Chris Hedges's Blog, page 642

March 17, 2018

American History for Truthdiggers: Were the Colonists Patriots or Insurgents?

Truthdig editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the fourth installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His wartime experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 4 of “American History for Truthdiggers.” / See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3.

“Who shall write the history of the American Revolution?” John Adams once asked. “Who can write it? Who will ever be able to write it?”

“Nobody,” Thomas Jefferson replied. “The life and soul of history must forever remain unknown.”

* * *

Compare the tarring-and-feathering scene at the top of this article with the 1770 painting “The Death of General Wolfe” (immediately below this paragraph), which was featured in installment three of this Truthdig series. Painted by colonist Benjamin West, it shows North American colonists among those devotedly and tenderly attending the mortally wounded British general, who lies in a Christ-like pose. How did (at least some) North American colonists evolve from a proud celebration of empire into the riotous, rebellious mob portrayed in the illustration above? It’s an important question, actually, and it deals with an issue hardly mentioned in standard textbooks. Even rebellious “patriots” saw themselves as Englishmen right up until July 4, 1776. Others remained loyal British subjects through the entire Revolutionary War.

“The Death of General Wolfe” (1770) by Benjamin West. See part three of this Truthdig series for details of the scene and an examination of the political importance of the painting.

Most of the lay public tends to view the coming of the American Revolution as natural, predetermined, inevitable even. After all, “we” are the descendants of patriots with a special, anti-monarchical destiny. The British crown, with its intolerable taxation, merely stood in the way of American providence and thus was of course shunted aside in a glorious democratic rebellion. At least that’s the myth—the comforting preferred narrative.

The reality of the pre-revolt era was far more complex, influenced by diverse forces, motives, individual agency and contingency. The truth, as often the case, is messy and discomforting. Still, simplicity sells. Want to earn a bundle in royalties? Well, then avoid publishing an intricate analysis of lower-class colonial motivations. No one reads that stuff! It’s easy—just write another flattering biography of a “Founding Father.”

But just who were these “patriots”? What motivated them to seek open conflict with a powerful empire? How pure were their motives? Did they even represent a majority of colonists? And what of their tactics—did the ends justify the means? Only a fresh, comprehensive examination of this untidy, chaotic era promises satisfactory answers to these questions, the questions at the root of the United States’ very origins. Still, rest assured: The lead-up to the American Revolution has been, and will always be, a contested history. Perhaps Jefferson was right after all, and the soul of this history must remain unknown.

A Reassuring Tale: Common Explanations for the American Revolution

Taxes. Americans hate them with a unique national passion. After all, ours is a nation founded in opposition to insufferable, imperial taxation. Wasn’t it? One group certainly thought, and thinks, so. If you see the American Revolution as only a relic of the past, please note that in 2009, soon after the election of Barack Obama, a new conservative political movement arose and brought its version of history to the public square. The “tea party” was suddenly everywhere. Its supporters, mostly Republicans, even liked to dress up as colonists, adorning themselves with tricorner hats and carrying signs with anti-tax slogans. For these Americans, the past was immediate and President Obama was the new King George. However, as historian Jill Lepore has written, the Tea Party Revolution was more about nostalgia than serious scholarship. In the tea party’s telling—which coheres with the popular understanding—the revolution was surely all about taxes.

Monarchy. This is equally anathema to the citizenry and inextricably tied to authoritarian taxation. Surely, our revolution was also a Manichean battle between tyranny and democracy, between royalty and republicanism. Despite generations of critical scholarship, some version of these basic, twin explanations pervades Americans’ collective memory of revolution and independence.

We all know the basic economic and political chronology of the rebellion. It’s usually told in a nice, neat sequence: Stamp Act, Boston Massacre, Tea Act, Boston Tea Party, Intolerable Acts, Lexington and Concord. New tax, colonial protest, British suppression, next tax, etc. This is an altogether linear, cyclical narrative, and it emphasizes the anti-tax and anti-monarchical components of colonial motivation. We hardly consider the British side, and it appears self-evident that all colonists were patriots. Who wouldn’t be? The Brits were “intolerable.”

It’s not that taxation didn’t factor at all in rebel motivations—it most certainly did. Still, there are some awkward questions worth raising; like, if taxes directly caused the war then how do we explain that just about every new tax was repealed before 1775? Besides, the colonists paid far lower taxes than metropolitan Britons. In fact, the Sugar Act of 1764 actually lowered the tax on molasses—it simply sought to more stringently enforce it. The Tea Act didn’t upset colonists so much for the economic cost as for the mandated monopoly it granted the British East India Co.

Surely, other, political and cultural factors must have contributed to a rebellion that men were willing to die for. An honest analysis of the coming of revolution must grapple with the varied, complex motives of individual “patriots.” Indeed, the rebellion was as much social revolution as political quarrel.

What Makes a “Patriot”?

There’s just one problem: Probably no more than one-third of all colonists were actually anti-imperial “patriots.” Our Founding Fathers and their followers weren’t even in the majority. That’s not so democratic! Furthermore, the motivations of the patriots were multifaceted, diverse and—largely—regional.

If only one in three colonists became dyed-in-the-wool patriots, then what of the others, the silent majority, so to speak? Well, most historians estimate that another third were outright pro-empire loyalists. The rest mostly rode the fence, too engaged in daily survival to care much for politics; those in this group waited things out to see which side emerged on top.

That story, that reality, is—for most Americans—rather unsatisfying. Maybe that’s why it never caught on and is hardly taught outside of academia.

As discussed, this was much more than just a quarrel between Americans and Britons; it was an intense debate over what British identity meant for those residing outside the home islands. The slogan “No taxation without representation!” has caught on as a prime explanation for rebellion, but even that reality was far more complex. It wasn’t just colonists who were taxed and had no proper voice in Parliament, but also many urban Britons within the United Kingdom. Tiny, rural aristocratic districts—so-called “rotten boroughs”—could count on a seat in the assembly while densely populated towns like Sheffield and Leeds went without representation. Metropolitan Englishmen no doubt had rights that were denied to their colonial cousins, i.e. a free internal trade market and the right to do business with foreign countries. However, colonists had benefits unknown in Great Britain, such as lower property taxes. In addition, there was slavery, from which some colonists profited handsomely at the suffering of fellow humans.

The varied class-based and regional motivations for patriot or loyalist association could be seen in New York’s Dutchess County, to consider only one example. In many cases, the primary motivation was the desire of middling tenant farmers to oppose their oppressive landlords. Thus, the battle lines of tenant riots in the 1760s became the dividing lines between patriot and loyalist a decade later. In Dutchess County’s south, the landlords were loyalists and, consequently, the tenants became avid patriots. Conversely, just a few miles north at Livingston Manor, the landlord was a member of the Continental Congress. Unsurprisingly, his tenants bore arms for the British.

Why We Fight—the Complex Motives of Colonial Rebels

Ideology or economics? This question about the primary cause of the American Revolution has raged among scholars for the better part of a century. There is persuasive evidence on both sides. Still, the strict binary is itself misleading. Patriot sentiment emerged for countless individual and communal reasons. Some colonists were avid readers of John Locke or British commonwealth-men like Thomas Gordon and John Trenchard. For them, it was all about ideology and independence—life, liberty and property. They were also obsessed with alleged conspiracy and corruption at the top ranks of Parliament and the monarchy.

