Len Wilson's Blog, page 19

April 6, 2015

Creative Works: How to turn a dated church campus into a canvas for storytelling

Innovation is where the creative rubber meets the road. Often, our problem isn’t lack of ideas, but an inability to make them happen. Innovation is creativity that delivers, and all great innovations are applied creativity, which is frequently mischaracterized as the uncreative work of project development. Creative Works is a blog series devoted to ways to refine raw creative ore into complete projects.

Don’t get me wrong. I love the people at my church, Peachtree. But my first impression of the church’s physical campus in the fall of 2011 was that it needed some help.

The main building on campus is a conglomerate of construction projects. There are two fourth floors. There is no obvious front door, and after three years there are rooms I am still discovering for the first time. It’s the Winchester House of churches.

The main hallway on the second floor is 1/8 of a mile long. The first day I arrived on campus, I wandered into one end of the hall and began walking, trying to find where to go. Along both side walls of the hallway hung a random collection of artifacts from decades of ministry. The most recent were a set of large photos in ornate gold frames that looked both old and stylistically conservative for whatever time they were originally hung. 6’x10’ purple tack boards with white edging housed a random collection of notices and flyers. Three or four “information kiosks” from perhaps 30 – 40 years ago still displayed an outdated slogan and stacks of flyers and cards.

To be clear, I don’t think Peachtree is all that different from most churches or organizations that have facilities. For the most part, we don’t spend much time thinking about the spaces we spend time in. We forget what the space looks like to outsiders. But here’s the thing:

Every space tells a story. If you’re not intentional, the story your space tells about you may not be a good one. Tweet This

In the first two years of my tenure I didn’t do much about the hall. I had other “hills to climb,” so to speak, in worship, online in print, and in other arenas, and I also wasn’t sure what hornet’s nest I’d stir up by trying to address the hall. But it still bothered me.

One day last summer, our senior pastor Vic Pentz proposed to our exec pastor Marnie Crumpler and I that we hang some new images of the church around campus. I was thrilled. Like a running back who spots a hole in the mass of lineman ahead of him, I ran toward daylight.

Here’s what happened next, and how we turned an outdated physical campus into a canvas for storytelling.

1. We found the right “who.”

One of my leadership principles is that every big project starts with a “who” – a person (in addition to the primary leader), usually a strategist or specialist, who will help champion the cause and make sure the result hits close to the vision. I got our “who”, a church member who takes beautiful photos, and began to meet. We discussed different strategic approaches to the images – what kind of looks we wanted, what we could find, what we could consistently capture ourselves, who would do the work, and so on. My “who” and I have met one hour a week for most of the past year.

2. We scoured the photo archives for possibilities.

An archive search confirmed our hunch that we’d have to be intentional and set up some shots. As my photographer said, you occasionally get lucky when you just go capture an event, but it’s a 1 or 2 in a thousand chance. When you set stuff up, you control the outcome.

3. We decided to start fresh with an “editorial” look.

Editorial photography refers to the images in a magazine that aren’t ads. They tell a story – the story of the articles in the magazine. They’re characterized by a strong focal point, compelling human faces, and action. Editorial photos, we decided, would capture the variety of Peachtree’s ministries well.

4. We put a prototype together quickly.

Innovations need quick prototypes. It’s important to strike while the interest is new and high. We identified a variety of ministries and venues to photograph, and set up a quick schedule. We pulled a few from the archives, and within a few weeks had a meeting with our senior pastor and executive pastor to show samples and talk options.

5. We consulted with a sign vendor.

The vendor had previously done two projects for the church, and advised us on different approaches – a wooden frame with peel-off prints, mounted on long cleats flush against the wall, and an acrylic frame with metal stand-offs. He made physical samples of each.

6. We consulted a facility expert.

Of the many ways we could mount the images, we wanted to hear from the church’s regular architect, a man who’d worked on the facility for years on how to present them in the hallway and other campus spaces. These meetings gave us a vision for 4’x4’ square prints, and vertical and horizontal ones with the same 4’ maximum size, hung in heights to match the door frames.

7. We got buy-in from key stakeholders.

With a set of images everyone liked and two impressive, 4’ tall square prints in hand, we paraded the options around campus and got feedback from key pastors, staff and lay stakeholders. When it comes to major projects, such as this physical change to the facility, I avoid unilateral decision-making. It’s good to have your ducks lined up before you take off across the pond. With everyone’s input, we settled on the wooden option, which fit the culture and style of Peachtree better.

8. We divided the work into phases and began production.

We identified 10 favorite photos, most of which highlight long standing and beloved ministries, and sent them into production. We targeted post-Thanksgiving for the initial roll out, so among the 10 we included a few seasonal Christmas shots of campus activities.

9. We got rid of the old and rolled out the new.

Finally, after 4 months, the facilities team got to work on the old walls, removing the purple tack boards and old kiosks, and repurposing the ornate picture frames. We timed the new prints to be hung on Fridays, so we’d capture first impressions on Sunday morning. The first photos were a hit, so we set up timelines for additional phases of 10 prints. From January – March, we rolled out 10 at a time until we reached our target of 50 images.

I wish I could walk you down the hall. It’s really impressive. The result is that now, when people walk down the main halls of our campus for the first time, they’re greeted with a uniform collection of images that tell stories of the life of the church – worship, student ministries and camps, children’s gatherings, mission work, and much more. What had been an eyesore is now a feature way to communicate the values of Peachtree.

A few final tips:

While we elected to work with a vendor’s production plan, with sticky prints on wooden frames that we could peel off and replace, a standard large format printer could handle single prints at a much less expensive rate.

We considered portrait or landscape options, and ended with some of each, but at the suggestion of our exec pastor Marnie Crumpler, created many of the images with a square 4’x4’ aspect ratio. The squares ones are most dramatic.

Don’t hang them behind standard picture frame glass or plastic covers, which dull the image and dampen the impact.

What are your thoughts? Ask additional questions about the project below, and I’ll reply as soon as I can.

