Barret Baumgart's Blog: Dumpster Fires, page 2

February 27, 2025

Go Be Forgotten

Before the Trump administration appoints a Fox News host as Service Director for Sequioa National Park and sells off the land to Bank of America for crypto mining and it all burns down, I thought I’d leave this here…

Enjoy this brief essay about the giant sequoia, sequoiadendron giganteum, which survives through routine catastrophic fire.

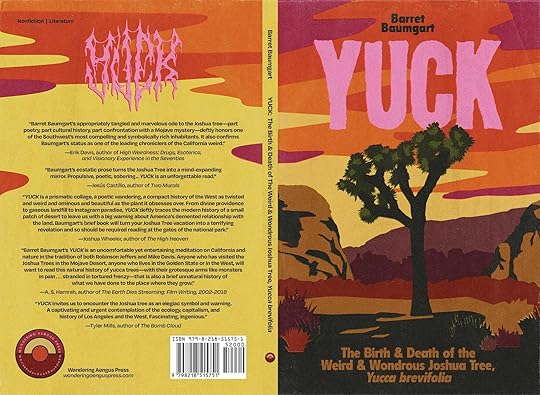

Back in 2020, when I began to write about the Joshua Tree, Yucca brevifolia, my original goal was to construct something like the below—short and lyrical, an aggressive distillation of a vast amount of information rendered in something close to prose poetry. Unfortunately, in the case of the Joshua Tree, that deep research dive dredged a short book.

YUCK drops in one month via Wandering Aengus Press.

Efficiency

EfficiencySIDEBAR: Did you know my last name means ‘Treegarden’?

Expect more from me in the future on California’s other great trees—the Giant Redwood (tallest on earth) and Bristle Cone Pine (oldest on earth). Then my life’s work will be complete, and I can go be forgotten.

GO BE FORGOTTEN

GO BE FORGOTTENThe largest thing to ever stand or swim still occupies a few select groves of California’s Sierra Nevada mountains.

The Mokelumne Indians had a word for it, an onomatopoeia—the cry of the deity that slept in the dead heights of its upper branches, upon a wooden crown where no water reaches. Guardian and protector, the great horned owl. Woh-who’nau. Big tree.

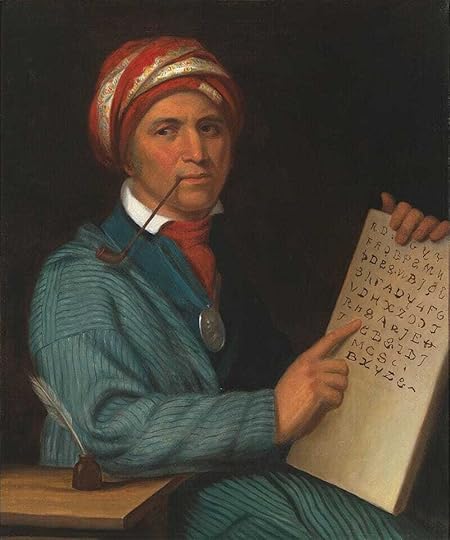

Yet for some reason the species was renamed after a man from Taskigi, Tennessee, a Cherokee silversmith, the only known human being to imagine and perfect an alphabet and syllabary. A man who never set foot in California and died before such massive trees were ever imagined.

“Light a fire under them!” Andrew Jackson said. “They’ll move.”

Some however dispute that etymology. The journals of the botanist Stephen Endlicher never mention Sequoyah, his syllabary, or its failure—those rosses rotted with tears that follow the trail of forced removal.

Sequoyah by Henry Inman, 1830

Sequoyah by Henry Inman, 1830Perhaps the name derives from the Latin sequi, or following, an allusion to several extinct species known prior to the giant sequoia’s discovery and from which they’re believed to descend. The petrified bones of these early autochthons lie strewn throughout the Northern Hemisphere, the rock fields of North America, parts of Greenland and Europe—fallen totems of an unbroken forest that once stretched nearly to the North Pole.

125 million years ago there were pterodactyls sleeping in treetops resembling those towering today a few hours outside Los Angeles. What sound did the birds make in the red dawn that killed the dinosaurs? The collision ignited a global firestorm that incinerated all the forests of earth instantly. Yet somehow the sequoia survived.

A white man named A. T. Dowd officially found them and he had to lie about a massive grizzly he shot before anyone would follow him. The men must have assumed he was sauced again. “Sure Dowd, help you bring the bear down, but I don’t know about any trees.”

Five men spent three weeks chopping down the first sequoia. It held 1,300 rings. They christened it Discovery.

A man named Bidwell said he’d discovered them as a boy. Wooster carved his name in a burnt hollow years before. Walker claimed he found them in 1833. The Prince of Wied stumbled on them in 1832 but no one had spoken up so much before Dowd shot the bear and no one really cared so much for all the hubbub. “Those are my trees,” Bidwell said, “I’m glad they have been found.” The point was they were there.

The year was 1852 and for some there wasn’t enough gold to go around. Word of their size and majesty—“The Largest Trees in the World!” “Language fails to give an adequate idea of it” “The eighth wonder of the world”—spread through the camps and papers and over the wires in a wildfire of certain profit. The men pitched aside their shovels and pans. They fled in droves from the foothills over the higher climes toward a new mother lode rumored.

Later they walked in awkward lines, the lucky ones wearing gloves, as they wielded vast blades welded together to form saws long enough to span the width of those trees that had stood since the Iron Age, trees that antedated Christ, Attic tragedy, and the earliest true writing systems.

The broadest of them, the Boole tree—far wider than a San Francisco cable car stood long—towers alone today over Converse Basin. Franklin Boole, apparently a benevolent man, pardoned the tree and himself after felling and gutting the entire grove of 8,000 trees.

He and the others all said a single trunk could fashion a telegraph pole 40 miles tall. “If cut up for fuel, it would make at least three-thousand cords, or as much as would be yielded by sixty acres of good woodland.” A single trunk might fence in 8,000 acres and put a roof over eighty families’ heads. “If sawed into two-inch boards, it would furnish enough three-inch plank for thirty thousand miles of plank road.”

Mud from the creeks the trees fell across splashed a hundred feet high, splattering the faces of the men. “Its fall was like the shock of an earthquake, and was heard fifteen miles away at Murphy’s Diggings.” A battering ram was deployed to complete the destruction.

The men climbed the canopy branches and trod along the length of the fallen colossus. They adjusted their hats and held still for cameras. Some found wide owl nests which they soaked in the creek like their gold pans prior and they wore them in mockery of the Oriental miners before casting them toward the night’s campfires.

The flaying of the trees required some trouble as the bark stretched some several feet thick but it was completed “with as much neatness and industry as a troop of jackals would display in cleaning the bones of a dead lion.”

“Can any plausible excuse be furnished for the crime of creating the human race?” Mark Twain, a famous comedian, once opined via pencil in the margins of Darwin’s Origin of Species.

Beyond the bark wrappings the men found a quantity of wood sufficient to begin building their new boomtown. However it was all shattered and cracked, unusable. They devised new means, digging trenches and padding them with brush to soften the blow of the toppling behemoths—innovations to no avail. Sanger Lumber Company, under the guidance of Franklin Boole, spent 20 years clearing the 8,000 sequoia of Converse Basin and didn’t make a dollar.

Throughout the epochs, the trees had endured nearly every trial of nature. Harsh warming during the early Holocene. The megadroughts of the Medieval Climatic Anomaly. The shock of a lonely rock six miles wide that wandered out from some hole in the heart of a Milky Way only to bury itself in Mexico after several billion cold years in a place prior to names and the appearance of any recorded light.

The trees might have built beautiful churches, fine mansions, innumerable sanitariums, schools, and prisons. Instead, the broken splinters of the largest single living thing ever known went on to make matchsticks. They made pencils.

“Any fool can destroy trees,” John Muir wrote. “They cannot run away.” In the mountains he filled his pen with primordial ink. “The most royal of all royal purples.” Muir composed his impassioned pleas in sequoia sap. But we should not congratulate ourselves for saving them. “The battle we have fought, and are still fighting, for the forests is a part of the eternal conflict.”

Visit the National Parks and experience what vastness language cannot convey. Speak to the scientists and rangers assembled there about the groves with their instruments and careful measurements, their microphones and pamphlets. The climate is changing they say, growing warmer, and the snowpack is shrinking—a hundred years hence we may lose most of Woh-who’nau, the big tree. And so the conflict continues.

But it’s just such cruelty that keeps them alive.

In the spring, the green cones look like a grain of wheat when the pollen finds them. It takes the dust years to filter through the scales before they close. The cones, hardened and sealed, remind the eye of brown hen eggs but they do not fall and if they did they would not break. Only one thing can move them.

For decades they wait to feel the lick of flames. Then one day, as the world burns beneath them, they open their lips and spit. They do not speak. From the mouths of the cones fly the winged seeds floating on the updraft of flames. The largest living thing in the universe regenerates through routine destructive conflagration. They do not burn. Three feet wide—we know of no thicker skin. Carve your name and walk away.

