Chris Hedges's Blog, page 421

November 10, 2018

Civilian Deaths in Yemen Increasing Despite U.S. Assurances

CAIRO — Airstrikes by Saudi Arabia and its allies in Yemen are on a pace to kill more civilians than last year, according to a database tracking violence in the country, despite the United States’ repeated claims that the coalition is taking precautions to prevent such bloodshed.

The database gives an indication of the scope of the disaster wreaked in Yemen by nearly four years of civil war. At least 57,538 people — civilians and combatants — have been killed since the beginning of 2016, according to the data assembled by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, or ACLED.

That doesn’t include the first nine months of the war, in 2015, which the group is still analyzing. Those data are likely to raise the figure to 70,000 or 80,000, ACLED’s Yemen researcher Andrea Carboni told The Associated Press. The organization’s count is considered by many international agencies to be one of the most credible, although all caution it is likely an underestimate because of the difficulties in tracking deaths.

The numbers don’t include those who have died in the humanitarian disaster caused by the war, particularly starvation. Though there are no firm figures, the aid group Save the Children estimated hunger may have killed 50,000 children in 2017. That was based on a calculation that around 30 percent of severely malnourished children who didn’t receive proper treatment likely died.

Renewed uproar over the destruction has put Washington in a corner. The U.S. has sold billions of dollars in weaponry to Saudi Arabia, backing the fight to stop Shiite rebels known as Houthis, who Washington and the coalition consider a proxy for Iran.

That along with tensions over the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi inside the country’s consulate in Istanbul may be key factors why Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on Oct. 30 made their biggest push yet for an end to the war, calling for a ceasefire within 30 days and resumed negotiations.

Only a month earlier, Pompeo gave a powerful show of support to the coalition by certifying to Congress that Saudi Arabia and its allies were taking measures to prevent civilian casualties. Certification was a required step in continuing U.S. aid, which includes providing intelligence used in targeting and mid-air refueling for coalition planes.

But deaths from the coalition campaign show no sign of slowing.

Coalition airstrikes and shelling killed at least 4,489 civilians since the beginning of 2016 — nearly three-quarters of all known civilian deaths, according to ACLED’s figures.

As of Nov. 3, at least 1,254 civilians were killed by the coalition this year, a rate of four a day. In comparison, 1,386 civilians died in strikes the previous year, or 3.79 a day.

Asked about the finding, the U.S. State Department said in an emailed reply, “Throughout this conflict, the United States has urged all parties to abide by the Law of Armed Conflict, work to prevent harm to civilians and civilian infrastructure, and thoroughly investigate and ensure accountability for any violations.”

Bloodshed has surged from fierce fighting at the Red Sea port city of Hodeida, which coalition forces have been trying to retake from the Houthis since June. Civilians have been killed in airstrikes as well as by Houthi shelling and land mines.

Since June, more than 4,500 people — including 515 confirmed civilians — have been killed in Hodeida, nearly triple the number from the first five months of the year.

Aid agencies fear worse is yet to come. The coalition appears to be accelerating its assault before any cease-fire. Its forces have nearly encircled the city, where tens of thousands of people are trapped along with thousands of Houthi fighters. The port is Yemen’s main point of entry for food and humanitarian aid, so any cutoff could push millions into starvation.

The coalition launched its air campaign in March 2015 after the Houthis took over northern and central Yemen, driving out the internationally recognized government. The rebels were prevented from overrunning the south only by the coalition’s bombardment and support for militia forces.

Tracking casualties is enormously difficult. The few independent monitors on the ground do not have wide access; officials on both sides have an interest in manipulating figures; deaths often take place in remote areas and even in populated areas, confusion of battle makes confirming numbers hard.

The most widely used estimate has been 10,000 dead, made in January 2017 by the United Nations.

In October, the U.N. humanitarian coordinator said at least 65,000 people have been killed or injured since 2016, including 16,000 civilians killed, based on data from health centers. U.N. officials did not reply to queries to elaborate on the figures.

ACLED builds its database on news reports from Yemeni and international media and international agencies. It covers everything from airstrikes, shelling and ground battles between the various forces to militant bombings and violence at protests. The group receives funding in part from the U.S. State Department and Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Because of its transparency, its figures are often cited by U.N. agencies and non-governmental organizations. But they caution that even ACLED’s data cannot give the full picture — only “the least bad best guess” as an official at one agency put it.

Pinning down how many of the dead are civilians is even tougher.

ACLED counted 6,242 civilians killed since 2016 by “remote violence” on civilian targets — meaning airstrikes, artillery or shelling by either side. Of those, shelling by the Houthis or their allies killed 977.

The full toll is likely much higher. The vast majority of deaths — more than 34,000 — are categorized by ACLED as resulting from battles. But it is impossible to determine whether those are combatants or civilians, Carboni said.

“It’s likely an underestimate,” he said of the civilian toll. “The numbers caught in the crossfire are not known.”

__

Associated Press writers Maggie Michael in Cairo and Matthew Lee in Washington contributed to this report.

November 9, 2018

Billionaires, Not Voters, Are Deciding Elections

The recent midterm elections offered an opportunity for America’s moneyed elites to spend their ridiculous wealth on a catalog of their favorite causes and candidates. We are locked in a vicious cycle, where billionaires continue to amass wealth due to policies their influence has bought, which in turn enrich them with even more resources with which to shift the American polity in their favor.

Part of the problem is that billionaires’ control over our democracy is largely invisible. As a recent study by The Guardian showed, high-profile wealthy elites like Warren Buffett or Bill Gates are anomalies. To that point, “[M]ost of the wealthiest US billionaires have made substantial financial contributions—amounting to hundreds of thousands of reported dollars annually, in addition to any undisclosed ‘dark money’ contributions—to conservative Republican candidates and officials who favor the very unpopular step of cutting rather than expanding social security benefits,” write the report’s authors. “Yet, over the 10-year period we have studied, 97% of the wealthiest billionaires have said nothing at all about social security policy.”

The midterm races in California saw several examples of the insidious ways in which the billionaire class made its mark on democracy, most notably in the defeat of Proposition 10, the state ordinance that would have expanded local governments’ jurisdiction over rent control. Several years ago, Wall Street hedge fund managers began scooping up rental properties and foreclosed homes in Los Angeles. According to journalist David Dayen, “Hedge funds, private equity firms and the biggest banks have raised massive amounts of capital to buy distressed or foreclosed single-family homes, often in bulk, at bargain prices.” He added, “It’s the next Wall Street gold rush, with all the warning signs of a renewed speculative bubble.”

So it should have come as no surprise that those same firms spent millions to protect their investments from returning lower profits in their fight against Prop 10. Sadly, Californians bought the corporate propaganda hook, line and sinker, and voted it down by a whopping 61.7 percent, saying “no” to rent control. (Incidentally, the opposition to rent control was also bizarrely funded in part by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association.)

Also in California, billionaires bankrolled the campaign of Marshall Tuck, a corporate candidate for school superintendent who strongly supports the privatization of schools. The race between Tuck and his union-backed rival, Tony Thurmond, broke records for the millions of dollars that the candidates raised and the tens of millions that flowed in from outside groups—a shocking trend considering the down-ballot status of the race in a critical midterm election year. Among the deep-pocketed individuals who backed Tuck were members of the Walton family, the CEO of Netflix and Eli Broad, a wealthy philanthropist known for his pro-charter school agenda.

If voters knew that billionaires were spending ridiculous amounts of money to elect a pro-privatization candidate, surely teachers and the parents of public school students might be inclined to view them with distrust?

In San Francisco, voters cast ballots for a tax initiative called Proposition C, a progressive tax on large corporations aimed at funding initiatives for the homeless. But Proposition C passed, likely because there were billionaires spending big on both sides of the campaign. The city has Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff to thank for deigning to do the right thing and pushing for the initiative in opposition to the likes of Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey and others.

