Chris Hedges's Blog, page 98

November 21, 2019

Former White House Aide / Russia Analyst Testifies

WASHINGTON — They have heard the measured testimony of career diplomats and the mind-boggling account of a first-time ambassador who declared he was in charge of President Donald Trump’s Ukraine policy. Now House impeachment investigators are hearing from Fiona Hill, a no-nonsense former White House national security adviser who was alarmed by what she saw unfolding around her.

Hill, who speaks rapid-fire and in the distinctive accent of the coal country of northeastern England where she grew up, is testifying Thursday about what she witnessed inside the White House as two men — Ambassador to the European Union Gordon Sondland and Trump’s personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani — carried out foreign policy for an unconventional president.

She is a distinguished Russia analyst who took a break from the think-tank world to serve as a national intelligence officer from early 2006 to late 2009. She took another leave from the Brookings Institution in early 2017 to join the National Security Council at the start of the Trump administration, a decision that raised eyebrows at the time.

Related Articles

Gordon Sondland Says 'Everyone' Knew of Quid Pro Quo

by

GOP-Requested Witness Rejects Trump ‘Conspiracy Theories’

by

White House Slams ‘Illegitimate’ Hearing

by

Hill built her reputation on her insights into Russian President Vladimir Putin and clear-eyed view of the threats posed by Russia, yet went to work for a president who discounted Russian election interference and appeared to believe in Putin’s good intentions.

In closed-door testimony last month, Hill testified that she spent an “inordinate amount of time” at the White House coordinating with Sondland, whose donation to Trump’s inauguration preceded his appointment as ambassador to the EU. Sondland testified Wednesday that Trump and Giuliani sought a quid pro quo with Ukraine, and that he was under orders from the president to help make it happen.

Sondland said Trump wanted Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy to announce investigations of Democrats before he would agree to welcome him at the White House. As the push progressed, Trump also held up nearly $400 million in military aid that Ukraine was counting on to fend off Russian aggression.

During her closed testimony, Hill warned of the risks posed by the shadow diplomacy being run by Giuliani and his associates, including two Soviet-born Florida businessmen who now face campaign finance charges. She said she told Sondland: “You’re in over your head. I don’t think you know who these people are.”

She described Sondland as a counterintelligence risk because of his use of a personal cellphone, including in Ukraine, where the networks are easily hacked by Russia. Sondland confirmed Wednesday that he called Trump on his cellphone from a restaurant in Kyiv.

David Holmes, a U.S. diplomat in Kyiv who overheard that July 26 call, also is testifying Thursday as investigators wrap up two weeks of public hearings. Holmes heard Trump ask Sondland whether Zelenskiy was going to conduct the investigations he wanted and be told he would.

Unlike Sondland, who explained discrepancies in his testimony by saying he doesn’t take notes, Hill is a meticulous note taker. She says it was a habit she learned from the first grade because her town was so poor that pupils didn’t have textbooks.

In her opening statement Thursday, she said her working-class accent would have impeded her in England in the 1980s and 1990s but her poor background has never set her back in America, where she has lived since earning a doctorate at Harvard. She said her father, a coal miner since the age of 14, had dreamed of emigrating to the U.S. and always wanted someone in the family to make it to the country he saw as a “beacon of hope in the world.” Hill became an American citizen in 2002.

Hill left the administration about a week before the July 25 call in which Trump asked Zelenskiy to investigate his Democratic rival Joe Biden, his son and a discredited conspiracy theory that Ukraine, not Russia, interfered in the 2016 election. She learned the details only when the White House released a rough transcript in September and said she was shocked. “I sat in an awful lot of calls, and I have not seen anything like this,” she said.

But the call did not come out of the blue. It was an outgrowth of a July 10 meeting of U.S. and Ukrainian officials at the White House that Hill witnessed and described to lawmakers in vivid detail.

Hill said Sondland “blurted out” that he and Trump’s acting chief of staff, Mick Mulvaney, had worked out a deal for Ukraine’s president to visit the White House in exchange for opening the investigations. Her boss, national security adviser John Bolton, “immediately stiffened” and ended the meeting.

When Sondland led the Ukrainians to a room downstairs in the White House to continue the discussions, Bolton sent Hill to “find out what they’re talking about.” As she walked in, Sondland was trying to set up the meeting between the two presidents and mentioned Giuliani. Hill cut him off.

She reported back to Bolton, who told her to tell an NSC lawyer what she had heard and to make clear that “I am not part of whatever drug deal Sondland and Mulvaney are cooking up on this.”

Sondland on Wednesday pushed back on Hill’s account. He said he doesn’t remember the meeting being cut short and denied that by carrying out Trump’s Ukraine policy he was engaging in “some kind of rogue diplomacy.” He said Ukraine was part of his portfolio from the start, and said it’s “simply false” to say he “muscled” his way in.

Hill made clear in her testimony that she was frustrated by Sondland, particularly over his casual use of cellphones. He not only used his to call Trump and foreign officials, he was giving out her number as well. Officials from Europe would appear at the gates of the White House and call her personal phone, which was kept in a lockbox. She would later find messages from irate officials who had been told by Sondland that they could meet with her.

She is sensitive to security risks. While writing a book on Putin published in 2013, she said her phone and Brookings’ computer system were repeatedly hacked.

During her deposition, Hill’s temper flared when asked about conspiracy theories, including those espoused by Trump and his allies, seeking to deny Russia interfered in the 2016 presidential election. The reason she joined the Trump administration, she said, was because the U.S. is “in peril as a democracy” as a result of interference by Russians and others.

“And it doesn’t mean that other people haven’t also been trying to do things, but the Russians were who attacked us in 2016, and they’re now writing the script for others to do the same,” she said. “And if we don’t get our act together, they will continue to make fools of us internationally.”

In her opening statement, Hill said the theory that Ukraine, not Russia, was responsible for the 2016 election interference “is a fictional narrative that has been perpetrated and propagated by the Russian security services themselves.”

And Russia’s security services are gearing up to repeat their interference in the 2020 election. “We are running out of time to stop them,” she said. “In the course of this investigation, I would ask that you please not promote politically driven falsehoods that so clearly advance Russian interests.”

America Will Never Live Down Trump’s War Crime Pardons

Donald Trump loves him some bluster, worships machismo, and always has. Spectacle over substance has long been the name of his game. Decades before his successful presidential run, back when he was still a cartoon billionaire playboy, Trump took out a full-page newspaper advertisement that argued that New York state should bring back the death penalty for five adolescents arrested in 1989 for allegedly beating and raping a jogger—even though the boys hadn’t yet been convicted. Turns out that the infamous Central Park Five were later exonerated by DNA evidence. To this day, Trump refuses to apologize, even though his suggestion would have resulted in the execution of five innocent kids. But regret isn’t part of The Donald’s playbook.

Neither is adherence to facts, or recognition of history. Trump illustrated this point on the 2016 campaign trail, when he repeated a demonstrably false story about how then-Capt. John J. Pershing (future commanding general for all U.S. forces in World War I)—“a rough, rough guy”—had, during the brutal American counterinsurgency in the Philippines (1899-1913), once captured 50 Muslim “terrorists,” dipped 50 bullets in pig’s blood, shot 49, and set the sole survivor loose to spread the tale to his rebel comrades. The outcome, or moral of the story, according to Trump, was that “for 25 years, there wasn’t a problem, OK?” Well, no, actually, the Philippine insurgency dragged on for another decade, and a Muslim-separatist rebellion continues in the islands to this day.

No matter. For Trump, as the saying goes, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” In these strange times, the current occupant of the Oval Office, “the leader of the free world,” revels in tough-guy military bravado. With an apparently crippling case of bone spurs keeping him out of combat in Vietnam, Trump has had the luxury of reveling in the romance of war, having never seen its atrocities up close. Paradoxically, the candidate-turned-president who regularly rails against endless war (but rarely puts his money where his mouth is) isn’t exactly averse to combat in general. Rather, while he rightfully critiques expensive, aimless wars, Trump thinks conflicts should be short and “savage.”

