Chris Hedges's Blog, page 407

November 25, 2018

Jeremy Corbyn: Brexit Deal ‘Leaves Us With the Worst of All Worlds’

BRUSSELS—The Latest on the Brexit deal (all times local):

4 p.m.

A former leader of Britain’s Conservative Party says he cannot support the Brexit deal negotiated by Prime Minister Theresa May.

Michael Howard said Sunday that May’s deal has many shortcomings, adding “It’s not a deal that is a good deal for the U.K.”

Howard says the biggest problem is the way Britain would have to seek European Union permission to sever all ties to the EU if a “backstop” agreement comes into force.

“That seems to me to be an absolute negation of taking control, that would put us in a worse position than we are now,” he told BBC Radio.

Howard was party leader when the Conservatives were defeated by Tony Blair and Labour in 2005. He serves in the House of Lords.

___

3:25 p.m.

Romania’s president has welcomed the Brexit agreement saying it will protect the rights of hundreds of thousands of Romanians in Britain.

President Klaus Iohannis said Sunday that while most EU members were sad that Britain was leaving the bloc, if the agreement passes it “will protect Romanians and other Europeans who are in Britain.” He also said after the summit that “it guarantees all their rights … they can work, study, receive pensions, health insurance and so on. ”

“We were very concerned about these issues, and we successfully pushed for these things to be clearly defined.”

He welcomed the fact that Romanians wouldn’t need visas to travel to Britain after it leaves the bloc.

Romanian officials estimate about 500,000 Romanians live in Britain, although just 190,000 are officially registered there.

___

2:45 p.m.

The leader of Britain’s main opposition party says that it will vote against the Brexit deal when it comes before Parliament.

Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn said after the EU summit Sunday that the arrangement agreed to by Prime Minister Theresa May is a “bad deal for the country” that “leaves us with the worst of all worlds.”

He said that Labour’s goal is to vote this deal down in Parliament and then “work with others to block a no-deal outcome” that many believe would badly damage Britain’s economy.

The party would instead fight for a “sensible deal” that would include a permanent customs union, a single market deal and guarantees on workers’ rights and other issues.

Labour’s opposition to May’s proposal will make it harder for her to win majority support in Parliament.

___

2:30 p.m.

French President Emmanuel Macron has said the European Union must “learn lessons” from Britain’s decision to leave it.

Speaking from Brussels, Macron said that the exit of a major member state for the first time in the bloc’s history showed “Europe is fragile” and the EU “is not a given.”

The French leader said European leaders have a duty to “protect it against all those who forget that it is a guarantee of peace, prosperity and security.”

Macron also paid homage to British Prime Minister Theresa May for seeking a “path to durable cooperation” with the EU, while defending UK interests during negotiations.

Twenty-seven EU leaders endorsed a deal Sunday that sets out the terms of Britain’s departure on March 29 and sets a framework for future ties.

___

2 p.m.

British Prime Minister Theresa May says she is not sad about leaving the European Union even though she recognizes some Britons and some European leaders feel that way.

May said Sunday she is “full of optimism” about Britain’s future outside the EU bloc, after leaders finally signed off on a Brexit deal in Brussels after months of negotiations.

“The way I look at it, actually, this is for us now to move on,” she told a press conference, asserting Britain had reached a “good deal” with many benefits for Britain and its people.

She spoke after German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other European leaders expressed sadness about Britain’s planned departure.

May said Britain will continue to have warm, friendly relations with European countries after it leaves the EU bloc.

___

1:50 p.m.

Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar is welcoming the Brexit agreement, saying that anybody who believes a better deal can be found is deluding themselves.

Varadkar said that “the entire European Union today was very much of the view that there couldn’t be a renegotiation.”

He said those who oppose the deal “don’t agree among themselves what that better deal could be. They probably wouldn’t have a majority in parliament for an alternative deal either, and they certainly wouldn’t have 28 member states signed up to it.”

He added: “Any other deal really only exists in people’s imaginations.”

Varadkar said he believes British Prime Minister Theresa May’s chances of getting the agreement through parliament are strong.

British lawmakers, he believes, will see that “the alternative is a no deal, cliff edge Brexit which is something of course that we all want to avoid.”

___

1:40 p.m.

British Prime Minister Theresa May said the Brexit deal that European Union leaders signed off on Sunday was the best and “only possible deal” for the British parliament to vote on, warning lawmakers there would be no option to renegotiate anything.

May told reporters after a Sunday morning summit she agreed with EU leaders saying that there would be no other options on the table before Britain leaves the bloc on March 29.

“If people think somehow there is another negotiation to be done, that is not the case,” she said.

“This is the deal that is on the table. This is the best possible deal. It is the only possible deal.”

___

1:30 p.m.

British Prime Minister Theresa May says the U.K. Parliament will vote on the divorce deal with the European Union before Christmas.

May says Sunday’s signing-off on the agreement by the EU marks the end of one phase and the start of a “crucial national debate” on Britain’s future.

May says she will fight “heart and soul” to get backing for the deal, which faces huge opposition among her Conservative lawmakers as well as the opposition.

She says “I think we have a duty as a Parliament … to deliver Brexit.”

___

1:25 p.m.

The Spanish prime minister says that Spain’s position on the disputed British overseas territory of Gibraltar has emerged stronger in the Brexit deal signed off Sunday by European Union leaders.

“With the departure of the U.K. we all lose, especially the U.K.,” Pedro Sanchez told reporters at a news conference Sunday after the EU leaders meeting. “But in relation with Gibraltar, Spain wins, and Europe wins.”

Spain claims Gibraltar even though it was ceded to Britain in 1713. The country was the last to agree to the Brexit deal, saying it would only back it on condition of a guarantee of Madrid’s say in the future territory at its southern tip.

Asked whether Spain would seek co-sovereignty of Gibraltar during future negotiations, Sanchez said that his government planned to “talk about everything.”

___

1:20 p.m.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel tells reporters in Brussels the Brexit deal brokered between the EU and Prime Minister Theresa May is a “diplomatic piece of art.”

Merkel says “it’s a historic day, which triggers very ambivalent feelings … it is tragic that the UK is leaving the EU now after 45 years, but we have to, of course, respect the vote of the British people.”

She praised the deal struck “in an extremely difficult situation, in a situation without any precedence because we haven’t had it before that a European country leaves the EU.”

Merkel said while the agreement was based on very hard negotiations, it “considers both sides’ interest.”

___

12:40 p.m.

The European Commission chief is urging the British parliament to back the Brexit deal brokered between the EU and Prime Minister Theresa May, saying “this is the only deal possible.”

At the end of a largely ceremonial summit to rubber-stamp the U.K. withdrawal agreement from the bloc and a draft text on the future relations, Jean-Claude Juncker made it clear the British House of Commons should not count on starting a renegotiation.

“It would not be a good idea to lecture the House,” Juncker said, but insisted that it was only deal possible.

The deal must still be endorsed by the British parliament and EU parliament. Opposition parties and many in May’s own Conservative Party have opposed the agreement.

___

12:15 p.m.

The leader of the Democratic Unionist Party in Northern Ireland says there are no circumstances under which her party would support the current Brexit deal.

Arlene Foster said minutes after the deal was endorsed by European Union leaders in Brussels on Sunday that her party is firmly opposed to its provisions because it would separate Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom.

She stopped short of saying her party would end its support of Prime Minister Theresa May’s Conservative Party, a key point because the DUP supplies the votes needed to prop up May’s minority government.

Foster is calling for more talks to come up with a better plan.

“I believe we should use the time now to look for a third way, a different way, a better way,” she told the BBC.

___

12:10 p.m.

European Parliament President Antonio Tajani has used the EU Brexit summit to highlight a separate issue — violence against women.

Tajani sported a red swipe under his left eye as he addressed a press conference at the EU summit. In Italy, the mark stands for support of the UN’s International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.

Tajani said in a Twitter post that “Nothing can justify violence against women. My mother taught it to me. I taught it to my children.”

___

10:45 a.m.

European Council President Donald Tusk says the European Union has approved a Brexit deal with Britain.

Tusk tweeted that 27 EU leaders meeting in Brussels “endorsed the Withdrawal Agreement and Political Declaration on the future EU-UK relations.”

The deal sets out the terms of Britain’s departure on March 29 and sets a framework for future ties.

Now British Prime Minister Theresa May faces the tough task of selling the deal to a skeptical U.K. Parliament.

