Chris Hedges's Blog, page 568

June 3, 2018

Advice to College Graduates in the Trump Era

Class of 2018, I’ve always been told that a joke’s a good way to launch any talk. It’s a matter of breaking the ice, though on your graduation day, with the temperature soaring into the upper eighties, that may not be the perfect image. Still, you know what I mean: an attempt to lighten the atmosphere a little before getting to the tough stuff. Again, though, in our world — in case you hadn’t noticed, a near majority of American voters elected Donald Trump president in November 2016 — lightening the atmosphere may pass for a joke in itself (and I do think I hear a little laughter out there somewhere).

Anyway, here’s my official joke on this sunny afternoon in the middle of this beautiful open campus quad. Ready?

Bang, bang, I’m dead!

No, really, in our present world, shouldn’t that pass for a joke? Think of it as my way of making light of a grim reality of your educational lives. After all, imagine some classmate of yours, angry at, well, who knows what, or simply, as new head of the National Rifle Association and former illegal gunrunner Oliver North suggested recently, on Ritalin and devoted to violent video games, stalking onto this very campus this very afternoon. He’s — and it almost certainly would be a “he” — spoiling for payback of some sort and he’s — who could doubt this in twenty-first-century America? — armed to the teeth with lethal, possibly military-style weaponry. The odds are that, standing up at this podium in front of you as he began blowing people away, I might well be the first to go. Hence, my joke! But of course you got it, didn’t you?

The Adults Under the Desks

To be clear, on your graduation day I’m not just kidding around. I’m also doing what the truly old — I’m almost 74 — always try to do: somehow get in the spirit of the young just about to step into, not out of, our world. It’s true that when I went to school back in the Neolithic Age, we had our own version of being blown away — and of active-shooter drills and of the fear of dying that went with them.

From the time we were little, we were, in the parlance of that moment, “ducking and covering”; that is, diving under our school desks for protection with our hands over our heads like (as one civil defense cartoon of the time had it) Bert the Turtle going into his shell. We were protecting ourselves against a nuclear attack from a land you won’t even remember, the former Soviet Union, which imploded before you were born (R.I.P. 1991), aka the Ruskies, the Evil Empire. And yes, looking back, those tiny kids crouched under those desks, one of whom was me, couldn’t have represented a more pathetic image of “safety” or, to use the word that has dominated this American century, “security.” And yes, even as children, we knew it. The underside of a desk and your hands were no defense against the atomic bombing of New York City (where I lived in those years, as I do today). In fact, you have to wonder what sad group of adults came up with that brilliant strategy for terrorizing children?

Those were the active-shooter drills of that particular lockdown moment, us under those desks as CONELRAD blared its warnings from a radio on the teacher’s desk and sirens howled in the streets outside. Even at a ridiculously young age, you knew that you, your parents, your grandparents, your friends might not be around for long if that particular shooter, the Soviet Union, made it into your world. Its “shot” would, of course, have been heard not just in that classroom but around what was left of a nuclearized world. So, believe me, whatever your nightmares about mass shooters in your schools may be, we had them, too.

On the cheerier side, in the present moment, nukes, thanks in part to a president who likes things BIG, are clearly making a bigly return in our present world. Since the Obama years, more than a trillion dollars (a number sure to rise) have been slated to produce yet more of them in even more usable versions for what’s already a staggering arsenal, one that could easily obliterate several Earth-sized planets. We’re talking about an arsenal that our president referred to hair-raisingly just last week while canceling his summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un: “You talk about your nuclear capabilities, but ours are so massive and powerful that I pray to God they will never have to be used.” That, of course, is the very same arsenal with which he had previously threatened to bring “fire and fury like the world has never seen” down on North Korea.

Now, in these years, as you’ve crouched silently in the darkness of some classroom, preparing for the moment when a well-armed student or former student might be roaming the halls of your school preparing to shoot you down, your own set of fears have been far more up close and personal than mine were, but no less horrifying. The New York Times recently reported on a high school, 1,000 miles from the latest mass school slaughter in Santa Fe, Texas:

“Calysta Wilson and Courtney Fletcher, both juniors at Mount Pleasant Community High School in Iowa, believe their table in the cafeteria would be the first one a gunman entering the room would target. ‘We sit at the table closest to the doors,’ Calysta, 17, said as she took in a softball game. ‘In the case that you came in as a shooter and you killed the first person you saw, I would die. I would not make it.’”

Here is where I feel oh-so-old standing in front of you today. I can’t even imagine such calculations as a daily part of anyone’s education. For the Texas versions of Calysta and Courtney, however, that state’s lieutenant governor, Dan Patrick (who’s pushed for bringing concealed weapons to church), does have a solution: more guards, fewer school entrances (“There are too many entrances and too many exits to our over 8,000 campuses.”) — or, as the wags had it, “Guns don’t kill people, doors do.”

Let’s face it, though, Patrick is hardly a loner when it comes to such solutions to society’s problems. Since the Parkland, Florida, school slaughter sparked a movement to curb guns in America, calls for the the further arming, fortifying, and militarizing of American education — from the NRA to President Trump — have come thick and fast (even if the insurance companies have balked, doubting that armed schools will be safer places). And Patrick’s solution is very much in line with our moment more generally. It fits perfectly, for instance, with the president’s famed response to “Mexican rapists” and other imagined dangers to the nation: Wall them out and wall us in. (In the background, can’t you hear Trump’s base at his rallies chanting “build that wall!”?)

To offer a little perspective on your world of walls to be, they simply don’t work. Not for long anyway. The 4,500-mile Great Wall of China may still be the ultimate symbol of such construction (even if not actually visible from outer space), but the “barbarians” from the steppes of Asia still managed to invade and establish their dynasties in the Chinese heartland. In America, the walling in of education, the turning of schools into no-exit fortresses, will hardly solve problems. Consider, for a moment, the simple fact that school-age children gather in other places as well — coffee shops, fast-food restaurants, gyms, you name it. Are you really going to fortify the entire society, put guards and guns at every McDonald’s? And are you really going to turn American “education” into a fully armed experience? In other words, will an education that, theoretically at least, is supposed to “open” you up to the world, actually leave you desperately closed off from and pre-terrorized by it (even though school still remains the statistically safest place for a child to be in this society)?

In fact, exercises like the full-scale fortifying of schools are really the twenty-first-century adult equivalent of ducking under a giant desk and putting your hands over your head. Sad!

The reality of this moment is that what truly endangers us — and especially you, the graduates of 2018 — can’t possibly be walled out (or in). I hate to tell the lieutenant governor of Texas this, for instance, but when it comes to the planet itself, unlike Texas’s schools, we can’t easily create fewer exits (not certainly in the age of the Sixth Extinction) or arm the guards better. That’s why climate-change denial — the greatest form of ducking and covering around — is so convenient. It means you can ignore (for now) the single greatest threat on the planet (other, perhaps, than nuclear weapons) that can’t be walled in or walled out. But more on that momentarily, as I throw further shadows over this glorious day of yours.

Here, then, is an entrance-and-exit reality to start with: you can’t arm a citizenry like no other on the planet (Yemenis come in a distant second) and then successfully wall yourself off from that reality with fewer entrances and yet more arms. You can’t let more than 300 million weapons loose in a single country, including millions of military-style assault rifles, as if preparing for a future war at home and expect nothing to happen. (It’s hardly surprising, under the circumstances, that this country leads the world by a long shot in what are politely called “mass shootings.”) You can’t arm your police nationwide with weaponry and other equipment directly off the distant battlefields on which your armed forces have been fighting for almost 17 years, or fill their ranks and their SWAT teams nationwide with veterans off those very same battlefields who used those very same weapons and expect nothing to change.