Which may be why The Donald seems to have such a soft spot for American soldiers accused of war crimes. This week, the self-styled anti-war president pardoned two notorious alleged war criminals and reversed the demotion of a third. The decision got passing attention from the mainstream press, but quickly faded behind the raucous distraction of the impeachment show unfolding on Capitol Hill. Nonetheless, this was a profound matter, with serious implications. Trump’s pardons may play well with his flag-waving, nationalistic base, but they also encourage indiscipline in the military ranks and—like the Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo fiascos—stain America’s reputation in the world, motivate extremists and thereby make the nation less safe.

I was a combat soldier for my entire adult life. I know the vexing intricacies of counterinsurgency, of sorting friend from foe in foreign lands where no one wears uniforms. I know the immense power young sergeants and officers wield over life and death in distant wars, and the temptation to abuse it. I too have stepped up to the abyss in the wake of infuriating attacks in which brothers die and no enemy pays—or even appears. Still, all three of these presidential pardon recipients were accused—in the face of substantial evidence—of murdering prisoners or civilians on the battlefield. Two hadn’t even faced trial yet. Furthermore, a couple of these guys were turned in or testified against by their fellow troopers, many in the same unit as the accused. That’s extraordinarily rare. Think the police “blue wall of silence” is sturdy? The military invented the concept.

Now, one dirty secret must be aired: Trump’s “mercy” (the foreign victims received none from the accused) pardons provide genuine red meat for some of the military’s frustrated rank and file, who undoubtedly feel abandoned by the American people and used and abused by their government in unwinnable wars. Many, but not all, inherently sympathize with fellow soldiers caught up in the complexities and chaos of guerrilla wars waged among the local populace. But that’s why the military has officers, laws, a chain of command.

War crimes cases aren’t supposed to be popularity contests; they are careful legal processes with specific purposes: to enforce discipline and humanity, as well as to avoid alienating the indigenous population. That’s the cardinal rule in counterinsurgency (COIN): Don’t do anything to reinforce the enemy narrative and thereby fill their ranks with new fighters. Some guerrilla war aficionados within the military have even taken to calling the concept COIN math.

Seen in this light, as a result of these pardons (and other actions), Trump acts as an unpaid “terrorist” recruiting sergeant. Many on the Arab street will see right through the transparent hypocrisy. So the U.S. has held thousands of “terror” suspects in various prisons across the Mideast, some for decades in Guantanamo Bay, often without trial, they’ll ask, but accused American war criminals get a free pass without even facing charges?

Trust me, it won’t play well abroad, even if it pleases some emotive, uninformed folks here at home. Study after study has provided empirical evidence that America’s torture program and abuses at Abu Ghraib and Gitmo were wildly counterproductive and helped infuse the ranks of Islamist groups across the Greater Middle East. Ever wonder why Islamic State always had its Western beheading victims decked out in those orange jumpsuits? Yeah, that’s what U.S.-held detainees at Guantanamo wore. It was an illustrative symbol.

Certainly, Trump, the quintessential anti-intellectual, who hardly worries about these second- and third-order effects, is uniquely, even flagrantly, obtuse. Yet, in another sense, this president is in good company, following an inherently American leadership pattern of excusing our war crimes and meting out shockingly soft punishments for the brutal transgressions of U.S. military men.

Which brings us back to the Philippines, an all but forgotten war, that was once (before Afghanistan) America’s longest. It was there that the U.S. military first experimented with waterboarding captives, there that it imported Native American containment policies and shuffled the populace into concentration camps, there where roughly one-sixth (some 500,000) of the civilian population died of war-related causes.

It was in the Philippines, in 1902, after a group of villagers attacked an occupying U.S. Army garrison at Balangiga, on the island of Samar, killing 45, that Gen. Jacob “Howling Wilderness” Smith earned his moniker. Smith, who had taken part in the massacre of Lakota Sioux at Wounded Knee, was appointed to end the resistance and “pacify” Samar. “Hell-roaring” Jake took up the task with glee. He instructed a subordinate that every native should be “treated as an enemy until he has conclusively shown that he is a friend.” Furthermore, he bellowed, “I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the better you will please me. I want all persons killed that are capable of bearing arms.” When the officer asked for an age limit, Smith quickly replied, “Persons of 10 years and older.” When the flabbergasted subordinate pressed for clarification, the general reiterated his order.

Smith’s men burned and killed their way across the island. None one knows exactly how many died. Problem was, the press caught on and wrote critical stories about Smith “the butcher.” Mark Twain published an essay in response, flippantly suggesting that the American flag be redesigned, “the white stripes painted black and the stars replaced by the skull and crossbones.” Gen. Adna Chaffee, the senior general in the Philippines, war Secretary Elihu Root, and even President Teddy Roosevelt sensed trouble. Someone had to be held accountable for the atrocities on Samar and across the archipelago, and it sure wasn’t going to be them. First, Root published the cases of 39 soldiers who had supposedly been convicted of torturing or shooting captives, but that too turned out to be a fiasco. A bit of research showed that most had simply been fined or verbally reprimanded for their horrendous crimes.

The Army, and the press, needed a scapegoat, and thus Smith was put on trial. There he played the perfect villain. He brushed off his boss, Chaffee, who had urged him to assert that he hadn’t meant his orders to be taken literally. Old “Howling Jake” refused. Chaffee, fearful for the implication of his own command in general war crimes, decided Smith’s conviction was a foregone conclusion—and found guilty he was. But as for punishment? It was remarkably mild. Root urged a lenient sentence, because Smith had, after all, been fighting “cruel and barbarous savages.” Roosevelt—himself a blustering warmonger—concurred, and Smith was merely admonished and retired with full benefits. A media pariah, he remained a hero in the eyes of many of the troops in the Philippines.

And that’s where it gets dangerous. The president, secretary of war and the top general in the Philippines had sent a message to everyone, from the lowliest private to the most senior officers, that—in distant provinces, at least—atrocities could be committed with near impunity. The press could cry foul and cause enough of a stir to force investigations now and again, but it couldn’t ensure that soldiers were really punished. The message was received loud and clear.

Thus, four years later, when Gen. Leonard Wood (namesake of an active base in Missouri) and my old 4th Cavalry Regiment bombarded and then stormed the crest of the Bud Dajo volcano to root out Muslim separatists (most armed only with knives) and their families, and massacred more than a thousand men, women and children, no one was even tried for war crimes. Pershing, that favorite of Trump, was actually horrified. Having surveyed the scene, he declared, “I would not want to have that on my conscience for the fame of Napoleon.” So much for the rough, tough pig’s blood yarn from the 2016 campaign trail.

Which all begs the question of what exactly will come of the current president’s disavowal of established military regulations and internationally codified rules of war. It’s unlikely that American infantrymen will replay the scale of a Samar or Bud Dajo-style massacre. Still, 18 years of military leadership have taught me that indiscipline—and inhumanity—starts small: a slap of a prisoner, posing for Facebook with war trophies, executing just one captive until, well, entire units go rogue.

In Vietnam not so long ago, unpunished rapes and murders by the ones and twos led, logically, to the My Lai massacre, another instance when the culprits faced little punishment despite the murder of hundreds of civilians (including babies). These days, though ground combat may not produce another Bud Dajo or My Lai, the power of unmanned (but human-piloted) drones to kill with impunity again raises the stark consequence of excusing wanton cruelty.

This week, Trump has done just that: undercut the military justice system and endorsed American brutality. The blood-soaked consequences are his, and, also, ours.

Israel’s Netanyahu Indicted on Corruption Charges

JERUSALEM — Israel’s attorney general on Thursday formally charged Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in a series of corruption cases, throwing the country’s paralyzed political system into further disarray and threatening the long-time leader’s grip on power.

