Chris Hedges's Blog, page 595

May 6, 2018

The Hemisphere’s Biggest Solar Plant Is in Mexico, Not the U.S.

Mexico wants to produce 43% of its electricity from renewables by 2024, in only 6 years. It has 58 new power plants planned, the majority of them solar and the rest wind. Toward that end, in December it opened the Villanueva solar farm in the desert, with 2.3 million solar panels, generating enough juice to power 1.3 million homes. It is the largest solar project in the Western hemisphere.

That’s right. The largest solar installation in the New World is not in the United States. It is in Mexico. The US has withdrawn from the Paris climate accords and has no plans to generate any particular percentage of its electricity from renewables by any particular year. In fact, it is going backward in wanting to revive coal.

This promotional video for Villanueva gave me goosebumps. If you want to see what the large-scale greening of the planet’s grid looks like, take a gander.

I am saying it. In this regard, Mexico is much better than we are.

In the first quarter of 2018, India set a record with the addition of 4.6 gigawatts of solar! That’s the name plate capacity of four small nuclear reactors, added in just one quarter. A lot of this new capacity was driven by bids at the level of the states. Solar electricity production in India has doubled in just the past year. By the end of January India had 20 gigawatts of installed solar power capacity. It now has 22 gigs. In contrast, France only has 8 gigawatts of installed solar capacity. India’s overall photovoltaic installations this year may be down a bit, however. Still the future is clearly very bright for Indian PV.

The Indian government wants 100 gigawatts of connected grid solar capacity by 2022. It is therefore planning to auction 30 gigawatts in each of 2019 and 2020.

Unfortunately, India hasn’t gotten the message about coal, and it is still also putting in massive amounts of new coal electricity generation. That unwise step (which increasingly makes no sense economically but maybe makes Indian Big Coal happy) will contribute to the erosion of valuable seaside real estate in India as it puts more heat-trapping CO2 into the atmosphere and causes surface ice to melt. Warm water also expands as it heats up, and so global heating contributes to rising seas as well. Moreover, parts of India will go arid and reduce food production; some parts of the subcontinent may become uninhabitable because of high temperatures. If India absolutely had to put in new hydrocarbon-driven electricity plants, it should instead use natural gas, which is half as carbon intensive as coal.

Dubai will tender a bid before the end of this year for a 300 megawatt solar farm, as part of its plan to get 7% of its electricity from solar by 2020. Since Dubai is one of seven emirates making up the United Arab Emirates, a major oil exporter, this push for renewables may on the surface seem hard to explain.

But look more closely. Dubai does not have its own hydrocarbons and is rather a service economy (banking and entertainment are big). Dubai’s need for hydrocarbons makes it more dependent on other emirates in the state that do have them. Even Abu Dhabi, which does have hydrocarbons, mainly has petroleum (it sends most of it to Japan). It is rare for electricity to be generated with oil. That is relatively expensive and anyway it means you’re using the oil for domestic power rather than selling it abroad at a premium. The fact is that the UAE is still importing natural gas for power generation from Qatar, despite its blockade on that country, which is pretty embarrassing.

So for all kinds of reasons, it is highly beneficial for Dubai to get its electricity from solar, the fuel of which is free down the line once installment costs are paid off. The UAE gets enormous amounts of sunshine and bids have been let there for as little as 2.5 cents a kilowatt hour, which is world-beating. Coal, one of the cheapest hydrocarbons, is typically 5 cents a kilowatt hour (though if you count externalities like sinking Florida it is off course much more expensive than that). So if everyone could get electricity from solar at the sort of rates now becoming common in Dubai, no one would ever buy another lump of coal, except to put in the Christmas stocking of naughty boys like Trump.

—–

May 5, 2018

Armed Teachers, Cops at Schools Linked to 30 Gun Mishaps Since 2014

They are the “good guys with guns” the National Rifle Association says are needed to protect students from shooters: a school police officer, a teacher who moonlights in law enforcement, a veteran sheriff.

Yet in a span of 48 hours in March, the three were responsible for gun safety lapses that put students in danger.

The school police officer accidentally fired his gun in his Virginia office, sending a bullet through a wall into a middle school classroom. The teacher was demonstrating firearm safety in California when he mistakenly put a round in the ceiling, injuring three students who were hit by falling debris. And the sheriff left a loaded service weapon in a locker room at a Michigan middle school, where a sixth-grader found it.

All told, an Associated Press review of news reports collected by the nonprofit Gun Violence Archive revealed more than 30 publicly reported mishaps since 2014 involving firearms brought onto school grounds by law enforcement officers or educators. Guns went off by mistake, were fired by curious or unruly students, and were left unattended in bathrooms and other locations.

“If this can happen with a highly trained police officer, why would we give teachers guns?” interim superintendent Lois Berlin of the Alexandria, Virginia, school system asked after the incident involving the officer whose accidental discharge put a bullet through a wall at George Washington Middle School. He was placed on leave and is under investigation.

Amid a nationwide push to arm teachers or add more police officers and armed guards, the AP review suggests that doing so will almost certainly have unintended consequences. The accidents are rare, but the actual number is probably higher because schools are not required to report them. And they have frightened students, outraged parents, prompted disciplinary and criminal investigations and left at least nine people injured.

Some insurance companies have refused to cover schools that allow non-law enforcement personnel to be armed. And many school employees have said in surveys that they would feel less safe if more of their colleagues were carrying weapons.

Nevertheless, calls to encourage districts to add more armed educators and officers have intensified since the Feb. 14 shooting rampage at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, that left 17 students and educators dead.

Speaking Friday to the NRA convention in Dallas, President Donald Trump called for allowing trained teachers to carry concealed weapons in schools, along with more armed security guards.

He said the best deterrent to would-be school shooters is “the knowledge that their attack will end their life and end in total failure.”

He added, “When they know that, they’re not going in.”

In March, the White House pledged to provide aid to state and local agencies to provide firearms training for school personnel and to recruit more veterans and retired officers into education. At least a dozen states have considered bills this year that would encourage more armed officers, security guards or teachers in public schools.

Supporters of allowing more school personnel to carry weapons argue that proper training would prevent such incidents.

“It’s usually the person behind the gun who determines the outcome,” said Kansas state Sen. Dennis Pyle, a Republican and supporter of a stalled bill that would have prohibited insurance companies from charging “unfair discriminatory” rates to schools that arm their staff.

A representative of the NRA declined to comment on the AP’s findings.

Sean Simpson is among the educators who have said publicly they would be willing to have firearms training, but the Marjory Stoneman Douglas science teacher recently had his own mishap. He was charged after leaving his loaded handgun in a public restroom at a crowded beach pier in April. An intoxicated homeless man found the weapon and fired it before Simpson snatched it back, authorities said.

The National Association of School Resource Officers has raised concerns about allowing teachers to be armed, saying they may not have the training to use guns effectively during a high-stress situation or to keep them secure. The group is pushing for an officer in every public school instead.

Executive Director Mo Canady, a former school resource officer in Alabama, said he believes accidental discharges and other mistakes involving school officers’ guns are “much more rare than people might think.”

“When you’ve got 20,000 officers in schools across the country, things can happen. There’s no perfect situation,” he said.

Earlier this school year, a fifth-grader in St. Paul, Minnesota, managed to pull the trigger on a gun in an officer’s holster, firing a bullet into the floor. The same day in Florida, a parent discovered a school resource officer’s gun in a faculty bathroom. A deputy’s gun went off in Michigan last fall during a struggle with a high school student.

Parent Rashmi Pappu, who has two daughters at the Virginia school where a bullet went through a wall and into a refrigerator, said she was stunned by the incident because she wasn’t aware the school’s officer was armed.