Another group, especially in the Northern urban centers, abhorred what they saw as unfair taxation or imperial mercantilism that suppressed both free trade and a lucrative smuggling economy. Indeed, no less a figure than John Hancock himself was a famous smuggler! Still others, mainly in the Chesapeake region, desired more land and westward expansion beyond the Appalachian Mountains into “Indian Country.” This had, after Pontiac’s Rebellion, become illegal due to the British Proclamation of 1763 that granted these lands to various native tribes.

Nor can we underestimate the class component of protest and rebellion. Merchants, artisans and laborers in Northern cities, such as Boston, tended to identify with the protest movement. These working and middle-class urbanites were egged on by firebrands like Samuel Adams—the failed tax collector and sometime brewer of beer. Adams founded a newspaper, the Independent Advertiser, which overtly pitched to the laboring classes the notion that “Liberty can never subsist without equality.” In the South, conversely, the landed gentry tended to be patriots, and it was the smallholders who were often loyalist. Still, any description of patriot motivations can hardly ignore class and the impulses of the uncouth urbanites, those whom historians have labeled “the people out of doors.”

* * *

Standard interpretations of the American revolutionary movement generally make no mention of religion. This is strange considering the profound religiosity of 18th-century colonists. While prominent Founding Fathers such as Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine were deists or agnostics, the vast majority of the population was devoutly Christian. Part of what accounts for the dearth of religious analysis among historians is no doubt the secular bias within the academic community. Still, religious fervor in the wake of the mid-18th-century Great Awakening certainly had influence over the rebellion. In comparing the religious proclivities of metropolitan Britons and English colonists in North America, one distinct difference stood out. While most Britons in the United Kingdom were members of the state’s Anglican Church, the preponderance of colonists were Protestant dissenters—Presbyterians, Baptists, Quakers and Congregationalists—who had broken with the Church of England. One would be right to expect this inverse religious situation to influence colonial protests in the 1760s and 1770s.

New Jersey stands out as a representative example, at least among the Northern and Mid-Atlantic colonies. Most yeoman farmers were highly influenced by the Great Awakening’s revivalist teachings and became Protestant dissenters. The landed gentlemen, on the other hand, stayed loyal to the hierarchical Anglican Church. The messages of revivalist preachers were distinctly anti-authoritarian and anti-materialist, resonating among the smallholders who felt threatened by landed proprietors. When imperial taxes increased and British officials sought to assert increased control, the battle lines, unsurprisingly, cohered with religious preferences.

Colonists were fiercely chauvinistic Protestants with an intense hatred of Catholics. Thus, when Parliament passed the Quebec Act in 1774, allowing religious freedom to French-Canadian habitants, many colonists threw a fit! The crown, they assumed, must be beholden to a papist, Catholic conspiracy. Such religious tolerance was unacceptable and convinced many patriots that perhaps independence was the preferred path. The old spirit of intolerable Puritan zealotry was alive and well.

* * *

Some colonists simply resented military occupation. The British decision to send uniformed regular army troops to rebellious hotbeds like Boston had an effect opposite to what was intended. This is an old story. American soldiers in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq have learned this lesson again and again as foreign military presence angered the locals and united disparate political, ethnic and sectarian groups in a nationalist insurgency. Nor were British troops—generally drawn from the dregs of English society—held in high esteem by the colonists. Most Bostonians were appalled by the uncouth manners of soldiers they described as rapists, papists, infidels or, worst of all, “Irish!”

The presence of thousands of soldiers also worsened a pervasive economic depression. Back then, off-duty soldiers and sailors were allowed to seek side work in the local economy to supplement their meager wages. They thus flooded Boston’s job market. Protests against the occupation sometimes got out of control when soldiers, thousands of miles from home in a strange land, made mistakes or overreacted. In one incident—sound familiar?—an 11-year-old Boston boy was shot dead by a trigger-happy trooper. A local journal wrote of the British occupation, “The town is now a perfect garrison.” It was not meant as a compliment.

“Boston Massacre, 1770” (1871), by Constantino Brumidi, on display in the U.S. Capitol.

However, no incident so inflamed the local consciousness—and our own historical memory—as the so-called Boston Massacre of 1770. In popular remembrance, and countless paintings, the event is depicted as a veritable slaughter perpetrated by heartless redcoats against peaceful patriot protesters. But hold on a moment. Was this really an accurate label? Do five dead men a massacre make? And what prompted the “slaughter”?

What started as snowball and rock throwing at British sentries quickly escalated into a raucous crowd shouting insults, a crowd armed with clubs and, in the case of one man, a Scottish broadsword. Some protesters grabbed at the lapels of a British officer’s uniform, several other rebels screamed “Fire, damn you!” no doubt confusing the enlisted soldiers. Finally, Benjamin Burdick, he with the broadsword, swung the weapon with all his might down upon a grenadier’s musket, knocking him to the floor. The soldier climbed to his feet and fired his musket at the crowd. Several fellow troopers did the same. The rest is history.

The soldiers and their officer were put on trial, certainly a strange allowance from a supposedly tyrannical regime. None other than a local lawyer, John Adams, defended the British troops and, taking mitigation into account, won their freedom. Adams took the case at great risk to his reputation, but he believed in equal justice for all, even redcoats. This narrative, no doubt, complicates the entire episode, and well it should. The revolutionary fairy tale to which we’ve grown accustomed is in distinct need of some nuance.

No one explanation exists for patriot motivations. Individual preferences, incentives and decisions are difficult to unpack. These were diverse peoples divided among themselves by class, religion and region. How, then, could one synthesize their countless motives? The historian Gary Nash offers an apt summary. The coming of the revolution was a “messy, ambiguous, and complicated” story of a “seismic eruption from the hands of an internally divided people … a civil war at home as well as a military struggle for national liberation.”

Revolutionary Tactics: Venerable Protest or Mob Rule?

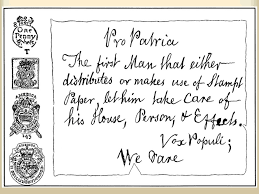

A threatening letter left at loyalist homes in New York City (1765). It reads, “Pro Patria [For one’s country], The first man that either distributes or makes use of stampt paper, let him take care of his house, person & effects,” and it is signed “Vox Populi [“voice of the people”]; We dare.”

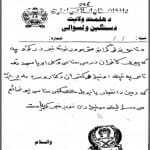

A Taliban “night letter” propaganda leaflet left on doors of villagers in Afghanistan (2010). It says: “Attention to all dear brothers: If the infidels come to your villages or to your mosques, please stop your youngsters from working for them and don’t let them walk with the infidels. If anybody in your family is killed by a mine or anything else then you will be the one responsible, not us.”

When I patrolled the mud villages of southwestern Kandahar province in Afghanistan, we sought to “protect” the population from the local Taliban insurgents. It was a difficult task. When our soldiers retired back to base camp, Taliban fighters owned the night and infiltrated the rural hamlets. A popular Islamist tactic was to leave threatening notes on the doors of suspected Afghan collaborators who dared so much as speak to the American invaders. We labeled them “night letters,” just another terror tactic, and reported their prevalence to our higher command. Few of my troopers, of course, knew that colonial patriots left the same sorts of threatening notes on the doors of alleged loyalists in Boston or Philadelphia. Is there really any difference?