___

10 a.m.

European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker says it’s a tragedy that Britain is leaving the European Union but that the country is walking away with the best deal it could hope for.

Juncker said that “it’s a sad day,” as he arrived Sunday for an EU summit in Brussels to endorse the Brexit agreement.

He told reporters that the summit “is neither a time of jubilation nor of celebration. It’s a sad moment, and it’s a tragedy.”

Asked whether a better agreement can be found, should the U.K. Parliament reject it, Juncker said: “This is the deal. It’s the best deal possible. The European Union will not change its fundamental position.”

___

9 a.m.

Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaite says European Union leaders will agree Sunday on the terms of Britain’s departure from the bloc, but that “it is up to Britain what is next.”

Asked at an EU summit Sunday what would happen if the U.K. Parliament rejects the Brexit deal, Grybauskaite said: “it’s not now our concern, it’s a British concern.”

She says several things could happen in that case, including a new referendum on Brexit, new elections in the U.K., or a request to renegotiate the deal with the EU.

Britain leaves on March 29, but future relations and trade will be tackled during a transition period lasting at least until the end of 2020.

Grybauskaite said “the process will still be long.”

___

8:30 a.m.

European Union leaders are gathering to seal an agreement on Britain’s departure from the bloc next year, the first time a member country will have left the 28-nation bloc.

At a summit in Brussels Sunday, the leaders are due to endorse a withdrawal agreement, which would settle Britain’s divorce bill, protect the rights of citizens hit by Brexit and keep the Irish border open.

They will also rubber stamp a 26-page document laying out their hopes for future relations after Britain leaves at midnight on March 29.

The last big obstacle to a deal was overcome on Saturday, when Spain lifted its objections over Gibraltar.

The deal must still be endorsed by the British parliament and EU parliament.

U.K. Parliament Seizes Thousands of ‘Potentially Explosive’ Facebook Documents

After Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg refused to testify at a joint hearing with lawmakers from seven nations over his company’s invasive privacy practices, the U.K. Parliament on Saturday legally seized thousands of secret and “potentially explosive” Facebook documents in what was described as an extraordinary move to uncover information about the company’s role in the Cambridge Analytica data-mining scandal.

According to The Guardian, the documents were initially obtained during a legal discovery process by the now-defunct U.S. software company Six4Three, which is currently suing Facebook.

Conservative MP Damian Collins, The Guardian reports, then “invoked a rare parliamentary mechanism” that compelled Six4Three’s founder—who was on a business trip in London—to hand over the documents, which reportedly “contain significant revelations about Facebook decisions on data and privacy controls that led to the Cambridge Analytica scandal. It is claimed they include confidential emails between senior executives, and correspondence with Zuckerberg.”

“This week Facebook is going to learn the hard way that it is not above the law. In ignoring the inquiries of seven national parliaments, Mark Zuckerberg brought this escalation upon himself, as there was no other way to get this critical information,” wrote Christopher Wylie, a whistleblower who was previously the director of research at Cambridge Analytica.

“The irony is… Mark Zuckerberg must be pretty pissed that his data was seized without him knowing,” Wylie added.

This is really bad for Facebook. https://t.co/hBSJRaedFm

— Matt Stoller (@matthewstoller) November 25, 2018

The U.K. Parliament’s seizure of documents Facebook has long worked to keep hidden from the public view comes as the social media behemoth is embroiled in yet another scandal, this time over its use of a right-wing public relations firm to spread anti-Semitic conspiracy theories about its critics.

“Facebook will learn that all are subject to the rule of law,” Labour MP Ian Lucas wrote on Twitter. “Yes, even them.”

NPR’s Report on Amazon Is Essentially an Infomercial

“Morning Edition’s” segment (11/21/18) on NPR-underwriter Amazon is sourced entirely to Amazon.

There are dozens of reports detailing how Amazon’s shipping policies negatively effects both the environment and workers, but one wouldn’t have any idea either was a concern after listening to NPR’s sexed-up report (Morning Edition, 11/21/18), “Optimized Prime: How AI and Anticipation Power Amazon’s 1-Hour Deliveries.”

The report, detailing the “Artificial Intelligence” behind Amazon’s delivery systems, relies entirely on interviews with Amazon flacks. The only people NPR speaks to are Brad Porter, the head of robotics for Amazon operations; Jenny Freshwater, director of software development; and Amazon VP Cem Sibay. No outside parties were sought for comment, let alone anyone remotely adversarial, such as labor organizers or environmental activists.

Indeed, the words “labor,” “worker” or “employee” are nowhere to be found in the six-minute report: Christmas packages simply deliver themselves with the help of brilliant Amazon execs and this mysterious AI technology. If Amazon’s marketing department wrote and produced a segment on their AI technology for NPR, it’s difficult to see how it would have been any different. Host Rachel Martin and correspondent Alina Selyukh all but literally exclaim “gee whiz”:

“When Amazon introduced two-day shipping, it was a huge shift in retail thinking.”

“By the time someone clicks buy on Amazon, usually [Amazon’s director of software development] had long predicted it.”

“This is key to how Amazon cuts down delivery time.”

“But it was Amazon Prime that got Americans hooked on two-day shipping. Now it’s a race for a one-hour delivery with Amazon Prime Now. Few companies can afford that, and few rely quite so much on AI [as Amazon] to control costs while growing.”

“AI is woven through it all. In the first mile, when you order, AI analyzes your search and tells you upfront how fast your item could ship…. It’s AI keeping track of all items in almost a million square feet of this warehouse. AI constantly arranges those shelves so that things you’re about to buy are ready to go.”

The only thing that comes vaguely close to criticism is when Selyukh points out that robotics are “controversial work in retail, where layoffs are rampant,” then goes on to insist:

Economists are divided on how much exactly AI will eliminate or create jobs, especially for lower-income Americans. In its defense, Amazonoften points to how much it’s actually been hiring. To [head of robotics Brad] Porter, we are in the latest chapter of industrialization.

What economists? What does “latest chapter of industrialization” even mean? NPR, using Amazon’s spokespeople and paraphrasing a nebulous cohort of “economists,” recasts “criticism,” such that it is, as a generic, sanitized critique against an industry trend presumably out of Amazon‘s control, rather than directing criticism at Amazon themselves—a employer notorious for worker abuses ranging from wage theft, Orwellian working conditions, intimidation, retaliation and union-busting.

None of these widely documented concerns—all of which make cheap two-day shipping possible—were mentioned at all. Nor were the equally well-documented environmental downsides to two-day shipping, a convenience that, despite NPR’s “oh wow, how do they do that” excitement, creates tons of gratuitous, harmful carbon emissions.

NPR did have a throwaway line about how Amazon was a “sponsor” of NPR, but it’s unclear how pointing out that the company you’re writing a press release for helped pay for the press release makes it any better. At one point, NPR’s Selyukh came so very close to making a connection between cheap, fast delivery and grinding workers down to the nub, but instead, again, threw in another AI promo:

Sibay and other Amazon executives push this illusion that fast delivery is magic. Like, the code name for Prime Now was Houdini. But the reality is [it’s] forecasting on steroids, and a meticulous shaving off of minutes and seconds on the journey of the package.

Selyukh is correct that two-day delivery isn’t “magic,” but the “reality” behind Amazon’s fast delivery time and its record-breaking $1 trillion valuation, and CEO Jeff Bezos’ record-breaking $150 billion personal fortune, isn’t just “forecasting” or smarter robotics or sexier tech (though that’s likely a small part of it), it’s what’s it’s always been: a faceless network of millions of workers—abused, neglected, overworked and underpaid—and environmental externalities the public will be mopping up for centuries. It would be good if a radio station, ostensibly set up to serve that public, could mention these inconvenient realities.

Trump’s Trade Wars Hurt Everyone in Farm Country

Agriculture is one of the largest industries in Iowa. When agriculture suffers, all Iowans do — even those who’ve never set foot on a farm.

That’s exactly what’s happening because of President Trump’s tariffs and trade wars.

When farm prices rise because of tariffs, farmers can’t buy a new pickup, purchase equipment, or make repairs. The salesperson the farmer works with doesn’t get a commission, so they spend less at home. Businesses get fewer customers, so they cut back on their workforce.

Eventually the whole economy is hurting — and so is our state.

Iowa’s lost tax revenue from personal income and sales taxes alone may range from $111 million to $146 million, Iowa State’s Center for Agricultural and Rural Development estimates. Federal offsets could reduce those losses, but not completely.

