Chris Hedges's Blog, page 433

October 26, 2018

Some of Our Biggest Cheerleaders for War Are Not Who You Think

Earlier this month, the United States celebrated a dubious anniversary. On Oct. 7, 2001, President George W. Bush invaded Afghanistan, marking the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom—a quagmire that continues to this day under the code name Operation Freedom’s Sentinel. The war is now the second longest in American history, next to Vietnam, and as Maj. Danny Sjursen noted in a recent essay for Truthdig, “teenagers born after 9/11 will begin to join the military and, eventually, fight” in its battles. Yet despite this, or perhaps because of it, the conflict remains out of sight and out of mind for an overwhelming majority of Americans.

Lyle Jeremy Rubin refuses to remain silent. A Ph.D. candidate, former U.S. Marine and member of About Face: Veterans Against the War, he contends that the public’s poor understanding of the conflict is matched only by that of the country’s political and media elite. Rubin has grown especially disillusioned with liberals and Democrats whose purportedly peaceful politics have proved to be anything but. As he tells Robert Scheer, “Celebrated commenters like Rachel Maddow and Lawrence O’Donnell fail to cover America’s ongoing wars and the roles some of their favorite guests have played in expanding them.”

In the latest episode of “Scheer Intelligence,” Rubin expounds on a range of topics including progressive media and the corrupting influence of arms dealing in U.S. foreign policy. “I mean we are by far the biggest arms dealer in the world,” he says. “And a lot of the enemies, the official enemies that our government has, [were] in one way or another created by these arms deals. … We’re making a lot of money by selling [Saudi Arabia] arms that are being used in a genocide in Yemen. And the discussion’s just nowhere to be found.”

Rubin also examines the recent murder of Washington Post writer Jamal Khashoggi, and how the Trump presidency has laid bare the true nature of the U.S.-Saudi relationship for all the world to see, voluntarily or not. “This is where I think Trump was right when he talked about why the United States wasn’t going to do much in response to the assassination of the Saudi Arabian journalist,” he continues. “There’s a lot of jobs on the line when it comes to these arms deals.”

Finally, Rubin explores what it means to be a patriot with an unabashed authoritarian in the Oval Office—one who regularly targets professional athletes for refusing to stand during the National Anthem: “Veteran friends I know, both on the left and the right … [are all] somewhat disgusted by the way that [they’re] used as political props.”

Listen to his interview with Robert Scheer below:

The Blight of Fracking Seeps Into America’s Foundations

“Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America”

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

“Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America”

A book by Eliza Griswold

I was raised in a village named for an ideal of friendship, or as a sign at the edge of town puts it, “friendly relations.” Amity, Pennsylvania, is perched on a canted ridgeline; a tight cluster founded in the era of the American Revolution when my mother’s stone house and other still-standing original buildings were put up within a rugged frontier forest.

My hometown is now the subject of Eliza Griswold’s new book, “Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America.” The place she depicts is caught in an uneasy dance between industry and agriculture, by turns shabby and bucolic, conservative and insular, equally influenced by its proximity to Pittsburgh and West Virginia. Some places are tidy; others have old Pepsi machines on the porches.

We lived there because in the early 1970s, my mom got a job teaching art at a small nearby college, and she and my dad decided to buy and fix up the stone house, an Amity landmark. They both had long hair and had been to college; they liked books and jazz and PBS, and they didn’t go to church.

The place where I grew up, but never quite fit in, went through a significant historical shift in the last decade as the natural gas boom laid down a web of heavy industry over the farmland of my formative years. As a center of the business, Washington County—which includes Amity—now hosts more frack wells than any other county in the state: 1,146 of them, which is one and a third for each of its hilly, green square miles.

Click here to read long excerpts from “ Amity and Prosperity ” at Google Books.

One of these was drilled in 2012 a few hundred yards from where my dad lives. He designed his house with windows that framed the choicest views. Now the crest of the near hilltop has been amputated, making a flat place for a well to sit.

Based on years of immersive reporting, Griswold’s expertly constructed book follows the legal battle that ensued when a single frack site began to affect three neighboring families. Her heroes are the Haneys: Stacey, a nurse and single mom, and her two kids, Harley and Paige. When we meet Harley, he’s a 14-year-old hobbled by a mysterious ailment, a stomach complaint bad enough to have kept him out of school for most of seventh grade.

By the end of the book, his mother’s dogged legal fight against Range Resources, the gas company whose facilities have poisoned the Haneys’ water and air, has reached its conclusion, and nearly eight years have passed during which the family has barely skirted homelessness and struggled to regain its health.

It’s a sickening story, and Griswold—the kind of reporter who can convince a subject to let her reveal the message inside a Valentine card, and who notices what color somebody’s refrigerator is—painstakingly builds the narrative amid its historical and social context.

Stacey Haney could not be a more perfect protagonist for Griswold’s narrative. The daughter of a laid-off steelworker father and a housekeeper mother, she strives to offer her own children a middle-class lifestyle. Yet she holds onto a thread that connects her to the older way of life in Amity, the agrarian way that binds people to the land; she wants her kids to grasp that thread too, through raising livestock and hunting.

Her grit and hard work may have allowed her to succeed in her goals if she hadn’t lived atop the Marcellus Shale, which harbors an ocean of natural gas, the largest source in the United States. Her burdens come to include not only the everyday ones shared by single mothers everywhere, but also a host of degrading circumstances caused by a frack site uphill from her farmhouse. She must endure watching her children be deposed by industry lawyers, living in a camper in her parents’ driveway, delivering flyers door-to-door to advertise that she’s looking for a home.

The Haneys are far from the only family to suffer fracking-related pollution; more than 4,000 Pennsylvanians have formally complained to the DEP about tainted drinking water. In a nearby county, the state Department of Environmental Protection has also reported a link between frack sites and minor earthquakes.

It’s impossible, as a reader, not to empathize with Stacey, as Griswold herself clearly does. Yet some of the Haneys’ neighbors and even relatives viewed her with suspicion.

For example, one of her cousins was making money from the gas boom, and his son worked for Range Resources. As for Stacey’s story of sick kids and dying animals, he doubted it was really true. In Griswold’s words, “[H]e just thought it sounded extreme.”

* * *

For me, reading Griswold’s book has the temporary immersive interest of any well-told story, but that interest is mixed with the heaviness of permanent firsthand knowledge. My heart jumps at all the familiar places, creeks, and roads, and the people who I know, remember, were friends of my brothers, or taught in my school district.

But I’m reading the book from another state, literally and figuratively. I haven’t lived in Amity since 1995. But when Griswold describes one resident, she exposes the essential divides that I remember.

