Gerry Adams's Blog, page 25

August 29, 2020

WITNESS TREES.

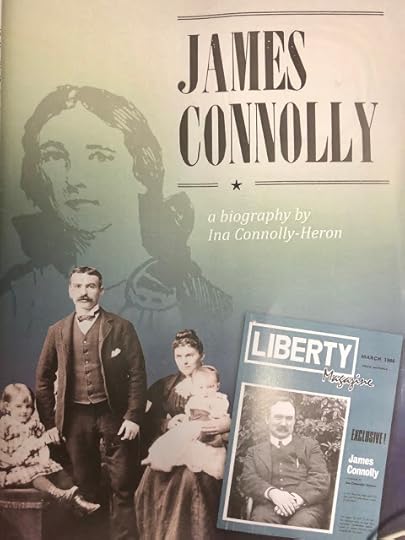

I used to have an old hard backed copy of Nora Connolly O’Brien’s; ‘Portrait Of A Rebel Father’. This wonderful account of James Connolly’s life, as recalled by his daughter, is a must read for followers of the great man. I foolishly lent my copy to a comrade and that is the last I saw of it. But that’s another story.

Áras UÍ Chonghaile has an edition in their wonderful library. If you want to know more about James why not call into Áras Uí Chonghaile – the James Connolly Centre, 374 Falls Road – a few hundred metres from Connolly’s home. It’s an amazing account of Connolly’s life and times and death.

In my copy of ‘Portrait Of A Rebel Father’ - the one that was stolen from me - there is a photo of some of the Connolly children outside their family home at Nos 1 Glenalina Terrace opposite the City Cemetery on the Falls Road. They moved there from Dublin in May 1911. Three of the six Connolly children can be seen standing outside their front door beside a young tree. Sadly, the tree outside the Connolly home is no longer there but the others are. Including two outside Áras Ui Chonghaile.

In a biography of her father another of Connolly’s daughters Ina Connolly -Heron recalls the family arriving in Belfast where her father was taking up a position as Belfast Branch Secretary and Ulster Organiser of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union.

Ina writes: ‘Our destination was near the City Cemetery ... We were very pleased with our surroundings: big green fields lay at the backdoor – bog meadows, they were called.’

For years I believed that the trees that had been planted along that stretch of the Falls Road are the same ones that are there today. Regular readers will know that this column doesn’t spoof. I liked the notion that these trees would have seen Connolly walking along the road as he went about his revolutionary work. So a few weeks ago I asked my good friend and lifelong leader Councillor Seanna Walsh to make enquiries of Belfast City Hall.

For years I believed that the trees that had been planted along that stretch of the Falls Road are the same ones that are there today. Regular readers will know that this column doesn’t spoof. I liked the notion that these trees would have seen Connolly walking along the road as he went about his revolutionary work. So a few weeks ago I asked my good friend and lifelong leader Councillor Seanna Walsh to make enquiries of Belfast City Hall.

He did so with his usual diligence. Back came the word. ‘These trees were planted in 1903’. So my hunch about the trees along that stretch of the Falls Road is vindicated. I feel like Detective Colombo successfully concluding an investigation. No more will I be accused of being like Inspector Clouseau by Ted and some of my less informed detractors when I credit these trees as silent noble witness to James Connolly’s life in our community.

These trees would have seen him and his wife Lillie and their six children taking up residence in Glenalina Terrace. They would have seen all the comings and goings in the build up to the Rising. Did Seán Mac Diarmada visit there when he lived in Belfast? Or the Countess? She and Bulmer Hobson founded Na Fianna hÉireann and rented a hall in the Rock Streets across from the Connolly residence. Did Pearse ever call when he was in Belfast? Or Roger Casement? Old Tom Clarke? Winifred Carney would certainly have been a frequent visitor? The trees would have watched Connolly departing for Dublin in 1916. If only trees could talk.

They have been observers of many events in their lifetimes. From the Rising to Partition to the Hungerstrikes, to the Good Friday Agreement and all the thousands of marches and rallies and demos and funerals and shootings and explosions and Féile An Phobail carnivals. All the good, sad, angry, happy, proud, confusing events of their time. That’s what Witness Trees do. They stand witness and provide connections to times outside of our mere human lifespan.

For example a Dutch artist, Theodore Maas, was present at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. 2000 died that day. Maas captured the carnage in a series of drawings. In the middle of the battlefield and recorded by Maas stands a majestic oak tree. It is there yet. It’s called the Mighty Battle Oak. It is over 500 years old.

The oldest tree in Ireland is in County Fermanagh. It is a yew. Like another Yew in Maynooth - the Silken Thomas tree- it is over 700 years old. An oak tree in Belvoir Park Forest is 500 years old. It was here when Belfast was a wee village.

We Irish have a long relationship with trees. Six thousand years ago native woods of oak, elm, birch, ash, pine, hazel and alders were plentiful. By 1900 only one percent survived the ravages of our colonisers.

Native trees are embedded in our culture. The ancient Irish lived in harmony with nature. Trees were of great spiritual value to them. They were sacred. Many were used as protection against evil. Others are associated with holy places. Or fairies. Holy wells. Thirteen thousand Irish townland names mention trees. Many of these ancient pagan groves were colonised by the Christians. But their old names persist. Sometimes in a combination of the Irish ‘Cill’ – Church - with tree names.

So our Falls Road Witness Trees are not on their own. They are survivors. Incidentally, apart from the tree outside 1 Glenalina Terrace I have a vague recollection that at least one of other trees close to Saint John’s Chapel was cut down in an act of subversive stupidity some time ago. And finally all of this came into my head recently when I finished a new book of short stories to be published next year. Its name is The Witness Tree. More of that anon.

In the meantime if you pass our Falls Road Witness Trees salute them. They knew James Connolly. And he knew them.

August 6, 2020

Remembering John Hume

The death of John Hume is a huge loss for the Irish people but especially for his wife, his life partner and confidant, Pat and their family. My thoughts and prayers are with them.

During the years of conflict one of the tactics deployed by the British and Irish governments was that no one should talk to republicans. This British-led strategy was premised on an approach, developed through years of bitter colonial wars, that the objective must always be to defeat the enemy. For successive British governments that meant the use of extensive repressive legislation; a compliant judiciary and media; torture; shoot-to-kill actions; counter-gangs (UDA and UVF); and the demonising of that enemy. The Irish political and media establishment – with a very few honourable exceptions - bought into this Self serving stupidity.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s I publicly and repeatedly said that the politics of condemnation would achieve nothing. What was needed was the creation of an alternative unarmed strategy. Republicans were thinking, intelligent people who believed that armed struggle, in the context that existed then, was the only means by which real political change could be achieved. If that was to change then a realistic alternative was needed. Establish that and other possibilities became feasible. That was the essence of the argument I was putting.

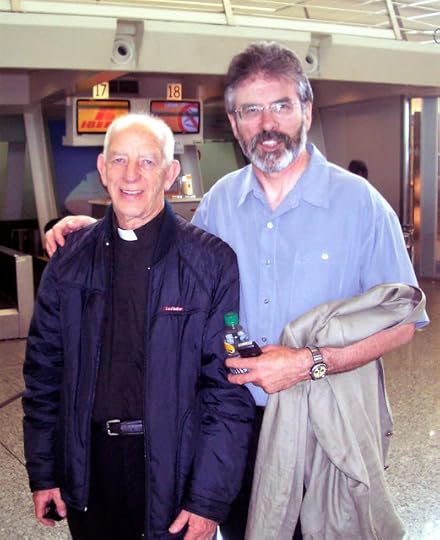

As a result of conversations I was having at the time with Fr. Des Wilson and Fr. Alex Reid we tried to engage with the Catholic Hierarchy, the governments, and other parties to tease out what this alternative process might look like.

Regrettably, with the exception of Archbishop, later Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich, they weren’t for talking. The establishments were committed to their approach which was to defeat republicans. Sinn Féin’s early electoral successes in the 1982 Assembly election, in the 1983 Westminster election and in the local government elections of 1985 only served to reinforce this inflexible stance by the political and media establishments. Anything less than the defeat of Irish republicanism was anathema to them. So was dialogue.

In an attempt to open up a debate Fr. Reid wrote a paper in July 1985 in which he sought to identify the military and political conditions in which those republicans who were engaged in armed struggle would examine an alternative. His focus was on getting agreement between the nationalist parties around a united policy of aims and methods for solving the conflict.

