Stephen Embleton's Blog, page 7

July 25, 2022

There is Magic in African Literature (full Oxford article)

(published in the 2022 University of Oxford, African Studies Centre Newsletter)

I wish to thank Onyeka Nwelue, James Currey and Professor Miles Larmer (and the African Studies Centre) for their support and in facilitating my activities as the James Currey Society Fellow to the University of Oxford in 2022.

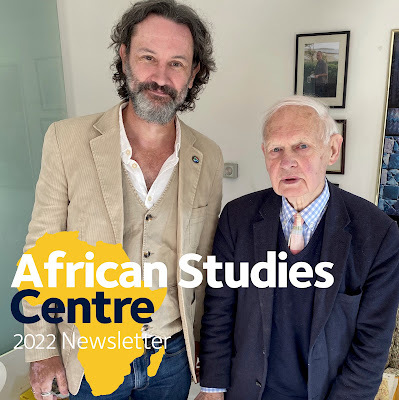

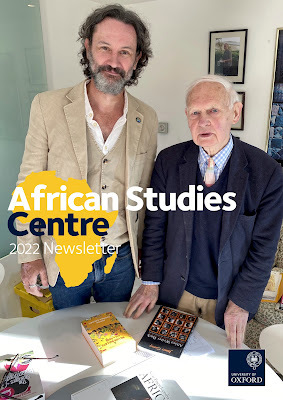

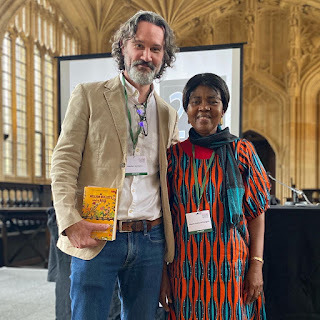

After running the 4-week James Currey Society Writing & Publishing Workshop at the African Studies Centre, my time culminated in a lecture event on 14 February 2022. Opened by Onyeka Nwelue, and leading a Q&A with James Currey on his life and legacy with the African Writers Series, Professor Larmer then introduced me for my lecture to members of the audience – both in the lecture theatre as well as virtually online. Questions had already been raised by those in attendance relating to publishing, genres and themes within African literature and the AWS. I hoped to shine some light on these.

My 14 February 2022 lecture in Oxford

My 14 February 2022 lecture in Oxford

There is magic in African literature.

As the embodiment of 1980s South Africa, as a teenager, I was not aware of the African Writers Series, let alone its impact around the world, and therefore came late to many of the writers and the rich stories from the Continent. I found their works individually rather than through the body of work that is the AWS, discovering the writers who had reached the status of household names, even in South Africa, by the mid 1990s – in particular Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Nadine Gordimer. These were the tip of the iceberg.

I became involved in writing in the early 2000s, and was involved in the African Speculative Fiction Society as a charter member. In many of the discussion amongst us writers from the Continent, there was talk of this entity The African Writers Series. And though I knew the names of the writers they would mention, I had no context for what this body of work was. I began looking into it, and soon realised the significance those works and what the publishers put together from the early 1960s until its closure in 2003.

In terms of what James Currey contributed, his tenure was one of the most prolific of the AWS. It went from around thirty books published, to over two hundred titles added during James Currey’s time from the late 60s to the mid 80s. Having the opportunity to meet and talk with the man himself, one key element stood out in terms of how the AWS successfully operated: there was no single veto right from any team member in a work submitted for publication. If a team member believed in it, it had value to the whole. This is the magic of the African Writers Series – making for a broad range of literary work.

Over the years, my research into the African Writers Series revealed a wealth of themes and genres which, at first glance, tackle social issues like colonialism, racism, and traditional beliefs versus Western religions. I soon realised there was a lot more to it.

The AWS gave voice to writers on the Continent, in troubling times in the 1960s, through apartheid, and into the 90s. It gave those writers a voice. It put those cultures on the map. It gave those cultures dignity. They were being written about by those people. And it was an opportunity for dispelling the notion of what the West perceived Africa to be. In that, from my perspective, traditional beliefs really came to the fore. Not just in nice cultural rites and rituals: it dispelled the myths of what those rituals might be. Words like superstition, witchcraft and black magic no longer had a place. That was how Africa and those cultures, rituals, belief systems, mythologies, folktales and oral traditions were perceived and portrayed by the West.

The other important point was on the impact of the African Writers Series, yes, reaching global status, but it brought African stories to Africans. This came through in the conversations I was having with my contemporary writers.

While I was on a virtual panel at WorldCon/Discon3 in December 2021 – The Nommo and Other Awards for African SFF – one of the other panellists remarked on a common issue felt by African writers of genre fiction (speculative fiction covering fantasy, folktale-based fantasy, science fiction etc.): we are not considered writers of literature. We are on the fringes of publishing and audiences, and we are not considered literary contributors. I had already begun my research into the AWS in earnest, and took that opportunity to highlight some of my findings.

I selected the first 101 titles of the African Writers Series, making sure I covered part of James Currey’s tenure, into the mid 1970s. 45 of these 101 titles contained very clear genres and themes of traditional beliefs, magic, fantasy, speculative fiction and magical realism.

In the broad theme of Traditional Beliefs, these were not just mentioning a culture’s beliefs in day-to-day life, but actually going the step further and bringing the magic and fantasy into the narrative, like spells, spirit realms, afterlives; along with the speculative: alternate realities and fictional African countries. From my perspective as a science fiction and fantasy writer, these are all genres that are very much explicit, and not in the background of these 45 titles I picked out. They are weaved in and integral to the stories.

Yet, when we look at this body of work, it is referred to as a “literary” genre. To me, seeing what is there as if for the first time, it is far more than that. And many of these works are genre-fluid – by including multiple of these aspects, and defying what most western categories would pigeonhole them into.

Take Bessie Head’s Maru, one would think it would have been marketed as magical realism, but it wasn’t.

We have the opportunity, now, to reread the 300 plus works in a new light, look at the traditional beliefs, the storytelling, the oral storytelling, and how they weave in their proverbs, traditional beliefs, and magic into their works, seamlessly. They do not stand as simply literary fiction. They cover all depths and breadths of what I consider to be speculative fiction.

Going back to the WorldCon panel: for the other panellists this was a revelation to be part of and contributing to this literary community.

As a significant part of my fellowship to the University of Oxford, I was asked to run the 4-week James Currey Society Writing and Publishing Workshop, where we had participants coming in from all over the world, from all over the Continent. Needless to say, having Mr Currey attend the workshop was both daunting and surreal.

In the first session I covered the history of the AWS and James Currey’s prolific tenure, and it was rewarding having James enlighten us all on various parts of his journey. Fascinated by my take on certain aspects of the AWS, he would probe my take on some of the works, making for a most rewarding experience, and an experience I will forever cherish.