You can’t fight wars for more than a decade and a half, still spreading in those same distant lands, and not expect them to come home somehow, even if in the fantasy figures of terror-minded refugees against whom you plan to build those walls and institute those travel bans. You can’t have a Washington in which in 2003 and again in 2018 — despite everything that’s happened in the years between in the Greater Middle East — “real men want to go to Tehran” and successfully wall yourself off from the results of that urge. You can’t expect all of that and not also expect that somehow or other this will, to use the title of my new book, turn out to be a nation unmade by war.

There are no walls, no entrances or exits that can be closed in order to contain the damage from or protect the American people from Washington’s destructive follies.

Heading for the Entrances, Not the Exits

Think of it as an irony of the first order that, in the face of historic dangers, the American people sent a man into the White House ready to create an administration that would give the classic head-in-the-sand cartoon ostrich a run for its money. Yes, Donald Trump did once claim that climate change was a “Chinese hoax,” but who could have imagined that he would consciously staff his administration with the most wide-ranging set of climate-change deniers imaginable; or that he and his cronies would put so much effort into the further fossil-fuelization of the Earth; that, while bragging about building walls and instituting travel bans to protect the American people, he would put his greatest energy, focus, and effort into creating ever more of the most destructive kind of “exits” and “entrances” on this planet?

After all, everything else we might discuss today from those endless piles of weaponry in this country to the strange potential autocrat now in the White House is just part of ordinary human history in which empires and autocrats rise and fall; people rebel and fail, die and suffer, and Kim Jong-uns run their countries until they don’t. Climate change is nothing of the sort. It operates not on a human time scale, but on an awesomely different one, a planetary one. Note, for instance, that, according to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, every one of the last 400 months (since the presidency of Ronald Reagan) has been warmer than the historical norm and 16 of the last 17 years since 2001 have similarly been the warmest on record. Just a hint of what’s coming.

Climate change functions on another time scale entirely, one that puts human time in grim perspective. So whatever the horrors and crimes of the present moment, the greatest of them all (except nuclear destruction) is undeniably aiding and abetting in the future warming of the planet, a phenomenon sparked by us and yet not likely to end on a human time scale. In other words, if President Trump and his crew have their way, they will prove to be true terrarists (rather than terrorists), the greatest criminals in human history. They will have consciously chosen to aid and abet the destruction of the very environment that nurtured humanity all these centuries. They will have been the shooters in humanity’s schoolyard.

All of this means that all of you, all of us, are now living with a version of the apocalypse up close and personal, whether we fully grasp that or not, in part because this potentially apocalyptic moment will play out over hundreds, even thousands of years. And that’s no joke.

It may, by now, be crossing your mind that it would be better not to graduate at all from this beautiful school. Instead, why not close and lock that giant gate over there, fortify this campus, and hunker down for the human version of eternity, or simply crawl under your chairs right now, in the midst of this ceremony, put your hands over your hands and refuse to come out.

But perhaps I could suggest something else for you, class of 2018. Perhaps now is the perfect moment for you, your parents and grandparents, your friends and relatives to stand up, form yourselves into your serried ranks, gowns on and caps in hand ready to be tossed. Perhaps now is the moment to stand tall, be proud, and head for one of the very exits to this campus, which are really entrances to our world — of the sort that so many are so eager to shut down and armor up. Perhaps now is the moment to begin your procession off this campus into a world where the entrances and exits should be opened, not closed, and things should truly be so much better than they are. Now is the time to enter our beleaguered world and go to work. We need you, class of 2018, not under some desk but out there ready to change our world for the better.

Truthdig is running a reader-funded project to document the Poor People’s Campaign. Please help us by making a donation.

June 2, 2018

Not a Paying Customer? Go Shit Somewhere Else.

Decent public bathrooms, and for that matter, public showers, ought to be free in all our cities and larger towns. That would be just one elementary kind of social democracy in this country. If we can afford endless wars and public bailouts for a rogue regime of banks and corporations, we can surely afford toilets, soap and water for we, the people.

Slaves gained freedom from masters, women gained freedom to vote, gay people gained freedom to marry in legal equality—or to refuse the legal bonds of marriage while still defending social equality beyond marriage. So all of us can still improve our public life. We would all gain in public relief of common animal needs, and it would not reduce our full humanity even by a fraction.

Megyn Kelly, however, thinks otherwise. Her tinsel star has risen from the depths of Fox News to the heights of NBC. After the April 12 arrests of two young black men in a Starbucks in Philadelphia, after nationwide protests and threats of a boycott, and after Starbucks suspended business for employee training sessions, Kelly was roused to a righteous cause: namely, defending the right of paying customers—and only paying customers—to use Starbucks restrooms.

The manager in the Philadelphia incident, who has since been fired, told the two men they could not use the restroom without buying a product. They chose to sit and wait for friends at their table, and the manager called the cops. They did not resist arrest, which was recorded and widely broadcast. Neither of the men looked like they had been sleeping rough on the streets, and they kept their dignity and composure.

Kelly made a fast and racist leap from these two gentlemen to a fantasy of a mob of homeless, diseased and addicted people crossing the class barrier to use restrooms in upscale coffee shops—because race is one of the habitual ways we live out the class system in this country. I must note that Philly was my home for decades, and I lived a short walk from where that Starbucks now does business.

As noted in a 2018 report on this country’s most segregated cities:

“Today, about 43% of the City of Brotherly Love’s population lives in a racially homogeneous neighborhood, about 10 percentage points higher than the average across the 100 largest U.S. metropolitan areas. Of the city’s black population, 15.6% both earn poverty wages and live in high poverty neighborhoods, compared to less than 1% of the city’s white population.”

That’s the reality for black Philadelphians. The predictable Fox News editorials could be printed on endless streams of toilet paper, except we now get this particular message from the classier neighborhood of NBC. Exercising her right to fill living rooms with cascades of caca, and to turn each news cycle into a theater of the absurd, Kelly recently opined on her “Today Show” program:

“They’re allowing anyone to stay and use the bathroom even if they don’t buy anything, which has a lot of Starbucks’ customers saying, ‘Really?’ ”

Really? We might wonder whether Kelly pulls that kind of stuff out of her butt. Only in passing did she raise a question about the way we divide private and public space into private and public property. Kelly is a mouthpiece for a dominant ideology, and this alone makes her comments worth our time. Her question was rhetorical; she had already answered it:

“Because now the Starbucks are going to get overwhelmed with people, and is it really just a public space or is it not?”

Let’s take her question seriously, because in some cases, the answers will not be simple. But in other cases, we have legal precedents and even federal laws that were not simply gifts of goodwill from Congress and the Supreme Court but were won through long periods of class struggle and through social movements involving civil resistance against racism. A private business still has a general right to refuse service to people who are disruptive or dangerous, but not for reasons of race, sex, age and disability. Sexual orientation and gender identity are protected only in some places.

Kelly is not worried that a small, independent coffee shop in a working-class neighborhood might get “overwhelmed with people” of the wrong kind. She is in a panic precisely because the Starbucks brand is an upscale lifeboat of good taste and good manners, especially when the classy Titanic has already struck the iceberg. She deserves one of those lifeboats and assumes most people of her class do, too. Her world is rocked by the swift decision of Starbucks executives to compromise with people she regards as a potentially dangerous mob. Even Jenna Bush Hager argued the case for kindness on Kelly’s program and said her local Starbucks gives a break to a few homeless people.