Capping a three-year investigation, Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit charged Netanyahu with fraud, breach of trust and accepting bribes in three different scandals. It is the first time a sitting Israeli prime minister has been charged with a crime.

Mandelblit rejected accusations that his decision was politically motivated and said he had acted solely out of professional considerations.

Related Articles

Benjamin Netanyahu's Sinister Plot to Hold On To Power

by

Netanyahu’s Demonization of Palestinian-Israelis Backfires Spectacularly

by Juan Cole

Netanyahu's Miscalculations About Iran Will Cost Him Dearly

by Juan Cole

“A day in which the attorney general decides to serve an indictment against a seated prime minister for serious crimes of corrupt governance is a heavy and sad day, for the Israeli public and for me personally,” he told reporters.

According to the indictment, Netanyahu accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars of champagne and cigars from billionaire friends, offered to trade favors with a newspaper publisher and used his influence to help a wealthy telecom magnate in exchange for favorable coverage on a popular news site.

The indictment does not require Netanyahu to resign, but it significantly weakens him at a time when Israel’s political system appears to be limping toward a third election in under a year.

The political party of Netanyahu’s chief rival, former military commander Benny Gantz, said the prime minister has “no public or moral mandate to make fateful decisions for the state of Israel.”

Netanyahu has called the allegations part of a witch hunt, lashing out against the media, police, prosecutors and the justice system. He planned a statement later Thursday.

Mandelblit criticized the often-heated pressure campaigns by Netanyahu’s supporters and foes to sway his decision, which came after months of deliberations. Both sides had staged demonstrations outside or near his home.

“This is not a matter of right or left. This is not a matter of politics,” he said. “This is an obligation placed on us, the people of law enforcement and upon me personally as the one at its head.”

The most serious charges were connected to so-called “Case 4000,” in which Netanyahu is accused of passing regulations that gave his friend, telecom magnate Shaul Elovitch, benefits worth over $250 million to his company Bezeq. In return, Bezeq’s news site, Walla, published favorable articles about Netanyahu and his family.

The relationship, it said, was “based on a mutual understanding that each of them had significant interests that the other side had the ability to advance.” It also accused Netanyahu of concealing the relationship by providing “partial and misleading information” about his connections with Elovitch.

Two close aides to Netanyahu turned state’s witness and testified against him in the case.

The indictment also said that Netanyahu’s gifts of champagne from billionaires Arnon Milchan and James Packer “turned into a sort of supply line.” It estimated the value of the gifts at nearly $200,000.

The indictment said Netanyahu assisted the Israeli Milchan, a Hollywood mogul, in extending his U.S. visa. It was not immediately clear what, if anything, Packer, who is Australian, received in return.

The decision comes at a tumultuous time for the country. After an inconclusive election in September, both Netanyahu and Gantz, leader of the Blue and White party, have failed to form a majority coalition in parliament. It is the first time in the nation’s history that that has happened.

The country now enters an unprecedented 21-day period in which any member of parliament can try to rally a 61-member majority to become prime minister. If that fails, new elections would be triggered.

Netanyahu is desperate to remain in office to fight the charges. Under Israeli law, public officials are required to resign if charged with a crime. But that law does not apply to the prime minister, who can use his office as a bully pulpit against prosecutors and push parliament to grant him immunity from prosecution.

In the first sign of rebellion, Netanyahu’s top Likud rival on Thursday called for a leadership primary should the country, as expected, go to new elections.

“I think I will be able to form a government, and I think I will be able to unite the country and the nation,” Saar said at the Jerusalem Post Diplomatic Conference in Jerusalem. He did not address the looming criminal charges.

The only plausible way out of a third election — and the prolonged political paralysis that has gripped Israel for the past year — would be a unity government.

In September’s election, Blue and White edged Likud by one seat in the previous election. Together, the two parties could control a parliamentary majority and avoid elections.

Both Netanyahu and Gantz expressed an openness to a unity government. But during weeks of talks, they could not agree on the terms of a power-sharing agreement, including who would serve first as prime minister.

If elections are held, opinion polls are already predicting a very similar deadlock, signaling additional months of horse-trading and uncertainty.

That could now change. A poll carried out last month by the Israel Democracy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank, found that 65% of Israelis thought Netanyahu should resign as head of the Likud party if indicted, with 24% opposed. The poll had a margin of error of 4 percentage points.

Opposition politicians immediately called on Netanyahu to step down. “If he has but a drop of honor left, he would resign tonight,” said Stav Shaffir, a lawmaker with the liberal Democratic Union.

Netanyahu has refused to drop his alliance with smaller nationalist and ultra-Orthodox Jewish parties, which was a non-starter for kingmaker politician Avigdor Lieberman.

But the main sticking point has revolved around Netanyahu himself. Blue and White has said it will not sit with Netanyahu while he faces such serious legal problems, though it is open to a partnership with Likud if he is removed from the equation.

The emergence of Saar as an heir could reshuffle the deck, but challenging Netanyahu in Likud is a risky maneuver in a party that fiercely values loyalty and has had only four leaders in its 70-plus-year history.

A former lawyer and journalist, Saar was first brought into politics 20 years ago by Netanyahu, who made him his Cabinet secretary in his first term in office. Saar then established himself as a staunch nationalist who opposed Israel’s 2005 withdrawal from the Gaza Strip and resisted the prospect of a Palestinian state. He quickly rose in the Likud ranks, twice finishing first in internal elections for its parliamentary list and enjoying successful stints as education minister and interior minister after Netanyahu returned to power in 2009.

But as with others in Likud who saw their popularity rise, he too began to be perceived by Netanyahu as a threat. He quit politics in 2014 to spend more time with his family before making his comeback this year.

Despite his hard-line positions, Saar is liked and respected across the political spectrum and could prove a far more comfortable partner for unity with Gantz if elected head of Likud.

November 20, 2019

The Most Telling Moment From Wednesday’s Democratic Debate

Sen. Bernie Sanders earned audience applause and progressive praise Wednesday night for comments on the Democratic debate stage in Atlanta, Georgia endorsing a future U.S. policy that treats Palestinians like human beings.

The Vermont senator’s remarks came—unprompted—during the foreign policy portion of the debate.

“It is no longer good enough for us simply to be pro-Israel. I am pro-Israel,” Sanders said. “But we must treat the Palestinian people with the respect and dignity they deserve.”

“What is going on in Gaza right now, where youth unemployment is 60, 70 percent, is unsustainable,” Sanders added.

Bernie Sanders: “We must treat the #Palestinian people as well with the dignity & respect they deserve.”

And there you have it folks, the most courageous & principled US leader in decades.

Big Pharma Must Learn From Its Own Victims

It was evening and we were in a windowless room in a Massachusetts jail. We had just finished a class — on job interview skills — and, with only a few minutes remaining, the women began voicing their shared fear. Upon their release, would someone really hire them? Beneath that concern lurked another one: Would they be able to avoid the seductively anesthetizing drugs that put them in jail in the first place?

Their disquiet was reasonable. Everyone with me around that grey plastic table, along with the vast majority of other prisoners in the jail, was addicted to opioids. On the cinderblock wall, a laminated sign read: “We take stock of all the suffering we have experienced and caused as addicts.”

Thousands of lawsuits are making their way through the court system in an effort to force some kind of repayment from the corporations that manufactured, distributed, and dispensed billions of doses of prescription opioids. Those drugs, including OxyContin and fentanyl, have killed hundreds of thousands of Americans, while entangling untold numbers of others in addiction (and, often, in illegal activities like larceny to pay for the drugs they then craved). The pharmaceutical companies involved have, unsurprisingly, been eager to deny their culpability, which has led to a vast blame game that’s routine in our republic of finger pointing.

