Robert Lunday's Blog

November 20, 2023

The Literature of Disappearance: A Bibliography in Progress

Follow is my list of works – short fiction, novels, theory, criticism, memoir, general nonfiction, and contemporary poetry collections – that develop the trope of disappearance:

PlaysBarrie, J.M. Peter Pan and Other Plays [Mary Rose]. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Kennedy, Fin. How to Disappear Completely and Never Be Found. London: Nick Hearn Books, 2008.

Short StoriesBierce, Ambrose. The Complete Short Stories of Ambrose Bierce [“The Difficulty of Crossing a Field”]. Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 1984.

Borges, Jorge Luis. Collected Fictions [“The Man on the Threshold”]. New York: Penguin, 1999.

Chaon, Dan. Among the Missing. New York: Ballantine, 2002.

Davenport, Guy. A Table of Green Fields [“Belinda’s World Tour”]. New York: New Directions, 1993.

Desai, Anita. The Artist of Disappearance. New York: Harper Perennial, 2012.

Doctorow, E. L. All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories [“Wakefield”]. New York: Random House, 2012.

Doyle, Jacqueline. The Missing Girl. New York: Black Lawrence Press, 2017.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. Hawthorne’s Short Stories [“Wakefield”]. New York: Vintage, 2011.

Jackson, Shirley. Come Along With Me [“Louisa Please Come Home”]. New York: Viking, 1968.

—. “The Missing Girl.” New York: Penguin Random House, 2018.

Jewett, Sarah Orne. The Queen’s Twin and Other Stories [“Where’s Norah”]. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1899.

Lawrence, D.H. The Woman Who Rode Away and Other Stories. New York: Penguin, 1997.

Masih, Tara Lynn. How We Disappear: Novella & Stories. Winston-Salem, NC: Press 53, 2022.

McEwen, Ian. First Love, Last Rites [“Solid Geometry”] New York: Random House, 1975.

Murakami, Haruki. The Elephant Vanishes. New York: Vintage, 1994.

Porter, Andrew. The Theory of Light and Matter. New York: Vintage, 2010.

—. The Disappeared. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2023.

Stohlman, Nancy. After the Rapture. Baltimore, MD: Mason Jar Press, 2023.

Yanagita, Kunio. The Legends of Tono. Washington, D.C.: Lexington Books, 2008.

NovelsAbbott, Megan. The Song is You. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008.

—. The End of Everything. New York: Back Bay Books, 2012.

Abe, Kobe. The Ruined Map. New York: Vintage, 2001.

—. The Woman in the Dunes. New York: Vintage, 1991.

—. The Box Man. New York: Vintage, 2001.

—. Secret Rendezvous. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979.

Ansay, A. Manette. Sister. New York: Harper Perennial, 1997.

Archambeau, Robert. Alice B. Toklas is Missing. Raleigh, NC: Regal House, 2023.

Atwood, Margaret. Surfacing. New York: Anchor, 1998.

Auster, Paul. The New York Trilogy. New York: Penguin, 2006.

—. Moon Palace. New York: Penguin, 1990.

—. The Brooklyn Follies. New York: Penguin, 2009.

—. Oracle Night. New York: St. Martin’s, 2009.

—. In the Country of Last Things. New York: Viking, 1987.

Azem, Ibtisam. The Book of Disappearance. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Publications in Continuing Education, 2019.

Balzac, Honoré de. Colonel Chabert. New York: New Directions, 1997.

Bambara, Toni Cade. Those Bones Are Not My Child. New York: Vintage, 2000.

Bauer, Belinda. Snap. New York: Grove Press, 2019.

Bennett, Brit. The Vanishing Half. New York: Riverhead Books, 2022.

Berti, Eduardo. La mujer de Wakefield. Barcelona: Tusquets Editores, 2000.

Bolaño, Roberto. 2666. New York: Picador, 2009.

Bombal, María Luisa. House of Mist. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2008.

Braunstein, Sarah. The Sweet Relief of Missing Children. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012.

Buckhanon, Kalisha. Speaking of Summer. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2020.

—. Running to Fall. AALBC Aspire, 2022.

Busch, Frederick. Girls. New York: Ballantine, 1998.

—. North. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005.

Codrescu, Andrei. Wakefield. New York: Algonquin Books, 2004.

Danticat, Edwige. The Dew Breaker. New York: Vintage, 2005.

—. Claire of the Sea Light. New York: Vintage, 2014.

Dave, Laura. The Last Thing He Told Me. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Didion, Joan. A Book of Common Prayer. New York: Vintage, 1995.

Dyer, Geoff. The Search. Minneapolis: Graywolf, 2011.

Earling, Debra Magpie. Perma Red. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2022.

Englander, Nathan. The Ministry of Special Cases. New York: Vintage, 2008.

Ely, David. Seconds. New York: Harper Voyager, 2013.

Flynn, Gillian. Gone Girl. Ballantine, 2014.

Follet, Barbara Newhall. The House Without Windows. New York: Penguin, 2021.

Fowles, John. A Maggot. Boston: Little, Brown, 1985.

Frisch, Max. I’m Not Stiller. Dallas: Dalkey Archive, 2006.

Fuentes, Carlos. The Old Gringo. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2007.

Garro, Elena. Recollections of Things to Come. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1969.

Green, Henry. Concluding. New York: New Directions, 2017.

Gutcheon, Beth. Still Missing. New York: William Morrow & Company, 2005.

Hammett, Dashiell. The Maltese Falcon. New York: Vintage Crime, 2022.

Hawkins, Paula. Girl on a Train. New York: Riverhead Books, 2016.

Healey, Emma. Elizabeth is Missing. New York: Harper Perennial, 2015.

Hemingway, Ernest. The Torrents of Spring. New York: Scribner’s, 1998.

Ishiguro, Kazuo. When We Were Orphans. New York: Vintage, 2001.

Jackson, Shirley. Hangsaman. New York: Penguin, 2013.

Jones, Tayari. Leaving Atlanta. New York: Grand Central, 2023.

Jonnie, Brianna and Nshannacappo. If I Go Missing. Toronto: Lorimer Children & Teens, 2019.

Jordan, Neil. The Drowned Detective. New York: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Kafka, Franz. Amerika: The Missing Person. New York, Schocken, 2011.

Kamal, Sheena. The Lost Ones. New York: William Morrow, 2018.

Kim, Angie. Happiness Falls. New York: Hogarth Press, 2023.

Knight, Carol Lynne. If I Go Missing. Newbergh, OR: Fernwood Press, 2022.

Ko, Lisa. The Leavers. New York: Algonquin Books, 2018.

Krabbé, Tim. The Vanishing. New York: Random House, 1993.

Kwok, Jean. Searching for Sylvie Lee. New York: William Morrow, 2020.

Lacey, Catherine. Nobody is Ever Missing. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2014.

Larsson, Stieg. The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. New York: Vintage Crime, 2009.

Lee, Chang-Rae. Aloft. New York: Riverhead Books, 2005.

Lewis, Janet. The Wife of Martin Guerre. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2013.

Liu, Aimee. Flash House. New York: Warner Books, 2004.

Lindsay, Joan. Picnic at Hanging Rock. New York: Penguin, 2017.

Lippman, Laura. After I’m Gone. New York: Harper, 2014.

Lowndes, Marie Belloc. The End of Her Honeymoon. New York: Scribner’s, 1913.

Luiselli, Valeria. Lost Children Archive. New York: Vintage, 2020.

Mankowski, Guy. How I Left the National Grid: A Post-Punk Novel. Alresford, UK: Roundfire Books, 2015.

Mannion, Una. Tell Me What I Am. New York: Harper, 2023.

Marlowe, Derek. Echoes of Celandine. New York: Viking, 1970.

Martínez, Tomás Eloy. Santa Evita. New York: Vintage, 1997.

Matar, Hisham. Anatomy of a Disappearance. New York: Dial Press, 2012.

—. In the Country of Men. New York: Random House, 2008.

Maxwell, Abi. The Den. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2019.

McCarthy, Cormac. Blood Meridian: Or the Evening Redness in the West. New York: Vintage, 1992.

McEwen, Ian. The Child in Time. New York: Knopf Doubleday, 1999.

Mendelsohn, Jane. I Was Amelia Earhart. New York: Vintage, 1997.

Michaels, Lisa. Grand Ambition. New York: W. W. Norton, 2002.

Mitchard, Jacquelyn. The Deep End of the Ocean. New York: Penguin, 1999.

Modiano, Patrick. Missing Person. Davine R. Godine, 2005.

Mooney, Robert. Father of the Man. New York: Pantheon, 2001.

Morris, Mary McGarry. Vanished. New York: Penguin, 1997.