Countless examples abound around this nation, where billionaires have gotten what they wanted simply because they had limitless wealth to throw at their favorite causes. As voters, we need to become literate in the ways of the moneyed class when it comes to elections. It’s very simple: Figure out who has poured millions into an issue or candidate and ask whether that person’s agenda might be less than noble. It may be that once in a while, the values of ordinary Americans align with those of billionaires. But that is the exception rather than the rule.

Wealthy people are swimming in riches because the rest of us are not. Their wealth is relative—they are the haves, we are the have-nots. And they clearly like having a lot more than us—and are willing to spend some of their mountains of cash to ensure they remain ensconced in power.

Throwing enormous amounts of money at a race doesn’t always bear fruit. For example, the politically active billionaire Sheldon Adelson failed in his recent bid to stop a renewable energy initiative in Nevada. But these (mostly) male magnates are so wealthy that the calculus of their political influence is on a completely different scale than ours. They literally have money to burn. They could lose $100 million in a political fight and walk away still brazenly wealthier and more privileged than most of us could imagine being.

Billionaires are not all Republicans. Were it so clear-cut, ordinary Americans could unite under the wing of the Democratic Party to beat back the GOP’s billionaire agenda. But corporate greed is a bipartisan project. For example, J.B. Pritzker waltzed into the position of Illinois governor after running as a Democrat. He had so much money that he didn’t need to raise funds for his candidacy—he simply used his own, an unimaginable amount of $171.5 million. Had he lost, he probably would have had plenty left over to spend on a future second, third or fourth try until he won. His opponent, Republican incumbent Bruce Rauner, is also fantastically rich; between the two candidates, Illinois voters were bombarded with a whopping $230 million worth of campaign spending. Imagine the badly needed projects that such money could have funded.

Wealthy Americans are already benefiting hand-over-fist from the tax giveaway that their Republican proxies in Congress passed last year. According to The New York Times, the law didn’t necessarily help the “merely rich” but was a windfall for the “ultra rich,” because, as author Andrew Ross Sorkin noted, “If you’re a billionaire with your own company and are happy to use your private jet so you can ‘commute’ from a low-tax state, the plan is a godsend. You can make an assortment of end-runs around the highest tax rates.” The so-called “pass-through” tax deductions were written in expressly for the obscenely wealthy.

It appears that for the greedy few, no amount of wealth hoarding is enough. Alongside election literacy, we voters need to develop a healthy sense of disdain, disgust and revulsion toward the billionaire class. In matters of politics, they are literally the “enemies of the people,” to borrow a phrase from President Trump.

West African’s Harrowing Journey to U.S. Underscores Immigration Shift

SALEM, Ore. — The young man traversed Andean mountains, plains and cities in buses, took a harrowing boat ride in which five fellow migrants drowned, walked through thick jungle for days, and finally reached the U.S.-Mexico border.

Then Abdoulaye Camara, from the poor West African country of Mauritania, asked U.S. officials for asylum.

Camara’s arduous journey highlights how immigration to the United States through its southern border is evolving. Instead of being almost exclusively people from Latin America, the stream of migrants crossing the Mexican border these days includes many who come from the other side of the world.

Almost 3,000 citizens of India were apprehended entering the U.S. from Mexico last year. In 2007, only 76 were. The number of Nepalese rose from just four in 2007 to 647 last year. More people from Africa are also seeking to get into the United States, with hundreds having reached Mexican towns across the border from Texas in recent weeks, according to local news reports from both sides of the border.

Camara’s journey began more than a year ago in the small town of Toulel, in southern Mauritania. He left Mauritania, where slavery is illegal but still practiced, “because it’s a country that doesn’t know human rights,” he said.

Camara was one of 124 migrants who ended up in a federal prison in Oregon after being detained in the U.S. near the border with Mexico in May, the result of the Trump administration’s zero tolerance policy.

He was released Oct. 3, after he had passed his “credible fear” exam, the first step on obtaining asylum, and members of the community near the prison donated money for his bond. He was assisted by lawyers working pro bono.

“My heart is so gracious, and I am so happy. I really thank my lawyers who got me out of that detention,” Camara said in French as he rode in a car away from the prison.

Camara’s journey was epic, yet more people are making similar treks to reach the United States. It took him from his village on the edge of the Sahara desert to Morocco by plane and then a flight to Brazil. He stayed there 15 months, picking apples in orchards and saving his earnings as best he could. Finally he felt he had enough to make it to the United States.

All that lay between him and the U.S. border was 6,000 miles (9,700 kilometers).

“It was very, very difficult,” said Camara, 30. “I climbed mountains, I crossed rivers. I crossed many rivers, the sea.”

Camara learned Portuguese in Brazil and could understand a lot of Spanish, which is similar, but not speak it very well. He rode buses through Brazil, Peru and Colombia. Then he and others on the migrant trail faced the most serious obstacle: the Darien Gap, a 60-mile (97-kilometer) stretch of roadless jungle straddling the border of Colombia and Panama.

But first, he and other travelers who gathered in the town of Turbo, Colombia, had to cross the Gulf of Uraba, a long and wide inlet from the Caribbean Sea. Turbo, on its southeast shore, has become a major point on the migrant trail, where travelers can resupply and where human smugglers offer boat rides.

Camara and about 75 other people boarded a launch for Capurgana, a village next to the Panamanian border on the other end of the gulf.

While the slow-moving boat was far from shore, the seas got very rough.

“There was a wave that came and tipped over the canoe,” Camara said. “Five people fell into the water, and they couldn’t swim.”

They all drowned, he said. The survivors pushed on.

Finally arriving in Capurgana after spending two nights on the boat, the migrants split into smaller groups to cross the infamous Darien Gap, a wild place that has tested the most seasoned of travelers. The thick jungle hides swamps that can swallow a man. Lost travelers have died, and been devoured, boots and all, by packs of wild boars, or have been found, half out of their minds.

Camara’s group consisted of 37 people, including women — two of them pregnant, one from Cameroon and one from Congo — and children.

“We walked seven days and climbed up into the mountains, into the forest,” Camara said. “When it was night, we slept on the ground. We just kept walking and sleeping, walking and sleeping. It was hard.”

One man, who was around 26 and from the African nation of Guinea, died, perhaps from exhaustion combined with thirst, Camara said.

By the sixth day, all the drinks the group had brought with them were gone. They drank water from a river. They came across a Panamanian man and his wife, who sold them some bananas for $5, Camara said.

Once he got out of the jungle, Camara went to Panamanian immigration officials who gave him travel documents enabling him to go on to Costa Rica, which he reached by bus. In Costa Rica, he repeated that process in hopes of going on to Nicaragua. But he heard authorities there were not so accommodating, so he and about 100 other migrants took a boat around Nicaragua, traveling at night along its Pacific coast.

“All we could see were the lights of Nicaragua,” he said. Then it was over land again, in cars, buses and sometimes on foot, across Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico, all the way to the U.S. border at Tijuana. He was just about out of money and spent the night in a migrant shelter.

On May 20, he crossed into San Ysidro, south of San Diego.

“I said, ‘I came, I came. I’m from Africa. I want help,'” he said.

He is going to stay with a brother in Philadelphia while he pursues his asylum request.

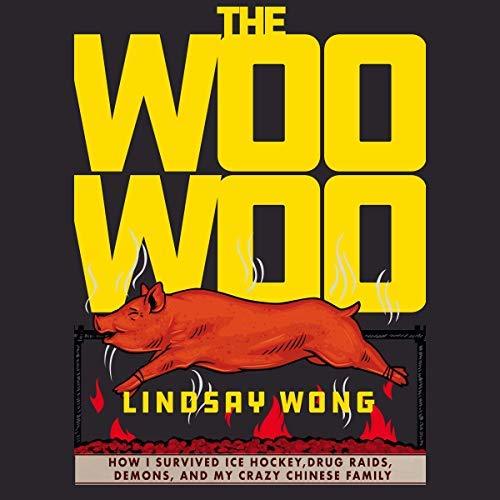

Demonic Possession in a Chinese Family

“The Woo-Woo: How I Survived Ice Hockey, Drug Raids, Demons, and My Crazy Chinese Family”

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

“The Woo-Woo: How I Survived Ice Hockey, Drug Raids, Demons, and My Crazy Chinese Family”

A book by Lindsay Wong

Editor’s Note: Eunice Wong, Truthdig’s book editor and the writer of this review, narrated the Audible audiobook of “The Woo-Woo,” by Lindsay Wong. They are not related.