When a surge of opioid addiction transformed my small New England hometown, I began to write about what was happening and follow local efforts to combat the scourge. This, in turn, led me to that jail, first as a writer on assignment and eventually to the front of that ad-hoc classroom. At the same time, over the course of two years, I interviewed dozens of people in recovery. What I learned was that, nestled within this crisis (if you knew where to look), people were taking responsibility for what had happened to them and doing so in a transformative way. They had discovered that blaming others — even the worst of those drug companies — was a quick path to the bottom, while taking responsibility turns out to be a race to the top.

The “Scum of the Earth”

On a sunny fall morning, I pulled off Route 2 in central Massachusetts and into the parking lot of what used to be the Wachusett Village Inn. It still looks like a picturesque country hotel, but today it’s a detox facility and recovery center. I’m here to meet the friend of a friend. When she greets me at the front atrium, I notice that she has a lanyard around her neck with an ID indicating that she’s on staff. Years ago, though, Anna Du Puis could have been a patient here. Before she got sober, she went through detox for opioid addiction so many times she lost count.

“I’m a story of perseverance,” she assures me — and, when she says it, she seems to glow with energy.

“I’m a story of perseverance,” she assures me — and, when she says it, she seems to glow with energy.

It’s only recently that Anna has had this full-time job helping others who are, as she once was, in early recovery. Before that she sold insurance, telling no one she had been an addict and regularly hearing coworkers and others dismiss addiction as a choice and treatment as a waste of taxpayer dollars.

Thought about a certain way, the pharmaceutical companies that produced those opioids pulled off the perfect crime. They peddled addictive products that were prescribed by trusted physicians, while those who became addicted gained scant sympathy. After all, once they were hooked, they were, by definition, drug addicts. Richard Sackler, former president of Purdue Pharma and mastermind behind the marketing campaign that launched OxyContin and remade opioid prescribing practices in this country, is now infamous for referring to those who became addicted to his blockbuster drug as the “scum of the earth.”

For this we vilify Sackler — what he did was deplorable — but it’s also true that every time any of us has accepted drug addict as an unsavory epithet, we’ve given an assist to him, to Purdue, and to the rest of the pharmaceutical industry that profited not only from addiction but from our prejudice toward it. By looking down on those afflicted with this disease, we, the public, helped insulate corporate perpetrators from responsibility.

In the process, we have also missed the chance to witness something incredible.

“A Searching and Fearless Moral Inventory”

On another night in the county jail, our little group strategized together. These women would soon have to explain their criminal records to prospective employers who increasingly run background checks on applicants. So, quietly at first and then with more confidence, they practiced reflecting on their pockmarked pasts, affirming how much they had learned (a lot) and their efforts (herculean) to regain control of their lives. All of them referenced the importance of embarking on a 12-step program to recovery.

This is something I heard again and again from people in long-term recovery. Beginning with an admission of powerlessness over addiction, 12-step programs are so often transformational in part because they involve radical responsibility-taking. Even when something is someone else’s fault, the steps encourage you to look inward and ask: What was my own role? What responsibility do I have in all this? A pivotal moment comes in step four, which calls for “a searching and fearless moral inventory” of oneself. This is a breathtakingly tall order — and one that pays commensurately large dividends for those with the courage to undertake it.

“I accept myself wholly for who I am and every single thing that I’ve done in my life,” says Raj Aggarwal, who became addicted to OxyContin in the 1990s and subsequently switched to heroin. When he made that switch, he told almost no one. Whereas Oxy, which was widely prescribed by doctors, was socially acceptable, heroin was not. Like so many others, the deeper Raj waded into addiction, the more isolated he became.

Today, he has been sober for more than 15 years, and his enviable self-acceptance has liberated him to be a force for good in the world. Raj is the founder and president of Provoc, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that helps businesses create positive social change. Provoc has designed successful campaigns in areas ranging from expanding clean energy and combatting racism to boosting voter participation. Over video chat he told me that he used to think addiction was the worst thing ever to happen to him. Now, he says, “My greatest challenge has turned into a tremendous source of strength.”

The soul-searching that Raj and others engage in as part of their recovery process is not only applicable to addiction. Let’s say you’re angry about something devastating a family member said, or a colleague’s poor behavior, or maybe you’re despondent — who isn’t? — over our broken democracy. Consider the 12-step approach to investigating your own role in the situation. This doesn’t mean other people aren’t responsible, too. It just gives you a shot at seeing your actions (or your lack of them) with greater clarity. In other words, it allows us to own our shit — and then, perhaps, to take the next right step forward.

This is largely a foreign concept in our culture, at least to people who aren’t in recovery, but its promise is bottomless. As one example, it’s relevant to the problematic way the media have covered the current opioid crisis. When addiction is rampant in communities of color, the subject tends to draw minimal attention. But in recent years, as great numbers of white people have been afflicted, the media have zoomed in with stories of blue-eyed kids dying untimely deaths. And this is a place where I bear responsibility. I took up the subject of addiction only after it enveloped my overwhelmingly white hometown. In other words, I initially focused on (and so privileged) the concerns of people white like me. In retrospect, 12-step-style, I see what I did and that it reinforced the white supremacy that drenches our American world.

Maybe you’ve heard this one from the visionary novelist James Baldwin: “Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.” Here lies the key to overcoming the opioid crisis: that people in recovery are teachers for how to face the hardest things of all.

“As Long As You’re Breathing, There’s Hope”

When he filed his complaint against Purdue Pharma, Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison said, “The Sackler defendants were motivated not by human dignity or the value of human life, but by unlimited greed above all else.” Billionaire Richard Sackler unrelentingly pushed addictive drugs that destroyed lives and pulled at the threads of unraveling communities. Why? To make yet more money, of course. It turns out that, in this story, there are many kinds of addiction, and if money is your drug of choice, then (as the recent responses of multi-billionaires to the possibility of a wealth tax suggest) you’ll never have enough, no matter how much you’ve amassed.

And so, while we malign the Sackler family and other corporate executives for what really does appear to be jaw-dropping greed, their condition is instructive. At a more modest level, many of us are skating along, feeding ongoing cravings for electronic devices or wine or work or money or just fill in the blank yourself. Like minor versions of those billionaires, we, too, are often chasing a high — a brief sense of euphoria to distract us from something underneath.

Anna Du Puis told me that her drug use was a search to fill an “internal barren place of desolation.” Raj said OxyContin offered him blissful relief from his difficult childhood as an immigrant in a white neighborhood. In many thousands of cases, opioid addiction resulted from people in chronic pain searching for an answer. Yet there are many kinds of chronic pain, including despair, or a crushing sense of emptiness. Maybe the Sacklers, nightmares of greed as they have been, are in some deeper sense more like us than we’d care to think.

There is now a growing call to put them and other pharmaceutical executives in jail. After all, why should people who committed low-level crimes thanks to their addiction to the very drugs the Sacklers peddled, like the women in my class, get locked up, while they walk away with blood on their hands and billions stuffed away in bank accounts? The answer mostly has to do with who has good lawyers. Just as in the financial and foreclosure crises of 2007-2008, when corporations inflicted widespread devastation, we are unlikely to see executives behind bars for what their companies did.

And yet, as Sam Quinones, author of the remarkable book Dreamland about the roots of the opioid crisis, points out, the public has already won important victories. Back in 2014 when he was finishing his book, he says, Purdue was “untouchable.”

In the years since then, individuals and families have rejected isolation and spoken out about drug addiction. Their outcry, in turn, has transformed the problem from something taboo into a priority for local governments — and thousands of lawsuits have been the result. Quinones acknowledged that pharmaceutical companies will likely never pay anything close to the full cost of what they’ve done. And yet, as he told me by phone, “We have probably seen the last of Purdue Pharma the way it once looked, and that right there is stunning.” He’s right: that is no small feat.

