Chris Hedges's Blog, page 262

May 4, 2019

At Venezuelan Protest, Opposition’s Frustration Shows

CARACAS, Venezuela—When a protester handed over a written appeal for the military’s support on Saturday, a Venezuelan policeman burned the document and let the ashes fall to the ground.

The armed forces “won’t be blackmailed or bought,” said a second officer standing nearby.

Benito Rodriguez fumed as he watched the events unfold.

“It’s a humiliation,” said Rodriguez, a demonstrator who had joined a crowd of about 150 protesters gathered near La Casona, a residence historically used by Venezuelan presidents.

The scene highlights the uphill battle now facing opponents of President Nicolás Maduro who have failed to persuade the country’s security forces to join efforts to oust the leader.

The critical role of the Venezuelan military in the country’s crisis was on display Saturday as Maduro tried to portray strength by ensuring that a group of powerful generals maintained their loyalty, while opposition leader Juan Guaidó attempted to woo the armed forces to his side by urging supporters to the streets.

National television showed Maduro wearing a camouflage hat as he shook hands and exchanged fist bumps with security forces during a visit to a military base before watching troops engage in a shooting exercise.

“Loyal forever,” Maduro bellowed to a crowd of cadets in green uniforms.

Guaidó, meanwhile, told backers to go to military garrisons to persuade forces to turn against Maduro, whose years in office have been marked by escalating hardship for most people in a country that was once one of the wealthiest in Latin America.

“The aim is to deliver our message without falling into confrontation or provocation,” Guaidó tweeted.

As demonstrators linked arms and moved toward police, protest leader Maria Suarez urged calm.

“Please, a lot of discipline,” she said.

Others broke the line and went forward to hand over printed documents, saying the military’s role in helping Venezuela emerge from an “unsustainable” situation is vital. Their appeals were printed on presidential letterhead, reflecting Guaidó’s claim to be the country’s rightful leader.

“They think it’s a joke. They don’t take us seriously. They’re not listening,” said demonstrator Andrea Palma after police burned the paper with a lighter.

Divisions among the protesters were evident as some young men from poor neighborhoods scoffed at a speaker who insisted that the gathering must be peaceful.

“It’s the frustration talking,” said demonstrator Mariajose Molina.

The latest displays of will come as the political standoff between Maduro and U.S.-backed Guaidó sinks deeper into a stalemate.

On Tuesday, Guaidó appeared outside a Caracas military base with a small group of security forces and urged the military to overthrow his political rival.

As the leader of the opposition-controlled National Assembly waited, however, it became clear that his call had failed to rally armed forces to his side. Clashes between protesters and police then erupted, leaving five dead.

Maduro’s government has also shown signs of weakness and has not moved to arrest Guaidó, who the United States and over 50 other nations recognize as Venezuela’s rightful leader.

More than three million Venezuelans have left the country to escape a shrinking economy, hyperinflation and shortages of necessities such as medicine.

The opposition blames the sharp decline on state corruption, mismanagement and authoritarianism and says Maduro’s re-election last year was illegitimate. Maduro portrays Venezuela as a victim of U.S. antagonism toward the socialist principles championed by his predecessor, Hugo Chávez.

On Saturday, one protester looked on as the printed proclamation was burned. He then wished the policeman a nice day.

“See you later,” replied the officer before turning away.

American History for Truthdiggers: Civil Rights, a Dream Deferred

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 30th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, who retired recently as a major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 30 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16; Part 17; Part 18; Part 19; Part 20; Part 21; Part 22; Part 23; Part 24; Part 25; Part 26; Part 27; Part 28; Part 29.

* * *

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore. …

Maybe it just sags like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

—Langston Hughes, from his poem “Harlem” (1951)

Rosa Parks sat, Martin Luther King Jr. stood up, the Supreme Court overturned school segregation, and the rest, as they say, was history. African-Americans, long-abused and long-thwarted, ultimately won their civil rights in what has become a defining American story. Only that’s what this is—a story, a mythologized and sanitized past that fails to engage with the complexity of the issues at hand.

According to what American children are taught, the civil rights activists managed a coherent movement; there seldom is mention of the internal battles within the black and white liberal communities. As it is taught, the movement had a discrete chronology, a beginning and an end. It begins with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board or Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat to a white person on a crowded, segregated bus in Montgomery, Ala. It ends, usually, with either the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, or with the King assassination in April 1968. The mythologized movement has a distinctly Southern geography—lost are the riots, poverty and persistent de facto segregation of the urban North.

In learning the patriotic gospel of American civil rights struggle, students are instructed that there was a “good” black movement, fronted by MLK and dedicated to nonviolence; conversely, there was a “bad” movement, associated with Malcolm X and the Black Panthers, a supposedly violent and, ultimately, counterproductive crew. Gone, again, is the nuance, the movement’s gradations and the genuine emotional and intellectual pull of black-power politics and culture. In the traditional yarn, the civil rights movement went just far enough—winning civic but not economic rights—and was wildly successful. In the process, Americans are led to believe, the United States conquered its demons and saved its soul. The nation is thus vindicated and its sins are forgiven. White liberals can continue to sleep well.

What if this popular telling conceals as much as it reveals? It’s possible, in fact, that the history of civil rights struggle in the America of the 1950s and ’60s was always far more contested, angry and radical than is commonly remembered. Taken as a whole, in this way, the pageantry is removed and we can see the civil rights movement as a campaign begun with the arrival of the first slave ships and still being fought today, sometimes out in the streets. In this more honest, if discomfiting, tale, the movement peaked in the 1960s but began far earlier and never really ended. It unfolded, albeit differently, in the North and the South and included equally strong traditions of both nonviolence and armed self-defense on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. In this version of a complex story there are few purely “good” or “bad” activists; indeed, their histories include many gray areas, and much overlap is visible among the traditions of King, Malcolm X and many influential grassroots characters lost to history. This movement, the real movement, unfolded in the streets and dragged along its leaders, white or black, just as often as it was led by them. President John Kennedy (who did not live to see his proposed Civil Rights Act become law), President Lyndon Johnson and King were joined by radical, frustrated students, the sons and daughters of sharecroppers, and even armed black nationalists. The real story is messy and best explained through a re-evaluation of one Rosa Parks.

Parks is often misremembered as an old lady who was just too exhausted to give up a bus seat. It’s the perfect origin story for a prettified movement: an elderly woman—utterly sympathetic—battling unrepentant bigots in the Deep South. Parks, like King—who gained national fame organizing a bus boycott that Parks had started—emerges as a “good,” almost grandmotherly activist. In reality, Parks was only 42 years old at the time of the first of her two arrests, was a woman of great purpose and certainly was not soft or anyone’s pushover; she was a lifelong activist and far more “radical” than most Americans know. She began her career in activism protesting the trumped-up conviction of the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930s. She attempted to vote as early as 1943, turned away time and again until she succeeded in registering in 1945. By 1949 she was an NAACP youth leader, then secretary to E.D. Nixon, head of the Montgomery NAACP. Just before the bus incident and subsequent bus boycott, Parks attended a training session for direct-action activists in Tennessee.