Kelly was not persuaded, and suggested that churches exist to provide that kind of charity, not a big chain of coffee shops. She did not suggest that a corporation might choose the philanthropy of providing housing for the homeless, or just clean toilets and showers for anyone who can’t afford a $5 cup of coffee. Kelly continued:

“And it’s a question about whether a commercial establishment is that place. … For the paying customers who go in with their kids, do you really want to deal with a mass of homeless people or whoever is in there—could be drug addicted[. Y]ou don’t know when you’re there with your kids paying for the services of the place.”

That division of labor between unreliable philanthropy and unreliable charity never really gets spelled out. Our class divisions never truly get mapped as a social minefield for the poor, the jobless, the low-wage workers and the outright homeless. The richer white folks are likelier to regard the trenches of class division as flyover country as they dine and shop in ascending degrees of class distinction.

Private and public places must remain contested territory when private property is open for business to the general public. When and where there may be doubt, Kelly defends the right of proprietors to draw their own line and tell unwanted members of the public to get out.

If we deprive some people of secure and well-maintained bathrooms open to the general public, then they are forced to use bathrooms of businesses such as Starbucks—or else use streets and parks, and risk dealing with cops. This problem won’t go away, any more than the poor and despised can be wished out of existence. Not in a wealthy country whose gross domestic product includes the homeless and the crap we encounter on streets, parks and beaches.

Sure, there is the issue of tax dollars and public funding. God forbid we should flush our hard-earned money down a public toilet. Public bathrooms would require real public funding and workers with living wages. If we want the dirty, despised and even dangerous jobs done for the public good, then the public must be good enough to pay for jobs well done. Corporate executives are lauded as “job providers,” so why oppose the opportunity to hire security and maintenance staff for public bathrooms beyond private businesses open to the public?

We should worry much less about rapists, criminals and terrorists swarming over our borders and show much more respect to migrant workers. Indeed, those workers also deserve safe housing and clean bathrooms in fields and factories. That respect must extend to people in trouble, those who may not be able to hold a job due to all-too-human problems such as homelessness, mental illness and addiction.

That much—and, let’s be real, that little—does not require a nation of saints, or even a nation of social workers. It does not require a lockstep march backward under Soviet central committees, nor a lockstep march into a future of technocratic totalitarianism. Our choice is not between an out-of-date Kremlin and an up-to-date Davos. We are not talking about some utopia far over the horizon, but about common decency, here and now.

The whole cost could easily be paid by taking a fraction from the vast and unaccountable military budget. A few of the more honest public servants admit that trillions of bucks go mysteriously missing. Yes, trillions, not just billions. See Lee Camp’s report, published recently by Truthdig.

I remember the days when people with AIDS carried maps of places we could go in an emergency to use the toilets. Beelines or bust! Some of us did our best with adult diapers, because diarrhea was a fact of our lives, especially with the harsher early meds. This remains a fact of life for many other people with chronic health problems—just in case you care to distinguish between the diseases of respectable people and the diseases of social pariahs. And if you think you can catch AIDS from toilet seats, catch up with the science.

In our great meritocracy, some people merit toilets away from home (assuming they have homes other than tents and streets and underpasses), but not others. Not those others who may be drifters, whores, junkies, crazies or the riffraff who are barely toilet-trained. That amounts to a public policy of cruelty and deprivation and turns workers behind counters into agents of social hygiene. After all, to keep their jobs they may be following orders from their bosses, who in turn can always claim they put customer comfort and public safety first.

Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness? Oh, perishing republic! Irony too heavy? Don’t blame the messenger. Our crappy public life has certain rules, as strict as the etiquette at the court of Versailles under the divine right of kings.

In fact, those powdered and bewigged courtiers had few places to relieve themselves at public events in the Palace of Versailles, and they often did their business in stairwells. If they were lucky, they could find a servant to fetch a chamber pot, or else take a piss in the fabulously manicured gardens. The aristocratic stench grew so strong that King Louis XIV commanded the hired help to sweep out the shit at least once a week and protect the precious potted orange trees from being used as pissoires. Don’t take my word for it; check out a bit of history here. The servant problem in France continued under the following royal regimes and was one factor in the French Revolution.

Let’s not pretend that class consciousness is the mark of Cain only for the proles and the underworld, because our rulers demonstrate that they are highly class-conscious in their own right, from the commanding heights of wealth and power. Nice to have the public order spelled out by an expensively groomed talking head on TV.

Back in the last decade of the 20th century, the growing number of women in Congress forced that boys’ club to add more restrooms for their newly arrived female colleagues. Of course, now we have the raging battles over the right of trans people to use the bathrooms of their choice, which has become a new line drawn in the sand by cultural warriors against the gender-benders. A rising tide of common sense will wash that line away.

A very few open socialists and a few sturdy women in Congress could tackle this issue as a small reform in public policy. They would be up against a bipartisan consensus that would favor turning this reform into yet one more “public/private partnership.” Starbucks stirs up the recent round of arguments, but it was forced to change company policy by public threats of boycotts. Let’s not get stuck in praise of the CEO’s apology and the limited change in business as usual. That misses all the bigger issues. Entirely.

“Public/private partnerships” are a neoliberal nostrum. Private profits will still be extracted, even from public toilets in private businesses, and private profits can even be extracted from civic plans to fund and maintain public bathrooms in the public sphere. If the public pays only a dime per crap, then someone would still be eager to extract their 10 percent from every flush. Some shiny new startup in Silicon Valley could even provide Congress with the data required to nickel and dime the public for each bar of soap and each roll of toilet paper. Unless it’s entrepreneurial, it’s not American.

To hell with that. We’re taking about a public commitment to a public service. Every such small reform also requires this simple public demand on the very rich and the corporations: “Pay Your Taxes.” If we, the people, are serious about that demand, we need a national tax plan scaled to real incomes and profits.

One thing leads to another, as the career pols always caution the public, and we would then be on the slippery slope to socialism. This is all too familiar from old debates between capitalist economists. John Maynard Keynes, for example, proposed mild reforms to save capitalism from recurrent catastrophes. They worked, more or less, for a time. The “libertarian” economists weren’t buying it though, because their first concern was the unregulated liberty of capitalists. For that reason, Friedrich Hayek wrote “The Road to Serfdom,” a polemic against the Keynesian program. Never mind that capitalism creates millions of up-to-date serfs and armies of toilet-trained wage slaves. Those who do not rise on the wheel of fortune must go under and be crushed.

The usual “public/private partnership” schemes do not go to the root of divisions in capitalist ideology and in the built environment we take for granted as an act of God. Starbucks, before and after the news cycle and busted attention spans, has provided one useful corporate example of a small, neoliberal policy change. And that is all. This example directly concerned two black men and reflexive racism. So we must remember the sit-ins at lunch counters during the civil rights movement of the previous century, when black people dared to order cups of coffee under a Southern Jim Crow regime. After arrests and public storms, Supreme Court decisions finally laid down the law. A privately owned business serving the public cannot, in fact, reserve a sovereign right to deny service to people of color. Otherwise, we may have a republic of racist private profiteers, but not a democracy worthy of all citizens.

If we want fully funded public services, we are talking about basic social democracy and radical reforms. Not just about corporate decisions made from the top down, however philanthropic they may be. And not just about faith-based charity. This country has plenty of churches, but not nearly enough to provide public toilets and showers to people in trouble. More to the point, she has only a vague notion of this nation’s racial history and the hard-won gains in legal and human rights.

Business owners recently surveyed in Costa Mesa, Calif., opposed a measure to provide public bathrooms to the homeless by 80 percent. This is a not-in-my-backyard reflex, bound, in this case, to giving a thumbs-down to any rise in taxes. In fact, public bathrooms would mean that many fewer homeless people would be using their business bathrooms. If public bathrooms create jobs for security and maintenance staff, as they surely should, then any tourists to the city would also be better served. After the initial cost, that means a rise in overall revenues to Costa Mesa.