“I want to know why he was even handling his gun in the school and what the procedure is,” she said. “I just felt that in a safe school environment, this is ridiculous.”

The same day as the Virginia incident, Dennis Alexander was teaching his criminal justice class at a high school in Seaside, California, when he pointed a gun at the ceiling as he checked to make sure it was not loaded. The weapon went off. At least one of the students injured has hired a law firm and is considering legal action.

Alexander resigned his jobs as a teacher and reserve police officer. He also apologized, as did Michael Main, the Isabella County, Michigan, sheriff whose gun was found in a gym locker room where he’d left it while changing uniforms.

“I have worked diligently my entire career to protect people, especially our youth,” Main said in a statement. “However, I have failed to do just that, and I’m devastated with my lack of accountability in this matter.”

__

Associated Press writer John Hanna in Topeka, Kansas, contributed to this report.

American History for Truthdiggers: Counterrevolution of 1787? New Constitution, New Nation

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the eighth installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His wartime experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 8 of “American History for Truthdiggers.” / See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7.

* * *

“Some men look at Constitutions with sanctimonious reverence, & deem them, like the Ark of the Covenant, too sacred to be touched. They ascribe to the men of the preceding age a wisdom more than human, and suppose what they did to be beyond amendment. I knew that age well: I belonged to it. …

“But I know also that laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind … we might as well require a man to wear still the coat which fitted him when a boy, as civilized society to remain ever under the regimen of their barbarous ancestors.” —Thomas Jefferson in a letter to Samuel Kercheval, July 12, 1816

The U.S. Constitution stands almost as American scripture, deified and all but worshipped as the holy book for the American civil religion of republicanism. The above painting captures the spirit of modern memories, and mythology, surrounding the Constitutional Convention, which was held in Philadelphia. The sun shines through windows (which are conspicuously open) and delivers a halo of light upon the figure of the tall, erect George Washington. He stands, of course, on what resembles a religious altar, presiding over the delegates as they sign the sacred compact of American governance. Ben Franklin, himself an international celebrity by that time, sits prominently in the center, as the influential, young Alexander Hamilton whispers in his ear; meanwhile, the “father” of the Constitution, James Madison, sits just below the altar, on Franklin’s left.

This is an illustrative depiction of the convention: glorious, dramatic and … mostly inaccurate. In reality the shades were drawn and the windows locked. The delegates—at least those who were there on any given day—conducted their business in total, purposeful secrecy. Fifty-five elite delegates, representing only 12 of the 13 Colonies (Rhode Island refused to send a representative), took it upon themselves to secretly craft a new formula for government that they decided to be in the best interest of “We the People.”

In the intervening 200-plus years, the Constitution has become sacred indeed, an influential foundation used by politicians on all sides of the ideological spectrum to bolster their arguments and justify all number of decisions. In our modern age of hyperpartisanship, to disagree with one side or the other is to hold beliefs that are unconstitutional, if not treasonous. Still, Americans rarely consider the actual events surrounding the convention or try to understand the text of the document itself. Nor do they bother to question the very peculiarity of a 231-year-old document informing the organization of the modern political and societal space.

The Founders, or in the case of the Constitution, the Framers, are now held in the esteem of veritable deities, a pantheon of American civic saints. Many active citizens, especially on the conservative political right, argue for originalism: the need to follow and understand the Constitution as it was written, back in the late 18th century. Indeed, originalism, in one form or another, seems ascendant in post-Reagan America. This, too, is curious, given that many—though not all—Founders were skeptical about such thinking way back when.

Thomas Jefferson, though not in attendance in Philadelphia (he was then ambassador to France), remained a powerful intellectual influence on the Framers, especially on his friend James Madison. Jefferson at that time, and even more fervently as the years passed, was unimpressed by the growing veneration of the founding generation. He was increasingly persuaded that “the earth belonged to the living,” that each generation must reassess its governing structure, and that to submit to the reasoning of our “barbarous ancestors” was a form of tyranny.

Jefferson and his tradition—among those then pejoratively labeled Anti-Federalists—fervently believed the Constitution must be open to amendment and regularly reassessed as the human mind and society progressed. Others, then and now, led by ardent nationalists such as young Alexander Hamilton, actively disagreed, preferring a fixed foundation of governance for “millions yet unborn.” That debate, of centralizing Federalists versus skeptical and fearful Anti-Feds, was a tumultuous legacy bequeathed to us all, one that is still raging in 2018.

In order to take a side, or even understand the dialogue, one must look backward; must shed the patriotic yarns taught in public schools for time immemorial, and understand the truth of events in the crucial post-revolutionary years of 1787-89. Hard questions must be asked: Why did so many Americans adopt a more powerful government so soon after revolting against another? Did the Constitution serve to expand or limit American liberty? The answers might surprise you.

As always, we must remember that nothing was inevitable—not the ratification of the Constitution, the presidency of George Washington or even the continued union of the 13 individual republics (or states). A deeper look at the actions and motivations of the Framers uncovers certain darker forces at work, complicates blind veneration, but leads the modern reader closer to truth and context. That story begins with 55 prominent men and a Philadelphia summer.

The Coup d’Etat of 1787?

“Genuine liberty requires a proper degree of authority. … All communities divide themselves into the few and the many. The first are the rich and well born, the other the mass of the people. … [The masses] seldom judge … right. Give therefore to the first class a distinct, permanent share of government.” —Alexander Hamilton

“Liberty may be endangered by the abuses of liberty as well as the abuses of power.” —James Madison

Many Americans, especially coastal elites, believed the revolutionary spirit had gone too far, especially among the middling folk and commoners. Shays’ Rebellion, state-level debt relief (seen almost as a form of modern welfare spending) and the apparent weaknesses of the Continental government, convinced many—often famous—elites that something had to be done. The problem, as Hamilton boldly labeled it, was one of how to rein in “an excess of democracy.” That, of course, doesn’t sound all that revolutionary; sounds rather contrary to the beloved “spirit of ’76.”

Hamilton and Madison, among other nationalists (those who believed in a more powerful central government), led the fight to amend the existing constitution of the allied states, the Articles of Confederation. They believed the state-level legislators were too close to their constituents, and too lenient on debt and taxation. This, they believed, explained the postwar recession of the 1780s. Madison, Hamilton and even Washington, among others, believed the state legislatures to be too susceptible to popular pressure—too democratic, one might say.

Other nationalists, or as they would begin to call themselves, Federalists, sought external security through internal union. Think, then, of things in a new way: The 1787 Convention was essentially an international meeting with envoys from 12 of 13 independent states, or countries, seeking to strengthen a loose confederation into one nation. Thus, some hoped, the U.S. could elude both internal and external diplomatic dangers. There would, necessarily, be trade-offs. As the authors of the essay Federalist Number 7 would write: “to be more safe, [we] must risk being less free.” Seen in this light, security, as much as politics or economics, motivated the drive toward centralization.

This, of course, was all rather strange. Had not the very purpose of the revolution been to demand local representation and dispute governance from a distant body (in London)? Local rule, local decisions—the “spirit of ’76”! How different, then, was centralized rule from (also distant) New York or Philadelphia? In an era where, as historian Joseph Ellis reminds us, the average person strayed no more than 26 miles from his or her birthplace in an entire lifetime, a convention in Philadelphia was, for all intents and purposes, as far away as a parliament in London.

Still they met, these rather few delegates in Philadelphia in 1787. Their mandate, specified by the legal governing body of the day—the Confederation Congress—was simply to discuss and recommend changes to the Articles. And it is here, then, in the forthcoming decisions of the 55 delegates, in which matters got complicated.

