I really loved Jessica Brockmole's beautiful novel Letters from Skye and so I'm happy to welcome her to the blog, talking about daydreaming, most loved authors, and Scotland.

[image error]

Are you a daydreamer too?

Is there a writer who isn’t? The littlest thing tends to send us off imagining. A headline, a bit of trivia, a family story, a line scrawled on a postcard, that person at the next table slurping green tea, a dream, a nightmare, the way an autumn leaf hangs just so. I don’t know how often my family has encountered me with that familiar vacant stare that they know means I’m lost in my own thoughts and imaginings.

Have you always wanted to be a writer?

When I was young, I used to go to my local library every day in the summer and return with my bike basket full of books. At that pace, I was worried that I’d run out of things to read. I decided I needed to write my own, to always keep a stock of books around. Back then I tended to write stories about time travel and ghosts and pioneers in the American West. I suppose my love of writing historical fiction started even then.

Tell me a little about yourself – where were you born, where do you live, what do you like to do?

I was born in and lived most of my life in the Midwestern United States—Michigan, Illinois, and now Indiana. I did live in Edinburgh, Scotland for four years, not long after I was married, and that’s where I wrote Letters from Skye. The hills and lochs and history of Scotland are so unlike the cornfields and rambling farms that surrounded me growing up! In my free time I enjoy reading, of course, and also cooking. I’m also a passionate canner and can be found pickling all sorts of vegetables come summer.

[image error]

How did you get the first flash of inspiration for this book?

I had tossed around the idea of writing an epistolary novel for a while, but I wasn’t sure when and where to set it. After a holiday on the Isle of Skye, just after my son was born, I had my setting. I was entranced with the island—the landscape, the wind, the smell of the sea, the history and legend woven into the very place names on the map. On the drive home, the story began coming together. A poet—for my heroine could only be a poet on this wind-lashed island—receiving a fan letter. A headstrong man—for who else would write to my poet?—heading off to a war that feels so distant to this isolated corner of Scotland. I started writing that very evening.

How extensively do you plan your novels?

For the most part, I don’t plan them at all. Letters from Skye was written without anything more than “How about a book about a Scottish poet and an American fan? And then the First World War happens. But I’ll write it ALL IN LETTERS!” I like to let the story unfold for me at the same time that it unfolds for the characters. I love surprises. When I have done more planning for a tricky novel, it’s not much. Before beginning, I might write a 1-3 page synopsis that will lay out for me the big plot elements, but I almost always end up writing around that initial synopsis.

I’ve tried writing from detailed outlines and character sheets before, and it just doesn’t work for me. But, then again, I shouldn’t expect it to. When traveling, I’m not one to sightsee along a map. I keep it tucked in my back pocket, in case I get lost, but I’d rather wander and discover the unexpected that way.

Do you ever use dreams as a source of inspiration?

Not as a source of inspiration, but I do sometimes untangle plot snarls in my sleep. I fall asleep frustrated but I wake up and, in the snippets that I remember of my dreams, I can see a potential solution.

Did you make any astonishing serendipitous discoveries while writing this book?

I did! I love those moments. One that comes to mind right away is the hotel. While I was writing the first draft, I needed a swanky London hotel for David to stay at. I’d heard of The Langham and, when I looked it up, saw that it was around when I needed it, in 1915, and that it seemed the perfect place for him to take the untraveled and nervous Elspeth. Done. In a much later draft, I decided to bring Elspeth back to London, decades later. I wanted her to be there for the very beginning of the Blitz. Upon researching, I learned that, of the few luxury hotels in London that suffered damage during the Blitz, the only that was hit during the week I needed was…The Langham. Perfect.

Where do you write, and when?

I write while my children are in school, but then I usually write again in the evening, sometimes quite late. When I first started writing seriously and they were young, I rarely wrote earlier than midnight, though I’m now discovering that I can have an early-morning creative burst!

Though I have a desk, I don’t often write there. I find that I work better when I keep moving, from one location to the next. Not only does changing positions keep me from getting back and shoulder strain, but each fresh location brings with it renewed focus.

What is your favourite part of writing?

I love the warm feeling of serendipity, when a piece of research fits in so neatly to a scene that they seem built for one another. It’s like a wash of magic.

What do you do when you get blocked?

I move to a different writing location. Sometimes a different view and position helps refresh me. If that doesn’t work, a walk or a run usually lets me free my mind and see the problem from a different angle. And if that doesn’t work, then I walk away from it for the day. Although I’m a firm believer in writing every day, whether the muse is present or not, I know when I’m beat. As long as I’ve given it my best shot for the day, I don’t feel guilty about walking away.

How do you keep your well of inspiration full?

I read, a lot. Fiction and non-fiction; new releases and classics; adventures, love stories, mysteries, sagas, fairy tales, books about ordinary people struggling to do ordinary things. Reading gorgeous prose, furtive mythology, or smart essays, I’m inspired to write. And in books of intriguing (yet forgotten) history, I usually find the stories I’m looking for.

Do you have any rituals that help you to write?

I don’t really have any rituals, as I tend to move around and change how and when and where I write to keep my mind fresh. Two constants, though, are my music—an eclectic, energetic mix that always gets me singing and thinking—and my tea. A hot mug of tea always helps me to focus.

Who are ten of your favourite writers?

There are many new authors who I admire and read with relish, and those authors have their own list. My favorites list, however, contains those writers who have been favorites for a while and whose books I happily reread. Authors like Jane Austen, Betty Smith, Louisa May Alcott, and Anne and Charlotte Bronte (never a big Emily fan) are always on the list. Women writing in times when many women didn’t write. Childhood favorites like Laura Ingalls Wilder and L. M. Montgomery are there, as I still have my old copies on the shelf and reread them frequently. They always take me to different places. Tolkien, of course, for his inventiveness. Rowling for her sense of wonder. Bill Bryson for always making me laugh.

[image error]

L.M. Montgomery

What do you consider to be good writing?

Good writing makes me want to use a pencil as bookmark so that I can underline phrases that make my heart skip. And I do.

What is your advice for someone dreaming of being a writer too?

Talk to other writers. Listen to how they do it. Realize that there is no one perfect way to write. Then go away quietly by yourself, shut the door, and do it.

What are you working on now?

My next book, finished but still untitled, is also set during the First World War. Two artists, one Scottish and one French, find each other in wartime Paris and together try to recapture a long-lost summer of innocence.

It sounds wonderful!

[image error]

Are you a daydreamer too?

Is there a writer who isn’t? The littlest thing tends to send us off imagining. A headline, a bit of trivia, a family story, a line scrawled on a postcard, that person at the next table slurping green tea, a dream, a nightmare, the way an autumn leaf hangs just so. I don’t know how often my family has encountered me with that familiar vacant stare that they know means I’m lost in my own thoughts and imaginings.

Have you always wanted to be a writer?

When I was young, I used to go to my local library every day in the summer and return with my bike basket full of books. At that pace, I was worried that I’d run out of things to read. I decided I needed to write my own, to always keep a stock of books around. Back then I tended to write stories about time travel and ghosts and pioneers in the American West. I suppose my love of writing historical fiction started even then.

Tell me a little about yourself – where were you born, where do you live, what do you like to do?

I was born in and lived most of my life in the Midwestern United States—Michigan, Illinois, and now Indiana. I did live in Edinburgh, Scotland for four years, not long after I was married, and that’s where I wrote Letters from Skye. The hills and lochs and history of Scotland are so unlike the cornfields and rambling farms that surrounded me growing up! In my free time I enjoy reading, of course, and also cooking. I’m also a passionate canner and can be found pickling all sorts of vegetables come summer.

[image error]

How did you get the first flash of inspiration for this book?