He laboriously handwrote copies of this proposal and posted it off. He eventually spoke to the SDLP Deputy Leader Seamus Mallon about meeting with me. At first Mr. Mallon indicated a willingness to consider this but as time passed Fr. Reid suggested to Mallon that he was thinking of approaching John Hume. Mallon told him not to and to give it another few weeks. Meetings that were arranged were then cancelled. The British and Irish governments signed the Anglo-Irish Agreement in November 85 and in Westminster by-elections in early 1986 Seamus Mallon won the Newry and Mourne seat. In March Mr Mallon told the Sagart (Fr. Reid) that he would not meet me.

I bumped into the Sagart in the airport in the Basque country as he returned from his efforts for peace in that place.

This then was the background to the Sagart’s decision to write directly to John Hume on 19 May 1986. In a long letter, he set out his pastoral and moral obligations for writing. He wrote about our conversations and of our commitment to finding an alternative to conflict and gave John a real sense of what that alternative might be.

The Sagart went to and fro between us for a short time and eventually we arranged to meet in September. Our meeting was friendly and constructive. I put to John my belief that we needed to build a broad alliance of nationalist parties, or at least a consensus among us, to press the British into setting aside the 1920 Government of Ireland Act.John phoned Clonard Monastery the next day and he and the Sagart, along with Fr. Seamus Enright and Fr. Reynolds met on 21 May. John told the three priests that he would co-operate with them. He told them that he agreed in principle with their efforts to create a ‘political alternative to armed struggle through the process of dialogue between the parties and especially between Sinn Féin and the SDLP'.I thought it was a good first meeting. While we had different political positions I found John very down to earth and easy to talk to. Both of us agreed to go off and reflect on what had been said. I agreed to relay our discussions back to the IRA and he said he would try to establish whether the British government would be prepared to say the sort of things I had suggested would be helpful. Looking back now I still find it hard to believe that the process of dialogue took as long as it did. That was 1986. It took another 12 years to get to the Good Friday Agreement.

In March 1988 the first of a series of leadership meetings between the SDLP and Sinn Fein took place. While some progress was made there remained significant gaps between us. The talks ended in September. Nonetheless John and I weren’t for giving up. In the midst of atrocities by all sides, and the perpetual political crisis that is the North, John and I continued to talk quietly.

At Easter 1993 the story of our meetings broke in the media. There was a storm of protest, condemnation, and vitriol almost all aimed at John. The Irish and British political and media establishments were outraged by John’s impertinence in breaking the consensus position of refusing to speak to Republicans. Sections of the Dublin based media was especially vitriolic toward John. Their attacks were personal, political and often just abusive. The Independent Group of Newspapers led the charge. Day after day, week after week thousands of words were written about John in the most hurtful, cruel, and spiteful manner.

I know that he found much of this very difficult. He was especially concerned at the impact on his family. But he refused to be put off course.

One of John’s great strengths was his dogged determination to see a thing through. He was convinced, as I was, that we were both very serious and genuine about finding an alternative to armed actions. Our shared objective was to agree a way forward that would see conflict ended for good.

Unlike those who were condemning him John did not live in a bubble divorced from ordinary people. He was a proud son of Derry who was deeply connected with his community in ways that his critics could never be. He knew many republican families – they were his neighbours. Although he fundamentally disagreed with the IRA, and was opposed to their actions, he knew that republicans were not criminals or gangsters but serious people who believed in what they were doing. He and I were trying to find another way forward.

John also faced criticism from within his own party. Eddie McGrady MP once said: “Terrorism will not be defeated by giving Sinn Féin a leg-up from the gutter.” This fitted with the belief by some that he helped Sinn Féin at the cost of the SDLP. None of that is true. The reality is that Sinn Féin was fit for purpose following the Good Friday Agreement. The SDLP without John Hume was not.

Over the 12 years of our conversations, both secret and public, I got to know John well. At his best he had an instinctive affinity for people. Our conversations were never combative. He listened

Singing in the White House

His wife Pat also deserves great credit. She was John’s mainstay, his life partner and constant adviser and supporter. She always made me welcome. Father Alex often told me that Pat was the biggest influence on John and he often talked to her about our process. I thank her for all she has done. Mó comhbhrón lei agus a clann. Agus leis an SDLP.

John’s contribution to Irish politics cannot be underestimated. When others talked endlessly about peace John grasped the challenge and helped make peace happen.

Ar dheis Dé go raibh a Á am dílis.

Speaking to the media after the death of John

Speaking to the media after the death of John

July 31, 2020

‘Lean ar aghaidh’ – ‘Go Ahead’.

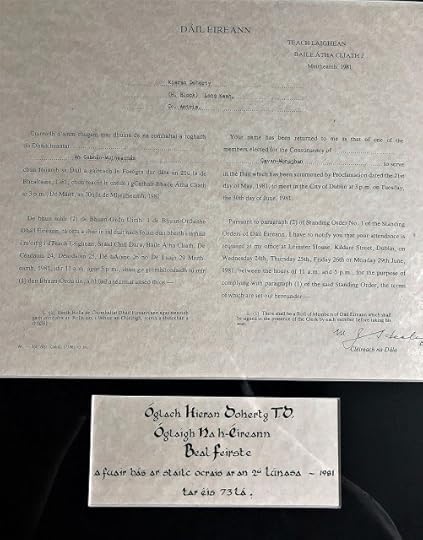

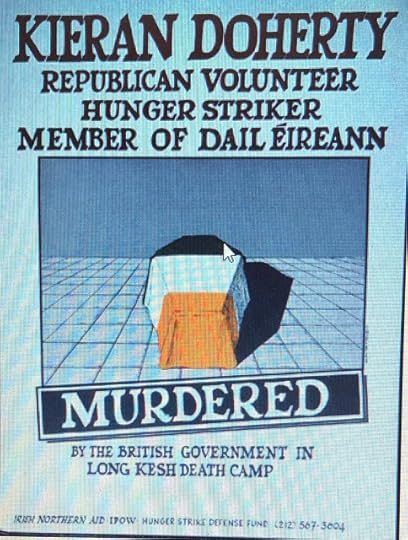

This Sunday, August 2nd, the 2020 National Hunger Strike Commemoration will take place online. Sunday will also be the anniversary of the death on hunger strike of Andersonstown man Kieran Doherty. The national commemoration for the ten H-Block hunger strikers, as well as for Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg, who both died in English prisons, takes place each August. However, like so many other events this year Covid-19 has disrupted long established commemorations and organizers have had to go online.

I have watched all of the online events and participated in many of them. The organizers are to be commended for their efforts and their ingenuity. They have successfully combined music and song, poetry, news footage of the time, and interviews with friends and relatives to create informative, emotional and uplifting productions.

The online events for the hunger strikers have been especially poignant. The memories come flooding back. The Fermanagh South Tyrone by-election and the election of Bobby Sands. His death and funeral. The deaths that followed of Francie Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O’Hara, Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee and Michael Devine. The general election in the South in June 1981 in which Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew were elected as the first TDs of this generation of republicans. The marches, protests, the funerals, and the confrontations with British state forces. The attack on Joe McDonnell’s funeral, the plastic bullet deaths. All against the backdrop of a small number of courageous and amazing human beings, taking on the criminalisation and demonisation policy of the Thatcher government.

Prison struggles have been an important part of the story of Ireland’s long struggle for freedom and independence. From the 1798 Rebellion, to the young Irelanders and Van Dieman’s Land in Australia, the Fenian prisoners, driven mad by horrendous conditions in English prisons in the 1880s, to the 1916 Rising and Kilmainham, and prisons and prison camps in Ireland, England and Wales. The blanket protest of the H-Blocks and Armagh Women’s prison and the resulting 1981 hunger strike, were a watershed moment in this phase of our struggle and of modern Irish history.

Prison struggles have been an important part of the story of Ireland’s long struggle for freedom and independence. From the 1798 Rebellion, to the young Irelanders and Van Dieman’s Land in Australia, the Fenian prisoners, driven mad by horrendous conditions in English prisons in the 1880s, to the 1916 Rising and Kilmainham, and prisons and prison camps in Ireland, England and Wales. The blanket protest of the H-Blocks and Armagh Women’s prison and the resulting 1981 hunger strike, were a watershed moment in this phase of our struggle and of modern Irish history.