Sure, some people just want the homeless gone. Well, warmer climates will draw from colder climates a higher number of people in trouble. I once lived and worked in Key West, Fla., and observed a similar problem, though on a much smaller scale. Here’s the deal: Some cities and states to which the homeless migrate in high numbers are either tackling the problem with common sense and compassion, or they are retreating from reality and hoping to build Trump’s “beautiful wall” in their own backyard.

The towns and cities that struggle to provide basic goods and services to the middle class may feel no responsibility to the poor at all. Civic budgets are burdened by the consequences of crony capitalism and the corporate command economy. Roads, tunnels, bridges and even public water systems are breaking down around the country, and a federal jobs program to upgrade our infrastructure should be part of a 21st-century New Deal.

Some of those jobs would lift the jobless from homelessness, though we also need a truly public health care system, including programs that meet alcoholics and addicts where they are. Brick-and-mortar neighborhood clinics deserve support, but mobile bathrooms and primary care vans are also necessary. When progressive city councils step up to such responsibilities, they deserve praise. But those cities should not be subsidizing the irresponsibility of other public officials who just hope people in trouble take the next bus out of town.

Los Angeles has one of the worst and biggest skid rows—and homeless encampments scattered throughout surrounding areas—in the nation. Near my home, I pass by tents and cardboard boxes that may be a small refuge for people in trouble. We have to stop looking at their makeshift homes as mere litter-boxes, because some take pride in keeping their areas neat and clean. Sometimes I stop and talk to these people and offer a few bucks or some food. Not all accept, and a few let me know a handout is beneath their dignity. They have a point.

And because I am not a saint or a professional revolutionary, I can only make the smaller efforts to remain human. I joined small groups back in Philly that founded clean-syringe and harm-reduction sites on city streets for injection-drug users, and others of us were pitched in police vans when we demanded housing for the poor and homeless. Sure, I recommend civil disobedience, but that is just one item in our toolkits for change. We can also vote against reckless and irresponsible career politicians. Still, even basic democracy now requires a social revolution in this country. We can judge “public/private partnerships” case by case, but they can do more good for private interests than for the public. Basic social democracy will not be heaven on earth, but other countries practice common sense and have a public record of common humanity in their public policies. That is not the road to serfdom, but rather the way to a genuine commonwealth.

We need local programs to house and help the poor and the homeless. We also need a national commitment to end structural poverty, and we need federal protection of people who are too often considered throwaways. Everyone deserves a chance and a choice to get the hell out of town if their families and neighbors offer no help at all or treat them as people who deserve a scarlet letter. We will need federal funds and laws so more of the homeless can find homes closer to kin and places of origin, and federally funded job programs for those able to work. This was one of the success stories during the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the New Deal was one kind of social democracy. We can do better now. The devolution of the homeless problem in the 50 states means we are not, in fact, the United States. Not on this issue, and not on many others.

Hey, there ought to be a law, right? As Auden once noted, “We are still barbarians.”

In Hawaii, Trauma Follows Shock and Loss

One harrowing month into the eruption of Kilauea volcano on Hawaii’s Big Island, the community’s social fabric is being strained by a daily barrage of shock and loss.

On May 3, the ground split open in the Puna district community of Leilani Estates and lava began to explode from a line of two dozen fissures. The next day, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake shook the island and the first of 87 homes, at latest count, was incinerated by lava. Livelihoods have been lost as at least 4,000 acres of agricultural land have been inundated and the tourism industry takes a major hit.

The normally laid-back people of Puna are showing increasing signs of trauma:

● In lava-devastated Leilani Estates, a man faced a string of charges Wednesday after allegedly shooting at a neighbor.

● Another Leilani resident defied police instructions to stay out of the evacuation zone and, apparently intoxicated, crashed his pickup truck into a wall of lava that had hardened across a closed section of highway. He was arrested Thursday.

● A man registered at one of the island’s evacuation shelters was found dead in a wooded area near the shelter, an apparent suicide. Police said he was despondent after the breakup of a romantic relationship.

For disaster-weary Puna, there’s no end in sight. Several fissures are still spewing great volumes of lava, and one—known as Fissure 8—is fueling a rapid new flow to the ocean.

On Thursday, more areas of hard-hit Leilani Estates faced mandatory evacuation. Authorities worried that a swollen lava channel could breach its banks.

On Friday, the residents of two more communities, Kapoho Beach Lots and Vacationland, were given hours to get out or be isolated by a fast-moving lava flow front that has grown to 300 yards wide. The flow crossed the area’s last road to safety Saturday morning.

In the past week, lava claimed more of the Puna Geothermal Venture plant, which supplied 20 percent of the island’s energy until it was abandoned as the flow approached—exacerbating the island’s problems. The plant has faced opposition since its inception in 1989: Neighboring residents have long feared that a potential lava inundation could cause an uncontrolled release of dangerous hydrogen sulfide gas, although emergency management officials consider that scenario unlikely.

As if the eruption wasn’t destructive and scary enough, Hawaii island is dealing with other torments with intriguing names: vog, laze and Pele’s hair.

Vog is sulfur dioxide-laced volcanic fog. (Sunday’s vog level in Puna and the Big Island’s southwest is predicted to be hazardous.) Laze is lava haze, which forms when lava enters the ocean and is a poisonous brew of hydrogen chloride and tiny slivers of glass. Pele’s hair, named for the volcano goddess Pele, is the eruptive fallout of fine strands of volcanic glass.

All these put downwind communities at risk, as does volcanic ash, which has been regularly exploding from the crumbling Halemaumau crater at the Kilauea summit. Borne on prevailing trade winds, the ash is coating the towns of Volcano and Pahala and Kau district neighborhoods. The latest in a swarm of earthquakes associated with the summit explosions measured 5.4 Friday.

More than 400 residents are in emergency shelters; some have been displaced for as long as a month. A number of organizations, including Habitat for Humanity, the Salvation Army and United Way, are accepting donations.

The shelters have been busy offering mental health counseling to those in need. Emergency personnel are stretched to the breaking point dealing with the ever-changing conditions.

“It’s almost like your life is on hold,” said Leilani Estates evacuee John Davidson. “It’s not like it’s a hurricane where you think, ‘OK, in three days it’ll be here and go.’ … This is almost like a slow-motion train wreck.”

Truthdig is running a reader-funded project to document the Poor People’s Campaign. Please help us by making a donation.

Wall Street’s Biggest Banks Must Be Broken Up

On Wednesday, Federal bank regulators proposed to allow Wall Street more freedom to make riskier bets with federally-insured bank deposits – such as the money in your checking and savings accounts.

The proposal waters down the so-called “Volcker Rule” (named after former Fed chair Paul Volcker, who proposed it). The Volcker Rule was part of the Dodd-Frank Act, passed after the near meltdown of Wall Street in 2008 in order to prevent future near meltdowns.

The Volcker Rule was itself a watered-down version of the 1930s Glass-Steagall Act, enacted in response to the Great Crash of 1929. Glass-Steagall forced banks to choose between being commercial banks, taking in regular deposits and lending them out, or being investment banks that traded on their own capital.

Glass-Steagall’s key principle was to keep risky assets away from insured deposits. It worked well for more than half century. Then Wall Street saw opportunities to make lots of money by betting on stocks, bonds, and derivatives (bets on bets) – and in 1999 persuaded Bill Clinton and a Republican congress to repeal it.

