Chris Hedges's Blog, page 342

February 6, 2019

What Labor Activists Can Learn From the Seattle General Strike

Seattle shipyard workers in 1919 as they walk off the job.

Seattle shipyard workers in 1919 as they walk off the job.Museum of History & Industry, CC BY

Steven C. Beda, University of Oregon

It shut down a major U.S. city, inspired a rock opera, led to decades of labor unrest and provoked fears Russian Bolsheviks were trying to overthrow American capitalism. It was the Seattle General Strike of 1919, which began on Feb. 6 and lasted just five days.

By many measures, the strike was a failure. It didn’t achieve the higher wages that the 35,000 shipyard workers who first walked off their jobs sought – even after 25,000 other union members joined the strike in solidarity. Altogether, striking workers represented about half of the workforce and almost a fifth of Seattle’s 315,000 residents.

Usually, as a historian of the American labor movement, I have the unfortunate job of telling difficult stories about the decline of unions. However, in my view, the story of this particular strike is surprisingly hopeful for the future of labor.

And I believe it holds lessons for today’s labor activists – whether they’re striking teachers in West Virginia or Arizona, mental health workers in California or Google activists in offices across the world.

Low wages, soaring living costs

The Seattle General Strike had its origins in the city’s many shipyards.

During World War I, workers flocked to Seattle to take jobs as welders, pipefitters, riveters and other dozens of jobs in the early-20th century shipyard. In 1918, there were about 16,000 shipyard workers in Seattle. Just a year later, their numbers had swelled to 35,000.

While work in the shipyards was plentiful, it wasn’t exactly lucrative. Throughout World War I, workers continually demanded wage increases, and employers routinely ignored them. As rents and the cost of living climbed, the workers finally announced that, absent higher wages, they were going on strike on Feb. 6.

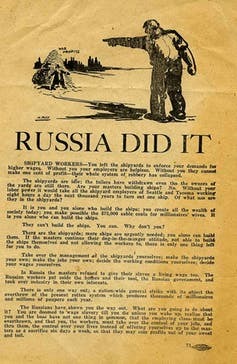

Many blamed Russian Bolsheviks for the strike.

Many blamed Russian Bolsheviks for the strike.Tothebarricades.tk, CC BY

A few days before the deadline, the shipyard unions made a then-unprecedented request: They asked the Seattle Central Labor Council – which oversaw most of the city’s unions – to issue orders for a general strike, which brought out 25,000 cooks, waitresses, factory workers, store clerks and many others to join the 35,000 shipyard workers already striking.

Despite the usual divisions within unions along lines of race, gender, skill and citizenship, the majority of the locals belonging to the council voted to join the strike.

‘No one knows where’

Perhaps it was the rising cost of living that motivated workers across the city to walk off their jobs. Maybe it was a new culture of working-class solidarity emerging in post-World War I America.

Most certainly, it had much to do with the words of Anna Louise Strong.

A pacifist, feminist and welfare advocate, Strong made a name for herself reporting for Seattle’s Union Record, the major union newspaper in the city.

An editorial she authored on Nov. 4 encouraged Seattle’s workers to put aside their differences and embrace a new future in which all workers were united. Her editorial ended with what would become iconic lines in American labor history: “We are starting on a road that leads – NO ONE KNOWS WHERE!”

Strong’s point was to promote unity among Seattle’s workers, not advocate revolution, though that’s not how many politicians interpreted it. The Russian Revolution two years earlier still weighed on the minds of the city’s elite and many worried that Strong’s editorial was the opening salvo in a war to overthrow American capitalism.

Police set up a mounted machine gun during the strike.

Police set up a mounted machine gun during the strike.The Town Crier Newspaper, CC BY

The violence that never come

Fearing violence, anti-labor organizations and the city’s politicians peppered the streets with pamphlets warning that Bolsheviks were behind the strike. Newspapers as far away as New York picked up Strong’s editorial and ran sensational stories of the strike that stoked alarm over a rising tide of radicalism.

While Seattle did lurch to a halt, the violence that Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson and others feared never came. Hanson called on the police force to maintain order in the city, through violence if necessary, and asked the governor to mobilize the National Guard. He even paid students from the University of Washington to patrol the streets.

But in the words of Earl George, a striking dockworker who went on to became the first African-American president of Seattle’s longshoremen’s union, “Nothing moved but the tide.”

What George and workers remembered as they walked away from their jobs was the peacefulness of the city. And with shops and restaurants closed due to the strike, the workers themselves pitched in to provide essential services, such as stocking food banks and washing sheets at hospitals.

A teacher at a public school in Denver participates in a march in January.

A teacher at a public school in Denver participates in a march in January.AP Photo/David Zalubowski

The power of solidarity

What ultimately ended the strike, on Feb. 11, was the very thing Strong warned against in her editorial: divisions among workers.

Unions representing skilled workers began to fear that the general strike was undermining their prestige and began ordering members back to work. Other unions succumbed to the threats being made by Hanson and returned to their jobs.

In purely material terms, the strike was a failure. It also directly contributed to a new wave of repression and the “red scare” of the post-World War I era.

Yet, the strike was not without meaning. It’d proven to workers, both in Seattle and elsewhere, that there was power in unity, however fleeting. For five days, workers had shut down the city and then run it themselves.

For today’s workers tired of decades of wage stagnation and fleeting benefits in the gig economy, the Seattle General Strike offers an important lesson about the power of organized laborers: When united, workers can take on the most powerful foes.

Striking teachers, activists at Google and participants in the Women’s March, to name just a few examples, are today standing on the same road that Anna Louise Strong described 100 years ago.

Steven C. Beda, Assistant Professor of History, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Dismantles Trump’s Attack on Socialism

While Republicans and many Democrats rose and enthusiastically applauded President Donald Trump’s attack on socialism during his State of the Union address Tuesday night, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.)—who, along with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), remained seated—said the president’s remarks showed he’s “scared” of the progressive policies that most Americans are embracing.

Speaking to reporters after Trump proclaimed that “America will never be a socialist country,” Ocasio-Cortez said the president felt the need to lash out at socialism because bold progressives have gotten “under his skin.”

“I think he’s scared,” said Ocasio-Cortez, a self-identified democratic socialist. “He sees that everything is closing in on him. And he knows he’s losing the battle of public opinion when it comes to the actual substantive proposals that we’re advancing.”

While right-wing pundit Peggy Noonan criticized Ocasio-Cortez for remaining stoic during most of Trump’s address, the congresswoman later explained Trump gave her no reason to feel “spirited or warm”:

Why should I be “spirited and warm” for this embarrassment of a #SOTU?

Tonight was an unsettling night for our country. The president failed to offer any plan, any vision at all, for our future.

We’re flying without a pilot. And I‘m not here to comfort anyone about that fact. https://t.co/7bu3QXFMnC

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) February 6, 2019

In an interview with MSNBC‘s Chris Matthews late Tuesday following Trump’s address, Ocasio-Cortez argued Trump’s swipe at socialism demonstrates that he’s “losing on the issues.”

“Every single policy proposal that we have adopted and presented to the American public has been overwhelmingly popular, even some with the majority of Republican voters,” said the New York congresswoman. “When we talk about a 70 percent marginal tax rate on incomes over $10 million, 60 percent of Americans approve it.”

“Seventy percent of Americans believe in improved and expanded Medicare for All. A very large amount of Americans believe that we need to do something about climate change, and that it is an existential threat to ourselves and to our children,” she continued. “What we really need to realize…is that this is an issue of [an] authoritarian regime versus democracy.”

.@HardballChris asked @AOC about Trump tying the “notion of socialism” to the Maduro regime.