Regrettably, there have always been those in the media and political establishment in Ireland who enthusiastically joined the chorus of condemnation of republicans by the British. It served their narrow self-interests. In particular, the use of abusive and sectarian language, of describing political opponents in terms that make them less than human, was used for generations by the Unionist government at Stormont to justify discrimination and repression against nationalists. It was also a fundamental part of the counter-insurgency strategy of successive British and Irish governments to defeat republicanism. British governments in colonial wars after 1945 demonised their opponents to defend the use of concentration camps in Kenya or torture and shoot to kill tactics in Oman, Malaya, Aden, Cyprus and Borneo or the creation of counter-gangs to facilitate collusion between state forces and state sponsored terror groups.

The use of racist language to dehumanise people has been consciously used to excuse and justify slavery, the exploitation of native peoples, of women, and the ill-treatment and abuse of others. The English media of the 19thcentury regularly pictured the Irish as ape-like. One Punch satirist described the Irish who fled to England after the great hunger as ‘a creature manifestly between the gorilla and the negro’ which sometimes ‘sallies forth in states of excitement and attacks civilised human beings that have provoked its fury.’

For centuries the Irish were depicted as brutish, drunkards and stupid. The poverty and destitution, the forced emigration and cyclical famines were blamed on the Irish character, not British colonialism. The recent years of conflict saw British cartoonists and newspapers repeated this racism. In the 1980s one writer in a mainstream British newspaper described the Irish ‘as extremely violent, bloody minded, always fighting, drinking enormous amounts, getting roaring drunk’ and that IRA violence tended to make them ‘look rather like apes – though that’s rather hard luck on the apes.’

Even today there are some in the media, in academia and in the political establishments who believe it is still ok to use degrading and insulting language when describing Sinn Féin and our voters. A column last week in the Irish Times, about the need to detoxify Sinn Féin, and of the party needing to be house trained, is a recent example.

It’s at times like these that the heroism of the hunger strikers and the words and deeds of Bobby Sands, Kieran Doherty and their comrades, and of Mairead Farrell and hundreds of others, shine through.

So, on Sunday evening as you sit down to watch the 2020 National Hunger Strike Commemoration on Facebook, on YouTube and Twitter remember the courage of Kieran Doherty and his comrades.

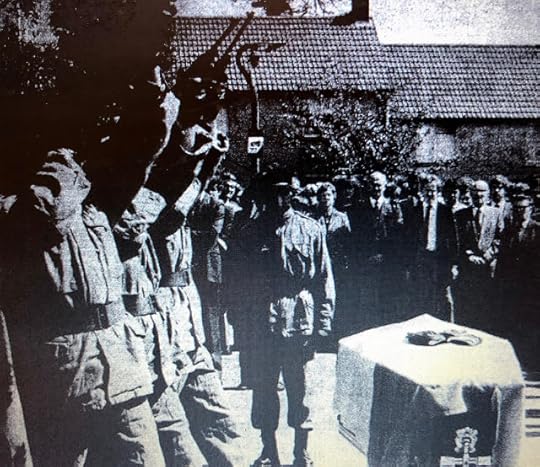

39 years ago at around 7.15 pm on the evening of August 2ndBig Doc died. He had been on hunger strike 73 days. He was just 25 years old. Kieran was first arrested as a 17 year old and interned. He spent seven of the last ten years of his life in prison. Big Doc’s remains arrived at his family home at Commedagh Drive in Andersonstown in the early hours of the following morning. Two days later thousands followed his cortege to the Republican Plot in Milltown Cemetery where he was laid beside Bobby Sands and Joe McDonnell.

39 years ago at around 7.15 pm on the evening of August 2ndBig Doc died. He had been on hunger strike 73 days. He was just 25 years old. Kieran was first arrested as a 17 year old and interned. He spent seven of the last ten years of his life in prison. Big Doc’s remains arrived at his family home at Commedagh Drive in Andersonstown in the early hours of the following morning. Two days later thousands followed his cortege to the Republican Plot in Milltown Cemetery where he was laid beside Bobby Sands and Joe McDonnell.

I knew Big Doc. The last time I met him was a few days before he died. I was visiting the prison hospital to speak to the hunger strikers. After speaking to Tom McElwee and Lorny McKeown, Matt Devlin and others I walked into Big Doc’s cell. He was too weak to join the others. I had known Big Doc on the outside but there in that prison cell he was a shadow of himself.

Doc was propped up on one elbow, his eyes unseeing. He looked massive in his gauntness, as his eyes, fierce in their quiet defiance, scanned my face. I spoke to him quietly and slowly. I sat on the side of the bed.

I told him that he would soon be dead and that if he wanted I would leave the blocks and announce that the hunger strike was over. He paused momentarily, and said: “We haven’t got our five demands and that’s the only way I’m coming off. Too much suffered for too long, too many good men dead. Thatcher can’t break us. Lean ar aghaidh. I’m not a criminal.”

After that we talked quietly for a few minutes. As I left his cell we shook hands, an old internee’s handshake, firm and strong.

“Thanks for coming in”, he said, “I’m glad we had that wee yarn. Tell everyone, all the lads I was asking for them and…”

He continued to grip my hand. “Don’t worry, we’ll get our five demands. We’ll break Thatcher. Lean ar aghaidh... For too long our people have been broken. The Free Staters, the Church, the SDLP. We won’t be broken. We’ll get our five demands. If I’m dead well, the others will have them ... I don’t want to died but that’s up to the Brits. They think they can break us. Well they can’t. Tiocfaidh ár lá.”

Big Doc was right. Thatcher was beaten. The political prisoners won their five demands. And today because of their self-sacrifice and that of countless others, Sinn Féin is the biggest party on the island of Ireland.

We refuse to allow anyone to delegitimise or criminalise the hunger strikers or our struggle.

Kieran Doherty put in well in those final moments before we parted. ‘Lean ar aghaidh’ – Go Ahead.

The Links to the online commemoration are:

www.facebook.com/sinnfein

www.twitter.com/sinnfeinireland

www.sinnfein.ie

www.youtube.com/c/sinnfeinireland

July 24, 2020

Roger Casement Versus The Empire: Statues for Irish Heroes

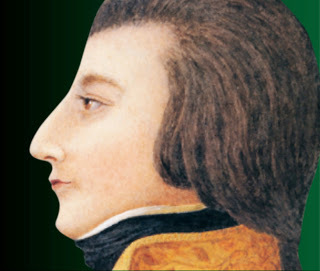

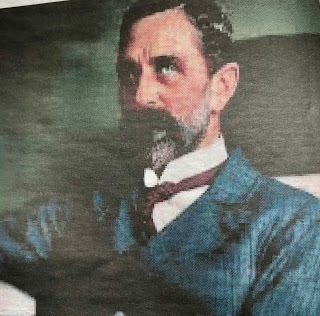

Roger Casement

Belfast has a long and proud tradition of opposition to slavery and colonialism. On 8 July we celebrated the birth in 1770 of Mary Ann McCracken a fierce opponent of slavery. She and her brother Henry Joe McCracken, one of the leaders of the 1798 Rebellion, campaigned against slave ships docking in Belfast port. In her late 80s Mary Ann was still a frequent visitor to Belfast docks where she handed out anti-slavery leaflets to those travelling to the USA where slavery still existed. Thomas McCabe, a United Irishman, from the Antrim Road, was another stalwart who opposed slavery and efforts to set up a slave trading company in Belfast.

In the 1840s escaped slave Frederick Douglass was warmly received when he toured Ireland speaking about his experience of slavery. He visited Belfast and spoke there. Daniel O Connell was a leading opponent of slavery. This aspect of our history is especially relevant today as more and more people across the world speak out against modern slavery and racism.

The Black Lives Matter movement in the USA has led the way on this and there is now an international focus on the role other countries played in the slave trade.

The British Empire, which at its height was the largest in human history, ruthlessly exploited hundreds of millions of people in Africa and India and elsewhere. The Empire had its supporters in Ireland also and that imperialist British legacy is all around us today. It is to be found in partition and the economic, political and human cost of that disaster. But it is also to be found in the symbols and statues and place names which are everywhere.

For example, for the ten years that I was a TD in the Dáil I parked each day in the shadow of a statue to Prince Albert, the consort of the English Queen Victoria. In Belfast there are two bridges named after English Queens. The Queens Bridge was opened in 1849 and is named after Victoria. The Queen Elizabeth Bridge is named after the current holder of that office and was opened in 1966. Interestingly there was a row among unionists in Belfast City Council who wanted to name it after Unionist leader Edward Carson whose statue stands in front of Parliament Buildings at Stormont.

