Chris Hedges's Blog, page 516

July 29, 2018

Palestinian Protest Icon Tamimi Released From Israeli Prison

NABI SALEH, West Bank — Palestinian protest icon Ahed Tamimi returned home to a hero’s welcome in her West Bank village on Sunday after Israel released the 17-year-old from prison at the end of her eight-month sentence for slapping and kicking Israeli soldiers.

Ahed and her mother, Nariman Tamimi, were greeted with banners, cheers and Palestinian flags as they entered their home village of Nabi Saleh.

Ahed was arrested in December after she slapped two Israeli soldiers outside her family home. Her mother filmed the incident and posted it on Facebook, where it went viral and, for many, instantly turned Ahed into a symbol of resistance to Israel’s half-century-old military rule over the Palestinians.

With her unruly mop of curly light-colored hair, the Palestinian teen quickly became a local hero and an internationally recognizable figure.

Her supporters see a brave girl who struck two armed soldiers in frustration after having just learned that Israeli troops seriously wounded a 15-year-old cousin, shooting him in the head from close range with a rubber bullet during nearby stone-throwing clashes.

In Israel, however, she is seen by many either as a provocateur, an irritation or a threat to the military’s deterrence policy — even as a “terrorist.” Israel has treated her actions as a criminal offense, indicting her on charges of assault and incitement. Her eight-month sentence was the result of a plea deal.

In Nabi Saleh, supporters welcomed Tamimi home Sunday with Palestinian flags planted on the roof of her home. Hundreds of chairs were set up for well-wishers in the courtyard.

“The resistance continues until the occupation is removed,” Ahed said upon her return. “All the female prisoners are steadfast. I salute everyone who supported me and my case.”

From her home, Ahed headed to a visit to the grave of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat. She laid a wreath and recited a prayer from the Quran, the Muslim holy book, and was then taken with her family to a meeting with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas at his headquarters in Ramallah.

“I will continue this path and I hope everyone will,” she said. “The prisoners are fine and we hope the struggle for their release continues.”

Her father, Bassem Tamimi, said he expects her to take a lead in the struggle against Israeli occupation but she is also weighing college options. He said she completed her high school exams in prison with the help of other prisoners who taught the required material. He said she initially hoped to attend a West Bank university but has also received scholarship offers from abroad.

Since 2009, residents of Nabi Salah have staged regular anti-occupation protests that often ended with stone-throwing clashes. Ahed has participated in such marches from a young age, and has had several highly publicized run-ins with soldiers. One photo shows the then 12-year-old raising a clenched fist toward a soldier towering over her.

In a sign of her popularity, a pair of Italian artists painted a large mural of her on Israel’s West Bank separation barrier ahead of her release. Israeli police say they were caught in the act along with another Palestinian and arrested for vandalism.

Abbas, after meeting Ahed on Sunday, called her “a symbol for the Palestinian struggle for freedom and independence.”

“The popular and peaceful style of struggle that Ahed Tamimi and her village and nearby villages have been practicing, proves to the world that our people will remain steadfast in this land, defending it no matter how much needs to be sacrificed,” he said.

Tamimi’s scuffle with the two soldiers took place Dec. 15 in Nabi Saleh, which is home to about 600 members of her extended clan.

At the time, protests had erupted in several parts of the West Bank over President Donald Trump’s recognition 10 days earlier of the contested city of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. She was arrested at her home four days later, in the middle of the night.

Ahed was 16 when she was arrested and turned 17 while in custody. Her case has trained a spotlight on the detention of Palestinian minors by Israel, a practice that has been criticized by international rights groups. Some 300 minors are currently being held, according to Palestinian figures.

Israel captured the West Bank, Gaza and east Jerusalem in the 1967 Mideast war. Palestinians are increasingly disillusioned about efforts to establish a state in those territories, after more than two decades of failed negotiations with Israel.

Israeli Cabinet minister Uri Ariel said the Tamimi case highlighted what could happen if Israel lets its guard down.

“I think Israel acts too mercifully with these types of terrorists. Israel should treat harshly those who hit its soldiers,” he told The Associated Press. “We can’t have a situation where there is no deterrence. Lack of deterrence leads to the reality we see now … we must change that.”

Our Failing World

There was a period in my later life when I used to say that, from the age of 20 to my late sixties, I was always 40 years old; I was, that is, an old young man and a young old one. Tell that to my legs now. Of course, there’s nothing faintly strange in such a development. It’s the most ordinary experience in life: to face your own failing self, those muscles that no longer work the way they used to, those brain cells jumping ship with abandon and taking with them so many memories, so much knowledge you’d rather keep aboard. If you’re of a certain age — I just turned 74 — you know exactly what I mean.

And that, as they say, is life. In a sense, each of us might, sooner or later, be thought of as a kind of failed experiment that ends in the ultimate failure: death.

And in some ways, the same thing might be said of states and empires. Sooner or later, there comes a moment in the history of the experiment when those muscles start to falter, those brain cells begin jumping ship, and in some fashion, spectacular or not, it all comes tumbling down. And that, as they say (or should say), is history. Human history, at least.

In a sense, it may hardly be more out of the ordinary to face a failing experiment in what, earlier in this century, top officials in Washington called “nation building” than in our individual lives. In this case, the nation I’m thinking about, the one that seems in the process of being unbuilt, is my own. You know, the one that its leaders—until Donald Trump hit the Oval Office—were in the habit of eternally praising as the most exceptional, the most indispensable country on the planet, the global policeman, the last or sole superpower. Essentially, it. Who could forget that extravagant drumbeat of seemingly obligatory self-praise for what, admittedly, is still a country with wealth and financial clout beyond compare and more firepower than the next significant set of competitors combined?

Still, tell me you can’t feel it? Tell me you couldn’t sense it when those election results started coming in that November night in 2016? Tell me you can’t sense it in the venomous version of gridlock that now grips Washington? Tell me it’s not there in the feeling in this country that we are somehow besieged (no matter our specific politics), demobilized, and no longer have any real say in a political system of, by, and for the billionaires, in a Washington in which the fourth branch of government, the national security state, gets all the dough, all the tender loving care (except, at this moment, from our president), all the attention for keeping us “safe” from not much (and certainly not itself)? In the meantime, most Americans get ever less and have ever less say about what they’re not getting. No wonder in the last election the country’s despairing heartland gave a hearty orange finger to the Washington elite.

States of Failure

“Populist” is the term of the moment for the growing crew of Donald Trumps around the planet. It may mean “popular,” but it doesn’t mean “population”; it doesn’t mean “We, the People.” No matter what that band of Trumps might say, it’s increasingly not “we” but “them,” or in the case of Donald J. Trump in particular, “him.”

No, the United States is not yet a failed or failing state, not by a long shot, not in the sense of countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen that have been driven to near-collapse by America’s twenty-first-century wars and accompanying events. And yet, doesn’t it seem ever easier to think of this country as, in some sense at least, a failing (and flailing) experiment?

And don’t just blame it on Donald Trump. That’s the easy path to an explanation. Something had to go terribly wrong to produce such a president and his tweet-stormed version of America. That should seem self-evident enough, even to — though they would mean it in a different way—The Donald’s much-discussed base. After all, if they hadn’t felt that, for them, the American experiment was failing, why would they have voted for an obvious all-American con man? Why would they have sent into the White House someone whose Apprentice-like urge is to fire us all?

It’s hard to look back on the last decades and not think that democracy has been sinking under the imperial waves. I first noticed the term “the imperial presidency” in the long-gone age of Richard Nixon, when his White House began to fill with uniformed flunkies and started to look like something out of an American fantasy of royalty. The actual power of that presidency, no matter who was in office, has been growing ever since. Whatever the Constitution might say, war, for instance, is now a presidential, not a congressional, prerogative (as is, to take a recent example, the imposition of tariffs on the products of allies on “national security” grounds).