“He feels like he feels himself losing on the issues. Every single policy proposal that we’ve adopted and presented to the American public has been overwhelmingly popular.” @AOC pic.twitter.com/b8zdRuJZ6A

— Hardball (@hardball) February 6, 2019

America’s socialists joined Republicans and Democrats in applauding Trump’s anti-socialism “screed”—but for entirely different reasons.

“I love it when the president helps me make the case that it’s socialism or barbarism,” wrote Sarah Jones of New York Magazine.

Branches of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA)—whose membership has soared to record levels since Trump’s election—said they expect a nice membership bump after the president’s address.

“We look forward to seeing the new members who come to our next meeting after the presidential insistence we will never live in a socialist country,” declared DSA’s Eugene, Oregon branch.

Torture Still Scars Iranians 40 Years After Revolution

TEHRAN, Iran — The halls of the former prison in the heart of Iran’s capital now are hushed, befitting the sounds of the museum that it has become. Wax mannequins silently portray the horrific acts of torture that once were carried out within its walls.

But the surviving inmates still remember the screams.

Exhibits in the former Anti-Sabotage Joint Committee Prison that was run under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi include a frightened man trapped in a small metal cage as a cigarette-smoking interrogator shouts above him.

In a circular courtyard, a snarling interrogator is depicted forcing a prisoner’s head under water while another inmate above hangs from his wrists.

As Iran this month marks the 40th anniversary of its Islamic Revolution and the overthrow of the shah, the surviving inmates who suffered torture at the hands of the country’s police and dreaded SAVAK intelligence service still bear both visible and hidden scars. Even today, United Nations investigators and rights group say Iran tortures and arbitrarily detains prisoners.

“We are far from where we must be as far as the justice is concerned,” said Ahmad Sheikhi, a 63-year-old former revolutionary once tortured at the prison. “Justice has yet to be spread in the society, and we are definitely very far from the sacred goals of the martyrs and their imam,” Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

The SAVAK, a Farsi acronym for the Organization of Intelligence and Security of the Nation, was formed in 1957. The agency, created with the help of the CIA and Israel’s Mossad, initially targeted communists and leftists in the wake of the 1953 CIA-backed coup that overthrew elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddegh.

Over time, however, its scope was widened drastically. Torture became widespread, as shown in the museum’s exhibits. Interrogators all wear ties, a nod to their Western connections. Portraits of the shah, Queen Farah and his son, Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, who now lives in exile in the U.S., hang above one torture scene.

“Following the coup, the shah’s regime sank into a legitimacy crisis and it failed to get rid of the crisis until the end of its life,” said Hashem Aghajari, who teaches history at Tehran’s Tarbiat Modares University. “The coup mobilized all progressive political forces against the regime.”

Sheikhi walked with Associated Press journalists through the prison that once held him, built in the 1930s by German engineers. Black-and-white photographs of its 8,500 prisoners from over the years line the walls. They include current Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the late President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani.

Sheikhi, then 19, spent about three months in the prison and 11 months in another after being detained for distributing anti-shah statements from Khomeini, then in exile.

“Four times I was tortured in two consecutive days, every time about 10 minutes,” he recounted. “They used electric cables and wires for flogging my (feet) while I was blindfolded. The first hit was very effective; you felt your heart and brain were exploding.”

Even more frightening was the torture device interrogators and prisoners referred to as the Apollo, named after the U.S. lunar program. Those tortured sat in a chair and had a metal bucket strapped over their head, like a space helmet, that intensified their screams.

“They put my fingers and toes between the jaws of the vises firmly, whipped the soles of my feet with cables and put a metal bucket over head,” Sheikhi said. “My own cries would twirl around inside the bucket and made me delirious and gave me headaches. They would hit the bucket with those cables as well.”

Ezzat Shahi, another former prisoner who planted bombs targeting state buildings, recounted having pins hammered under his nails that would be heated by candles.

“Hanging from the wrists while your hands were handcuffed crossed behind was the most intolerable torture,” Shahi said.

The horror of the torture shocked 20-year-old museumgoer Ameneh Khavari.

“I did not know that the torture might have been this agonizing, such as with the metal cage torture device,” she said. “I had known that there was torture then from movies about the pre-revolution times, but would not have imagined that they looked like this.”

As the revolution took hold, protesters overran the prison. Then Iran’s Islamic government began using it as a prison as well, calling it Tohid. Human Rights Watch has accused Iran of using both Tohid and Evin prisons for detaining political prisoners. Tohid, then run by Iran’s Intelligence Ministry, closed in 2000 under reformist President Mohammad Khatami after lawmakers sought to close prisons not under the control of the judiciary.

Today, Iran’s government faces widespread international criticism from the U.N. and others over its detention of activists and those with ties to the West.

“Iranian authorities use vaguely worded and overly broad national security-related charges to criminalize peaceful or legitimate activities in defense of human rights,” according to a report released in March 2018 by the office of the U.N.’s special rapporteur on human rights in Iran.

Iran has criticized the U.N.’s creation of the special rapporteur’s position and called its findings “psychological and propagandist pressures.”

A series of Westerners, including Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian, were held at Evin Prison. Rezaian is suing Iran in U.S. federal court over his detention, alleging he faced such “physical mistreatment and severe psychological abuse in Evin Prison that he will never be the same.”

Since the revolution, several former prisons from the shah’s time have closed, becoming museums and shopping malls, although new ones were built. A former mayor of Tehran even planned to make Evin Prison a park at one point. Funding never came through, however, and the site remains a prison today.

___

Gambrell reported from Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Associated Press television producer Mohammad Nasiri contributed.

Beyond the 2020 Electoral Circus, a Workers Rebellion Is Brewing

Let’s be brutally honest and unsentimental: There are few, if any, serious prospects for attaining the transformative change we need through the current United States elections and party system.

Yes, Donald Trump’s approval rating has dipped back down into the 30s (thanks to his shutdown madness), the Democrats have control of the House, and a handful of Democratic presidential candidates seem to be embracing progressive ideas like “Medicare for all.”

But, at risk of sounding rude, so what? Even before they took up their new House majority, the dismal, dollar-drenched establishment Democrats killed Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s urgent call for the lower chamber of Congress to commit to the “Green New Deal.” Never mind that fossil fuel-driven global warming is the biggest issue of our or any time, turning the planet into a giant greenhouse-gas chamber. Or that the Green New Deal is a great big, juicy twofer: a major good-job-creation program that would enlist millions of working people in saving livable ecology and thereby help avert the extinction of the human species.

The Democratic Party presidential candidates talking progressive just mean they understand the ruse: You can’t win and cash in on years of “public service” to private interests without pretending to be something you aren’t. The late author Christopher Hitchens usefully described “the essence of American politics” as “the manipulation of populism by elitism.” Hitchens wrote in his study of the corporate-neoliberal Bill Clinton presidency:

That elite is most successful which can claim the heartiest allegiance of the fickle crowd; can present itself as most ‘in touch’ with popular concerns; can anticipate the tides and pulses of public opinion; can, in short, be the least apparently ‘elitist’ … but the smarter elite managers have learned … that solid, measurable pledges have to be distinguished by a reserve tag that earmarks them for the bankrollers and backers.

That foreshadowed the arch-neoliberal Barack Obama presidency. And it’s still the game—the game Hillary Clinton flubbed because she figured that Trump was so obviously “deplorable” that she didn’t have to ruffle any ruling-class feathers by bothering to play it. You can pretend it isn’t, but you’ll be proven wrong when a President Kamala Harris, Beto O’Rourke, Joe Biden, Elizabeth Warren or Cory Booker (or fill in the blank), rides into the White House on a new, record-setting wave of corporate and financial cash and a bevy of ruling-class operatives from Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and the Council on Foreign Relations. The “reserve tag” Hitchens called out is still in place.

This could set the stage for a new, arch-reactionary, faux-populist Republican Congress and presidency. Popular resentment abhors a progressive vacuum orchestrated by arrogant liberal elites (the “adults in the room”) captive to big capital.