Still, there’s something else that future settlements could require, something that Raj Aggarwal sees as a potentially just approach. What if a team of people in recovery from drug addiction were enlisted to teach the pharmaceutical executives what it really means to take responsibility? It’s an idea that honors those whom they most victimized, while giving the perpetrators a framework for grappling with what they’ve done and beginning to make amends.

Imagine the Sacklers embarking on a searching 12-step moral inventory of themselves. (I, at least, fantasize about this.) Cynicism tells us that, even if this were to come to pass, a group of white-collar criminals would never listen, but Anna Du Puis takes a more charitable view. “As long as you’re breathing, there’s hope,” she told me.

I learn so much from people in recovery that sometimes I think my head will explode. Instead what happens is that my heart grows.

At the county jail, we finish our final class in that windowless room and the women file back to their cells. They will soon be released. Even though I know the odds are against them, I allow myself a tiny serving of optimism. Maybe, eventually, they will be viewed as true teachers among us.

The Emerging Divide Between Sanders and Warren on Medicare for All

Economist Robert Pollin, co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, admits there is no “perfect way to fund” Medicare for All but he remains on a mission to explain why simplicity is key when it comes to building a more efficient, more humane, and less costly alternative to the current for-profit status quo.

Despite a detailed economic analysis he and his PERI colleagues put out last year—presented in a 200-page study titled “Economic Analysis of Medicare for All,” which examines the costs and benefits of legislation introduced in Congress by Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont in 2017—Pollin remains frustrated by the failure of many to grasp, or be honest about, the clear benefits of a single-payer system.

“The biggest thing that Americans will be enjoying will be something that is already being enjoyed in other advanced economies—i.e. guaranteed access to good-quality health care when one needs it, and getting the needed care without worrying about whether one can make all the various kinds of insurance payments.”

—Prof. Robert Pollin, PERI/UMassA proposal like the one put forth by Sanders in 2017, says Pollin—as well as the updated version now in the Senate as “The Medicare for All Act of 2019” (pdf)—will drive down healthcare costs for the United States overall even as everyone in the nation enjoys full and expanded coverage; even as utilization of care goes up; and even as no family ever again faces financial ruin due to tragic injury or unexpected illness.

The conversation around Medicare for All has been a focal point in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary and with leading progressives like Sanders and Sen. Elizabeth Warren facing off against their more centrist top-tier rivals Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg who oppose it, Common Dreams asked Pollin for his perspective on some of the key facets of the current debate.

The healthcare issue will almost certainly come up during Wednesday night’s Democratic Debate, hosted by NBC News, and candidates will once more try to make their case on the direction the country must take to address the crisis of medical bankruptcies, skyrocketing drug costs and insurance premiums, and the fact that tens of millions in the U.S. remain uninsured or underinsured.

Sanders has long been recognized as the nation’s leading political champion of Medicare for All, but Warren—who has repeatedly said “I’m with Bernie” on his plan—has, in recent weeks, carved her own path by offering alternative approaches regarding key implementation issues. At the beginning of the month, Warren put a detailed “pay-for” funding plan for Medicare for All in which she claimed that unless you are “in the top 1%, Wall Street, or a big corporation—congratulations, you don’t pay a penny more and you’re fully covered.”

Sanders, on the other hand, has admitted that under his approach taxes would go up for some (but not all) middle class and working families, but that without copays, deductibles, and higher costs of care—they would come out way ahead financially and in terms of security. While Warren’s financing plan received praise by many, it also raised flags for some longtime single-payer activists and policy experts who warn that her funding approach is more regressive than what Sanders has put forth. In an interview with ABC News on Nov. 3, Sanders said his plan was “much more progressive” than what Warren is proposing.

Last week, Warren unveiled a separate transition plan for Medicare for All, which once again drew both praise and condemnation from progressive observers and experts. One of the key criticisms was that Warren will essentially move, if elected, to institute a public option styled on Medicare at the outset of her term and then subsequently—no later than her third year in office, she said—would push for Medicare for All.

“Nobody is purveying more nonsensical double-talk around Medicare for All than Biden.”

With Buttigieg and Biden both attacking Medicare for All with talking points that sound a lot like the ones put forth by the insurance and pharmaceutical industries (not to mention Republicans), Pollin says clarity on key matters is needed now more than ever. Despite nearly two dozen interviews with journalists this month, he lamented, many continue to get the big picture of the story wrong.

Having done extensive research on Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, and the minimum wage—all key issues in the current primary—Pollin has become a highly sought after economist lawmakers and campaign policy shops. As such, he has provided input to both the Sanders and Warren campaigns in recent months, though he is not backing either candidate nor has he served in an official capacity for their campaigns.

In his interview with Common Dreams—a back and forth exchange which took place via email over recent weeks—Pollin explained that he was “just offering ideas as Bob Pollin, economics scribbler, with nothing politically at stake” for either himself or his fellow researchers at PERI. “I hope that this discussion helps clarify questions for lots of people,” Pollin said, “and also helps give an additional boost of confidence to Medicare for All supporters, against this relentless onslaught of outrageous attacks.” Pollin had choice words for both Buttigieg and Biden.

In order to get to the heart of understanding the economics of Medicare for All, he said, what’s needed most—beyond understanding the basic concepts of cost-savings—is being “open-minded in weighing the relative strengths and weaknesses” of the various ways such a proposal can be funded.

“As for the financing plan, you can almost put mine on the back of a matchbox.”

There are many important details to work through, says Pollin, but he wants people to understand there is a very simple bottom line: The United States of America can “deliver good-quality universal health care” to all its residents for less overall cost than we are doing now. Period.

“As for the financing plan, you can almost put mine on the back of a matchbox,” Pollin said, even as he recognized that the intense political battles ahead will be anything but simple.

If and when Medicare for All is achieved, he notes, “The biggest thing that Americans will be enjoying will be something that is already being enjoyed in other advanced economies—i.e. guaranteed access to good-quality health care when one needs it, and getting the needed care without worrying about whether one can make all the various kinds of insurance payments.”

Common Dreams: If it is “easy to pay for something that costs less,” as you stated nearly a year ago when introducing PERI’s study that reviewed the Medicare for All Act of 2017 (an earlier iteration of the current bill in the U.S. Senate put forth by Sen. Bernie Sanders earlier this year), why is it that the discussion around funding such a proposal continues to be politically unsettling for candidates and mired in complexities?

Robert Pollin: There are a few reasons for this, in my view. I’ll start with the most important reason, which is willful obfuscation, distortion or ignorance. I say willful because the basic facts are available for anyone to grasp if they choose to do so. I know this firsthand, since I have given about 20 or so interviews on exactly these questions over the past month. I tell everyone the same simple story, which is, in round numbers:

1. We can deliver good-quality universal health care to all U.S. residents at approximately $3 trillion for the first year of operation.

2. Total public funding of U.S. health care is, right now, at about $2 trillion.

3. That means we need to raise another $1 trillion in additional taxes, to substitute for the premiums, deductibles, co-pays, and out-of-pocket costs we now pay to private insurance companies.

4.We can raise that additional $1 trillion in a variety of ways. In my own proposal, I give priority to a simple set of new revenue sources that will support increased equality—i.e. help reverse the sharp long-term rise in inequality. My main proposals include, again, in round numbers:

$600 billion from new business taxes. This will mean a cut of about 8 percent on what businesses, on average, now spend on covering their workers. We can get to $600 billion either through a 1.8 percent gross receipts tax or an 8.2% payroll tax. There are advantages and disadvantages of both approaches.

$200 billion from a 3.75 percent sales tax on non-necessities. Spending on food, housing, and education will all be exempt. For lower-income households, about half of all spending will be exempt from the tax. Current Medicaid recipients will also get a tax credit to offset their sales taxes on non-necessities.

$200 billion from a wealth tax of 0.38 percent.This would exempt the first $1 million in wealth.

