Jeremy T. Ringfield's Blog, page 445

June 18, 2024

Kurtenbach: There’s good, great, and then there was Willie Mays

San Francisco received the Giants in 1958, making the City by the Bay a big-league town.

But the real win for the city wasn’t taking the team.

It was acquiring the player.

By the time Willie Howard Mays arrived in California, he was already one of baseball’s finest — Rookie of the Year at 20 years old, MVP at 23, and a perennial All-Star.

He made all that seem quaint in his 2,095 games in San Francisco.

And in the process, he helped turn San Francisco — and the Bay Area as a whole — into an epicenter of professional sports for decades to come.

Mays not only played the game at the highest level, but he played with an effervescent charisma. He was impossible not to root for, and while the Giants weren’t the first pro team in town — the 49ers were founded in 1946 — it did make him San Francisco’s first true professional sports superstar.

It’s a debt the city and region would never be able to fully repay.

Mays might have been the single greatest baseball player — perhaps even the single greatest American-born athlete — who ever lived.

His gaudy statistics — he’s the only player in baseball history with a career .300-batting average, at least 3,000 hits, 300 stolen bases and 300 home runs — make a strong case for that superlative.

But it’s the testimonials of those who played with and against him — those who saw the incredible feats of his brilliant 23-year career — that make an even stronger argument.

“No record book reflects this kind of concentration, determination, perseverance, or ability. As a player, Willie Mays could never be captured by mere statistics,” legendary San Francisco newsman Harry Jupiter said of Mays.

Mays died Tuesday. The Say Hey Kid was 93 years old.

Mays lent his legitimacy to San Francisco and the Bay Area until the end. Born in Alabama and rising to prominence in New York, Mays embraced San Francisco, even if the city didn’t always embrace him.

And with so many of our sports stars’ stories littered with caveats, Mays’ reputation remained as sterling as his play.

Every town needs a first star. San Francisco couldn’t have landed a better one.

It’s fair to wonder if Joe Montana, Steph Curry, Barry Bonds, Rickey Henderson, or Patrick Marleau — amongst so many others — carve out roles as Bay Area pro sports legends if Mays didn’t come to San Francisco and pull more than a million fans a year to Seals Stadium and later Candlestick Park, rooting the team in town.

Luckily that’s merely a thought experiment. Theatre of the mind.

And, sadly, for folks of my generation, Mays’ incredible accomplishments on the field are also that. Sure, there are some highlights. And we all know “The Catch”. But few, if any, were able to experience the full depth of Mays’ talent — his day-to-day greatness.

But to hear others tell the story, it would seem as if the rules of hyperbole were suspended for No. 24.

There was good, and beyond that, great. Then there was Willie Mays.

Said Mays’ manager Leo Durocher:

“If somebody came up and hit .450, stole 100 bases, and performed a miracle in the field every day, I’d still look you right in the eye and tell you that Willie was better,”

The Catch: How Willie Mays explained his signature World Series play

In 1954, his first full season in the majors, Willie Mays established himself as a supernova. He won his first MVP award by hitting a league-leading .345 with 41 home runs and 110 RBIs.

Then, in Game 1 of the World Series against the heavily favored Cleveland Indians, he delivered the most famous defensive play in baseball history.

It became known as The Catch.

FILE- In this Sept. 29, 1954 file photo, New York Giants center fielder Willie Mays, running at top speed with his back to the plate, gets under a 450-foot blast off the bat of Cleveland Indians first baseman Vic Wertz to pull the ball down in front of the bleachers wall in the eighth inning of Game 1 of the World Series at the Polo Grounds in New York. In making the miraculous catch with two runners on base, Mays came within a step of crashing into the wall. The Giants won 5-2. (AP Photo, File)

FILE- In this Sept. 29, 1954 file photo, New York Giants center fielder Willie Mays, running at top speed with his back to the plate, gets under a 450-foot blast off the bat of Cleveland Indians first baseman Vic Wertz to pull the ball down in front of the bleachers wall in the eighth inning of Game 1 of the World Series at the Polo Grounds in New York. In making the miraculous catch with two runners on base, Mays came within a step of crashing into the wall. The Giants won 5-2. (AP Photo, File)With two runners on, nobody out, and the score tied 2-2 in the top of the eighth, the left-handed hitting Vic Wertz blasted a ball an estimated 460 feet to center field at the Polo Grounds. Turning his back to home plate, Mays sprinted toward the wall, caught the ball over his shoulder and whirled to deliver a powerful throw back to the infield.

Heralded as an all-time gem, Mays always insisted that the play was no big deal, with only a slight nod to his throw back to the infield.

“I was very cocky. When I say that, I mean that everything that went in the air, I thought I could catch. I was very aware of what was going on,” Mays said during a visit to AT&T Park in 2003. “When the ball was hit off Don Liddle, the pitcher, I’m saying to myself, ‘Two men are on.’ Yes, I’m talking to myself as I’m running — I know it’s hard to believe that I could do all this in one sequence.

Related ArticlesSan Francisco Giants | SF Giants, from one generation to the next, remember Willie Mays: ‘One of the true icons of the game’ San Francisco Giants | San Francisco Giants | Kurtenbach: There’s good, great, and then there was Willie Mays San Francisco Giants | Willie Mays draws tribute at Oakland Coliseum — site of his final hit San Francisco Giants | Sports world reacts to Mays’ death, from Barry Bonds to emotional KNBR radio call“As the ball is coming, I’m saying to myself, ‘I have to get this ball back into the infield.’ In my mind, I never thought I would miss the ball. I didn’t think that at all.

“When you watch the play, look at the way I catch the ball. It’s like a wide receiver catching a pass going down the sideline, which is over the left shoulder, on the right side. I had learned about that playing in high school.”

Larry Doby, who was at second base, scrambled to tag up and advanced only as far as third. Al Rosen remained at first. Neither runner wound up scoring, and the Giants won the game in extra innings to kick-start a four-game sweep.

It was the only World Series triumph of Mays’ career.

Amazingly, one of the most exciting plays in sports history owes its roots to boredom.

Mays missed most of the 1952 season and all of ’53, a total of 274 games, after being drafted into the Army during the Korean War.

He spent much of his military service in Fort Eustis, Virginia. It was there — to pass the time — that Mays first developed his signature basket catch. As he later recounted for author Steve Bitker in “The Original San Francisco Giants”:

“I had a lot of spare time and said, ‘Well, let me do something different for the fans.’ And when I came out of the Army, I just did it. … It was easy for me to catch that way. I thought Leo (Durocher) would be the one to say, ‘No.’ But he said, ‘As long as you don’t miss it, I don’t care how you catch it.’ ”

Dan Brown is a former Bay Area News Group sports reporter.

Willie Mays draws tribute at Oakland Coliseum — site of his final hit

OAKLAND — Players respectfully hustled out of the Oakland Coliseum dugouts, doffed their caps, and stoically joined a moment of silence Tuesday night for fallen baseball legend Willie Mays.

