Chris Hedges's Blog, page 447

October 10, 2018

Here’s How to Make Sure Your Vote Is Properly Counted

Editor’s Note: The 2018 midterm elections are quickly approaching. These non-presidential elections historically give voters a chance to change the country’s course. They will decide whether or not Republicans keep a majority in Congress, as well as determine important governor’s races and more.

A Voter’s Guide to the 2018 Election, written by Steven Rosenfeld, senior writing fellow of Voting Booth, is intended to help new voters, infrequent voters and veteran voters have a better idea of what they must do to be able to vote and have their vote counted. The following is an excerpt from the guide, available in full here.

Polling Place Issues

Sometimes voting is a breeze. You show up, sign in and vote, and that’s it. Other times it’s slow, delayed, confusing and chaotic. Either way, patience and some knowledge of the process is key.

People who vote in polling places and local precincts have a different experience than people who vote by mail (or vote early at county offices). In general, the biggest concerns for voting by mail is having the ballot envelope properly filled out and postmarked.

Voting at polling places is another story. Across America’s 6,467 election jurisdictions and 168,000 voting precincts, the experiences can really vary. There can be heckling by partisans on the street outside—or not. There can be lines and delays to check-in—or not. There can be informed poll workers (citizens nominally paid to run the process) at sign-in tables, or inside as precinct judges—or not. There can be voting machines that work—or not. There can be sufficient backup ballots and knowledgeable officials—or not.

Related Articles

A Red State Victory for Voting Rights

by

Whether you are in a more functional or less functional polling place, the voting process is the same. So let’s go through it, especially for new voters. It starts with knowing when Election Day is. (That sounds obvious, but partisan disruptors have been known to tell people that their party votes on Tuesday—when Election Day is—and other parties vote on Wednesday.) This leads to a related point. You don’t have to stop or talk to anybody on the way into a polling place or while waiting in line. Political campaigns are legally required to keep a certain distance from the entrance.

Poll Location and Check-In

But let’s back up. You registered. That means you might receive, by mail, a voter guide with a sample ballot, which often includes statements from candidates, and pro and con positions on the non-candidate issues. That mailing also has one’s polling place location. Some states may only mail a postcard with the poll location. Voters who do not get this information should call their local election office. There are many polling place locator apps online, but it’s best to check directly with your local election officials.

On Election Day, give yourself enough time. (If you are going to be pressed, think about voting early if your state allows that.) When you get to your polling place, you have to check in. This is where you show your ID, if that’s required, or sign your name in a poll book, or sometimes both, and get a regular ballot. Then, you go inside, find a booth to privately mark a paper ballot or use a touch-screen computer, and turn in that ballot (in the folder given to you). Poll workers put the paper ballots into a scanner. You get an “I voted” sticker and you’re done. Voters with disabilities use special consoles.

What can go wrong? Well, every step of this process—for reasons that can range from simple human error, to poor planning by election officials, to bungling poll workers, to machines that malfunction, to rare but still real partisan power plays. In all of these cases, patience and perseverance are the key to casting a vote that will be counted.

Let’s start with long lines. Why would there be long lines? Maybe it’s a certain time of day and people are just showing up all at once. Maybe there are too many questions on the ballot and too few machines or voting booths, causing a voting traffic jam. No matter what, you have to be patient. Anyone in line will be allowed to vote, even if it’s past the official closing time. Check the weather. If it’s cold or wet, take a jacket and an umbrella.

Sometimes, long lines result from election officials making mistaken voter turnout estimates, as that translates into how many voting machines/booths are deployed. There is some chance that scenario will happen this fall, because midterm years usually are the lowest-turnout November elections. That’s mostly been true even in 2018, where there has been greater turnout by Democrats and less turnout by Republicans.

The Backup: Provisional Ballots

Once you’re inside, you have to check in to get a ballot. What happens if you know you have properly registered, but your name and street address are not in the precinct poll book? First, take a deep breath, and know there’s a process to fix this.

The first thing to check is if you’re in the correct polling place and precinct. (Many polls have multiple precincts.) If you are in the right location, but not in the poll book, you can re-register in states offering Election Day registration (see this list) and then get a ballot. If you’re not in one of those states, you will be given what is called a provisional ballot. (In 27 states, partisan “poll watchers” also can challenge a voter’s credentials, triggering a provisional ballot. That’s very rare, but we’ll get to what to do if it happens in a second.)

What is a provisional ballot? They are ballots combined with a partial voter registration form. A 2002 federal law requires every state to offer backup provisional ballots. A voter fills in some different identifying information (address, birthday, etc.—states vary here), so officials can verify your registration before counting your ballot. The most common reasons for issuing a provisional ballot are: voters showing up at the wrong precinct and demanding to vote; people who don’t have the required state ID; people not listed on a precinct voter roll; and people claiming they never got an absentee ballot in the mail. Provisional ballots also have been used as backup if electronic voting machines fail.

People filing provisional ballots have to make sure they are turned in at the right desk—for their precinct. In half the states, turning in a provisional ballot at the wrong precincts means it won’t be counted. This scenario has been called the “right church, wrong pew” problem: You’re in the right polling place but can’t turn it in at any table. The solution is asking the poll workers—and checking that they’re properly signed and turned in.

Most states make an effort to verify and count all of their provisional ballots. But that is not always true—because some states, like Georgia, will not count them if officials have not verified all of the voter’s registration information in three days following Election Day. In other states, like Illinois, voters might have to show up at election offices with additional identifying documentation within a week of Election Day for the ballots to count. Lots of people never make that trip.

Still, provisional ballots are the backup system in all 50 states. So if something goes wrong, despite being proactive with registering and having the right ID with you, fill them out carefully and turn them in. Chances are they will be counted more than not.

If, for some reason, a voter is having a problem with harassment while waiting in line, the precinct check-in process, or getting answers about provisional ballots, there are Election Day hotlines to call lawyers volunteering for a nationwide Election Protection project run by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. That toll-free number is 1-866-OUR-VOTE (687-8683).

Election protection lawyers will tell you exactly what to do, and if necessary, are ready to go into court on your behalf. They will also alert the media about egregious problems, from harassment of voters to undue partisan challenges to any real breakdown in the process.

(In 2018, they are aware a federal court order that for the past 30 years has restricted the Republican National Committee from unduly challenging voters under a “ballot security” pretext—saying people signing in at polls must present additional credentials [usually more ID]—may be repealed. If that happens to you—call them. They will be on it.)

Voting Machine Issues

Once signed in, voters get a paper ballot in a folder and are directed to private booths to fill it out, or they go to electronic voting machines where they touch the screen to make their selections.

Voting machine technology is a controversial topic. But recently there’s more good news than bad with the voting machines used across America. Three-quarters of the country now votes on ink-marked paper ballots, and that figure is growing. Paper ballots are the best way to ensure there is a record of every vote cast. Scanners count these ballots, which can be further examined in recounts and audits. (The newest scanners even compile digital images of all the marked ovals race by race, which have helped to transparently resolve who has won very close contests.)

The bad news surrounds the oldest paperless voting systems, which still are used in 13 states—and entirely across five states (Louisiana, Georgia, South Carolina, New Jersey, Delaware). The biggest problems with paperless technology are that there is no backup in case the computer memory fails, and the vote counting software is susceptible to hacking, which has been shown to be a possibility in academic settings. (See this chart of voting technology by state and county.)

What does this mean for voters now? It’s counterintuitive, but the visible breakdowns on paperless machines are well known by now, as are their causes and fixes. For example, a decade ago, it was not uncommon for touch-screen users to select one candidate but see another candidate’s name appear. However frustrating it may be, the issues that have bothered activists and academics the most—hacking the results—are concerns voters cannot do anything about while they are using these machines on Election Day.