[Jason] Clark bristled at environmentalists and reporters who assumed they understood how corporations were taking advantage of rural Americans. The idea that people who lived on the front lines of Frackistan were somehow being duped by the shadowy forces of industry made him chuckle in anger. […] And the problem wasn’t just the coastal elite, it was urban people everywhere. “People who live in Pittsburgh or Philadelphia are bottom-feeders who don’t want to know where their meat or their energy comes from,” he told me.

I went to high school with Jason Clark, and his words ring a deep bell for me—the mistrust of outsiders, the stubborn we-don’t-need-your-pity independence. But my life has carried me inexorably away from that viewpoint.

We’ve all become more aware of the United States’ cultural divides—the “fracturing” of Griswold’s title—in the last few years. Now that I live in this other world, I can hear both the toughness of Clark’s words and the blind spots behind them, too.

* * *

The first time I noticed a gas well near my mother’s house—around 2007—I was aghast. “How could someone soil their own nest like that?” I asked. All I could see at that moment was the despoiled hillside, the noise and light pollution, the risks to the groundwater: an industrial blight on a formerly beautiful farm.

I didn’t understand until later that the royalties a landowner can earn by signing a lease with a gas company were, for many southwestern Pennsylvanians, life-changing. My dad pointed out to me a number of big new barns being built in the cattle pastures and cornfields. People were catching a break from the economic straits they’d always labored under: working jobs in town to be able to hold on to family land, jobs whose limits were often defined by their own lack of education and the regional history of industrial decline. As I was growing up in Amity, the withdrawal and collapse of the steel and coal industries was one of the givens of life. Their absence was a presence. It was on everyone’s tongue; it was a master narrative about life and work and fortunes. It manifested in ruined corners of the landscape, in abandoned towns and buildings, in hollowed-out downtowns.

You might think that Pennsylvanians would know better than to invite another in this long line of extractive industries, which includes the oil boom-and-bust cycle of the late 1800s. But here, where the Rust Belt meets Appalachia, fracking has successfully insinuated itself by offering not only jobs—which coal and steel also did—but real wealth. And it has come down to individual landowners, sitting at tables across from gas company representatives, signing papers that can significantly lift their personal fortunes.

My dad has a story about running into someone he knew in the grocery store, who told him the gas-royalty checks arriving in his mailbox every month were “so big he didn’t know what to do with them.” There are plenty of more modest stories too, about people who could finally get health insurance or buy, like Jason Clark, better pigs for breeding stock. When the environmental health of an entire region comes down to many individual economic decisions, maybe it’s inevitable that the environment will lose.

That’s especially true because refusing to sign a lease does little or nothing to stop fracking. My dad signed, although the wellpad is actually on his neighbor’s land; had he not signed, he would simply have forgone the money to be made from a well that would be built regardless, bringing with it noise and health risks. Also, nothing would have stopped the operators from drilling horizontally to remove the gas from under his house.

Stacey Haney, too, signed a lease with Range. One farm at a time, one family at a time, fracking has conquered the land. Washington County was punctured by 209 new wells in 2017 alone, and pipelines to connect them now crisscross the hills under broad stripes of clear-cut land. One might argue that people could refuse to sign as a moral stance, a kind of boycott. But anyone making that argument—which, in essence, is a request that already poor people martyr themselves for the sake of the common good—would likely be viewed as an out-of-touch elitist, a privileged meddler.

* * *

Fracking is where loving Amity becomes akin to loving a self-destructive addict. It’s grieved me to come home and see this dark machinery dotting the landscape of my childhood, the ground itself shoved aside to make way. Not only through my dad’s windows but around the corners of little tar-and-chip roads, on hilltops and in bottomland, loom the incongruous gashes and bawling water trucks and lanky drill rigs. Well sites form a thicket on the map.

My first thought about Griswold, when I learned of the existence of her book, was a fairly standard Amity reaction, namely: “What does that carpetbagger know about my town?” But her relentless, measured narration helped me understand my own blind spots—that sadness over ruined views is a kind of class privilege, the outgrowth of a particular stance toward the land. Rather than working it, I’ve been used to looking at it.

In exactly the same way, it’s a privilege for me to be able to stand back from the culture and economy of my hometown and regard it from a distance. I didn’t know until I left, for example, what a thriving downtown looked like, or that postindustrial decay isn’t universal or inevitable. And I didn’t fully perceive (though I’d always keenly sensed) the local ambivalence toward education, a trait that surely has not helped the region navigate this latest corporate incursion.

Nonetheless, to concede that I couldn’t blame individual landowners for the blight of fracking felt to me like a dead end. If every person who signed a lease had sound personal reasons to do so, then every gas well is none of my business, and no local person can be held responsible for what’s happened to the locality.

In the end, a ruined landscape cannot be a solution. The common wealth of Pennsylvania consists of, and is embodied by, its land. Air and water—and aesthetics too, the joy one takes in the environs—are impossible to individually own. They are shared assets, and therefore shared responsibilities.

* * *

For years, even as Stacey Haney was suing Range, the corporation made nice with an annual donation of $100 to her children and other 4-H members. In this calculated gesture, Range role-played the part of good neighbor. And Stacey upheld her own, genuine idea of courtesy when she had her kids write thank-you notes for these gifts, to the company that was, meanwhile, poisoning their home.

It is a tragedy when the old values, based in agrarian stewardship and friendly relations, are made absurd by economic pressure.

Fracking may have lined some local pockets for a time, but history tells us the bust will come. And then Stacey Haney’s kids and all the other young people of Amity will inherit a place whose common wealth, and neighborliness, has been eroded that much more.

Griswold’s brilliant choice is to focus tightly on a small group of residents and let the details of their predicament speak for themselves. Thoroughly reported and tightly paced, “Amity and Prosperity” is an essential document of the region’s latest go-round with the riches underfoot.

Erika Howsare is a poet and journalist who lives in Virginia and blogs at erikahowsare.com. Her second book, “How Is Travel a Folded Form?,” was published in August by Saddle Road Press.

The Suspected Bomber’s Van Needs to Be Seen to Be Believed

After federal authorities on Friday arrested 56-year-old Cesar Sayoc in connection with the explosive devices that were sent to nearly a dozen public officials and critics of President Donald Trump over the past week, a Twitter user posted close-up photos of the suspect’s van, which is covered in photos of Trump, American flags, and bizarre right-wing paraphernalia.

The photos posted on Twitter show the same covered object on the back of the van that was seen in video footage after the suspect was arrested.