It was here, in this decaying stadium soon to be abandoned by the Athletics, that Mays delivered his last hit and finished patrolling centerfield in an unparalleled Hall of Fame career.

In Game 2 of the 1973 World Series, a 42-year-old Mays delivered a go-ahead RBI single up the middle off Rollie Fingers in the 12th inning, helping the New York Mets win 10-7 before a crowd of 49,151.

Tuesday night, only a couple thousand fans were scattered across the Coliseum’s lower two levels as the A’s opened their seventh-to-last homestand in Oakland, ahead of their eventual move to Las Vegas and three-year layover in Sacramento.

But a hush quickly engulfed the mostly empty stadium at twilight, as an image of “Willie Mays, 1931-2024” appeared on the blackened videoboards above the foul posts. Some 40 minutes earlier, Mays’ death (at age 93) was announced by the San Francisco Giants, the major-league organization he broke in with in New York in 1951, and for whom he brilliantly shined until a 1972 trade to the Mets.

“I was a kid growing up and I read a biography on Willie, and I just wish I was half the player he was,” A’s manager Mark Kotsay said. “The catches that he made, the smile that he had, the impact he had on the game of baseball — his loss is felt today and will be for a long time.”

A’s centerfielder J.J. Bleday said he was “100 percent” aware of Mays’ impact on baseball.

“I’m devastated for him and his family. The dude was an absolute legend, bigger than baseball,” Bleday said after Tuesday’s 7-5 win over the Royals. “I saw a picture in Tampa in the away locker room of him coming in with a bunch of bats, and it was the coolest picture I’ve ever seen. … Prayers for him and his family. He gave so much to the game and had an unbelievable life.”

Related ArticlesSan Francisco Giants | SF Giants, from one generation to the next, remember Willie Mays: ‘One of the true icons of the game’ San Francisco Giants | San Francisco Giants | Kurtenbach: There’s good, great, and then there was Willie Mays San Francisco Giants | The Catch: How Willie Mays explained his signature World Series play San Francisco Giants | Sports world reacts to Mays’ death, from Barry Bonds to emotional KNBR radio callMays appeared in 24 big-league ballparks over his major-league career — not to mention the other diamonds beforehand in the Negro Leagues and minors — but he never played a regular-season game in Oakland. Interleague play wasn’t introduced until 1997.

As Mays closed the final season of his career, the 24-time All-Star and 12-time Gold Glove winner came to Oakland for the 1973 World Series. He went 1-for-4 as the Mets dropped the opening game, 2-1. In Game 2, Mays entered as a ninth-inning pinch runner for Rusty Staub, and his go-ahead single ignited the Mets’ winning rally to even the series at 1-1; that game also marked the final time he put on his glove to patrol centerfield.

“Obviously there are a lot of great centerfielders but he was the pinnacle of it,” Kotsay said.

Mays’ final plate appearance came in Game 3 of the World Series at Shea Stadium, where he entered as a 10th-inning pinch-hitter for Tug McGraw and grounded out in the 3-2, 11-inning loss by the Mets. Mays did not remain in the game to play center field, as pitcher Harry Parker took Mays’ spot in the order. The A’s would prevail in seven games to capture their second of three consecutive World Series crowns.

Sports world reacts to Mays’ death, from Barry Bonds to emotional KNBR radio call

By The Associated Press

Reaction from the sports world and beyond to the death of baseball Hall of Famer Willie Mays. He died Tuesday at age 93, Mays family and the San Francisco Giants jointly announced. Mays’ electrifying combination of talent, drive and exuberance made him one of baseball’s greatest and most beloved players.

___

“I am beyond devastated and overcome with emotion. I have no words to describe what you mean to me — you helped shape me to be who I am today. Thank you for being my Godfather and always being there. Give my dad a big hug for me. Rest in peace Willie. I love you forever. #SayHey” — Former hitter and Mays’ godson Barry Bonds.

___

“His incredible achievements and statistics do not begin to describe the awe that came with watching Willie Mays dominate the game in every way imaginable. We will never forget this true Giant on and off the field.” — MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred.

___

“RIP Willie Mays. You changed the game forever and inspired kids like me to chase our dream. Thank you for everything that you did on and off the field. Always in our hearts.” — Former pitcher CC Sabathia.

Dave Flemming was in the visitors' radio booth at Wrigley Field the moment the report of Willie Mays' passing was made public.

Here's what it sounded like on our airwaves as he passed on the news to Giants fans everywhere. pic.twitter.com/pf5lK921z9

— KNBR (@KNBR) June 19, 2024

“I’m having a hard time saying the words, but we found out just a little while ago, and the Giants have now made an announcement … the all-time greatest Giant, No. 24 Willie Mays, has passed away at the age of 93. Right as we get ready to head to his hometown and honor the great Willie Mays, we have to say goodbye.” — Dave Flemming, Giants play-by-play announcer on KNBR.

___

“I’m devastated to hear about the passing of the legendary Hall of Famer Willie Mays, one of the main reasons I fell in love with baseball. Cookie and I are praying for his family, friends, and fans during this difficult time.” — NBA Hall of Famer Magic Johnson.

___

“The great Willie Mays has passed away. It was a privilege to know him. We were both honored by @MLB in 2010 with the Beacon Award, given to civil rights pioneers. He was a such a kind soul, who gifted my brother Randy a new glove and a television during his rookie year with the @SFGiants. My deepest condolences to his family. He will be missed.” — Tennis legend Billie Jean King.

___

“Willie ended his Hall of Fame career in Queens and was a key piece to the 1973 NL championship team. Mays played with a style and grace like no one else. Alex and I were thrilled to honor a previous promise from Joan Payson to retire his iconic #24 as a member of the Mets in 2022. On behalf of our entire organization, we send our thoughts and prayers to Willie’s family and friends.” — Mets owners Steve and Alex Cohen.

Willie Mays’ passing is announced to the Rickwood Field crowd, and rising as one, it salutes the Alabama native and former Birmingham Black Baron. pic.twitter.com/e2EHJT1udb

— Sam Dykstra (@SamDykstraMiLB) June 19, 2024

___

“From his professional debut with the Birmingham Black Barons at age 17 through his 24 All-Star Games to his Hall of Fame induction in 1979, Willie’s skill on the field and impact off it elevated him to a stature that was larger than life.” — MLB Players Association Executive Director Tony Clark.

___

Related ArticlesSan Francisco Giants | SF Giants, from one generation to the next, remember Willie Mays: ‘One of the true icons of the game’ San Francisco Giants | San Francisco Giants | Kurtenbach: There’s good, great, and then there was Willie Mays San Francisco Giants | The Catch: How Willie Mays explained his signature World Series play San Francisco Giants | Willie Mays draws tribute at Oakland Coliseum — site of his final hit“The great Willie Mays has passed away. Had the honor of talking with him several times. He loved that we mentioned his ’54 World Series catch in City Slickers. The man who hit the ball and the “ Giant” who caught it signed this ball. RIP #24.. a thrill to watch you play.” — Actor Billy Crystal.