I had tossed around the idea of writing an epistolary novel for a while, but I wasn’t sure when and where to set it. After a holiday on the Isle of Skye, just after my son was born, I had my setting. I was entranced with the island—the landscape, the wind, the smell of the sea, the history and legend woven into the very place names on the map. On the drive home, the story began coming together. A poet—for my heroine could only be a poet on this wind-lashed island—receiving a fan letter. A headstrong man—for who else would write to my poet?—heading off to a war that feels so distant to this isolated corner of Scotland. I started writing that very evening.

How extensively do you plan your novels?

For the most part, I don’t plan them at all. Letters from Skye was written without anything more than “How about a book about a Scottish poet and an American fan? And then the First World War happens. But I’ll write it ALL IN LETTERS!” I like to let the story unfold for me at the same time that it unfolds for the characters. I love surprises. When I have done more planning for a tricky novel, it’s not much. Before beginning, I might write a 1-3 page synopsis that will lay out for me the big plot elements, but I almost always end up writing around that initial synopsis.

I’ve tried writing from detailed outlines and character sheets before, and it just doesn’t work for me. But, then again, I shouldn’t expect it to. When traveling, I’m not one to sightsee along a map. I keep it tucked in my back pocket, in case I get lost, but I’d rather wander and discover the unexpected that way.

Do you ever use dreams as a source of inspiration?

Not as a source of inspiration, but I do sometimes untangle plot snarls in my sleep. I fall asleep frustrated but I wake up and, in the snippets that I remember of my dreams, I can see a potential solution.

Did you make any astonishing serendipitous discoveries while writing this book?

I did! I love those moments. One that comes to mind right away is the hotel. While I was writing the first draft, I needed a swanky London hotel for David to stay at. I’d heard of The Langham and, when I looked it up, saw that it was around when I needed it, in 1915, and that it seemed the perfect place for him to take the untraveled and nervous Elspeth. Done. In a much later draft, I decided to bring Elspeth back to London, decades later. I wanted her to be there for the very beginning of the Blitz. Upon researching, I learned that, of the few luxury hotels in London that suffered damage during the Blitz, the only that was hit during the week I needed was…The Langham. Perfect.

Where do you write, and when?

I write while my children are in school, but then I usually write again in the evening, sometimes quite late. When I first started writing seriously and they were young, I rarely wrote earlier than midnight, though I’m now discovering that I can have an early-morning creative burst!

Though I have a desk, I don’t often write there. I find that I work better when I keep moving, from one location to the next. Not only does changing positions keep me from getting back and shoulder strain, but each fresh location brings with it renewed focus.

What is your favourite part of writing?

I love the warm feeling of serendipity, when a piece of research fits in so neatly to a scene that they seem built for one another. It’s like a wash of magic.

What do you do when you get blocked?

I move to a different writing location. Sometimes a different view and position helps refresh me. If that doesn’t work, a walk or a run usually lets me free my mind and see the problem from a different angle. And if that doesn’t work, then I walk away from it for the day. Although I’m a firm believer in writing every day, whether the muse is present or not, I know when I’m beat. As long as I’ve given it my best shot for the day, I don’t feel guilty about walking away.

How do you keep your well of inspiration full?

I read, a lot. Fiction and non-fiction; new releases and classics; adventures, love stories, mysteries, sagas, fairy tales, books about ordinary people struggling to do ordinary things. Reading gorgeous prose, furtive mythology, or smart essays, I’m inspired to write. And in books of intriguing (yet forgotten) history, I usually find the stories I’m looking for.

Do you have any rituals that help you to write?

I don’t really have any rituals, as I tend to move around and change how and when and where I write to keep my mind fresh. Two constants, though, are my music—an eclectic, energetic mix that always gets me singing and thinking—and my tea. A hot mug of tea always helps me to focus.

Who are ten of your favourite writers?

There are many new authors who I admire and read with relish, and those authors have their own list. My favorites list, however, contains those writers who have been favorites for a while and whose books I happily reread. Authors like Jane Austen, Betty Smith, Louisa May Alcott, and Anne and Charlotte Bronte (never a big Emily fan) are always on the list. Women writing in times when many women didn’t write. Childhood favorites like Laura Ingalls Wilder and L. M. Montgomery are there, as I still have my old copies on the shelf and reread them frequently. They always take me to different places. Tolkien, of course, for his inventiveness. Rowling for her sense of wonder. Bill Bryson for always making me laugh.

[image error]

L.M. Montgomery

What do you consider to be good writing?

Good writing makes me want to use a pencil as bookmark so that I can underline phrases that make my heart skip. And I do.

What is your advice for someone dreaming of being a writer too?

Talk to other writers. Listen to how they do it. Realize that there is no one perfect way to write. Then go away quietly by yourself, shut the door, and do it.

What are you working on now?

My next book, finished but still untitled, is also set during the First World War. Two artists, one Scottish and one French, find each other in wartime Paris and together try to recapture a long-lost summer of innocence.

It sounds wonderful!

Published on October 17, 2013 06:00

October 15, 2013

BOOK LIST: Best World War I books chosen by Jessica Brockmole

Today I'm very happy to welcome Jessica Brockmole, the author of the enchanting epistolary novel LETTERS FROM SKYE to my blog. She's here to tell us her favourite books set during the First World War (the period of her novel).

Here she is:

I really enjoy reading about the first quarter of the twentieth century, especially the years surrounding the Great War. Although I find the battles fascinating—the whats and whens and wheres—it’s the interpersonal angles that really interests me. The emotions, both from those at the trenches and those waiting back at home. The shock of the experience. The scars that run beneath the skin. The recovery. I’ve read many books that really bring this to life.

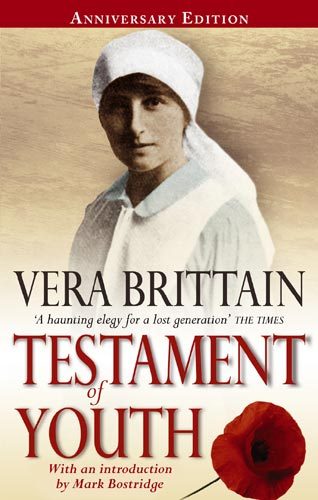

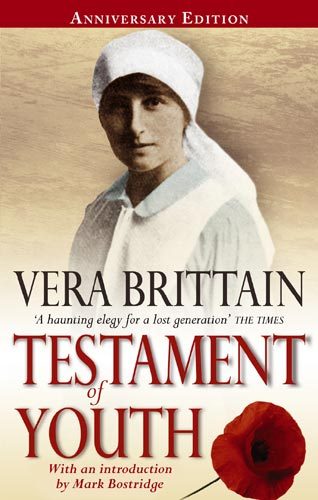

The book that started my fascination with the era is Vera Brittain’s passionate and honest memoir Testament of Youth. It begins in the halcyon days before the war, as Brittain plans to enter university with her brother and friends, takes her through the years where she serves as a nurse in the Voluntary Aid Detachment, then the post-war years, recovering from her own war experiences and from the loss of so many close to her, and channeling that grief into work with the fledgling League of Nations.

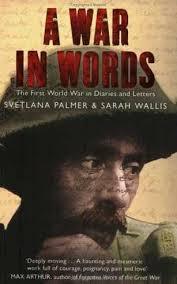

There are other very interesting memoirs—some written during the war, some after—as well as epistolary collections. Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis’s A War in Words is a neat volume, as it contains excerpts from letters and diaries spanning the whole length of the war (and a little beyond), from writers of all ages, nationalities, on both sides of the conflicts. Through their own words, they tell the story of the war.

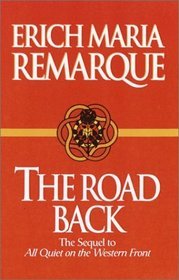

There were some powerful novels written during and after the war, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front being one of the most well-known. Less familiar is its sequel, The Road Back, which begins as the war ends. I like it for its different viewpoint. So many war novels end with the ceasefire—if not a happily-ever-after, an as-happy-as-it-gets ending. But war is not always immediately followed by peace. The Road Back follows the soldiers who survived All Quiet on the Western Front as they return home. Germany is in tatters and they have trouble easing back into both the community and their own families. It’s a sobering reminder that, after war, soldiers can bring back more than scars.