Coercion has always been central to revolutions. Like it or not, the American variety was no exception. The patriot minority used threats and violence to enforce their narrative and their politics on the loyal and the apathetic alike. There was little democratic about it. Discomforting as it may be, the patriot movement was hardly a Gandhi-like campaign of peaceful civil disobedience. Patriots were passionate, they were relentless, and they were armed. Firearms were ubiquitous in the colonies, more so, even, than in Britain. Guns are as American as apple pie. So is street violence.

This was a barbaric world. Colonists slaughtered natives, beat slaves and publicly executed criminals, often leaving their bodies to rot in the town square. Alcohol abuse was endemic, and drinking men regularly settled tavern disputes with fists and knives. The patriot crowds abused tax collectors, loyalists and their social betters across the urban North. Tar and feathering, a favored and famous tactic, was far from the playful embarrassment of our imaginations. Rather, the act of putting molten tar onto human skin left many an unlucky loyalist in unimaginable pain and physically scarred. Many of the government bureaucrats so tortured were simply doing their jobs and sought only to make a living for their families. This was terrorism.

Arson and looting were often rampant as the mobs took on a life of their own. In 1765, a patriot crowd tore down the home of loyalist politician Thomas Hutchinson. In New York City, another rabble pillaged carriage houses and theaters. The motive: opposition to a relatively modest tax increase. In our collective memory, of course, such rebels are heroes. This is strange, as modern-day racial protests—Ferguson or Baltimore—are regularly pilloried as riotous criminal actions. Our patriot forebears were morally ambiguous, complex figures. Their tactics straddled the line between resistance and riot. The same could be said of the Los Angeles riots of 1992 or other urban racial outbursts. Of course, the irony is lost on us.

The Other Americans: Rebellion Through the Eyes of Loyalists, Indians and Blacks

“How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?”

—Samuel Johnson, English writer (1775)

Further tarnishing the heroic narrative of patriot ascendancy is one inconvenient fact: Most slaves preferred British to colonial rule, and most slave-holding planters were themselves patriots, especially in the South. As was the case in early colonial Virginia, American slavery and American freedom grew side by side in the late 18th century, a contradiction at the very heart of the colonial and early republican experience. This pattern endured as colonial “patriots” moved from resistance to rebellion against imperial authorities. Many modern apologists for our slave-owning founders insist that these men were merely a reflection of their time and place; a time, we are to suppose, when everyone supported slavery. Thus, we cannot critique the motives or point out the inconsistency in our esteemed forebears. Yet an honest look at the revolutionary era complicates the apologist narrative.

Indeed, the ostensibly tyrannical British practiced very little chattel slavery within the United Kingdom itself. In fact, in the Somerset v. Steuart case of 1772, England’s highest common law court ruled that chattel slavery was illegal. This judgment spooked many Southern colonial gentlemen, who began to fear the British metropolitan authorities were “unreliable defenders of slavery,” and this convinced many to join the patriot cause.

The slaves also asserted themselves and contributed to the fears of white planters. Although slave revolts were extraordinarily rare, the very threat of uprising terrified gentlemen in the Chesapeake and Deep South. In one sense the fear was justified. In South Carolina, for example, slaves constituted 60 percent of the colony’s population. During the pre-revolutionary protest movements, some slaves met in secret to discuss ways to take advantage of the growing rift between patriot and loyalist colonists. Slaves also recognized the contradiction between planters clamoring for liberty while these very same men enslaved thousands of Africans. Richard Henry Lee, of a prominent Virginia family, explained to the House of Burgesses why the slaves would not support the patriots: “from the nature of their situation, [the slaves] can never feel an interest in our cause, because … they observe their masters possessed of liberty which is denied to them.”

Adding insult to injury, in early 1775, soon after the first shots were fired in Massachusetts—at Lexington and Concord—the royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, threatened to, and eventually did, offer freedom to the slaves as a punishment to rebellious planters. This confirmed the worst fears of the landed class. Ambivalent slave owners were thereby pushed into open rebellion, and already patriot-inclined owners—such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry—became even more radicalized.

While slavery was statistically more prevalent in the South, the peculiar institution was still a continent-wide phenomenon. Even Benjamin Franklin, of Philadelphia, published advertisements in his newspapers for the sale of slaves and printed notices about runaways. Though Franklin spoke out against slavery, he himself owned five slaves, which, unlike George Washington, he never freed.

Colonial unity trumped abolitionist sentiment, even in New England. The patriots of Boston knew they needed the support of slave-saturated Virginia to win concessions from British authorities. Thus, in 1771, when an anti-slavery bill came before the Massachusetts Assembly, it failed. As James Warren wrote in his explanation to John Adams, “if passed into an act, it should have [had] a bad effect on the union of the colonies.” The first generation of Americans had an opportunity to grant basic human dignity to hundreds of thousands of chattel slaves; instead they chose their own “liberty.”

* * *

Just as hunger for land had sparked off the French and Indian War two decades earlier, so too did land speculation motivate many patriots to oppose the crown. The gentlemen of Virginia, including Washington, Jefferson and Henry, were heavily invested in large tracts of trans-Appalachian land. Jefferson alone claimed 5,000 acres. Their plan was to sell, at a profit, of course, their holdings to small farmers. Thus, when the British authorities drew the Proclamation Line of 1763 and ceded land west of the mountains to placate native unrest and avoid costly frontier wars, the planter class felt betrayed. How could the crown accede to Indian “savages” occupying their God-given lands?

There was also a class component to planter frustration. The Proclamation Line was, of course, an imaginary border, and the British had neither the inclination or military manpower to police it. Despite the law, lower-class farmers jumped the line and set up homesteads across the mountains. From the point of view of gentlemen speculators, these squatters were stealing their land. And, because the Proclamation Line made such settlements illegal, the speculators could not claim title to the land and demand recompense.

Native Americans recognized the threat to their tribal lands and saw the British authorities as their best chance to hold back the settlers. Indeed, in hindsight, we can see that the Proclamation of 1763 might have represented the last chance for genuine native autonomy in North America. These tribes were also far from isolated, backcountry actors. In fact, their trade in deerskins actually tied them to the commercial Atlantic economy to a larger extent than most middling Anglo farmers. Recognizing their leverage, the Ohio Country tribes sought confederation in an anti-British coalition, the better to threaten imperial officials and gain concessions for continued autonomy and protection from the colonists. It worked. The last thing that the deeply indebted British needed was another Indian war.

The Virginians, however, could not care less what the crown wanted. In the fall of 1774, the land speculators tried one last time to obtain the native land. Using a minor Indian raid as the pretext, the colonists launched a devastating attack on Shawnee and Mingo settlements in an attempt to conquer present-day Kentucky. In the short term, an army of 2,000 Virginians achieved its goals and forced the tribes to grant territorial concessions. However, recognizing that the tribes had signed away the land under duress, the crown authorities refused to recognize the land grab.

Like the black chattel slaves of the coastal plantations, the native tribes of the frontier felt no loyalty to the patriot cause. In fact, the imperial status quo better served slave and Indian interests than the faux “liberty” of colonial rebels. The fact that the most vulnerable populations of colonial America opposed revolution and eventually sided with the British most certainly challenges the triumphalist, egalitarian patriot narrative. Indeed, on the issues of slavery and native relations, the British appeared far more liberal than the colonists who were, themselves, seeking their own–in Jefferson’s phrase—“Empire of Liberty.” That empire would prove far more tyrannical for slaves and natives than what King George offered.