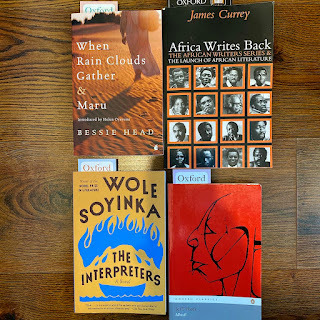

Allowing the African Writers Series to speak for itself, I selected five works from the first 101 titles: Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi (1978/1938) AWS #201, Stanlake Samkange’s On Trial for My Country (1967) AWS #33, Wole Soyinka’s The Interpreters (1970) AWS #76, Bessie Head’s Maru (1972) AWS #10, and Short African Plays edited and compiled by Cosmo Pieterse (1972) AWS #101.

First, was Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi (1978/1938) AWS #201, which has a rich and interesting history. It was written in 1912 and only published in the 1930s, in a redacted form due to its incendiary content for the South African government of the time. It was then republished by the AWS, where the team went back to basics, back to the original translations and brought out all the original text. One of Mhudi’s key aspects, for me, is that it has a strong female protagonist – not only a female in a man’s bloody world – she is supporting other women, women supporting women in a man’s world. The narrative comments on how men mess up the world with their wars.

“How wretched,” cried Mhudi sorrowfully, "that men in whose counsels we have no share should constantly wage war, drain women's eyes of tears and saturate the earth with God's best creation - the blood of the sons of women. What will convince them of the worthlessness of this game, I wonder?” – Mhudi, Sol Plaatje

My interest being in traditional beliefs allowed me to see the significance of Mhudi’s dreams. She is driven by her prophetic dreams, she believes in her dreams, the premonitions and she acts on those throughout the story. Along with proverbs and elements of magic, as well as the historical setting, make for a rich text.

Stanlake Samkange’s On Trial for My Country (1967) AWS #33 blew me away because on one hand it has three tiers to its oral storytelling structure; and on the other, it is set in a fantasy world.

We begin first with the narrator, as the author, in the story; followed by an old man he meets at a fireside in a cave, who relates his own story of when he died and went into the Afterlife. This brings the third level of the narration as he is witness to the trial of Cecil John Rhodes and the Matabele monarch Lobengula. Both men are forced to stand before their respective ancestors in the Afterlife, each questioned on their roles in the British takeover of the ancestral lands. From their own telling of their sides of the historical story; to witnesses brought in to give their accounts.

When we consider Rhode’s perspective, his justifications, he tries to distinguish between duty to God and his religion vs duty to the crown and the Queen. The monarchy being the most important, and summed up in his belief that the more of the world that is absorbed by the British would mean “the end of all wars.”

It is a rich, speculative story (fictional accounts and justifications) by Samkange, banned in Rhodesia at the time, and set in a fantasy world in order to make sense of his own world.

When I looked to the book summary, nothing mentions the fantasy aspect of the story. They talk about the historical significance and the real-world, historical characters, but not this journey into the afterlife and the ancestors judging them.

Wole Soyinka, The Interpreters (1970) AWS #76. Soyinka’s approach to colonialism and the emergence of a new country stood out to me in how he used five protagonists, like archetypes of the new Nigerian society at the time of independence. Many of the AWS works up until this time featured people pushing back against colonial rule and, if anything, looking to their traditional beliefs and customs as guiding forces in their new world. The five protagonists, each standing in as the reader’s interpreters of the emerging society, are reluctant to completely throw out colonial infrastructures or turn fully to traditional beliefs, believing some customs to be outdated in this new Nigeria. In terms of the fantastical, using flashbacks to “visit” specific moments that have meaning to each character, Soyinka moves us seamlessly between the real world and the imagined world as the five figure themselves out and openly dissect one another’s experiences.

Their view becomes one of utilising the good of tradition and the good of Western infrastructures in order to build a society from those rather than one replacing the other. Another aspect of the novel is the concept that there is not always a happy resolution to life.

“If the dead are not strong enough to be ever-present in our being, should they not be as they are, dead?” – The Interpreters, Wole Soyinka.

Bessie Head’s Maru (1972) AWS #101, I put on a level with a Shakespearean drama and has become one of my favourite novels. What Bessie Head did in terms of bringing in the traditional beliefs of the |Xam-ka, the Namakhoen, the ǂNūkhoen people of Botswana. Their mythologies about the relationship between the Sun and the Moon to those people – literally and metaphorically – the protagonist as the moon and the antagonist as the sun. In local mythology, the moon has the ability to eclipse the sun (and portends rain), and is a far gentler aspect than the sun’s harshness.

Head’s magical realism is magical, in that it weaves local culture into what, on the surface, appears to be a love story, a drama, centred around racism. What emerges is a multi-layered narrative by Bessie Head, demanding multiple reads.

“Moleka was a sun around which spun a billion satellites. All the sun had to do was radiate force, energy, light. Maru has no equivalent of it in his own kingdom. He had no sun like that, only an eternal and gentle interplay of shadows of light and peace.” – Maru, Bessie Head.

Short African Plays edited and compiled by Cosmo Pieterse (1972) AWS #101. As someone who has more short stories published than novels, I brought these plays into the workshop to illustrate the elegance of short-form writing. Another key reason for me featuring this anthology, and with my film and TV background, was to show the readability of plays and scripts, rather than thinking they require a performance to appreciate the content.

Three plays stood out, all three containing magic and fantasy elements: Ancestral Power by Kofi Awoonor (Ghana); The Magic Pool by Kuldip Sondhi (Kenya); and Life Everlasting by Pat Amadu Maddy (Sierra Leone).

Ancestral Power shows the arrogance and folly of someone who is able to wield the power of lightening. Pat Amadu Madd’s Life Everlasting, for me, is a dark comedy with pointed insights into life in the real world, but set in a starkly different rendition of Hell than what we are used to: rather than a place of torture and torment, it is a place to learn, love and accept who you are.

And finally, Kuldip Sondhi’s The Magic Pool features the tragic magic and fantasy around a water goddess, the spirit of the pool, as our protagonist struggles with who he is in the real world, longing to be accepted by his peers.

“In the realm where fantasies unfold,

Grown bright o’er this starlit forest pool.

I come, wonderful boy, not from heaven or hell,

But from deep within these very waters,

Woken by your longings that weave a spell.”

– The Magic Pool, Kuldip Sondhi

The final session was particularly lively; having discussions about the future of African publishing; looking to the African Writers Series as an example of what the possibilities are; and as James Currey said to me, it is fraught with infighting and opinions, and outside forces only interested in making profits. For us, as African writers and publishers, we have the opportunity to revisit the African Writers Series as a benchmark for any and all African literature to come and sets a precedent for all African literary forms.