5. It is straightforward to project these figures into a 10-year framework, as is typically done in Washington policy circles. That is because it is reasonable to conclude, conservatively, that once we establish Medicare for All, health care spending is not likely to grow more quickly than the rate at which the overall economy grows (more likely health care spending will decline further as a share of the economy). Because of this, the growth of the economy overall will itself generate the needed additional tax revenue to finance Medicare for All without having to increase anybody’s tax rate.

So, voila, that’s it: We need to raise $1 trillion in Year 1. We get it from $600 billion in business taxes, and $200 billion respectively from a sales tax and wealth tax. The additional revenues we will need in subsequent years will come as a matter of course as the overall economy grows. Simple, right?

Some of the journalists I have spoken to report this story accurately, but at least half do not. As for presidential candidates, I have to assume that, for example, Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg are engaging in deliberate obfuscation. This is for the purpose of supporting their own proposals through which, to paraphrase Ralph Waldo Emerson, ‘private health insurance companies remain in the saddle and ride humankind.’

Leaving aside for the moment Warren’s specific pay-for proposal which she released recently, what should the U.S. public—assuming they remain skeptical or concerned about the price tags they are being presented with—understand about Medicare for All’s ability to deliver universal high-quality health care at lower costs to everyone?

Those were, of course, the fundamental questions that my co-authors and I worked on and tried to answer fairly and rigorously in our 2018 study. Here are the very basics of what we found:

1. We estimated that, as a high-end figure, total demand for health care would rise by about 12 percent. This 12 percent estimate is higher than prominent critics of Medicare for All, including Prof. Kenneth Thorpe and Charles Blahous of the Mercatus Institute.

2. Working from the research literature, we estimated that Medicare for All could generate total cost savings in the range of 19 percent relative to our existing system. There are two huge sources of cost savings: a) dramatic simplification of administrative costs by getting rid of the current multi-payer system; and b) bringing down prescription drug prices by an average of 40 percent. As it is, other advanced economies are now spending between 50 – 60 percent less than we do now while delivering, on average, better heath outcome to their populations.

3. As a general proposition, if all other advanced economies are delivering universal health care with better overall health outcomes than the U.S., and are spending roughly one-half of what the U.S. spends per person, then it shouldn’t be such a stretch to think that we, in the U.S., can design a Medicare for All system that can accomplish what has long been a standard feature of how people live in other advanced economies.

Sanders has continued to say its premature in some ways to have this detailed discussion about funding, but Warren apparently felt it necessary to go to work on a plan that would prove that middle class families would pay “not a penny” more in taxes. Is this more politics than economics?

I clearly don’t think it is premature to have detailed discussions on funding Medicare for All, since my co-authors and I wrote a 200-page study which addresses exactly that question—how to fund Medicare for All, in detail. How Sanders or Warren should handle the matter politically is another matter. Again, as a matter of principle, as opposed to politics, I actually favor middle-class people funding Medicare for All in part. My view is reflected in my specific funding proposal, that includes a sales tax on non-necessities. But as I note above, in my proposal, most of the additional funding for Medicare for All will come from business taxes and a wealth tax. The net result is that, with my proposal, the U.S. middle class will get a financial windfall under Medicare for All. We estimated that, for a household earning at the U.S. median income of about $60,000 per year, savings on health care costs—that is after getting rid of all premiums, deductibles, co-pays, and out-of-pocket expenses but now paying the 3.75 percent sales tax on non-necessities—will be between $1,600 and $8,400 per year. The differences in savings are due to what kind of health insurance this family will have had prior to Medicare for All. But the point is these families will see between $1,600 and $8,400 more for themselves under Medicare for All—the equivalent of an increase of between roughly 3 and 14 percent in their available income. This is in addition to now having full access to good-quality health care and never having to experience any kinds of financial traumas when faced with a serious health problem, for themselves or a family member.

There seems to be confusion—or at least some debate—over what constitutes a “tax” and what constitutes an “employer contribution” when it comes to the pay-for plan that Warren put out on Friday. Can you give some perspective on this?

It’s all the same thing. For political reasons, we don’t like to call it a “tax” because people hate taxes. So fine. If that’s the big hang-up, let’s call it an “employer contribution.” Or why not just stick with the term “business premiums,” i.e. a payout to businesses fully equivalent to the premiums they now pay to private insurance companies, except now the funds will be moved into the big Medicare for All funding pot.

What is “tax incidence shifting” and what are candidates, their surrogates, and/or outside analysts (including journalists) getting wrong when they explore this terrain?

Tax incidence shifting is an important part of the overall story. This term refers to, say, a business that pays a tax, but then raises its prices, so that they shift the burden of the tax onto their consumers. A related example is when businesses cover their taxes—or for that matter their health care premiums—onto their workers by reducing wages. We need to try to keep track of these effects in thinking about the fairest ways to finance Medicare for All. Here is one example that is pertinent to the current debate. Many progressive analysts favor a payroll tax to finance Medicare for All. I myself am not opposed per se. But we do have to recognize that a payroll tax raises the costs for businesses to hire more workers. All else equal, it therefore creates a disincentive to hire workers and, correspondingly, an incentive to maybe buy a new machine to increase production at the workplace rather bring on another staff member. One way to handle this problem is to use a gross receipts tax as the business revenue source rather than a payroll tax. With a gross receipts tax, businesses are taxed on their total revenue, regardless of whether their business operations use lots of workers or relatively few workers. As such, the gross receipts tax does not build in any disincentive to hire workers. The gross receipts tax does present other problems of its own. The point is that there is no perfect way to fund Medicare for All. We need to be open-minded in weighing the relative strengths and weaknesses of the alternative approaches.

But is there an important difference between Warren’s “head tax”—a fixed fee which employers would pay to Medicare per employee—compared to the payroll tax? The argument from critics like Matt Bruenig at the People’s Policy Project is that Warren’s head tax is much more regressive than a payroll tax. What is your position on that?

The difference between a head tax and a payroll tax is as follows. Let’s say you and I work for the same company. I earn $50,000 a year and you earn $100,000. Under a head tax, the company would pay the same amount in taxes for both you and I—lets say $6,000 for both of us. But if we go with a payroll tax at 8 percent, then the company would pay $4,000 for me as an employee but $8,000 for you, reflecting that your wages are twice as high as mine. So clearly, the payroll tax is more progressive. However, as I noted above, the overall idea of taxing companies per employee in any way does discourage businesses from hiring workers, all else equal. That is why, as I noted above, it may be advantageous to consider taxing businesses based on their total receipts, or revenues, regardless of whether their firms relies heavily on employing workers or, rather, depends more on operating capital equipment with a smaller workforce. It is also the case that, even if a head tax is regressive—i.e. puts the tax burden disproportionately on the lower-paid workers in a business firm—it doesn’t necessarily follow that the overall Warren taxing proposal is going to end up regressive. To determine that, we have to consider the full set of Warren tax proposals, including the wealth tax and the Wall Street transaction tax. Considering everything, I am nearly 100 percent certain that the Warren tax plan will be highly progressive.

In his initial review, The New Yorker’s John Cassidy concluded, “On health care, as in other areas, Warren has shown a willingness to consider remedies that go beyond the Washington consensus and get to the heart of the matter. She cannot be faulted for lack of boldness.” Yet, if not boldness—in your opinion—what could she be faulted for when it comes to this proposal?

The main author of the Warren Medicare for All plan is Donald Berwick, a former head of Medicare and Medicaid under President Obama. Don is a person of very high integrity and intelligence. In fact, Don worked very hard as a reviewer in helping my co-authors and me improve our own Medicare for All study. I think what Don produced for Senator Warren is quite serious and credible. I do have differences, and I look forward to working through them with Don and members of the Warren policy team (and I should declare an interest here: Warren staffers did consult with me a bit as they worked out their plan with Don. But I was never aware of where they were going with their overall approach. Nor did I know in advance that Don was leading the work). At this point, my two main differences with the Warren plan are: 1) I think their estimate of the overall costs of operating Medicare for All are higher where I put them; and 2) I favor a more simplified financing approach than what they proposed. I say this, but I also recognize that they are operating within a highly-charged political environment in offering their plan. In my case, I am just offering ideas as Bob Pollin, economics scribbler, with nothing politically at stake for me or my co-authors.