___

“Best player I’ve ever seen. Greatest player. I fortunately grew up in the Bay Area during Mays’ prime, and he was a five-tool player, an extraordinarily good five-tool player. You’d go to a game and he would do something. Whether it would be a great catch, a great throw, a stolen base, hit a home run or he’d do them all. He was just that kind of player. … What always came off was that he was the ‘Say Hey Kid.’ He had that ebullient personality. Infectious and genuine, and I got to tell him he was the greatest player I ever saw.” — Former player Keith Hernandez.

___

AP MLB: https://apnews.com/MLB

Purdy: Was Willie Mays the best baseball player ever? He was simply the best

I do not know conclusively if Willie Mays was the greatest baseball player of all time.

I do know that Mays, before his death Tuesday ay 93, never felt as insecure about that label as Joe DiMaggio did. After DiMaggio’s retirement from the playing field, whenever he made a personal appearance, his contract mandated that he be introduced as “the greatest living baseball player.” Mays never did anything like that. But with Mays, such a stipulation would have been superfluous. The entire world understood that Mays was the best. Just the best.

I do not know what Mays thought about DiMaggio — or what Mays thought about much else, really. Mays could be an unpredictable fellow. When asking him a question, you never quite knew what you’d get.

Sometimes, the answer would be direct. Sometimes, Mays would do a conversational jitterbug. It’s probably why he never became a manager or television voice. But he was always pure Willie Mays.

I do know that when Mays did speak unpredictably, he was always unpredictably sincere. I remember the day that McCovey Cove was dedicated outside Oracle Park — in honor of former Giants player Willie McCovey — and Mays was not scheduled to speak on the program. But literally at the last second, Mays decided to jump up and talk about his onetime teammate. He gave a disconnected, funny and touching speech that (I think) delineated his pride in just knowing McCovey as both a man and a Giant.

I do know that Mays was a baseball genius. The shame is that he played in an era when every game was not televised or filmed. I wish that more television highlights existed of the great plays he made. We have seen the clip of his 1954 World Series basket catch . . . what, maybe a million times? We’ve never been able to see so many other stunning holy-moly fantastic grabs and baserunning plays.

I do know that Mays was a prodigy and fierce competitor, right from the start. He supposedly learned to walk by chasing a baseball his dad rolled across the floor of the family home in rural Alabama. And back in the late 1940s, Mays was a high school junior when he was recruited by the Negro League team one state away in Chattanooga. One afternoon in Memphis, Mays was rounding third base and the opposing catcher blocked the plate. Mays went in high. He ripped the catcher’s pants from crotch to knees. Said the Chattanooga manager, Piper Davis: “After that, nobody tried to block the plate on Willie Mays.”

I do know that because of his rural Southern upbringing, Mays was an unlikely candidate to earn the love and respect of sports fans in Manhattan. But they couldn’t help loving him when they saw Mays in a Giants uniform, performing at a different speed and intensity than anyone else in the entire city, at a time when New York was home to three major league teams.

I do not know how history would have been different if the Giants had never relocated to San Francisco for the 1958 season. But I do believe Mays would have finished with more than 660 career home runs — because several dozen potential home runs were slammed back into the field of play by Candlestick Park’s ridiculous winds.

I do know one thing that people have forgotten about that day in 1965 when Giants pitcher Juan Marichal struck Los Angeles Dodgers catcher John Roseboro with a bat, sparking a vicious brawl. In that altercation, Mays held back Roseboro as emotions turned the contest into a cauldron of passion. And then Mays hit the winning home run. If that’s not the definition of a team leader, I don’t know what is.

I do know how Mays, as a human being, tried to help O.J. Simpson when Simpson was a troublemaking kid living in the San Francisco housing projects on Potrero Hill. Mays heard about the young kid with so much athletic promise and drove his luxury car there to pick up Simpson and spend the day with him, showing the kid how well a professional athlete could live if he fulfilled his potential and kept his nose clean. Simpson cited that day as a turning point in his childhood. If only the lessons had stuck with Simpson for his entire life.

I do not know if Mays was the best athlete in American sports history, in addition to being the best baseball player. But I do know what Jerry Krause, the former Chicago Bulls general manager, once said: “If Willie Mays had played only basketball from the time he was 8 years old, he’d have been Michael Jordan. And if Michael Jordan had played only baseball, he’d have been Willie Mays.”

I do know that even in Mays’ later years as his legs were betraying him, he could still summon enough speed to do damage. In 1966 on a bad wheel, he scored all the way from first base on a single to beat the Dodgers in a late September road game. Mays explained afterward: “We had a plane to catch and it was time to get it over with.”

I do not know how fair it was in 1979 when Bowie Kuhn, then baseball’s commissioner, suspended Mays from baseball after he accepted a job as “assistant to the president” of Bally’s Park Place casino in Atlantic City — essentially a glad-handing job, for just 10 days a month. I do know what singer Frank Sinatra said about the whole thing: “Mr. Kuhn told Willie Mays to get out of baseball. I would like to offer the same advice to Mr. Kuhn.”

I do know that when the Giants decided to build their new ballpark and erect a statue at 24 Willie Mays Plaza, everyone in the Bay Area had the same reaction at the same time: “Of course.”

I do know that over the last several years, as Mays struggled with his eyesight and other physical problems, it was difficult for him to spend as much time at 24 Willie Mays Plaza as he once did. And that has been melancholy to contemplate. But each time he did make it to the ballpark, no one received more respect or more applause. The statue is not going away. Neither are the stories.

I do not know how Mays will be remembered in 50 or 100 years. I do know that right here, right now, in the wake of his passing, there is only one way to remember him.

As the best.

— Mark Purdy was a Mercury News sports columnist from 1984-2017.

Willie Mays obituary: “Say Hey Kid” captured the imagination of fans with both his bat and glove

Willie Mays could run, hit, field and throw and did all of it with the flair of a master showman. The “Say Hey Kid” may have tormented opponents, but he played with a smile that retained its boyishness into old age.

“I’m not sure what the hell ‘charisma’ is,’’ Cincinnati Reds first baseman Ted Kluszewski once said, “but I get the feeling it’s Willie Mays.”

Mays, the incandescent Giants outfielder and a symbol of baseball’s golden age, died Tuesday. He was 93.

With his exhilarating blend of power and speed, the Hall of Famer smashed 660 career home runs (sixth best all-time), tallied 3,283 hits (12th) and won four stolen base titles.

He made 24 All-Star Games, captured two MVP awards and won 12 Gold Glove awards for fielding excellence.

But looking at Mays through statistics is like measuring an artist by the dimensions of the canvas. His story is told in images: An over-the-shoulder catch at the Polo Grounds. A blur of legs churning from first to third on a single. A cap flying away as he glided across the outfield.