* * *

The story of the rebellion that became a revolution, a history of 1763-1775, is nearly impossible to synthesize in one essay, one chapter, or even one book. What, then, can we say? Perhaps only this: The revolution was made by a “coalition of diverse social groups,” motivated by a range of individual grievances, often at odds with one another. The patriots were by no means always democratic, and the loyalists were hardly all tyrannical monarchists. Slaves and Indians were no fans of colonists’ hypocritical, exclusivist notions of (white) liberty and freedom and often favored the crown. There is much to be proud of in the colonial revolt and, too, very much to be ashamed about. Indeed, in the truest sense, we historians are best served when we dutifully and agnostically describe the past in all its diverse, even ugly, manifestations.

Sometimes the myth is more powerful, more influential, than reality. No doubt this has been true of the lead-up to the American Revolution. To critique the motives and tactics of the “patriots” or our Founding Fathers (notice the capitalization!) is to invite rebuke and passionate defensiveness. This is, perhaps, understandable. After all, if the Pilgrims and Plymouth Rock represent our first chosen origins myth, then, most certainly, the American Revolution must stand as the second. Who we are, at least who we think we are, is acutely wrapped up in the revolutionary narrative. To question that account is to question us. Yet that is what intellectual honesty and the challenges of the present demand of us—to examine America’s founding origins, warts and all, and strive toward a truly more perfect union.

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

● James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle, and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 6: “Imperial Triumph, Imperial Crisis, 1754–1776” (2011).

● Alfred Young and Gregory Nobles, “Whose American Revolution Was It? Historians Interpret the Founding” (2011).

● Edward Countryman, “The American Revolution,” Chapters 1-3 (1985).

● Gary B. Nash, “The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America” (2005).

● Woody Holton, “Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves, and the Making of the American Revolution in Virginia” (1999).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

[The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.]

Whistleblower: Trump Data Firm Raided 50 Million Facebook Profiles

Facebook has suspended the data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica over a massive data breach that allegedly targeted millions of U.S. voters.

A whistleblower charges that the Trump campaign-linked firm reaped information from the profiles of 50 million unsuspecting American Facebook users and built a software program to feed them personalized political advertising during the 2016 election campaign.

The Trump campaign on Saturday denied using the firm’s data, The Associated Press reports. “The campaign used the RNC for its voter data and not Cambridge Analytica,” the campaign said in a statement. “Using the RNC data was one of the best choices the campaign made. Any claims that voter data were used from another source to support the victory in 2016 are false.”

But The Observer reports:

Christopher Wylie, who worked with a Cambridge University academic to obtain the data, told the Observer: “We exploited Facebook to harvest millions of people’s profiles. And built models to exploit what we knew about them and target their inner demons. That was the basis the entire company was built on.”

Documents seen by the Observer, and confirmed by a Facebook statement, show that by late 2015 the company had found out that information had been harvested on an unprecedented scale. However, at the time it failed to alert users and took only limited steps to recover and secure the private information of more than 50 million individuals.

The New York Times has the inside story:

As the upstart voter-profiling company Cambridge Analytica prepared to wade into the 2014 American midterm elections, it had a problem.

The firm had secured a $15 million investment from Robert Mercer, the wealthy Republican donor, and wooed his political adviser, Stephen K. Bannon, with the promise of tools that could identify the personalities of American voters and influence their behavior. But it did not have the data to make its new products work.

So the firm harvested private information from the Facebook profiles of more than 50 million users without their permission, according to former Cambridge employees, associates and documents, making it one of the largest data leaks in the social network’s history. The breach allowed the company to exploit the private social media activity of a huge swath of the American electorate, developing techniques that underpinned its work on President Trump’s campaign in 2016.

In December, special counsel Robert Mueller, who is investigating Russia’s role in the 2016 election, asked Cambridge Analytica to turn over documents concerning the campaign.

The Associated Press adds: “Britain’s information commissioner is investigating whether Facebook data was “illegally acquired and used.”

—Posted by Gregory Glover

Russia Boots U.K. Diplomats in Spy-Poisoning Tit for Tat

MOSCOW—Russia on Saturday announced it is expelling 23 British diplomats and threatened further retaliatory measures in a growing diplomatic dispute over a nerve agent attack on a former spy in Britain.

Britain’s government said the move was expected, and that it doesn’t change their conviction that Russia was behind the poisoning of ex-agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter in the English city of Salisbury. Prime Minister Theresa May said Britain will consider further retaliatory steps in the coming days alongside its allies.

The Russian Foreign Ministry ordered the 23 diplomats to leave within a week. It also said it is ordering the closure in Russia of the British Council, a government-backed organization for cultural and scientific cooperation, and is ending an agreement to reopen the British consulate in St. Petersburg.

The announcement followed Britain’s order this week for 23 Russian diplomats to leave the U.K. because Russia was not cooperating in the case of the Skripals, who were found March 4 poisoned by a nerve agent that British officials say was developed in Russia. They remain in critical condition and a policeman who visited their home is in serious condition.

Britain’s foreign secretary accused Russian President Vladimir Putin of personally ordering the poisoning of the Skripals. Putin’s spokesman denounced the claim.

Britain’s Foreign Office said Saturday that “Russia’s response doesn’t change the facts of the matter — the attempted assassination of two people on British soil, for which there is no alternative conclusion other than that the Russian State was culpable.”

The British Council said it was “profoundly disappointed” at its pending closure. The organization has been operating in Russia since the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union.

“It is our view that when political or diplomatic relations become difficult, cultural relations and educational opportunities are vital to maintain on-going dialogue between people and institutions,” it said.

The Russian statement said the government could take further measures if Britain makes any more “unfriendly” moves.

Britain’s National Security Council will meet early next week to consider the next steps, May said.

Western powers see the nerve-agent attack as the latest sign of alleged Russian meddling abroad. The tensions threaten to overshadow Putin’s expected re-election Sunday for another six-year presidential term.

The poisoning has plunged Britain and Russia into a war of recrimination and blame.

British Ambassador Laurie Bristow, who was summoned the Foreign Ministry in Moscow on Saturday to be informed of the moves, said the poisoning was an attack on “the international rules-based system on which all countries, including Russia, depend for their safety and security.”

“This crisis has arisen as a result of an appalling attack in the United Kingdom, the attempted murder of two people, using a chemical weapon developed in Russia and not declared by Russia at the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, as Russia was and is obliged to do under the Chemical Weapons Convention,” he added.

But Russian lawmaker Konstantin Kosachev blamed Britain for the escalating tensions.

“We have not raised any tensions in our relations, it was the decision by the British side without evidence,” he told The Associated Press.

Kosachev, who heads the foreign affairs committee in the upper house of the Russian parliament, said “I believe sooner or later we will learn the truth and this truth will be definitely very unpleasant for the prime minister of the United Kingdom.”

Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova denied that Russia or the Soviet Union had ever developed Novichok, the class of nerve agent Britain says was used to poison the Skripals.

A Russian scientist disclosed details of a secret program to manufacture the military-grade nerve agents in the 1990s, and later published the formula. But Russia maintains it has never made them.

In a tweet Saturday, Swedish Foreign Minister Margot Wallstrom rejected a Russian suggestion that the nerve agent came from her country.

“Forcefully reject unacceptable and unfounded allegation by Russian MFA spokesperson that nerve agent used in Salisbury might originate in Sweden. Russia should answer UK questions instead,” she tweeted.