About the Author

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+Writer. Story lover. Believer. Branding philosopher. Breakfast chef. Tickle monster. Dr. Pepper enthusiast. Creative Director. Occasional public speaker.

March 27, 2015

5 Ways Creativity Can Transform the Mission of the Church

Here are 5 steps on how to use creativity to transform the mission work of the church.

Stop Helping People

Pastor Mike Mather of Broadway United Methodist Church in Indianapolis likes to advise his congregation to “stop helping people.”

“The church, and me in particular,” Mather said, “has done a lot of work where we have treated the people around us as if, at worst, they are a different species and, at best, as if they are people to be pitied and helped by us.” With that in mind, Broadway has — for more than a decade now — been reorienting itself. Rather than a bestower of blessings, the church is aiming to be something more humble. (source here)

With respect to the writer, I would have chosen a different word than “humble” to describe his congregation’s new mission. I think it’s both ambitious and noble. As church staffer De’Armon Harges is quoted in the article, what they are doing now is seeing people as children of God.

For a long time, the church has been doing mission based on a philosophy of consumption. It’s all wrong. It’s rooted in bad theology and bad ecclesiology and a poor understanding of human behavior. What’s more, it doesn’t work.

Look for Talents, Not Needs

In 2004, Mather hired a Harges to be a “roving listener.” His job is to spend time with the community. But here’s the trick, and what makes what Broadway does a mission of creativity.

His primary job isn’t to discover the community’s needs, but their talents.

There’s a well-researched philosophy behind it called “asset-based community development”, which is an academic way of saying it’s an approach for helping people build on what’s good in their lives rather than fixing what’s wrong.

Current literature on corporate innovation and on personal growth says the same thing – you grow not by fixing problems but by building on strengths. This doesn’t mean you ignore issues, but you instead look first to solutions within the community itself.

This is radically different than the old “charity” model which is based on a hand out and which has proven to be anything but transformative. As the article says,

A key to what’s going on now at Broadway, McKnight says, is the church’s brutally honest view of charity, which McKnight defines as “a one-way compensatory activity that never changes anything.” Instead of having people fill out forms that basically ask, “how poor are you?”, what if we ask people, “what are your gifts?”

Mather put aside the government form and, in a number of ways, began asking people new questions… Soon, the church was tapping into people who could repair cars, make quilts, paint, and cook some of the best Mexican food Mather had ever eaten. Through that, some neighbors found new livelihoods. More found a community.

If we had asked her when she showed up, tell us how poor you are, we would have all ended up poorer for it, and would missed a lot of great food.Mike Mather

Here are the three things Mather asks people to help identify talents:

What three things do you do well enough that you could teach somebody else how to do it?

What three things would you like to learn that you don’t already know?

Who, besides God and me, is going with you along the way?

Mather tells the story of a woman named Adele (beginning at 2:39 in this video) who was working but didn’t have enough to feed everyone. She originally came to the food pantry for supplies for her family. Through some creative thinking on the part of the church, Adele ended up opening her own restaurant. Wow!

Help people realize they are children of God

Poverty can create deep psychological damage. A recent article on inter-class marriages highlights the lifelong scars that a welfare Christmas can create on a person’s sense of self-worth. A mission of creativity helps people understand that they are children of God.

As Christ followers, we believe that our story starts with God creating and then inviting us to create with him. God’s design is for each of us to create – to dream and construct, to do the things that we’re passionate about. He has given us a set of good things to do with our lives. And this creative calling, which isn’t work as the world shows it – dreary interference for weekend relaxation – but the thing that actually brings purpose and passion and life.

Further, to create isn’t just for a privileged few; it’s for everyone. God wants Adele, who loves food and cooking but has many mouths to feed, not just to receive cans from the church food pantry, which sustains her but does nothing to teach her that as a child of God she has been given a set of good things to do with her life. Instead, God wants this woman to live out her passion and pursue the vocational calling he has put in her heart, and for us to love her by helping her achieve this dream.

When Mike Mather and his church give Adele the life skills to open her own restaurant, then we have helped her achieve the same meaning that any of us who pursue a calling pursue. When we help people realize their passions, they experience God’s joy, the fantastic creative feeling that we are meant to know but have lost.

When Mike Mather and his church give Adele the life skills to open her own restaurant, then we have helped her achieve the same meaning that any of us who pursue a calling pursue. When we help people realize their passions, they experience God’s joy, the fantastic creative feeling that we are meant to know but have lost.

The world tells us that the joy of creating is a privilege only for those of status whose wealth affords them the opportunity to pursue their whims. But we know better. With such creative mission, a person like Adele discovers a sense of dignity and worth as God’s daughter and we experience the joy of loving her as Jesus said, and in so doing drawing her – and ourselves – closer to our Creator.

We have not given enough attention to the fundamental truth that God is Creator. God loves to create and God made us to be creative. When we create, we experience the intimacy of a relationship with God. We love God back. And the work that we do loves others.

Apply resources toward helping people pursue passions

Mather has since expanded Harges’s job from just roving listener to a trainer of listeners. Now the church has a platoon of young people whose job is to work with people in the community to realize creative dreams. They now have groups and projects in art, law, education, and more. For more detail, including some of the consequences of this kind of approach, read the article, which describes the story of Broadway in more detail.

But it doesn’t stop here. There’s more.

Guide their journey toward becoming a new creation in Christ

A commenter on the Ministry Matters version of my source article asked, but what about teaching them Jesus?

In the Scriptures, when Jesus is asked about the bottom line, he reminded us of what we’ve been told from the beginning: Life is very simple; it boils down to loving God and loving people.

John Wesley and the Methodists translated this into a simple rubric – that we would have personal holiness and social holiness. These phrases have gotten complicated over the years. Some think of personal holiness as the management of a moral code. But it’s actually quite simple – it is loving God, or seeking after God, which means surrendering our own preferences and allowing the Holy Spirit to transform us from the patterns of this world, which are patterns of consumption, by renewing our minds using patterns of creation. And some define social holiness in the same terms espoused by a particular political ideology. But it’s actually loving people, which begins with treating people as children of God and people who have unique gifts, designed by God, to share with the world.