If you are voting on a touch-screen system and experience a problem, what do you do? You pause, ask poll workers for help, and either use another machine or insist on using a paper ballot backup. That sounds frustrating. Yet there is only so much a voter can do in that moment. You don’t have to be shy here. Voters make mistakes marking ballots all the time. Poll workers give them fresh ballots. They have a process for spoiled ballots. The pragmatic answer here is to speak up if something isn’t right with a machine.

With few exceptions in 2018, electronic voting machine breakdowns are not likely to be a major issue for most voters this fall. That conclusion even extends to the one threat that no voter can do anything about—the prospect of intentionally altered or hacked results. Why? Because since April, most states and the federal government have undertaken unprecedented cyber-security precautions surrounding the computers used in voting. Congress appropriated $380 million to secure these systems from Russian hacking. Ironically, it took a foreign power for election officials to take hacking seriously.

The Long View

The voting process has requirements, steps to be followed, potential bottlenecks and procedural hurdles, and backups if things go wrong. Those complexities raise larger questions, starting with, “Can voters trust this process?”

The answer is yes. We have to. We have no choice. Also, across America, most of the people running the nuts and bolts of elections are career civil servants dedicated to voting. They are not cut from the same cloth as politicians and political appointees who see elections as the pliable path to obtaining power. While there is some overlap, civil servants, as a profession and culture, believe in participatory democracy.

Despite the process’ pluses and minuses, voting is how citizens change or sustain our political system’s leaders. If the stakes in voting weren’t high, or if voting didn’t have an impact, you wouldn’t find all these political efforts in some states to make the process harder for the opposing party’s base.

As we look toward 2018’s midterms, the good news is that voting has become easier and more trustable in most of the country. That reality can be seen in more options to register, more ways to vote and wider use of paper ballots. In other parts of the U.S. where voting is more arduous, voters are not without help. When it comes to getting voter ID in states with stricter laws, non-profit groups are poised to help people. If there are Election Day instances of harassment or obstruction, civil rights lawyers can be easily and quickly reached. There are also fail-safe systems, especially provisional ballots, which, when properly filled out, will be validated and counted in most states using them.

To read the complete text of “A Voter’s Guide to the 2018 Election,” click here to view online, or click here view/download the full guide as a pdf.

The Shameless Opportunism of Nikki Haley

In the Coen brothers’ acerbic spy-thriller send-up, “Burn After Reading,” George Clooney, playing an unfaithful, fitness-obsessed blockhead, disabuses his lover, a vicious Tilda Swinton, that her CIA analyst husband has quit his job to pursue “a higher patriotism.” “Yeah,” he tells her, “well, most of the people in this town who quit were fired.”

It is a truism wrapped in a falsehood. John Malkovich’s Princetonian analyst, the perfectly named Osborne Cox, did in fact quit, but only because he was about to be fired, or at least severely demoted.

Widely considered a minor Coen feature, “Burn After Reading” received mostly lukewarm reviews in that hopey-changey year of 2008 for its bleak, even misanthropic tone. One dissenting voice has been The New Republic’s Jeet Heer, who judged the film an extraordinarily prescient take on the future Trump Era and a small masterpiece.

More than just a satire on espionage, the movie is a scathing critique of modern America as a superficial, post-political society where cheating of all sorts comes all too easily. Unlike movies such as Citizen Kane, Burn After Reading doesn’t offer any easy one-to-one character analogies to Trump and his cronies. Rather, it captures the amorality that leads people to become entangled in mercenary treason.

And so we come to Nikki Haley, our soon-to-be ex-U.N. ambassador, who, as of this weird, warm week in October, was either fired or quit.

The poor New York Times Editorial Board—a collection of self-important, moron-despising Osborne Coxes if ever there was one—seemed close to tears. “Indeed,” it bleated, “a replacement in her mold may be the best to hope for from Mr. Trump.” Operating on the scant evidence that Haley once sententiously proclaimed, “I don’t get confused,” after some daily—hell, hourly—confusion of the administration for which she worked and the anecdotal and frankly unbelievable tale that she “developed a good relationship” with the U.N. secretary-general, the Editorial Board clutches at a last brick of normalcy in the wreckage of its antiquated worldview.

Why did she go? After six years as governor of South Carolina and two as ambassador, Haley said she simply needed time off. It is certainly an odd feature of Washington that some people can go years—and even decades—evincing no particular dedication to family, then suddenly acquire a yearning to spend more time with theirs, whereas others—a Chuck Grassley, who managed to be both somnolent and indefatigable in “plowing” through the Supreme Court nomination of an alleged sex abuser—can spend 60 years in official life without the slightest indication that they ever intend to retire.

Of course, it is far more stressful, busy and taxing to be a governor, even of a small state, than to be a U.S. senator, a member of a body that exists in a condition of collective torpor bordering on catatonia, a towering retirement community without the charm of bingo or the stimulating activity of bus trips to the local symphony.

Ordinarily, a U.N. ambassador falls far to the Senate side of active life. One need only show up to make the occasionally requisite bellicose speech, to harangue some little country for doing what the United States of America does a hundred times a week. But Trump’s foreign policy team, especially Rex Tillerson, his first secretary of state, made the aquatic pace of Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson look positively rocket-like. It does seem clear that Haley functioned as something closer to a shadow secretary and national security adviser, at least until Mike Pompeo maneuvered his way into Tillerson’s spot and John Bolton waddled back ashore from the spume of a frigid sea.

Haley did not actually do much in her tenure. The Trump administration has been remarkably successful at the Washington nomination game and at dismantling the American regulatory state where its only opposition is the Democrats, but the world has proven less feckless. The U.S. military has continued to bomb where it would have under a Clinton presidency—where it had been bombing under Obama—but the great deal-maker president has mostly gotten fleeced. He was outmaneuvered by North Korea. China defies him. The renegotiated NAFTA treaty may not survive a new president in Mexico or federal elections in Canada.

Across the Atlantic, Europe is slowly pulling away, despite its exposure to U.S. financial markets and France’s Trump-manqué Emmanuel Macron making grandiose declarations about internationalism any time he notices a microphone in his vicinity. Even the Iran deal, which Haley condemned and Trump tore up, has really just returned to the status quo ante: not ideal, certainly, not good, but something. The best chronicler of this chronic bombast combined with stagnant policy has probably been Daniel Larison, the conservative Trump critic at The American Conservative, who took Haley particularly to task for her ceaselessly aggressive rhetoric.

The Trump administration did manage to move the U.S. Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, or at least announce that it was going to do so, although like so much else with this administration it is hard to tell if there is any real “doing” behind the announcing. It cruelly and unnecessarily announced it would block any Palestinian from a senior U.N. post, and apologized ceaselessly for Israel’s reckless violence in Gaza. But even this—a sop to the evangelical base—evaporated into the endless hot air of Trump-world.

Hard-line support for Israel has been Haley’s one consistent foreign policy position during her political career. Beyond that, it is hard to know precisely what she believes, if she believes anything at all. Her conservatism in South Carolina seemed moderate, at least by our increasingly bonkers standards. She did not support gay marriage, but neither did she endorse a South Carolinian “bathroom bill.” She was broadly pro-business, but she also removed the Confederate flag from the state Capitol in the wake of the Dylann Roof shooting in Charleston.

Why she felt so strongly about Israel is anyone’s guess—mine, admittedly, is that it began as pure political calculation, a not-so-subtle signal to the conservative Christian electorate in her state that she, a woman of Sikh heritage who still practices the faith, along with Christianity, was reliably one of them. It’s a remarkable feature of our American Christianity that regular churchgoing is lesser proof of faith than an ostentatious love of the Jewish state.