Many people are deeply damaged by their childhoods, even those with kind and affectionate parents. And then there’s Lindsay Wong. Diagnosed with an incurable brain disorder in her early 20s, she writes, “Of course, [the neurologist] had no idea that the childhood I had survived in my neighborhood of meth labs and pot grow-ops, and—the most dangerous of all—my crazy parents, made this look like a cakewalk.”

Wong (no relation to me, though, full disclosure, I did narrate the Audible audiobook of “The Woo-Woo”) grew up in a family with severe mental illness and a predisposition for outrageous cruelty. Her family did not trust Western medicine, choosing instead to believe that the hallucinations, delusions, suicide attempts and abuse caused by conditions like serious paranoid schizophrenia were the result of “demonic possession.”

It sounds heavy, but Wong’s memoir, “The Woo-Woo: How I Survived Ice Hockey, Drug Raids, Demons, and My Crazy Chinese Family,” is as wickedly hilarious and irreverent as it is caustic and harrowing.

When Wong is 6 years old, her mother, attempting to hide from the murderous Woo-Woo ghosts that she believes have haunted her family for generations, takes her three young children to their suburban shopping center’s food court every single day, where they stay from opening until closing at 10 p.m., leaving only to go to school. She feeds them candy for breakfast, snack, lunch and dinner. “Having been raised on fast food from the mall and easy Chinese food (fried rice, lo mein, chop suey),” she writes, “I could eat anything and didn’t yet know the difference between margarine and mayonnaise. My taste buds for Western cuisine were seriously underdeveloped, and if someone handed me a sandwich full of gummy bears and potato chips, I would gladly eat it with a handful of sugar.”

Her father tells her, at 6 years old, that she was found in a dumpster. “That’s why you’re garbage,” he declares. It is an origin myth she believed for many years.

Her parents’ childhood nickname for her is Retarded Lindsay.

They hurl obscenities at her regularly. When she blacks out in public due to an allergic reaction to alcohol (her parents allowed their children to drink at the age of 9), they assume that she is “possessed,” with her personal failings to blame. After she recovers consciousness, her mother screams at her publicly, “So fucking irresponsible. So fucking retarded. I don’t know why you are so fucking stupid! What the fuck is wrong with your head? I should just sell you on fucking eBay!”

When Wong is in her early teens, her mother abandons the family for several weeks without explanation, and then returns, also without explanation. Her father tells her, during her mother’s abrupt absence, “If you won all your hockey game, she’d have stayed. No one like to watch loser. You need to win MVP so she will like you.”

Family summer vacations are taken in an RV, representative of the American Dream Achieved, in the parking lot of an outlet mall or Walmart. Vacation days are spent in the aisles of the brightly lit supercenter, dodging the Woo-Woo ghosts.

During a Walmart camping trip, her mother, piqued that Wong is sleeping peacefully, attempts to light her teenage daughter’s foot on fire.

All behavior is excused by blaming the ghosts.

Wong was never given a social or emotional compass with which to navigate the world. In order to survive as a child, she had to find structure and reason in irrational cruelty and emotional chaos. “But at thirteen…” she writes, “I did not know that it wasn’t socially unacceptable to go around burning people to wake them up. … Was it necessary? No. Painful? Yes. But was there a quicker way to get me out of bed? Probably not. I was beginning to come to terms with what she’d done—in the Wong way, at least.”

Raised by her parents, who were emotionally misshapen, culturally and linguistically disadvantaged, and mentally unbalanced, in an insular Chinese immigrant community on a rural-mountain-in-British-Columbia-turned-Stepford-suburbia, dotted with prefab McMansions, it took her until adulthood to ask herself, “How do you begin to understand that what was done to you is hateful and intolerable?”

When everyone around you is sick, sickness is all you ever know. Sickness is normal. There is nothing else. And it takes astonishing courage, willpower and sometimes simple good luck to break through the membrane, to see that there is another way to live, and believe that you yourself might be able to live that way.

There are glimpses of the racism of the outside world. Wong remembers “Chinese parents trying to be accommodating and white and country-club attending as possible.” But the white people, of course, do not want them: “Many of the white families moaned about the ‘Asian tsunami’ that had flooded their community and lamented the neighbourhood’s terrific ethnic decline into ‘Chinky Chinatown.’’ She describes her blunderbuss father as “assholian and unliked”—a terse description that combines both adult condemnation and the hurt of a small child seeing a parent disrespected. “I was facing a grave fact: how little control my parents had been given in this New World.”

When her high school guidance counselor tells Wong that she doesn’t have any empathy (Wong had wild behavioral issues as a child—she was a bully who snipped off braids, broke legs with hockey sticks, and punched children with Down syndrome in the face), her father, not knowing the word “empathy,” thinks that the counselor is calling his daughter “empty.” He asks, “Why the counsellor think you are empty? But you show them all your big piano award and they will be impress and say you are very full.”

Wong exhumes the deep, aching unhappiness of her Chinese immigrant family, “in a house souring with sadness.” It is a sadness made even more potent for being wordless. Her family does not know how to use language for anything besides basic functionality. “ ‘Hungry?’ my mother and father would ask at the dinner table, which really meant, ‘Are you okay? Are you sad?’ ”

“Family dinner in public …” Wong writes, “was always strange, since we really did not know how to communicate civilly. This was quickly done, lest any of us should admit to having fun. No one spoke, and the purpose of dining together in public seemed to be a competition of whoever could be the quietest and quickest eater. Really, we had nothing to say to one another.”

Perhaps most damagingly, “weak” emotions were forbidden in the Wong household. Displays of fear, sadness, vulnerability, and even affection were prohibited and to be avoided, because they made you susceptible to 1) a barrage of abuse from your parents, and 2) “ghosts” slipping inside you. Wong, never having been allowed to feel, grows up thinking of herself as a robot or an appliance: “The answer seemed so simple: if you didn’t react, you didn’t receive a fat stake in the chest.”

It is only when she is almost grown that she finally risks confronting her parents, while they argue about whether or not their daughter should kill herself—“You want to know why I’m a fucking mess? You raised me! I’m exactly like you!” But she is unable to break through. “[F]or a second, I like to think my family could see the bewildered hurt splotched and mirrored on all our real faces… [but] after a moment of intense and choking quiet, they ignored my outburst. … It was like I had never uttered the damning words at all. Like I had never been there at all.”

There is a terrible violence inflicted on children by the unhappiness of their parents. Even if your mother doesn’t try to set your foot on fire while you’re sleeping, the sadness, frustration and rage of a parent can profoundly stain and press down on a child’s life, far beyond childhood. Wong uses the metaphor of a toxic gas that permeates her family home, the poisonous fumes of sadness that she breathed from the day she was born until she finally broke free. It is an image recognizable to any unhappy family, not only those struggling with mental illness.

The Wongs deal with their unhappiness and more dramatic crises with complete and total passivity. When Wong’s mother goes missing for weeks, her father “refused to look for my mother or call the police. … Apparently, we just had to wait. … This was the candid, respectable, saving-face Chinese way: doing absolutely nothing.” And when Wong is shrieking with pain after her mother sets her foot on fire, her father turns on the radio to drown out her cries, and “My younger siblings had avoided her anger, picked up their books, and plugged in their music players, pretending to be busy—this is what we usually did if there was trouble near us. Someone could be twitching on the floor, obviously and deliriously Woo-Woo, and we would still be leisurely slurping our breakfast of watery congee and dehydrated egg—as long as it didn’t affect us.”