Mays could do almost everything.

“If he could cook, I’d marry him,” said Leo Durocher, his first manager.

Mays played in the majors for 22 seasons (1951-73), primarily for the Giants — first in New York and later in San Francisco.

Bay Area fans were initially cool to the New York import when the team moved West in ‘58. Local fans tended to gravitate more toward homegrown stars like Willie McCovey and Orlando Cepeda. But in the end, Mays proved impossible to resist.

“The line I always used to describe him was: Willie Mays was the happiest guy in the world to be Willie Mays,” the late broadcaster Lon Simmons once said. “That’s what he wanted to be: He wanted to be Willie Mays.”

The Giants created an address in his honor — 24 Willie Mays Plaza — when they built AT&T Park in 2000. A statue depicting his powerful swing greets millions of fans a year.

The real Mays, meanwhile, also became a fixture at the ballpark over his final decades of life. The Giants hired him as a special assistant to the president, but he was essentially paid to be Willie Mays. He regaled listeners, including awestruck current players, with tales about the Negro Leagues or facing Sandy Koufax or how he made his famous over-the-shoulder catch at the Polo Grounds in 1954. Mays also provided brilliant baseball tips to anyone brave enough to ask, a service available to the front office as well. (Mays took credit for endorsing the team’s interest in drafting a Florida State catcher named Buster Posey in 2008).

Along the way, Mays laughed easily and chattered constantly, just like he did while playing stickball on the streets of Harlem, which he often did after games at the Polo Grounds.

But for all of Mays’ speed, power and grace, rival executive Branch Rickey once said the player’s greatest attribute was actually “the frivolity in his bloodstream that doubles his strength with laughter.”

THE EARLY DAYS

Born on May 6, 1931, in Westfield, Alabama., Mays showed rare athletic gifts almost from the crib. His father, Willie Howard Mays Sr., worked as a railroad porter and also swept floors at the local steel mill, where he was a star on the company baseball team. Willie’s mother, Annie Satterwhite, was a standout in both track and basketball. (Willie Sr. and Annie never married.)

By the time he was 5, Mays would play catch with his father on the farmland near their home. Willie Sr. taught his son each position, one-by-one starting with catcher, and told him that he could boost his value by honing every skill available to a ballplayer.

Mays was a prodigious talent in whatever sport he tried. He was a rocket-armed quarterback and a sharpshooting forward for Fairfield Industrial High School. But the teenager concluded that his compact frame (5-foot-11, 170 pounds) was best-suited to the diamond.

He signed to play for the Birmingham Black Barons in 1948, when he was 17. Mays played three seasons in the Negro Leagues, where he learned to play with a zest capable of attracting large crowds. This was also where Mays mastered the art of turning a deaf ear to the immense prejudice he encountered from the segregated South. He never reacted to taunts from the stands, nor was he rankled when he was forced to stay in a hotel separate from his white minor league teammates.

“Positive thinking allowed me to look past whatever was happening,” Mays once said. “If you can overcome your pain and do your job, the pain disappears the next day.”

WELCOME TO THE BIG LEAGUES

The New York Giants outmaneuvered a growing parade of scouts to sign the 19-year-old wunderkind in June of 1950. They did so largely on the advice of San Francisco-born scout Eddie Montague, who told his bosses: “You better send somebody down here with a barrelful of money and grab this kid.”

The Giants pounced, landing the future Hall of Famer with an offer of $5,000.

The do-everything center fielder made short work of the minor leagues, starting the 1951 season by batting .477 over 35 games for the Minneapolis Millers of the Triple-A American Association.

Mays was at a movie theater in Sioux City, Iowa, when the projectionist stopped the film to make an announcement. “If Willie Mays is in the audience,” a man asked, “would he please report immediately to his manager at the hotel.” He was being summoned to the big leagues.

Mays was 20 years old when he made his debut on May 25, 1951, the third African-American to play for the Giants, following Hank Thompson and Monte Irvin. He had only one hit in his first 26 at-bats, but the lone hit was a titanic homer off future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn.

“I’ll never forgive myself,” Spahn later quipped. “We might have gotten rid of Willie forever if I’d only struck him out.”

That homer aside, Mays continued to struggle against everyone else. Giants coach Herman Franks finally noticed the kid crying in front of his locker after a game. He alerted Durocher by telling him: “You better go down and see your boy.”

Durocher sidled up to the disconsolate Mays and draped a fatherly arm over his shoulder. “As long as I’m the manager of the Giants, you’re my center fielder,” Durocher told him. “Tomorrow, next week, next month. You’re here to stay. With your talent, you’re going to get plenty of hits.”

The next day, Mays drilled a single and a 400-foot triple to right-center field, signaling the true arrival of a baseball prodigy.

Mays would go on to win rookie of the year honors while help the Giants overcome a 13-game deficit to catch the Brooklyn Dodgers. Mays was on-deck when Bobby Thomson hit the so-called “Shot Heard ’Round the World,” a three-run homer to give the Giants the pennant.

The Giants lost that ’51 World Series to the Yankees. Those six games marked the only time Mays and the aging Joe DiMaggio played on the same field.

MOVING TO S.F.

The Giants franchise migrated to San Francisco in ’58, a blow to Mays, who adored New York City. Mays once described his reaction to relocation as “more sadness than anything.”

He alienated some San Francisco fans with such frequent reminiscing about his New York days. At the end of 1958, fans responding to a newspaper poll voted rookie Cepeda the team’s MVP, even though Mays led the team in almost every offensive category.

The wall eroded over time, thanks to one impossible feat after another. On April 30, 1961, he showed up for a game in Milwaukee feeling queasy after eating some bad ribs. He begged out of the lineup, but reconsidered after powering a few long balls in batting practice. Mays also had a chat with infielder Joe Amalfitano.

“I asked him, ‘What are you from 1 percent to 100 percent?’ He said, ‘Maybe 70,’’’ former Amalfitano later recalled. “I said, ‘Well, your 70 is going to be better than whoever goes out there for their 100.’ “

Mays marched back into the clubhouse and wrote his name on the lineup card, hitting third. He proceeded to go 4 for 5 with four home runs and 8 RBIs, the most prolific day of his career. His only out was a ball caught at the center field wall by Hank Aaron.

A year later, Mays helped lead San Francisco to its first World Series in 1962 by hitting .304 with 49 home runs and 141 RBI.

The Giants lost that fall classic in a memorable showdown with the New York Yankees. Matty Alou was at third base and Mays was at second base when McCovey lined out to second baseman Bobby Richardson to end a 1-0 loss in Game 7.

In the aftermath of that narrow defeat, a reporter wondered if Mays would have actually had time to score the winning run, considering how hard McCovey had blistered the ball.

“By the time they got the ball home,’’ Dark snapped, “Mays would have been dressed.”