In another telling coincidence, her own original gubernatorial candidacy was saved by the intervention of that marvelous proto-Trump, Sarah Palin, who swept in to endorse Haley when she was running last in a contested primary. Then, several years later, when Trump appeared as a presidential contender, Haley began as a critic, calling for him to release his taxes and drawing his ire on Twitter, to which she famously responded, “bless his heart.” That was taken as a sign of authenticity and gumption, but in reality she was no less an opportunist than any of the rest of them, ping-ponging from Rubio supporter to Cruz partisan as they appeared to mount creditable challenges to the Trump phenomenon before signing on with Trump when the inevitable, inevitably occurred.

It is rumored that she befriended Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump, at least if Michael Wolff is to be believed, and I see no reason to doubt the point. In resigning, she praised them as heroes and Kushner as a genius. I see no reason either to suspect that she was the “anonymous” author behind the masturbatory anti-Trump insider op-ed, especially given her own public writing against it. But I find it hard to imagine that she did not, like the president’s fool daughter and son-in-law, see herself as one of the real adults, a deft and more sophisticated character entirely than the volcanic, mercurial president. In this, they all resemble the bumbling gym employees who form official Washington’s opposite number in “Burn After Reading”: Greed and overestimation of their own abilities lead them—most of them—to death and destruction at the hands of the very people they think they’re outsmarting.

There are of course other rumors that Haley will mount some kind of political challenge to Donald Trump, an absolute fantasy. She will, I suspect, reinvent herself in precisely the mold of a John Bolton, a peripatetic cable news beast who will lurk through whatever modest Democratic backlash Trump’s insanity unleashes, until a cleverer and subtler fascist in the early 2020s achieves power again and brings her back into the fold. “This is our opportunity,” says Frances McDormand in one of the film’s best scenes, “You don’t get many of these. You slip on the ice outside of, you know, a fancy restaurant . . . or something like this happens.”

Bernie Sanders Delivers Stirring Rebuke of Trump’s Authoritarianism

While Donald Trump took to the editorial page of USA Today on Wednesday to spew new lies about key social programs like Medicare and sow fresh divisions with unhinged rantings about the “radical socialist plans” of the Democratic Party, Sen. Bernie Sanders on Tuesday offered a scathing and far-reaching rebuke to Trump’s brand of politics by tackling head-on the threat posed by the president’s penchant for authoritarianism and his consistent stoking of social divisions.

In a speech delivered at the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, Sanders told the small audience that he wanted to “say a few words about a troubling trend in global affairs that gets far too little attention,” as he proceeded to describe a trend that both describes the America under Trump, but one also seen in nations across the globe.

“There is currently a struggle of enormous consequence taking place in the United States and throughout the world,” Sanders declared in his speech. “In it we see two competing visions. On one hand, we see a growing worldwide movement toward authoritarianism, oligarchy, and kleptocracy. On the other side, we see a movement toward strengthening democracy, egalitarianism, and economic, social, racial, and environmental justice.”

Sanders continued by drawing a picture in which an increasingly wealthy and powerful set of elites—not just in the U.S., but in Europe, Russia, the Middle East, South America, Asia, and elsewhere—are actively fomenting anti-democratic angst while butressed by the rise of “demagogues” who, like Trump domestically, “exploit people’s fears, prejudices and grievances to gain and hold on to power.”

In response to such forces, argued Sanders, “Those of us who believe in democracy, who believe that a government must be accountable to its people and not the other way around, must understand the scope of this challenge if we are to confront it effectively.”

And so, he added, “We need to counter oligarchic authoritarianism with a strong global progressive movement that speaks to the needs of working people, that recognizes that many of the problems we are faced with are the product of a failed status quo. We need a movement that unites people all over the world who don’t just seek to return to a romanticized past, a past that did not work for so many, but who strive for something better.”

With a direct hit on the Trumpian mantra of “Make America Great Again,” Sanders warned that looking backwards, though valuable in some respects, is not where a better, more equitable world is to be found.

Instead, he said, what the world needs if it wants to defeat “the forces of global oligarchy and authoritarianism” is a powerful and organized “international movement that mobilizes behind a vision of shared prosperity, security and dignity for all people, and that addresses the massive global inequality that exists, not only in wealth but in political power.”

In the end, Sanders observed, “Authoritarians seek power by promoting division and hatred. We will promote unity and inclusion.”

And, he concluded, “In a time of exploding wealth and technology, we have the potential to create a decent life for all people. Our job is to build on our common humanity and do everything that we can to oppose all of the forces, whether unaccountable government power or unaccountable corporate power, who try to divide us up and set us against each other. We know that those forces work together across borders. We must do the same. ”

Watch the full speech:

Read Sanders complete remarks, as prepared for delivery:

Thank you so much Dean Nasr for your introduction, to Johns Hopkins for inviting me here, and for all of you joining me here today, as well of those of you watching online.

In the United States, we pay a whole lot of attention to issues impacting the economy, healthcare, education, environment, criminal justice, immigration and, as we have recently seen, Supreme Court nominees. These are all enormously important issues.

With the exception of immediate and dramatic crises, however, foreign policy is not something that usually gets a whole lot of attention or debate. In fact, some political analysts have suggested that by and large we have a one-party foreign policy, where the basic elements of our approach are not often debated or challenged.

We spend $700 billion a year on the military, more than the next 10 nations combined. We have been at war in Afghanistan for 17 years, war in Iraq for 15 years, and we are currently involved militarily in Yemen – where a humanitarian crisis is taking place.

Meanwhile, 30 million people have no health insurance, our infrastructure is collapsing, and hundreds of thousands of bright young people cannot afford to go to college every year.

The time is long overdue for a vigorous discussion about our foreign policy, and how it needs to change in this new era.

Today, I want to say a few words about a troubling trend in global affairs that gets far too little attention. There is currently a struggle of enormous consequence taking place in the United States and throughout the world. In it we see two competing visions. On one hand, we see a growing worldwide movement toward authoritarianism, oligarchy, and kleptocracy. On the other side, we see a movement toward strengthening democracy, egalitarianism, and economic, social, racial, and environmental justice.

This struggle has consequences for the entire future of the planet — economically, socially, and environmentally.

In terms of the global economy, we see today massive and growing wealth and income inequality, where the world’s top one percent now owns more wealth than the bottom 99%, where a small number of huge financial institutions exert enormous impact over the lives of billions of people.

Further, many people in industrialized countries are questioning whether democracy can actually deliver for them. They are working longer hours for lower wages than they used to. They see big money buying elections, and they see a political and economic elite growing wealthier, even as their own children’s future grows dimmer.

In these countries, we often have political leaders who exploit these fears by amplifying resentments, stoking intolerance and fanning ethnic and racial hatreds among those who are struggling. We see this very clearly in our own country. It is coming from the highest level of our government.

It should be clear by now that Donald Trump and the right-wing movement that supports him is not a phenomenon unique to the United States. All around the world, in Europe, in Russia, in the Middle East, in Asia, Latin America, and elsewhere we are seeing movements led by demagogues who exploit people’s fears, prejudices and grievances to gain and hold on to power.

Just this past weekend, in Brazil’s presidential election, right-wing leader Jair Bolsonaro, who has been called “The Donald Trump of Brazil,” made a very strong showing in the first round of voting, coming up just short of an outright victory. Bolsonaro has a long record of attacks against immigrants, against minorities, against women, against LGBT people. Bolsonaro, who has said he loves Donald Trump, has praised Brazil’s former military dictatorship, and has said, among other things, that in order to deal with crime, police should simply be allowed to shoot more criminals. This is the person who may soon lead the world’s fifth most populous country, and its ninth largest economy.

Meanwhile, Brazil’s most popular politician, the former president Lula da Silva, is imprisoned on highly questionable charges, and prevented from running again.