Morselli, Guido. Dissipatio H.G.: The Vanishing. New York: New York Review of Books, 2020.

Mueleman, Sarah. Find Me Gone. New York: Harper, 2018.

Murakami, Haruki. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. New York: Vintage, 1998.

Ng, Celeste. Everything I Never Told You. New York: Penguin, 2015.

—. Little Fires Everywhere. New York: Penguin, 2019.

—. Our Missing Hearts. New York: Penguin, 2022.

Novey, Idra. Ways to Disappear. New York: Little, Brown, 2017.

Nutting, Alissa. Made for Love. New York: Ecco Press, 2018.

Oates, Joyce Carol. Carthage. New York: Ecco Press, 2014.

O’Brien, Tim. In the Lake of the Woods. Boston: Mariner Bay Books, 2006.

Oliver, Lauren. Vanishing Girls. New York: HarperCollins, 2016.

O’Nan, Stewart. Songs for the Missing. New York: Penguin, 2009.

Ondaatje, Michael. In the Skin of a Lion. New York: Knopf Doubleday, 1997.

—. Anil’s Ghost. New York: Vintage, 2001.

Pamuk, Orhan. The Black Book. New York: Vintage, 2006.

Partnoy, Alicia. The Little School. Jersey City, NJ: Cleis Press, 1998.

Perec, Georges. A Void. Boston: Verba Mundi, 2005.

Picoult, Jodi. Leaving Time. New York: Ballantine, 2015.

Piper, Evelyn. Bunny Lake is Missing. New York: Feminist Press, 2004.

Pirandello, Luigi. The late Mattia Pascal. New York: New York Review of Books, 2004.

Phillips, Julia. Disappearing Earth. New York: Vintage, 2020.

Porter, Andrew. In Between Days. New York: Vintage, 2013.

Pritchett, V.S. Dead Man Leading. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Rao, Shobha. Girls Burn Brighter. New York: Flatiron Books, 2019.

Rising, Lawrence. She Who Was Helena Cass. New York: George H. Doran, 1920.

Rose, Heather. The Butterfly Man. St. Lucia, Australia: University of Queensland Press, 2005.

Ryan, Erin Kate. Quantum Girl Theory. New York: Random House, 2023.

Semple, Maria. Where’d You Go, Bernadette. New York: Back Bay Books, 2013.

Simenon, Georges. Monsieur Monde Vanishes. New York: New York Review of Books, 2004.

Simpson, Mona. The Lost Father. New York: Vintage, 1993.

Spark, Muriel. Aiding and Abetting. New York: Penguin, 2000.

Stern, Daniel. Twice Upon a Time: Stories. New York: W. W. Norton, 1992.

Traba, Marta. Mothers and Shadows. Columbia, LA: Readers International, 2017.

Tyler, Anne. Searching for Caleb. New York: Vintage, 1996.

—. Ladder of Years. New York: Vintage, 1996.

Valenzuela, Luisa. He Who Searches. Dallas: Dalkey Archive, 1987.

—. The Censors: A Bilingual Selection of Stories. Evanston, IL: Curbstone Press, 1995.

Walker, Alice. The Color Purple. New York: Penguin, 2019.

Watson, Randall. No Evil is Wide. Lake Dallas, TX: Madville Press, 2023.

White, Ethel Lina. The Lady Vanishes. Hertfordshire, UK: Wordsworth Classics, 2015.

Wieland, Liza. A Watch of Nightingales. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008.

Yocum, Katy. Three Ways to Disappear. Ashland, OR: Ashland Creek Press, 2019.

Zola, Émile. Buried Alive. New York: Warren Press, 1911.

MemoirsBonner, Betsy. The Book of Atlantis Black: The Search for a Sister Gone Missing. New York: Tin House Books, 2020.

Carlisle, Kelly Grey. We Are All Shipwrecks. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2018.

Conover, Sarah. Set Adrift: A Mystery and a Memoir – My Family’s Disappearance in the Bermuda Triangle. Gig Harbor, WA: 55 Fathoms, 2023.

Cumming, Laura. Five Days Gone: The Mystery of My Mother’s Disappearance as a Child. New York: Scribner’s, 2019.

Flook, Maria. My Sister Life. New York: Broadway Books, 1998.

Gwartney, Debra. Live Through This: A Mother’s Memoir of Runaway Daughters and Reclaimed Love. Boston: Mariner Books, 2010.

Harrison, Lindsay. Missing: A Memoir. New York: Scribner’s, 2014.

Kushner, David. Alligator Candy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Lunday, Robert. Disequilibria: Meditations on Missingness. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2023.

Matar, Hisham. The Return: Fathers, Sons, and the Land in Between. New York: Random House, 2017.

—. A Month in Siena. New York: Random House, 2019.

O’Hagan, Andrew. The Missing. London: Picador, 1995.

Renner, James. True Crime Addict: How I Lost Myself in the Mysterious Disappearance of Maura Murray. New York: Picador, 2017.

Rotondi, Jessica Pearce. What We Inherit: A Secret War and a Family’s Search for Answers. Los Angeles: Unnamed Press, 2020.

Theory and CriticismAbe, Kobo. The Frontier Within: Essays. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Agamben, Giorgio. What is Real? Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

—. The Perfect Crime. New York: Verso, 2008.

—. Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? Chicago: Seagull Books, 2009.

—. America. New York: Verso, 2010.

Bishop, Karen Elizabeth. The Space of Disappearance: A Narrative Commons in the Ruins of Argentine State Terror. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2021.

Edkins, Jenny. Ithaca: Missing: Persons and Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2016.

Gordon, Avery. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Heller-Roazen, Daniel. Absentees: On Variously Missing Persons. New York: Zone Books, 2021.

Pitt, Kristin E. Body, Nation, and Narrative in the Americas. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Taylor, Diana. Disappearing Acts: Spectacles of Gender and Nationalism in Argentina’s Dirty War. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997.

Virilio, Paul. The Aesthetics of Disappearance. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009.

Other NonfictionAllen, Michael J. Until the Last Man Comes Home: POWs, MIAs, and the Unending Vietnam War. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Ayers, Captain John H. Missing Men: The Story Of The Missing Persons Bureau Of The New York Police Department. New York: Garden City Publishing, 1932.

Baldwin, James. The Evidence of Things Not Seen. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1985.

Begg, Paul. Into Thin Air: People Who Disappear. London: David & Charles, 1979.

Biaggio, Maryka. The Point of Vanishing: Based on the True Story of Author Barbara Follett and Her Mysterious Disappearance. Mechanicsburg, PA: Sunbury Press, 2021.

Billman, Jon. The Cold Vanish: Seeking the Missing in North America’s Wilderness. New York: Grand Central, 2021.

Boss, Pauline. Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Bowden, Mark. The Last Stone: Masterpiece of Criminal Interrogation. Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020.

Boynton, Robert S. Invitation-Only Zone. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2017.

Brown, Ethan. Murder in the Bayou: Who Killed the Women Known as the Jeff Davis 8? New York: Scribner’s, 2018.

Busch, Akiko. How to Disappear: Notes on Invisibility in a Time of Transparency. New York: Penguin, 2020.

Carlson, Eric Stener. I Remember Julia: Voices of the Disappeared. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996.

Coleman, Jonathan. Exit the Rainmaker. New York: Dell, 1989.

Congram, Derek. Missing Persons: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Disappeared. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 2016.

Davis, Natalie Zemon. The Return of Martin Guerre. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Denton, Sally. The Bluegrass Conspiracy: An Inside Story of Power, Greed, Drugs & Murder. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

Dimock, Brad. Sunk Without a Sound: The Tragic Colorado River Honeymoon of Glen and Bessie Hyde. Flagstaff, AZ: Fretwater Press, 2001.

Dumas, Alexandre (Père). The Crimes of the Marquise de Brinvilliers [“Martin Guerre”] London: Methuen, 1908.

Dyer, Geoff. The Missing of the Somme. New York: Vintage, 2011.

El-Hai, Jack. The Lost Brothers: A Family’s Decades-Long Search. Ann Arbor: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

Ellison, Mary. Missing from Home. London: Pan Books, 1964.

Fischer, Paul. The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder, and the Movies. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Fleming, Peter. Brazilian Adventure. London: Alden Press, 1933.

Fradkin, Philip L. Everett Ruess: His Short Life, Mysterious Death, and Astonishing Afterlife. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Franklin, H. Bruce. M.I.A. or Mythmaking in America: How and Why Belief in Live POWs Has Possessed a Nation. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1993.

Gibler, John. I Couldn’t Even Imagine That They Would Kill Us: An Oral History of the Attacks Against the Students of Ayotzinapa. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2017.

