Steven Johnson's Blog, page 2

September 16, 2012

Future Perfect Tour

Tuesday, September 18 -- MARIN

7:00 PM

Book Passage

51 Tamal Vista Blvd

Corte Madera, CA 94925

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19 -- SEATTLE

7:30 PM

Town Hall Seattle

1119 8th Avenue

Seattle, WA 98101

Sunday, September 23—Washington DC

5:00 PM

Politics and Prose

5015 Connecticut Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20008

Monday, September 24—New York

7:30-9:00 PM

Personal Democracy Forum event at New York Law School

In conversation with Clay Shirky, Tina Rosenberg, Beth Noveck and Micah Sifry

Information and tickets available here

Friday, September 28—Boston

7:00 PM

Harvard Bookstore

1256 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

Tuesday, October 2—Portland

7:30

Powells Books

1005 W. Burnside Street

Portland, OR 97209

Wednesday, October 3—New York

In Conversion with Sherry Turkle

7:00 PM

New York Public Library

5th Avenue at 42nd Street, New York, NY

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 11 – SEBASTOPOL

7:00 PM

Sebastopol Community Church

Hosted by Copperfield’s Books

1000 Gravenstein Highway North

Sebastopol, CA 95472

Monday, October 15—San Francisco

7:00 PM

In Conversation with Wired’s Bill Wasik

JCC of San Francisco

3200 California Street

San Francisco, CA 94118

August 27, 2012

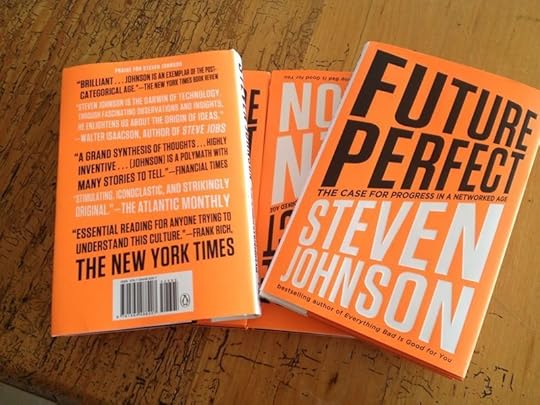

First reviews for Future Perfect

A couple nice early reviews of Future Perfect have come in over the past few weeks: Publishers Weekly calls it "fascinating and compelling" and says "Johnson’s thought-provoking ideas steer us steadily into the future." (Full review here.) The Kirkus review is not online yet, but they call it a "thought-provoking, hope-inspiring manifesto." And it's made a bunch of top fall books lists, which is always nice. The tour is shaping up nicely, and I'll have more info on specific dates and appearances in the next week or so.

Almost as exciting: I received the final copies in the mail last week, and the cover is an unmissable orange:

July 26, 2012

Introducing Future Perfect

Emergence was not explicitly a book about politics or social movements, but I wanted to end it with a hint of those possibilities. And so the final pages included a description of the Seattle anti-WTO protests that, reading them today, could just as easily have been a description of Occupy Wall Street:

It’s almost impossible to think of another political movement that generated as much public attention without producing a genuine leader—a Jesse Jackson or Cesar Chavez—if only for the benefit of the television cameras. The images that we associate with the protests are never those of an adoring crowd raising its fists in solidarity with an impassioned speaker on a podium. That is the iconography of an earlier model of protest. What we see again and again with the new wave are images of disparate groups: satirical puppets, black-clad anarchists, sit-ins and performance art—but no leaders. To old-school progressives, the protesters appeared to be headless, out of control, a swarm of small causes with no organizing principle—and to a certain extent they’re right in their assessment. What they fail to recognize is that there can be power and intelligence in a swarm, and if you’re trying to do battle against a distributed network like global capitalism, you’re better off becoming a distributed network yourself.