Nine years later, Wall Street had to be bailed out, and millions of Americans lost their savings, their jobs, and their homes.

Why didn’t America simply reinstate Glass-Steagall after the last financial crisis? Because too much money was at stake. Wall Street was intent on keeping the door open to making bets with commercial deposits. So instead of Glass-Steagall, we got the Volcker Rule – almost 300 pages of regulatory mumbo-jumbo, riddled with exemptions and loopholes.

Now those loopholes and exemptions are about to get even bigger, until they swallow up the Volcker Rule altogether. If the latest proposal goes through, we’ll be nearly back to where we were before the crash of 2008.

Why should banks ever be permitted to use peoples’ bank deposits – insured by the federal government – to place risky bets on the banks’ own behalf? Bankers say the tougher regulatory standards put them at a disadvantage relative to their overseas competitors.

Baloney. Since the 2008 financial crisis, Europe has been more aggressive than the United States in clamping down on banks headquartered there. Britain is requiring its banks to have higher capital reserves than are so far contemplated in the United States.

The real reason Wall Street has spent huge sums trying to water down the Volcker Rule is that far vaster sums can be made if the Rule is out of the way. If you took the greed out of Wall Street all you’d have left is pavement.

As a result of consolidations brought on by the Wall Street bailout, the biggest banks today are bigger and have more clout than ever. They and their clients know with certainty they will be bailed out if they get into trouble, which gives them a financial advantage over smaller competitors whose capital doesn’t come with such a guarantee. So they’re becoming even more powerful.

The only answer is to break up the giant banks. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was designed not only to improve economic efficiency by reducing the market power of economic giants like the railroads and oil companies but also to prevent companies from becoming so large that their political power would undermine democracy.

The sad lesson of Dodd-Frank and the Volcker Rule is that Wall Street is too powerful to allow effective regulation of it. America should have learned that lesson in 2008 as the Street brought the rest of the economy – and much of the world – to its knees.

If Trump were a true populist on the side of the people rather than powerful financial interests, he’d lead the way, as did Teddy Roosevelt starting in 1901.

But Trump is a fake populist. After all, he appointed the bank regulators who are now again deregulating Wall Street. Trump would rather stir up public rage against foreigners than address the true abuses of power inside America.

So we may have to wait until we have a true progressive populist president. Or until Wall Street nearly implodes again – robbing millions more of their savings, jobs, and homes. And the public once again demands action.

Truthdig is running a reader-funded project to document the Poor People’s Campaign. Please help us by making a donation.

American History for Truthdiggers: Liberty vs. Order (1796-1800)

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 10th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 10 of “American History for Truthdiggers.” / See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9.

* * *

“Liberty, once lost, is lost forever.” —John Adams in a letter to his wife, Abigail (1775)

“[A social division exists] between the rich and the poor, the laborious and the idle, the learned and the ignorant. … Nothing, but force, and power and strength can restrain [the latter].” —John Adams in a letter to Thomas Jefferson (1787)

Two quotes from the same person. Barely a decade between the two utterances. How can a man be so conflicted? John Adams, who helped lead the revolution against British “tyranny,” would later become a president apt to suppress dissent and restrict a free press at home. Well, Adams was a complicated man, and the United States was—and is—a complicated nation.

As John Adams succeeded the quintessential American hero, George Washington, becoming the second president of the United States, division pervaded the land and a debate raged in both the public and private space: Shall we have liberty or order? Could a people expect a measure of both?

Adams, though an early patriot leader and the nation’s first vice president, had neither the notoriety nor the unifying potential of a George Washington. And he knew it. Ill-tempered, insecure and highly sensitive, Adams appeared unsuited for the difficult task at hand. The body politic was fracturing into opposing factions—his own Federalists and the Jeffersonian Republicans—while the country itself was swept to the brink of war, first with Britain and then with revolutionary France.

Looking back, the ending seems preordained: Of course the republic could never have failed, we are prone to believe. Only this was far from a certainty, and the outcome was a near-run thing. America nearly came apart in the crisis of 1798-99.

Divided at the Onset: Republicans, Federalists and Conspiracies Against Liberty

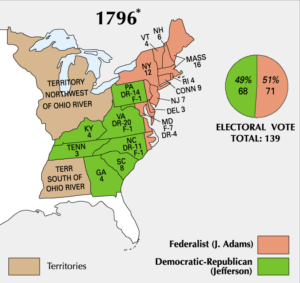

An Electoral College map of the 1796 election.

Even a quick glance at the electoral map from 1796 demonstrates not only how close was the contest, but how divided were the various regions. Indeed, even in this first truly contested election (Washington’s two terms seemed predestined) one notes an emerging sectional division between a Federalist North and a Republican South. Remember that this was an era in which most Northern states had begun to phase out slavery, whereas the South developed an increasingly slave-dependent society. The Federalists dominated in the North, especially along the coast. John Adams was a Massachusetts man, Jefferson a Virginia planter. The division is striking—as though the next century’s Civil War was fated from the start. It wasn’t, of course; nothing truly is, but no doubt the seeds were there at the onset.

The North, in addition to having a smaller enslaved population, was highly commercial and increasingly urbanized. The South remained an agrarian slave society. Still, slavery was not the main division in the second half of the 1790s. Liberty itself was the defining concern—liberty’s exact contours and the limits of dissent.

Not that the election of 1796 bore much resemblance to our modern contests. Both candidates stayed home, neither actively campaigned and each left it to friends, allies and sympathetic newspapermen to make their respective cases. Nonetheless, Adams and Jefferson—once and future friends—epitomized exceedingly divergent governing philosophies.

Adams lacked the vigor and extremist positions of some Federalists (notably Alexander Hamilton) but believed fervently in the need for a strong, central government to calm and control the tempers of the states and the public alike. Once an ambassador in London, he tended to favor the British in their ongoing worldwide war with France.

Jefferson, conversely, distrusted centralized power and never overcame his youthful revolutionary hatred for all things British. It was Jefferson, recall, who remarked during Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts that “a little rebellion” now and again was “a good thing.” He had been ambassador to Paris and remained faithful in his support of revolutionary France.

So divided were the American people over this ongoing, destructive war in Europe that ardent Republicans took to wearing liberty caps—stocking-like headgear favored by French republicans—and French-style tricolor cockades on their hats. Federalists, usually sympathetic to the former mother country, responded in kind by adopting a black cockade with a white button to differentiate themselves from the Francophile Republicans. Attire as much as ideology, it seemed, divided Americans into two camps.

And, in a system that may seem farcical to modern readers, Jefferson—who was narrowly defeated—would therefore become Adams’ vice president. Imagine Hilary Clinton (“Lock her up!”) serving beside President Trump. The expectation in the day was that country would—for good gentlemen, at least—precede party loyalties. That assumption was wrong more often than not. Indeed, until the later adoption of the 12th Amendment, the Constitution stipulated that the second highest vote-getter would serve as vice president.

The political culture, too, was absurdly different from our own day. Personal honor was a deadly serious matter, and dueling (sometimes, though rarely, to the death) constituted an elaborate political ritual to protect reputations. Fistfights broke out on the floor of Congress. It all made sense in an odd way. In the tumultuous 1790s, neither side saw the opposition as possessing a credible dissent. Rather, the fight appeared existential—with the other side representing a threat to liberty or order itself! Federalists used the once pejorative (but gradually more acceptable) term “democrat” to describe their unseemly, anarchic Republican foes. To Jefferson’s Republicans, Adams and his ilk were not “federal” in any sense of the word; rather, they were monarchists, aristocrats even, and the enemies of liberty!

Such was the volatile setting when outright war with France nearly broke out.