Parks, in 1992, challenged the notion that she was meek and harmless, stating, “People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically. … I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.” Rosa Parks was, so to speak, a baddass—a social justice warrior in her own right. And her courage and commitment spurred a movement that vaulted a 26-year-old Baptist minister, Martin Luther King Jr., to international prominence. Indeed, as one contemporary claimed, “If Mrs. Parks had gotten up and given that cracker her seat, you’d never heard of Reverend King.” That’s probably true. Parks, though, was a woman, and even in the civil rights community women often remained second-class citizens. During the famous bus boycott that she had singlehandedly kicked off, she mostly answered phones and did secretarial work within activist operations. Also forgotten is that she lost her job and suffered economic insecurity due to her brave stand—demonstrating, importantly, that there always was, and is, an economic component to civil rights activism.

The facts of Parks’ long career poke holes in the legend built around her. Years after the Montgomery bus boycott, she and her husband left the South and moved to urban Detroit. Entering the supposed promised land of the non-Jim Crow North, she found no need to quit fighting for justice. Parks lived out her life (she died in Detroit in 2005 at the age of 92) as an urban activist, protesting segregation, corporate downsizing and South African apartheid. She refused to fully rebuke the black rioters of the mid-to-late 1960s. She admired Malcolm X and claimed he, not MLK, was her hero! She was an early opponent of the Vietnam War and attended black-power conferences in 1968 and 1972. A believer in self-defense, she had kept guns in her home when she lived in Alabama. After King was assassinated in 1968 she attended his planned Poor People’s March to fight for economic justice. By the 1970s she had taken to dressing in African-style clothing, and in the decades before her death she would lobby for reparations to black Americans. Parks lived and died a crusader. She, and the movement of which she was a part, was always far more complex, divided and radical than the picture presented in watered-down accounts.

The ‘Long’ Civil Rights Movement

By the end of World War II, the lot of black Americans had not improved much over the previous 70 years. Abandoned by Northern “liberals” at the end of Reconstruction (1877), blacks largely fended for themselves in a harsh world, especially in the systemically segregated Deep South. Still, their struggle and quest for civil (and human) rights never stopped. Undeniably, progress was slow, and the movement, such as it was, had peaks and valleys. In the hyper-sensitized Red Scares of the 20th century, black civil rights activism was dismissed or attacked as communistic. The influence of communism on activists was always exaggerated, but many black political and cultural leaders were sympathetic to the Reds and the Soviet Union. After all, only the Communist Party insisted on racial justice as part of its platform, and it was the party that became associated with the legal defense of the Scottsboro Boys. In the 1930s, the Communists even ran a black man for vice president. In these ways, the Communists were far ahead of the U.S. political mainstream on the civil rights issue. As the esteemed historian Howard Zinn wrote, “The Negro was not as anti-Communist as the white population. He could not afford to be, his friends were so few.”

White America was quick to apply the broad brush of communism to black activists. In 1949, after Jewish residents of Peekskill, N.Y., were deemed responsible for inviting the black singer Paul Robeson, alleged to be a member of the Communist Party, to perform, Gentiles rioted and attacked concertgoers. Robeson was subsequently put under constant government surveillance, and his phone was bugged, his mail was intercepted and his passport was seized, making it impossible for him to travel abroad. The civil rights movement was also initially linked to the labor movement. From the start, black organizers critiqued the economic system that kept their people largely impoverished and sought allies within the labor movement. They managed some successes, but Operation Dixie, a postwar attempt to unionize the labor-hostile South, faltered under charges of communist infiltration. It was an old, if effective, game: equate civil rights activism with global communism and thus maintain the bigoted status quo. Amid fear of the stigma of communist association, the push for civil rights moved away from unions. By the mid-1950s, the churches had become the key institutions of civil rights protest. However, with many churches focusing on the moral aspects of racism, the economic components of the mission often were softened.

After the Supreme Court overturned school segregation (1954) and after Rosa Parks and others had won a legal right to keep a seat on a bus, black life in America was disturbingly similar to that of a century earlier. In the South, only a token few blacks were permitted to vote, every public institution was segregated and many newspapers wouldn’t even print black persons’ names—for example printing that “Joe and Jane Doe were killed, and two negroes.” North and South, black unemployment was double the white average; half of all blacks lived in poverty, even during the boom years of the 1950s. Some key unions even virtually barred blacks from membership. The school systems of the South were the ultimate symbol of inequality. In 1945, South Carolina spent three times as much per pupil on its white schools as it did on black ones; Mississippi was even worse, spending four and a half times as much on white students. Black school years tended to be shorter, and teachers in black schools were paid less. All this put to lie the Jim Crow doctrine of “separate but equal.”

Why Now?: A Second Reconstruction

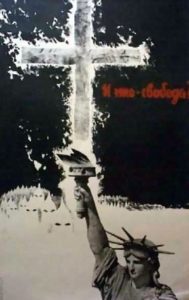

A Soviet political cartoon depicting the Statue of Liberty’s torch lighting the flame of a Ku Klux Klan cross. The image contains the Russian words for “Shame on America.”

After moving along at more or less a steady rate in the first half of the 20th century, activism and protest exploded in the 1950s and picked up even more energy throughout the 1960s. It’s important to consider why this was, for it was no accident. Two factors, above all, contributed to the breakout of civil rights activism in the period: Cold War considerations and the now ubiquitous medium of television, which broadcast across the world the images of black protest and white backlash. The Soviets—though flawed messengers themselves—were correct in their criticism of American race relations and gloried in spreading propaganda on the topic throughout the developing nations. This Soviet effort worked. U.S. hypocrisy on race and the country’s regular meddling in post-colonial affairs won Washington few friends in the recently imperialized Global South. Indeed, the U.S. government knew this and was growing concerned, and a bit embarrassed, by the bad press that the Jim Crow South was earning America. President Harry Truman’s Committee on Civil Rights concluded, as early as 1946, that “[w]e cannot escape the fact that our civil rights record has been an issue in world politics. … Those with competing philosophies have stressed our shortcomings … they have tried to prove our democracy an empty fraud.” Which it largely was—after all, blacks couldn’t even vote in half the country!

Though slavery had ended in 1865 and Reconstruction had initially brought much progress, no blacks had served in Congress between 1905 and 1929. No black Southerners served between 1891 and 1987! National security experts and leaders in both the Truman and Eisenhower administrations were becoming seriously concerned that American bigotry was a liability in the global fight against communism. Media images, especially television images, of police dogs attacking black protesters and other atrocities also garnered the sympathy of many white Americans and only further embarrassed the U.S. on the world stage. Finally, with the accession of Earl Warren as Eisenhower’s chief justice of the Supreme Court, the judicial branch of government began dismantling the legal superstructure of Jim Crow segregation, beginning with the ruling against school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Then, in tiny Money, Miss., a white posse in 1955 abducted and murdered a 14-year-old boy from Chicago for allegedly “whistling at a white woman.” Emmett Till was visiting relatives at the time and received a fatal lesson in the social mores of the Deep South. His mutilated and bloated body, found in a river, was shipped back north to his mother. In a moment of profound courage and consequence, his mother decided on a public, open-casket funeral, displaying for the world what the attackers had “done to her boy.” No one was ever convicted of the crime, and the female “victim” of the alleged whistling later would recant, changing her story about Emmett Till’s actions in the 1955 encounter. The case was a national and international sensation, and it brought about a major outbreak of protest and activism.