Bolsonaro in Brazil is one example, there are others which I will discuss. But I think it is important that we understand that what we are seeing now in the world is the rise of a new authoritarian axis.

While the leaders who make up this axis may differ in some respects, they share key attributes: intolerance toward ethnic and religious minorities, hostility toward democratic norms, antagonism toward a free press, constant paranoia about foreign plots, and a belief that the leaders of government should be able use their positions of power to serve their own selfish financial interests.

Interestingly, many of these leaders are also deeply connected to a network of multi-billionaire oligarchs who see the world as their economic plaything.

Those of us who believe in democracy, who believe that a government must be accountable to its people and not the other way around, must understand the scope of this challenge if we are to confront it effectively. We need to counter oligarchic authoritarianism with a strong global progressive movement that speaks to the needs of working people, that recognizes that many of the problems we are faced with are the product of a failed status quo. We need a movement that unites people all over the world who don’t just seek to return to a romanticized past, a past that did not work for so many, but who strive for something better.

While this authoritarian trend certainly did not begin with Donald Trump, there’s no question that other authoritarian leaders around the world have drawn inspiration from the fact that the president of the world’s oldest and most powerful democracy is shattering democratic norms, is viciously attack an independent media and an independent judiciary, and is scapegoating the weakest and most vulnerable members of our society.

For example, Saudi Arabia is a country clearly inspired by Trump. This is a despotic dictatorship that does not tolerate dissent, that treats women as third-class citizens, and has spent the last several decades exporting a very extreme form of Islam around the world. Saudi Arabia is currently devastating the country of Yemen in a catastrophic war in alliance with the United States.

I would like to take a moment to note the disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a critic of the Saudi government who was last seen entering the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, last Tuesday. Over the weekend, Turkish authorities told reporters that they now believe Khashoggi was murdered in the Saudi consulate, and his body disposed of elsewhere. We need to know what happened here. If this is true, if the Saudi regime murdered a journalist critic in their own consulate, there must be accountability, and there must be an unequivocal condemnation by the United States. But it seems clear that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman feels emboldened by the Trump administration’s unquestioning support.

Further, it is hard to imagine that a country like Saudi Arabia would have chosen to start a fight this past summer with Canada over a relatively mild human rights criticism if Muhammad bin Salman – who is very close with Presidential son-in-law Jared Kushner – did not believe that the United States would stay silent. Three years ago, who would have imagined that the United States would refuse to take sides between Canada, our democratic neighbor and second largest trading partner, and Saudi Arabia on an issue of human rights – but that is exactly what happened.

It’s also hard to imagine that Israel’s Netanyahu government would have taken a number of steps – including passing the recent “Nation State law,” which essentially codifies the second-class status of Israel’s non-Jewish citizens, aggressively undermining the longstanding goal of a two-state solution, and ignoring the economic catastrophe in Gaza — if Netanyahu wasn’t confident that Trump would support him.

And then there is Trump’s cozy relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, whose intervention in our 2016 presidential election Trump still fails to fully admit. We face an unprecedented situation of an American president who for whatever reason refuses to acknowledge this attack on American democracy. Why is that? I am not sure what the answer is. Either he really doesn’t understand what has happened, or he is under Russian influence because of compromising information they may have on him, or because he is ultimately more sympathetic to Russia’s strongman form of government than he is to American democracy.

Even as he draws closer to authoritarian leaders like Putin, like Orban in Hungary, Erdogan in Turkey, Duterte in the Philippines, and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, Trump is needlessly increasing tensions with our democratic European allies over issues like trade, like NATO, like the Iran nuclear agreement. Let me be clear, these are important issues. But the way Trump has gratuitously disrespected these allies is not only ineffective deal-making, it will have enormous negative long-term consequences for the trans-Atlantic alliance.

Further, Trump’s ambassador to Germany, Richard Grenell, several months ago made clear the administration’s support for right-wing extremist parties across Europe. In other words, the U.S. administration is openly siding with the very forces challenging the democratic foundations of our longtime allies.

We need to understand that the struggle for democracy is bound up with the struggle against kleptocracy and corruption. That is true here in the United States as well as abroad. In addition to Trump’s hostility toward democratic institutions here in the United States, we have a billionaire president who, according to a recent report in the New York Times, acquired his wealth through illegal means, and now, as president, in an unprecedented way, has blatantly embedded his own economic interests and those of his cronies into the policies of government.

One of the consistent themes of reports coming out of the investigation into the Trump campaign is the effort of wealthy foreign interests seeking influence and access with Trump and his organization, and with close Trump associates seeking to trade that access for the promise of even more wealth. While the characters involved in these reports are particularly blatant and clumsy in their efforts, the details of these stories are not unique.

Never before have we seen the power of big money over governmental policy so clearly. Whether we’re talking about the Koch brothers spending hundreds of millions of dollars to dismantle environmental regulations that protect Americans’ health, or authoritarian monarchies like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar spending millions in fossil fuel wealth in Washington to advance the interests of their undemocratic regimes, or giant corporations supporting think tanks in order to produce policy recommendations that serve their own financial interests, the theme is the same. Powerful special interests use their wealth to influence government for their own selfish interests.

During the Congressional fight over the Republicans’ massive tax giveaway to the wealthy, some of my colleagues were very open this. Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina was very frank: If Republicans failed to pass the bill, he said “the financial contributions will stop.” This, he went on, “will be the end of us as a party.” I applaud Senator Graham for his honesty.

This corruption is so blatant, it’s no longer seen as remarkable. Just the other day, the lead sentence in a New York Times story about Republican mega-donor Sheldon Adelson was this: “The return on investment for many of the Republican Party’s biggest political patrons has been less than impressive this year.”

Let me repeat that: “The return on investment was less than impressive.” The idea that political donors expect a specific policy result in exchange for their contributions – a quid pro quo, the definition of corruption – is right out there in the open. It is no longer even seen as scandalous.

This sort of corruption is common among authoritarian regimes. In Russia, it is impossible to tell where the decisions of government end and the interests of Putin and his circle of multi-billionaire oligarchs begin. They operate as one unit. Similarly, in Saudi Arabia, there is no debate about separation because the natural resources of the state, valued at trillions of dollars, belong to the Saudi royal family.

In Hungary, far-right authoritarian-nationalist leader Victor Orban models himself after Putin in Russia, saying in a January interview that, “Putin has made his country great again.” Like Putin, Orban has risen to power by exploiting paranoia and intolerance of minorities, including outrageous anti-Semitic attacks on George Soros, but at the same time has managed to enrich his political allies and himself. In February, the Corruption Perception Index compiled by Transparency International ranked Hungary as the second most corrupt EU country.

We must understand that these authoritarians are part of a common front. They are in close contact with each other, share tactics and, as in the case of European and American right-wing movements, even share some of the same funders. For example, the Mercer family, supporters of the infamous Cambridge Analytica, have also been key backers of Donald Trump and of Breitbart news, which operates in Europe, the United States and Israel to advance the same anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim agenda. Sheldon Adelson gives generously to the Republican Party and right-wing causes in both the United States and Israel, promoting a shared agenda of intolerance and bigotry in both countries.

The truth is, however, that to effectively oppose right-wing authoritarianism, we cannot simply be on the defensive. We need to be proactive and understand that just defending the failed status quo of the last several decades is not good enough. In fact, we need to recognize that the challenges we face today are a product of that status quo.

What do I mean by that?

Here in the United States, in the UK, in France, and in many other countries around the world, people are working longer hours for stagnating wages, and worry that their children will have a lower standard of living than they do.