Grann, David. The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon. New York: Vintage, 2010.

Greene, Karen Shalev and Lilian Alys. Missing Persons: A Handbook of Research. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Halber, Deborah. The Skeleton Crew: How Amateur Sleuths are Solving America’s Coldest Cases. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

Hepburn, Stephanie and Rita James Simon. Human Trafficking Around the World: Hidden in Plain Sight. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Howe, Nicholas. Not Without Peril. Boston: Appalachian Mountain Club, 2009.

Ling, Justin. Missing from the Village: The Story of Serial Killer Bruce McArthur, the Search for Justice, and the System That Failed Toronto’s Queer Community. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2022.

Magueijo, João. A Brilliant Darkness: The Extraordinary Life and Disappearance of Ettore Majorana, the Troubled Genius of the Nuclear Age. Boston: Basic Books, 2009.

Marnham, Patrick: Trail of Havoc: In the Steps of Lord Lucan. London: Penguin, 1987.

Mauger, Léna and Stéphane Remael. The Vanished: The “Evaporated People” of Japan in Stories and Photographs. New York: Skyhorse, 2014.

McDiarmid, Jessica. Highway of Tears: A True Story of Racism, Indifference, and the Pursuit of Justice for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. New York: Atria Books, 2019.

McGrath, Ben. Riverman: An American Odyssey. New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2023.

Morewitz, Stephen J. and Caroline Sturdy Colls. Handbook of Missing Persons. Berlin: Springer, 2018.

Murdoch, Sierra Crane. Yellow Bird: Oil, Murder, and a Woman’s Search for Justice in Indian Country. New York: Random House, 2021.

Nash, Robert Jay. Among the Missing. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1978.

Nickerson, Shelia. Disappearance: A Map. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1996.

Phillips, S. M. Famous Cases of Circumstantial Evidence. Boston: Estes & Lauriat, 1873.

Pratt, Bramwell. God’s Private Eye: The Fascinating Work of The Salvation Army Investigation Department. St. Albans, UK: Campfield Press, 1988.

Preitler, Barbara. Grief and Disappearance: Psychosocial Interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2015.

Rawlence, Christopher. The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder, and the Movies. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Recko, Corey. Murder on the White Sands: The Disappearance of Albert and Henry Fountain. Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 2007.

Reidel, James. Vanished Act: The Life and Art of Weldon Kees. Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2007.

Rich, Doris L. Amelia Earhart: A Biography. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 1996.

Richmond, Doug. How to Disappear Completely and Never Be Found. Palms Springs, CA: Desert Publications, 1996.

Roberts, David. Finding Everett Ruess: The Life and Unsolved Disappearance of a Legendary Wilderness Explorer. New York: Crown, 2012.

Roberts, Sara Hawys and Leon Noakes. Withdrawn Traces: Searching for the Truth About Richey Manic. London: Virgin Books, 2019.

Ruddick, James. Lord Lucan: The Truth About the Century’s Most Celebrated Murder Mystery. London: Headline, 1994.

Salgado, Minoli. Twelve Cries from Home: In Search of Sri Lanka’s Disappeared. London: Repeater, 2022.

Sarasin, J. G. The Mystery of Martin Guerre. London: Hutchinson, 1934.

Saroyan, Aram. Genesis Angels: The Saga of Lew Welch & the Beat Generation. New York: William Morrow, 1979.

Sciascia, Leonardo. The Moro Affair: And the Mystery of Majorana. New York: New York Review of Books, 2004.

Stegner, Wallace. Mormon Country [Everett Ruess]. Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2003.

Stewart, Erin. The Missing Among Us: Stories of Missing Persons and Those Left Behind. Sydney, Australia: NewSouth Books, 2021.

Smith, Laura. The Art of Vanishing. New York: Viking, 2018.

Thernstrom, Melanie. The Dead Girl. New York: Counterpoint, 2014.

Thompson, Hunter S. Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone: The Essential Writing of Hunter S. Thompson [on Oscar Acosta]. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012.

Tofel, Richard J. Vanishing Point: The Disappearance of Judge Crater, and the New York He Left Behind. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2004.

Tomalin, Nicholas and Ron Hall. The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. New York: Stein and Day, 1985.

Villiers, Alan. Posted Missing: The Story of Ships Lost Without Trace in Recent Years. New York: Scribner’s, 1974.

Warren, William. Jim Thompson: the Unsolved Mystery. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2014.

Williams, Richard. Missing: The Inside Story of the Salvation Army’s Missing Persons Department. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1969.

Willis, Graham Denyer. Keep the Bones Alive: Missing People and the Search for Life in Brazil. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022.

Poetry(This section is focused on contemporary collections in which disappearance is a recurrent theme.)

Baker, Aimée. Doe. Akron, OH: University of Akron Press, 2018.

Emanuel, Lynn. Transcript of the Disappearance, Exact and Diminishing. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2023.

Finkel, Donald. The Wake of the Electron. New York: Atheneum, 1987.

Franklin, Jennifer. If Some God Shakes Your House. New York: Four Way Books, 2023.

González, Rigoberto. Black Blossoms. New York: Four Way Books, 2011.

—. Unpeopled Eden. New York: Four Way Books, 2013.

—. The Book of Ruin. New York: Four Way Books, 2019.

—. To the Boy Who Was Night: Poems: Selected and New. New York: Four Way Books, 2023.

Goodfellow, Jessica. Whiteout. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press, 2017.

L’Esperance, Mari. The Darkened Temple. Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2008.

Lindenberg, Rebecca. Love, An Index. San Fransisco: McSweeney’s, 2012.

Malone, Erin. Site of Disappearance. Chevy Chase, MD: Ornithopter Press, 2023.

Perlongher, Nestor. Cadavers. Phoenix, AZ: Cardboard House Press, 2018.

Quintanilla, Octavio. If I Go Missing. Auston, TX: Slough Press, 2014.

Scofield, Greg. Witness, I Am. Gibsons, BC, Canada: Nightwood Editions, 2016.

Shearin, Faith. Telling the Bees: Poems. Nacogdoches, TX: Stephen F. Austin University Press, 2015.

Uriba, Sara. Antígona González. Los Angeles: Les Figues Press, 2016.

Zurita, Raúl. Song for His Disappeared Love. Notre Dame, IN: Action Books, 2010.

[11/20/2023]

The post The Literature of Disappearance: A Bibliography in Progress appeared first on Robert Lunday.

October 23, 2023

ALSCW Paper: “Mystery and Missingness: The Literature of Disappearance”

This is a paper I delivered at the 2023 ALSCW conference in Houston earlier this month as part of the “Mystery and Secrecy: Ancient Origins, Modern Expressions” panel. I’ll likely cannibalize it toward later essays and eventually as part of the second disappearance manuscript currently in the works. the inflections are somewhat tropic and geocritical.

*

In this paper I’ll explore Missingness, or ways of thinking about missing persons. Though I’ve studied other fields – forensics, law enforcement/criminology, journalism, true crime, genre fiction, feature films and documentaries, podcasting, visual art, political science, cultural theory, philosophy, sociology, social work/psychology, I’ve focused more on imaginative responses to disappearance, particularly in fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry. (1)

In 1982, my stepfather, James Lewis, a recently-retired Vietnam veteran, disappeared, and his fate remains unknown. In a recently-published hybrid memoir called Disequilibria: Meditations on Missingness, (2) I tell of my family’s experience within a broader examination of Missingness as a cultural and historical phenomenon.

Gaston Bachelard

I tend to see any in-depth subject of study as a memory palace or theatrum mundi. Sometimes, particularly in dreams, this inner space is more like a Bachelardian (3) house of several floors and many rooms of varied sizes, rooms within rooms, alcoves, ample cabinetry, shelves, drawers, and small boxes inside drawers. As my mind and self-image have become increasingly digital, I think in terms of an endless web or a fractal landscape that changes over scales and dimensions, repeating patterns across the vastness and intimacy of the field.

The space of missingness, since it has been a personal, creative, and scholarly obsession for so many years, exhibits varying qualities, both intermittently and universally: reciprocity or interpenetration; nestedness, abyssal or recursive growth and reduction; extensivity and intensity or enfoldedness; instantaneity, which is both the possibility and the impossibility of action at a distance, or the reality of a Universal Now.

In its horizontality, Missingness is a continuum or a fluid/graduated relation between seeming-opposites; in its verticality it’s a chord, an Orphic descent, or an escape to transcendent spaces. It’s also a combinatorial or algorithmic tool: each element or trope can be viewed as a minor trope within every other element as master-trope. It might represent a benevolent or malevolent consciousness, a complex system or autonomous machine-process; or it might be amusing like a clever toy or a complex game.