As Chalmers Johnson used to point out, in the Cold War years the president gained his own private army. Johnson meant the CIA, but in this century you would have to add America’s ever vaster, still expanding Special Operations forces (SOF), now regularly sent on missions of every sort around the globe. He’s also gained his own private air force: the CIA’s Hellfire-missile armed drones that he can dispatch across much of the planet to kill those he’s personally deemed his country’s enemies. In that way, in this century—despite a ban on presidential assassinations, now long ignored — the president has become an actual judge, jury, and executioner. The term I’ve used in the past has been assassin-in-chief.

All of this preceded President Trump. In fact, if presidential wars hadn’t become the order of the day, I doubt his presidency would have been conceivable. Without the rise of the national security state to such a position of prominence; without much of government operations descending into a penumbra of secrecy on the grounds that “We, the People” needed to be “safe,” not knowledgeable; without the pouring of taxpayer dollars into America’s intelligence agencies and the U.S. military; without the creation of a war-time Washington engaged in conflicts without end; without the destabilization of significant parts of the planet; without the war on terror—it should really be called the war for terror—spreading terrorism; without the displacement of vast populations (including something close to half of Syria’s by now) and the rise of the populist right on both sides of the Atlantic on the basis of the resulting anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim sentiments, it’s hard to imagine him. In other words, before he ever descended that Trump Tower escalator into the presidential race in 2015, empire had, politically speaking, trumped democracy and a flawed but noble experiment that began in 1776 was failing.

Had that imperial power not been exercised in such a wholesale way in this century, Donald Trump would have been unimaginable. Had President George W. Bush and his cronies not decided to invade Iraq, The Donald probably would have been inconceivable as anything but the proprietor of a series of failed casinos in Atlantic City, the owner of what he loves to call “property” (adorned with those giant golden letters), and a TV reality host. And the American people would not today be his apprentices.

When that “very stable genius” (as he reminded us again recently) inherited such powers long in the making, he also inherited the power to use them in ways that would have been unavailable to the president of a country that had genuine “checks and balances,” one in which the people knew what was going on and in some sense directed it. Consider it a sign of the times that he’s the second president to lose the popular vote in this 18-year-old century—the first, of course, being George W. “Hanging Chad” Bush. So perhaps it’s only proper that President Trump has now nominated to the Supreme Court a judge who was once a Republican operative for the very legal team focused on stopping the recount of those contested Florida ballots in 2000—a recount the Supreme Court did indeed halt, throwing the election to Bush. Note that Brett Kavanaugh is also the perfect justice for America’s new imperial age of decline, one who genuinely believes that the law should read: the president, while in office, is above it. Think of him as Caligula’s future enabler.

In other words, in the twenty-first century, Donald Trump is proof indeed that the American experiment in democracy may be coming to an unseemly end in a president with all the urges of an autocrat (and so many other urges as well). Or think of it this way: the contest—from early on an essential part of American life — between democracy and empire seems to be ending with empire the victor. However—and here may be Donald Trump’s particular significance—empire, too, looks to be heading toward some kind of ultimate failure. He himself is visibly a force for imperial demolition. He seems intent—as in the recent abusive NATO meeting and the chaotic get-together with Russian President Vladimir Putin—on dismantling the very world that imperial America built for itself in the wake of World War II. You know, the one in which it was to be the ultimate and eternal victor in a rivalry between imperial powers that had begun in perhaps the fifteenth century, reached its peak when only two “super” rivals were left to face each other in the Cold War, and ended with a single power seemingly triumphant and alone on planet Earth.

How quickly those historically unique dreams of global dominion fell apart in the “infinite wars” of this century. Think of Donald Trump as the overly ripe fruit of that failure, that endless imperial moment that never quite was. Think of him as the daemon in the (malfunctioning) global machinery of a world that is itself — as in Brexiting “Europe” — evidently beginning to come apart at the seams amid war, a flood of global refugees, and one factor never experienced before (on which more below). Think of America as being caught up in some only half-recognized United Stexit moment, though what exactly we are withdrawing from may be less than clear.

How quickly those historically unique dreams of global dominion fell apart in the “infinite wars” of this century. Think of Donald Trump as the overly ripe fruit of that failure, that endless imperial moment that never quite was. Think of him as the daemon in the (malfunctioning) global machinery of a world that is itself — as in Brexiting “Europe” — evidently beginning to come apart at the seams amid war, a flood of global refugees, and one factor never experienced before (on which more below). Think of America as being caught up in some only half-recognized United Stexit moment, though what exactly we are withdrawing from may be less than clear.

Still, bad as any moment might be, you can always hope for, dream about, and work for so much better, as so many have over the centuries. After all, everything I’ve described remains the norm of history. What empire hasn’t had its Caligulas, its Trumps? What empire hasn’t, in the end, gone down? What democratic experiment hasn’t sooner or later faltered? Even the best of experiments come up short as autocrats take power and hand their rule on to their sons, only to be overthrown by some revolt, some new attempt to make better sense of this world, which itself falters sooner or later. And so it goes.

Again, that, as they say, is history, a series of failed experiments, but ones that always end, in their own fashion, with hope still alive for a better, fairer, juster world. Yes, a particular failure might be terrible for you, your community, even several generations of yous, but it, too, will pass and you can expect our better angels to reappear someday, even if not in your lifetime—or at least until recently you could do so.

The Ultimate Experiment

There is, however, another experiment, a planet-wide one that seems to be failing as well. You could think of it as humanity’s experiment with industrial civilization, which is disastrously altering the environment of this previously welcoming world of ours. I’m referring, of course, to what the greenhouse gases from the fossil fuels we’ve been burning in such profusion since the eighteenth century are doing to our planet.

Whether you call it climate change or global warming, the one thing it isn’t—despite the fact that we’ve done it—is history. Not human history anyway. After all, its effects will exist on a time scale that dwarfs our own. If allowed to play out to its fullest, it could destroy civilization. And ironically enough, unlike so many of our experiments, this was one we didn’t even know we were conducting for something like a century and a half. So consider it an irony that it’s the one likely to endanger every other imaginable experiment. If not somehow halted in a reasonably decisive fashion, it could not only inundate coastal cities, turn verdant lands into parched landscapes, and create weather extremes presently hard to imagine, but produce heat that will be devastating.

And yet don’t give us any kind of a free pass on this one. Despite those endless years of not knowing what we were doing, ignorance can’t be pled. Increasing numbers of us (including the giant oil companies who did everything humanly possible to keep the news from the rest of us) have known about this since at least the 1960s. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson’s science advisory committee sent him a report that highlighted a human-caused warming of the planet from the carbon dioxide burned off by fossil fuels. It included remarkably accurate projections of the increased heat to come in the twenty-first century and of other effects of climate change, including sea level rise and the warming of sea waters. So don’t say that no one was warned. As time went on, we’ve been warned again and again.

And for this, too, Donald Trump can’t be blamed, but his presence in the White House is now a powerful symbol of a human failure to grasp the dangers involved. Talk about a symbolic act of self-destruction: the American people put a fierce climate denier in the White House. He, in turn, has brought his passionate 1950s-style fantasies of an even more oil-fueled global future with him. He has, among other things, appointed a remarkable set of Republican climate-change doubters and deniers to crucial positions throughout his administration. He’s moved to withdraw this country from the Paris climate accord, while powering up fossil-fuel and greenhouse-gas-producing projects of every sort and weakening the drive to develop alternative energy sources; he has, that is, done everything in his power to stoke global warming.