THE WINDS OF CANDLESTICK

Mays never reached another World Series with San Francisco but continued to put up terrific seasons amid the blustery conditions of Candlestick Park. In a move typical of his baseball savvy, Mays recognized that the swing he’d once used at the Polo Grounds, where the left-field fence was only 277 feet away, was no longer as potent at the ‘Stick, where the wind blew in from left.

So Mays reconfigured his swing path to aim another direction. By the time he was done, Mays estimated that 80 to 90 percent of his home runs at Candlestick Park went to right-center.

Simmons, his friend and longtime broadcaster, said the adjustment illustrated Mays’ genius-level baseball IQ.

“Mays was not the fastest guy in baseball, but he was the quickest to react,’’ Simmons said. “Go to a game now and watch how long it takes a runner to react on a wild pitch — there are times when it’s practically to the backstop. Willie was gone before that ball passed home plate.”

Simmons also noted that Mays would often stop at first base on a potential double because doing so prevented opponents from issuing an intentional walk to the dangerous McCovey hitting behind him.

Other players swore that said Mays would intentionally flail on a hittable curveball as a way of tricking the pitcher into throwing him that same pitch later in a crucial situation. It was said Mays didn’t need coaches while running the bases, because he was always aware of where each outfielder was positioned.

“You talk to Willie Mays for 5 minutes and I guarantee you he’ll bring up something you’ve never thought of about the game,’’ former Giants outfielder Carl Boles said in a 2012 interview.

Mays had 17 seasons with at least 20 home runs. He twice topped the 50 mark – and did so 10 years apart (in 1955 and again in ‘65).

As a testament to his all-around skills, Mays was the first National League player to reach the 30-30 mark (homers and stolen bases) and the first in either league to reach 30-30 in consecutive seasons (1956-57).

Even his fellow ballplayers were in awe.

“You used to think that if the score was 5-0, he’d hit a five-run homer,’’ Reggie Jackson said.

“He amazed me every single day,’’ Cepeda said.

Mays remains the Giants franchise all-time leader in runs, hits, doubles, home runs and total bases — marks threatened, but not surpassed by, his godson, Barry Bonds. He also ranks second in triples, RBI and OPS.

“I’ve always said Willie was the greatest player I ever saw,” said Mike McCormick, the longtime Giants pitcher and ’67 Cy Young Award winner. “He’d hurt you offensively and, defensively, I can’t even recall a favorite catch: he made too many.”

BACK TO NEW YORK

After the 1971 season, Mays lobbied owner Horace Stoneham for a 10-year contract so that he could finish his playing career in San Francisco and remain in the organization.

Instead, Stoneham decided he could no longer afford the fading 41-year-old and traded Mays to the New York Mets on May 11, 1972. In return, the Giants received forgettable pitcher Charlie Williams and $50,000.

His career ended with ’73 World Series against the A’s. (Mays is the only player to play in Fall Classic at both 20-or-younger and 40-or-over).The image of the once-graceful outfielder slipping in pursuit of Deron Johnson’s double during that series became a cautionary tale for athletes who play beyond their expiration date.

But Mays always rankled at the charge. Years later, he told KCBS sportscaster Steve Bitker: “They said, ‘Well, look at the old man falling down.’ But anybody could have slipped. It was a wet field. … That was one of my big disappointments, when writers can criticize a guy that slips.”

Forgotten, Mays pointed out, was that he drove in the game-winning run in the 12th inning of Game 2, the penultimate game of his career. “They didn’t write too much about that,’’ he said.

ENSHRINED IN COOPERSTOWN

Mays was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1979, receiving 94.6 percent of the vote.

After years adrift, he was embraced back into the Giants fold for for good when former owner Peter Magowan signed Mays to a lifetime contract in 1993. The Hall of Famer would tutor young players or regale them in his high-pitched voice with tales of jousting with Mickey Mantle in the All-Star game. He remained boyish into his 80s — the Say Hey Octogenarian.

In 2014, a few days before Giants outfielder Michael Morse hit a crucial pinch hit home run against St. Louis in the playoffs, Mays scribbled out a few batting tips on a sheet of paper. “And all I could think about,’’ Morse said, “was saving the piece of paper.”

Mays’s statistics have held up well over time, despite the fact that he missed about 266 games due to military service from 1952-53. His home run total ranks behind Barry Bonds, Hank Aaron, Babe Ruth, Alex Rodriguez and Albert Pujols.

As Mays himself put it in 1979: “I think I was the best player I ever saw.”

Mays was at his best in the annual showcase of baseball’s elite. He holds All-Star Game records for runs (20), hits (23), stolen bases (six), at-bats (75) and was twice selected as the game’s MVP.

“They invented the All-Star Game for Willie Mays,” Ted Williams once said.

On Nov. 24, 2015, Mays was honored at the White House with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. It is the nation’s highest civilian award.

This obituary was written in 2017 by former Bay Area News Group staff writer Daniel Brown

SF Giants legend, MLB Hall of Famer Willie Mays dies at 93 years old

CHICAGO — The man deemed by many to be the greatest baseball player to have ever lived, a player more deeply ingrained in San Francisco Giants history than any other, died Tuesday at the age 93, days before his formative club was set to honor him in his hometown.

Mays passed away peacefully, according to the Giants, who announced the news in the fifth inning of their game against the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field, where Mays played more games than any setting besides Candlestick Park and the Polo Grounds.

“My father has passed away peacefully and among loved ones,” said his son, Michael Mays, in a release from the club. “I want to thank you all from the bottom of my broken heart for the unwavering love you have shown him over the years. You have been his life’s blood.”

[ READ MORE: Bob Melvin, Bruce Bochy share their favorite Willie Mays memories ]

Mays, who followed the Giants from New York to San Francisco and played 21 of his 23 major-league seasons for the organization, was inducted into the Hall of Fame the first time he appeared on the ballot in 1979 and has since kept strong ties to the organization, making frequent visits to spring training, Candlestick Park and Oracle Park.

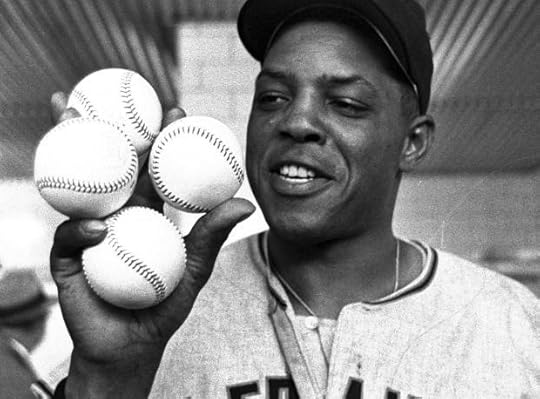

San Francisco Giants outfielder Willie Mays displays the four baseballs in the clubhouse representing the four homers which he hit against the Milwaukee Braves, April 30, 1961, in Milwaukee. Mays, the electrifying “Say Hey Kid” whose singular combination of talent, drive and exuberance made him one of baseball’s greatest and most beloved players, has died. He was 93. Mays’ family and the San Francisco Giants jointly announced Tuesday night, June 18, 2024, he had “passed away peacefully” Tuesday afternoon surrounded by loved ones. (AP Photo, File)