So our job is not to accept the status quo, not to accept massive levels of wealth and income inequality where the top 1% of the world’s population own half the planet’s wealth, while the bottom 70% of the working age population account for just 2.7% of global wealth. It is not to accept a declining standard of living for many workers around the world, not to accept a reality of 1.4 billion people living in extreme poverty where millions of children die of easily preventable illnesses.

Our job is to fight for a future in which public policy and new technology and innovation work to benefit all of the people, not just the few.

Our job is to support governments around the world that will end the absurdity of the rich and multinational corporations stashing over $21 trillion dollars in offshore bank accounts to avoid paying their fair share of taxes, and then demanding that their respective governments impose an austerity agenda on their working families.

Our job is to rally the entire planet to stand up to the fossil fuel industry which continues to make huge profits while their carbon emissions destroy the planet for our children and grandchildren.

The scientific community is virtually unanimous in telling us that climate change is real, climate change is caused by human activity, and climate change is already causing devastating harm throughout the world. Further, what the scientists tell us is that if we do not act boldly to address the climate crisis, this planet will see more drought, more floods, more extreme weather disturbances, more acidification of the ocean, more rising sea levels, and, as a result of mass migrations, there will be more threats to global stability and security.

A new report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released just yesterday warns that we only have about twelve years to take urgent and unprecedented action to prevent a rise in the planet’s temperature that would cause irreversible damage.

The threat of climate change is a very clear example of where American leadership can make a difference. Europe can’t do it alone, China can’t do it alone, and the United States can’t do it alone. This is a crisis that calls out for strong international cooperation if we are to leave our children and grandchildren a planet that is healthy and habitable. American leadership — the economic and scientific advantages and incentives that only America can offer — is hugely important for facilitating this effort.

In the struggle to preserve and expand democracy, our job is to fight back against the coordinated effort, strongly supported by the president and funded by oligarchs like the Koch brothers, to make it harder to for American citizens – often people of color, poor people, and young people – to vote. Not only do oligarchs want to buy elections, but voter suppression is a key element of their plan to maintain power.

Our job is to push for trade policies that don’t just benefit large multinational corporations and hurt working people throughout the world as they are written out of public view.

Our job is to fight back against brutal immigration policies that require separating migrant families when they are detained at the border, and require children to be put in cages. Migrants and refugees should be treated with compassion and respect when they reach Europe or the United States. Yes, we need better international cooperation to address the flow of migrants across borders, but the solution is not to build walls and amplify the cruelty toward those fleeing impossible conditions as a deterrence strategy.

Our job is to make sure that we commit more resources to taking care of people than we do on weapons designed to kill them. It is not acceptable that, with the Cold War long behind us, countries around the world spend over a trillion dollars a year on weapons of destruction, while millions of children die of easily treatable diseases.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, countries around the world spend a total of $1.7 trillion a year on the military. $1.7 trillion. Think of what we could accomplish if even a fraction of this amount were redirected to more peaceful ends? The head of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization has said we could end the global food crisis for $30 billion a year. That’s less than two percent of what we spend on weapons.

Columbia University’s Jeffrey Sachs, one of the world’s leading experts on economic development and the fight against poverty, has estimated that the cost to end world poverty is $175 billion per year for 20 years, about ten percent of what the world spends on weapons.

Donald Trump thinks we should spend more on these weapons. I think we should spend less.

Let us remember what President Dwight D. Eisenhower said in 1953, just a few months after taking office. “Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children.”

And just as he was about to leave office in 1961, Eisenhower was so concerned the growing power of the weapons industry that he issued this warning: “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.” We have seen that potential more than fulfilled over the past decades. It is time for us to stand up and say: There is a better way to use our wealth.

In closing, let me simply that in order to effectively combat the forces of global oligarchy and authoritarianism, we need an international movement that mobilizes behind a vision of shared prosperity, security and dignity for all people, and that addresses the massive global inequality that exists, not only in wealth but in political power.

Such a movement must be willing to think creatively and boldly about the world that we would like to see. While the authoritarian axis is committed to tearing down a post-World War II global order that they see as limiting their access to power and wealth, it is not enough for us to simply defend that order as it exists.

We must look honestly at how that order has failed to deliver on many of its promises, and how authoritarians have adeptly exploited those failures in order to build support for their agenda. We must take the opportunity to reconceptualize a global order based on human solidarity, an order that recognizes that every person on this planet shares a common humanity, that we all want our children to grow up healthy, to have a good education, have decent jobs, drink clean water, breathe clean air and to live in peace. Our job is to reach out to those in every corner of the world who shares these values, and who are fighting for a better world.

Authoritarians seek power by promoting division and hatred. We will promote unity and inclusion.

In a time of exploding wealth and technology, we have the potential to create a decent life for all people. Our job is to build on our common humanity and do everything that we can to oppose all of the forces, whether unaccountable government power or unaccountable corporate power, who try to divide us up and set us against each other. We know that those forces work together across borders. We must do the same.

Billionaire Sheldon Adelson Has Trump in His Pocket

LATE ON A THURSDAY evening in February 2017, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s plane landed at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland for his first visit with President Donald Trump. A few hours earlier, the casino magnate Sheldon Adelson’s Boeing 737, which is so large it can seat 149 people, touched down at Reagan National Airport after a flight from Las Vegas.

Adelson dined that night at the White House with Trump, Jared Kushner and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Adelson and his wife, Miriam, were among Trump’s biggest benefactors, writing checks for $20 million in the campaign and pitching in an additional $5 million for the inaugural festivities.

Adelson was in town to see the Japanese prime minister about a much greater sum of money. Japan, after years of acrimonious public debate, has legalized casinos. For more than a decade, Adelson and his company, Las Vegas Sands, have sought to build a multibillion-dollar casino resort there. He has called expanding to the country, one of the world’s last major untapped markets, the “holy grail.” Nearly every major casino company in the world is competing to secure one of a limited number of licenses to enter a market worth up to $25 billion per year. “This opportunity won’t come along again, potentially ever,” said Kahlil Philander, an academic who studies the industry.

The morning after his White House dinner, Adelson attended a breakfast in Washington with Abe and a small group of American CEOs, including two others from the casino industry. Adelson and the other executives raised the casino issue with Abe, according to an attendee.

Adelson had a potent ally in his quest: the new president of the United States. Following the business breakfast, Abe had a meeting with Trump before boarding Air Force One for a weekend at Mar-a-Lago. The two heads of state dined with Patriots owner Bob Kraft and golfed at Trump National Jupiter Golf Club with the South African golfer Ernie Els. During a meeting at Mar-a-Lago that weekend, Trump raised Adelson’s casino bid to Abe, according to two people briefed on the meeting. The Japanese side was surprised.

“It was totally brought up out of the blue,” according to one of the people briefed on the exchange. “They were a little incredulous that he would be so brazen.” After Trump told Abe he should strongly consider Las Vegas Sands for a license, “Abe didn’t really respond, and said thank you for the information,” this person said.

Trump also mentioned at least one other casino operator. Accounts differ on whether it was MGM or Wynn Resorts, then run by Trump donor and then-Republican National Committee finance chairman Steve Wynn. The Japanese newspaper Nikkei reported the president also mentioned MGM and Abe instructed an aide who was present to jot down the names of both companies. Questioned about the meeting, Abe said in remarks before the Japanese legislature in July that Trump had not passed on requests from casino companies but did not deny that the topic had come up.

The president raising a top donor’s personal business interests directly with a foreign head of state would violate longstanding norms. “That should be nowhere near the agenda of senior officials,” said Brian Harding, a Japan expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “U.S.-Japan relations is about the security of the Asia-Pacific, China and economic issues.”