Her mother hoards food, haunted by her own childhood of third-world poverty in rural Hong Kong. Extended family dinners are gluttonous and hilariously gruesome:

At dinner parties, when the aunties and uncles talked about the old days, they loved to compare the exact size and length of their parasites. Supposedly, these were dangling snakes that they had to pluck out from their assholes. … They could spend hours arguing over whose monster worm was scarier, which one was hairier, whose had a googly eye. … Of course, all the cousins had lost our appetites by now, and we stared at the foot-long slimy rice noodles, the caterpillar-like vermicelli coagulating in sludgy sauce with queasy, unspeakable horror.

Her parents are compulsive pack rats, “the enthusiastic, obsessive immigrant kind”:

This collective obsession with starving meant that our basement, known as the food room, was basically a makeshift earthquake shelter or a post-apocalyptic zombie survival room for all your end-of-the-world needs. Shelves stocked with every type of pasta. Wheat crackers in obnoxious cardboard towers. Plastic bins became vending machines, spewing out every species of granola bar and rice noodle—fresh and stale—manically stockpiled together. I am not kidding when I say that we might buy six family-sized tubs of salsa, and then in the following weeks, my mother would desperately buy another three or four more.

Of course, within this abundance of warehouse club food, Wong was starving for affection, kindness and basic care.

The portraits of her family are appalling and riveting in their details, but the heartache comes when Wong pulls back to show us, with a compassion that somehow survived the trauma of her upbringing, that her monstrous parents are, as Auden wrote, just “Lost in a haunted wood/Children afraid of the night/Who have never been happy or good.”

“But I knew that my father would dutifully wake her,” Wong writes, after her father drives her to the airport, leaving her mother asleep at the hotel, “and they’d go to their favourite mall or parking lot to run a blockbuster marathon to lose the demons, and then they’d make their lonely trek up Pot Mountain without me.”

The child of unhappy parents dreads being with them, but the thought of the parents alone together, with no child to buffer their unhappiness, is perhaps the most terrible pain of all.

Because ultimately, Wong loves her parents. And her parents love her. The very rare moments of love have a serrating force, set as they are against the backdrop of everyday cruelty: “And then, shockingly, she pleaded with the angry ghost inside me, sounding as heartbreaking and desperate as she ever had, offering herself as the ultimate sacrifice, acting as if she liked me: ‘New York Ghost, come out now! Ghost from New York, get out of my retarded kid’s body! I will let you stay as long as you want in mine!’”

As an editor, I sometimes found parts of “The Woo-Woo” to be repetitive: the anguished questions about her mental state (“Was I destined to become as batshit as my mother?” “Was this who I’d eventually become?” “What if I was in the very early stages of Woo-Woo too?”), the recurring assertions that “this was the only way my mother knew how to care for us”; “This was all she knew how to do”; “This was the only way she knew how to protect us.” But as an actor narrating the book, I came to realize that this redundancy astutely mirrors how a tortured mind works: the obsessive, relentless circling of these questions and thoughts, like vultures that never go away.

Dr. Bruce Perry and Maia Szalavitz, in their book, “The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog and Other Stories from a Child Psychiatrist’s Notebook,” explain how trauma, particularly from an early age, can alter the physical functioning of the human brain. Wong’s memoir made me wonder whether her childhood was responsible, at least partially, for her adult diagnosis of migraine-associated vestibulopathy.

Perry and Szalavitz also wrote, “The truth is you cannot love yourself unless you have been loved and are loved. The capacity to love cannot be built in isolation.”

In the end, “The Woo-Woo” is a story of survival.

“The true opposite of depression is neither gaiety nor absence of pain but vitality: the freedom to experience spontaneous feelings,” Alice Miller wrote in “The Drama of the Gifted Child”—which could be an alternate title for “The Woo-Woo.” The end of Lindsay Wong’s book is the beginning of that journey toward freedom—an emaciated young bird finally released from years underground, blinking in the sun with tattered wings, but still able, miraculously, to stagger toward the open sky.

Trump Knew of Hush Payments to Stormy Daniels, Karen McDougal: Report

President Trump knew details and facilitated payments to silence two women about their alleged affairs with him, according to a news report published Friday.

Mr. Trump arranged meetings and phone calls about the payments with Michael Cohen, who was his personal attorney at that time, according to the Wall Street Journal. The report also said the Manhattan U.S. attorney has evidence of Mr. Trump’s involvement with the payments.

The payments were made to porn star Stormy Daniels and former Playboy model Karen McDougal ahead of the 2016 presidential election. In August, Cohen told a federal judge in New York the payments were made at the direction of “the candidate,” implying it was Mr. Trump’s decision to pay the women.

The goal of the hush money was to keep Ms. McDougal and Ms. Daniels from speaking about their alleged affairs with the media. Ms. McDougal was paid $150,000 for the rights to her story from the publisher of the National Enquirer, but the story was never published.

A similar payment of $130,000 was made to Ms. Daniels, whose real name is Stephanie Clifford.

Mr. Trump has denied affairs with both women.

The White House referred the Wall Street Journal to Trump’s outside counsel Jay Sekulow, who refused to comment.

Mr. Cohen pleaded guilty to eight criminal counts, some related to the payments. Willful cause of unlawful corporate contribution and one count of excessive campaign contribution. He is scheduled to be sentenced on December 12.

Evidence Shows U.S. Navy Ignored Sinking Ship of Migrants

A prosecutor in Sicily confirmed this week that he’d begun an investigation into allegations that a U.S. Navy ship appeared to have initially ignored cries for help from migrants aboard an inflatable raft off Libya—a delay that may have led to the deaths of 76 people including a baby.

“If the first time we had seen the ship, if it had come and helped us, there wouldn’t have been deaths,” charged one of the survivors.

Survivors described the events of the June 12 shipwreck in harrowing details in a video published by Italian news site La Repubblica.

To hear the survivors in their own words, watch the video posted by La Repubblica below. (The subtitles are in Italian, some of the survivors are sharing their stories in English, while others are doing so in French.)

“We saw the American ship,” said one survivor referring to the USNS Trenton. Several said they were close enough to see the American flag on the ship, adding that the sight of the vessel brought a sense of relief as the small dingy had begun to take on water. Trying to get the Trenton‘s attention, the migrants stood up, waved their shirts in the air, and called out.

But the U.S. Navy ship, according to survivors, did not approach them, but rather appeared to be moving further away even as the migrant ship tried to follow it.

The U.S. Navy and aid groups acknowledged that the ship ultimately did come to provide aid, helping 41 of those still alive.

But survivors say the relief came only when the ship came back around, some 30 minutes later. That was 30 minutes too late, as the boat had capsized and people were drowning.

“At that moment, I lost my only brother and my sister,” said one woman, adding that she too almost lost her life.

“We clearly saw the same American ship that had ignored us approaching,” the Guardian reports one man as saying in the video.

When they asked the people on the U.S. ship why they didn’t help at first, survivors said they were told rescuing people was “not their job.” The U.S. Navy had asserted in a statement about the rescue of the 41 people that it showed “our ability to respond rapidly to provide relief.”

According to the International Organization for Migration, those aboard the ill-fated raft were mostly sub-Saharan Africans. It added:

they had left Zuwara, in Libya, during the night of 11 June, sailing on a dinghy carrying 117 people, including 20 women and a one-year-old child. After seven hours of navigation, the boat began to deflate and many migrants fell into the water. The U.S. Trenton, patrolling nearby, intervened and managed to bring 41 people to safety. Overall, 76 migrants lost their lives, survivors said, including 15 of the 20 women and the one-year-old child.

Survivor testimony prompted the newly launched probe by Ragusa, Sicily prosecutor Fabio D’Anna, who said that initial testimony from them did not raise suspicion the naval ship had ignored them.

An Urgent Call for Humanity in the Age of Trump

Since ISIL targeted the Yazidi community in Iraq and Syria for genocide in 2014, Nadia Murad, co-recipient of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, has seen as many as 18 members of her family, including her mother, either killed or go missing. She has been enslaved and repeatedly violated, narrowly escaping the Islamic State with her life.

