P.A. Kane's Blog, page 3

April 14, 2020

Born Not To Run . . .

Though I had officially called it quits on my day job of nearly three-decades Christmas Eve, January 2, 2020 felt like my first real day of retirement. Two of my kids were still home, one on college break, the other recently graduated and looking for a job. My wife had gone back to work that morning, but before doing so, turned off the lights on the Christmas tree, signaling the holidays were officially over. Over too, was the excitement leading up to my retirement, which made me feel like a between person, a ghost passing through a purgatory of relative being and non-being and coming out the other side a whole person again who, for the first time since his teens, no longer had a job to go to. Now that these things had passed, I was charged with implementing the plan I developed to avoid common post-work mistakes like watching Morning Joe, napping half the day away or pouring myself a drink at noon.

I awoke a bit before 4 a.m. which was a shade later than the time I got up during my working days. I made coffee, fed animals and engaged in a bit of self-loathing for wasting time scrolling through meaningless social media posts. Eventually, about 4:45am, I got going on what would fill many of my post-work hours—writing. I am the author of two novels and currently have a book of essays in search of a home. So I got to work on my highest priority piece, a novel that had been shelved for some time because of the day job and other projects—I always seem to have twenty things going at once. Part of my plan was to prioritize these projects into a hierarchical order. The most important, hardest writing would come in the earliest part of the day, when the caffeine circulating through my system would synchronize with my fresh, well rested mind. Other writing and tasks would follow according to importance.

Kaya Francis Bean

These walks were to be another component of my retirement. In the day to day bustle of working, your environment often becomes something to contend with rather than experience, especially when you work outdoors and live just outside of Buffalo, New York. I wanted to experience my environment in a non-antagonistic way. I wanted the snow to have a chance to be earthy and neutral rather than this nuisance that made my commute harried and dangerous. I wanted the stillness and solitude of the woods to be a volume knob set to one or zero. So, in the bright sunshine on a balmy forty-three degree day in Western New York, me and my excitable forty-five pound rescue dog, Kaya Francis Bean took the short twenty minute ride south of the city to Chestnut Ridge Park.

For many on the south side of the city and the nearby Southtowns, The Ridge, as it is commonly known, played a big part in our lives. Growing up in the 60’s, Buffalo still had a lot of heavy industry and The Ridge was a day long respite from the dirty city and it’s nearby industry. In the winter it was a place to sled, toboggan and drink hot chocolate. In the summer there were picnics that always included baseball, catching frogs and sliding down the ravine that cut through the park. Later, in my high school years I would attend big parties on spring and summer weekends, where we would drink beer, throw a frisbee and just hang with friends. And, because I was shy and inarticulate and we didn’t have the social media or apps, I tried to get the attention of girls, for whom I had amorous feelings, by giving them—the eye. This was a statement made with protracted eye contact that said, I’m really interested, but have no game. Yes, it was as creepy as it sounds and almost never produced any results. By the time I had my own family heavy industry was long gone from Buffalo and a move to the suburbs came with an abundance of parks, so The Ridge, beyond some occasional sledding, became irrelevant.

Although much of the twelve-hundred acre park was closed to traffic in the winter, it was still possible to hike on the melting snow-covered roads. Trying to shut down my head a bit and just be, for a few moments, we walked out of the parking lot up an adjacent road off the main drag. The twisting path was worn with snow covered foot and paw prints, but there were no people in sight. Though I could hear the distant hum of maintenance trucks and eventually a dog barking, which made Kaya pull on her leash, it was relatively peaceful, calm and very pretty. I looked at the closed outhouses and picnic shelters covered by steel roofs and my quiet head started to buzz with a million memories of mosquito bites, unrequited crushes and pop flies. Sitting in one of the shelters on top of a picnic table with Kaya nudging at my hand to either come up with more treats or keep moving, I looked at a snow-covered field of a thousand kickball and tag games and started to think about place—this place, Chestnut Ridge, and Buffalo.

A few days earlier, on New Year’s Eve, a friend who had left Buffalo decades earlier for Houston, Texas posted on social media about how he was always reflective at this time of the year. That, when he was at a turning point in his life, Bruce Springsteen's Born To Run, guided his escape from Buffalo. It was his “rocket fuel of departure,” he said. Others chimed in about leaving Buffalo because of drugs or the ignorance of the parochial neighborhoods. In her teen years my future wife appropriated a line from “Thunder Road” off the same record for her high school quote—“it’s a town full of losers and I’m pulling out of here to win.” I too had romantic visions of departure and adventure, but mine came more from literature than music. But, leaving and moving on didn’t just start in a music studio with the Boss. A large part of the human story is about movement of people, whether it’s wandering nomadically in the desert for forty-years, chasing gold in the Yukon or these days, fleeing climate change. But, beyond these romantic visions of physical escape, the real thing I think Springsteen was talking about and fighting against is apathy. Born To Run, and “Thunder Road,” are a response to the deadening of the human spirit, the vacancy of our souls.

By the time Springsteen got to Born To Run in the mid-1970’s America had been conquered. Our expansionist dreams had been fulfilled from sea to shining sea and beyond. His audience, mostly white kids who had enough disposable income to buy his records by the millions, were bored and restless and connected to the idea of redemption beneath the hood of a car and to die in an everlasting kiss with Mary or Wendy as they pulled out of here to win. The imagery, to quote my friend was, “rocket fuel,” and the powerful myth making rock-n-roll, provided an escape from the monotony of middle-class privilege. But was it ever true?

Some of us, I suppose, can point to a handful of experiences when we felt free and alive, out cruising with our friends or a girl. But, the cruising and the girls never lasted, because we all had to, in the most un-born-to-run way, get up and go to work in the morning. We had to earn money so we could eat, have shelter and so we could buy false rock-n-roll dreams that would keep the tedium of our lives at bay. No one likes to admit it, but what we need, what we crave is stability. I can’t recall one instance where anyone has gone screaming into the night and come out the other side strong, healthy and successful.

We all know the nefarious stories of rock-n-rollers burning down the highway at two-hundred-miles-per-hour and then crashing in a haze of substance abuse and shattered dreams. We’ve read the adventures of Jack Kerouac on the road, crisscrossing the country in search of his muse, only to die from alcoholism at the tender age of forty-seven. Or maybe we’ve immersed ourselves in the depraved narratives of Charles Bukowski, who lived life out of a cardboard suitcase, forever at the edge of homelessness in Los Angeles. More recently the tragedy of Anthony Bourdain. And surely most of us know the stress and hardships of those whose work requires constant travel. So, this idea of gassing up the hemi, with four on the floor and busting out into the night seems to come with a whole lot of negative and often tragic consequences.

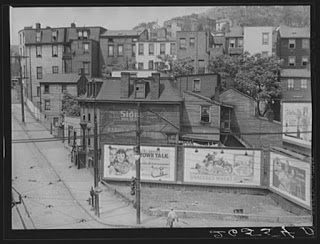

Then there’s the other side of that coin where we need rather than want to leave. The “rocket fuel” Born To Run provided my friend was to leave Buffalo, his hometown. All of us living in Rust Belt towns from Scranton, Pennsylvania to Gary, Indiana know the upheaval of the last forty years. As globalism made the world contract with its cheap labor and production costs, a way of life disappeared from these towns. At its height Bethlehem Steel in Lackawanna, just south of Buffalo, employed some twenty-thousand people and spawned thousands of secondary jobs. I remember sitting on my porch as a kid listening to my dad talk to our neighbor, Mr. Anderson, who worked at the plant—we all had neighbors who worked at the plant— Mr. Anderson pointing up at the familiar hazy twilight, all burnt orange and red with plant exhaust said, “That there is mother’s milk.” But, by 1982 the milk ducts went dry, not only in Buffalo, but throughout the whole region.