Further, in the church, we still think linearly – we want people to begin with intellectual assent of Jesus as personal savior, when in reality most people discover Jesus on the road, experientially, like the friends on the walk to the town of Emmaus. In church life, we don’t start by trying to make people see Jesus. We start by encouraging them to get on the road. To saddle their donkey, as I like to say.

We become aware of the work God is doing in us, drawing us to him, not beforehand, but as it is happening. We don’t gain knowledge of Christ and then become a new creation; often what happens is that we know Christ as we are being made a new creation. The knowledge isn’t cerebral but experiential. God’s doing the work, not us – we only have to be willing to seek after God, even as we trade in our surface desires for comfort for the deeper desire to make something great.

This is a theology of creativity.

I love to talk about creativity in the church. Some people think that means something artistic. But creativity is more than the arts. Designing more creative worship or producing compelling stories or branding a church with a logo is all rooted in a theology of creativity. My book Think Like a Five Year Old presents a theology of creativity, told in story form. It’s a prequel to everything I’ve ever done in ministry and I believe a basis for renewal in the church. We are creative people, made in the image of our Creator God. To create is what we’re made to do. If we can only understand this, it will transform the body of Christ and help change the world, one great project at a time.

About the Author

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+Writer. Story lover. Believer. Branding philosopher. Breakfast chef. Tickle monster. Dr. Pepper enthusiast. Creative Director. Occasional public speaker.

March 24, 2015

Test the Feasibility of Your Dream Idea With These 5 Questions

Last week I offered 5 things to do to get started on your good idea. Sometimes, though, knowing if your great idea is the right idea can be hard to figure out. How feasible is your good idea, anyway?

Writer Paul Graham, who I occasionally read (and would read more often if he had an editor), makes several good points about the feasibility of a creative idea, and how to avoid wasting your valuable creative energy.

In Graham’s experience, bad ideas happen because:

You created the first thing you thought of

You were ambivalent about being “in business” (which means creating ideas to meet people’s needs, not just because you felt like it)

You deliberately chose an impoverished market to avoid competition

He is right. I have done all three. My hunch is that most people pursuing a creative idea have done these, in some form or another. Usually the first one most.

His short list inspired me. What factors can help determine if your creative inspiration will succeed? Here’s a short list of 5 feasibility considerations.

1. Could Your Idea Sell on the Open Market?

First, forget about the difference between “good” ideas and “bad” ideas.

Usually, we dream of ideas because they sound cool. “Cool” is a bad barometer if an idea is any good.

Graham shares an old British idiom given by his father: “Where there’s muck, there’s brass.” Which means, unpleasant work pays. It’s a simple law of supply and demand. Work people like doesn’t pay well, because there’s so much supply.

This sounds bleak, but Graham offers some hope:

[This] is not to say that you have to do the most disgusting sort of work, like spamming, or starting a company whose only purpose is patent litigation. What I mean is, if you’re starting a company that will do something cool, the aim had better be to make money and maybe be cool, not to be cool and maybe make money.

You can create all day long for your own personal benefit, which can be great for your psyche. But if you want your creative ideas to have an impact on the world – to change hearts and lives – then you need to make something people want. As writer Stephen King notes in his article about what makes for a successful creative,

I’m interested in telling you how to get your stuff published, not in critical judgments of who’s good or bad. As a rule the critical judgments come after the check’s been spent, anyway. Stephen King

The only judgment on an idea in a market economy is if it ships. Could your idea sell on the open market?

2. Are you considering other people’s problems?

Part of creativity is learning to spot a good idea. A prime candidate for a good idea is that it solves someone’s problem.

This applies not just to entrepreneurialism but to any endeavor. You can be in a salaried position, working for a corporation, non-profit or church, and spend a ton of time on a bad idea that meets no direct need in the lives of your people.

Instead of starting with your idea, start by thinking of problems. Graham suggests the front page of the Wall Street Journal as a good source for finding problems to solve. I find problems in talking to people and in my daily morning web surf. As common themes emerge, I start to save them out to a folder. Then I test my concepts with the informal focus group called Colleague Nagging, where I bounce questions and ideas off of people I work with and see how they respond.

If they stare blankly, I shelve it. (I have over 100 unpublished blog posts and the number is growing). If they get excited and started responding, I am on to something.

3. Are you paying attention to your own nagging questions?

I don’t mean to suggest that you should only create as a response to the market. On the contrary, in Think Like a Five Year Old I say that it’s only in our personal experience that we find the passion that is necessary for any great work. So how do you solve this paradox between art and commerce?

The way I handle the tension is that in addition to keeping eyes open to other people’s problems, I also pay attention to my own nagging problems. If I have a personal question that won’t go away, I start to pay attention to it. I begin with a few months of taking notes and saving links.

Think Like a Five Year Old started with a basic question about creative “success” and why it ends. What happens if what you’re doing is no longer working? The more I articulated my own problems, the more I realized that many people have had a similar experience.

4. Are you avoiding a crowded market?

I used to do this. I would fool myself into thinking I could create a market. Bad idea. You’re not likely going to discover a never-before-seen pocket where creative sunshine has never previously shone. If no one has ever done anything on it, it’s probably not a great idea.

The question instead is, has anyone ever done it like you want to do it? Don’t look for an empty arena; instead, look for a fresh angle or approach in a busy arena.

In publishing, part of a good proposal is to list “Comps” – other comparables in the market, their sales history, and how yours is different. As an acquisitions editor, I needed to show there’s a market for my new idea pitch, but at the same time I listed sales figures I also needed to show how they angle on each previous work was wrong or incomplete. The market of books on creativity is large, but I asked, “Has anyone written on the combination of creativity and the life of Chrtistian faith?” And I had a hard time finding any. Bingo!

5. Do you have a good metaphor?

In addition to the angle, the other thing that makes Think Like a Five Year Old unique is its hook. It is based on a core story that comes from research showing that young children are creative geniuses. This gives the work its unique position in the market, and also makes it universal to the human experience: If we were all once geniuses, what happened?