Missingness is a recessive space: the almost-there of an asymptotic search, the sharp point of the v in “vanishing point.” It’s also a space of complexity and indeterminacy, with the strange dynamics of aporia: How can the Missing Person be missing? How can someone seem both living and dead, or neither?

Giorgio Agamben’s state of exception helps define the abject character of missingness: (4)

The state of nature and the state of exception are nothing but two sides of a single topological process in which what was presupposed as external (the state of nature) now reappears, as in a Mobius strip or a Leyden jar, in the inside (as state of exception), and the sovereign power is this very impossibility of distinguishing between outside and inside…(37) –

exhibiting in its metaphors (“topological process,” “Mobius strip or a Leyden jar”) the spatial characteristics, large and small, that are essential to my explorations of Missingness.

Reciprocity as a characteristic of Missingness is how a boundary or a pair of opposites will create a space of hybridity, cross-contamination or cross-fertilization, confusion, complementarity, ambiguity, or mystery. Perhaps a sustained, close examination of any binary reveals deeper complicatedness and complexity. (5) Plato’s Socrates in the Phaedo (6) says:

The journey is not as Aeschylus’ Telephus describes it. He says that only one single path leads to Hades, but I think it is neither one nor simple, for then there would be no need of guides; one could not make any mistake if there were but one path. As it is, it is likely to have many forks and crossroads… (92).

Similarly, Seneca in his Natural Questions (7) says: “Some of the sacred rites are not revealed to worshippers all at once. Eleusis retains some of its mysteries to show to votaries on their second visit.” (306). If the godhead is more immanent than transcendent, then complexity, plurality, delay, and indirection might be how we experience its cosmic personality; and at least some of its traces are understandably topographical.

Missingness is also charged with desire: my youngest brother wants to find his father, my mother wanted to find her husband. My brother’s search for his father continues as an almost-daily practice; my mother found closure without conclusion many years ago. What was my desire, my emotional investment? My stepfather’s disappearance, early on, was a punishment as answer to a childhood prayer: that he would go away and not come back. As a warrior, he went away and came back many times, and I always felt more at ease – in the military as well as emotional sense – when my stepfather was absent.

These forms of desire, with some degree of choice and varying degrees of exhaustion, force, and unending decay, are at the other end of a continuum with terror, horror, dread, and trauma. Desire and dread seem projections of the same inner space and fragile sense of self. My stepfather’s disappearance was, in what eventually became my own mythography, the closing of childhood fears and commencement of adult anxiety and guilt. If trauma is in part the inability to escape the bodily sense of a painful experience – that a harmful event seems to be occurring now – then a disappearance, as opposed to a buried body, is the traumatic ever-present.

Elena Gomel, Narrative Space and Time

At some early stage, we realize just how vast, old, and enfolded the world really is. We develop a healthy fear, then an acceptance, that the world even as we traverse its smaller spaces – our own street, neighborhood, or ward – is so large that our bodies are in no way its measure; that our height and reach are less helpful in comprehending the world than the a map or a globe.

Elana Gomel in Narrative Space and Time: Representing Impossible Topologies in Literature (8) connects Agamben’s thinking on states of exception to the London and Paris of Charles Dickens: “There is no longer a Newtonian time separate from the traumatic duration of the impossible world; nor is there a Euclidian space that can resist the encroachments of the twisted topologies of violence” (58). I feel this in my body: it’s the trauma of Missingness, of Modernity, and we’re all inside it.

“One cannot add nearnesses in order to attain a ‘sum’ of farness” observes Edward S. Casey. (9) This, too, I feel almost viscerally: remembering when I was a toddler, already as an Army brat moved across several borders of the world, wondering about the magic relations of scale: was the state of Georgia bigger or smaller than the United States? Was it a requirement of the journey that one sleep in crossing boundaries or oceans? Casey’s negation suggests a space where the folds of reality render the continuum itself irreal. That doesn’t make it useless: the folds themselves – crevices in the world, hinges between worlds – are vividly framed in the paradoxes or equivocations of the world.

As we’ve sought Jim Lewis in the domestic nearness he’d left behind, my brother and I still have seen his traces and still felt his ghost. We didn’t know which fold or within what continuum he might be concealed, or how he had turned his own local being into a distance – an abstraction and a vanishing now as old as the man before he disappeared.

In the weeks after James Lewis left our home, I sometimes stood in the driveway looking down the street where he’d driven away. I imagined the places where that neighborhood road connected to larger roads, the interstate, the local airport, and all the possibilities of direction and distance from those points. He was a pilot, so I had to imagine the more expansive possibilities – that he could be within shouting distance or on the other side of the world.

That street in a then-new development on the outskirts of Fayetteville, North Carolina, with sandhills, pines, and scrub oak surrounding tract-homes became the first continuum of Missingness: the mental space where I tried to discover, name, and order the essential elements of disappearance. The road begins somewhere inside and disappears in a tree line not far into the distance; or over the horizon, where it buckles under the weight of the sky. This is the Continuum: constructions of relations between two seeming-opposites, allowing for a delineation of scale, degree, progression, retrogression, or contiguity.

I’m interested in how artists invent through seeing the nested or fractal nature of the world, as here: that a kind of beauty mustn’t know itself, that the relation between oneself and the world is palindromic, that our mind allows us to inhabit many scales at the same time. So, one kind of Missingness might be how imbalances in the world – imbalances that are essential to our being human, being modern – cause one to become lost in the Continuum along points of scale. Besides living on in his poems, the missing poet Craig Arnold (10) persists, for example, somewhere between his scattered atoms and the volcanic island where he fell into an abyss.

Both intensiveness and intensity help construct additional qualities of enfoldedness and reciprocity. As distinct qualities, intensiveness is more toward the here and now of experience in enfolded time. Intensity would be the further exertion of force that causes a collapse in space: a wormhole or a fall into what, further down in this paper, I call the Vortex.

Doreen Massey, For Space

Geographer Doreen Massey (11) speaks of instantaneity – a global, shared sense of time: my present moment parallels someone else’s in another town or hemisphere. I’m living rather intensively in instantaneity: since before the start of the pandemic, my wife, Yukiko, has been in Japan. We’ve maintained the marriage through Zoom calls, finding ways to share a sense of passing and lingering time, moment, occasion, urgency, opportunity, the hour, the strangeness of her night/my morning, even the different weathers and furnishings (and the pets – horses and cats and a remaining dog on my side of the globe) she’s always insisted on keeping. We’ve developed rituals, a vocabulary, and an emotional sensibility different from what we had when we were under the same roof: that quarter-century and more of the first part of our married life, where we were sometimes in our own worlds three strides apart.

It’s a broad latitude between us. On our smartphones we wormhole into each other’s gaze. I’ll call it a mystery: another label for the balancing of tensions between simplicity and complexity. But the mystery draws us also to the verticals of geography: descents of Persephone and Orpheus and those other travelers into lower realms in Homer, Virgil, Dante.

The subterranean spaces are important to me because I’m enamored with the idea of a vast subconscious where we’re more than wandering amnesiacs; and if I find our way down we’ll also find the way up through language, art, spiritual quest, and never be lost again.

The verticality of Missingness is also the tension between hope and hopelessness; except that within the continuum they form, apathy or detachment seems the midpoint, a denial of either extreme. Mythically, perhaps the upward sense is toward hope beyond hope: not that a Missing Person will return alive, but that they don’t suffer in this shared global present, this instantaneity, and might even be on their own path to redemption or knowledge.

Sometimes the downward path is of continued, interminable suffering and wandering or imprisonment, wherein a despair beyond hopelessness is a death without a date, a body without a grave. The underworlds we imagine –ancient Greek and Roman underworlds, quests of heroes and shadows of chthonic gods, provide to Missingness a sense of risk, uncertainty, answer, secrecy – both in suspension with each other – and the elation or despair of return.