Whose Civil Rights Movement?: Top-Down and Grassroots Interpretations

In the standard telling, the civil rights movement was spearheaded by “great men” such as Martin Luther King, Jack Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Understood thus, only the “good,” moderate civil rights leaders mattered, and it was they who accomplished great things. In reality, the civil rights movement was very much a grassroots program, and anonymous black (and some white) activists more often than not forced national political leaders to countenance change. Major figures, including presidents and judiciary members, often responded to the grassroots activity in the streets and not the other way around. The “great men” were usually behind the curve on civil rights and remained wary of “too much change too fast.” It took the sacrifices of the street protesters—who often risked bodily harm and arrest—to force national leaders into action.

Even the court decision in Brown v. Board was sparked by the willingness of average black citizens across the country to open lawsuits with the help of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the NAACP. This took courage, and many litigants were threatened in their home communities. In the next major event, the Montgomery bus boycott, Rosa Parks and then MLK may have become symbols of the protest, but it was accomplished only through the activities of thousands of average black citizens who, lacking bus service because of the boycott, organized carpools or walked long distances to work for an entire year. Without this direct-action activism, the court would have been unlikely to rule against segregation on public transportation, as it did in 1956.

An interesting dynamic between the grassroots and top-down interpretations occurred during the school integration controversy during 1957 in Little Rock, Ark. When Gov. Orval Faubus refused to allow nine black high school students to attend the city’s Central High School—he deployed state National Guard troops to block the students—President Dwight Eisenhower and the federal government faced a serious constitutional challenge. Ike, contrary to popular conception, was no friend of the civil rights activists. The president had served out a career in a segregated Army and had even opposed Truman’s order to desegregate the armed forces after World War II. Eisenhower opposed the Brown decision and the entire notion of using federal law to alter race relations in the South. He stated, “The improvement of race relations is one of those things that will be healthy and sound only if it starts locally. … I believe that Federal law imposed upon our states … would set back the cause of race relations a long, long time.” The flaw in his thinking seems obvious in retrospect: The former Confederate states had shown zero willingness to change for nearly a hundred years, and there was no indication that they would change anytime soon, at least without massive protests.

Eisenhower even sympathized with and normalized Southern bigotry. When Ike invited Chief Justice Earl Warren—a liberal on race relations—to the White House, he sat him next to John W. Davis, the attorney fighting against integration in the ongoing Brown court case. Eisenhower leaned over to Warren and said of the intransigent Southern politicians: “These are not bad people. All they are concerned about is to see that their sweet little girls are not required to sit in school alongside some big overgrown Negro.” Civil rights just was not a national priority in the 1950s. In the 1956 presidential election, neither Eisenhower nor his opponent, Democrat Adlai Stevenson, talked very much about the issue at all. Ike, before the Little Rock crisis, had even stated, “I can’t imagine any set of circumstances that would ever induce me to send federal troops into any area to enforce the orders of a federal court, because I believe that the common sense of America will never require it.” Just months later, he would be proved wrong about the “common sense” of Americans.

A 1959 rally at the Arkansas Capitol to protest the integration of Little Rock Central High School. Demonstrators carried signs reading “Race Mixing Is Communism” and “Stop the Race Mixing March of the Anti-Christ.” (Wikimedia Commons)

Eisenhower, true to his constitutional duties, eventually did intervene, even if his sympathies never laid with the civil rights movement. When matters spiraled out of control in Little Rock, and mobs attacked children, random blacks and “Yankee” reporters, Ike federalized the Arkansas National Guard and deployed 1,100 active-duty Army paratroopers to protect the nine students and integrate the school. He did so under a “constitutional duty which was the most repugnant to him of all his acts in his eight years in the White House,” according to a top aide. Eisenhower was also probably motivated by the international blowback as TV images of innocent black children being harassed by angry mobs flashed across the world. Once again, America appeared wildly hypocritical and vindicated the Soviet critique of the U.S. The paratroops would, in a remarkable turn of events, stay in place until November, and the National Guard remained on site for the entire school year. Ike had finally, if reluctantly, acted, but in an oft-forgotten postscript Gov. Faubus got the last laugh. He simply closed all Little Rock schools for the following academic year, 1958-59, rather than see desegregation continue. Southern backlash was alive and well despite the ruling of the court and the deployment of federal soldiers.

King and his newly formed—if ill-organized—Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) would continue to spread headline-grabbing activism around the South after the Montgomery bus boycott, but here again King was very much only a figurehead for a decidedly grassroots movement. It was black college students, many of whom were members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), who drove the movement forward. They began by conducting sit-ins at segregated lunch counters and eventually rode segregated Greyhound buses throughout the South to protest (already illegal but rarely enforced) segregation in interstate transportation. In these acts, the students captured the (televised) attention of many white liberals, but they also faced extreme violence and received scant protection from a reluctant Kennedy administration. During the rides, a bus was firebombed in Anniston, Ala., and dozens of “freedom riders,” as they were dubbed, were arrested and made to serve significant jail time—some at the infamously brutal Parchman Farm Penitentiary’s maximum-security wing in Mississippi.

In 1963, King took his movement and growing personal fame to Birmingham, Ala., one of the most segregated and violent cities in the South. Known colloquially as “Bombingham,” the city was the site of more white terror bombings than any other Southern locale. The intensely bigoted local police chief, Bull Connor, played right into the hands of King and the grassroots activists in the city, siccing attack dogs on peaceful black protesters and firing water cannons at the demonstrators. The televised images horrified millions of white Americans, including, reportedly, President Kennedy. Indeed, in the aftermath of Birmingham, Kennedy would feel obliged to introduce a civil rights bill in Congress. Reflecting on the counterproductive role of Connor, JFK stated, “The civil rights movement should thank God for Bull Connor. He’s helped as much as Abraham Lincoln.”

That same year, King helped organize the massive March on Washington to generate pressure for civil and economic rights for blacks. Even here, though, the grassroots found itself in tension with the movement and national political leadership. The Kennedy administration acceded to the march, but co-opted and de-radicalized it. It could last only one day, administration officials decreed, and even the speeches were sanitized. For example, SNCC leader John Lewis was coerced into moderating the angry speech he had written and eliminating key components. The march was officially titled “The March for Jobs and Freedom” (emphasis mine), but in our collective memory the jobs component, the economic side of the movement, has been erased in favor of civil rights such as voting and integration.

Another split between the grassroots and top-down leaders occurred during the 1964 presidential primary season. When the Mississippi Democratic delegation refused to seat any black members—despite almost half of the state population being black—SNCC members and other activists formed their own party, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) and crashed the party convention in Atlantic City, N.J. Despite impassioned speeches from MFDP leader Fannie Lou Hammer, the delegation was denied seats and forced into a humiliating compromise by President Lyndon Johnson and the party leadership. In reaction, many SNCC and MFDP activists forever lost faith in white liberals, establishment politicians and even the nonviolent movement leaders such as MLK. Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture), a fiery Trinidadian SNCC leader from the North, complained in 1965 about King and his SCLC. Feeling abandoned by these national leaders, an increasingly radicalized Carmichael stated:

Here comes the SCLC talking about mobilizing another 2-week campaign, using our base and the magic of Dr. King’s name. … They’re going to bring the cameras, the media, prominent people … turn the place upside down and split. Probably leaving us sitting in jail. That was the issue, a real strategic and philosophical difference.