Another very potent novel, written by a veteran and published after the war, is Humphrey Cobb’s Paths of Glory. After a botched attack on a hopeless section of trench, a general is looking to salvage his dignity (but none of the blame) and orders an execution. The order, given in fury, but received down through the ranks in silence, causes the men, from the officers carrying it out to the wrongly sentenced soldiers waiting in prison, to rethink what it means to be brave and what it means to be unlucky in battle. A moving story of courage, culpability, and the futility of war.

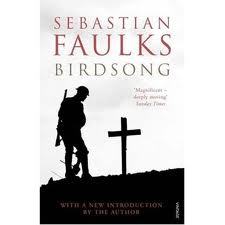

Although the First World War isn’t as popular an era for modern novelists as some other eras, there are some well-regarded novels set then, such as Sebastian Faulks’ Birdsong and the books in Pat Barker’s thoughtful Regeneration Trilogy. Another that I enjoyed is Frances Itani’s Deafening, a novel about a young deaf woman living in small-town Ontario and her husband, a hearing man who goes to the Western Front as a stretcher-bearer. It’s a novel of sound and silence, of searching for the words to explain the inexplicable.

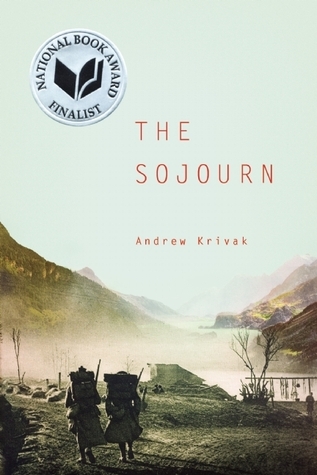

A newer addition to the category of First World War novels, just out a couple of years ago, is Andrew Krivak’s slim book The Sojourn. In it, a young man, raised by his shepherd father in rural Austria-Hungary, is sent as a sharpshooter to the southern front. He survives war, only to face capture and a perilous journey home. This is as much a story of fathers and sons as it is about war, told with beautifully restrained prose.

Others that look at interesting angles of the war: Ben Elton’s The First Casualty, a mystery involving a conscientious objector and his investigation into the murder of a shell-shocked poet; Michael Lowenthal’s marvelously written Charity Girl, a look at both the suffrage movement in the U.S. during as well as the forced incarceration during the war of accused “charity girls,” young women found to have venereal disease; Pam Jenoff’s The Ambassador’s Daughter, where, amid the peace talks leading up to the Treaty of Versailles, the loyalties of a German diplomat’s daughter are tested.

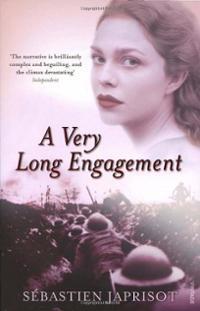

One of my favorite novels about the war, though, is Sébastien Japrisut’s A Very Long Engagement. In the first chapter, we meet five French soldiers, all accused of self-mutilation, who are bound and forced out into No Man’s Land to be executed by enemy fire. Two years later, Mathilde, unable to walk since childhood, receives a letter suggesting that her fiancé, officially “killed in the line of duty,” might have been one of those five soldiers. She’s stubborn and tenacious and so launches her own investigation into the execution, hoping, as she pieces together the story, that her fiancé might have actually survived. Japrisut is unflinching in writing the brutality and sordidness of war, but A Very Long Engagement is as much a love story as it is a war story. Mathilde is a wonderfully engaging narrator, a heroine who never lets anyone tell her “no.” As she searches for her fiancé, sorting through the conflicting stories she gathers, she recounts moments in their friendship and later courtship. I laughed and I cried, sometimes within pages.

There are so many novels about the First World War that are still waiting on my shelf for their turn to be read (although not a Hemingway fan, I know that I should attempt A Farewell to Arms). With the centenary approaching next summer, I hope to see many more appear in the bookstores. It was a complex era, full of social and political change. There are so many corners of its history yet to be explored!

You can read more about Jessica at her website

Here she is:

I really enjoy reading about the first quarter of the twentieth century, especially the years surrounding the Great War. Although I find the battles fascinating—the whats and whens and wheres—it’s the interpersonal angles that really interests me. The emotions, both from those at the trenches and those waiting back at home. The shock of the experience. The scars that run beneath the skin. The recovery. I’ve read many books that really bring this to life.

The book that started my fascination with the era is Vera Brittain’s passionate and honest memoir Testament of Youth. It begins in the halcyon days before the war, as Brittain plans to enter university with her brother and friends, takes her through the years where she serves as a nurse in the Voluntary Aid Detachment, then the post-war years, recovering from her own war experiences and from the loss of so many close to her, and channeling that grief into work with the fledgling League of Nations.

There are other very interesting memoirs—some written during the war, some after—as well as epistolary collections. Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis’s A War in Words is a neat volume, as it contains excerpts from letters and diaries spanning the whole length of the war (and a little beyond), from writers of all ages, nationalities, on both sides of the conflicts. Through their own words, they tell the story of the war.

There were some powerful novels written during and after the war, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front being one of the most well-known. Less familiar is its sequel, The Road Back, which begins as the war ends. I like it for its different viewpoint. So many war novels end with the ceasefire—if not a happily-ever-after, an as-happy-as-it-gets ending. But war is not always immediately followed by peace. The Road Back follows the soldiers who survived All Quiet on the Western Front as they return home. Germany is in tatters and they have trouble easing back into both the community and their own families. It’s a sobering reminder that, after war, soldiers can bring back more than scars.

Another very potent novel, written by a veteran and published after the war, is Humphrey Cobb’s Paths of Glory. After a botched attack on a hopeless section of trench, a general is looking to salvage his dignity (but none of the blame) and orders an execution. The order, given in fury, but received down through the ranks in silence, causes the men, from the officers carrying it out to the wrongly sentenced soldiers waiting in prison, to rethink what it means to be brave and what it means to be unlucky in battle. A moving story of courage, culpability, and the futility of war.

Although the First World War isn’t as popular an era for modern novelists as some other eras, there are some well-regarded novels set then, such as Sebastian Faulks’ Birdsong and the books in Pat Barker’s thoughtful Regeneration Trilogy. Another that I enjoyed is Frances Itani’s Deafening, a novel about a young deaf woman living in small-town Ontario and her husband, a hearing man who goes to the Western Front as a stretcher-bearer. It’s a novel of sound and silence, of searching for the words to explain the inexplicable.

A newer addition to the category of First World War novels, just out a couple of years ago, is Andrew Krivak’s slim book The Sojourn. In it, a young man, raised by his shepherd father in rural Austria-Hungary, is sent as a sharpshooter to the southern front. He survives war, only to face capture and a perilous journey home. This is as much a story of fathers and sons as it is about war, told with beautifully restrained prose.

Others that look at interesting angles of the war: Ben Elton’s The First Casualty, a mystery involving a conscientious objector and his investigation into the murder of a shell-shocked poet; Michael Lowenthal’s marvelously written Charity Girl, a look at both the suffrage movement in the U.S. during as well as the forced incarceration during the war of accused “charity girls,” young women found to have venereal disease; Pam Jenoff’s The Ambassador’s Daughter, where, amid the peace talks leading up to the Treaty of Versailles, the loyalties of a German diplomat’s daughter are tested.