Speaking on Russia-24 television, Zakharova on Saturday linked Britain’s angry reaction to the war in Syria. She said Britain is taking a tough line because of frustration at recent advances of Russian-backed Syrian government forces against Western-backed rebels.

Russia argues it has turned the tide of the international fight against Islamic State extremists by lending military backing to Syria’s government. With Russian help, Syrian forces have stepped up their offensive on rebel-held areas in recent days, leaving many dead.

British police appealed Saturday for witnesses who can help investigators reconstruct the Skripals’ movements in the crucial hours before they were found unconscious.

New tensions have also surfaced over the death Monday of a London-based Russian businessman, Nikolai Glushkov. British police said Friday that he died from compression to the neck and opened a murder investigation.

Russia also suspects foul play in Glushkov’s death and opened its own inquiry Friday.

British police said there is no apparent link between the attack on Glushkov and the poisoning of the Skripals, but both have raised alarm in the West at a time when Russia is increasingly assertive on the global stage and is facing investigations over alleged interference in the Donald Trump’s 2016 election as U.S. president.

We Need Dirty Harry

He would not have hesitated. There would be no going back for bulletproof vests or better weapons, waiting for SWAT or following police protocol to protect themselves first. Whether a school building or movie theater, a riot or any situation in which every second lost could mean another child lost, he would take the risk of entering. Risking his life to save others was doing his job. With lives at stake, he never waited for backup. He did his job.

And on Feb. 14, at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida, he would not have squatted outside in safety while shots were being fired or ordered police to stay 500 feet away and not enter. He would not have endured 11 minutes of shooting before entering, allowing the slaughter of 17 people, plus serious injuries to at least 14 others. He would have confronted the shooter and cried out, “Over here, punk. Do you feel lucky?”

At Virginia Tech, he would have rushed in, and the death toll would not have been 32. At Columbine High School, he would have entered with a gun in one hand while using the other to sip from his cup of morning coffee. He would have entered the swirl of the Rodney King riots in downtown Los Angeles and saved that poor driver being beaten on the ground. In all cases, he would have come out the hero, muttering something about his day being made.

How did he come to exist? In the ’50s, cops were seen as people who could be depended upon to take risks to save your life. But in the revolutionary ’60s, they became political fallouts, “pigs,” tools of “fascist” leaders. As the love-ins went on, so did race riots, and crime was growing. As the ’60s ended, various police overreactions to peace marches—culminating at Kent State University in Ohio in l970—left people wondering whether the police were now political tools who could be turned loose on civilians by right-wing politicians.

In the ’70s, hippies became yuppies concerned with security from growing crime rates. The feeling now was that the police were not doing their jobs well enough and were too involved in protecting their own and polishing their self image. In 1971, police Detective Joseph Wambaugh published his first in a series of police books, many made into movies that presented a humanizing and somewhat sad view of police officers struggling to make pension and overcome personal problems, spending time at doughnut shops and calming domestic disputes.

But the same year, a script originally titled “Dead Right,” written by Julian and Rita Fink and finessed by macho screenwriter John Milius, hit the big screens. Now called “Dirty Harry,” it was supposed to star Frank Sinatra, be directed by Irvin Kershner and be set in New York City. Then Don Siegel took over as director. Sinatra pulled out, citing problems with his hand, which he broke while filming “The Manchurian Candidate.” John Wayne was considered as his replacement but was deemed too old. Steve McQueen and Paul Newman rejected the role for various reasons.

The title role was next offered to Clint Eastwood, and the rest, as they say, is history. Eastwood demanded that the locale be changed to San Francisco, his hometown. Scorpio, the film’s serial killer, was based on the Zodiac Killer, who was still on the prowl in San Francisco (he was never caught). Audie Murphy, the ultimate World War II hero, was offered the role of Scorpio, but he died in an airplane crash before deciding whether to take it. The part went to Andy Robinson.

And so, in 1971, the public picked as its newest hero a no-nonsense cop—inspector Harry Callahan, who never shied away from a shootout or hesitated to risk his life. He was an example of the pendulum swung to the other end; a case of maybe going too far, but audiences loved it. If police protocol was in his way, he ignored it, despite threats from his superiors. It was perhaps the best of Eastwood’s characters and the most dynamic screen savior equipped with quips since Sean Connery said, “Bond, James Bond.” The “Dirty Harry” movies dominated for more than a decade and have left an indelible imprint on American culture.

Callahan was like the police robot in “The Day the Earth Stood Still.” If you saw him walking down the street, you would probably get out of his way, but if your life was in danger from some armed men, you could count on him. Back then, if you were a hostage in a bank robbery, you thought someone might actually save you.

But today, when “to protect and serve” means protect and serve the police first and the public second, one might wonder: Where have you gone, Inspector Callahan? A nation turns its fearful eyes to you.

Harry wasn’t there on April 29, l992, during the Rodney King riots, which took place after a predominately white jury acquitted four police officers accused in the videotaped beating of black motorist Rodney King. Thousands took part in a four-day spree involving looting, assault, arson and murder. By the time the police, Marine Corps and National Guard restored order, there was nearly $1 billion in destruction, 55 deaths, 2,383 injuries, more than 7,000 fires and 3,100 businesses damaged. Notable during these four days of terror, however, was not so much the actions of the culprits, but the lack of police actions. No cops went into the flare-up after tempers exploded. No one protected victims inside police roadblocks. Police Chief Daryl Gates imitated the Roman emperor Nero, fiddling while his city burned.

Reginald Denny, a white truck driver, was pulled out of his vehicle at the intersection of Florence and South Normandie avenues and beaten by a mob of black gang members. News helicopters recorded the blow-by-blows, including concrete smashed on Denny’s temple while he was unconscious on the ground. Everyone watching on TV had the same response—where were the police? Rather than trying to stop this near murder in progress, they huddled out of harm’s way, reflecting a policy that protected their safety before any civilian’s. Ultimately, Dirty Harrys arrived, although none of them carried a badge—they were black neighbors who, seeing the assault live on television, came to the rescue. They risked being attacked by a frenzied mob and picked up Denny and took him to the hospital. Other non-black motorists were beaten by the same gang members, but no police officers had the nerve to intervene.

Just minutes after Denny was rescued, Fidel Lopez, a Guatemalan immigrant, was pulled from his truck and robbed at the same intersection. A rioter smashed his forehead open with a car stereo, while another tried to slice his ear off. After Lopez blacked out, the crowd spray-painted his body black. No police officer came to his aid.

No cop got in his car, crashed the barricade, drove to the site of the beatings, pulled out his Smith and Wesson Model 29 .44 Magnum and asked the gang members whether they felt lucky that day.

Seven years later, on April 20, l999, two students—Eric Harris and Dylan Klebod—entered Columbine High School in Jefferson County, Colo., to carry out a shooting massacre, killing 12 students and a teacher and wounding 24 other people before committing suicide. After a failed attempt to blow up the school cafeteria, they entered the school’s west entrance and began firing around 11:20 a.m.—outside at students on a grassy knoll and a soccer field, as well as inside the school. A deputy sheriff arrived and fired back but did not go in. Instead, he radioed for assistance. Dirty Harry also might have radioed, but he would have gone in and ended it before help arrived.