Such tensions within the movement—often based on generational differences—would remain a key factor in an increasingly divided black activist base. Indeed, soon after the MFDP fiasco, SNCC would vote to remove all its white members.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 did eventually pass, after Kennedy’s assassination in November of the previous year, and blacks achieved their goal of desegregation (but not necessarily integration). Still, the bill did nothing to address voting rights, which were still denied to the vast majority of blacks in the South. In response, both the SCLC and the more radical SNCC descended on Selma, Ala., to protest for a voting rights act. King grabbed the headlines, but it was John Lewis and numerous grassroots activists who bore the burden of police violence when they attempted to ceremoniously march on the Capitol in Montgomery. Lewis’ skull was fractured by a police baton, and dozens of others also were seriously injured. This was now 1965, a full 10 years since the Brown decision, and the intransigence of Southern whites remained strong as ever. Still, the horrifying images out of Selma goaded President Johnson into action: He pushed the Voting Rights Act through Congress by year’s end.

Most civil rights histories end there, with the achievement of the two key pieces of congressional legislation, but the movement carried on. Legislation was one thing, but actual implementation of integration and voting rights required ever more protest across the South throughout the 1960s and ’70s. King kept fighting, even planning a poor people’s movement to march on Washington to fight against systemic poverty and for the economic components of civil rights. SNCC leaders went to Mississippi and Alabama to conduct voter registration campaigns in these deepest of the Deep South states. All were met with violence and arrest. Yet the grassroots activists kept fighting. In a sense, the true odyssey of civil rights was their story.

Rethinking Black Power

If we must die, let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot. …

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

—From the poem “If We Must Die,” by Claude McKay

Black power. Black nationalism. The Black Panthers. The very terms now carry deeply pejorative connotations. The common belief is that as the 1960s progressed, the “good” civil rights movement of Dr. King was overtaken by the “bad” movement of black-power activists such as Carmichael, Malcolm X and, eventually, the Black Panthers. These activists are considered violent, reverse racists and counterproductive to the civil rights cause. This is simply untrue. Black power, and black nationalism, had always been powerful elements of the “long” civil rights movement. Indeed, the twin tracks of the nonviolence of King and armed black self-defense always existed side by side and remained vital twin components of a diverse movement.

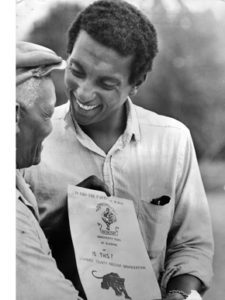

Stokely Carmichael organizing in Alabama’s Lowndes County in 1966. The flyer he is holding features the black panther logo of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. (Wikimedia Commons)

To understand the true origins of black power and the complex nature of the Black Panther movement, we must begin in the extremely poor and violent majority-black community of Lowndes County in Alabama. The county first came to the attention of SNCC during the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery march, which passed through it. The organization quickly traveled to the area to attempt a new approach to protest. In an internal SNCC strategy memo, the group described how it intended to take power in majority-black communities around the South, beginning in Lowndes County. In the memo, SNCC asked:

When you have a situation where the community is 80% black, why complain about police brutality when you can be the sheriff yourself? Why complain about substandard education when you could be the Board of Education?

… Why protest when you can exercise power?

So it was that SNCC flooded into the poor, majority-black communities of the county and—in the face of loathing by the white-dominated Democratic Party—formed its own political party, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). It chose as a symbol of bold determination the black panther. Encouraged by the results of the Alabama intervention, the later Black Panther Party for Self Defense (BPP) would be formed in Oakland, Calif., and spread across urban communities throughout the nation.

The LCFO and its Black Panther logo were never about violent aggression, but rather black empowerment, self-defense and voting rights. The move toward black power was driven, primarily, by white intransigence. Massive violent backlash, local refusal of Southern white communities to follow court integration orders and the unwillingness of establishment political figures to protect or support the movement drove the young activists in radical directions. Carmichael (in a film discovered years later) articulated the frustration among the young activists when he stated, “Dr. King’s policy was that nonviolence would achieve the gains for black people. … He only made one fallacious assumption: In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none.” Once—on stage with MLK—he famously declared, “The time for running has come to an end. You tell them white folk in Mississippi that all the scared niggers are dead.”

Lowndes County proved a tough nut to crack. In 1906, W.E.B. Du Bois declared that “outside of some sections of the Mississippi and Red River Valley, I do not think it would be easy to find a place where conditions were more unfavorable to the rise of the Negro.” A 1903 report from a U.S. district attorney claimed that “Lowndes County is honeycombed with slavery.” Whereas in 1900, Lowndes County had 5,000 black registered voters, after the arrival of Jim Crow legislation there were only 57 registered in 1906. Matters had changed little by 1965. Still, Carmichael and SNCC brought enthusiasm into their voting rights campaign. He exclaimed, “We’re going to tear this county up. Then we’re going to build it back, brick by brick, until it’s a fit place for human beings.”

Whites fought back ferociously in Lowndes. One white mother declared that “Niggers in our schools will ruin my children morally, scholastically, spiritually, and every other way.” White mobs and posses murdered many activists, including the Rev. Jonathan Daniels, a white man. In response, members of the LCFO armed themselves and prepared to fight back. One resident exclaimed at the time that “[y]ou can’t come here talking that non-violence shit. You’ll get yourself killed and other people too.” It took a few years, and much effort, but the LCFO eventually took power in Lowndes County, even electing a black sheriff! Inspired by the empowerment of rural blacks, the BPP in Oakland adopted the panther logo and the Carmichael doctrine of black power.

Throughout Northern urban areas, the Black Panthers armed themselves (usually legally) and followed and observed the police for instances of brutality. Ironically, they fought against gun control in California, and conservatives, led by Gov. Ronald Reagan, were the ones pushing for such legislation! While there were acts of violence committed by the Panthers, their work spanned many areas, including community organizing and the distribution of free breakfasts to black urban children. An outgrowth of black power was a cultural component that sought to convince Americans that “black is beautiful.” Black women and men turned their back on white notions of beauty and began wearing their hair naturally in “afros” and donning Afro-centric clothing. Many, including Carmichael (Kwame Ture) and the boxer Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali), took Islamic or African names rather than continue to accept their given “slave” names. Black power was an influential movement from the start and gained ever more adherents in the black community—including Rosa Parks—with the arrival of the 1970s. Indeed, it was government backlash and suppression of the Panthers and other black nationalists that ultimately squashed this prominent movement. Black power was then demonized by many history teachers and key political figures and was non-organically stripped away from the “good” civil rights activism of Dr. King. Still, King was never as centrist as his hagiographers had claimed.

The Radical King: Reimagining the Man and the Movement

Martin Luther King Jr. was never as moderate or popular as is commonly remembered. Dozens of U.S. senators (John McCain among them) would vote against designating his birthday a national holiday. King was polarizing in his time, hated in the white South and demonized as a communist by many conservative Northerners. Then something changed. By the late 1980s, King was canonized as the “good” or peaceful leader of the civil rights movement and placed on a national pedestal in juxtaposition with the “bad” activists such as Stokely Carmichael, Malcolm X and the Black Panthers. In truth, however, there was never as much distance between King and the emboldened “black power” activists as is commonly believed. MLK was radical—for his time and even based on contemporary standards. Yet this salient fact has been erased from memory in favor of the de-radicalized King of public memory.

