Chris Hedges's Blog, page 608

April 21, 2018

World’s Oldest Known Person Dies at 117

TOKYO—The world’s oldest person, a 117-year-old Japanese woman, has died.

Nabi Tajima died of old age in a hospital Saturday evening in the town of Kikai in southern Japan, town official Susumu Yoshiyuki confirmed. She had been hospitalized since January.

Tajima, born on Aug. 4, 1900, was the last known person born in the 19th century. She raised seven sons and two daughters and reportedly had more than 160 descendants, including great-great-great grandchildren. Her town of Kikai is a small island of about 7,000 people halfway between Okinawa and Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s four main islands.

She became the world’s oldest person seven months ago after the death in September of Violet Brown in Jamaica, also at the age of 117. Video shown on Japanese television showed Tajima moving her hands to the beat of music played on traditional Japanese instruments at a ceremony to mark the achievement.

The U.S.-based Gerontology Research Group says that another Japanese woman, Chiyo Miyako, is now the world’s oldest person in its records. Miyako lives south of Tokyo in Kanagawa prefecture, and is due to turn 117 in 10 days.

Guinness World Records certified 112-year-old Masazo Nonaka of northern Japan as the world’s oldest man earlier this month, and was planning to recognize Tajima as the world’s oldest person.

Jessica Hagedorn’s Love Letter to 1970s San Francisco Comes to Stage

Filipina author Jessica Hagedorn may be best known for novels like “Toxicology,” “The Gangster of Love” and “Dogeaters,” but this versatile writer is also no stranger to the stage. In 2016, she transformed “Dogeaters,” winner of an American Book Award in 1990, into a dramatic production for San Francisco’s Magic Theatre. Following that work, set in Manila during the 1980s, Hagedorn turned another tale drawn from her background into a play.

This time, she has adapted “The Gangster of Love,” an autobiographical novel about Raquel “Rocky” Rivera and her eccentric family leaving the Philippines for San Francisco in the ’70s. Like Rocky, a 14-year-old Hagedorn had made that same journey to the Bay Area after her parents split up. The show plays through May 8 at San Francisco’s Magic Theatre, known for cultivating writers such as Pulitzer Prize winner Sam Shepard.

In San Francisco, Hagedorn began taking more seriously the writing she had cultivated in childhood. After a family doctor took an interest in Hagedorn’s poems and sent them to an editor friend, her work made its way to the poet Kenneth Rexroth, who became her mentor. Through Rexroth, Hagedorn was introduced to the city’s thriving poetry scene.

Hagedorn, who has taught in the graduate playwriting program at the Yale School of Drama and at creative writing MFA programs at New York University and Columbia University, spoke to Truthdig recently from New York, where she now lives. Over the course of the interview, Hagedorn touched on how Rexroth’s regard for her talent changed her life, how “The Gangster of Love” is a kind of love letter to a city that’s mostly gone, and how the word “interesting” can mean anything.

Emily Wilson: You decided early on to be a writer. Why was that something you wanted to do?

Jessica Hagedorn: Even when I was very little and couldn’t really read, I loved books and listening to stories. Some members of my family were very emotive storytellers, shall we say. It was very much a part of my childhood; we didn’t have television in Manila till I was 10 or 11, and I think it was one of best childhoods because of that. I had to rely on my own imagination.

Also, the radio was a very important part of my life, not just for music but for the radio dramas. When I was growing up, I used to love listening to them. Friday nights especially—they had one that was ghost stories. It would scare the daylights out of me and really made my imagination explode to imagine these creatures of the night.

Both my parents were readers, and my grandfather was a big reader, so books were around the house. I became a voracious reader even as a very young child, and if you asked me what I wanted for my birthday or Christmas, it would be books. I devoured them, and I wanted to become a writer because I loved books so much, and I loved the idea of inventing a story.

EW: What did you think about San Francisco when you first came here?

JH: I was pretty much in a state of shock. I was upset about being away from friends and my cousins and everybody I knew was not there. You could have dropped me in Paris, and it would have been the same. I didn’t think oh, I hate this place. It was interesting to me; things are always interesting to me. I was also going through a lot of turmoil, and I just moved forward.

As a young female person who did not have a lot of freedom in the Philippines where it was pretty rigid and young daughters were not allowed to just roam the streets, I thought well, here my mother can’t keep me on a leash. I had to get to school on public transportation and explore, so there was a sense of adventure and also of great sadness. It certainly helped that there was a lot going on culturally at the time. I was a big fan of things I couldn’t go to in Manila, so the idea I could go see a play or a concert easily fed me. It was very exciting and new, and I certainly embraced it.

EW: Did you write before you moved to San Francisco?

JH: When I was 8, I would take a piece of paper and fold it over and make a book. Sometimes I would illustrate it like a comic book, other times it was prose and I would say something like, “Once upon a time Emily lived in a cave.” I would always write in a journal, but I didn’t take it seriously then.

EW: Your mom’s friend gave your poetry to Kenneth Rexroth. Did that seem like a big deal at the time?

JH: I didn’t know who he was. It was kind of wonderful. It was our family doctor—a very erudite man, he was very kind to me—who took an interest and probably found it amusing because I took myself so seriously. I showed him my poems, and he said, “Do you mind if I send it to this other person?” who was an editor, I think, at The Wall Street Journal in San Francisco. He sent it to his friend and she, not knowing me at all or my mother, thought it would be a good idea to send it to Kenneth, and he called me up.

I’ve often thought what would have happened if that hadn’t transpired. Kenneth was a huge deal in my life, and when I realized who he was, I realized what an immense gift that was in my life. I just felt so honored and privileged and like, oh, maybe I’m on the right path.

EW: What was your first meeting with him like?

JH: He said something like, ‘I’ve read your poems, and they have promise.” I mean, he wasn’t gushing or anything. I think he called them “interesting.” That’s why I like that word; it can mean anything. He invited my mother and I over for dinner with his daughter. He was very formal and wanted my mother to know he was not just some strange man. He just talked about art and culture, and he was so lovely. I was blown away. I didn’t know half of what he was talking about, but thought, “Oh my God, I’m with an artist.”

After dinner, he took us to City Lights. It was like 9 o’clock, and I said, “Why are we going to a bookstore at this hour?” and he said they were open till midnight. He sort of gave me a tour of San Francisco literati life. We went to Enrico’s and had coffee, and I felt so grown up. His daughter was my age and so erudite, and I was intimidated in the best way. It was great, and I soaked it all up. I think I got happier that night. I felt like, oh, I’m not a weirdo.

EW: When people asked you to adapt “Dogeaters,” you said you didn’t know if it would work as a play because it was so dense. Were you worried about adapting this one?

JH: No, because I learned so much from the experience of adapting “Dogeaters.” I love adapting. I think it’s very challenging, but I love grappling with whose story is this and what do we leave out. I’ve done two, and there’s a third still in progress that I’m adapting by a Filipino-American writer, Lysley Tenorio. It’s from a collection of short stories, “Monstress.”

EW: What did you like about making your novel into a play?

JH: It’s super-fun. You get to reimagine, you get to expand, you get to jump back into something. I never think of my novels as set in stone. I feel like sometimes there’s a character in the background that never got his or her due so you can foreground them a little.

EW: Music seems very important to you. How did it influence you?

JH: I listened to a ton of music, and one of the first places I lived when I moved out of my mother’s flat was with some friends, and one worked at the Fillmore and would sneak me in. I saw blues and rock musicians, and I just ate it up—it was kind of like reading voraciously. As a poet sometimes I’d write to music, and sometimes I’d go against the rhythm. I also had a band when I was young, The Gangster Choir.