Whatever else the Philly convention and the final drafted Constitution was, it was unconstitutional, the Articles then being the law of the land. Almost immediately, these unelected delegates—chosen by the state legislatures and not “We the People”—decided unilaterally to ignore Congress and scrap the entire Articles of Confederation. They would, instead, write an entirely new constitution and present it to the states and the people. It should not surprise us that they decided thus. For the most part the deck was stacked. Only Federalist-inclined men generally sought to attend, and most skeptics (including all of those who lived in the state of Rhode Island) refused to take part.

Immediately, the delegates voted to conduct all their actions in secret. The doors would be locked and the windows cloaked, and no letters about the proceedings or public proclamations would be allowed. This, they believed, would allow the men (and they all were men, and white) to speak freely and frankly. Still, this sort of secrecy hardly seemed to gel with truly republican principles. Yet so it would be, as a few dozen, unelected, nationalist-inclined, prominent men, secretly—and one could argue, illegally—decided to ignore their charter and craft a new, more-centralized government on behalf of the people of America. Furthermore, while the Articles of Confederation required unanimity among the states to be amended, the Framers unilaterally decided to change the very rules of the game: Ratification of the new constitution, they said, would require the consent of only nine out of the 13 state legislatures.

What an odd foundation, what dubious circumstances, for a document so revered by succeeding generations. Little wonder then that some have taken to calling the Constitutional Convention the Framers’ Coup. Seen in a certain light, the sentiment rings true, even if the simplicity of this alternative reading is itself flawed. Of course, few Americans know this more complex history of the Constitution. How, then, could they not blindly revere the resultant document. Perhaps that’s the point. The history that is written, the history that is widely taught, represents a conscious decision; a decision that is, more often than not, politically motivated.

Qui Bono?—An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution

“The convention of Philadelphia is to consist of members of such ability, weight and experience, that the result must be beneficial.”—John Adams, letter to John Jay, May 8, 1787

“The protection of [property] is the first object of government.”—James Madison, excerpt from Federalist Number 10

In 1913, the historian Charles Beard, an intellectual leader of the Progressive movement and U.S. liberalism, wrote one of the most influential and controversial books in U.S. history: “An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States.” In his bombshell, Beard argued that the primary motive for most Framers was to establish a strong central government that would protect their financial interests and enrich them personally. His narrative turned the founding myth on its head and shocked the academic world.

To understand why Beard thought this way, we must examine just who these 55 delegates were. First off, remember what they weren’t—common farmers or small shopkeepers. No, these were elites, individuals of wealth and, in some cases, fame. As mentioned earlier, all were male and white. More than half were college-educated at a time when less than 1 percent of the population was. Fifty-eight percent were lawyers, 31 percent owned slaves and 22 percent boasted large plantations. This will not surprise most readers. But there was something else. Twenty percent were securities speculators, or major bond holders. Eleven percent speculated in western land and hoped to turn a profit west of the Appalachians. Remember Shays’ Rebellion. That revolt kicked off when small farmers were heavily taxed and required to pay in gold and silver to fund war bonds and Continental paper money, both of which were at that point owned by wealthy speculators to a large extent.

Most of the Continental IOUs began in the hands of Revolutionary War soldiers and their suppliers, but amid rampant inflation and in desperate need of hard currency, most veterans sold off their bonds and their paper money to speculators for a fraction of the face value. Daniel Shays, the namesake of Shays’ Rebellion, was one of them; another was fellow military veteran Joseph Plumb Martin. Martin went to his grave bitter about his lack of pay and overall treatment by the national government. He described how at war’s end, the men in his unit who had paper bills sold them off “to procure decent clothing and money sufficient to enable them to pass with decency through the country [on their way home].”

A Continental $50 bill issued by the Revolutionary Continental Congress in 1778. These bills were subject to severe devaluation and inflation by the time of the Constitutional Convention and had been mostly bought up by securities speculators.

By the time of the Constitutional Convention, only 2 percent of Americans—very few of them former soldiers or the original recipients—owned bonds. Nevertheless, in the years to come, a huge portion of the state and federal tax revenue would go to servicing and paying interest on those bonds. There was just one problem: In the minds of the wealthy, the Articles of Confederation was insufficient to enforce debts. After all, it had no power to tax, and the state legislatures were proving too responsive to clamors for debt relief from their constituents. Bondholders, creditors and speculators—including many of the Framers—were terrified of the new post-revolutionary power of uneducated, indebted farmers in their local governments. These men of wealth feared for themselves and other prominent citizens, who, incidentally, the Framers believed were best suited to govern society.

Many credit-holding elites feared they would never be paid and recoup debts owed unless a strong federal government could collect taxes and had the power to enforce contracts. Beyond their personal interests, though, they also believed that only a strong central government could ensure a prosperous economy. Indeed, for many economic nationalists the two key provisions of the Constitution fell under Article I, Section 8 and 10. These clauses gave the federal government the power to tax and prohibited the states from rescuing debtors or printing paper money. Some said that even if just those two provisions made it into the new constitution, it would still be well worth voting for.

But was it that simple? Certainly, self-interest seemed to play a role, and no doubt the Framers were mostly moneyed elites. Madison himself stated that the new federal government ought “to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority.”

Without a doubt, the interests of the wealthy were front and center in the new Constitution. Still, Beard’s overly simplistic economic determinism erases the agency of Framers who were often enthusiastic nationalists and true believers. Indeed, Madison and Hamilton—thought of as “fathers” of the Constitution—were not themselves major creditors or bondholders. Besides, in the minds of these 18th-century elites, only property and wealth could render a man politically independent, out of reach of bribery and economic intimidation. This, they believed, was the surest path to public virtue.

Compromised by Compromises: The Emerging Constitution

“No mention was made of negroes or slaves in this Constitution … because it was thought the very words would contaminate the glorious fabric of American liberty.” —Dr. Benjamin Rush in a letter to Dr. John Lettsom, September 1787

American children, children who grow up to be politically active adults, are led to believe—and they usually do so with all their hearts—that the Constitution was, from the first, an inherently democratic document. But what if it wasn’t? What if, instead, it represented rather an attempt to drive a wedge between the people and their government and, ultimately, represented little more than a compromise between factions? To understand the Constitution thus is not to forever tarnish its legacy, but rather to know it in its own context, and to maintain a critical eye in contemporary political debates. That, of course, is a dangerous road, one sure to upset originalists and the powerful.

There are, in fact, three distinct ironies about the American Constitution that emerged from the Philadelphia Convention. First, the Framers intended to write a less democratic document, and—though it took generations—ended up with one of the more democratic countries on earth. Second, the delegates were responding to problems (state legislative excesses and economic anxiety) that were inflated and exaggerated. Nonetheless, they proceeded as though their biased opinions were self-evident truths. The document reflects that. And, finally, as we shall see, Americans have the Anti-Federalist opponents of the Constitution to thank for the democratic, civil libertarian protections found in the cherished Bill of Rights.

Most arguments, and eventual compromises, centered around three key debates: over representation, the presidency, and slavery. Most in the stacked deck of federalist Framers desired a legislative branch that was less responsive than that of the local state governments. Larger districts and fewer total representatives (each congressman would now represent 10 times the constituents of an average state assemblyman), Madison believed, was the best way to shield the federal government from too much popular pressure. It was necessary, he said, to “extend the sphere” of governance and create more distance between representatives and citizens.

Some wanted senators to serve for life. Six-year terms was the compromise, but this was still a very long tenure in a time of annual elections at the state level. Madison thought that the Senate should be able to veto any state law. Charles Pinckney of South Carolina argued that “no salary be allowed” for senators because the Senate “was meant to represent the wealth of the country.” There were debates and disagreements on these points, but most Framers agreed with the basic premise of distant, less-responsive representation.