San Francisco Giants outfielder Willie Mays displays the four baseballs in the clubhouse representing the four homers which he hit against the Milwaukee Braves, April 30, 1961, in Milwaukee. Mays, the electrifying “Say Hey Kid” whose singular combination of talent, drive and exuberance made him one of baseball’s greatest and most beloved players, has died. He was 93. Mays’ family and the San Francisco Giants jointly announced Tuesday night, June 18, 2024, he had “passed away peacefully” Tuesday afternoon surrounded by loved ones. (AP Photo, File)“Today we have lost a true legend,” Giants Chairman Greg Johnson said in a statement. “In the pantheon of baseball greats, Willie Mays’ combination of tremendous talent, keen intellect, showmanship, and boundless joy set him apart. A 24-time All-Star, the Say Hey Kid is the ultimate Forever Giant. He had a profound influence not only on the game of baseball, but on the fabric of America. He was an inspiration and a hero who will be forever remembered and deeply missed.”

Born in Westfield, Alabama, Mays made his professional debut at 16 years old in 1948 for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League, where he played for three seasons before the Giants purchased his contract in 1950. He went on to win Rookie of the Year in 1951 and Most Valuable Player in 1954 and 1965.

[ READ MORE: Mays forever a Giant, but his roots were in Birmingham ]

Citing his health, Mays said earlier this week that he wasn’t going to be able to make it to Birmingham for the Giants’ game at Rickwood Field but that “Rickwood’s been part of my life for all my life. Since I was a kid.

“It was just ‘around the corner there’ from Fairfield (where Mays grew up), and it felt like it had been there forever. Like a church. The first big thing I ever put my mind to was to play at Rickwood Field. It wasn’t a dream. It was something I was going to do. …

“I’m glad that the Giants, Cardinals and MLB are doing this, letting everyone see pro ball at Rickwood Field. Good to remind people of all the great ball that has been played there, and all the players. All these years and it is still here. So am I. How about that?”

Mays’ 660 home runs ranked third all-time until 2003 when his godson, Barry Bonds, passed him.

Perhaps no one play in the pantheon of baseball is as iconic as Mays’ over-the-shoulder bucket catch in Game 1 of the 1954 World Series.

Running at top speed with his back to the plate, New York Giants center fielder Willie Mays gets under a 450-foot blast off the bat of Cleveland first baseman Vic Wertz to pull the ball down in front of the bleachers wall in the eighth inning of the World Series opener at the Polo Grounds in New York on Sept. 29, 1954. In making the miraculous catch with two runners on base, Willie came within a step of crashing into the wall. The Giants won 5-2. (AP Photo)

Running at top speed with his back to the plate, New York Giants center fielder Willie Mays gets under a 450-foot blast off the bat of Cleveland first baseman Vic Wertz to pull the ball down in front of the bleachers wall in the eighth inning of the World Series opener at the Polo Grounds in New York on Sept. 29, 1954. In making the miraculous catch with two runners on base, Willie came within a step of crashing into the wall. The Giants won 5-2. (AP Photo)His power swing, tremendous defense and exuberance for the game inspired countless young fans, including Giants manager and Bay Area native Bob Melvin.

“He probably inspired me to play baseball and like it as much as I did,” Melvin said this week. “I was a huge Willie Mays fan.”

“I fell in love with baseball because of Willie, plain and simple,” added Giants President and Chief Executive Officer Larry Baer in a statement. “My childhood was defined by going to Candlestick with my dad, watching Willie patrol centerfield with grace and the ultimate athleticism. Over the past 30 years, working with Willie and seeing firsthand his zest for life and unbridled passion for giving to young players and kids, has been one of the joys of my life.”

Mays’ legacy spans from coast to coast and everywhere in between.

Living in an apartment building adjacent to the site of the old Polo Grounds, Mays played stickball in the street with neighboring kids before heading over to the ballpark later in the evening, and he can take primary credit for the swath of Giants fans who remain in New York more than half a century since the team moved west.

It would be difficult to find a city and an athlete more closely tied than Mays and San Francisco, but his tenure in the city he would eventually call home for the rest of his life got off to a rocky start when, upon the Giants’ move in 1958, he was denied the house he sought to purchase by a racist zoning policy.

Mays would eventually be allowed to move into the property, and his star power raised attention to the issue. By 1963, California had passed the Rumford Fair Housing Act, and in 1968, discriminatory zoning was outlawed nationwide.

“It all went back to Willie Mays,” said Dr. Harry Edwards, professor emeritus of sociology at UC Berkeley.

His statue now stands in the plaza named after him outside the home plate gate of the Giants’ home park. He has a cable car — No. 24 — dedicated in his honor.

In 2015, he was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor, by President Barack Obama.

Related ArticlesSan Francisco Giants | SF Giants, from one generation to the next, remember Willie Mays: ‘One of the true icons of the game’ San Francisco Giants | San Francisco Giants | Kurtenbach: There’s good, great, and then there was Willie Mays San Francisco Giants | The Catch: How Willie Mays explained his signature World Series play San Francisco Giants | Willie Mays draws tribute at Oakland Coliseum — site of his final hitDecades earlier, all that mattered to Mays were athletics and academics.

Making his professional debut for the Black Barons at 16 years old in 1948, Mays suited up only on Sundays, when he wasn’t in class. A multi-sport athlete, baseball was Mays’ third-best sport, according to accounts from his youth, helping Fairfield Industrial High School to a football state title and starring on its basketball team.

At Rickwood Field, a short drive from Mays’ childhood home, his passing was announced during the minor-league game between the Birmingham Barons and Montgomery Biscuits that was part of the week’s festivities intended to highlight Mays and the scores of future Hall of Famers who treaded its grounds.

At Wrigley Field, where the Giants were playing when Mays passed, he enjoyed as much success as anywhere else. Playing 179 games here, Mays slugged 57 home runs, 39 doubles and 11 triples while batting .342 with a 1.077 OPS.

His name and image appeared on the outfield scoreboards in the middle of the sixth inning for the final time, and the Wrigley Field public address announcer informed the 36,297 on hand of the news. After a brief moment of silence, a familiar tune began to play over the stadium speakers.

Say hey, say who? Say, Willie, swinging at the plate. Say hey, say who? Say, Willie, that Giants kid is great.

Fans stand for a moment of silence for former MLB player Willie Mays during the sixth inning of a baseball game between the San Francisco Giants and the Chicago Cubs in Chicago, Tuesday, June 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh)

Fans stand for a moment of silence for former MLB player Willie Mays during the sixth inning of a baseball game between the San Francisco Giants and the Chicago Cubs in Chicago, Tuesday, June 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh)

Horoscopes June 18, 2024: Blake Shelton, follow your heart

CELEBRITIES BORN ON THIS DAY: Blake Shelton, 48; Carol Kane, 72; Isabella Rossellini, 72; Paul McCartney, 82.