There is the Craigavon Bridge in Derry – named after James Craig, later Viscount Craigavon who was the first Unionist Prime Minister of the North after partition. In Belfast there is Royal Avenue and the Royal Victoria Hospital and countless other thoroughfares named after British Royals or unionist leaders. There is Queens University and the Albert Clock named after Victoria’s other half. Belfast City Council proudly erected statues and stain glass windows within the precincts of the City Hall reflecting this British and Unionist dominance. They also named streets after places associated with Britain’s imperial past. The Sinn Féin office on the Falls Road is at its junction with Sevastopol Street which runs into Odessa Street. Both names associated with the Crimea War. Other places include Bombay Street, the Kashmir Road and Cawnpore Street named after places in India.

As societal, political and demographic changes have taken place there is a greater understanding of the need for places to reflect the entirety of society and not just one section. So, some of this is changing. But it is very slow. In recent years there has been a campaign to use Irish street names and to erect Irish name plates. A statue was erected on the Falls Road to James Connolly, not far from where he and his family lived for several years up to 1916. There are also plans for a statue in the grounds of Belfast City Hall to Winifred Carney, an activist and revolutionary in her own right, who was with Connolly in the GPO.

Plaque at Casement Park

In Dun Laoghaire, outside Dublin a statue is to be erected later this year to Roger Casement who was born in nearby Sandycove in 1864. Historian, activist and author Jim McVeigh has suggested a statue for Casement at the new Casement Park Stadium? I think that’s a good thought.

It would also be fitting in this current climate when the colonial and imperial abuses of the past, especially around slavery, are being confronted. When the European Empires in 1885 carved up Africa between them Belgian King Leopold 11 was allocated two million square kilometers of land to run as his own private fiefdom. His rule, in what is now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, saw ten million and more murdered, and millions more, including children, maimed. Their hands and feet cut off if they failed to obey the orders of his overseers. Leopold tried to keep others out of the region but the stories of torture and slavery and abuse gradually emerged. However, it was the work of Roger Casement which convincingly exposed Leopold’s reign of terror.

Roger Casement was raised in and around Ballymena in County Antrim. He was a member of an Ulster Protestant family, a Knight of the British Empire and a British diplomat. He was also a gaelgeóir who loved the Glens of Antrim. He was proud to be Irish. He was a thinker who took many of the weightiest decisions of his life whilst pacing on Cushendall beach.

Casement was very conscious of the role and history of British involvement in Ireland. He was resolute in his opposition to it and his goal was a free, united and independent Ireland. During his time as a British diplomat he saw at first hand the impact of European Imperialism in Africa and South America. Casement wrote extensively about this.

In 1903 he was asked by the British government to produce a report on the conditions into the region controlled by Leopold. Leopold had established what he called the Congo Free State. He set up the Force Publique, a military body run by white officers whose job it was to ensure that the Congo’s vast wealth and resources were exploited in Leopold’s interests.

Rubber and ivory were the main produces. Indigenous workers were mercilessly exploited. Many died from exhaustion and hunger and disease working on the rubber plantations. Resistance was ruthlessly suppressed. Victims were often whipped used the chicotte, a whip made of sun-dried hippopotamus hide with razor-sharp edges. Most victims were given a hundred lashes. Many died. Those who tried to escape or rebel were hunted down by the Force Publique who cut off the right hand of anyone they killed.

Casement’s expose of the cruelty of Leopold’s activities created an international outcry which led to Leopold being stripped of his control of the Congo.

Later Casement was sent to South America where he investigated the use of slaves and the ill-treatment of local native people by a British rubber company.

It was this record of work as a diplomat and a senior public servant for the British Empire which almost certainly sealed his fate in August 1916. More than any of the other leaders of the Easter Rising Roger Casement was viewed by the British establishment as a traitor to his class and to the Empire. In a fortnights time we will remember the life and courage of Roger Casement who was hanged on 3 August 1916.

It was this record of work as a diplomat and a senior public servant for the British Empire which almost certainly sealed his fate in August 1916. More than any of the other leaders of the Easter Rising Roger Casement was viewed by the British establishment as a traitor to his class and to the Empire. In a fortnights time we will remember the life and courage of Roger Casement who was hanged on 3 August 1916.

The extent to which the British Empire exploited and killed and impoverished hundreds of millions is rarely told, especially by the British media. It is not a version of history taught in schools. But for the scores of nations, including our own, which are still faced with the legacy and challenges of that involvement, the current public challenge to the legacy of slavery and colonialism and Empire is an opportunity to ensure that the real story of the British Empire and Ireland is told and retold. Including those brave souls like Roger Casement and Mary Anne McCracken who stood against it.

July 17, 2020

Partition has to go

There is unanimity of approach among the establishment parties in the Oireachtas when it comes to a referendum on Irish Unity – they are against it. Last week the Taoiseach Micheál Martin ruled out a referendum on a united Ireland because it would be too ‘divisive’. In December the Green Party leader Eamon Ryan dismissed calls for a referendum on the same basis. It would be ‘divisive’. And not to be outdone the then Taoiseach Leo Varadkar claimed that a referendum would be ‘divisive’. Of course, it is partition that is ‘divisive’.

Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and the Green Party assert that now is not the right time for a referendum. They also accuse Sinn Féin of seeking an immediate referendum. They are wrong on both counts.

In 1998 the people of the island of Ireland voted by 2,119,549 to 360,627 to back the Good Friday Agreement. That overwhelming endorsement included voting for the provision within it to hold a referendum on Irish Unity. How can any Irish government and especially a Taoiseach whose party was one of the key architects of that Agreement, now resile from honouring the commitments it helped to shape? The Agreement was not foisted on it. The people of the island of Ireland and the members of Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and of the Green Party voted for the Good Friday Agreement in huge numbers. How far that ambitious Agreement has now fallen in the mind of Micheál Martin who has reduced the goal of a United Ireland to the establishment of a unit in the Taoiseach’s department with the aim of discussing “a shared island”?

I wonder how this unit might work? Can citizens make submissions to it? Will it do meaningful outreach work? Will if organise forums? Will there be consultation processes? This unit is far less than is required to deliver a proper, informed plan for the future. But the onus is on the Taoiseach to make it work not least because he has rejected the Good Friday Agreement at this time.

Micheál Martin like many of his predecessors has engaged in the rhetoric of republicanism and of a United Ireland without doing anything tangible to advance it.

Despite this there has been a growing interest in and a increasing demand for a referendum date. The Dublin establishment parties clearly don’t like this. Be sure that they are very informed of all these developments and no doubt will have focus groups and other political intelligence gathering processes working at full speed.

Unionist parties in the North are also opposed to the referendum. But the desire for a United Ireland is not going away. On the contrary the demand is getting louder. There is consistent opinion poll evidence indicating strong support for a Referendum and for Unity. The group Ireland’s Future has successfully focussed attention on the imperative of a referendum and the necessity of winning that referendum. In addition, the Brexit referendum vote in the North in 2016 witnessed a majority made up of nationalist and unionist voters opting for staying within the EU. And in the last five elections in the North the electoral majority that unionists held since partition has ended. Change is taking place. The electoral certainties of the past are eroding.

The Good Friday Agreement is very clear on the conditions for constitutional change. It makes a specific commitment to a vote on Unity through referendums to be held North and South.

Securing a date for a referendum on Unity is, of course, only a first step. Those of us who are united Irelanders, and who want to end the divisions, economic dislocation, sectarianism, denial of rights and misery caused by partition, also want to win that referendum. That means achieving a YES vote in the North which would by necessity be greater than the current nationalist/republican vote achieved in elections. This is clearly a significant but not insurmountable challenge.

The decision that voters take must be arrived at through a process of conversation, negotiation and agreement. No genuine united Irelander, unlike those who support the union, seeks to impose or dictate any outcome in advance. The objective is to achieve democratic agreement on constitutional change through dialogue while protecting the hard won peace.

This can best be achieved through agreeing a date for a referendum which provides sufficient time to ensure a mature, positive and constructive consideration of what unity means. Sinn Féin is not interested in replaying the folly of the British Brexit referendum in 2016 which provided insufficient time to explore the arguments in favour of or against Brexit.

Fundamental to this is a conversation about the kind of new constitutional arrangements will be needed to provide for the greatest degree of transparency, accountability and protections for all citizens in a United Ireland.