The more difficult matter was how the legislative seats ought to be divided among the states. Large, populous states, backing the Virginia Plan, wanted a bicameral (two-house) Congress with proportional representation in both chambers. Smaller states backed the New Jersey Plan and equal representation among each of the sovereign states. Eventually, the two sides came to a compromise, by Connecticut, and agreed on proportional representation in the House and two senators for each individual state. It remains so today. Furthermore, senators would not be elected by the people, but rather by state legislatures. This would not change until the early 20th century. When it came to representation, the Constitution crafted a legislature far less responsive than those of the states.

Other debates surrounded the figure of the executive branch—the president. Under the Articles there was no executive. After all, the states had just rebelled against a king! Many, like Hamilton, though, wanted a sort of “Polish King,” an executive elected for life. This was blocked, but the eventual outcome was a presidency vested with significant powers (vetoes, commander-in-chief authority and pardons) and not constrained by term limits. Washington chose to set a precedent of stepping down after two terms—one that more than 30 consecutive presidents would follow—but he was not obliged to so. Not until the 1950s was the two-term limit written into a constitutional amendment.

More interestingly, the people would not directly elect the president. Rather, here too there would be distance between the government and the citizenry. The people would vote for electors who would then select the chief executive. Furthermore, elections would be an all-or-nothing game with the electors from each state voting to give all the state’s electoral votes to a candidate of choice, no matter how close the vote. The Electoral College still stands, and its existence explains how and why certain presidents (John Quincy Adams, Rutherford B. Hayes, Benjamin Harrison, George W. Bush and Donald Trump) have been elected despite losing the popular vote.

Original Sin: The 3/5 Compromise—a Road to Civil War?

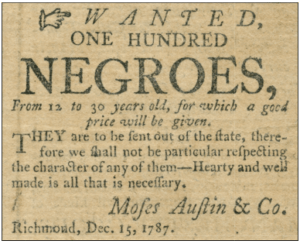

An advertisement that appeared in a Richmond, Va., newspaper in December 1787, shortly after the Constitutional Convention.

“[This Constitution] is a better security [for the institution of slavery] than any that now exists. No power is given to the general government to interpose with respect to the property in slaves now held by the states.” —James Madison in a speech reassuring delegates to the Virginia Constitutional Ratification Convention, June 1788

Perhaps the most infamous decision in the Constitution was the 3/5 Compromise. This representation arrangement was a concession to Southern states and their wealthy planters. According to the 3/5 rule—in force until the Civil War—each black slave would be counted as 60 percent of a person when calculating the number of House representatives allotted per state. Not that the slaves could vote, of course—they just counted.

The 3/5 clause had momentous, often disastrous, consequences. The math spoke for itself. The vote of one planter with 100 slaves would carry as much weight as that of 60 voters in the increasingly slave-free North. Southern states would punch above their weight in electoral politics for nearly a century, protecting and expanding slavery every step of the way. The 3/5 Compromise helps explain why five of the first seven presidents were slaveholding Southerners.

It also played a role in the agreement of the Framers not to restrict the slave trade—the forcible and brutal importation of more Africans—until 1808. The result: In the intervening 20 years more than 170,000 Africans were shipped across the Atlantic and into bondage in the southern United States. The prolific descendants of these slaves, those that survived, had populated the South when civil war finally came in 1861. Because of the 3/5 rule, the very existence of slaves lent more power and authority to their masters. The irony, according to historian Woody Holton, is that “in this instance, slaves’ interests would have been better served if they had not been considered persons at all.”

Nor can we explain away the 3/5 Compromise as merely a “sign of the times,” for many Americans were, indeed, appalled by this clause in 1787. One New Englander opposed to the Constitution wrote that “[the U.S.] had to remain a collection of republics, and not become an empire [because] if America becomes an empire, the seat of government will be to the southward … empire will suit the southern gentry; they are habituated to despotism by being the sovereigns of slaves.”

Even an eventual supporter, and Framer, of the Constitution, Philadelphia’s Gouverneur Morris, disliked the 3/5 Compromise and was horrified by the idea that

The inhabitant of Georgia and South Carolina who goes to the Coast of Africa, and in defiance of the most sacred laws of humanity, tears away his fellow creatures … and damns them to the most cruel bondages, shall have more votes instituted for protection of the rights of mankind, than the citizen of Pennsylvania or New Jersey.”

When it came to the Constitution as a final product, we must understand that the whole document was a compromise. Invisible common citizens were present in that room in Philadelphia. Left to their own devices, the Framers would have produced a government even less responsive and more aristocratic, but as they wrote the document they knew they would have to eventually get it ratified by the people. Hence, they softened the harshest clauses and generated the Constitution we all know—messy, flawed, and ever-changing.

Forgotten Founders: The Anti-Federalists and American Freedom

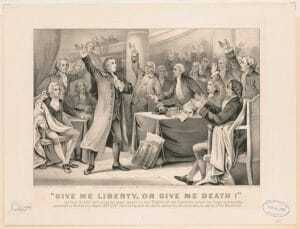

An 1876 lithograph of Patrick Henry speaking on the rights of the Colonies before the Virginia Assembly in 1775. He concluded with the declaration, “Give me liberty, or give me death!” which became the war cry of the Revolution. Henry later became an ardent Anti-Federalist.

“A powerful and mighty empire is incompatible with the genius of republicanism.” —Anti-Federalist Patrick Henry

The very terms of the debate that followed, that of ratification, were flawed. Federalists versus Anti-Federalists. They waged a semantic battle, above all. As historian Pauline Maier reminds us, “[T]he words we use, especially names, shape the stories we tell.” “Anti-Federalist” was a pejorative term, used by the Feds and never accepted by most opponents of the Constitution. It was also illogical. Anti-Federalists were actually more in favor of federalism, in the traditional sense of the term, and local autonomy. Perhaps Pro-Rats (ratification) and Anti-Rats would be a more accurate, if conversely depreciative, pair of labels.

It was also never a fair fight, not from the first. The history we know and are taught is a Federalist history, a history (spoiler alert) of the victors. The Federalists wrote most of the documents (like the famous Federalist Papers) on which historians depend. Back at the time, they owned most of the newspapers in the new nation. They tended to live in big cities and trading hubs, along key transportation routes. They were also for something tangible—a new, written Constitution—rather than against such a document, internally divided as to the right course, like the Anti-Federalists.

Still, there were ever so many Anti-Federalists of one stripe or another during the period of ratification (1787-89). They lived mostly in the west, or upstate (as in New York), far from the bustling cities and wealthy commercial elites. Historians estimate that about half the citizenry opposed the Constitution at the outset. Indeed, the Feds often got enough votes to ratify only by solemnly promising to immediately amend the Constitution. New Yorkers gave in only after (Federalist) New York City threatened to secede, and Rhode Island capitulated only after the other states imposed a trade boycott on the little state.

There were also some rather famous citizens among the Anti-Feds. Patrick Henry of Virginia (he of “Give me Liberty or Give me Death” fame!) was opposed to the end. So was Virginia’s George Mason (a future university namesake). Others initially opposed the Constitution but finally acquiesced (in however lukewarm a fashion), such as Samuel Adams, John Hancock and Thomas Jefferson.