The seeds take root only after all other life has been consumed.

Extrapolating from this logic, and given all that has come before, the survival of the sequoia seems likely. How odd to think that this monstrous flora shares a certain affinity with the civilization that would erase it. Left to its own devices, a giant sequoia will last two to three thousand years, growing for however long it takes until the intolerable weight of its own expansion eventually topples it.

Loggers felled the 300-foot Mark Twain Tree in 1891. Cross sections of the trunk toured the nation and one of them arrived in London with writing highlighting those rings that corresponded to important human events. 640—Alexandria Library Burned. 1147—The Second Crusade. 1620—Landing of Pilgrims. 1850—The Origin of Species.

At the frontiers of shadow, within the darkened pith at the core of all knowing, in a place where even ants fear to stumble, a wind rises off the mantle, dusting the thread of a web that awaits its own cutting.

Dumpster Fires is a beacon of light in a world of trash and sorrow. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The above essay was originally published in print by the journal The Arkansas International.

January 31, 2025

The Dark Potency of Nonfiction Prose

“Why do you write nonfiction?” “Why nonfiction?” “Why don’t you write, like, a novel or something?” “Have you tried fiction?” “What even is nonfiction?” “What’s non-fiction?” “Nonfiction, like cookbooks?”

For years I’ve called myself a nonfiction writer—an essayist in the mode of John D’Agata, maybe, or Michel de Montaigne, the latter of whom got a good cameo in a recent post. But what is nonfiction? What is an essay? They teach you this crap in school, starting around 5th grade, and for most kids it fosters the first thought of self-harm.

An essay, technically, is an attempt. Not a suicide attempt, but an attempt with no certain outcome. It’s a word derived from medieval alchemy, actually, and means to weigh or measure. Montaigne’s famous motto What do I know? while exceedingly bland on the surface, carries a deeper subtext. What do I know? It is the type of inquiry that, far beyond scientific skepticism, can spur a genuine paradigm shift, lead to ontological shock, invite insanity, or beget a spiritual epiphany—the latter being the actual goal of alchemy.

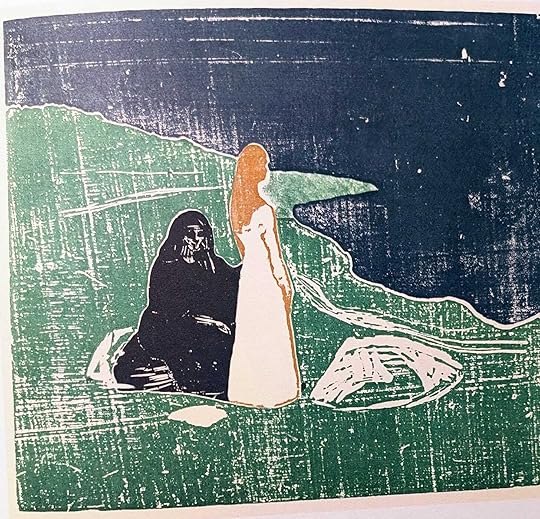

What do you really know? Edvard Munch, Women on the Beach, 1898

Edvard Munch, Women on the Beach, 1898If you smoke DMT, you might discover that you know… not much. As Terence McKenna put it, “Occasionally people ask me ‘Is DMT dangerous?’ and I think the honest answer is ‘Only if you fear death by astonishment.’”

The spiritual teacher, Adyashanti, says that his awakening occurred when he started asking himself, basically… What do I know? “There are no ABCs of how to wake up. But when I look back, I saw these two things: stillness and silence, and the ability to be ruthlessly honest with myself, to not fool myself, to not tell myself that I knew something that I didn’t, to stay with that line of inquiry.”

Such staying power the romantic poet John Keats called negative capability. It is as good a prescription as any for a nonfiction writer or spiritual seeker. “I mean Negative Capability,” Keats wrote in a letter, “that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

And that brings me to the simple point of this brief post:

Not knowing is, for me, the essence—the secret power—of nonfiction. Uncertainty, a point of deep uncertainty, that is the secret clearing in the forest of fact that I want to find through a careful curation of nonfiction information.It is a method, like many philosophical and spiritual traditions, rooted in paradox, and you will see it play out in China Lake and my new book YUCK.

Recently all this came into powerful focus for me reading an essay in the Los Angeles Review of Books called “Weird Nonfiction” by Clayton Purdom. The essay came out in October, but it took a nudge from to help me find it (thanks Matt). Clayton’s essay, I think, perhaps more than anything else I’ve encountered recently, speaks to what I think my writing practice has been pursuing the past 10 years, what it will continue to pursue in my third book, and why I remain stubbornly smitten with the unsexy, less prestigious literary mode of “nonfiction.”

As Clayton Purdom writes:

I call it weird nonfiction: creative work that presents itself as journalism or nonfiction but introduces fictional elements with the intention of upsetting, disturbing, or confusing the audience. Works that are about the real world or some subject within it but also question their container or their ability to be about that thing—or which veer from the thing at hand toward the cosmic, horrifying, or absurd. Sometimes it is as if the element of unreality is chasing the author through the piece…

…Like weird fiction, weird nonfiction is built around some unknowable terror, replacing the tentacled horrors of H. P. Lovecraft with the many-tentacled horrors of being online and alive in the 21st century. It also suggests, in the process, that there is something unfathomable at the heart of reality itself, and that it is the duty of journalism to circumnavigate this terror if never speak it aloud. I humbly submit that weird nonfiction seems particularly well suited to reporting on climate change but have not seen it done with the vigor that subject deserves.

Being the self-aggrandizing solipsistic bastard only child that I am, I emailed Clayton and sent him a copy of my precious opus China Lake. Clayton, I learned, remains on the hunt for further examples of Weird Nonfiction. Send him your recs here. His essay already wrangles an impressive array of examples of this emergent—or subversive—form and he makes a convincing case that it is a genuine if largely overlooked genre.

I urge you to head over to the Los Angeles Review of Books and read the full essay. It gave me a pretty potent shot of adrenaline last week... Edvard Munch, Encounter in Space, 1899

Edvard Munch, Encounter in Space, 1899But maybe it’s just me, and Clayton… Two lame bros having some kind of weird encounter in digital space. Maybe we have it all wrong. Maybe nonfiction should really just stick to informing the reader, supply useful information in a trim and logical 5th grade five-paragraph package. Let ChatGPT write your dirty laundry for you. The layman on the street would say that’s the proper way, the aim of nonfiction. A grim little utilitarian genre.

But what if there is and has been a literary form that takes information and fact and applies it toward an end that vastly surpasses the sum of its truthful, ‘verifiable’ raw material? What if there is a form that in its strategic curation of information, particularly destabilizing information—like that related to anthropogenic climate change perhaps—builds toward not knowledge and understanding specifically but something else entirely. In its curation and careful presentation, it draws attention not to the genius of our species but rather our sheer unlimited capacity for producing, collecting, and amassing such facts as might flatter that faculty, and yet, in the artful, even poetic, piecing together of such endless informational bits, it tries at last to build out toward some teetering highly tenuous vantage point from which we might steal a glimpse of what all that obsessive facticity might one day illuminate… or simply be masking.

As H.P Lovecraft, patron saint of the weird, famously wrote in 1926:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Weird Nonfiction revels in this precise moment, this schism between knowledge and decay, illumination and chaos, the known and the not allowed. It is the piecing together of disparate knowledge to reveal something hitherto unseen beneath the smooth surface of our complacent, lying consumption.

“Writing is about discovering things hitherto unseen. Otherwise there’s no point to the process.” —W.G. Sebald

Weird Nonfiction, in its careful curation and amassment of fact, does not seek firstly to inform the reader, to edify him or her with knowledge, to offer information that might help them navigate the world’s increasing ‘complexity.’ No. It actually seeks the opposite. It has the intention of upsetting, disturbing, or confusing the audience.

And if there is any defense for this dubious project, well… it is that such disorientation is the true goal of art itself.The realization that we do not know, that we did not know—that is the first step in any awakening. The human species is destroying itself and the planet it lives on and shares with all currently known extant life in the universe because it has forgotten precisely how to dwell in uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts. Perhaps we never really knew. We’re stuck writing our shitty five paragraphs, busy explaining everything, making arguments, proving we know.

But Weird Nonfiction, if it is anything, represents a powerful and paradoxical contemporary pathway into the abiding mystery that underpins and outstrips all our expanding networks of firm and cloud-based present and future fact. It invites you stop trying to decide what you know and asks instead that you experience all that you don’t. And it does this, quite strangely, even sublimely, by piling on all that is true and known and verifiable in the moment this very evening.

Truth is stranger than fiction, than speculative fiction, even than science-fiction. That is because unlike fiction, it is not obliged to stick to possibilities.

Scope the essay “Weird Nonfiction”, stay awake, and stay tuned.

