Maria Tatar's Blog, page 23

June 30, 2012

Romance in Disney

From Jezebel

http://jezebel.com/5302581/researchers-d…

In addition to spreading the gospel of Princesshood, Disney is now being accused of elevating heterosexualityto “powerful, magical” heights.

In a paper in the latest issue of Gender & Society, University of Michigan sociologists Karin Martin and Emily Kazyak report that Disney films (emphasis ours):

“…depict a rich and pervasive heterosexual landscape,” despite the assumption that children’s media are free of sexual content. The movies repeatedly mark relationships between opposite sex lead characters as special and magical.

“Characters in love are surrounded by music, flowers, candles, magic, fire, balloons, fancy dresses, dim lights, dancing and elaborate dinners,” the researchers observed. “Fireflies, butterflies, sunsets, wind and the beauty and power of nature often provide the setting for-and a link to the naturalness of-hetero-romantic love.”

And on the plus side:

It’s worth noting that in our opposite marriage, post Prop-8 world, DisneyWorld is one place gay people have made a point of making themselves visible: Gay Days are when thousands of gays and lesbians visit the theme park — a tradition started in 1991. Lately, there have been protests from organizations like the Florida Family Association, which argues that Gay Days (emphasis ours) “offend[s] tens of thousands of unsuspecting guests… regular patrons who expect a normal day at the Magic Kingdom.”

June 27, 2012

Nora Ephron (1941-2012)

“Above all, be the heroine of your life, not the victim.”

Nora Ephron was my hero and one of the great storytellers of our time. In films ranging from Heartburn to Julie & Julia, she showed how what folklorists call the “innocent persecuted heroine” can regain agency and make something of her life. Heartbreak (and heartburn) are part of life, and we live happily ever after when we turn them into opportunities for heroic behavior.

Here’s an excerpt from Nora Ephron’s Commencement speech, delivered at Wellesley College in 1996:

http://www.wellesley.edu/PublicAffairs/C…

So what are you going to do? This is the season when a clutch of successful women — who have it all — give speeches to women like you and say, to be perfectly honest, you can’t have it all. Maybe young women don’t wonder whether they can have it all any longer, but in case of you are wondering, of course you can have it all. What are you going to do? Everything, is my guess. It will be a little messy, but embrace the mess. It will be complicated, but rejoice in the complications. It will not be anything like what you think it will be like, but surprises are good for you. And don’t be frightened: you can always change your mind. I know: I’ve had four careers and three husbands. And this is something else I want to tell you, one of the hundreds of things I didn’t know when I was sitting here so many years ago: you are not going to be you, fixed and immutable you, forever. We have a game we play when we’re waiting for tables in restaurants, where you have to write the five things that describe yourself on a piece of paper. When I was your age, I would have put: ambitious, Wellesley graduate, daughter, Democrat, single. Ten years later not one of those five things turned up on my list. I was: journalist, feminist, New Yorker, divorced, funny. Today not one of those five things turns up in my list: writer, director, mother, sister, happy. Whatever those five things are for you today, they won’t make the list in ten years — not that you still won’t be some of those things, but they won’t be the five most important things about you. Which is one of the most delicious things available to women, and more particularly to women than to men. I think. It’s slightly easier for us to shift, to change our minds, to take another path. Yogi Berra, the former New York Yankee who made a specialty of saying things that were famously maladroit, quoted himself at a recent commencement speech he gave. “When you see a fork in the road,” he said, “take it.” Yes, it’s supposed to be a joke, but as someone said in a movie I made, don’t laugh this is my life, this is the life many women lead: two paths diverge in a wood, and we get to take them both. It’s another of the nicest things about being women; we can do that. Did I say it was hard? Yes, but let me say it again so that none of you can ever say the words, nobody said it was so hard. But it’s also incredibly interesting. You are so lucky to have that life as an option.

June 26, 2012

More on Merida’s Hair

http://movies.nytimes.com/2012/06/22/mov…

Manohla Dargis has a well-done review of Brave, and appears to give Merida’s hair an A+, while the film itself only gets a B.

The riotous mass of bouncy curls that crowns Merida, the free-to-be-me heroine of the new Pixar movie, “Brave,” is a marvel of computer imagineering. A rich orange-red the color of ripe persimmon, Merida’s hair doesn’t so much frame her pale, creamy face as incessantly threaten to engulf it, the thick tendrils and fuzzy whorls radiating outward like a sunburst. There’s so much beauty, so much untamed animation in this hair that it makes Merida look like a hothead, a rebel, the little princess who wouldn’t and didn’t. Then again, Rapunzel has a supernice head of hair too.