Here are the photos, via this tweet by Mark Lancia:

Authorities on Friday covered the van with a large blue tarp, but footage from after the vehicle was transported shows the images plastered on the windows:

Here’s the blue tarp falling off magabomber’s van and officers working to conceal the insanity stickers. pic.twitter.com/Lb6rnTc0OV

— doctor lexus catbro (@catbro69) October 26, 2018

Shortly after the suspect’s van appeared all over cable news, freelance journalist Lesley Abravanel posted a photo on Twitter showing what appears to be the same vehicle, which she said was parked outside of her husband’s office last November:

OMG. My husband just called and said “Remember that picture I texted you of that crazy Trump van that delivered lunch to my office? THAT WAS THE GUY!” This is the picture he sent me of the van parked at his office on November 1, 2017. #FloridaMan @FBI pic.twitter.com/18BimNzNhi

— Lesley Abravanel (@lesleyabravanel) October 26, 2018

Florida Man Detained in Sweeping Mail-Bomb Case

WASHINGTON — Federal authorities arrested a man in Florida on Friday in connection with the mail-bomb scare that widened to 12 suspicious packages, the Justice Department said.

Law enforcement officers were seen on television examining a white van, its windows covered with an assortment of stickers, in the city of Plantation. They covered the vehicle with a blue tarp.

The man was in his 50s, a law enforcement official said, but his name and any charges he might face were not immediately known.

Department spokeswoman Sarah Isgur Flores said authorities planned to announce more information at a press conference.

The development came amid a coast-to-coast manhunt for the person responsible for a series of explosive devices addressed to Democrats including former President Barack Obama, former Vice President Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton.

Law enforcement officials said they had intercepted a dozen packages in states across the country. None had exploded, and it wasn’t immediately clear if they were intended to cause physical harm or simply sow fear and anxiety.

Earlier Friday, authorities said suspicious packages addressed to New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker and former National Intelligence Director James Clapper — both similar to those containing pipe bombs sent to other prominent critics of President Donald Trump— had been intercepted.

The discoveries — making 12 so far — further spurred a coast-to-coast investigation, as officials scrambled to locate a culprit and possible motive amid questions about whether new packages were being sent or simply surfacing after a period in mail system.

The devices have targeted well-known Democrats including former President Barack Obama, former Vice President Joe Biden, Hillary Clinton and former Attorney General Eric Holder.

The FBI said the package to Booker was intercepted in Florida. The one discovered at a Manhattan postal facility was addressed to Clapper at CNN’s address. An earlier package had been sent to former Obama CIA Director John Brennan via CNN in New York.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions said Friday the Justice Department was dedicating every available resource to the investigation “and I can tell you this: We will find the person or persons responsible. We will bring them to justice.”

Trump, on the other hand, complained that “this ‘bomb’ stuff” was taking attention away from the upcoming election and said critics were wrongly blaming him and his heated rhetoric.

Investigators were analyzing the innards of the crude devices to reveal whether they were intended to detonate or simply sow fear just before Election Day.

Law enforcement officials told The Associated Press that the devices, containing timers and batteries, were not rigged to explode upon opening. But they were uncertain whether the devices were poorly designed or never intended to cause physical harm.

Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, in an interview Thursday with Fox News Channel, acknowledged that some of packages originated in Florida. One official told AP that investigators are homing in on a postal facility in Opa-locka, Florida, where they believe some packages originated.

The package addressed to Booker was found during an oversight search of that facility, according to a law enforcement official.

The officials spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the ongoing investigation by name

Most of those targeted were past or present U.S. officials, but one was sent to actor Robert De Niro and billionaire George Soros. The bombs have been sent across the country – from New York, Delaware and Washington, D.C., to Florida and California, where Rep. Maxine Waters was targeted. They bore the return address of Florida Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, the former chairwoman of the Democratic National Committee.

The common thread among the bomb targets was obvious: their critical words for Trump and his frequent, harsher criticism in return.

Trump claimed Friday he was being blamed for the mail bombs, complaining in a tweet sent before dawn: “Funny how lowly rated CNN, and others, can criticize me at will, even blaming me for the current spate of Bombs and ridiculously comparing this to September 11th and the Oklahoma City bombing, yet when I criticize them they go wild and scream, ‘it’s just not Presidential!’”

The package to Clapper was addressed to him at CNN’s Midtown Manhattan address. Clapper, a frequent Trump critic, told CNN that he was not surprised he was targeted and that he considered the actions “definitely domestic terrorism.”

Jeff Zucker, the president of CNN Worldwide, said in a note to staff that all mail to CNN domestic offices was being screened at off-site facilities. He said there was no imminent danger to the Time Warner Center, where CNN’s New York office is located.

At a press conference Thursday, officials in New York would not discuss possible motives or details on how the packages found their way into the postal system. Nor would they say why the packages hadn’t detonated, but they stressed they were still treating them as “live devices.”

The devices were packaged in manila envelopes and carried U.S. postage stamps. They were being examined by technicians at the FBI’s forensic lab in Quantico, Virginia.

The packages stoked nationwide tensions ahead of the Nov. 6 election to determine control of Congress — a campaign both major political parties have described in near-apocalyptic terms. Politicians from both parties used the threats to decry a toxic political climate and lay blame.

Trump, in a tweet Thursday, blamed the “Mainstream Media” for the anger in society. Brennan responded, tweeting that Trump should “Stop blaming others. Look in the mirror.”

The bombs are about 6 inches (15 centimeters) long and packed with powder and broken glass, according to a law enforcement official who viewed X-ray images. The official said the devices were made from PVC pipe and covered with black tape.

The first bomb discovered was delivered Monday to the suburban New York compound of Soros, a major contributor to Democratic causes. Soros has called Trump’s presidency “dangerous.”

Child Brides in Lesotho Lose Their Youth and Their Future

Truthdig is proud to present this article as part of its Global Voices: Truthdig Women Reporting, a series from a network of female correspondents around the world who are dedicated to pursuing truth within their countries and elsewhere.

From Latin America to the Middle East, early marriage is a global specter that robs girls of their futures. Instead of attending school and improving their chances in life, child brides face terrifying realities including domestic violence, dangerous early pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases.

In Lesotho, a mountainous kingdom encircled by South Africa, the number of early marriages is alarming, with nearly one out of five girls marrying before the age of 18. The situation is particularly dire because Lesotho suffers from a devastating HIV epidemic.

In recent years, Lesotho human rights advocates have rallied to fight child marriage, but the powerful forces of tradition, poverty and gender inequality still stand in the way of progress.

Makabelo Lebate, 21, bursts into tears as she describes her life as a teenage bride.

“I was 15 years old and still a virgin when I was married off by my aunt to a man who was 32 years older than me,” she says. “I tried to escape, but I was caught and … locked in the house for three weeks. I was raped almost every day by my husband because I wouldn’t give my consent. [Finally] I couldn’t resist anymore, and I settled down as a wife.”

Lebate was 16 when she became pregnant with the first of her three children. “When I went for an HIV test, the results came back positive,” she says. “I told my mother-in-law, as I was afraid of my husband, and I discovered that my husband was already on HIV treatment.”