Dumpster Fires is a beacon of light in a world of trash and sorrow. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

January 11, 2025

Los Angeles is Burning

Perhaps you’ve seen the news. Los Angeles is burning—worse than ever before. Fires keep starting. They keep on expanding. Give your phone a good long doom scroll. This is what it’s all about.

This scenario, the destruction of the Angel City, has been lovingly portrayed in film and literature no less than 138 times according to the last count of the late critic Mike Davis. “Los Angeles is the city we love to destroy.”

Die, Die My Darling

Die, Die My DarlingThe Palisades Fire is slowly creeping toward me and a few more million people. Tom Petty’s house will probably be toast. Pick your favorite celebrity.

All the vampires walkin' through the valley / Move west down Ventura Boulevard / And all the bad boys are standing in the shadows /And the good girls are home with broken hearts —Tom Petty, “Free Fallin’”

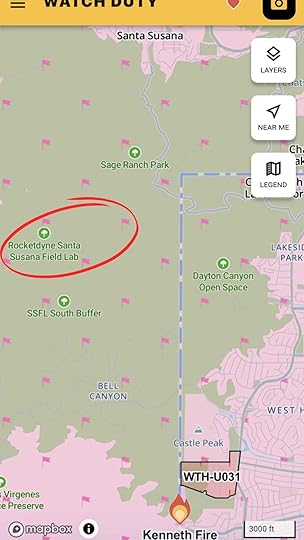

But you can’t stay home. Evacuation orders extend to Ventura Boulevard. Not far from me. Feeling pretty good. I guess this vampire pictured below, a homeless man armed with a flame thrower, wandered off the Blvd and set the Kenneth Fire, just south of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory. Good stuff! Not a big deal. This is fine. Everything is fine.

O! Kenneth!

O! Kenneth!

I guess the dude probably read too much Mike Davis, Joan Didion, Morrow Mayo, Robinson Jeffers, Carey McWilliams, Nathaniel West, Brett Easton Ellis. All the good critics salting the ‘semi-tropical’ paradise with a century of very rational pessimism about the prospects of this most unnatural region. Fuck. Maybe the bro read me. The film critic at N+1, A.S. Hamrah, said my new book about Los Angeles and Joshua Tree, YUCK, is “an uncomfortable yet entertaining meditation on California and nature in the tradition of both Robinson Jeffers and Mike Davis.” Good stuff! At least Erewhon is offering Ophora Hyper-Oxygenated water at a discounted price to the community of Calabasas before it burns down. $19.99 for a special limited time instead of the regular $26.99. Pour some on the grass or something.

Why is any of this happening? What is happening? I don’t know. But I can tell you some history. LA is Big. Too Big. It was prefigured in the original Spanish name of the place….

Los Angeles—officially, per 1781 decree, El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula—“The Queen of the Angels,” she is dry and tired now. Not too big to fail. Vast swaths of her parched and tattered chapparal robes are going up in plumes of toxic black smoke. She lost her virginity way back in the day. Raymond Chandler, dying of alcoholism in La Jolla in 1948, called her, “Just a tired old whore.”

The novelist Myron Brinig was a little nicer in 1938: “Los Angeles is a middle-aged obese woman from somewhere in the Middle-West, lying naked in the sun. As she sips from a glass of buttermilk and bites off chunks of a hamburger sandwich, she reads Tagore to the music of Carrie Jacobs-Bond.”

It is Chandler’s “Red Wind” that is causing all of this again. That awful Red Wind, the Santa Anas.

“There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen. You can even get a full glass of beer at a cocktail lounge.”

I wrote in a previous post how I vowed to quit drinking, unlike Chandler, in order to finish that failed book about the Santa Susana nuclear meltdown.

Well, I’m happy to report that I succeeded. I quit drinking without issue in the summer of 2022. It’s now been over 30 months since I took a sip of alcohol. Yet I almost walked into a cocktail lounge and downed 87 IPAs the other night.

Yes, the site of the Santa Susana nuclear meltdown almost caught fire again the other night.Did you know it burned in 2018 releasing untold radiation all over some of Los Angeles’s most famous residents, including Kim Kardashian? That made her pretty mad. Sucks to find out your $10 million dollar mansion backs up on a nuclear meltdown site nobody ever bothered to tell you about or clean up. It was during that fire that I actually I fired my agent (I need one still)—when he wasn’t ready to move quickly enough on that disaster and sell the book about the meltdown. I was gonna cash it all in, buy a yacht, and move to Bali. But it wasn’t so easy (death threats).

Screenshot of my Watch Duty app, 3:51pm, at the start of the new Kenneth Fire

Screenshot of my Watch Duty app, 3:51pm, at the start of the new Kenneth FireIn any case, the stakes are high here at the end of the Valley tonight, at the end of Los Angeles, at the end of continent, terminus of the west—where we finally ran out of land—where the houses were tossed up quickly all over the canyons, strung below meltdowns, staked high on hillsides fated to burn since the beginning of time.

The word palisade means stake. A wooden post fortifying a temporary camp.

We were never supposed to stay—nothing here was built to endure.“The mind is troubled by some buried, ineradicable suspicion that things had better work here,” Joan Didion wrote of Los Angeles, “because here, beneath that immense bleached sky is where we run out of continent.”

“There is something disturbing about this corner of America, a sinister suggestion of transience.” J.B. Priestley wrote, “a quality, hostile to men in the very earth and air here.”

Henry Miller spent the last years of his life in Los Angeles, in the Pacific Palisades—which no longer exists.

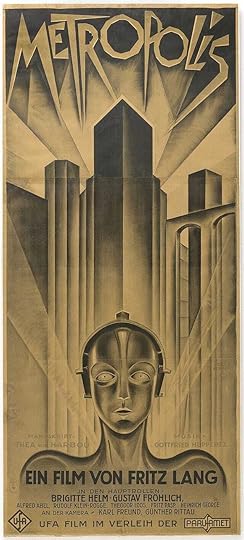

“Los Angeles gives one the feeling of the future more strongly than any city I know of,” Miller wrote. “A bad future, too, like something out of Fritz Lang’s feeble mind.” Fritz Lang, the director of Metropolis.

El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula

El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de PorciúnculaThe Reluctant Metropolis (1997) by William Fulton ponders the metropolis’s vast and puzzling expansion. “For the last hundred years, Los Angeles has been one of the most effective growth machines ever created.” The city’s rise “can only be explained as a remarkable victory of human cunning over the so-called limits of nature.”

Fulton’s book followed The Fragmented Metropolis (1967) by Robert Fogelson. The book begins with a quote from an English traveler, one Morris Markey, who in 1932 wrote that “alone of all the cities in America, there was no plausible answer to the question, ‘Why did a town spring up here and why has it grown so big?’”

This victory over natural limits, the total implausibility of the city, it comes into focus further when you see it as an Island on the Land, the name Carey McWilliams gave to his seminal 1946 essay on the Angel City.

According to Williams, the “great expansion” of LA and indeed all of Southern California is “the more remarkable in view of the fact that the region had so few natural advantages. “It was short of water, short of fuel; it lacked mineral and forest resources; and, with the exception of San Diego, there was not a single good natural harbor south of Tehachapi.”

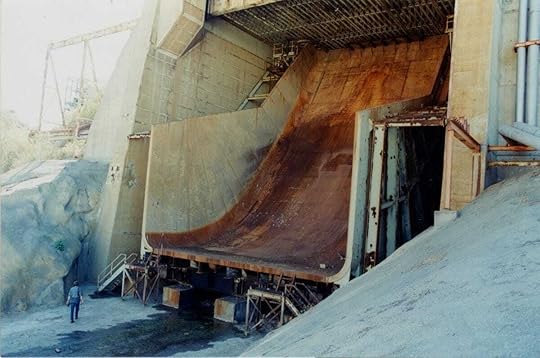

It did have a river at least—not that it was navigable. It starts, actually, literally, at the Santa Susana Field Laboratory, trickling down off the radioactive hills, bringing water down through Bell Creek, Bell Canyon, and into the flood control channels everyone on earth has seen probably thanks to that famous chase scene in Terminator 2.

Ironically, in October 2007, it was the Terminator, Arnold Schwarzenegger—then governor of California—who declined federal Superfund status for SSFL after reaching an “agreement” with NASA, Boeing, and the Department of Energy.

Ironically, in October 2007, it was the Terminator, Arnold Schwarzenegger—then governor of California—who declined federal Superfund status for SSFL after reaching an “agreement” with NASA, Boeing, and the Department of Energy.Among the other natural phenomena LA was known to enjoy—routine droughts, massive wildfires, catastrophic floods and earthquakes—several might have assisted the progress of erosion over vast inhuman epochs. Few however would help lay the foundations for an expanding megatropolis.

And yet? Los Angeles, “the City that Grew,” was the quaint phrase coined by an early LA historian. “Actually, Los Angeles has not grown,” McWilliams wrote, “it has been conjured into existence.”

