Chris Hedges's Blog, page 171

August 23, 2019

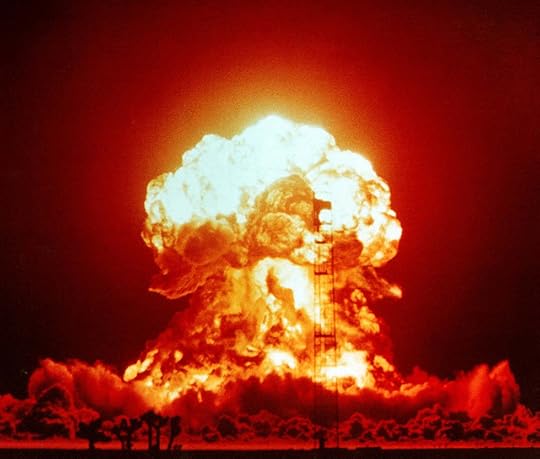

Putin Orders Russia to Respond After U.S. Missile Test

MOSCOW — President Vladimir Putin ordered the Russian military on Friday to work out a quid pro quo response after the test of a new U.S. missile banned under a now-defunct arms treaty.

In Sunday’s test, a modified ground-launched version of a U.S. Navy Tomahawk cruise missile accurately struck its target more than 500 kilometers (310 miles) away. The test came after Moscow and Washington withdrew from the 1987 Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

Speaking at a meeting of his Security Council, Putin charged that the U.S. waged a “propaganda campaign” alleging Russian breaches of the pact to “untie its hands to deploy the previously banned missiles in different parts of the world.”

Related Articles

Donald Trump's Nuclear Doctrine Threatens Human Life on Earth

by

One Minute to Midnight

by Scott Ritter

He ordered the Defense Ministry and other agencies to “take comprehensive measures to prepare a symmetrical answer.”

The U.S. said it withdrew from the treaty because of Russian violations, a claim that Moscow has denied.

In an interview this week with Fox News, Defense Secretary Mark Esper asserted that the Russian cruise missiles Washington has long claimed were a violation of the now-defunct Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces, or INF, treaty, might be armed with nuclear warheads.

“Right now Russia has possibly nuclear-tipped cruise – INF-range cruise missiles facing toward Europe, and that, that’s not a good thing,” Esper said.

The Russian leader noted that Sunday’s test was performed from a launcher similar to those deployed at a U.S. missile defense site in Romania. He argued that the Romanian facility and a prospective similar site in Poland could also be loaded with missiles intended to hit ground targets instead of interceptors.

Putin has previously pledged that Russia wouldn’t deploy the missiles previously banned by the INF Treaty to any area before the U.S. does that first, but he noted Friday that the use of the universal launcher means that a covert deployment is possible.

“How would we know what they will deploy in Romania and Poland — missile defense systems or strike missile systems with a significant range?” Putin said.

A Pentagon spokesman, Lt. Col. Robert Carver, disputed Putin’s assertion that the land-based U.S. missile defense system in Romania could be used to launch ground-attack missiles. He said the U.S. launch system in Romania, known as Aegis Ashore, “does not have the capability to fire offensive weapons of any kind,” including a cruise missile like the Tomahawk variant used in the Aug. 18 U.S. test.

“It can only launch the SM-3 interceptor, which does not carry an explosive warhead,” Carver said, adding that it would take “industrial-level construction to reconfigure it to fire offensive weapons. That reconfiguration would entail major equipment installation and software changes.”

Russia long has charged that the U.S. launchers loaded with missile defense interceptors could be used for firing surface-to-surface missiles. Putin said that Sunday’s test has proven that the U.S. denials have been false.

“It’s indisputable now,” the Russian leader said.

He added the missile test that came just 16 days after the INF treaty’s termination has shown that the U.S. long had started work on the new systems banned by the treaty.

While Putin hasn’t spelled out possible retaliatory measures, some Moscow-based military experts theorized that Russia could adapt the sea-launched Kalibr cruise missiles for use from ground launchers.

