Beth Kanell's Blog, page 14

February 4, 2019

New Teen Sleuth Mystery ALL THAT GLITTERS Gets First Award!

Zowie! ALL THAT GLITTERS just won its first award -- and it's not even in print yet!!

Zowie! ALL THAT GLITTERS just won its first award -- and it's not even in print yet!!The Break the Bechdel With Strong Female Characters Syndicate just named "All That Glitters" as its February 2019 pick. Here's why: "All that Glitters" hooks you in the first paragraph and doesn't let go! Beth Kanell has crafted a main character who feels real from the first page, and has already introduced a mother whose voice is all her own-- and certainly someone to reckon with! We can't wait to follow Lucky as she tracks down the person who shot her father, with the help of her two friends who also already show great potential for fully developed roles!

Hope you are following along, on this adventure in off-the-usual-route publishing. After all -- this is OUR Vermont Nancy Drew book (and, just a whisper to you ... like the original, this is a series, with seven more books plotted out already). I always loved Nancy Drew, and was ready for an update. Now, here it is.

Here's that link for the book, and you'll see the Break the Bechdel* "badge" on the page now. Then click the pre-order button (and note the 3-copy version that puts YOUR name in the printed book, too):

https://www.inkshares.com/books/all-that-glitters-c3a600?referral_code=aa13ab43

* Many readers don't yet know about the Bechdel test -- a relatively new way to look for books with strong, independent female characters. To learn more of its history, check out this link. It's named for a graphic novelist based in Vermont, so I'm especially happy to have it applied to ALL THAT GLITTERS. We're in this together, right?

Hugs and hope for today -- Beth

Published on February 04, 2019 13:30

February 1, 2019

For Classroom Use: Black History Month and a Teen Poet

Teen poet Phillis Wheatley. (Photo courtesy of deutschlandreform.com)Welcome to February 2019 -- designated as Black History Month for the year. Based on a recent school visit, I wrote up the "why" for celebrating Black History Month, and added material you might want to use in your own or your child's classroom. (If you're home schooling, it might also be a good fit.) I'd love to hear how you put it to use ...

Teen poet Phillis Wheatley. (Photo courtesy of deutschlandreform.com)Welcome to February 2019 -- designated as Black History Month for the year. Based on a recent school visit, I wrote up the "why" for celebrating Black History Month, and added material you might want to use in your own or your child's classroom. (If you're home schooling, it might also be a good fit.) I'd love to hear how you put it to use ...Black History Month: February 2019

New England settlers from the year 1620 onward wrote a lot of things down: how they planned to make decisions together, who would own how much land, what the weather had been, and what the gardens and forests and hunting trips provided.

They passed this tradition to their children, who kept passing it on. As a result, lots of American history was written by people with roots in New England. They wrote about the world they saw and how they celebrated it.

What they wrote wasn’t complete. They left out things they didn’t care about, or didn’t trust. And of course they left out what they didn’t know about America and the world.

Missing from a lot of our written history is the history of people with dark skins in America. Whether they were Native Americans, or forced immigrants from Africa, their voices weren’t often heard in the pages of history here.

Two people who made early changes to that were named Phillis Wheatley and Frederick Douglass.

1. Phillis Wheatley was born in the beautiful lands of West Africa, probably in 1753. Find the countries of Gambia and Senegal on a map of Africa; that’s where she came from. When she was just eight years old, a local man sold her to a trader passing through, who took her on a ship to Boston, the biggest city of New England at the time. The trader sold her again, to make a profit, and she became a slave to Boston residents John and Susanna Wheatley. Their teen-aged kids Mary and Nathaniel began helping Phillis to read and write, and when she was 12, she could already read Greek, Latin, and the Bible. At 14, she wrote her first poem, called “To the University of Cambridge, in New England.” Then she sent a poem to George Washington. Soon she began collecting her poems into a book. When she was 20, her book of poems was published, and the Wheatley family honored her by giving her freedom from enslavement.

I was sad to discover that as an adult, a hard marriage and a life of poverty followed for Phillis, and she died when she was only 31. But she still amazes us as a teenaged poet. You can find some of her poems in collections in books, and online.

Like Phillis Wheatley, you live in New England, and you have learned to read and write. What kind of poems might come from your life? Are there famous people you would like to share them with? Would you write differently if you thought your poem might last for 250 years? Who might read your poems?

2. Frederick Douglass traveled all around New England when he grew up, including visits to St. Johnsbury, Middlebury, Ferrisburgh, and Castleton. When he visited St. Johnsbury, he probably gave a talk at the St. Johnsbury Athenaeum – so when you walk up the stairs there, you are walking where he once stepped.