Happy Birthday: Spend time with people of interest, and discover what options are available to you. There is a shift in how you think and what you want to do next, which can lead to an opportunity to awaken your senses and help yourself find your purpose in life. Don’t deny yourself the chance to try something new. Follow your heart. Don’t give anyone the right to pressure you or choose for you. Your numbers are 6, 13, 18, 24, 27, 38, 45.

ARIES (March 21-April 19): Think before you act or speak in order to avoid a rift with someone close to you. Laugh at your mistakes, and be willing to compromise and learn something from the experiences you encounter. Don’t be fooled by scams or someone trying to sell you something. 3 stars

TAURUS (April 20-May 20): Use your energy wisely. Take advantage of any opportunity that brings you closer to someone you love. Your attitude will determine how well you do personally and professionally. Awareness and kindness will help you get the most out of your day. A change will lift your spirits. 3 stars

GEMINI (May 21-June 20): Reflect and review your financial situation. Add to your skills and qualifications if doing so will help you perform more efficiently. Don’t follow the crowd when it’s you who needs to feel satisfied. Take matters into your own hands and choose what excites you most. 3 stars

CANCER (June 21-July 22): Participation will connect you to someone or something that can help you advance. Having discipline and the courage to act will prompt you to make a move that leads to a financial or health improvement. Trust your instincts. 5 stars

LEO (July 23-Aug. 22): Balance is necessary to come out on top. Refuse to let anyone talk you into doing something you don’t want. Look for opportunities, and take positive action to ensure you complete responsibilities and have a little time for yourself. 2 stars

VIRGO (Aug. 23-Sept. 22): Your happiness is your responsibility. Consider what you need and want. A change that offers contentment or a chance to fulfill a dream or goal will build confidence and the desire to live life your way. Put your heart and soul into something. 4 stars

LIBRA (Sept. 23-Oct. 22): Take more time to plan your next project or purchase. Preparation is vital if you want to turn your desires into an opportunity instead of a loss. Don’t let anyone decide for you or talk you into something you don’t need. 3 stars

SCORPIO (Oct. 23-Nov. 21): Embrace something that moves and enthuses you. Put your mind to work and bring your physical skills on board to help you reach your goal. Make a change that will encourage you to enjoy life more and to head down a path that enriches your life. 3 stars

SAGITTARIUS (Nov. 22-Dec. 21): Do what comes naturally. Refuse to get involved in someone else’s goal if it will take you away from what’s important to you. Be true to yourself and embrace the opportunities that resonate with you mentally, physically and financially. 3 stars

CAPRICORN (Dec. 22-Jan. 19): Stick to the truth and avoid the consequences. Putting your energy where it counts will have the biggest and best influence on your health and emotional well-being. A change at home will positively impact your relationships. 4 stars

AQUARIUS (Jan. 20-Feb. 18): A domestic change that allows you space and time to pursue something that brings you joy will be uplifting and build self-confidence. Choose to give your energy a physical outlet, and you’ll avoid a mental battle with someone you love. Simplicity, compromise and intelligence will pay off. 2 stars

PISCES (Feb. 19-March 20): Use your imagination, and you’ll devise a plan that saves or makes you money. A move will lead to an unexpected opportunity and information that will help you thrive as you move forward. Use your power of persuasion to get others on board with your plans. 5 stars

Birthday Baby: You are charming, persuasive and engaging. You are perceptive and imaginative.

1 star: Avoid conflicts; work behind the scenes. 2 stars: You can accomplish, but don’t rely on others. 3 stars: Focus and you’ll reach your goals. 4 stars: Aim high; start new projects. 5 stars: Nothing can stop you; go for gold.

Visit Eugenialast.com, or join Eugenia on Twitter/Facebook/LinkedIn.

Want a link to your daily horoscope delivered directly to your inbox each weekday morning? Sign up for our free Coffee Break newsletter at mercurynews.com/newsletters or eastbaytimes.com/newsletters.

June 17, 2024

After Melvin’s ejection, SF Giants rally to beat Cubs with Estrada’s big blast

CHICAGO — The batting cages at Wrigley Field are down one set of stairs, around a corner and past another, longer staircase. To reach the manager’s office requires a climb up another set of stairs, 49 steps, and a march through the cramped clubhouse quarters.

The former is where Bob Melvin spoke his team’s late-inning theatrics into existence hours before first pitch Monday, and the latter where he was forced to observe after being ejected from the game in the eighth inning, just before the most thrilling moments of the Giants’ 7-6 win to begin their three-game series against the Cubs.

“I caught a glimpse of it,” the manager said with a glimmer.

By the time Thairo Estrada launched the first pitch he saw from Hector Neris in the top of the ninth inning into the left field bleachers, Melvin had seen the two teams trade leads five times, slug four home runs and strand 18 runners on base before being tossed arguing balls and strikes for the third time this season.

Given the circumstances, Estrada crossed home plate gleaming after his three-run blast landed on the other side of the ivy in left field — the fifth home run of the final four innings — and put the Giants ahead for good in this back-and-forth affair. It followed solo shots from Patrick Bailey and Heliot Ramos that pulled them within striking distance.

Asked if he had hit a more consequential home run in his six-year career, Estrada responded in Spanish, “You guessed it. I haven’t hit a bigger home run than the one I hit today.

“I was very positive today. I showed up. Put the batting gloves on. Got myself mentally ready. And I just had this feeling that something big was going to happen for me today.”

The Giants were trailing 6-4 when Melvin was tossed by home plate umpire Manny Gonzalez in the middle of the eighth inning. They got five scoreless innings from their starter, Jordan Hicks, but the two arms available in their bullpen — rookies Randy Rodriguez and Erik Miller — combined to allow six runs on a pair of home runs.

The outcome risked mirroring the last game the Giants’ lost, when they allowed the Angels to score the final three runs of a 4-3 loss Saturday.

That tough loss, done in by a game-tying home run in the sixth inning and a game-changing error the next inning, helped fuel a comeback only two days later.

“We talked a little bit about it in the hitters’ meeting today,” Melvin said. “We had a really, really tough loss a couple of games ago. And every time we’ve had one of those, it’s seemed like we’ve come back and responded well.”

Resilience, somehow, is becoming a defining factor for a team still a game below .500. It was their 17th come-from-behind win of the season and their third time winning despite trailing entering the ninth inning, to go with five wins when the score is tied after eight.

“We’ve had a couple games like this where we’ve come from behind,” said Mike Yastrzemski, who got the Giants on the board with an RBI triple in the fourth inning and kept the Cubs from scoring with his assist from right field in the fifth. “It’s huge for our confidence, knowing that we’re never out of the game. As much as it looks like there’s a roller coaster of emotions, I don’t think there was as much as it looked like. Everyone was pretty calm and focused on what we had to do to win that game.”