EW: What is most exciting about doing “The Gangster of Love” as a play?

JH: I think this novel has resonated with young Filipino-American women in the Bay Area who seem to identify with the story. A lot is set in San Francisco, and it’s my love letter to a city that is gone … well, there are still pockets. But it’s going back to that time and sharing it with an audience, some who are too young to know what that is, but they’re curious. The city shaped me, and so much of what went on in my life, whether it’s poetry or music, was because of the community of fellow artists who were so nurturing of me.

EU to Scrap Tariffs on Mexican Agricultural Products

MEXICO CITY—Mexico and the European Union reached a deal to update their nearly 20-year-old free trade agreement on Saturday, including the elimination of tariffs on a number of Mexican agricultural products.

President Enrique Pena Nieto, who arrived in Hannover, Germany, in the afternoon to begin a five-day tour of three European nations, said via Twitter that the “agreement in principle” was struck in Brussels.

“The modernization of this instrument broadens our markets and consolidates us as priority partners of one of the most important economic blocs in the world,” Pena Nieto said.

The announcement comes amid uncertainty for both Mexican and European commercial ties with the United States under the presidency of Donald Trump, who has espoused a more protectionist stance on trade.

Mexico is in ongoing talks with the United States and Canada on overhauling the North American Free Trade Agreement. About three-quarters of Mexico’s exports go to the United States, and roughly half its imports come from there.

A joint statement from Mexico’s Foreign Relations and Economy departments said that under the agreement with the EU, tariffs will be scrapped on Mexican orange juice, tuna, honey, agave syrup, fruits and vegetables, among other products.

Also addressed in the deal are services, telecommunications, technology, rules for protecting investments and a mechanism for dispute resolution.

“With the conclusion of this new agreement, Mexico and the European Union send a strong message to the world about the importance of keeping markets open, working together through multilateral channels to confront global challenges and cooperating in benefit of the causes of humanity,” the joint statement read.

It said that since the accord took effect in 1999, trade between Mexico and the European Union has quadrupled and the European bloc accounts for 38 percent of foreign direct investment in Mexico.

American History for Truthdiggers: Flowering or Excess of Democracy? (The 1780s)

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the seventh installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His wartime experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 7 of “American History for Truthdiggers.” / See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6.

* * *

The Brits Are Gone: Now What?

“The evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy. The people do not want virtue, but are the dupes of pretended patriots.” —Elbridge Gerry, delegate to the Constitutional Convention (1787)

It has become, by now, like American scripture. We all know the prevailing myths, history as written by the winners. Virtuous American patriots, having beaten the tyrannical British, set out to frame the most durable republican government in the history of humankind. The crowning achievement came when our Founding Fathers met in Philadelphia in 1787 to draft an American gospel: the Constitution. The war had ended, officially, in 1783.

Have you ever asked yourself why popular versions of America’s founding begin with the Declaration of Independence in 1776, or with the defeat of the British at Yorktown, Va., in 1781, skipping past the black hole of the mid-1780s to the Constitutional Convention of 1787? What happened in those critical intervening years? What is it that remains hidden in plain sight? Who does the prevailing narrative serve?

Well, the discomfiting truth is that over the last 40-odd years most serious historians finally began studying marginalized peoples, such as slaves, Indians and women. It is well that this is so. However, the decision to first draft Articles of Confederation and then, later, to move toward a new constitution and a more centralized federal government—the keys events of the 1780s—was an elite action that mostly benefited the elites. A top-down structure was imposed on an only partly willing citizenry. This sort of story no longer appeals to academic historians busy drafting a “new” history from the “bottom up.”

From grade school through university survey courses, we are fed the same tale. The victorious colonists—the first generation of Americans—briefly organized under a weak governing framework: the Articles of Confederation. This unwieldy government quickly floundered in an era of stagnation and chaos, to be replaced, wisely, by our current constitution. There is, of course, some truth to this. The Articles of Confederation, the law of the land and America’s first constitution, from 1781 to 1789, did grant precious few powers to the national government. Power was dispersed to the state governments. In a sense, we should probably think of the early 13 states as separate countries, held together in a loose alliance more similar to today’s European Union than our current U.S. nation. Many states did, indeed, suffer under a period of economic stagnation, and there were several agrarian revolts of one sort or another.

However, it behooves us to consider why the revolutionary generation did this, why they chose a weak central government. When thinking about the past, we must avoid determinism and remember that no one in history woke up on a given day and planned to fail, planned to draft an incompetent governing structure. Perhaps the men of the 1780s had good reasons; maybe there was wisdom in such a loose confederation. Was, in fact, the later constitution actually a superior document? This installment in the American History for Truthdiggers series reconsiders that forgotten era, seeks to redeem aspects of the Articles of Confederation and asks inconvenient questions about just how democratic our later constitution would really be.

The Critical Period: Defending the Articles of Confederation

“Each State retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States in Congress assembled.” —Article II of the Articles of Confederation

It had been a brutal, long, destructive war—the longest war the United States fought until Vietnam, two centuries later. Tens of thousands died, infrastructure was damaged, state governments were loaded with debt, and many thousands became refugees. Given this reality, we must consider what lessons American leaders learned from the Revolution. Certainly they feared powerful executives (the Articles would have no president), distant aristocratic legislatures (there would be no House of Lords or upper house in the Continental Congress) and standing armies (the Revolutionary army was demobilized, and state militias would provide for the common defense).

The real work of government was seen as occurring at the state level, and it was the state constitutions that truly mattered. Each state varied, of course, with Maryland’s government being the most conservative and Pennsylvania’s the most democratic and egalitarian—by some measures the most democratic in the world. Most states had learned lessons from the late war: They had weak (or in some cases no) executives, powerful—sometimes unicameral—legislatures, and militias rather than professionalized armies. After all, these were post-revolutionary governments, terrified of tyranny and imbued with common conceptions of classical republicanism.

The opening text of the Articles of Confederation (1777-1789).

The foundation of republicanism was rather simple and had three pillars—liberty, virtue and independence. To have liberty, one need understand that all power corrupts and must, therefore, be checked by virtuous government. Virtue required that representatives always act according to the public interest, and not self-interest. Such virtue was possible only when representatives were independent entities not beholden, economically or otherwise, to others. All too often, this required the possession of some degree of wealth, property and leisure time to study politics.

The problem is that so much of this classical republicanism stood in tension with the democratizing tendencies of all revolutions. In elections for the state legislatures, more men could vote than ever before. Some states, like Pennsylvania, had universal male suffrage and dropped all property requirements for political participation. Common farmers and artisans in the 1780s had increasingly democratic, progressive impulses. They still hated taxation—which had exponentially been increased after 1783 in order to pay off state war debts—and weren’t afraid to use the tried and true tactics of the Revolution to express their dismay. Farmers and laborers of the 1780s were reform-minded and employed methods consistent with the “spirit of ’76”—petitions, boycotts, even armed insurrection—to pressure their new state governments.

The 1780s were a period in which common folk called for the extension of the franchise (voting rights), the abolition of property requirements, and more-equal representation for distant western frontier districts. Indeed, one could argue that this critical period saw a veritable flowering of democratization, at least among white males. This stood in stark contrast to the sometimes overstated image of depression and stagnation commonly depicted by popular historians.

The Articles are so often derided that we forget that there were real accomplishments in this era. After all, the Articles of Confederation was a wartime document and, so governed, the Americans managed to achieve victory over the most powerful empire in the world. This, in itself, was a miraculous accomplishment.