The First War on Terror: Immigration, Sedition and the ‘ Quasi-War’

A British satirical depiction of French-American relations in 1798 after the so-called XYZ Affair. Five Frenchmen plunder a female America, while six figures representing European countries look on. John Bull (Britain) sits laughing on “Shakespeare’s Cliff.”

“The time is now come when it will be proper to declare that nothing but birth shall entitle a man to citizenship in this country.” —Federalist Congressman Robert Goodloe Harper

“[The Alien Act] is a most detestable thing … worthy of the 8th or 9th century … dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States.” —Vice President Thomas Jefferson (1798)

Imagine a nation at “war” with a revolutionary ideology. Not a full-fledged, declared war, but a seemingly endless conflict against an amorphous entity thought to imperil the very fiber of the republic. Fear abounds—fear of foreigners, of subversives within. Elected leaders begin to restrict immigration, to deport aliens and to police the untrustworthy media. Nothing short of avid patriotism is acceptable in the midst of the ongoing crisis. Americans are at each other’s throats.

The time I’m describing has long since passed, two centuries in the rearview mirror, long before anyone heard the name Donald Trump. Still, the comparison—and the alarmism of our present—is instructive.

In 1798, revolutionary France—to which Americans arguably owed their independence—and the United States were brought to the verge of war. The French seized U.S. ships en route on the high seas to trade with Britain, still a top commercial partner for American merchants. When President Adams sent envoys to discuss the matter, they were belittled and dictated to by three French agents. The agents were later described by the envoys as Mr. X, Y and Z, and each had demanded humiliating apologies and bribes as a precondition to even begin negotiations. Adams recalled his envoys, and the American people seethed with anger. The bribery demand was particularly galling, and one American envoy, according to a later newspaper account, declared that the U.S. would spend “millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute!”

The Federalists felt vindicated. Indeed, the party would win elections up and down the Atlantic Coast in this period. Alarmist factions within the Federalist ranks began to question the very patriotism and loyalty of the “fifth column” of Republicans. Riots broke out in Philadelphia between pro-French and pro-British factions, and Republican newspaper editors were attacked. Conspiracy theories and exaggeration of threats abounded. As tensions rose, President Adams called for a day of prayer and fasting as a show of national unity. One particularly onerous rumor spread during the fast: Republican insurgents, so said the scare-mongers, planned to burn the U.S. capital.

As the war drums beat, Adams asked Congress to sanction a Quasi-War with France, what Adams called “the half war,” and indeed the resolution passed. Merchant ships were armed and the military budget soared, though hysteria spread faster than actual combat at sea. Hard-line Federalists feared civil war and seemed to spy treasonous French agents around every corner. Nativism and fear pervaded the land. It is likely to be so during a war scare.

What followed was a veritable constitutional crisis—perhaps this nation’s first. Fear of foreign French intriguers, and their Irish allies, expanded like wildfire. In response, Congress first passed the Naturalization Act, which extended the wait before applying for citizenship from five to 14 years. Then, the Alien “Friends Act” gave the president the extraordinary power to expel, without due process, any alien he judged “dangerous to peace and safety.” It must be said that no aliens were actually expelled by Adams, but the accumulation of so much discretion and power in the executive branch terrified Republicans.

Even more worrisome were the subsequent attacks on the “disloyal” press—meaning Republican or non-Federalist newspapers. This was a remarkable power to grant the federal government, seeing as newspapers were the central medium of communication and the glue that held together partisan factions of the day. The actual text of the Sedition Act, read today, is chilling. The legislation declared it a crime to:

Write, print, utter or publish … any false, scandalous, and malicious writings against the Government of the United States, or either House of the Congress of the United States, with the intent to defame the said government, or either House of Congress, or the President, or to bring them … into contempt or disrepute, or to excite against them … the hatred of the good people of the United States.

How could it be, the modern reader might ask, that an elected body could so restrict the beloved freedom of the press less than two decades after a revolution was waged in defiance of tyranny? And, indeed, the vote on the matter was highly contested and narrow: 44-41 in the House of Representatives.

Vice President Jefferson, a fierce opponent of the bill, no doubt took notice that the defamation of the vice president was conspicuously absent from the text of the Sedition Act. He saw the bill for what it was: a thinly veiled “suppression of the Whig [Republican] presses.” What, after all, many Republicans asked, had we just fought a war for, if not for freedom of speech and of the press?

This time, unlike in the Alien Act, the legislation was quickly put to use by Federalist courts. Twenty-five people were arrested, 17 indicted and 10 convicted (some jailed). Most were neither spies nor traitors, but rather Republican-sympathizing newspapermen. The government even arrested Benjamin Franklin Bache (grandson of the esteemed Founder), who died of yellow fever before his trial. The Sedition Act expired at the end of Adams’ administration, but its specifics were not declared unconstitutional until a case was brought forward by The New York Times in the 1960s!

This was politics, not national security, and the Republicans knew it. Some of those jailed styled themselves martyrs of liberty. One, Matthew Lyons, successfully ran for Congress from within his prison cell. Partisan loyalties had divided an administration and brought the nation to verge of civil war.

Seeds of Secession: Jefferson, Madison and the Virginia/Kentucky Resolutions

The official White House portrait of Thomas Jefferson, painted by Rembrandt Peale in 1800.

“A little patience, and we shall see the reign of witches pass over, their spells dissolve, and the people, recovering their true sight, restore the government to its true principles.” —Vice President Thomas Jefferson referring to the Sedition Act in a letter to John Taylor (1798)

The beleaguered Republicans would not go down without a fight. Despite the suppression of the press, the actual number of Republican-leaning newspapers exploded. And, though the resurgent Federalists controlled the Congress in Philadelphia, prominent Republicans turned to the state legislatures to oppose the Alien and Sedition Acts. As the tensions rose, so did the rhetoric. Many opponents of the bills took to referring to the federal government as a “foreign jurisdiction.” This is not dissimilar to the language employed today by some libertarian ranchers in the American West and some militiamen.

Jefferson himself believed that the federal government—of which he was vice president!—had become “more arbitrary, and [had] swallowed more of the public liberty than even that of England.” James Madison, an old and true Jefferson ally, left retirement and entered the Virginia Legislature. Now, Jefferson the disgruntled vice president and Madison the lowly state representative set to work making the case for the unconstitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Acts.

They did not, interestingly, turn to the federal courts. These they saw as Federalist-dominated, and besides, the modern conception of judicial review was not yet established. Instead, in a far more devious, though potentially problematic way, Madison and Jefferson drafted state “resolutions” for Kentucky and Virginia, which made the extraordinary claim that state governments could rightfully declare federal legislation they deemed unconstitutional to be “void and of no force.” Essentially, states could nullify federal law because, as the asserted, the Constitution was but a “compact” between the many states.

Kentucky and Virginia urged the other states to pass similar resolutions, though none saw fit to do so. Still, this was a remarkable moment that set a dangerous precedent. Imagine Vice President Pence secretly drafting an Indiana resolution that declared a prominent piece of President Trump’s agenda to be null and void! Furthermore, unfortunately, Jefferson’s and Madison’s attempts to protect civil liberties blazed a perilous path. The concept of nullification and, finally, of Southern secession would spring from the same lines of argument the two esteemed Founders set forth in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. Civil war, of course, was the unforeseen result.

Good Men, Bad Politicians: John Adams and the Peace That Ended a Presidency

“Armies, and debts, and taxes are the known instruments for bringing the many under the domination of the few.” —James Madison (1795)

In addition to legislation meant to ensure “order,” Adams and the Federalists actively prepared the nation for war. Adams, for one, was doubtful that France could or would ever invade, but he preferred that the nation be prepared. Other ultra-Feds, like Hamilton, saw opportunities for the power and expansion of the federal government during the war scare.