Adelson has told his shareholders to expect good news. On a recent earnings call, Adelson cited unnamed insiders as saying Sands’ efforts to win a place in the Japanese market will pay off. “The estimates by people who know, say they know, whom we believe they know, say that we’re in the No. 1 pole position,” he said.

After decades as a major Republican donor, Adelson is known as an ideological figure, motivated by his desire to influence U.S. policy to help Israel. “I’m a one-issue person. That issue is Israel,” he said last year. On that issue — Israel — Trump has delivered. The administration has slashed funding for aid to Palestinian refugees and scrapped the Iran nuclear deal. Attending the recent opening of the U.S. embassy in Jerusalem, Adelson seemed to almost weep with joy, according to an attendee.

But his reputation as an Israel advocate has obscured a through-line in his career: He has used his political access to push his financial self-interest. Not only has Trump touted Sands’ interests in Japan, but his administration also installed an executive from the casino industry in a top position in the U.S. embassy in Tokyo. Adelson’s influence reverberates through this administration. Cabinet-level officials jump when he calls. One who displeased him was replaced. He has helped a friend’s company get a research deal with the Environmental Protection Agency. And Adelson has already received a windfall from Trump’s new tax law, which particularly favored companies like Las Vegas Sands. The company estimated the benefit of the law at $1.2 billion.

Adelson’s influence is not absolute: His company’s casinos in Macau are vulnerable in Trump’s trade war with China, which controls the former Portuguese colony near Hong Kong. If the Chinese government chose to retaliate by targeting Macau, where Sands has several large properties, it could hurt Adelson’s bottom line. So far, there’s no evidence that has happened.

The White House declined to comment on Adelson. The Japanese Embassy in Washington declined to comment. Sands spokesman Ron Reese declined to answer detailed questions but said in a statement: “The gaming industry has long sought the opportunity to enter the Japan market. Gaming companies have spent significant resources there on that effort and Las Vegas Sands is no exception.”

Reese added: “If our company has any advantage it would be because of our significant Asian operating experience and our unique convention-based business model. Any suggestion we are favored for some other reason is not based on the reality of the process in Japan or the integrity of the officials involved in it.”

With a fortune estimated at $35 billion, Adelson is the 21st-richest person in the world, according to Forbes. In August, when he celebrated his 85th birthday in Las Vegas, the party stretched over four days. Adelson covered guests’ expenses. A 92-year-old Tony Bennett and the Israeli winner of Eurovision performed for the festivities. He is slowing down physically; stricken by neuropathy, he uses a motorized scooter to get around and often stands up with the help of a bodyguard. He fell and broke three ribs while on a ferry from Macau to Hong Kong last November.

Yet Adelson has spent the Trump era hustling to expand his gambling empire. With Trump occupying the White House, Adelson has found the greatest political ally he’s ever had.

“I would put Adelson at the very top of the list of both access and influence in the Trump administration,” said Craig Holman of the watchdog group Public Citizen. “I’ve never seen anything like it before, and I’ve been studying money in politics for 40 years.”

ADELSON GREW UP POOR in Boston, the son of a cabdriver with a sixth-grade education. According to his wife, Adelson was beaten up as a kid for being Jewish. A serial entrepreneur who has started or acquired more than 50 different businesses, he had already made and lost his first fortune by the late 1960s, when he was in his mid-30s.

It took him until the mid-1990s to become extraordinarily rich. In 1995, he sold the pioneering computer trade show Comdex to the Japanese conglomerate SoftBank for $800 million. He entered the gambling business in earnest when his Venetian casino resort opened in 1999 in Las Vegas. With its gondola rides on faux canals, it was inspired by his honeymoon to Venice with Miriam, who is 12 years younger than Adelson.

It’s been said that Trump is a poor person’s idea of a rich person. Adelson could be thought of as Trump’s idea of a rich person. A family friend recalls Sheldon and Miriam’s two sons, who are now in college, getting picked up from school in stretch Hummer limousines and his home being so large it was stocked with Segway transporters to get around. A Las Vegas TV station found a few years ago that, amid a drought, Adelson’s palatial home a short drive from the Vegas Strip had used nearly 8 million gallons of water in a year, enough for 55 average homes. Adelson will rattle off his precise wealth based on the fluctuation of Las Vegas Sands’ share price, said his friend the New York investor Michael Steinhardt. “He’s very sensitive to his net worth,” Steinhardt said.

Trump entered the casino business several years before Adelson. In the early 1990s, both eyed Eilat in southern Israel as a potential casino site. Neither built there. Adelson “didn’t have a whole lot of respect for Trump when Trump was operating casinos. He was dismissive of Trump,” recalled one former Las Vegas Sands official. In an interview in the late ’90s, Adelson lumped Trump with Wynn: “Both of these gentlemen have very big egos,” Adelson said. “Well, the world doesn’t really care about their egos.”

Today, in his rare public appearances, Adelson has a grandfatherly affect. He likes to refer to himself as “Self” (“I said to myself, ‘Self …’”). He makes Borscht Belt jokes about his short stature: “A friend of mine says, ‘You’re the tallest guy in the world.’ I said, ‘How do you figure that?’ He says, ‘When you stand on your wallet.’”

By the early 2000s, Adelson’s Las Vegas Sands had surpassed Trump’s casino operations. While Trump was getting bogged down in Atlantic City, Adelson’s properties thrived. When Macau opened up a local gambling monopoly, Adelson bested a crowded field that included Trump to win a license. Today, Macau accounts for more than half of Las Vegas Sands’ roughly $13 billion in annual revenue.

Trump’s casinos went bankrupt, and now he is out of the industry entirely. By the mid-2000s, Trump was playing the role of business tycoon on his reality show, “The Apprentice.” Meanwhile, Adelson aggressively expanded his empire in Macau and later in Singapore. His company’s Moshe Safdie-designed Marina Bay Sands property there, with its rooftop infinity pool, featured prominently in the recent hit movie “Crazy Rich Asians.”

While their business trajectories diverged, Adelson and Trump have long shared a willingness to sue critics, enemies and business associates. Multiple people said they were too afraid of lawsuits to speak on the record for this story. In 1989, after the Nevada Gaming Control Board conducted a background investigation of Adelson, it found he had already been personally involved in around 100 civil lawsuits, according to the book “License to Steal,” a history of the agency. That included matters as small as a $600 contractual dispute with a Boston hospital.

The lawsuits have continued even as Adelson became so rich the amounts of money at stake hardly mattered. In one case, Adelson was unhappy with the quality of construction on one of his beachfront Malibu, California, properties and pursued a legal dispute with the contractor for more than seven years, going through a lengthy series of appeals and cases in different courts. Adelson sued a Wall Street Journal reporter for libel over a single phrase — a description of him as “foul-mouthed” — and fought the case for four years before it was settled, with the story unchanged. In a particularly bitter case in Massachusetts Superior Court in the 1990s, his sons from his first marriage accused him of cheating them out of money. Adelson prevailed.

Adelson rarely speaks to the media any more, with occasional exceptions for friendly business journalists or on stage at conferences, usually interviewed by people to whom he has given a great deal of money. “He keeps a very tight inner circle,” said a casino industry executive who has known Adelson for decades. Adelson declined to comment for this story.

ADELSON ONCE TOLD a reporter of entering the casino business late in life, “I loved being an outsider.” For nearly a decade he played that role in presidential politics, bankrolling the opposition to the Obama administration. As with some of his early entrepreneurial forays, he dumped money for little return, his political picks going bust. In 2008, he backed Rudy Giuliani. As America’s Mayor faded, he came on board late with the John McCain campaign. In 2012, he almost single-handedly funded Newt Gingrich’s candidacy. Gingrich spent a few weeks atop the polls before his candidacy collapsed. Adelson became a late adopter of Mitt Romney.