Mr. Douglass is celebrated as a Black American, and he had ancestors from Africa, as well as Native Americans and “white-skinned” settlers. He believed in the equality of all peoples, including women, recent immigrants, and people of various skin colors. He surprised many of his audience members with how sophisticated and elegant his speeches were. It was important for New Englanders to listen to Mr. Douglass this way, because it helped them remember that education and a desire to learn could make any person, of any gender or skin color or background, into a strong thinker and a good communicator.

He fought against racism all his life. But he also fought FOR people: for their freedom, and their right to vote. The last meeting he went to was about rights for women, in 1895, a few days before he died of a heart attack at about age 77. He didn’t know his real birthday, but he always celebrated it on February 14, which is now Valentine’s Day.

Black History Today

Written history still gives more pages to people who are famous, rich, and especially look important. We are still catching up with the life stories of people with darker skin.

You can find some exciting stories of the changes Black Americans have created, in their lives and in the world. Scientists George Washington Carver, Mae C. Jemison, and Neil deGrasse Tyson are considered Black Americans. So are musicians Marian Anderson, Louis Armstorng, Count Basie, and 50 Cent, plus of course Beyonce. You can look for Black American artists, writers, inventors, and explorers. Today there are also many Black American politicians, like former President Barack Obama and General Colin Powell. Local author Reeve Lindbergh wrote the story of pioneering airplane pilot Bessie Coleman, whose heritage was both African American and Cherokee.

When you learn about Black Americans who have made a difference in our world, and tell their stories, you are helping to balance out the silence about Black Americans that Frederick Douglass and Phillis Wheatley found in the books they read. You are making a stronger, braver, more complete America with your own words about them.

One Special Note for Fiction and Poetry Authors

Because I write novels and poems, I am very interested in the idea called #ownvoices. You might recognize the label as a hashtag, like the ones you might see on Twitter or Facebook or other social media. #Ownvoices is a way to suggest that the best people to write about the experience of being different kinds of Americans are the people who really live that way. Like Black History Month, #ownvoices is helping to repair unfairness from the past, and to make the future more fair for people whose voices need to be heard. You might want to talk about this and think about how your own stories and poems reflect your own life – and what kind of imagined lives you’d like to write about, too.

-- Beth Kanell, author

Published on February 01, 2019 10:30

January 23, 2019

Research: Vermont's Prohibition Laws, 1850 and 1852

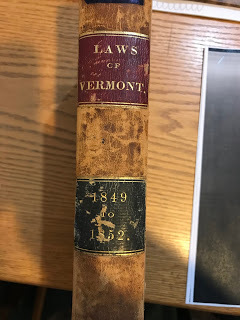

An attorney with an office in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, made available to me this week the text from Vermont's early laws that prohibited alcohol sales, drunkenness, and more. They were earlier than federal Prohibition -- they were passed in 1850 and 1852, and their influence probably resulted in many of the "hidden rooms" of Vermont houses built between 1850 and 1930 or so.

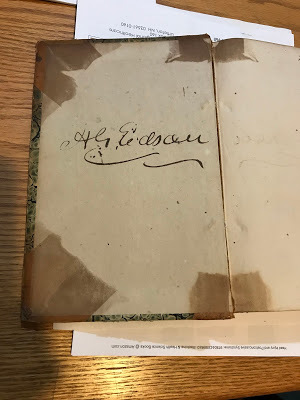

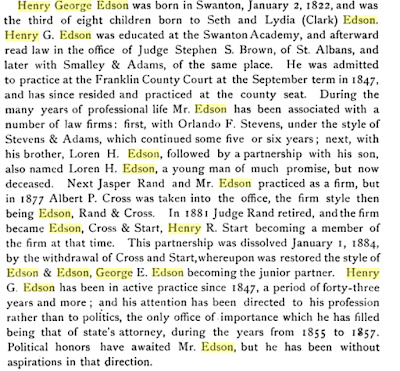

An attorney with an office in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, made available to me this week the text from Vermont's early laws that prohibited alcohol sales, drunkenness, and more. They were earlier than federal Prohibition -- they were passed in 1850 and 1852, and their influence probably resulted in many of the "hidden rooms" of Vermont houses built between 1850 and 1930 or so.The volume of laws, even though it had a lot of years of use, was in wonderful condition. Its original owner's name is stamped on it, as well as inscribed within. Of course, I wanted to know who "H. G. Edson" was. It turns out he was Henry George Edson, a St. Albans lawyer born in Swanton. I'm glad to have turned the pages of what was once his book ... and very excited to understand more about these laws, which will be in the background of the next crisis in THIS ARDENT FLAME, the 1852 adventure I'm now writing.