In the months and years that followed the publication of Emergence, a number of readers took these political undertones and amplified them. (This is one of the beautiful things about writing books, particularly idea books: your readers are free to take your ideas and push them in all sorts of directions you never anticipated.) First Joi Ito—now, wonderfully, the head of MIT’s Media Lab—published some online musings on what he called “emergent democracy”-- asking a series of probing questions about how these principles could be applied to civic life. In Brazil, a number of city leaders used the book to refine the already innovative systems of participatory budgeting that they had pioneered a decade before. Emergence inspired some of the early crowdfunding strategies employed by the Howard Dean campaign in 2004.

And so, over time, a book I had written about social insects and video games and software algorithms started to feel more and more like a book about politics that happened to employ an extended metaphor of social insects and video games and software algorithms. And the more I looked, the more examples I found of this new view of social change in the world, and not just in the decentralized protest movements of Occupy and Arab Spring. All around me, it seemed, people were using decentralized peer networks to solve problems -- and not just express their outrage -- sometimes using software and computer networks, and sometimes not. You could see it at work in New York’s 311 service; in Kickstarter; in the prize-backed challenges of the Obama administration; in Beth Noveck’s peer-to-patent system; in the growing adoption of participatory budgeting around the world; in new forms of corporate organization that were less hierarchical in nature.

The funny thing about this new movement was that it didn’t readily fit the categories of either political party in the US. Because it favored decentralized, bottom-up solutions, it broke with the statist, Big Government solutions of the Left, and yet it looked nothing like the free market religion of the libertarian Right. And it wasn’t the moderate’s safe middle ground between those two poles. It was something altogether new. And more that that, it was a political worldview with a real track record of practical success. In an age of great disillusionment with current institutions, I thought, here were individuals and groups that could inspire us, in part because they had attached themselves to a new kind of institution, more network than hierarchy--more like the Internet itself than the older models of Big Capital or Big Government.

And so I wrote a book about that movement, a book that hopefully conveys some of the promise and possibility—and even outright optimism—that these new ideas carry. It’s called Future Perfect: The Case For Progress In A Networked Age. In the U.S., it will be released September 18th; in the UK, October 4th. (Other foreign editions will roll out next year.) I hope you’ll check it out, and, like the readers of Emergence so many years ago, you’ll take the ideas and run with them—as long as I can follow along.

March 16, 2012

Why The Bay Area Needs The Bay Lights

For a few months now, I've been talking to my new neighbors here in California about my old friend Leo Villareal's proposed epic installation on the Bay Bridge, commemorating the Bridge's 75th anniversary and the completion of the new East Span in 2013. You can find more about it here, including some great visualizations, but the shorthand description from the promotional site is this:

Created with over 25,000 energy efficient, white LED lights, it is 1½ miles wide and 500 feet high... The Bay Lights is a monumental tour de force seven times the scale of the Eiffel Tower's 100th Anniversary lighting.

There's been a lot of buzz about this project, and it seems like it has a very good chance of being made thanks to the $3M challenge grant they've received. This would be terrific news. There's no question in my mind that The Bay Lights would become an iconic example of grand urban art: a digital-age Gates or Wrapped Reichstag. Visually it will be intoxicating, I have no doubt. But I think there's an important element to The Bay Lights that makes it uniquely appropriate to the Bay Area context. Leo is an environmental/algorithmic artist. Leo's installations are, literally, programs. There are many interesting artists tinkering with software and human interfaces now, but most of their work lives on the screen or in a browser. Leo's code lives outdoors, on a grand scale. He writes software for cities, not screens.

So I can't think of a better way to celebrate the bridge at the heart of the Bay Area than with an immense work by one of the most acclaimed algorithmic artists of our time. The world capital of code should have a coder/artist as its Christo. Let's make it happen.

December 14, 2011

Anatomy Of An Idea

People often ask me about my research techniques. You would think this would be a relatively straightforward question, but the truth is that I have to keep changing my answer, because my techniques are constantly shifting as new forms of search or discovery become possible. Right now, I'm in that thrilling stage of writing-while-still-researching my next book, and I just went through a little episode of discovery that I think might be worth mapping out, as a case study of how ideas come into being, at least in my little corner of the world.

The subject matter of the book is not all that important here, but suffice it to say that I am currently working on an introductory bit that contrasts old, bureaucratic models of state organization with some new network structures that are currently on the rise. So my mind has been primed for anything that seems thematically relevant to those topics.