One of my favorite novels about the war, though, is Sébastien Japrisut’s A Very Long Engagement. In the first chapter, we meet five French soldiers, all accused of self-mutilation, who are bound and forced out into No Man’s Land to be executed by enemy fire. Two years later, Mathilde, unable to walk since childhood, receives a letter suggesting that her fiancé, officially “killed in the line of duty,” might have been one of those five soldiers. She’s stubborn and tenacious and so launches her own investigation into the execution, hoping, as she pieces together the story, that her fiancé might have actually survived. Japrisut is unflinching in writing the brutality and sordidness of war, but A Very Long Engagement is as much a love story as it is a war story. Mathilde is a wonderfully engaging narrator, a heroine who never lets anyone tell her “no.” As she searches for her fiancé, sorting through the conflicting stories she gathers, she recounts moments in their friendship and later courtship. I laughed and I cried, sometimes within pages.

There are so many novels about the First World War that are still waiting on my shelf for their turn to be read (although not a Hemingway fan, I know that I should attempt A Farewell to Arms). With the centenary approaching next summer, I hope to see many more appear in the bookstores. It was a complex era, full of social and political change. There are so many corners of its history yet to be explored!

You can read more about Jessica at her website

Published on October 15, 2013 06:00

October 13, 2013

BOOK REVIEW: Letters from Skye by Jessica Brockmole

[image error]

Title: Letters from Skye

Author: Jessica Brockmole

Publisher: Ballantine Books

Age Group & Genre: Historical Fiction for Adults

Reviewer: Kate Forsyth

The Blurb:

A sweeping story told in letters, spanning two continents and two world wars, Jessica Brockmole’s atmospheric debut novel captures the indelible ways that people fall in love, and celebrates the power of the written word to stir the heart.

March 1912: Twenty-four-year-old Elspeth Dunn, a published poet, has never seen the world beyond her home on Scotland’s remote Isle of Skye. So she is astonished when her first fan letter arrives, from a college student, David Graham, in far-away America. As the two strike up a correspondence—sharing their favorite books, wildest hopes, and deepest secrets—their exchanges blossom into friendship, and eventually into love. But as World War I engulfs Europe and David volunteers as an ambulance driver on the Western front, Elspeth can only wait for him on Skye, hoping he’ll survive.

June 1940: At the start of World War II, Elspeth’s daughter, Margaret, has fallen for a pilot in the Royal Air Force. Her mother warns her against seeking love in wartime, an admonition Margaret doesn’t understand. Then, after a bomb rocks Elspeth’s house, and letters that were hidden in a wall come raining down, Elspeth disappears. Only a single letter remains as a clue to Elspeth’s whereabouts. As Margaret sets out to discover where her mother has gone, she must also face the truth of what happened to her family long ago.(less)

What I Thought:

One of my favourite books is The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Anne Schaffer. It is an epistolary narrative which simply means ‘told in the form of a letter or letters’. Extremely popular in the 18th century, this narrative form fell out of favour in the 19th century and has not been used much since. It seems that Mary Anne Schaffer may have revived the form, however, for this new novel by debut author Jessica Brockmole is told entirely in letters.

Letters from Skye moves between two historical periods: the First World War and the Second World War. The primary narrative is that of the relationship of a young Scottish poet who lives on Skye in and an American university student who writes in March 1912 to tell her how much he admires her poetry.

Slowly friendship blossoms into love, but many obstacles stand in their way, including the fact that Elspeth is already married and their world is on the brink of a cataclysmic war. The device of driving a narrative through an exchange of letters can be hard to pull off (one reason why it fell out of favour), but Jessica Brockmole has created an engaging and very readable suspenseful romance in Letters from Skye. I really loved it!

Jessica's website

PLEASE LEAVE A COMMENT – I LOVE TO KNOW WHAT YOU THINK

Published on October 13, 2013 06:00

October 1, 2013

BOOK LIST - Books Read in August 2013

August is Book Week in Australia, and that means lots of authors, including myself, have been on the road, talking about our books at schools, libraries and literary festivals. With so much travelling and talking, there’s not much time for reading and so this month I managed only eight books – however, I discovered a couple of wonderful new authors and read the new work of a few old favourites and so it was a happy reading month for me.

[image error]

1. The Tudor Conspiracy – C.W. Gortner

The Tudor period was a time of turmoil, danger, and intrigue … and this means spies. Brendan Prescott works in the shadows on behalf of a young Princess Elizabeth, risking his life to save her from a dark conspiracy that could make her queen … or send her to her death. Not knowing who to trust, surrounded by peril on all sides, Brendan must race against time to retrieve treasonous letters before Queen Mary’s suspicions of her half-sister harden into murderous intent.

The Tudor Conspiracy is a fast-paced, action-packed historical thriller, filled with suspense and switchback reversals, that also manages to bring the corrupt and claustrophobic atmosphere of the Tudor court thrillingly to life. It follows on from C.W. Gortner’s earlier novel, The Tudor Secret, but can be read on its own (though I really recommend reading Book 1 first – it was great too).

[image error]

2. Pureheart – Cassandra Golds

Cassandra Golds is one of the most extraordinary writers in the world. Her work is very hard to define, because there is no-one else writing quite like she does. Her books are beautiful, haunting, strange, and heart-rending. They are old-fashioned in the very best sense of the word, in that they seem both timeless and out-of-time. They are fables, or fairy tales, filled with truth and wisdom and a perilous kind of beauty. They remind me of writers I adored as a child – George Macdonald Fraser, Nicholas Stuart Gray, Elizabeth Goudge, or Eleanor Farjeon at her most serious and poetic.

I have read and loved all of Cassandra’s work but Pureheart took my breath away. Literally. It was like being punched in the solar plexus. I could not breathe for the lead weight of emotion on my heart. I haven’t read a book that packs such an emotional wallop since Patrick Ness’s A Monster Calls. This is a story about a bullied and emotionally abused child and those scenes are almost unbearable to read. It is much more than that, however.

Pureheart is the darkest of all fairy tales, it is the oldest of all quest tales, it is an eerie and enchanting story about the power of love and forgiveness. It is, quite simply, extraordinary.

[image error]

3. Park Lane – Frances Osborne

Park Lane is the first novel by Frances Osborne, but she has written two earlier non-fiction books which I really enjoyed. The first, called Lilla’s Feast, told the story of her paternal great-grandmother, Lilla Eckford, who wrote a cookbook while being held prisoner in a Japanese internment camp during World war II. The second, called The Bolter, was written about Frances Osborne’s maternal great-grandmother, the notorious Lady Idina Sackville. Married five times, with many other lovers, Idina was part of the scandalous Happy Valley set in Kenya which led to adultery, drug addiction, and murder. Both are absolutely riveting reads, and so I had high hopes of Park Lane, particularly after I read a review in The Guardian which said ‘Frances Osborne will be in the vanguard of what is surely an emergent genre: books that appeal to Downton Abbey fans.’ Well, that’s me! I should have been a very happy reader.

I have to admit, however, that the book did not live up to my expectations. This was partly because it is written entirely in present tense, a literary tic which I hate, and partly because of the style, which felt heavy and awkward.

The sections told from the point of view of the aristocratic Beatrice are the most readable, perhaps because this is a world that Frances Osborne knows well (she is the daughter of the Conservative minister David Howell, Baron Howell of Guildford, and wife of George Osborne, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer, which means she lives next door to the Prime Minister on Downing Street in London.) However, the sections told from the point of view of her servant, Grace, are less successful, and her voice did not ring true for me. Also, I was just getting interested in her story when she disappears from the page, popping up again at the end.

The sections I enjoyed the most were those detailing the suffragettes’ struggle for the vote. These scenes were full of action and drama, and draw upon Frances Osborne’s own family history, with her great-great-grandmother having made many sacrifices for the women’s cause. I’d have liked to have known much more about their struggle and the hardships they faced (maybe I’ll need to write my own suffragette novel one day).