Are you saying that Warren assumes overall that Medicare for All will cost more than you believe it will? If so, can you explain why? Second, what would you point to specifically in Warren’s financing plan that is more complicated than you think it needs to be?

I am indeed saying that the Warren proposal estimates significantly higher costs to cover everybody well than what I had estimated. Over a decade, the Warren estimate is around $52 trillion. Mine is a bit under $40 trillion. I am not yet sure where these differences are coming from. The core assumptions of the Warren proposal are not that far off from mine. This is what I look forward to discussing with Don Berwick in the coming weeks. As for the financing plan, you can almost put mine on the back of a matchbox—i.e. the business gross receipts or payroll tax, generating $600 billion, and the sales tax on non-necessities and 0.38 percent wealth tax generating roughly $200 billion each. The Warren plan would require a pretty large napkin, and somebody writing in small print on both sides of that napkin. The main revenue source would still be business taxes. But the plan then introduces proposals around improving tax reinforcement, immigration and cuts to defense spending. It then also introduces targeted taxes on the financial sector, corporations and the richest 1 percent of households. This approach could very well generate the needed revenues. But it does have many more moving parts than what I proposed. More moving parts invites more complications, which, in turn, offers more opportunities for attorneys and accountants to come up with clever tax avoidance schemes.

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics who admits he is “no fan of Medicare for All,” said in an CNN op-ed last week that “Warren is right.. her Medicare for All plan won’t raise taxes on the middle class.” Zandi also said he valued that Warren had come to an economist who doesn’t necessarily back the overall proposal to check her numbers—which he said do check out. “That’s the kind of rigor we should expect from all of our presidential candidates,” he wrote. You are an economist who states openly his support for Medicare for All. If that is a moral position, how does that inform your analysis of various plans and approaches?

My credo in all research work is “guilty until proven innocent.” That is, we shouldn’t just accept any research findings at face value, especially when it is research that supports our own prior convictions, and most especially our own research. That is exactly why I asked many leading experts in the field, including Don Berwick, to give our study the most skeptical, rigorous reading that they could, and not worry in the least about hurting anybody’s feelings. That is also why I posted online all the reviews of our study, including the criticisms. If someone such as myself has a prior position in favor of Medicare for All, it is especially incumbent on us to demonstrate that our position holds up under all types of honest skepticism. Otherwise, we are not doing any favors to the causes we believe in. That is basically why it took my co-authors and me 200 pages to convince ourselves that we had a sound case, based on conservative assumptions, demonstrating that Medicare for All could deliver universal high-quality care for all U.S. residents at significantly lower costs than our present system.

You wrote Sanders an open letter in October about funding Medicare for All. Can you explain why you wrote that and explain briefly what you expressed to him? RESPONSE:

Members of the Sanders policy staff asked me to write the open letter to Senator Sanders. They did so because of the frustrations they have felt about getting the story out clearly to the public that 1) Funding Medicare for All doesn’t have to be all that complicated in its basics; 2) Medicare for All will deliver significant savings for most businesses and households; and therefore 3) Medicare for All will also be an important tool for fighting against the extreme rise of inequality that we have experienced in the United States since the early 1980s, with the onset of neoliberalism.

Sanders “wrote the damn bill,” but do you perceive any weaknesses in what the Senator has put forward in his signature legislation or how he has talked about Medicare for All on the campaign trail or in some of the primary debates thus far?

Of course, there are weaknesses in the Sanders bills of both 2017 and 2019. How could there not be? We are, after all, talking about a $3 trillion enterprise. It would be impossible to cover all features of the system equally well in a single bill. That said, the overarching intention of the Sanders bills is blazingly clear—to deliver a health care system that is transformational in terms of improving the lives of almost all of the 330 million people living in the U.S. today. In terms of how Sen. Sanders has discussed the issue so far, I can only offer praise. With the help of the California Nurses Association/National Nurses United and other progressive organizations, Sen. Sanders has put Medicare for All into the public consciousness to an unprecedented extent. Tens and perhaps hundreds of millions of people now understand that good-quality health care should be recognized as a basic right of being alive. And as a basic right, nobody should ever have to face the prospects of financial ruin due to health care needs.

In the wake of the release last week of Warren’s transition strategy for healthcare, some progressive critics warned that the Senator’s plan to first bolster the Affordable Care Act and then offer Medicare as an optional choice for those who want it over a private plan would damage the movement to achieve full Medicare for All. Once again there is a political side to this and an economic side, but how should people reconcile the two? How does an “economics scribbler” such as yourself think about these political realities?

The political realities are right there before us and can only be ignored at our peril. What exactly we do about them is another matter. Everyone should examine carefully the experience of the New Deal under President Roosevelt in the 1930s. The New Deal has a halo around it, with much justification, since it accomplished great advances in toward building a more egalitarian society, including Social Security and the minimum wage. At the same time, as Ira Katznelson documented powerfully in his 2013 book Fear Itself, FDR compromised with Southern racist politicians in enacting New Deal legislation, thus upholding the virulent institutionalized racism of that era. Obviously, we cannot accept a compromise of this nature to get Medicare for All enacted. But we will have to make some compromises. There is no evidence to date of which I am aware suggesting that getting a Congressional majority in support of Medicare for All will be easy, even under a President Sanders or Warren.

Biden’s deputy campaign manager, Kate Bedingfield, warned last week that a healthcare approach like Warren’s could lose Democrats the general election. “We’re not going to beat Donald Trump next year with double talk on health care, and we’re not going to beat him with a plan that hikes taxes on the middle-class, kicks Americans off their private insurance, and kills millions of jobs,” Bedingfield said. What do you say to that?

My response is that Ms. Bedingfield should practice what she preaches. Nobody is purveying more nonsensical double-talk around Medicare for All than Biden. Biden does not have the integrity to recognize that Medicare for All will generate net savings for virtually all U.S. residents—as I noted above, up to more than $8,000 per year for some middle-income households. This is while it also eliminates the trap of being ‘underinsured,’—i.e. having insurance, probably through your employer, but still being unable to afford the deductibles and co-pays that will result if you happen to get sick.

One outside reviewer of the PERI study you and your co-authors put out last year said that “despite stacking the deck” against Medicare for All in terms of economic assumptions, the analysis “convincingly demonstrates the substantial improvements in cost efficiency” such a program will deliver. Savings of 3% to 14% for most working families seems like a good deal. But can a Medicare for All Who Want It, as Buttigieg calls this kind of plan, reap the kind of benefits that would make it worth the political capital it would take to achieve even this middling step? We saw what happened with the ACA.

Buttigieg’s public option approach cannot produce any significant cost savings because it does not offer any opportunities for administrative simplicity. This is no small matter. Above I noted that, from our study, we estimate administrative simplification under Medicare for All as constituting about 9 percent of total system costs. Remember that the whole system costs about $3.5 trillion without any savings. If, through implementing Medicare for All, we can achieve 9 percent administration savings, that alone would therefore amount to more than $300 billion. Let’s just say that is a serious level of savings that would be foregone through any kind of public option poan.

In your mind, what’s the most sensible way to transition from what we have now to a Medicare for All system? On what kind of timeline should it be done (and why) and what are the biggest challenges for a smooth transition?