In recent years, she has found a champion in lawyer and human rights activist Amal Clooney, who helped her present her story to the U.N. as the first goodwill ambassador for the Dignity of Survivors of Human Trafficking. Now Murad’s speaking tour is the subject of “On Her Shoulders,” a powerful new documentary from director Alexandria Bombach.

“I knew that she [Nadia Murad] was telling her story over, and over, and over again, I wanted to know what effect that was having on the world, what effect that was having on her,” Bombach tells Robert Scheer. “What I saw is that every time she told her story, it was taking little bits of her, and pieces of her.”

What emerges is an intimate portrait of a survivor—one who has endured a kind of trauma few can begin to fathom. The film also explores what it means to be perceived as an “other,” not just in Murad’s native Iraq, but across the West.

In the latest installment of “Scheer Intelligence,” Bombach explores how her life experiences have informed her filmmaking, and why she might have gravitated toward a woman like Nadia Murad. “I ran away when I was 16 years old, and grew up with quite an abusive father,” she says. “I didn’t realize it when I was first making my films, [but] a big part of my childhood has affected how I see the world now, what stories I’m passionate and frustrated about [and] want to tell.”

Later in their discussion, the documentarian reflects on her personal relationship with Murad and the challenge of telling her story without exploiting Murad’s suffering. “There was a period where she [Murad] was really becoming disillusioned,” Bombach notes, ruefully. “It really made me question what the point of this whole thing was. … There was a period of time where it was more cold between us, and that broke my heart. I didn’t want to be another person in her life taking something from her.”

As the Trump administration deploys upwards of 15,000 troops to the border to confront a caravan of beleaguered Central Americans, Bombach hopes her film will remind audiences of our shared humanity, “especially when it comes to the migration crisis or the refugee crisis.”

Listen to her interview with Scheer or read a transcript of their conversation below.

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case, it’s Alexandria Bombach, who won the Best Director in U.S. documentary at Sundance earlier this year. She has made an incredible movie on Nadia Murad, this heroic woman from the Yazidis ethnic group and religion based mostly in Northern Iraq, but also spread because of refugee status and everything else, throughout much of the world. And Nadia won the Nobel Prize along with another activist against sexual violence. She was a rape victim in the brutal ISIS attack on the Yazidi people. Welcome, and just tell me a little bit about your own background, and then how you came to this project, and why the project is so important.

Alexandria Bombach: Yeah, Nadia, I met her in July of 2016. The production company RYOT hired me to make a short film about her. I had followed the genocide as it was starting in August of 2014, and when Nadia gave her speech, I saw a video of her giving her testimony at the U.N. Security Council in December of 2015, but it wasn’t until July of 2016 that I actually met her. After that, I followed her for three months during her campaign.

At that time, they were going at a blinding speed just saying, “Yes,” to every interview, every testimony, every meeting as much as they possibly could. It was pretty immediate that the documentary was proposed, and they said, “Yes, let’s go.”

RS: As somebody who watched your movie, I think you bring great sensitivity. I mean, for once, we’re treating people who have suffered a great deal because of historical events as full human beings, as our own children, our own spouses, and what have you. This movie is relentless in reminding us of the humanity of what are otherwise seen as a hoard of undifferentiated people. So my hat’s off to you as a filmmaker. I think it’s incredible.

Part of me wants to criticize the apolitical tone of it, but I realize it’s sort of necessary, I think, to what you’re trying to say, that these are full functioning human beings, the equivalent of any other human being in the world, and even though they’re huddled masses at different points, and victims, they count as much as anyone you’ve ever met or cared about in your life.

AB: I think that this film follows up my previous work in such a big way, because my first film in Afghanistan was called “Frame by Frame,” and that was about Afghan photojournalists. And a big part of that film was wanting to explore ideas around perception, and how we come to know a place that is this unknown known in so many ways.

The Taliban had banned photography when they were in power, and then when they were ousted in 2001, fledgling free press was started. I went there in the Fall of 2012 and 2013 to follow these four Afghan photojournalists, and the film kind of gives the audience a new perspective of this place from a different lens than we’re used to seeing it from. I was really interested in the idea of storytelling and how we tell stories, so when RYOT came to me with the idea of making a short film about Nadia, it was something I wanted to do right away because I knew that she was telling her story over, and over, and over again, I wanted to know what effect that was having on the world, what effect that was having on her.

What I saw is that every time she told her story, it was taking little bits of her, and pieces of her. So many people wanted to take photos, and wanted meetings, and wanted testimonies, and throughout the film you kind of see her start to question what difference this is actually making.

As a storyteller, as a documentary filmmaker, I was really confronted with what is our responsibility to survivors? What is our responsibility to refugees, and to these stories of people, and how are we packaging stories of trauma? What questions are we asking? What are we not asking? That became kind of the central idea around the film.

RS: Yeah, and I think it’s a very powerful idea. It goes against another current in documentary filmmaking, and in fact, in journalism, which some have called disaster porn. We see these tragedies, and then you show people this starving kid with flies around his head moments before he dies. Yes, it’s awful, but you lose the sense of a human being, you have an object.

So let me ask you as a filmmaker, how did you develop this sensitivity? Is this something you got in film school, is this something you grew up, it’s part of your nature? You describe yourself as kind of a nomad living in different places, so how does one become like you?

AB: I don’t know. I was a middle child, that wasn’t an option. I ran away from home when I was 16 years old, and grew up with quite an abusive father, but I think ideas around trauma and not having a voice, and feeling helpless, and really didn’t realize it at first when I was first making my first films, but now I’m 20 years later really realizing that a big part of my childhood has affected how I see the world now, and what stories I’m very passionate and frustrated about, and want to tell. I think having a big part of the films be about perception, and it comes from a place where I just feel frustrated about our views of the world, and where they’re coming from.

RS: Well, tell me what you think about that, our views of the world and where they’re coming from.

AB: Well, I think very often, to bring it back to Nadia having to repeat her story, and a lot of things are over-simplified, especially when it comes to advocacy work, and trying to get people to care about something. A huge trend, of course, has been for 30 years now, to really separate good guy and bad guy in our storytelling in our news and in advocacy work.

A big part of this film, for me, is trying to create more gray between the black and white, and I think I’m trying to do that with all my films, where you see a politician interview Nadia, or have a meeting with Nadia and give her a gift. At that point, you’d been with Nadia so much that it’s kind of cringe worthy that that happens, but at the same time, you understand that this woman is trying to help, but her good intentions have kind of gone astray. I think a big part of this and a part of every film I’m making is trying to make people think more critically about things and not give the answers, but make them think and ask more questions.

RS: I think what you just said may be the most important thing that anyone can learn about the current human situation in the world, particularly aggressive mass media, celebrity stuff, and everything else. The story here is an incredibly simple one of a person coming from a religious ethnic background, which many people would find different. I mean, we should say something about these people. I always have trouble pronouncing Yazidis, but-

AB: Yeah, Yazidis.

RS: … but let’s not take … Yazidis. Everything’s in question. Are they an ethnic group? Are they a religious group? Here is a young woman who had a life, a rural life on a mountain and she valued. She valued her family, she valued her associations, she values her people, and in your film, you show her having these encounters.

The thing that seems to drive her most of all is to not have ego get in there. This is not about her, it’s about her people. It’s helping her people. She doesn’t want to be objectified. She doesn’t want to be made a movie. She ends up winning the Nobel Prize. She ends up affecting the lives of her people very dramatically, and you in a very deliberately non-political way humanize this situation, and give us a heroine who is, the most heroic thing about her, is she’s trying to channel her experiences, dark experiences as a victim, I mean, horrible brutalization by ISIS.

I’m not going to go through that, the people should know that story by now. But what emerges is, “Hey, how can I channel this to help people, help my own people?” Her people matter. Now, you just threw something out before about your own background, and I have to ask about that. I mean, you say you had an abusive experience, not quite what she had?

