Chris Hedges's Blog, page 496

August 19, 2018

Chemical Plant Disaster Agency in Trump’s Crosshairs

On a warm morning in April, workers at a Wisconsin oil refinery were conducting a routine shutdown for maintenance. Suddenly, a gasoline cracking unit exploded, and the workers watched in horror as a huge fireball ripped through the plant. They ran for their lives, barely escaping the blast.

Debris from the explosion ruptured a tank, which spilled more than half a million gallons of hot asphalt that burst into flames and burned for nine hours. Black smoke spread over the port town of Superior. Eleven workers were injured, and about 40,000 people were evacuated from nearby homes and schools.

Within 24 hours of the explosion at the Husky Energy Inc. refinery, a small team of federal investigators arrived. Their mission, Superior Mayor Jim Paine reassured residents, was to “find out what happened and how we prevent it in the future.”

Earlier this month, after a three-month probe, the investigators from the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board concluded that a faulty valve at the plant caused the explosion. The board plans to issue recommendations that aim to prevent such an accident from happening again at a refinery.

But despite the warm welcome in Superior – and wide recognition of its expertise in chemical plant disasters – this small, independent federal agency is teetering on the brink of elimination.

The Trump administration has twice in its budgets attempted to shut down the Chemical Safety Board; so far, Congress has rejected the attempts. For the 2019 fiscal year, both the House and Senate have proposed restoring full funding.

But the assaults appear to be taking a toll. Hostility from the Trump administration and disarray from its efforts to eliminate the agency follow years of leadership turmoil and high turnover that started during the Obama administration. In 2015, its chairman, who was embroiled in a congressional investigation into poor management, resigned under pressure – yet leadership problems remain.

Combined, these problems threaten to cripple the agency’s investigations of chemical plant disasters, according to interviews and reports obtained by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting. A report from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s inspector general says the turmoil “if not addressed, may seriously impede the agency’s ability to achieve its mission efficiently and effectively.”

The Trump administration argues that the Chemical Safety Board duplicates the work of other federal agencies. Administration budget documents also cite unspecified complaints from industry and other federal agencies about the board’s recommendations for new regulations of the chemical industry.

Health and safety advocates and labor unions say the board is essential because aging oil and chemical facilities have had some of the deadliest and costliest industrial accidents in the past two decades.

More than 12,000 plants store or handle toxic or flammable chemicals in the United States. Under worst-case scenarios for more than 2,500 of these facilities, between 10,000 and 1 million people could be harmed, according to a 2012 Congressional Research Service report. An estimated 4.6 million children at nearly 10,000 schools are within 1 mile of a plant that handles hazardous chemicals, according to the Center for Effective Government.

Local officials, including emergency responders, often have little information about the chemicals and safety conditions at the plants in their communities. The chemical industry keeps much of this information under wraps, invoking national security and a need to protect confidential business information.

“Millions of people live and work in the shadow of high-risk chemical plants that store and use highly hazardous chemicals,” said Jordan Barab, a former board investigator who now blogs about worker safety.

Little-Known Federal Agency

Over its 20-year history, the Chemical Safety Board has investigated more than 150 explosions, fires and spills at chemical plants and oil refineries.

Included are the 2012 Chevron refinery fire in Richmond, California, whichdrove about 15,000 people to seek medical care, and the 2013 West Fertilizer Co. explosion in Texas, where 15 people, including 12 emergency responders, died and 350 homes were damaged or destroyed.

Similar to the National Transportation Safety Board, which probes airplane, ship and railroad accidents, the Chemical Safety Board has no regulatory authority and does not issue fines or prosecute companies. But its findings often point to problems that other agencies may act upon: It has issued 815 recommendations designed to prevent tragedies at oil and chemical plants.

Established by Congress in the wake of two chemical plant explosions in Texas that killed or injured more than 350 workers, the board has a staff of 35 and a budget of $11 million a year – miniscule compared with other federal agencies. For the next fiscal year, the House has proposed $12 million in funding, while the Senate has proposed $11 million.

Mike Wright, director of health, safety and environment for the United Steelworkers, has called the board “one of the best bargains in Washington. If it has prevented even one accident, it has saved far more money than its budget over its entire history.”

The Trump administration has justified its proposal to eliminate the agency by saying other agencies, such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the EPA, already do similar investigative work.

“Congress intended CSB to be an investigative arm that is wholly independent of the rulemaking, inspection, and enforcement authorities of its partner agencies,” according to Trump administration budget documents. “While CSB has done some useful work on its investigations, its overlap with other agency investigative authorities has often generated friction. The previous management sought to focus CSB’s recommendations on the need for greater regulation of industry, which frustrated both regulators and industry.”

There apparently was friction between two federal agencies during the investigation of the West Fertilizer disaster in Texas. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives concluded that the cause was arson, while the Chemical Safety Board reported that unsafe storage practices for combustible materials contributed to the explosion and a lack of sprinklers spread the flames. The bureau kept Chemical Safety Board investigators away from the site for four weeks, which hampered their ability to investigate the explosion, according to a board report.

The White House did not disclose any evidence that industry groups or companies have complained about the board’s investigations or recommendations.

The American Chemistry Council, which represents chemical companies, told Reveal in a statement that its members “find considerable value in the CSB’s work – especially the reports and materials generated by the Board as part of its investigations.” The investigations “raise industry awareness to potential problems” and “have benefitted ACC, its members and the public.” The industry group, however, declined to answer questions.

But former board Chairman Rafael Moure-Eraso, who resigned under pressure in 2015, blames his ouster on retaliation by some Republican members of Congress for his agency’s aggressive investigations of oil company accidents, including the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico; the 2010 Tesoro refinery accident in Anacortes, Washington; and the 2012 Chevron refinery fire in California.

In those three investigations, the board made recommendations “that were opposed by industry groups … and their friendly congressmen in the U.S. House of Representatives,” Moure-Eraso said. The overarching recommendation was that federal regulations should require refineries and offshore oil platforms to continually meet higher safety standards and reduce risk.

Moure-Eraso said industry groups welcome investigations because they improve safety for their workers and neighbors. But, he added, the groups oppose some of the board’s recommendations.

“When changes on improving protections require regulation, the support abruptly ends,” he said.

For example, after the Texas fertilizer plant explosion, the Obama administration enacted safety measures requiring more detailed public reporting of chemical hazards and improved safety training. But under President Donald Trump, former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt moved to rescind most of the new rules, saying they would cost the industry too much – an estimated $88 million a year – and could make public information about chemical plants that would be useful to terrorists.

Moure-Eraso said the board’s highly technical investigations are not duplicated by federal regulatory agencies, which “obviously have failed to prevent some major chemical accidents.”

The EPA inspector general’s office under the Trump administration appears to agree. In a June report, the office said the board’s work complements other agencies’ work because “the root causes of an incident go beyond whether there was a violation of a regulation.”

Adam Carlesco, staff counsel for the nonprofit Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, which represents government employees, said the chemical industry has stalled efforts to improve reporting of chemical plant accidents.

His group has sued to enforce a part of the board’s statutory authority that says it must compel companies to report plant accidents directly to the board. When the board tried to do this in 2009, industry groups called it burdensome. The pushback eventually led the board to drop the effort.

‘Agency in Disarray’

During the Obama administration, two House committees investigated charges that the board under Moure-Eraso had an abusive and hostile work environment and conspired to punish agency whistleblowers. No details about the whistleblowers were released publicly.

Also, the EPA’s inspector general criticized the number and pace of investigations. A 2014 report by the two House committees called it an “agency in disarray.”