Those revenue losses can translate into additional lost labor income — anywhere from $245 million to $484 million, enough income to support 9,300 to 12,300 jobs.

Worse still, Trump’s backers in the state don’t seem to care much.

Bruce Rastetter, a major Republican donor and owner of one of the state’s major farm operations, told nervous Iowa pork producers they “just need to take a deep breath for a moment” and it’ll “all work out fine.”

Easy for him to say. Rastetter farms 14,000 acres and oversees facilities where 700,000 pigs are raised annually. Some partners listed on his website include Smithfield (China), Mano Julio (Brazil), and Fiagril (Brazil).

A deep breath won’t help the small business owners and farmers who are part of the Iowa Main Street Alliance. They’ve been sharing their stories with the Iowa Citizen Action Network.

They’re worried about crop prices, repairs, and the wrenching choice between passing the cost increase onto their customers and cutting their profit margins.

“Tariffs are even hitting businesses like mine,” said Steve Pelz, who owns a car wash in Cambridge, Iowa. “I need to have repairs done on my water heater and other machinery, but the companies I would normally use can’t supply the parts any longer due to the steel tariffs. I have had to go through other vendors and have parts retrofitted, costing me time and money.”

ReShonda Young, owner of Popcorn Heaven in Waterloo, Iowa agrees. “You might wonder how tariffs and trade wars would affect a gourmet popcorn business,” she said, “but it does. We use decorative tins for our products, particularly around the holidays, and have seen quite a price hike in these items.”

Greg and Jessica Young of Waterloo Bicycle Works recently told us that prices are going up on items they order, and invoices from suppliers are adding a line detailing the price increase due to tariff costs.

Meanwhile, communities are having issues with infrastructure projects because of price increases in necessary materials.

“For farmers, the question is where and how much of your product will you sell this year and next, and for what price?” explains Iowa State’s John Crespi. “But the harder question is what happens in two, three, or 10 years if the trade wars continue?” By then, he warns, “even if you get rid of the tariffs, the U.S. may be a smaller player.”

“An interesting déjà vu with the farm crisis of the 1980s,” Crespi adds, “is that much of the impact was linked to policies set in Washington.”

Trump markets his trade wars as an antidote to “free trade” deals that have cost jobs throughout the heartland. But in reality it’s just another broadside against a new class of workers and businesses, all to score political points.

And while they’ve cut taxes for billionaires, those GOP-backed tariffs and trade wars are just another way of taxing the rest of us here in farm country.

What Trump Doesn’t Want You to Know About the Climate Emergency

The Trump administration dropped the 1,000-page second volume of a congressionally mandated study of the impact of the climate crisis on the United States late on Friday of Thanksgiving weekend in order to bury it. This sort of move is designed to make sure the report is not headline news on the networks, newspapers and social media on Monday morning, when big-news items are seen by most Americans.

Trump and his cronies—I mean, Cabinet—are deeply invested in or beholden to ExxonMobil and other Big Carbon firms that stand to lose billions if the public realizes the harm they are inflicting on us.

The problem? If we let them go on pushing out 41 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide a year throughout the world, it is going to cost the U.S. hundreds of billion dollars a year by the end of the century. The economic contribution of entire states could be wiped out.

Unlike the unlamented Scott Pruitt’s EPA, which took down climate-crisis web pages, this report is brutally honest:

Scientists have understood the fundamental physics of climate change for almost 200 years. In the 1850s, researchers demonstrated that carbon dioxide and other naturally occurring greenhouse gases in the atmosphere prevent some of the heat radiating from Earth’s surface from escaping to space: this is known as the greenhouse effect. This natural greenhouse effect warms the planet’s surface about 60°F above what it would be otherwise, creating a habitat suitable for life. Since the late 19th century, however, humans have released an increasing amount of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere through burning fossil fuels and, to a lesser extent, deforestation and land-use change. As a result, the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide, the largest contributor to human-caused warming, has increased by about 40% over the industrial era. This change has intensified the natural greenhouse effect, driving an increase in global surface temperatures and other widespread changes in Earth’s climate that are unprecedented in the history of modern civilization.”

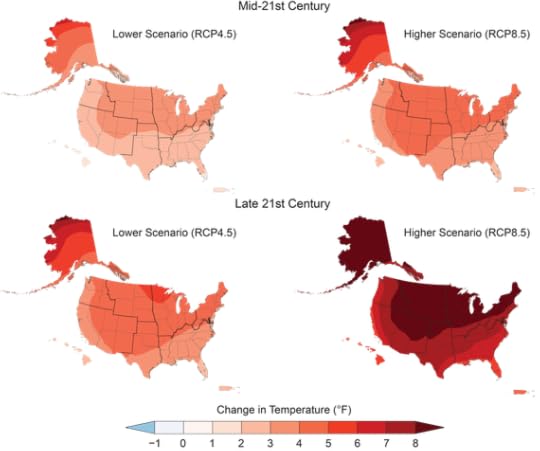

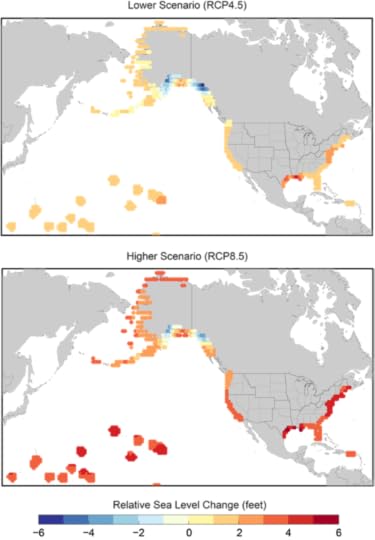

The projections of harm also pull no punches. In the worst-case scenario of current models, the Northeast and the Midwest could have an average temperature 8 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than today, with massive negative impacts on agriculture, diseases, forests and water.

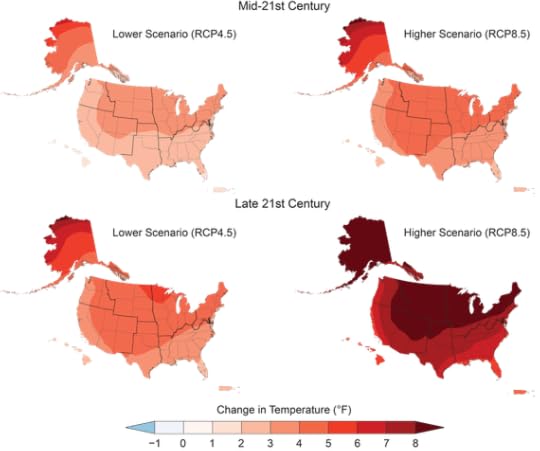

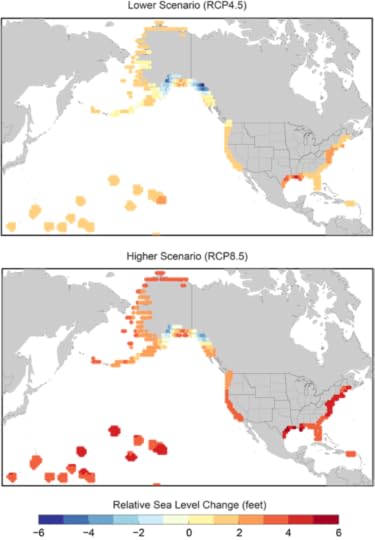

Sea-level rise of as much as 4 feet by the end of the century will subtract vast amounts of coastal property from the country, costing billions and displacing potentially millions of people. Storm surges and flooding will damage billions of dollars of infrastructure along the coasts, as well.

The extra heat will interfere with people working outdoors and will reduce man hours worked per year significantly. In other words, America is going to get much poorer, and the poor are going to be disproportionately hurt by the climate emergency.