The variety of methods of telling their stories, the melding of genres in single works, the steadfast reluctance to be bullied or thwarted from their goals of representing their cultures on paper for the world to see meant generations see themselves on paper. With dignity. And these are inspiring aspiring writers. And our jobs as existing writers and publishers from the Continent is to ensure there are mechanisms in place that will facilitate the next, and the next, and the next generation. We have to break down more barriers to entry. And we need to know what it really was that these writers and publishers did, and how they did it, to pave the way.

As an African, I believe in magic. I hope you do too.

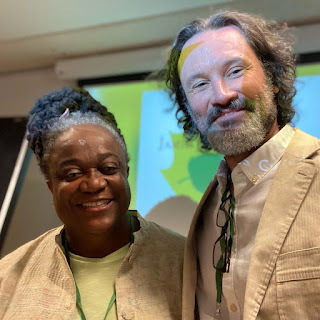

Ikenna Okeh & Kelvin Kellman share a moment of clarity and solidarity

Ikenna Okeh & Kelvin Kellman share a moment of clarity and solidarity

The James Currey Writing and Publishing workshop has helped me learn a new art of storytelling using deep African rooted writing methodologies as taught by Stephen Embleton. His teaching methods are practical and easy to apply. The learnings will be with me for a very long time. I can’t thank Onyeka Nwelue enough for opening this world of possibilities to young Africans. – David Lanre Messan

The fellowship, under the auspices of the James Currey society, and the instruction of the fulgent Stephen Embleton, is a memorable interaction of writers and thinkers from dissimilar cultures that, after enthusiastic discuss and moments of learning and unlearning, ended with the simple resolve of pushing the frontiers of writing the African narrative further and beyond. – Kelvin Opeoluwa Kellman

The James Currey Writing and Publishing Workshop which was presented by the James Currey Society, in cooperation with the University of Oxford's African Studies Center happens to be one the best academic fellowship that I've attended as a scholar.

The program gave detailed teaching into Breaking of Literary Modules, Guide to Pitch, The Journey of African Writing and Plotting and Acts. James Currey Fellow, Stephen Embleton as a professional in the field of literature used the simplest means, by breaking down every topic simply and concisely for quick understanding.

This fellowship may be short term but have taught us a vast knowledge in the field of literature which I am grateful for. Thanks to the James Currey Society and the University of Oxford, African Study Centre for this precious opportunity. – Emmanuel Ikechukwu Umeonyirioha

The workshop assumed a life of its own on the last day. As the first workshop of the Society, it did well. I like it that it concentrated on the AWS, and that James Currey was there in person to give us insightful bits and clarity from a personal perspective. This also is a learning curve for him, and with this workshop, his career has been steered towards a path of clarity and more responsibility, not only as a writer, but as an active player in this generation of African writing. – Ikenna Okeh

My meeting of Stephen Embleton at the Oxford, at first, seemed a causal social event. But when he took the lecture session, reeling and detailing artefacts of literature, it soon turned to one of endearing follow up. And given his recent antecedents, he's a worthy fellow of the James Currey African Institute. – Idorenyin Akwaowo Amaunam

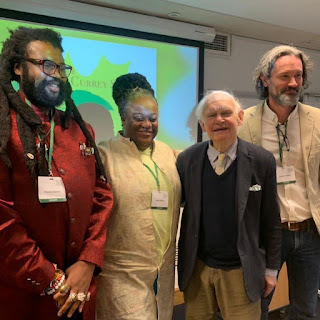

James Currey (centre) and head of the ASC, Professor Miles Larmer (James' right)

James Currey (centre) and head of the ASC, Professor Miles Larmer (James' right)

Thanking everyone involved for the opportunity granted to me at the James Currey Writing & Publishing Workshop. The workshop was as expected, successful and insightful throughout and so much was learnt.

It is important to thank Dr. Onyeka Nwelue for making it possible and founding the James Currey Society, Prof. James Currey, for his thoughts, presence, impactful teachings and the facilitator Stephen Embleton. Through the workshop, we had basic, foundational and complete guild needed as a writer, storyteller or a filmmaker like myself, through exemplary models established by aficionado scholars, personnels and the African Writer’s Series (AWS).

Many thanks to you all. – Mishael Maro Amos, 28Studios

Download the PDF newsletter here or here.

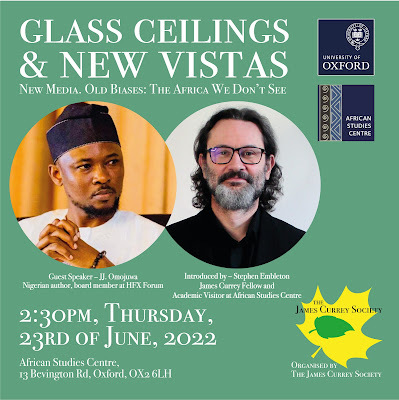

June 24, 2022

JJ Omojuwa Event University of Oxford

23 June 2022. We kicked off our discussion with JJ Omojuwa at the African Studies Centre (University of Oxford), with a quote from JJ's book's dedication:

To the struggling African,

things will not become easier; you must learn to be better, everyday.

Soon, you will thrive, prosper and conquer. Remember to take others

along when you do.

JJ Omojuwa

JJ Omojuwa

With around 15 of us, Onyeka Nwelue made introductions and we asked those attending to introduce themselves and their backgrounds. I then introduced JJ Omojuwa in relation to my own media background:

When I came to the internet in the mid-nineties, it was very much the wild west. Everybody was putting anything they wanted to onto the internet, saying what they wanted to, so there was a time when there was absolute freedom of information flowing. And then, we come into the 2000s and governments start getting involved, they are seeing the potential and so we were having this battle between those free voices and those big organisations, big government, trying to wield their power. JJ Omojuwa (and myself) believe strongly in the democratisation of this digital space, rather than over-regulation.

JJ speaks to leadership, and the youth being the leaders of tomorrow, TODAY. And beyond the misconception that "leader" only pertains to political leadership.

I see the current landscape in the following way: Passive Media (old media) vs Active Media (new/digital media/social media)

Passive: Sitting watching the TV and accepting what is getting thrown at you, consuming.

Active: Social media etc. The digital wealth is in your hands. It is up to the individual to decide: what they want to consume, when they want to consume it, and where they are going to consume it.

From JJ's perspective, the landscape is still changing. We are still learning. Finding our ways of telling our stories. Global media platforms vs the media in our own hands, telling our stories. Democratising this space.