More naval funding was authorized in one year than in all previous congresses to date. And, ultimately, a country that had once vehemently opposed standing armies now raised a “New Army,” 12,000 men strong. Pushing for this rapid expansion was Alexander Hamilton, who more than any other Founder desired a European-style fiscal-military state. In fact, Hamilton wanted to lead said army, though he settled for second-in-command to the largely ceremonial leadership of George Washington (again called out of retirement).

War hysteria quickly got out of hand. Republicans feared, not without some merit, that the true purpose of this “New Army” was to suppress the political opposition. Indeed, most of the officers appointed to the new force were of Federalist leaning. But Hamilton had even more grandiose notions than domestic oppression. He saw opportunities aplenty in the case of a war he seems to have truly desired. War with France, he argued, would allow the seizure of Louisiana, Florida and maybe even distant Venezuela from France and Spain!

President Adams, though, had far more common sense, and retained enough of the revolutionary “spirit of ’76,” to deny Hamilton the supreme command and the empire that the man so desired. “Never in my life,” Adams later recalled, “did I hear a man [Hamilton] talk more like a fool.” In a letter to a colleague, Adams went so far as to declare Hamilton “the greatest intriguant in the World—a man devoid of every moral principle—a Bastard.”

George Washington, too, quickly lost interest in the military expansion and soon returned to Mount Vernon, and eventually tensions and the war scare eased. But the main catalyst for peace was President Adams himself. Adams retained some of his fear of standing armies, loathed Hamilton and knew war was the last thing the new nation needed.

Thus, without consulting his Cabinet and in opposition to his own party agenda, Adams sent a peace mission to France. This action cooled the Quasi-War and averted a civil crisis. It was not, however, a prudent political move. The actions of Adams inadvertently divided his once ascendant Federalist Party just before the election of 1800—when he would again face off against his vice president, Jefferson.

A (flawed) patriot more than a politician, Adams dismissed the Hamiltonians in his Cabinet and secured the Treaty of Mortefontaine, bringing to an end the Quasi-War with France. Unfortunately for Adams the paltry politician, word of this diplomatic coup did not reach American shores until he had been defeated in the 1800 balloting.

Liberty or Order: The Eternal Debate

“The Federalists of the 1790s stood in the way of popular democracy as it was emerging in the United States, and thus they became heretics opposed to the developing democratic faith.” —Historian Gordon Wood (2009)

It never ends, the debate. Even now, it is as though Adams and Jefferson were still alive, battling for the possession of our American souls. The relevant issues from the 1790s are as plentiful as they are astounding. So many of the questions of yesteryear are precisely those that Americans grapple with in 2018.

How free should the press be? What constitutes libel? How should government treat leakers (think Snowden or Manning) and whistleblowers? And what of immigration? Are foreigners a threat to the body politic? Do we need a “big, beautiful” wall? Should some migrants (i.e. Swedes) be more welcome than others (Arabs or Muslims)?

The Patriot Act, warrantless surveillance, torture, race, ethnicity, the bounds of protest (see the NFL-kneeling dispute), the “crooked” media, drones, Guantanamo, the scope of federal and executive power. It’s all there, isn’t it? Adams and Jefferson, if suddenly brought back to life in today’s United States, would not be able to fathom an iPhone but would no doubt be ready to weigh in on debates regarding searches and seizures of those devices. On one level we’ve come so far, on another … not so much.

The common denominator in all of this seems to be war—war or the fear provoked by war and the threat of it. It matters not whether the U.S. wages a Quasi-War with France on the high seas or fights a shapeless enemy like “terror” across the Greater Middle East. The questions remain, the passions flare. We divide into camps, armed—sometimes literally—and oriented on our domestic enemies. Today’s “liberals” are not seen as misguided although valued countrymen but as traitorous weaklings ready to sell out America. “Conservatives” aren’t folks standing for time-tested values but instead are fascist authoritarians bent on tyranny.

It all seems so far off the rails. And it is dangerous.

Through modern eyes, we are apt to see this division as a unique and exceptional feature of contemporary politics. But, oh no, it was always thus.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 9: “The Early Republic, 1789-1824” (2011).

Gordon Wood, “The Significance of the Early Republic,” Journal of the Early Republic 8, No. 1 (Spring 1988).

Gordon Wood, “Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815” (2009).

* * *

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Truthdig is running a reader-funded project to document the Poor People’s Campaign . Please help us by making a donation .

Filmmaker Sara Driver on Jean-Michel Basquiat (Audio and Transcript)

In this week’s episode of “Scheer Intelligence,” host and Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer talks with independent film director Sara Driver, whose film “Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat” explores the artist’s life in the late 1970s and early ’80s, before he reached the height of fame in the art world.

Driver tells Scheer that while New York City during Basquiat’s teenage years was dangerous, it was also a great place to be an artist and to experiment.

“Diego Cortez at one point said to me—I don’t have it in the film, but he said—‘It was like Paris at the turn of the century, or Berlin in the 20s,’ ” she says. “This meeting of so many people, so many young people from all over the country who were experimenting with so many different forms.”

She also speaks to the relevance of Basquiat’s work despite the dramatically changed landscape in New York, and says she hopes the film encourages young people to try new things and not worry about failing.

Listen to the interview in the player above and read the transcript below. Find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

–posted by Emily Wells

Full transcript:

Robert Scheer: Well, hello. This is another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case, Sara Driver, the director of a movie that’s getting a lot of interesting and favorable criticism and reviews. It’s called Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat. You know, I remember that period; actually, I remember being in New York at that time, East Village life. And as you describe it in the film, the city was decaying; we’re talking about–well, his life was from 1960 to ‘87, I guess. And why did you pick the teenage years? And it sort of makes a statement about New York and the emerging art scene.

Sara Driver: My friend Alexis Adler, who lived with Jean-Michel from 1979 to 1980, and while she was studying at Rockefeller University, she was studying tropical diseases, she looked through a microscope for 30 years. And after Jean left her, you know, left living with her, she put away all this work that he’d left behind, that he had given her. And when Sandy, Hurricane Sandy, hit the Lower East Side and flooded the Lower East Side, she suddenly remembered she had all this work that she had put away. And it was in a bank vault underground, so she was quite worried about it. And then she went and looked in the bank box, and she had 60 works of his, including notebooks, writings, drawings. And then she remembered she had put away a box of clothes that he had painted, and she also rediscovered about 150 photographs she had taken of him while he lived with her. I went over to her house, just right after Sandy hit, and right after she rediscovered all these things. And I saw everything that she had, and I just thought, when I saw it–wow, this is such an insight into him as a developing artist, and also a window into our city at that time. There’s very little work of his, there’s smatterings of it among friends, but there’s very little work of his at that time, because he was so transient. But she really kept a wonderful archive that really gives clues into his later paintings and his thought process.

RS: Probably most people listening to this know a great deal about Jean-Michel Basquiat, because, if for no other reason than that last May, last year, a painting of his set the record of all time, $110 million and change. And I gather that’s the most expensive painting for an American artist ever?

SD: I think for any artist ever.

RS: Yeah, any artist. And it’s a skull, and it was bought by a Japanese entrepreneur, who made his money with sort of internet applications and so forth. And he’s going to open a museum outside Tokyo and have it there. And it just raised the question, because he’s described as a rebellious artist, somebody who came out of street art, associated with various musical movements as well as artistic at the time. And your documentary I found fascinating because it really raises the question of whether he was a rebel, or whether this was a kid, you know, from a family that was breaking up, a Haitian family where he wanted in, he wanted to be in on the hottest scene. And it’s really a question whether he was a rebel, or he was somebody who actually was desperate to get into this commodity culture that he often decried.