This particular thread begins with a random encounter on Twitter: checking out my @ mentions a few weeks ago (vanity will get you everywhere), I stumbled across someone mentioning my book to a friend, and also recommending something called "Seeing Like A State." (I can't track down this tweet, so can't give proper credit here.) I wasn't fully sure what "Seeing Like A State" was, but it sounded up my alley, so a quick Amazon search revealed that it was, in fact, a very promising-sounding book written by James C. Scott, about the methods of state organization and control in modern history, and so within a matter of minutes, I was reading it on the Kindle iPad app. (I'm sure it is mentioned in many books that I've read already, but somehow I had missed it over the years.)

The book turned out to have a small discussion of the design of the French railway system in the early 19th-century, which reminded me of a map my old mentor Franco Moretti had showed me two decades ago in grad school, contrasting the heavily centralized French system with the more chaotic British rail lines. So that sent me into a quick exploration of French engineering history that culminated in downloading two PDFs of academic essays on the topic, each of which provided some key historical texture that was missing in Scott's book.

In the meantime, I was continuing to devour Seeing Like A State. Feeling a little guilty about missing a book that should have come across my radar before (it had been published in 1998), I googled around to see what responses the book had generated. As it happened, one of the top-ranking results was a blog post by the political theorist Henry Farrell, with whom I have been discussing the ideas in my new book for many years now. His post was part of a larger debate about the Scott book with the economist Brad DeLong, who had penned a detailed review on his blog. One of DeLong's main criticisms is the way in which Scott ignores the insights of Hayek, which sent me back to an essay of Hayek's that I'd been meaning to read for my book, but hadn't yet got around to. The Hayek essay opened up a whole approach to what I was writing about that I suspect will generate at least a dozen pages of material in the final book.

As I was reading the Scott book, I was storing my highlights from it in the new service, findings.com, which we launched a month or so ago. Findings lets you organize important quotations from eBooks or the Web, but it also allows you to follow other users' quotations. (My introductory post about it is here.) One of the fascinating things it lets you do is see what quotations other readers found interesting in the books you've read. And so when I was reviewing my quotes from the Scott book, I discovered a few other Findings users were also reading it, and one them had picked out a quote that I had somehow missed, a quote that perfectly described the logic of state organization. That turned out to be the quote from the Scott book that I ended up using in my own chapter.

Sometime in the middle of this, I gave a talk at Google, and the speaker before me was the Internet legend Vint Cerf. Listening to Cerf talk about the origins of the Internet -- and thinking about the book project -- made me wonder who had actually come up with the original idea for a decentralized network. So that day, I tweeted out that question, and instantly got several replies. One of those Twitter replies pointed to a Wired interview from a decade ago with Paul Baran, the RAND researcher who was partially responsible for the decentralized design. When I clicked through the link, I discovered that the interview had been conducted by my friend and new neighbor, Stewart Brand, with whom I was having lunch that week. So when I saw Stewart I got to ask him about Baran, and try out this little hunch I was working on about the contrast between the French rail system and the design of the Internet. Meanwhile, one of the other Twitter replies had pointed me to Katie Hafner and Matthew Lyon's Where Wizards Stay Up Late, released more than a decade ago but also available on Kindle, where I found a detailed history of the Internet's early days. And reprinted in that book was an early sketch by Baran of the network model that beautifully contrasted the centralized model of the French rail system, and the map that I had seen so many years ago as a grad student.

And so after all that meandering, my vague introduction had turned into two distinct stories, with two perfectly contrasting diagrams to anchor them visually.

What's the moral of this story? I think there are a few:

1. The discovery process is remarkably social, and the social interactions come in amazingly diverse forms. Sometimes it's overhearing a conversation on Twitter between two complete strangers; sometimes it's the virtual book club of something like Findings; sometimes it's going out to lunch with a friend and bouncing new ideas off them. It's the social life of information, in John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid's wonderful phrase -- we just have so many more ways of being social now.