The Good Friday Agreement, for example, already provides one template for protecting the British identity in the New Ireland. It states that if in the future the people of the island of Ireland agree to Irish Unity that, in respect to the North, “the power of the sovereign government with jurisdiction there shall be exercised with rigorous impartiality on behalf of all the people in the diversity of their identities and traditions and shall be founded on the principles of full respect for, and equality of, civil, political, social and cultural rights, of freedom from discrimination for all citizens, and of parity of esteem and of just and equal treatment for the identity, ethos, and aspirations of both communities”.

The Agreement further states that it is the birth right of all the people of the North to “identify themselves and be accepted as Irish or British, or both, as they may so choose, and accordingly confirm that their right to hold both British and Irish citizenship is accepted by both Governments and would not be affected by any future change in the status of Northern Ireland”.

The conversation on a referendum on Unity must also look at issues of reconciliation; governmental structures; the shape of government departments in an all-island context and with an all-island agenda – and from Sinn Féin’s perspective, including a single tier all island health service free at the point of delivery; local government structures; how the New Ireland can effectively deliver equality, civil and human rights, and protect and enhance cultural rights for citizens.

There is already significant evidence that Irish Unity will bring with it substantial economic benefits but how do we shape this in a new shared reality that will benefit all parts of the island?

This is a huge agenda of work which demands planning now. How can we hope to convince anyone of the merits of Unity if we don’t start the preparations and the discussions? The southern establishment parties do not want this – they are comfortable with a status quo which protects their narrow political interests - but the debate around unity has a momentum which cannot be stopped. In the North social, political and demographic changes are already reshaping the old status quo. It’s a slow process but change is taking place. Society on this island and especially political leaders, have to decide whether they lead that change and seek to manage it in the time ahead or oppose it and stick with the failed policies of the past.

A century ago this December the Government of Ireland Act was passed by the British Parliament. 2021 will mark the centenary of the imposition of partition. One hundred years later the failures of partition are self-evident. It’s time for a new beginning. One shaped by the people of this island and not imposed by our nearest neighbour. If political leaders genuinely want to end divisions on this island then partition has to go. Anything less will not work.

July 10, 2020

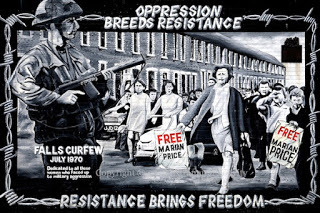

The Falls Curfew.

The Falls Curfew 50 years ago last weekend was a tipping point in modern Irish history.. The previous August (1969) unionist mobs had burned out hundreds of nationalist homes in west and north Belfast, killed and maimed, and forced thousands of families to become refugees living in schools, or with friends and family, strangers who opened their doors for them, or in camps across the border established by the Irish government. The British Army were on the streets. Some nationalists welcomed them as an alternative to the violence of the RUC, B Specials and the unionist gangs. This columnist was not one of those.

Two events changed that perspective. The first was the attack on 27 June 1970 by the UVF and others on the nationalist enclave of the Short Strand in East Belfast. Following the events of August 1969 there had been widespread criticism of the IRAs failure to defend nationalist areas. There was a resulting split in republican ranks over this and political differences about how republicans should respond to the growing crisis in the North.

When armed unionists attacked the Strand the British Army failed to intervene to protect the area. On the contrary newly released British Army logs from the period reveal that British soldiers fired 30 CS gas canisters into the grounds of St. Mathew’s Church which was the target of the unionist attack and the principal defence position of a small number of IRA volunteers and members of the local Citizens’ Defence Committee who were protecting the church.

The successful defence of the Strand was for many people evidence that the (Provisional) IRA was prepared to defend them and it boosted support for and confidence in the IRA. It also reinforced a growing unease among many nationalists that the real purpose of the British Army was to defend the Unionist state and the status quo.

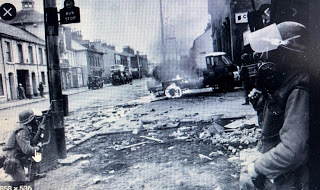

Six days later the reality of the British military as an occupation force was exposed. It began with a search by British soldiers of a house in Balkan Street in the Falls area. Weapons belonging to the Official IRA were uncovered. Local residents were fearful that the actions of the British Army would leave their area defenceless again as it had been the previous August. There was anger. A confrontation between local women and the Black Watch Regiment took place and some young people in Albert Street attacked the soldiers with stones and petrol bombs.

In his book ‘The British Army in Northern Ireland’ British Army Colonel Mike Dewar – who had served in Cyprus and Borneo during the 1960s and in the North in the 1970s - described the approach of the British Army commander General Freeland. Dewar wrote: “Not surprisingly General Freeland was not prepared to let the IRA get away with it. He decided a show of force was needed and that the Falls had to be brought back under control.”

Over three thousand British soldiers, with the full panoply of armoured vehicles, including whippets and tanks, sealed off the Falls area from Divis Flats to the Grosvenor Road to Durham Street. Locked within the densely packed terraced streets several thousand men, women and children came under sustained attack by one of the world’s foremost military powers.

Slingshots were used to fire hundreds of ten inch long canisters of CS gas into the district. Some smashed their way through roofs into homes and the choking clouds of gas penetrated into houses through doors and windows. Hundreds of homes were raided by British troops who broke through doors and windows, destroyed furniture, ripped out fireplaces, and pulled down ceilings and walls.

From helicopters hovering over the rooftops, loudspeakers broadcast a message of war, declaring a curfew which confined the local residents to their homes for an indefinite period. The Brits killed William Burns (54) at the front door of his Falls Road home. They shot another man Patrick Elliman (62) close to his home in Marchioness Street; he died seven days later. They shot and killed an Zbigniew Uglik aged 24 a English/Polish photographer, who was visiting from London, and Charles O’Neill aged 36 who was deliberately crushed to death by an armoured car. Dozens more were injured in the British army assault.

It was for the people of that small area a terrifying experience. The IRA had by now split into the Officials and Provisionals as they were popularly known. The Provisional unit in the Falls was much smaller than the Official unit. Both groups fought back, separately against the British forces. Cumann na mBan volunteers and Na Fianna Éireann were also active. This was the first armed action by D Company and the largest armed engagement between republican and British forces since the Black and Tan war. Thousands of rounds were fired and 300 local people were arrested. To add insult to injury as the streets were emptied of people the British Army brought two Unionist Ministers, John Brooke and William Long, through the area in armoured vehicles.

Accounts of what was happening quickly spread throughout nationalist west Belfast. Máire Drumm decided that something had to be done to help the besieged families. Word was quickly spread that a women’s march was to take place. Their aim was to break the military blockade surrounding the Falls and to bring bread and milk and food to the families trapped in their homes. The march of mothers began in Andersonstown and as it moved down the Falls Road women from Turf Lodge, Ballymurphy, Springhill, the Whiterock, St. James, Beechmount and Iveagh joined it. Many were pushing prams and some had young children by the hand.

Accounts of what was happening quickly spread throughout nationalist west Belfast. Máire Drumm decided that something had to be done to help the besieged families. Word was quickly spread that a women’s march was to take place. Their aim was to break the military blockade surrounding the Falls and to bring bread and milk and food to the families trapped in their homes. The march of mothers began in Andersonstown and as it moved down the Falls Road women from Turf Lodge, Ballymurphy, Springhill, the Whiterock, St. James, Beechmount and Iveagh joined it. Many were pushing prams and some had young children by the hand.

When it finally reached the junction of the Falls Road and the Grosvenor Road where British troops had stretched rolls of barbed wire across the road, there were about three thousand women. Máire Drumm demanded that the wire be removed. The Brits refused and the women pulled it aside. They walked into the area. British soldiers tried in vain to stop them. There is old black and white film which shows hundreds of women proudly and defiantly brushing armed British soldiers aside.

Lily Fitzsimmons from Turf Lodge, later a Sinn Fein Councillor, was one of those who broke the curfew. She described it:

“It was one of the greatest days of women’s solidarity that I can remember. The soldiers didn’t know what hit them they were literally overwhelmed by a sea of determined women. The people who had been imprisoned in their homes for three days were all cheering. You just felt like crying with emotion and many did.”

The Falls Curfew was a turning point. The sight of thousands of women, defiantly and courageously brushing aside heavily armed troops in defence of their community, encouraged increasing numbers of women to get involved in the struggle for freedom.

In addition whatever ambivalence or uncertainty that might have existed among some nationalists about the role of the British Army was now gone. It was clearly an army of military occupation, in support of a unionist regime and British establishment.