The turmoil continues. Since January, the board has lost seven of its 18 investigators. In June, its chairwoman since 2015, Vanessa Sutherland, resigned and took a vice presidency job with a railroad company. And the EPA inspector general’s June report identified more mismanagement problems, including evidence that an unidentified board member improperly shared information with a labor union representative.

The inspector general’s office reported “negative impact from the President’s continued proposal to eliminate the agency.”

“This budget uncertainty impedes the CSB’s ability to attract, hire and retain staff,” according to the report, which added that the board “should continue to work with Congress toward achieving funding needs wherever possible.”

Earlier this month, U.S. Reps. Trey Gowdy, R-S.C., chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, and Greg Gianforte, R-Mont., chairman of the Interior, Energy and Environment Subcommittee, wrote the White House asking that Trump nominate a new chairman because the vacancy “could plunge the agency into further chaos.”

The board members and chairman are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

“Recent reports indicate mismanagement and improper conduct continue to undermine the CSB’s mission,” the congressmen wrote.

Living in Fear in Superior

Debates about budgets and board leadership are not much of a balm for people who live with oil and chemical plants in their communities.

Residents of the Twin Ports area – the cities of Superior, population 27,000, and Duluth, Minnesota – still live in fear of the Husky Energy plant after the April accident.

Those who live near the refinery said the explosion was so powerful that they could feel the detonation. They now understand a harsh reality shared by millions of Americans: An accident at a chemical plant or refinery in their community could level their homes or injure them with toxic gases or smoke.

“I watched this … scary thing happen off my back porch,” Superior resident Renee Goodrich said at a City Council meeting a few days after the accident.

“Looking back, the normal pace of that day was terrifying,” said resident Gabriela Vo. “Were the citizens of Pompeii just going about their daily lives when the fateful volcano erupted? The smoke alone was enough to raise health concerns, let alone the possibility of the town blowing up.”

The black smoke posed some health risks due to high concentrations of fine particles, but after it cleared, monitoring by company and county officials showed no air pollutants violated health standards.

Husky pledged cooperation and transparency with officials, and the Chemical Safety Board investigators said the company granted them full access to its plant and records. The company declined to answer questions from Reveal, citing the ongoing investigation.

The investigators concluded that a worn-out valve in a fluid catalytic cracking unit – equipment used to refine gasoline – allowed air to contact flammable chemicals, triggering the explosion. The board now is developing its recommendations on how to avoid such accidents.

It could have been a catastrophe: The board’s investigators reported that debris flew 200 feet into an asphalt tank. A storage tank filled with highly toxic hydrogen fluoride sits in the same area, just 150 feet away from the cracking unit that exploded. It was undamaged. If it had ruptured, the fumes could have caused severe injuries or deaths.

The company said the plant has a system of safeguards that would have prevented release of the gas, which is used to make high-octane gasoline, even if the tank had been punctured.

“The (hydrogen fluoride) storage tank is designed with multiple protection levels including a dedicated deluge system that douses the tank with a water curtain to keep it cooled and mitigate potential releases,” the company said in a statement.

But many locals – including Pat Farrell, a University of Minnesota Duluth soil scientist who is pushing for safety changes – think the town got lucky.

“One piece of shrapnel would have been all that was necessary for a major disaster, the scale of which the Twin Ports here have never seen,” Farrell said.

Costly Research Unlikely to Pay Off for Nuclear Industry

On both sides of the Atlantic billions of dollars are being poured into developing small modular reactors. But it seems increasingly unlikely that they will ever be commercially viable.

The idea is to build dozens of the reactors (SMRs) in factories in kit form, to be assembled on site, thereby reducing their costs, a bit like the mass production of cars. The problem is finding a market big enough to justify the building of a factory to build nuclear power station kits.

For the last 60 years the trend has been to build ever-larger nuclear reactors, hoping that they would pump out so much power that their output would be cheaper per unit than power from smaller stations. However, the cost of large stations has escalated so much that without massive government subsidies they will never be built, because they are not commercially viable.

To get costs down, small factory-built reactors seemed the answer. It is not new technology, and efforts to introduce it are nothing new either, with UK hopes high just a few years ago. Small reactors have been built for decades for nuclear submarine propulsion and for ships like icebreakers, but for civilian use they have to produce electricity more cheaply than their renewable competitors, wind and solar power.

One of the problems for nuclear weapons states is that they need a workforce of highly skilled engineers and scientists, both to maintain their submarine fleets and constantly to update the nuclear warheads, which degrade over time. So maintaining a civil nuclear industry means there is always a large pool of people with the required training.

Although in the past the UK and US governments have both claimed there is no link between civil and military nuclear industries, it is clear that a skills shortage is now a problem.

It seems that both the industry and the two governments have believed SMRs would be able to solve the shortage and also provide electricity at competitive rates, benefitting from the mass production of components in controlled environments and assembling reactors much like flat-pack furniture.

This is now the official blueprint for success – even though there are no prototypes yet to prove the technology works reliably. But even before that happens, there are serious doubts about whether there is a market for these reactors.

Among the most advanced countries on SMR development are the US, the UK and Canada. Russia has already built SMRs and deployed one of them as a floating power station in the Arctic. But whether this is an economic way of producing power for Russia is not known.

Finding Investors

A number of companies in the UK and North America are developing SMRs, and prototypes are expected to be up and running as early as 2025. However, the next big step is getting investment in a factory to build them, which will mean getting enough advance orders to justify the cost.

A group of pro-nuclear US scientists, who believe that nuclear technology is vital to fight climate change, have concluded that there is not a large enough market to make SMRS work.

Their report, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, says that large reactors will be phased out on economic grounds, and that the market for SMRs is too small to be viable. On a market for the possible export of the hundreds of SMRs needed to reach viability, they say none large enough exists.

They conclude: “It should be a source of profound concern for all who care about climate change that, for entirely predictable and resolvable reasons, the United States appears set to virtually lose nuclear power, and thus a wedge of reliable and low-carbon energy, over the next few decades.”

Doubts Listed

In the UK, where the government in June poured £200 million ($263.8) into SMR development, a parliamentary briefing paper issued in July lists a whole raft of reasons why the technology may not find a market.

The paper’s authors doubt that a mass-produced reactor could be suitable for every site chosen; there might, for instance, be local conditions requiring extra safety features.

They also doubt that there is enough of a market for SMRs in the UK to justify building a factory to produce them, because of public opposition to nuclear power and the reactors’ proximity to population centres. And although the industry and the government believe an export market exists, the report suggests this is optimistic, partly because so many countries have already rejected nuclear power.

The paper says those countries still keen on buying the technology often have no experience of the nuclear industry. It suggests too that there may be international alarm about nuclear proliferation in some markets.

August 18, 2018

ICE Arrests Man Driving His Pregnant Wife to the Hospital

Joel Arrona-Lara was driving his wife to deliver their baby when he was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, Los Angeles-area station CBS2 reported Friday. He had stopped to get gas at a San Bernardino service station when he was approached by ICE officers demanding identification.

Arrona-Lara’s wife, Maria del Carmen Venegas, was able to provide identification, but her husband could not. Venegas offered to go back and get it for the officers, explaining he and his wife had left their home in a rush, but the agents weren’t interested.

Instead, CBS2 reports, “the agents then asked Arrona to exit the vehicle, searched the car for weapons, and put Arrona into custody, leaving [Venegas] alone at the gas station.”

Venegas had to drive herself to the hospital.

“I feel very bad right now,” Venegas told CBS2 from the hospital, holding her newborn son. “My husband needs to be here. He had to wait for his son for so long, and someone just took him away.”