2. I find it interesting that there are certain kinds of questions that I now send out by default to Twitter, not Google. The more subtle and complex the question, the more likely it'll go to Twitter. But if it's simply trying to find a citation or source, I'll use Google. So trying to figure out who wrote Seeing Like A State was a Google query, but wondering about the origins of the Internet made more sense on Twitter. (I should add that the responses I'm looking for on Twitter are links to longer discussions, not 140 character micro-essays.)

3. Priming is everything. All these new tools are incredible for making rapid-fire discoveries and associations, but you need a broad background of knowledge to prime you for those discoveries. I'm not sure I would have jumped down that wonderful rabbit hole of the French railway design if I hadn't seen that map in grad school two decades ago. Same goes for the Hayek and the internet history as well. I had enough pre-existing knowledge to know that they belonged in the story, so when something about them got in my sights, I was ready to pounce on it.

4. Very few of the key links came from the traditional approach of reading a work and then following the citations included in the endnotes. The reading was still critical, of course, but the connective branches turned out to lie in the social layer of commentary outside of the work.

5. It's been said it a thousand times before, by me and many others, but it's worth repeating again: people who think the Web is killing off serendipity are not using it correctly.

6. Finally, this simple, but amazing fact: almost none of this--Twitter, blogs, PDFs, eBooks, Google, Findings--would have been intelligible to a writer fifteen years ago.

November 16, 2011

Babble Joins Disney

The coverage of the deal thus far has focused on two primary angles: either Disney acquiring a "hipster" parenting site, or the vindication of the blogger-network content model. (Babble runs a large network of "mommybloggers," as they have come to be called.) But I think there's a simpler lesson here that's being overlooked. Babble was a cultural and commercial success because it took on a topic that was exhaustively covered by existing media, and wrote about it in a fresh, nuanced, and more complex way. It had a genuinely new voice that was far more in touch with the actual experience of parenting, and it featured talented writers who wrote about their lives with a sophistication that was simply nonexistent in traditional parenting sites or magazines. (They even asked me to write a piece about parenting that pulled in Jane Jacobs and complexity theory -- an invite that let's just say I would be quite surprised to receive from Parenting.com.) As Rufus and Alisa wrote in their initial mission statement:

We created Babble for one very simple reason: we can't find a magazine or community that speaks to us as new parents. Every publication we encounter presents procreation as a cute and cuddly experience, all pink and powder blue, at best an interior decorating opportunity, at worst a housekeeping challenge. None of it is true to the experience we are having, and that we see around us.

So to me, the success of Babble should be a corrective for all those folks who think that the Web has lowered our journalistic standards, or that original, provocative writing online doesn't have a business model to support it. Yes, Babble was not a commercial success on the level of Facebook or LinkedIn or Zynga. Content sites don't have that kind of scalability. (Though they may well have an easier path to profitability.) But Babble did make a tidy return for their investors, led by Village Venture's Bo Peabody, who has long argued for the value of advertising-supported content sites. The commercial viability of the web shouldn't just be about a handful of billion-dollar IPOs. It should be about a thousand smaller-scale successes, where new voices can both find an audience and create sustainable business models. Babble managed to do both those things in just a few short years -- and that's great news for all of us.

October 28, 2011

Thoughts on Steve Jobs, The Book

The first is that we are very lucky that Jobs reached out to Isaacson (and that Isaacson agreed to do it.) I can't think of a better biographer for this project--so much so that one of the strange thoughts I had after Jobs died was, "At least we're going to have this book to read." It's a very subtle book, admirable in its restraint, I think. There is not a lot of editorializing or broader cultural analysis, just an incredibly careful and nuanced narrative of Jobs' life. Which, I think, is what most of us want to read right now.