Lebate and her husband were uneducated. They lived in poverty in the rural district of Mokhotlong, where it was hard to find work. The nearest health care center was far away, and Lebate often had to go without medication to treat her HIV, which led to further health complications.

Child brides are likely to be exposed to sexually transmitted diseases including HIV/AIDS because these girls lack power to negotiate sexual terms, says Dr. Molotsi Monyamane, Lesotho’s former minister of health and an expert on sexual and reproductive rights.

Early marriages threaten girls’ health and well-being in other ways as well, Dr. Monyamane says. Early pregnancy often follows on the heels of a marriage, even if a girl isn’t physically or mentally ready to bear children. In developing countries, girls between the ages of 15 and 19 are twice as likely as older women to die from complications of pregnancy and childbirth.

Underlying Poverty

Several factors—including poverty—contribute to early marriage in Lesotho and other African countries.

“Parents … reduce family expenses by ensuring they have one less person to feed, clothe and educate,” according to the website of Girls Not Brides, a global partnership of organizations committed to ending child marriage.

Sometimes the girls’ families receive money as part of the marriage arrangement. Lebate’s aunt agreed to her niece’s marriage because she was promised a dowry in the form of cows, which would help ease her family’s desperate economic situation. (Lebate’s parents had died years earlier, so her aunt wielded authority.)

Matselane Linkeng, now 24, was married at 16.

Matselane Linkeng, 24, married early as a means to support her younger siblings. Her mother died when Linkeng was 12 years old, and the girl became the sole bread winner. When she was 16, she met and married a man who was old enough to be her father. Linkeng was lucky as a young bride: The couple were happily married, and her husband helped provide for her siblings.

But two years later, her luck ran out.

“Things changed when I was 18 and my husband died,” Linkeng says. “My in-laws kicked me out of the house and took everything that belonged to our joint estate. I didn’t have money to institute legal proceedings and ended up leaving with my son, who was 2 years old.”

In Lesotho, women whose husbands die are often driven from their homes by their in-laws, who may claim the couple wasn’t legally married. Many widows fight the eviction in court, but Linkeng couldn’t afford the services of a lawyer and didn’t know she could have asked for legal aid services.

Tradition and Gender Bias

Entrenched cultural mores also drive early marriages. Forced elopement is a traditional practice in which a group of men organize and help one of their members take a girl as his wife, without that girl’s previous knowledge or consent.

Malerato Thibella, now 23, lived in the Thaba-Tseka district, where child brides are common. Thibella was “eloped” by a man in a neighbouring village when she was a 16-year-old student. He took her from her home, and when they arrived in the remote area where he lived, she learned she was a second wife. Polygamy is a traditional practice that is legal in Lesotho.

She later discovered her parents knew about the arrangement. “I couldn’t believe my ears when I was told that my own father … told this man I would be coming [home] for the school holidays,” Thibella says, with tears running down her cheeks. She rarely visited her parents because her school was far away, so her father’s tipoff set the stage for the abduction.

Because she couldn’t come to terms with the fact that she had married a stranger and, worse, that her husband abused her physically and emotionally, she ran away to live with an aunt in Maseru, the capital city.

Malerato Thibella, now 23, escaped from an early marriage.

Along with poverty and cultural factors, inherent gender inequality leads to early marriages. In countries such as Lesotho, families often don’t value girls and consider them to be a burden. “Marrying [off] your daughter at a young age can be viewed as a way to [transfer this burden] to her husband’s family,” according to the Girls Not Brides website.

The Fight Against Early Marriage

Human rights supporters in Lesotho have opposed child marriage for decades and recently stepped up efforts to ban the practice. In April of this year, Princess Senate Mohato Seeiso, 17—a daughter of the king and queen of Lesotho—launched an awareness campaign at an event attended by thousands of teenagers.

The princess urged lawmakers and parents to help change underlying social norms that perpetuate early marriage. ‘‘I am making a clarion call to everyone here that [these] are children, not brides,” she said. “Child marriage undermines the rights of young girls in different spheres of life. They … suffer physical, emotional and mental scars.”

Last year, Lesotho joined an African Union campaign to end child marriage. The African Union—a continent-wide organization that addresses social, economic and political issues—developed the campaign to promote policy change on early marriage, raise awareness of consequences and build a grassroots movement that includes lawyers, judges, teachers, health and social workers and religious and traditional leaders.

Mobilizing these leaders is critical to establishing lasting social change, according to Moeketsi Sello, head of a community in the remote district of Mohale’s Hoek. Sello says traditional leaders are considered champions of local culture, so educating them about the consequences of early marriage leads to educating the public.

Mohau Maapesa, a Lesotho attorney and advocate for women’s rights, says practical strategies are essential to change traditional thinking. These include holding educational sessions for parents and community leaders, as well as distributing handouts written in local languages.

Initiatives also work to empower girls by educating them about issues such as sexual and reproductive health. The information is especially important among the poorest and most marginalized teenagers in rural areas where child marriage is prevalent. Maapesa says youth groups are an effective way to transmit this vital knowledge.

Aftermath for Child Brides

Early marriage not only presents physical and emotional threats to teenage girls, but it also affects the rest of their lives. Child brides routinely drop out of school, which usually traps them in financial straits whether or not they stay in the marriage.

Makabelo Lebate, 21, with two of her three children.

After years of being physically abused by her husband, Lebate left home with her three children. She moved to Maseru to look for a job, and she now works there as a maid. Her salary is small, but she says she’s able to put bread on the table. She is managing her HIV thanks to regular medication from a nearby clinic.

Linkeng is also employed as a maid in Maseru, and she says she and her son live in poverty because she earns so little.

Thibella, who doesn’t have children, was one of the fortunate ones when it came to education. With her aunt’s help, she graduated from Limkowing University in Maseru with a bachelor’s degree in education.

Thibella works for organizations that promote the rights of girls and women, although she’s currently between jobs. She is vocal about social issues such as abortion, gender equality and early marriage.

Lebate strongly supports efforts to protect girls from the fate she endured—and to empower them through knowledge. “I lived my whole childhood like a prisoner without rights, and I [urge people] to rescue these innocent souls,” she says. “Educating girls is one of the most powerful tools to prevent child marriage.”

What It Ultimately Takes to Bring Down a Confederate Monument

Last week, following a day of testimony, a North Carolina judge found UNC-Chapel Hill graduate student and anti-racist activist Maya Little guilty of a misdemeanor charge of defacing a public monument—the Confederate statue known as Silent Sam. The court stopped short of any further punishment, opting instead to waive all associated court fees and restitution. Little had been facing up to 60 days in jail, an absurd and unjust sentencing possibility for multiple reasons, the most salient being the disproportionate ratio of the punishment when stacked up against what North Carolina labels a crime. On October 25 and 26, Little will head into two days of hearings presided over by UNC-Chapel Hill’s Honor Court, which in June charged her with violating the university’s honor code. Once again, Little will have to endure a trial for an act that others before have undertaken without punishment.