Arrona-Lara is currently being held in a detention center in downtown Los Angeles. ICE confirmed the detention to the HuffPost on Saturday, and described Arrona-Lara as “a Mexican citizen living in the United States without documents.”

ICE also told HuffPost it is beginning removal proceedings for Arrona-Lara. “ICE continues to focus its enforcement resources on individuals who pose a threat to national security, public safety and border security,” the agency said in a statement. Explaining their reasoning for this and other detentions, ICE continued:

ICE conducts targeted immigration enforcement in compliance with federal law and agency policy. However, ICE will no longer exempt classes or categories of removable aliens from potential enforcement. All of those in violation of the immigration laws may be subject to immigration arrest, detention and, if found removable by final order, removal from the United States.

In a Spanish-language interview with Univision, Emilio Amaya García, director of the Community Services Center of San Bernardino and Arrona-Lara’s lawyer, highlighted ICE’s “lack of sensitivity.” She continued, “In this case, not only could [ICE] have endangered the life of the mother, but also that of the child, who is a citizen of this country.”

Right-Wing, Left-Wing Protesters Face Off in Seattle

SEATTLE —Right-wing demonstrators gathered Saturday in Seattle for a “Liberty or Death” rally that drew counter-protesters from the left while dozens of police kept the two sides separated.

The right-wing groups Washington 3 Percenters and Patriot Prayer were holding the rally outside Seattle City Hall to protest an effort to launch a gun-control initiative that would raise the age in Washington state for people buying semi-automatic rifles.

The left-wing groups Organized Workers for Labor Solidarity, Radical Women and the Freedom Socialist Party were rallying at the same site.

Hundreds of protesters on each side of the street were separated by Saturday afternoon by metal barriers and police officers as the left-wing protesters yelled and used cowbells and sirens to try to drown out speeches from the right-wing side.

Police arrested at least three people on the counter-protester side as the demonstrations continued, but it wasn’t immediately clear why. One person on the right-wing group side was treated for an injury at the scene.

Additional police also arrived, including police in riot gear with batons who took up positions in the street. Bicycle officers lined up their bikes as a type of moving barrier to keep protesters from entering the street, which remained open to traffic.

The gun-control initiative would boost the age for the purchase of semi-automatic rifles from 18 to 21 and would expand the background checks for those purchases. The measure would also require people to complete a firearm safety training course and create standards for safely storing firearms.

A judge on Friday, however, threw out 300,000 signatures needed to put the initiative on the November ballot, saying the petition’s format did not follow election law. The Alliance for Gun Responsibility, the group behind the initiative, has filed a notice of appeal with the Washington Supreme Court.

The protest came two weeks after police in riot gear in Portland, Oregon, tried to keep right-wing and left-wing groups apart. The effort mostly succeeded, but police were accused of being heavy-handed, prompting the city’s new police chief to order a review of officers’ use of force.

American History for Truthdiggers: The Fraudulent Mexican-American War (1846-48)

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 15th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 15 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14;.

* * *

The United States of America conquered half of Mexico. There isn’t any way around that fact. The regions of the U.S. most affected by “illegal” immigration—California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas—were once part of the Republic of Mexico. They would have remained so if not for the Mexican-American War (1846-48). Those are the facts, but they hardly tell the story. Few Americans know much about this war, rarely question U.S. motives in the conflict and certainly never consider that much of America’s land—from sea to shining sea—was conquered.

Many readers will dispute this interpretation. Conquest is the natural order of the world, the inevitable outgrowth of clashing civilizations, they will insist. Perhaps. But if true, where does the conquest end, and how can the U.S. proudly celebrate its defense of Europe against the invasions by Germany and/or the Soviet Union? This line of militaristic reasoning—one held by many senior conservative policymakers even today—rests on the slipperiest of slopes. Certainly nations, like individuals, must adhere to a certain moral code, a social contract of behavior.

In this installment I will argue that American politicians and soldiers manufactured a war with Mexico, sold it to the public and then proceeded to conquer their southern neighbor. They were motivated by dreams of cheap farmland, California ports and the expansion of the cotton economy along with its peculiar partner, the institution of slavery. Our forebears succeeded, and they won an empire. Only in the process they may have lost something far more valuable in the moral realm.

(Mis)Remember the Alamo!: Texas and the Road to War

“The Fall of the Alamo” or “Crockett’s Last Stand,” by Robert Jenkins Onderdonk. This 1903 painting, on display in the Texas governor’s mansion, shows the famed frontiersman, at center wielding a rifle, battling to the death. Mexican accounts hold that Davy Crockett surrendered and later was executed. (Wikimedia Commons)

We all know the comforting tale. It has been depicted in countless Hollywood films starring the likes of John Wayne, Alec Baldwin and Billy Bob Thornton. “Remember the Alamo!” It remains a potent battle cry, especially in Texas, but also across the American continent. In the comforting tale, a myth really, a couple of hundred Texans, fighting for their freedom against a dictator’s numerically superior force, lost a battle but won war—inflicting such losses that Mexico’s defeat became inevitable. Never, in this telling, is the word “slavery” or the term “illegal immigration” mentioned. There is no room in the legend for critical thinking or fresh analysis. But since the independence and acquisition of Texas caused the Mexican-American War, we must dig deeper and reveal the messy truth.

Until 1836, Texas was a distant northern province of the new Mexican Republic, a republic that had only recently won its independence from the Spanish Empire, in 1821. The territory was full of hostile Indian tribes and a few thousand mestizos and Spaniards. It was difficult to rule, and harder to settle—but it was indisputably Mexican land. Only, Americans had long had their eyes on Texas. Some argued that it was included (it wasn’t) in the Louisiana Purchase, and “Old Hickory” himself, Andrew Jackson, wanted it badly. Indeed, his dear friend and protégé Sam Houston would later fight the Mexicans and preside as a president of the nascent Texan Republic. Thirty-two years before the Texan Revolution of Anglo settlers against the Mexican government, in 1803, Thomas Jefferson had even declared that [the Spanish borderlands] “are ours the first moment war is forced upon us.” Jefferson was prescient but only partly correct: War would come, in Texas in fact, but it would not be forced upon the American settlers.

Others besides politicians coveted Texas. In 1819, a filibusterer (one who leads unsanctioned adventures to conquer foreign lands), an American named James Long, led an illegal invasion and tried but failed to establish an Anglo republic in Texas. Then, in 1821, Mexico’s brand new government made what proved to be a fatal mistake: It opened the borders to legal American immigration. It did so to help develop the land and create a buffer against the powerful Comanche tribe of West Texas but stipulated that the Anglos must declare loyalty to Mexico and convert to Catholicism. The Mexicans should have known better.

The Mexican Republic abolished slavery in 1829, more than three decades before its “enlightened” northern neighbor. Unfortunately nearly all the Anglo settlers, who were by now flooding into the province, hailed from the slaveholding American South and had brought along many chattel slaves. By 1830, there were 20,000 American settlers and 2,000 slaves compared with just 5,000 Mexican inhabitants. The settlers never intended to follow Mexican law or free their slaves, and so they didn’t. Not really anyway. Most officially “freed” their black slaves and immediately forced them to sign a lifelong indentured servitude contract. It was simply American slavery by another name.

After Santa Anna—Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón, an authoritarian but populist president—seized power, his centralizing instincts and attempts to enforce Mexican policies (such as conversion to Catholicism and the ban on slavery) led the pro-autonomy federalists in Texas (most of whom were Americans) to rebel. It was 1835, and by then there were even more Americans in Texas: 35,000, in fact, outnumbering the Hispanics nearly 10 to 1. Many of the new settlers had broken the law, entering Texas after Santa Anna had ordered the border closed, as was his sovereign right to do.