The second thing that occurred to me is that, while Jobs historically had a reputation for being a nightmare to work with, in fact one of the defining patterns of his career was his capacity for deep and generative partnerships with one or two other (often very different) people. That, of course, is the story of Jobs and Woz in the early days of Apple, but it's also the story of his collaboration with Lasseter at Pixar, and Jony Ive at Apple in the second act. (One interesting tidbit from the book is that Jobs would have lunch with Ive almost every day he was on the Apple campus.) In my experience, egomaniacal people who are nonetheless genuinely talented have a hard time establishing those kinds of collaborations, in part because it involves acknowledging that someone else has skills that you don't possess. But for all his obnoxiousness with his colleagues (and the book has endless anecdotes documenting those traits), Jobs had a rich collaborative streak as well. He was enough of an egomaniac to think of himself as another John Lennon, but he was always looking for McCartneys to go along for the ride with him.

The most bizarre revelation for me in the book was how much the young Jobs apparently used to cry in meetings at Apple. I literally can't imagine what that would have looked like, from my admittedly very distant knowledge of Jobs. As my friend Tom Coates remarked on Twitter, there are so many different kinds of crying; it would have been interesting to have a bit more color on exactly what kind of tears were shed.

Also: the guy took a lot of walks. The whole idea of inviting someone to go for a walk with you is really lovely. (And for what it's worth, seems very Bay Area to me.) I intend to emulate Jobs in this respect and take more walks with my friends. Just not with Larry Ellison.

The final thought I had is a meta observation about the news environment that Jobs helped create. After devouring the first two-thirds of the book, I found myself skimming a bit more through the post-iPod years, largely because I knew so many of the stories. (Though Isaacson has extensive new material about the health issues, all of which is riveting and tragic.) At first, I thought that the more recent material was less compelling for just that reason: because it was recent, and thus more fresh in my memory. But it's not that I once knew all the details about the battle with Sculley or the founding of NeXT and forgot them; it's that those details were never really part of the public record, because there just weren't that many outlets covering the technology world then.

This reminded me of a speech I gave a few years ago at SXSW, that began with the somewhat embarrassing story of me waiting outside the College Hill bookstore in 1987, hoping to catch the monthly arrival of MacWorld Magazine, which was just about the only conduit for information about Apple back then. In that talk, I went on to say:

If 19-year-old Steven could fast-forward to the present day, he would no doubt be amazed by all the Apple technology – the iPhones and MacBook Airs – but I think he would be just as amazed by the sheer volume and diversity of the information about Apple available now. In the old days, it might have taken months for details from a John Sculley keynote to make to the College Hill Bookstore; now the lag is seconds, with dozens of people liveblogging every passing phrase from a Jobs speech. There are 8,000-word dissections of each new release of OS X at Ars Technica, written with attention to detail and technical sophistication that far exceeds anything a traditional newspaper would ever attempt. Writers like John Gruber or Don Norman regularly post intricate critiques of user interface issues. (I probably read twenty mini-essays about Safari's new tab design.) The traditional newspapers have improved their coverage as well: think of David Pogue's reviews, or Walt Mossberg's Personal Technology site. And that's not even mentioning the rumor blogs.

So in a funny way, the few moments at the end of Steve Jobs where my attention flagged turned out to be a reminder of one of the great gifts that the networked personal computer has bestowed upon us: not just more raw information, but more substantive commentary and analysis, in real-time. It's not just gadget blogs and rumor sites. Take an important issue like IOS vs Android (and the larger closed versus open debate): the amount of complex, thoughtful, provocative material that's been written about that -- from literally hundreds if not thousands of different authors -- over the past few years is just extraordinary, when you think about it. I remember the blank stares I got trying to convince The New Republic and The New Yorker to let me write about the cultural clash between Apple and Microsoft sometime around 1993. Nowadays, if anything we have too much of that mode of commentary. The Web made that depth and diversity possible, of course, but we wouldn't have had the Web without personal computers first. All of which may have made Walter Isaacson's job slightly harder as a biographer, but it has made the rest of our lives so much more interesting.