[image error]

4. The Devil’s Cave – Martin Walker

I really love this series of murder mysteries set in a small French village in the Dordogne. A lot of the pleasure of these books does not come from the solving of the actual crime – which is often easily guessed – but from the descriptions of the town, the countryside, and the food and wine (I always want to cook the recipes, many of which can be found on the author’s website). These books also really make me want to go back to France!

The hero of this series is the small-town policeman Benoît Courrèges, called Bruno by everyone. He lives in an old shepherd’s cottage, with a beagle hound, ducks, chickens, a goat and a vegetable garden. He’s far more likely to offer some homespun wisdom than arrest anyone, a trait I appreciate. There’s always a touch of romance, and a cast of eccentric minor characters who add warmth and humour.

The first few books were lazy and charming; the tension is slowly growing in later books which I think is a good thing as the series may have grown just a little too comfortable otherwise. In this instalment – no 5 in the series – there is a dead naked woman in a boat, satanic rituals and chase scenes in an underground cave, a Resistance heroine to be rescued, a local girl led astray, and an omelette made with truffle-infused eggs and dandelion buds. A big sigh of happiness from me.

[image error]

5. Let It Be Me – Kate Noble

I bought this book solely on the cover – a Regency romance set in Venice? Sounds right up my alley … I mean, canal …

I have never read a book by Kate Noble before, but I certainly will again. Let It Be Me is clearly part of a series, as is often the case with historical romances, but I had no trouble working out who everyone is.

The book was set in 1824, and our heroine is the red-haired Bridget Forrester. Although she is quite pretty, none of the men at the ball ask her to dance as she has a reputation for being a shrew. It seems she has been over-shadowed by her sister, the Beauty of the family.

So Sarah is over-joyed when she receives an invitation to be taught by the Italian composer, Vincenzo Carpenini. After a series of troubles and complications, Bridget ends up going to Venice and before she know sit, finds herself part of a wager to prove that women can play the piano just as well as men. All sorts of romantic entanglements occur, with a wonderful musical leitmotif running through – a very enjoyable romantic read.

[image error]

6. The Sultan’s Eyes – Kelly Gardiner

I was on a panel with Kelly Gardiner at the Melbourne Writers Festival, and so read The Sultan’s Eyes in preparation for our talk together. Historical fiction is my favourite genre, and I particularly love books set in the mid-17th century, a time of such bloody turmoil and change. I set my six-book series of children’s historical adventure novels ‘The Chain of Charms’ during this time and so I know the period well. I absolutely loved reading The Sultan’s Eyes, which is set in Venice and Constantinople in 1648, and am now eager to read the book that came before, Act of Faith.

The heroine of the story is Isabella Hawkins, the orphaned daughter of an Oxford philosopher, and educated by him in the classics as if she had been a boy. She has taken refuge in Venice with some friends following the death of her father, after what seem like some hair-raising adventures in Book 1. An old enemy, the Inquisitor Fra Clement, arrives in Venice, however, and afraid for their lives, Isabella and her friends free to the exotic capital of the East, Constantinople, which is ruled by a boy Sultan. His mother and his grandmother are engaged in covert and murderous intrigues to control him, and it is not long before Isabella and the others are caught up in the conspiracies. I loved seeing the world of the Byzantine Empire brought so vividly to life, and loved the character of Isabella - passionate, outspoken, intelligent and yet also vulnerable.

[image error]

7. The Wishbird – Gabrielle Wang

I love Gabrielle Wang’s work and I love listening to her speak, so I was very happy to be sharing a stage with her at the Melbourne Writers Festival. Her new novel The Wishbird is a magical adventure for young readers, and has the added bonus of illustrations by Gabrielle as well, including the gorgeous cover.

Boy is an orphaned street urchin in the grim City of Soulless who makes a living as a pickpocket. One day he has a chance encounter with Oriole, a girl with a ‘singing tongue’ who was raised by the Wishbird in the Forest of the Birds. The Wishbird is dying, and Oriole has come to the city to try and find a way to save him. She finds herself imprisoned for her musical voice, however, and Boy must find a way to help her. What follows is a simple but beautiful fable about courage, beauty, love and trust that reminded me of old Chinese fairy tales.

[image error]

8. Elijah’s Mermaid – Essie Fox

Elijah’s Mermaid is best described as a dark Gothic Victorian melodrama about the lives of two sets of orphans. One is the beautiful and wistful Pearl, found as a baby after her mother drowned in the Thames, and raised in a brothel with the rather whimsical name of The House of Mermaids. The other two are the twins Elijah and Lily, also abandoned, but lucky enough to be adopted by their grandfather, an author named Augustus Lamb.

The voices of Pearl and Lily alternate. At first Pearl’s voice is full of street slang and lewd words, but as she grows up many of these are discarded. For the first third of the book, the only points of contact are the children’s fascination with mermaids and water-babies (Pearl has webbed feet), but then they meet by chance at a freak show in which a fake mermaid is exhibited. After that, their lives slowly entwine.

Although the pace is leisurely, the story itself is intense and full of drama and mystery. The Victorian atmosphere is genuinely creepy. I could feel the chill swirl of the fog, and hear the clatter of the horses’ hooves on the cobblestones, and see Lily struggling to run in her corset and bustle. The story’s action takes place in freak shows, brothels, midnight alleys, underground grottos, and a madhouse, and so the dark underbelly of Victorian society is well and truly turned to the light. Yet this is a novel about love and redemption, as well as obsession and murder, and the love between the twins, and between Elijah and Pearl, is beautifully done.

This monthly round-up of my reading was first posted for BOOKTOPIA and if you want to buy any of these books, they have all the links you need.

Published on October 01, 2013 20:21

September 3, 2013

WRITING: How to Avoid a Saggy Middle

Saggy Middle Syndrome.

We all know what it is. A novel that starts brilliantly well – vivid, intriguing and compelling – yet somehow, around the middle of the book, you find yourself beginning to yawn. You check the pages to see how many are left before the end of the chapter. You might even put the book down and pick something else up instead.

It happens in series of books too. The first couple of books are great – you rushed out to buy the next one as soon as you finished the first – but then, around Book 3 or 4, you begin to lose interest. The book seems predictable, stale, and far too long.

Yep, that’s Saggy Middle Syndrome.

I always tell my writing students:

The first scene is the most important scene in the book.

The last scene is the second most-important scene in the book.

The middle scene is the third most important.

Yet many, many writers just think of it as just another scene.

I don’t. I think about it very deeply and very carefully.

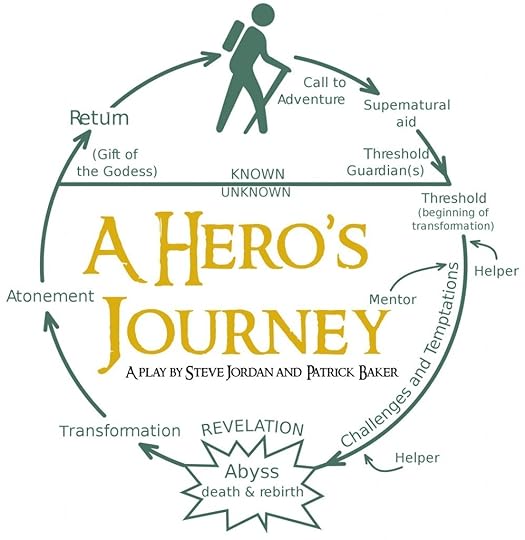

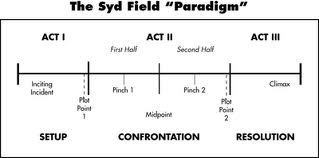

In Campbellian story theory, the midpoint is The Belly of the Whale.

It is the darkest point of the story, a time in which it may seem that all is lost and the hero cannot go on. It is a time of psychological darkness, or emotional despair, a time in which the hero surrenders all hope.