Though there were many problems for the new American republic—which is perhaps best compared to a post-colonial 20th-century African or Asian state—we must dismiss the chaos theory for why the Articles were eventually replaced by the Constitution. Consider, for a moment, all the things that didn’t happen to the new republic in the 1780s. There were no interstate wars, no external invasions, no general rebellion. In fact, in many respects, according to the historian Merrill Jensen, there was a spirit of optimism and a sense of an improving humanity within the new country.

Confederation or Empire: The Northwest Ordinance and the Fate of Native Peoples

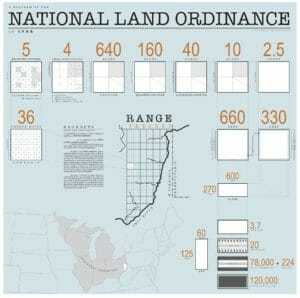

Northwest Land Ordinance diagram (1785).

Another often-forgotten accomplishment of U.S. government under the Articles of Confederation was the passing of the Northwest Ordinance, the plan for the occupation and subdivision of the territories ceded by Britain north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi. Have you ever noticed how when traversing Midwest “flyover country” on a modern airliner the farmland below appears divided into neatly square plots of similar size? For that we have the Northwest Land Ordinance of 1785, passed into law under the Articles, to thank. The new law divided and subdivided the acres of unsettled (at least by Anglo farmers) land into neat squares for future sale and development.

The British had signed over ownership of this territory to the new United States in the Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the War of Independence. They did so, of course, without the permission of or, often, even notifying the land’s actual inhabitants, numerous native peoples. This, as we’ve seen in past installments of this series, was a recipe for trouble. The Indians had no intention of ceding their land simply because certain white men across a vast ocean had signed a few papers.

The land granted to the new United States in the Ohio Country was extraordinarily important to the new government under the Articles. Lacking the power of direct taxation of the people, the Congress expected the sale of these lands to private citizens to earn the government ample income to pay down the national war debt and fund wartime bonds issued during the Revolution. It might have worked, too, if those lands were empty. Unfortunately for the land speculators and would-be pioneers, the various tribes of the region had formed a massive coalition and would fight, hard, for their territory. In fact, in the 1780s and early 1790s, two separate U.S. Army forces were devastatingly defeated by the Ohio Country native confederation. These defeats, and the inability to sell and settle the new lands, helped fuel the depression and fiscal crisis facing the Articles of Confederation-era republic. It was all connected, east with west, domestic with foreign policy.

As a future charter, though, the Northwest Ordinance was profound and shaped the settlement and organization of the ever-expanding United States. The new lands, once settled by a requisite number of farmers, would become federal territories and, eventually, states. This, of course, upset many of the original 13 states, which had long claimed vast tracts to their west. The Ordinance also did something else rather consequential: It outlawed the institution of slavery north of the Ohio River. This reflected growing post-revolutionary sentiment in the Northern states, which would see nearly all their governments gradually outlaw the “peculiar institution” over the two proceeding decades. What the Ordinance now set up, however, was a growing north-south societal divide over the institution of slavery that would eventually play out in the American Civil War.

The Northwest Ordinance, even if it was premature in signing away and organizing highly contested territory, did achieve two things. First, it increased the probability that land speculators and other factions would call for a more centralized government than the Articles could provide. Only a strong federal government, they would argue, could raise, fund and field an army capable of defeating the formidable native confederation in the Ohio Country. Second, the Ordinance ultimately doomed the native peoples inhabiting this fertile land to either conquest and subservience or expulsion. Before the first waves of settlers crossed the Appalachian Mountains, this outcome was nearly inevitable. The new republic’s government had made plans for, divided up and begun to sell off the Indian land without the consent of the native tribes.

Let us remember that when the British and Spanish agreed to cede everything east of the Mississippi River to the new United States they were transferring a vast empire to the American republic. One could argue, then, that the American tension between republic and empire was already in full swing when the Ordinance passed. Furthermore, one of the reasons the stronger future federal constitution appealed to so many Eastern elites was that they knew that a centralized government was now necessary to manage what Thomas Jefferson famously called “an Empire of Liberty.”

Perhaps the truth is a confederation of small republics could never manage an empire unless it had a stronger constitution. As we will see in the next installment, it was under our current Constitution, not the Articles, that we grew into a full empire, one that we retain to this day.

Excesses of Democracy: Elite Responses and Criticisms of the Articles

“I dread more from the licentiousness of the people, than from the bad government of rulers.” —Virginia Congressman Henry Lee Jr. (1787)

Continental dollars, paper currency issued by the wartime Congress (1779).

Not all Americans saw the 1780s as a time of hope, experimentation and increased egalitarianism. For many, especially wealthy, elite citizens, the entire decade, along with the Articles of Confederation that presided over the new republic, was a nightmare. The chief complaints of those who wished to strengthen the federal government were that chaos reigned, the commoners had gained too much confidence and power, and the state legislatures were too beholden to their constituents. The result, as these men—who would become the Framers of the Constitution—saw it, was bad governance.

Finances played a major role. On this subject neither side of the great debate was happy.

Poor and middling sorts were upset that heavily indebted state legislatures were levying taxes many times higher than this class of Americans had had to pay under imperial rule. Most taxes were collected in gold and silver, which few backcountry farmers had access too. These citizens were also aghast at the potential for increased federal taxing power, which, indeed, many elites later proposed.

Creditors, financiers, large landholders and even some genuinely principled republicans saw things differently. In their minds, the Revolution had unleashed a popular torrent of excessive democracy, egalitarianism and a new spirit of “leveling,” or what would today be called premodern socialism. Farmers, artisans and laborers had forgotten their proper place in society and gained too much confidence with respect to their social betters. To the better-off, the Revolution had unintended, not altogether positive, second- and third-order effects. As one New Englander declared in the fall of 1786, “men of sense and property have lost much of their influence by the popular spirit of the law.”

As the eminent historian Gordon Wood has pointed out, we must understand that a majority of the Articles’ most famous critics—and the later constitutional Framers—were basically aristocrats in the pre-industrial, pre-capitalist sense of the word. They feared inflation, paper money and debt relief measures because they modeled their social and economic world on the systems and tendencies of the English gentry. Their entire societal and agrarian order was at risk during the 1780s and, in fact, would later collapse in the increasingly commercial Northern states, only to live on in the plantation life of the antebellum South. Much of their complaint about “excessive democracy” in the new American state governments may ring hollow to modern ears, but they believed in their position most emphatically.

Let us forget what we know about popular government in the 21st century and remember that in the 1780s, especially among the elites, the term “democracy” was still generally used as a pejorative. And, to the Founding elites, it was high time to stuff the democratic genie—unleashed by the spirit of ’76—back in the bottle. By excess democracy, the elites, who would become Federalists in later political parlance, referred specifically to the ability of commoners to pressure popularly elected state legislatures to print paper money and pass debt relief bills. If creditors couldn’t expect prompt repayment in full, they surmised, the social order itself would break down. Many of these elites were themselves creditors or speculators and often were wealthy.

Still, it would be too simple and cynical to ascribe their political beliefs simply to personal, pecuniary interests. Rather, their critique of democracy and the state governments’ policies under the Articles was generally consistent with their particular brand of republican worldview. Liberty and order must be balanced in the American republic, or republics, and, they believed, strict libertarianism had gone too far since the outbreak of revolution. But, were they right? The centralizing elites’ favorite example of unbridled democratic chaos has been passed down in American history under the title Shays’ Rebellion.