King eventually broke out of his simple, nonviolent image, and even though he never called for violence, gradually radicalized ever further in opposition to white intransigence. King always had an economic component to his activism. He recognized that official integration alone would never solve the inherent problems of black poverty and unemployment. In 1967, he stated, “Let us be dissatisfied until the tragic walls that separate our outer city of wealth and comfort from the inner city of poverty despair shall be crushed by the forces of justice. Let us be dissatisfied until slums are cast into the junk heaps of history, and every family will live in a decent sanitary home.” King also refused to abandon black rioters who exploded with anger toward their generational poverty and police brutality in Northern urban cities. In 1968, he declared that “I’m absolutely convinced that a riot merely intensifies the fears of the white community … but it is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots … without condemning the intolerable conditions that exist in our society. … And I must say tonight that a riot is a language of the unheard.” LBJ’s Advisory Committee on Urban Disorder agreed, stating in its official report that “white racism and an explosive mixture which has been accumulating in our cities … pervasive discrimination and segregation in employment, education, and housing” were to blame for the riots.

King even criticized capitalism itself. He went on the record, stating, “Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all of God’s children.” MLK had long stated that American society was afflicted by “three evils”—racism, imperialism and hyper-capitalism. By 1967, King would openly oppose the Vietnam War, which he had long despised privately. In a speech at the Riverside Church in New York City, he referred to the United States as “[t]he greatest purveyor of violence in the world today,” adding, “my own government, I cannot be silent.” He also stated that he saw the war as “unjust, evil, and futile.” When King stepped out of the pure civil rights arena into larger critiques of capitalism and American imperialism, he was lambasted by the mainstream media, including The New York Times. At the time of his 1968 death—which occurred when, as few now remember, he was rallying support for the Memphis sanitation company union during a visit to the Tennessee city—close to half of Americans, and nearly all conservatives, had a negative view of him. When MLK was assassinated he was far from the widely adulated figure he would later become.

Opportunities Lost: What the Movement Didn’t Address

In this Pulitzer Prize-winning photo, taken in Boston in 1976 by Stanley Forman of the Boston Herald American newspaper and titled “The Soiling of Old Glory,” a protester against court-ordered busing of schoolchildren attacks an African-American. (Wikipedia / Fair Use)

The civil rights movement’s successes were fought and stalled at every moment by intransigent whites both north and south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Ultimately, this white backlash would stymie the largest goals of the movement and ensure that civil rights legislation didn’t go far enough. So what did the 1950s-’60s activism achieve? Well, it ended de jure segregation of public facilities—though it would take until 1969 for most Southern schools to adhere to 1954’s court desegregation order. It gave blacks the franchise in the South. These were real achievements, but they hardly scratched the surface of white supremacy in America.

First, the FBI infiltrated and destroyed black power movements through the COINTELPRO program, which focused on crippling black radicals. The bureau even tapped the “moderate” MLK’s phone and sent him an anonymous letter encouraging him to commit suicide. In an internal FBI memo, King was labeled “the most dangerous Negro in the future of this nation from the standpoint of communism and national security.” The FBI later colluded with the Chicago police to assassinate the Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, riddling his body with bullets while he lay in bed. This federal backlash combined with white Southern backlash to limit the achievements of the civil rights movement.

Also, key figures in the civil rights cause were assassinated in the 1960s, including Malcolm X, John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy and, of course, Dr. King. In addition, Northern whites were scared off by the violence of the urban riots of the period and began to culturally and politically shift to the Republican Party.

So where did the movement ultimately falter? Simply put, King and other activists achieved civil rights but never conquered latent racism or economic inequality. That failure ensured that the cause and relative position of American blacks would, ultimately, change very little in the aftermath of the 1960s. Black Americans remain an underrepresented and impoverished racial caste even in the 21st century. In that sense, the movement and the need for it never really ended—even if it disappeared from the mainstream media. Consider how little changed in the aftermath of the movement’s climactic period. In 1977, despite the earlier passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, in the 11 Southern states there were still zero black senators and only two black congressmen. Though 20 percent of the population, blacks were only 3 percent of elected officeholders. Unemployment among black youths remained as high as 34 percent.

The share of black children attending (de facto) segregated schools only dropped from 76.6 percent in 1968 to 74.1 percent in 2010. In 2010, a study conducted by UCLA on the topic of segregation found that 74 percent of blacks still attended majority nonwhite schools; 38 percent attended intensely segregated schools (those with only 0 to 10 percent of whites enrolled; and 15 percent attended “apartheid schools,” where whites make up 0 to 1 percent of the student body. By contrast, white students typically attend school where three-fourths of their peers are white. The criminalization of the black body has also proceeded without respite. Today, the United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world—mostly based on low-level drug offenses—much higher than even in Russia and Cuba. However, black males in America have an incarceration rate eight times higher than the rate of Cuba, the next worst country on this ignominious list. And as the publicity about police violence toward blacks has demonstrated, and the Black Lives Matter movement has proved, the U.S. is far from done with its racial problems.

* * *

“We have just lost the South for a generation.” —President Lyndon B. Johnson, after signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964

President Johnson is said to have spoken the words above to an aide after he signed the Civil Rights Act. LBJ, a Texan, had known that his pushing for black civil rights would alienate Southerners and drive them into the Republicans’ arms. And so it came to pass. After the limited successes of the civil rights movement, white America lashed out and turned against the causes of black activists. When schools attempted busing programs to comply with court orders to integrate schools, white parents—especially in the North—fought back, attacking black students and protesting until the programs were shut down. There was also a Republican renaissance, as the GOP rode white backlash to victories in five out of six presidential elections after 1968. The solid Democratic South transformed into the solid Republican South over the course of just eight years, between 1964 and 1972. The Old Confederacy would be a conservative Republican base.

Black Americans remain uniquely poor and oppressed among America’s many minority groups, with the possible exception of Native Americans living on reservations. What the 1950s-’60s movement did not do was address the massive wealth inequality and black subjection to police violence that continue to characterize urban black communities. America is just about as segregated now as it was in 1960. Officially, Jim Crow is dead, but the concept lives on in America’s segregated schools and neighborhoods on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. Though the movement for civil rights (and economic fairness) appears to be gaining steam again, we should never underestimate the white capacity for backlash and resistance. It’s 2019, and Donald Trump is president. Clearly the movement didn’t go far enough.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

• Gary Gerstle, “American Crucible: Race and Nation in the 20th Century” (2001).

• Jill Lepore, “These Truths: A History of the United States” (2018).

• James T. Patterson, “Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974” (1996).

• Howard Zinn, “The Twentieth Century” (1980).

Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a retired U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

Under Heavy Rocket Fire, Israeli Reprisals Kill 3

GAZA CITY, Gaza Strip—Palestinian militants on Saturday fired over 200 rockets into Israel, drawing dozens of retaliatory airstrikes on targets across the Gaza Strip in a round of intense fighting that broke a monthlong lull between the bitter enemies. Three Palestinians, including a mother and her baby daughter, were killed, while three Israelis, including an 80-year-old woman, were wounded by rocket fire.

The fighting came as leaders from Hamas, the militant group that rules Gaza, and the smaller armed faction Islamic Jihad, were in Cairo for talks with Egyptian mediators aimed at preventing a fraying cease-fire from collapsing altogether.

It also comes at a sensitive time for Israel, which is to mark its Memorial Day and Independence Day holiday this week, before hosting the Eurovision song contest in the middle of the month. Heavy fighting could overshadow the Eurovision and potentially deter international travelers from coming in for the festive song contest.