All we have to help us imagine those other realms is their imprint on this world of the Middle Distance, where time and space conspire to isolate us. Shobha Rao, (12) in her novel Girls Burn Brighter, illustrates the passage of time as one of her heroines experiences it; time, as the poor & suffering Poornima envisions it, is:

…like the buffalo she saw plowing the fields. All it did was plod along, never wavering and without a thought in its head. Time was all her days in Namburu, and all the days before that. But geography? Now, geography Poornima considered a mystery. Its mountains, its rivers, its vast and endless plains, its seas that she had never seen. Geography was the unknown. (120)

Toni Cade Bambara, Those Bones Are Not My Child

In Toni Cade Bambara’s novel of the 1979 – 1981 Atlanta child murders, Those Bones are Not My Child, (13) we follow the parents Zala and Spence – maritally separated, now brought together again by their son Sonny’s disappearance. Through the novel, Zala and Spence separately leave their Atlanta home to push at the many occult surfaces of the cityscape: places, features, structures that now seem to obscure what signs might point to their son’s whereabouts. It’s not vastness that overwhelms, but the city’s betrayals: its enfolded, puckered, grimy silences. It seems to manifest itself as a form of intensity:

Zala sat down and strung some words together before calling Missing Persons. She rehearsed it quickly as she dialed, reminding herself of the officers’ names. She was fully prepared on the third ring. But what she got was a recording. It said Missing Persons was closed for the weekend and to call Homicide. She held on, frozen, and the message was repeated. Call Homicide. She could not even move to write down the number; her thermometer stuck at zero. (60-61)

The confrontation with a machine, with the bureaucratic time-fold, with the mother Zala’s own paralysis, and then the metaphor – almost a spectral chill – intensify the scene. It’s more than a moment, a stall: within the continual rush or the labyrinthine turning or the resistance to their searching at all levels, these intensified moments in Those Bones Are Not My Child create a stuckness. Though Atlanta has been their home, their own world in so many ways, the disappearance of their son within the broader terror of the disappearances and murders, within the bureaucratic-political hall of mirrors, has turned the parents’ sense of home and community inside out.

Consider the ways the scene in Bambara’s novel constructs the tensions of inner and outer, as well as the competing views (or layers) of reality. The system is not available to answer her call, and its protocols oversimplify experience, or seem to – as if missing vs. murdered were the default continuum of what the mother is experiencing. It doesn’t properly define the space as a person inhabits it with their integrity or their freedom intact.

Bambara’s Those Bones Are Not My Child, written largely in Atlanta, was the author’s great obsession left unfinished at the time of her death in 1995. Toni Morrison labored for years to edit the manuscript for publication. It’s a novel of ambition, scale and depth – and perhaps, less overtly, a novel of the Archive. I give the trope of the Archive an outer and an inner form: the architectural and institutional Archive of authority, officialdom, or the systematic collection and preservation of information; and at the other end, its enfolded form: the banker box, the file folder, the case, but also the trace, the relic, the fragment, the clue, and (as a fusion of the large and compact forms) the solo Searcher’s obsessive journeys through the world and herself – not only seeking, making, and refuting maps, but also trying to enter the map: to read the signs of Missingness so well, the Searcher finds what she seeks, or dreams more vividly than the eye can see of finding it – despite or because of the ways Authority hinders and neglects.

In Disequilibria, I work with a pair of essential tropes: Circumambience and The Middle Distance. Circumambience is the zone between a person and their immediate social-physical sphere; we move in it, carry it, are carried by it, sharing our textures, sensorium, noise, emotional resonances, and more. The Middle Distance is everything that meets us at our thresholds, which vary greatly in terms of thickness, resistance, scope, or absorption of time-space. It’s the Social, but also the Wilderness, the City, the Nation – all tropes of Missingness, in that they represent varying ways we might disappear. (14)

Archivists in Canada created the “Records Continuum Model” (15) as a spatial grid that captures the continuum of the Archive in a more two-dimensional expression. Across the axis of Dimension, Transactionality, Evidentiality, Recordkeeping, and Identity, we can compute the rest of the grid by transecting that horizontal continuum with a vertical set of archival actions: to Create, to Capture, to Organize, and to Pluralize.

This grid, on paper or in practice, seems another form of the Memory Palace as much as a scheme or protocol. It’s an imaginary space realizing itself in ways that admit the user entry into the Archive as both expansive and intensive: reach and expansion, but also indwelling or contemplation. Its basic parameters loosely fit the theoretical understanding of space we find in Henri Lefebvre, Edward Soja, Doreen Massey, and other place-space geographers and theorists. (16) Also, the enfolded nature of the Archive is reciprocal: one can imagine the figment, the fragment, the trace, the single-significant document, the folder, the box, the shelf, the row of boxes long and high and deep, the vast rows, high stacks, shadowy, seeming-endless chambers, and overflowing boxes of the architectural space. The RCM starts small and local in time and space, but expands and deepens – in time and space, both – to name and order the growing layers. Within the Memory Place, the Archivist as well as the Searcher inhabit all scales.

As mentioned above, I’ve had a recurrent dream of the Memory Palace: over many years, the recurrence of a pre-plastic, organic, early-modern, labyrinthine, architectural, old, persistent but seeming-unstable, generally-domestic space – asymmetrical, endlessly contingent – somewhat like the Winchester House in San Jose, California if designed by the firm of Piranesi & Escher. Each iteration of the dream has been a random journey – a search and serendipitous discovery of treasures and puzzles. Our search for my stepfather in the Archive has included his military records, the drawers and closets of his effects that my mother eventually compacted – though she has left two drawers in the ancient chest in the master bedroom that are something of a crypt for the man; and all that my brother and I have gathered of legal and law-enforcement records, flight records, memory and gossip of my stepfather’s brothers-in-arms, similar cases of haunting similarity, the NamUs page (17) we set up with his medical files, fingerprint records, DNA results, other vitals, a compact version of his narrative, and the case summary. So much of our searching has been not into the (likely) posthumous life of James Lewis, but into the life itself – including his life as a soldier, since we suspect his moral injury, or at least his self-definition as a warrior, holds clues to his fate.

The many wormholes we’ve explored include what remains of the cassette tape-letters our family sent back and forth when Lewis was in Vietnam for his final tour in 1969-70. Beyond the search for answers about his fate, those tapes revealed Lewis’ whereabouts on a emblematic continuum of History. In his 143 letters home during that tour of duty, which I read and studied obsessively (they were a temporary gift from my mother, folded into the Danish cookie tin where she’d kept them for decades), there are traces of the man in his handwriting, sweat-stains, musings, non sequiturs, instructions to his wife and children, and war-gossip; but in the tapes, there’s a dark wealth of other information: his youthful voice, his weariness, his ardent love and sternness, his pillow talk (including what amounts to classified information, at one point), but also, the ambient sounds coming from that very-local space and moment: mortar fire, automatic-weapons fire, fighter jets flying above his tent, helicopters, and once or twice, his mention of sounds that leave no trace on the tape: “Charlie” (18) dying yards away on the perimeter wire.

I believed to have found the man, in a sense – in the past, on magnetic tape, in what remains of a moment in time, on a clear, inveterate ray from Vietnam to our Fayetteville kitchen, where we kept a newspaper-map of that far-away place to mark his whereabouts and doings.

Jessica Pearce Rotondi, What We Inherit

In a memoir about her missing-in-action uncle, Jessica Pierce Rotondi (19) accesses the Archive in various ways. Her memoir has the nested structure of recounting her grandfather’s POW experience in the Second World War, then her grandfather’s and her mother’s search for the author’s uncle during the American War (specifically in Laos) in Southeast Asia. “I feel closer to them,” Rotondi says of her mother and grandfather, “when I lose myself in their papers” (43). Her mother, like many Americans in that era, had worn a bracelet with her brother’s name until it broke in two. (20) Rotondi’s grandfather had gone to Laos himself in the early years after the war; her mother had continued the family’s search, and Rotondi herself, after the turn of the millennium, also traveled to Laos in search of her uncle.

Rotondi’s travel experience was not only a journey into the World, but a bringing of the World into the body: “In the copy I later hold in my hands,” she says in preparing for her journey, “my grandmother has underlined a phrase from that report: ‘the possibility of their survival still exists,’ the pencil line nearly ripping through the paper” (143). The force of the image is a sign of how trauma is the persistence of violence, but also of our resistance to loss.

Besides the MIA bracelet, we have as a specific trope of the warrior’s fate the more common, equally palpable dog tags. “There is a difference, Ed [Rotondi’s grandfather] was discovering, between hearing that your son’s dog tags have been located and holding them in your hand” (194) – not only, I suppose, because the effects are already in the Archive (in the hands of a military investigator, let’s say), then they are not the same relic, metonym, or fragment of a person as when you feel the weight and stainless steel of the tags themselves.

Rotondi’s grandfather also sought after an even more-intimate relic of the missing son: “The government was going to send that tooth,” he told a reporter, “in a seven-foot coffin, flag-covered.” It’s evidence to the grandfather of nothing more than his son’s presence at the crash site in Laos: “A front tooth doesn’t mean a man is dead” (211). (21)

Perhaps the most important recent major work of fiction to develop this trope is Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive. (22) The novel is structured as a series of file-boxes; it’s also a Quest and Road Trip, as a married couple, each with a child from a previous marriage, head West and South for different, though overlapping, reasons (encountering other purposes along the way). Both parents are archivists: the husband is collecting audio specimens of the Apache people and their past; the wife is more urgently seeking evidence of a friend’s children, who went missing after attempting to cross the US/Mexico border. Each family member, including the two children, have notebooks and boxes. The novel itself is structured, mise en abîme, as a series of file-box chapters from the boxes that the family has carried along in their car, from which and into which the journey, the novel, and the world of Missingness fold and unfold.