The hook makes it compelling. It is the glue that brings it all together.

I’ve been working on my next book for several months, based on a nagging personal problem and a theme I kept finding in my online reading. A few weeks ago the hook appeared as manna from heaven, and now I am off to the races with a concept that both speaks to me personally and solves a common market problem.

What good idea have you been chewing on lately?

March 20, 2015

You Were Once a Creative Genius

NASA engineers in Houston had one possible fix. The main command module of the ship had usable carbon dioxide filters. But they were cube-shaped, and the lunar module needed cylindrical ones. In a matter of hours, the engineers on Earth had to figure out how literally to put a square peg in a round hole, using only parts available on board the ship.

A short time later, the stranded astronauts received a set of instructions from Houston. They named the device they built with the instructions “the mailbox” for its shape and the life-saving materials it delivered.

The kind of creative thinking that saved the Apollo 13 astronauts doesn’t just happen.

It’s the result of an intentional effort to foster a creative culture. (In fact, to an uncreative world, such feats seem impossible. A poll in 2009 by the British periodical Engineering & Technology found that 25 percent of people believe the moon landing was an elaborate hoax, perpetuated on a Hollywood soundstage.)

In the buildup to the Apollo 11 mission, a NASA deputy director had approached a researcher named George Land. He had lots of applicants, he said. But measuring people by standard intelligence measures (that is, the conventional IQ test) wasn’t sufficient. He needed a way to select the people who would create the best solutions because they had unusually tough questions.

NASA didn’t just find intelligent people, but people who could think differently.

They needed people who could demonstrate the sort of ingenuity that could solve the sort of problem that plagued the aborted Apollo 13 mission. Land and his team developed an instrument to measure creative thinking, and NASA implemented it as an additional step in their candidate vetting process.

The test was a rousing success and, as a measure of employee performance, highly predictive for NASA. Afterward, a question remained for Land and his research crew. They had determined how to measure existing levels of creative thinking in prospective employees, but that didn’t solve more fundamental questions. Is creativity innate, learned, or—perhaps—unlearned?

Since the test questions were simple to understand, they decided to give the same test to a group of young children. They administered it to a sample of sixteen hundred five-year-olds.

The results were astonishing.

98 percent of five-year-olds are what the NASA test described as “creative genius.”

George Land and his team of NASA-contracted researchers decided to track their young creative geniuses over time. They turned their research into a longitudinal study and, five years later, retested the same group of students. Among the same group of children, now ten years old, there was a drastic change: only 30 percent were creative geniuses. Again, at fifteen years old, 12 percent were creative geniuses. Throughout the period of the study, and since, Land and his team tested thousands of adults, far past the flat line of statistical analysis. They learned, with an average age of thirty-one years old, that 2 percent of adults are creative geniuses.

In their famous study, Land and his team not only solved an important issue facing NASA leadership but also discovered a fundamental problem—one that plagues business, education, culture, and the life of faith.

Each of us was once a creative genius.

Somewhere along the way, though, we lose our creativity.

We may not be complete creative dolts. We can match an entree with a side dish, we can sometimes figure out when our phone’s GPS is lying to us, we can choose among twenty flavors of stationery at the store, and, if pressed, we can actually contribute an idea at a business meeting. But we’re far from what you’d call a creative genius.

As a creative director, I hear people apologize for their lack of creativity all the time.

We like to refer to a “creative person” as some sort of special species possessing rare talent. We see ourselves as somewhere in between. Perhaps circumstances dictate our choices; perhaps we become impatient with waiting and uncertainty. When we party on the weekend or get away after work with music and a drink with friends, maybe what we’re doing is trying to regain our soul because all day we’ve been trading it in for a paycheck.

The problem isn’t that most of us are incapable of creativity.

I love this book so much. As a pastor and counselor, it has always burdened me to see a person stop taking risks, stop creating, stop living life to the fullest. Thank you Len for encouraging us to dream again.Ron Edmondson, Pastor, Blogger, Church Leadership Consultant

Land’s study and other scientific studies disprove the false dichotomy of creatives versus noncreatives. Creativity recovery isn’t a switch to turn on, and to find our creative self doesn’t mean we must drag the lake of our psyche, although this may be something you’re inclined to do. Rather, creativity can be nurtured and developed. Land’s study is a scientific insight for what I believe is primarily a spiritual issue. We’ve lost our ability to create. The problem is that when we make the unexamined declaration that we are not creative, as most of us do, we rob ourselves of a powerful means of knowing and experiencing God’s work in our lives.

It’s to reclaim the wonder of your creative power.

I’ve written a book for anyone who was once a creative genius. In Think Like a Five Year Old, discover what you once had in the beginning, how you lost it, and how to get it back. It’s time to reclaim your wonder and create great things.

About the Author

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+Writer. Story lover. Believer. Branding philosopher. Breakfast chef. Tickle monster. Dr. Pepper enthusiast. Creative Director. Occasional public speaker.

March 17, 2015

Got a Great Idea? Here are 5 Things To Do To Get Started

I want to [write/draw/craft/make/create/develop/build/publish]. How do I start?

Here are my humble suggestions:

First, start collecting lots and lots of ideas.

Creativity, according to researcher Sir Ken Robinson, is simply having original ideas with value. Your dreams begin with good ideas. You may have an idea already, but it’s not enough.

It doesn’t matter what you do. Are you looking for your next big product or service? Do you lead an organization with a cultural or morale problem? Need to name your new project? Have a vague concept for a book? An idea for your next talk? New classroom technique?

In every endeavor, dreams depend on solid ideas. Making things is not magic – as with anything you want to grow, to get a few good seedlings, you need to cultivate a lot, and you need to learn how to know if your new idea is good or mediocre.

Respect ideas; they are your currency. Gather them by the bucketload. Think of idea collection as a simple math equation: you need 10x, 15x, 20x more than necessary.