In the years that followed the lessons of post Second World War colonial wars fought by Britain in Aden, Kenya and Cyprus, Palestine and Borneo and many other former British colonies were brought to bear in the North of Ireland. Counter-insurgency laws, strategies and the creation of counter-gangs and state collusion with death squads became the norm. The alienation of most nationalists from the Stormont regime and the British state grew apace.

Nowadays the Falls curfew is a memory for some of us, history for others. Much has changed since then but the people of the Falls remain. Unconquered, optimistic and as strong as ever.

July 6, 2020

Leading the Opposition

Last Tuesday republicans buried our friend and comrade Bobby Storey. His death, after a long battle with illness, has left a void in all our lives. Big Bob was a larger than life character. For almost 50 years he was tireless in pursuit of Ireland’s long struggle for freedom. I was honoured and privileged to call him my friend. I want to dedicate this week’s column to his memory.

The ideological and political differences between Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil have now formally ended. On Saturday last, in the National Convention Centre in Dublin, Micheál Martin finally succeeded in becoming Taoiseach with a Fine Gael Tánaiste.

The big spin from all of this is that civil war politics is dead and gone. But the truth is that for most career politicians they have been dead for decades. What we now have from Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael is the same old, same old – with the Green party propping it up. But there is one new significant historical difference. As Micheál Martin takes his place as Taoiseach, and Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil and the Green Party occupy the government benches, they will be faced by an opposition led by Sinn Fein. Mary Lou McDonald TD is now the Leader of the Opposition. This is the first time that position will be held by a woman. It is also the first time since 1927 that the main opposition party is not from Fine Gael or Fianna Fáil. And of course it is the first time that Sinn Féin have held that position.

Change happens slowly. Political systems are especially resistant to reform. In the general election the majority of citizens did not vote for the two conservative parties. There was a general mood, a desire and a vote for change. For a different approach to tackling the problems facing the Irish state than those that have been recycled over the decades by the tweedledee and tweedledum parties of FF and FG.

The establishment parties circled the wagons and fearful of another general election, they refused to speak to Sinn Féin about government formation. Instead they eventually cobbled together a Programme for Government with the Green Party. Of course, they are entitled to do that but their refusal to talk to the Sinn Féin leadership is a sad little undemocratic echo of the way the unionist leaders and British and Irish governments used to behave. Denying Sinn Féin voters their right to be included in talks shows how far the Dublin establishment is prepared to go to minimize and to delay the ongoing process of change across this island, including the movement towards Irish Unity.

Their objective was and is to hold onto power and to continue with their conservative policies tweaked here or there to give the impression of change. They know that they will have to bring in some changes especially on the cost of living crisis affecting the vast majority of people. But they will want to avoid any significant change which would alter the status quo or which would tilt the balance of power towards a greater and more democratic control or creation of public services and the redistribution of wealth.

Their view on economic matters is contaminated by an ideological position based on the belief that market forces rule and that citizens must serve the economy instead of the economy serving citizens. Under this government the housing crisis will not be tackled by the state. Instead it will be a for profit opportunity for developers, vulture capitalists, bankers and big building corporations. Citizens who wish to, will not be able to retire with a pension when they are sixty five. Unless they are politicians or executive types. Our health service will not be a public service. Neither will childcare. Disability rights will have no real legal standing or appropriate funding. There will be no government planning for Irish unity.

The Programme for Government agreed by the three government parties lacks detail or ambition or the big ideas needed to effect real and positive change in people’s lives. It contains no substantive financial costings for the vague policy commitments that it makes. The big issues that exercised the voters in February - homelessness, sky high insurance costs, a lack of new house building, a failure to tackle high rents and evictions, childcare and much more – are not properly addressed. The Covid-19 crisis reinforced a long standing desire for a single tier health system. The Programme for Government opts for reviving the old two tier system.

This ‘new’ government also has no national vision - no all Ireland vision. Micheál Martin and Leo Varadkar are about recasting their twenty six county state. Their Republic. Not the national Republic committed to in The Proclamation. They are about re-entrenching partitionism. This much is evident in the section of the Programme for Government entitled “Mission: “A Shared Island”. Fianna Fáil which describes itself as ‘The Republican Party’ and Fine Gael which boasts it is the ‘United Ireland Party’ produced a document which fails to even mention Irish Unity or a United Ireland or to set out a plan or strategy for advancing this objective.

Moreover, both parties ignore their constitutional obligations on this primary issue. These are spelt out in the Good Friday Agreement which people North and South voted for in the May 1998 referendum. It is also a core part of Article 3 ‘1’ of Bunreacht na hÉireann, which was changed by the GFA, and which states;

“It is the firm will of the Irish nation in harmony and friendship to unite all the people who share the territory of the island of Ireland, in all the diversity of their identities and traditions, recognising that a United Ireland shall be brought about only by peaceful means with the consent of the majority of the people, democratically expressed in both jurisdictions on the island ...”

Sinn Fein and others have urged Martin and Varadkar to take firm actions to fulfil this obligation. These actions require the government by the end of this year to:

Fully implement the Good Friday Agreement Establish a Joint Oireachtas Committee on Irish Unity. Convene an all-island representative Citizen’s Assembly or appropriate Forum to discuss and plan for Irish Unity. Publish a White Paper on Unity. Initiate a process to secure a referendum, North and South, on Irish Unity as committed to in the Good Friday Agreement.It makes sense for the new Irish government to plan for and establish a process of inclusive dialogue, particularly in engaging with unionist concerns. Thus far they have refused to do this.

Consistent speculation that An Taoiseach Micheál Martin would appoint someone from the North to the Seanad proved unfounded. So much for the influence of the SDLP! Instead he used 10 of his 11 seats to appoint Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and Green Party members, including several high profile TDs who lost their seats in the general election. The one welcome exception is Traveller rights activist Eileen Flynn.

Ian Marshall, the first unionist elected to An Seanad in 2018, with Sinn Féin support, says he is ‘astonished’ that no unionist voice was nominated. He quite rightly describes the ‘shared Island’ commitment as a farce.

The reality is that Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil and the Greens in government is not change. But the merging of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael is. The political contours are clearer now. Those who remember the aftermath of the 2016 general election will recall all the talk about ‘new politics.’ It was supposedly the era of a new beginning in southern politics. It never happened. ‘New Politics’ was old politics dressed up in new media spin. It was the same old political parties and same old politicians putting a slightly different gloss on how they did things. It was all a lie. Now ‘new politics’ has been replaced by a formal coalition arrangement.

However, the realigned establishment parties are now challenged by an opposition led by a determined and strengthened Sinn Fein party with a coherent policy agenda and with the political leadership and talent to stand up for working families, border communities, the North and rural Ireland. A Party that is for fairness and for a new direction in Irish politics, with Irish Unity at the heart of our policy platform.

The process of change making is by its nature a challenging process for those of us who want maximum change. We are now into a new more clearly defined phase. We need to consolidate the changes which have happened and which will continue as we set the pace on the journey to the new fair united Ireland. Politics throughout our island are realigning. Isn’t it great to be part of that?

June 26, 2020

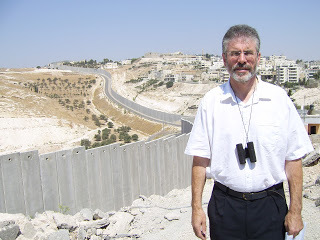

No to Israeli annexation

The Monstrous Separation Wall that stretches for hundreds of kilometres across stolen Palestinian land, cutting Palestinians off from their farms and water sources

The Monstrous Separation Wall that stretches for hundreds of kilometres across stolen Palestinian land, cutting Palestinians off from their farms and water sources

Five times in recent years I have visited Palestine and Israel. I have spoken to leaders and to citizens and human rights advocates on both sides. I have been in Gaza City and the West Bank. I have been in the refugee camps. I have walked along the monstrous separation wall which cuts Palestinian families off from their land and created the biggest ghettoes in the world. All of this is in breach of international law. It is illegal.

Hospital bombed by Israel in Gaza

The plan by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to begin annexing up to 30% of the West Bank beginning next week is also illegal. But the Irish Government refuses to challenge this criminal act in any meaningful way.

If we, the Irish, who have experienced the trauma of colonisation and who understand its consequences don’t stand by the Palestinians who will? It is time for the international community to uphold international law. It is time for the Irish Government do likewise. Muted and meaningless words of condemnation are no longer sufficient.

The Government, and in particular the civil servants who worked on this initiative, are to be commended for winning a seat on the UN Security Council.