Onward!

Published on January 23, 2019 13:58

January 21, 2019

"Backstage" at Montpelier's Capitol Building, Looking for Lucky Franklin

A book buddy accompanied me to the State House in Montpelier, to "suss out" the terrain for the suspense scenes in ALL THAT GLITTERS. So she took photos, while I took notes, and Vermont State Curator David Schutz walked us up hidden staircases. We learned the gold on the dome was almost worn away -- that reporters know the back passages -- that the chandeliers can be lowered on powerful mechanical winches, in order to clean their lightbulbs today, or, before electricity powered them, to light the oil lamps in them.

A book buddy accompanied me to the State House in Montpelier, to "suss out" the terrain for the suspense scenes in ALL THAT GLITTERS. So she took photos, while I took notes, and Vermont State Curator David Schutz walked us up hidden staircases. We learned the gold on the dome was almost worn away -- that reporters know the back passages -- that the chandeliers can be lowered on powerful mechanical winches, in order to clean their lightbulbs today, or, before electricity powered them, to light the oil lamps in them.

I wish I'd taken David's photo, but if you don't already know him, just click here. He's charming, erudite, possessive of the sensational beauty that he stewards. And he had an idea: "Can you add homing pigeons to the story?"

Why not?

Why not?And so "scuzzy Sean," one of the most memorable side characters in ALL THAT GLITTERS, was born in a moment under the golden dome.

The novel is my best guess at what a smart, brave, tech-savvy Nancy Drew would be like today -- dealing with Vermont's crime issue of legal "weed." Check it out: You can read it for free here, and if you like it, please do place a pre-order ... we need to reach 750 of those for the book to be published at last!

Published on January 21, 2019 14:13

January 19, 2019

"All That Glitters" Leaps to Life on Inkshares Publisher

I'm thrilled to see my teen sleuth novel ALL THAT GLITTERS available on the new publishing platform Inkshares. Click here to start reading for free!

I'm thrilled to see my teen sleuth novel ALL THAT GLITTERS available on the new publishing platform Inkshares. Click here to start reading for free! Whenever I chat with people about mysteries from childhood, Nancy Drew comes into the conversation. Love her or not, she's iconic, the teen sleuth who solves mysteries with her two "chums" Bess and George.

I wanted to see what Nancy Drew would be like if she lived in Vermont -- today!

The story takes place in Montpelier, after Felicity "Lucky" Franklin races home from college to help her mom. Lucky's dad has been shot, and Lucky's mom got arrested on suspicion of murder. Although Lucky quickly helps her mom to "lawyer up" and get released (the evidence is clear!), there's still someone threatening to injure her family and finish off her dad.

Is it the city's added taxes or the effect of marijuana for sale? How can Lucky and her friends solve the case -- and will they have to call in Roger, Lucky's ex-boyfriend? Wow, a special risk in doing that ...

Hope you'll click on this link to Inkshares and read along. It's free and easy to read the whole book on the website (press the READ button). Better yet, pre-order a copy.

Inkshares promises that when we reach 750 pre-orders for the book, it will be released as both a paperback and an e-book. Help it reach this goal and get your own first edition this way!

More stories about the book and Lucky Franklin in the coming days. Thanks for checking in!

Published on January 19, 2019 07:11

December 26, 2018

Learning the 1800s: Sunday Mail Delivery

As I write THIS ARDENT FLAME, set in northern Vermont in 1852, I spend a lot of time in research -- but not just exploring this pre-Civil War decade of ferment. In order to understand the thinking and discussions of the time, I often backtrack to the War of Independence and the strong-minded individuals who voiced their dreams for this new nation, built from a set of very different colonies and then growing by annexation of territory (and almost always while ignoring the history and rights of Indigenous peoples).

As I write THIS ARDENT FLAME, set in northern Vermont in 1852, I spend a lot of time in research -- but not just exploring this pre-Civil War decade of ferment. In order to understand the thinking and discussions of the time, I often backtrack to the War of Independence and the strong-minded individuals who voiced their dreams for this new nation, built from a set of very different colonies and then growing by annexation of territory (and almost always while ignoring the history and rights of Indigenous peoples).This week I'm reading Compassionate Stranger: Asenath Nicholson and the Great Irish Famine, by Maureen O'Rourke Murphy. One reason to read the book is as background for how the characters in THIS ARDENT FLAME deal with the Irish immigrants arriving in Vermont at the time. Another is that Asenath Nicholson, an activist of the first half of the 1800s, was born and raised in Chelsea, Vermont, not far from the Northeast Kingdom. (I've spent many hours there as the mom of an actor in a Jay Craven/Howard Frank Mosher film. Where the Rivers Flow North.)