By 11:30 a.m., several deputy sheriffs and police officers arrived. They helped evacuate students; one even saw a shooter pass by a window. Law enforcement, fearing booby traps and setups, chose not go in, despite knowing that the shooting was continuing and aimed at students needing rescue. Police safety came before that of students who were brought up watching Alan Ladd movies that led them to believe police would risk their lives to protect them. A SWAT team arrived by noon but did not enter until about 2:30 p.m. It wasn’t until 3:25 p.m. that the SWAT team finally made it into the school library. By then, the shooting had long since stopped, with the self-execution of the killers. Earlier, coach Dave Sanders had posted a sign on a window: “I AM BLEEDING TO DEATH.” It was ignored. Sanders died nearly three hours later from blood loss, surrounded by about 30 terrified students. His last words were reported by a student to be “tell my family I love them.”

Inspector Harry Callahan would have finished it moments after it started. The death toll would have been limited. A coach might be alive. Who are we to protect if not our youth?

And then, in yet another April, this one in 2007, the 16th to be exact, a sociopathic student, Seung-Hui Cho, wanting to please his gods—the Columbine killers—and seek revenge on those who belittled him, killed 32 people at Virginia Tech. The first two killings occurred around 7:15 a.m. in a dorm building. The police arrived, determined it was an isolated event and treated it that way. Nice theory. But what if they were wrong? On what evidence could the investigators conclude beyond the shadow of a doubt that no killer was still on scene, stalking other students? With kids at stake, how do you not consider and protect against worst-case scenarios? It is not as though madmen haven’t gone berserk in schools, post offices and elsewhere before. Why wasn’t the school evacuated? This was a fresh murder scene. Police should have been left behind; the school should have been searched. If one cop with a true heart had stayed at the scene, dozens of people might still be alive.

As it was, around 9:20 a.m., the killer did return to shoot 30 more people, taking his time between each shot. Some reports say that rather than go in immediately, the police took the time to set up and follow their active-shooter protocols. The school says police cut the chains Cho had put on doors to prevent his victims from exiting and then went right in. I, of course, am not a witness. But it is clear that as the sound of gunshots continued, neither the security guards nor any school personnel took chances that might have saved some lives. Virginia law requires school security guards to complete a police training course. They carry weapons. April 16, 2007, was the day they were hired for. I know a Los Angeles police officer—Richard Blue—who in an earlier career in security (after getting police-training certified) entered a burning building to pull out two people who had been tied up by drug dealers. He considered it the kind of event he had taken the job for.

Sadly, there was no Dirty Harry wannabe in the Virginia Tech security force. And ironically, earlier, Virginia House Bill 1572—intended to prohibit state universities from limiting or abridging the right of a student who possesses a valid concealed-handgun permit from lawfully carrying a concealed handgun—had been introduced by Delegate Todd Gilbert. That proposed legislation, too, is dead.

That is not to say that Virginia Tech did not have its hero, a man who understood what “loco parentis” means. A professor stood at the door and held it closed so his students could climb out the windows to safety. One student tried to get him to come, but he would not budge from blocking the door. Like James Whitmore placing the kids in the sewer tunnel in the 1954 movie “Them,” he died for his heroics. He was an unexpected hero with a past he obviously learned from. Professor Liviu Librescu, 76, was a Holocaust survivor. He was all John Wayne and Clint Eastwood. Here’s to you, Professor Librescu—the public, as Paul Simon wrote, “loves you more than you will ever know. Wo-wo-wo.” Dirty Harry’s badge number 2211 now rests with you.

Talks on $1.3 Trillion Spending Bill Hit Critical Stage

WASHINGTON—Top-level congressional talks on a $1.3 trillion catchall spending bill are reaching a critical stage as negotiators confront immigration, abortion-related issues and a battle over a massive rail project that pits President Donald Trump against his most powerful Democratic adversary.

The bipartisan measure is loaded with political and policy victories for both sides. Republicans and Trump are winning a long-sought budget increase for the Pentagon while Democrats obtain funding for infrastructure, the opioid crisis and a wide swath of domestic programs.

The bill would implement last month’s big budget agreement, providing 10 percent increases for both the Pentagon and domestic agencies when compared with current levels. Coupled with last year’s tax cut measure, it heralds the return of trillion-dollar budget deficits as soon as the budget year starting in October.

While most of the funding issues in the enormous measure have been sorted out, fights involving a number of policy “riders” — so named because they catch a ride on a difficult-to-stop spending bill — continued into the weekend. Among them are GOP-led efforts to add a plan to revive federal subsidies to help the poor cover out-of-pocket costs under President Barack Obama’s health law and to fix a glitch in the recent tax bill that subsidizes grain sales to cooperatives at the expense of for-profit grain companies.

Trump has privately threatened to veto the whole package if a $900 million payment is made on the Hudson River Gateway Project, a priority of top Senate Democrat Chuck Schumer of New York. Trump’s opposition is alarming northeastern Republicans such as Gateway supporter Peter King, R-N.Y., who lobbied Trump on the project at a St. Patrick’s luncheon in the Capitol on Thursday.

The Gateway Project would add an $11 billion rail tunnel under the Hudson River to complement deteriorating, century-old tunnels that are at risk of closing in a few years. It enjoys bipartisan support among key Appropriations panel negotiators on the omnibus measure who want to get the expensive project on track while their coffers are flush with money.

Most House Republicans voted to kill the funding in a tally last year, however, preferring to see the money spread to a greater number of districts.

“Obviously, if we’re doing a huge earmark … it’s troubling,” said Rep. Mark Meadows, R-N.C., a leader of House conservatives. “Why would we do that? Schumer’s pet project and we pass that under a Republican-controlled Senate, House and White House?”

Schumer has kept a low profile, avoiding stoking a battle with the unpredictable Trump.

There’s also a continuing battle over Trump’s long-promised U.S.-Mexico border wall. While Trump traveled to California on Tuesday to inspect prototypes for the wall, what’s pending now is $1.6 billion for earlier designs involving sections in Texas that double as levees and 14 miles (23 kilometers) of replacement fencing in San Diego.

It appears Democrats may be willing to accept wall funding, but they are battling hard against Trump’s demands for big increases for immigration agents and detention beds they fear would enable wide-scale roundups of immigrants illegally living in the U.S.

Meanwhile, a White House trial balloon to trade additional years of wall funding for a temporary reprieve for immigrants brought to the country illegally as children — commonly called “Dreamers” — landed with a thud last week.

Republicans are holding firm against a provision by Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., designed to make sure that Planned Parenthood, intensely disliked by anti-abortion Republicans, receives a lion’s share of federal family planning grants.

But another abortion-related provision — backed by House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis. — that would strengthen “conscience protection” for health care providers that refuse to provide abortions remained unresolved heading into the final round of talks, though Democrats opposing it have prevailed in the past.

Chances for an effort to attach legislation to permit states to require out-of-state online retailers to collect sales taxes appear to be fading. And Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., faces strong opposition from Democrats on a change to campaign finance laws to give party committees like the National Republican Senate Committee the freedom to work more closely with their candidates and ease limits to permit them to funnel more money to the most competitive races.

One item that appears likely to catch a ride on the must-pass measure is a package of telecommunications bills, including a measure to free up airwaves for wireless users in anticipation of new 5G technology.

Mueller Reportedly Receives Notes of Fired FBI Official

Truthdig update: The Associated Press reported Saturday evening that Andrew McCabe’s notes had been “provided to the special counsel’s office and are similar to the notes compiled by dismissed FBI chief James Comey.” It added: “McCabe’s memos include details of his own interactions with the president, according to a person with direct knowledge of the situation who wasn’t authorized to discuss the notes publicly and spoke on condition of anonymity. They also recount different conversations he had with Comey, who kept notes on meetings with [President] Trump that unnerved him.”