Of course, there are many people, including this writer, who are openly sceptical and critical at the lack of reform of the United Nations, and in particular the ability of any of the so-called ‘big five’ - the USA, China, Britain, France and Russia - to veto a resolution going to the Security Council. However, Simon Coveney – if he remains Minister for Foreign Affairs in any FG/FF/GP government – described the extent of his ambition for the Security Council as akin to being a “pebble in the shoe” of the large states.

At a time when Covid-19 is a major pandemic with unparalleled economic consequences for the world; when human rights abuses and the rights of citizens enshrined in UN charters are everywhere under attack; when the numbers of migrants and refugees across the world is spiralling out of all control; and when a US President is attacking the funding for the World Health Organisation and for UNWRA - the UN agency that looks after Palestinian refugees – we need the independent members of the UN Security Council and the Irish government which will now sit there, to be more than a ‘pebble’ in a shoe.

But, lest we forget, this is the same Minister for Foreign Affairs who ensured that the Occupied Territories Bill – which seeks to prevent the Irish state from trading in “the import and sales of goods, services and natural resources originating in illegal settlements in occupied territories” - from being referenced in the putative Programme for Government 2020 agreed between the leaders of Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil and the Greens.

Israel isn’t even mentioned in the Bill. It is aimed at all states with illegal settlements and is about preventing them from profiting from their occupation through trade. Including Israel of course. But Simon said no. Micheál Martin and Eamonn Ryan agreed.

Minister Coveney and his two putative coalition partners in government are prepared to ignore international law and allow Israeli goods and services originating in the occupied territories to be traded in the 26 counties.

In these circumstances what hope is there that an Irish Government of this kind, will vigorously oppose inside and outside of the Security Council the plan by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to annex up to 30% of the West Bank?

Annexation of occupied territory is prohibited under international law since 1945. Emerging out of a world war whose roots where in part to be found in the annexation of land at the end of the First World War and then in the 1930s by the Nazis, the founders of the United Nations had the foresight to outlaw annexation because it inevitably leads to conflict, discrimination and human rights abuses. The UN has on many occasions since the 1967 six day war, which saw Israel occupy the West Bank, Golan Heights and Gaza, affirmed the principle of the “inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory” by force.

Regrettably, the refusal by this and previous Irish governments to oppose the illegal actions of Israel and of its occupation forces, has encouraged and emboldened Netanyahu to believe that now is the time to annex substantial parts of the West Bank. Last April Netanyahu said that he intended annexing Jewish settlements and outposts in the West Bank. These settlements, which are illegal under international law, number over 240 and house almost three quarters of a million Israeli settlers. On the occasions I have visited the region I have seen for myself the extent to which these settlements steal Palestinian land and water rights and mineral resources and are strategically used to separate and control the Palestinian population of the West Bank. As part of this process Palestinians have been killed, their homes demolished, olive groves uprooted and farms destroyed.

Last September the Israeli Prime Minister – encouraged by the support of US President Trump - said that he also planned to annex the Jordan Valley. This makes up almost 30% of the West Bank. Palestinian families living in the Jordan Valley will find it increasingly difficult to stay there. Much of the Valley is already under the control of Israel which bars Palestinians from digging wells or building home extensions, including tents, or irrigation works. From 2009 to 2016 ninety eight per cent of almost three and a half thousand applications for permits for new infrastructure were rejected by the Israeli authorities.

Nor will Palestinians living in the annexed territories be allowed to hold Israeli citizenship. They will be barred from having any say in the state in which they are being forced to live.

The United Nations, the EU and individual states including the Irish state, have failed to defend international law. This failure and Israeli expansionism will usher in an Israeli apartheid state similar in design and intent to the Bantustan scheme created by the White apartheid government in South Africa. Bantu territories were pieces of land – essentially ethnic ghettoes - into which black South Africans were pushed. It was the apartheid regime’s means of control and exploitation in which poverty was widespread and human rights abuses a constant reality.

To its shame the international community has turned a blind eye to Israeli aggression against the Palestinian people. The separation wall, the theft of land and water, the murder of civilians, the use of torture, the victimisation of children, the illegal blockade of the Gaza Strip, the denial of human rights are all products of this. Israel’s strategy and Netanyahu’s plans for annexation have grievously undermined the little remaining hope in the peace process, which for decades now has staggered from crisis to crisis.

But it’s not too late to stop the slide into even greater chaos and conflict. The international community can still make a difference. The Irish government can give a lead. If Minister Coveney wants the Irish government’s two year term on the Security Council to be more meaningful than simply keep a seat warm, and to be more than an occasional irritant to the big states, then he has to stop making excuses for doing nothing. Firstly, the Irish government should commit to passing the Occupied Territories Bill. Secondly, it should officially recognise the Palestinian state as the Oireachtas agreed in December 2014 thereby providing some measure of solidarity and legal protection to the Palestinian people at this dangerous time. And thirdly, the government should introduce a motion to the Security Council rejecting Netanyahu’s annexation plans.

June 19, 2020

Bodenstown and the realignment of Irish Politics

Wolfe Tone

Like the Easter commemorations earlier this year this Sunday’s Bodenstown ceremony will take place online. Sinn Féin President Mary Lou McDonald TD, who has previously spoken at Bodenstown on three occasions, the last in 2018, will give this year’s keynote address. The Coronavirus restrictions make it impossible to hold the normal event with its march and graveside oration.

My first trip to Bodenstown was as a teenager in the mid 1960s. Apart from periods of imprisonment I think I have been at Bodenstown almost every year since then. In the 1960s and 70’s, apart from Easter, Bodenstown and Edentubber were the two big commemorations for republicans. Both events were political excursions with a big social content. Busloads of republicans descended on County Kildare. At a time when republicans got little media coverage the Bodenstown speech was regarded as especially important when the republican leadership of the day set out its position on issues of the day. This was before social media and other modern means of communication. Public events and pamphlets were the main means of political discourse.

In the last few decades attendance at Bodenstown has decreased despite admirable efforts by Kildare republicans especially with support from Dublin and South Leinster comrades. This is a consequence of our busyness and of the sheer increase in other commemorative events from Hunger strike Commemorations, the 1916 Centenary and many local or regional public events. So Bodenstown has to compete with all that. It does so very well. It remains a national event when republicans get to meet up usually, but not always on a sunny summery day. It is also a nice walk from the picturesque village of Sallins to Bodenstown Graveyard.

Wolfe Tone

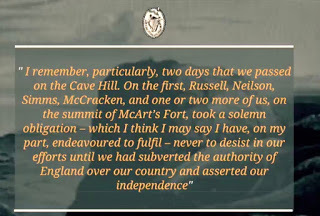

This is the burial place of Wolfe Tone, one of the leaders of the 1798 rebellion. Tone, and the other leaders of that time were responsible for establishing republicanism in Ireland. He linked Protestant and Dissenter with Catholic under the United Irish banner. He sought to create a real democracy on the island of Ireland based on liberty, equality and fraternity. Ideals which are as relevant today as they were two centuries ago.

The defeat at Vinegar Hill 1798

Tone’s central thesis has remained a cornerstone of Irish Republican philosophy to this day. He wrote:

“To subvert the tyranny of our execrable Government, to break the connection with England, the never, failing source of all our political evils, and to assert the independence of my country – these were my objects. To unite the whole people of Ireland, to abolish the memory of all past dissensions, and to substitute the common name of Irishman in place of the denominations of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter––these were my means.”

Bodenstown 1912

The earliest image I have seen of a republican ceremony at Bodenstown is a very grainy black and white photograph taken in 1912. It shows a large number of people, led by Na Fianna Éireann, walking in sunshine along the country lanes from Sallins to Tone’s grave. Tom Clarke, later executed by the British for his leadership role in the 1916 Rising, gave the oration. On the left of the image you can see Countess Markievicz and among those walking beside her is Liam Mellows.

Like all such gatherings it was banned by the Brits under martial law 1920-1921. In 1921 the ban was broken by a group of Cumann na mBan women who at the request of Michael Collins travelled by car from Dublin to Bodenstown and laid a wreath.

The following year, on 20 June 1922 Liam Mellows gave the annual Bodenstown speech in which he denounced the Treaty which had been reached with the British six months earlier. Mellows then travelled back to the Four Courts which had been occupied in April by IRA volunteers opposed to the Treaty. He was captured there several days later by Free State forces and in December Mellows, Rory O'Connor, Joe McKelvey and Richard Barrett were executed by firing squad.