In 2016, the Adelsons didn’t officially endorse a candidate for months. Trump used Adelson as a foil, an example of the well-heeled donors who wielded outsized influence in Washington. “Sheldon or whoever — you could say Koch. I could name them all. They’re all friends of mine, every one of them. I know all of them. They have pretty much total control over the candidate,” Trump said on Fox News in October 2015. “Nobody controls me but the American public.” In a pointed tweet that month, Trump said: “Sheldon Adelson is looking to give big dollars to [Marco] Rubio because he feels he can mold him into his perfect little puppet. I agree!”

Despite Trump’s barbs, Adelson had grown curious about the candidate and called his friend Steinhardt, who founded the Birthright program that sends young Jews on free trips to Israel. Adelson is now the program’s largest funder.

“I called Kushner and I said Sheldon would like to meet your father-in-law,” Steinhardt recalled. “Kushner was excited.” Trump got on a plane to Las Vegas. “Sheldon has strong views when it comes to the Jewish people; Trump recognized that, and a marriage was formed.”

Trump and his son-in-law Kushner courted Adelson privately, meeting several times in New York and Las Vegas. “Having Orthodox Jews like Jared and Ivanka next to him and so many common people in interest gave a level of comfort to Sheldon,” said Ronn Torossian, a New York public relations executive who knows both men. “Someone who lets their kid marry an Orthodox Jew and then become Orthodox is probably going to stand pretty damn close to Israel.”

Miriam Adelson, a physician born and raised in what became Israel, is said to be an equal partner in Sheldon Adelson’s political decisions. He has said the interests of the Jewish state are at the center of his worldview, and his views align with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-of-center approach to Iran and Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories.

Adelson suggested in 2014 that Israel doesn’t need to be a democracy. “I think God didn’t say anything about democracy,” Adelson said. “He didn’t talk about Israel remaining as a democratic state.” On a trip to the country several years ago, on the eve of his young son’s bar mitzvah, Adelson said, “Hopefully he’ll come back; his hobby is shooting. He’ll come back and be a sniper for the IDF,” referring to the Israel Defense Forces.

On domestic issues, Adelson is more Chamber of Commerce Republican than movement conservative or Trumpian populist. He is pro-choice and has called for work permits and a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, a position sharply at odds with Trump’s. While the Koch brothers, his fellow Republican megadonors, have evinced concern over trade policy and distaste for Trump, Adelson has proved flexible, putting aside any qualms about Trump’s business acumen or ideological misgivings. In May 2016, he declared in a Washington Post op-ed that he was endorsing Trump. He wrote that Trump represented “a CEO success story that exemplifies the American spirit of determination, commitment to cause and business stewardship.”

The Adelsons came through with $20 million in donations to the pro-Trump super PAC, part of at least $83 million in donations to Republicans. By the time of the October 2016 release of the Access Hollywood tape featuring Trump bragging about sexual assault, Adelson was among his staunchest supporters. “Sheldon Adelson had Donald Trump’s back,” said Steve Bannon in a speech last year, speaking of the time after the scandal broke. “He was there.”

In December 2016, Adelson donated $5 million to the Trump inaugural festivities. The Adelsons had better seats at Trump’s inauguration than many Cabinet secretaries. The whole family, including their two college-age sons, came to Washington for the celebration. One of his sons posted a picture on Instagram of the event with the hashtag #HuckFillary.

The investment paid off in access and in financial returns. Adelson has met with Trump or visited the White House at least six times since Trump’s election victory. The two speak regularly. Adelson has also had access to others in the White House. He met privately with Vice President Mike Pence before Pence gave a speech at Adelson’s Venetian resort in Las Vegas last year. “He just calls the president all the time. Donald Trump takes Sheldon Adelson’s calls,” said Alan Dershowitz, who has done legal work for Adelson and advised Trump.

Adelson’s tens of millions in donations to Trump have already been paid back many times over by the new tax law. While all corporations benefited from the lower tax rate in the new law, many incurred an extra bill in the transition because profits overseas were hit with a one-time tax. But not Sands. Adelson’s company hired lobbyists to press Trump’s Treasury Department and Congress on provisions that would help companies like Sands that paid high taxes abroad, according to public filings and tax experts. The lobbying effort appears to have worked. After Trump signed the tax overhaul into law in December, Las Vegas Sands recorded a benefit from the new law the company estimated at $1.2 billion.

The Adelson family owns 55 percent of Las Vegas Sands, which is publicly traded, according to filings. The Treasury Department didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Now as Trump and the Republican Party face a reckoning in the midterm elections in November, they have once again turned to Adelson. He has given at least $55 million so far.

IN 2014, ADELSON TOLD an interviewer he was not interested in building a dynasty. “I want my legacy to be that I helped out humankind,” he said, underscoring his family’s considerable donations to medical research. But he gives no indication of sticking to a quiet life of philanthropy. In the last four years, he has used the Sands’ fleet of private jets, assiduously meeting with world leaders and seeking to build new casinos in Japan, Korea and Brazil.

He is closest in Japan. Japan has been considering lifting its ban on casinos for years, in spite of majority opposition in polls from a public that is wary of the social problems that might result. A huge de facto gambling industry of the pinball-like game pachinko has long existed in the country, historically associated with organized crime and seedy parlors filled with cigarette-smoking men. Opposition to allowing casinos is so heated that a brawl broke out in the Japanese legislature this summer. But lawmakers have moved forward on legalizing casinos and crafted regulations that hew to Adelson’s wishes.

“Japan is considered the next big market. Sheldon looks at it that way,” said a former Sands official. Adelson envisions building a $10 billion “integrated resort,” which in industry parlance refers to a large complex featuring a casino with hotels, entertainment venues, restaurants and shopping malls.

The new Japanese law allows for just three licenses to build casinos in cities around the country, effectively granting valuable local monopolies. At least 13 companies, including giants like MGM and Genting, are vying for a license. Even though Sands is already a strong contender because of its size and its successful resort in Singapore, some observers in Japan believe Adelson’s relationship with Trump has helped move Las Vegas Sands closer to the multibillion-dollar prize.

Just a week after the U.S. election, Prime Minister Abe arrived at Trump Tower, becoming the first foreign leader to meet with the president-elect. Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner were also there. Abe presented Trump with a gilded $3,800 golf driver. Few know the details of what the Trumps and Abe discussed at the meeting. In a break with protocol, Trump’s transition team sidelined the State Department, whose Japan experts were never briefed on what was said. “There was a great deal of frustration,” said one State Department official. “There was zero communication from anyone on Trump’s team.”

In another sign of Adelson’s direct access to the incoming president and ties with Japan, he secured a coveted Trump Tower meeting a few weeks later for an old friend, the Japanese billionaire businessman Masayoshi Son. Son’s company, SoftBank, had bought Adelson’s computer trade show business in the 1990s. A few years ago, Adelson named Son as a potential partner in his casino resort plans in Japan. Son’s SoftBank, for its part, owns Sprint, which has long wanted to merge with T-Mobile but needs a green light from the Trump administration. A beaming Son emerged from the meeting in the lobby of Trump Tower with the president-elect and promised $50 billion in investments in the U.S.

When Trump won the election in November 2016, the casino bill had been stalled in the Japanese Diet. One month after the Trump-Abe meeting, in an unexpected move in mid-December, Abe’s ruling coalition pushed through landmark legislation authorizing casinos, with specific regulations to be ironed out later. There was minimal debate on the controversial bill, and it passed at the very end of an extraordinary session of the legislature. “That was a surprise to a lot of stakeholders,” said one former Sands executive who still works in the industry. Some observers suspect the timing was not a coincidence. “After Trump won the election in 2016, the Abe government’s efforts to pass the casino bill shifted into high gear,” said Yoichi Torihata, a professor at Shizuoka University and opponent of the casino law.