Israel and Hamas, an Islamic group that opposes Israel’s existence, have fought three wars and dozens of smaller flare-ups of violence since Hamas seized control of Gaza in 2007. They engaged in several days of heavy fighting in March before Egypt brokered a truce in which Israel agreed to ease a crippling blockade on Gaza in exchange for a halt in rocket fire. In recent days, Hamas accused Israel of reneging on its pledges as militants began to fire rockets into Israel.

In a familiar scene, air raid sirens wailed across southern Israel throughout the day and into the evening as barrages of rockets were repeatedly fired. Retaliatory airstrikes caused large explosions to thunder across Gaza, as plumes of smoke rose into the air. Outgoing Palestinian rockets left long trails of smoke behind them.

Gaza’s Health Ministry said a 14-month-old girl, Seba Abu Arar, was killed in an Israeli airstrike that hit their home in east Gaza City. Her pregnant mother, 37, was severely wounded and died later at the hospital, the ministry added. Another child was moderately injured.

“They were sitting at the yard in their house with their mother. They were shocked by a missile landing on them,” said Abu Nidal Abu Arar, a relative living next door. “This occupation is criminal.”

In Israel, medical officials said an 80-year-old woman was severely wounded by rocket fire, a 50-year-old man was moderately wounded by shrapnel and a teenage boy was mildly hurt as he ran for cover.

In the morning, Gaza’s Health Ministry said a 22-year-old Palestinian man was killed by an Israeli airstrike, and 13 other Palestinians were wounded. Israeli police said a house in the coastal city of Ashkelon was damaged.

The Israeli military accused the Iranian-backed Islamic Jihad of instigating the latest round of violence by shooting and wounding two Israeli soldiers Friday. It said the shooting was not coordinated with Hamas, but said it holds Hamas, as the territory’s ruling power, responsible for all fire emanating from Gaza.

By nightfall, the army said militants had fired well over 200 rockets into Israel. It said dozens of the rockets were intercepted by its Iron Dome rocket-defense system. But it closed roads near the Gaza border to civilian traffic and closed a popular beach as a security precaution.

The military said it struck over 70 targets in Gaza, including Hamas and Islamic Jihad military compounds and a “high-end Islamic Jihad tunnel” that it said crossed the border and was built to carry out an attack inside Israel. Late on Saturday, an airstrike hit a six-story commercial and residential building. Journalists said the building housed the office of Turkey’s news agency Anadolu. There was no immediate comment from the Israeli military.

COGAT, the Israeli defense body responsible for Palestinian civilian affairs, said it was closing the fishing zone off Gaza’s coast altogether and sealing Israel’s two land crossings with Gaza. The crossings are used by Palestinian medical patients to enter and exit the territory, and provide the main entry for cargo into the blockaded territory.

The European Union’s ambassador to Israel, Emanuele Giaufret, sharply criticized the rocket attacks on Twitter, saying “firing indiscriminately against civilians (is) unacceptable.”

Islamic Jihad, which sometimes acts independently of Hamas, threatened to fire longer range rockets toward Israel’s heartland. In a video that also was seen an implicit claim of responsibility, it showed archived footage of militants attaching warheads to rockets.

Israel and Egypt have maintained a crippling blockade on Gaza since Hamas seized control of the territory in 2007.

expanding a fishing zone off Gaza’s coast, increasing imports into Gaza and allowing the Gulf state of Qatar to deliver aid to cash-strapped Gaza.

But like previous Egyptian-mediated agreements, those understandings have shown signs of unraveling in recent days.

On Friday, two Palestinians were fatally shot by Israeli forces during the weekly protests along Israel-Gaza perimeter fence. Palestinian militants also shot and wounded two Israeli soldiers along the border fence. No group claimed responsibility for the shooting. In response, Israeli aircraft carried out retaliatory strikes, killing two Hamas militants.

Hamas has hoped that Egyptian mediators could further ease the blockade, which has ravaged Gaza’s economy. For over a year, the Islamic group has orchestrated mass demonstrations each week along the Israeli frontier to draw attention to Gaza’s plight. More than 200 Palestinians and an Israeli soldier have been killed in the border protests.

North Korea Fires Several Short-Range Projectiles Into the Sea

SEOUL, South Korea—North Korea fired several unidentified short-range projectiles into the sea off its eastern coast on Saturday, the South Korean Joint Chiefs of Staff said, a likely sign of Pyongyang’s growing frustration at stalled diplomatic talks with Washington meant to provide coveted sanctions relief in return for nuclear disarmament.

South Korea’s military has bolstered its surveillance in case there are additional weapons launches, and South Korean and U.S. authorities are analyzing the details.

If it’s confirmed that the North fired banned ballistic missiles, it would be the first such launch since the North’s November 2017 test of an intercontinental ballistic missile. That year saw a string of increasingly powerful weapons tests from the North and a belligerent response from President Donald Trump that had many in the region fearing war.

The South initially reported Saturday that a single missile was fired, but later issued a statement that said “several projectiles” had been launched and that they flew up to 200 kilometers (125 miles) before splashing into the sea toward the northeast. Experts say the North may increase these sorts of low-level provocations to apply pressure on the United States to agree to reduce crushing international sanctions.

The launch comes amid a diplomatic breakdown that has followed the failed summit earlier this year between Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un over the North’s pursuit of nuclear bombs that can accurately target the U.S. mainland. The North probably has viable shorter-range nuclear-armed missiles but still needs more tests to perfect its longer-range weapons, according to outside analysts.

Trump said Saturday that he still believes a nuclear deal with North Korea will happen. He tweeted that Kim “fully realizes the great economic potential of North Korea, & will do nothing to interfere or end it.”

Trump added: “He also knows that I am with him & does not want to break his promise to me. Deal will happen!”

White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders said in a statement that the United States was aware of North Korea’s actions and would continue to monitor the situation.

South Korea said in a statement it’s “very concerned” about North Korea’s weapons launches, calling them a violation of last year’s inter-Korean agreements to reduce animosities between the countries. The statement, issued after an emergency meeting of top officials at the presidential Blue House in Seoul, also urged North Korea to stop committing acts that would raise military tensions and join efforts to resume nuclear diplomacy.

North Korea wants widespread sanctions relief in return for disarmament moves that the United States has rejected as insufficient. In a sign of Pyongyang’s growing frustration, it has recently demanded that U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo be removed from nuclear negotiations and criticized national security adviser John Bolton. North Korea said last month that it had tested a new type of unspecified “tactical guided weapon.”

North Korea could choose to fire more missiles with longer ranges in coming weeks to ramp up its pressure on the United States to come up with a roadmap for nuclear talks by the end of this year, said Nam Sung-wook, a professor at Korea University.

“North Korea wants to say, ‘We have missiles and nuclear weapons to cope with (U.S.-led) sanctions,'” said Nam. “They can fire short-range missiles a couple more times this month, and there is no guarantee that they won’t fire a medium-range missile next month.”

During the diplomacy that followed the North’s weapons tests of 2017, Kim said that the North would not test nuclear devices or ICBMs. These short-range projectiles don’t appear to violate that self-imposed moratorium, and may instead be a way to register Kim’s displeasure with Washington without having the diplomacy collapse.

South Korea’s liberal president, Moon Jae-in, has doggedly pursued engagement with the North and is seen as a driving force behind the two summits between Trump and Kim.

South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha talked by phone with Pompeo about the North Korean launches, Kang’s ministry said in a statement. The ministry also said that South Korea’s chief nuclear envoy, Lee Do-hoon, had a telephone conversation with Stephen Biegun, the U.S. special representative for North Korea who is scheduled to travel to Seoul next week for talks.