“The Democrats,” historian Terry Thomas told me in an email, “want to sit around and act like we’ve got this covered because we’re sane and Dumpster’s [Trump’s] not, our point has been proven, so now just give us power again, and we’ll put everything back together, nothing more needed. … No need for radical change, just put the adults back in. How insulting: the adults were in the room — by their estimation Obama was the epitome of adulthood — and it produced this.”

Bernie Sanders 2020? He will likely (but maybe not!) be pushed to the margins of the field with help from a “liberal” corporate media that will harp on his age and supposedly “extreme” positions. That media and the public relations industry will further sideline him by fixating, as usual, on superficial matters of candidate character and selling the “contenders” like brands of toothpaste and pushing policy to the margins of discussion.

Impeachment? Wait for Mueller Time, but don’t hold your breath. The Democrats actually want to keep Trump around to run against in 2020. They worry that impeachment (which requires a two-thirds vote in the Republican-controlled Senate) without removal could enhance his chances for re-election.

Is there a quick way out of this madness? No. The reigning, corporate-managed and binary party and electoral systems are still hegemonic. The horror of Trump helps make it so for the next election cycle.

But that’s no reason to give up on progressive change. It’s understandable that millions of Americans are going to get pulled along into an “anybody but Trump” fever. He’s a malignant narcissist and creeping ecocidal fascist. Nobody to the left and human side of the white-nationalist-harboring Republican Party could possibly want him to get a second term.

At the same time, it will be tactically useful for the left if Democrats own the stink of the very system that owns them come 2021. The “inauthentic opposition” (as the late political scientist Sheldon Wolin aptly labeled the Democrats) gets to masquerade as a people’s party—and to sell major (i.e., capitalist) party politics—most effectively when it is out of office. It is most clearly exposed as inadequate, and as a party beholden to capital, when it holds nominal power.

Meanwhile, over time, signs and models of real popular resistance have emerged from beyond the quadrennial electoral extravaganza that is sold to us as “politics”—the only politics that matters. Examples include: the inspiring fights many rural, red state communities undertook against federal immigration raids in 2017 and 2018; the successful strikes teachers unions (most recently in Los Angeles) have fought on behalf of public education; public sector unions’ successful fight against a right-wing Supreme Court decision meant to wipe out their membership base; and airport and airline workers’ recent halting of Trump’s ridiculous government shutdown through the exercise of their strategic workplace capacity to idle capital and disrupt profits. Sara Nelson, the fiery head of the flight attendants union, called during the shutdown for a “national general strike.” American yellow vests, anyone?

Organic rank-and-file labor activity is on the rise. I recently attended a workers town hall organized by the Democratic Socialists of America in Chicago. A community college instructor, three nurses, a music teacher, a teamster, a charter-school teacher and a federal government worker told harrowing and inspiring stories of their struggles to form unions and win contracts from arrogant employers who treat their workers “like commodities” at the expense of both their employees and the public they claim to serve. The federal worker spoke movingly of how the air-traffic controllers forced Trump’s hand and helped “awaken the sleeping giant of worker power.”

Could this growing working class insurgency beneath the headlines take a meaningfully independent electoral form beyond the reach of capital? Yes, with time—and with smart, patient local organizing.

A new movement for a real people’s party is forming in the U.S. Led by a group of young former Sanders staffers, who learned from experience that the Democrats offer a hopelessly flawed vehicle, the Movement for a People’s Party (MPP) stakes its hopes not on national candidates and celebrities but rather on grassroots organizing that connects the labor movement to local communities around issues that matter to everyday working people.

The heart and soul of the MPP is its Labor Community Campaign for an Independent Politics (LCCIP), an effort to put real organizing meat on the bones of two resolutions passed at the 2017 AFL-CIO Convention. “Whether the candidates are elected from the Republican or Democratic Party,” the first resolution stated, “the interests of Wall Street have been protected and advanced, while the interests of labor and working people have generally been set back.” The second resolution concluded that “the time has passed when we can passively settle for the lesser of two evils politics.”

Moving seriously on that language to make it more than just noise means connecting with working people on the jobs and in the communities where they live. As LCCIP endorser Chris Silvera, the secretary-treasurer of Teamsters Local 808 in Long Island City, N.Y., told me last week, “We need to start small, where people work and live. We need to build up from where we can actually win: city council, then maybe mayoral, then gubernatorial.” Silva added that “a desperate working-class” doesn’t have the resources to decide presidential campaigns in which “even the loser spends half a billion dollars” (or congressional campaigns that run through millions). Working people don’t have the time and energy to follow the bouncing ball of “Russiagate” or the latest presidential town hall in Des Moines. They do have time and energy for backing local and state candidates who advocate for working people and communities on issues directly relevant to their lives.

Another LCCIP advocate is Nancy Wohlforth, a former member of the AFL-CIO executive board who describes herself as one of labor’s “notorious third-party activists.” While she expressed to me cautious respect for likely Democratic presidential candidate Sherrod Brown (a longstanding union ally) as well as Sanders, Wohlforth said she thinks the presidential spectacle is out of play for progressives because “everyone” is understandably “on the bandwagon to get rid of Trump.” But on a local level, she said, “We can have some movement.”

Wohlforth cited the example of Richmond, Calif., where union activists affiliated with the Richmond Progressive Alliance, an independent political organization that united left-leaning activists across party lines, beat back the city’s corporate giant—Chevron—to win a solid City Council majority and the mayoralty. The progressive city government forced huge tax payments from Chevron, limited pollution, raised the minimum wage to $15 an hour, passed rent control, implemented numerous green measures and established Richmond as an immigrant-friendly sanctuary city.

LCCIP sponsor Donna Dewitt is former chair of the South Carolina AFL-CIO and current chair of the South Carolina Labor Party. While she retains hope for a second Sanders run, she said she has little interest in the presidential candidate circus atop the Democratic Party. Instead, she dedicates her energies to fighting on local and state issues and finding working-class progressives to run for electable offices.

How long before a real labor- and community-based 21st century people’s party could run viable candidates and win races for national office, including the presidency? Silvera told me that’s roughly 10 years out. MPP founder Nick Brana offered a shorter time frame. He told me late last year that the likely upcoming rigging of the 2020 Democratic primaries against Sanders and the overdue onset of the next Wall Street-crafted Great Recession could open big space for such candidates in 2024.

But who knows? It’s not about the crystal ball. Rather, it’s about many-sided organizing and building out from the bottom up to create a powerful grassroots movement that connects local community and workplace activism to the broader political economy to address interrelated national and global crises of democracy, inequality, human and civil rights, peace and (last but not least) livable ecology.

It’s also about building on the great leftist intellectual Noam Chomsky’s warning about what a Sanders presidency would have faced in 2017:

“His campaign … [was] a break with over a century of American political history. No corporate support, no financial wealth, he was unknown, no media support. The media simply either ignored or denigrated him. And he came pretty close—he probably could have won the nomination, maybe the election. But suppose he’d been elected. He couldn’t have done a thing. Nobody in Congress, no governors, no legislatures, none of the big economic powers, which have an enormous effect on policy. All opposed to him. In order for him to do anything, he would have to have a substantial, functioning party apparatus, which would have to grow from the grass roots. It would have to be locally organized, it would have to operate at local levels, state levels, Congress, the bureaucracy—you have to build the whole system from the bottom.” [emphasis added]

This is a key and commonly underestimated point. A grassroots people’s movement and politics can’t just be just about electing progressive-populist candidates. It must also be about defending leftist politicians against capitalist and broader right-wing reaction after they gain office.

Sanders Highlights American Struggles in Fierce SOTU Response

Beginning his speech by congratulating Stacey Abrams for delivering a strong response to President Trump’s State of the Union address on behalf of the Democratic Party, Bernie Sanders quickly delved into all the things Trump got wrong about the economy, infrastructure, health care, immigration and more in his own response delivered online.