From out of nothing: Something. BOOM! “Los Angeles! There she Blows!” was the name of the most famous essay about Los Angeles before World War II.

After the war, when the sodium reactor core blew up at the Santa Susana Field Laboratory in 1959, laboratory crews used Kotex pads to mop up the radiation. Pretty cool stuff. I wish I was making it up.

“Southern California is a great laboratory of experimentation,” Carey McWilliams wrote. “It is a great tribal burial ground for antique customs and incongruous styles.” Who says Nuclear Cowboys shouldn’t use period pads to save the planet! Too bad they couldn’t tell their wives and kids about the innovations up the hill as it was top-secret government work and could entail treason and a trip to the electric chair. Ouch!

An estimated 10 experimental nuclear reactors operated at Santa Susana between 1953 and 1980. “It was my impression that Atomics International had been given verbal instructions from the Atomic Energy Commission to test the reactor to destruction,” one former SSFL employee confided to interviewers in a redacted government report. “They were pushing the limits on purpose.”

Limitations were not something welcomed in Los Angeles. “I am a foresighted man,” Henry Huntington said in 1890, “and I believe Los Angeles is destined to become the most important city in this country, if not the world. It can extend in any direction as far as you like.”

And by extension, it would seem, so too its fires. Always those fires. They’ve always been here…

Dona Magdalena Murrillo, born in 1848 on the Las Bolsas Rancho, said “When the Santa Anas came, no one dared light a fire, even in a stove…” She thought the name derived from the Santa Ana Pass. Others have speculated that the Santa Anas derive from Satanas—a wind sent from Satan to spread fire across the land.

“The city burning is Los Angeles’s deepest image of itself,” Joan Didion wrote.

“No one knows what tremendous extent of folly and of tragedy may be chargeable to this same shrill, shrieking, moaning, sobbing wind from the deadly desert,” George Randolph Chester wrote in 1924, a wind in which “through the yellow sunlight there sift vague phantom shapes of impalpable dust…”

Nathaniel West imagined fire, “The Burning of Los Angeles,” at the end of his early apocalyptic LA novel, The Day of the Locust.

“Los Angeles will burn to the ground,” Sandra Good, one of the Manson Girls, prophesized after a court hearing in downtown LA in the early 1970s.

“There is nothing to match flying over Los Angeles by night,” Jean Baudrillard wrote in America. “Only Hieronymus Bosch’s Hell can match the inferno effect.”

Hieronymus Bosch, Hell (1510)

Hieronymus Bosch, Hell (1510)The other night, as Los Angeles’s fifth, sixth, seventh fire—what is it?—began just south of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory, it did seem as good a time as any to drop the final post in my series “The Heights of Weird.”

It was, after all, events tied to the massive 2018 Woolsey Fire, which started in Area IV of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory during heavy Santa Ana winds, that more than anything revived the dark suspicions I’ve dredged throughout this series over 7 months and to the disastrous tune of 25,000 words. Yet for some reason I waited.

Why? Throughout all the chaos and destruction, it stands there defiant, uncanny—a disturbing uber synchronicity forcing us, if we can listen, to reckon with our fragile place in the cosmos, our tentative grasp upon the planet; a mystery waiting beyond the wisteria walls of our McMansions, beyond our adolescent tribal warfares, the tawdry chauvinisms of our paranoid species, our utter inane terror before anything unknown.

What is this Angel City that, like a cancer, has made growth an end in itself?

What is the true secret hiding inside Santa Susana that made it such a perfect sequel to my book China Lake and has—in fact—ruined my life and maybe, somehow, might save us, assuming we survive? Assuming we care to listen.

I said in my last post… It’s probably nothing. There’s nothing really up there. No big deal! Everything is fine! Turn away! One brush, that was enough!

“This 2,800-acre plateau, now the Santa Susana Field Lab, and perhaps one day to be open space protected from development, was and is the place where cosmic order is revealed. ”

Flame Bucket, Santa Susana Field Laboratory

Flame Bucket, Santa Susana Field LaboratoryFew places on earth have known more fire than the Santa Susana Field Lab.

Stop the doom scroll. Scope the final chapter in my series “The Heights of Weird.”

Click here.December 24, 2024

Pre-Order My New Book

Dear Friends, please consider pre-ordering my second book YUCK for yourself or a loved one this holiday season. Click here to purchase the book on Amazon.

“YUCK is a prismatic collage, a poetic wandering, a compact history of the West as twisted and weird and ominous and beautiful as the plant it obsesses over…“From divine providence to gaseous landfill to Instagram paradise, YUCK deftly traces the modern history of a small patch of desert to leave us with a big warning about America’s demented relationship with the land. Baumgart’s brief book will turn your Joshua Tree vacation into a terrifying revelation and so should be required reading at the gates of the national park.”

—Joshua Wheeler, author of Acid West and The High Heaven

YUCK drops 3/25/25, published by Wandering Aengus Press.

Dumpster Fires is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

December 20, 2024

YŮCK Imposes Yuletide Cheer

Dear Friends,

This holiday season consider purchasing family, lovers, and even yourself something weird: YUCK, my second book, published by WA-based indie press Wandering Aengus. Feel free to judge YUCK by its cover and preorder on Amazon today.

Influential author and critic says of YUCK:

“Barret Baumgart’s appropriately tangled and marvelous ode to the Joshua tree—part poetry, part cultural history, part confrontation with a Mojave mystery—deftly honors one of the Southwest’s most compelling and symbolically rich inhabitants. It also confirms Baumgart’s status as one of the leading chroniclers of the California weird.”

Please help me spread the word by sharing widely with friends and colleagues. Social media posts are also super important!

YUCK on Amazon: https://a.co/d/4Tdg5Lq

Find me on Instagram @barretbaumgart

Visit my website for more info barretbaumgart.com

If you know someone important out there who you think would dig this book and needs a copy ASAP please feel free to reach out to me by responding to this email.

YUCK officially drops March 25, 2025. The book is 130 pages.

EVENTS:

A release party is planned for Wednesday, March 26th at Angel City Brewery in downtown LA featuring Deanne Stillman, author of the nonfiction cult classic, Twentynine Palms, a Los Angeles Times bestseller that Hunter Thompson called, “A strange and brilliant story by an important American writer.”

Some days, depending on the weather, YUCK appears to be blazing an icky little path through Amazon’s least competitive category, “Desert Ecosystems.” Purchase your copy before it passes into extinction, like the Joshua Tree itself…

Happy holidays to you all and thank you for your continued support!

—Barret

P.S. A new post is coming (soon!) that will wrap up my series “The Heights of Weird”, explaining—among other things—just how my failed book about the Santa Susana nuclear meltdown was (and is) a sequel to my book China Lake. Spooky, funny, fucked up stuff is coming… Apologies for the length and complexity of the “Weird” series and the long intervals between posts. If you are reading them, you are watching me—in real time—take the necessary fraught steps toward the forbidden country at the heart of my third book.November 13, 2024

In a Future Far, Far Beyond the Festival

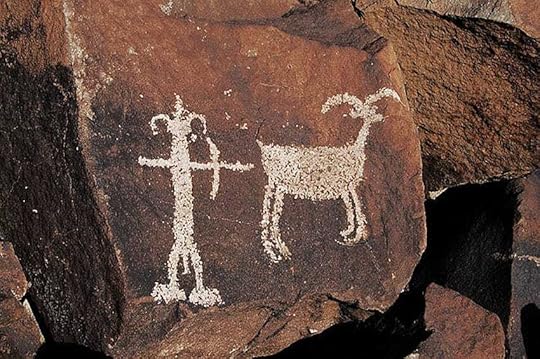

At the start of November I returned to the Mojave Desert to attend Ridgecrest’s 10th annual Petroglyph Festival. I’d been following the event for a decade, ever since I became obsessed with the petroglyphs on the China Lake naval base while writing my first book, but something felt different this year. At first I couldn’t figure it out.

Outside the main gates I met the same protestors, members of the local Kawaiisu Nation, who continue to oppose the festival and the permanent petroglyph reproductions displayed throughout the city. Inside, beyond the quiet picket line, there were the same paid Native Americans who had traveled from New York, North Carolina and elsewhere out of state to don feathers, pound drums, and offer up prayers to a Christian God. I bought a corn dog, skipped the kettle corn, admired the dreamcatchers galore and cedar incense and saw the same howling wolf hoodie made in Bangladesh I bought way back in 2010 at the Crazy Horse Memorial in the Black Hills of South Dakota. A wild donkey rescue called Breakfast Burrito kept Christina engaged as I wandered on, circling the arena where a hoop dancer, Eric Hernandez, who’d driven up the night before from Los Angeles, like us, put on an impressive, athletic performance for families and children perched on bright haybales. And none of it, the same as always, had anything to do with the petroglyphs, the ancients who created them, nor the local tribes who revere the Coso Range as the hallowed ground of all creation.