AB: Well of course not, yeah.

RS: Yeah, but I mean, really, you put yourself in this. I know you don’t, I know it’s not a movie about you, but I’m interested in how do we get more documentary filmmakers like you, so help me out here.

AB: I mean, I think a big part of this film … One big choice that I did make in the film was not to ask Nadia the questions that I saw journalists asking her, because I really wanted the audience to question why we’re asking those questions in the first place. A lot of it has to do with gawking at trauma.

What’s been really encouraging for me since the Sundance premier was so many festivals that I’ve been to, I’ve have had so many conversations with other filmmakers about our responsibility as storytellers, and what questions we’re asking, and also the immense pressure and weight we have as storytellers of how we’re distilling these stories of trauma and presenting them.

I’ve definitely seen films even this year that were sensationalizing issues, or really pointing out trauma in a way that I didn’t feel comfortable with. I’ve had good conversations with those filmmakers, and so I think there’s a lot of conversations coming out of this film that I’m really proud of, but I think it’s still something we’re grappling with as documentary filmmakers, let alone journalists and other storytellers.

RS: But clearly you had a rapport with this woman. Now, Nobel Prize winner will be remembered, and deservedly so. That rapport must have come in part out of your own experience. I don’t want to belabor this, but just tell me a little bit about who you are.

AB: I had an abusive dad and just literally ran away from home, lived with a lot of different friends-

RS: Where was home?

AB: I was growing up in Albuquerque in New Mexico and lived with friends and then really got a full time job at a restaurant while going to high school, and then really realized that no one was going to really take care of me but me. And so it was a real pull yourself up by the bootstraps moment. In a lot of ways my grades got way better. I was very responsible with my life, got into a college and was a very good student and it kind of made me into the person I am today. So I don’t think of those moments as something that harms me, but definitely something that built me into a really strong person.

RS: And is that where you learned filmmaking?

AB: I actually went to school for business because at that time I felt a business degree was going to be the most secure thing, especially after working in restaurants and-

RS: Can I ask you where you went to school?

AB: Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado, so just a small liberal arts school and thankfully it was a liberal arts school because my professor Dr. Yose and Dr. Bill Dodds they both encouraged me to make short videos instead of turning in papers and so it was such a small school and the professors were so kind to me that they just let me do whatever I wanted. So I ended up making a lot of videos and films while I was there because I had been filming since I was 13 years old. And then once I graduated it was 2008, so really in the midst of the recession. And so there wasn’t any job to be had anyway, and I felt like many people graduating that year, you could either do exactly what you wanted to do and what you love and make no money or you could pick up a horrible job and make no money, or not get a job at all. And so in a lot of ways I have the recession to be thankful for that really pushed me into questioning what I was doing and just doing what I love.

RS: I’m going to ask you about that because this is a terrific movie and terrific in a lot of ways in which I would not make a movie and I suspect many males would not make a movie and many A-type males would not make a movie. So this is really an argument why you need diversity in filmmaking and entertainment and media and so forth. And I think it’s also a lesson in why we need directors that look different than the white male majority and have a different sensibility. And clearly there’s a conversation going on between you and the subject of your film. And when I first watched you I was like, “What is this about and why isn’t there more about politics and why isn’t there more of this and whatever.” And then I realized I was asking all the wrong questions and that you in fact were able to develop this incredible rapport.

And one of the things that’s so powerful here, as you develop a rapport with somebody on first look, you would think comes from the other side of the world the totally different religious experience. I mean what could be further away from Albuquerque in New Mexico than this tribal ethnic existence, and yet there’s incredible rapport in this film. Why don’t you just tell us about the person that won the Nobel Prize that you encountered and how modern she seems. I mean we have an idea of “the other.” They come from a more primitive society, more primitive religion, more primitive economy…there’s nothing primitive about this woman. And here we have an incredibly idealistic person who’s taken her sorrow and used it as a teaching moment in the most self-sacrificing way. I mean, that is really the big achievement of this woman and you’re capturing it in this movie, is it not?

AB: Yes, and I will say that Nadia, something that really struck me about her, people like to throw around words like strong or resilient when it comes to survivors. But what I really like to point out is that, she’s just so incredibly gracious with everyone that she encounters and she’s also incredibly patient, of course, very frustrated and wanting for things to move much faster than they are for this Yazidi cause. But with everyone that I saw her encounter, she was just endlessly kind and gracious and that included people that would say the most bizarre things to her or ask her to do things like sit in chairs and take photos that as a filmmaker I wanted to push them away from her and yell at them. But she was just continuously, just so kind and open to anyone who wanted to help her.

And I think that included me. And people like to give me a lot of credit for this access that I got, but I don’t really think I deserve it because so much of why they said yes to the documentary is because of the survivor’s guilt that they had at that time and just trying to do as much as they possibly could. And then while I was there, every bit of access I got was because of Nadia’s grace and it wasn’t because I was any different than anyone else. She was just incredibly kind and patient with me. That being said, there was a period where she was really becoming disillusioned with what impact these stories and the interviews and all these things the media was really having and was feeling possibly exploited by a lot of these things and was questioning, I think, me in the same way. And rightfully so, I was questioning myself and what we were doing and what the point of it all was. And I think that’s what kind of why the film is made in the way it was because there was such a period where I was like I don’t know what the point of all this is. What does awareness really do? The UN is already aware of what’s happening there, they are the people who can make a difference. These heads of state, you’ve met with many presidents, they are the people that can make a difference and nothing’s happening, nothing’s moving. So it really made me question what the point of this whole thing was and so there was a period of time where it was more cold between us and that broke my heart. I didn’t want to be another person in her life taking something from her, but by the end I had just been around so long I think we were close again but it wasn’t always just this completely tight relationship and I don’t want to give any impressions that it was.

RS: Any honest journalist and you are a great journalist would have to admit that they’ve experienced that tension, that alienation, that question. Are they part of the problem? Are they there to help solve the problem? And it’s just there. And certainly in any war situation, refugee situation. We’re going to take a quick a break now and we’ll be right back.

We’re back with Alexandra Bombach talking about the incredible film and let’s talk about the winner of the Nobel Prize or a co-winner of the Nobel Prize Nadia Murad and tell us really what you want us to take away from this movie about this situation, and I want to give you just one little hook here. This stuff doesn’t have to happen. We don’t have to be messing up other people’s lives and by we, I mean the powerful in the world and the comfortable and all that.

But what your movie really is about is something that didn’t have to happen. So why don’t you sort of control what remains of our time and tell us what you think we should get out of this movie about this incredible human being.

AB: I think the big things that I’m asking people to take away or I’m hoping that people take away after seeing this film is really questioning how we’re hearing stories and where our ideas of places are coming from and what our involvement is. I think it would be a disservice to the film and also a disservice to the Yazidis to suggest that this film provides any answers for how to solve any problems. But I don’t think that was the film that needed to be made. I think that the big issue was what was so disturbing while being with Nadia was how everything was being handled in the interim of actually getting to action. And “On Her Shoulders,” we’re really asking questions about media, we’re asking questions about what politicians are doing, we’re asking questions about the UN and diplomats and heads of state, and in all of that, for an audience member who’s not in any of those roles I’m hoping they’re asking themselves, “What am I looking for? And what am I listening to when it comes to stories around the refugee crisis in particular?”

RS: Again, it’s not wallpaper and it’s not just stuff to fill up the cable shows or fill up the evening news. And the question is, do we really care? And really what you’re capturing here, I would say the unstated texts, is how dare we ignore the consequences of what’s going on in world politics? How dare we think of these people as in any way less worthy of our concern? That is really the challenge I think of your documentary.

AB: Yeah. I think it’s really … After making several films in Afghanistan and then working with Nadia, I think it’s really disturbing how different people have come up to me and had conversations like, “Oh, they’re used to it or this is what they’re used to and this is just how it is.” I’m completely disturbed by that logic. I think that’s what makes me continue to make films in this region, is that it’s just so misunderstood, and we’re also combating so many stories that embolden those bizarre ideas. I think it’s a very disturbing state of affairs, especially when it comes to our lack of empathy and sometimes even apathy towards these issues.