Dargis gets at the heart of the problem with the film when she writes about the nature/culture divide in ways that remind me of the big themes taken up in Snow White and the Huntsman.

The association of Merida with the natural world accounts for some of the movie’s most beautifully animated sequences, and in other, smarter or maybe just braver, hands it might have also inspired new thinking about women, men, nature and culture. Here, however, the nature-culture divide is drawn along traditional gender lines. The slim, tidy Elinor serves as the custodian of a dreary feminine realm, which for Merida means hours indoors, being groomed and learning lessons, while the freakishly large Fergus represents a rambunctious, barely domesticated masculine world of huge appetites, tall tales and unruly laughter. Fergus gives Merida a bow and teaches her to shoot in the great outdoors; Elinor primly (and amusingly) tells her daughter, “A lady does not place her weapon on the table.”

June 17, 2012

Brave’s Merida

Mekado Murphy writes about the fashioning of a new fairy-tale heroine. Don’t miss the slide show that accompanies the article: I’m fascinated by all the fuss about Merida’s hair.

Mekado Murphy writes about the fashioning of a new fairy-tale heroine. Don’t miss the slide show that accompanies the article: I’m fascinated by all the fuss about Merida’s hair.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/movies…

“Brave,” set in medieval Scotland, is also the closest that Pixar has come to making a fairy tale. This one involves the headstrong princess Merida, above, who is more interested in archery and independence than in marrying and fulfilling royal traditions as dictated by her mother, Queen Elinor. The character and story were first developed by Brenda Chapman, the film’s initial director. She spoke by phone about what interested her in having Pixar’s first female-driven narrative be about a princess.

“Fairy tales have gotten kind of a bad reputation, especially among women,” she said. “So what I was trying to do was just turn everything on its head. Merida is not upset about being a princess or being a girl. She knows what her role is. She just wants to do it her way, and not her mother’s way.”

Ms. Chapman had ideas about how the character should look. “I wanted a real girl,” she said, “not one that very few could live up to with tiny, skinny arms, waist and legs. I wanted an athletic girl. I wanted a wildness about her, so that’s where the hair came in, to underscore that free spirit. But mainly I wanted to give girls something to look at and not feel inadequate.”

June 16, 2012

My Work Has Always Been Inappropriate

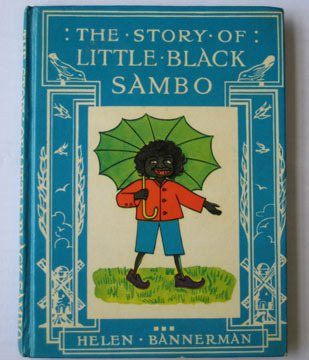

Little Black Sambo, Babar, Pippi Longstocking, and the Oompa Loompas

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/magazi…

How should adults respond to racial stereotyping when they are reading a book to a child? Stephen Marche describes a moment of crisis in bedtime reading and sets forth three options:

“Dad, why do the pirates have a gorilla?” This unexpected question intruded on a recent intergenerational cultural exchange: I was introducing my 6-year-old son to Asterix the Gaul. The pirates in the “Asterix” comics don’t travel with a gorilla, of course. One of the pirate crew is a grotesque caricature of an African who does indeed more closely resemble a gorilla than a person. Freze-frame on this parenting situation. What am I supposed to do? I figure I have three options.

1) Explain that the gorilla is supposed to be a black person.

2) Try to explain the history of French colonialism, how the economics of exploitation in sub-Saharan Africa led to an ideology of racism, which survived in a ghostly transfer even after the conclusion of the French Empire, infecting even silly comics about ancient Gaul.

3) Say, “I don’t know why the pirates have a gorilla” and flip to the next page.

Marshe tells us that he chose the last option, perhaps because 1) it was late at night, 2) he was tired, 3) his son was clearly interested in what happens next. Reading with a child, as I argue in Enchanted Hunters, provides us with opportunities to do more than utter the words on the printed page. Having a conversation about that gorilla doesn’t have to be as stilted as option #2 suggests, nor does it have to be a conversation stopper, as option #1 is. Trust the child, not the tale, and reading together can become all the more interesting. It can even be an educational experience for the adult, in large part because, when we read a book to a child, we engage in bifocal reading, looking at the work through the lens of adult consciousness but also through the defamiliarizing optic of a child reader.