Figure 1.21: Annual economic impact estimates are shown for labor and air quality. The bar graph on the left shows national annual damages in 2090 (in billions of 2015 dollars) for a higher scenario (RCP8.5) and lower scenario (RCP4.5); the difference between the height of the RCP8.5 and RCP4.5 bars for a given category represents an estimate of the economic benefit to the United States from global mitigation action. For these two categories, damage estimates do not consider costs or benefits of new adaptation actions to reduce impacts, and they do not include Alaska, Hawaii and U.S.-affiliated Pacific Islands, or the U.S. Caribbean. The maps on the right show regional variation in annual impacts projected under the higher scenario (RCP8.5) in 2090. The map on the top shows the percent change in hours worked in high-risk industries as compared to the period 2003–2007. The hours lost result in economic damages: for example, $28 billion per year in the Southern Great Plains. The map on the bottom is the change in summer-average maximum daily 8-hour ozone concentrations (ppb) at ground-level as compared to the period 1995–2005. These changes in ozone concentrations result in premature deaths: for example, an additional 910 premature deaths each year in the Midwest.Source: EPA, 2017. Multi-Model Framework for Quantitative Sectoral Impacts Analysis: A Technical Report for the Fourth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA 430-R-17-001.

November 24, 2018

Rain Tamps Down California Fire but Turns Grim Search Soggy

PARADISE, Calif.—The catastrophic wildfire in Northern California is nearly out after several days of rain, but searchers are still completing the meticulous task of combing through now-muddy ash and debris for signs of human remains.

Crews resumed the grim work Saturday as rain cleared out of the devastated town of Paradise. Some were looking through destroyed neighborhoods for a second time as hundreds of people remain unaccounted for. They were searching for telltale fragments or bone or anything that looks like a pile of cremated ashes.

The nation’s deadliest wildfire in a century has killed at least 84 people, and 475 are on a list of those reported missing. The flames ignited Nov. 8 in the parched Sierra Nevada foothills and quickly spread across 240 square miles (620 square kilometers), destroying most of Paradise in a day.

The fire burned down nearly 19,000 buildings, most of them homes, and displaced thousands of people, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection said.

The two-week firefight got a boost Wednesday from the first significant storm to hit California. It dropped an estimated 7 inches (18 centimeters) of rain over the burn area over a three-day period without causing significant mudslides, said Hannah Chandler-Cooley of the National Weather Service.

The rain helped extinguish hotspots in smoldering areas, and containment increased to 95 percent. Despite the inclement weather, more than 800 volunteers kept searching for remains.

Crews worked on-and-off amid a downpour Friday. While the rain made everybody colder and wetter, they kept the mission in mind, said Chris Stevens, a search volunteer who wore five layers of clothing to keep warm.

“It doesn’t change the spirits of the guys working,” he said. “Everyone here is super committed to helping the folks here.”

His search crew went home to Orange County on Saturday after completing its assignment. Authorities also lifted evacuation orders for certain sections of Paradise.

In Southern California, more residents have returned to areas evacuated in a destructive fire as crews repaired power, telephone and gas utilities.

Los Angeles County sheriff’s officials said they were in the last phase of repopulating Malibu and unincorporated areas of the county. At the height of the fire, 250,000 fled their homes.

Flames erupted Nov. 8 just west of Los Angeles and burned through suburban communities and wilderness parklands to the ocean. Three people died, and 1,643 buildings, most of them homes, were destroyed, officials said.

___

Associated Press journalists Olga Rodriguez and Daisy Nguyen in San Francisco and John Antczak in Los Angeles contributed.

Incoming Mexico Government Denies Deal to Host U.S. Asylum Seekers

MEXICO CITY—Mexico’s incoming government denied a report Saturday that it plans to allow asylum-seekers to wait in the country while their claims move through U.S. immigration courts, one of several options the Trump administration has been pursuing in negotiations for months.

“There is no agreement of any sort between the incoming Mexican government and the U.S. government,” future Interior Minister Olga Sanchez said in a statement.

Hours earlier, The Washington Post quoted her as saying that the incoming administration of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador had agreed to allow migrants to stay in Mexico as a “short-term solution” while the U.S. considered their applications for asylum. Lopez Obrador will take office on Dec. 1.

The statement shared with The Associated Press said the future government’s principal concern related to the migrants is their well-being while in Mexico. Sanchez said the government does not plan for Mexico to become a “third safe country.”

The Washington Post reported Saturday that the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump has won support from the Mexican president-elect’s team for a plan dubbed “Remain in Mexico.”

The newspaper also quoted Sanchez as saying: “For now, we have agreed to this policy of Remain in Mexico.”

Sanchez did not explain in the statement why The Washington Post had quoted her as saying there had been agreement.

The White House did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

U.S. officials have said for months that they were working with Mexico to find solutions for what they have called a border crisis.

Approximately 5,000 Central American migrants have arrived in recent days to Tijuana, just south of California, after making their way through Mexico via caravan.

Tijuana Mayor Juan Manuel Gastelum on Friday declared a humanitarian crisis in his border city, which is struggling to accommodate the influx. Most of the migrants are camped inside a sports complex, where they face long wait times for food and bathrooms.

Julieta Vences, a congresswoman with Lopez Obrador’s Morena party who is also president of Mexico’s congressional migrant affairs commission, told the AP that incoming Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard has been discussing with U.S. officials how to handle a deluge of asylum claims at the border.

“They’re going to have to open the borders (for the migrants) to put in the request,” Vences said. “They will also give us dates, on what terms they will receive the (asylum) requests and in the case that they are not beneficiaries of this status, they will have to return here,” Vences said.

She spoke to the AP after a visit to the crowded sports complex in Tijuana.

___

Associated Press writer Christopher Sherman contributed to this story from Tijuana. AP writer Colleen Long contributed from Washington, D.C.

Not Everyone Is Ready to Forgive Rebranded Iraq War Cheerleader Max Boot

In the prologue to his most recent book, “The Corrosion of Conservatism: Why I Left the Right,” Max Boot writes that leftists have unfairly accused him of “war crimes” because he, like the majority of U.S. lawmakers, supported the invasion of Iraq. But many leftists and progressives remember that he didn’t simply support the disastrous Iraq War—he helped lead the charge—and tepid remorse does not change that.

A columnist at the Washington Post, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and analyst for CNN, Boot has recently had a public epiphany in which he denounced President Donald Trump and the Republican Party, becoming, he writes, “politically homeless,” and leading to his acceptance by mainstream Democrats. Jacobin Magazine’s Branko Marcetic described Boot as “a war-hungry neocon now being approvingly retweeted by liberals.”

But Boot’s criticisms of Trump weren’t enough to win over Peter Maas, a senior editor at the Intercept, who called his apology about Iraq “disingenuous.” Maas wrote that Boot “has helped create so much havoc, he has been wrong so completely, that it would be the definition of insanity to treat his ideas as fodder for anything other than a shredder.”

In February, John Ganz wrote at the Baffler: “Boot wants to submerge himself into the center of a crowd, one of the democratic mass, when in fact he was at its vanguard, pushing for the Iraq War early and often.”

“Just like Donald Trump and most other people, I was a supporter of the war in Iraq,” Boot writes in his book, seeking safety in the majority and to preface several excuses for his actions. Even after reports surfaced in 2004 about soldiers who abused prisoners at Abu Ghraib, Boot writes, he felt the war was being mismanaged but he thought the answer was to send more troops, as though silent internal doubts were enough. He even describes “inspirational” visits to Iraq with Gen. David Petraeus. Boot echoes his arguments on the war’s 10-year anniversary, in 2013, when he wrote that there was no need to repent for supporting the war.

Now, Boot writes that “it was all a big mistake,” but he also tries to avoid responsibility, arguing that supporters of the Iraq invasion were “like hapless passengers who got into a vehicle with a drunk driver.” At least 165,000 civilians died in direct violence during the Iraq War from 2003 to 2015, and twice as many civilians died due to sickness or malnutrition that was a result of the war. For some readers, Boot doesn’t offer an apology so much as an attempt to save face.

Maas writes of Boot’s attitude toward Iraq:

The guilt that Max Boot feels—he dwells on it for less than a sentence in the entire book—does not appear to be difficult to bear. Either he doesn’t feel all that guilty for what happened, or he doesn’t realize what happened. Whichever it is, it doesn’t reflect terribly well on him.

Hawkish ideas about the invasion of Iraq are hardly Boot’s only sin, according to his critics. For example, in 1999, Boot wrote that the Supreme Court’s decision to desegregate schools in the ruling Brown v. Board of Education was unconstitutional. At Vox, senior politics reporter Jane Coaston asked why it took so long for Boot to realize the Republican Party is racist when black conservatives have been saying so for nearly half a century.