October 25, 2011

Introducing Findings

I have been dreaming about new tools that would help me capture what I was reading for almost as long I have been reading. During my college years, I lost a semester trying to build an epic Hypercard stack called "Curriculum" that would help me organize all my notes for the courses that I had stopped attending because I was too busy building the software. (Oh, the irony...) In my twenties I began keeping digital copies of influential quotations from books I had read so that they were searchable on my hard drive; during the next decade I stumbled across a brilliant application called Devonthink that enabled me to make interesting connections between those quotes. (I wrote a little lovesong to Devonthink for the New York Times Book Review in 2004.) While I was writing Where Good Ideas Come From, I found myself exploring the long and rich history of the commonplace book, one of the great intellectual engines of the Enlightenment: books of quotations assembled by hand by 18th-century readers, annotating and indexed and remixed by readers like Locke, Jefferson, and Priestley.

A few years ago, I had the good fortune of being re-introduced to John Borthwick, whom I had known slightly in the original dot-com years. We got to talking over lunch about our shared obsession with research and annotation tools. This was somewhere post-Friendster but pre-Twitter, so the idea of making these systems more social was very much in the air. A blog post I had written about Devonthink in 2004 had included this little riff:

The other thing that would be fascinating would be to open up these personal libraries to the external world. That would be a lovely combination of old-fashioned book-based wisdom, advanced semantic search technology, and the personality-driven filters that we've come to enjoy in the blogosphere. I can imagine someone sitting down to write an article about complexity theory and the web, and saying, "I bet Johnson's got some good material on this in his 'library.'"

John and I continued to nibble at the edges of that idea for next few years, until late 2010, when we began to talk about building something in earnest, under the wonderful umbrella of Betaworks, which had already incubated and launched a string of great services and apps: bit.ly, News.me, Tweetdeck, among many others. Early on we had the great fortune to bring in our co-founder Corey Menscher as head of product (well, let's be honest, head of just about everything.) Today, I'm thrilled to announce that our collaboration has led to the launch of Findings.

The service is simple enough -- and draws upon a few social conventions that will be instantly recognizable. (So feel free to just go try it out and skip the rest.) At its core, Findings is a service that allows you to capture, store, search, and share small snippets of text from eBooks and web pages. It integrates Kindle highlights and web clippings (with more input options to come.) And it gives you the ability to share those quotes with your peers, as well as follow other people's quotes through your timeline.

There are plenty of other services and apps out there that clip and store text. (When John and I first met for lunch, he was using a modified WordPress setup to store his personal quotes.) But with Findings, we are trying to do something that is dedicated explicitly to the task of curating quotations. In other words, it's not designed to be a broader publishing platform, or a more generic notebook app that happens to include quotes every now and then. It's a social commonplace book.

That narrowness of focus has allowed us to concentrate on a couple of key features that make Findings particularly useful. First, because we are focused on quotations, we have built a number of smart systems that pull metadata from the sources, which allows you to seamlessly organize your quotes around authors and titles and sources (and other organizational schemes we are going to dream up in the months ahead.) And the social component means you can do the kind of "searching someone else's library" that I was dreaming of seven years ago. The combination of sharing and metadata means that we can start pinpointing the exact pages and passages that people are fixating on right now.

In the next few months, we plan on expanding the ways in which you can organize and navigate through your findings. (We are also expanding the team, so if you're interesting in helping in a more direct way, give us a shout.) We want to make Findings the best service out there for people who have very rigorous organizational needs, and at the same time make it an engine of serendipitous discovery as well. But reaching those lofty goals will require feedback from you: how are you using Findings? What do you want it to do better? So go check it out and and let us know what you think.

October 24, 2011

Ray Ozzie on Lotus Notes and Slow Hunch Innovation

[More in the series of excerpts from the conversations in my new collection, The Innovator's Cookbook. This is part of my exchange with the brilliant Ray Ozzie, who recently stepped down as Microsoft's Chief Software Architect. Ray has been thinking about social software for as long as just about anyone, so I had to ask him how those ideas had evolved over time.]

SJ: How did the idea for Lotus Notes come about?

RO: The Lotus Notes is story is one of those situations where I and several other people––the people who ended up being my cofounders—were exposed to a system that we couldn't shake. It became an itch that we needed to scratch. And the thing that we ultimately built, both the ethos and the name itself, came from that thing that we were exposed to. The product we ultimately built was actually a lot different. But the original experience was the common thread between us.

This was in 1974 through 1977, and there was a group of us who were exposed to this Plato system at Urbana-Champaign in Illinois. This was on the early side of computer science; we were still using punch cards in our computer-science classes. But this Plato system was built by this creative eccentric, Don Bitzer, who believed that computers could change education. He didn't know what couldn't be done. He wanted to build graphics terminals with multimedia, audio. He invented the plasma panel, in order to have a graphics terminal. He built an audio device for it. That left an imprint in and of itself. I love being around people who just don't believe things can't be done, or don't know that they can't be done, and just build whatever the concept requires.

But on the software side, we were all exposed to things that ultimately we'd get used to in the Internet. It was the emergence of online community. And there was probably a community of ten thousand people, five thousand at Urbana, Illinois, and another five thousand around the world. There were online chats, online discussions, interactive gaming, news. It was a full-fledged community. And there was this thing called Notes that did e-mail, personal notes, and discussions, group notes. And after we left, and went into the real world and got our jobs (they went to DEC, I went to Data General), that was the thread that we kept coming back to. We were like: these are interesting computers, but where are the people? And so basically we would get together weekend after weekend, month after month, year after year, and say: "We have to bring the people back into the equation."

SJ: So it ends up taking you six, seven years before you actually start building that thing in your head. It reminds me so much of something in my own life, although I didn't do anything nearly as epic. I was in college from '86 to '90 and HyperCard came out in '87. I've never really been a programmer, but I lost a whole semester trying to build this HyperCard application basically for keeping all my notes and research. (Which eventually fed into my interest in applications like DEVONthink and the commonplace-book tradition.) But the main thing I got out of HyperCard was that it really prepared me for the Web, by working in that hypertextual environment. So I dabbled with HyperCard and then I kind of put that experience away for seven or eight years—but then in '94, when the Web started to break, I was just prepared for it. The first time I saw it, I was like: oh, I know exactly what this is going to be.

RO: That's a reoccurring theme also. You are the sum in many ways of your experiences and you get these success patterns, failure patterns, sometimes those patterns help—like what you just described. But sometimes those patterns hurt, because they constrain your outlook. Something that might not have worked before might work now, because the environment has changed. But the innovators that I know that are successful keep testing those patterns over and over and over because people around them change and the technology environment changes. And so you might look at somebody and say: "You're a one-trick pony. You keep building the same thing over and over." But it's a good thing! That means you're taking those patterns and just recasting them continuously against changes in the environment. And if you believe passionately in a pattern, it's great. Go for it!

October 19, 2011

A Theoretical Education

I have very fond memories of that period of my life, and I tried to explain in the essay all the subtle things I got from that part of my education. But I also wanted to document the bizarre effect it had on my prose style. As it happens, I continue to have almost every single paper I wrote in college still sitting around on my hard drive in MS Word format, and so I was able to go back and retrieve some of those terrifying artifacts for the essay. I ultimately decided on this gem:

The predicament of any tropological analysis of narrative always lies in its own effaced and circuitous recourse to a metaphoric mode of apprehending its object; the rigidity and insistence of its taxonomies and the facility with which it relegates each vagabond utterance to a strict regimen of possible enunciative formations testifies to a constitutive faith that its own interpretive meta-language will approximate or comply with the linguistic form it examines.

Got that? That was me, at 19. I sure hope I didn't talk like that at parties.

When I was reading through the piece in the print paper this Sunday, I had the thought that it would be fun to time-travel back to 1988, and tell the 19-year-old version of myself that the very sentence I was writing will be excerpted in the New York Times Book Review twenty-three years from now. The only catch: the quote will be mocked. By me.

A little while back, my old friend Alex Ross and I were trading war stories about our college prose styles, and we dreamed up a competition that we were calling Worst College Essays 1989, where we'd encourage everyone to submit their own most egregious offenses from their college years, and at the end we'd declare a winner/loser. Alex has posted his own juvenilia over at the New Yorker site. (To be honest, I think his quote still has a certain poetry to it that mine lacks, but you can be the judge.) If anyone else has an equally mortifying quote from their college years that they'd like to get off their chest, the comment threads await you below.