RS: Well, the dehumanization of “the other,” I just had an interview with a fellow who spent a five years in the Marines and a year in Afghanistan. I’ve done other interviews where people have come out of our recent endless wars. Iraq, Afghanistan, the two that you have covered, we are principally involved. We didn’t create everything.

We didn’t do everything, but my goodness, looking at your work with Afghanistan, there was a king once, who was fairly a good king, and somehow the great powers got involved, and we were going to show the Russians that they’re going to have their Vietnam, and Zbigniew Brzezinski said, “What difference does it make? You have a few outraged Muslims.” No. You have a few outraged Muslims and the Yazidi people get killed or raped. I’m not blaming the Muslim religion here. There’s just putting your stick in the human condition and stirring it around. A lot, a lot, a lot of innocent people get killed.

I’ve seen this as a journalist all my life really. I went to Vietnam as a journalist in the early ‘60s and I’ve seen this. You come back and everybody treats it as a wargame, unless there’s a draft, unless you have to go. Oh, so stuff happens. Oh, stuff happens to vulnerable people. It happens to people who can’t get a passport. They can’t get out of the way of the fire.

That’s what you are describing here. You’re describing … I love the fact that you’re not … She didn’t get a doctorate, and she didn’t have a fancy education. She is an ordinary village girl, who is subject to, what, these global forces really. I don’t want to speak for your film. I can’t, but taking away from gender, I think the movie Alex Gibney did win an Academy Award for Taxi to the Dark Side where you find one person from a village and caught up in these events. These people, the Yazidi people were basically, they were going their way, one way or another for a very long time until the world bothered to notice them in a really disruptive way.

AB: Well, I think that what was so unique about the Yazidis is they were such a vulnerable minority in that area of the world. This is actually the 73rd genocide that the Yazidis have been through in their history. It was a very calculated choice that ISIS made to attack this one community and systematically have a genocide against them because they were so vulnerable to that attack.

RS: What I think is incredible about you as a filmmaker is that you’ve thrown away most of the props. There’s a clarity and a simplicity, and I’m using it in a very flattering way here. There’s a human perspective, and so circling back to the original thing of what makes you, you. And also what makes Nadia, Nadia, there’s a common human refrain of concern, feeling, love. Didn’t you really click in with these young women in some very fundamental way as, what, dare I say a sister?

AB: Well, I think just even being around Nadia, she’s so incredibly impressive as a human being. Reading her book, The Last Girl, I think she’s just always been that way. She can be very feisty. She’s hilarious. She’s incredibly sharp. We would give her a Wi-Fi password that was all letters and numbers and she would remember it right away and a week later be able to recite it to someone who asks for it just off the top of her head. She is an absolute brilliant person to even be around, and I felt very humbled to be around her for so long. It was an incredible experience.

RS: You have introduced us to an incredible human being, but I think the power of your film is that she’s not the only incredible human being that’s hurt by these events in the world. Whether it’s a drone attack or an unnecessary invasion or a stupid dictator or a violent, vicious dictator. These people out there, “the other,” are capable, as much as any of us being brilliant and hilarious and moral. Is that not the big takeaway from … I don’t know. I don’t want to put it on you, but it would seem to me this is a manifesto of a film.

AB: Yeah. I hope that people are already there going into the film. I think I’m pretty sad when it’s even a thing anymore that people don’t think that people on the other side of the world are like us. I think it’s sad that we’re not even there yet. I hope that’s … If people are there, I hope that that’s the takeaway.

RS: After having seen what you’ve seen, do you think that most of us are there? Did we really care about these people even when … you point out in the film. Most of the time when she went around and she got invited to the UN and she got there, people really weren’t listening. They certainly weren’t acting, but do you ever any doubt that most of our—

AB: I definitely have doubt, but I think it’s my hope. Yeah, definitely. I think we’re definitely in a sad state of affairs, especially when it comes to the migration crisis or the refugee crisis that especially with any story around refugees, that there is a level of otherness and apathy towards those issues. It’s very depressing.

RS: Yeah. Well, let’s just say we’re recording this on a day when there’s the migrants from political violence and economic disaster and everything else trying to move from Central America up to the Mexican border, and they’re being treated by our own president as criminals. I don’t want to do too much editorializing here, but it’s important whoever is president to remember the people that we claim to care about or liberating, they’re not cannon fodder. You watch this movie, and it’s now screening everywhere. People have that opportunity on our shoulders. It’s really great to talk to you, Alexandria Bombach. I appreciate it. We urge people to go see the film, to be reminded that we all do matter and that history does matter.

Our engineers here at KCRW are Mario Diaz and Kat Yore. Our producers are Joshua Scheer and Isabel Carreon. This is Robert Scheer for another edition of Scheer Intelligence. See you next week. Bye.

Will Brian Kemp Get Away With Suppressing Georgia’s Black Vote?

What follows is a conversation among activist Anoa Changa, investigative journalist Greg Palast and Aaron Mate of the Real News Network. Read a transcript of their conversation below or watch the video at the bottom of the post.

AARON MATE: It’s The Real News, I’m Aaron Mate.

The governor’s race in Georgia has been one of the most heated contests of the 2018 Midterms. And now, days later, its two contenders are at odds over whether or not it’s over. Republican candidate and Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp has declared victory over Democrat Stacey Abrams with a lead of over 63,000 votes. On Thursday, Kemp announced he is resigning as Secretary of State. And moving forward with the transition.

BRIAN KEMP: We will work together in the days, weeks and months ahead to ensure a smooth transition that keeps our state on the path for prosperity, growth and opportunity. In addition to having the right team, you need energy and focus. That is why, effective 11:59 AM today, I’m stepping down as secretary of state.

AARON MATE: The fact that Kemp was secretary of state in a vote in which he was a candidate is just one part of the controversy. As Georgia’s top election official, Kemp has overseen a longtime crackdown on voting rights. Just before the election, Kemp froze the voting registration of some 53,000 people, most of them Black. His opponent, Stacey Abrams, is not conceding and is calling for all provisional ballots to be counted.

STACEY ABRAMS: We’re here tonight to tell you, votes remain to be counted. There are voices that are waiting to be heard. Across our state, folks are opening up the dreams of voters and absentee ballots. And we believe our chance for a stronger Georgia is just within reach, but we cannot seize it until all voices are heard. And I promise you tonight, we are going to make sure that every vote is counted. Every single vote. Every vote’s getting counted.

AARON MATE: Joining me to discuss the ongoing race in Georgia for governor are two guests. Greg Palast is an investigative journalist whose books include the best-selling, The Best Democracy Money Can Buy, which also was turned into a film of the same name. Just last month, Greg Palast joined a coalition of civil rights groups in suing Brian Kemp for removing over 340,000 Georgians from the voter rolls. And Anoa Changa is an attorney and host of the podcast, The Way With Anoa, resident of Georgia where she is joining us from.

Welcome to both. Anoa, I’ll start with you. What is the latest? As we’re speaking, I believe the Abrams campaign is giving an update on their status. Let me ask you first. I mean, they are trailing by a considerable amount. So in terms of the vote count, if these provisional ballots that they want can be counted, could that be enough to make up the difference?

ANOA CHANGA: I think we have an even bigger problem. From the meeting I just came out of this morning, the Abrams legal team is having a press conference right now. This is noon on Thursday, I just came out of a Board of Elections hearing here in Fulton County, which is where Atlanta is, and we actually just found out that the count that the county has is actually different from what the secretary of state’s office is even reporting. So we don’t actually even know what the actual vote really is, considering the data that Brian Kemp has been reporting may or may not even be entirely accurate if this is something that has played out in other counties as well.