A little after noon, in a large tent that functioned as a green room, Bob Blackwell, a representative of the Kawaiisu, approached Eric as he sat breathing through an inhaler, winded from another masterful hoop performance. Bob handed him a flyer.

“I didn’t know anything about this,” Eric said, referring to the Kawaiisu’s ongoing condemnation of the festival, which the Kawaiisu have not been invited to join. “It would be like back east if the city hosted a pow-wow and did not invite the Lumbee.”

A Ridgecrest city official then entered and told Blackwell he was trespassing. He was invited to leave, and I was informed I’d be receiving emails from the city attesting to the fact that Kawaiisu had been invited to attend the festival. Those emails, however—I suspect much like the actual invitation—have yet to be sent.

A Petroglyph Festival that invited the culture of the Kawaiisu would not help fill city hotels. A festival that invited the history of local tribes would not be good for business. Their lodgings would take longer to erect than the Costco pop-up tents. Their clothes would look less colorful before the cameras. And the prayers, not offered in English, might fall on deaf ears. Rather than the PA-amplified tales about Coyote and Rabbit, the history of the locals would have to include the horrors of being hunted, mass slaughter, forced removal, slavery, disinheritance and—finally now, at last—their sacred symbols, the petroglyphs, being sold off as crappy kitsch for bored tourists.

Or perhaps not. In all fairness, there was one element absent from the festival this year. And it was this omission that took me a moment to notice. Petroglyphs. There were no petroglyphs displayed throughout the actual festival grounds. Not that I saw.

On the one hand it is a profound victory for the local tribes who object to the exploitation of their culture and religion for monetary gain. On the other, the defeat of the festival, so complete it can no longer display its namesake images, lent an eerie atmosphere to the day’s proceedings, especially after the wind picked up. The artwork was both there and not there. Palpable, a possibility scintillating at the periphery, but everywhere absent, omitted. Named but refrained. It felt off, ghostly even, like the glyphs that line the long lava hallway of Renegade Canyon, climbing higher and higher along the walls in layers of tortured palimpsest until the artwork and eons end abruptly at the cliff edge and your eyes empty out the swarms of bighorns into the blinking pale salts of the dead lakebed miles below. The artwork of the Coso Range could be a UNESCO World Heritage site, revered alongside other awesome and even lesser ancient achievements scattered across the globe. But it is not. Few have ever even heard of the place. This despite the best efforts of the town of Ridgecrest. And of course, behind it all, sequestered in the research silos scattered underground throughout the desert highlands, like a sidewinder coiled in the shadows, the US Navy—current owner of the petroglyphs—remains silent, its slick tongue sniffing the air, always sniffing, but never saying a word.

What do the images mean? Who created them? Who do the petroglyphs belong to? To where have they vanished?

The answer today is the Navy. The Navy owns 300 miles of petroglyphs carved throughout the canyons of the Cosos that no one can access at present—not even the local tribes. It is the Navy who, through negation, decides what the images mean. The Navy that carefully hoards them in the name of National Security. The Navy says who can see them. The Navy that forces the tiny tagalong town beside the base to suck whatever magic it can from the distant walls of desert varnish, cramming it into the increasingly sad package of a ‘Petroglyph Festival’ that no longer contains any petroglyphs.

A lousy country fair is all the festival will ever be so long as the city can only mime the mystery in the distance, reproduce the petroglyphs in parking lots, and pay Cherokees to point vaguely toward the distance, their elders and chiefs not even knowing which mountain range contains the riches few eyes will ever see.

Why doesn’t the base help out their little city? Why won’t they assist? Why, as President David Laughing Horse Robinson of the Kawaiisu Nation told me, why are the tribes unable to access the petroglyphs in recent years? What changed? Have the petroglyphs in fact disappeared, vanished far beyond the counters, craft tables, and credit card machines of the festival grounds, into some interdimensional rift opened up by some disastrous new weapon the Navy’s testing?

The base says they take the business of preservation seriously. I believe them. My guess is that that they need the petroglyphs. For a long time, they’ve required them for something. I’ve come to believe after more than a decade orbiting the base that it’s not a coincidence that the US military owns this supreme source of ancient supernatural power. US National Security doctrine rests upon an unchallenged ability to visit egregious harm on one’s enemies. It does not rest upon an expanding awareness of our shared human destiny and common heritage on this fragile paradise of a planet. If the local tribes, the out of towners, and the city officials all want to come together to fight one another at a festival outside Death Valley each year, why would DoD give a shit?

Such scuffles keep the focus on the foreground.

The one thing they don’t want is for you to turn around and train your gaze on the vast and implacable base. The one thing you’re not supposed to do—whether you’re the town of Ridgecrest, the Kawaiisu Nation, or a nonfiction writer living in Los Angeles—is to perk up and peer past the dumpsters and strip malls, out beyond highways and power lines to the volcanic headland looming over the dry lakebed. Indeed, the tens of thousands of signs pinned around the base’s perimeter tell you just that: Look Away, Go Away. WARNING. NO TRESPASSING. Is it treasonous, a breach of faith, a futile confession of naivete to look to that larger background and ask, seriously, who really owns the petroglyphs—and why—and what does that ownership really mean?

Would America be less safe if China Lake surrendered a small corner of the base? Would the fleet forfeit dominance if some precious scrap of land slipped out of their 1.2-million-acre hands? Haven’t they held onto all those canyons long enough? Is there not one they might slough off some year, like a snake shedding its skin, as the battlefield shapeshifts into further unfathomable cyber bits? Isn’t over 80 years on lockdown long enough? If for some reason the in-house techno shamans and wizards of defense must keep those hunting scenes in their war cabinet a little longer, at least let them set a time limit.

Conflicting interest groups across the region should recognize the sidewinder in the room. A broader vision for the Coso Range and its petroglyphs and hot springs might see the sacred lands of the Cosos returned to those Native Americans to whom they once belonged and for whom they remain the most sacred site on earth.Such lands, once transferred, might be organized not into a National Park but a Tribal Park administered by and for the benefit of the indigenous peoples of the region. Or not. It would be up to them to decide their destiny.Such a path forward may appear impossible, it may take decades, it may be insane, but I believe it’s time to peek beyond the puny festival and the inviolable prerogatives of the Navy and ask why—why couldn’t, and why shouldn’t, such a future exist?

And who knows… maybe, down the road, the hotels are full.

The sidewinder coiled round the Cosos

The sidewinder coiled round the CososListen to clips from my interview with David Laughing Horse Robinson in the video above or click here.

To learn more about the Kawaiisu Nation, their history, and their protest of the festival, visit their website.

To learn about how I ever became involved in any of this—the story is weird—you can read my ongoing series, “The Heights of Weird.”

If anyone from the city would like to broaden this reporting, they can email me at barretbaumgart/gmail or they can again create a new Substack account under a random name and have ChatGPT crank more sophist tripe about behavior rooted in White Saviorism that upholds colonial power structures.

Read my original Petroglyph Festival essay here.

Dumpster Fires is a beacon of light in a world of trash and sorrow. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

October 22, 2024

Fence Lines of the Rational Mind

“It had been a coincidence to force one to contemplate the very design of coincidence… Many a writer lives with at least one sense cocked to the possibility that some events are magical, and if so, how do you write about it?” —Norman Mailer

My second book, YUCK, about the Joshua Tree, Yucca brevifolia, is set to come out in March 2025. You can listen to a pretty outrageous sample of the book’s audio version, which I recorded a few weeks ago at my friend Cory’s studio, by clicking here.

Reading that book aloud the other day got me thinking—surprise, surprise—about that other project, the prior failed one, the book about the nuclear meltdown. I had just finished the first draft of YUCK and was camping in Joshua Tree, California in February 2021 when it struck me that if I was ever going to get my shit together and finish that other book, the big one, the one about the meltdown at Santa Susana, there were a few issues I had to sort out first.

One of them was drinking. If I was going to find the concentration and stamina necessary to finish that project any time soon, I had to stop drinking.

The other was coincidence. It seemed to me that if I was going to sort my thinking out enough to take a clear stab at that Santa Susana book, I had to “research” coincidence.

The latter problem was something that had begun to worry me long before the drinking. In some ways it was more worrisome. My identity could easily endure admitting that a substance I reached for too regularly—every day since turning 21—had taken over too much of my life. I could admit that this material entity, a molecule, ethanol, had hijacked my writing. There was no great loss in this admission. I just had to confront the hijacker and eject him before he drove us off the cliff. But coincidence was different. I could Google alcoholism, get behind the idea that this guest was slowly derailing me, luring me off my chosen path—millions of people pull to a roadside tavern and end up letting him carry their keys for far too long.

But coincidence? I think it’s safe to say that things really aren’t going well if you find yourself suddenly Googling coincidence. In the initial post that launched this faltering series “The Heights of Weird,” I wrote that the real reason I had traveled to Stanford University to talk to Bill Gates’s climate advisor, Dr. Ken Caldeira, was to share something that I had learned, a discovery that I had made. That discovery was, as a later post made clear, a certain coincidence, and if not one fit to ‘force one to contemplate the very design of coincidence,’ at least one pretty fucking weird. Weird enough that I started writing the book China Lake.