The Interfax news agency quoted a retired Russian general, Vladimir Bogatyryov, as saying that Moscow could put such missiles in Cuba or Venezuela if the U.S. deploys new missiles near Russian borders.

Putin said Russia will continue working on new weapons in response to the U.S. moves, but will keep a tight lid on spending.

“We will not be drawn into a costly arms race that would be disastrous for our economy,” Putin said, adding that Russia ranks seventh in military spending after the U.S., China, Saudi Arabia, Britain, France and Japan.

He added Russia remains open to an “equal and constructive dialogue with the U.S. to rebuild mutual trust and strengthen international security.”

___

Robert Burns in Washington contributed to this report.

Trump Never Had a Grand Strategy for China

President Trump has delayed the new tariffs he threatened to impose on Chinese imports in the early fall, and exempted some other Chinese imports altogether. The de-escalation of the Sino-U.S. trade war is especially welcome, given the markets’ renewed concerns about impending recession. Also striking was the president’s tacit acknowledgment that the tariffs threatened to harm the American consumer (which is probably the closest approximation we’ll ever get to an actual admission of error on his part).

The truth is that we’ve had more than enough time under this “stable genius” to realize that there is no long-term strategic coherence to his trade policies, let alone signs of any “art of the deal.” Rather, the Trump presidency has been characterized by arbitrary goals and capricious tariff announcements that appear to be crafted with a view to securing plaudits on “Fox and Friends.”

Unfortunately, “moderate” Democrats have not been much better on trade. Figures like former Vice President Biden continue to dismiss the competitive threat posed by China’s trade practices, and harken back to supposedly halcyon days of lobbyist-written “free trade” agreements that largely funneled income gains to the top tier. Millions of casualties from hyper-globalized trade have emerged in places like Biden’s own Scranton, Pennsylvania, where the ravages of NAFTA and other trade agreements were ignored by the political class and made proto-fascist politics more appealing.

Related Articles

U.S.-China Talks Are About Much More Than Trade

by

America's Long War of Attrition With China Is Just Beginning

by

Many rationales have been deployed by the president to explain his ongoing embrace of the tariff weapon. None, however, fully stack up.

Trump has been compared to previous “tariff men,” such as former Republican President William McKinley, who explicitly campaigned in the 1896 election on a protectionist platform. Like McKinley, Trump has expressed his support for tariffs in nationalistic terms. He sees them less as a tax on the domestic consumer, more a key tool to make American business great again, as well as claiming that tariffs represent a valuable source of government revenue. This appeal to historical precedent is another worn-out lie to justify a stupid policy. As the Washington Post points out, “tariffs haven’t been a major source of U.S. revenue in 100 years,” and Trump himself explicitly exempted certain products from tariff increases until December 15 because of his concern about the costs that they would impose on U.S. consumers as we head into the Christmas shopping season. The revenue generation argument is particularly laughable, coming from a man whose entire working life, both in the public and private sector, has been marked by a complete indifference to debt buildup, let alone fretting about paying it back. It’s a true perversion of history to connect Trump’s tariff legacy in any way to that of McKinley.

Conversely, is the goal to disrupt supply chains and re-domicile them back to the U.S.? If so, then where is his administration’s support for R&D, education, and other industrial policies that could enhance national development, thereby making the U.S. a more attractive place to reclaim high valued-added supply chains? For example, Apple CEO Tim Cook, justifying his company’s decision to manufacture iPhones in China, pointed to the abundance of skilled manufacturing labor in that country, along with Beijing’s decision to emphasize vocational training at a time when the idea has been virtually abandoned in the U.S. This a problem that predates Trump, but the president has done nothing to rectify the deficiency. In fact, his secretary of education is viscerally hostile to the very concept of publicly funded education (of any kind), as well as being a shill for charter schools and privatized voucher programs (in which her family has vested economic interests).

As Robert Atkinson and Michael Lind argue in a recent American Affairs article, “Trump proudly touts his tax cutting and deregulation prowess, while his budgets slash support for key national investments in building blocks like research and development, manufacturing support programs, infrastructure, and education and training.” This comes at a time when America’s infrastructure is already one of the worst in the developed world.