On purely analytic grounds, I think a strong case can be made for a one-year transition. Keep in mind that roughly 50 percent of the population is covered through employer plans. The employers regularly shop around for cheaper plans and then frequently actually change plans. The transition for businesses into Medicare for All will be easier than switching, on a one-time basis, from one private plan to another. The businesses will be strongly incentivized to make the switch, since, as soon as they do switch, they save money. Another 35 percent of the population are already covered with either Medicare, Medicaid, the Defense Department, the VA or other smaller programs. Switching these people from one public plan to another one should not be especially challenging. We do still have 9 percent of the population that is uninsured, and another 25 percent that are underinsured. All of these people will again have every incentive to sign up for Medicare for All. It is going to get them access to health care in ways that they have not yet experienced.

Last question. It’s the year 2032. Medicare for All was passed into law just over ten years ago and—despite early and determined efforts to undercut it—legislation very similar to the Medicare for All Act of 2019 has been firmly established into law. What are Americans enjoying when it comes to the single-payer system now in place? What have the biggest obstacles been so far and what are the system’s shortcomings compared to what existed under the previous for-profit system? Was the political battle worth it?

The biggest thing that Americans will be enjoying will be something that is already being enjoyed in other advanced economies—i.e. guaranteed access to good-quality health care when one needs it, and getting the needed care without worrying about whether one can make all the various kinds of insurance payments. As far as I can tell, all the rest is commentary.

The New York Times Won’t Give Bernie Sanders’ Climate Plan a Chance

When Sen. Bernie Sanders announced his $16.3 trillion climate plan, corporate media were quick to throw cold water on it, arguing that the Democratic presidential candidate’s plan was too expensive, and logistically and politically impossible (FAIR.org, 9/6/19). As Sanders fleshed out his plan in more detail, the media pushback continued: “Sanders’ Climate Ambitions Thrill Supporters, but Experts Aren’t Impressed,” announced a recent New York Times headline (11/14/19).

Reporter Lisa Friedman first compared Sanders’ plan to Trump’s border wall (“with the fossil fuel industry footing much of the bill, much as Mexico was to pay for the border wall”) and then panned it in no uncertain terms: “Climate scientists and energy economists say the plan is technically impractical, politically unfeasible and possibly ineffective.”

Who are the ‘experts’?

The New York Times (11/14/19) describes Bernie Sanders as “the climate candidate with the most expensive plan.”

Who are the “experts” who are troubled by Sanders’ plan? The piece quotes 11 sources, two of whom are “thrilled supporters” of the sort referenced in the headline, and another a Sanders spokesperson. A fourth is Joel Payne, who suggests Sanders’ program doesn’t “exactly check out,” but described as a “Democratic strategist,” he’s not exactly an “expert.”

Of the remaining seven sources, two are offered as examples of how “not everyone sees doom” in the Sanders climate platform: Daniel Kammen, identified as “an energy expert at the University of California, Berkeley,” who called it “audacious but doable,” and Noah Kaufman, a “researcher at Columbia University” (more specifically a climate economist), who said Sanders is “proposing policies that match” the scale of the crisis.

That leaves five critical “experts,” some of whom are not particularly critical. Paul Hawken, author of a work that “analyzes solutions to global warming,” said Sanders’ “sense of urgency in here is correct,” but it could be “more effective”—specifically, by embracing nuclear power. Jesse Jenkins, an “energy systems engineer” at Princeton University, credited Sanders with “trying to set a marker in terms of the pace and scale of spending that he’s proposing,” but doesn’t think it “represents a very nuanced understanding.” Michael Oppenheimer, “a professor of geoscience and international affairs at Princeton University,” questioned Sanders’ backing off from support of a carbon tax, but defended the candidate’s approach as appropriate for “the political arena.”

Finally, there are two people cited in the piece who are entirely critical of Sanders’ blueprint. David Victor is quoted as saying it “can’t work in the real world,” though his identification as a “professor of international relations at the University of California San Diego and a climate adviser to Pete Buttigieg” might lead a reader to question his objectivity. And Severin Borenstein, “a professor at the Haas School of Business of the University of California, Berkeley,” said, “I just don’t see that getting off the ground.”

So of the seven “experts” quoted by Friedman, two are supportive of Sanders’ proposals to fight climate disruption, two are critical and three somewhere in the middle—a weak validation of her sweeping thesis, that “climate scientists and energy economists” as a whole call the Sanders plan “impractical,” “unfeasible” and “possibly ineffective.”

Undisclosed conflicts

Worse, the bulk of the “experts” quoted by Friedman have unacknowledged conflicts of interest. Borsenstein, who can’t see Sanders’ plan “getting off the ground,” is faculty director at the Energy Institute at Haas, which takes funding from energy companies like Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric. Jenkins, who said Sanders wasn’t “very nuanced,” works at the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment, whose “E-Filliates” include ExxonMobil, NRG and Siemens. Hawken, who complained Sanders was too anti-nuclear, leads the Highwater Investment Group, whose top holdings have included Ford Motors and EnerNOC, now part of the energy conglomerate Enel, which produces nuclear power.

The Times did mention Victor’s connection to Buttigieg, but didn’t note that he runs UCSD’s Laboratory on International Law and Regulation, funded by BP and the electricity industry’s Electric Power Research Institute. (His earlier project at Sanford was bankrolled by more than $9 million from BP.) The non-“expert” Payne, in addition to being a “Democratic strategist,” is a PR consultant who has worked for General Motors, South Jersey Gas and the American Chemistry Council.

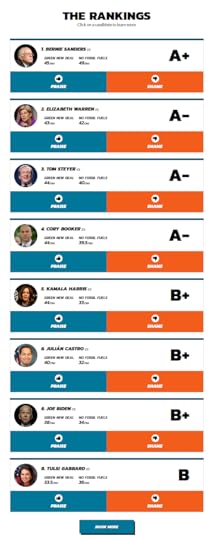

Bernie Sanders’ climate plan is the only one awarded an A+ rating by Greenpeace.

Funding doesn’t necessarily dictate the views of academics, of course; Kaufman works at Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy, which is backed by BP, Shell, ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil, but still managed to be supportive of Sanders’ program. But corporations do give money to think tanks in the hope of influencing scholarship in their favor, so the Times’ general failure to note such connections when quoting critics of Sanders does a disservice to readers.

Even with a roster of “experts” skewed towards industry-funded research, the actual quotes from Friedman’s sources, as opposed to her paraphrases of what “climate scientists and energy economists say,” present a range of disagreements about the exact methods by which the climate crisis should be addressed, but a general consensus that the crisis must be addressed urgently. And Sanders is one of a few candidates treating the climate crisis as an urgent matter—which you would think should inform the framing of an article about expert opinion of his plan.

A truly informative and fair piece here would compare Sanders’ plan to those of the other presidential candidates (including Trump). Some prominent environmental organizations do this, and rank Sanders’ plan at the top of the primary crowd. (Greenpeace awards him its only A+ score, and 350.org gives him 3/3 thumbs up, along with Cory Booker, Julian Castro, Tom Steyer, Elizabeth Warren and Marianne Williamson.)

But instead, the only comparison the Times gives readers is the misleading and unhelpful parallel it draws between Sanders’ insistence that the government-subsidized fossil fuel industry help pay for his climate plan through “litigation, fees and taxes,” and Trump’s demand that the government of Mexico foot the bill for his wall. Note that the fossil fuel industry, which has spent massive amounts of money to deny climate science and block restrictions on carbon, is made up of corporations subject to US law (at least in their US subsidiaries), unlike the sovereign country of Mexico.

Sanders’ plan to prevent global climate catastrophe and Trump’s anti-refugee wall are not obviously alike in any substantive or significant way; it’s as if the paper can’t resist slipping in gratuitous digs at Sanders any chance it gets, even as the world burns.

Meanwhile, in the presidential debates, journalist moderators have devoted fewer than 10% of their questions to the climate crisis (FAIR.org, 10/17/19). Until media start to treat the climate crisis with the urgency the scientific community continually tells us it requires, they will continue to be a major part of the problem.

A Violent Epidemic Is Taking American Lives