Valeria Luiselli, Lost Children Archive

Lost Children Archive is very much a Borderlands novel: a world of people crossing and inhabiting the desert, getting lost and found and dying in the border regions, but also in the cultural/social spaces, the cities, jungles, and elsewhere-spaces far from the border itself. (23, 24)

A more-recent work of fiction by Kalisha Buckhanon, Speaking of Summer, (25) uses the Archive in a less overt manner, but still explores the continuum between interior/exterior and the connections between somatic and architectural spaces. In Buckhanon’s novel, one sister named Autumn searches for her missing twin, Summer – in some of the typical ways, which include papering the upper-Manhattan city streets and venues with Missing posters. At home, Autumn searches their shared apartment:

I had left Summer’s fingerprints on her dressing mirror. I joyfully borrowed her clothes. If I breached her journals or notes or emails, I heard her voice saying her old words and I felt better. I washed her scent from her pillowcases, sheets, and comforter. I switched her bedding and moved in to her room, to feel she was still here. My bedroom, the smaller one facing the brick gangway, never invited the breeze. Now it was just my dressing closet, in need of a good sweeping and dusting. The comforter crumpled and twisted at the foot of my Ikea bed. (21)

How Autumn inhabits space is thus transformed, knocked out of balance, since she believes her twin is missing. I see further (here and in other passages) how Buckhanon allows perception and belief to take up space and take on bodies:

It felt spooky to dip my hands into thatched dark bamboo cubes where Summer kept odds and ends in her living room workspace. I remembered her in there, on stained beige sheets, curled cross-legged in the corner or on her stomach. Our candles and incense mostly covered the smells of her pastime: not just paint, but the enamel and glues. I kept her unfinished statement in that space. She shredded fashion brand names and labels she cut from stacks of magazines. She glued them to canvas and spray painted them in light metallic tones. She was just half done on the side where she managed to rubber-cement scraps into texture and grade. It was part of her efforts to join the natural and “meaningful” art crowd, to be more politically and less personally focused, to go the direction the art blogs and dark bar small talk told her to if she wanted notice. I didn’t get it. I liked her less flashy work with faces, as damned and disgruntled as she intended them to be. (26)

Kalisha Buckhanon, Speaking of Summer

This passage is a further stage of the embodiment/spatialization of the missing/nonexistent sister; it’s more textured, detailed, vivid, broken – and includes the sister’s supposed writing as well as her visual art. But by the last third of the novel, we and Autumn realize it’s she who is the artist – not “Summer” (spoiler alert: the twin is nonexistent), but she has all her life bequeathed that gift to her imaginary sister.

The Vortex is another trope of Missingness: perhaps a form of Roland Barthes’s punctum, (26) or the intensified point in the photographic studium or plane – but also in the field of the photographable world along one’s path, within the story of one’s movements through time and space. From another view, the Vortex is intensity: a point where the multiplicity of stories, vectors, choices, striations, movements, perspectives, power structures boil over, become turbulent, create feedback.

Obsession itself is a take on the Vortex. This writing, the mission I’m on, the parallel but differently-keyed obsession of my brother – they’re the vortex we’ve entered and have lived within for most of our lives. In Bambara’s Those Bones Are Not My Child, mother Zala’s obsession is nested within the field, or rather the mythic cityscape, of Bambara’s version of Atlanta: city of lost children within the novel that the author never finished.

When we enter the Vortex, or otherwise lose balance in our movements through the world, in the adjustments along our sightlines into the Middle Distance, or find the world below rising to meet us, find ourselves sinking into it; perhaps we become ghosts, or feel instead that everyone else is spectral, atmospheric. The ghosts are ambiguities, breakdowns in the sensorium.

Is Persephone’s abduction into the underworld by Pluto through a Vortex, and does her mother Demeter seek her through the same or a different Vortex? Is initiation into the mysteries an encounter with the Vortex: where the reciprocities of inner and outer, near and far, become too powerful within our Circumambient movements?

I take it also to be a point in one’s life, after a crisis, a loss, a breakdown, when the sense of place and occasion – of the rightness of time and one’s fit in time as well as space – seems to have gone awry. The flow of things becomes turbulent. Perhaps the vortex is a state that can last long – years, a life time; perhaps sometimes it’s momentary and local.

We’re alive to, if not always aware of, interpenetrations, what I’ve called the reciprocity, of place and space. The sociologist Georg Simmel, studying the modern urban experience in his essay “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” (27) observes:

Man does not end with limits of his body or the area comprising his immediate activity. Rather is the range of the person constituted by the sum of effects emanating from him temporally and spatially. In the same way, a city consists of its total effects which extend beyond its immediate confines. (418)

I note Simmel’s emphasis on both time and space, but also the distinction between “Man” (person) and “body,” and the near-metaphor of emanation – near, I think, because it seems meant to be taken as a literal energy of the person coterminous with the body, or Circumambience.

Might it also be a quality of the collective, transformed, urban environment itself – both sides, the core of circumambience in the body, the sphere of one’s reach and desire (and the undertow of fear) into the Middle Distance?

Celeste Ng, Our Missing Hearts

Ubiquity as a trope of Missingness has several values: one is the sense, on the part of the Left Behind, that the Missing Person is both nowhere and everywhere. Within the trope of Ubiquity in that sense, we have several lesser tropes (that, again, in our combinatorial scheme, are higher-level from other perspectives into the field). One of the more interesting of those lesser tropes within Ubiquity is the Sighting, as in Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts, (28) about a near-future, racially-dystopic America in which a boy nicknamed Bird searches for his mother, whose writings have made her an enemy of the state.

The sighting-as-ubiquity is perhaps a vortical confusion of near and far. Bird searches everywhere within his own abandonment, his mother’s truth-telling, his father’s equivocations, and society’s abjections, for his mother: in traces, fragments, conspiratorial alignment, for signs of identity and familiarity:

Sometimes when he sees sleeping figures huddled on the sidewalk, he scans them, searching for something familiar. Sometimes he finds it — a polka-dot scarf, a red-flowered shirt, a woolen hat slouching over their eyes — and for a moment, he believes it is her. It is easier if she’s gone forever, if she never comes back. (7)

Bird knows it’s nearly impossible to find one human in a vast, many-layered, mainly-striated space, (29) but he looks anyway: over his shoulder, all around him, as if his mother might be lurking behind a tree or a bush. Hoping for her face in the shadows. But of course, there’s no one there. Isn’t his audacity in part due to the child’s confusions of scale and distance?

The Sighting is diametrical to an inner search that is generally a form of Magical Thinking (a Missingness-trope I discuss in Disequilibria): the mental games we play to tip the balance of fate, to allow in whatever our conscious mind, our rationality, can’t compute. (30) It’s often in the form of a game:

After his mother left, for months he would lie in bed at night, certain that if he could stay awake long enough, she would return. He was convinced, for reasons he could never explain, that his mother came back in the night and disappeared by morning. By sleeping, he missed her each time. Perhaps it was a test — to see how badly he wanted to see her. Could he stay awake? He imagined his mother, each night, standing over his bed, shaking her head. Again he was asleep! Again he had failed the test. (122)

Haunting, or the Ghost, is another Missingness trope. It intersects with the Double in establishing a dynamics of difference and similarity within ratios of one to the other. Several recent novels and memoirs by women use doppelgangers, sisters, lovers, mothers/daughters, or enduring friendships to frame the spaces of Missingness. (31) Again in Shobha Rao’s Girls Burn Brighter, the two heroines, Poornima and Savitha, are born very poor in India and subjected to horrid forms of abuse by men. They become close friends; Savitha is taken away, and the novel tracks Poornima’s epic search for her friend across continents. The Missing Woman is a form of living Ghost, in that she charges the Circumambient space of the Searcher in such a way that the latter is driven into the Middle Distance and beyond:

What Poornima liked most about Savitha – in addition to her hands – was her clarity. She had never known anyone – not her father, not a teacher, not the temple priest – to be as certain as Savitha was. But certain about what? she asked herself about bananas in yogurt rice? About sunrises? Yes, but about more than that. About her grip on the picking stick, about her stride, about the way her sari was knotted around her waist. About everything, Poornima realized, that she herself was unsure about. (20)

Shobha Rao, Girls Burn Brighter

As a form of the Ghost, this sought-for presence is heightened, vivid, perhaps more real than the subject herself. But also, this emphasizes a quality of figuration overall, and in particular, the Archive in its details, fragments, relics, objects, parts are the sources of meaning more than things we consider in their whole forms. (The richness of Rao’s novel, I’ll add, is largely in the ways she frames her two women within vivid landscapes, both in India and the American West.)