Boot writes he wishes Jeb Bush had become president and devotes a sizable portion of his epilogue to criticizing Independent Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All legislation in part because of concern about whether health insurance companies would be able to stay in business. Given Boot’s sloppy history, it seems fair to ask whether he should get any attention at all. Maas wrote:

It’s easy to understand why a penitent like Boot appeals to liberals and other members of the Trump resistance. He ratifies their sense of having been correct from the start, and his confession is enunciated in perfect sound bites, with just the right dose of abasement. Boot is an irresistible spectacle—the sinner with tears running down his cheeks dropping to his knees at the altar of all that is good, proclaiming that he has seen the light and wants to join the army of righteousness. But here’s the thing: Boot is only half-apologizing. And because he’s been wrong so many times and with so many ill consequences, he should be provided with nothing more than a polite handshake as he’s led out of the sanctuary of politics, forever.

Hospital Urges Woman to Crowdfund $10,000 for Heart Transplant Eligibility

As progressive lawmakers and healthcare experts have frequently pointed out in recent months, few growing trends have laid bare the fundamental immorality and brokenness of America’s healthcare system quite like the rise of GoFundMe and other crowdfunding platforms as methods of raising money for life-saving medical treatments that—due to insurance industry greed and dysfunction—are far too expensive for anyone but the very wealthiest to afford.

Providing the latest example of this horrifying trend, a Michigan woman seeking a heart transplant publicized a letter she received from the Spectrum Health Richard DeVos Heart and Lung Transplant Clinic—named after the late father-in-law of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos—informing her that she is “not a candidate” for the procedure “at this time” because she needs a “more secure financial plan” to afford the required post-operation immunosuppressive medication.

The letter goes on to explicitly recommend “a fundraising effort of $10,000” to help pay for the drugs.

Hedda Elizabeth Martin, who posted the letter on Facebook, wrote that her situation encapsulates America’s “price gouging, horribly overpriced, underinsured system,” which affects millions each day in the richest country on Earth.

The letter, which Martin received shortly before Thanksgiving, began to go viral on Saturday and quickly caught the attention of progressives like Rep.-elect Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), who identified Martin’s situation as indicative of the broad failure of America’s healthcare status quo—which produces tremendous profits for insurance and pharmaceutical giants and worse outcomes than the healthcare systems of other industrialized nations.

“Insurance groups are recommending GoFundMe as official policy—where customers can die if they can’t raise the goal in time—but sure, single-payer healthcare is unreasonable,” Ocasio-Cortez, an unabashed supporter of Medicare for All, wrote sarcastically.

Insurance groups are recommending GoFundMe as official policy – where customers can die if they can’t raise the goal in time – but sure, single payer healthcare is unreasonable.

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@Ocasio2018) November 24, 2018

h/t @DanRiffle pic.twitter.com/zetPW0MgDd

Jokes about how GoFundMe is becoming an integral part of our insane health insurance system are no longer funny. pic.twitter.com/47DrOXsc1r

— Every billionaire is a policy failure (@DanRiffle) November 24, 2018

Anyone that thinks this is okay needs a heart transplant because, clearly, they don’t have one themselves. This is immoral & not okay. We need the #NewYorkHealthAct now. #MedicareForAll @NYHCampaign @justicedems #NYHA @SenGianaris @NYSenatorRivera @SalazarSenate @Biaggi4NY #DSA pic.twitter.com/XcSQ5V0ZOR

— Dan Radzikowski (@DanRadzikowski) November 24, 2018

Imagine being told you cant have a new heart because a panel doesn't believe you can cough up $10,000. #MedicareForALL https://t.co/KTBSKkFsZj

— Derrick Crowe

American History for Truthdiggers: A Savage ‘War to End All Wars,’ and a Failed Peace

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 22nd installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 22 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16; Part 17; Part 18; Part 19; Part 20; Part 21.

* * *

“Over there, over there, / Send the word, send the word over there. / That the Yanks are coming, / the Yanks are coming … / We’ll be over, we’re coming over, / And we won’t come back till it’s over, over there.” —An excerpt from George M. Cohan’s song “Over There”

America wasn’t supposed to get in the war. When the country finally did, it was to be a war “to end all wars,” to “make the world safe for democracy,” one in which, for once, the Allies would seek “peace without victory.” How powerful was the romantic and idealistic rhetoric of Woodrow Wilson, America’s historian and political scientist turned president. None of that came to pass, of course. No, just less than three years after the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914, the working classes of the United States would join those of Europe in a grinding, gruesome, attritional fight to the finish. In the end, some 116,000 Americans would die alongside about 9 million soldiers from the other belligerent nations.

Today, the American people are quite comfortable with the mythical sense of their role in the second of the two world wars. The Nazis had to be stopped at all cost; the Japanese had deceitfully attacked our fleet; and—in the end—America saved the day. The U.S. thus became, as a popular T-shirt proclaims, “back-to-back” world war champs. Still, most of the citizenry knows little about the First World War, which was once called the Great War. The issues involved and the reasons for fighting seem altogether murky, messy even. So, as a simple patriotic heuristic, Americans tend to frame the First World War as a prelude to the second. Not simply in the sense that one led in some way to the next, but that the German enemy was equally evil in each—that the kaiser in 1917 was only slightly less militaristic than Adolf Hitler in 1941. Germany’s race for world domination, we vaguely conclude, really began in the second decade of the 20th century and wasn’t fully thwarted until 1945. None of that is strictly true: The kaiser’s government was far more complex than that of Nazi Germany, for example, and a German sense of guilt over the war was more collective in 1914 than 1939—but the legend of the war and America’s role in it can more easily be simplified by use of this mental shorthand.

In reality, Europe blundered into war because of a mix of absurd factors that undergirded the entire nation-state and imperial system of the day: jingoistic nationalism, the race for Asian and African empires, a destabilizing series of opposing alliances, and the foolish notion that war would rejuvenate European manhood and, of course, be swift, decisive and brief. Instead, technological advances outran military tactics and the two sides—Germany, Austria and Turkey on the one hand and Britain, France and Russia on the other—settled in for an incomparably brutal war of stagnation and filth. Unable to win decisively on either front, both sides dug in their men, artillery and machine guns and fought bloody battles for the possession of mere meters of earth. It was to be the war that ultimately “finished” Europe, destroying the long-term power of the continent and ultimately shifting leadership westward to the United States. Not that any of this was clear at the time.

Europe lost an entire generation, killed, maimed or forever psychologically broken by the war. Many Europeans lost faith in the snake oil of nationalism and turned away from the standard frameworks of monarchy or liberal democracy. Some found solace in socialism, whereas others doubled down on ultranationalism in the form of fascist leaders. Despite 9 million battle deaths—a number unfathomable when the war began—WWI solved little and sowed the seeds for the European cataclysm of 1939-45. It is an uncomfortable truth, especially for the United States, a nation that tends to see itself as being at the center of the world; the U.S. played mostly a late, and bit, part in the drama across the Atlantic. However, the populace believed its own propaganda, crafted a myth of American triumphalism and learned all the wrong lessons from the war. Instead of being a “war to end all wars,” the Great War turned out to be just the beginning of American interventionism—the pivot toward the creation of today’s fiscal-military hegemonic state. And it didn’t have to be that way.

Getting In: Wilson Takes Us to War

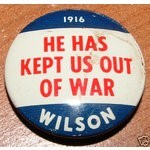

A 1916 campaign button for the re-election of Woodrow Wilson. Within weeks of his second inauguration, the president, declaring “[t]he world must be made safe for democracy,” would successfully ask Congress to approve U.S. entry into World War I.

Most Americans were horrified by the brutality of trench warfare in Europe and thanked God for the Atlantic Ocean. A majority in the U.S., due to cultural and linguistic ties to Britain, favored the Allies. Still, another segment of the population, German-Americans and the viscerally anti-British Irish-Americans, tended to favor Austria and Germany. So, while President Wilson advised the people and his government to be “neutral in fact as well as in name … impartial in thought as well as action,” genuine neutrality was always a long shot. One of the problems was Wilson, himself, who began to see the war as an opportunity for the United States to lead “a new world order.” If he could do so as a peaceful arbiter, so be it; if it required America’s entry into the fields of fire, well, perhaps that couldn’t be avoided.Only William Jennings Bryan, Wilson’s first secretary of state and a three-time Democratic presidential nominee, could be considered a truly neutral voice in the Cabinet. “There will be no war as long I am Secretary of State,” the legendary firebrand thundered upon joining the administration. He felt obliged to resign barely a year later, and the U.S. slid toward war. Of course the U.S. had never been strictly neutral. Close economic ties with the Allies ensured that. Rather than embargo both sides or demand that Britain open its starvation blockade of Germany to U.S. trading vessels, Wilson’s government exported hundreds of millions of dollars in goods annually to the Allied nations and funded some of their debts. In just the first eight months of the war, U.S. bankers extended $80 million in credits to the Allies, and then, after Wilson lifted all bans on loans, U.S. financial interests would float $10 million per day to Britain alone! By the end of the war, the Allies owed $10 billion in war debts to the U.S., the equivalent of some $165 billion in today’s dollars. Indeed, the U.S. economy had by 1917 come to rely on Allied war orders. How would Wall Street recover these debts if not through Allied victory? And how could the bogged-down Allies defeat Germany without the promise of American troop reinforcements?