For example, I have over 100 unfinished blog posts and unwritten concepts saved in a folder. That used to bug me. I thought I wasn’t being productive enough, because I wasn’t keeping up. I have come to realize that having something unfinished, not because I’m not creating but because I am busy creating something else, is okay. It means I am generating more ideas than I can use.

Second, figure out some kind of routine for capturing ideas.

One innovator I read says he writes down 10 new ideas every day. A blogger I follow does “morning pages,” which is about 3-4 pages of stream of consciousness writing to begin every day. Google invites their employees to spend a portion of their work week generating new ideas.

In my book on creativity, Think Like a Five Year Old, I talk about “flashes,” where a good idea pops in my head at random times throughout the day. I used to think, “Oh, I need to write that down,” and wouldn’t, and I’d lose the great thought. Since I can’t control when the great idea appears, a few years ago I got intentional about respecting when ideas interrupt me.

Even after a few years of practice, this remains difficult to do well. I carry a journal, but sometimes want to type instead, so some ideas live on my desktop. I acquire others via my voice dictation app on my phone. I have three or four areas where raw ideas live, and I bounce between them all. Maybe I’ll refine this at some point, but the important thing is that I capture it, no matter how inefficient the method.

Here are five places I look for good ideas.

Third, resist the urge to order or prioritize ideas.

The need to organize or edit can be overwhelming. This I believe is the single hardest part of the creative process. We want to trim, cut, and delete before it is time to do so. Instead, what you need is a free-flowing, open-ended period of input. You need new material to work with! This is when divergent thinking is important. Most of us are comfortable with editing and trimming and deleting—judging work, our own and that of others. But we’re not as comfortable with making new work. We’d rather refine than mine. It is the making of new work that is courageous. It is one thing to refine, but another altogether to mine raw ore. (That’s me quoting myself from Think Like a Five Year Old, p. 136)

This is SO HARD. I have come to believe that the creative process is a spiritual discipline. I must work at allowing the fresh idea to emerge. I want to edit myself before it’s time. I want to rate ideas’ relative merits and make decisions about which to pursue, even before the time has come to decide. I want to settle, put it to bed, close the deal.

Ideas generally don’t need closing. They need incubation, and if you shut things down too quickly, they won’t develop, they’ll hatch too soon, they’ll die on the vine.

Don’t kill your ideas by judging them too soon.

Fourth, start working on one of your ideas.

People make creativity out to be a magical or impossibly difficult thing. It’s really not. There’s only one big hard thing you have to do, and that is get past the intimidation of the blank page, the clean studio, the previous work mocking you from the shelf, and begin making something new.

Don’t worry about all of the ideas you’ve generated. This is my secret for staying creative within a busy life: I just pick one for today and start: drawing / writing / cutting / building / whatever it is you do. It’s just time.

Fifth, wait for the right mixture to emerge.

I have come to recognize that if I wait, the “right” idea will stand up and make itself known. I used to dive in and force a choice, even if I hadn’t discerned which idea was the right one; now I am more likely to wait, and make the irrational announcement to others that “something will surface.”

When I say that, I am not blowing smoke or buying time. Maybe I used to be, but now I just trust that knowing the answer, which is usually a mixture of several of the ideas I’ve been collecting and developing over a period of months, will crack open when it’s developed and ready to hatch.

What personal techniques do you use to create?

About the Author

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+Writer. Story lover. Believer. Branding philosopher. Breakfast chef. Tickle monster. Dr. Pepper enthusiast. Creative Director. Occasional public speaker.

March 14, 2015

8 Encouragements for Creative Thinkers From the Man Who Changed 1900 Years of Church Tradition

Smashed on the Sacraments

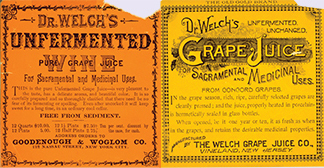

Thomas Branwell Welch was tired of seeing his friends getting wasted on leftover communion wine. The Lord’s Supper was a central act of worship, but its drink too often led to a drunkenness offensive to the temperance of his Methodist faith.

Thomas Branwell Welch was tired of seeing his friends getting wasted on leftover communion wine. The Lord’s Supper was a central act of worship, but its drink too often led to a drunkenness offensive to the temperance of his Methodist faith.Early Methodists were largely teetotalers, and the church’s first discipline, or rule book, in 1843 called for unfermented wine – grape juice – for communion. But this injunctive was difficult to fulfill for most local congregations. Grape juice naturally turns alcoholic as it sits and ferments, and it was too difficult to make fresh unfermented wine every time. Besides, most congregants had grown up drinking wine at the Lord’s Supper, like their Christian brothers and sisters had for the previous 1800 years, and saw nothing wrong with it.

What really bothered Thomas, though, was how his church friends were prone to imbibing the leftovers. One night after a clergy friend stopped by his house in a stupor, Thomas was sufficiently upset to do something about the problem.

Some years prior, Thomas had been a practicing Methodist minister. Now he was a dentist with medical and divinity degrees and interested in the intersection of church and science. He began to explore how to bottle a juice that wouldn’t ferment.

Fortunately, in the previous generation two disparate creative innovations had developed, without which his problem might not have had a solution.

#1: Growing a Good American Grape

The first trend was the development of the American grape.

For a generation, Concord, New Hampshire, resident Ephraim Bull had been obsessed with growing a marketable American grape that could compete with the lush flavors of its European cousin.

Bull had spent hours poring over the vines behind his barn with the companionship of neighbors and fellow thinkers Bronson Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Finally, in 1853, after cultivating some 22,000 seedlings over a period 20 years, Bull was satisfied with his vines and sent off some specimens to a local expo for display.

“He sowed; others reaped.”Ephraim Bull's EpitathUnfortunately, Bull took sick the day of the expo and decided not to attend his grape’s big debut. They sold well anyway. A little too well, perhaps, for soon, nursers around the southern New Hampshire region were growing their own version of Bull’s plush American grape.

Unlike some creative ideas, it was literally impossible for Bull to keep his methods a secret. All people had to do to make to their own was stick their purchase in the ground. By 1855, “concord grapes” were everywhere, and Bull had moved on to other pursuits.