What followed was a political, racial and religious war pitting white supremacist, Protestant Anglos against a centralizing Mexican republic led by a would-be despot. The Texan War of Independence (1835-36) was largely fought with American money, American volunteers and American arms (even then a prolific resource in the United States). The war was never truly limited to Texas, Tejanos or Mexican provincial politics. It was what we now call a proxy war for land waged between the U.S. and the Mexican Republic.

Furthermore, though Santa Anna was authoritarian, certain Texans saw him as their best hope for freedom. As Santa Anna’s army marched north, many slaves along the Brazos River saw an opportunity and rebelled. Most were killed, some captured and later hanged. And, while slavery was not, by itself, the proximate cause of the Texan Rebellion, it certainly played a significant role. As the Mexican leader marched north with his 6,000 conscripts, one Texas newspaper declared that “[Santa Anna’s] merciless soldiery” was coming “to give liberty to our slaves, and to make slaves of ourselves.” So, once again—as in America’s earlier revolution against Britain—white Americans clamored about their own liberty and feared to death that the same might be granted to their slaves. When (spoiler alert) Santa Anna’s army was eventually defeated, the Mexican retreat gathered numbers as many slave escapees and fearful Hispanics sought their own version of “freedom” south of the Anglo settlements.

Surely, the most evocative image of the Texas War of Independence was the heroic stand of 180 Texans at the Alamo. “Alamo” has entered the American lexicon as a term for any hopeless, yet gallant, stand. And, no doubt, the outnumbered defenders demonstrated courage in their doomed stand. The slightly less than 200 defenders were led by a 26-year-old failed lawyer named William Barret Travis and included the famed frontiersman Davy Crockett, a former Whig member of the U.S. House of Representatives. All would be killed. Still, the battle wasn’t as one-sided or important as the mythos would have it. The defenders actually held one of the strongest fortifications in the Southwest, had more and superior cannons than the attackers and were armed mainly with rifles that far outranged the outdated Mexican muskets. Additionally, the Mexicans were mostly underfed, undersupplied conscripts who often had been forced to enlist and had marched north some 1,000 miles into a difficult fight. Despite inflicting disproportionate casualties on the Mexicans, the stand at the Alamo delayed Santa Anna by only four days. Furthermore, despite the prevalent “last stand” imagery, at least seven defenders (according to credible Mexican accounts long ignored)—probably including Crockett himself—surrendered and were executed.

None of this detracts from the courage of any man defending a position when outnumbered at least 10 to 1, but the diligent historian must reframe the battle. The men inside the Alamo walls were pro-slavery insurgents. As applied to them, “Texan,” in any real sense, is a misnomer. Two-thirds were recent arrivals from the United States and never intended to submit to sovereign Mexican authority. What the Battle of the Alamo did do was whip up a fury of nationalism in the U.S. and cause thousands more recruits to illegally “jump the border”—oh, the irony—and join the rebellion in Texas.

Eventually, Santa Anna, always a better politician than a military strategist, was surprised and defeated by Sam Houston along the banks of the San Jacinto River. The charging Americans yelled “Remember the Alamo!” and sought their revenge. Few prisoners were taken in the melee; perhaps hundreds were executed on the spot. The numbers speak for themselves: 630 dead Mexicans at the cost of two Americans. It is instructive that the Mexican policy of no quarter at the Alamo is regularly derided, yet few north of the Rio Grande remember this later massacre (and probable war crime).

Still, Santa Anna was defeated and forced, under duress (and probably pain of death), to sign away all rights to Texas. The Mexican Congress, as was its constitutional prerogative, summarily dismissed this treaty and would continue its reasonable legal claim on Texas indefinitely. Nonetheless, the divided Mexican government and its exhausted army were in no position (though attempts were made) to recapture the wayward northern province. Texas was “free,” and a thrilled—and no doubt proud—President Jackson recognized Houston’s Republic of Texas on “Old Hickory’s” very last day in office.

Thousands more Americans flowed into the republic over the next decade. By 1845, there were 125,000 (mostly Anglo) inhabitants and 27,000 slaves—that’s more enslaved blacks than Hispanic natives! One result of the war was the expansion and empowerment of the American institution of slavery. Because of confidence in the inevitable spread of slavery, the average sale price of a slave in the bustling New Orleans human-trafficking market rose 21 percent within one year of President John Tyler’s decision to annex Texas (during his final days in office) in 1845. According to international law, Texas remained Mexican. Tyler’s decision alone was tantamount to a declaration of war. Still, for at least a year, the Mexicans showed restraint and unhappily accepted the de facto facts on the ground.

American Blood Upon American Soil?: The Specious Case for War

It took an even greater provocation to kick off a major interstate war between America and Mexico. And that provocation indeed came. In 1844, in one of the more consequential elections in U.S. history, a Jackson loyalist (nicknamed “Young Hickory”) and slaveholder, James K. Polk, defeated the indefatigable Whig candidate Henry Clay. Clay preferred restraint with respect to Texas and Mexico; he wished instead to improve the already vast interior of the existing United States as part of his famed “American System.” Unfortunately for the Mexicans, Clay was defeated, and the fervently expansionist Polk took office in 1845. His election demonstrates the contingency of history; for if Clay had won, war might have been avoided, slavery kept from spreading in the Southwest, and America spared a civil war. It was not to be. Just before Polk took office, a dying Andrew Jackson provided him the sage advice that would spark a bloody war: “Obtain it [Texas] the United States must, peaceably if we can, but forcibly if we must.”

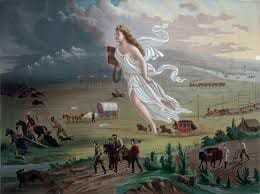

“American Progress,” an 1872 painting by John Gast, shows Manifest Destiny—the belief that the United States should expand from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean—moving westward across the American continent, bringing light as it faces the darkness of unconquered lands.

In the end, it was Polk who would order U.S. troops south of the disputed Texas border and spark a war. Still, the explanation for war was bigger than any one incident. A newspaperman of the time summarized the millenarian scene of fate pulling Americans westward into the lands of Mexicans and Indians. John L. O’Sullivan wrote, “It has become the United States’ manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” There was an American sense of mission, clear from the very founding of Puritan Massachusetts, to multiply and inhabit North America from ocean to ocean. Mexico and the few remaining native territories were all that stood in the way of American destiny by 1846. As the historian Daniel Walker Howe has written, “ ‘Manifest Destiny’ served as both label and a justification for policies that might otherwise simply been called … imperialism.”

Polk was, at least in terms of accomplishing what he set out to do, one of the most successful presidents in U.S. history. He declared that his administration had “four great measures.” Two involved expansion: “the settlement of the Oregon territory with Britain, and the acquisition of California and a large district on the coast.” Within three years he would have both and more. Interestingly, though, Polk wielded different tactics for each acquisition. First, Oregon: Britain and the U.S. had agreed to jointly rule this territory, which at that time reached north to the border with Alaska. Expansionist Democrats who coveted the whole of Oregon ran on the party slogan “54°40′ or Fight!” (a reference to the latitude at the top of the Oregon of that day, a line that marks today’s southern border of the state of Alaska). In the end, however, Polk would not fight Great Britain for Canada. Instead, he compromised, setting the modern boundary between Washington state and British Columbia.

In his dealings with the much less powerful Mexicans, however, Polk took an entirely different, more openly bellicose approach. Here, it seems, he expected if not preferred a war. Was his compromise in Oregon reflective of great-power politics (Britain remained a formidable opponent, especially at sea) or tainted by race and white supremacist notions about the weakness of Hispanic civilization? Historians still argue the point. What we can say is that many Democratic supporters of Polk delighted over the Oregon Compromise, for, as one newspaper declared: “We can now thrash Mexico into decency at our leisure.”