The ratification debates were intense, and it was years before all 13 states adopted the Constitution. Some votes were ever so close: Massachusetts’ was 187 to 168, New Hampshire 57 to 47, Virginia 89 to 79, New York 30 to 27 and Rhode Island 34 to 32. In other words, adoption of the Constitution we now revere was a near-run thing. And, as close as these votes were, one must ask who actually got to do the voting. White, free men. In some states it was only those who owned property. Women, slaves and Indians weren’t consulted—a good thing as far as the Federalists were concerned. As we’ll see, odds are they would have opposed an empowered national government.

So just what did they fear, these various opponents of the Constitution? Simply put, they dreaded what the rebellious colonists had so feared:

● That the president would become an executive monarch—a concern that has been partly vindicated given the increasingly imperial powers of today’s presidency in foreign affairs.

● They feared an aristocratic Senate—which was understandable given that the people didn’t directly elect senators until 1913;

● They feared a distant, unresponsive House with the power of federal taxation—like Parliament! This is still an issue for libertarian conservatives in the modern tea party movement.

● And, of course, they feared a standing national army. This, no doubt, was an outgrowth of bad memories from the Revolutionary era. Indeed, consider the text of the Declaration of Independence: the gripe that King George had “kept among us, in times of peace, a standing army without the consent of our legislatures.” A prominent Anti-Federalist in Virginia, John Tyler, asked at his state’s ratifying convention whether “[we] shall sacrifice the peace and happiness of this country, to enable us to make wanton war?” Contemporary Americans, 17 years into an undeclared “war on terror,” might think it time to revisit Tyler’s question.

The point is that the Anti-Federalists were neither history’s villains nor simply its losers. They represented the political inclinations of a significant segment of 18th-century (and some might argue 21st-century) Americans.

* * *

“The Constitution proposed … is designed not for yourselves alone, but for generations yet unborn. The principles, therefore … ought to be clearly and precisely stated, and the most express and full declaration of rights have been made—But on this subject [the Constitution] is silent.” —Robert Yates (pen name: Brutus)

Historian Woody Holton recommends a teaching experiment, one I used with my cadets when I taught at West Point. I’d end my class on the subject by asking random cadets to name their favorite right or privilege guaranteed by the Constitution, which cadets had sworn to “support and defend.” Inevitably a hulking, male Texan would offer “the right to bear arms!” Others would chime in with free speech, a free press, and freedom of religion. Then I’d ask how many of those rights were contained in the document approved at the Constitutional Convention? Met by blank, confused stares, I’d level the answer: Zero.

It’s a trick question, of course. The Constitution, as first drafted, and ratified by the states, was solely a structure-of-government document. All our most treasured protections are found in the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, what became known as the Bill of Rights. Most staunch Federalists, in fact, insisted that the Constitution be ratified “as is,” and opposed a Bill of Rights. This, of course, raises a salient, if uncomfortable, question: If the motive for the Constitution wasn’t to safeguard liberty, well, then, what does that say about the document?

Actually, it was the Anti-Feds who insisted on, and strong-armed a promise for, a Bill of Rights during the contested ratification conventions. So, do you enjoy freedom of speech, of assembly, yes, even the right to bear arms? Well, thank the oft-forgotten Anti-Federalists. It’s possible, in fact, to argue that it was actually the Anti-Feds who hewed closer to the republican principles of the Revolution, to the “Spirit of ’76.” Taking a fresh look at the Constitution’s opponents also reminds us that there is value in studying our conflicts, and, sometimes, focusing on history’s “losers.”

A ‘Roof Without Walls’: The Legacy of the Constitution

“I suppose to be self-evident, that the earth belongs to the living; that the dead have neither powers nor rights over it … every constitution, then, and every law, naturally expires at the end of [each generation]. If it be enforced longer, it is an act of force and not of right.” —Thomas Jefferson in a letter to James Madison, Sept. 6, 1789

Barely a decade after revolting against an empire, the 13 former Colonies of America made the conscious decision—no doubt egged on by their prominent elites—to graft a powerful federal government onto their separate states and, in Woody Holton’s memorable words, “launch an empire of their own.” Why and how it happened, as we’ve seen, is rather complex. Of this much we can probably be sure: Without the experience of the war, it is unlikely there would have been any call for a centralized government. As Peter Onuf has noted, “revolutionary war-making and state-making were inextricably linked.” Wars demand powerful bureaucracies, and failures are unforgiving in the storm of conflict. The weaknesses and shortfalls of the Confederation Congress convinced many rebel leaders that something sturdier was necessary. But it did not convince them all.

A powerful opposition to the Constitution and the national government persevered and fought centralization at every turn. These resisters would not vanish after ratification, but rather form a new faction to oppose what they saw as the excesses of centralized power.

There is irony, in a sense, in our contemporary deification of the Constitution across the political spectrum. Perhaps this can be explained by the ethnic, religious and regional diversity of the early republic (and our present nation). American nationalism was peculiar, and was largely constitutional for a century or more (based on a document rather than a common ethnicity)—a condition that perhaps exists even until today. It is the Constitution that has come to bind us. This, of course, is strange because in the 1780s and 1790s it was that very Constitution that divided Americans.

What is more, modern Americans forget that, in the end, the Constitutional Convention constructed a new federal government “considerably less democratic than even the most conservative state constitutions.” As delegate Robert Morris said at the time, the new government was meant to “suppress the democratic spirit.” In a further irony, despite finishing a revolution against the British Crown just five years earlier, Hamilton and other, like-minded Framers believed that a respectable United States would have to become more, not less, like Britain.

And still, something was lost in the movement toward a stronger constitution. Annual elections, congressional term limits, grass-roots voting instructions from constituents, and popular control of the money supply: All these democratic measures—most of which dated back to the Colonial era—were gone forever. One wonders whether or not this was, truly, for the better.

There was still another motivation for the Philadelphia Convention: elite fear. Shays’ Rebellion and other grass-roots revolts convinced many wealthy leaders that a strong central government, with a standing army, was necessary to quell future unrest. Seen in this light, the Constitution was meant to suppress, not to safeguard liberty, at least from the perspective of certain parties. The Southern planters, too, were gripped with fear. They remembered well that that greatest slave revolt in American history—a part of the American Revolution—had recently occurred when many thousands of slaves flocked to the British lines. The new federal army would also, they surmised, be used to deter, or quash, future slave rebellions.

Those new government powers quickly translated into action as, from 1789 to 1795, U.S. Army manpower increased fivefold, its budget threefold, and the size of the Navy by a factor of 60! In a sense, this establishment of a standing army, though modest by today’s measures, appears counter to the revolutionary spirit and a repudiation of the values of 1776.

The Constitution, and the new army it helped create, also spelled doom for native tribes and unleashed a veritable bonanza in land sales in what was then the West. Sadly, the power of the post-revolutionary native confederation north of the Ohio River may have inadvertently signed the Indians’ death warrant. Indian resistance had stymied land sales (which it was hoped would fund the Confederation budget) and helped motivate the centralization instinct among prominent speculators—many of whom became Framers. They supported a powerful central government that could secure the land from Native Americans and ensure ample profits to boot.

* * *

Perhaps a fresh, nuanced look at the Constitution’s ratification ought to lead us to restructure our understanding of the era. Maybe rather than a simple revolution-to-republic narrative there were actually numerous revolutions: one revolution surrounding independence, followed by a social, democratic revolution during the Confederation, then, finally, a rather different transformation—a constitutional revolution that sought to centralize power, ensure “security” and work toward the creation of an American nation-state. That revolution has endured, but we must remember that, at least in its own day, it was a revolution against the “excesses of democracy” an un-democratic counterrevolution of 1787!