Syd Field, the grandfather of screenwriting theory, calls it the Midpoint Reversal: ‘An important scene in the middle of the script, often a reversal of fortune or revelation that changes the direction of the story.’

I like this term as it expresses something of what I believe about this most significant of turning points, the second major crisis in your story.

The midpoint must be a pivotal moment in the story, a kind of psychic shift, a hinge that joins together the two halves of the book. I believe there should be some kind of epiphany, a moment of clear-sightedness in which the hero realises the cost of the path to which they have committed themselves. The hero must either find the courage to go on in their chosen path, or choose another way. The reversal does not need to be a complete face-about, but it does need to show a change in the hero’s outlook.

I like my midpoint reversal to be set somewhere dark, somewhere claustrophobic, somewhere dangerous, but this does not always need to be the case. It can be high noon in a desert, or dawn in a baby’s bedroom. The Midpoint Reversal is always about the character’s inner journey. Often the Midpoint Reversal is a symbolic gateway to another place, a new direction, a new landscape – either literal or metaphorical – or a new understanding of the truth. It can also foreshadow the final showdown – often the midpoint is where the hero tries to achieve whatever it is he or she wants, but fails. However, in that failure may come the realisation of what needs to be done in order to triumph, even though the cost may be high.

For the reader, it should signal an acceleration of the plot, a raising of the stakes, a deeper understanding of the hero’s dilemma. It should throw the story into another gear, making the reader fear for our hero more intensely than ever before.

I’m writing this writing post today, because I am writing the middle scene of the middle book in a five-book series (ie I’m halfway through writing Book 3). The Midpoint Reversal of this book is also the mid-point of the whole combined narrative arc and so it has to carry a double burden. It needs to be a significant pivotal moment, a crisis of the soul, for the whole five-book series as well as for this particular novel.

So excuse me while I go and exercise all my wit, ingenuity and creative craft to make sure that my novel has strong core muscles and a six-pack to be proud of.

Published on September 03, 2013 18:12

September 1, 2013

INTERVIEW - Helen Lowe, author of The Gathering of the Lost

I'm very pleased to be chatting to Helen Lowe, the award-winning New Zealand author of The Gathering of the Lost, and the only woman to be shortlisted for the prestigious David Gemmell Legend Award for 2013.

Helen, welcome to the blog. Tell me a little about your journey to being a writer.

Pretty much ever since stories were first read to me I wanted to be a storyteller, and as I recall I was around eight years old when I first started writing and putting on plays with my siblings and friends. As a teen I was writing poetry, short fiction and novels, and had a number of short stories succeed in open competition before university studies and career intervened for a time.

But then I started waking up at night and thinking: “Why aren’t I writing? I should be writing!” So one day I put all my ideas for stories and half-finished manuscripts out on the floor and told myself: “Just pick one and finish it!”

That story was The Heir Of Night - the first novel in The Wall Of Night series - and although a subsequent Junior fiction novel, Thornspell, was my first book published—and I’ve also had a considerable body of poetry and some short fiction published as well—from that moment I have never looked back. And of course last year, The Heir Of Night won the David Gemmell Morningstar Award for Best Fantasy Newcomer, which was quite a moment for that manuscript picked up off the floor a few years back.

What is your novel 'The Gathering Of The Lost' all about?

The Gathering Of The Lost is the second novel in THE WALL OF NIGHT series and picks up the story five years after The Heir Of Night leaves off.

Just to quickly outline the basic premise of THE WALL OF NIGHT series (which is a quartet), it’s classically-conceived epic or high fantasy. The Wall of Night itself exists on the world of Haarth and is an environment of shadow and conflict that the Derai Alliance garrisons against an aeons-old enemy. So far, so usual – but part of the reason I chose this classic theme is because I wanted to explore how the Derai, who believe themselves to be champions of good, are in fact divided by prejudice, suspicion and fear. I also wanted to address the notion that it is what people actually do, rather than what they believe about themselves, that really makes for “good guys” and “bad guys” – as well as how circumstances may have a bearing on that equation. Another less usual element is that the Derai are alien to Haarth: they have imposed their war and their enemy on the indigenous inhabitants, which adds a cultural dimension to the conflict.

The two main characters are Malian, the Heir to the warrior house of Night, and Kalan, a friend who was thrust into a confined, temple life because of his magic powers. At the end of the first book they had fled the Wall of Night and disappeared into the wild back country of Haarth. For five years they have been believed dead, but now, in The Gathering Of The Lost, Malian’s enemies are on the hunt and the adventure shifts from murder amidst the alleys and islands of the River city of Ij, to insurgency along wild marches patrolled by the Emerian knights.

The story is one of magic and adventure, roof top pursuits and forced marches by night, tourneys and springtime love; it’s also a story of thousand-year-old riddles, hidden identities, and a quest for weapons of power.

At another level, the story is about Malian and Kalan’s friendship, and whether their interests, after five years’ separation, remain as aligned as they were in The Heir Of Night. Other tensions revolve around whom, in a world of conflicting ambitions, either of them can truly trust. In Malian’s case, given her great power, the question may even be whether she can trust herself—as well as just how much she is prepared to sacrifice, including Kalan, to fulfill her duty to the Derai and save Haarth.

It’s a complex work—so as you can imagine, I’m thrilled that it is has just made it through to the shortlist for the David Gemmell Legend Award for Best Fantasy (published in 2012.)

How did you first get the idea for it?

Ursula Le Guin (in her wonderful book on writing, Steering The Craft) said “The world’s full of stories, you just reach out.” But I don’t think there is ever just the one idea.

So in terms of THE WALL OF NIGHT series, I had the vision of a dark, wind-blasted world from a very early age, a vision that was undoubtedly influenced by the Norse myths. I was living in Singapore at the time, and I definitely think the swiftness with which night fell there, almost on the equator, helped the prevailing idea of “darkness” to take hold.

But the spark that ignited The Heir Of Night story in particular was an image of Malian scaling the wall of an ancient ruined keep. That first imagining came with its instant backstory of what her life was, and why . . . So although the genesis of the idea lay with the world, it was the evolution of Malian’s character, with a host of others quickly following, that sparked the actual book.

The Gathering Of The Lost opens out the world and the story from the first book, and I had the opening scene of the first chapter in my head for quite some years before I actually wrote it. The scene is spring, and rain, and the first faint greening of willows as two of the characters, the symbiotic Heralds of the Guild, ride from one city of the River to another (Ij): “because the whole world rides to Ij in the springtime.” But in terms of where that idea came from—as Ms Le Guin also suggests, it was in the air and I just reached out.

What was the greatest challenge in writing The Gathering Of The Lost?

I live in Christchurch, New Zealand, and I completed The Gathering Of The Lost during the period of major earthquakes that shook the city between September 2010 and December 2011, with over 10,000 discernible recorded earthquakes, and major destruction and loss of 185 lives in the February 2011 ’quake. The damage included major loss of infrastructure, including no domestic sewer for 10 months, a boarded-over living room wall, and incidences of ‘liquefaction’ after each major quake.

(Liquefaction is when the ground turns to slurry that is forced to the surface and in this case flooded large areas of the city leaving thick black silt in its wake.) So finishing the book under those conditions was a “major.” It is also one of the reasons why being shortlisted for the Legend Award means a great deal, because it is this book, The Gathering Of The Lost, that is my personal testament to having endured and lived through those times.

What does it mean to you to be the only woman writer shortlisted for such a prestigious award? Why do you think women still need to struggle so hard for recognition and acclaim?

Kate, I am absolutely thrilled that The Gathering Of The Lost has made it to the shortlist for the Legend Award, but I am also disappointed, given there were so many women authors on the longlist, that I am the only one listed in either of the two book award finals, the Legend or the Morningstar. But I am very glad that there is at least one woman there—and I hope that this year’s result is a “blip”, because I believe that women read and appreciate the epic genre, women are writing great epic fantasy, and if the correspondence I am getting is an indicator, are being taken seriously by readers of both genders.