War it would be. In the spring of 1846, President Polk sent Gen. Zachary Taylor and 4,000 troops along the border between Texas and Mexico. Polk claimed all territory north of the Rio Grande River despite the fact that the Mexican province had always established Texas’ border further north at the Nueces River. Polk wanted Taylor to secure the southerly of the two disputed boundaries—probably in contravention of established international law. No one should have been surprised, then, when in April a reconnaissance party of U.S. dragoons was attacked by Mexican soldiers south of the Nueces River. Polk, of course, wily politician that he was, acted absolutely shocked upon hearing the news and immediately began drafting a war message—even though, in fact, his administration had been on the verge of asking Congress for a war declaration anyway! In the exact inverse of his negotiations with Britain over Oregon, Polk had made demands (that Mexico sell California and recognize Texan independence) he knew would probably be rejected by Mexico City, and then sent soldiers where he knew they would probably provoke war. And, oh, how well it worked.

Indeed, Polk’s administration had already set plans in motion for naval and land forces to immediately converge on California and New Mexico when the outbreak of war occurred. Both the U.S. Army and Navy complied and within a year occupied both Mexican provinces. Lest the reader believe the local Hispanics were indifferent to the invasion, homegrown rebellions broke out (and were swiftly suppressed) in both locales. Polk got his war declaration soon after the fight in south Texas. In a blatant obfuscation, Polk announced to the American people that “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory, and shed American blood upon American soil. War exists, and notwithstanding all our efforts to avoid it, exists by the act of Mexico herself.” He knew this to be false.

So did many Whigs in the opposition party, by the way. Still, most obediently voted for war, fearing the hypernationalism of their constituents and remembering the drubbing Federalists had taken for opposing the War of 1812. In cowardly votes of 174-14 in the House (John Quincy Adams, the former president, was one notable dissenting vote) and 40-2 in the Senate, the Congress succumbed to war fever. The small skirmish near the Nueces River was just a casus belli for Polk; America truly went to war to seize, at the very least, all of northern Mexico.

Gen. Winfield Scott and the Defeat of Mexico

On the surface, the two sides in the Mexican-American War were unevenly matched. The U.S. population of 17 million citizens and 3 million slaves dwarfed the 7 million Mexicans (4 million of whom were Indians). Their respective economies were even more lopsided, for America had emerged strong from its market and communications revolutions. Mexico had only recently (1821) gained its independence, and its political situation was fragile and fluctuating. The U.S. had existed independently for some 60 years and already had fought two wars with Britain and countless battles with Indian tribes. America was ready to flex its muscles.

Many observers assumed the war would be easy and short. It was not to be. Most Americans underestimated the courage, resolve and nationalism of Mexican soldiers and civilians alike. That the U.S. won this war—and most of the battles—was due primarily to superiority in artillery, leadership and logistics. The U.S. Military Academy at West Point in New York had trained, and numerous Indian wars had seasoned, a generation of junior and mid-grade officers. Many of the lieutenants and captains who directly led U.S. Army formations in Mexico (one thinks of Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman and James Longstreet, to name only a handful) would serve, either for the North or the South, as general officers in the U.S. Civil War (1861-65). Some of these officers involved in the Mexican-American War relished the glory of exotic conquest; others were horrified by a war they deemed immoral.

It must be remembered that the U.S. Army that entered and conquered Mexico represented a slaveholding republic fighting against an abolitionist nation-state. Many Southern officers brought along slaves and servants on the quest to spread “liberty” to the Mexicans. Some of the enslaved took the opportunity to escape into the interior of a non-slaveholding country. The irony was astounding.

President Polk’s Army was also highly politicized during the conflict. While the existing regular Army officers tended to be Whigs (in favor, as they were, of internal improvements and centralized finance to the benefit of the military), all 13 generals that Polk appointed were avowed partisan Democrats. Polk’s biggest fear—which would indeed come to fruition in the election of Gen. Zachary Taylor as president in 1848—was that a Whiggish hero from the war he began would best his party for the presidency.

When it became clear in 1846 that Gen. Taylor’s initial thrust south into the vast Mexican hinterland could win battles but not the war, Gen. Winfield Scott (a hero of the War of 1812) was ordered to lead an amphibious thrust at the Mexican capital. Indeed, Scott’s militarily brilliant operational campaign constituted the largest American seaborne invasion until D-Day in World War II. It took months of hard fighting and several more months of tenuous occupation, but Scott’s attack effectively ended the war by late 1847.

Still, conducting this war was extremely hard, indeed more difficult than it should have been, on both Taylor and Scott. This was due to President Polk’s decision (reminiscent of George W. Bush’s decision during the Iraq War) to cut taxes and wage war simultaneously. Indeed, Gen. Scott became so short on troops and supplies that he decided to cut off his line of logistics and “live off the land.” This was a clever but risky maneuver that his subordinates—U.S. Grant and William T. Sherman—would remember and mimic in the U.S. Civil War.

There was plenty of room for courage and glory on both sides of the Mexican-American War. It is no accident that the contemporary U.S. Marine Corps Hymn speaks of the “Halls of Montezuma,” or that several grandiose rock carvings of key battle names in Mexico unapologetically adorn my own alma mater at West Point. On the other side, the Mexican people still celebrate the gallant defense, and deaths, of six cadets—known as Los Niños Héroes—who manned the barricades of their own national military academy.

Nevertheless there was (and always is) an uglier, less romantic side of the conflagration. Nine thousand two hundred seven men deserted the U.S. Army in Mexico, or some 8.3 percent of all troops—the highest ever rate in an American conflict and double that of the Vietnam War. Hundreds of Catholic Irish immigrant soldiers responded to Mexican invitations and not only deserted the U.S. Army but joined the Mexican army, as the San Patricio (Saint Patrick’s) Battalion. Dozens were later captured and hanged by their former comrades.

America’s military also waged a violent, brutal war that often failed to spare the innocent. In northern Mexico, Gen. Taylor’s artillery pounded the city of Matamoros, killing hundreds of civilians. Indeed, Taylor’s army of mostly volunteers regularly pillaged villages, murdering Mexican citizens for either retaliation or sport. Many regular Army officers decried the behavior of these volunteers, and one officer wrote, “The majority of the volunteers sent here are a disgrace to the nation; think of one of them shooting a woman while washing on the banks of the river—merely to test his rifle; another tore forcibly from a Mexican woman the rings from her ears.” In the later bombardment of Veracruz, American mortar fire inflicted on the elderly, women or children two-thirds of the 1,000 Mexican casualties. Capt. Robert E. Lee (who would later lead the Confederate Army in the U.S. Civil War) was horrified, commenting that “my heart bled for the inhabitants, it was terrible to think of the women and children.”

It should come as little surprise, then, that when the U.S. Army seized cities, groups of Mexican guerrilla fighters—usually called rancheros—often rose in rebellion. Part of the U.S. effort in Mexico became a counterinsurgency. Take my word for it, people (Iraqis, for example) rarely take kindly to occupation, and the mere presence of foreigners often generates insurgents. All told, the American victory cost the U.S. Army 12,518 lives (seven-eighths of the deaths because of disease, due largely to poor sanitation). Many thousands more Mexican troops and civilians died. This aspect of the war, events that tarnish glorious imagery and language, is rarely remembered, but it would be well if it were.