In 1950 Rust Belt towns contained almost forty-percent of the U.S. population. By 2000, that number dwindled to about twenty-five-percent. Somewhere in there my friend and other neighborhood people took their leave, including members of my own family. Some left, I suppose, to chase dreams fired by rock-n-roll, but I imagine most said good-bye because of bad circumstances and lack of opportunity. Regardless of why they left, once they found that place at the other end of the road, they most likely did the same things I was doing in Buffalo or what you were doing where you live. They got a job, found a spouse, raised kids, cut grass, cheered for teams, but just in a different physical location. Everything is the same except for the little dot on the map where they ended up. Of course, there are differences—they might have traded snow for tornados, chicken wings for gumbo or gone from a red state to a blue state. Otherwise, it’s all the same. We might not like to admit it, but the truth is, we are born not to run. The truth is, when upheaval and change becomes necessary we do everything in our power to settle back into a stable situation.

As much as it would seem that our job is to remain stable and not physically pick up and leave, the real task it seems to me, is to stay mentally engaged and plugged in so our lives don’t become monotonous and our soul’s dead. That’s what’s really born to run—our heads and our intellect. But people don’t nurture their heads. They listen to the same music, watch the same TV shows and news programs, hear the same boring stories about your wife’s work friend, Susan. Then, after a week of being trampled and debased chasing that dollar that keeps you stable and alive, you have a few beers and hear that scruffy Springsteen guy belt out Born To Run and you think the grass is greener in Texas or Florida, but it’s not. The place where the grass will grow to the most exquisite shade of suburban green is right there in your own head.

I did a physically demanding job in all kinds of weather for nearly three decades and while I can’t say I liked it, I was able to find a certain equanimity that others didn’t. And the reason was I continuously fed myself with books and music and writing. Through this whole past Christmas season, with holiday music assaulting the masses post-Halloween, I was able to mostly avoid all of those overplayed songs. While everyone was dashing through the snow with Gwen Stafeni on the local lite hits station, I was listening to a niche classical station on Sirius XM called Holiday Pops. It should be noted that when I hear the name Philip Glass, I think of J.D.Salinger’s fictional Glass family, not the great minimalist composer. When I hear the name DeBussy I think of the New York Knicks great 1970’s power forward, Dave DeBusschere, not the nineteenth century French impressionist composer. The reality is I know next to nothing about classical music and furthermore, I’m not sure I even like it. But for over a month I listened to the holiday music of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and the New York Philharmonic, King's College Choir and others. While it may not have been consistently pleasing, in the very least it was always fresh and interesting. It fired sleeping neurons in my head and took me to places I'd never seen before—new vistas were explored and unknown sonic landscapes were considered. But most of all this music made me ponder the season in a way Nat King Cole and Bing Crosby no longer had the power to do.

So, here in this formerly dirty town, in this park south of the city, with an excitable little rescue dog I’m going to walk these lovely snow-covered trails. I’m going to think about the games played and reminisce about all the people gone from here, but mostly as my life takes this new turn and I find a new framework to keep me moving forward I’m going to nurture that thing that was truly born to run—my head.

And when I get home, I'm going to make sure there are no dishes in the sink.

Published on April 14, 2020 07:29

January 8, 2019

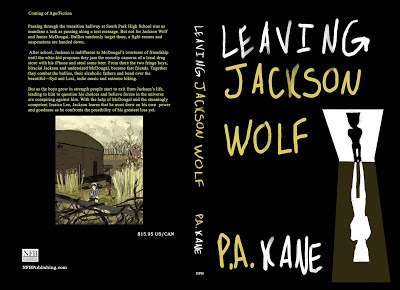

Here's what reviewers are saying about Leaving Jackson Wolf . . .

Published on January 08, 2019 05:00

January 5, 2019

The Snowy Accident

Many authors on the margins like me have marketing strategies that often include newsletters, where they tell you about works in progress (that’s wip for you non-authors), offer giveaways and provide the details about the hummus sandwich they had for lunch. Anything to keep a precious reader connected and interested. I rarely write about writing or my life as an author because quite frankly—it’s boring as shit. It would just be a lot of conversation about getting up early and sitting in front of a laptop, the tyranny of the day job, complaints about having to workout, bourbon and why U2 sucks.

Many authors on the margins like me have marketing strategies that often include newsletters, where they tell you about works in progress (that’s wip for you non-authors), offer giveaways and provide the details about the hummus sandwich they had for lunch. Anything to keep a precious reader connected and interested. I rarely write about writing or my life as an author because quite frankly—it’s boring as shit. It would just be a lot of conversation about getting up early and sitting in front of a laptop, the tyranny of the day job, complaints about having to workout, bourbon and why U2 sucks. And, if you really think about it, do you really want a dissertation from Jack Eichel about the way laces up his skates or tapes his stick? No—you want to see him score goals or create opportunities for his linemates to score goals.

So, I don’t write about writing. But, the other day as I was up early sitting in front of my laptop I stumbled upon something in my writing that I want to talk about, and it doesn’t include anything about the tyranny of the dayjob, working out, bourbon or goddamn U2. Of course, before my mc found The Snowy Day I had to do a Google search of beloved children’s books and there it was among others: Where The Wild Things Are, Goodnight Moon, The Giving Tree, all of which I loved and read hundreds of times to my three children over twenty years ago now.

We had long ago purged The Snowy Day and such books from our house that is overflowing with books, but I was still able to recall enough of it from memory to finish my chapter, incorporating some of the tactile feeling and sound that so characterizes the book. I also looked at some of the gorgeous illustrations on the internet and read some of the criticism in Wikipedia, which vacillated between over and under emphasizing the race of the mc—Peter, an inner city black boy. While all of the criticism seemed a little misplaced to me, it should be noted The Snowy Day was published in 1963, which was the dawn of the Civil Rights era and the beginning of reevaluating race in our country.

I did another thing too—I ordered it on Amazon and for the two days I waited I couldn’t remember feeling more excited to get a book than I did about this one. I would have been very disappointed if it wasn’t sitting on my porch after a long tyranny filled week at the day job when I got home on Friday. But, there it was and it was just as spectacular as I had remembered it. The bright colorful illustrations, the simple language, the memories of reading to my children and of course, my own childhood recollections of first snows. I can’t be sure of the magic that touched Jack Ezra Keats in creating this book, but the palpable sense of wonder in what Peter is seeing and feeling through soothing shapes, colors, language and the way he positions his body in space transports me to a better place. It’s a place of freedom and innocence, where the world moves blissfully along with wondrous piles of snow and sticks. It’s a place where I can see my mom’s blue eyes as she serves me piping hot tomato soup. It’s a place where my little brother is my best friend and he is me and I am him. And, it’s a place of infinite possibly, where the successes and failures of life don’t exist. Only the moment exists.

My mc making his way into that CAO school where his daughter is doing an internship and rediscovering The Snowy Day was just about the best and certainly the most peaceful thing that happened to me all week. Maybe these children’s books were never meant to be just for children.

Published on January 05, 2019 09:45

November 18, 2018

Hejira

To celebrate Joni Mitchell's 75th birthday here's a personal essay I wrote about the song Hejira. At some point this will be included in a book titled The Last Playlist. As a stand alone here, it lacks a little context and is in need of a professional edit, but for now—it's good enough. Happy Birthday Joni!

Hejira - Joni Mitchell My road to Joni Mitchell began from an unlikely place—Rick Ocasek of The Cars. Back in the early nineteen-eighties, Rolling Stone magazine would do these little cut outs of what musician were listening to at the moment, which was like an early version of this whole playlist phenomenon. Amidst all the garbage from the likes of Sammy Hagar and Bonnie Tyler, there was this really cool, obscure little list by Ocasek which included the album Blue,by Joni Mitchell. I didn’t much like The Cars, but was really impressed by his list.