Another reason I am really pleased that The Gathering Of The Lost is on the shortlist is because the main character is female, and although that is not unprecedented, it is still relatively rare in epic fantasy.

In terms of the second question, I am not really sure that I fully know the answer to “why”, or whether women authors struggle to the same extent across all genres. I do think, though, that what happens in literature will inevitably reflect wider cultural and social trends, and that although there has been a great deal of positive change in society over the past half century and more, there is still a long way to go in terms of the status of women. So it is probably not surprising that the same forces also play out in the world of literature and it is therefore important to keep reevaluating and pushing the boundaries.

But I also think that as an author, all I can do is write the very best books I am capable of and hope that readers will judge the story on its merits, not on the gender of the author’s name. The reason I write epic fantasy is because I love epic fantasy—and I hope that comes through in the storytelling.

What are your plans for the future?

Right now, I am finishing Daughter of Blood, (THE WALL OF NIGHT Book Three) and then still have WALL 4 to write. After that, a great deal will depend on the success of the series with readers in terms of whether anyone out there wants more “Helen Lowe” – but I know that I have plenty more ideas for characters and worlds, so fingers crossed that readers want to see them written!

In terms of what I write, the one thing I am sure of is that I don’t want to write to a formula, and I do want to continually grow and develop my storytelling, so there is scope for the “new” in every sense of the word.

In terms of the immediate future and the David Gemmell Legend Award, if readers want to read my Morningstar essay on influences and “why Fantasy” from last year, it’s here. And if they would like to vote, the link is here (but don’t forget to click on “vote” to complete the process.)

Thank you very much for having me on your site, Kate—it’s a great pleasure and an honour to be here.

Helen, welcome to the blog. Tell me a little about your journey to being a writer.

Pretty much ever since stories were first read to me I wanted to be a storyteller, and as I recall I was around eight years old when I first started writing and putting on plays with my siblings and friends. As a teen I was writing poetry, short fiction and novels, and had a number of short stories succeed in open competition before university studies and career intervened for a time.

But then I started waking up at night and thinking: “Why aren’t I writing? I should be writing!” So one day I put all my ideas for stories and half-finished manuscripts out on the floor and told myself: “Just pick one and finish it!”

That story was The Heir Of Night - the first novel in The Wall Of Night series - and although a subsequent Junior fiction novel, Thornspell, was my first book published—and I’ve also had a considerable body of poetry and some short fiction published as well—from that moment I have never looked back. And of course last year, The Heir Of Night won the David Gemmell Morningstar Award for Best Fantasy Newcomer, which was quite a moment for that manuscript picked up off the floor a few years back.

What is your novel 'The Gathering Of The Lost' all about?

The Gathering Of The Lost is the second novel in THE WALL OF NIGHT series and picks up the story five years after The Heir Of Night leaves off.

Just to quickly outline the basic premise of THE WALL OF NIGHT series (which is a quartet), it’s classically-conceived epic or high fantasy. The Wall of Night itself exists on the world of Haarth and is an environment of shadow and conflict that the Derai Alliance garrisons against an aeons-old enemy. So far, so usual – but part of the reason I chose this classic theme is because I wanted to explore how the Derai, who believe themselves to be champions of good, are in fact divided by prejudice, suspicion and fear. I also wanted to address the notion that it is what people actually do, rather than what they believe about themselves, that really makes for “good guys” and “bad guys” – as well as how circumstances may have a bearing on that equation. Another less usual element is that the Derai are alien to Haarth: they have imposed their war and their enemy on the indigenous inhabitants, which adds a cultural dimension to the conflict.

The two main characters are Malian, the Heir to the warrior house of Night, and Kalan, a friend who was thrust into a confined, temple life because of his magic powers. At the end of the first book they had fled the Wall of Night and disappeared into the wild back country of Haarth. For five years they have been believed dead, but now, in The Gathering Of The Lost, Malian’s enemies are on the hunt and the adventure shifts from murder amidst the alleys and islands of the River city of Ij, to insurgency along wild marches patrolled by the Emerian knights.

The story is one of magic and adventure, roof top pursuits and forced marches by night, tourneys and springtime love; it’s also a story of thousand-year-old riddles, hidden identities, and a quest for weapons of power.

At another level, the story is about Malian and Kalan’s friendship, and whether their interests, after five years’ separation, remain as aligned as they were in The Heir Of Night. Other tensions revolve around whom, in a world of conflicting ambitions, either of them can truly trust. In Malian’s case, given her great power, the question may even be whether she can trust herself—as well as just how much she is prepared to sacrifice, including Kalan, to fulfill her duty to the Derai and save Haarth.

It’s a complex work—so as you can imagine, I’m thrilled that it is has just made it through to the shortlist for the David Gemmell Legend Award for Best Fantasy (published in 2012.)

How did you first get the idea for it?

Ursula Le Guin (in her wonderful book on writing, Steering The Craft) said “The world’s full of stories, you just reach out.” But I don’t think there is ever just the one idea.

So in terms of THE WALL OF NIGHT series, I had the vision of a dark, wind-blasted world from a very early age, a vision that was undoubtedly influenced by the Norse myths. I was living in Singapore at the time, and I definitely think the swiftness with which night fell there, almost on the equator, helped the prevailing idea of “darkness” to take hold.

But the spark that ignited The Heir Of Night story in particular was an image of Malian scaling the wall of an ancient ruined keep. That first imagining came with its instant backstory of what her life was, and why . . . So although the genesis of the idea lay with the world, it was the evolution of Malian’s character, with a host of others quickly following, that sparked the actual book.

The Gathering Of The Lost opens out the world and the story from the first book, and I had the opening scene of the first chapter in my head for quite some years before I actually wrote it. The scene is spring, and rain, and the first faint greening of willows as two of the characters, the symbiotic Heralds of the Guild, ride from one city of the River to another (Ij): “because the whole world rides to Ij in the springtime.” But in terms of where that idea came from—as Ms Le Guin also suggests, it was in the air and I just reached out.

What was the greatest challenge in writing The Gathering Of The Lost?

I live in Christchurch, New Zealand, and I completed The Gathering Of The Lost during the period of major earthquakes that shook the city between September 2010 and December 2011, with over 10,000 discernible recorded earthquakes, and major destruction and loss of 185 lives in the February 2011 ’quake. The damage included major loss of infrastructure, including no domestic sewer for 10 months, a boarded-over living room wall, and incidences of ‘liquefaction’ after each major quake.

(Liquefaction is when the ground turns to slurry that is forced to the surface and in this case flooded large areas of the city leaving thick black silt in its wake.) So finishing the book under those conditions was a “major.” It is also one of the reasons why being shortlisted for the Legend Award means a great deal, because it is this book, The Gathering Of The Lost, that is my personal testament to having endured and lived through those times.

What does it mean to you to be the only woman writer shortlisted for such a prestigious award? Why do you think women still need to struggle so hard for recognition and acclaim?

Kate, I am absolutely thrilled that The Gathering Of The Lost has made it to the shortlist for the Legend Award, but I am also disappointed, given there were so many women authors on the longlist, that I am the only one listed in either of the two book award finals, the Legend or the Morningstar. But I am very glad that there is at least one woman there—and I hope that this year’s result is a “blip”, because I believe that women read and appreciate the epic genre, women are writing great epic fantasy, and if the correspondence I am getting is an indicator, are being taken seriously by readers of both genders.

Another reason I am really pleased that The Gathering Of The Lost is on the shortlist is because the main character is female, and although that is not unprecedented, it is still relatively rare in epic fantasy.