Japan’s Defense Ministry said the projectiles weren’t a security threat and didn’t reach anywhere near the country’s coast. Japan will likely avoid any harsh response as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe seeks to secure his own summit with Kim.

___

Associated Press writer Mari Yamaguchi in Tokyo contributed to this report.

May 3, 2019

Can We Trust Billionaires to Save Democracy?

There’s no denying that Nicolas Berggruen, the German American billionaire founder and president of the private investment company Berggruen Holdings as well as the think tank Berggruen Institute, has benefited from a global capitalist system that has fueled historic inequality. But even he can see how broken the current economic and political systems in place in the West are, so he’s come up with a plan to try to revamp democracy as we know it.

Think of it as “universal basic capital instead of universal basic income,” Berggruen tells Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer in a discussion about the billionaire’s book, “Renovating Democracy: Governing in the Age of Globalization and Digital Capitalism.” What Berggruen advocates for is a fresh restructuring of democratic governance frameworks that would guarantee adequate living conditions for workers regardless of employment status. At a time in which jobs are quickly being eaten up by rapidly advancing technology, employment should not determine a person’s right to having their basic needs accounted for, the Berggruen Holdings founder and his coauthor, Nathan Gardels, argue in their book.

“What we are proposing is, as opposed to redistributing through taxes … why not give everyone a chance from the beginning? And to put it in concrete examples, if [going forward], if one creates a business, let’s say in California, as a compromise to potentially, you know, pay a different rate of taxes, let’s say lower, one would give a stake [of] the business to the state. So that the state, and therefore all citizens who are part of the state, would really become owners in the business in the future of, hopefully, something that is successful,” Berggruen tells the Truthdig editor in chief in the latest installment of “Scheer Intelligence.”

Scheer, however, challenges the billionaire with a potential blind spot in Berggruen’s plans: Can we trust elites, well-intentioned and otherwise, to save democracy when they played a huge role in pushing the world to the dire straits it finds itself in currently?

“It seems to me most of the progress we’ve made in society has come from below. You know, people demanding civil rights, demanding women’s rights, demanding a living wage as now happens,” Scheer says. “That, to my mind, is the key issue: Does progress come from enlightenment on above, when they feel their situation is at risk? Or does it come from, yes, a notion of democracy, of complaint from below, and a demand that something happen?”

“We need change. We need new ideas. We are very open, and actually, we love anyone’s ideas, as long as they’re truly new and fresh. And they can come from anyplace. And I agree, very often they will come from not only below, but from unexpected places,” Berggruen responds.

Listen to their full discussion, which spans everything from analysis of current trends in democracy to thoughts on how China could serve as a model for the West. You can also read a transcript of the interview below the media player and find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of “Scheer Intelligence,” where the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case, it’s Nicolas Berggruen. He was once known as the Wandering Billionaire, because he did a lot of his hedge fund and other investing business while living at hotels. He’s since become a concerned citizen and a leader of a think tank bearing his name. And he’s written a truly provocative and important book called Renovating Democracy: Governing in the Age of Globalization and Digital Capitalism. And it’s really about the need to profoundly alter our way of making decisions, because otherwise we are doomed. And so I guess I’ll leave it to you now to sort of give me, why this book, and what is the urgent message?

Nicolas Berggruen: Well, thank you, thank you for having me on your program. I’m honored and delighted. So, the book really covers, I would say, two main themes. One, the one you talked about, which is capitalism; and the other one, democracy. And what we are trying to think about are sort of two paradoxes. On one side, capitalism has conquered the world; it’s brought, frankly, billions of people out of poverty, so it’s been successful. And the question is, can it continue to be successful? Will it be rewarding for most people in the future? And rewarding not just from a material standpoint, but also from a moral, human, and dignity standpoint. And so these are serious challenges, but they’re not impossible to solve. Because with technology, with communications, with let’s call it a reasonable moral compass, we have the means, actually, I think, to address these issues. We need new thinking. And the question is, how do you take an old model which divided up the spoils in a certain way, and which created competition, which was healthy–but how do you make this competition fair? And what we are proposing is what we call pre-distribution, which is to give everyone something from the beginning, sort of a chance from the beginning, meaning obviously education, healthcare, the opportunities to have a future, the opportunities to have access to jobs and a dignified life. And the question is, how do you do this? And what society has evolved to is, some people start businesses, invest the capital, own these businesses, employ people, share some of the fruits of the investment with their employees, and ultimately with society through taxes. It’s been OK, but it’s becoming quite toxic–meaning the haves and the have-nots, not just in terms of money but also opportunity, are increasingly put in a position where they’re going to fight for those spoils, or fight for a position. And what we are proposing is to see if what is being created in terms of wealth, but also in terms of the sort of, the cultural value of what society produces. And this is, more and more will be, frankly, done by machines as opposed to people. How do you give this to everyone in a way that’s fair? And what we are proposing is, as opposed to redistributing through taxes, which is again, I would say, a very competitive and almost toxic environment, why not give everyone a chance from the beginning? And to put it in concrete examples, if going forward–you can’t go backwards, but going forward, if one creates a business, let’s say in California, as a compromise to potentially, you know, pay a different rate of taxes, let’s say lower, one would give a stake–which, that’s the important part, a stake of the business to the state. So that the state, and therefore all citizens who are part of the state, would really become owners in the business in the future of, hopefully, something that is successful. And there are always successes, and these successes are much bigger than the failures overall. So the successes become really quite valuable. So how do these successes get, if you want, come to the benefit of citizens as a whole? So why not give or contribute a share of new businesses to society as a whole, to the state as a whole, which would go into a large fund. That fund would obviously have value, and the cash flow from all these different businesses ultimately would accrue to citizens by contributing to the budget. And with modern technology, frankly blockchain technology, you can attribute to everyone a share of everything. So that everybody knows that they own part of something. They feel–and that’s very important–that they’re all in the same boat. So if a business is successful, that business is for the benefit of everyone; it’s not just for the benefit of the capital or shareholders or employees, or, frankly, the state as a recipient of taxes. It’s a more fundamental way to involve everyone, to have everybody be in the same boat from the beginning, as opposed to through redistribution.

RS: Yeah. And also in the book, Reinventing Democracy, you actually hold out–it’s interesting, the first time I thought of this idea was with John Kenneth Galbraith, a famous economist who was also our ambassador to India when he wrote a book called The Affluent Society. We’ve had it with Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who talked about a guaranteed annual income for everyone. And your idea in the book is really, separate the job–you know, the job may go; it may go because of artificial intelligence, it may go because of patterns of international trade. But the worker is entitled to the basic necessities of life. Would that be a fair statement?

NB: Yes. So–

RS: But let me just put a finer point on it. So in other–and some of this, I mean, is to my mind unquestionably a desirable thing to do. It’s actually what informs that cry for universal health protection, some kind of a living wage, basic safe communities, decent schools, and so forth. So that the wherewithal of life is not dependent upon having a specific job, and if the job disappears or if people go on to do other things, you know, they will be supported in what is needed for life. And I must say, we’re getting a lot of this kind of request from people like yourself who have been very successful–extremely successful in the economy. I remember interviewing Bill Gates about this once for Talk magazine, where he talked about how he was going to give away all of his money at some point. I think you’re a part of that, is it called a living trust, or–?