Along with the actions of the CEOs of the giant oil companies, this will surely prove to be the greatest criminal enterprise in history, since it takes the all-time largest greenhouse gas emitter out of the running (except at the state and local level) when it comes to impeding global warming. In other words, whatever else he may be, President Donald Trump seems singularly intent on being a one-man wrecking crew when it comes to human history.

Since Lucy walked upright by that African lake three million years ago, this has been a remarkably welcoming planet for the human experiment. If, in the coming century, climate change hits full force, it won’t just be a matter of refugees in the hundreds of millions or individual deaths in countless numbers, or some failing democracy that became an empire. It could mean the failure of the whole human experiment in ways that are still hard to grasp. It could mean no more chance for failure, The End.

That’s something worth working against. That’s a failure no one in any possible future can afford.

In the meantime, here I am, another year closer to my own moment of “failure,” living in a potentially failing country on a potentially failing planet. Happy birthday to me.

July 28, 2018

Bill Would Ban Federal Officers From ‘Consensual’ Sex With Those in Custody

A bill has been introduced in Congress banning federal law enforcement officers from claiming that sexual encounters with persons in their custody are consensual. While legislation already exists in some states banning such acts, an astonishing 31 states still allow it. The “The Closing Law Enforcement Consent Loophole Act” aims to rectify the loophole that lets officers claim consent as a legal defense in instances of alleged assault or rape.

Introduced by Reps. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., and Barbara Comstock, R-Va., the bipartisan bill would make engaging in sexual acts with those in custody punishable by up to 15 years in prison. The bill would also grant additional funding to states that pass the legislation and that submit reports to the U.S. attorney general and Congress on the number of such complaints received. This last provision is meant to determine the true scale of these abuses.

Rep. Speier commented in a press release:

Research shows that sexual misconduct is the second most frequently reported form of police abuse, yet the true scope of the problem is unknown because states are not required to report these kinds of allegations or arrests to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

She added she hopes that “This bill will close a loophole that more than a dozen predators have used in the past decade to escape conviction.”

The issue was brought to light in 2017 after a high school student was allegedly raped by two New York detectives while in their custody—in handcuffs. Under New York State law, the officers were able to claim the act was consensual and could plead it as a misdemeanor charge for misconduct. In March, New York changed the law. The officers are now awaiting trial.

In the same press release, Congresswoman Speier said:

This is unconscionable. Law enforcement members wield incredible power in their ability to detain individuals. Our bill ensures that police will act accordingly in their official duties, as befitting their role as officers of the law, and that any such abuse of this power will not be tolerated.

While the bill would prohibit further abuses from law enforcement, it calls into question why, in the #MeToo era, the bill is only now being introduced. Six seasons of the popular Netflix series “Orange Is the New Black”—which highlights injustices by police and the prison system—will have aired before the bill’s passage. Hopefully, by the seventh and final season, officers will no longer be able to plead that sex with those in custody is consensual.

American History for Truthdiggers: Andrew Jackson’s White-Male World and the Start of Modern Politics

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 14th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 14 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13.

* * *

“… When the right and capacity to do all is given to any authority, whether it be called people or king, democracy or aristocracy, monarchy or a republic, I say: the germ of tyranny is there. …” —Alexis de Tocqueville, “Tyranny of the Majority”

There are precious few presidents, indeed, who can claim to have an entire era bearing their name. Andrew Jackson is one. Historians have long labeled his presidency and the years that followed it as “Jacksonian” America. This is instructive. Whatever else he was, this man, General—later President—Jackson, was an absolute tour de force. He swept to power on a veritable wave of populism and forever altered the American political scene. One might argue, plausibly, that we live today in the system he wrought.

Born to modest means in the Carolinas, Jackson led a hard life and somehow found prosperity. Orphaned as a child, he volunteered as a courier for the Continental Army when just 13 years old. Captured by the British, he refused to shine the boots of a captor and was struck on the head with the officer’s sword. Jackson would bear the scar, and his hatred for all things British, throughout his life. He became a lawyer, moved west to Tennessee and eventually amassed a fortune (and many slaves). As a general in the War of 1812 he stood out as the only real hero of that costly draw of a conflict. Called “Old Hickory” by his troops, Jackson is perhaps the first president to bear a catchy nickname. By the 1820s, Jackson was a household name and a staunch Democratic politician. He sought power for himself and, ostensibly, the “common man.”

Politics and presidential campaigning were forever changed by Jackson. This was a man who knew how to win—no matter the cost. Before Jackson, although many early presidential elections were highly contested, the tradition among candidates was to eschew personal campaigning. These were refined gentlemen and they thought themselves above rank electioneering. They sought to evoke a disinterested and modest persona and left it to newspapers and partisans to make arguments on their behalf. Not so, Andrew Jackson. Here was a man who exuded confidence and personal popularity. His was the era of the first political party conventions and of outright campaigning. Democrats were more proud of their candidate than their policies, and ran on Jackson the man.

All of this is ironic because it is unclear that the Founding Fathers actually intended for democratization in the way Jackson and his backers envisioned it. In fact, the U.S. was designed as a republic, not a direct democracy, and institutions such as the Senate and Electoral College were designed to curtail popular rule. Probably, given human nature and the tendencies of the systems the Founders created, the Revolutionary generation misunderstood where their republic would lead—toward greater democratization. Still, it is interesting and worth pondering the fact that Jackson, and the Democrats, stood in contrast to the visions of most Founders.

Indeed, America’s contemporary political culture owes more to Jackson than to George Washington or Thomas Jefferson, which, admittedly, is an uncomfortable truth. In the volume that follows, take a moment to consider whether democracy really is the best possible form of government. Think on the winners and losers inherent in the Jacksonian political revolution and ask whether there existed a better way, an alternative path. We live in the political world Jackson created. It is well we should know something about it.

A Corrupt Bargain?: The Opposing Personalities of John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson

Jackson faced off against the son of President John Adams, John Quincy Adams, in two consecutive elections, in 1824 and 1828. These were among the dirtiest and most contested campaigns in U.S. history. An older generation of historians, as well as the Jacksonians of the day, depicted Adams as an aloof aristocrat, out of touch with the average American. And, indeed, in a sense he was. Adams lacked the “common touch” or charisma of Jackson. That said, Adams was arguably the most well-prepared and qualified presidential candidate in history. He had been a Harvard professor, senator from Massachusetts, ambassador to Prussia, Russia, Britain and the Netherlands, negotiated the treaty to end the War of 1812 and served as President James Monroe’s secretary of state. He spoke several languages.

Still, in the multi-sided race of 1824, the most qualified candidate lost; well, at least he lost the popular vote. Due to the peculiarities of the Electoral College, the election went to the Congress for adjudication. Horrified by the prospect of an uncouth Jackson serving as president, Speaker of the House Henry Clay threw his support behind Adams and won him the presidency. Soon after, in a move with terrible political optics, Adams appointed Clay as secretary of state, a position then considered the fastest road to the presidency. Jackson and his followers—now calling themselves Democratic Republicans, as opposed to Adams’ National Republicans—were aghast and labeled this move a “corrupt bargain.” Clay probably was one of the most qualified candidates to lead the State Department, but the charge stuck and would haunt Adams and Clay for years to come. Consider it an early example of political branding.

As president, Adams sought internal improvements (road, canal and communications infrastructure) led by an activist federal government in order to improve Americans’ quality of life. Clay labeled this the “American System,” and it would be funded and fueled by revenue from a national tariff and federal land sales. This became the core of the National Republican ideology. It was a grand ambition and, unfortunately, would never fully come to fruition. For this reason, Adams’ one-term presidency was long considered a failure. Still, a fresh look may rehabilitate Adams the man, if not Adams the politician.