Courageous Dissent: Whigs, Artists, Soldiers and the Opposition to the Mexican-American War

War, as it does, initially united the country in a spirit of nationalism, but ultimately the war and its spoils would divide the U.S., nearly to its breaking point. Few mainstream Whigs—those of the opposition party—initially demonstrated the courage to dissent. They knew, deep down, that this war was wrong, but also remembered the fate of the Federalist Party, which had been labeled treasonous and soon disappeared due to its opposition to the War of 1812. Other Whigs were simply dedicated nationalists: The U.S. was their country, right or wrong. But there were courageous voices, a few dissenters in the wilderness. Some you know; others are anonymous, lost to history. All were patriots.

Many were politicians: those entrusted with the duty to dissent in times of national error. Though only a dozen or so Whigs had the fortitude to vote against the war declaration in 1846, a few were vocal. One was Rep. Luther Severance, who responded to President Polk’s “American blood on American soil” fallacy by exclaiming that “[i]t is on Mexican soil that blood has been shed” and Mexicans “should be honored and applauded” for their “manly resistance.”

Another was former President John Quincy Adams, who at the time was a member of the U.S. House from Massachusetts (he was the only person to serve in Congress after being president). It was Adams, we must remember, who as secretary of state in 1821, had presciently warned Americans against foreign military adventures. “But she [America] goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy,” he wrote, for “[Were she to do so] the fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force … she might become the dictatress of the world.” Adams had seen the Mexican War coming back in 1836, when his avowed opponent President Andrew Jackson considered annexation of the Texan Republic. Then, Adams had said, “Are you not large and unwieldy enough already? Have you not Indians enough to expel from the land of their fathers’ sepulchre?”

Another staunch opponent of the war was a little known freshman Whig congressman from Illinois, a lanky fellow named Abraham Lincoln. As soon as he took his seat in the House, Lincoln immediately rebuked President Polk’s initial explanation for declaring war. “The President, in his first war message of May 1846,” Lincoln told his audience, “declares that the soil was ours on which hostilities were commenced by Mexico; Now I propose to try to show, that the whole of this–issue and evidence–is, from beginning to end, the sheerest deception.” The future president would later summarize the conflict as “a war of conquest fought to catch votes.” And, indeed it was.

Prominent artists and writers also opposed the war; such people often do, and we should take notice of them. The Transcendentalist writers Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson each took up the pen to attack the still quite popular conquest of Mexico. Thoreau, who served prison time, turned a lecture into an essay now known as “Civil Disobedience.” Emerson was even more succinct, declaring, “The United States will conquer Mexico, but it will be as a man who swallowed the arsenic which brings him down in turn. Mexico will poison us.” He couldn’t have known how right he was; arguments over the expansion of slavery in the lands seized from Mexico would indeed take the nation to the brink of civil war in just a dozen years.

One expects dissent from artists. These men and women tend to be unflinching and to demonstrate a willingness to stand against the grain, against even the populist passions of an inflamed citizenry. But … soldiers? Surely they must remain loyal and steadfast to the end, and so, too often, they are. Not so in Mexico. A surprising number of young officers—like Lee at the bombardment of Veracruz—despised the war. More than a few likely suffered from what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). One lieutenant colonel, Ethan Hitchcock, even attacked the justification for war. He wrote, “We have not one particle of right to be here. It looks as if the [U.S.] government sent a small force on purpose to bring on a war, so as to have the pretext for taking California and as much of this country as it chooses.” Perhaps the most honest and self-effacing critique of the war came from a young subaltern named U.S. Grant (who along with his then-comrade R.E. Lee would later lead one of the two opposing armies in the Civil War). Grant, a future president and West Point graduate, wrote that he “had a horror of the Mexican War … only I had not the moral courage enough to resign.”

Finally, let us return to the powerful and unwavering dissent of John Quincy Adams, for the Mexican War, not his presidency, may constitute his finest hour. On Feb. 21, 1848, the speaker of the House called for a routine vote to bestow medals and adulation on the victorious generals of the late Mexican War. The measure passed, of course, but when the “nays” were up for roll call a voice from the back bellowed “No!” It was the 80-year-old former president. Adams then rose in an apparent effort to speak, but his face reddened and he collapsed. Carried to a couch, he slipped into unconsciousness and died two days later. John Quincy Adams was mortally stricken in the act of officially opposing an unjust war. That we remember the victories of the Mexican-American War but not Adams’ dying gesture surely must reflect poorly on us and our collective remembrances.

A Long Shadow Cast: The ‘Peace’ of 1848

From the war’s start, there was never any real question of leaving Mexico without extracting territory. Indeed, by late 1847 there was considerable Democratic support for taking the whole country. That the U.S. did not is due mainly to Polk’s peace commissioner ignoring orders and his own firing to negotiate a compromise. But there was something else. Many Democrats from the South—who had applauded the war from the start—now flinched before the prospect of taking on the entirety of Mexico and its decidedly brown and Catholic population. There was inherent fear of racial mixing, racial impurity and heterogeneity. John Calhoun, the political stalwart from South Carolina, even declared, “Ours is the government of the white man!” And, in 1848, Calhoun was right, indeed.

Even the Wilmot Proviso, an attempt by a Northern congressman to forestall any conquest in Mexico, was tinged with racism. Rep. David Wilmot called his amendment a “White Man’s Proviso,” to “preserve for free white labor a fair country, a rich inheritance, where the sons of toil, of my own race and own color, can live without the disgrace which association with Negro slavery brings upon free labor.” Wilmot’s proposal, unsurprisingly, never passed muster. But it nearly tore the Congress asunder, with Northern and Southern politicians at each other’s throats. Northerners generally feared the expansion of slave states and of what they called “slave power.” The Whig Party itself nearly divided—and eventually would—into its Northern and Southern factions. As we will see, arguments about what land to seize from Mexico and what to do with it (should it be slave or free?) would shatter the Second Party System—of Whigs and Democrats—and take the nation one step closer to the civil war many (like John Quincy Adams) had long feared. The “peace” of 1848, known to history as the Treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo, would certainly cast a long shadow.

* * *

In the end, the U.S. expended over 12,000 lives and millions of dollars to make a new colony of nearly half of Mexico—an area two and a half times the size of France and including parts or all of the current states of California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona. Much of the land remained heavily Hispanic for decades and effectively under military government for many years (New Mexico until 1912!). The real losers were the Indian and Hispanic people of the new American Southwest. The U.S. gained 100,000 Spanish-speaking inhabitants after the treaty and even more native Americans. Under Mexican law, both groups were considered full citizens! Under American stewardship, race was a far more detrimental factor. The results were (despite supposed protections in the treaty) the seizure of millions of acres of Hispanic-owned land and, in California, Indian slavery and decimation as 150,000 natives dwindled to less than 50,000 in just 10 years of U.S. control. During the postwar period, California’s governor literally called for the “extermination” of the state’s Indians. This aspect of the war’s end is almost never mentioned at all.

Words matter, and we must watch our use of terms and language. Mexico hadn’t invaded Texas; Texas was Mexico. Polk manufactured a war to expand slavery westward and increase pro-slavery political power in the Senate. Was, then, America an empire in 1848? Is it today? And why does the very term “empire” make us so uncomfortable?

So what, then, are readers to make of this mostly forgotten war? Perhaps this much: It was as unnecessary as it was unjust. Nearly all Democrats supported it, and most Whigs simply acquiesced. Others, however, knew the war to be wrong and said so at the time. Through an ethical lens, the real heroes of the Mexican-American War weren’t Gens. Taylor and Scott, but rather artists such as Henry David Thoreau; a former president, John Quincy Adams; and Abraham Lincoln, then an obscure young Illinois politician. There are many kinds of courage, and the physical sort shouldn’t necessarily predominate. In this view, the moral view, protest is patriotic.