The Last Act of the American Revolution: Shays’ Rebellion

“The late rebellion in Massachusetts has given more alarm than I think it should have done. … I hold that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing … as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical. Unsuccessful rebellions, indeed, generally establish the encroachments on the rights of the people which have produced them. … It is a medicine necessary for the sound health of government. …” —Thomas Jefferson, Jan. 30, 1787, writing from Paris in a letter to James Madison, regarding Shays’ Rebellion

Every History 101 textbook presents the same narrative about the fall of the Articles of Confederation and the rise of the infallible Constitution. The “people” got out of hand with all that revolutionary fervor, and in Massachusetts’ Shays’ Rebellion, matters boiled over. In response to the chaos unleashed by these rebels, “respectable” patriots—such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton—decided to find a remedy that balanced liberty and order. The result, of course, was the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

But what if our common understanding of Shays’ Rebellion is incomplete, perhaps even wrong? What if Shays and his Regulators—they did not call themselves rebels—had a point, genuine grievances and a coherent worldview? Since this singular event is given so much weight as the supposed catalyst for the American Constitution, it deserves a closer look.

For starters, we have to review the grievances of many American farmers in the 1780s. Remember that the wartime Continental Congress and individual colonies had to raise money and take on debt in order to fund an eight-year war. Soldiers, when they were paid at all, received paper notes, and merchants, who all too often found their goods requisitioned by the patriots, also received paper currency, essentially IOUs from a broke, fledgling revolutionary government.

After the Peace Treaty of Paris in 1783, the confederation Congress asked (the Articles of Confederation provided no mechanism for direct federal taxation) the 13 states to raise money to pay off federal war bonds and, furthermore, the individual states had to raise enough gold and silver to redeem their own state currencies. The result was state-level taxation that was on average two or three times higher than in the colonial era. This is ironic, given our common understanding of the American Revolution as a revolt against excessive taxes!

The problem is that the mass printing of paper currency, combined with low confidence in Congress’ future ability to pay its debts, led to massive inflation and devaluation of the credit notes. Most creditors and merchants stopped honoring the face value of continental dollars and some would accept only gold or silver specie (of which there was an exceeding shortage in the Revolutionary era). By war’s end, 100 continental dollars often had a market value of less than $1 in hard specie. If a returning veteran wanted to feed or clothe himself, he needed to exchange his paper pay slips for gold or silver. Indeed, in one of the great crimes against American military veterans in this country’s history, poor, desperate discharged soldiers had little choice but to sell off their nearly worthless currency for a pittance in gold or silver.

Such was the case in rural western Massachusetts in 1786. The state government in Boston imposed a high property and poll tax on the farmers and insisted it be paid in hard currency (gold or silver). As noted earlier, most farmers did not have access to such specie. What they did have was land, animals, tools and, perhaps, if they were war veterans, continental paper dollars. If they couldn’t pay in gold, well, then, the local sheriff could seize their land. And, if the sheriff was sympathetic to the farmers and did not enforce the evictions, laws passed by the state government in Boston allowed authorities to seize his property.

What, asked many western Massachusetts farmers—a great number of them war veterans—did we just fight a revolution for? To suffer unreasonable taxation and lose our land to our own state government? The sense of injustice was palpable and, in hindsight, understandable. One such smallholder, named Daniel Shays, became a leader of the disgruntled western farmers and would head what eventually became an armed revolt intent on closing the courts and saving their property.

Shays was a former Continental Army officer, a wounded veteran of the battles of Bunker Hill and Saratoga, who left the Army a pauper. Later taken to court over debts stemming from his time away from his farm, Shays was forced to sell his sword, a gift from the Marquis de Lafayette, to come up with the money. By 1786, he, like many of his compatriots, had nothing left to give when the taxman again came calling.

Almost all the Continental Army veterans had by 1786 sold off their paper currency and war bonds to rich speculators for a fraction of the face value. Now the states, and the federal Congress, imposed taxes to pay either the interest on, or the face value of, the very war bonds the veterans had desperately sold off. It all seemed utterly unjust.

Few of the speculators were veterans. Most possessed fortunes, and a willingness to play the futures market. One of the reasons Shays’ Rebellion occurred in Massachusetts was that the state government in Boston had begun taxing land with the intent to pay off the face value of all state bank notes no later than 1790. Worse still, by 1786, just 35 men—nearly all of whom lived in the state capital, Boston—owned 40 percent of all the bank notes. They stood to make a killing when the tax windfall came in.

After Shays and his Regulators refused to pay the tax, armed themselves, closed several county courts and marched on the federal weapons arsenal at Springfield, the eastern elites panicked. Without a standing federal army, and with the state militia unreliable or sympathetic to Shays’ cause, the Massachusetts governor—himself a large bondholder—enlisted other wealthy creditors to hire a private army to put down the growing rebellion.

There was a remarkable overlap between large holders of bank notes and those who contributed to hiring the mercenary force. One wealthy donor, who contributed $500 in gold for the mercenaries, held as much as $30,000 in unredeemed bank notes. When the private militia eventually was successful in suppressing Shays’ Rebellion, contributions of this kind turned out to be money well spent.

The dividing lines in Shays’ Rebellion were as much regional as class-based. This was a battle between the western hinterland and the hub city of Boston, a political tension that exists in Massachusetts to this day. In many colonies, the farmers had successfully lobbied to move the capitols out of the commercial hub cities—for example, from New York City to Albany and from Philadelphia to Harrisburg, Pa. Massachusetts was the anomaly in that Boston remained both the commercial and political capital of the state.

Shays and his compatriots wanted the capital moved westward, the aristocratic state Senate abolished, and the stipulated $1,000 in assets of prospective gubernatorial candidates to be lowered or eliminated. So, as we can see, this fight was as much about class and region as anything else, and this certainly complicates the narrative.

Shays’ Regulators saw themselves as patriots waging perhaps the final act of the American Revolution. When they were defeated, many “rebels”—including Shays—fled across the border to safe haven in what was then the independent republic of Vermont. This should be unsurprising, since Vermont was itself founded by agrarian “rebels” like Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys, who had clashed with New York state landowners and seceded to form their own country.

Although Shays’ Rebellion was put down, we must take a harder look to determine the local winners and losers. Gov. James Bowdoin and many anti-Shays legislators were soon voted out of office, and debt relief was passed in the next session of the Massachusetts legislature. Shays was pardoned and eventually even received a pension for his Continental Army service. It was the perceived success of the rebels—along with the military impotence that forced creditors to hire a private army—that would have a profound effect on Massachusetts, the elites and the young republic itself.

Shays’ movement was only one of many rebellions or threats of rebellion in the 1780s. Thus, one motive of the Framers of the Constitution was to create a new federal government with the power, funds and professional army capable of suppressing unrest. This was ironic, since the American Revolution had been fought, in part, in opposition to the presence of a standing British army.

The true importance and legacy of Shays’ Rebellion was the fear it struck in the hearts of American elites. Shays’ most prominent critic was one George Washington. Before he read of Shays’ agrarian revolt, Gen. Washington was happily retired at his estate in Virginia. It was his fear of further rebellions—which, according to a favorite analogy, were like snowballs, gathering weight as they rolled along—that convinced Washington to take part in the Philadelphia convention to reform the Articles of Confederation.