People are the essence of everything. Whatever we want to build. Whatever conversations we want to have. Whatever ideas. People are the essence of everything. And there is a lot of magic that happens when people meet. – JJ Omojuwa

"Be humble enough to be grateful of what you know, appreciative of how far you've come, to know there is just a long way to go. And to also accept that the models that shape the world today were not designed for us as Africans. They were not. We must ask new questions of our world. And ask as it is remodelled. Not for us but for a world that is just and equitable. And not equitable for the sake of TV, and appearances. Equitable in the real and absolute sense."

Habeebah Bakare and Sonny Iruche

Habeebah Bakare and Sonny Iruche Lorenzo Menakaya discussing media

Lorenzo Menakaya discussing media

Also in attendance was Sonny Iruche: Senior Academic Visitor to University of Oxford (experience as an investment banker, politics, including South African and Nigerian relations). He gave his perspective of the past decades on the continent and young Africans being eager to take their destinies in their own hands.

Habeebah Bakare – from Nigeria, involved in global health and development, and Nigeria's public health sector. Habeebah spoke towards individuality, biases, and the "new model" – in her own work and discussions around representation and using the media. She realised there are three key factors in this work:

Power Imbalance – who is the one in the power position, dictating their views – down to the one who "pays the bills"Regulation – social platforms as well as governments imbalancing dialogue.Protection – safe spaces for people to speak up AND to choose not to speak out. Or anyone sharing opposing views to the norm. Abibiman Publishing's growing catalogue!

Abibiman Publishing's growing catalogue! Onyeka Nwelue, Sonny Iroche

Onyeka Nwelue, Sonny Iroche Onyeka Nwelue

Onyeka Nwelue JJ Omojuwa's book "Digital: The New Code of Wealth"

JJ Omojuwa's book "Digital: The New Code of Wealth"

June 21, 2022

The Sauutiverse Collective

Sauúti is taken from the word “Sauti” which means “voice” in Swahili. This world is a five-planet system orbiting a binary star. This world is rooted deeply in a variety of African mythology, language, and culture. Sauúti weaves in an intricate magic system based on sound, oral traditions and music. It includes science-fiction elements of artificial intelligence and space flight, including both humanoid and non-humanoid creatures. Sauúti is filled with wonder, mystery and magic.

I am excited to finally be able to tell everyone about this project and so privileged to be part of this collective – the Sauútiverse. Spearheaded by Wole Talabi, Fabrice J. Guerrier (Syllble) and Dr. Ainehi Edoro (Brittle Paper)

"...it’s been really incredible to witness these African writers from different walks of life come together to use their imaginations to change the world." – Fabrice Guerrier

10 authors from five African nations:

Akintoba KalejayeEugen BaconStephen EmbletonDare Segun FalowoAdelehin IjasanCheryl NtumyIkechukwu Nwaogu Wole TalabiXan van RooyenJude Umeh"Built on the philosophy of community and ubuntu, the collective’s hope is that this fictional world will be a sandbox for generations of African and African diaspora writers to work together and imagine endless possibilities of something new for a continent on the brink of cultural rebirth and renaissance."

"Through worldbuilding and creating a new universe, writers in the Sauúti Collective at Syllble have been empowered to dream more, share critical ideas, and occupy the forefront of innovation in the speculative space, bringing something entirely new to the global table."

#Sauútiverse #Sauutiverse #TheSauutiverse #TheSauutiCollective

Read more here:

April 4, 2022

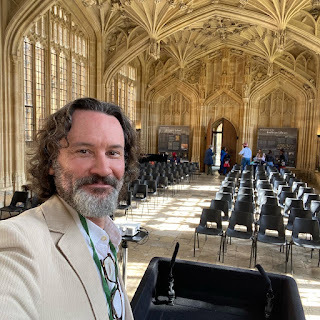

Oxford Literary Festival April 2022

The FT Oxford Literary Festival 3 April 2022:

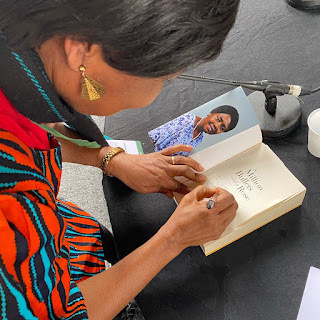

Professor Akachi Adimora-Ezeigb (centre) Professor Leslye Obiora (right)

Professor Akachi Adimora-Ezeigb (centre) Professor Leslye Obiora (right)

In the auspicious setting of the Divinity School, Bodleian Library, at the University of Oxford, I had the pleasure of chairing an emotional and informative session on the Biafran War, gender equity and social/cultural issues. Along with Professor Leslye Obiora (current Professor of Law at the University of Arizona) our conversation centred around Professor Akachi Adimora-Ezeigbo’s sweeping novel “A Million Bullets & A Rose”.

Difficult to sum up here:

Professor Akachi’s experiences as a girl during the Biafran War (how writing her novel nearly 40 years later helped her deal with the trauma), and bringing in the lived experiences of her family and friends (devastatingly captured in her writing); the impact of the African Writers Series, and having role models for young women to be inspired.

Professor Leslye’s childhood and direct inspiration from her close relative Flora Nwapa and her continuing legacy to girls and women in Nigeria and around the world as the mother of African Literature. This propelling Professor Leslye into law, human rights and fighting for gender equality from Nigeria and to the world. As well as speaking to the importance of literature to tell stories, and histories of people when those histories are edited and blatantly omitted by outside forces wanting to maintain control.

The African-centred events on the programme were facilitated in a large part by Onyeka Nwelue and the James Currey Society.

I was asked to introduce Professor Leslye Obiora for a fascinating lecture covering everything from the African Writers Series and James Currey to African politics and the change that is possible if everyone is willing to engage, no matter your beliefs, cultures and histories. And with James Currey in attendance.

The James Currey Society, who was one of the sponsors of FT Oxford Literary Festival, invited Professor Leslye who is niece of Flora Nwapa and former Minister of Mines and Steel, and current Professor of Law at the University of Arizona — among the many initiatives she champions for human rights and gender equality around the world.

March 15, 2022

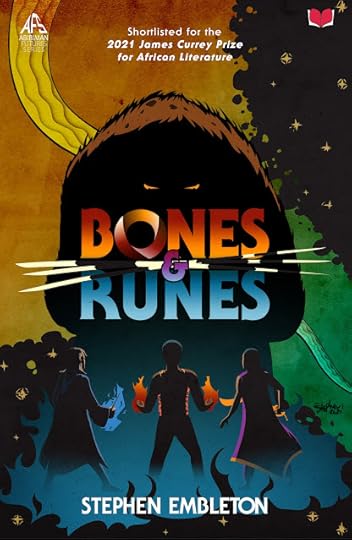

Bones & Runes Paperback Published

This is something I'm really proud of. The writing of it was truly a fantastical journey and came to be with the support of my family and the real experts in the fields of southern African cosmologies and linguistics. Published in paperback by Abibiman Publishing and their African Futures Series, and brought into the world by the determination and passion of Onyeka Nwelue. This is the manuscript which gave me the opportunity to be the James Currey Society Fellow at the University of Oxford in 2022.