Up to that point I was only familiar with Joni through songs on the radio and Court and Spark which my buddy The Doctor inherited from his sister and would sometimes play while we were hanging out in his room instead of doing our Chemistry homework. Unlike most of us who were occupied with the flavor of the day—Queen, Fleetwood Mac and the like, The Doctor, had a PhD. level record collection that was small, but very hip and included jazz greats like Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Chick Corea and Court and Spark. I guess I liked the album, but not enough to explore further due to my very limited resources which went to Friday night beer and other brilliant albums like I’m In You by Peter Frampton. So I kind of forgot about Joni for several years until I saw Ocasek’s list. A little more evolved and a little further along with my resources I picked up Blueand it hit me hard. The intimacy of these revelatory songs featuring Joni’s bittersweet voice accompanied by minimal instrumentation—often just a lone guitar or piano, were so visceral and so real and were such a welcome break from hairdos and bombast of the punk/new wave I was listening to at the time. I also felt a kinship with Blue’s aspirations and disappointments while the wide open spaces, not suffocating with sound, were wondrous. Like many before me I not only fell for the music, but Joni as well. Beautifully blond, with an arresting smile she made you think of flowers and sunshine while informing you with an intelligence that was gritty and deep. The empty pinup she was not and my heart didn’t stand a chance against such a woman. After that I started to pick up some of her other albums and by the time I got to HejiraI was in pretty rough shape. I was in rapidly losing my hair; I was failing at everything and filled with enormous self-doubt without a clue as to how to turn any of it around. It was a very depressing hopeless time. I now realize this period was the natural end of the first part of my life. It came abruptly with a certain amount of inelegance. One day I was a shit-talking kid full of promise and the next day I was balding, unskilled, uneducated and didn’t know how to do anything other than finish a 12-pack. I wasn’t stupid, but I had neglected school and didn’t have any strong interests that would translate into a profession. I also didn’t have the drive to build a career or amass money. I had no idea what I wanted, but was pretty sure what I didn’t want. I was stuck and unable to adapt to my new circumstance. As superficial as it may be the thing that depressed me the most was losing my hair. People did their best to be sensitive to my situation, but as much they tried they couldn’t help but become somewhat hypnotized by a guy in his mid-twenties punched in the face with the comb over blues. Often I’d be talking to someone and I could see them fighting to keep eye contact, but the allure was just too great and slowly their eyes would drift upward and become transfixed on my massive forehead like it was a magnetic orb. It was humiliating and I hated the useless, but well-intentioned nods and gestures of sympathy. It was especially bad when you saw a girl you hadn’t seen for a few years. First, there was the shocked expression, then as you talked it would come around to the unspoken look in their eyes of: ‘Damn, what happened to you?…I’m so sorry!’ Then, they would move on and some follicle gifted asshole into REO Speedwagon or something. It sucked! I knew I had to change my situation; I literally had to become someone else. Going back to school I withdrew into music, books and self-medicated with marijuana. Early in this new monastic life, still depressed and very uncertain of the future I came across the album and the song Hejira, which sparked a conversation within myself and was really instructive in teaching me how alone and desolate we are in the world. Hejirais an Islamic word for flight or exodus and implies a break with the past. Six of the nine songs on the album were written on a solitary car trip Joni made from Maine to California in the mid-seventies and the song Hejira is a deep stock-taking meditation of the self. Unlike The Circle Game, Both Sides Now and Help Me, hits that have a sing along quality, this song and the entire album require concerted rapt attention on the part of the listener. It’s not the kind of music you casually tap your foot to or hum along with while folding the laundry—this shit is Shakespearean. I don’t believe the entire album contains a signal chorus, a catchy hook or a guitar solo. It is music that comes from deep within one’s being and is meant to be scrutinized thoughtfully, its secrets revealed only through careful deliberate consideration. Aurally, the song features subdued percussion and a brief wispy clarinet. In her unique finger picking style Joni plucks out what have become known as her “weird chords,” creating a distinctive feel of restlessness. Jaco Pastorius paints between the lines with his fretless bass adding substantially to the theme of flight. Joni’s voice is strong and confident with touches of frustration and a growing sense of indifference. Layered together it is hypnotic piece of art. Like the revelatory nature of Blue, over this restless bed of music Joni details her Hegira. Older, a bit weary and in control of some hard won truths this 337-word poetic recitation is more shadowy and philosophical than Blue’s exposed nerves. Here, she is a shell shocked defector fleeing the scene, thinking about love, her place in the world and facing up to some uncomfortable truths. And, as hard as Blue hit me, dropping the turntable arm down on Hejira was like crossing the tracks and ending up on the bad side of town where five-guys waited to beat the shit out of self-pitying assholes like me. It assaulted all my prior knowledge and I knew from those first listens there was something profoundly important here for me. But it came in fits and starts and I went through a process, a slow evolution, before I acknowledged and accepted its truths. Over the years Hejira has become very personal to me and when it pops up it stops me in my tracks and I can feel it pensively vibrate in my bones like its part of my DNA. Undistracted, it never fails to break me down. Starting out with the images of a solitary road trip where she stops at cafes along the way and considers her place in the world we quickly come to a revelation that melancholy is comfortable, like a warm cup of soup on a snowy day. It is a human feeling that occurs naturally and doesn’t require explanation. When I had my abrupt, inelegant fall and was so full of self-doubt and self-loathing I would withdraw into my sadness and feel the sorrow of living and grieve for my losses. I wasn’t paralyzed like Brian Wilson, but a little herb, some tunes and no people was about the only thing that made me feel good. It was really confusing trying to understand why this sadness felt so good. Of course, as an American, a Catholic and a MAN, I supposed it was another deficiency, another weakness and I should fight these depressing feelings and pull myself up by bootstraps. Ignore the infirmity and buck up. I tried, but as Hejira fell more into my listening rotation and I considered these lines, I fell more and more under its soporific spell and found this melancholy, this sadness not to be just a temporary escape, but a warm loving hand that helped me to feel alive. As the song notes—it was as natural a moody sky.