WASHINGTON—Andrew McCabe, the onetime FBI deputy director long scorned by President Trump and just fired by the attorney general, kept personal memos regarding Trump that are similar to the notes compiled by dismissed FBI chief James Comey detailing interactions with him, The Associated Press has learned.

It was not immediately clear whether any of McCabe’s memos have been turned over to special counsel Robert Mueller, whose criminal investigation is examining Trump campaign ties to Russia and possible obstruction of justice, or been requested by Mueller.

McCabe’s memos include details of interactions with the president, among other topics, according to a person with direct knowledge of the situation who wasn’t authorized to discuss the memos publicly and spoke on condition of anonymity.

The disclosure Saturday came hours after Trump called McCabe’s firing by Attorney General Jeff Sessions as “a great day for Democracy.” Sessions, acting on the recommendation on the recommendation of FBI disciplinary officials, acted two days before McCabe’s scheduled retirement date.

McCabe suggested the move was part of the Trump administration’s “war on the FBI.” Trump tweeted in praise of Sessions’ announcement Friday night, asserting without elaboration that McCabe “knew all about the lies and corruption going on at the highest levels off the FBI!”

Later, Trump claimed there was “tremendous leaking, lying and corruption” atop the FBI, and departments of State of Justice, but offered no evidence.

An upcoming inspector general’s report is expected to conclude that McCabe, a Comey confidant, authorized the release of information to the media and was not forthcoming with the watchdog office as it examined the bureau’s handling of the Hillary Clinton email investigation.

“The FBI expects every employee to adhere to the highest standards of honesty, integrity, and accountability,” Sessions said in a statement.

McCabe said his credibility had been attacked as “part of a larger effort not just to slander me personally” but also the FBI and law enforcement.

“It is part of this administration’s ongoing war on the FBI and the efforts of the special counsel investigation, which continue to this day,” he added, referring to Robert Mueller’s probe into potential coordination between Russia and the Trump campaign. “Their persistence in this campaign only highlights the importance of the special counsel’s work.”

Trump’s personal lawyer, John Dowd, cited the “brilliant and courageous example” by Sessions and the FBI’s Office of Professional Responsibility and said in a statement Saturday that the No. 2 Justice Department official, Rod Rosenstein, should “bring an end” to the Russia investigation “manufactured” by Comey.

Dowd told the AP that he neither was calling on Rosenstein, the deputy attorney government overseeing Mueller’s inquiry, to fire the special counsel immediately nor had discussed with Rosenstein the idea of dismissing Mueller or ending the probe.

McCabe asserted he was singled out because of the “role I played, the actions I took, and the events I witnessed in the aftermath” of Comey’s firing last May. McCabe became acting director after that and assumed direct oversight of the FBI’s investigation into the Trump campaign.

Mueller is investigating whether Trump’s actions, including Comey’s ouster, constitute obstruction of justice. McCabe could be an important witness.

Trump, in a Tweet early Saturday, said McCabe’s firing was “a great day for the hard working men and women of the FBI — A great day for Democracy.” He said “Sanctimonious James Comey,” as McCabe’s boss, made McCabe “look like a choirboy.”

McCabe said the release of the findings against him was accelerated after he told congressional officials that he could corroborate Comey’s accounts of Comey’s conversations with the president.

McCabe spent more than 20 years as a career FBI official and played key roles in some of the bureau’s most recent significant investigations. Trump repeatedly condemned him over the past year as emblematic of an FBI leadership he contends is biased against his administration.

McCabe had been on leave from the FBI since January, when he abruptly left the deputy director position. He had planned to retire on Sunday, and the dismissal probably jeopardizes his ability to collect his full pension benefits. His removal could add to the turmoil that has enveloped the FBI since Comey’s firing and as the FBI continues its Trump campaign investigation that the White House has dismissed as a hoax.

The firing arises from an inspector general review into how the FBI handled the Clinton email investigation. That inquiry focused not only on specific decisions made by FBI leadership but also on news media leaks.

McCabe came under scrutiny over an October 2016 news report that revealed differing approaches within the FBI and Justice Department over how aggressively the Clinton Foundation should be investigated. The watchdog office has concluded that McCabe authorized FBI officials to speak to a Wall Street Journal reporter for that story and that McCabe had not been forthcoming with investigators. McCabe denies it.

In his statement, McCabe said he had the authority to share information with journalists through the public affairs office, a practice he said was common and continued under the current FBI director, Christopher Wray. McCabe said he honestly answered questions about whom he had spoken to and when, and that when he thought his answers were misunderstood, he contacted investigators to correct them.

The media outreach came at a time when McCabe said he was facing public accusations of partisanship and followed reports that his wife, during a run for the state Senate in Virginia, had received campaign contributions from a Clinton ally. McCabe suggested in his statement that he was trying to “set the record straight” about the FBI’s independence against the background of those allegations.

With the FBI disciplinarians recommending the firing, Justice Department leaders were in a difficult situation. Sessions, whose job status has for months appeared shaky under his own blistering criticism from Trump, risked inflaming the White House if he decided against firing McCabe. But a decision to dismiss McCabe days before his retirement nonetheless carried the risk of angering his rank-and-file supporters at the FBI.

McCabe became entangled in presidential politics in 2016 when it was revealed that his wife, during her unsuccessful legislative run, received campaign contributions from the political action committee of then-Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a longtime Clinton friend. The FBI has said McCabe received the necessary ethics approval about his wife’s candidacy and was not supervising the Clinton investigation at the time.

But Trump pounded away on Twitter Saturday: “How many hundreds of thousands of dollars was given to wife’s campaign by Crooked H friend, Terry M … How many lies? How many leaks? Comey knew it all, and much more!”

Greg Campbell: Bearing Witness to the Hell of War (Audio and Transcript)

In this week’s episode of “Scheer Intelligence,” host and Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer welcomes Greg Campbell, a journalist and filmmaker whose articles have appeared in The Atlantic and The Economist, and whose books include “Blood Diamonds” and “Pot, Inc.”

Campbell and Scheer discuss “Hondros,” Campbell’s 2017 documentary about his friend Chris Hondros, whose photos captured the consequences of war up close. Hondros died in a mortar attack in Libya in 2011.

During their discussion, Campbell tells Scheer that Hondros believed his job was to convey to Americans what was happening overseas in their name. They talk about Hondros’ famous photograph of a little girl covered in blood after her family was killed by American soldiers in Iraq and her appearance as a young woman in the documentary.

Campbell also shares how both crowdfunding and actress Jamie Lee Curtis played integral parts in getting the film made.

Listen to the interview in the player above and see the full transcript below. Find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

—Posted by Eric Ortiz

RS: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where hopefully the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case, it’s Greg Campbell, a writer, a journalist, and now a film director, at least in the last four, five years. He’s been making a film about his childhood friend who went on to become an internationally known news photographer in Kosovo, in Iraq, Afghanistan, and finally died in covering the war in Libya. And that was in 2011. Hondros is the name of the film, and it reminded me so much of why I–the negative side for me as well as, of course, the positive in learning, but the scary side. I didn’t have extensive coverage of war, but I remember the first time I went to Vietnam and, you know, found myself in the middle of a firefight, and actually lost control of some of my bodily functions. And people told me, soldiers and journalists who were out there, you know, that was sort of normal. I mean, it gets really crazy and scary. And of course in the film Hondros, about Chris Hondros, he ends up giving his life, as many journalists have done. But the photojournalists are a particular breed, and your film captures that around this very significant photographer. The courage–you have a compelling scene at the beginning of the movie, or very early on, where he gets his, probably his most famous photograph of someone on a bridge in Liberia. And it becomes world known; what does that, what does it show? Is it the–it’s a young soldier, it’s a rebel; is he scared, is he empowered? And that sort of put Chris Hondros on the map as one of the great combat photographers, is that not the case?