The nearly 30-minute speech was watched by tens of thousands on YouTube alone, where commenters filled the page with comments such as “Bernie 2020” and “Feel the Bern” and expressed their support for progressive policies supported by the Vermont senator such as “Medicare-for-all” and the “Green New Deal.”

Here are some of the highlights of his speech, followed by the full video below:

“Trump said tonight, ‘We are born free, and we will stay free.’ Well, I say to President Trump: People are not truly free when they can’t afford to go to the doctor when they are sick. They are not truly free when they cannot afford to buy the prescription drugs they so desperately need. People are not truly free when they are exhausted because they are working longer and longer hours for lower wages.

“People are not truly free when they cannot afford a decent place in which to live. People certainly are not free when they cannot afford to feed their families.”

“For many of President Trump’s billionaire friends, the truth is, they have never, ever had it so good. But for the middle class and the working families of our country, the truth is that the economy is not so great.”

“[Trump’s] demonization of latinos is nothing less than racist, it is wrong and it also happens to be factually inaccurate. Undocumented latino immigrants commit fewer crimes in the United States than the general public.”

“How could the president Trump not mention the words Social Security, Medicare or Medicaid, in a State of the Union speech when he promised over and over again during his campaign … that he would not cut these programs? Could it be because his budget proposed massive cuts to Medicare and Medicaid and Social Security in direct violation of his campaign pledge?”

“When you’re president, you bring our people together. But in an unprecedented way, that is not what this president is doing. In fact, he is trying to divide us up; he is trying to have one group turn against another group. And that is certainly not what this country is supposed to be about.”

Sanders provided viewers with the results of a spate of polls that highlight massive American support for affordable prescription drugs and health care, infrastructure spending that would create jobs, background checks on gun purchases, the legalization of marijuana, a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children, more regulation of Wall Street, a significant increase in the minimum wage and government-paid college tuition. The Vermont senator goes on to say that the reason that Congress isn’t doing what the “overwhelming majority of Americans” want has “everything to do with the power of the monied interests.”

“Let us bring our people together,” concludes Sanders, “to take on and defeat a ruling class whose greed is destroying our nation. The billionaire class must learn that they cannot have it all. Our government belongs to each and every one of us, not just the few.

“Let us create the kind of America we know we can become.”

February 5, 2019

Stacey Abrams Praises Immigrants, Slams Trump’s Shutdown ‘Stunt’ in SOTU Response

Shortly after President Donald Trump concluded his lengthy and wide-ranging State of the Union address on Tuesday evening, in which he touched on no fewer than two dozen key issues, Stacey Abrams was ready with her comeback. Abrams was also ready for her comeback, as her televised follow-up to the president’s speech marked the most prominent appearance the Georgia Democrat had made on the national stage since her bid to unseat Governor Brian Kemp in her home state became one of the most vigorously contested races of the 2018 election cycle.

Given her role, not to mention visibility, in Tuesday’s proceedings, it was clear that Abrams’ standing hadn’t suffered since her still-challenged defeat. To the contrary, that night Abrams became the first black woman, as well as the first person who was not concurrently an elected office-holder, to deliver a State of the Union response speech. (The former state representative is now putting her training as a lawyer, along with her hard-won experience from last fall, to work in running a voting rights organization called Fair Fight Georgia.)

Abrams may still have her supporters’ votes, but how did she fare in her rhetorical face-off with President Trump? Taking on each of his biggest claims was neither practical nor possible in the brief time she was allotted, so she had to make sure each point counted and each hit landed with maximum impact.

After making a nod to her parents’ work ethic and values, as well as a mention of her path to politics, Abrams cut to a recent scene in which she helped pass out food to furloughed federal employees. That’s when she got down to business, calling the protracted government shutdown a “disgrace” and “a stunt engineered by the president of the United States.”

Next came, in short order, mass incarceration, education, gun control and of course, immigration. Watch the video below and read the transcript that follows to get the full story.

Good evening, my fellow Americans. I’m Stacey Abrams, and I am honored to join the conversation about the state of our union. Growing up, my family went back and forth between lower middle class and working poor.

Yet, even when they came home weary and bone-tired, my parents found a way to show us all who we could be. My librarian mother taught us to love learning. My father, a shipyard worker, put in overtime and extra shifts; and they made sure we volunteered to help others. Later, they both became United Methodist ministers, an expression of the faith that guides us.

These were our family values — faith, service, education and responsibility.

Now, we only had one car, so sometimes my dad had to hitchhike and walk long stretches during the 30 mile trip home from the shipyards. One rainy night, Mom got worried. We piled in the car and went out looking for him – and eventually found Dad making his way along the road, soaked and shivering in his shirtsleeves. When he got in the car, Mom asked if he’d left his coat at work. He explained he’d given it to a homeless man he’d met on the highway. When we asked why he’d given away his only jacket, Dad turned to us and said, “I knew when I left that man, he’d still be alone. But I could give him my coat, because I knew you were coming for me.”

Our power and strength as Americans lives in our hard work and our belief in more. My family understood firsthand that while success is not guaranteed, we live in a nation where opportunity is possible. But we do not succeed alone — in these United States, when times are tough, we can persevere because our friends and neighbors will come for us. Our first responders will come for us.

It is this mantra — this uncommon grace of community — that has driven me to become an attorney, a small business owner, a writer, and most recently, the Democratic nominee for Governor of Georgia. My reason for running for governor was simple: I love our country and its promise of opportunity for all, and I stand here tonight because I hold fast to my father’s credo – together, we are coming for America, for a better America.

Just a few weeks ago, I joined volunteers to distribute meals to furloughed federal workers. They waited in line for a box of food and a sliver of hope since they hadn’t received a paycheck in weeks. Making their livelihoods a pawn for political games is a disgrace. The shutdown was a stunt engineered by the President of the United States, one that defied every tenet of fairness and abandoned not just our people – but our values.

For seven years, I led the Democratic Party in the Georgia House of Representatives. I didn’t always agree with the Republican Speaker or Governor, but I understood that our constituents didn’t care about our political parties — they cared about their lives. So, when we had to negotiate criminal justice reform or transportation or foster care improvements, the leaders of our state didn’t shut down — we came together. And we kept our word.

It should be no different in our nation’s capital. We may come from different sides of the political aisle; but, our joint commitment to the ideals of this nation cannot be negotiable.

Our most urgent work is to realize Americans’ dreams of today and tomorrow. To carve a path to independence and prosperity that can last a lifetime.Children deserve an excellent education from cradle to career. We owe them safe schools and the highest standards, regardless of zip code.

Yet this White House responds timidly while first graders practice active shooter drills and the price of higher education grows ever steeper. From now on, our leaders must be willing to tackle gun safety measures and the crippling effect of educational loans; to support educators and invest what is necessary to unleash the power of America’s greatest minds.

In Georgia and around the country, people are striving for a middle class where a salary truly equals economic security. But instead, families’ hopes are being crushed by Republican leadership that ignores real life or just doesn’t understand it. Under the current administration, far too many hard-working Americans are falling behind, living paycheck to paycheck, most without labor unions to protect them from even worse harm.

The Republican tax bill rigged the system against working people. Rather than bringing back jobs, plants are closing, layoffs are looming and wages struggle to keep pace with the actual cost of living.

We owe more to the millions of everyday folks who keep our economy running: like truck drivers forced to buy their own rigs, farmers caught in a trade war, small business owners in search of capital, and domestic workers serving without labor protections. Women and men who could thrive if only they had the support and freedom to do so.