This is Book 1: the adventure will continue...

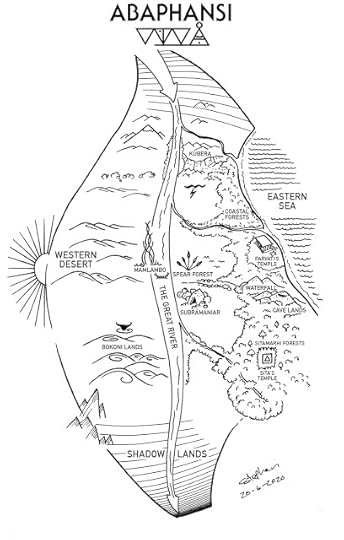

Map of Abaphansi

Map of Abaphansi

First Edition Cover (and inside flaps)

First Edition Cover (and inside flaps) "Bungapheliyo uMhlaba Amazulu" (The Eternal World is the Heavens)

"Bungapheliyo uMhlaba Amazulu" (The Eternal World is the Heavens)"Highly original and compelling. Embleton's strange world is immersive and intriguing. This is a novel of adventure and ideas.” – T.L. Huchu, author of 'The Library of the Dead’

“Embleton’s portrayal overflows with imagination, filling it to the brim with all manner of beings and deities from Zulu tradition. Richly imagined and powerfully authentic.” – Damien Lawardorn, AUREALIS #148, March 2022

Synopsis:Three friends have their loyalty, beliefs and ancestral magic pushed to the limit.

Mlilo, a young isangoma, is forced to call on his friend Dan, a Druid apprentice, to help him retrieve his sacred amathambo (bones) from the clutches of evil. Taking us on an unprecedented journey through the magical realms of his ancestry and traditional beliefs, Mlilo's emerging skills are tested in life or death encounters with beings from the realm of Abaphansi. Amira, a close friend of Dan’s, has her own independent path to forge but will soon find that her personal quests are inextricably linked to the two men.

The three young adults, finding their way in the world, still have much to learn about themselves, their conflicting approaches, and their true callings. They must work together, combine their skills and find the talismans that make up Mlilo’s bag of bones, the key ingredient to an isangoma’s abilities and powers in this and the other worlds around us. While the gods, demigods, deities and shapeshifters, all with their own agendas, make navigating Abaphansi a deathly challenge.

The solitary isangoma, self-reliant to the extreme, will learn the importance of friendships, alliances and the meaning of living life in the real.

PRESS:

"CLARITY AND DUALITY IN THE FANTASTICAL REALM – A DIALOGUE WITH STEPHEN EMBLETON" – Davina Philomena Kawuma. Africa In Dialogue.

March 11, 2022

Documentary Film Posters

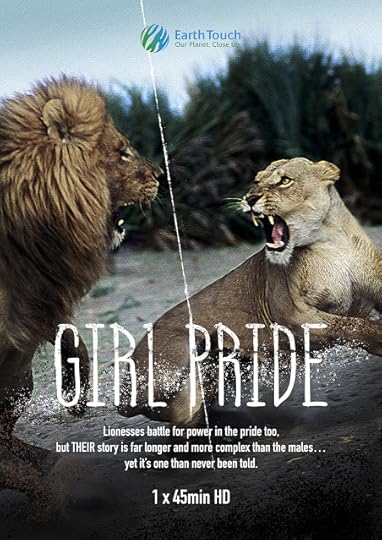

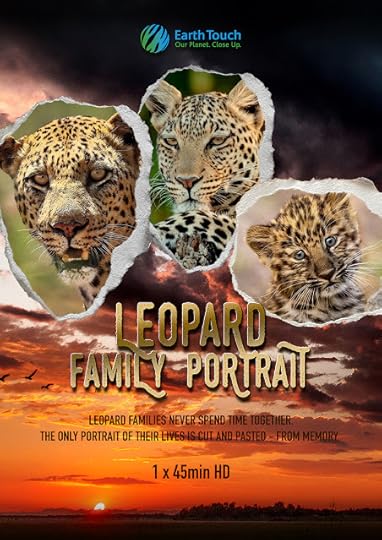

Since leaving Earth Touch in 2019, I have continued a creative relationship with a great team. Here are some of the works I've produced in 2020-2022.

MIPCOM DISPLAY STAND POSTER (Oct 2021 & March 2022 versions):

MIPCOM Oct 2021

MIPCOM Oct 2021 MIPCOM March 2022 (extended)

MIPCOM March 2022 (extended) POSTER (2020)

POSTER (2020) POSTER (2020)

POSTER (2020)

February 27, 2022

War & Love (Poem) in Support of Ukraine

War & Love

Stephen Embleton — 27 February 2022

You bring us war,

We bring you love.

You bring a weapon,

We bring a dove.

You drag your rage, your hate, through mud.

We bring our hearts, our souls, our blood.

You drop your bombs,

We show you grace.

You bear arms,

We hold, embrace.

You capture, conquer and control.

To fly your flag, your only goal.

You play aggressor.

We unite as defender.

You tear it down.

We build it up.

Your cycle loops on a hamster wheel.

We won’t repeat, we’ve seen the reel.

Know your history.

War is no mystery.

Yet you choose the dark. You choose to fight.

We live for peace. We choose the light.

We release. We free. One word we sing.

From atop the mountain, we let “FREEDOM” ring.

February 17, 2022

Sub Migratio (2017) Short Story

My short story, Sub Migratio, was published in April 2017 in the first edition of Enkare Review, the Nairobi-based literary magazine (now closed). I've posted the story here for everyone to read and enjoy.

"a futuristic tale that is bleak in every sense of the word, written by Stephen Embleton"

Also read the Twitter chat/interview with the Enkare Editorial Team here. Cover Image ‘Mutua in the City‘ (c) 2017 Imeldah Natasha Kondo – a self-taught photographer based in Nairobi, Kenya. Find more of her work on Behance

Cover Image ‘Mutua in the City‘ (c) 2017 Imeldah Natasha Kondo – a self-taught photographer based in Nairobi, Kenya. Find more of her work on Behance

In this Issue:

Editorial; An Introduction to Issue I

Fiction

Sub Migratio by Stephen EmbletonDeath of the Guava Farm by Wanjala NjalaleYellow and a Funeral by Wairimũ MũrĩithiItunu by Eboka Chukwudi PeterWho Will Tell This Story by Amatesiro DoreThe Twenty Pa’cent Offer by Frances OgambaPoetry

Into the Sun & Other Poems by Michelle AngwenyiGay Boy Blues & Other Poems by Romeo OriogunHājar in the House of Rust & Other Poems by K.A.ALINonfiction

Wooing a City: Nairobi Origins by Otiato GuguyuRegarding Literary Magazines: An Interview with David RemnickBonus

Plato by M.V SematlaneAs a Dewdrop in the Bed of a Tropical Leaf by Sylvie TaussigIbwe by Mapule MohulatsiAeaea by Liam KrugerSub MigratioApril 29, 2017by Stephen Embleton

“I’m cold.”