With the would-be tying run on third and one out in the fifth, Yastrzemski fired a strike to catcher Patrick Bailey, who applied the tag on Patrick Wisdom and held his glove up to the home plate umpire, who raised his fist to signal an out and completed 9-2 double play.

It was the second time the Cubs were doubled up on the bases. Mike Tauchman was also thrown out by Michael Conforto to end the first inning.

“They’re momentum swings,” Melvin said. “The first one, there’s potentially a guy on second base, in scoring position. And with Yaz, at the time it’s a one-run game, so it’s a huge play. He’s got to make a great throw. And now with the blocking the plate (rules), Bails has to have the presence of mind to start in the right spot, which is very difficult when it’s a one-run game and you’re just digging to get an out.”

At 90.2 mph, it was Yastrzemski’s hardest throw from the outfield this season.

“One of my favorite plays in baseball is the outfield assist,” said Hicks, who pumped his fist in celebration. “It’s almost like a lost art in this game. But when it happens, it gets me going. I played outfield in high school, and that was my favorite thing to do.”

Related ArticlesSan Francisco Giants | SF Giants: Bochy, Melvin share their Willie Mays memories ahead of Rickwood Classic San Francisco Giants | SF Giants’ All-Star voting leader didn’t even start season on MLB roster San Francisco Giants | SF Giants’ key hits open floodgates as 29-year-old earns win in MLB debut San Francisco Giants | From France to Oracle Park: New SF Giants pitcher realizes MLB dream San Francisco Giants | SF Giants place another starting pitcher on injured listHis jersey soaked with sweat by the time his day was over after five innings and 87 pitches, Hicks battled the hottest conditions the Giants have played in this season. It was 93 degrees at first pitch, and while Hicks said he “didn’t really notice” the sticky heat, his fastball velocity dipped again, to an average of 93.1 mph.

After completing six innings three times in his first six starts, Hicks hasn’t done it once in his past nine outings. But it was his first time registering a zero in the run column since his first start of the season, lowering his ERA to 2.82, fourth-best in the National League.

At 76⅔ innings for the season, Hicks is one frame away from matching the career-high he set as a rookie reliever in 2018.

“Overall I felt like my sinker was working well today, and the splitter off that was pretty nice,” Hicks said. “My last year in the minor leagues, I got a scouting report from another team and they were like, ‘Anywhere from 89 to 99 (mph).’ It’s not that I’m trying to embrace it, but when I’m going more innings, especially when you have both, there are different situations where a 98 might play or a 92 might play.”

SF Giants: Bochy, Melvin share their Willie Mays memories ahead of Rickwood Classic

CHICAGO — Willie Mays may not be in attendance this week when the Giants visit his hometown and first professional ballpark, but the oldest living Hall of Famer won’t be far from their minds during Thursday’s Rickwood Classic.

“Unfortunately I don’t think he’ll be able to go there,” manager Bob Melvin said, “but we’ll all be thinking about him when stepping on that field, saying ‘Willie Mays played here.’”

The Giants were selected to participate in the first major-league game at Birmingham, Alabama’s Rickwood Field due in large part to Mays, who grew up within spitting distance of the ballpark and called it home while playing as a teenager for the Black Barons, the town’s team in the Negro Southern League.

Mays, 93, released a statement Monday saying that, “I’d like to be there. But I don’t move as well as I used to. So I’m going to watch from my home (in the Bay Area).

“Rickwood’s been part of my life for all my life. Since I was a kid. It was just ‘around the corner there’ from Fairfield (where Mays grew up) and it felt like it had been there forever. Like a church. The first big thing I ever put my mind to was to play at Rickwood Field. It wasn’t a dream. It was something I was going to do. …

“I’m glad that the Giants, Cardinals and MLB are doing this, letting everyone see pro ball at Rickwood Field. Good to remind people of all the great ball that has been played there, and all the player. All these years and it is still here. So am I. How about that?”

Now in his 90s, Mays isn’t quite the consistent presence around the ballpark now as he once was in his post-playing days. It causes a stir whenever he drops by, typically holing up in former clubhouse manager Mike Murphy’s office while players and team personnel stop in, as he did to ring in his 92nd birthday last May.

It’s a different relationship for the current crop of Giants players than for their manager, who grew up watching Mays as a young baseball fan on the Peninsula and got to know him well after being traded to his hometown club after his rookie season.

“In ’86 when I showed up for the first time to Candlestick, his locker was next to mine and he was around some,” Melvin said. “That was when I first got to know him. And then over the years, had some conversations with him.”

Born three years after the Giants moved to California and 10 years old when Mays played his final game in San Francisco, Melvin had the unique opportunity to go from idolizing Mays to nurturing a relationship as a couple of baseball lifers.

Lockering next to him, Melvin said, “it was more just about questions I would have for him.” When the gnarly winds at Candlestick would switch directions, Mays told him, “‘When the wind blew in from left, I hit ’em out to right.’ And he would just show you this picture-perfect (form). He probably couldn’t explain it, but he certainly knew how to do it.”

One thing Mays was always cognizant of was the value and desirability of his signature, which was Bruce Bochy’s introduction to him when he joined the organization in 2007. Bochy intended to continue the tradition of hosting the Giants’ living Hall of Famers in spring training, and Mays showed up prepared.

“The first day of spring training, he walks in with a dozen baseballs signed. He goes, ‘You’re probably going to need these,’” Bochy recalled. “It was such a great gesture. The last thing you want to do is go ask him for a baseball. I just loved talking to the man.”

Related ArticlesSan Francisco Giants | After Melvin’s ejection, SF Giants rally to beat Cubs with Estrada’s big blast San Francisco Giants | SF Giants’ All-Star voting leader didn’t even start season on MLB roster San Francisco Giants | SF Giants’ key hits open floodgates as 29-year-old earns win in MLB debut San Francisco Giants | From France to Oracle Park: New SF Giants pitcher realizes MLB dream San Francisco Giants | SF Giants place another starting pitcher on injured listOn those days when the likes of Willie McCovey, Gaylord Perry and Orlando Cepeda would stop by the Giants’ Scottsdale facilities, Mays “dominated” the conversation.

“It was great, too. He would get on these guys about not playing enough in spring training,” Bochy said. “His little office, so to speak, was across from my office. So we had a lot of daily chats. I loved talking baseball with him.”

Melvin said watching Mays “probably inspired me to play baseball and like it as much as I did,” so it was extra special when the Hall of Famer reached out after Melvin notched a meaningful milestone while managing across town. In 2017, he became the 64th MLB manager to win 1,000 career games.

“I got to speak with him for a while,” Melvin said. “More about the history, the legacy, the Bay Area and all that type of thing.”

More recently, Melvin connected again with Mays when he accepted the Giants’ managerial gig this offseason.

Together with the fact that Melvin spent a chunk of his minor-league career playing at Rickwood, he said, “I think we’re just the perfect team to go there.”