We know bipartisanship could craft a 21st century immigration plan, but this administration chooses to cage children and tear families apart. Compassionate treatment at the border is not the same as open borders. President Reagan understood this. President Obama understood this. Americans understand this. And Democrats stand ready to effectively secure our ports and borders. But we must all embrace that from agriculture to healthcare to entrepreneurship, America is made stronger by the presence of immigrants — not walls.

Rather than suing to dismantle the Affordable Care Act, as Republican Attorneys General have, our leaders must protect the progress we’ve made and commit to expanding health care and lowering costs for everyone.

My father has battled prostate cancer for years. To help cover the costs, I found myself sinking deeper into debt — because while you can defer some payments, you can’t defer cancer treatment. In this great nation, Americans are skipping blood pressure pills, forced to choose between buying medicine or paying rent. Maternal mortality rates show that mothers, especially black mothers, risk death to give birth. And in 14 states, including my home state where a majority want it, our leaders refuse to expand Medicaid, which could save rural hospitals, economies, and lives.

We can do so much more: take action on climate change. Defend individual liberties with fair-minded judges. But none of these ambitions are possible without the bedrock guarantee of our right to vote. Let’s be clear: voter suppression is real. From making it harder to register and stay on the rolls to moving and closing polling places to rejecting lawful ballots, we can no longer ignore these threats to democracy.

While I acknowledged the results of the 2018 election here in Georgia — I did not and we cannot accept efforts to undermine our right to vote. That’s why I started a nonpartisan organization called Fair Fight to advocate for voting rights.

This is the next battle for our democracy, one where all eligible citizens can have their say about the vision we want for our country. We must reject the cynicism that says allowing every eligible vote to be cast and counted is a “power grab.” Americans understand that these are the values our brave men and women in uniform and our veterans risk their lives to defend. The foundation of our moral leadership around the globe is free and fair elections, where voters pick their leaders — not where politicians pick their voters.

In this time of division and crisis, we must come together and stand for, and with, one another. America has stumbled time and again on its quest towards justice and equality; but with each generation, we have revisited our fundamental truths, and where we falter, we make amends.

We fought Jim Crow with the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, yet we continue to confront racism from our past and in our present — which is why we must hold everyone from the very highest offices to our own families accountable for racist words and deeds — and call racism what it is. Wrong.

America achieved a measure of reproductive justice in Roe v. Wade, but we must never forget it is immoral to allow politicians to harm women and families to advance a political agenda. We affirmed marriage equality, and yet, the LGBTQ community remains under attack.

So even as I am very disappointed by the president’s approach to our problems — I still don’t want him to fail. But we need him to tell the truth, and to respect his duties and the extraordinary diversity that defines America.

Our progress has always found refuge in the basic instinct of the American experiment — to do right by our people. And with a renewed commitment to social and economic justice, we will create a stronger America, together. Because America wins by fighting for our shared values against all enemies: foreign and domestic. That is who we are — and when we do so, never wavering — the state of our union will always be strong.

Thank you, and may God bless the United States of America.

Trump Calls for End of Resistance Politics in State of the Union

WASHINGTON — Facing a divided Congress for the first time, President Donald Trump on Tuesday called on Washington to reject “the politics of revenge, resistance and retribution.” He warned emboldened Democrats that “ridiculous partisan investigations” into his administration and businesses could hamper a surging American economy.

Trump’s appeals for bipartisanship in his State of the Union address clashed with the rancorous atmosphere he has helped cultivate in the nation’s capital — as well as the desire of most Democrats to block his agenda during his next two years in office. Their opposition was on vivid display as Democratic congresswomen in the audience formed a sea of white in a nod to early 20th-century suffragettes.

Trump spoke at a critical moment in his presidency, staring down a two-year stretch that will determine whether he is re-elected or leaves office in defeat. His speech sought to shore up Republican support that had eroded slightly during the recent government shutdown and previewed a fresh defense against Democrats as they ready a round of investigations into every aspect of his administration.

“If there is going to be peace and legislation, there cannot be war and investigation,” he declared. Lawmakers in the cavernous House chamber sat largely silent.

Looming over the president’s address was a fast-approaching Feb. 15 deadline to fund the government and avoid another shutdown. Democrats have refused to acquiesce to his demands for a border wall, and Republicans are increasingly unwilling to shut down the government to help him fulfill his signature campaign pledge. Nor does the GOP support the president’s plan to declare a national emergency if Congress won’t fund the wall.

Wary of publicly highlighting those intraparty divisions, Trump made no mention of an emergency declaration in his remarks, though he did offer a lengthy defense of his call for a border wall. But he delivered no ultimatums about what it would take for him to sign legislation to keep the government open.

“I am asking you to defend our very dangerous southern border out of love and devotion to our fellow citizens and to our country,” he said.

Trump devoted much of his speech to foreign policy, another area where Republicans have increasingly distanced themselves from the White House. He announced details of a second meeting with North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, outlining a summit on Feb. 27 and 28 in Vietnam. The two met last summer in Singapore, though that meeting only led to a vaguely worded commitment by the North to denuclearize.

As he stood before lawmakers, the president was surrounded by symbols of his emboldened political opposition. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who was praised by Democrats for her hard-line negotiating during the shutdown, sat behind Trump as he spoke. And several senators running for president were also in the audience, including Sens. Kamala Harris of California and Cory Booker of New Jersey.

Another Democratic star, Stacey Abrams, will deliver the party’s response to Trump. Abrams narrowly lost her bid in November to become America’s first black female governor, and party leaders are aggressively recruiting her to run for U.S. Senate from Georgia.

In excerpts released ahead of Abrams’ remarks, she calls the shutdown a political stunt that “defied every tenet of fairness and abandoned not just our people, but our values.”

Trump’s address amounted to an opening argument for his re-election campaign. Polls show he has work to do, with his approval rating falling to just 34 percent after the shutdown, according to a recent survey conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

One bright spot for the president has been the economy, which has added jobs for 100 straight months. He said the U.S. has “the hottest economy anywhere in the world.”

He said, “The only thing that can stop it are foolish wars, politics or ridiculous partisan investigations” an apparent swipe at the special counsel investigation into ties between Russia and Trump’s 2016 campaign, as well as the upcoming congressional investigations.

The diverse Democratic caucus, which includes a bevy of women, sat silently for much of Trump’s speech. But they leapt to their feet when he noted there are “more women in the workforce than ever before.”

The increase is due to population growth — and not something Trump can credit to any of his policies.

Turning to foreign policy, another area where Republicans have increasingly been willing to distance themselves from the president, Trump defended his decisions to withdraw U.S. troops from Syria and Afghanistan.

“Great nations do not fight endless wars,” he said, adding that the U.S. is working with allies to “destroy the remnants” of the Islamic State group and that he has “accelerated” efforts to reach a settlement in Afghanistan.

IS militants have lost territory since Trump’s surprise announcement in December that he was pulling U.S. forces out, but military officials warn the fighters could regroup within six months to a year of the Americans leaving. Several leading GOP lawmakers have sharply criticized his plans to withdraw from Syria, as well as from Afghanistan.

Trump’s guests for the speech include Anna Marie Johnson, a woman whose life sentence for drug offenses was commuted by the president, and Joshua Trump, a sixth-grade student from Wilmington, Delaware, who has been bullied over his last name. They sat with first lady Melania Trump during the address.

Trump Organization “Purges” Undocumented Workers, Report Reveals

President Trump has accused undocumented immigrants of spreading crime and taking jobs from Americans. He even invented a rape epidemic and blamed it on them. But while Trump was railing against undocumented immigrants, his companies were employing them. Now, at least 18 have been fired from golf courses in New York and New Jersey, The Washington Post reported Tuesday.

It’s part of what reporters Joshua Partlow and David Fahrenthold call a “purge,” begun, they say, “after a series of reports about the clubs’ employment of workers without legal status.” The New York Times first reported on undocumented workers at Trump National Golf Club in Bedminster, N.J., in December, which set off an internal audit of employees’ immigration status, the Post says.