They reported over 16,000 absentee ballots were counted here in Fulton County, his website showed only 4000 and claimed that the total was complete. So we really don’t know what to believe and trust. And quite honestly, considering what he pulled this past weekend with this fake hacking investigation, which we also found out caused the websites- there’s an internal website that the different Board of Elections use as well as the public website usually sync up so that people with absentee ballots can track their ballots as they’re being counted, processed and received. And for whatever reason, that syncing has not been happening and these are both websites that are controlled by the secretary of state’s office.

We also have the secretary of state, who has not only just been biased towards himself, his own favorite candidate, but he has blatantly breached whatever duty of- just his impartiality in an election that he is supposed to have as the chief election officer, as we’ve also seen by him declaring himself winner, despite the fact that only four or five counties out of 159 have even certified elections, and larger counties like Fulton County will not be certified until Tuesday, given that Monday’s a federal holiday.

AARON MATE: Just to explain that for anyone who is not familiar with what Anoa referenced, so right before this vote, again, Brian Kemp is overseeing, even though he is a candidate in it, just before he accused Democrats of hacking attempts of voting sites but provided no evidence. Let me go to Greg Palast. What’s your response to Kemp resigning as secretary of state, which has been a demand for a long time, but of course that demand was made before the vote, not afterward.

GREG PALAST: Yeah, I mean he decided who could vote. Remember, this guy purged half a million voters in the past year, in 2017, half a million Georgian voters. In my investigation, which began for Rolling Stone and now for the Palast Investigative Fund, we actually went through, name by name, top consultants in address verification. He removed about 400,000 people for supposedly moving from either their home county or out of Georgia. And 340,134 of those people have never moved, have never moved. It’s a mass, mass ethnic cleansing of the voter rolls. And therefore, you have a massive number of provisional ballots. So obviously, Kemp should have resigned and there should be no Republican official on it.

They have one of his flunky deputies now take over and basically make it appear that there’s some type of impartiality. That’s completely nuts. I mean, the question for me, really, for the Abrams campaign, is are they really going to fight ballot by ballot on provisional ballots and the absentee ballots? I know one absentee voter whose ballot was disqualified, my daughter, in Savannah. And I can tell you that I went to polling stations where they usually give out three, four, five provisional ballots. They were giving out fifty, and that’s because all of these purged voters never were notified by Brian Kemp that he had removed them from the voter rolls. They got no notice. So people like the filmmaker here in Atlanta, Rahiem Shabazz-

AARON MATE: Greg, let me stop you there because we have the clip. You went with Rahiem Shabazz to the polls and you followed him as he filled out his ballot. This is what happened.

GREG PALAST: Rahiem went to vote, but they didn’t let him vote on a ballot ballot, they gave him a provisional ballot, a placebo ballot. You think you voted, but maybe not.

RAHIEM SHABAZZ: Once I get the provisional ballot, the lady hands me- it looked like a biohazard bag. So I have no number to verify that I actually voted. These are the tactics of Brian Kemp and this is voter suppression and he is the chief of voter suppression.

AARON MATE: That’s Rahiem Shabazz, who Greg Palast interviewed at the voting site. Another voter who Greg Palast interviewed was someone who was denied the right to vote. She is 92 years old. Her name is Christine Jordan.

GREG PALAST: Has this ever happened to you before?

CHRISTINE JORDAN: Never.

GREG PALAST: How long have you been voting?

CHRISTINE JORDAN: All my life, ever since I was old enough. I’ve been voting right here ever since 1968.

JESSICA LAWRENCE: And it’s just- it’s horrible. And I say that because the West End- she’s been in this community back when they were doing sit ins. She had civil rights meetings in her home. And today to come out and then not be able to vote and no one can give you explanation, it’s extremely emotional and it bothers me. It bothers me to my core. Like, there’s actually no record of her whatsoever voting in any election whatsoever and it’s ridiculous.

AARON MATE: That last voice there was Jessica, the granddaughter of 92 year old Christine Jordan, who was turned away at the ballot box. Greg Palast, talk about these cases.

GREG PALAST: Well, by the way, Christine Jordan is Martin Luther King’s cousin. Here we are 50 years later. And she talked about the family and Daddy King and everyone at her house, Coretta. And so the real question is, Will Stacey Abrams take these voters and go into federal court and say that they were purged wrongly, and their provisional ballots should count? If that happens, and she can prevail, that Brian Kemp purged the voter rolls to his benefit and has set down a rule that if a voter was- even though they’re a legal voter they haven’t moved, that they are at their legitimate address and he purged them wrongly, he’s still directing counties not to count those provisional ballots. It’s like, “Tough luck. If I purged you, you’re purged, baby, and you don’t get to vote.”.

And in fact, he was advising counties not to even give out provisional ballots, not to even give them out. So that’s what’s going on. Stacey Abrams, by the way, does not have to win in the first round, just make sure that Kemp stayed below 50 percent. Then we can get these people back on the voter rolls, 340,000 of them, so they can vote.

AARON MATE: Greg Palast, I know you have to go, so we appreciate your time and for people who want to check out more of Greg’s reporting from Georgia and to support it, you can go to gregpalast.com.

Anoa Changa, back to you. Let’s talk about that the question that Greg raised there, in terms of is Abrams and is her campaign going to be willing to contest this, basically, ballot by ballot? What do you think the answer is?

ANOA CHANGA: I think, from what she has said, that every vote must count, that that’s what they will likely do. I’m not quite sure exactly, because I look forward to actually going back and watching a replay of the legal team’s press conference to see exactly what the strategy is. I do know that other organizations- I have a friend who’s a lawyer who’s been involved in some of the civil rights elections lawsuits that have been going on. She’s actually one of the people that helped make sure that Morehouse students were able to go vote at Booker T. Washington Tuesday Night. She was saying that there was more coming down the pipeline.

Of course, because of the ongoing nature of litigation, she could not tell me what that more actually is. But a lot of people, different organizations, lawyers, no one is taking this lightly right now. And this is not about being upset that Stacey Abrams didn’t win outright. This is about a miscarriage of justice, this is about undermining our democracy, and this is probably one of the greatest travesties that we’ve seen in the modern era, including 2000’s Bush v Gore. And I’m really thankful that Stacey Abrams is not Al Gore and is not being advised just step aside and let this happen. We have watched Brian Kemp exploit his position and disenfranchise people nonstop. He’s been sued numerous times over the past eight years, we’ve discussed this previously.

And watching what he just did in this past week alone has been extremely problematic in listening to the Board of Elections here in Fulton County, discussed various things about vulnerabilities, about how the sites aren’t linking up properly. Because in this fake investigation he claimed needed to happen, it makes me wonder what else did this investigation create havoc-wise in terms of the internal systems, in terms of people being able to track their absentee ballots. And even with the provisional ballots, will people be able to check on the status of their ballots in time to make sure they count, by the close of business tomorrow? There’s a lot at stake right now.

AARON MATE: Even just hearing the individual stories that come out in Georgia, that exemplify voter suppression. I mean, that video we saw there of a 92 year old woman, a cousin of Dr. King, being turned away. We have the story of a group of Black senior citizens taking a bus to go do some early voting and then being stopped by state officials. You have a case where a voting site worker was sued by the state and charged with a felony because she gave some pretty simple assistance to a voter who didn’t know how to use the machine. What, anecdotally, Anoa, can you tell us about what you’ve heard about how voter suppression has played out?

ANOA CHANGA: I just had the opportunity to meet the state board president for the NAACP this morning at the meeting I referred to. And the NAACP, there’s been a couple articles about this, about how people were trying to vote for Stacey Abrams and the machines would jump and select Brian Kemp instead. Now, thankfully, the people they talked to, their members, and they knew what steps to take, how to get help. But imagine being the average voter who wouldn’t know how to go talk to a poller, how to get help, how to make sure the card isn’t going to register for the opponent, the person you’re not voting for. Think about how frustrating that can be for the average person. It’s one story that we’ve heard, and it’s been recounted mostly by people who said that the ballots were shifting.