Up to that point I was only familiar with Joni through songs on the radio and Court and Spark which my buddy The Doctor inherited from his sister and would sometimes play while we were hanging out in his room instead of doing our Chemistry homework. Unlike most of us who were occupied with the flavor of the day—Queen, Fleetwood Mac and the like, The Doctor, had a PhD. level record collection that was small, but very hip and included jazz greats like Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Chick Corea and Court and Spark. I guess I liked the album, but not enough to explore further due to my very limited resources which went to Friday night beer and other brilliant albums like I’m In You by Peter Frampton. So I kind of forgot about Joni for several years until I saw Ocasek’s list. A little more evolved and a little further along with my resources I picked up Blueand it hit me hard. The intimacy of these revelatory songs featuring Joni’s bittersweet voice accompanied by minimal instrumentation—often just a lone guitar or piano, were so visceral and so real and were such a welcome break from hairdos and bombast of the punk/new wave I was listening to at the time. I also felt a kinship with Blue’s aspirations and disappointments while the wide open spaces, not suffocating with sound, were wondrous. Like many before me I not only fell for the music, but Joni as well. Beautifully blond, with an arresting smile she made you think of flowers and sunshine while informing you with an intelligence that was gritty and deep. The empty pinup she was not and my heart didn’t stand a chance against such a woman. After that I started to pick up some of her other albums and by the time I got to HejiraI was in pretty rough shape. I was in rapidly losing my hair; I was failing at everything and filled with enormous self-doubt without a clue as to how to turn any of it around. It was a very depressing hopeless time. I now realize this period was the natural end of the first part of my life. It came abruptly with a certain amount of inelegance. One day I was a shit-talking kid full of promise and the next day I was balding, unskilled, uneducated and didn’t know how to do anything other than finish a 12-pack. I wasn’t stupid, but I had neglected school and didn’t have any strong interests that would translate into a profession. I also didn’t have the drive to build a career or amass money. I had no idea what I wanted, but was pretty sure what I didn’t want. I was stuck and unable to adapt to my new circumstance. As superficial as it may be the thing that depressed me the most was losing my hair. People did their best to be sensitive to my situation, but as much they tried they couldn’t help but become somewhat hypnotized by a guy in his mid-twenties punched in the face with the comb over blues. Often I’d be talking to someone and I could see them fighting to keep eye contact, but the allure was just too great and slowly their eyes would drift upward and become transfixed on my massive forehead like it was a magnetic orb. It was humiliating and I hated the useless, but well-intentioned nods and gestures of sympathy. It was especially bad when you saw a girl you hadn’t seen for a few years. First, there was the shocked expression, then as you talked it would come around to the unspoken look in their eyes of: ‘Damn, what happened to you?…I’m so sorry!’ Then, they would move on and some follicle gifted asshole into REO Speedwagon or something. It sucked! I knew I had to change my situation; I literally had to become someone else. Going back to school I withdrew into music, books and self-medicated with marijuana. Early in this new monastic life, still depressed and very uncertain of the future I came across the album and the song Hejira, which sparked a conversation within myself and was really instructive in teaching me how alone and desolate we are in the world. Hejirais an Islamic word for flight or exodus and implies a break with the past. Six of the nine songs on the album were written on a solitary car trip Joni made from Maine to California in the mid-seventies and the song Hejira is a deep stock-taking meditation of the self. Unlike The Circle Game, Both Sides Now and Help Me, hits that have a sing along quality, this song and the entire album require concerted rapt attention on the part of the listener. It’s not the kind of music you casually tap your foot to or hum along with while folding the laundry—this shit is Shakespearean. I don’t believe the entire album contains a signal chorus, a catchy hook or a guitar solo. It is music that comes from deep within one’s being and is meant to be scrutinized thoughtfully, its secrets revealed only through careful deliberate consideration. Aurally, the song features subdued percussion and a brief wispy clarinet. In her unique finger picking style Joni plucks out what have become known as her “weird chords,” creating a distinctive feel of restlessness. Jaco Pastorius paints between the lines with his fretless bass adding substantially to the theme of flight. Joni’s voice is strong and confident with touches of frustration and a growing sense of indifference. Layered together it is hypnotic piece of art. Like the revelatory nature of Blue, over this restless bed of music Joni details her Hegira. Older, a bit weary and in control of some hard won truths this 337-word poetic recitation is more shadowy and philosophical than Blue’s exposed nerves. Here, she is a shell shocked defector fleeing the scene, thinking about love, her place in the world and facing up to some uncomfortable truths. And, as hard as Blue hit me, dropping the turntable arm down on Hejira was like crossing the tracks and ending up on the bad side of town where five-guys waited to beat the shit out of self-pitying assholes like me. It assaulted all my prior knowledge and I knew from those first listens there was something profoundly important here for me. But it came in fits and starts and I went through a process, a slow evolution, before I acknowledged and accepted its truths. Over the years Hejira has become very personal to me and when it pops up it stops me in my tracks and I can feel it pensively vibrate in my bones like its part of my DNA. Undistracted, it never fails to break me down. Starting out with the images of a solitary road trip where she stops at cafes along the way and considers her place in the world we quickly come to a revelation that melancholy is comfortable, like a warm cup of soup on a snowy day. It is a human feeling that occurs naturally and doesn’t require explanation. When I had my abrupt, inelegant fall and was so full of self-doubt and self-loathing I would withdraw into my sadness and feel the sorrow of living and grieve for my losses. I wasn’t paralyzed like Brian Wilson, but a little herb, some tunes and no people was about the only thing that made me feel good. It was really confusing trying to understand why this sadness felt so good. Of course, as an American, a Catholic and a MAN, I supposed it was another deficiency, another weakness and I should fight these depressing feelings and pull myself up by bootstraps. Ignore the infirmity and buck up. I tried, but as Hejira fell more into my listening rotation and I considered these lines, I fell more and more under its soporific spell and found this melancholy, this sadness not to be just a temporary escape, but a warm loving hand that helped me to feel alive. As the song notes—it was as natural a moody sky.

In eternally bombastic America we are indoctrinated to oppose any feeling of weakness, uncertainty or depression. Most commonly we’ll self-medicate (as I was doing) should these un-American feelings arise while leaning on endless clichés—have a little faith in yourself, count your blessings, things could always be worse, what doesn’t kill you only makes you stronger, look on the bright side, blah blah blah… If we can’t get by with these words we may seek the encouragement of clergy and they’ll fill you up with religious clichés like: “It’s all part of God’s plan for you” or “When God closes one door he opens another.” More pragmatically we might see a therapist who will listen without judgement and maybe provide a pharmacological solution to dull the pain. But that line about comfort in melancholy…the more I turned it over in my head the more I came to see it as the truest, most liberating statement ever uttered. And I fought it with every bit of my pugilistic American will, every dumb religious cliché floating around in my head and every, pull yourself up by the bootstraps inclination, sense of MANHOOD I had within me. In the end though, embracing the pain, rather than cutting it off or dealing with it by proxy gave me a sense of well-being and made me feel alive. Pondering those few lines from Hejira over and over whenever I felt the shock of disappointment or thought about some past failure, I learned to embrace these painful situations and to grieve for my losses and eventually these feelings of melancholy that provided comfort became indispensable to my well-being. Sometimes this grief is about past circumstances that can’t be changed, like the knowledge my mother is dead and I’ll never get to know her beyond our mother-son relationship; sometimes it’s about future circumstances that can’t be changed, like the day when our kids will leave my wife and I and go on to live their own lives; sometimes its totally about myself, like realizing more of life is behind me than ahead of me. Often this melancholy is prompted by music. Listening to Goggle Play in shuffle mode the other day I got all twisted up by Nanci Griffith’s beautiful song Heart of Indochine.In the song Griffith is in Viet Nam travelling in a boat on the Saigon River, a river that has seen much blood and death through war, but now, many years removed the river is transformed and at peace with the souls of all those French, Vietnamese and American combatants floating free—swimming together. A beautiful piece of music that made me hurt for those lost souls and for how we humans treat each other. Listening, I didn’t get angry at Lyndon Johnson or Robert McNamara. I didn’t think about the senselessness or injustice of Viet Nam. I just felt really sad for all those kids and their mothers, fathers siblings and wives.. And, I lamented this part of our stinking humanity. As my invincibility has abandoned me with the passing of time more and more these momentary bits of grief crawl under my skin and penetrate and change the core of who I am. Almost nothing makes me feel alive and human than these losses. But it doesn’t feel negative, it’s more just a part of living and I’ve learned to embrace it. I’ve come to think of it as the warm hand of God touching my soul and grieving with me. While, through a slow evolutionary process I learned to embrace my pain, the agrarian WendellBerry takes it a step further. About the time I was becoming familiar with Hejira I read an essay by Berry, which focused on the encroachment of comfort items in farming. He talked about a new line of John Deere tractors which enclosed the tractor operator in a weather-controlled glass space booth fully rigged with sound. So when it was hot you could flick on the ac; cold, you could mix in some heat all while listening to your favorite Molly Hatchet record. Use of such technology Berry argued reduced the experience of working the land down to its lowest common denominator. To get the essence of such work he argued, you had to feel the sun on your skin, the wind in your hair or a nip of cold in your fingertips. People who wanted to remove everything from the experience that was uncomfortable not only weren’t interested in farming, they weren’t, Berry asserted, interested in being alive. To remove all pain from living and experience only comfort was the same thing as wanting to be dead. Maybe it’s the same for people who shun melancholy? Those of us who walk around trying to keep all pain at bay with dumb clichés’, theological rationalizations or drugs aren’t really interested in being alive. Maybe, they want to be dead too? Though this idea of melancholy provided enough grizzle for ten songs, the Hejira didn’t end there. After a failed relationship Joni withdraws and evaluates her place in the world. While lamenting a weakness of flesh with cold snowy imagery she talks about our anonymity, self-reliance and the paradox of our humanity, which is intense, yet so disposable. We are so deep yet superficial. It was shocking to me that when I had my fall and was on such shaky ground how little others could do for me. For some irrational reason I expected something more than nods and gestures of sympathy I received from friends and family. Other, more fringe type of friends didn’t bother with nods or gestures—they started to avoid me altogether. My suffering was obvious in a pathetic sad sack sort of way and understandably, they thought it better to steer clear. Almost as bad as having a magnetic orb for a head was the knowledge I was now the exasperating friend who was either tolerated out of a sense of history or out and out ignored, when just a few short years earlier I was handsome, cool and could get the eye of just about any girl. So, I pondered these next lines and like the revelation that melancholy was comforting I realized nobody could do anything for me and the world could give a shit about my hurts, no matter how deep. And, though I was certainly hurting in the larger context of life my problems were absolutely superficial and on me. I owned them. It was height of immaturity and ego to think it would be otherwise. Once I accepted responsibility for my own troubles and understood how deep and superficial, we all are, I had another revelation—the discomforting notion of my own desolation. Despite a huge family, friends, co-workers and a larger world I was utterly alone. Up till then I defined myself by what others thought of me, which was mostly positive and provided a positive self-image. Now that I was facing rejection or indifference, along with other problems, I was forced to look in the mirror beyond my physical self, beyond how others defined me and deal with whoever and whatever lived beneath my skin. It was crystal clear and unfolded like one of Aristotle’s syllogisms—all of it was on me alone. Nobody or nothing could do for me, like I could do for me. Given how I grew up I don’t why I would’ve ever thought differently. This was growth. But it was only half-measure intellectual growth. In my head I knew what I had to do, but my heart was petty and resentful and not willing to give up without a fight. It would take some time to quell the desire to pin my situation on my father, teachers who let me slide by, uncaring friends, the larger world. My head was like a blank little acorn ready to become a mighty oak while my heart was determined to remain a dependent seedling. To that end, I remember this one Sunday afternoon after a long cold Buffalo winter drinking some beers with a buddy and some of his girlfriend’s friends at Chestnut Ridge Park. I was back in school and was really excited about all this new knowledge I was being exposed to and had taken to carrying a book with me everywhere I went (which I still do). In the side pocket of my baggy black pants that day it was a copy of Plato’s Dialogues. This really good-looking girl noticed the book and asked about it. So, we had a nothing little conversation about Plato. This was surprising, since this girl by any definition was a “gold-digger” and never talked to me even when I had a little something going on. As it turned out she wasn’t interested in Plato or me. She was gathering information. Later, I would overhear her imitating what I had said about Plato to her boyfriend, this guy with tiny little piranha teeth, who drove a BMW and was the heir to some insurance company. When she was done mimicking me both of them busted out in laughter like it was the funnist thing they ever heard—little piranha teeth were flying everywhere. Even when they became aware I was on to them they barely could muzzle their amusement. Rather than delivering a just measure of violence on both of them (which definitely crossed my mind) I stood there frozen for a moment and then turned away—crushed. My mind delt with the situation perfectly—fuck them, dumbasses, gold-digging bitch and her little cliched heir, but the rest of me was so defeated and hurt.