“Quiet.”

“How long?”

“Another five minutes, so get some rest while you can, Josh.”

The only other sound in the pitch-blackness came as he folded his arms and nestled his numb fingers into his armpits. He could feel his bones, his entire skeleton, infused with the cold of the concrete, as he lay flattened, taut with anticipation, and eyes staring up at nothingness.

He pivoted his head, hearing the crunch of his hair against his scalp. He noticed his shoulder blades, spine, both bony protrusions of his hips, lean calves, and heels all making contact. The ache in his right shoulder had begun to subside. He imagined the blue black bruising turning yellow now.

The black tunnel emitted a vague odour of grease, leaving his sense of hearing and touch his only comfort. In the frigid still air, he couldn’t even smell his urine-stained pants. Now mostly dry, he had relieved himself as the previous freight train had barreled past them fifteen minutes earlier, the hydrogen gases engulfing him in a storm of lights, howling wind, and his urine.

After taking to licking the moisture from the walls after the hydrogen-fuelled train had passed, Uncle Rob had said that they would get to the main water source soon. He didn’t understand dehydration but he understood the headache and now the chemical smell he knew was lurking as soon as they began walking again.

“Tell me about the trains, Uncle.”

He heard the older man take a deep breath, “Freighters.”

“They come from where you work.”

“Yes, Josh. Richards Bay harbour.”

“Dad says you’re an engineer there. That’s how we got in here.”

“Mmmm.” The sound of the man’s body shifting. “The longest freighter is more than four kilometres long.”

“I walk two kilometres to school.”

“If you walk to school and back, that’s how long they can be.”

He tried to imagine that.

“They are run by computers and there are no people on board. They are quiet except for the friction on the tracks and the hiss of the gas. They don’t have a single source of power, like most trains, at the head, dragging the tail behind. Rather they have distributed cryo-compressed hydrogen power units pushing, pulling its weight on the single track, in a single width tunnel.”

“They know we are here. Every time.”

“They do.”

“They try their best to kill us.”

“They’re programmed to.”

“Why?”

“Because we are in its domain.”

“We shouldn’t be here.”

“We have to.”

“It’s the only way for us to get out.”

“Yes. You understand.”

He didn’t.

He didn’t understand why they had to run. He didn’t understand why they had to leave their home. He didn’t understand why they had to be here, without his father, in the dark, in the ice cold.

“When will we go back to the surface?”

“I told you. When we get to the end. It’s not safe on the surface. Their drones struck far into central South Africa, even up to Botswana. The bombs won’t get us down here. It’s the safest underground.”

“But not with the freighters.”

“We can beat the freighters.”

He wasn’t so sure about that.

“How long is it till the end?”

“Around one hundred and eighty-six days.”

“How far?”

His uncle sighed. “Nine thousand three hundred kilometres.”

He didn’t understand that.

“How many times to school and back is that?”

“Two thousand three hundred and twenty-five times.”

He closed his eyes as he tried to think about it. He tried to go through his times tables. But he didn’t know two-thousand-times anything.

“Six and a half years of walking to school and back,” said his uncle.

“I would be in grade ten by then.”

After a moment, Uncle Rob said, “Remember the map I drew you?”

He opened his eyes to the blackness of the tunnel.

*

A week after his father had left, Uncle Rob had grabbed a piece of newsprint. He had tried to concentrate on the rushed pen lines his uncle had started drawing over words like ‘Maputo Harbour Attack’, ‘150km Radius’, ‘Driven Back’. ‘Indian Ocean War’. ‘Retreat’. ‘Madagascar Stronghold’. Big red letters next to big black letters.

Uncle Rob’s pen had torn through parts of the fragile paper as he had scratched an outline and finally pointed at the resulting shape on the muddle of words. He recognised it from his classroom wall.

“That’s Africa.”

“Yes. We are here,” his uncle had said pointing over the word ‘Invaders.'”We’re in Richards Bay.”

The man had then drawn a single line, starting out straight, and then, at certain points near the top of Africa, angling to the left and right and stopping at the top left.

“We have to get into the tunnel and -”

“At your work?”

“Yes, the tunnel at my work. And we have to walk along here,” he had traced his finger along as he had continued, “through Joburg.”

“Where Grandpa is.”

“Yes,” he had noticed Uncle Rob take a deep breath.

“Will we -”

“No, we won’t see him,” Uncle Rob had raised his voice, “we will keep going. We will go along here for a long time. There will be water along the way.”

“And something to eat?”

They both looked up as the rumbling rattled the apartment’s windows.

“The tanks,” he had whispered.

“We will go through twenty other countries,” his uncle had continued.

“Really? Like?”

“Don’t worry about that now.”

“I know seven African countries: Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Angola. Democratic Republic of the Congo and Republic of the Congo are to get together. But Central African Republic is very easy.”

“Eight. South Africa.”

“Oh.”

“Where is this?” He had pointed at the end of the line.

“Morocco. We come out at the port of Casablanca.”

“Is that the end?”

“We will only know when we get there.”

“And if it’s not?”

“We will go under the sea to America.”

He had looked across at the edge of the newspaper. There was no map drawn there.

*

“When will we know we are there?”

“When you see the sun at the end of the tunnel. That will be the end.”

“What’s above us now, on the surface?”

His uncle thought for a moment.

“It was one and a half thousand K’s from Richards Bay to Victoria Falls,” he mumbled to himself. “At four K’s an hour for twelve hours, walking an average of fifty K’s a day. Six hundred kilometres from Richards Bay to Johannesburg. Twelve days. A thousand kilometres from Joburg to Vic Falls, twenty days.”

“Thirty days in a month.”

“We should be there in two days. We will hear the pounding water from the falls from a day away.”

“The tunnel won’t be quiet?”

“No. We will feel it all around us.”

“Like the freighters.”

He tried to imagine the falls, the water from the river, catching the sunlight. He tried to imagine the sun. All he saw was black.

“Who built the tunnel, Uncle Rob?”

“A machine.”

“For a machine?”

“For people. For people to put their things on a machine, trains, to get goods from place to place. These subterranean freight tunnels go across the whole continent and even under the sea to America.”