GC: Yeah, that’s exactly right. Chris had been working in difficult regions in Africa and the Middle East prior to that photograph becoming so popular. And it was that that really sort of put him on the map and brought him to the attention, to the upper stratospheres of his profession, where he always sought to be. I was in close touch with him when he was covering that conflict in the summer of 2003 in Liberia, and it was an extremely dangerous situation. Because the capital city was surrounded by rebel soldiers, and those rebel soldiers were getting closer and closer, and the noose was tightening around the city center, which of course was filled with civilians. And they were being targeted with indiscriminate fire from mortars and from, of course, small arms fire. And it was extremely dangerous, because Chris and the other photographers who chose to stick it out in that environment were, of course, susceptible to death or injury, just as the people that they were covering. And I spoke to Chris on the phone when he was weighing the option of perhaps evacuating, taking up the invitation by the U.S. Marines at the nearby embassy to evacuate any journalists who wanted to leave. And he said there were two things going sort of through his mind, and one was that he didn’t feel that it was fair to leave the people behind who couldn’t stay without somebody witnessing what they were going through. And the second was sort of a decision that he made, that he’d spent so much time and energy arriving to this place to do this work that he felt was important to do, that it just, he didn’t feel like it was being true to his own goals to evacuate when it really became hairy and really harrowing. So this image that you’re talking about was on the very middle of a hotly contested bridge, and the encroaching forces were on the far side of the bridge, and Chris was with the government forces on his side. And he had an epiphany that if he was going to cover this war the way that he felt it needed to be covered, he needed to be right in the midst of it. So when the soldiers charged the bridge and launched an attack on the opposing forces on the other side, he was right there with them, and vulnerable to the incoming fire. And he took a photograph, which you’ll see in the film is stunning in its sort of duplicity; it shows you the violence and the chaos, of course, of that particular moment, but it also shows one of the paradoxical things about being in a war, which is the exhilaration that can come from it.

RS: But you also see fear in his face, and you can interpret that shot, that photo, any which way you want. I mean, either it’s a terrified young man or it’s an exuberant young man, and maybe all those emotions are in there, in the thrill of battle and the fear of battle. But let me say something about your film and you, first of all, by way of introduction. This is your only film; I mean, you’ve done some other shorts and so forth, but you’re basically a print person; you’ve edited the Boulder magazine, and so forth. And you guys met in, what, a freshman high school English class. And you were making sort of a home video movie, and were sort of play at war, right?

GC: Yeah.

RS: Yeah, playing at war. And what I liked about the film, I have some criticisms that I’ll get to, but what I very much liked about the film is we see a guy who really is quite exceptional, Chris Hondros. And he learns–I mean, it’s not the kid playing war games–the power of his photography, and the important thing of his witness; he witnesses the carnage, the suffering. Just to mention another one of his iconic photographs, maybe the best one that’s in the film, one of the most powerful, is when a car of civilians is shot up by Americans in Iraq, and they were not a threat to anybody. And suddenly there’s this young woman and her parents are dead, have been shot in the car. And then what I thought was very powerful in your film is you didn’t leave it there; you found that young woman later, you interviewed her. And she was–you know, no, she wasn’t forgiving, and she didn’t understand why this happened; she was angry. And she thought the Americans were monsters for killing her family. And this was years later, and she’s obviously a very thoughtful person, but she wasn’t going to say, oh, “stuff happens in war,” or “collateral damage”–no. No, she said, you folks are the devil, the Americans, and you visited the carnage of the devil upon us in Iraq, and I’m not going to forgive, and you killed my family. That was very powerful in the film. You went and found the woman that was the subject of what is probably his most famous photo, isn’t it?

GC: Yeah, I would agree with that, I think that’s definitely his most famous photograph, and it’s certainly the one that I think resonated the most from his extensive coverage of the war in Iraq, the one that really reached the American public. And we didn’t know what she was going to say when we interviewed her, and in fact we figured there was probably an even chance that she would not want to be interviewed at all. And we approached her at a difficult time in Iraq’s history, the summer of 2014, which was when ISIS had first come on the world stage and seized control of Iraq’s second-largest city, Mosul, which is where she lived. And we weren’t sure if she was within the city limits still, or if she was alive, or where she may have been, if she had fled. So my crew and I took about three weeks on the ground in Iraq to finally locate her. And you know, as you saw and commented upon, we gave her the opportunity to speak if she wanted it, and she had quite a bit to say.

RS: That scene is worth the price of admission, I mean, worth your movie; that one interview you have, for my money, is where you capture the real horror of war, particularly a war that is very difficult to justify.

GC: Yeah.

RS: I mean, the movie does not examine whether any of these wars are needed or not, but the subtext really is that this is unnecessary violence. I mean, in every instance you describe, you really don’t offer a plausible explanation of why we’re there, or why there’s a civil war, or why one part of a community is killing another part. And you know, I think if the movie, it didn’t set out to do it, but I think the movie begs the question of, did any of this have to happen. And your interview with that woman, young, now she’s older, she was what, about four or something when her family was killed right before her eyes.

GC: Yeah, she was five years old.

RS: Five years old. And the American sergeant who orders the firing and so forth, he’s really contrite later in life; you have an interview with him and so forth. Very much liked the scene, by the way, that Chelsea Manning revealed and got her sent to jail, of shooting up a car, that had Reuters photographers and other civilians there in Iraq. And I must say, in that scene, the question that she raises is, it’s not just you make mistakes, you Americans; it’s not just that you came here and messed us up; she is suggesting that we are actually evil in our indifference, our contempt, our use of violence. And you know the fact is, we are responsible for about half of the weapons in the world; we have been the, and Martin Luther King pointed out just shortly before he died, around Vietnam, “We are the major purveyor of violence in the world today,” he said. And you know, a lot of this carnage that you describe in your film is something that we bear a significant, if not always major, responsibility for. And so what your, that woman–I mean, it just got me, that scene.

GC: Yeah.

RS: Where she just lays it out. You know? Who are you–and I’ll never forget the words, do you remember the exact words she–she uses something like “evil” or “monster”–

GC: Oh, yeah. She said if the person offering the apology was in front of her, she would want to drink their blood. And that even if they had drunk every drop, she still wouldn’t be satisfied.

RS: That is an incredible–I mean, what did you think when she said it? Because she’s such an appealing person, you know, as a–

GC: She’s very strong, yeah–

RS: And the–sorry, just for people who haven’t seen the movie, and they should see the movie–when her parents are killed before her eyes, you know, she’s just this pathetic child, and you feel for her. But she comes back in your film as, you know, a full-grown woman with ideas and anger. And it’s not that she’s a crazy person; she’s laying it out the way she sees it. And yeah, that scene, when she says even if I drank the blood of the people–and we meet one of the people who did it, right, in your film.

GC: Yes.

RS: You know, so set that stage, because I do think it’s really incredibly powerful.