In eternally bombastic America we are indoctrinated to oppose any feeling of weakness, uncertainty or depression. Most commonly we’ll self-medicate (as I was doing) should these un-American feelings arise while leaning on endless clichés—have a little faith in yourself, count your blessings, things could always be worse, what doesn’t kill you only makes you stronger, look on the bright side, blah blah blah… If we can’t get by with these words we may seek the encouragement of clergy and they’ll fill you up with religious clichés like: “It’s all part of God’s plan for you” or “When God closes one door he opens another.” More pragmatically we might see a therapist who will listen without judgement and maybe provide a pharmacological solution to dull the pain. But that line about comfort in melancholy…the more I turned it over in my head the more I came to see it as the truest, most liberating statement ever uttered. And I fought it with every bit of my pugilistic American will, every dumb religious cliché floating around in my head and every, pull yourself up by the bootstraps inclination, sense of MANHOOD I had within me. In the end though, embracing the pain, rather than cutting it off or dealing with it by proxy gave me a sense of well-being and made me feel alive. Pondering those few lines from Hejira over and over whenever I felt the shock of disappointment or thought about some past failure, I learned to embrace these painful situations and to grieve for my losses and eventually these feelings of melancholy that provided comfort became indispensable to my well-being. Sometimes this grief is about past circumstances that can’t be changed, like the knowledge my mother is dead and I’ll never get to know her beyond our mother-son relationship; sometimes it’s about future circumstances that can’t be changed, like the day when our kids will leave my wife and I and go on to live their own lives; sometimes its totally about myself, like realizing more of life is behind me than ahead of me. Often this melancholy is prompted by music. Listening to Goggle Play in shuffle mode the other day I got all twisted up by Nanci Griffith’s beautiful song Heart of Indochine.In the song Griffith is in Viet Nam travelling in a boat on the Saigon River, a river that has seen much blood and death through war, but now, many years removed the river is transformed and at peace with the souls of all those French, Vietnamese and American combatants floating free—swimming together. A beautiful piece of music that made me hurt for those lost souls and for how we humans treat each other. Listening, I didn’t get angry at Lyndon Johnson or Robert McNamara. I didn’t think about the senselessness or injustice of Viet Nam. I just felt really sad for all those kids and their mothers, fathers siblings and wives.. And, I lamented this part of our stinking humanity. As my invincibility has abandoned me with the passing of time more and more these momentary bits of grief crawl under my skin and penetrate and change the core of who I am. Almost nothing makes me feel alive and human than these losses. But it doesn’t feel negative, it’s more just a part of living and I’ve learned to embrace it. I’ve come to think of it as the warm hand of God touching my soul and grieving with me. While, through a slow evolutionary process I learned to embrace my pain, the agrarian WendellBerry takes it a step further. About the time I was becoming familiar with Hejira I read an essay by Berry, which focused on the encroachment of comfort items in farming. He talked about a new line of John Deere tractors which enclosed the tractor operator in a weather-controlled glass space booth fully rigged with sound. So when it was hot you could flick on the ac; cold, you could mix in some heat all while listening to your favorite Molly Hatchet record. Use of such technology Berry argued reduced the experience of working the land down to its lowest common denominator. To get the essence of such work he argued, you had to feel the sun on your skin, the wind in your hair or a nip of cold in your fingertips. People who wanted to remove everything from the experience that was uncomfortable not only weren’t interested in farming, they weren’t, Berry asserted, interested in being alive. To remove all pain from living and experience only comfort was the same thing as wanting to be dead. Maybe it’s the same for people who shun melancholy? Those of us who walk around trying to keep all pain at bay with dumb clichés’, theological rationalizations or drugs aren’t really interested in being alive. Maybe, they want to be dead too? Though this idea of melancholy provided enough grizzle for ten songs, the Hejira didn’t end there. After a failed relationship Joni withdraws and evaluates her place in the world. While lamenting a weakness of flesh with cold snowy imagery she talks about our anonymity, self-reliance and the paradox of our humanity, which is intense, yet so disposable. We are so deep yet superficial. It was shocking to me that when I had my fall and was on such shaky ground how little others could do for me. For some irrational reason I expected something more than nods and gestures of sympathy I received from friends and family. Other, more fringe type of friends didn’t bother with nods or gestures—they started to avoid me altogether. My suffering was obvious in a pathetic sad sack sort of way and understandably, they thought it better to steer clear. Almost as bad as having a magnetic orb for a head was the knowledge I was now the exasperating friend who was either tolerated out of a sense of history or out and out ignored, when just a few short years earlier I was handsome, cool and could get the eye of just about any girl. So, I pondered these next lines and like the revelation that melancholy was comforting I realized nobody could do anything for me and the world could give a shit about my hurts, no matter how deep. And, though I was certainly hurting in the larger context of life my problems were absolutely superficial and on me. I owned them. It was height of immaturity and ego to think it would be otherwise. Once I accepted responsibility for my own troubles and understood how deep and superficial, we all are, I had another revelation—the discomforting notion of my own desolation. Despite a huge family, friends, co-workers and a larger world I was utterly alone. Up till then I defined myself by what others thought of me, which was mostly positive and provided a positive self-image. Now that I was facing rejection or indifference, along with other problems, I was forced to look in the mirror beyond my physical self, beyond how others defined me and deal with whoever and whatever lived beneath my skin. It was crystal clear and unfolded like one of Aristotle’s syllogisms—all of it was on me alone. Nobody or nothing could do for me, like I could do for me. Given how I grew up I don’t why I would’ve ever thought differently. This was growth. But it was only half-measure intellectual growth. In my head I knew what I had to do, but my heart was petty and resentful and not willing to give up without a fight. It would take some time to quell the desire to pin my situation on my father, teachers who let me slide by, uncaring friends, the larger world. My head was like a blank little acorn ready to become a mighty oak while my heart was determined to remain a dependent seedling. To that end, I remember this one Sunday afternoon after a long cold Buffalo winter drinking some beers with a buddy and some of his girlfriend’s friends at Chestnut Ridge Park. I was back in school and was really excited about all this new knowledge I was being exposed to and had taken to carrying a book with me everywhere I went (which I still do). In the side pocket of my baggy black pants that day it was a copy of Plato’s Dialogues. This really good-looking girl noticed the book and asked about it. So, we had a nothing little conversation about Plato. This was surprising, since this girl by any definition was a “gold-digger” and never talked to me even when I had a little something going on. As it turned out she wasn’t interested in Plato or me. She was gathering information. Later, I would overhear her imitating what I had said about Plato to her boyfriend, this guy with tiny little piranha teeth, who drove a BMW and was the heir to some insurance company. When she was done mimicking me both of them busted out in laughter like it was the funnist thing they ever heard—little piranha teeth were flying everywhere. Even when they became aware I was on to them they barely could muzzle their amusement. Rather than delivering a just measure of violence on both of them (which definitely crossed my mind) I stood there frozen for a moment and then turned away—crushed. My mind delt with the situation perfectly—fuck them, dumbasses, gold-digging bitch and her little cliched heir, but the rest of me was so defeated and hurt.