So, let me challenge you to think on this: Our democracy was undoubtedly achieved through undemocratic means—through conquest and colonization. Mexicans were just some of the victims, and, today, in the American Southwest, tens of millions of U.S. citizens reside, in point of fact, upon occupied territory.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

• Rodolfo Acuna, “Occupied Mexico: A History of Chicanos” (1988).

• James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 14. “Western Expansion and the Rise of the Slavery Issue, 1820-1850” (2011).

• Daniel Walker Howe, “What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-48” (2007).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Judge Upholds HUD’s Delay of Anti-Segregation Housing Rule

WASHINGTON—A federal judge has upheld a decision by the Department of Housing and Urban Development to delay an Obama-era anti-discrimination rule.

Chief Judge Beryl A. Howell of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on Friday threw out a lawsuit filed by a group of civil rights organizations challenging HUD’s delay of the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule.

Finalized in 2015, the rule for the first time required more than 1,200 jurisdictions receiving HUD block grants and housing aid to analyze housing stock and come up with a plan for addressing patterns of segregation and discrimination. If HUD determined that the plan, called a Fair Housing Assessment, wasn’t sufficient, the city or county would have to rework it or risk losing funding.

HUD said in January that it would immediately stop reviewing plans that had been submitted but not yet accepted, and jurisdictions won’t have to comply with the rule until after 2020. The agency said the postponement was in response to complaints from communities that had struggled to complete assessments and produce plans meeting HUD’s standards; of the 49 submissions HUD received in 2017, roughly a third were sent back. In delaying the rule, HUD reverted to its previous process for evaluating discrimination in housing.

“What we heard convinced us that the Assessment of Fair Housing tool for local governments wasn’t working well,” HUD said in the statement. “In fact, more than a third of our early submitters failed to produce an acceptable assessment — not for lack of trying but because the tool designed to help them to succeed wasn’t helpful.”

Civil rights organizations including National Fair Housing Alliance, Texas Appleseed and Texas Low Income Housing Information Service sued HUD and Secretary Ben Carson earlier this year. The suit argued that Carson didn’t follow the procedures necessary to suspend such a rule, and that the delay violates the Fair Housing Act, which requires jurisdictions to take active steps to combat segregation.

Howell rejected the groups’ request for a preliminary injunction and blocked the state of New York from joining suit. She wrote in her order the delay of the AFFH rule hasn’t caused harm to the groups or impeded their ability to do their jobs.

Howell wrote that because “portions of the rule are still in effect, such as the new definitions of furthering fair housing and community engagement requirements,” the fact that other pieces of the rule, such as the assessment tool “are presently dormant does not translate to the dismantling and suspension of the AFFH Rule in a way that affects the plaintiffs’ mission-driven activities.”

“The extent to which the challenged HUD notices directly conflict or perceptibly impede the plaintiffs’ mission-oriented activities seems difficult to measure, or, in other words, are imperceptible,” she wrote.

“We are deeply disappointed that the court did not recognize the importance of immediately and fully reinstating the mechanisms needed to implement the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Rule,” the National Fair Housing Alliance said in a statement.

Last week HUD proposed changes to the rule and solicited public comments on possible amendments.

Inmates in 17 States Plan Prison Strike

Incarcerated Americans in at least 17 states will go on strike this coming week, refusing to perform labor and engaging in sit-ins and hunger strikes to demand major reforms to the country’s prison and criminal justice systems.

The Nationwide Prison Strike is planned for August 21, the day Nat Turner led an uprising of slaves in 1831, until September 9, the 47th anniversary of the Attica prison rebellion in which more than 40 people were killed.

Organizers of the action, which is endorsed by Jailhouse Lawyers Speak and the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC), have released a list of ten demands for improvements to their living conditions, sentencing policies, and laws that allow for prison slavery.

PRESS RELEASE:

NATIONAL PRISON STRIKE AUGUST 21-SEPTEMBER 9TH, 2018 pic.twitter.com/Mzbb4e96yp

— Jailhouse Lawyers Speak #August21 (@JailLawSpeak) April 24, 2018

“All persons imprisoned in any place of detention under United States jurisdiction must be paid the prevailing wage in their state or territory for their labor,” reads the list of demands. The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution allows for “slavery or involuntary servitude…as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

Organizers are also calling for “access to rehabilitation programs” for incarcerated people and an end to “Death by Incarceration,” or life sentences without the possibility of parole.

A spokesperson for the strike called on Americans to support the protest, noting that inmates produce many of the products people use every day in the outside world—including Starbucks packaging, state license plates, and furniture.

“Prisoners want to be valued as contributors to our society. Every single field and industry is affected on some level by prisons, from our license plates to the fast food that we eat to the stores that we shop at,” Amani Sawari told Vox. “So we really need to recognize how we are supporting the prison industrial complex through the dollars that we spend.”

Prisoners have also fought the wildfires raging in California and those that tore through parts of the state last year, earning a stipend of $2 per day plus $1 per hour, and sometimes working 72-hour shifts in order to save the state up to $100 million per year.

The strike comes four months after the deaths of seven inmates in a riot at Lee Correctional Institution in Bishopville, South Carolina. According to one witness who spoke to the Associated Press, prison employees did not attend to injured and dying inmates or attempt to stop the violence.

Organizers are calling on supporters to “Amplify incarcerated voices via social media using the #August21 and #prisonstrike hashtags,” and to contact their election officials to advocate for the inmates’ demands.

Demonstrations in solidarity with the inmates are planned outside prisons in Brooklyn, New York; San Quentin, California; and Bishopville as well as other cities.

A number of Democratic Socialists of America chapters have voiced their support for the strike in recent days.

North Jersey DSA supports and proudly endorses the nationwide prison strike set to begin August 21- September 9th. Prison labor is slavery and we demand its abolition.

Burn Down The American Plantation! #August21 https://t.co/ZUJITFJflw

— North Jersey DSA

Will Trump Be Charged With Conspiracy to Violate Federal Election Law?

In addition to the case for Donald Trump’s obstruction of justice by firing former FBI Director James Comey, evidence is mounting that the president participated in a conspiracy to violate the federal election law. Special Counsel Robert Mueller could either ask a grand jury to indict Trump as a co-conspirator or to name the president as an unindicted co-conspirator.

Federal Election Law

Trump’s August 5 tweet that the purpose of the June 9, 2016, Trump Tower meeting between Donald Trump Jr., Jared Kushner, Paul Manafort and Russian operative Natalia Veselnitskaya “was to get information on an opponent” was tantamount to an admission of a conspiracy to violate federal election law.

Although the president added it was “totally legal and done all the time in politics,” he was mistaken about the “totally legal” part.

The federal election law says it is unlawful for “a foreign national, directly or indirectly, to make a contribution or donation of money or other thing of value … in connection with a Federal, State, or local election.” Providing the Trump campaign with dirt on Hillary Clinton to discredit her in the election constitutes a “thing of value.” It is also illegal for “a person to solicit, accept, or receive a contribution or donation … from a foreign national.”

Conspiracy Law

Another federal law makes it a crime for two or more persons to conspire to commit an offense or defraud the United States. The defraud clause criminalizes “any conspiracy for the purpose of impairing, obstructing or defeating the lawful function of any department of government.”

Trump also tweeted that “it went nowhere.” But there is legal liability for conspiracy even if the purpose of the conspiracy is not accomplished.

A conspiracy is complete upon an agreement by two or more people to commit a crime followed by at least one overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy, even if that crime is never committed. The overt act need not be unlawful in itself.