The employees “worked in food service, maintenance, housekeeping and other jobs at the golf courses. Many said they had held these jobs for years and that the Trump Organization previously had paid little attention to their immigration status,” Partlow and Fahrenthold write.

Eric Trump, the president’s son, who, with his brother, Donald Trump Jr., runs the day-to-day operations of the Trump Organization, said in a statement last month, “We are making a broad effort to identify any employee who has given false and fraudulent documents to unlawfully gain employment,” adding, “[w]here identified, any individual will be terminated immediately.”

Many of the undocumented workers who have been fired were longtime, even prized, employees. Victorina Morales, a housekeeper at the Bedminster club, received a certificate from the White House Communications Agency for her “outstanding” service. She wasn’t immediately fired for speaking out about her and her colleagues’ status, but she told the Times she didn’t feel comfortable returning to work. Juan Quintero, who was fired, told the Post that he had worked at the Trump National Golf Club in New York’s Hudson Valley for approximately 18 years.

“Half of my life,” he told the Post, “and now nothing.”

There are approximately 11 million undocumented immigrants in the United States, according to research from The Pew Charitable Trusts. Approximately 8 million of them have jobs. As Miriam Jordan writes in The New York Times, “They are vital to industries such as agriculture, ]hospitality and construction.” Because of their economic impact, “Companies in several sectors have been calling for years for Congress to pass immigration reform legislation that would offer some form of legalization to longtime undocumented residents,” Jordan adds.

Four of the fired former Trump Organization employees visited Congress last week to meet with multiple lawmakers, the Post said, including Sen. Robert Menendez, D-N.J., who wrote to FBI Director Christopher Wray and Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, asking them to open an investigation into Trump’s golf clubs. Menendez said workers “describe a hostile environment where they were verbally abused and threatened.” He asked that they also be protected from deportation during any investigation.

Meanwhile, Morales, the former housekeeper, will attend Tuesday’s State of the Union address, as a guest of Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman, D-N.J.

Read the full Washington Post story here.

Death Row Inmate Domineque Ray Never Stood a Chance

On the morning of July 29, 1999, 12 men and women filed into the jury box in the Dallas County Courthouse in Selma, Alabama. The day before, they had convicted Domineque Ray of raping and killing a 15-year-old girl in a cotton field outside of town. It had taken just an hour and 40 minutes to deliver their verdict.

It was a terrible crime, and not the first killing Ray, 22, had been convicted of. Five and a half months earlier, Ray had been found guilty for his role in the murders of two teenage boys in Selma.

Now, shortly after 9 a.m., the jury was set to hear testimony on whether Ray’s life should be spared or if he should be sentenced to die.

Juries in death penalty cases have been required to separately weigh questions of guilt and punishment for more than four decades. Those facing the possibility of death get to argue for mercy; they’re allowed to present evidence that might temper a jury’s willingness to recommend execution a defendant’s limited intelligence, for instance, or history of victimization. The obligation of defense lawyers in such cases, the U.S. Supreme Court has held, is considerable.

William Whatley Jr. was Ray’s lead defense lawyer in the Dallas County courtroom. Whatley was a former prosecutor, and this was not his first death penalty case as a defense lawyer. But he opted to let his co-counsel, Juliana Taylor, make the presentation to the jury. Taylor, just three years out of law school, had little experience. She’d never been the lead lawyer in a criminal trial. And she’d worked on just one capital case.

Whatley and Taylor put a single witness on the stand, Ray’s mother. She testified that she loved her son, and that his life had not been easy. His father, she said, had disowned him, and she had tried her best. The testimony lasted roughly 10 minutes.

The jury, after two hours of deliberation, voted that Ray be sentenced to death. He is set to die by lethal injection on Thursday.

In the two decades since the jury’s decision, lawyers for Ray have mounted appeals in both state and federal court, insisting he deserves a new trial. They have alleged that Whatley failed to adequately represent Ray. They have alleged that prosecutors withheld evidence of other suspects in the murder of the young girl. They have argued that members of the jury knew a police detective involved in the case and should have been kept off the panel.

Most recently, in an appeal still making its way through the Alabama courts, the lawyers have argued that the state withheld critical evidence involving Ray’s chief accuser, his alleged accomplice in the murders. The lawyers have asserted that Marcus Owden, who confessed to the three killings, had been suffering from schizophrenia when he testified, and that prosecutors withheld that fact from Ray’s defense team.

Prosecutors have denied the claims of misconduct, and they have prevailed in each of Ray’s appeals.

But the question of whether Ray was adequately represented during the penalty phase of his trial has shadowed the case almost from the time the jury returned its verdict for death. In appeals filed in state and federal court beginning in 2003, Ray’s lawyers have attacked Whatley’s performance, saying it failed to meet the constitutional standard required of defense lawyers in such proceedings.

Whatley failed to hire an investigator to explore Ray’s background. He withdrew a request to have Ray evaluated by a forensic neuropsychologist. There were family members who said they would have been willing to testify, but they were not found, much less put on the stand. School records weren’t researched, nor were records chronicling Ray’s experience in foster care.

“Ray was sentenced to death by a jury and judge who simply had no idea of who Ray actually is and how he came to be a defendant in a capital case,” read his 2011 federal petition for habeas corpus. “Whatley and Taylor prepared virtually no mitigation case at all, making it all but certain that jurors would recommend the death penalty.”

In their filings, Ray’s lawyers have laid out the details of what they say was a horrifying upbringing for a boy with an 80 IQ. Ray, 17 at the time of the first murders, had been beaten as he went from household to household from the age of 3 on — bouncing between Selma, Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, Virginia and South Carolina. After being left in an abandoned building in Chicago, he’d been taken in by state child welfare officials. He was then sent off to suffer more, sexually abused by his stepmother’s family as a toddler and encouraged by his mother to have sex with her friends when he was a teenager. He never made it past eighth grade. He’s since been diagnosed with schizotypal personality disorder, characterized by severe social anxiety, paranoia and unusual beliefs.

Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said there is no reliable national data on how often those convicted in a death penalty case get spared as a result of information made available to juries at the penalty phase.

“In most of the country, nobody keeps track,” Dunham said. “It’s one of our biggest gripes.”

There are, though, any number of cases — in Alabama and other states — where juries have opted against execution for even those convicted of the most brutal crimes. Barry Lee Jones, then 20, was convicted of sodomizing and murdering his 7-month-old, but an Alabama jury voted to spare him after defense lawyers and an investigator worked with his mother, sister, aunt, uncle and family spiritual adviser to put together his life story. Looking at school records, they found some evidence of mental disability. Whatley was the lead lawyer.

In Ohio, then-Gov. John Kasich commuted the death sentence of Raymond Tibbetts in 2018 after a juror wrote to him saying he had learned of the defendant’s abusive childhood only after he had voted for execution. The juror told Kasich he was upset that he didn’t have all of the information when he made his decision.

In federal death penalty cases over the last 30 years, juries have opted against execution in roughly two-thirds of them. Those spared include Zacarias Moussaoui, the man often called the 20th hijacker in the 9/11 terrorist attacks. A psychologist and friends testified about Moussaoui’s abusive childhood, his years in an orphanage and a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia.

With Ray’s scheduled execution days away, ProPublica interviewed a number of people connected to that disputed moment in the Dallas County Courthouse. Whatley, the trial lawyer; Europe Ray, the brother who said he would have been happy to testify in 1999; the appellate lawyer who to this day is trying to save Ray’s life; and jurors from the trial, including some who had voted for death and one who had not.

Whatley, for his part, stands by his work on Ray’s behalf. He had no access to much of the material later uncovered about Ray’s childhood. But he has his regrets, too. He said he should have hired an investigator specifically to explore Ray’s life, education and mental health. He’s done it in many of the death penalty cases he’s handled since, and in the 28 capital murder trials he’s completed, just one of his clients has been sentenced to death: Ray.