When stuff like this happened I would revert into self-pitying blaming mode like it was someone else’s problem that I suffered these insults. But, no matter how much I tried to make others take the fall it always felt false and it always came back to me. And, even if there was someone or something to blame it didn’t help my situation one goddamn bit. It was on me alone and I knew it and it was up to me to change it. Though I just as soon drink toxic waste as put myself in a situation like that cold spring day at Chestnut Ridge all those years ago, there are times when it’s unavoidable. For those times I’ve learned to have simple, good humored, nothing conversations with nothing people and I leave the Plato in the car. I realize now the presence of that book in my side pocket was a way to compensate for the many things I was lacking. It was a false way to elevate myself and gain attention. Slowly I came to understand no matter how some bit of literature or some obscure tune excited or fascinated me, the rest of the world could give a shit. The rest of the world is programmed to be fascinated with BMW’s and insurance companies, not Plato and I probably got the beat down I deserved. Being interested in these types of things was mostly solitary business and I would have to accept that if I was going to pursue them. But, while my heart caught up with my head this idea of desolation didn’t necessarily equate to loneliness. All it meant was that I couldn’t hide from myself or blame others or let others define who I am. It meant that I assumed responsibility for myself, which was incredibly liberating and lessened the impact when those big uncontrollable forces of life came crashing down. It gave me the power to understand I didn’t need to be spending a Sunday afternoon drinking with vapid people or use my attention to obtain somebody else’s idea of success. And, it helped me to be less serious and tragic about my own issues. It’s not like I was enduring the misery and injustice that denies people the most basic necessities of survival like food and clean potable water. I wasn’t handsome anymore—so what. Had I remained pretty I’d probably would now be measuring out life in square-footage and portfolio components. So, on the way to understanding, whenever I had to confront some hurt or disappointment I found immense comfort thinking about how these blows, no matter how deep, in the grand scheme were pretty superficial and the power of change resided within me. Dealing with loss, defection, the necessity of melancholy as well as anonymity and superficiality, the Hejira now turned philosophical as it rolled into the home stretch attempting to discover what it all means with a discussion of mortality and Joni’s desire to live forever through her art. She arrives at the severe conclusion that we’re merely particles of change who orbit the sun for a short bit of time. Having learned so much from this song already I missed these lines for a long time probably out of some ego influenced sense of invincibility and sheer exhaustion. This is some weighty shit, even by Joni Mitchell standards and by this last part your brain is pretty used up. Once they registered though, they have been a permanent and haunting presence positioned in a way that dares you to prove them wrong. So far, I haven’t had much luck. The standard answers to these questions always come with so much side business and tend to be dogmatic and irrational. Maybe we just need to reboot, engage the control-alt-delete button and wipe all this shit clean—good-bye Vatican, so long Milton Friedman, sorry Sting, don’t let the door hit you in your milky-white ass. But, as I roll along on my own Hejira, sometimes I’ll be struck by a burning, awe-inspiring feeling beneath my skin that I can’t really explain and is so not of the drudgery of this world. It has a will of its own and shows itself randomly. Sometimes it comes through the saxophone of John Coltrane or the voice of Lucinda Williams. Sometimes I’ll feel it just sitting on the porch drinking coffee in the silent black solitude of early morning or in the unspoken bond with my children even when I’m telling them shit they don’t want to hear. There’s never judgement and it’s always resplendent, without being ostentatious. Without any real way to explain this I’ve come to think that this affirming feeling could be nothing less than grace. Fleeting and momentary contact with all that is good and right. It leaves me feeling hopeful, like it’s not all for nothing. That maybe, just maybe we are stardust that might be golden and we’ve got a good reason to give it another day.

Published on November 18, 2018 17:56

November 8, 2018

Interview With Book Blogger/Writer Anthony Avina

1)Tell us a little bit about yourself. How did you get into writing?

I grew up in a small three bedroom/one bathroom house with my parents and nine siblings in Buffalo, New York. Presently, I live in a suburb of Buffalo with my wife and three college age children, who are never going to leave.

I grew up in a small three bedroom/one bathroom house with my parents and nine siblings in Buffalo, New York. Presently, I live in a suburb of Buffalo with my wife and three college age children, who are never going to leave.As far as how I started to write. I went through a pretty aimless period after high school where I couldn’t figure out what I wanted to do and was in and out of college. Finally, in my early twenties I started read in a pretty serious way—stuff like Kerouac, Philip Roth, the poetry of Anne Sexton—which led me to want to give writing a shot. Problem was by the time I was all read up I was in my late twenties and had the pressure of trying to keep a roof over my head and a pretty serious girlfriend, whom I would eventually marry and have children with, so I had to shelve the writing thing. But when the kids got older and needed me less, I started to get up before work (really the middle of the night) make some coffee and write for a few hours. Few years later I have two published novels and a book of essays on the way, plus a million other ideas for books.

2) What inspired you to write your book?Leaving Jackson Wolf was intended to be a novella about Jackson’s friend McDougal. But as I got into it I realized the book was more about Jackson and his relationship with his father which was fraught with so much anger and dysfunction. This compelled me to explore how a fifteen-year-old kid would not only survive the violent dysfunction of his home life, but the possible outcomes on the other side of it. I also wanted to talk about guys interact with each other and tried to portray Jackson and McDougal without all the tough guy underpinnings of traditional male relationships. Both boys are pretty tough, but they aren’t afraid to be vulnerable with each other and to care for each other in a way you don’t see much, but I think healthy. I’m pretty sick of the toxic way guys measure themselves with each other.

3) What theme or message do you hope readers will take away from your book?I would hope when people read this they find value in owning up and being accountable for your life. Jackson makes many mistakes, but rather than wallow in his failures, he is persistent and moves forward trying to do better, always trying to find his power. Additionally, the boys love indie music and in dark times not only is it a friend that helps them feel less alone, but it also provides great perspective on life. So I would hope people might look into some of the fifty plus artists mentioned in the book and give them a good listen or just listen to good music in general. . 4) What drew you into this particular genre?I’m not really drawn to a genre. I just wanted to tell a story about two boys trying to make their way through a complicated world. The writing world seems to be genre and series driven, but all I really want to do is write stories about real people in real life situations regardless of their age or whatever.

5) If you could sit down with any character in your book, what would you ask them and why?Though she wasn’t in the book much I would like to sit with Jackson’s mom and get a update on where she was and what happened to her. Maybe this is a little voyeuristic and creepy, but I also would like to sit off to the side back at The Spot with Jackson and McDougal and just listen to them and talk music and the wonders of the female persuasion with a couple of beers. I’d like to hear the excitement in their voices as they talk about all the possibilities still ahead for them. 6) What social media site has been the most helpful in developing your readership?Boy, this social media thing is so overwhelming and so competitive. Too much for the one-man operation I run. I mostly use Facebook and I mostly do a bad job with it. Going forward as I gather more resources I’m going to invest in some outside help.