Six days before the Trump Tower meeting, British tabloid reporter Rob Goldstone emailed Donald Trump Jr. that the Russian government had “some official documents and information that would incriminate Hillary,” adding, “This is obviously very high level and sensitive information but is part of Russia and its government’s support for Mr. Trump.” Seconds later, Trump Jr. replied, “if it’s what you say I love it.”

Conspiracy to Violate the Federal Election Law

Trump Jr. arranged the meeting with the expectation of receiving negative information the Russian government purportedly had about Clinton. That constituted an agreement between Goldstone and Trump Jr. to violate the federal election law.

Arranging the meeting and attending the meeting were both overt acts. Everyone who attended the meeting with knowledge of its purpose and the intent to further that purpose is liable for conspiracy to violate the federal election law.

All co-conspirators are legally responsible for the acts of the other co-conspirators, even if they didn’t directly participate in those acts or are unaware of the details of the conspiracy. Trump need not have attended the June 9 meeting to be liable as a co-conspirator.

Trump ended his August 5 tweet about the Trump Tower meeting by saying, “I did not know about it!”

There is evidence that Trump did know about the meeting. Trump’s former lawyer, Michael Cohen, claims the president was in the room, learned about the Russian offer, and approved the June 9 meeting. And Rudy Giuliani, Trump’s current lawyer, let slip that a meeting between Trump, Trump Jr., Paul Manafort, Jared Kushner and Manafort’s top deputy Rick Gates took place on June 7.

On the evening of June 7, Trump announced that he would “give a major speech” during the following week to reveal “the things that have taken place with the Clintons.” Trump never delivered that speech.

If Trump approved the June 9 meeting, that approval constitutes another overt act.

Even if Trump didn’t know of the June 9 meeting beforehand, he participated in a conspiracy to cover it up by later dictating a false statement about the purpose of that meeting.

In the memo he drafted, Trump said the people present at the Trump Tower meeting “primarily discussed a program about the adoption of Russian children” and the topic of the meeting was “not a campaign issue at the time.”

Can a Sitting President Be Indicted?

Whether or not a president can be criminally indicted during his time in office is a matter of controversy.

The Office of Legal Counsel at the Department of Justice during both the Nixon and Clinton administrations took the position that sitting presidents are immune from prosecution.

But a memo from independent counsel Kenneth Starr’s investigation of Clinton says a president can be indicted for criminal activity: “It is proper, constitutional, and legal for a federal grand jury to indict a sitting president for serious criminal acts that are not part of, and are contrary to, the president’s official duties. In this country, no one, even President Clinton, is above the law.”

Some legal scholars argue that the Constitution provides the remedy of impeachment for a law-breaking president, who can only be charged with a crime after he leaves office.

But Hofstra University law professor Eric Freedman wrote a 1999 law review article explaining why a sitting president could be indicted. He noted that other federal officials, such as judges, who are subject to impeachment, have been indicted during their tenure in office.

Jonathan Turley, a George Washington University law professor writing in The Washington Post, concluded that a sitting president can be charged with a crime. “An indicted president is a terrible proposition,” Turley wrote. “But so is the continuation of a presumed felon in office — one who clings to power as a shield from accountability.”

Giuliani told “Fox & Friends” that Mueller’s office informed Trump attorney Jay Sekulow that the special counsel did not have the power to indict a sitting president.

Mueller has made no public pronouncement about the propriety of indicting Trump while in office. The special counsel is required to send a confidential report to Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, who appointed Mueller after Jeff Sessions recused himself from the Russia investigation. Even if Mueller does not think he can indict Trump, Rosenstein could override that decision.

The Supreme Court has not ruled on whether a sitting president can be criminally indicted. But in 1997, the high court held in Clinton v. Jones that a president could be the subject of a civil lawsuit while in office.

Trump Could Be Named as an Unindicted Co-Conspirator

If Mueller does not ask a grand jury to indict Trump, he could request that they name the president as an unindicted co-conspirator if the special counsel files an indictment against others, such as Trump Jr., Kushner and Manafort.

There is precedent for this course of action. In 1974, a grand jury indicted seven associates of President Richard Nixon for the cover-up of the Watergate burglary. At the request of special prosecutor Leon Jaworski, as an unindicted co-conspirator.

Ultimately, if Trump can’t be indicted, he may not be able to refuse a subpoena to testify before a grand jury by claiming the privilege against self-incrimination. He could not incriminate himself due to his alleged immunity from prosecution. But he could take the Fifth while still in office if he faces post-presidency indictment.

Copyright Truthout. Reprinted with permission.

Mueller Asks Prison Time for Trump Ex-Aide George Papadopoulos

WASHINGTON—A former Trump campaign adviser should spend at least some time in prison for lying to the FBI during the Russia probe, prosecutors working for special counsel Robert Mueller said in a court filing Friday that also revealed several new details about the early days of the investigation.

The prosecutors said that George Papadopoulos, who served as a foreign policy adviser to President Donald Trump’s campaign during the 2016 presidential race, caused irreparable damage to the investigation because he lied repeatedly during a January 2017 interview.

Those lies, they said, resulted in the FBI missing an opportunity to properly question a professor Papadopoulos was in contact with during the campaign who told him that the Russians possessed “dirt” on Hillary Clinton in the form of emails.

The filing by the special counsel’s office strongly suggests the FBI had contact with Professor Joseph Mifsud while he was in the U.S. during the early part of the investigation into Russian election interference and possible coordination with Trump associates.

According to prosecutors, the FBI “located” the professor in Washington about two weeks after Papadopoulos’ interview and Papadopoulos’ lies “substantially hindered investigators’ ability to effectively question” him. But it doesn’t specifically relate any details of an interview with the professor as it recounts what prosecutors say was a missed opportunity caused by Papadopoulos.

“The defendant’s lies undermined investigators’ ability to challenge the Professor or potentially detain or arrest him while he was still in the United States,” Mueller’s team wrote, noting that the professor left the U.S. in February 2017 and has not returned since.

Prosecutors note that investigators also missed an opportunity to interview others about the professor’s comments or anyone else at that time who might have known about Russian efforts to obtain derogatory information on Clinton during the campaign.

“Had the defendant told the FBI the truth when he was interviewed in January 2017, the FBI could have quickly taken numerous investigative steps to help determine, for example, how and where the Professor obtained the information, why the Professor provided the information to the defendant, and what the defendant did with the information after receiving it,” according to the court filing.

Prosecutors also detail a series of difficult interviews with Papadopoulos after he was arrested in July 2017, saying he didn’t provide “substantial assistance” to the investigation. Papadopoulos later pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI as part of a plea deal.

The filing recommends that Papadopoulos spend at least some time incarcerated and pay a nearly $10,000 fine. His recommended sentence under federal guidelines is zero to six months, but prosecutors note another defendant in the case spent 30 days in jail for lying to the FBI.

Papadopoulos has played a central role in the Russia investigation since its beginning as an FBI counterintelligence probe in July 2016. In fact, information the U.S. government received about Papadopoulos was what triggered the counterintelligence investigation in the first place. That probe was later take over by Mueller.

Papadopoulos was also the first Trump campaign adviser to plead guilty in Mueller’s investigation.

Since then, Mueller has returned two sweeping indictments that detail a multi-faceted Russian campaign to undermine the U.S. presidential election in an attempt to hurt Clinton’s candidacy and help Trump.

Thirteen Russian nationals and three companies are charged with participating in a conspiracy to sow discord in the U.S. political system primarily by manipulating social media platforms.

In addition, Mueller brought an indictment last month against 12 Russian intelligence operatives, accusing them of hacking into the computer systems of Clinton’s presidential campaign and the Democratic Party and then releasing tens of thousands of private emails through WikiLeaks.