#2: Keeping Juice from Turning Alcoholic

Nine years later, Louis Pasteur got a good amount of press for his new drink preparation method, in which he heated juice just enough to kill most of the bacteria that caused spoilage. After the boiling process, bacteria wouldn’t re-appear. Pasteur’s work was being used for milk, for keeping wine from going bad, and for keeping juice from becoming alcoholic.

Squeezing Creativity From a Grape

Welch read about Louis Pastuer’s new process and wondered about its potential for removing fermentation from the winemaking process. Through experimentation Welch figured out how to combine Bull’s concord grapes and Pasteur’s process in a painstaking set of tasks:

Welch read about Louis Pastuer’s new process and wondered about its potential for removing fermentation from the winemaking process. Through experimentation Welch figured out how to combine Bull’s concord grapes and Pasteur’s process in a painstaking set of tasks:squeeze (a lot of) raw grape juice

pour it into a bottle

seal it with cork and wax

place the bottle in boiling water

His method killed the yeast responsible for fermentation, leaving a fine juice suitable for communion. It also almost killed his family. Charles Welch later recalled of father’s experiments,

For three years, you squeezed grapes; you squeezed the family nearly out of the house; you squeezed yourself nearly out of money; you squeezed your friends.A young Charles Welch, to his father

Finally, Thomas slapped a label on his idea: “Dr. Welch’s Unfermented Sacramental Wine” – and asked for $12 a bottle. It was 1869.

The new grape juice bombed.

Resistance, Then Acceptance

Three reasons why it bombed: It was too expensive. Its market didn’t yet exist. Worst of all, church people thought unfermented wine wasn’t appropriate for the Eucharist. Some even called it heresy.

Eventually, broke and broken, Welch stored his bottles away and returned to his medical business.

An entire generation had passed when Welch’s son Charles had an idea. Partly due to Methodist influence in America, temperance had become a trending topic by the 1890s, and in the trend the son saw an opportunity to re-introduce his father’s idea. The fatigued father gave a warning:

Now don’t think I’m trying to discourage your pushing the grape juice. It is right for you to do so, so far as you can, without interfering with your profession and your health.An elderly Thomas Welch, to his son

Charles ignored his father’s caution and plowed ahead. He found his big break at the 1893 World’s Fair, where he introduced a new batch of “Welch’s Unfermented Wine”, minus the “Dr.” on the bottle, not just as a sacramental drink but as a juice for common consumption.

This time, Welch’s Grape Juice was a sensation. Soon, for the first time in over almost 1900 years of church history, Christians began to drink a non-alcoholic version of wine in Sunday worship, and Charles Welch became a millionaire.

There are few stories of such significant innovation in Christian history. Here are eight encouragements from the story of how one man changed almost two millennia of Christian tradition.

Eight Encouragements for Creative Thinkers and Innovators

1. You don’t have to operate from a position of authority or hold credentials or title to introduce something new.

Although he had attended seminary and for a short period worked professionally as a minister, Welch was a long time layman by the time he made his unfermented juice, and his son had no professional history in the church. They just saw a need and an opportunity.

2. Creative thinking starts from a source of un-peace.

An advocate of Methodist temperance, Welch was intensely bothered by the hypocrisy of a church moral code that preached abstinence yet served alcohol in its most sacred worship ritual. It was, as I describe in my book on creativity Think Like a Five Year Old, his source of un-peace. He was compelled to do something.

3. Limitations may seem bad but can actually be good and even necessary for creativity to occur.

We all have handicaps. We think they hinder our ability to create, but . Welch’s juice didn’t flow from an industry of abundance like the vineyards of Europe but from the land with the worst grapes, America.

4. Innovation doesn’t occur in a vacuum but works with and builds upon the work of others.

Welch’s spectacular innovation was merely the combination of two previously new ideas. He built on Bull’s grapes and Pasteur’s process. Creativity is current; it lives in time and space, and depends on the good ideas of others.

5. Innovation depends on cultural trends.

The temperance movement of which Methodism was a part gradually grew in influence throughout the 19th century, until by the 1890s it was the concern not just of a denomination of Christians but of the society as a whole. It wasn’t until the temperance movement had become a national trend that Welch’s juice took off.

6. What the church calls sacred may not be as unassailable as you’d think.

Many Christians believed that to drink anything for the Lord’s Supper beyond the very drink that Jesus served his disciples in the Scriptures was heresy. The church had practiced the use of wine for almost two millennia and it was the model Jesus had established in Scripture. Yet now, a hundred years later, many conservative denominations make the practice of drinking non-alcoholic wine just as holy and immutable.

7. Church people sometimes best respond to ideas introduced by the general market.

When it was introduced to church people as an alternative to a time-honored ritual, it bombed. When it became a beverage common to everyday life, clergy and lay people naturally saw its benefits for church use. People have a natural bias against change; sometimes its easier to do an end run around a tradition rather than try to change it directly.

8. Creative thinking and innovation are sufficiently powerful to change traditions that are thousands of years old.

Welch’s source of un-peace had no initial impact on church life. Yet 40 years later his creative idea had changed the communion experience for millions of believers.

What creative idea have you been mulling over?

About the Author

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+Writer. Story lover. Believer. Branding philosopher. Breakfast chef. Tickle monster. Dr. Pepper enthusiast. Creative Director. Occasional public speaker.

February 27, 2015

Top 25 Fastest Growing Large United Methodist Churches, 2015 Edition

Because of this, I like to follow the practices of growing congregations. What innovations are happening in the fastest growing large congregations, and how might other churches learn from them?

In 2011 I published a list of the top 25 fastest growing large United Methodist churches. Here’s the updated list, and 25 of the most innovative churches in the United Methodist Church today.

While average worship attendance is an imperfect indicator, it remains one of the best we have to measure how we’re doing at telling the story of Jesus. While I currently serve in a Presbyterian church, my background is United Methodist, and the United Methodist Church is helpful for such statistical analysis because of its episcopal organizational structure and corporate record keeping.