“I’ve done this a long time, I’ve been practicing law now for 34 years, and I know that I could have done better representing Domineque if I would have had somebody to guide our investigation of mitigation evidence,” Whatley said.

The Trial Lawyer: “I Mean, I Would Have Loved to Have Had It”

The murders happened 18 months apart, and they went unsolved for years.

First, two brothers, Ernest and Reinhard Mabins, 18 and 13, were shot dead in their Selma home in February 1994. They were found by their parents, but there were few leads and no arrests.

Then, in August 1995, the decomposing remains of Tiffany Harville, 15, were found by a farmer driving his tractor in a field outside of town. She’d been raped and knifed to death. Months later, a local man was jailed and charged.

But on Aug. 18, 1997, with the Mabins killings unsolved and the man arrested for the Harville murder awaiting trial, Owden walked into the Selma Police Department headquarters. Accompanied by his pastor, Owden, 21, said he and his longtime friend, Ray, were responsible for all three killings. They had wanted to start their own gang, and had killed the Mabins boys and Harville to establish their bona fides. Owden had found religion, and confessing was the right thing to do, he said.

Ray was quickly interviewed by detectives. After several hours, he made a videotaped confession, saying he had played a role in the three murders.

Whatley only came to represent Ray in the three murders after Ray’s first lawyers withdrew from the case, citing a dispute over whether Ray should seek a plea bargain.

In an interview, Whatley said the chances of Ray being acquitted seemed daunting. While Ray later recanted his confession, it would be admissible as evidence. Owden had agreed to plead guilty to all three killings to avoid the death penalty, and he was set to testify against Ray. Whatley said that almost from the start he saw avoiding the death penalty as his top priority.

“I try to educate my clients, and my client families, that this is what we do. It’s not like a regular criminal case,” Whatley said of his strategy in death penalty cases. “They hang up on the guilty, not guilty. Yes, it’s important. Every case is important, but the focus on the punishment phase is so much more important when the state is actively seeking the death penalty.”

Whatley was born in Dothan, a midsize city in the southeastern corner of Alabama, and later attended the University of Alabama Law School. While friends of his were studying wills and trusts and property law, he signed up to assist lawyers in court as a third-year student. He had no interest in paper pushing, he said, and quickly became enamored of the rush of standing up in front of a jury.

After graduating from law school in 1984, Whatley worked for Alabama Attorney General Charles Graddick. In the attorney general’s office in Montgomery, Whatley worked in the Capital Punishment Unit. He prosecuted one death penalty case himself, but he also spent time helping the office answer appeals in death penalty cases, where those convicted had alleged inadequate defense counsel. He’d review the work of the defense lawyers and question them during hearings.

Ray’s trial for the Mabins killings — in February 1999, five years after the slayings — lasted under three days. Owden testified. There was testimony about a fingerprint found at the home that allegedly matched Ray’s. Ray, against Whatley’s advice, opted to testify himself, and he denied killing the boys, friends of his family he had known for years.

The jury quickly convicted Ray, and the penalty phase came next. Whatley handled the presentation. Ray’s mother was the lone witness. She testified roughly as she would later: Ray’s childhood was rough and full of struggle. The jury deliberated for 50 minutes before returning a vote to spare Ray. The vote was seven for life without parole, five for death.

In Alabama, prosecutors need to persuade at least 10 of 12 jurors that a death sentence is appropriate. At least seven votes are needed to recommend life without parole. But at the time, judges had the power to overrule a jury’s recommendation, whether it was to spare the defendant or see him or her executed. The judge let the jury’s recommendation stand. The mother of the Mabins boys had told the judge at the sentencing hearing that she did not want to see Ray killed.

The Harville trial still loomed. Prior to the breakdown over plea bargain options, Ray’s first two lawyers had made two important requests of the judge in the Harville case: to be allowed to hire an investigator to work on the case, and to have Ray evaluated by an independent forensic neuropsychologist.

Whatley, with months to prepare, managed to persuade Ray not to testify. But Owden was set to take the stand again, and Ray, while he denied raping Harville, had confessed to stabbing her at least once with a knife. But Whatley did have some material to work with. No physical evidence had been produced placing Ray at the scene of the murder. A local man had spent 18 months in jail charged with the murder, accused of killing her because she refused to have sex with him.

Yet Whatley chose to withdraw the requests that had been made by the prior lawyers. Whatley told the judge there was no need for a psychiatric exam. He had met with Ray and saw no signs of a significant mental health issue. A state psychologist had met with Ray briefly and concluded the same thing. Whatley also said there was no need for any more money for an investigator. A former state trooper had done some initial work with the first defense lawyers, but Whatley said he’d been told there was nothing else to be investigated.

The trial in late July 1999 was as short as the first, and it ended with another conviction.

Whatley, in an interview, said he was comfortable allowing Taylor, his young co-counsel, to handle the penalty phase. She had been responsible for talking to people about Ray’s background, Whatley said, and was regarded as a promising young lawyer. Taylor today said she was qualified to make the presentation but was hampered by Ray’s refusal to help.

Whatley said Ray would not discuss his childhood, other than to say it was unremarkable, and he provided no contacts for others in his family who might testify. Ray’s mother had given the lawyers a short list of people from his neighborhood whom they could talk to. Whatley admitted he never looked into Ray’s experiences in school. He said he didn’t ask for a mental health expert to testify during the penalty phase because he didn’t see the need to. He said if he’d asked at the start of the trial for an expert to help pick the jury, the judge would have laughed him out of the courtroom.

Ray’s mother, Gladys, was the sole source of information about her son, Whatley said.

“We didn’t know of anybody else. We didn’t know of any other person there, and we had no other person,” Whatley said.

Today, Whatley has no trouble understanding how helpful it would have been to have known more.

“I mean, I would have loved to have had it,” he said.

But Whatley said the single greatest factor that led to the jury recommending death was that the judge allowed prosecutors to tell the jury of Ray’s prior conviction in the Mabins case. He said he objected to the admission of the prior conviction but lost.

“I knew as soon as they heard it that they were going to vote for death,” he said of the jury. “I knew they were going to do it. You could see it in their faces.”

Ray’s lawyers today fault Whatley for not having moved earlier and more aggressively to bar the prior conviction from being introduced. He could have filed a formal motion, they said, but he did not.

Whatley’s assessment of his work is mixed. Defense lawyers were paid poorly, even in capital cases. And lawyers were required to ask the judge for any and all resources. Whatley was paid just over $9,000 for his months of work.

Whatley does not cite his modest compensation as an excuse for his work, but he concedes without hesitation that, given the enhanced requirements for lawyers in such cases today, the job he was able to do in 1999 falls short of the constitutional standard. As a result, he emphatically believes Ray deserves a new hearing on his sentence.

“I just, I hate it,” he said. “I just don’t think it was fair the way it turned out.”

The Brother: “I Can Recall It Like Day One”

The Chicago police found Europe and Domineque Ray running in an alley in the fall of 1980. The boys, 5 and 4, told the officers they lived in a nearby abandoned building. Their mother, they said, had gone missing days before.

Inside the building, newspapers covered the floor. A mattress was the lone bit of furniture. The single appliance was a refrigerator. When the police opened it, it held a single can of Coca-Cola.

Europe would later describe a nightmarish existence in the building. Maggots. Rodents. Abusive boyfriends who beat Gladys. Europe remembers one of the boyfriends holding him above his head and threatening to throw him down a flight of stairs. Domineque looked on, frozen in place.

“You wouldn’t believe that a human could live there,” Verna Mullins, a great-aunt who lived in Chicago, said of the building.