You can read more about Little Black Sambo and its afterlife on Wikipedia.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Story_o…

June 8, 2012

Snow White and the Huntsman

Here’s a link to my blog post about the film.

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/bo…

And here’s some additional commentary on the Grimms’ version from my Annotated Brothers Grimm:

More than Beauty in “Beauty and the Beast,” Snow White has become the quintessentially fair–both beautiful and just–heroine of fairy tales. The innocent, persecuted heroine par excellence, she succeeds in living happily ever after despite the plots designed by her wicked stepmother. Named after only one of the three colors that characterize her beauty (“skin white as snow, lips red as blood, hair black as ebony”), she is often connected with the purity and innocence that our culture associates with the color white. But the term “snow” adds another dimension to her characterization, deepening the meaning of her innocence. Snow suggests cold and remoteness, along with the notion of the lifeless and inert, yet it also comes down from the heavens. And Snow White in the coffin does indeed become, not only pure and innocent, but also passive, comatose, and of ethereal beauty.

Bruno Bettelheim, in exploring some of the alternate versions of “Snow White” recorded by the Brothers Grimm, came to the conclusion that the story turns on “the oedipal desires of a father and daughter, and how these arouse the mother’s jealousy which makes her wish to get rid of the daughter.” The oedipal entanglements, he argues, come to be disguised in the version chosen by the Grimms, which turns the biological mother into a stepmother and relegates the father to the judgmental voice in the mirror.

The many versions of “Snow White” heard by the Grimms suggest the richness of folkloric variation and remind us how we have allowed stories that once circulated freely to ossify into definitive versions. The Grimms describe one version of “Snow White” in which a count and countess drive by three mounds of snow, and the count wishes for a girl as white as the snow. After passing three ditches filled with red blood, he wishes for a girl with cheeks as red as the blood. Finally, three ravens fly overhead and he wishes for a girl with hair as black as the ravens. The couple discovers on the road a girl exactly like the one the count longs for, and they invite her into their carriage. The count immediately has tender feelings for the girl. The countess, however, cannot abide the girl and schemes to get rid of her. She drops her glove and orders Snow White to retrieve it, and then orders the coachman to drive off as speedily as possible. In a related version, the countess tells Snow White to gather roses, and then deserts the girl, leaving her to fend for herself in the woods.

Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) has so overshadowed other versions of the story that it is easy to forget that the tale is widely disseminated across a variety of cultures. The heroine may ingest a poisoned apple in her cinematic incarnation, but in Italy she is just as likely to fall victim to a toxic comb, a contaminated cake, or a suffocating braid. Disney’s queen, who demands Snow White’s heart from the huntsman who takes her into the woods, seems restrained by comparison with the Grimms’ evil queen, who orders the huntsman to return with the girl’s lungs and liver, both of which she plans to eat after boiling them in salt water. In Spain, the queen is even more bloodthirsty, asking for a bottle of blood stoppered with the girl’s toe. In Italy, she instructs the huntsman to return with the girl’s intestines and her blood-soaked shirt. The dwarfs are sometimes miners, but sometimes also compassionate robbers, thieves, bears, wild men, or ogres. Disney’s film has made much of Snow White’s coffin being made of glass, but in other versions of the tale that coffin is made of gold, silver, or lead, or is jewel-encrusted. While it is often displayed on a mountaintop, it can also be set adrift on a river, placed under a tree, hung from the rafters of a room, or locked in a room and surrounded with candles.

“Snow White” may vary tremendously from culture to culture in its details, but it has an easily identifiable, stable core in the conflict between mother and daughter. In many versions of the tale, the evil queen is the girl’s biological mother, not a stepmother. (The Grimms, in an effort to preserve the sanctity of motherhood, were forever turning biological mothers into stepmothers.) The struggle between Snow White and the wicked queen so dominates the psychological landscape of this fairy tale that Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, in a landmark book of feminist literary criticism, proposed renaming the story “Snow White and Her Wicked Stepmother.” In The Madwoman in the Attic, they describe how the Grimms’ story stages a contest between the “angel-woman” and the “monster-woman” of Western culture. For them the motor of the “Snow White” plot is in the relationship between two women, “the one fair, young, pale, the other just as fair, but older, fiercer; the one a daughter, the other a mother; the one sweet, ignorant, passive, the other both artful and active; the one a sort of angel, the other an undeniable witch.”