In a letter to Henry Lee, Washington expressed his horror regarding the revolt in Massachusetts and, furthermore, revealed his pessimism about the ability of the common man to practice self-government. He wrote:

The accounts which are published of the commotions … exhibit a melancholy proof of what our trans-Atlantic foe has predicted; and of another thing perhaps, which is still more to be regretted, and is yet more unaccountable, that mankind when left to themselves are unfit for their own Government. I am mortified beyond expression when I view the clouds that have spread over the brightest morn that ever dawned upon any Country. …

No doubt Washington believed this, and truly feared for the fate of the new republic. But was he right?

Can we in good conscience say that Shays and his ilk were nefarious rebels or chaotic brigands? Could it not be said that, in a sense, Shays was correct and, in a way, a patriot? If Shays and his men were indeed patriots, then what does that say about the motivations of the wealthy men of substance—including Washington—who later gathered in Philadelphia to rein in what they called “the excesses of democracy”? At least this: that these Framers were rather dissimilar from Daniel Shays and his fellow men at arms; that they did not represent the constituency of farmers and veterans who fought for what Shays certainly believed was their own lives, liberty and happiness.

This is not to say the Articles were not flawed, or to smear the motives of each and every Founder. Rather, a fresh look at Shays’ Rebellion and the elite reactions to it ought to complicate our understanding of who the Framers were and were not, whom they did and did not represent, and what they hoped to achieve in Philadelphia. True histories can omit neither the George Washingtons nor the Daniel Shays of our shared past. The republican experiments of the 1780s and the new constitutional order after 1787 both reflected, to varying degrees, the hopes, dreams and perspectives of Shays’ Regulators and Boston creditors alike. One might even say that America’s ongoing experiment, here in the second decade of this 21st century, still reflects this tension.

* * *

The Road to Philadelphia: From the Spirit of ’76 to a New Constitution

What, then, should we make of the turbulent and critical 1780s? Certainly it was a time of transition, of political and constitutional experimentation in the fledgling republic and within each of the still very independent states.

Maybe this too: While imperfect, life under the Articles was not as tumultuous as most students have been led to believe. Thus, at least to some extent, we must see the establishment of a more centralized system under the 1787 Constitution as the fulfillment of the dreams of more conservative delegates, increasingly tepid revolutionaries—men of wealth, men of “good standing”—not, necessarily, as consistent with the hopes of an American majority.

A new look at the transition from the Articles to the Constitution, which we will take on in the next installment, presents a very different backdrop to the Philadelphia convention. A more thorough understanding of the inspirational, if messy, 1780s helps explain what some historians have argued the Constitutional Convention really was: the counterrevolution of 1787, a repudiation of the “Spirit of ’76.”

As the historian Woody Holton noted, the 1780s deserve attention and remain relevant because “the range of political possibilities was, in numerous ways, greater than it is today.” We must be cautious in how we remember this period, careful not to read history backward from a post-1787 constitutional world, and avoid writing off the Articles of Confederation as somehow doomed to failure.

Political leaders and common folk alike spent the decade after the revolution asking and answering many seminal questions: What sort of nation would the United States be? Would it even be a nation in the modern sense of the word, or instead would be it a collection of states? Should the national government be centralized, federal or essentially nonexistent? An empire or a confederation? Progressive and egalitarian or socially and fiscally conservative?

Elites and commoners, top-down agendas and grass-roots movements—all of these played roles in the 1780s to help define the contours of post-revolutionary America. They, the then living, could hardly know they were deciding, at that moment, which founding myth later generations would revere as American gospel.

As 1786 turned to 1787, the levelers and progressives, it seemed, would lose out, at least for a time. The 1780s and the Articles of Confederation may have represented their high tide of hope, but the pendulum was about to reverse course, moved backward by patriot elites who were intent, in a sense, on a counterrevolution. The Framers, men you know and revere as “democrats”—George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and Benjamin Franklin—would soon craft a document that would curtail what these men actually saw as the “excesses” of democracy in America. This document would soon become their, and our, republican scripture: the U.S. Constitution.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

● James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 8: “Crisis and Constitution, 1776-1789” (2011).

● Alfred Young and Gregory Nobles, “Whose American Revolution Was It? Historians Interpret the Founding” (2011).

● Edward Countryman, “The American Revolution” (1985).

● Gary B. Nash, “The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America” (2005).

● Joseph Ellis, “The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789” (2015).

● Merrill Jensen, “The Articles of Confederation” (1940).

● Woody Holton, “Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution” (2007).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

[The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.]

Starbucks Drama Proves (Again) the Reactionaries Will Be Televised

We are here again. The latest outrage serves as another occasion to gnash our teeth and seethe in collective indignation. This time, it’s the arrest of two “black” men in Philadelphia that is capturing the exasperation of the public. Let me say from the outset that I’m not writing this to, in any way, dismiss the scourge of racism or diminish the distress of being arrested for no reason other than the pigmentation of one’s skin.

I understand intimately the resentment that is stirred when the rights and liberties of people are trespassed against. However, these protests have become an end unto themselves. One second, we are up in arms demanding justice, only to forget the next minute. In the rush to condemn iniquities, we keep forgetting the root of our tribulation. We are missing the bigger picture as we rush to react. Injustice hunting has become the new favorite pastime of Americans.

People in Flint are poisoned, and we take to social media to bleed our spleens only for anger to be followed up with inertia. The water sources of Native Americans in the Dakotas—and in countless communities throughout America—get polluted and we jump to demonstrate only for passions to abate as soon as the news leads with another indignity. Yet another nation in this never ending war of terror gets shelled into the stone ages, and we appeal on behalf of humanity only to retreat once the images of death and carnage are no longer splashed on our iPhones.

Henry David Thoreau once said, “There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root.” He was referring to the way too many are quick to address symptoms of injustice while few tend to the disease. We have become a society of branch hackers. We are so easily driven into emotion that few take the time to logically figure a way forward.

The root of almost every issue we keep getting riled up about can be traced to consolidated greed and concentrated power. The pipes in Flint were not replaced by a utility company because politicians and bureaucrats alike chose to err on the side of profits even if that meant poisoning people. The Dakota Access pipelines were built to enhance the revenues of oil corporations. Wars never end because each bomb that explodes overseas fills the coffers of the military-financial complex and the boars who feed at the trough of injustice.

Do you see the common factor here? In each instance, corporatism is the source of human suffering. The public good is being subverted by private interests. Jeff Bezos is worth over $119 billion by last count. Meanwhile, the average worker at Amazon is making $28,446 annually. This is no longer a boss-to-worker relationship. Owner versus slave is a more apt analogy given the discrepancy of realities between the haves and the have nots.

Bezos is not an outlier but the rule when it comes to the fortunes of the 1 percent and the misfortunes foisted upon the rest of us. It was not always like this. During the 1950s, the top marginal tax rate was as high as 91 percent. This was done to ensure a fair distribution of wealth and assure income opportunity for most Americans.

What a change a half century brings. We now live in the age of robber barons and capital vultures. It is now a social norm for billionaires to pay 15 percent or less in taxes while the average worker at Starbucks pays twice as much in terms of tax rate.

In order to distract us from this truth, corporate-owned pundits, politicians and personalities are continually engaging in identity politics and pushing separable grievances. Notice how few people talk about economic injustices for every thousand who hack at the branches of social justice? That is by design. Demagogues incite us and stoke our emotions to prevent us from figuring out a way to end this corporate morass that is choking our planet. A plan of action with only tactics sans strategy delivers zero solutions. People who know only how to react become pawns of those who have a vision.