On April 30, Little was arrested by UNC police after she poured a mixture of red paint and her own blood on Silent Sam. She is not, by a longshot, the first student to douse the monument in paint; accounts of Silent Sam being painted to celebrate basketball victories and sports rivalries date back to the 1950s. Yet there’s not a single record of arrests made or other punitive measures having been taken in those examples. Little’s case seems to have been singled out for punishment specifically because of the substantiveness of her actions. The message UNC-Chapel Hill appears to be sending is that frivolous vandalisms in the name of sports victories are okay, while substantive statements about racism and UNC complicity are not.

Silent Sam, erected in 1913, was one of many tributes to the Confederacy put up by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the group that has done more than any other to install Confederate monuments and keep them standing. At the dedication ceremony, industrialist Julian Carr boasted that he had once “horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds” near the statue site for not showing proper deference to a white woman, and gave a shout-out to the Ku Klux Klan for terrorizing blacks during Reconstruction, thus “sav[ing] the Anglo Saxon race in the South.” For 105 years after that speech, Silent Sam stood at the main entrance to the UNC-Chapel Hill campus, sending out a message about the university’s refusal to take a stand against racism—a message telegraphed to the world, including the school’s black students.

For more than 50 years, students have been protesting the statue’s glorification of a treasonous country that fought to ensure black enslavement in perpetuity. In 1965, the UNC campus newspaper published a student letter that noted “[t]he primary purpose of [Silent Sam] was to associate a fictitious ‘honor’ with the darkest blot on American history—the fight of southern racists to keep the Negro peoples in a position of debased subservience” and suggested the administration “take up the case of removing from the campus that shameful commemoration of a disgraceful episode.” Days after the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., black students used defacement to protest Silent Sam’s racist presence, and they rallied at the statue after the 1970 murder of a young black man named James Cates by a white motorcycle gang. In the years since the 2015 racist massacre of nine black parishioners in a Charleston church, anti-racist activists have jumped through every legal hoop to bring the visible emblem of white terror down. Repeatedly, neo-Confederates and various racist groups have come to campus to rally in defense of Silent Sam, an open acknowledgement of the statue as a symbol of white supremacy and power. Again and again, their presence has proved that Silent Sam is a threat to public safety, particularly against students of color.

Despite all that, UNC’s administration never made a good-faith move to remove the statue. Instead, the university targeted anti-racist activists on campus in various troubling ways. Last year, the News & Observer noted that “campus police officials assigned a plainclothes officer to spy on students engaged in a peaceful vigil calling for removal of the Silent Sam statue. The officer didn’t merely watch the students from a distance. He infiltrated the group, lied about his political interests and identity, and cultivated students’ trust.” In July of this year, leaked emails revealed that a Board of Trustees member had labeled student activists “criminals” and “entitled wimps” and suggested they should be arrested. If inactivity defined the response of UNC officials, North Carolina’s Republican lawmakers took the opposite route. In 2015, as Confederate symbols were being challenged after the Charleston massacre—and weeks after the name was wiped from a UNC-Chapel Hill dorm—the GOP-led state legislature quickly passed a heritage law designed to keep Confederate monuments from being removed. Since then, as outcry against Silent Sam gained steam, they have twice reinforced the legislation.

With frustrations boiling over and legal options seemingly exhausted, anti-racist activists took down Silent Sam on August 20. It took only about an hour for the school’s Chancellor, Carol Folt, to decry their actions as “unlawful and dangerous.” Approximately 12 hours later, UNC President Margaret Spellings and Board of Governors Chair Harry Smith put out a joint statement calling the event “unacceptable, dangerous, and incomprehensible” and ominously warning that “mob rule and the intentional destruction of public property will not be tolerated.” On Twitter, UNC Board of Governors member Thom Goolsby rushed to brand the protesters as “criminals,” and issued the vague threat that those who “destroyed state property” would be “held accountable.” North Carolina’s GOP House Speaker Tim Moore lamented “the destruction of property” along with “mob rule and acts of violence”; former Governor Pat McCrory compared the protesters to “Nazis of the 1930s”; and GOP state Representative Larry Pittman breathlessly argued that the statue’s removal by “mob rule… could lead to an actual civil war.”

The outpouring of concern from UNC officials and conservative lawmakers about violent threats to student safety related to Silent Sam was most notable for its suddenness, considering that both parties had done nothing to address the potential for violence Silent Sam’s presence had created dating back decades. Nearly two months to the day after Silent Sam’s toppling, a North Carolina judge in another monument-related case took UNC to task for the danger its inactivity had posed.

“I ask the leadership of the university if your goal is to teach a diverse community of students, what are you doing to assure that all students feel emotionally and physically safe?” queried Orange County District Court Judge Beverly Scarlett. “What is the difference in the Silent Sam statue and a statue of Adolf Hitler? Is human suffering not a common denominator?”

It’s a valid question. UNC had chosen to ignore the violence and terror against black folks that Silent Sam was erected to represent; vicious racists have been drawn to the monument, which they recognized as a symbol of white power and supremacy. That violence was the issue Little’s protest had specifically aimed to address. And for all of those reasons, her protest should be considered a valid and courageous response to an unjust law.

I spoke with Little just ahead of her court hearing about Silent Sam’s history, the legacy of racism surrounding the statue, UNC’s inaction on the issue and the hidden history of resistance to white supremacy.

Kali Holloway: Can you talk about when you first became aware of Silent Sam and what he stood for?

Maya Little: It was before I matriculated, and I was walking on campus and I saw Silent Sam, which is the most prominent monument on campus. It was one of the first Confederate monuments I had ever seen, and I was disgusted. I couldn’t imagine that this smirking, armed Confederate soldier [was] not only on campus but, as I later found out, facing a historically black neighborhood. My first impulse was [to ask] what have people been doing about this? What I’ve come to find out is that there has been so much movement around Silent Sam for the last 50 years and that’s still hidden. There’s nothing around Silent Sam that commemorates students who marched there in 1973, after James Cates’ killers were acquitted. Nothing of the students who marched there after Rodney King was beaten in Los Angeles. Nothing of the movement to get rid of the statue over the last 50 years. One thing about discovering the statue was also discovering the history of resistance around it.

KH: Did you immediately decide to engage in activism to take the monument down?

ML: No. I didn’t know how to respond aside from doing research because, again, we’re disconnected from these legacies of resistance. The first time you see the statue, you feel isolated. You feel like you are looking up at this statue of a slaveholder and no one cares—no one’s doing anything about it. What helped me get involved on the first day of protests last year was seeing so many people from the community, and students and faculty, marching on that statue and demanding it be taken down—and so much community support against white supremacy. The University made clear that day what side they were on when they had riot police guarding the statue and they put up barricades around it. They refused, despite the so many pleas to remove the statue, to do anything about it.