SD: Well, I think he was a very driven artist; that’s clear, he was incredibly prolific in the short amount of time that he lived. And what I learned making the film, I mean, I knew he was a great wordsmith, but I really realized that by the age of about 18, he was an advanced poet already. His use of words are phenomenal, and I think that also makes his paintings so special.

RS: And he was fluent in three languages, right? And so he had French, Spanish, English. And I’m just trying to capture, I mean, for people who haven’t yet seen the movie, and they should go and watch it all, it seems to me there’s a tension in the film. There’s no question he’s a prolific artist, there’s no question he’s brimming with all sorts of ideas. But it seems to me the film poses or begs the question, what was his rebellion about? Was it trying to get in, be successful, be accepted? Or was it to make all sorts of contrarian political statements and challenge the status quo?

SD: Well, I think I was trying to show in the film the environment that nurtured him. Because a lot of the artists that were working then, that were around and in the Lower East Side, were politically active, and activists. You know, taking over abandoned buildings and doing shows in them, and really, you know, declaring themselves their own art galleries and things like that, being that they weren’t accepted by the established art world. I mean, Jean Michel was very calculating in that he did Samos only in the area where there were art galleries. And I use in the poster a picture that Al Diaz, who was his partner in SAMO, where he’s wearing a beret, and I said to Al, I said, well, does he think, is he trying to be Che Guevara with that beret on his head? And Al started laughing and he said, no, that’s what Jean Michel thought that an artist looked like.

RS: For people who don’t know, Samos was the graffiti message, basically, right, “SAMO,” that suddenly appeared in these neighborhoods and had sort of provocative content, raised questions. And then at some point they just stopped it, the two of them, they had a falling out, moved on to other things.

SD: Well, Jean Michel took, you know, when there was the, after the article in the Village Voice, which exposed SAMO, he took that on as his own. You know, was not good to Al. But many years later, Al told me that he was in his tenement apartment and the doorbell rang, and he looked down, and there was Jean Michel with a triptych painting. And he was looking up at Al, and he had this painting for Al, and it said “From SAMO to SAMO.” So Jean Michel was very aware that he was not correct with him.

RS: You know, this is a film that you obviously did with a great deal of understanding and love. What would you say the lesson, or the lessons, are from watching this? What does it tell us about art, artists, and this particular artist?

SD: Well, I think it was such, like a particular moment in time in New York City where there was this gathering of so many varied kinds of artists. We’re really lucky–Diego Cortez at one point said to me, I don’t have it in the film, but he said: It was like Paris at the turn of the century, or Berlin in the twenties. This meeting of so many people, so many young people from all over the country who were experimenting with so many different forms. And so it was very exciting, because art–all kinds of art needs other art to nurture it, and I think that we all germinated each other, in a way. And Jean Michel himself was a musician, he was a poet, he was a painter, he was a sculptor. I’m sure, you know, he was also an actor; he produced this incredible record by the artist Rammellzee. And all of us were sort of trying things, and trying different forms, and failing at them, and succeeding. And I think now, young people, they feel a risk at failing. And you know, you have to fail in order to learn. And it’s very important, and not everything can be perfect. You know, we had a very like “Just pick up a guitar and play it,” you know, “Pick up a paintbrush and paint”; you know, just try things. And I think that spirit was really contagious for all of us. I remember going to see a show put together by Carlo McCormick, who’s also in the film. And he did a show of New York City, downtown New York 1974 to 1984. And that was the first time, because I was inside this world, it was the first time I saw, looking from outside, of how many of the arts did germinate each other. You know, and how rich it was in terms of performance art and music and all those things.

RS: Well, it was also a time when the Big Apple was a bit rotten, in appearance, right? There was enormous contradictions, you know, of the Bronx burning, of decay, urban decay, violence and so forth. And it’s not the polished, gentrified SoHo of now, or Lower East Side of now, of this time. And his art addressed that uglier contradiction. The graffiti, and then his art, had messages; they were enigmatic, but they were provocative. The real question I keep pushing here, and maybe it’s not the right question, but it seems to me that it’s in your movie, is, he was against the whole commodity fetish and the whole commercialization of everything. But he ends up apparently embracing it, and wanting to be part of it. And so the money is not an accident; he was actually open to marketing. I mean, there are plenty of street artists that die poor, but he didn’t; he seemed to be on a calculated path to a certain kind of material success, was he not?

SD: Everybody was very surprised by that, that this 18-year-old kid was so determined. And also like when Patricia Fields in the film talks about, you know, that his sculptures, he wanted $10,000 in 1979, you know [Laughs] None of us were really thinking about money, or that–you know, [inaudible] said to me, you know, if you could publish a poem in a magazine, that was the height of success. Because we didn’t need much money to live then, so we weren’t thinking in terms of money and making art for money; we were kind of making art for each other. And, but Jean was very unique in that. But I also find him as an artist to be almost like a profit, because his paintings are so relevant now. His subject matters are so relevant now, and so vibrant. You know, I think a lot of great artists have that kind of gift. You know, I always think of, like, J.G. Ballard as being almost a profit, or Burroughs, or people like that. And knowing his self-worth was incredible for a teenage, a guy in his late teens.

RS: OK. I’m going to drop this point after trying one last time. [Laughter] That’s OK, I may be totally off base here. But I got a sense that this was not just art for art’s sake, or art for its message; that this guy, whatever his other motives, also wanted to prove that he could make it, and he could make it like a Warhol made it, or others. That he was going to crack this market. And he was an unusual figure, which was mostly white people, right, of certain backgrounds. And he seemed quite determined to figure it out and then succeed at it. And at the end of your movie, one is not surprised that he ends up being an enormous financial success, and he has appeal to another group of people–you’re stressing the artists, and living on very little–but also, this is where the bankers started emerging in New York.

SD: Exactly.

RS: These people are throwing a lot of money around, and these wonderful avant-garde galleries are starting to make a lot of money selling to Wall Street types, right? And the ultimate sale, so far, anyway, of his work, to a, you know, a businessman from Tokyo, is a perfect example. This guy in interviews can hardly explain what he even likes about the painting, but it’s just prestigious to have it.

SD: Well, I think that’s also why I stopped my movie in 1980. You know, in ends in 1981. Because then the bankers started stepping in, and everything started changing. And you know, Jean didn’t, when he died at 27 years old, he didn’t have a whole lot. I mean, he didn’t own a house, he didn’t own a car; he had really nice clothes, he went on nice vacations, he drank good wine. But nothing like what his work is selling for today. You know, he did have a sense of how valuable he was, and he was a very hard worker. And I think you’re right, I think he wanted a certain acceptance, and to prove that he could do it. And he was extraordinary.

RS: You know, you were a witness to a critical time. It really sort of started in the postwar period. But where art becomes, a market is made in art, it becomes an incredible commodity, hustle, thing to game. And people who really don’t care very much about art suddenly get interested in it either for fun or profit; that you can buy this stuff, bet on who’s going to succeed; maybe game the system by having other friends, who write criticism for big newspapers or something, write about it. And you’re going to come out a winner, and you know, as I’ve gone around as a journalist and been in different people’s homes, they’re very proud of their acquisitions, particularly from that period. And you were a witness to that, right? And didn’t–I remember Thomas Wolfe’s book, The Painted Word; I mean, there was something that happened with the commercialization of all this, that the artists thought they were doing something very provocative and interesting, but it was really very expensive wallpaper for the customers, right?