The gentry’s vision should be pretty evident by now. We have become assets on the balance sheets of corporations. As they automate more and more jobs and replace human hands with artificial intelligence, the working and middle class will soon enough be viewed as liabilities on those same balance sheets. Corporations are a noose around our collective necks. This clear and present threat to humanity cuts across the endless constructs that have been erected to Balkanize people into the ghettos of identities. Now you know why I put quote marks around the word black at the beginning of this article.

Instead of protesting against corporations and outsourcing our freedoms to be arbitrated by the neo-aristocracy, how about we divest from the plutocracy altogether? A thousand marches against Starbucks produce nothing except giving them free advertising as they announce another corporate get-well plan. How about we use our feet not to protest but to reinvest in our communities by walking into a locally owned coffee shop instead of buying overpriced cappuccinos at Starbucks?

Locally owned companies and businesses are a lot less likely to poison their own community since they would be poisoning themselves in the process. Moreover, empowering small and community-based businesses like a locally owned coffee shop is a way of retaining communal wealth and building equity for ourselves and our children.

The same is true of our politics. Instead of voting for yet another duplicitous politician promising change only to deliver broken promises, let us expend that energy to build our communities block by city block. The way to make America great again is not through slogans but through the hard work and sacrifice needed to mend our broken communities.

Or we can continue to protest and rally—and get nothing for our troubles. Memes like “too little, too latte” sound cute, and they capture the attention of social media onlookers, but these hashtag protests lend no value in the ongoing quest to alleviate suffering. We are at once putting shackles at our feet only to demand that the oligarchy free us.

The keys to our liberation reside in our hands. I’m not advocating some “off the grid” existence, either. Incremental changes in our shopping and consumption habits can one day loosen the grip corporations have around our necks.

As long as we continue to empower the same corporations who are nullifying hope globally, we are spinning our wheels. And what’s more, we are contributing to our pillaging—we are rendering ourselves irrelevant by the day.

We can keep acting tactically, or we can finally come up with a strategy. Divest from corporations and invest in our communities. We do not need yet another social media campaign. I’m talking about decisions we make daily with our wallets and our hearts. The choice is simple. The decision we make going forward is crucial.

Amid Climate Change, Company Acts to Keep Chocolate Coming

If you have a sweet tooth, a liking not only for sugar-rich sweets but especially for chocolate, you’ve cause for celebration: the prospect of a climate chocolate threat is a little less likely.

Keeping the world supplied with chocolate is becoming more difficult as deforestation and climate change make it harder for farmers in the tropics to grow the trees that produce the cocoa beans.

Paying producers more for beans under the banner of Fairtrade certainly improved the lot of poor farmers, most of them small-scale cultivators, but that did not solve the long-term problem of providing enough cocoa to supply the huge world market.

The cocoa tree’s natural habitat is the lower storey of the evergreen rainforest, but cocoa farmers do not always grow their trees in the best conditions. The trees only thrive 10 degrees either side of the Equator, where they need sufficient warmth, rainfall, soil fertility and drainage if they are to flourish.

Clearing rainforest to make space for cocoa tree plantations is some farmers’ preferred practice, but it is not a sustainable way to maintain production.

“We pioneered Cocoa Life to address cocoa farm productivity alongside community development. We strive to not only empower cocoa farmers but also to help their communities thrive”

But, fearing that the supply of cocoa beans was in jeopardy and the price of their raw material would affect production, one of the world’s largest manufacturers is now to invest US$400m by 2022 to help 200,000 cocoa farmers secure a long-term future.

The scheme, called Cocoa Life, is helping farmers in six key cocoa-growing countries: Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Indonesia, India, the Dominican Republic and Brazil.

The company responsible, Mondelēz International, which owns brands like Cadbury, Suchard and Milka, believes many cocoa-growing regions could be wiped out unless action is taken.

Cathy Pieters, director of the Cocoa Life programme at Mondelēz, told the Climate News Network: “The challenges in cocoa are becoming more diverse and complex. In fact, some reports show current cocoa-producing regions may no longer be suitable for cocoa production in the next 30 years if we don’t take action.

Expecting change

“Our approach to climate change is deliberate because we expect a change to happen – a transformation. As one of the largest chocolate makers in the world, we are mobilising farmers and their communities to prioritise forest protection.”

Key to the programme is educating farmers, helping women by providing finance and stopping child labour, and also improving the environment. The company is helping farmers prevent further destruction of rainforest and planting trees around cocoa farms to protect them and recreate the habitat in which trees are most productive.

In this way farmers are producing far more cocoa beans from the same area of land. This year the programme has planted more than a million trees to restore the forest canopy.

Cocoa Life was launched in 2012 and to the end of last year had trained more than 68,000 members of the cocoa-farming community in best practice to ensure a sustainable industry. Cocoa saplings and shade trees needed to replicate rainforest conditions had been distributed to 9,600 farmers.

Industry example

The company says that by the end of 2017 it had increased the amount of its cocoa from sustainable sources by 14 percentage points to 35% and reached 120,000 farmers, 31% more than in 2016.

The potential crisis in the cocoa-growing industry and the threat of climate change have led other manufacturers to embark on similar schemes, and 11 companies have now joined together in a World Cocoa Foundation alliance to protect rainforest from further destruction by cocoa farmers looking for new land.

Although Mondelēz is protecting its own interests by ensuring its cocoa supply chain, Cathy Pieters is clear that the programme is much more than that alone: “We pioneered Cocoa Life to address cocoa farm productivity alongside community development. We strive to not only empower cocoa farmers but also to help their communities thrive.

“We help them find real solutions like diversifying their income beyond the farm, which in turn develops their capacity to stand strongly on their own feet. I believe when we involve farmers as part of the solution, we see lasting, positive change happen.”

E. Coli Threat: Americans Warned Not to Eat Romaine Lettuce

PHOENIX—U.S. health officials on Friday told consumers to throw away any store-bought romaine lettuce they have in their kitchens and warned restaurants not to serve it amid an E. coli outbreak that has sickened more than 50 people in several states.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expanded its warning about tainted romaine from Arizona, saying information from new illnesses led it to caution against eating any forms of the lettuce that may have come from the city of Yuma. Officials have not found the origin of the contaminated vegetables.

Previously, CDC officials had only warned against chopped romaine by itself or as part of salads and salad mixes. But they are now extending the risk to heads or hearts of romaine lettuce.

People at an Alaska correctional facility recently reported feeling ill after eating from whole heads of romaine lettuce. They were traced to lettuce harvested in the Yuma region, according to the CDC.

So far, the outbreak has infected 53 people in 16 states. At least 31 have been hospitalized, including five with kidney failure. No deaths have been reported.

Symptoms of E. coli infection include diarrhea, severe stomach cramps and vomiting.

The CDC’s updated advisory said consumers nationwide should not buy or eat romaine lettuce from a grocery store or restaurant unless they can get confirmation it did not come from Yuma. People also should toss any romaine they already have at home unless it’s known it didn’t come from the area, the agency said.

Restaurants and retailers were warned not to serve or sell romaine lettuce from Yuma.

Romaine grown in coastal and central California, Florida and central Mexico is not at risk, according to the Produce Marketing Association.

The Yuma region, which is roughly 185 miles (298 kilometers) southwest of Phoenix and close to the California border, is referred to as the country’s “winter vegetable capital.” It is known for its agriculture and often revels in it with events like a lettuce festival.

Steve Alameda, president of the Yuma Fresh Vegetable Association, which represents local growers, said the outbreak has weighed heavily on him and other farmers.