Every detail in the book takes me digging for more details elsewhere, and this morning I "dug into" Sunday mail delivery. I was surprised to learn that it was routine in our nation's first century: It was considered essential for commerce! Moreover, the 1820s/1830s movement to end Sunday mail delivery came out of a small group with religious passions and especially religious bias -- against those Irish and other Catholic immigrants, who often used their "day of rest" to feast, gather, and rejoice, rather than to endure the silent solemnity of a Puritan-style Sabbath.

The post office with its mandatory Sunday opening (required by law to be open at least one hour each Sunday) became a social location. Not only did men gather there to pick up their letters and commercial orders, but they also often sat down to socialize, drink, and play cards. This horrified those who took their Sunday worship more seriously. Interestingly, these horrified individuals were often the same ones pursuing the Abolition of slavery, out of the same Christian beliefs!

Thus, Arthur Tappan, an ardent abolitionist of both New York City and New Haven, CT, would raise as much anger by his "Sunday mail laws" campaign as by his campaign to end slavery, and his brother Lewis, campaigning the same way, had his house broken into in 1834 by an angry mob.

Only 7% of the nation claimed strong religious ties at the time, and most opposed shutting down the post office on Sundays. The invention of the telegraph in the 1840s would ease the commercial necessity of Sunday mails. But the legislation to close the post office on Sundays would not be passed until 1912, and part of the opposition to it lay in favoring one religion over another, counter to the definitive statement of the Constitution that insisted the new nation not pick and choose. (Arguments included the belief that Sunday closing of the postal service would then lead to Saturday closing on behalf of the Jewish Sabbath, to be fair!)

What eventually tipped the nation to passing the closure laws was a combination of two pressures: postal workers wanting a day off like everyone else, and trading the closure for the new service of Parcel Post: being able to handle packages routinely.

That's a lot to think about, in the context of this week's political talk about Amazon, postal rates, and Sunday deliveries that have now resumed!

Published on December 26, 2018 08:37

December 9, 2018

Crossing Paths with Franklin Benjamin Gage of East St Johnsbury

Although it's barely a whistlestop* now, with just a post office and a church and a "free library" on the post office porch -- plus the significant Peter and Polly Park, which I'll write about at another time -- East St Johnsbury was once a hub of manufacture and business. The significant Fairbanks family that nurtured both jobs and culture for the area erected its first mill on the Moose River in East St Johnsbury. Actually in the early days this was "St Johnsbury East" or just "East Village." And it prospered.

Although it's barely a whistlestop* now, with just a post office and a church and a "free library" on the post office porch -- plus the significant Peter and Polly Park, which I'll write about at another time -- East St Johnsbury was once a hub of manufacture and business. The significant Fairbanks family that nurtured both jobs and culture for the area erected its first mill on the Moose River in East St Johnsbury. Actually in the early days this was "St Johnsbury East" or just "East Village." And it prospered.That prosperity and the related emphasis on education were in the background of a youth named Franklin Benjamin Gage, born in the village in 1824. He became a significant inventor in photo processes, and created both portraits and landscape images. I'm enamored of his stereo views of the region, which have become hard to find.

Shown here is a child portrait -- could it be your great-great-great-grandparent? -- probably made in Gage's studio in St. Johnsbury proper. On the reverse, he calls it an "ebonytype": a fancy name for a way of presenting the work that may have emphasized the sharp contrast of black and white in the original portrait. It's hard to tell now ... "ebonytype" doesn't have a definition that I've found, and is only mentioned in a wonderful article on Gage, from which I draw this quote:

The highly researched piece on Gage is authored by Bill Johnson and Susie Cohen -- I don't know who they were/are, and they stopped posting their writing about vintage photos five years ago. But I keep returning to the article, and now it has added meaning because the prime of F. B. Gage's life overlaps the period that's coming to life in my in-progress book, THIS ARDENT FLAME (second in the Winds of Freedom series from Five Star/Cengage). So I am thinking about what Gage may have seen in this image, and why he chose it to promote his work.By 1856 Gage advertised that his was the largest photographic establishment in the state of Vermont; at first offering daguerreotypes and then adding all the modern processes and styles as they became available – ambrotypes, mezzotypes, ebonytypes, cartes-de-visite, cabinet portraits, and so on, as well as displaying and selling his stereo views.

If this IS your four-greats grandparent, please do let me know. I'd love to attach a name to the face.