7) What advice would you give to aspiring or just starting authors out there?Don’t be afraid to start small. With the recent baseball playoffs I was reminded of being in a school lavatory back in the day and some older boys had a transistor radio and were listening to the World Series. From that single image of the boys with the radio in the lavatory I got this pretty cool story Knox, O'Malley, Sheena and The Miracle Mets. From little seeds a tree can grow.

8) What does the future hold in store for you? Any new books/projects on the horizon?Presently editing a book of essays that I hope to publish in the spring/summer of 2019.I have this new character, O’Malley, that I’ve been sketching on my blog and a couple chapters of another novel. For more great book talk check out Anthony Avina's blog.

Published on November 08, 2018 01:00

October 28, 2018

Indie Music and Leaving Jackson Wolf . . .

In Leaving Jack Wolf available November 2, 2018 on Amazon and other on-line retailers we find the main characters: Jackson, McDougal, Lexi and Syd to be huge fans of cutting edge indie music. From the end of Chapter 1, this is McDougal listening to his favorite new song by Mitski. Of Mitski, rock legend Iggy Pop said: ". . . probably the most advanced American songwriter I know . . . she can do whatever she wants- she writes and sings and she plays too."

.

From Leaving Jackson Wolf . . .“This is Mitski. She’s my favorite.”And from the mini Bose poured a voice with that rainy-afternoon vibe similar to Lana Del Rey’s, backed though by a broader range of instruments that included some ass-kicking guitar. The arrangements and Mitski’s voice also had more range. Sometimes it was apathetic, sometimes it was desperate and it ticked both up and down. Whatever it was, it was really good, and you could see McDougal totally lose himself in it. We all had stuff we got lost in, but McDougal brought it to another level under that ominous gray sky when “Your Best American Girl” started to play.Sitting there, he began to sway to her moody voice moving over a slowly picked guitar. With the additions of bass, drums, and a bed of buzzing atmospherics, the song’s momentum ramped up, and the swaying turned to gentle rocking as the music permeated every molecule of his being. When the song reached its breaking point, there was an explosion of guitars, and Mitski’s voice went from moody and vulnerable to a towering kind of righteousness. Jumping to his feet with a burst of energy, McDougal threw open his arms like some sort of miniature Jesus on the cross, and with his head bent upward to the sky and his eyes closed, he radiated on the spot. And with each change in the music, he contorted his little body while violently opening and closing his arms. It was fascinating to watch him become one with the tune. When it ended with these little effects, like fuzzy electric sparks being put back in a box, I turned to Lexi, wondering if she saw what I saw, and sure enough she had this awestruck, blown away look on her face.McDougal slowly lowered himself back into a sitting position on the crate and said, “Wow, I’m really drunk.”But he wasn’t drunk. Not from the beer anyway. Neither were Lexi or I. It was astonishment or something we were drunk on.After several awkward moments of not really knowing what to say to each other, we decided to call it a day. We stashed the remaining tallboys deep in the shrub along the fence and loaded up on Altoids and walked home in relative silence. McDougal turned off at West Woodside, and I walked Lexi to her house on Tifft Street. As I made my way back to Lockwood, where I lived, it started to rain a bit, and even though I had to come up with a way to keep my five days off from my old man, I couldn’t get McDougal and all that had happened today off my mind. I mean, what was that?

.

From Leaving Jackson Wolf . . .“This is Mitski. She’s my favorite.”And from the mini Bose poured a voice with that rainy-afternoon vibe similar to Lana Del Rey’s, backed though by a broader range of instruments that included some ass-kicking guitar. The arrangements and Mitski’s voice also had more range. Sometimes it was apathetic, sometimes it was desperate and it ticked both up and down. Whatever it was, it was really good, and you could see McDougal totally lose himself in it. We all had stuff we got lost in, but McDougal brought it to another level under that ominous gray sky when “Your Best American Girl” started to play.Sitting there, he began to sway to her moody voice moving over a slowly picked guitar. With the additions of bass, drums, and a bed of buzzing atmospherics, the song’s momentum ramped up, and the swaying turned to gentle rocking as the music permeated every molecule of his being. When the song reached its breaking point, there was an explosion of guitars, and Mitski’s voice went from moody and vulnerable to a towering kind of righteousness. Jumping to his feet with a burst of energy, McDougal threw open his arms like some sort of miniature Jesus on the cross, and with his head bent upward to the sky and his eyes closed, he radiated on the spot. And with each change in the music, he contorted his little body while violently opening and closing his arms. It was fascinating to watch him become one with the tune. When it ended with these little effects, like fuzzy electric sparks being put back in a box, I turned to Lexi, wondering if she saw what I saw, and sure enough she had this awestruck, blown away look on her face.McDougal slowly lowered himself back into a sitting position on the crate and said, “Wow, I’m really drunk.”But he wasn’t drunk. Not from the beer anyway. Neither were Lexi or I. It was astonishment or something we were drunk on.After several awkward moments of not really knowing what to say to each other, we decided to call it a day. We stashed the remaining tallboys deep in the shrub along the fence and loaded up on Altoids and walked home in relative silence. McDougal turned off at West Woodside, and I walked Lexi to her house on Tifft Street. As I made my way back to Lockwood, where I lived, it started to rain a bit, and even though I had to come up with a way to keep my five days off from my old man, I couldn’t get McDougal and all that had happened today off my mind. I mean, what was that?

Published on October 28, 2018 12:00

October 20, 2018

Leaving Jackson Wolf . . .

Friends, neighbors, READERS— available November 2, 2018 at Amazon and other online retailers, along with Dog Ears Bookstore (688 Abbott Road Buffalo, NY 14220— near Red Jacket) the new novel from P.A. Kane, Leaving Jackson Wolf. Leaving Jackson Wolf is a gritty coming of age story of two fringe boys—biracial Jackson and undersized McDougal—trying to find their power in a complicated unforgiving world.Read the opening . . .

Friends, neighbors, READERS— available November 2, 2018 at Amazon and other online retailers, along with Dog Ears Bookstore (688 Abbott Road Buffalo, NY 14220— near Red Jacket) the new novel from P.A. Kane, Leaving Jackson Wolf. Leaving Jackson Wolf is a gritty coming of age story of two fringe boys—biracial Jackson and undersized McDougal—trying to find their power in a complicated unforgiving world.Read the opening . . .Chapter 1