“We want to know what happened,” Alameda said. “We can’t afford to lose consumer confidence. It’s heartbreaking to us. We take this very personally.”

Growers in Yuma typically plant romaine lettuce between September and January. During the peak of the harvest season, which runs from mid-November until the beginning of April, the Yuma region supplies most of the romaine sold in the U.S., Alameda said. The outbreak came as the harvest of romaine was already near its end.

While Alameda has not met with anyone from the CDC, he is reviewing his own business. He is going over food safety practices and auditing operations in the farming fields.

Colin Kaepernick Honored by Amnesty International

AMSTERDAM—Human rights organization Amnesty International has honored former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick with its Ambassador of Conscience Award for 2018, lauding his peaceful protests against racial inequality.

The former San Francisco 49ers star was handed the award at a ceremony Saturday in the Dutch capital by onetime teammate Eric Reid.

Kaepernick first took a knee during the pre-game playing of the American national anthem when he was with the 49ers in 2016 to protest police brutality.

Other players joined him, drawing the ire of President Donald Trump, who called for team owners to fire such players.

In response to the player demonstrations, the NFL agreed to commit $90 million over the next seven years to social justice causes in a plan.

Amnesty International Secretary General Salil Shetty called Kaepernick, “an athlete who is now widely recognized for his activism because of his refusal to ignore or accept racial discrimination.”

Kaepernick wasn’t signed for the 2017 season following his release in San Francisco. Reid, a safety who is now a free agent, continued Kaepernick’s protests by kneeling during the anthem last season. Reid has said he will take a different approach in 2018.

Amnesty hands its award each year to a person or organization, “dedicated to fighting injustice and using their talents to inspire others.”

Previous recipients of the award include anti-Apartheid campaigner and South African President Nelson Mandela and Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani schoolgirl who campaigned for girls’ right to education even after surviving being shot by Taliban militants.

“In truth, this is an award that I share with all of the countless people throughout the world combating the human rights violations of police officers, and their uses of oppressive and excessive force,” Kaepernick said.

Natalie Portman Snubs the ‘Jewish Nobel,’ and Netanyahu

JERUSALEM—Actress Natalie Portman has snubbed a prestigious prize known as the “Jewish Nobel,” saying she did not want her attendance to be seen as an endorsement of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Portman was to have received the award in Israel in June and said in a statement issued early Saturday that her reasons for skipping the ceremony had been mischaracterized by others, and she is not part of the BDS, a Palestinian-led global movement of boycott, divestment and sanctions against Israel.

News of Portman’s decision to skip the event triggered an angry backlash Friday from some in the country’s political establishment.

That was due to reports that Portman through a representative had told the Genesis Prize Foundation she was experiencing “extreme distress” over attending its ceremony and would “not feel comfortable participating in any public events in Israel.”

Portman’s statement said her decision had been mischaracterized.

“Let me speak for myself. I chose not to attend because I did not want to appear as endorsing Benjamin Netanyahu, who was to be giving a speech at the ceremony,” she wrote.

“Like many Israelis and Jews around the world, I can be critical of the leadership in Israel without wanting to boycott the entire nation. I treasure my Israeli friends and family, Israeli food, books, art, cinema, and dance.’”

She asked people to “not take any words that do not come directly from me as my own.”

Israel faces some international criticism over its use of lethal force in response to mass protests along the Gaza border led by the Islamic militant group that rules the territory.

One Israeli lawmaker warned that Portman’s decision is a sign of eroding support for Israel among young American Jews.

The Jerusalem-born Portman is a dual Israeli-American citizen. The Oscar-winning actress moved to the United States as a young girl, evolving from a child actress into a widely acclaimed A-list star. Portman received the 2011 best actress Academy Award for “Black Swan,” and, in 2015, she directed and starred in “Tale of Love and Darkness,” a Hebrew-language film set in Israel based on an Amos Oz novel. Her success is a great source of pride for many Israelis.

The Genesis Prize Foundation said Thursday that it had been informed by Portman’s representative that “recent events in Israel have been extremely distressing” to Portman, though it did not refer to specific events.

Since March 30, more than three dozen Palestinians have been killed by Israeli army fire, most of them in protests on the Gaza-Israeli border. Hundreds more have been wounded by Israeli troops during this time.

Israel says it is defending its border and accuses Hamas, a militant group sworn to Israel’s destruction, of trying to carry out attacks under the guise of protests. It has said that some of those protesting at the border over the past few weeks tried to damage the fence, plant explosives and hurl firebombs, or flown kites attached to burning rags to set Israeli fields on fire. Several Israeli communities are located near the Gaza border.

Rights groups have branded open-fire rules as unlawful, saying they effectively permit soldiers to use potentially lethal force against unarmed protesters.

Israel’s right-wing Culture Minister Miri Regev said in a statement Friday that she was sorry to hear that Portman “has fallen like a ripe fruit into the hands of BDS supporters,” referring to the Palestinian-led boycott movement.

“Natalie, a Jewish actress born in Israel, is joining those who relate to the wondrous success story of Israel’s rebirth as a story of ‘darkness and darkness’,” Regev said.

Rachel Azaria, a lawmaker from the centrist Kulanu party, warned that Portman’s decision to stay away is a sign of eroding support for Israel among young American Jews.

“The cancellation by Natalie Portman needs to light warning signs,” Azaria said in a statement. “She is totally one of us. She identifies with her Jewishness and Israeli-ness. She is expressing now the voices of many in U.S. Jewry, mainly those of the young generation. This is a community that was always a significant anchor for the state of Israel. The price of losing them could be too high.”

Oren Hazan, a legislator in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-wing Likud Party, called on the government to revoke Portman’s Israeli citizenship.

Gilad Erdan, Israel’s Public Security Minister said he sent a letter to Portman expressing his disappointment. “Sadly, it seems that you have been influenced by the campaign of media misinformation and lies regarding Gaza orchestrated by the Hamas terrorist group,” he wrote.

He invited her to visit and see for herself the situation on the ground.

The Genesis foundation said it was “very saddened” by Portman’s decision and would cancel the prize ceremony, which had been set for June 28.

“We fear that Ms. Portman’s decision will cause our philanthropic initiative to be politicized, something we have worked hard for the past five years to avoid,” it said.

Portman said in her statement that the backlash has inspired her to make numerous contributions to charities in Israel. She pledged to announce those grants soon.

The Genesis Prize was launched in 2013 to recognize Jewish achievement and contributions to humanity. Previous recipients include former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, actor Michael Douglas, violinist Itzhak Perlman and sculptor Anish Kapoor.

When Portman was announced late last year as the 2018 recipient, she said in a statement released by organizers at the time that she was “proud of my Israeli roots and Jewish heritage.”

April 20, 2018

Fox in the Hen House: Why Interest Rates Are Rising

On March 31 the Federal Reserve raised its benchmark interest rate for the sixth time in three years and signaled its intention to raise rates twice more in 2018, aiming for a Fed funds target of 3.5 percent by 2020. LIBOR (the London Interbank Offered Rate) has risen even faster than the Fed funds rate, up to 2.3 percent from just 0.3 percent 2 1/2 years ago. LIBOR is set in London by private agreement of the biggest banks, and the interest on $3.5 trillion globally is linked to it, including $1.2 trillion in consumer mortgages.

Alarmed commentators warn that global debt levels have reached $233 trillion, more than three times global GDP, and that much of that debt is at variable rates pegged either to the Fed’s interbank lending rate or to LIBOR. Raising rates further could push governments, businesses and homeowners over the edge. In its Global Financial Stability report in April 2017, the International Monetary Fund warned that projected interest rises could throw 22 percent of U.S. corporations into default.