To qualify as “large” for the sake of this analysis, a congregation must have had at least 1000 in weekly worship in 2013, the most recent full year of average weekly worship attendance records. With the benefit of more years of records since my previous post, I elected to rank the churches on a five-year trend (my previous list was on a 3 yr trend), as a five-year trend offers a more precise indicator of sustained growth.

Click on a header to sort by that row.

Rank

Church Name

City

State

Sr Pastor

Pastor Since

2013 AWA

Rank by size

5 Yr Growth

1

Faithbridge (*)

Spring

TX

Ken Werlein

1998

3,276

9

108%

2

Harvest (*)

Warner Robbins

GA

Jim Cowart

2001

2,443

18

69%

3

Christ (*)

Fairview Heights

IL

Shane Bishop

1997

1,802

48

61%

4

White’s Chapel (*)

Southlake

TX

John McKellar

1992

6,162

2

52%

5

Morning Star (*)

O’Fallon

MO

Mike Schreiner

1999

2,122

30

52%

6

Cornerstone (*)

Caledonia

MI

Bradley Kalajainen

1990

1,751

52

47%

7

First, Flushing (*)

Flushing

NY

Joong Urn Kim

2011

1,520

63

40%

8

Korean Central

Irving

TX

Sung Chul Lee

1990

2,005

36

39%

9

Apex

Apex

NC

Gray Southern

2012

1,361

84

38%

10

Impact

Atlanta

GA

Olu Brown

2007

1,381

83

38%

11

First, McKinney

McKinney

TX

Thomas Brumett

2006

1,443

72

37%

12

Crosspoint

Niceville

FL

Rurel Ausley, Jr

1998

2,689

15

36%

13

New Covenant (*)

The Villages

FL

Harold Hendren

2011

2,034

35

35%

14

Cove

Owens Cross Roads

AL

John Tanner

1997

1,406

76

34%

15

First, Mansfield

Mansfield

TX

Mike Ramsdell / David Alexander

1995

2,305

23

33%

16

St. Luke’s

Oklahoma City

OK

Bob Long

1991

1,464

69

31%

17

Covenant

Wintersville

NC

Branson Sheets

2004

2,048

33

29%

18

Gulf Breeze

Gulf Breeze

FL

Lester Spencer

2011

2,336

21

24%

19

Good Shepherd

Charlotte

NC

Talbot Davis

1999

1,811

46

23%

20

Crossroads (*)

Concord

NC

Lowell McNaney

1995

1,470

67

22%

21

Church of the Resurrection

Leawood

KS

Adam Hamilton

1990

8,895

1

20%

22

Anona

Largo

FL

Jack Stephenson

1993

1,553

62

20%

23

Grace Fellowship

Katy

TX

James Leggett

1996

2,988

12

19%

24

Saint Timothy on the North Shore

Mandeville

LA

James Mitchell

1994

2,170

26

19%

25

The Orchard

Tupelo

MS

Bryan Collier

1997

2,164

27

18%

A few observations:

Nine churches remain from the 2011 list of growing churches.

This means they’ve had a pattern of continuous growth since at least 2006, which is remarkable. They are: Faithbridge, Harvest, Christ, Morning Star, First Flushing, New Covenant, Cornerstone, Crossroads and White’s Chapel. They’re indicated with an asterisk (*) above. Not coincidentally, 7 of these churches occupy the top 7 spots on the 2015 list.

Stable leadership continues to be key.

The average senior pastor’s tenure is over 15 years, and 19 of the 25 have served their churches over 10 years. The median and mode are both 17 years, which means that if you account for four recent changes in leadership, the length of leadership of these fast growing churches is even longer. Of course, a declining church can have a longtime leader as well, so this isn’t directly causal, but it demonstrates that one factor in growth is stability. As long term leaders move closer to retirement, succession will become an issue. First UMC, Mansfield, has recently made changes in its senior leadership to navigate this transition. William Vanderbloemen’s book Next provides further insight.

Most growing churches aren’t overnight sensations.

While perhaps the dream is explosive growth, such as my colleagues and I experienced during my tenure as creative / media director at Ginghamsburg United Methodist Church in the 1990s, when we grew from 1000 to 3000 in two years, such stories are the exception, not the rule. Most growing churches aren’t overnight sensations; they are the fruit of a long, steady climb in the same direction.

The bias is toward innovation in worship.

10 of the 25 are entirely “contemporary” or “modern” in worship style. 13 have a mix of “traditional” and modern services. Two serve primarily Korean communities, with distinct worship styles fit for their constituency. None are entirely traditional in worship style.

The “Bible Belt” still exists.

20 of the top 25 churches live in what is traditionally known as the “Bible Belt” – below the Mason Dixon line. 6 churches are in Texas (in three UM Annual Conferences), 4 in Florida, and 4 in North Carolina.

One last note is an “honorable mention” to New Story Church, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, pastored by Scott Osterberg. A church plant in 2012, they haven’t been around long enough to qualify for the list, but they’re already ranked 92nd in total United Methodist size, averaging over 1300 in weekly worship attendance by the end of 2013.

About the Author

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+Writer. Story lover. Believer. Branding philosopher. Breakfast chef. Tickle monster. Dr. Pepper enthusiast. Creative Director. Occasional public speaker.

February 23, 2015

How I Find Time to Create: My Best Secret for Productivity

A friend calls it my “pretty little boxes.” I start with a list – or lists. I make a list of pretty little boxes for the week, which accompanies every possible thing I can think of that I might want to tackle for the week. (At the bottom of the page of things for the week I also keep a separate list of future week things I’ll need to remember for later.)

People often ask me how I have time to write books and blogs when I have a busy job with lots of responsibilities and raise four children. It starts with the pretty boxes.

Then, from my week list, which I make first thing every Monday morning, I start every day by looking at the things that I have agreed to do for that day, or that are the most important to accomplish for that day. This article called it GTD – “getting things done.” And defines it as such:

At its core, “practicing GTD” means sorting through all of the various inputs that come at you every day — email inboxes, Twitter feeds, online chats with editors, personal conversations — and isolating every task that you have agreed to complete onto a single list. Then, you organize the list into completable chunks of action items, and you get things done.