John Quincy Adams’ National Republican ideology was forward thinking and presaged many federal improvements later implemented. He was a generation or two ahead of his time. He also had rather humanitarian impulses, at least for the age. He protected the Creek Indians from expulsion and a corrupt treaty, and would not countenance Native American removal under his watch. Adams also developed strong anti-slavery sentiments during his long career of public service and would die as something of a full-fledged abolitionist.

Only America wasn’t ready for Adams in 1828. They didn’t want a man like Adams or care much for his progressive, activist policies. Jackson was a war hero, a man of action, a man of violence, a man … like them. He and his many followers wanted the opposite of Adams and his National Republicans. They wanted cheap western land, rapid settlement, state and local sovereignty, and less—not more—federal intervention in their lives. The Southerners, who tended to be staunchly Jacksonian, also feared federal power. They wanted low or no tariffs so they could sell cotton in lucrative overseas markets. Furthermore, if the feds could enforce a tariff, could they not someday ban slavery? In this sense, white supremacy—in the form of slavery and Indian expulsion—stood at the heart of the Democratic agenda.

Adams would lose the 1828 election by a landslide. He wasn’t made for the new politics of the era. He was uncomfortable personally campaigning, especially since the election of 1828 essentially began on his inauguration day and lasted four years! Adams tried to make the election about issues, about his enlightened “American System.” His followers argued that the very aspects of Jackson’s personality that so endeared him to voters actually disqualified him as a viable president. Jackson, they said (not inaccurately), had a violent temper, that he was “ruled by his passions” and had “lived in sin” with a married woman, now his wife, Rachel (she had an estranged husband when she and Jackson were first betrothed).

Still, the charges never really stuck. Jackson was a natural “winner.” His supporters rarely talked policy and focused instead on the admirable qualities of the candidate himself. Jackson personally campaigned against Washington insiders and elites. This resonated with many voters (as such campaigns still do). The Jackson campaign also played dirty, dirtier than nearly any candidate before or after. His supporters (falsely) claimed that Adams was a heretic or an atheist (he was actually a Unitarian) and that while an ambassador he had sold an American girl to the czar of Russia. Adams wanted to talk platforms and policy; Jackson wanted to wage a popularity contest, and that’s what Americans got. The Jackson campaign broke down into what we would now call soundbites, as in the popular Democratic ditty that the election was “between J.Q. Adams, who can write / And Andy Jackson, who can fight.” The fighter won. As usual.

Jackson won some 56 percent of the popular vote, but the results were highly sectional. The Northeast was strong for Adams while the South and the West of that day swung to Jackson. Southerners and Westerners (Jackson himself lived west of the Appalachian Mountains, the first president to do so) trusted the Democratic candidate to better protect their system of slavery and hunger for Indian land. In fact, Adams recorded not a single popular vote in Georgia, the very state most concerned with the presence of native tribes (such as the Cherokee) on its prime cotton-growing land. Indeed, the electoral map of 1828 was remarkably similar both to that of Civil War America in 1860 and our own elections in 2012 and 2016. The South and West favored one candidate, the North and East another.

In the end, the election of 1828 was best summed up in the words of one contemporary newspaperman, Thomas B. Stevenson, who declared that the Adams campaign had “dealt with man as he should be,” while the Jackson campaign had “appealed to him as he is.” There was no love lost between the two competitors. Jackson declined to pay the traditional courtesy call to the outgoing president, and Adams responded by conspicuously not attending the Jackson inauguration. Regardless, the Age of Jackson had begun.

The ‘Democracy’ Paradox: Linking the Market and Political Revolutions

In 1800, most states limited the right of even white males to vote. Some had taxpaying provisions and others had property ownership qualifications for the franchise. By the end of Jackson’s presidency, most such restrictions were a thing of the past. This can only partly be explained by Jackson’s explicit championing of the “common man.” Indeed, the democratization of the U.S. was very much tied up with the concurrent market and communications revolutions of the era.

Capitalism and its cyclical economic “panics”—or recessions—the last of which had occurred in 1819, led more and more Americans to believe that politics directly affected their lives. Furthermore, an increase in media outlets (newspapers) and communications technology garnered more exposure to political tracts. The changing economy, especially early industrialization, also provided new economic opportunities to accumulate wealth. Earlier, vast land ownership and farming were the main paths to prosperity. Now, a man with only moderate amounts of land could earn a fortune through commerce and/or entrepreneurship. These newly rich men chafed under the arcane property qualifications of the day and demanded a fair say in government through the right to vote. In the process, rich and poor alike—at least among white males—would soon gain voting rights.

The increase in voters, especially among commoners, meant that politicians like Jackson now had greater incentive to please, and pander to, the masses. In other words, market and communications advancements constituted a social revolution that forever altered concepts of citizenship. Jackson understood this and seized his opportunity. Men like John Quincy Adams were unprepared for, and uncomfortable with, this seismic change.

There was, however, an irony to all this radical democratization. At the same time as millions of poor whites were gaining the franchise, their newly empowered political class quickly denied those very rights to other men, mostly black men. Before 1820, free blacks could actually vote in many Northern states and a few Southern ones. Unfortunately, some of the first actions of these new poor white voters restricted free-black voting. From 1821 to 1842, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut and Rhode Island passed laws curtailing black civil rights. And, in new constitutional conventions (common during the 1830s), North Carolina and Tennessee took the vote away from free blacks. Indeed, in 1834, one Tennessee delegate at the convention insisted that “We, the People” meant “we the free white people of the United States and the free white people only.”

The conventions in North Carolina and Tennessee eliminated the last vestiges of free-black political rights in the South before the Civil War. Nonetheless, as we see this was an American, not a Southern, phenomenon. White supremacy was popular among the masses—and they enshrined its callous values the moment they received the vote. We may be poor, they seemed to declare, but at least we’re white. In this sense, America developed a identifiable caste– rather than class-based system of social hierarchy. The results would linger for generations.

‘Man of the People’?: The Character of Andrew Jackson

Jackson’s 1829 inaugural celebration as depicted in a 1970 painting by Louis S. Glanzman. The “common people” allowed in by Jackson nearly rioted.

It was easy, at the time, to see Jackson as something of a throwback to Jeffersonian agrarianism. And, by some measures, he was just that. Nonetheless, Jackson’s popularity had more to do with personality than platform. Jefferson possessed the grandest library in the United States, Jackson the grandest ego. Jefferson was professorial, Jackson a man of action. Though the two men agreed on certain issues of state sovereignty, the aging Jefferson loathed Jackson and couldn’t imagine him as president. Dying on July 4, 1826, Jefferson would just miss seeing what he feared most: Jackson in the White House.

But Jackson was popular, and famous. He was a celebrity: a genuine war hero and hearty frontiersman, and he possessed a charismatic demeanor. He was a violent, coarse man—but he epitomized common notions of 19th-century masculinity. He drank, gambled, fought and never, ever apologized. He fought duels (which were illegal in most states) and bore the scars and bullet wounds to prove it. Indeed, Jackson probably counts as the only president in history to have, as a nongovernmental civilian and in cold blood, personally killed a man. (This occurred in an 1806 duel.) Adams thought these characteristics disqualified Jackson for the office, but the Democrats loved these traits. He’s tough, he tells it like it is … he’s just like us! Sound familiar?

To demonstrate his “common touch,” Jackson opened the White House to the public for his inaugural celebration. The crowd tore the furniture out and nearly rioted. The “man of people” was nearly trampled by his people. Still, Jackson was undeterred. Throughout his presidency he continued to equate (in what can be a dangerous construct) his own will with the “will of the people.” But it worked for him and earned him two terms as president. The “people” could not have cared less that Jackson owned a stately mansion (The Hermitage) in Tennessee, replete with Greek columns and French wallpaper. Jackson successfully cultivated a specific anti-elitist and anti-intellectual public persona, and millions loved it. He was also paranoid; he saw conspiracies around every corner and was certain that what we now call the “deep state” was out to destroy him.