Then there is the U.S. federal debt, which has more than doubled since the 2008 financial crisis, shooting up from $9.4 trillion in mid-2008 to over $21 trillion now. Adding to that debt burden, the Fed has announced it will be dumping its government bonds acquired through quantitative easing at the rate of $600 billion annually. It will sell $2.7 trillion in federal securities at the rate of $50 billion monthly beginning in October. Along with a government budget deficit of $1.2 trillion, that’s nearly $2 trillion in new government debt that will need financing annually.

If the Fed follows through with its plans, projections are that by 2027, U.S. taxpayers will owe $1 trillion annually just in interest on the federal debt. That is enough to fund President Trump’s original trillion-dollar infrastructure plan every year. And it is a direct transfer of wealth from the middle class to the wealthy investors holding most of the bonds. Where will this money come from? Even crippling taxes, wholesale privatization of public assets and elimination of social services will not cover the bill.

With so much at stake, why is the Fed increasing interest rates and adding to government debt levels? Its proffered justifications don’t pass the smell test.

‘Faith-Based’ Monetary Policy

In setting interest rates, the Fed relies on a policy tool called the “Phillips curve,” which allegedly shows that as the economy nears full employment, prices rise. The presumption is that workers with good job prospects will demand higher wages, driving prices up. But the Phillips curve has proved virtually useless in predicting inflation, according to the Fed’s own data. Former Fed Chairman Janet Yellen has admitted that the data fail to support the thesis, and so has Fed Governor Lael Brainard. Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari calls the continued reliance on the Phillips curve “faith-based” monetary policy. But the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which sets monetary policy, is undeterred.

“Full employment” is considered to be 4.7 percent unemployment. When unemployment drops below that, alarm bells sound and the Fed marches into action. The official unemployment figure ignores the great mass of discouraged unemployed who are no longer looking for work, and it includes people working part-time or well below capacity. But the Fed follows models and numbers, and as of this month, the official unemployment rate had dropped to 4.3 percent. Based on its Phillips curve projections, the FOMC is therefore taking steps to aggressively tighten the money supply.

The notion that shrinking the money supply will prevent inflation is based on another controversial model, the monetarist dictum that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”: Inflation is always caused by “too much money chasing too few goods.” That can happen, and it is called “demand-pull” inflation. But much more common historically is “cost-push” inflation: Prices go up because producers’ costs go up. And a major producer cost is the cost of borrowing money. Merchants and manufacturers must borrow in order to pay wages before their products are sold, to build factories, buy equipment and expand. Rather than lowering price inflation, the predictable result of increased interest rates will be to drive consumer prices up, slowing markets and increasing unemployment—another Great Recession. Increasing interest rates is supposed to cool an “overheated” economy by slowing loan growth, but lending is not growing today. Economist Steve Keen has shown that at about 150 percent private debt to GDP, countries and their populations do not take on more debt. Rather, they pay down their debts, contracting the money supply. That is where we are now.

The Fed’s reliance on the Phillips curve does not withstand scrutiny. But rather than abandoning the model, the Fed cites “transitory factors” to explain away inconsistencies in the data. In a December 2017 article in The Hill, Tate Lacey observed that the Fed has been using this excuse since 2012, citing one “transitory factor” after another, from temporary movements in oil prices to declining import prices and dollar strength, to falling energy prices, to changes in wireless plans and prescription drugs. The excuse is wearing thin.

The Fed also claims that the effects of its monetary policies lag behind the reported data, making the current rate hikes necessary to prevent problems in the future. But as Lacey observes, GDP is not a lagging indicator, and it shows that the Fed’s policy is failing. Over the last two years, leading up to and continuing through the Fed’s tightening cycle, nominal GDP growth averaged just over 3 percent, while in the two previous years, nominal GDP grew at more than 4 percent. Thus “the most reliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy, nominal GDP, is already showing the contractionary impact of the Fed’s policy decisions,” says Lacey, “signaling that its plan will result in further monetary tightening, or worse, even recession.”

Follow the Money

If the Phillips curve, the inflation rate and loan growth don’t explain the push for higher interest rates, what does? The answer was suggested in an April 12 Bloomberg article by Yalman Onaran, titled “Surging LIBOR, Once a Red Flag, Is Now a Cash Machine for Banks.” He wrote:

The largest U.S. lenders could each make at least $1 billion in additional pretax profit in 2018 from a jump in the London interbank offered rate for dollars, based on data disclosed by the companies. That’s because customers who take out loans are forced to pay more as Libor rises while the banks’ own cost of credit has mostly held steady.

During the 2008 crisis, high LIBOR rates meant capital markets were frozen, since the banks’ borrowing rates were too high for them to turn a profit. But U.S. banks are not dependent on the short-term overseas markets the way they were a decade ago. They are funding much of their operations through deposits, and the average rate paid by the largest U.S. banks on their deposits climbed only about 0.1 percent last year, despite a 0.75 percent rise in the Fed funds rate. Most banks don’t reveal how much of their lending is at variable rates or indexed to LIBOR, but Onaran comments:

JPMorgan Chase & Co., the biggest U.S. bank, said in its 2017 annual report that $122 billion of wholesale loans were at variable rates. Assuming those were all indexed to Libor, the 1.19 percentage-point increase in the rate in the past year would mean $1.45 billion in additional income.

Raising the Fed funds rate can be the same sort of cash cow for U.S. banks. According to a December 2016 Wall Street Journal article titled “Banks’ Interest-Rate Dreams Coming True”:

While struggling with ultralow interest rates, major banks have also been publishing regular updates on how well they would do if interest rates suddenly surged upward. … Bank of America … says a 1-percentage-point rise in short-term rates would add $3.29 billion. … [A] back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests an incremental $2.9 billion of extra pretax income in 2017, or 11.5% of the bank’s expected 2016 pretax profit. …

As observed in an April 12 article on Seeking Alpha:

About half of mortgages are … adjusting rate mortgages [ARMs] with trigger points that allow for automatic rate increases, often at much more than the official rate rise. …One can see why the financial sector is keen for rate rises as they have mined the economy with exploding rate loans and need the consumer to get caught in the minefield.

Even a modest rise in interest rates will send large flows of money to the banking sector. This will be cost-push inflationary as finance is a part of almost everything we do, and the cost of business and living will rise because of it for no gain.

Cost-push inflation will drive up the consumer price index, ostensibly justifying further increases in the interest rate, in a self-fulfilling prophecy in which the FOMC will say: “We tried—we just couldn’t keep up with the CPI.”

A Closer Look at the FOMC

The FOMC is composed of the Federal Reserve’s seven-member Board of Governors, the president of the New York Fed and four presidents from the other 11 Federal Reserve Banks on a rotating basis. All 12 Federal Reserve Banks are corporations, the stock of which is 100 percent owned by the banks in their districts; and New York is the district of Wall Street. The Board of Governors currently has four vacancies, leaving the member banks in majority control of the FOMC. Wall Street calls the shots, and Wall Street stands to make a bundle off rising interest rates.

The Federal Reserve calls itself independent, but it is independent only of government. It marches to the drums of the banks that are its private owners. To prevent another Great Recession or Great Depression, Congress needs to amend the Federal Reserve Act, nationalize the Fed and turn it into a public utility, one that is responsive to the needs of the public and the economy.

Chris Hedges's Blog

- Chris Hedges's profile

- 1922 followers