KH: Can you talk about some of the COINTELPRO stuff that’s happened with UNC?

ML: There’s a legacy of surveillance, police harassment and abuse of activists at UNC, especially black student activists. Black Student Movement was a group that was founded in the 1960s. It was surveilled by the COINTELPRO program, and the university and campus police were complicit in and aided that surveillance. They wiretapped Black Student Movement’s offices. That only was found out about in the 1980s.

Fast-forward and UNC is still spying on students, still harassing and abusing students, still using tactics that have been declared illegal, unlawful, intimidating, racist. UNC is also engaging in very openly, physically silencing students. Over the last few protests on McCorkle Place [where the Silent Sam pedestal remains], I have seen and personally been pepper sprayed by an unhinged Greensboro police officer. I have been hit and punched in the ribs and on my arms, with bicycles by UNC police, by actual police.

Now that the statue is gone, the university is trying to silence everyone who stood against what the statue stood for. What I’m afraid of is, seeing that it’s already extending into physical harm, where else can it get to? That’s what I fear. When I see police officers pointblank pepper spray a student in the face for allegedly giving them the finger, I think, what if that was a gun in that police officer’s hand?

KH: I want to go back just a little bit to talk about how you had the idea to mix your blood with paint for the protest action.

ML: What I see, and what so many other black students and faculty see when they see Silent Sam, and those buildings named after slave owners—people who murdered black politicians fighting for equality—is black blood. We see an attempt to sanitize and whitewash that.

Black blood which he’s already covered in. Black blood which he was built on. Black blood, which the people who dedicated him caused to flow for their ideals, which were Jim Crow, racism, lynching, brutality against black people. As I correctly predicted, the University washed my blood off that statue immediately. For 105 years, the university didn’t act on a monument dedicated by a man who bragged about whipping a black woman, but it can act within seconds to take my blood off the statue to make sure that the statue remains whitewashed. That it remains in McCorkle Place rather than exposing the brutality Sam stands for, which [includes] violence towards black community members at UNC, the enforcement of a color line in Chapel Hill, the murder of James Cates, the continued exploitation of black athletes, and a majority black and brown workforce who are not paid a living wage.

KH: I know that you’ve received threats for your protests.

ML: Yeah, I’ve gotten a lot of death threats online from people who are local, who live in Chapel Hill and Carrboro. People who very openly attach their name and where they live. I think that’s because these are the people that support Silent Sam, and they know what Silent Sam stands for too. The fact that they’re threatening to lynch me, to hang me over the tree that Silent Sam stood under is no coincidence.

KH: This was not the first time that Silent Sam had been painted, but the motivation for why it was painted has previously been connected to sports. You were making a very different statement, and the difference in the way that the university and police reacted to that is astounding. Can you talk about that disparity?

ML: The statue’s been painted multiple times, and it’s been painted in graffiti to expose racism, and it’s also been painted for sport. In those cases when it’s been painted Duke blue or Carolina blue or NC State red, there’s been no punishment, and it’s not been treated seriously. That’s because painting Silent Sam to expose racism—to talk about the history of the Confederacy and the history of white supremacy on campus—is not allowed. It’s an act unbecoming of a UNC affiliate, apparently. But setting fires on streets after a championship game is apparently a UNC pastime, is acceptable and okay.

KH: What’s the thing you hope your protest has most driven home?

ML: The statue preys on black lives; it’s not here to memorialize this idea of boys who served in the Confederate army. Let’s talk about the history of North Carolina.

Written on the statue, it says, “Dedicated to the men who answered the call of duty.” The most sublime word is “duty.” Why do we have a monument on campus telling young people to drop their books and to go into war? Even beyond white supremacy, that is an unacceptable monument.

Let’s also talk about the men at UNC who were fighting for the Confederacy. These were not poor farm boys—there’s a whole history in North Carolina of people deserting and facing being hung by the Confederate army for refusing to fight. The men from UNC who were fighting were officers, and they had a vested interest in slaveholding. The people who erected [Silent Sam] were their descendants [and] they had the same vested interest in Jim Crow and preventing black people from voting and owning property and having any rights. That’s who Silent Sam memorialized.

This article was produced by Make It Right, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

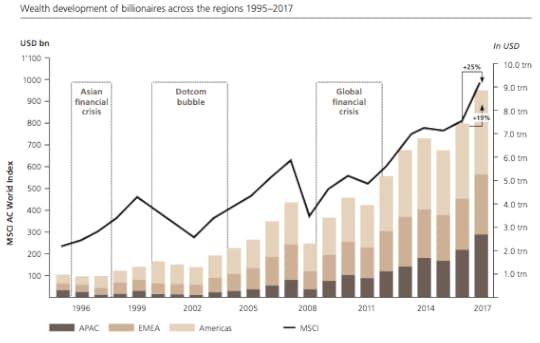

Billionaires Made History in 2017, for All the Wrong Reasons

During a year in which so much of the world faced deep poverty, the corrosive effects of austerity, and extreme weather caused by the worsening human-caused climate crisis—from devastating hurricanes to deadly wildfires and floods—one class of individuals raked in more money in 2017 than any other year in recorded history: the world’s billionaires.

According to the Swiss bank UBS’s fifth annual billionaires report published on Friday, billionaires across the globe increased their wealth by $1.4 trillion last year—an astonishing 20 percent—bringing their combined wealth to an astonishing $8.9 trillion.

“The past 30 years have seen far greater wealth creation than the Gilded Age,” the UBS report notes. “That period bred generations of families in the U.S. and Europe who went on to influence business, banking, politics, philanthropy, and the arts for more than 100 years.”

UBS estimates that the world now has a total of 2,158 billionaires, with 179 billionaires created last year. The United States alone is home to 585 billionaires—the most in the world—up from 563 in 2017.

Meanwhile, according to a June report by U.N. Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights Philip Alston, 18.5 million Americans live in extreme poverty and “5.3 million live in Third World conditions of absolute poverty.”

World’s greedy billionaires became 20% richer in 2017 while the rest of the world burned https://t.co/yEW0wHF2bx

— Domenicodimaro97 (@Domenicodmaro97) October 26, 2018

A significant percentage of the “newly created” billionaires are hardly the self-made men—and they are overwhelmingly men—of popular lore. According to UBS, 40 of the 179 new billionaires created last year inherited their wealth—a trend that has driven an explosion of wealth inequality over the past several decades.

According to UBS, this trend will continue to accelerate over the next 20 years, given that there are currently 701 billionaires over the age of 70.

“A major wealth transition has begun. Over the past five years (2012–2017), the sum passed by deceased billionaires to beneficiaries has grown by an average of 17 percent each year,” the UBS report concludes. “Over the next two decades we expect a wealth transition of $3.4 trillion worldwide—almost 40 percent of current total billionaire wealth.”