Does the president just want to offer American businesses a temporary respite from hostile Chinese mercantilism via tariffs? If so, his tariffs have hitherto been singularly unsuccessful in stopping Beijing’s mercantilist efforts to try to maximize global market share by dumping below cost until its foreign rivals are driven out of their home markets. Furthermore, as recent events have illustrated, there is little Trump can do if and when China devalues its currency to offset the impact of the increased tariff charges he has introduced (or threatened to revive).

Is Trump concerned about national security? U.S. lawmakers and intelligence officials have claimed, for example, that both Huawei and ZTE could be exploited by the Chinese government for espionage and sanctions-busting respectively, presenting a potentially grave national security risk. Yet the president has often appeared prepared to ignore these concerns, in the interests of using these companies as trade bargaining chips, designed to secure some additional purchases of American soybeans or, more generally, as part of a bigger trade deal.

To be sure, some of the president’s criticism of the historic status quo in trade is valid, as the post-industrial wastelands strewn across the country illustrate. China’s entry into the World Trade Organization had a profoundly negative impact on U.S. manufacturing jobs. We therefore need a national development strategy that breaks with many of the shibboleths of the so-called “Washington Consensus.” As I’ve written before, the policy goal should be to “change the labor share of the production equation, so that production vastly increases general welfare and living standards for the largest possible majority of people. By conducting policy with a view toward favoring labor over capital, the aim is to produce a larger economy, and more stable (albeit restrained) profits.”

Historically, America has not always approached things simplistically through the lens of the free market/market fundamentalist paradigm. After World War II, figures such as A.A. Berle and John Kenneth Galbraith advocated global cartels in commodities to raise incomes in developing countries, and thereby become additional sources of demand for American manufacturers. They also looked benignly on transnational industrial cartels at home in the U.S. Berle, Galbraith and others were advocates for local content requirements so as to sustain America’s industrial ecosystem. And they favored buffer stocks to reduce global booms and busts.

If Elizabeth Warren and her team better appreciated this history (and Warren is the leading Democrat offering a significant reassessment on American trade policy today), they would see that there is a rich counter-tradition that goes beyond a mindless resort to tariffs or simply breaking up successful multinational companies that are among America’s most profitable. Warren and others might reassess the virtues of selective cartelization and cooperation. She and other Democratic presidential candidates could give consideration to constructing a size-neutral regulatory framework to ensure that such companies operate in the interest of national economic strategy consistent with military security and widespread prosperity in order to obtain maximum benefits for American workers and regions. As venture capitalist Peter Thiel has recently argued, it is perverse for Google to refuse to do business with the U.S. Pentagon, while conducting artificial intelligence work in China, which uses AI to sustain its own authoritarianism and mass surveillance.

Embracing national champions does not mean supporting inefficient state white elephants that dole out political favors. There is a large body of research from Joseph Schumpeter onward to suggest that large enterprises are usually the leading avatars of innovation and productivity. Moreover, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can also reap benefits of scale by pooling R&D, exporting marketing boards, etc., as alternatives to mega-mergers. Government can also play a significant role here, at a minimum by upping research and development expenditures (at its peak during the 1960s, federal government R&D was more than 2 percent of GDP but is now less than half of that).

Likewise, Big Three tripartism—a form of economic collaboration amongst businesses, trade unions, and national governments—should be further embraced to enhance economic prosperity and cope with the challenges of state-sponsored Chinese mercantilism. Both market fundamentalists and pro-business oligarchs like Trump may dismiss collective bargaining as another kind of labor cartel (the Clayton Antitrust Act, however, exempted unions from antitrust). One can be both pro-business and pro-labor (i.e., pro-“national developmentalism”), as Warren appears to be. There is nothing inherently contradictory in terms of favoring limited pooling in employer federations that can bargain with unions, R&D consortiums, export consortiums, etc., while allowing these entities to retain their identity even as they compete with one other. Policies can also be designed to compensate for the higher cost of labor in SMEs via Fraunhofer industrial extension services that enable small producers to compete on the basis of technology, not low wages.