An advertisement placed in a Nashville, Tenn., newspaper by Andrew Jackson seeking the return of a runaway slave. It reads, in part: “Stop the Runaway. Fifty Dollar reward. … [T]en dollars extra for every hundred lashes any person will give to him. ”

That never happened, and Jackson’s people remained ever loyal. They barely flinched at the contradictions in his presidency—such as how he doubled spending for internal improvements while in office, despite running against such projects. But if Jackson was president for the “common man,” he was certainly only thus for the white common man. Jackson was a bigot and brutal slave owner. In one advertisement for a runaway slave, he promised “ten dollars extra” for “every hundred lashes” the captor inflicted on the fugitive black in question. Jackson undoubtedly played on the fears and prejudices of poor whites to win their support. These people hated Indians, they hated slaves and they hated “uppity” free blacks. Jackson knew that, implicitly, and pursued policies amenable to this sizable part of the electorate throughout his administration. His “democratization” may have been real, but it was for whites only.To the Victor Go the Spoils: Jackson the Chief Executive

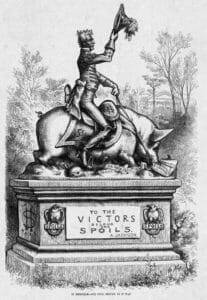

A cartoon satirizing Jackson’s patronage system shows the president riding a money-laden pig above a plaque that reads, “To the Victors Belong the Spoils. —A. Jackson.” At the bottom of the cartoon: “In Memoriam—Our Civil Service as It Was.”

Like nearly ever modern presidential candidate, Jackson ran on a “reform” platform. Only he could, or would, drain the proverbial swamp in D.C. Yet, in another bit of paradoxical irony, Jackson would make famous a tradition—his “spoils system”—that would lead to an outsized increase in corruption. We have Jackson to thank for the platitude “to the victor belong the spoils.” But despite the shock feigned by those who opposed his new policy of appointing friends and allies to nearly every federal position, no one should have been surprised. He had told Americans exactly what he planned to do! During the campaign itself, the editor of the Jacksonian United States Telegraph announced boldly that Jackson would “REWARD HIS FRIENDS AND PUNISH HIS ENEMIES.” He did indeed, and used patronage to do so.

Until 1828, most presidents—including John Quincy Adams—ran the federal bureaucracy as a fairly meritocratic organization. The custom was to leave most mid- and low-level employees in place when administrations switched. The idea was to maintain expertise and professionalism in the various federal departments. Jackson turned that system on its head and produced our modern system of political turnover in Washington. Jackson replaced 919 officials in his first year—more than all presidents combined in the previous 40 years.

The result: Rapid turnover meant less experience in the federal agencies, which equated with diminished competence in and decreased prestige of the federal civil service. Corruption actually increased among these favored political appointees. And, in a final bit of irony, the diminished competence of the federal agencies only bolstered the very Jacksonian argument that the government was inefficient and should be weakened! That strategy, employed with great skill to this day, has proved a winning combination for two centuries. The losers: the customers—the American people.

King Andrew I: Jackson’s Battles for Supremacy

A political cartoon depicting Jackson as “King Andrew the First,” trampling on the Constitution, the Bank of the United States and the judiciary.

Most of the controversies of Jackson’s presidency revolved around issues of presidential authority. Indeed, many of Jackson’s opponents took to calling the president King Andrew I and in the 1830s renamed their political party the Whigs, a title taken from an earlier British party that had opposed royal rule. While not actual royalty, Jackson did display some authoritarian tendencies. He believed strongly in the power of the presidency and reshaped the executive branch forever. For example, while in office he vetoed more congressional bills (12) than all his predecessors combined (10). By way of contrast, in four years John Quincy Adams didn’t veto a single bill. Jackson, on the contrary, never shied away from a challenge and never doubted the importance and pre-eminence of his office.

Jackson reacted boldly to two of the major crises of his administration: the Bank War and the “nullification crisis.” It is ironic that Andrew Jackson has long graced the $20 bill (soon to be replaced in the present day, controversially, by an image of Harriet Tubman) since he hardly understood economics and single-handedly destroyed the national banking system of his time. Jackson thought the Bank of the United States (BUS)—something analogous to our Federal Reserve—was both a challenge to his authority and an unconstitutional, elitist curtailment of states’ banking rights. So, in 1832, in what has been called “the most important veto in U.S. history,” Jackson followed through on his promise and killed the bank.

The president had once again demonstrated his authority and smitten the “elites,” but he simply didn’t understand finance or the ramifications of his decision. The bank—and its unelected head, Nicholas Biddle—may well have had too much influence over the national economy, but at least the BUS regulated the system and avoided major financial panics. In its place, Jackson injected chaos and corruption. He withdrew federal money from the BUS and invested it in numerous partisan (Democratic-controlled) “pet banks,” led by his own political allies. For the most part these banks were less stable, less regulated and more prone to irresponsible lending. The economy would suffer, and this instability contributed to the Panic of 1837, the worst recession to occur between the Founding and the Civil War. Of course, by then Jackson was safely out of office. Jackson never apologized and believed to the end that he had done the right thing.

In removing federal money from a solvent bank and transferring these public funds to “pet banks,” Jackson had violated the spirit, if not the letter, of the law. As a result, he became the first and only president officially censured by the U.S. Senate. It hardly mattered. Jackson may not have known economics, but he did know people. He capitalized on populist resentment of what was perceived as a corrupt and overly powerful federal bank. This played well with his base and the strong strand of anti-elitism (which still exists) in American culture. Sure, he ultimately would crash the economy, but despite his behavior and policies he remained popular and won a second term.

The disestablishment of the BUS empowered New York City’s Wall Street and forever moved the financial capital of the U.S. from Philadelphia to Manhattan. In the end, the people generally lost—even if they didn’t blame their hero, Jackson. Without federal controls and regulation, there was no way to mitigate the cycles of capitalism, and Americans would suffer fairly regular “panics,” or recessions, for generations to come.

The other major supremacy controversy arose over the federal tariff and its unpopularity in South Carolina. Before the Second World War, the vast majority of federal income came from land sales and the tariff. The tariff on foreign imports was rather high in the 1830s (ranging from 25 to 45 percent) and a key part of Henry Clay’s “American System.” The tariff protected the nascent Northern manufacturing industry and helped pay for the promised federal internal improvements. But the tariff was hated in the cotton-growing South. Reliant on the sale of cotton overseas and the import of foreign goods to fuel the Southern economy, South Carolina, in particular, feared (correctly) that Britain would retaliate with tariffs of their own—notably on Southern cotton. After a particularly high import tax rate passed Congress (the “Tariff of Abominations,” as it was labeled), South Carolinians dusted off an old states’ rights concept: nullification.

Vaguely resembling Jefferson and James Madison’s Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of the 1790s, nullification represented South Carolina’s belief that an individual state could declare a federal law unconstitutional and thereby “nullify” it. This was about more than tariffs, however. Slavery, as always, was the elephant in the room. If the feds could force a tariff on Southern states, could it not also someday abolish slavery and upend the entire Southern social and economic structure? Ironically, one leading South Carolina spokesperson for the theory of nullification was Jackson’s own vice president, John C. Calhoun. Talk about divided government. South Carolina went so far as to call a convention to debate and implement nullification of the tariff, and the stage was set for an epic power struggle—the sort of fight a man like Jackson never backed down from.