*Whistlestop: a railroad term. Also pertinent to the article I spent yesterday researching and drafting. You'll see it soon.

[Thanks, Dave Kanell, for the images!]

Published on December 09, 2018 09:09

December 4, 2018

Ruffed Grouse, or Partridge (Pa'tridge)?

One of the challenges of writing a novel set in 1852 is the details that aren't recorded, but that I still want to get "historically accurate" for the story. Today's puzzlement is how to talk about the wild bird known to American colonists, based on their British experience, as partridge -- but corrected in name to ruffed grouse. John J. Audubon painted the birds (see above). And Karen A. Bordeau of the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department also wrote this in 2015:

One of the challenges of writing a novel set in 1852 is the details that aren't recorded, but that I still want to get "historically accurate" for the story. Today's puzzlement is how to talk about the wild bird known to American colonists, based on their British experience, as partridge -- but corrected in name to ruffed grouse. John J. Audubon painted the birds (see above). And Karen A. Bordeau of the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department also wrote this in 2015:Regulation of grouse hunting received no attention for a long period. The first act protecting birds was passed in 1842, affording a breeding and rearing season free from molestation. They could be legally taken between September 1 and April 1, and permission of the landowner was required for hunting.

The regulation was repealed after four years, and grouse remained unprotected until 1862. The second law protecting grouse, passed in 1862, established a shorter season – September 1-February 28 – and four years later hunting was further curtailed by closing the season on January 31. Snaring had been a popular method of capture, and in 1885, was forbidden. By 1929, grouse were so rare all over the state that the Legislature completely closed the season in Coos County on the Canadian border, and in Cheshire County bordering Massachusetts.

And the New International Encyclopedia of 1917 says this:

So, what do my characters call these birds? That's in chapter 4 of THIS ARDENT FLAME (Book 2 of Winds of Freedom).

Published on December 04, 2018 10:28

December 2, 2018

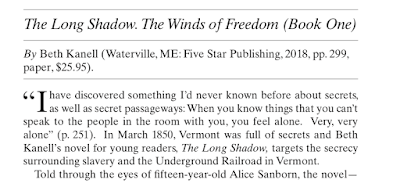

Review of THE LONG SHADOW in Vermont History, Summer/Fall 2018, Social Studies Focus

One of the best tests of a historical Vermont novel with teen protagonists takes place when a social studies teacher -- a professional in the field -- sits down to read it. So I am hugely grateful and honored that Christine Smith, a teacher-librarian at Spaulding High School in Barre, Vermont, and president of the Vermont Alliance of the Social Studies (VASS), chose to read and review THE LONG SHADOW for the summer/fall 2018 issue of Vermont History, the journal of the Vermont Historical Society. I'm posting the review here -- seeing this in print is one of the great benefits of being a member of the Vermont Historical Society. Other articles in this issue focus on Burlington's ethnic communities, a Vermont steamboat pioneer, and Revolution-era hero Seth Warner. All worth reading!

One of the best tests of a historical Vermont novel with teen protagonists takes place when a social studies teacher -- a professional in the field -- sits down to read it. So I am hugely grateful and honored that Christine Smith, a teacher-librarian at Spaulding High School in Barre, Vermont, and president of the Vermont Alliance of the Social Studies (VASS), chose to read and review THE LONG SHADOW for the summer/fall 2018 issue of Vermont History, the journal of the Vermont Historical Society. I'm posting the review here -- seeing this in print is one of the great benefits of being a member of the Vermont Historical Society. Other articles in this issue focus on Burlington's ethnic communities, a Vermont steamboat pioneer, and Revolution-era hero Seth Warner. All worth reading!

Published on December 02, 2018 09:59

My Brain Is Back in 1852 (Writing THIS ARDENT FLAME)

Dishes are stacked a little higher than usual. There's dust under the bed. But the chapters are unfolding, each page a marvel as I "discover" where the new book is going. My feet and my brain are in 1852 (fear not, my heart's still with my honey in 2018, and I can still cook).

Just so you can see what it's like -- at one moment I'm tapping out dialogue and moving the characters to the next scene. And then, quick, it's time to dash back into the research, like these marvelous pages from the 1854 edition of Walton's Register -- a business directory for Vermont that reveals much, much more than who owns what.

Just so you can see what it's like -- at one moment I'm tapping out dialogue and moving the characters to the next scene. And then, quick, it's time to dash back into the research, like these marvelous pages from the 1854 edition of Walton's Register -- a business directory for Vermont that reveals much, much more than who owns what.

Published on December 02, 2018 09:54