For Europe and Domineque, the abandoned building in Chicago was but one stop on a journey of pain and dislocation. The boys had both been born in Selma to Gladys Ray. She had married at 17 and was soon overwhelmed after she separated from the boys’ father. She would struggle with drugs, poverty, abusive men and her own mental health problems, including at least one suicide attempt. The boys wound up in foster care with their great-aunt, then back with their father and then back once more with their mother in Selma. Europe told the authorities at different points that they were beaten or abused by everyone: mother, father, stepmother, boyfriends, siblings. Domineque was dressed up in girls’ clothes for sport. He was sexually abused, according to court filings made as part of his appeal.

“I can recall it like Day One,” Europe, in a recent interview, said of his shared childhood experiences.

Earl Cobb, the boys’ father, denied any abuse, saying they had always been “one big, happy family.”

Europe said he was shocked by the telephone call he got sometime in the early 2000s. Europe had escaped Selma and built a new life for himself in Indianapolis. He’d married and had a child. He had a job as the activity director at a senior center in the city. He d put distance between himself and his family, including Domineque.

The call was from students at New York University Law School. Bryan Stevenson, the author of the book “Just Mercy,” was a professor there. Stevenson, widely known for his work on behalf of Alabama inmates on death row, also ran a death penalty legal clinic. Students investigated cases of men on death row in Alabama, and they were now at work on Domineque’s case.

Europe had known his brother had run into trouble in Selma. But he had no idea Domineque was facing the death penalty. And he couldn’t understand why he had never been contacted by any lawyers for his brother earlier. When he learned only his mother had testified during the penalty phase, his confusion and upset worsened.

“Maybe they thought my mom was enough, I don’t know,” Europe said. “But it would have been nice if they would have come and reached out.”

In part, he said, because he knew his mother would not tell the whole story of their childhood and her role in it. Europe said his mother, who died in 2012, had asked for forgiveness over the years. But she held her secrets tight. He’s not at all surprised she wasn’t going to disclose them in a public courtroom.

“I don’t think the truth was supposed to be revealed,” Europe said. “I think that was going to be something that was never revealed.

“But I remember it.”

In September 2006, over roughly two hours on the witness stand, Europe told his version of the truth. He was appearing as part of his brother’s appeal for a new trial, or at least a new sentencing hearing. It was not easy. He and his brother, he said in an interview, had never talked about their childhood traumas. He wasn’t eager to have the world know what he had suffered, or at whose hands.

Europe, in interviews and testimony, said there had been bright spots in their lives. Europe, as a student at Southside Middle School in Selma, had dreamed of enlisting in the Navy. He brought home A’s and B’s on his report cards. And while Domineque struggled — he had trouble writing because of a hand injury and didn’t seem to absorb schoolwork — he loved music and was on his school’s dance team, performing hip-hop routines during halftime at sports games. At the age of 13, Domineque got a job at the local animal shelter, where he would spend his days taking care of the city’s abandoned cats and dogs, Europe said. He got into mixed martial arts and worked out at a local youth center under the care of a former boxer

But back at home, his mother had abandoned him for her boyfriends. He’d had sex with friends of his mother’s to help her out financially, a social worker later discovered. And he grew apart from his family.

Domineque wound up done with school after eighth grade. He got into a series of minor scrapes with the law, charged with harassment or trespassing or burglary. And he developed a friendship with Owden — they bonded over karate and Jackie Chan movies — that changed his life forever.

Domineque has always denied ever being abused. He says that his childhood was nothing more than “average,” and that stories of trauma and exploitation are made up. Even his mother’s milder version of his difficult upbringing, he has said, was false, the result of her being on medication.

He was furious with Europe over the testimony he gave as part of a bid to save his life. Europe knows that Domineque is upset with him but maintains that they both lived the life he chronicled on the stand. The two talk by phone occasionally, and Europe hopes to visit his brother before the execution, but he will not attend it. As for whether his brother killed the Mabins and Harville, Europe says he’ll never know. “To be honest with you, I don’t know if he did it or he didn’t,” he said.

“He’s angry at me because I told the truth,” Europe says of his brother. “There were things that, I don’t know, he was ashamed of, or he didn’t want no one to know about, or whatever. But I wanted to give the true statement.”

The Juror: “I Just Hope I Didn’t Make a Mistake”

Once the door of the jury room closed behind them in July 1999, the 12 jurors took an initial vote as to whether to recommend death or life without parole for Ray. Again, 10 votes were needed to recommend death, seven for life.

Angela Rose, one of the jurors, said she and two other women voted to spare Ray. Rose, recalling the deliberations in a recent interview in Selma, said that over the next couple of hours, people took turns making their cases. Several said that a death sentence would ensure Ray would never walk the streets again. They didn’t trust the judge’s promise that if they voted for life without parole, Ray would never be freed.

Rose, along with Sandra Jackson and another woman whose name they couldn’t remember, argued that empathy was required. They said it should be God who dealt with Ray.

“Allow God to work this,” Rose said she told the jurors.

Rose says one of the other jurors quickly shot back something to the effect of “God might just take too long. We need to just go ahead and get this guy off the streets so he won’t hurt anyone else’s child.”

Soon, there were enough votes for death. Jackson, in an interview, said she switched her vote because she was convinced if the jury returned a vote sparing Ray, the judge would have overruled it. The other woman whose name they couldn’t remember joined Jackson, though for what reasons it is not clear.

Rose said she pleaded through tears: “Please, don’t do this. Don’t do this. Don’t do this.”

The jury for Ray’s trial had been selected in the course of a single day. A pool of some 120 people — housewives, retail workers, salesmen, state forestry employees — had been reduced to a panel of eight women and four men, eight of them white, four black. They had been asked questions about their views on the death penalty and if they knew anything about the case.

The performance of Ray’s lawyers during jury selection became one of the many elements of Ray’s appeals. Two jurors had admitted knowing the lead detective on the case, and another said he knew the expert forensic witness who would also be called to the stand by the prosecution. At least three said they had heard or learned about the case. Ray’s lawyers have argued that Whatley’s failure to use any kind of challenge to the seating of those jurors amounted to inadequate counsel.

Nathaniel Holmes Jr., questioned during jury selection, had said he did not know many of the details of the case. Holmes, then 53, is an Army veteran who later worked for United States Postal Service. In an interview, Holmes did say word of Harville’s murder had swept through town. His sister had a local store that sold beer, and she had grown familiar with the teenager, often kicking her out, Holmes said.

Born in Selma in 1946, Holmes shared his name with his father, Nathaniel Holmes Sr., who is said to have been the first black police officer on the city’s force. His mother worked as a seamstress in the city’s downtown.

Holmes, in an interview, said he had never been called for jury duty before and had hoped he would not be chosen.

He recalled making his way to the jury box and realizing he actually hadn’t thought much about the death penalty before. But he remembered ultimately feeling confident he could recommend it, if necessary. It was, he said, an appropriate punishment for those who violated one of the Ten Commandments: Thou shalt not kill.

“Young and black,” Holmes said he first noted upon seeing Ray in court. The 22-year-old sat with his head in his hands, expressionless. Whatley said he had instructed Ray not to show emotion in front of the jury, something Holmes said he took as a sign that he had no remorse.

The deliberations on guilt or innocence did not take long. Rose said some jurors argued that Ray must have killed Harville because he didn’t testify. “He was evil,” one juror remembered thinking. Rose, the woman who held out for sparing Ray, at first refused to find him guilty. To her, Ray’s blank expressions seemed like the look of helplessness and confusion. But she eventually relented, a decision she would not discuss today.

Holmes, having voted to convict, voted for death.

Rose, hearing about Ray’s childhood, said the fuller picture of his life did not surprise her, and she thinks if the jury had heard it in 1999, it might have made a difference. Jackson agreed and now regrets having changed her vote.

In all, ProPublica contacted nine jurors from the case. Two had died, and the other could not be located.