Furthermore, Wilson acquiesced to Britain’s blockade of Germany. He told Bryan it would be “a waste of time” to argue with Britain about the blockade, but this made the U.S., in fact if not in name, a partner of the Allies. German officials, with some sound logic, protested that the U.S., if truly neutral, would condemn a British blockade that starved European children. Wilson remained silent.

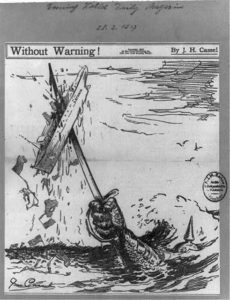

“Without Warning!,” a 1917 cartoon in the Evening World Daily Magazine, depicts a sword rising from the sea to destroy a U.S. merchant vessel. Above the waves can be seen part of a German helmet. Such cartoons proliferated after the sinking of the luxury liner Lusitania in 1915.

His voice was quite clear, however, on the subject of German submarine warfare against Allied (namely American) shipping. Though the German navy had been built up in the decades before the war, its battleships and cruisers were still no match for the combined Anglo-French fleets. Therefore, in order to stymie the blockade and attrit the Allied supply lines, the Germans turned to submarine or “U-boat” warfare. Indeed, at certain points during the war, the German U-boats nearly brought the Allies to their logistical knees. It was only American distribution that kept Britain, in particular, afloat. The German government spent much of the conflict at war with itself over whether or not to sink American merchant ships supplying the Allies. One can, after all, understand the German predicament: Allied naval power was isolating the Central Powers and the Americans were economically allied with Britain and France!

When, however, a German sub sank the British luxury liner Lusitania in May 1915, killing more than 120 U.S. citizens, there was a great outcry from Americans. Former President Theodore Roosevelt, always a reliable war hawk, called the attack “murder on the high seas!” He was still a popular figure, after all, so his demand for war in response to German “piracy” was a serious matter. It turned out the Lusitania, traveling from the United States to Britain, was carrying 1,248 cases of three-inch shells and 4,927 boxes of rifle cartridges. The British had put the American passengers at risk as much as the Germans did. In response, in one last plea for “real neutrality,” Secretary Bryan called for calm and stated, “A ship carrying contraband, should not rely on passengers to protect her from attack—it would be like putting women and children in front of an army.” When Wilson failed to sufficiently curtail warlike rhetoric, Bryan tendered his resignation. With him may have gone any real chance at U.S. neutrality.

The British, to be fair, had also contravened America’s “neutral rights” throughout the war. They upheld the blockade, denied the U.S. the ability to easily trade with Germany, and even went so far, in July 1916, as to blacklist 80 U.S. companies that allegedly (and legally) traded with the Central Powers. Furthermore, key immigrant communities in the U.S. were appalled by Britain’s forceful put-down of Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rebellion for independence and the subsequent execution of rebel leaders. Wilson, weak protestations aside, gave in to London at every turn.

Initially, Germany promised no further surprise attacks on passenger vessels and American merchant ships, but as the war ground on, German Chancellor Theobald Bethmann-Hollweg faced a decision between submission, on one hand, and utilizing the U-boats to their fullest, on the other. Fatefully, it turned out, the German military forced Hollweg’s hand and Berlin declared “unrestricted submarine warfare” in early 1917. This was not the only affront to American prestige. In late February 1917, the British leaked a German message—the famous Zimmerman telegram—seeming to offer an alliance with Mexico and the potential for the Mexicans to “reconquer its former territories in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.” Despite the truth that Washington had, indeed (probably) illegally conquered the region and turned northern Mexico into the Southwest United States in the 1840s, Americans were in no mood for subtleties, and anti-German sentiment exploded across the country. It was to be war.

Still, this outcome was never inevitable. Germany sought not to conquer the world, but to win—or at least honorably extract itself from—a stagnant and costly European war. Nor should the reader give in to the (mostly false) notion that Germany was an authoritarian, brutal Nazi-like dictatorship, while the Allies were liberal democrats. Austria was a dual monarchy, but Germany had a mixed government with a royal kaiser but also a parliament and one of the most progressive social welfare systems in the world. Besides, Russia—a key country in the Triple Alliance—was perhaps the most backward, largely feudal, monarchy on the planet. Furthermore, as the famed progressive Sen. Robert La Follette of Wisconsin reminded Americans as he cast a vote against Wilson’s April 2, 1917, call for war, Britain and France possessed their own global empires. In that sense, the U.S. merely sided with one set of flawed empires over another. La Follette exclaimed on April 4th that “[Wilson] says this is a war for democracy. … But the president has not suggested that we make our support conditional to [Britain] granting home rule to Ireland, Egypt, or India.” The man had a point.

Nevertheless, Wilson’s request for a war declaration passed the Congress and mobilization began. The president stood before the legislature and claimed the U.S. “shall fight for the things we have always carried nearest to our hearts—for democracy … for the rights and liberties of small nations. … We have no selfish ends to serve.” Wilson was only formalizing a millenarian message he had been spreading for years. In 1916, in a speech one historian has called “at once breathtaking in the audacity of its vision of a new world order” and “curiously detached from the bitter realities of Europe’s battlefields,” Wilson declared that America could no longer refuse to play “the great part in the world which is providentially cut out for her. … We have got to serve the world.” And so it was, whether in the interest of “serving the world,” or backing its preferred empires and trading partners, the U.S. would enter its first war on the European continent. It would not be the last.

Over There: America at War

The United States may have been an economic powerhouse holding most of the financial cards in the deck, but its military was woefully unprepared for war on the scale of what was being waged in Europe by 1917. Though some limited preparations began with the 1916 National Defense Act—which gradually raised the size of the regular Army to 223,000 men—the U.S. military remained tiny (only the 17th largest worldwide) compared with those of the belligerent nations. After all, the combined German and French fatalities at a single battle—Verdun in 1916—exceeded the total dead of the U.S. Civil War, still the bloodiest conflict in American history.

Meanwhile, the Germans nearly won the war before the U.S. could meaningfully intervene. After the 1917 Russian Revolution turned communist, the new Russian leader, Vladimir Lenin, made a humiliating peace with Berlin. The Germans now shipped dozens of divisions westward and attempted one last knockout blow against the British and French on the Western Front. And, since President Wilson and the leading U.S. Army general, John J. Pershing, insisted that American soldiers fight under an independent command, it took many extra months to raise, equip and train an expeditionary force. It took more than a year before the U.S. could muster even minimal weight at the front. Nonetheless, the British and French lines (just barely) held in early 1918, and the infusion of 850,000 fresh, if untested, American troops helped make possible an Allied summer counteroffensive that eventually broke the German front lines.

It was all over by Nov. 11, 1918 (once called Armistice Day, now celebrated as Veterans Day in the U.S.), when the Germans agreed to an armistice in lieu of eventual surrender. Still, when peace came, the German army largely remained on French soil. There was no invasion of Germany, no grand occupation of the capital. The end was nothing like that of the next world war. To many German soldiers and their nationalist proponents at home, it seemed that the army had been sold out by weak civilian officials—especially the socialists (and Jews) in the government. This belief, along with the later insistence by the Allies on a harsh retributive treaty at Versailles, sowed the seeds for the rise of fascism, ultranationalism and Hitler in 1930s Germany.

When all was said and done, the U.S. had suffered just 116,000 of the 9 million battle deaths of the war. Despite collective American memories of Uncle Sam going to the rescue, an honest reflection requires admission that it was Britain and France—which together had suffered roughly 2 million dead—that won the war for the Allies. The U.S. was a latecomer to the affair, and while its troops helped overrun the German lines, Berlin was cooked as soon as its spring offensive failed in 1918. The United States had hardly saved the day. It was a mere associate to Allied victory. Such humility, though, tends not to suit Americans’ collective memory.