Gilbert and Gubar, rather than reading the story as an oedipal plot in which mother and daughter become sexual rivals for approval from the father (incarnated as the voice in the mirror), suggest that the tale mirrors our cultural division of femininity into two components, one that is writ large in our most popular version of the tale. In Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, we find these two components fiercely polarized in a murderously jealous and forbiddingly cold woman on the one hand and an innocently sweet girl accomplished in the art of good housekeeping on the other. Yet the Disney film also positions the evil queen as the figure of gripping narrative energy and makes Snow White so dull that she requires a supporting cast of seven to enliven her scenes. Ultimately it is the stepmother’s disruptive, disturbing, and divisive presence that invests the film with a degree of fascination that has facilitated its widespread circulation and allowed it to take such powerful hold in our own culture.

Children reading this story are unlikely to make the interpretive moves described above. For them, this will be the story of a mother-daughter conflict, which, according to Bruno Bettelheim, offers cathartic pleasures in its lurid punishment of the jealous queen. Once again, as in “Cinderella,” the good mother is dead, and in this story the only real assistance she offers is in her legacy of beauty. Snow White must contend with a villain doubly incarnated as beautiful, proud, and evil queen and as ugly, sinister, and wicked witch. Small wonder that she is reduced to a role of pure passivity, a “dumb bunny” as the poet Anne Sexton put it. In its validation of murderous hatred as a “natural” affect in the relationship between daughter and (step)mother and its promotion of youth, beauty, and hard work, “Snow White” is not without problematic dimensions, yet it has remained one of our most powerful cultural stories. In 1997, Michael Cohn drew out the dark, Gothic elements of the story in his Grimm Brothers’ Snow White, starring Sigourney Weaver.

May 13, 2012

Cake Every Morning

nbsp;http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2012/05…

Read Steven Heller on Sendak (“Kids need Kongs”) and be sure to look at the names of the artists below each image in the slideshow. And here’s Tomi Ungerer’s winning post:

I visited Maurice last summer. It was joy and bliss under the pine trees. Cajoling the past and blasting the present — both roaring, eyes weepy, giving our emotions a free range of expressions. Maurice is now where the wild things are. Ursula Nordstrom, our editor, Edward Gorey, Shel Silverstein and many others are already there, now celebrating his arrival with a big-bang-binge among the restless natives. Feasting on taboos and dancing the mumbo-jumbo under the No No trees. His departure is an invitation! See you later perkolator!

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/13/opinio…

Mother’s Day Stories: Compare and Contrast

http://www.google.com/ (only works today, May 13!)

And here are the 2 stories from the NYT:

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/13/fashio…

May 8, 2012

We Are All in the Dumps

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/09/boo...

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/09/boo...

He was larger than life and twice as natural.

Over a decade ago, Maurice Sendak came to Harvard to see the Emily Dickinson Room at Houghton Library, Keats’s manuscripts, and to give a lecture to the students in my course on childhood. He referred to himself then as a “dinosaur” and worried about the decline in the quality of children’s books, though he conceded that he might also just be a “grumpy old man.” Over lunch, he was anything but, and, despite his stated aversion to signing books, he generously illustrated and signed title pages of all the books that the students had brought to class. I always referred to his visit as a golden afternoon.

What he loved, others will love, and he showed us how. When I think of Sendak, my first associations are to Mozart, Kleist, Melville, and Runge, the creative geniuses he loved and from whom he learned his art. Who else could illustrate Penthesilea or Pierre? In his talk at Harvard, he explained that his success as an author enabled him to work on projects that he did for love and that always lost money.

I love the photograph used by the NYT because there is Herman, one of the many dogs Sendak cared for, along with books and a reading chair. Sendak was introspective by nature, but, there he is, gazing out the window at the beauties of nature. I am sure that Mozart’s music is playing in the background. The photograph is a preview of his heaven.

Margalit Fox writes, in the NYT obituary: He was also a mentor to a generation of younger writers and illustrators for children, several of whom, including Arthur Yorinks, Richard Egielski and Paul O. Zelinsky, went on to prominent careers of their own.

And Brian Selznik also belongs on that list. His breakthrough came when Sendak told him: “Make the book you want to make.” What followed was an apprenticeship with Sendak (without Sendak being aware of it) and The Invention of Hugo Cabret.

Maria Tatar's Blog

- Maria Tatar's profile

- 316 followers