Jackson may have supported states’ rights on issues as dark as slavery and Indian removal, but he ultimately loved the union he had fought and bled for and would not countenance secession or any challenge to his own supremacy. Whatever his motivations, Jackson’s response to the nullification crisis must stand as his finest hour. Jackson mobilized the Army and threatened to don a uniform and personally lead an invasion of South Carolina. When a man like Jackson—who had killed before—threatened violence, he was seen as deadly serious.

He even told a departing South Carolina congressman to take a message to the convention in that state: Tell them, he said, that “if one drop of blood is shed there in defiance of the laws of the United States, I will hang the first man of them I can get my hands on to the first tree I find!” South Carolina would ultimately back down, and Jackson the savvy politician helped broker a tariff reduction so the state could save face. Through strength of purpose, Jackson had preserved the sanctity of the union and averted civil war. Later historians have even wondered whether, if Jackson were still president in 1860, he could have averted the Civil War of 1861-65.

Abuse of Power: Jackson’s Indian Removal Policy—an American Tragedy

Robert Lindneux’s 1942 depiction of the Trail of Tears, a forced removal that killed thousands of Native Americans as they were marched from the Southeast to Oklahoma.

“… No man entertains kinder feelings towards Indians than Andrew Jackson” —Democratic Congressman Wilson Lumpkin of Georgia

“Build a fire under them [the Cherokee]. When it gets hot enough, they’ll move.”—Andrew Jackson, in conversation with a congressman from Georgia

On other matters, Jackson showed far less political courage and succumbed to his own bigotry and the supposed states’ rights of the South. If nullification was his shining moment, Indian removal must stand as Jackson’s darkest. White settlers in the Ohio Country and, especially, in the old Southwest of Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi had long resented the presence of Native Americans and the federal treaties that granted the tribes land that they have lived on for centuries. Down south this was prime cotton country seen as wasted on “savages.” Some gold was even found on some native lands. Worse still, other tribes traded with free blacks and occasionally harbored runaway slaves. The truth, of course, is that the tribes of what was then the Southwest–the five “civilized” peoples, as they were known (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole)—were increasingly assimilated and lived mostly as farmers in the vein of white society. Some even owned slaves.

Still, so far as Southerners and Westerners were concerned, the Indians had to go. Georgia and Alabama, in particular, had long lobbied for the removal of the Cherokee and Creeks, respectively, but President Adams blocked these desires. Andrew Jackson was another matter. To Jackson, this was a states’ rights and sovereignty issue. Besides, he had fought Indians all his life and held rather paternalistic views of the “savages.” Heck, he sympathized with the Georgians and other Southerners. Georgians, for their part, wanted the Cherokee gone despite past federal guarantees, even though the Constitution clearly granted the right to deal with Indians to the national government. Indeed, a popular song of the day was illustrative of Southern views:

All I want in this creation

Is a pretty little wife and a big plantation

Away up yonder in the Cherokee nation.

In 1830, in another highly sectional vote (the Northeast tended to sympathize with the natives), the Congress barely passed (102-97) the Indian Removal Act. Indeed, without the Three-Fifths Compromise granting extra representation to Southern states in the House of Representatives, the bill would never have passed. Many historians have held the simplistic view that the act authorized Jackson and the federal government to forcibly remove the tribes. That’s not exactly true. The Indian Removal Act provided funds for voluntary (if highly encouraged) migration to Oklahoma but clearly stated the rights of Native Americans to stay on their land if they so chose. Seen this way, Jackson’s later actions in the Indian removal process constituted an extreme abuse of power.

Georgia responded to the protections granted by the Indian Removal Act by stating that, yes, natives could stay if they so insisted, but that they would then have to submit to state laws. Of course, under existing Georgia racial statutes, this would have meant Cherokees couldn’t vote, sue or own property. Essentially, they would be relegated to slavery. And so, in one last desperate attempt, the Cherokee took their grievance to the courts. In Worcester v. Georgia, a rather complicated case, the Supreme Court in a decision led by Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the Cherokee must be protected on lands granted to them by federal treaty. Once again, Jackson saw a challenge, a conspiracy even, against his presidential authority.

Jackson flouted the ruling. He claimed the federal government didn’t have the “power” (ironically) to protect the five tribes. It was a state issue, he said. Furthermore, he removed sympathetic Indian agents from the territories and refused to use force to prevent mobs from attacking the natives. When the Cherokee pleaded with Jackson he displayed little sympathy, stating “you cannot remain where you now are. Circumstances that cannot be controlled, and which are beyond the reach of human laws, render it impossible that you can flourish in the midst of a civilized community. …” That, of course, was patently false. In the Bank War and the nullification crisis, Jackson demonstrated his total willingness to take a stand and use the levers of government to enforce his mandates. Had Jackson chosen to, he could have protected the tribes and enforced the existing statutes.

Instead, Jackson simply defied the law and snubbed the Supreme Court. Scoffing at Justice Marshall’s ruling in Worcester v. Georgia, Jackson supposedly retorted that “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!” This shocking statement constituted a veritable challenge to the very notion of separation of powers enshrined in the Constitution.

The results for the five tribes were tragic. By 1838, the last Cherokee holdouts were evicted by federal troops and marched in harsh weather along the “Trail of Tears” to Oklahoma. It is estimated that 4,000 out of 12,000 Cherokee died en route. As for the less well known case of the Creeks, perhaps 50 percent died during their deportation. Many of the Seminoles of Florida refused to leave and escaped to the Everglades. The U.S. Army would spend decades at war with this hardy tribe, lose thousands of men and spend 10 times more money fighting the Seminoles than it had spent deporting the other four tribes combined.

Indian removal was a bleak chapter in American history. It constituted what we would today call “ethnic cleansing.” Still, apologists remain who claim that we today cannot judge the people of the 19th century because “they didn’t know better,” or “that was the culture back then.” This is easily refuted by pointing out the millions of Americans who opposed the evictions even then. Consider the contemporaneous words of just two of their spokespersons. Henry Clay stated that the Indian Removal Act “threatens to bring a foul and lasting stain upon the good faith, humanity, and character of the nation.” Former President and then Congressman John Quincy Adams went further, declaring that Jackson’s program was “among the heinous sins of this nation, for which God will one day bring [those responsible] to judgment.”

Cues From Above: The Mob in the Age of Jackson

“The President is the direct representative of the American people. He was elected by the people and is responsible to them.” —Andrew Jackson

President Jackson regularly violated American law, violated basic civil liberties and unleashed a storm of public turmoil. He empowered his coarse supporters and (one hopes inadvertently) stoked domestic violence on a massive scale. Jackson was pro-slavery and usually pro-states’ rights, and abhorred the then-small abolitionist movement. He called anti-slavery abolitionists “monsters” who stirred up “the horrors of a servile war” and deserved to “atone for this wicked attempt with their lives.” He asked a session of Congress to authorize federal censorship of abolitionist mail and even went so far as to order the federal postal service to leave southbound abolitionist mail undelivered. Historian David Walker Howe has referred to this as “the largest peacetime violation of civil liberty in U.S. history.”

Jackson’s policies empowered anti-abolitionists (North and South) and helped unleash a storm of mob violence against these activists and, indeed, all anti-Jackson political groups. In 1834, a Jacksonian New York mob drove Whig Party observers away from a polling place. The next day a Whig parade was physically attacked. These events augured three years of such mob violence. Ethnic, racial and religious animosities influenced these attacks, but free blacks and abolitionists were the most common targets. William Lloyd Garrison, a famous abolitionist, was nearly lynched and was saved only when the authorities held him in jail for his own protection. In New York City there was a three-day riot in response to an African-American celebration commemorating the date of slavery’s abolition in the state. The mob violence was so pervasive that urban centers responded by forming the first modern police forces. (These men initially lacked uniforms and were identifiable only by a copper badge—hence the nickname of “cops.”) This is a vital point. Most American police forces were formed not in response to a crime wave, but rather on the heels of white urban riots!