McDougal had some pituitary dysfunction bullshit that made him a little runt. He wasn’t the kind of runt who would cower and not fight when the bigger guys kicked him around—he just had that pituitary shit that made him little and weak. One spring day in the ninth grade as I made my way through the transition hallway, which connected the old and new buildings of South Park High School, this redheaded gorilla eleventh grader, Talty McManus, literally kicked McDougal into me. Tangled in my legs, the little shit took me down like a teetering 4 a.m. drunk, dislodging my books all over the floor. Now, I didn’t really give a shit about that little runt fuck McDougal—people could kick him all they wanted as far as I was concerned—but as I lay there all twisted up with him, I got really mad at the sound of that moron gorilla McManus and his friends laughing. Once untangled, I scooped up my heavy Literature Today book, jumped to my feet, and with both hands cracked McManus right upside his giant moron head. The impact caused him to stumble back into the hallway wall. His two friends were on me in a flash, and after I landed a solid right to the jaw of one of them, they locked my arms up behind my back. When he regained his equilibrium, McManus proceeded to bash the shit out of me until the shop teacher, Mr. Pierson, came and broke it up. I was still really mad and wasn’t thinking about any consequences when McManus’s friends let me go and I threw a punch that grazed his jaw and eventually landed on the chin of a very angry Mr. Pierson. I already had a zero-tolerance five-day suspension, and nailing Mr. Pierson would maybe get me more. But what did I care? Five days off . . . Maybe I’d punch ten more of these morons and slide right into summer vacation. Despite me landing that errant punch on the shop teacher, for which I apologized, Mr. Mattimore, the school principal, decided not to involve the police or any further discipline beyond the five-day suspension. Instead, the four of us—the flame-headed gorilla McManus, his two friends, and I—were sent to the detention room and McDougal, the bullied runt, was sent along to class. Mr. Franklin, the imposing security guard, babysat us as we theoretically waited for our parents to pick us up. Over the next hour or so McManus’s friends were escorted out, leaving just the two of us there separated by Mr. Franklin. I settled in with a Nick Hornby book I was reading, knowing my dad, if they could even find him, would tell school officials to take a hike. I was their problem from 7:41 a.m. to 2:41 p.m. Sitting there, McManus every so often would draw my attention away from the Hornby book and mouth the words I’m going to kill you! to which I responded with a sarcastic smirk and then some kisses blown in his direction from my hand. Constrained by the presence of Mr. Franklin, he was like a big dumb Irish Setter tied to a parked car, and taunting him was almost better than cracking that stupid douche upside his moron head. When he was finally called to leave, he shouted, “You’re dead, Jackson!” Yeah, whatever. I left school later with a sense of liberation, five days’ worth, and decided to walk home rather than catch the bus. I almost missed McDougal leaning up against the streetlight in front of Rite Aid in his little puke-green jacket, calling out to me in his tiny voice, “Jackson . . . Jackson.” But I just kept walking—fuck that little asshole. He didn’t get the message, though, and in a voice that was probably yelling for him, said, “Thanks for helping me today.” Normally, I would’ve just let this pass, but there were other kids around who may have heard him, and I didn’t want anybody getting the impression that I was some kind of mark for the dispossessed and runty. So I turned around, took five steps in the direction of McDougal, and said, “Listen, you little fuck, I couldn’t give a shit about who kicks you around. Just don’t get kicked into me. Got it?” Then, to make sure he got it, I slapped him upside the head, and the little shit crumpled to the ground like a house of cards imploding on itself. Wincing in pain, he inched himself into a sitting position and looked up at me with his pathetic, tiny pain-filled eyes and I don’t know—the better nature of myself came to the surface. “McDougal, goddammit, get up. Stop being such a little shit.” I picked his meager little ass from the ground and started to brush him off and straighten him up. “Get off of me,” he said, trying to push me away. I stepped back and looked at him and was filled with . . . I don’t know what I was filled with, but I wanted to say something, and when nothing came to me, I turned to leave. I hadn’t taken two steps when McDougal’s tiny voice called out to me. “Hey, Jackson, you want to steal some beer from Rite Aid with me?”

Published on October 20, 2018 05:06

October 4, 2018

The Origin of O'Malley

In the midst of the Great Depression, on a hot summer night in 1931, a girl barely twenty years old of dubious eastern European origins and reputation enters a northwestern Pennsylvania hospital. Anxious and scared, accompanied only by her stern, disapproving mother, she gives birth to a son, whom she will call William.

William is the result of an affair between the young woman and a local business owner’s son of German descent. The exacting business owner forbids his son from having anything to do with the woman or her son and thus young William begins life with the shame and illegitimacy of being a bastard child. But, not being acknowledged by his father was only part of it. Within a few years young William will be rejected again, this time by his mother when she meets an Irish man named O’Malley and follows him to Buffalo, NY. There, she starts a family while young William anguishes with his grandmother in their ethnic enclave in Pennsylvania. Though wanting to be with his mother very badly William thrives as people rally around him and look out for him in his tightly knit community. He does well academically, is a good athlete and is the star of school plays. In his mid-teens his grandmother becomes ill and William is sent to Buffalo to finally be with his mother. On the long train ride to Buffalo not only does he bring the shame of his illegitimacy, he also brings a strange eastern European name and a funny Pennsylvania accent for which he is mocked and derided. Sheltered in his ethnic enclave his entire life, William isn’t prepared for these these verbal assaults and is hurt by them. But, he fights back and eventually loses the accent, takes the name O’Malley as his own and acclimates to his Irish/Catholic neighborhood. In government housing of that old First Ward Irish neighborhood he meets a redheaded beauty, named Marilyn, who also carries a heavy burden of familial dysfunction. They marry their futures together determined to overcome their humble beginnings. They work hard and have children of their own—many children. They teach these children well. They are upstanding, disciplined and smart children. Tops in all their classes and the envy of the neighborhood. Yet overcoming their meager beginnings and solidly establishing themselves among the middle class, with even greater prospects for their children, wasn’t as satisfying as they imagined, especially for William. Resentments start to fester in him. He gradually becomes aware of how not having a father and being abandoned by his mother hurt his prospects and development. He sees people from established families pass him by and becomes embittered. He feels cheated like he could have been more, like he could have achieved something greater than the middle class if only his past was different. And, on a cold December morning waiting at the hospital for his sixth child to be born he begins to wonder who he is and how it’s come to this—six children. He feels trapped and hopeless and suddenly realizes, no matter how hard you work, no matter how devoted to God you are, no matter how earnest and upstanding you are—you can never outrun your past. In a fit of rage and defiance and without Marilyn’s consent he changes the name on the birth certificate of this new son from William to Wilhelm—the name of the man who wouldn’t acknowledge him thirty years earlier, unwittingly pinning his past to his new son.

William is the result of an affair between the young woman and a local business owner’s son of German descent. The exacting business owner forbids his son from having anything to do with the woman or her son and thus young William begins life with the shame and illegitimacy of being a bastard child. But, not being acknowledged by his father was only part of it. Within a few years young William will be rejected again, this time by his mother when she meets an Irish man named O’Malley and follows him to Buffalo, NY. There, she starts a family while young William anguishes with his grandmother in their ethnic enclave in Pennsylvania. Though wanting to be with his mother very badly William thrives as people rally around him and look out for him in his tightly knit community. He does well academically, is a good athlete and is the star of school plays. In his mid-teens his grandmother becomes ill and William is sent to Buffalo to finally be with his mother. On the long train ride to Buffalo not only does he bring the shame of his illegitimacy, he also brings a strange eastern European name and a funny Pennsylvania accent for which he is mocked and derided. Sheltered in his ethnic enclave his entire life, William isn’t prepared for these these verbal assaults and is hurt by them. But, he fights back and eventually loses the accent, takes the name O’Malley as his own and acclimates to his Irish/Catholic neighborhood. In government housing of that old First Ward Irish neighborhood he meets a redheaded beauty, named Marilyn, who also carries a heavy burden of familial dysfunction. They marry their futures together determined to overcome their humble beginnings. They work hard and have children of their own—many children. They teach these children well. They are upstanding, disciplined and smart children. Tops in all their classes and the envy of the neighborhood. Yet overcoming their meager beginnings and solidly establishing themselves among the middle class, with even greater prospects for their children, wasn’t as satisfying as they imagined, especially for William. Resentments start to fester in him. He gradually becomes aware of how not having a father and being abandoned by his mother hurt his prospects and development. He sees people from established families pass him by and becomes embittered. He feels cheated like he could have been more, like he could have achieved something greater than the middle class if only his past was different. And, on a cold December morning waiting at the hospital for his sixth child to be born he begins to wonder who he is and how it’s come to this—six children. He feels trapped and hopeless and suddenly realizes, no matter how hard you work, no matter how devoted to God you are, no matter how earnest and upstanding you are—you can never outrun your past. In a fit of rage and defiance and without Marilyn’s consent he changes the name on the birth certificate of this new son from William to Wilhelm—the name of the man who wouldn’t acknowledge him thirty years earlier, unwittingly pinning his past to his new son.

Published on October 04, 2018 02:11

September 24, 2018

Knox, O'Malley, Sheena and The Miracle Mets

On Thursday October 16th, 1969 at approximately 2:15 pm, O’Malley was feeling pressure from the extra half glass of milk he drank at lunch and dutifully raised his hand to use the lavatory. After a slight shake of her head, Mrs, Hurley, his fourth grade teacher excused him.