Enough with the “tariff tantrums.” Or the silly idea that a modern economy can forfeit manufacturing to its rivals and specialize in finance, entertainment, tourism, and natural resource industries like farming, while making empty pledges about retraining and relocation to help the “losers” of global integration (promises seldom kept). We have a domestic crisis, and must do better than simply retreat to the delusions of neoliberalism or mindless protectionism if the American people are to come out as winners in a viable future trade framework with Beijing and the rest of the world.

This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Marshall Auerback is a market analyst and commentator.

Stevie Ray Vaughan: Playing as If His Life Depended on It

“Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan”

A book by Alan Paul and Andy Aledort

Almost 30 years after his untimely death, guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan’s virtuosity is widely acknowledged, but his life and career remain difficult to place. For a Texas bluesman, Vaughan seemed too influenced by rock guitarists, especially Jimi Hendrix. And though his solo on David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” helped make that song a hit, Vaughan purposefully chose the blues, whose future was uncertain, over all other idioms. How exactly did Vaughan become the unique artist that he was? Alan Paul and Andy Aledort’s “Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan” answers that question with uncommon clarity and authority. Made up largely of direct quotations from those who accompanied, managed, or produced him, Vaughan’s story unfolds in surprising ways.

The temptation in such biographies is to make the subject’s success seem inevitable. Turning points are identified and cataloged, and though the story usually includes challenges and setbacks, it arcs inexorably toward greatness. But the interviews here temper that sort of mythmaking. We learn firsthand about the early gigs, shifting lineups, drug and alcohol abuse, and the vagaries of making it in the music business. And though “Texas Flood” reveals a series of transformative moments in Vaughan’s life, they are so contingent and inapposite that his success never seems predestined.

Vaughan was born in 1954 and raised in a scratchy part of Dallas. As a teenager, he dropped out of school, moved to Austin, and was known as Jimmie Vaughan’s talented younger brother. His first big opportunity came in 1976, when the owner of an Austin club begged the curmudgeonly Albert King to let Vaughan play with him. As Jimmie Vaughan said, “Nobody would ask Albert King to sit in unless you were dumb or something.” One eyewitness recalled, “Of course, Stevie just burned, like he always did. There was little Stevie up there with Big Albert killing it, and it really tickled Albert—and all of us. He started playing Albert King licks and doing it really good, and Albert looks down and shakes his head.” Another witness noted, “It really felt like a milestone for Stevie.”

Six years later, however, Vaughan was still grinding it out in local clubs. His manager sent a tape to Mick Jagger, and Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler heard Vaughan for the first time at a Texas club. It was, Wexler said, “almost an out-of-body experience.” He recommended Vaughan to the organizer of the Montreux Jazz Festival. “You gotta book this musician,” Wexler said. “I have no tapes, no videos, no nothing. Just book him.”

In April of that year, Vaughan auditioned for Rolling Stones Records by playing a private party in New York City. “As soon as Stevie started playing,” one spectator observed, “Ron Wood grabbed a chair, straddling it right in front of Stevie. He stared at Steve the entire time, hypnotized.” The label didn’t sign Vaughan because Jagger said blues albums didn’t sell well. But as Vaughan’s bandmate noted, “We were playing Skip Willy’s for four drunks, and all of a sudden Mick Jagger wanted us to play for him in New York. … This huge momentum seemed to be building.” Vaughan was impressed by another aspect of the trip. “I’ve never seen so much cocaine in all my life,” he told a friend in Austin. “I think Ron Wood had cocaine in every one of his pockets. And it was good shit—my heart was pounding!”

Vaughan’s set in Montreux went badly, but David Bowie asked to meet him in a bar and invited him to play on his next album. The next night, Vaughan was playing the same bar when Jackson Browne’s bass player walked in. He immediately called his bandmates and exhorted them to come. “We jammed until 7:00 a.m.,” Vaughan’s bandmate recalled. “When we were done, Jackson said that he had a studio in LA and we were welcome to come record tracks free of charge anytime.”