Over Here: War at Home and the Death of Civil Liberties

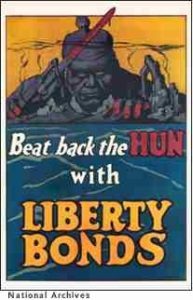

An ad encouraging Americans to buy war bonds to help defeat the “Hun,” a pejorative term for Germans.

The war that Wilson claimed was being waged to make the world “safe for democracy” forever changed and restricted American civil liberties. It strengthened a fiscal-military federal state that shifted to a war footing. Every single facet of Americans’ lives was now touched by the hand of federal power. First off, the war required a mass military mobilization. The era is often remembered for its intense public patriotism, but, when only 73,000 men initially volunteered for the military, the government brought back conscription for the first time since the Civil War and drafted nearly 5 million men from 18 to 45 years old. Some noted progressives got carried away with the idea of federal power and regulation. “Long live social control!” one reformer enthusiastically wrote. Another wing of anti-war progressives wasn’t so sure. The longtime skeptic Randolph Bourne—who noted with distaste that “[w]ar is the health of the state”—worried that most progressives were allying themselves with “the least democratic forces in American life.” He concluded, “It is as if the war and they had been waiting for each other.” And, throughout history, so often they have been.

The government first sought to control the economy and ensure that American business was placed on a war footing. The War Industries Board (WIB) regulated the production of key war materials through a combination of force and negotiation with the “captains of industry.” Though the WIB quickly transitioned the U.S. to a war economy, one the organization’s own leaders, Grosvenor Clarkson, described the potential dark side of such a system: “It was an industrial dictatorship without parallel—a dictatorship by force of necessity and common consent which … encompassed the Nation and united it into a coordinated and mobile whole.” Additionally, Wilson’s government needed to get control of the country’s proliferating labor unions to ensure a smooth economic war machine. His National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) attempted to mediate disputes between capitol and labor. It never really worked. Strikes continued and even grew throughout the war years, and the NLRB—with the backing of police, militia and federal troops—worked overtime to quash workers’ demands. The result was a sense of national need over individual freedom. George Perkins, a top aide to financier J.P. Morgan, caught the mood when he exalted that “[t]he great European war … is striking down individualism and building up collectivism.” It would do so in industry, and also in culture and politics.

Though waves of patriotism and anti-German anger swept the nation, many Americans—especially the ethnic Irish and Germans and a broad swath of Midwesterners—remained skeptical of the war. Furthermore, this was an era of strong socialist (anti-war) power in American politics. The Socialist Party candidate for president in 1912, the former union leader Eugene Debs, had, after all, won nearly a million popular votes. As surprising as this sounds at present, 1,200 socialists held political office in the United States in 1917, and socialist newspapers had a daily readership of some 3 million citizens. For all his external rhetoric about peace, liberty and democracy, President Wilson wasn’t taking any chances at home. He and his congressional supporters delivered a propaganda machine and civil liberty curtailments unparalleled in the annals of American warfare. Indeed, Wilson was obsessed with sedition and disloyalty, warning, “Woe be to the man or group that seeks to stand in our way. …” And he and his Congress were willing to back up such threats with action.

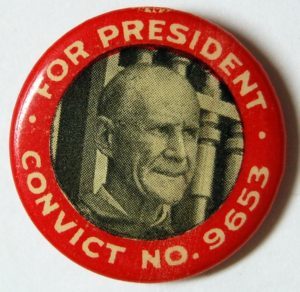

A campaign button for Eugene Debs, the Socialist Party candidate for president in 1920. Though he ran from federal prison he received over 900,000 votes.

In 1917-18, Congress passed the Espionage and Sedition Acts. In a sweeping violation of Americans’ constitutional rights, for example, the Sedition Act declared illegal “uttering, printing, writing, or publishing any disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive language about the United States government or the military.” Apparently, this applied to any criticism of the draft. Thus, when Eugene Debs spoke critically, and peaceably, about the war outside a conscription office, he was arrested and later sentenced to 10 years in federal prison. Standing before the judge at his sentencing, Debs made no apologies, asked for no leniency and uttered some of the most beautiful words in American history: “Your honor, years ago I recognized my kinship with all living beings, and I made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. … I say now, that while there is a lower class, I am in it; while there is a criminal element, I am of it; while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

Debs was not alone. Some 900 people were imprisoned under the Espionage Act—which is still on the books—and 2,000 more were arrested for sedition, mainly union leaders and radical labor men such as members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or “Wobblies.” Appeals to the Supreme Court failed; all branches of government, it seemed, were complicit in the curtailment of standard civil liberties. Interestingly, the now aged Espionage Act was used extensively by the Obama administration to charge journalists, as well as Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden. What’s more, over 330,000 Americans were classified as draft evaders during World War I, and thousands of them, mostly conscientious objectors, were forced to work in wartime prison camps, such as the one at Fort Douglas, Utah, for the duration. Finally, even the mail was restricted, with the postmaster general refusing to deliver any socialist or anti-war publications and materials.

Wilson also needed a government propaganda machine to drum up support for the war, especially among apathetic Midwesterners, socialists and so-called hyphenated Americans. He found his answer in the Committee for Public Information (CPI), which, led by the journalist George Creel, employed social scientists and greatly exaggerated German atrocities to motivate the public. The CPI employed 75,000 speakers and disseminated over 75 million pamphlets during the war years. One social scientist bragged that wartime propaganda was designed to create a “herd psychology,” and philosopher John Dewey referred to the methods as “conscription of thought.” Fact, it seemed, was secondary to results, and the preferred outcome was a united, anti-German public ready to fight and die both in the trenches abroad and for “patriotism” at home.

Not all Americans were willing to acquiesce to this state of affairs, and some wrote critically of the wartime climate in the United States. One Harvard instructor complained, “With the entry into the war our government was practically turned into a dictatorship.” Furthermore, the journalist Mark Sullivan maintained that “[e]very person had been deprived of freedom of his tongue, not one could utter dissent. … The prohibition of individual liberty in the interest of the state could hardly be more complete.” The effect fell worst on German-Americans and Southern blacks.

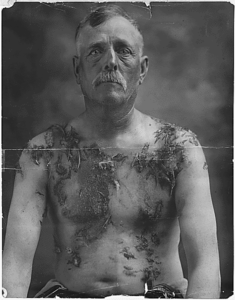

John Meints, a German-American who farmed in Minnesota, is shown after being tarred and feathered in 1918. The vigilantes who brutalized him were celebrated in the press, and no one was ever prosecuted.

The problematic results of all this were altogether predictable. Hypernationalist Americans, treated to lies and exaggerations about their German enemies, began to take matters into their own hands and to police “loyalty” at home. Across the country, 250,000 citizens officially joined the American Protective League (APL) while many more joined informal militias. APL members opened mail and bugged phones to spy on suspected “traitors.” These excesses also infected the culture and language in a number of ludicrous ways. German-sounding words were Americanized or renamed. Hamburger became Salisbury steak, sauerkraut was changed to “liberty cabbage” and the German measles was rechristened the “liberty measles.” (One is reminded of french fries being renamed “freedom fries” when France refused to back the United States’ 2003 invasion of Iraq.)

Such farce aside, the actions of the APL and unofficial militias quickly got out of hand and often turned violent. Americans suspected of disloyalty were taken to public squares and forced to kiss the flag or buy liberty bonds. Others were brutally tarred and feathered or painted yellow. One German-American, Robert Prager, was hanged by a mob in Illinois. In response to the incident the supposedly liberal Washington Post reported, “In spite of the excesses such as lynching, it is a healthful and wholesome awakening in the interior of the country.”

African-Americans also, predictably, suffered during the war, both in terms of humiliation and physical attacks. The famed civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois predicted at the start of the war that “[i]f we want real peace, we must extend the democratic ideal to the yellow, brown, and black peoples.” That proved to be a bridge too far. In the Army, blacks served in segregated units and, ironically, found wartime France much more hospitable and egalitarian than the American South. Many never returned home. Those who did so returned to a country beset with race riots. Dozens of blacks and others were killed in riots in Chicago, East St. Louis and 25 other cities. At the same time, a new manifestation of the Ku Klux Klan—now concerned with not only blacks but immigrants, Jews and Catholics—grew in numbers. This expansive version of the Klan operated publicly and even controlled many political offices during the period. Lynching exploded across the South: 30 black men in 1917, 60 in 1918, 76 in 1919—including 10 war veterans, some still wearing their uniforms. It seemed that the American South could not bear the sight of “uppity” blacks returning home as “men” wearing the uniform of the U.S. Army.