“Like subways in New York?”

“Industrial versions of subways that run permanently with freighters.”

“But if they are for people’s stuff, why do they want to kill us?”

“They have to have a clear path. Early on, people used the tunnels to cross the borders and to transport illegal goods. So they implemented the gases underground, on the freighters, and security along the tunnel’s surface. They use radar to detect from far away if there is something in their way then they will need to brake before they hit it. If something’s in their way then they need to brake before they hit it. If they detect a body – an animal -”

“A person?”

“They need to get rid of it. The infrared activates the gas system when they get closer up. The force of the freighters pushes most of the oxygen out of the way, while it pumps out hydrogen. It’s not poisonous; it’s just that we need oxygen.”

“We have to hold our breath for a long time.”

“Two minutes.”

“I can hold my breath for two minutes.”

“You’re so good. The longest freighter is ten kilometres long. They travel up to three hundred kilometres per hour. So it takes a ten kilometre-long freighter two minutes to pass us.”

“Are there any longer ones?”

“I don’t know. The military is capable of anything right now. And the worse the war gets, the more people will try the tunnels. Either they will shut the freighters down or they will die on the tracks. The military won’t allow the freighters to stop. It’s bringing supplies.”

“More bombs?”

“Yes, more bombs. Our bombs.”

“What’s today?”

“Today is a North day.”

Now he knew that if they forgot, and prepared for the wrong direction, they could die. The power of the freighters displacing the air in the narrow tunnel as it approached, pounding past them, and pulling away from them, could suck them off the floor at speeds their bodies would never survive. Each day, the freighters traveled in the opposite direction, along the single line, single tunnel.

“It’s so dark.”

“They’re hydrogen-powered, so there’s no electricity down here, no front lights on the freighters. The only lights onboard are the dim ones you see when they approach, for monitoring and inspecting flaws or mechanical issues remotely.”

“What time does your watch say, Uncle Rob?”

The whole tunnel seemed to light up a pale blue as the man turned on the light on his digital watch. For the first time in a few days he could see the thick pipe running along the top of the tunnel. His uncle had explained about the power from the surface wind-farms being converted into hydrogen and transported throughout the continent inside the tunnels – a never-ending source for the freighters.

“One A.M.”

“How far to the next loop?”

“The station at Vic Falls.”

“Those are the ones at every two hundred kilometres?”

“Yes. Crossing or passing loops as long as the longest train. They double the line for other freighters to pass trains being loaded or off loaded at these smaller stations. It’s also where the major ventilation systems, and hydro filtration systems are, draining the water vapour back up to the topside settlements for the people and crops.”

“You said it’s like an oasis.”

“For the people there, yes. Hopefully they are still safe. There’s no direct access to the surface for us to get out.”

“Don’t we want to get out there?”

“No. We have to go further. There’s only emergency technical support at those stations. Every five hundred K’s is a major station. We will try to get more food there, and keep moving.”

A cool wave of air moved over his face. They both took a sharp breath, listening.

“Are you in the gutter, my boy?”

He shifted his weight onto his left side and into the narrow groove, trying to dig deeper into the impenetrable concrete drainage. A slow trickle of ice-cold water passed between his fingers, numbing them even more.

He heard his uncle’s feet inches away from his head, both bodies aimed at the next onslaught. His arm and part of his chest now slotted in, he checked the hold by bracing his hand, elbow and shoulder against the sides. It would have to do. He relaxed.

“Uncle Rob?”

“Mmm?”

“Are you angry with my father?”

There was no answer for a while.

“Your father,” he paused, “and you, lost a good woman to the war. He was angry. I was angry for a while. Your father wanted revenge. He wanted to hurt. I understand that.”

“But what you said to him before he left?”

“I was frustrated that he wanted to do that. Knowing the risks. Knowing that he might not come back. To you.”

“You tried to stop him.”

“Yes. I tried. But your father is a passionate man. A strong-willed man.”

“Is he a good man?”

“Of course.”

“But you are not happy about him going to war and killing.”

“I am not happy about him leaving us. Leaving you.”

“Don’t you want me around?”

“I do, boy. But I want you and him with me.”

“I don’t understand some of the things you spoke about.”

“You will, one day.”

He thought back to the day they had arrived at his uncle’s apartment in Richards Bay, after a slow four-hour drive from their broken home in Ponta-do-Ouro, near the Mozambican border. His father had cried along the way, banging the steering wheel. His eardrums had shuddered when his father had shouted and screamed at nothing. They had formed the steady exodus driving south along the battered roads; the military vehicles going north.

“We have nothing, brother. I have nothing.”

“You have your son!”

“I can afford to die more than I can afford to live.”

“We are not soldiers, umfowethu! You are not trained to go to war, to pick up a gun and shoot someone. Forget shooting someone, you are not trained to avoid being shot,” he had pleaded. “We are normal people caught up in a war.”

He had stood at the apartment window overlooking the harbour in the distance while the two men argued.

“Normal? Brother, you could take all the ‘normal’ people, put them on a continent, feed them, drug them, entertain them and that is as far as their usefulness would go. The average person is a fucking useless waste of space. Consume. Shit. Fuck. That’s it. What else are they here for? We can have cows and domestic livestock do what they do. While the rest of us take the human race forward. Evolve. Progress. Contribute. Science and development was not made possible by the sheep sitting behind a screen watching the geniuses dazzle them. No. We can take them now, recycle them and the world wouldn’t know better.”

It was a clear day, but the air over the aircraft carriers and battleships was dirty, brown and heavy in the winter air.

“People died and the people who would have given a shit about them are gone too. Their neighbours, if they survived, would give as much of a shit as a cheeseburger passing through their digestive system. Eat. Drink. Game. Have a drag on a bong. Zone out. See the world as a haze of psychedelia because that’s what they need to cope with the bore and drudge of their lives. If that’s life to you then here’s a bullet. You are here just to consume. Be a statistic or get up and fight.”

“And you will die.”

“Then I die for my land. For my son. For her. Our first wave pushed them off our land and back into the sea. I’m going to be part of the second wave, fighting them back to where they came from.”

He watched as three fighter jets whizzed from right to left of his view, three hazy white trails hanging for a few moments in the blue sky before dissipating.

*

“Are you still sad, Uncle Rob?”

“I am sad. But I also understand your father. This journey has given me time to think.”

“What do you think?”

“I think that if people would lose their family, loved ones, close friends, that they would then be truly liberated. And then, they would be able to be, do, and act without any concern for themselves. I’m not talking about a selfish journey. I’m talking about a selfless journey. One where, should you choose, you could go into a country ravished by a disease, just to serve and help. You could drop everything and help the world.”