For over 20 years, beginning in the 1950s, the US military studied cloud seeding at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, a military base a few hours northeast of Los Angeles in California’s Mojave Desert. Later, the CIA and Air Force, in a now infamous and once highly classified operation known as Project Popeye, deployed NAWS China Lake’s cloud seeding system as a weather weapon during the Vietnam War.

Similarly, in a continuous attempt at creating rain, Native American shamans long before the arrival of white Europeans spent thousands of years carving bighorn sheep petroglyphs on the volcanic canyon walls that crisscross what are today the China Lake base’s vast bombing ranges. As the renowned archaeologist David Whitley has demonstrated, dozens of statements found throughout the Native American ethnography of California attest to a link between bighorn sheep, rainstorms, thunder, lightning, and rainmaking on the part of shamans.

“It is said that rain falls when a mountain sheep is killed. For this reason many sheep-dreamers thought they were rain doctors.”

Put another way, the improbable modern-day practice of cloud seeding, a technology in use today in nearly every arid country the world over, emerged out of the very same Stone Age canyons once consecrated to ritual rainmaking by Native shamans. “‘Killing a mountain sheep’”, as David Whitley writes, “was a metaphor for the acquisition and application of a particular kind of shamanistic power, weather control.”

The discovery of this coincidence, needless to say, kind of blew me away.

How had the most well-funded and significant rainmaking research operation in world history taken place—unbeknownst to the US military—at the exact same location as the most persistent and sacred rainmaking ritual site on earth, with artwork dating as far back as 16,000 years?

What did such a coincidence mean? How was it possible? How had no one noticed?

“Any fact becomes important when it’s connected to another.” —Umberto Eco

And why me?—especially after all the unpromising stops and starts I covered across my previous two posts. For the avaricious nonfiction writer accustomed to navel-gazing his way toward ever more forced epiphanies, this China Lake coincidence hidden away high in the Mojave Desert felt like a serious, powerful swerve. All of a sudden, quite unlike those Starbucks scenes populating my stillborn suburban memoir, it seemed like I had a major story on my hands.

But that story was not about coincidence.

No. I think I had the intimation even then, while I was still generally able to ignore the severity of my drinking, that I’d much rather die of cirrhosis than dive into anything as asinine as coincidence. The research for the actual book itself was difficult and improbable enough without wasting even a weekend on such a worthless rabbit hole. Further, far beyond whatever polluting fumes of positivity one might huff down there among the dark warrens of New Age woo-woo, there was also the simple fact of being seen or even suspected of sniffing around that Nag Champa scented hole.

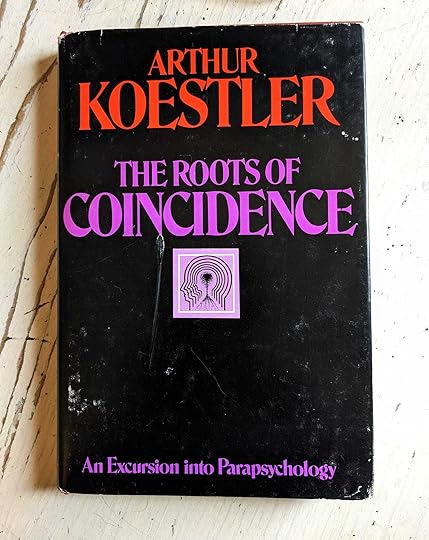

woo-woo /ˈwo͞oˌwo͞o/ (1980s) — Used to mock beliefs associated with the likes of New Age culture. Probably in imitation of a wailing sound traditionally attributed to ghosts & humorously associated w/ mysticism, the supernatural.A surefire way to abort your own inchoate writing career is to express an untoward interest in the ineffable. Serious writing rests in precision. If you’re going to blow a bunch of hot air, there better be a dart out front and a tangible target. It’s not enough to give your book a cover like a vintage vampire novel, all black and foreboding, the text set in a type sharp enough to bite—as Arthur Koestler chose for The Roots of Coincidence (1972), a book I’d seen on display at the Iowa City public library during Halloween season, only days after digging up that rainmaking connection. The thought of peeling it open filled me with fear. Pages upon pages of hopeful paranormal imprecision. An infinite regression into to wish-fulfilling superstition. I had enough ahead of me trying to write seriously and respectfully of Native American shamanism, its spirit helpers, trance states and vagina dentata without entertaining the cuckoo notion of Jungian synchronicity, to say nothing of Paul Kammerer’s absurd seriality (even if Albert Einstein himself had called the latter idea “interesting, and by no means absurd.”) I saw myself splayed out beneath such misty concepts, a baby lying supine and wide-eyed, bewitched by the blooming buzzing confusion twirling over its crib until, summoning not a single informative sentence, I eventually starved to death, a fate already reserved for me as a writer—But at least let me die on my feet! (Nowadays, thankfully, due to the pain of several herniated discs in my lower back, I mostly write while standing.)

“We—our primitive forebears—once regarded things as real possibilities… Today we no longer believe in them, having surmounted such modes of thought. Yet we do not feel entirely secure in these new convictions; the old ones live on in us, on the lookout for confirmation.” —Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny”

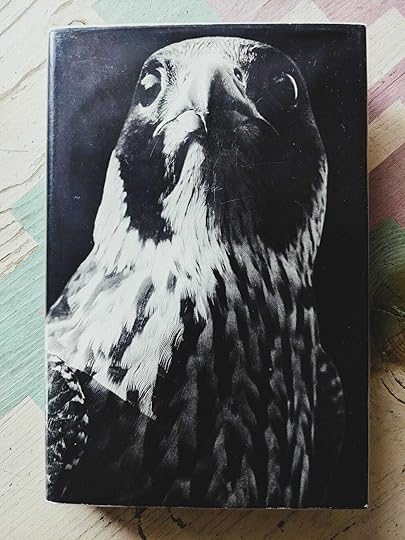

My recently acquired first-edition copy

My recently acquired first-edition copy I knew my dignity and future middling success depended first on not trying to make anything too remarkable out of that rainmaking coincidence. As some kind of ‘secular intellectual,’ I had long ago steeled myself against the lure of such secret significances. Nor was I any kind of infirm alcoholic imbecile, not yet. I had not fully replaced food with a steady diet of whisky and New Age woo. I could still put two and two together—although my calculus career climaxed around there. That was why I’d studied statistics in both high school and college; it was the easiest way to cover core and breadth requirements. And it was as a freshman at Berkeley that I first read the famous paper by Diaconis and Mosteller, “Methods for Studying Coincidences,” published by the American Statistical Association.

“We are swimming in an ocean of coincidence,” Diaconis and Mosteller write.“They delight, confound, and amaze us. They are disturbing and annoying. Coincidences can point to new discoveries. They can alter the course of our lives… When such events occur, they are often noted and recorded. If they happen to us or someone we know, it is hard to escape that spooky feeling.”

Good luck with your research

Good luck with your researchI knew that spooky feeling I found in that coincidence of Native American shamanism and classified military research did not imply the existence of anything paranormal or supernatural. No miracle, no magic or mystery—no synchronicity, seriality, panpsychism or paradigm-imploding physics was required to account for any crazy, weird coincidence. As Diaconis and Mosteller put it in 1989:

“The point is that truly rare events, say events that occur only once in a million… are bound to be plentiful in a population of 250 million people. If a coincidence occurs to one person in a million each day, then we expect 250 occurrences a day and close to 100,000 such occurrences a year. Going from a year to a lifetime and from the population of the United States to that of the world (5 billion at this writing), we can be absolutely sure that we will see incredibly remarkable events.”

And yet, for all that good clean thinking, something strange got started with that China Lake research. Something that’s stuck to me and proven to be a far harder hitchhiker to eject than ethanol. I caught it in that glimmer of the uncanny that shone through my dying Dell laptop that horrifically hungover morning I covered in a previous post, in that wave of chills I found at the far shore of that fateful Google search, and that strange fugue that seemed to consume the afternoons as I hit upon one impossible fact after another.

It was as though something bigger than myself, my cynicism, education, my sense of right and wrong, the possible and the impossible was moving in upon my existence, advancing in from elsewhere, from outside, beyond the fence line of my rational mind, and the uncanny chord it struck as it slipped in lingered on, rattling like a strand of broken barbed wire at the back of my brain, a tapping sound particularly worrisome at night when it brought to mind that opening, the unhappy gap in the calm and measured square of level intellect.

Of course, I could and did dismiss this line of thought. Constantly. All throughout the autumn and spring of 2013 and 2014, I reminded myself there was nothing remarkable to that military/rock art coincidence. Nothing special beyond the routine operation of statistics. It was just something random to celebrate and embrace. The Law of Large Numbers had dropped a fascinating statistical freak into the lap of my nascent nonfiction writing career.

“No coincidence, no story,” so says the ancient Chinese proverb.