In terms of the second question, I am not really sure that I fully know the answer to “why”, or whether women authors struggle to the same extent across all genres. I do think, though, that what happens in literature will inevitably reflect wider cultural and social trends, and that although there has been a great deal of positive change in society over the past half century and more, there is still a long way to go in terms of the status of women. So it is probably not surprising that the same forces also play out in the world of literature and it is therefore important to keep reevaluating and pushing the boundaries.

But I also think that as an author, all I can do is write the very best books I am capable of and hope that readers will judge the story on its merits, not on the gender of the author’s name. The reason I write epic fantasy is because I love epic fantasy—and I hope that comes through in the storytelling.

What are your plans for the future?

Right now, I am finishing Daughter of Blood, (THE WALL OF NIGHT Book Three) and then still have WALL 4 to write. After that, a great deal will depend on the success of the series with readers in terms of whether anyone out there wants more “Helen Lowe” – but I know that I have plenty more ideas for characters and worlds, so fingers crossed that readers want to see them written!

In terms of what I write, the one thing I am sure of is that I don’t want to write to a formula, and I do want to continually grow and develop my storytelling, so there is scope for the “new” in every sense of the word.

In terms of the immediate future and the David Gemmell Legend Award, if readers want to read my Morningstar essay on influences and “why Fantasy” from last year, it’s here. And if they would like to vote, the link is here (but don’t forget to click on “vote” to complete the process.)

Thank you very much for having me on your site, Kate—it’s a great pleasure and an honour to be here.

Published on September 01, 2013 15:10

August 29, 2013

INTERVIEW: Cassandra Golds, author of PUREHEART

Australia has some of the most extraordinary children's writers working in the world today and one of them is Cassandra Golds, whose books have all the deceptive simplicity of a fairy tale. I am very happy to welcome her to the blog today, to talk about her new book Pureheart which left me in tears.

Here she is:

[image error]

Are you a daydreamer too?

Yes! When I was about 15 I remember thinking to myself, I MUST try to do something USEFUL with all these DAYDREAMS! I guess I felt they must somehow be my vocation. That was when I started pursuing publication in earnest.

Have you always wanted to be a writer?

Yes, for just about as long as I can remember. I wrote my first story almost as soon as I could write.

Tell me a little about yourself – where were you born, where do you live, what do you like to do?

I was born in Sydney — Paddington Royal Women’s Hospital, to be precise — and my first home was in Waterloo, a very old inner city suburb. I grew up in Katoomba in the Blue Mountains, and Penrith in the Western suburbs. Then for many years I lived in Manly, near beautiful Manly Beach. Then, just two years ago, I moved to Melbourne for love! I like to read and write and meditate and drink soothing cups of interesting tea. And I like to talk. And listen to other people talk. And I love to laugh!

How did you get the first flash of inspiration for this book?

A picture came into my head of a girl or young woman gazing out from an upstairs window in an old building at night and seeing a boy waiting outside next to the streetlight, looking up at her. I knew she remembered this boy from some time in her past, and that he was the most important person in the world to her, but I also knew that she had never expected to see him again. The story grew from there.

[image error]

How extensively do you plan your novels?

When I first began to write seriously as a teenager, I used to spend a lot of time just planning. I started out very disciplined and controlled. But then I underwent a personal revolution and got converted to spontaneity! Now I just collect lots of notes, ideas, memories, quotes, pieces of music, bits from movies and books — all kinds of inspirations — and keep looking over them and adding to them as I write. I know where I’m going in a general kind of way but I try to let it blossom as I go. I aspire to a balance between the two — a kind of disciplined spontaneity.

Do you ever use dreams as a source of inspiration?

I have once! The Museum of Mary Child was inspired by the worst nightmare I ever had. The chapter in that book where Heloise is first shown the museum is pretty much a description of it.

Did you make any astonishing serendipitous discoveries while writing this book?

At one point when I was a little bit stuck, my boyfriend suggested that I reread one of my all-time favourite novels, Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. Suddenly I realised that I had, to an extent, been retelling it unconsciously. I couldn’t believe I hadn’t noticed it before! Once I was aware of that, I knew the best model for one particular section of the story I was trying to tell. And for me, models are everything.

Actually, I would say that all of my writing is inspired by serendipitous or paradoxical connections between things that are apparently dissimilar or incongruous. I love the fact that you can retell a fairytale as a hard boiled detective story, or give a great 19th romance like Wuthering Heights a contemporary setting. I love unexpected connections, I love serendipity, I love incongruity and I love paradox! I once named a heroine Serendipity Starr.

Where do you write, and when?

Most of my actual working time I spend on the floor in the living room, or sitting cross-legged on my bed, with my laptop on a tray. But the most crucial things happen more unpredictably — perhaps early in the morning, or when I'm traveling somewhere, or because of something I've seen or heard, or even while I'm asleep and dreaming. That's when things in my head shift. They feel like seismic shifts. So I make lots of notes, wherever I happen to be. Then I write them properly and revise them later, sometimes much later, at the computer.

What is your favourite part of writing?

Oh, the seismic shifts! They don’t just help me to write. They show me how to live.

What do you do when you get blocked?

I daydream! For me, the best time for inventing something is early in the morning, after I've woken up but before I get up. I try to let a story tell itself to me.

How do you keep your well of inspiration full?

I feed it (to mix a metaphor)! I'm a great believer in cramming yourself with culture — books and films and music and art and poetry and non fiction and anything of interest, really. I read very slowly, on purpose — I like to read every word, and to really drink in the shape of a paragraph. I read prose almost as if it were poetry — which means, unfortunately, that I don't get through as many books as I would like — but when I do get through them I know them off by heart! Lately I've become almost more fascinated by what's NOT there — in a paragraph, I mean, or even a whole story — than by what is. I’m fascinated by how writers achieve their effects — make you love a character, for example, or scare you, or compel you with suspense. I also think deeply, and devote a lot of energy to trying to understand — everything, really.

Do you have any rituals that help you to write?

I used to, when I first started writing seriously. I was a very disciplined adolescent, and this lasted into my mid-twenties. I used to do everything in exactly the same way — from my daily writing pattern, to the phases of preparing a manuscript. It was all very ordered and organised. But then I went through a long period when I couldn’t write at all, and when eventually I started to write again, I found that the only way I could do it was to be much more free-spirited, even a little chaotic. It’s almost like I pretend not to be writing — just, sort of, playing. Otherwise I seem to start spooking myself. The way I write now is actually much more like the way I wrote as a child in primary school than the way I wrote when my first book was published.

Who are ten of your favourite writers?

Charles Dickens, Victor Hugo, Charlotte Bronte, Nicholas Stuart Gray, Hans Christian Andersen, C.S. Lewis, Elizabeth Goudge, Joan Aiken, Lorna Hill, Elizabeth Coatsworth.

What do you consider to be good writing?

This is rather a vexed issue for me. I’m keenly aware that much of what is considered to be good writing doesn’t do a thing for me. This does not mean that I believe that, contrary to expert opinion, such writing is bad.

It’s just that, all my life, I’ve been looking for something in what I read — some kind of an answer to a question that I always seem to be asking, although I couldn’t tell you quite what it is. And unless I find it — this thing I’m looking for — I seem to have little appreciation for the work in question. Or at least, my appreciation is purely academic.

Even if I define good writing as something that has what I’m seeking, it’s still a mystery to me. Ever since I was a child I have tended to read things I like with very intense attention, over and over again. But I still cannot work out how the writers I admire most achieve what they achieve. I always feel myself that I’m writing “blindly” — as if I have no idea whatsoever whether what I’m writing is going to say what I’m trying to say to a reader. I know how I feel about the story and the characters, but how do I go about conveying this to someone else, so that they can feel it too? Similarly, I don’t know how it is that my favourite writers do it to me. It’s frustrating, to an extent, but in a peculiar kind of way it’s also something to live for.

Pursuing this mystery, I mean.

What is your advice for someone dreaming of being a writer too?