These mobs were made up of Irish and German Catholic immigrants. The members of these groups tended to be staunch Democrats and were registered to vote by Democratic operatives as soon as they debarked their ships. Though poor and stigmatized, these immigrants learned to be white—were informed of their “whiteness”—and passionately enforced the system of racial caste in America. They may be poor, they may be Catholic, but at least they were white; it was not the first time a sentiment of this kind had been held in America.

The riots were deadly, especially in the South. For example, in 1835, 79 Southern mobs killed 63 people; 68 Northern mobs killed 8. Thousands more were injured and millions of dollars in property damage inflicted. President Jackson didn’t personally order this violence, of course, but the perpetrators were nearly always Jacksonians. He had whipped his supporters into such a fervor through his rough, often violent rhetoric that he must bear some responsibility for what followed. He also did little to squelch the violence. During the 1835 Washington, D.C., race riot, for example, he called out federal troops but did not instruct them to protect free blacks, who were the main victims of the attacks. Jacksonian mobs reflected their leader and the era. All this represented the democratic tyranny of a white, male majority over weaker minorities and their social activist allies.

Forever Altered: The Second Party System and the Rise of Modern American Democracy

“Give the people the power, and they are all tyrants as much as kings.” —Federalist Noah Webster, a critic of Jacksonian democratization

By 1834, Jefferson’s Republican Party was permanently shattered. Jackson’s Democratic Republicans took to calling themselves Democrats, while Clay and Adams’ National Republicans chose to take the title of Whigs, which, as noted earlier, is a reference to a British anti-monarchical party (after all, his opponents had hung the label “King Andrew” on Jackson!). The so-called Second Party System had formed, the first system having been the split between Federalists and Republicans in the 1790s. It would last until the Civil War. The Whigs were an interesting lot, truly a coalition of many factions. What really held the Whigs together, though, was their abiding hatred of Jackson.

It was during this Second Party System that modern notions of political partisanship developed. The two sides loathed one another, and Americans were just about evenly split in their loyalties. Both the Whigs and Jacksonian Democrats had long-term effects on the United States’ political culture. Jackson’s legacy was his party’s public electioneering and the five Supreme Court justices he appointed. These Democratic judges—including Chief Justice Roger Taney (who would later author the infamous Dred Scott decision)—would move the court in a pro-slavery, states’ rights direction for a full generation.

It’s hard to judge these two parties by modern standards, and their positions were rather paradoxical. The Jacksonians did favor more white, male democratization but were completely illiberal on race and gender. The Whigs distrusted the will of the people and probably preferred the exclusion of some men from the political process; yet they were more tolerant in other ways and willing to protect the political rights of free blacks. Which was the better position? It’s hard to know. Perhaps the Whig tendency toward the exclusion of poor whites was inexcusable; then again, given the outcomes, perhaps they were right to fear the masses.

A cartoon depicting the Whig candidate for president, William Henry Harrison, as a commoner who distilled hard cider on the frontier. In reality he was a wealthy Virginia planter. The Whig deception was part of a successful campaign to “out-Jackson” the Democrats in seeking the “common man” vote in the 1840 election.

What’s certain is this: In the end, the Jacksonian method of politics and campaigning had won out. Desperate to win the presidency, by 1840 the Whigs had begun trying to “out-Jackson” the Jacksonians. They held party conventions, publicly campaigned, and even sought to appeal to the “common man.” Indeed, in 1840 the Whigs tried—and succeeded—in running a Jackson of their own. The victorious Whig candidate, William Henry Harrison, was himself a war hero (a veteran of the Battle of Tippecanoe, a successful engagement with Indians in the old Northwest). He even had a catchy slogan: “Tippecanoe and Tyler too!”—a reference to John Tyler, the Whigs’ vice presidential candidate. Furthermore, Whig cartoons labeled Harrison the “hard cider” (a popular alcoholic beverage) candidate and pictured him in front of humble, rustic log cabins. Here was the Whigs’ own “self-made man.” It was a deception, of course. Harrison came from a wealthy planter family in Virginia and lived in a mansion. No matter, it worked and the Whigs won their first election.

* * *

Looking back from 2018, it is scary that the contemporary system of two major parties so closely resembles the fierce partisan divides of the Jacksonian era. After all, the division of American loyalties and inability of the two parties to work together led, within three decades, to a horrendous civil war. Jackson, as Donald Trump is now, was a remarkably divisive figure. He remains divisive among historians who still debate his legacy.

Though Jackson was a compelling and popular figure, and counted numerous achievements (he was the first and only president to ever pay off the entire federal debt), his flaws were many. Try as apologist historians may, one cannot disentangle Jackson’s white democratization from his legacy of Indian removal, slavery, racism and mob violence. Indeed, white supremacy stood at the very center of Jacksonian democracy; by design, the “many” wore their skin color as a badge of honor and mark of superiority over the “few,” the lesser souls of America. In that way, ironically, Jackson and his acolytes achieved the dream that wealthy Southern elites had dreamed since the founding of Jamestown: to tie the loyalties of poor whites with the prosperity and fortunes of their social betters. Most whites were now united behind a new identity of whiteness-as-Americanism, and excluded women, blacks and natives from the collective community.

In the 21st century, as the U.S. body politic continues to grapple with issues of race, immigration, gender and sexual orientation, and as this country is being led by a man with a character remarkably similar to Andrew Jackson’s, perhaps the time is right to assess the triumphs and ills of our great democratic experiment. But here’s a word of warning: Be careful in reassessing the American past. What you find may be disturbing.

Andrew Jackson famously claimed that we should “never believe that the great body of the citizens can deliberately intend to do wrong.” Observing the reality of his time, and of our own, I’m not so sure. This much, however, is true: Jackson was many things, but this is sure—he was dangerous. So, potentially, are all powerful presidents … even, maybe especially, the popular ones.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

• Alfred A. Cave, “Abuse of Power: Andrew Jackson and the Indian Removal Act of 1830,” The Historian 65, No. 6 (Winter 2003).

• James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 10: “The Opening of America, 1815-1850” (2011).

• Lacy K. Ford, Jr., “Making the ‘White Man’s Country’ White: Race, Slavery, and State-Building in the Jacksonian South,” Journal of the Early Republic 19, No. 4 (Winter 1999).

•Daniel Walker Howe, “What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848” (2007).

• Jill Lepore, “People Power: Revisiting the Origins of American Democracy,” New Yorker (October 2005).

• Seth Rockman, “Jacksonian America,” in “American History Now” (2011), Eric Foner and Lisa McGirr, ed.

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Police: 3 Confirmed Dead in Northern California Wildfire

REDDING, Calif. — The Latest on wildfires burning in California (all times local):

1:15 p.m.

Family members say three people missing in a Northern California wildfire have been confirmed dead.

Sherry Bledsoe said Saturday that her two children and her grandmother died in the fire near Redding.

The fatalities bring the death toll to five since the massive blaze started burning Monday about 100 miles (161 kilometers) south of the Oregon border.

The dead were identified as 70-year-old Melody Bledsoe and her great-grandchildren, 5-year-old James Roberts and 4-year-old Emily Roberts.

Family members had been desperately looking for them since flames leveled the home where they were stranded on Thursday.

Bledsoe’s husband was out getting supplies at the store when the boy called him and said he needed to get home because the fire was approaching.

___

12:45 p.m.

Police in a Northern California city say they have been unable to locate 14 people, including a 70-year-old woman and her young great-grandchildren, amid a raging wildfire.