All I could do was grab hold of it and be grateful.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Joan Didion wrote in The White Album. And if in the back of my mind that eerie feeling endured, that suspicion that maybe there was something more happening than mere random chance, that unease was entirely natural, inevitable, in fact—a minor failing without which we could not live.

“The brain is a belief engine,” the renowned skeptical author Michael Shermer writes. “We can’t help believing… Our brains evolved to connect the dots of our world into meaningful patterns that explain why things happen.” We automatically detect meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless data. Shermer calls this automatic cognitive action patternicity and it gives rise to agenticity, i.e. “the tendency to infuse patterns with meaning, intention, and agency.” We evolved over millennia to detect such patterns, to piece together data points into stories that at times assist our survival by giving us meaning and, more fundamentally, keeping us off the menu. Bet there’s a monster behind those crackling branches and you’re wrong, not much is lost. But imagine no agent is present—no ghost or demon, boogie man or bear—and you might find yourself giving calories to a Kodiak grizzly.

But it hardly follows that all the patterns we perceive point to the presence of something meaningful, important, or real.

In fact, psychologists coined a term to capture such rampant, runaway pattern detection—apophenia. An apophany is the dark side to the desired epiphany. A person experiencing apophenia finds an excess of meaning everywhere, over-interpreting events and connections, like an over-Adderall-prescribed English major reading Mrs. Dalloway for the first time; their discoveries do not offer any insight or knowledge into the nature of literature, reality, or the world’s interconnectedness. On the contrary—they’re just cracked out, or fucking crazy.

Apophenia is “a process of repetitively and monotonously experiencing abnormal meanings in the entire surrounding experiential field,” wrote Klaus Conrad, the German psychiatrist who coined the term in 1958. Conrad is most remembered for identifying the prodromal “delusional mood” or “atmosphere.” (He knew it from experience as a former Nazi party member.) According to the National Institute for Health, in Conrad’s stage model, the atmosphere may “last for days, months, or even years. During this period, the patient experiences an increasingly oppressive tension, ‘a feeling of nonfinality’ or expectation. The individual describes that something is ‘in the air’ but is unable to say what has changed.”

“The Archangel Michael wants me to blow up California’s EDD headquarters.”

“The Archangel Michael wants me to blow up California’s EDD headquarters.”The situation in the air, of course, for Klaus Conrad’s increasingly paranoid, grandiose, and magical-thinking patients was… psychic meltdown.

“Nevertheless, the subject does not attribute the changes to his/her own state but externalizes them to some, yet to be understood process in the world… The delusions appear suddenly as an ‘aha experience’ concerning what had been perplexing… At the aha-moment, the patient is unable to shift the ‘frame of reference’ to consider the experience from any other perspective than the current one... Then, ‘everything becomes conspicuously salient…’ The universe is experienced as ‘revolving’ around the self…”

A feeling of expectation… Something in the air… A peculiar atmosphere… And then…

Aha!Yeah. Fuck that. I’d still rather boof 14 bottles of Grey Goose then wander off into that web of diseased meaning, no matter how warm or reassuring its weave. And it was armed with a healthy fear of schizophrenia, lazy lyric essay, and a lust for evolutionary reductionism that I was able to convince myself that, regarding my coincidence, rather than feeling spooked, I was afraid of getting scooped.

“You have to swear to God you won’t tell anybody,” I’d tell people before telling them what my book was about. “I’m worried someone might steal my discovery.”

But that discovery, that coincidence—so I kept reminding myself—it was the springboard, not the core. The mere catalyst for my story. A story not concerned with coincidence per se but rather humanity’s continuous desire to assert some godly control over the weather, and now, the global climate.

And yet, still, while that coincidence was not the essence, it had to be protected.

No coincidence, no story.

“And so we build,” the writer W.G. Sebald once put it. “I hope it’s not too obtrusive,” he said in the same interview, referring to the central position of coincidence in all his weird nonfictions. “We somehow need to make sense of our nonsensical existence. And so you meet somebody who has the same birthday—the odds are one to 365, not actually all that amazing. But if you like the person, then immediately this takes on major significance. [Audience laughter.] And so we build. I think all our philosophical systems, all our systems of creed, all our constructions, even the technological ones, are built in that way, in order to make some sort of sense, which there isn’t, as we all know.”

“Writing is about discovering things hitherto unseen. Otherwise there’s no point to the process.” —W.G. Sebald

Yes. It was just a coincidence. Nothing special beyond a stroke of good luck. Grab it, enjoy it, go… Be brave. Build. But my wall of measured skepticism—surprise, surprise—would often crack again. It was usually in a bar at night in Iowa City after confessing what I was constructing, that book that had me holed up all day in my tiny a-frame cabin, a termite-infested fire trap from which I’d emerge some evenings in a state of visible euphoria, an atmosphere that was often infectious and always annoying to those that encountered me. It was obvious that I was working on something.

“But how did you figure all this out?” my interlocuter would ask. “Like, how’d you even start building this thing? Was there, like, one thing you stumbled upon?”

“There had been a sign,” I would say, sounding thoroughly insane.

“A sign?”

And it was in the process of thinking through the actual origins of the book, retracing the steps that had led me to ever stumble on that coincidence that the eerie feeling would again well up within me, a cold shadow creeping over the fence line of my rational mind.

“Our ‘normal’ consciousness is circumscribed for adaptation to our external earthly environment, but the fence is weak in spots, and fitful influences from beyond leak in, showing the otherwise unverifiable common connexion.” —William James

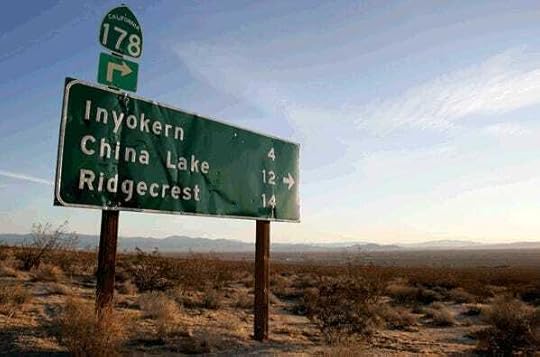

“There was a sign.”

Which was true. There had been a sign. And before their puzzled expression of my drinking partner, whoever they happened to be that night, I’d explain that the sign hadn’t come from any god or creator. More likely a small Caltrans crew had raised it over the creosote and broken beer glass back in the 1990s, when presidential elections still felt like Coke vs. Pepsi and Friends was on TV.

“It was just a random sign.”

And I’d explain how there was never anything to suggest it might point toward some hidden, deeper design. Nothing made it inherently more interesting than any other roadside wreckage or worthless place name devoid of memory or meaning littering the long road from San Diego to Lone Pine. Yet somehow that arrow, among the many thousands pointing a plausible path to nowhere throughout 300 miles of open road, somehow it alone—from my teens and onward into my twenties, every time I drove through that desert—jabbed some subliminal scrap of significance into my skull, pushing through some secret porous boundary surviving somewhere at the back of me, so that each time I perked up, paid attention, and pondered… What?

What about that arrow pricked me so? There was no pattern to perceive. Nothing peculiar to build upon, as I’ve pointed out previously. No. Peering past the tip of that solitary arrow, there was only ever the monotony of sage and heat haze, and given the murderous aura of the ghost town dying in its vicinity—Red Mountain, population 19—the idea of actually exiting and digging into whatever lay down there beyond the bend brought to mind little more than a vision of one’s body rotting face down in a ditch. A dead end.

Red Mountain, CA

Red Mountain, CABut not one made of mystery, but rather misery, methamphetamines, failed dreams. No different on its face from any other inauspicious juncture dotting the Mojave, that limitless junkyard baking forever beyond the backyard of Los Angeles; that sign just one more item of detritus slowly buckling under the desert’s baffling glare.

“Hence, I never took that turnout,” I’d tell my interlocuter, ordering another $2 Lacrosse Lager before going on to explain how strange it was, then, after ten years of procrastination before all internet search engines, that a quick grad school glance at Google completed six months prior, in the spring of 2013, confirmed my intuition.

There was, indeed, a lethal entity lurking at the end of that lonely road.

Far from a necrophiliac hermit hellbent on papering the walls of his carbarn with rolls of human skin, what was hiding beyond the arrow of that bent-up Caltrans sign was actually America’s best and brightest minds, the engineers, executives, and generals who had ordered and designed, envisioned and delivered the most destructive weapons on earth. From the dreaded Hellfire missile to the revolutionary AIM-9 Sidewinder, the world’s first operational air-to-air heatseeking missile, and the AGM-62 Walleye, the first television-guided smart bomb, built to carry a W72 nuclear warhead, not to mention the military cloud seeding applications pioneered by the elusive geophysicist, Dr. Pierre Saint Amand.

“We regard the weather as a weapon. Anything one can use to get his way is a weapon and the weather is as good a one as any.” —Dr. Pierre Saint Amand

Earlier, the base had built the fuses for the bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Millions of people the world over had been reduced to pulp and cinders as a result of China Lake’s pioneering spirit of unhappy innovation.