“Like you, Uncle Rob, helping me.”

“Mmm. I would do anything for you and my brother. There’re no excuses – there are none anyway. We just think that these people in our lives stop us and give us a reason not to do good in the world. Because most of the world are sitting behind a desk not contributing – being a cog isn’t contributing. It’s just making the machine bigger. I’m not saying you should wish that your loved ones die. I’m saying live like they aren’t stopping you from being a better person. Look at someone who has lost everything.”

“Like father?”

“Sort of. Give them time: either they’ll blow their brains out, fade into a shadow of their former selves, or they will take the world on, head on because what’s the worst that can happen? It has already happened to them. And dying is no longer something they worry about because that will be a relief when it comes.”

“Will father come back?”

“I don’t know.”

“Mom won’t.”

“No, she won’t.”

“Mom was lying on the floor. My head was sore and I couldn’t feel my right arm.” He wriggled his free, bruised shoulder. “I tried to remember the first aid we learned in class. I don’t think I did it right.”

“Your mom was already dead from the blast, my boy.”

“Yes, but I don’t think I did it right.”

“It’s not your fault your mother died. The bomb did it. They did it. Not you.”

They waited in silence.

A moment later he could feel the vibration of the solid concrete. It was coming.

He could now hear the air passing over his exposed ear. His body shuddered at the cold breeze.

“It’s all going to be okay, Joshua.”

He realised he was giving off a low hum on each outbreath.

“Relax and start your breathe-ups.”

He tried to steady his breathing but his cold muscles began shivering uncontrollably.

“Like diving underwater,” his uncle whispered.

“I can hold my breath for two minutes.”

“Yes you can, Josh.”

The icy air burned his nostrils as he took in a long deep breath.

“Breathe it in until your chest wants to burst, and hold it for fifteen seconds.”

He tried but his body shook it out.

“Try again. Just breathe normally until you relax.”

“What about the gas?”

“Focus on breathing. Don’t worry about the gas or the freighter. As soon as it passes you know the gas rises straight up to the ceiling and the air will come rushing in behind the freighter again.”

He could hear it now – metal on metal. At that moment he felt his eardrums pushing in, dulling any noise around him.

“Pop your ears while you can, Josh.”

With his free hand, he pinched his nose and gently compressed air in his nasal passages.

Only one ear cleared.

He tried again but his hand slipped. Warm snot slimed his fingers. He wiped it off and decided to brace himself with everything he had.

“Breathe,” his uncle said above the growing rumble.

The air around them was now a steady wind.

“In ten seconds you must listen to me and do what I do.”

He waited, breathing deep gulps of air.

“Now!”

He copied his uncle as he heard him take deep breaths and quick hissing exhales. He counted out the five and then knew he had to hold the final one.

This was it.

He gulped and held the last, chest-bursting breath.

And that’s when the storm hit them.

He felt the force press down on him, squeezing some of the air out of his nose. His muscles tightened around him, holding the concrete.

He didn’t have any urine left in him so he wasn’t worried about wetting himself this time.

The noise blasted out any sounds he might have been making. He knew his uncle was still there with him.

He let out some air to alleviate the pressure hurting his chest. The downward press began to subside and he knew this was the most crucial part, when the freighter began sucking; pulling you up from the ground.

He wished he could just let out his air and breathe.

He felt his free leg jolt off the ground and his body tightened. His uncle was heavier than he was, but they had to keep every muscle ready for any blast or pull from all directions. Anything to unsettle you.

His eyes were shut tight but he began to notice bursts of light in his peripheral vision. He couldn’t tell if the dizziness engulfing him was from the freighter or his own body trying to stay alive.

There was a burst of light and colour to his right. He opened his eyes with fright only to have dust sting them shut. Tears scratched ice-cold across his face.

Another burst of light.

“Uncle Rob?” he shouted.

“Just a little bit longer, Josh,” his uncle hissed through clenched teeth.

He held onto the remaining air he had left. He could feel the train pulling at him. It wasn’t going to be long now.

His body began to tingle. He could feel his fingertips gripped onto the concrete.

Another bright light, this time he could feel the warmth.

“Uncle Rob?” he shouted again, letting out his last bit of air. His body relaxed. “I think I can see the sun.”

“No, Josh. There is no sun.”

“I can see it.”

“Don’t let go!” his uncle screamed in the darkness.

About the Writer:

Stephen was born and lives in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. His background is Graphic Design, Creative Direction and Film. He completed the first draft of a Science Fiction novel in 2011 (Soul Searching) and his first short story published in 2015/16 in the “Imagine Africa 500” speculative fiction anthology, followed by more in the “Beneath This Skin” 2016 Edition of Aké Review, and “The Short Story is Dead, Long Live the Short Story! Vol.2”. He is a charter member of the African Speculative Fiction Society and its Nommo Awards initiative.

February 14, 2022

There is magic in African literature: Oxford Lecture Event 14 February 2022

“There is magic in African literature…”

– Stephen Embleton.

This past month at Oxford has been an extraordinary experience culminating (but not ending) last night with the event I was able to participate in.

The first part having Onyeka Nwelue open the event and then interview James Currey. Followed by Professor Miles Larmer introducing me for my lecture. “There is magic in African literature.” An odd experience knowing there were many watching remotely and sending through questions for the Q&A afterwards.

❤️📖📚🎤

February 3, 2022

Oxford Guest Lecture: Monday 14 February, 5:00pm

Oxford Guest Lecture: Monday 14 February, 5:00pm

I will be participating in this event, speaking on the legacy of the original African Writers Series and its ongoing impact on African literature – in all its genres.

https://www.africanstudies.ox.ac.uk/e...

Monday 14 February, 5:00pmInvestcorp Lecture Theatre, St Antony's College and online Top: James Currey and Onyeka Nwelue Bottom: Stephen Embleton

Top: James Currey and Onyeka Nwelue Bottom: Stephen Embleton

The Heinemann African Writers Series (AWS), which published 359 books between 1962 and 2003, published most of the works today recognised as the classics of African literature – novels, non-fiction, poems and short stories by (among many others) Chinua Achebe, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, Wole Soyinka and Sembène Ousmane.

This event celebrates the achievements of the AWS and its most important editor, James Currey, who went on to found James Currey, a leading Oxford-based publisher of non-fiction books. James will discuss the history of African publishing with Nigerian novelist Onyeka Nwelue, founder of the James Currey Society.

Stephen Embleton, the inaugural James Currey fellow and current academic visitor at the African Studies Centre, will speak on the subject of ‘The African Writers Series' Continuing Legacy: From Post-colonialism to Decolonialism’. He will be in discussion with ASC Director Miles Larmer on the future of African fiction, followed by a Question and Answer session. Please join us!