Redding Police Sgt. Todd Cogle said he expects most of the 14 to be safe since their homes survived the Shasta County wildfire. He says some may be having communication issues.

Cogle said he could not comment on Melody Bledsoe and 5-year-old James Roberts and 4-year-old Emily Roberts, who remain missing. He said the Shasta County Sheriff’s Office is investigating.

Police have surrounded the Bledsoe property with crime scene tape.

An investigator Saturday wouldn’t say if any remains had been found.

The wildfire that started Monday has displaced at least 37,000 people.

___

12:20 p.m.

A shelter for people displaced by a massive blaze in Northern California has reached full capacity as fire authorities order more evacuations.

Peter Griggs, a spokesman for Shasta College in Redding, says the evacuation center at the school reached maximum capacity Saturday and is housing 500 people.

The college’s gymnasium is filled with cots and American Red Cross volunteers are providing food, water and medical and mental health services.

California fire officials say more mandatory evacuations were ordered Saturday afternoon for communities south of Redding and three other shelters are still taking evacuees.

The raging fire that started Monday has displaced at least 37,000 people.

___

11:20 a.m.

Police have surrounded a burned-out property with crime scene tape where two children and their great-grandmother are unaccounted for after a Northern California wildfire destroyed their home.

An investigator Saturday wouldn’t say if any remains had been found, but police closed off the road to the house. Family members have been desperately seeking 70-year-old Melody Bledsoe and two of her great-grandchildren who lived with her at the Quartz Hill Road home in Redding.

Jason Decker, a boyfriend of a relative, says that Bledsoe’s husband, Ed, was at the store Thursday when his 5-year-old grandson, James Roberts, called to say he needed to come right home because the fire was close.

Decker says that when Ed Bledsoe tried to drive home, police wouldn’t let him through a roadblock because the fire was raging.

Decker says Melody, the boy and his 4-year-old sister, Emily Roberts, are all missing.

___

11 a.m.

President Donald Trump has issued an emergency declaration for California allowing counties affected by wildfires to receive federal assistance.

A White House statement issued Saturday says the declaration allows the Federal Emergency Management Agency to provide necessary equipment and resources.

The declaration highlights a massive wildfire in Northern California that nearly doubled overnight.

California fire officials say more than 10,000 firefighters are working to stop the progress of 14 large wildfires across the state.

They say the blazes have killed three firefighters and destroyed more than 500 structures.

___

9:55 a.m.

Two blazes burning 30 miles (50 kilometers) apart are threatening dozens of buildings and have prompted mandatory evacuations in Northern California’s Mendocino County.

The blazes that began Friday are burning about 120 miles (200 kilometers) southwest of Redding, California, which is near a massive wildfire that as thousands of under evacuation orders.

The Mendocino County Sheriff’s Office says mandatory evacuations are in place for people living an area north of Highway 175 near Hopland, California.

Officials in neighboring Lake County say residents of Benmore Valley were ordered to evacuate Saturday morning.

They say the blazes are threatening more than 350 buildings.

___

This item has been corrected to show blaze is burning near Hopland, not Ukiah, California.

___

9 a.m.

Officials say a deadly blaze in Northern California almost doubled in size overnight, but is moving away from populated areas.

Chris Anthony, deputy chief of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, said Saturday the so-called Carr Fire burning in Shasta County has scorched 125 square miles (320 square kilometers). It is 5 percent contained.

The blaze covered 75 square miles (194 square kilometers) Friday night.

Anthony says winds are fueling the fire but also pushing it away from Redding, a city of 90,000, and other populated areas. Thousands of people remain under evacuation orders, including the small towns of Ono and Igo.

The explosive wildfire in Northern California has killed two firefighters and destroyed 500 buildings. Another 5,000 buildings remain under threat.

___

7 a.m.

A wildfire in far northern California has destroyed at least 500 structures and remains mostly uncontained. The air chokes with the smell of smoke and chemicals. The smoldering remains are still too hot to sift through. And the weather report promises more hot dry conditions, bad news for firefighters working the so-called Carr Fire.

The wildfire has wiped out the small community of Keswick, swept through the historic Gold Rush town of Shasta and hit homes in Redding. Nearly 5,000 more homes are threatened, and about 37,000 people remain under evacuation orders.

Two firefighters were killed as the flames roared through. Other large fires are burning outside Yosemite National Park and in the San Jacinto Mountains. The National Interagency Fire Center is tracking 89 active large fires in 14 states.

In Reality, Every Night Is ‘Purge’ Night

“The Purge” franchise is the most politically relevant work of modern pop culture. The four films—“The Purge,” “The Purge: Anarchy,” “The Purge: Election Year” and the recently released “The First Purge”—feature protagonists who are poor, homeless, black and brown, immigrants, criminals and otherwise marginalized people fighting to survive eliminationist violence by white, wealthy, upper-class, educated killers and the fascist government that supports them. “The Purge” series makes explicit the implicit violence of capitalism, and every horror inflicted upon the protagonists echoes the suffering of people in the real world.

The premise of the first film in the series, “The Purge,” is simple: For one night, all crime is legal in America. Assault, rape and murder are fair game. Citizens are encouraged to “unleash the beast” and abuse their fellow Americans as they see fit. The New Founding Fathers of America—the ruling political party in the series’ dystopian U.S.—began the annual event ostensibly to help Americans purge their deviant desires. After this cathartic one-night orgy of violence, people would supposedly return to their normal lives rid of their negative impulses and be good citizens for the rest of the year.

This concept could easily be the germ of a right-wing fantasy about how police and prisons are the only thing standing between good folks and hordes of violent savages. However, what becomes clear throughout the series is that the purge exists only to benefit the privileged few: The haves can spend the night in safe rooms or on the streets with military-grade arsenals, while the have-nots have no protection and are hunted for sport. “The Purge” is thus a fable in which the violence that classism, racism and capitalism inflict every day is distilled into just one night.

“The Purge” (2013) follows the upper-middle-class, pro-purge Sandin family. They support the purge politically but do not actively participate in the festivities, instead choosing to fortify their home with expensive equipment available only to those of their economic class. They are safe, secure and ignorant in their suburban fortress—until a bloody man shows up at their door asking for help.

The unnamed stranger is a homeless black man who has survived an attack by a group of young, rich, white purgers, and he immediately becomes the moral center of the film. By seeing the stranger’s humanity, the Sandins realize the cruelty of the purge, and it is only through their protection of him from his upper-class attackers that they prove their worth.

While the wealthy can turn their homes into virtual fortresses and hire private security, those outside the suburbs are not safe anywhere. “The Purge: Anarchy” (2014) shows how the other half lives on purge night. While street gangs mostly keep to themselves, government-backed death squads stalk dilapidated apartment buildings and hunt down the poor.

When the protagonists are chased by a group of spooky black teenagers, it is revealed that they are not purgers but merely middlemen. The gang is capturing people on purge nights to sell them to a group of the megawealthy, who commit their purge murders over plates of foie gras.

“The Purge: Election Year” (2016) was a creative and political departure. It focused more on action than horror, and the proletarian revolution to end the purge proposed near the end of “The Purge: Anarchy” was ultimately abandoned for a political appeal. The film ends with the election of an anti-purge candidate to the presidency, but riots from pro-purge voters are reported to be taking place during the credits.

The fourth and newest film, “The First Purge” (2018), is the most explicitly political and topical film of the series. Director Gerard McMurray and writer James DeMonaco grounded this prequel in a pre-purge world that is not much different from ours. The 1998 dragging death of James Byrd Jr. in Texas, Black Lives Matter, the 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Va., the NFL protests, the Tuskegee experiments and other racial injustices are referred to liberally throughout the film, often in shocking ways.