How then can the Constitution be, as so many Americans today insist it is, an infallible, divinely inspired document? It has, after all, been amended dozens of times. Furthermore, after 74 years, it ultimately failed; with the nation torn asunder by civil war, the original sin of slavery come home to roost. The death of hundreds of thousands of citizens was required to update and reimagine the Constitution. And so, as John Adams reminded his contemporaries, long after the Revolution: “divided we have ever been, and ever must be.”

Years after the Constitution became the law of the land, establishing a new powerful federal government, Fisher Ames, a staunch Massachusetts Federalist, described the new American political mood:

The fact really is, that … there is a want of accordance between our system [of government] and the state of our public opinion. The government is republican; opinion is essentially democratic. … Either, events will raise public opinion high enough to support our government, or public opinion will pull down the government to its own level. They must equalize.

We Americans are still thus divided between democratic sentiments and republican, indirect governance (how else could someone who received 3 million fewer votes than his opponent sit in the Oval Office?). Conservatives and liberals alike are still playing out this old debate. It remains to be seen if the United States can be both democratic and republican, to find a balance; or, for that matter, in these highly divided times, whether we can maintain the union itself.

In its own way, the turmoil of the 18th century is with us still.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

● James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle, and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 8: “Crisis and Constitution, 1776-1789” (2011).

● Charles A. Beard, “An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States” (1913).

● Saul Cornell, “The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788-1828” (1999).

● Edward Countryman, “The American Revolution” (1985).

● Joseph J. Ellis, “The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789” (2015).

● David C. Hendrickson, “Escaping Insecurity: The American Founding and the Control of Violence,” from “Between Sovereignty and Anarchy: The Politics of Violence in the Revolutionary Era” (2015).

● Woody Holton, “Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution” (2007).

● Pauline Maier, “Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788” (2010).

● John M. Murrin, “A Roof Without Walls: The Dilemma of American National Identity,” from “Beyond Confederation: Origins of the Constitution and American Identity” (1987).

● Gary B. Nash, “The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America” (2005).

● Peter S. Onuf, “Epilogue,” from “Between Sovereignty and Anarchy: The Politics of Violence in the Revolutionary Era” (2015).

● Robbie J. Totten, “Security, Two Diplomacies, and the Formation of the U.S. Constitution,” Diplomatic History 36, no. 1 (Jan. 2012).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

[The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.]

3 Degrees of Warming Could Double Europe’s Drought Risk

If average global temperatures rise by just 3°C [5.4 F], then Europe’s drought risk could increase to double the area faced with drying out. Right now, just 13% of the continent can be counted as a drought-prone region. As the thermometer soars, this proportion could rise to 26%.

And 400 million people could feel the heat as the water content in the European soils begins to evaporate. The worst droughts will last three to four times longer than they did in the last decades of the last century.

The number of months of drought in southern Europe could increase significantly. In this zone drought is already measured over 28% of the land area: this could, in the most extreme scenario, expand to 49%.

Iberian Extreme

“In the event of a three-degree warming, we assume there will be 5.6 drought months per year; up to now, the number has been 2.1 months. For some parts of the Iberian peninsula, we project that the drought could even last more than seven months,” said Luis Samaniego, of the UFZ Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Germany.

His co-author Stephan Thober added: “A three-degree temperature rise also means that the water content in the soil would decline by 35 millimetres up to a depth of two metres. In other words, 35,000 cubic metres of water will no longer be available per square kilometre of land.”

The two scientists, with colleagues from the UK, the US, the Netherlands and Czechoslovakia, report in Nature Climate Change that they used mathematical models to simulate the effect of temperature rise as a response to ever-greater global emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, from the combustion of fossil fuels.

The 35mm loss of water was roughly what parts of Europe experienced during the unprecedented drought of 2003. If planetary temperatures do rise by 3°C, then such episodes could become the normal state in many parts of Europe, and far worse could be on the way.

Once again, none of this will come as a shock to other climate scientists, who have repeatedly warned that the cost of not confronting the menace of climate change could be huge in terms of lives lost, forests burned and harvests ruined.

Europe’s cities could become uncomfortably and even potentially lethally hot, and the southern nations of the Mediterranean could face devastating heat and drought.

But such droughts are not inevitable, nor likely across the whole of Europe. The Baltic states and Scandinavia could experience higher rainfall in a warmer world. The same simulations found that – were the world to achieve the 1.5°C global warming limit which 195 nations agreed upon at the Paris climate summit in 2015 – then the Mediterranean region would experience only 3.2 months of drought. And water loss in the top two metres would be only about 8 millimetres.

Scheer Intelligence: Betsy West, Julie Cohen on Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Audio and Transcript)

In this week’s episode of “Scheer Intelligence,” host and Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer speaks with documentary filmmakers Betsy West and Julie Cohen about their new film on the life and career of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, also known as “RBG.”

West tells Scheer that Ginsburg “was initially surprised by her Notorious RBG persona, and how popular she was becoming with the younger generation,” but she now sees it as “an opportunity for her to reach a younger generation with her message.”

The filmmakers recount how Ginsburg was initially wary about allowing them to film her, but eventually she trusted them to capture an intimate look at her life and her career-long fight for women and equal rights.

“I think it was our persistence and her appreciation of the seriousness of our endeavor that ultimately gave her the confidence to let us in pretty close,” Cohen says. “She’s a big fan of films and documentaries and the arts in general, so she appreciates the whole notion of filmmakers. And so she kind of trusted us to make the film as we thought would be good to make it.”

Listen to the interview in the player above and read the full transcript below. Find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case, it’s–ha, I didn’t pick the title, they gave it to me. [Laughter] Betsy West–it’s an embarrassment. And Julie Cohen. And you probably know by now, they’ve made this incredible movie called RBG. It’s opening in May, going wide all over the country, it’s gotten rave reviews ever since Sundance. I’ve watched it several times, and I love it. And I want to stress, one reason I really love it, aside from, yes, it’s the great story of a fabulously committed and idealistic woman, and the times she grew up in, and her tremendous impact on the law. But what I love about it is it’s celebrating, not an older person for what they did in the past, but it’s actually getting us to know an 85-year-old woman who every–some people even said, well, why didn’t she, you know, step down, and Obama could have picked someone else. When you watch this movie, you’ll know why she shouldn’t have stepped down. She is, you know, as good as anyone ever gets. So why don’t we begin with that, and let’s just start with the fact that she’s 85.

Betty West: Well, thanks for that great intro, Robert. We’re glad that you appreciated this, because it really was very much in our mind that we’re doing a documentary about a living person who happens to be 85 years old now. And we wanted to give a complete picture of her, and not shy away from the fact that she is an older woman. The fact is that she is a legal giant for what she did in the 1970s, for equality, winning equality for women under the law. But she also now is going strong. And as an 85-year-old, she makes it a point to stay in shape. You’ve heard about her legendary workout routine, and we were lucky enough to film it. It’s inspiring; it’s something more than what Julie and I probably could have done, and has inspired us to up our routine a little bit. She, you know, lifts weights; she does planks; she does push-ups, the real push-ups.

RS: The push-ups, ah, really got me. [Laughter]

BW: The push-ups are pretty–it’s hard, the planks and the push-ups are equally–

RS: As filmmakers, and you are highly regarded, you know, filmmakers and so forth, were you surprised that you had the access that you had with this film?

Julie Cohen: Well you know, the access came very gradually. We started out interviewing former clients, people that she, colleagues from earlier in her career. We then moved ultimately to her letting us film some of her public appearances, then appearances that were a little bit more intimate. Then we moved on to, you know, close friends and family. And by the time she gave us the really special access into the gym, into her home, some time with family on vacation, or behind the scenes at the Washington National Opera, where she had a speaking role and let us film both the performance and rehearsals–you know, by the time she was giving us all that, we’d actually been working on the film for a couple of years. And I think it was our persistence and her appreciation of the seriousness of our endeavor that ultimately gave her the confidence to let us in pretty close. She’s a big fan of films and documentaries and the arts in general, so she appreciates the whole notion of filmmakers. And so she kind of trusted us to make the film as we thought would be good to make it.