The war’s end also broke the back of the then-powerful American Socialist Party. After the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, the U.S. government helped foment a veritable “Red Scare,” an illogical fear of all speech and action on the American left. One observer noted, “Not within the memory of living Americans, nor scarcely within the entire history of the nation, has such a fear swept of the public mind. …” During the scare, which reached a peak in 1920, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer created the General Intelligence Division, led by a young and zealous J. Edgar Hoover (later the longtime head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation). In the federal counterattack that followed, 4,000 supposed “radicals” were arrested, and hundreds were stripped of their citizenry and shipped to the Soviet Union. It was the death knell not only of American socialism but also of the more liberal and skeptical brand of progressivism. Randolph Bourne would see the future clearly in the midst of the war. “It becomes more and more evident that, whatever the outcome of the war, all the opposing countries will be forced to adopt German organization, German collectivism, and [to indeed shatter] most of the old threads of their old easy individualism,” he wrote, continuing on to say that “[Americans] have taken the occasion to … repudiate that modest collectivism which was raising its head here in the shape of the progressive movement.” Bourne was right: Progressivism—for now—was dead. It, along with 116,000 American men and a handful of American women, was killed by the war.

Men like Eugene Debs and Randolph Bourne, along with other skeptics, were ahead of their time. They realized a universal truth that applied then as well as now. Things are lost in war—freedom, liberties, individualism. Some are never recovered. That, along with battlefield triumphs, must define the American experience in the Great War.

The Seeds of the Next War: Wilson, Versailles and the Road to WWII

The manner in which the First World War ended helped sow the seeds for a second world war. Though Wilson personally brought his sense of America’s special destiny to the peace conference at Versailles, France, and despite his wide popularity among the masses of Europe, he was unable to craft the treaty and postwar world he desired. Indeed, his idealistic, and perhaps naive, sense of American duty and interventionism, which has ever since been labeled “Wilsonianism,” has never really left the scene in America. The realpolitik-minded Allied leaders of Britain, France and Italy were in no mood for lectures on democracy and human rights from Mr. Wilson. Given his personal popularity, and America’s latent power, they appeased him to some extent, but that was all.

Even though he stayed in Europe for six full months, Wilson’s preferred peace would not come to pass. Despite the romantic liberty-rhetoric of his so-called Fourteen Points, the president was forced to accede to the Allies on key elements that would poison the well of peace. Germany, in the “war guilt” clauses of the treaty, was held solely responsible for the outbreak of war. Berlin was also saddled with a crippling war debt and forced to compensate the victorious Allies with territory and enormous sums of cash for decades to come. Adolf Hitler would play on Germans’ (sometimes legitimate) grievances regarding these matters to rise to power decades later. So much for “peace without victory.”

On issues of colonialism, too, Britain and France were never willing to play ball. They sought perpetuation and even expansion of their empires (at the expense of Germany, of course) in Asia and Africa. So died Wilson’s promises of a war for the “rights of small nations.” Britain and France carved up the old Ottoman Empire and redrew lines in the Middle East that to this day contribute to disorder and civil war. When the Allies rejected Japan’s proposal for a “racial equality” clause in the treaty, the ministers of that nation—a member of the Allied war against the Central Powers—nearly walked out. Eventually they did leave, with lasting resentments that would come back to haunt the U.S. and the other Allies in the Pacific.

Many representatives from colonial nations had placed an enormous amount of trust in Wilson. Never trusting the tainted imperial governments of Britain and France, these unofficial peace delegates hoped that Wilson’s Fourteen Points would save them. A young French-educated Vietnamese man named Ho Chi Minh was unable to even gain entrance to the proceedings. He would not forget, and 40 years later emerged as an anti-colonial guerrilla leader. Furthermore, when it became clear that the European colonies would not receive postwar home rule, riots and protests erupted in India, Egypt and China. Observing this, and commenting on the failures of the Treaty of Versailles, a young library assistant named Mao Zedong—later the leader of China’s communist revolution—protested, “I think it is really shameless!”

Russia, because it was communist, was excluded from the conference. In fact, in an episode lost to U.S. (but not Russian) history, 20,000 U.S. troops joined many more other Allied soldiers in an occupation of parts of Russia, backing the non-communist “White” Russian armies in their failed attempt to overthrow “Red” power. The Soviet government and its successor state, the Russian Federation, now led by Vladimir Putin, would never forgive the West for this perceived transgression.

Still, President Wilson hoped that the new League of Nations—the deeply flawed precursor to the United Nations—would achieve what the basic contours of the treaty could not. Wilson took these matters personally and embarked on a nationwide tour of American cities to sell the treaty and league to a citizenry (and Congress) increasingly skeptical of international involvement. Wilson asked the people, “Dare we reject it [the treaty] and break the heart of the world?” But Americans did reject it, as would their representatives in the Senate, where it lost by seven votes. The U.S. would sign a separate peace treaty with Germany and declined to join the now-weakened League of Nations. By this time Wilson, having suffered strokes—including a final one that paralyzed half his body—was nearly an invalid. His advisers and wife would keep his medical condition a secret from the American public, remarkably, nearly to the end of his second term.

Perhaps a more equitable, or Wilsonian, peace treaty would have assuaged German shame and avoided the rise of Hitler. Beyond that, one must wonder whether a swift, limited German victory—along the lines of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71)—might also have avoided the catastrophe of Hitler and the Second World War. And then there is the matter of America’s “retreat” from Europe after declining to join the League of Nations. Could U.S. involvement and leadership have avoided the rise of fascism and outbreak of conflict in Eastern Europe and the Pacific? In truth, these questions—counterfactuals really—are unanswerable. Still, they are important to consider. What is certain is that Allied imperialism survived for 40 to 50 years, leading to outbreaks of left-leaning guerrilla wars in the 1950s and ’60s; European nationalism remained a major factor, contributing to the rise of its most extreme form, fascism; and American “Wilsonianism” emerged from the war as a still powerful force in U.S. foreign policy, guiding a full century’s worth of (ongoing) American worldwide military interventionism.

* * *

Historians continue to argue whether the Great War was the culmination or the death knell of progressivism. In a sense it was both. Indeed, the use of an activist, empowered federal government to rally the populace and control the people that World War I personified was always the dream of one strand of progressives. Yet, in the end, we must conclude that war—and its domestic excesses—destroyed the foundation of the progressive movement. The citizenry had tired, temporarily at least, of big government and federal interventions at home and abroad. The progressive push for a stronger, European-style social democracy withered just as swiftly as the Treaty of Versailles itself. In the election of 1920, the Republican Warren G. Harding swept to victory on a platform of a return to “normalcy,” and two straight conservative, business-friendly Republican administrations followed. As the progressive warrior Jane Addams had warned when the U.S. entered the war, “This will set back progress for a generation.” How right she was.

Those three presidents—Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover—would, it must be said, keep the U.S. out of any major international war, but they would also crash the economy and dismantle the social safety net, paving the way for the Great Depression. And though the policy of “isolationism,” which actually personified the views of George Washington and more than 150 years of American tradition, briefly flourished between the wars, it would eventually become a pejorative term. When war again brewed in Europe, partly because of the way the Allies mishandled their “victory” and negotiation of the “peace,” most Americans and their leaders were able to fall back on their comfortable myth of the U.S. having “saved the day” in 1917-18. Forgotten were the last war’s horrors, the domestic excesses of the warfare state, and the once prevalent (if vanquished) anti-war movement that had flourished not 30 years in the past.

Americans believe their own lies—the lies they are told and those they themselves craft. And the U.S. has failed to see through its falsehoods about the Great War even though a century has passed since it ended. Its sense of messianic destiny and unparalleled accumulation of military power is such that—as the world celebrates (or mourns) the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I—the U.S. alone still views that conflict in heroic terms. Americans, at least the 1 percent willing to volunteer to go to a war and the numerous policymakers ready to send them off, still stand ready, as the song said, to go “over there.” Only now everywhere is over there and American hubris appears to know no bounds. And, one could argue, it all began with the fictions we told ourselves about America’s experience in World War I—and more’s the pity.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works: