Philip Caputo's Blog, page 12

March 27, 2017

UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAY 4 (Feb.26)

The first day aboard the Jahan begins with an early-morning Tai Chi session on the Terrace Deck. It’s led by a young Cambodian woman who executes the forms with a ballet dancer’s grace. The eight or ten passengers who try to follow her, including me, look as if they might be a tad drunk, or suffering from joint ailments. But it’s quite pleasant on deck in the open air. The Southeast Asian sun is about two hours away from delivering its stunning blows.

Despite the early hour, the Mekong is alive with activity. Every kind of vessel is plying upriver and down: small dugouts paddled by one or two people; larger sampans powered by marine engines attached to the upper end of very long shafts (to allow the pilot to raise the prop when passing over shoals); fishing boats with big eyes painted on the bows to ward off evil spirits; barges 100-feet long, sunk to the gunwales by their huge loads of Mekong River silt (which is exported to places like Singapore for landfill). Both banks are lined with villages, one after another, clay-tile and sheet-metal roofs showing through bamboo groves, tall teak trees, and mango orchards, the fruits covered by white sacks to protect them from birds and insects. Fish farms crowd the shores. Each one consists of a house boat floating on fifty-gallon drums above pens 30 feet deep holding thousands of red tilapia and catfish. Some are raised for local consumption, most for export. When they’re big enough (it takes 10 months to raise a fish from a fingerling to two pounds), the fish are netted, dumped into boats, and sailed to one of the packing houses that appear here and there — big, steel-sided structures that lend a jarring industrial accent to the rural landscape.

The ship dropped anchor, longboats picked us up and took us on a cruise through a floating market, where merchants advertise by flying their wares — everything from produce to T-shirts — from poles fastened to their cabin roofs. Then it was on to a home factory in the town of Cai Be for demonstrations in making rice paper, pop rice, and coconut candy. I’ll confine myself to the rice paper process. A middle-age woman showed us how it is done. She took a lump of rice flour and water, spread it to the thinness of a crepe on a circular, metal plate heated over a smoldering clay oven, then covered the mixture with a raised lid. After steaming for about half a minute, she lifted the lid, and slipped a long, flat blade under the wet rice paper, partially rolled up one end, then held the other end between two fingers, and deftly unrolled it and spread it on a table dry. The finished product looked like an oversize, white, extremely thin pancake. We were invited to give it a try. I was one of the two volunteers. Clearly, manufacturing rice paper was not my strong point; my product resembled a crumpled napkin.

Another longboat voyage brought us to an island village, Binh Thanh, where the production of reed mats is the specialty. It is tedious work requiring a good deal of skill and still more patience. Like the making of rice paper, it is woman’s work. (I’m not sure what the men in town did; I saw one sound asleep in a hammock). One woman sits alongside a kind of loom laid on the floor, loops a string around a hollow reed, and feeds it into the loom, operated by the second woman, usually the more experienced. With a quick, practiced movement, she flicks the shuttle and weaves the reed and string into the mat. This takes a few seconds. A veteran team, like the pair of 40-somethings we watched, can turn out a large mat in 45 minutes. Two younger apprentices nearby were considerably slower, possibly because they were distracted. One, announcing that she was 30 years old her partner 28, and that they were both divorced, asked our guide if there were any single men among us, adding a flirty

The Jahan underway.

look to the question. Although she was good-looking (you have to search a long time to find a young Vietnamese woman who isn’t), she must have been desperate: every male head in our group was either bald or gray).

A final note: Today, I had to sing for my passage by giving the first of my lengthy presentations. I was a bit nervous. Did 45 tourists on an exotic and very expensive holiday want to listen to a rather grim account of the fall of Saigon? To my relief, my war story came off fairly well, and I rewarded myself with a Bombay martini that evening. The second address is scheduled for tomorrow, shortly before we’re due to cross into Cambodia.

Me, attempting to make rice paper. I flunked.

An “Eye” fishing boat on the Mekong

Weaving a reed mat. Jahan guest Cathy Nachman learning the craft.

The post UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAY 4 (Feb.26) appeared first on Philip Caputo.

March 26, 2017

UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAY 3 (FEB. 25)

“Many Vietnamese want to emigrate to the U.S.,” said the 30-something man named Thinh. He added, half-jokingly–that is, half-seriously: “If you adopt me I could emigrate to America without a visa.”

His comment was one indication that my initial impression of today’s Vietnam as a country marching toward a promising future was somewhat Pollyanna-ish. A deeper, grimmer look beneath the surface was presented at a lecture this morning by an American banker and expat who has lived in Saigon for years. Politically, he said, Vietnam is riddled with corruption in the private and public sectors of the economy, dominated by state-owned monopolies in steel, coal, airlines, telecommunications, and banking. The government has invested far too much in “white-elephant projects,” like steel plants that produce inferior steel, and is overly dependent on foreign firms to maintain a respectable rate of growth. These companies, mostly from South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, account for 72 percent of Vietnam’s exports. The economy was doing well after a “renovation policy” replaced a draconian experiment in Mao-style Marxism, but truckloads of money went into stock-market speculation and dubious real estate ventures (sound familiar?).The 2008 financial crisis slammed on the brakes. More than 100,000 small, private enterprises went belly up, private banks lacked the liquidity to lend, while the aforementioned government companies were able to borrow from state-owned banks, encouraging further investment in white elephants. The result has been widespread income inequality. About two-thirds of Vietnam’s 92 million people live in the countryside, where farmers earn, on average, $20 a month. Industrial workers take home around $150, and office employees of foreign firms (who account for a mere 7 percent of the workforce) earn anywhere from $500 to $1,000 monthly.

And that’s not all, our speaker went on. Abroad, there are rising tensions with China over disputed claims to islands in the South China Sea. On the domestic front, towns and cities are choking on polluted air; the damming of the Mekong River has deprived half a million homes in the Mekong Delta of fresh water, freedom of the press is nonexistent (when unfavorable news appears on TV, the screen goes suddenly blank, flashing a message that the station is experiencing technical difficulties). Firewalls blockade the Internet, and private property is unknown (the government owns all the land, which it then leases to private citizens). “There’s a new boom in real estate,” he said. “And a new bust is coming.”

As if to sprinkle a little color into this somber picture, he added that Vietnam is doing better than Laos or Cambodia but not as well as Thailand.

After that glimpse into the dark side, some of us felt in need of an anti-depressant.

My own mood was buoyed by the 2-hour bus ride to My Tho, a Mekong Delta town where we would board our ship, the Jahan. I had made this drive by jeep in 1975. The road at that time was a narrow blacktop passing through war-ravaged villages. Now it was a four-lane superhighway, with concrete bridges soaring over canals and river tributaries. Traffic was rush-hour dense, a river in itself composed of the ubiquitous motor bikes and scooters. I couldn’t help but compare what I saw now to what I’d seen more than forty years before, and to respond to the progress like a Vietnamese: Hey, this is okay If so many people could afford all those Hondas and Kawasakis, and ride them over a four-lane divided highway, then maybe things weren’t as bleak as our morning speaker had painted them.

We made a brief rest stop at the Vinh Trang pagoda, an elaborate Buddhist temple, its gold-leafed pillars and roof shining in the sun. A giant concrete statue of the Happy Buddha, smiling and pot-bellied, overlooked the shrine. Mr. Tam, our guide for the day, told us that there is freedom of religion in Vietnam, with one caveat: if your national ID card identifies you as practicing a particular faith, you can’t land a government job. Apparently, only atheists, agnostics, and the non-denominational need apply.

Tam also told us a story illustrating that the sorrows and tragedy of war are best written not in epic poetry but in the haikus of single lives lost. Tam, now deep into middle age, was born near Hanoi, one of ten children. When he was 18 months old, and North Vietnam under relentless U.S. bombing, his family spent hours of each day and night, sometimes entire days and nights, huddled in their air-raid shelter. It wasn’t much more than a deep hole in the ground covered by dirt and logs. In the stale air of that crowded space, one of his brothers developed bronchitis. It grew worse as the days wore on, but his parents were too afraid to take him to a hospital. The boy died. in between B-52 raids, his mother and aunt rushed out to a field and hastily buried him. Later, after the U.S. had ceased the bombing campaign, the family searched for the body to give it a proper burial, but Tam’s mother and aunt could not remember where they had dug the grave. In Vietnamese culture, it is very important to know where your ancestors and family members are interred so the correct rituals can be performed, lest their spirits become “wandering souls” and haunt the living. Years later, when the war was over, the boy’s grandmother consulted a medium to make contact with her lost grandson. He appeared to her one night, and assured her he was all right; but in her joy to see and speak to him, she forgot to ask where he’d been buried. To this day, no one in Tam’s family knows the location of his brother’s grave. He remains a wandering soul. Thus ended Tam’s story of one more unsung casualty of war.

It lingered in my mind as we pulled up to a dock on the broad, sand-brown Mekong, where the Jahan was moored. A white-hulled ship built in 2004 along classic lines, with brass fixtures and antique phones in the spacious staterooms, she looked like a vessel out of Joseph Conrad’s day. Tonight, she would begin her voyage upriver into Cambodia, where the 1,000-year-old temples of a vanished civilization rise out of the jungle.

Below: The Vinh Trang Pagoda, My Tho, Vietnam

The Laughing Buddha, Vinh Trang Pagoda. Pagoda on the right.

The post UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAY 3 (FEB. 25) appeared first on Philip Caputo.

UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAYS 9 & 10 (March 3-4)

Friday, the 3d of March. We are off the Tonle Sap and back on the Mekong, which isn’t navigable by large vessels for much farther. That’s why it’s our final day on the Jahan. Buddhist monks come aboard to bless the ship, their chants hypnotic and soothing. She casts off, and while she cruises toward an anchorage in the town of Kampong Cham, we listen to back-to-back lectures by two of the expedition’s staff. The first, given by Martin Cohen, an Australian naturalist, is about the Mekong. As I mentioned in an earlier post, it’s the 12th longest river in the world. Other impressive facts: it’s home to more than 1,200 species of fish, and 60-70 million people live in its basins, where 1,000 new terrestrial species have been discovered recently. A depressing fact: more than 20 dams are on the river, 40 more are in the works, and they will drastically affect fisheries and wildlife. Lecture #2, by David Brotherson, previously mentioned, covers the archeology of Angkor. I am tired and fail to take notes, so I can’t say anything about the subject.

We disembark at Kampong Cham, a well-kept French colonial city. I have been faithful to my mission to mingle with the passengers, but when the expedition leader, Larry Prussin, invites us to walk around town, Leslie and I welcome the chance to be alone and stroll along the river esplanade. The evening brings a farewell cocktail party, a salute to the ship’s mixed Vietnamese and Cambodian crew, and then a dance. It begins with popular Cambodian songs, then shifts to 50s and 60s rock. Leslie and I earn a few compliments for our performance to Chuck Berry’s “Mayballene.” It’s an exceptionally hot, still, muggy night, we’re sweaty, and an estimated one trillion small white moths hatch from the river banks to fog the lights on deck. I swallow a few thousand while we’re dancing.

Saturday. We disembark again and board buses for the 5-hour trip to Siem Reap and the temples of Angkor Wat. For the past week, I’ve been able to pretend that I’m an adventurer and to commune with the spirit of Joseph Conrad; now, off the water and on an air conditioned bus, I feel like what I am — a tourist. The feeling deepens when, after passing through flat rice plains and rubber plantations, we stop at a trinket shop that seduces me into buying a bauble — a carved wood dragon whose hinged mouth opens to an incense burner. In the early afternoon, we are deposited at our Siem Reap hotel, Le Residence d’Angkor, another 5-star establishment that deserves a 6. It’s a world unto itself, with tropical gardens, a 35-meter swimming pool, and gorgeous rooms. What the hell, if you’re going to be a tourist, might as well go all the way.

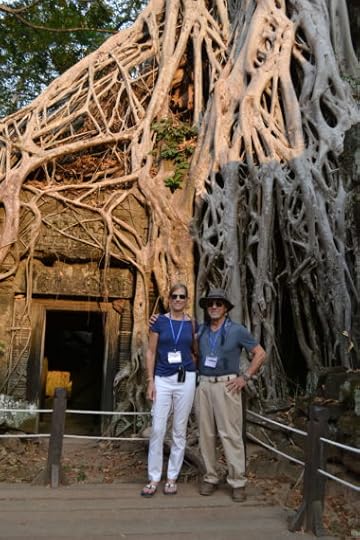

We clamber aboard minibuses in mid-afternoon for a trip to Ta-Prohm, a jungle-choked temple that was a location for the film “Tomb Raiders.” We are in the heart of what had been the Khmer Empire, which flourished from the 8th to the 14th centuries and at its height extended over all of present-day Cambodia, the southern third of Vietnam, and large swaths of Thailand and Laos. Its many kings built temples throughout their domain, scores of them. This one was constructed during the long reign of Jayavarman VII (1181-1220), known in tour-guide shorthand as J-Seven. These temples were more than religious sites; they formed the centers of vast cities. The biggest, at Angkor Wat, is believed to have had a population exceeding a million.

Khmer religious beliefs and culture stemmed directly from India, but were later overtaken by Buddhism. The two faiths in fact intermingled, and that proves a problem for the western visitor. Both are so complex they make Jewish dietary laws read like a Betty Crocker recipe book. Our guide, a lively, knowledgable woman named Pich (pronounced Peach), gives us a short course on Hinduism as we traipse behind her, listening device buds in our ears. The Hindu religion, like Christianity, holds a trinity as supreme: Vishnu, the Protector, Shiva, the Destroyer, and Brahma, the Creator. However, the pantheon includes a host of lesser divinities, along with an assemblage of demons, and enough mythological beings to fill Yankee Stadium. To complicate things further, Vishnu returned to Earth in ten avatars, called the Ten Incarnations. The best known of these in the West is Krishna, who rights wrongs and brings happiness to the world.

Keeping all of this straight is beyond me in the triple-digit heat. I am further distracted by swarms of my own kind, tourists; mostly Chinese and Japanese, but with respectable contingents of young Western backpackers. These throngs spoil the spooky, romantic atmosphere (Really, the world should institute a global tourist-free day once a month; nobody gets to go anywhere), The ruins are fantastic, despite the hordes toting cameras and guidebooks.

Leslie and me, by the roots of a tree overgrowing the ruins at Ta-Prohm.

Sunset on the Mekong.

Because restoration work is in its early stages — it didn’t begin until 2007 — the jungle hasn’t been completely cleared; it clings to the crumbled towers, the roofless pavilions and piles of rubble. Parrots and birds cry from the branches of trees tall as 20-story buildings. The lichen-smeared walls of a hall where apsara dancers performed at religious ceremonies, tossing lotus blossoms as blessings, look mysterious and haunting. In one half-destroyed tower, the roots of a 300-year-old tree coil around the sandstone blocks like giant serpents, and a banyan root drooping over a corner of a wall resembles an elephant trunk. And under a protective roof is a headless statue of Buddha, discovered only two years ago. If you can ignore the crowds — which isn’t easy — you can imagine what it was like for the archeologists who first discovered this temple.

Bas reliefs at Ta-Prohm, stained by red lichen.

The post UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAYS 9 & 10 (March 3-4) appeared first on Philip Caputo.

UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAYS 7 & 8 (March 1-2)

Cambodia’s Spider Man stands five feet three or four (with a good wind under him), weighs around 120 pounds (with a brick in his back pocket), and is 66 years old. His real name is Ree — that’s a phonetic spelling — and he earns his living scaling tall coconut palms to harvest their fruits, from which he makes palm oil, palm sugar, and palm rum. We met him this afternoon, after the Jahan sailed us into a canal off the Tonle Sap river, where we boarded long boats that brought us ashore for a 20-minute drive by minivan to Ree’s village, Kampong Chnnang. Its huts and houses are clustered on flatlands beneath Golden Mountain, which is more a high hill than a mountain, matted with jungle and the source of the soil used for making clay pottery.

Half of Mr. Ree’s teeth are missing, every day of his six-plus decades is etched into his brown face, but he’s as limber as an athletic boy. He’s also something of a showman, delighted to demonstrate his prowess. Wearing shorts, sandals, and a straw hat, he climbed a 60-foot palm tree by means of ladder consisting of a bamboo trunk into which foot and hand holds had been notched. In a couple of minutes, he was up among the leaves, lopping coconuts with a machete; then, in an amazing display of nerve and agility, he crossed into a neighboring tree, cut into a few more coconuts, then scampered back to the ladder and began to climb down, cameras and cellphones trained on him. Halfway down, the performer in him couldn’t resist a bit of showmanship: clinging to the ladder with one hand, his hat in the other, he made a sweeping bow.

Earthbound again, Ree stood behind a counter on which his products were arrayed, and clued us in on the methods and economics of their manufacture. He owns 30 trees, leases another 30, and climbs them twice a day every day, extracting about 5 liters of palm oil from each one. He sells it and palm sugar commercially, along with a sweet, zingy rum.

Next door to his grove, two women were making clay pottery completely by hand. No wheel, no tools of any kind except a kind of wooden spatula. Under the critical eye of her older mentor, a young woman took a lump of clay, punched a hole in it with her hand, and set it on a tree stump. She became the pottery wheel by walking around and around the stump, occasionally smoothing out lumps with the wooden implement. In about ten minutes, without coaching from the older woman, she turned out a handsome little pot that would later be fired in an oven. It was an impressive display of craftsmanship. Our “Tee,” Rithy, told us that this method has been used in Cambodia for 5,000 years, give or take a century or two. The clay, by the way, was mined from the slopes of Golden Mountain, atop which stood a startling anomaly — a cellphone tower.

Back on the river, we boarded longboats for a journey to a floating villages, where we learned that Cambodia has a problem familiar to Americans: immigrants. The aliens in this case are Vietnamese fishermen, who began moving into Cambodia in the late 1980s and now number well into the thousands. Their legal status is somewhat hazy. The government, apparently, tolerates their presence, but prohibits them from owning land. Hence, they’ve settled into houseboats that throng the riverbanks for a long distance. The waterborne village inspired Tee to launch into a political tirade. “This is Vietnamese colonialism,” he declaimed. The Vietnamese were stealing the livelihoods of Cambodian fishermen, were polluting the waterways, were going to take over the country culturally and politically. Tee could find nothing good to say about the Vietnamese. He sounded like a Trump supporter speaking of Mexicans. His harangue, which we listened to through the receiving sets in our pockets, went on for so long that some of us pulled the buds from our ears.

A dark red sun bled into the morning haze as we went through our Tai Chi exercises, displaying slightly more competence than at the beginning. To immerse us further into the timeless rhythms of Cambodian rural life, the excursion directors put all 45 of us on ox-carts for a trip through rice fields and lotus beds. Modern transportation — minivans — brought us to a school where very disciplined, very charming kids learn English. From there, a vehicle known as a Tuk-Tuk — it’s a four or two seat covered carriage pulled by a motorbike — delivered us to a Buddhist monastery, where we, sitting crosslegged on mats, became the pupils for a seminar on Theravada Buddhism. Our professor was the head monk, who sat beneath an indescribably ornamented altar. Theravada is the school of Buddhism practiced in most of Southeast Asia, and is to be distinguished from the other school, Mahayana. I’m afraid I can’t pass on what we learned because I couldn’t follow what the differences were between the two. Anyway, a novice monk, he said, must learn to chant and to practice ten precepts (which resemble the Ten Commandments), but to become an ordained monk, he has to follow an additional 227! As these, in addition to the first ten, include abstention from drinking, smoking, and sex, along with countless other pleasures, I figured monkhood was not in my future. The head monk, incidentally, had not denied himself the enjoyments of the table; he could have dropped 50 pounds without coming near emaciation.

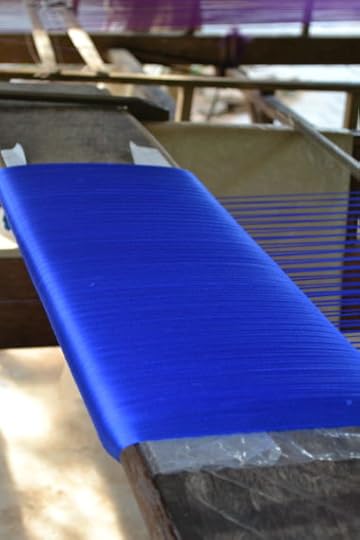

Thus enlightened, we traveled on to a silk weaving village on an island, Koh Oaknha. It employs women down on their luck — widows, divorcees, single mothers. The production of silk fabrics, as it’s done in Cambodia, is an art requiring infinite patience. On Kohn Oaknha, silk worms — grown from moth eggs — are stored in trays kept in a shed and fed mulberry leaves three times a day for a month, until they have developed cocoons roughly the size of a little finger. Boiling these in a bowl produces silk strands so fine they are almost invisible. Twenty or thirty are woven, by hand, into a thread thick enough for weaving, then dyed, spooled, and transferred to weavers, who sit behind looms that would not have looked out of place in medieval Europe. Watching them was as much a study in endurance as in expertise. Their feet pumping the treadles, their hands tugging the shuttles back and forth, they were turning out scarves, table cloths, and raw bolts thread by thread. One woman was working on an exquisite motif in which colored bands separated rows of peacocks. She was, said Rithy, one of only four or five women in the country with the experience, and the talent, to produce such a detailed pattern.

A Silicon Valley wizard looking at her and her co-workers would probably wonder why the whole process wasn’t automated. The textile industry, after all, was mechanized in the West nearly 200 years ago, throwing weavers out of work or transforming them into factory drones. The Luddite in me silently cheered these weavers on.

Silk weaver at her loom.

A bolt of blue silk, almost finished.

Mr. Ree, scrambling up a palm tree.

Leslie and me with ox-cart driver in Cambodia

Lotus blossoms

The post UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAYS 7 & 8 (March 1-2) appeared first on Philip Caputo.

UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAYS 11 & 12 (March 5-6)

On Sunday, after we’ve toured the royal city of Angkor Thom (once the capital of the aforementioned Jayavarman VII), Leslie gets sick. All but five of our group have succumbed at one point or another to the intestinal distress that’s inevitable when traveling in Southeast Asia. She and I are riding back to Siem Reap in a Tuk-Tuk, hoping to reach our hotel room soon, but the poor woman looks peaked, she’s wincing and grimacing, and I ask the driver to stop before we get into the city. Leslie jumps out and flees into the sheltering jungle for relief. I keep my fingers crossed that she doesn’t step on a cobra.

While in Angkor Thom, Pich guided us over a bridge lined on one side with the busts of 54 Hindu gods and on the other with 54 demons. Another lesson in Hinduism’s bewildering complexities. She informed us that the total number of busts — 108 — is significant. One plus zero plus eight equals nine, the number of prosperity. Angkor Thom was more impressive than Ta-Prohm, with beautiful friezes depicting apsara dancers and a battle between the armies of the Khmer Empire and its rival, the Cham kingdom.

The final day: Leslie rallies well enough to rise at 4;30 a.m. to view Angkor Wat at sunrise. The word means “city monastery,” for it was both a temple and a city unto itself. Nothing remains of the latter, the houses having been built of perishable stuff like wood and thatch. The temple, still being restored, was made of sandstone, laterite, and brick. It is stupendous, at more than 500 acres the largest religious site on the planet. Compared with it, the great cathedrals of medieval and Renaissance Europe are little more than country churches. It’s a monument to the ancient Khmers’ architectural and engineering know-how, the virtuosity of their artisans, the skills and endurance of their laborers. It is estimated that 300,000 of the city’s one million people worked to build the temple, dig the moat around its walls, and construct the vast reservoirs ( in use today) that supplied the city with fresh water.

Built over a period of 50 years during the reign of Suryavarman II, Angkor Wat was dedicated to Vishnu. A king who thought big, Suryavarman was: the temple symbolized the entire universe. The moat represents the cosmic ocean, the concentric galleries mountain ranges; the three levels of steep staircases, climbing to the five towers of the central shrine, represent the ascent to Mount Meru, in Hindu as well as Buddhist cosmology the home of the gods, the center of all creation.

We enter the temple from the west, trooping across a long causeway spanning the moat. Our hope that the crowds would be sparse at pre-dawn proves delusional. I’ve seen less people in mid-town Manhattan on a workday. We make our way onto a wide ledge along a wall and wait for the sun to show itself through the thin haze graying the sky. A distance in front of us is the gopura, or entrance: three oblong towers with long, hook-shaped serpent figures lining the sides of their roofs; in silhouette, they resemble fat evergreens. The sun, a dark red disc, comes up, and our new guide, Sarom, tells us that the towers were erected so that sunrise would occur over the center tower at the equinox.

We file past a vast mob of homo-touristensis gathered around a pond, taking pictures of the towers and the new sun reflected in the water. Those in the rear ranks have their cellphones and cameras raised overhead and look as though they’re performing some strange religious rite. The crowds, the heat and humidity get to Leslie, who hasn’t fully recovered from yesterday. Suddenly, she moves off to the side, falls to her knees, then to all fours, and vomits. I go to her with Mark Hauswald, the excursion’s doctor, and David May, a guest who happens to be a retired surgeon. She’s certainly well-attended, but there isn’t a lot we can do for her. Mark gives her a packet of Immodium and some anti-nausea pills; then, David Brotherson and I walk her around the temple to its rear entrance. Given the size of the place, it’s quite a long walk, but blessedly free of people. We hardly see a soul.

Leslie sits down in the shade of a tree, and hands me her camera, telling me that she’ll be all right and to go inside and take some pictures. David leads me up a staircase to a gallery that’s a real jaw-dropper. In one continuous panel more than 50 yards long, a bas relief depicts the Churning of the Sea of Milk, an event from the great Hindu creation myth, the Bhagavata Purana. Gods and demons hold a gigantic serpent, the gods at one end, the demons at the other, Vishnu at the center. The figures are beautifully realized, cut into the sandstone with great care and precision. I would have no idea what the hell I’m looking at if Brotherson wasn’t with me. In the myth, the deities and demons work together at Vishnu’s command, alternately pulling on the serpent, which is coiled around a mountain, causing it to rotate in the cosmic sea. Kind of a titanic food processor. They churn for 1,000 years, producing amrita, the elixir of immortality. Why the cosmic sea was milk instead of water would have to remain a mystery. I snap a few photos.

We move on to the next gallery, where another splendid relief shows souls consigned to heaven and hell, according to the edicts of Yama, the god of judgment. We walk along its length, nearly 70 yards, but then encounter what appears to be several thousand Chinese tourists. In that dim, stifling corridor, I feel that I’m in a Beijing subway at rush hour.

Half an hour later, I’m waiting in a long line to climb the steps to the central shrine, the symbol of Mount Meru. But the line is moving very slowly, I’m worried about Leslie, so I forego the ascent and return to where I left her, under the tree. Most of our group are there, but not Leslie. In a few minutes, she reappears emerging from the Sea of Milk gallery. Maybe she absorbed the essence of the elexir. Several people cheer and applaud her comeback. She pauses at the top of the staircase, and, as if to mimic some priestess bestowing a blessing, spreads her arms wide and bows.

It is now 9 a.m., the excursion is over. Leslie hang around Siem Reap for the day; then, with bags packed, we are driven to the airport for a night flight to Shanghai and connections for the trans-Pacific flight home. Finis.

Sun rise over the entrance to Angkor Wat.

The 3 towers at the entrance to Angkor Wat

Me, nose to nose with a face of Buddha at Angkor Thom

Staircase to the central shrine at Angkor Wat, symbolizing the ascent to Mount Meru, home of the gods.

The post UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAYS 11 & 12 (March 5-6) appeared first on Philip Caputo.

UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAY 6 (FEB.28)

Phnom Penh would present us with mind-bending contrasts, I stated in my last post. At sunrise, after having another go at Tai Chi on the terrace deck, we disembarked, toured the capital in cyclos, then visited the Royal Palace, a spectacular sight. Pagodas and pavilions with swooping, golden roofs; tranquil gardens shaded by mango trees; an ornate, conical stupa containing the ashes of King Norodom Sihanouk; the Silver Pagoda, its floor composed of exactly 5,329 silver tiles. In the center sat the statue of the “Future Buddha,” inlaid with 180 pounds of gold and 2,086 diamonds , one of which forms his third eye and is as big as the Ritz. Our guides, named Rithy and Vuthy, but both called “Tee,” told us that the Buddha symbolizes the virtues expected of a leader: loving-kindness; compassion; sympathetic joy, and equanimity. “We have never had a leader with those qualities,” said one of the Tees. Nor do the Cambodians have one now. The country is a constitutional monarchy, the king (Sihanouk’s son, Norodom Sihamoni) utterly powerless, with nothing to do but sign legislation. The country is governed by what might be called an elected despot; its prime minister, Hun Sen, having held power for more than 30 years, largely through rigged elections.

I suppose the Cambodians are more than willing to put up with Hun Sen’s authoritarianism. Hell, they probably would put up with Genghis Khan. Anything would be better than the Khmer Rouge, who ruled from 1975 to 1979 and wrote one of the darkest, most blood-drenched chapters in modern history, ranking with Armenian genocide of 1915 and the Holocaust. At least two million people, a quarter of Cambodia’s population at the time, died in mass executions or from starvation. Many books have been written about that horrific period. I recommend “Survival in the Killing Fields,” by Haing Nhor, a Cambodian physician who lived through it and portrayed Dith Pran in the movie, “The Killing Fields.”

The Khmer Rouge aim was to radically transform Cambodia into a perfectly classless, perfectly equal, agrarian utopia. What it created instead was a perfectly monstrous, perfectly barbaric reign of terror. Every urban center, including the capital, was emptied of people. Phnom Penh, Siem Reap, and other cities became ghost towns in a matter of days, weeks at most. Their citizens — those lucky enough to escape death, that is — were packed off to the countryside to work on collective farms or in forced labor camps. An unknown number succumbed to famine, exposure, or sheer exhaustion.

The National Genocide Museum, known under the Khmer Rouge regime as S-21, was a prison camp whose inmates were subjected to unspeakable tortures before they were executed. Out of the 20,000 people sent there, only seven adults and three children survived. A high-school campus before the Khmer Rouge took over, it consists of four nondescript four-story buildings embraced by concrete walls and coils of barbed wire. Each classroom was broken up into 20 or 25 cramped, brick-walled cells. Held there in leg irons, voiding their bladders and bowels into small, army-issue ammunition boxes, prisoners were taken out daily to be tortured till they admitted to being enemies of the regime, which called itself the Angka, the Organization. Once they’d confessed, they were transferred to one of the hundreds of killing fields in Cambodia and murdered.

At first, the Angka marked government ministers, bureaucrats, intellectuals, and professional people for death; but in time almost anyone could end up in a place like S-21. If you wore glasses, for example, you were branded as an intellectual and exterminated. Often, no reason whatsoever was needed. A lot of the “enemies of the Angka” were kids under ten. Many of their executioners were themselves children, some as young as 12, brainwashed into becoming conscienceless killers.

Rithy shepherded us through the prison, past the warrens of cells, galleries of the victims’ photos, and displays of various torture devices. Some looked as if they’d been pilfered from an Inquisition museum and refurbished. The point of extracting confessions, he said, was to provide a justification for execution. Prisoners who confessed were told that they were to be rewarded with a transfer to a place with better food and treatment. In fact, they were shipped off to a killing field. Rithy’s grandfather had been one of the murdered millions.

The next point of interest was the killing field at Choueng Ek, a short distance outside Phnom Penh. In hundred degree heat, we strolled along interpretative paths. Depressions in the dusty soil marked the remnants of mass graves. As many as 8,000 people were slaughtered there. Their battered skulls, arrayed on shelves, grinned sightlessly through a narrow window that reached from the foot to the roof of a memorial tower 40-feet tall. The Khmer Rouge guards did not shoot their victims; they bludgeoned them with ox-cart axles while music blared from a loudspeaker mounted in a tree to drown out the victims’ screams. For some reason, it was called “the magic tree.” Another tree, toward the backside of the field, was the most appalling exhibit. Children were tied or chained to it and clubbed to death, Rithy said. I have seen more than my share of death and cruelty, but I could not comprehend what he’d told us. The Cambodians I’d met so far were unfailingly polite, gentle and devout. They press their hands together as if in prayer and bow when they greet each other; they fall to their knees and drop money into alms-baskets carried by saffron-robed monks. How could thousands of them have found within themselves the power to smash the heads of seven or eight year old children? From what mephitic pit had the Khmer Rouge summoned those demons? In the end, I think that the only explanation for atrocities of such depth and scale is theological: Satan’s legions aren’t a metaphor; they’re as real as the blood-stained bark on that tree, as the skulls stacked in that tall, stone tower.

While Nazi war criminals, men in their 90s, are still being tracked down and tried, only a handful of the Khmer Rouge’s senior leadership have been punished. Pol Pot, its leader in the 1970s, died of natural causes in a jungle hideout in 1998, the day before he was scheduled to be extradited to an international tribunal. Khieu Sampan, the Khmer Rouge head of state, and Nuon Chea, its chief ideologue, were not tried until 2014. A U.N.-backed court sentenced them to life in prison, a Pyrrhic victory for justice: Sampan was 83 at the time, Chea 88. Lesser figures are today walking around free; some, in fact, are government ministers and parliamentarians. “My neighbor was a Khmer Rouge soldier,” Rithy disclosed. I asked him how he felt about that. He shrugged. “We get along. He was only a 14-year-old boy then, he had been brainwashed.” Well, I thought, fourteen is old enough to know that murder is wrong, but I held my tongue. Instead, I asked what accounted for this remarkable tolerance. Rithy opined that it was the Buddhist spirit of forgiveness. Neither I nor my companions bought that explanation, or rationalization. It may be that the Cambodians prefer selective memory; to stage mass trials would open old wounds, cans of worms.

The last mind-bend occurred that evening. The Jahan pushed off on a sunset cruise, followed by a buffet dinner on the terrace deck, followed by a presentation of apsara dancing, an art that dates back more than a thousand years. Handsome men and beautiful women in traditional costumes swayed and twirled, moving their hands and arms as if they were double-jointed. But I could not fully appreciate their accomplished grace. I was preoccupied with what we’d seen earlier in the day. Long ago, a Protestant minister told me that a divine flame burns in every human soul, and whether it is faint or bright, it cannot be extinguished. The Khmer Rouge, like the Hutus in Rwanda, the Nazis in Germany, the Turks in Armenia, proved that it can be.

Apsara dancer performing on the Jahan’s terrace deck.

The royal palace in Phnom Penh.

Bricked-in cellblocks in Khmer Rouge prison, S-21

Mass grave site in a killing field, with memorial bracelets on stakes.

The post UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAY 6 (FEB.28) appeared first on Philip Caputo.

UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAYS 1& 2 (Feb.23 -24)

If ever I’d been made an offer I couldn’t refuse, it was the one that popped up in my inbox several months ago. Lindblad/National Geographic Tours asked me to be guest speaker on a 12-day “expedition” up the Mekong River through Vietnam to Cambodia and the storied temples of Angkor Wat. All expenses for me and my wife, Leslie, would be covered, except for her airfare. To top things off, I would be paid a fee for giving two 45-minute lectures on topics of my choice and — this was the really tough part — mingling with the guests at the cocktail hour and at dinner. “I think I can do that,” I said. Only a commitment to an ICU could have stopped me from giving that answer.

On Feb. 22nd, we drove 200 miles from our winter home in Patagonia, Arizona, to Phoenix, overnighted there, and flew out for Seattle early the next morning. Twenty-three hours later, at 10 p.m. local time, we landed in Saigon, aka Ho Chi Minh City. A detachment of people from Trails of Indochina, a tourist company contracted to Lindblad, whisked us through passport control and customs to an air-conditioned van that delivered us to the Park Hyatt Hotel downtown. If the Michelin Guide’s ratings did not stop at 5, it would give a 6 to the Saigon Hyatt. That’s the reason I enclosed the word expedition above in quotes. I’ve been on a few expeditions, and they all came complete with the three “D’s” — dirt, dust, and discomfort. This one was to have none of that.

This was my third trip to Saigon. The first, during the war, was on a three-day, “in-country” R & R in early 1966; the second was in 1975, when I covered the city’s fall to Communist forces and the end of the war (that would be the topic of my first lecture); and the third was in 1990, when I and a few other American writers had been invited to Vietnam for a conference with the Vietnamese Writers Union (the topic of lecture two).

The Saigon of 2017 made me feel a little like Rip Van Winkle. I hardly recognized it as we cruised around in vans and on foot the day after arriving. All the old, French-colonial buildings in the city center had been renovated — the Opera House, the Central Post Office (designed by Gustave Eiffel), Notre Dame cathedral, the Continental and Caravelle Hotels, formerly the dens-cum-watering holes for correspondents, CIA spooks, and other species of wartime wildlife. A Japanese firm was building a subway; construction cranes dominated the skyline; new office and apartment buildings were rising everywhere to accommodate a population three times what it had been thirty years ago. Ten million was the figure most often mentioned.

The multi-story mountains towered above savannas of tin-roofed shacks, squalid shops, and open-air markets. It was in those neighborhoods that I found remnants of the Saigon I remembered; but an electric energy pulsed even there, conducted by the traffic. The bicycles and rickshaws of the past had been replaced by motorbikes and scooters, countless thousands of them buzzing in all directions, their drivers and passengers wearing masks against the fume-polluted air. Ignoring all known traffic laws, they swam through the streets like schools of fish, never crashing into each other, nimbly dodging buses and trucks.

Our band of travelers found relief from the crowds and noise on a quiet street, where we lunched in a graceful villa, once upon a long time ago the residence of the U.S. Ambassador, Henry Cabot Lodge. It is now known as the Salon Saigon and features literary readings and paintings by Vietnamese artists. A most un-expeditionary lunch was served: fish soup, shrimp, prawns, and hot pork chunks bedded in steamed rice, with creme brulé for dessert. The Vietnamese government, unlike most revolutionary governments, doesn’t seem intent on wiping out all vestiges and reminders of the past. Lodge’s portrait still hangs in the dining room; he gazed at us with the cool confidence of the WASP aristocrat he’d been.

We were then taken to the Reunification Palace, which had been the residence and headquarters for South Vietnamese Presidents. On April 30th, 1975, its high iron gate became a kind of instant artifact when a North Vietnamese T-54 tank smashed through it, forcing then-President General Minh to unconditionally surrender. The building, surrounded by serene gardens, is today a museum. I found the basement bunker the most interesting exhibit: several adjoining rooms of varying size, filled with old wooden desks, typewriters, telex machines, black telephones, and communications gear that were state of the art in the 60s and 70s and were now quaint antiques. It was easy to imagine radio operators crouched under headsets, receiving and delivering desperate messages as the enemy closed in.

At a little past seven p.m., our intrepid expeditionaries — there were 47 altogether — marched out of the Hyatt and across Lam Son Square for a seven-course dinner at the Hoa Tuc restaurant. If you can find an eatery in Manhattan or Paris that serves meals as exquisite as that one, e-mail me its address immediately. I began to carry out my mingle-with-the-guests mission by chatting with a Maine couple, George and Mary Foristall, he a geologist, she a mathematician. Together, they own a company that predicts weather for off-shore oil rigs.

Needing to work off the effect of lunch and dinner, Leslie and I ambled around town. Saigon at night rocks. The streets, decorated with vivid neon sculptures to celebrate the new lunar year, were packed with young people, Vietnamese and foreigners alike. The restaurants, outdoor cafes, and night clubs were likewise jammed. A rock band was playing in the top-floor bar at the Caravelle, the very spot from which, forty-two years before, I had watched North Vietnamese jets and artillery crater the airport’s runways. Now I watched incredibly beautiful Vietnamese girls dancing in tight skirts and heels.

I had lived for two years in dreary, oppressive Moscow during the Brezhnev Ice-Age; I had made thee trips to Castro’s equally oppressive Cuba — Moscow with palm trees, we called it. The Saigon I saw in 1990, though emerging from Vietnam’s post-war repression, still had the trappings of a police state. Vibrant and booming today, it doesn’t look or feel like a city in a Marxist state. The up-scale restaurant in the Continental Hotel is called “Le Bourgeoise.” Uncle Ho was either smiling or turning over in his grave, I thought.

But I am an old newshawk. The bird of skepticism is still caged in my head, and it was singing to me: There is more to this than meets the eye; beware, Phil, of first impressions. And the next day, I, with my companions, learned that it was singing truth.

Night scene in Saigon. The building on the left is the Caravelle Hotel. Image below is the Saigon Opera House.

The post UP THE MEKONG TO ANGKOR WAT — DAYS 1& 2 (Feb.23 -24) appeared first on Philip Caputo.

March 20, 2017

SOME RISE BY SIN

A fine pre-publication review of the new novel, SOME RISE BY SIN, in the most recent issue of Publishers Weekly:

Expanding on several of the themes of his 2009 novel Crossers, Caputo’s latest is a thought-provoking story of unthinkable brutality. Former art history professor Timothy Riordan is the Catholic pastor of San Patricio, a remote village in the Mexican state of Sonora. The foothills of the Sierra Madre range in which San Patricio is located are torn by violent conflicts between drug cartels, local militias, the federal army, and police. Widely respected by the townspeople, Riordan also has the ear of military and intelligence authorities. But rather than helping him fulfill his call to serve and save his flock, Riordan’s network of connections produces deepening moral dilemmas. How, if at all, should information gained from positions of trust—including the confessional—be used in the hope of ameliorating suffering? What is the meaning of God in an apparently demonic world? As an emerging cartel called the Brotherhood wraps trafficking, murder, and mutilation in religious imagery, Riordan faces decisions that test him. A secondary narrative about expat doctor Lisette Moreno never fully gels, and the intricacies of Mexico’s shifting power balance can be difficult to follow. Yet poised as he is between unforgiving vows, lofty ideals, and searing chaos, Caputo’s Riordan is an everyman whose struggles illuminate the contradictions of human nature and the mysteries of faith.

The post SOME RISE BY SIN appeared first on Philip Caputo.

February 17, 2017

SOME RISE BY SIN/advance reviews

Here is a link to a 5-star review from Booklist and a somewhat mixed advance review from Kirkus, call it a 3-star. Kirkus will publish it on March 1st. I don’t think the novel is as predictable as the reviewer states, but then I’m biased.

Booklist first: https://www.booklistonline.com/Some-R....

Text of Kirkus:

A novel that couldn’t be more timely: the story of culture clash and compromise in Mexico. Caputo’s eighth novel revolves around two Americans, a priest and a physician, in the Mexican village of San Patricio. This is not, the author tells us, “Cancún [or] Puerta Vallarta”; rather, it is the Mexico of our darkest, wall-building fantasies, “one vast bad neighborhood, East L.A. or the South Side of Chicago on steroids.” Lest such an image seem stereotypical, it’s not—because Caputo is an acute observer of human disorder and disarray. The priest here, Father Timothy Riordan, is conflicted: about his celibacy, about his faith, and most of all about his tenuous position between the townspeople and the authorities. The doctor, Lisette Moreno, is more settled, but that is to some extent due to her privilege; she has come to Mexico by choice. Complicating everything is the presence of the Brotherhood, a gang of narcos so casually brutal that their threats and violence are never anything but believable. The moral landscape is reminiscent of Robert Stone, particularly his 1981 novel A Flag for Sunrise, which also revolves in part around a priest adrift in chaos south of the border. Stone’s perspective, though, is more apocalyptic, or perhaps, most accurately, touched with madness; among the challenges (and rewards) of his writing is the sense not just that the center isn’t holding, but also that there is no center to hold. Caputo is a more traditional novelist, and his aims are, finally, less ambitious; for all its detailed evocation of life in the village, his book is more or less a character portrait, or a pair of character portraits, in which the Americans are always in the light. That makes for a more focused effort, especially in regard to Riordan, whose self-flagellations (both real and imagined) largely drive the narrative. “His anger drained away,” Caputo writes of the priest, “and a gloom dropped over him, like a hood over a man about to be hanged.” Ultimately, however—and despite the force of the writing—this makes the novel too neat, too predictable. Caputo is taking on a messy territory, in which there are no answers, and everyone must do what they need to get along. This is the promise of his novel, that such disruption is contagious, but in the end, the book portrays less the corruption of a tarnished world than the blight of a single errant soul. This is a compelling novel that wraps up too neatly, belying the uncertainty and turmoil at its core.

The post SOME RISE BY SIN/advance reviews appeared first on Philip Caputo.

February 7, 2017

Some Rise By Sin

Full text of Library Journal pre-pub review:Library Journal 2 1 17

The post Some Rise By Sin appeared first on Philip Caputo.