RS: You know, this morning I just was glancing at some of the early reviews after Sundance, and I don’t know whether it was the Hollywood Reporter or someone–I mean, they’re all great, rave reviews. But it said something about it being a serious film, earnest and so forth. I thought it was a lot of fun.

BW: We tried, yeah, we tried to have fun with it.

RS: Well, and I was going to give, ha, the justice credit here, because she really lets her hair down. I mean, you know, in a very human way. You know, I once, I have to, full confession, I once interviewed Justice Douglas, William Douglas, in court, in the chambers and so forth. I found it really intimidating. I was there to talk to him about a book he had written, and he had you know, actually been involved in supporting politics in Southeast Asia, it’s a whole long story. But my goodness, I just found like, wow, where am I? I’m like–

BW: We had that experience too!

RS: Had an experience. And he kept it up, though, unfortunately. You know, he didn’t, you know, break it down so we could have fun or just relax. Clearly, she puts down the guard, or at least she does by the end of the film. She’s not pulling rank on you. Did she or not? I don’t know.

BW: No, she’s not. She doesn’t pull rank; on the other hand, she is intimidating. She’s a Supreme Court justice, and she is a formidable presence, despite her diminutive stature. She is intimidating. However, she is also very funny in a kind of sly, wry way we began to appreciate. And we saw that humor when we were on the road and filming these various talks. We saw her quips; she can be very funny. The best moment for us was after the interview in the Supreme Court, you know, in which we were talking about her legacy and a lot of serious issues. We then showed her some excerpts of several things to get her reaction, and at the end of that we showed her the Saturday Night Live Kate McKinnon impersonation of her. And that was an extraordinary moment, because as soon as she goes, “Is that Saturday Night Live?” Like, she wasn’t quite sure–as soon as she watched it, and Kate McKinnon is dancing–she just burst out laughing. It was quite wonderful.

RS: But it’s not a very good impersonation. [Laughter]

JC: Well, as her son points out, like, the reason, the fact that it’s not exactly a literal interpretation of Justice Ginsburg, is why it’s so funny.

BW: That’s why it’s funny.

RS: No, I’m all for that, but I’m saying, the person you introduced us to–now, maybe you got her at all her best moments–was a great surprise to me. You know, because she seemed to me, in the best sense of the word, to be accessible; to be, again, not taking yourself overly serious. And that one really had the sense that the issues she has raised and dealt with were the important thing, and not her reputation, her status. At least, that’s what the film conveys to me. Going back to when she was a college kid on up; she’s a person who did not seek the limelight, she was not bragging about anything, right? You stressed her shyness–

JC: Right, her husband did the bragging for her, and bragging about her, but she was not one to brag about herself or to, you know–she’s quiet, she’s reserved, she takes her work very seriously. But you know, after several decades in the public eye, she’s come to loosen up a bit. There’s a real, there’s a great sense of humor to her. She has some warmth, some sparkle, and some real kind of star power. And now that she’s become a rock star to the young millennials, you know, she gets a kick out of it.

RS: There’s one funny line where she’s being compared to the Notorious B.I.G. And she said well–and you ask, are you offended by this comparison. And she said, no, we’re both from Brooklyn.

JC: Right, she’s like, we have a lot in common! [Laughter]

BW: We have a lot–yeah! [Laughter] She loves that. I mean, her granddaughter talks about how she was initially surprised by her Notorious RBG persona, and how popular she was becoming with the younger generation. And her granddaughter says she kind of had a choice as to whether to recoil from it, or to embrace it. And clearly, she thinks it’s funny, and she thinks it’s an opportunity for her to reach a younger generation with her message.

RS: Well, the great thing–there are many great things about this documentary. But one of them is that you show that she comes from a real place. And you know, she has parents who probably were as bright, maybe her mother was as bright as she was, and she certainly indicates that–

JC: Yes.

BW: Yes. She adored her mother.

RS: But her mother didn’t go to college. I had a mother like that. You know, my mother didn’t even finish high school, and there was never any question in my mind that she was brighter than I was. And so you do have that sense in her fight for social justice; it’s not something that was grafted onto her. It’s something that’s in her bones. And obviously, you tell the whole story of how difficult it was for a woman to go from, to go to law school and then to go on. I mean, what, she was one of eight or ten–

JC: Nine out of, nine women in a class of 500, so. And you know, and not particularly welcomed, as women weren’t in the highest echelons of society at that time. The dean of Harvard Law School when she first entered drew together the nine women in the class, and had a nice dinner for them, and then said I’m going to go around the room and ask each of you, like, why you’re taking a place that could be held by a man. He said he meant that to kind of challenge them and get them to sharpen their legal arguments, but like, that’s a pretty rough statement to be hearing from the dean of an institution you’ve just entered, when you’re already probably a bit intimidated by it.

RS: Well, and you point out in the film, you don’t stress it, but you point out in the film that she did break through some glass ceiling very early on, and they just couldn’t deny her; she was too high-ranking, and came too well recommended. So she could have gone off to Wall Street. I mean, she could have gone into the corporate law–

BW: Well, she had some trouble initially. She graduated at the top of her class at Columbia. She was not getting the jobs at the top law firms in New York. They would just out-and-out say, we don’t accept women. So there was pushback; she then went on to clerk for a judge, and then she became a professor at Rutgers. That was where her students, in the midst of a growing women’s movement, came to her and said, look, what about a course about women and the law? About gender equity? And she started looking into it and found that there was very little casework on this. And not only that, that there was widespread discrimination with, really hundreds, thousands of laws that distinguished between the sexes and discriminated against women.

RS: I think the documentary is very good at reminding us what the world of law was like in the seventies, and the kinds of–I mean, the cases she took up, we have forgotten that there was such inequality in the workplace.

JC: People of varying generations have forgotten, or, you know, there are younger folks that just don’t know those facts at all, that don’t realize that just a few decades ago in this country, women didn’t have the same rights under law that men did. You could be denied a mortgage or a credit card if you were a woman, unless your husband cosigned for it. You weren’t considered an entity on your own. You could be fired for being pregnant. Your husband basically could rape you with impunity without there being any legal protection in the criminal codes. Like, it was a harsher world for women than it is now, as much as there’s still fighting to go, like, a lot has changed. And Ruth Bader Ginsburg is responsible for a good deal of that change.

RS: Let me ask you about Sandra Day O’Connor. Because she doesn’t get much play in your documentary, and I was wondering about that. You show that, you know, Scalia is her buddy, and they do things, and so forth. And here was the woman who preceded her. Was there tension there, or–?

JC: No, they had quite a warm relationship, and Justice Ginsburg has said that, you know, that Sandra Day O’Connor was quite happy to have Ruth Bader Ginsburg join her on the court as another woman, and sort of welcomed her in. We had other parts at some point, but you know, you’re always trying to hone down the story, and we hope that we gave her her due, visually and with a couple of mentions. Certainly Sandra Day O’Connor set a precedent as the first woman to be appointed to the Supreme Court, actually was appointed by a republican, Ronald Reagan. Ruth Bader Ginsburg followed in the following decade; when Sandra Day O’Connor retired, RBG became the sole woman for a while, and then under the Obama administration was joined by two more women justices. As Ruth Bader Ginsburg has said, you know, why couldn’t there be nine women justices? There were nine men for a number of centuries. People take that as a joke, but she may not mean it as a joke.