October 25, 2018

John Roberts Is the Supreme Court’s New Swing Justice

Now that Brett Kavanaugh has been confirmed as the 114th justice of the Supreme Court, Chief Justice John Roberts has stepped into the role vacated by the retired Anthony Kennedy as the court’s “swing” member.

Think about that for a moment, and what it augurs for the future of American law.

At a macro level, it means that the conservative legal movement, headed by think tanks and organizations like The Federalist Society and The Heritage Foundation, has finally achieved the solid 5-4 majority it has craved for decades.

More concretely, it means that a host of liberal precedents crafted by the high court since the New Deal are in jeopardy of being overturned or substantially weakened. Among the most vulnerable are the court’s landmark decisions in the areas of abortion, affirmative action, workers’ rights and employment discrimination, antitrust, and environmental protection.

Even before Kavanaugh’s appointment, the Roberts court was hardly liberal, despite occasional progressive decisions handed down on such issues as same-sex marriage, with Kennedy often casting the tie-breaking votes. Indeed, according to several in-depth studies, under Roberts’ leadership the high tribunal has been the most pro-business Supreme Court since the end of World War II.

Academic researchers and law professors who study judicial ideology use a variety of statistical tools to chart where justices fall on the political spectrum. One of the better-known models, developed by University of Michigan professors Andrew Martin and Kevin Quinn, places justices on an ideological continuum, assigning scores to each, based on their voting records and the political orientation of the litigants in the cases they decide.

The Martin-Quinn scores for Roberts place him in the ideological middle of the current court, slightly to the right of where Kennedy had been, but clearly to the right of center. On the court’s far right are Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas, the panel’s most conservative member. Brett Kavanaugh, based on his 12-year stint as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, is ranked just to the left of Thomas.

In his 2005 confirmation hearing, Roberts famously declared, by way of an analogy to the role of baseball umpires, that the “job” of judges “is to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.” His decisions, however, tell a different—and far more activist—story.

Roberts was the author of one of the most egregious right-wing rulings of the last 50 years—the 5-4 majority opinion in Shelby County v. Holder (2103). The decision invalidated a key provision of the Voting Rights Act that required certain voting districts, mostly in the South, to obtain “pre-clearance,” or advance approval, from the Justice Department or a federal district court in Washington, D.C., before implementing any changes in voting procedures. With the pre-clearance process effectively gutted as a result of the decision, voter suppression techniques in GOP-controlled states have proliferated at a rate not seen since the Jim Crow era.

The Shelby County majority opinion is breathtaking, not only for the scope of its judicial activism—Congress had reauthorized the Voting Rights Act for an additional 25 years in 2006, with the Senate expressing its endorsement by a vote of 98 to 0—but for its distortion of the country’s racist past and its racist present.

At the heart of Roberts’ opinion is the view that racism in America has effectively been extinguished. When the Voting Rights Act was enacted in 1965, Roberts wrote in Shelby County v. Holder decision:

[T]he States could be divided into two groups: those with a recent history of voting tests and low voter registration and turnout, and those without those characteristics. Congress based its [pre-clearance] coverage formula on that distinction. Today the nation is no longer divided along those lines, yet the Voting Rights Act continues to treat it as if it were.

Last term, Roberts turned another blind eye to bigotry, writing the 5-4 majority opinion in Trump v. Hawaii, which upheld the president’s Muslim travel ban.

When not drafting majority opinions himself, Roberts has voted time and again in concert with his conservative brethren in such high-profile 5-4 decisions as Massachusetts v. EPA (2007) on the Clean Air Act; District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) on the Second Amendment; Citizens United v. FEC (2010) on campaign finance; Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014) on “religious liberty”; Hall v. Florida (2014) on the constitutionality of executing an intellectually disabled person; Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016) on abortion; Fisher v. University of Texas (2016) on affirmative action; and Janus v. AFSCME (2018) on public employee unions.

To be sure, there is another—but much shorter—side of the ledger involving cases in which Roberts has aligned with the court’s liberals. In 2012, he wrote the 5-4 majority opinion that upheld the “individual mandate” provision of the Affordable Care Act in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius. In the same opinion, however, he ruled that the act’s mandatory Medicaid expansion sections were unconstitutional.

To his credit, Roberts has also written majority opinions upholding the Fourth Amendment privacy interests of cellphone owners in Riley v. California (2014) and Carpenter v. U.S. (2018).

In a speech delivered at the University of Minnesota Law School on Oct. 16, Roberts sought to defuse the enmity and rancor caused by Kavanaugh’s confirmation, stressing the need for judicial independence.

Channeling Alexander Hamilton and Federalist Paper No. 78, Roberts said that the courts “must be very different” from the “political branches” of government. The courts, he insisted, “do not speak for the people. … We speak for the Constitution. Our role is very clear: We are to interpret the Constitution and the laws of the United States and ensure that the political branches act within them.”

I have little doubt that Roberts is genuinely concerned with the legitimacy of the Supreme Court and the court’s interest in appearing nonpartisan. Unfortunately, that interest appears to be narrow, abstract and formalistic.

In matters of substance in cases that affect the vital rights and interests of real people, particularly minorities and those without institutional power, Roberts has shown himself to be a corporate partisan. That he now occupies the ideological center of the highest court in the land should be a danger signal akin to a fire alarm for everyone concerned with justice and equality under the law.

President Trump Is the Greatest Threat to National Security

President Donald Trump is a threat to national security. His lies rev people up, inspiring hate. A slew of bombs have been discovered this week, targeting people and organizations Trump regularly vilifies: the Obamas, the Clintons, Congressmember Maxine Waters, CNN, ex-CIA chief John Brennan, former Attorney General Eric Holder and billionaire liberal philanthropist George Soros. While Trump fabricates national security concerns to foment fear, he ignores genuine threats.

Take the migrant caravan, for example. At a Houston rally on Sunday, Trump called it “an assault on our country.” Thousands of people making their way from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador are fleeing violence, poverty and desperation, seeking refuge and asylum in the United States and Mexico. In a tweet on Monday, Trump claimed “Criminals and unknown Middle Easterners are mixed in.” When challenged by a reporter for evidence, he flippantly replied, “There’s no proof of anything.”

A real threat that knows no borders is climate change. Hurricane Michael roared across the warming waters of the Gulf of Mexico and tore into the Florida Panhandle two weeks ago. The town of Mexico Beach was practically wiped off the map.