The artist seeks the link between part and whole, resolution of their dialectic. In Rao, a classic women’s emblem – weaving, textiles – represents that link: Rao returns frequently to a torn piece of sari that Poornima cherishes as an emblem of her missing friend, Savitha. Early in the novel, before their separation, she imagines the garment itself:

But Savitha, Savitha wanted to make her a sari. A sari she could wind around her body and hold to her face. Not a memory, not a scent, not a thing that drifts away. But a sari. She could take that sari and weep into it, she could stretch it across a rooftop, a hot sand, wear it to the Krishna and wade into its waters, she could wrap herself in its folds, cocoon herself against the night, she could sleep, she could dream. (39)

Avery Gordon, in Ghostly Matters, a study (in large part) of the literature of the Argentine Dirty War and its enforced disappearances circa 1974-83, defines the Ghost:

We have seen that the ghost imports a charged strangeness into the place or sphere it is haunting, thus unsettling the propriety and property lines that delimit a zone of activity or knowledge. I have also emphasized that the ghost is primarily a symptom of what is missing. It gives notice not only to itself but also to what it represents. What it represents is usually a loss, sometimes of life, sometimes of a path not taken. From a certain vantage point the ghost also simultaneously represents a future possibility, a hope. (63)

Critics not drawing overtly on place-and-space geography can’t help resorting to topographic figures. The Ghost, like the Missing Person, is everywhere and nowhere; but in the decades of my own searching, I’ve sought for ways to simply bring him home.

This is a bare start on my list of tropes. Several more are developed in Disequilibria, but I expect this paper to lead me toward a more expansive, systematic, second project. I don’t see a true Missingness Studies as yet – but among those whose works seem to be foundational, I can name: the afore-mentioned Gordon Avery and Daniel Heller-Roazen, Karen Elizabeth Bishop in The Space of Disappearance, Diana Taylor in Disappearing Acts, Kristen Pitt in Body, Nation, and Narrative in the Americas, Andrew O’Hagan in The Missing, and, in various works, Michael Taussig, Hisham Matar, Jean Baudrillard, and Paul Virilio.

I’d also love to see how the thinking of space-and-place geographers like Yi-Fu Tuan, Doreen Massey, Edward Relph, Edward Soja, Robert Tally, Bertrand Westphal, et al. might further illuminate Missingness Studies. I invite all who read this to reach out to me with ideas, theories, suggestions of primary works, other tropes, and intersections into other fields of study.

Notes & References:(1) Also, I’ve explored the Internet and social media, and the forms of lore one finds these days: how we experience the layers of sensibility, belief, irony, camp, meme-streams, conversation, threads, the voices in one’s head, or voices in flesh-and-blood or digital mobs.

(2) Lunday, Disequilibria: Meditations on Missingness (University of New Mexico Press, 2023). See also my blog at https://robertlunday.com

(3) See Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (Beacon Press, 1994; trans. Maria Jolas).

(4) See, for the most recent and most thorough exploration, Daniel Heller-Roazen’s Absentees: On Variously Missing Persons (Zone Books, 2021). The long quotation is from Heller-Roazen’s translation of Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford University Press, 1998).

(5) See Atul Gawande’s The Checklist Manifesto (Metropolitan Books, 2009) for a useful distinction of the simple, the complex, and the complicated.

(6) John M. Cooper, Plato: Complete Works (Hackett, 1997).

(7) Seneca, Physical Science in the Time of Nero, Being a Translation of the Quaestiones Naturales of Seneca (Macmillan, 1910; trans. John Clarke).

(8) Gomel (Routledge, 2014).

(9) Getting Back into Place: Toward a Renewed Understanding of the Place-World (Indiana University Press, 2009), 58.

(10) Besides his poetry, I recommend the blog posts Arnold logged during the fateful voyage: https://volcanopilgrim.wordpress.com/

(11) Massey, For Space (Sage, 2005), 76.

(12) Rao (Flatiron Books, 2018).

(13) Bambara (Vintage, 2000).

(14) These concepts are a bit like Pierre Bourdieu’s concepts of Habitus and Field, I admit; see, among other sources, Outline of a Theory of Practice (Cambridge University Press, 1977; trans. Richard Rice).

(15) Thanks, for now, simply to a catch-as-catch-can Google search and the always-on-top Wikipedia result: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Records_continuum_model

(16) See Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Blackwell, 1991; trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith); and Soja, Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory (Verso, 1989), among others.

(17) See https://www.namus.gov/MissingPersons/Case#/32471?nav

(18) GI slang for the Viet Cong, or soldiers of the NLF.

(19) Rotondi, What We Inherit: A Secret War and a Family’s Search for Answers (the Unnamed Press, 2020).

(20) Though he was dead, not missing, my first father’s Montagnard bracelet was on my wrist for thirty years. It had been given to then-Captain Lunday when he was a Special Forces advisor to the Montagnards; I removed it when I saw that my years-long nervous flexing of it had worn the brass down to the width of a bit of twine.

(21) In Disequilibria, I consider the possible meanings of remains: if, for example, a jaw bone means a death more than a leg bone, as two true-life cases pose the problem.

(22) Luiselli (Knopf, 2019).

(23) The classic borderlands work is Gloria Anzaldua’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (Aunt Lute Books, 1987): “A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition. The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants” (25).

(24) Including my neighborhood, Houston’s East End, where every day I see the Autobuses Lucano arriving and departing for various destinations in Mexico from a nearby restaurant-depot.

(25) Buckhanon (Counterpoint, 2019).

(26) See Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (Hill and Wang, 1981; trans. Richard Howard).

(27) Simmel, The Sociology of Georg Simmel (The Free Press. 1950; trans. Kurt H. Wolff).

(28) Ng (Penguin Random House, 2022).

(29) For an explanation of straited vs. smooth spaces, see Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (University of Minnesota Press, 1987; trans. Brian Massumi).

(30) Soon after my stepfather’s 1982 disappearance, having returned to Manhattan, I came across a Brooklyn boarding-house owner/psychic who escorted me to an upper-eastside Manhattan apartment where priests of St. Germain played what they claimed was a blank cassette tape through which the spirit of St. Germain spoke riddling words. The priests interpreted them to mean my stepfather was languishing in a South American prison. Even if by accident, they might have been right.

(31) Besides Buckhanon and Rao, see Betsy Bonner, The Book of Atlantis Black; Kelly Grey Carlisle, We Are All Shipwrecks; Debra Magpie Earling, Perma Red; Abi Maxwell, The Den; Julia Phillips, Disappearing Earth; Erin Kate Ryan, Quantum Girl Theory.

The post ALSCW Paper: “Mystery and Missingness: The Literature of Disappearance” appeared first on Robert Lunday.

March 18, 2023

Thoughts on Jessica McDiarmid’s Highway of Tears

Indigenous women in North America disappear at ten times the rate of the general population. Cases tend to occur in Canada along Highway 16 in British Columbia, in the Pacific Northwest, and in the Dakotas, but the crisis is ongoing everywhere.

The causes are various, but include a longstanding attitude of neglect on the part of whites and of white-dominated institutions in national, regional, and local governments, including law enforcement; and lack of agency in most areas of individual and communal life — such as limits, on reservations in the US, of true law-enforcement authority over non-natives who commit crimes on native-owned lands.

Drugs, alcohol, domestic abuse, and sex trafficking are key influences on the high rates of violence and disappearance, but probably nothing exerts a darker, more powerful influence than the historical and ongoing neglect of Native peoples — the centuries-long project of diminishment, theft, appropriation toward extinction that has nonetheless been resisted in its intended absoluteness through the courage of individuals — women and men alone and in concert, defining and redefining community, in part by redefining stories told about the past.

Missingness is a potential condition of the individual: someone goes missing, is missed, is sought for or not sought for. But missingness is also a cultural frame: before humans identified as individuals, we were persons in families, clans, tribes, societies, nations.

Personhood, for me, is the delicate, lively space between the single self and the nurturing/threatening world beyond the skin, the voice, the circumambience we create singly as we walk through the world. Personhood existed before we were individuals with rights; it exists as well beyond the human, defining anyone with consciousness or a will to live.

So, missingness, I am starting to believe, is an evolutionary concept: it matters more for individuals than for persons. Persons are not missed so much as we are remembered, honored, reviled, forgotten, met in dreams or visions, memorialized in story or stone. It is the individual, the person with rights, who goes missing; we each have our roles, our rights/responsibilities, and we’re missed to the extent that we are removed from our familial and social interactions.