RS: No. Well, why should she mean it as a joke? You know, it’s a perfectly plausible statement. But it’s interesting, you also indicate her appointment was not that easy, by Bill Clinton; first of all, he had Mario Cuomo in mind; he wasn’t going for a woman at that point. And then she was considered too old. Right? How old was she then?

BW: She was 60 years old at the time. I mean, Bill Clinton, by his own admission in the documentary, tells us that he was casting about for someone because Mario Cuomo had turned him down. And it was Marty Ginsburg, Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s husband, who lobbied for her to be considered. And he talked to everyone he knew; he was a very well-connected lawyer himself, and he knew a lot of people; he was very gregarious, people really liked him. He made sure that her name came before President Clinton. Now, Clinton says, of course, yes, he was lobbying for her. But there were other people lobbying for other people, and it was her interview that did it.

RS: There’s so many interesting things about this movie, frankly. But what I found interesting, ‘cause you know, all of us have illnesses in our life. And then people think, well that’s sort of, you know, it’s over, you’re over now, you had cancer, goodbye and good luck, or you’ll come back and do a few things. This is a movie about survival.

JC: Absolutely.

BW: Yeah. Her mother dies of cancer when she’s, just on the night before she graduates from high school. Her older sister had already died when she was very young. And then her husband gets serious cancer when they’re both in law school. She’s had a lot of–

RS: She keeps him in law school.

BW: –she keeps him in law school, she marshals all of his classmates to take notes for him, she types up the notes, she’s doing her own work. Oh yes, and by the way, they had a toddler at that point that she’s also taking care of.

RS: Yeah, you sneak that into the movie, so there’s this story, how is he going to stay in law school, and she’s helping him, and suddenly this kid appears. Was that calculated? I mean, was that just sort of how she did it? Oh–we have a child. OK, we’ll work that in.

JC: No, I mean, she would tell you that actually she had serious concerns about, like, you know, once she had a baby, like wow, am I going to go to law school also, and have a kid also? This is, you know, the 1950s, where most women weren’t going to law school in the first place, let alone going to law school with a baby. Interestingly, it was her father-in-law who said to her, you know, Ruth, everyone would understand if you choose not to go to law school because of the baby, but that said, if you want to do it, you’ll find a way to make this work out. And darn it, he was right.

RS: Yeah. Well, it’s interesting, because what emerges here is really a great career role model for everybody. That–and first of all, she doesn’t make any claim that I’m every other kind of woman. She does make a claim that she can cook, and that’s disputed by her family rather viciously. And her husband steps up, you know not as some kind of comic house husband, but you know–no, I cook ‘cause I’m better at it. And I help her get organized, and I tell her no, you have to come home from work at a certain hour, and you do have to get some sleep. And he emerges as–well, you say in the film, or somebody says, as a mensch. [Laughter] But he certainly emerges as, you know, the quintessential supportive husband. And it doesn’t require any sacrifice at all of his own career, ego; you can, in some sense, have it all in this film. It means being careful about your time; Ruth Bader Ginsburg is great at managing time. She doesn’t ask for any excuses, she doesn’t ask for any delays, and she delivers all the time. She’s, you have scenes where she shows up with other justices when she’s on the appellate court; she’s already figured out the case and written the decision, they haven’t even gotten to page one. [Laughter] She has a strong work ethic. And clearly, plans to be successful and get the job done, but you know, doesn’t make a show of it, in a way. It’s just, this is what you do.

BW: Nina Totenberg says, in talking about her reaction to the death of Marty Ginsburg, which of course was devastating for her, and Nina talks about how steely she was in those days. She is steely; she is determined. She faced the death of her beloved husband by going to work the next day. She knows how to just keep going. People said to us, I think Arthur Miller said to us, you know, I was worried after Marty died, about how Ruth would react. But what she did was just kind of appropriate mourning, and then she pushed forward. As her granddaughter says, almost in honor of Marty.

RS: Well, as you point out in the film, she’s also had her own illnesses.

JC: Yes.

BW: Absolutely. Yes, two bouts of cancer. Herself.

RS: Yeah, and one often a death sentence, isn’t it?

BW: Yes, pancreatic cancer, which was caught quite early. She credits, actually, Sandra Day O’Connor with giving her advice about how to undergo chemotherapy on Fridays so that she could, you know, have her sickness over the weekend and then be back at the court on Monday. People say she did not really miss a day.

RS: [omission for station break] And I’m back with Betsy West and Julie Cohen. They’ve made this incredible film called RBG on Ruth Bader Ginsburg, it’s been–I guess it’s Magnolia and Participant Media, you got big heavyweights behind it, CNN, it’s going to have a full national opening in May. Obviously a very strong Academy Award contender; it will then be on CNN eventually. And so this is going to be much noticed, and it deserves it, I want to be very clear about that. And I want to get to something about, you know, the liberal-conservative division on the court. And you have kind of a chart going through this movie; at first she’s sort of more towards the center, and then she moves over. And towards the end, she then denounces Trump during the campaign, and that really raises some questions about where she [is]. But what I thought was quite interesting was her decision to go work for the ACLU, which was, I mean has been, a controversial organization–for good reasons; they take a very principled stand in support of the First Amendment. But I was wondering, did you explore that? Remember Michael Dukakis, when he ran for president–I had interviewed him, actually, for the LA Times–and he said, I’m a card-carrying member of the ACLU. That became an issue in the campaign. Did she discuss–’cause a lot of lawyers, male or female, interested in a big career, would not have gone to work for the ACLU.

BW: Do you think at that time, in the early 1970s, it was as toxic as it later became after the culture wars? I think when she did it, the ACLU was developing the Women’s Rights Project, and it seemed like a logical thing for her to do. Whether or not later on the association, you know, became in any way problematic–although it was not problematic in her confirmation hearings; it really wasn’t raised that much.

RS: I’m not saying it should ever have been problematic. But I mean, no, because the ACLU was associated with the Fred Korematsu case, with the Japanese internment; they took on McCarthyism. And in your film, you have Ruth Bader Ginsburg, you know, really alarmed by McCarthyism, and–

BW: Yes. As a motivation for her own, you know, involvement in the law. That’s when she thought, hey, lawyers can do something good.

RS: Right, so I’m trying to get at her outlook. And it seems to me, you know–it’s funny, because right now there’s a lot of pressure in colleges, your career, career, career, and what are you going to do and how are you going to make a living. And here is clearly one of the most successful human beings in our history, coming from a meager, poor background, getting to the top; you know, she’ll be always remembered in any historical account of America and so forth. And she, it seems to me, did it without blatantly pursuing career.

JC: Right. I mean, I certainly think when she went and took the job with the Women’s Rights Project at the ACLU in the early seventies, that she did not have a Supreme Court seat in her mind at that point. I think, you know, she’s strategic about her pursuit of equal rights under the law, but I don’t think she was that much of a careerist. She just saw an opportunity to work on an issue that she thought was really important; she saw a place that was willing to commit some resources to it, and she decided to join forces with the individuals who were ready to, you know, put their money where their mouths were on the issue of equal rights for women under law.

RS: She didn’t just take one or two cases. And her argument for going to the ACLU, as a law professor working, is they wanted to take over these cases. Your film is very smart about that, that people had complaints–we could mention some of these, you know; a military person who was held back–

BW: Can’t get benefits that a man would get. Those kinds of inequities.

RS: Right. And she, very carefully, actually picked these cases–that’s what the ACLU does. I’m a big, I’m a card-carrying member of the ACLU [Laughter], I’m a big fan. But what they do is they’re trying to make law, they’re trying to get precedent.