Oddly enough, then, that green Caltrans sign did point toward dark designs.

Had they amounted to nothing more than smart bombs, barbed wire fences, and billions in black budget defense spending, I never would have begun to write China Lake nor launched this embarrassing blog, to say nothing of having begun a failed book project about the nuclear meltdown at Santa Susana—a book I am certainly not salvaging now as I take so long to tell you just why it won’t die and what makes it so… weird wyrd and eerily connected to China Lake, so much so it can only be called a sequel.

But it wasn’t just bombs at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake.

There were big horns too. Hundreds of thousands of sheep carved in one finite isolated location across millennia. More petroglyphs here in one narrow lava canyon than anywhere else in the Western Hemisphere… And it was generally around this time, back in Iowa, in the bars at night, after tabulating all the terrible improbabilities, that I’d lose my fear of being scooped and begin again to feel genuinely spooked.

Renegade Canyon (Little Petroglyph Canyon), Coso Range. Photo by Author.

Renegade Canyon (Little Petroglyph Canyon), Coso Range. Photo by Author. “We tell ourselves stories in order to live… Or at least we do for a while. I am talking here about a time when I began to doubt the premises of all the stories I had ever told myself…” —Joan Didion

How had the most well-funded rainmaking research operation in world history taken place at the exact same location as the most persistent and sacred rainmaking ritual site on earth? Again, what could such a coincidence mean? How was it possible? How had no one else noticed? And why me?

How, of all the thousands of signs and towns, strip malls and historical markers one might cross paths with and plan to research maybe one day between San Diego and the eastern Sierra Nevada, how had my mind made something of this one arbitrary nonsensical road sign? If one were looking for something to write about in Southern California beyond, say, those sad suburban memoirs I kept scribbling about that time my dad dropped me off at Starbucks and never called me back and I never saw him again, one would have been at a loss to land upon such an utterly unknown treasure trove of eerie epic shit.

It didn’t make any sense.

And what was most upsetting, most frightening from the standpoint of my sanity—that coincidence gave me something almost akin to hope.

That hope, however, was not something I carried to Ken Caldeira at Stanford. It was not something I ever bothered to tell anyone directly—not even really myself. It was a bridge too far. Totally taboo. Career killing. An absurd and unseemly Nag Champa scented hole. To nowhere. A dead end. Unsexy. A heresy. It was as the critic Victoria Nelson wrote in The Secret Life of Puppets (Harvard University Press, 2002), a book that’s been receiving renewed attention:

“The greatest taboo among serious intellectuals of the century just behind us, in fact, proved to be none of the ‘transgressions’ itemized by postmodern thinkers: It was, rather, the heresy of challenging a materialist worldview.”

Maybe there was something more out there? Something beyond New Age woo-woo, the Law of Large Numbers, and the ape brain’s paranoid patternicity? Maybe, I wondered—midway through writing a book about the coming climate apocalypse—just maybe…

Maybe there was something more frightening and exciting afoot than humanity’s inexorable march toward oblivion?

Looking back now, I can see that at a certain point, unconsciously, I had assigned Stanford’s Ken Caldeira the role of final arbiter. That is why I keep coming back to the poor man across, what, three, four posts now? Caldeira was the person to consult. Ken, the brilliant Stanford atmospheric scientist. The genius who did research for Bill Gates. Ken the gatekeeper, guardian of the planet, the sole person studying solar geoengineering who seemed, to me, somehow trustworthy. He was a kind of shaman, or a medieval magus, the wizard who would look long into the crystal ball of his computer model and tell us whether or not it was safe to turn the sky white, whether we might save ourselves if we shut out the stars.

Ken would decide whether there was something weird out there, a wayward force operative in all this awful coincidence.

Ken. O Ken! How I hate having typed this nice man’s name so many times. I just added up the numbers. It pops up 69 times across these pages. It does feel a little weird, this repetition, wyrd weird in the colloquial non-Shakespearean JD-Vancian sense of the term, as in deviant, gross, “evincing abnormal interest.” And indeed, if Ken Caldeira has a Google Alert set for his name, as I do (it last pinged sometime in September 2017), he must imagine some boiling caldera of hate foaming up from the basement of some conspiracy blog staffed by a pimpled and friendless aspie with a fetish for couches and trash fires who can’t stop alliterating and relitigating the gruesome injustice of his first book’s gross sales.

I wouldn’t hold that interpretation against him.

Perhaps, as a routine precaution, he’s already forwarded my babbling acid onward to the FBI. Caldeira, if you recall, alongside Harvard’s David Keith, was one of the most death-threatened scientists on earth—at least years ago, when I was lurking all over the YouTubes, pressing the keys, punching my way to the finish line of that first book.

But I mean the man no harm. Quite the opposite, in fact. Truth be told, I owe him a debt of gratitude. It was Ken, the brilliant atmospheric scientist, who saved me, I think, from that “atmosphere” that portends the dreaded onset of apophenia.

It was Ken who canceled all my untoward interest in coincidence.

Ken! O Kenneth! If anyone was simultaneously rational, materialistic, staid and sane, yet open to the supernatural, its interventions, the heretical, taboo, and transgressive, it had to be Ken Caldeira, the scientist researching how to ‘safely’ block out the sun. If ever there was a researcher in need of hope, and maybe looking for something more to learn, it had to be him.

It was Ken, after all, who had described his research as an expression of despair. That was why I trusted him—depression is dependable. “For most, researching ‘geoengineering’ is an expression of despair at the fact that others are unwilling to do the hard work of reducing emissions.”

O Kenneth!

O Kenneth!When I went to see him, I too was facing an impasse. I had about 140 pages of writing behind me—halfway through the book I figured. I didn’t know my next move. But I had the sense that whichever way I turned, it would take me to the end.

I needed another sign, I thought. I would let Ken Caldeira decide.

If when I described that rainmaking coincidence, I saw a break in his body language, a brief pause as he scratched the arm hair behind his wristwatch, and peering off toward some pale contrail curling beyond the Berkeley hills, he muttered the word, “Weird…” I would turn toward an ending that left open a possibility of hope. Perhaps there really was something at the roots of my coincidence, something ‘interesting, and by no means absurd.’ Some agency operating in our world beyond the predictable grinding myopia of humankind’s short-term self-interest.

If on the other hand, Ken just checked the time, turned back to his salad, and went on stabbing at the kale, I would proceed straight to the finish line of what felt like a perfect ending—pen something savvy and smart, world-weary and wise, hopeless and ‘post-modern’ (that phrase no one could quite explain in college and yet would signify, somehow, one’s admission into the rarefied heights of intellectual hipdom). I would not touch anything taboo, abandon that phantom terrain, ditch the whole uncanny raft of coincidence like a wagon in the desert, food for the rats and moths and wind.

I had no expectation, obviously, of the eminent scientist declaring the definitive overthrow of the dominant, materialist paradigm. I was looking for something subtle. A sign. A scratch at the wristwatch, a faraway gaze… “Weird” was then all he had to say and I’d drive to the nearest cafe. “Weird”—that word with which we wipe away all the perverse potency of a fresh anomaly. “Weird”—when something doesn’t fit, seeps in from outside, unwanted, wayward, violating not so much what we expect as what we demand each day to keep a primal dread at bay. “Weird.”

Twinkly eyed talk of coincidence is the kind of dogshit that gets you canceled in serious academic circles. But you are allowed the one tattered old term… “Weird.”

That word was the sign. I would let Ken decide.

Ken, the brilliant Stanford atmospheric scientist. Ken would say if I was losing my way, or if this odd atmosphere I carried might signify anything more than apophenia. I awaited that Aha! moment as we crossed the Stanford campus. And everything became conspicuously salient. And as he stared ahead in thoughtful professor pose, his hands clasped behind his back, I couldn’t help thinking—as I wrote before—that he looked like a prisoner in handcuffs.

“Postmodern irony and cynicism’s become an end in itself, a measure of hip sophistication and literary savvy. Few artists dare to try to talk about ways of working toward redeeming what’s wrong, because they’ll look sentimental and naive to all the weary ironists. Irony’s gone from liberating to enslaving.” —David Foster Wallace

But Ken—captive of despair—paradoxically, he freed me. The supremely death-threatened genius, Bill Gates’s own climate advisor, he spared me my own dead end. Without him I might have been discovered lying face down in a ditch beyond the arrow of that green Caltrans sign erected when Friends was still on TV, and Twin Peaks, back before David Foster Wallace offed himself. Yes, thanks to Ken I never did investigate those dark designs. It was Ken, recall, who utterly dismissed anything remotely interesting in that rainmaking coincidence.

“Is there anything more to it than irony?” he asked me.

And for that I was grateful. In fact, it was what I wanted—why I had sought him out in the first place, assigned him, somehow, the role of final arbiter. There was simply no way such a staid and eminent scientist would consider anything so preposterous.