The Cosgrave government banned Bodenstown in 1931 but republicans successfully broke the ban. Three years later 36 workers from Belfast’s Shankill Road participated in the event. It was a time of political turmoil in republican politics as some republican activists, led by Peadar O’Donnell were advocating the development of class politics under the Republican Congress. At Bodenstown that year the organisers ordered that only official banners could be carried. The Shankill Workers, who had their own banner and others who were marching behind a Dublin banner, were attacked by other marchers.

Shankill Workers take paert in 1934

A Bodenstown speech which attracted a lot of attention was that given by Jimmy Drumm, husband of murdered Sinn Féin Vice President Máire Drumm, in 1977. In the early 1970’s some republicans believed that the war would end in a matter of a few short years. By 1977 it was obvious that this was wrong. There was a need to put down a marker regarding republican strategy, and Bodenstown provided the opportunity to do that. The involvement of Jimmy Drumm was important because he had a long track record in the movement. It was a speech which clarified republican attitudes to some issues, including the prospect of a long struggle, and set down a marker for changing political strategies in the time ahead.

For my part speaking in 1979 I addressed the need for republicans to build a political alternative to so called constitutional politics. In 1981 the Bodenstown ceremony took on a different complexion when Dingus Magee, who less than two weeks earlier had shot his way out of Crumlin Road prison along with seven other political prisoners, turned up to wave to the crowd. He received a huge welcome and when An Garda Síochána tried to move in to arrest him marchers lay down on the roads and blocked them.

The execution of Henry Joy McCracken

1998 was the 200th anniversary of the 1798 Rebellion. Bodenstown that year was one of the biggest I can remember. All our leaders have spoken at Bodenstown. The development of the republican struggle can be measured in part by Bodenstown speeches. Some day some budding historian will analyse and weigh up the import of what was said particularly in our time - the endgame of our struggle from 1970 onwards.

This is a period -a Decade of Opportunity- for progressive politics especially the politics of Tone and his vision of breaking the connection with England.

The commitment within the Good Friday Agreement to a referendum on Unity is the means by which we can achieve this. No other generation of Irish people whether in the most recent phase of conflict or in 1916 or in 1867 or 1798 had the opportunity to achieve unity peacefully and democratically. We have that opportunity and that ability. I believe we can do it. I am convinced that more and more people – of all political persuasions – are coming to the realisation that Irish Unity is the way forward for all the people of this island. Irish Unity is now a doable project.

Mary Lou’s speech this Sunday comes at another decisive moment. The ongoing realignment of Irish politics with Fine Gael and Fianna Fail being forced by the strength of Sinn Féin to coalesce in a desperate but vain effort stop change and to shore up the status quo and the re-establishment of the power sharing government in the north and the other Good Friday Agreement structure along with Brexit are all issues she may address. So join us online for Mary Lou’s Bodenstown speech on Sunday.

It will be broadcast on Sinn Féin’s Facebook, Twitter and Youtube pages.

These are:

June 12, 2020

You don’t get to be Racist and Irish

The George Floyd mural on the Falls Road

You don’t get to be racist and Irish

You don’t get to be proud of your heritage,

plights and fights for freedom

while kneeling on the neck of another!

These are the first four lines of a new poem by the singer Imelda May. It is a powerful and moving poem which vividly sums up my feeling on this divisive issue.

A sad fact of life is that racism exists in most societies. That reality struck home in recent weeks following the killing of George Floyd in the USA by Minneapolis police officers; in the response of President Trump, and the brutality of elements of the police service who have attacked peaceful protesters.

In my visits to the USA over a quarter of a century I have met many good people and many good leaders. Leaders in business and commerce, in communities, the Arts, the Labour and Women’s movements and in politics.

But I have long believed that race is the big unresolved issue at the heart of US society. It and sectarianism in our own place are two sides of the same coin. Both can be found in societies across the world where those in power or those who seek power, use racism and sectarianism as a means to divide, control and exploit people.

That’s why Imelda Mays poem is so pertinent. And so important. We Irish who were/are subjected to racism cannot treat others as we were/are treated. When the English ruling class first invaded Ireland they said it was ‘to civilise the barbarians’. The native Irish were variously described as lazy, stupid, violent, backward, barbarous and inferior. Over the centuries that followed English writers constantly justified English actions by claiming that Irish people are culturally inferior and that the English would civilise us. An English writer Edmund Spenser in the late 16th century wrote of the Irish: “...they steal, they are cruel and bloody, full of revenge, and delighting in deadly execution, licentious, swearers and blasphemers, common ravishers of women and murderers of children.”

English writers and historians frequently presented the Irish as rogues, drunkards and brutal.. David Hume in his influential “History of England” first published in the 1750s wrote: “The Irish from the beginning of time had been buried in the most profound barbarism and ignorance.”

It was this sense of superiority, allied to the development of plantations in the Caribbean and in America, which saw England become the main European slaving nation. The language used to describe Africans was essentially the same used in relation to the Irish. The Irish were ‘inferior’; the Africans were ‘heathens’. Hume, who accused the Irish of barbarism and ignorance, described Africans as “naturally inferior to the whites.” He wrote: “There never was a civilised nation of any other complexion than white ...”

This belief in their racial superiority by the English elites over the Irish and over African peoples, and of the white race over all others, has been a constant theme of British Imperial history. A history which English people are not taught. It can be found in the stage Irish and the jokes of the 19th century which labelled the Irish as idiots and drunks. Irish people and black people were often compared to apes. In 1862 the magazine Punch, which frequently published cartoons in which the Irish had ape like features, wrote; “A creature manifestly between the Gorilla and the Negro is to be met with in some of the lowest districts of London and Liverpool by adventurous explorers. It comes from Ireland, whence it has contrived to migrate; it belongs to a tribe of Irish savages ... it talks a sort of gibberish. It is moreover a climbing animal, and many sometimes be seen ascending a ladder laden with a hod of bricks.”

Irish emigrants seeking a new life in the USA and other places following An Gorta Mór also experienced racism in their new countries. I have a small notice that was in the window of a house in Boston advertising rooms for rent which says ‘No Irish need apply’.

As Ireland grappled with Home Rule at the end of the 19th century British racism was given expression in a virulent anti-Catholic rhetoric. Unionist political leaders who opposed home rule merged racism with sectarianism. It became part and parcel of the northern state established by partition. Catholics were presented as inferior, lazy and living off the dole, and with too many children. In May 1969, just months before the August pogroms ignited decades of conflict the then Unionist Prime Minister of the North Terence O’Neill - a liberal unionist - echoed this. He said: “It is frightfully hard to explain to Protestants that if you give Roman Catholics a good job and a good house they will live like Protestants because they will see neighbours with cars and television sets; they will refuse to have eighteen children. But if a Roman Catholic is jobless, and lives in the most ghastly hovel he will rear eighteen children on National Assistance. If you treat Roman Catholics with due consideration and kindness they will live like Protestants in spite of the authoritative nature of their Church".

Racism also plays a dangerous and unacceptable role in society in the Southern state. In 2004 the Fianna Fáil government introduced the Twenty-seventh Amendment of the Constitution. It stripped a child born in Ireland of immigrants of its right to Irish citizenship.

Last week An Taoiseach Leo Varadkar described racism as a virus and urged that citizens show solidarity in seeking to defeat it. Almost in the same breath he defended Direct Provision – a shameful inhumane system which holds immigrants in the most difficult and dangerous of conditions – isolated and segregated from the rest of Irish society. The Irish Refugee Council has described Direct Provision as “state sanctioned poverty”.

In 2017 the decision to recognise Traveller ethnicity finally brought the Irish State into line with recognition already in place in the North, as well as in England, Scotland and Wales. Sadly little has changed since then. Last year the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) produced a comprehensive report on the treatment of Travellers, refugees, the Direct Provision system, anti-racism laws and hate crime. The report was a scathing indictment of the failure of successive Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil led governments. It identified major legislative and policy failings in relation to hate speech, hate crime, the response of An Garda Síochána to these and the use of ethnic profiling by the Garda.

So, we cannot decry racism in the USA and not recognise its odious presence in our own place. We cannot rail against racism in the USA or elsewhere without fighting racism in our own place. Racism is especially toxic when it infects the agencies and institutions of the state. And it is obvious to all of us who lived through the baton charges, the rubber and plastic bullets and the gas that were used by the RUC and British Army that they don’t work. They are not the answer. What works is treating people as you would want to be treated yourself.