On a Las Vegas Sands earnings call a few days after Trump’s inauguration, Adelson touted that Abe had visited the company’s casino resort complex in Singapore. “He was very impressed with it,” Adelson said. Days later, Adelson attended the February breakfast with Abe in Washington, after which the prime minister went on to Mar-a-Lago, where the president raised Las Vegas Sands. A week after that, Adelson flew to Japan and met with the secretary general of Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party in Tokyo.

The casino business is one of the most regulated industries in the world, and Adelson has always sought political allies. To enter the business in 1989, he hired the former governor of Nevada to represent him before the state’s gaming commission. In 2001, according to court testimony reported in the New Yorker, Adelson intervened with then-House Majority Whip Rep. Tom DeLay, to whom he was a major donor, at the behest of a Chinese official over a proposed House resolution that was critical of the country’s human rights record. At the time, Las Vegas Sands was seeking entry into the Macau market. The resolution died, which Adelson attributed to factors other than his intervention, according to the magazine.

In 2015, he purchased the Las Vegas Review-Journal, the state’s largest newspaper, which then published a lengthy investigative series on one of Adelson’s longtime rivals, the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, which runs a convention center that competes with Adelson’s. (The paper said Adelson had no influence over its coverage.)

In Japan, Las Vegas Sands’ efforts have accelerated in the last year. Adelson returned to the country in September 2017, visiting top officials in Osaka, a possible casino site. In a show of star power in October, Sands flew in David Beckham and the Eagles’ Joe Walsh for a press conference at the Palace Hotel Tokyo. Beckham waxed enthusiastic about his love of sea urchin and declared, “Las Vegas Sands is creating fabulous resorts all around the world, and their scale and vision are impressive.”

Adelson appears emboldened. When he was in Osaka last fall, he publicly criticized a proposal under consideration to cap the total amount of floor space devoted to casinos in the resorts that have been legalized. In July, the Japanese Diet passed a bill with more details on what casinos will look like and laying out the bidding process. The absolute limit on casino floor area had been dropped from the legislation.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has made an unusual personnel move that could help advance pro-gambling interests. The new U.S. ambassador, an early Trump campaign supporter and Tennessee businessman named William Hagerty, hired as his senior adviser an American executive working on casino issues for the Japanese company SEGA Sammy. Joseph Schmelzeis left his role as senior adviser on global government and industry affairs for the company in February to join the U.S. Embassy. (He has not worked for Sands.)

A State Department spokesperson said that embassy officials had communicated with Sands as part of “routine” meetings and advice provided to members of the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan. The spokesperson said that “Schmelzeis is not participating in any matter related to integrated resorts or Las Vegas Sands.”

Japanese opposition politicians have seized on the Adelson-Trump-Abe nexus. One, Tetsuya Shiokawa, said this year that he believes Trump has been the unseen force behind why Abe’s party has “tailor-made the [casino] bill to suit foreign investors like Adelson.” In the next stage of the process, casino companies will complete their bids with Japanese localities.

ADELSON’S INFLUENCE has spread across the Trump administration. In August 2017, the Zionist Organization of America, to which the Adelsons are major donors, launched a campaign against National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster. ZOA chief Mort Klein charged McMaster “clearly has animus toward Israel.”

Adelson said he was convinced to support the attack on McMaster after Adelson spoke with Safra Catz, the Israeli-born CEO of Oracle, who “enlightened me quite a bit” about McMaster, according to an email Klein later released to the media. Adelson pressed Trump to appoint the hawkish John Bolton to a high position, The New York Times reported. In March, Trump fired McMaster and replaced him with Bolton. The president and other cabinet officials also clashed with McMaster on policy and style issues.

For Scott Pruitt, the former EPA administrator known as an ally of industry, courting Adelson meant developing a keen interest in an unlikely topic: technology that generates clean water from air. An obscure Israeli startup called Watergen makes machines that resemble air conditioners and, with enough electricity, can pull potable water from the air.

Adelson doesn’t have a stake in the company, but he is old friends with the Israeli-Georgian billionaire who owns the firm, Mikhael Mirilashvili, according to the head of Watergen’s U.S. operation, Yehuda Kaploun. Adelson first encountered the technology on a trip to Israel, Kaploun said. Dershowitz is also on the company’s board.

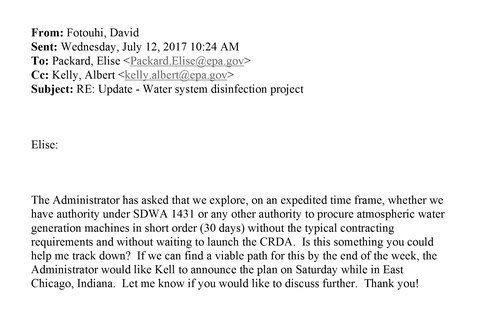

Just weeks after being confirmed, Pruitt met with Watergen executives at Adelson’s request. Pruitt promptly mobilized dozens of EPA officials to ink a research deal under which the agency would study Watergen’s technology. EPA officials immediately began voicing concerns about the request, according to hundreds of previously unreported emails obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. They argued that the then-EPA chief was violating regular procedures.

Pruitt, according to one email, asked that staffers explore “on an expedited time frame” whether a deal could be done “without the typical contracting requirements.” Other emails described the matter as “very time sensitive” and having “high Administrator interest.”

A veteran scientist at the agency warned that the “technology has been around for decades,” adding that the agency should not be “focusing on a single vendor, in this case Watergen.” Officials said that Watergen’s technology was not unique, noting there were as many as 70 different suppliers on the market with products using the same concept. Notes from a meeting said the agency “does not currently have the expertise or staff to evaluate these technologies.” Agency lawyers “seemed scared” about the arrangement, according to an internal text exchange. The EPA didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt pushed the agency to ink a research deal with a company owned by Adelson’s friend. Pruitt asked if a deal could be done “without the typical contracting requirements.”

Then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt pushed the agency to ink a research deal with a company owned by Adelson’s friend. Pruitt asked if a deal could be done “without the typical contracting requirements.”Watergen got its research deal. It’s not known how much money the agency has spent on the project. The technology was shipped to a lab in Cincinnati, and Watergen said the government will produce a report on its study. Pruitt planned to unveil the deal on a trip to Israel, which was also planned with the assistance of Adelson, The Washington Post reported. But amid multiple scandals, the trip never happened.

Other parts of the Trump administration have also been friendly to Watergen. Over the summer, Mirilashvili attended the U.S. Embassy in Israel’s Fourth of July party, where he was photographed grinning and sipping water next to one of the company’s machines on display. Kaploun said U.S. Ambassador David Friedman’s staff assisted the company to help highlight its technology.

A State Department spokesperson said Watergen was one of many private sponsors of the embassy party and was “subject to rigorous vetting.” The embassy is now considering leasing or buying a Watergen unit as part of a “routine procurement action,” the spokesperson said.

A Mirilashvili spokesman said in a statement that Adelson and Mirilashvili “have no business ties with each other.” The spokesman added that Adelson had been briefed on the company’s technology by Watergen engineers and “Adelson has also expressed an interest in the ability of this Israeli technology to save the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans who are affected by water pollution.”

EVEN AS THE CASINO business looks promising in Japan, China has been a potential trouble spot for Adelson. Few businesses are as vulnerable to geopolitical winds as Adelson’s. The majority of Sands’ value derives from its properties in Macau. It is the world’s gambling capital, and China’s central government controls it.

“Sheldon Adelson highly values direct engagement in Beijing,” a 2009 State Department cable released by WikiLeaks says, “especially given the impact of Beijing’s visa policies on the company’s growing mass market operations in Macau.”