NB: Giving Pledge.

RS: Yeah. And the idea being that society requires some kind of floor that separates the basic needs or requirements of living, separate from whether your job is still needed. And that way you could have progress with artificial intelligence, robotics, and so forth. The missing link, it seems to me, is what will–there are some good folks out there. You know, Elon Musk, who you quote in your book; a lot of people. The question is, what pushes it over the finish line? Because it seems to me most of the reform that we’ve had in capitalist society, and in any society, has come from popular movements of resistance. People saying, “it’s not working,” and therefore they go on strike or they have a #MeToo movement or a Black Lives Matter movement, or so forth. It doesn’t generally come from the goodwill of affluent people. I mean, you mentioned in the book Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, for example–well, that basically came about because there was a movement of unemployed people and impoverished people in the Great Depression, and demanding, and veterans demanding pensions, and so forth. So what I find absent in the book is any discussion of the popular movements that will propel this change. And let me give you my other issue of concern: you lumped populism as sort of the enemy in this book, and direct democracy and so forth. And you associated that primarily with Donald Trump. But we also have the populism of somebody like Elizabeth Warren, or Bernie Sanders. And isn’t that sort of discontent from below required for public, for change?

NB: So, at the end, change is maybe the hardest thing, and no matter what. And you can see that even in democracies, change is very difficult. The country I was born in, France, elected a president on the basis that he would make some changes. As soon as he started making changes–this is Emmanuel Macron–you know, everything was stopped. And it’s been 20 Saturdays in a row that you’ve had protests, including violent protests, in Paris and all around the country. So change is very difficult. But you can, you know–I think the seeds of change are a little bit everywhere. In the discussion we just had about economic changes, changes in the way capitalism works, it’s already there. Discussions of universal basic income is everywhere. We are proposing universal basic capital, as opposed to universal basic income. Meaning, you know, a stake, or the opportunity to be a participant in society from the beginning, not just through a stipend, you know, over time. So if you want, it’s an evolution in some of the ideas that exist already. So the ideas, in some cases, exist already; but in truth, very often you need sort of people to run out of ideas. You almost need a, you need a crisis for ideas to be emerging. It’s never good to go through a crisis, because that means also suffering. But change is difficult; change very often includes suffering. And I would say what you call populism is really a symptom of discontent in general. In this case, on both sides, right and left. And is it unhealthy? It’s healthy that it exists; the expression of it could be unhealthy. To take an extreme example, look at what happened before World War II, which led to World War II. So if it’s extreme, it can become very unhealthy. And very often it empowers people who, let’s say, are extreme and will shut out the other side for a period of time. I don’t think that’s healthy. So the debate is very healthy; that’s part of a democracy. The expression of it can become unhealthy, and that’s what we don’t want. Because in a democracy, you have the potential of the tyranny of the majority in a way that people will accept as legitimate, because it’s done through elections. But elections is not everything; you need more than that, and that’s part of, I think, what made our democracy successful, is that it’s an ecosystem that involves citizens, but also involves government as a service organization. People who are elected and who, when they serve, serve everyone, not just their party. And what happens in periods of populism is that the people who get elected get elected because they scream maybe louder, or they have a message that is very emotional, maybe sometimes very legitimate. But they get elected, and they represent their voters as opposed to representing all citizens. And at the end of the day, democracies work because they work for the most people, not just for the people who’ve gotten the power.

RS: There’s an important point that you’re raising. And the book does. I think there is technological changing; has to be managed, it can destroy a lot of lives. The question is, who do we trust to bring about this change? And there is a message in your book that has a critique of a notion of democracy. Your book goes so far as to say the Founders didn’t intend for us to be a democracy, they were afraid of democracy. And you have some quotes that are real, their concern about the turning into a mob-run country, and so forth. However, I think the problems that we’ve experienced–and let me be very precise about this–have come not from the mob, and not even from the Donald Trumps. You do say that in your book; he didn’t create all these problems, nor did Bernie Sanders for that matter. An elite that was very responsible, very logical, that claimed–very well-mannered. And you mentioned these financial transactions–they were a scam. They testified, they knew finally when they were hauled before Congressional committees, they didn’t even understand what these collateralized debt obligations were. They were just grabbing a lot of different things and putting them in a package, and it looked good and you sold it, and then you gave these liars’ loans and you deceived people, and you told them it was wonderful. And then the next thing you knew, they lost all their life savings and so forth. This was a major tragedy, and you know, people lost a lot of their life savings and it set them back, particularly minorities. So this was mischief on a grand level. And because of that mischief–and something that’s not discussed in your book, the resources we waste on needless wars, the lying about going into war with Iraq and so forth–came from good people that claimed they were concerned people. So you have this enormous mischief-making by elites, you know. Henry Kissinger is another person you cite in your book as a source, and these are all these very respectable people. Some of them have played a very good role, by the way; Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize winner, he was a very good critic and says all the things that I’ve just said about the banking scandal. But the main issue I have with the book–and I do recommend that people read this book, because I think it’s an unnerving and all-too-accurate view of what’s happening to technology, its effect on the job market, what’s happening with globalization. And by the way, a very, I think, sophisticated view of China that we don’t normally get. So I want to be positive about this book. I think it’s well worth reading, well worth having a discussion about. Where I have a problem with it is, it attributes no effective role to popular opposition and concern. And yet it seems to me most of the progress we’ve made in society has come from below. You know, people demanding civil rights, demanding women’s rights, demanding a living wage as now happens. Here in Los Angeles County and city we have actually a living wage coming into being. And so this idea that we can count on the elite to do the right thing–and that was, you know, Roosevelt hoped they would, but they didn’t. And so he went with what people from below were demanding, you know? That, to my mind, is the key issue: Does progress come from enlightenment on above, when they feel their situation is at risk? Or does it come from, yes, a notion of democracy, of complaint from below, and a demand that something happen? And in the French situation, which you probably, I assume you know a lot more than I do, there seems to be genuine discontent fueling opposition to the person, to Macron.

NB: No doubt. And the issue is that at the end of the day, no matter where you are, which society, if you’re going to go forward you need leadership. The real question is, which leadership, and who, and when? And what you’re saying, what you’re implying indirectly, is it’s very possible that the thinking that has, let’s say, shepherded over the last hundred years, maybe the thinking has gotten tired. The so-called elites that have been sort of leading us have been misguided. Maybe they got tired.

RS: Corrupted.

NB: Corrupted. Any system, after a while, no matter how successful, become corrupt inherently. And you need renewal. In this case, we’ve progressed so much, but also so fast, that you need potentially not only new ideas, but you need a renewal in terms of thinking, but also in terms of people. Ultimately, you’ll get new leadership–in essence, new elites of some kind. The question is, who are those people? You definitely need new people, by definition. You need new ideas, I think, more than ever. And you have to enable those ideas. Are they going to come from the people who have led us up to now? Probably not. Part of what we do, Nathan, who you mentioned, and I have created an institute that hopefully, let’s say, enables, helps new thinking and new ideas. I think it’s absolutely necessary, and the people who are going to bring about some of these ideas and lead us into the future will have to be new people. So, yes, you need a renewal in different people. Does it mean that you have to give up on the idea that you need a system that works for everyone, and that isn’t just giving a voice to whoever speaks the loudest? I think the system of trying to build a long-term future for most people is still the right idea. The question is, how do we get there, and–