Fifteen miles farther west along the coast is Tyndall Air Force Base, home of a fleet of 55 F-22 stealth fighters. Before Hurricane Michael leveled the base, at least 33 of these jets were flown to safety. But as Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Dave Philipps reported, at least 17 of the planes, costing $339 million each, were likely left behind and possibly destroyed. Climate scientists point out that while no individual storm can be blamed on climate change, global warming increases their frequency and intensity. Hurricane Michael was the first recorded Category 4 hurricane to hit the Florida Panhandle, and was among the top three strongest hurricanes ever to hit the U.S. While Pentagon reports identify climate change as a major threat to national security in the 21st century, Trump calls it a hoax perpetrated by China to hurt the U.S. economy.

“To abandon facts is to abandon freedom,” writes Yale historian Timothy Snyder in his book “On Tyranny.” In the past few weeks, nothing illustrated this better than the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, Washington Post columnist and critic of the Saudi monarchy. On Oct. 2, Khashoggi walked into the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul and never came out. The Saudi government lied, saying he had left soon after. Reports almost immediately surfaced that Saudi Arabia had dispatched a 15-man “kill team,” which tortured, killed and dismembered Khashoggi in the consulate. Rather than denounce the murder immediately, Trump declared he would await Saudi Arabia’s investigation of itself, but would not cut record weapons sales to the kingdom. Saudi Arabia is waging a war on Yemen, and its relentless, U.S.-backed bombing has driven at least half of the Yemeni population to the brink of famine. The United Nations has declared Yemen to be the greatest humanitarian catastrophe on the planet today.

In the midst of the Khashoggi horror, President Trump held a rally in Montana praising a congressmember who pleaded guilty to criminally assaulting a reporter. At the campaign event, Trump hailed Congressmember Greg Gianforte, saying, “Any guy that can do a body slam, he’s my kind of … guy.” During his 2016 campaign, Gianforte body-slammed Guardian reporter Ben Jacobs.

To the shock of many, at another rally this week, Trump officially declared himself a nationalist — a label long associated with white supremacy and Nazism. “You know, they have a word — it’s sort of became old-fashioned — it’s called a nationalist. And I say, really, we’re not supposed to use that word. You know what I am? I’m a nationalist, OK? I’m a nationalist. Nationalist.” Desperate for Republicans to maintain their control of Congress, Trump continues to unleash the dark, divisive and destructive forces of racism.

All of this has taken place in the month of October. Add one more dangerous move by Trump, just this week: On Saturday, he announced he is pulling the United States out of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, signed by President Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in 1987. The INF banned all nuclear and non-nuclear missiles with short and medium ranges. Many fear this could stoke a new arms race with Russia, further destabilizing the world.

As Trump campaigns around the country, he gins up fears of foreign enemies attacking the United States. But he has shown again and again, through his words and deeds, that the greatest threat to U.S. national security is Trump himself.

Amy Goodman is the host of “Democracy Now!,” a daily international TV/radio news hour airing on more than 1,400 stations. She is the co-author, with Denis Moynihan and David Goodman, of the New York Times best-seller “Democracy Now!: 20 Years Covering the Movements Changing America.”

(c) 2018 Amy Goodman and Denis Moynihan

Distributed by King Features Syndicate

Super Typhoon Devastates U.S. Territory in Pacific

HONOLULU—Residents of the Northern Mariana Islands braced Friday for months without electricity or running water after the strongest storm to hit any part of the United States this year devastated the U.S. territory, killing one person, officials said.

Even after Super Typhoon Yutu had moved away from the Pacific islands, emergency management officials warned residents to stay indoors because downed power lines blocked roadways and winds were still strong enough to make driving dangerous.

A 44-year-old woman taking shelter in an abandoned building died when it collapsed in the storm, a post on the governor’s office Facebook page said. Officials couldn’t immediately be reached for additional details.

The territory will need significant help to recover from the storm that injured several people, said Gregorio Kilili Camacho Sablan, the territory’s delegate to Congress. He said Thursday that there were reports of injuries and that people were waiting to be treated at a hospital on the territory’s largest and most populated island, Saipan.

He could not provide further details or official estimates of casualties.

“There’s a lot of damage and destruction,” Sablan said in a telephone interview with The Associated Press from Saipan. “It’s like a small war just passed through.”

The islands’ emergency management agency was “deploying resources to clear our roadways so first responders can begin assisting residents who have lost their homes and for those who need transport to seek medical attention or transportation to the nearest shelter,” spokeswoman Nadine Deleon Guerrero said in a statement.

Sablan said has not been able to reach officials on the islands of Tinian and Rota because phones and power are out. “It’s going to take weeks probably to get electricity back to everybody,” he said.

The two islands will be unrecognizable, said Brandon Aydlett, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service. The agency received reports that catastrophic winds ripped roofs from homes and blew out windows.

“Any debris becomes shrapnel and deadly,” he said.

The electricity on Saipan about 3,800 miles (6,115 kilometers) west of Hawaii went out at 4 p.m. Wednesday, resident Glen Hunter said.

Maximum sustained winds of 180 mph (290 kph) were recorded around the eye of the storm, which passed over Tinian and Saipan early Thursday local time, the weather service said.

“At its peak, it felt like many trains running constant,” Hunter wrote in a Facebook message. “At its peak, the wind was constant and the sound horrifying.”

It was still dark when Hunter peeked outside and saw his neighbor’s house, made of wood and tin, completely gone. A palm tree was uprooted.

Hunter, 45, has lived on Saipan since childhood and is accustomed to strong storms. “We are in typhoon alley,” he wrote, adding that the storm is the worst he has experienced.

He said he doesn’t expect getting back power for months, recalling how it took four months to restore electricity after Typhoon Soudelor in 2015.

The roof flew off the second floor of Del Benson’s Saipan home.

“We didn’t sleep much,” he wrote in a Facebook message. “I went upstairs and the skylight blew out. Then the roof started to go. We got the kids downstairs.”

Sablan said colleagues in Congress have reached out to offer help and he expects a presidential disaster declaration to free up resources for storm relief.

Recovery efforts on Saipan and Tinian will be slow, said Aydlett of the weather service.

“This is the worst-case scenario. This is why the building codes in the Marianas are so tough,” he said. “This is going to be the storm which sets the scale for which future storms are compared to.”

Dean Sensui, vice chairman for Hawaii on the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, was in Saipan for a council meeting. He hunkered down in his hotel room, where guests were told to remain indoors because winds were still strong Thursday morning.

“From around midnight the wind could be heard whipping by,” he said in a Facebook message. “Down at the restaurant it sounded like a Hollywood soundtrack with the intense rain and howling wind.”

Because he was in a solid hotel, it wasn’t as scary as living through Hurricane Iniki in 1992, which left the Hawaiian island of Kauai badly damaged, he said.

“The fact that we still have internet access proves how solid their infrastructure is,” he said. “Hawaii and others should study the Marianas to understand how to design and build communication grids that can withstand a storm.”

Chris Hedges's Blog

- Chris Hedges's profile

- 1922 followers