The secret to managing your valuable time is to write everything down. Even the simple stuff. I see a lot of people try to do this in their head, and waste valuable energy in the process. Plato once fretted that writing would produce forgetfulness and only a semblance of the truth. He was wrong – when you write it down, you free your mind for actually doing the work instead of managing the tasks at hand. As the article above notes,

There’s also the weird brain-thing that happens when you put all of your open mental loops onto a single list: you literally stop thinking about them until it’s time to go to the grocery store and you open the list to see all of the groceries you need in a single place.

Make lists for everything. Then once your block of time for working comes open, decide which ones are the highest priority. This is how I manage a busy life, and carve out a little time to write, in spite of all of the demands on my time.

February 3, 2015

The Myth of the Blinding Flash

Opportunity is missed by most people because it’s dressed in overalls and looks like work.Thomas Edison

My middle name is Alva. I’m named after my mother’s father, who was named after the archetypal lone genius, Thomas Alva Edison. He was pretty popular guy in culture in 1909—people named their kids after him!

Legend has it that he tried 6000 different light bulb experiences until he had the “Eureka moment” that got it right. We picture him doing the work by himself, but in actuality he had a lab called the Invention Factory that started with a few people (in the photo, above) and grew to a staff of 200 at its peak. These 200 people are how Edison did 6000 experiments.

Eureka moments don’t happen to the madcap lone genius in his studio, but usually within the context of a daily grind.

The Relationship of Gift and Grind

You can’t kill your talent, but you can starve it into a coma through ignorance.Robert McKee

The best ideas can be easy to miss, because they often seem routine. That’s why it’s important to understand how to capture good ideas.

For these great moments to happen, and they do, your unconscious mind needs material to work with. Your mind cannot sift and recombine ideas—a process known as “Incubation”—if you don’t first put in the hard work. The Eureka moment is actually the last step in a long, involved process. As McKee states, “the sudden impression that the story is writing itself simply marks the moment when a writer’s knowledge of the subject has reached the saturation point.”

Maximize Connections, Not Eurekas

We don’t actually make things from nothing. It is false to believe that creativity comes from nowhere, although it sometimes seems this way. The Creator with a capital C, God, is the only entity that creates ex nihilo – from nothing. We mortals draw from multiple sources – ex materia. What we make is a new combination of old thoughts and ideas, often gleaned from other people and writings and projects.

Creativity, then, isn’t necessarily making new things, it is mixing disparate things together into new forms. It is the ability to connect the dots. Innovation comes from mixing disciplines and conventions in new ways, and creating lots of opportunities for that mixing to occur. It’s not about eurekas, it’s about connections.

Action Step: Input

The myth of the blinding flash isn’t helpful because it persuades us to not do the daily work.

The way to overcome this myth is through Input. Make daily exposure to new ideas part of your routine. I have set up a set of RSS feeds in an app called Feedly by category. This is a prime source for my Twitter feed, @Len_Wilson. To do this, you need time.

As a leader, consider: What if you built a half day into people’s job description to explore new ideas? You may think people will take advantage, but consider where its gotten One highly innovative and successful computer company:

Since around 2000, we let engineers spend 20% of their time working on whatever they want, and we trust that they’ll build interesting things. After September 11, one of our researchers, Krishna Bharat, would go to 10 or 15 news sites each day looking for information about the case. And he thought, Why don’t I write a program to do this? So Krishna used a Web crawler to cluster articles. He later emailed it around the company. My office mate and I got it, and we were like, ‘This isn’t just a cool little tool for Krishna. We could add more sources and build this into a great product.’ That’s how Google News came about.

About the Author

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+

Len Wilson Facebook Twitter Google+Writer. Story lover. Believer. Branding philosopher. Breakfast chef. Tickle monster. Dr. Pepper enthusiast. Creative Director. Occasional public speaker.

January 27, 2015

If You Want to See Creativity in Action, Look At the Bible App on Your Phone

Do you have the Bible app on your mobile device(s)? In terms of ministry impact and influence, would the Bible app be in the top 50 big ideas of the 21st century? Top 10?

The Bible app was conceived and developed by a church in Oklahoma called Lifechurch.tv. Senior pastor Craig Groeschel says he gives his leaders the freedom to implement their own visions, not so he can remain secure in retaining them, but because he genuinely believes in them.

Bobby Gruenewald, whose title is Innovation Leader, generated the concept. “YouVersion Bible app and Life Church online were his ideas so when he has an idea, he has earned the credibility to run with it,” said Groeschel. “I’m not going to stand in his way; he can create whatever God puts in his heart.”

What is your initial reaction to this story? Let me guess a few:

It’s a big honkin’ megachurch (implying that it cant happen at smaller churches)

It’s a non-denominational church (implying it can’t happen at “established” churches)

It’s rich and has the resources (implying that it can’t happen at “normal” churches)

Fine excuses, all of them. But which comes first, chicken or egg?

Maybe you’ve heard the story: Originally Craig Groeschel did ministry in the United Methodist Church (a pretty big denominational body). But when he wanted to plant a new church, he couldn’t get pass the local agency’s set of rules and restrictions. So he left the UMC and started his own church, from scratch. A big decision for him and his family, to be sure. He was walking away from jobs and pensions.

Sadly, I’ve met several Methodist church leaders who can’t get past their negative feelings about his decision. Yet it’s indisputable that Groeschel is an innovator and as we see with the Bible app, uses the same philosophy in his leadership of others. The result, aside from the phenomenal growth of Lifechurch.tv, is an app that has been downloaded tens of millions of times around the world, in the process completely disrupting an entire Bible publishing industry, and has had an impact for the work of the church that extends further than anyone’s wildest imagination.

See, we get it backwards. We only look at outcomes. Creativity that ships – innovation – is the goal, not size or growth, and most of the time that means we have to start small and lonely and with risk and resistance and with few resources.