I listened to an Indigenous man at the AWP conference in Seattle last week. Here I will make him anonymous, but the man was past seventy, tall, softspoken, though clear-eyed and direct. He told me he was writing about his experience as a boarding-school student — as a child taken away from his parents and forced into one of the “Indian schools” that were common throughout much of the last century. His parents, he said, weren’t told of his whereabouts, and were not given agency over their son. Years later, when these schools were gradually closing, he said that the other students and staff simply started disappearing. No one told the remaining students why others were gone, or to where they had been taken. Eventually, he, too, was taken away, back home — but without acknowledgment of the fact of his abduction or the rightness of his return.

It strikes me that such an experience is a denial of both someone’s individuality and their personhood at the same time. It’s one of the further layers of missingness, missing-missingness, in which it is denied that a person can even be considered missing — that anyone would want to search and find the person.

Acts of terror often exhibit that type and degree of maleficence: to harm, to cause suffering, with intimation that the experience, terrible as it is, could be worse — will be worse — in part, from not being acknowledged at all.

Jessica McDiarmid’s Highway of Tears is an account of the scores of missing Indigenous girls and women whose cases were generally ignored over the past few decades, but whose collective cause has been championed, largely by native families and women in Canada, though with a slow, eventual increase of attention from government and law enforcement.

Jessica McDiarmid’s Highway of Tears

McDiarmid focuses with great care on the identities of the missing women and girls: who they were, what they looked like, how they struggled, what they loved, who loved them, misses them, and is searching for them. The author also provides historical and statistical context, in a mainly-journalistic account that doesn’t often reach for what I think of as the mythic or cosmic dimensions of the experience — which is fine; the book’s purpose is to document, frame within greater discourse, acknowledge and honor the actions and virtues of the people, mainly women, who have made the crisis a matter of general urgency — to make the missing women missing, as much as to find them one by one.

Deborah Halber, in her The Skeleton Crew: How Amateur Sleuths Are Solving America’s Coldest Cases (which I will discuss in more detail in a later post), creates a compelling, if small, image in one of the accounts she gives of a forensic specialist researching an unidentified homicide victim. Agencies across the land use different protocols, tools, methods; there is (in the US, anyway) no central system for working with unidentified remains (though NamUs is a large step in the right direction). One investigator chooses particular-colored Rubbermaid bins for storing the remains she’s working on; one unidentified woman is given a purple bin — a gesture toward her personhood, beyond protocol, but toward some recognition of who the bones belonged to — lacking name or narrative, but anchored by the seemingly frivolous choice of color.

McDiarmid’s clear prose also provides color and form for the girls and women she’s seeking:

Delphine, about three years older than Kristal, was fiercely protective of her younger friend. She made sure Kristal went to school and was headed home by curfew. She steered Kristal away from situations where, Kristal came to suspect years later, people were using hard drugs. During the daytime, while Kristal was cooped up in school, Delphine wrote her long letters. She copied out the lyrics of her favorite song, Tom Petty’s “Apartment Song,” for her friend. She wanted to get her own place when she turned sixteen, a spot in the world that she could call her own.

This is seeming-simple: in its directness, the prose evokes the personhood and the individuality — the gestures, choices, desires, fears, hourly and daily living that, combined, represent who and what is lost. More than the single person, it’s the relationships, the might-have-beens, the alternate lives, the promises held within the fullness of a life.

Some time ago, I read Adam Phillips’ Missing Out: In Praise of the Unlived Life along with Andrew H. Miller’s On Not Being Someone Else: Tales of Our Unled Lives. These works have circled back in my social-media streams, as well as in real-life conversations. Revisiting my reading notes, I find that the general idea of the alternative life, the possibility of lives within a single life, is essential to my thinking on personhood and individuality — and to the limits of individuality in our understanding of who and what we are as living beings. (More on that in a later post, though.)

Still, what strikes me about the objective-yet-compassionate prose of MacDiarmid is that she uses her skill and training as a journalist and writer to construct a vision, despite the submergence of symbol and myth (as I read the book, anyway); that the persistent, steady gaze itself composes a vision of life that is balanced between those lost women and girls, each one accounted for as carefully as possible, and the broader community and world from which they’ve gone missing.

Having read the book, you, too, miss them; their disappearance frames your world, perhaps not with the same urgency, distress, or outright trauma, but with some sense of the dread that curves over the path that lies ahead for everyone.

Highway 16 in British Columbia is representative to me of the vastness, but also the intimate enfoldedness, of the world — of the ways wilderness is without and within. Practically speaking, a key element of its danger is that many people traveling its length have little choice but to hitchhike. They lack their own vehicles — a core part of individualism in our era — and the system does not provide practical public transportation for daily comings and goings. Not too far along in a journey along its stretches, the traveler is swallowed by true wilderness and human aloneness.

It’s an emblem of the danger of the near and the far — that we succumb, sometimes, not only to the greatness of the world, but to the unrelenting nearness, nowness, and immediacy of our lives. One evil man crossing your path in a wilderness is more terrible than the demons we meet elsewhere; it — he, usually — has the power to embody all the inhumanity of that wilderness before the traveler’s small presence.

I’ll return to MacDiarmid, and to MMIW accounts and works, in later posts. Coming soon: Acts of Imagination beyond art in the scholarship/activism of Annita Lucchesi, cartographer —

Meanwhile, look for Disequilibria — it’s been released into the publishing wilds!

The post Thoughts on Jessica McDiarmid’s Highway of Tears appeared first on Robert Lunday.

February 25, 2023

A Facebook Post that Became Too Long for a Facebook Post

I started writing something for a Facebook group dedicated to cold cases. Within a few sentences, I saw that I was caught up in a logorrheic effort that wouldn’t work as a Facebook post. It repeats, though within a different frame, some parts of Disequilibria .

*

Hello, Fellow Cold-Casers!

I’m here for a few reasons and would like to put a few of them before the members of this new Facebook group.

First, a personal motivation that I share with many in this group: I have a loved one who has been missing many years. James Edward Lewis, my stepfather, a Vietnam veteran and pilot, disappeared in 1982. To date, there is no resolution, though there are fragments of information pointing in a certain direction.

My youngest brother and I have made a NamUs record for JE Lewis. He’s included as well in other online databases (Veteran Doe, for one).

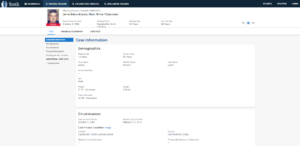

James Edward Lewis’ NamUs file.

Second, as a writer and researcher, I’m interested fundamentally in the ways people create meaning and purpose. I’m also interested in how we get outside our own missions (or obsessions) to have conversation with other mission-driven, obsessed individuals – especially across differing sensibilities, beliefs, professions, ways of living, or cultural differences.

In something so abject, so uncanny as long-term disappearance, how do we create shared language, shard space, shared opportunity? It’s one of the promises of the digital world, of social media – one that mostly fails, I think. Perhaps in a particularly intense experience like missing persons, the promise will have more fulfillment.

Third, I’m interested in how people process missingness within their daily, yearly lives: how do you live with grief, ambiguous loss, doubt, anger, trauma, obsession, moving on, the effort at searching or waiting – or, alternatively, the refusal to let the experience take over one’s life?

Fourth, I’m interested in how the Internet, social media, technology, advances in professional practices, and scholarship, along with concomitant real-world changes (the increased number and kind of groups for support, search, advocacy, etc.) have altered the very nature of long-term missing persons (and the experience of missing persons generally – given that roughly 98% of reported cases are resolved in the short term, happily or tragically).

Anyway – here is a peek into my family’s own MP experience, with a focus on the possibilities of digital research, online happenstance, and sheer luck – or the rewards that sometimes come from desk-chair perseverance:

Over several years, my youngest brother and I have worked together – mostly through email and text— in searching for our father, JE Lewis (my stepfather, my brother’s biological father). My brother is a smarter, more active, methodical searcher; I focus on the philosophical meanings of the experience, I suppose.

Still, I am fascinated by the possibilities of digital searching. Some years ago, my brother, in his persistent Web browsing, found a message on the Websleuths forum that offered some digital-detective work on James Edward Lewis. The Websleuths poster had no direct involvement with Lewis or our family; they (I have only a screen name) had dug into some Archive.org-based FBI documents that mentioned details pointing (very indirectly and tentatively) to Lewis’ fate.

The Websleuths message-thread on Lewis.

“James Edward Lewis”: on the Internet, that combination of names leads a Googler to many, many results, and almost none of them about our James Edward Lewis. So, it was raw luck that led my brother to that Websleuths post.