Both invitations were significant. Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” alerted fans and industry insiders to Vaughan’s talent, and a session at Browne’s studio produced “Texas Flood,” Vaughan’s first album. One admirer was Huey Lewis, who ran into Vaughan’s bandmate outside a hotel elevator, and later asked his manager to book Vaughan for his next tour. “It was all sold-out arenas, and that’s when things started taking off,” said the bandmate. Another observer likened that tour to Jimi Hendrix opening for the Monkees.

Paul and Aledort leave no doubt about Vaughan’s skill, compiling accolades from Gregg Allman, Eric Clapton, Robert Cray, Billy Gibbons, Buddy Guy, and other accomplished guitarists. The interviews also reveal the physical toll Vaughan’s style exacted on him. “He paid a price for being committed as he was to the kind of string bending he was known for,” said one insider. “He often had massive holes, like a quarter-inch deep, in his fingertips. Before shows, he would fill the holes with baking soda and put super glue over it.” After grafting a piece of skin on top of the hole, Vaughan would then “file it down smooth so it wouldn’t catch on the strings. He was very ingenious and inventive.”

“Texas Flood” is at its best on the subject of Vaughan’s chaotic personal life. He never kept a home, was careless with money, and abused drugs and alcohol for so long that he thought his music required it. That abuse also dominated his troubled marriage. At age 31, he was walking with a cane and blowing his solos, playing in the wrong key or in perfect time on the wrong beat. He later compared those performances to playing the guitar with boxing gloves. In 1986, he hit rock bottom in Germany, vomiting blood in his hotel room.

Everyone saw that—or something worse—coming. The real surprise was Vaughan’s later commitment to sobriety. “It didn’t occur to me that Stevie would really go clean,” said his brother Jimmie, who by that time was thriving with The Fabulous Thunderbirds. “I figured that he’d do his thirty days [in rehab] to get everyone off his back, then go back to it. But he was serious and dedicated, and he showed the way for me and a lot of other people.” Bonnie Raitt was struck by his personal and musical transformation:

He had a furnace in his heart and was the epitome of all that is dark and sexy, brooding and compassionate. The most extreme emotions of the blues and of life were in every breath he took. And to find out that he could maintain that while sober was just a revelation. If anything, he was covering more emotions. He was playing as if his life depended on it, and it did.

Vaughan’s bandmates also renounced drugs and alcohol, and the years that followed were remarkably happy and productive. Vaughan filed for divorce in 1987 and enjoyed a healthier relationship with his new girlfriend. Two years later, he released “In Step,” which won a Grammy. He also toured with The Fabulous Thunderbirds and reunited with his brother on “Family Style,” which appeared in 1990. But that idyll was destroyed when Vaughan perished in a helicopter crash after a performance in Alpine Valley, Wisconsin. Stevie Wonder, Dr. John, Bonnie Raitt, and Jackson Browne sang at his funeral.

The authors, both senior editors at Guitar World magazine, have covered similar ground before: Paul’s previous book, for example, documented the life and times of the Allman Brothers. But the authors give the last words to Jimmie Vaughan and Tommy Shannon, Stevie’s bandmate. “When Stevie played,” his brother writes in the epilogue, “his guitar talked and told his story. If you listen, you can hear it.” “Texas Flood” also tells that story—and captures the purity, simplicity, and expressive power of Vaughan’s music and message.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg Treated for Tumor on Pancreas

WASHINGTON — Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has completed radiation therapy for a cancerous tumor on her pancreas and there is no evidence of the disease remaining, the Supreme Court said Friday.

The court said in a statement that a biopsy performed July 31 confirmed a localized malignant tumor. Ginsburg, 86, underwent a three-week course of radiation therapy and as part of her treatment had a bile duct stent placed, it said. The court said Ginsburg “tolerated treatment well” and does not need any additional treatment but will continue to have periodic blood tests and scans.

The tumor was “treated definitively and there is no evidence of disease elsewhere in the body,” the court said.

Related Articles

Ginsburg’s Ribs and the Future of SCOTUS

by Bill Blum

Ginsburg Warns of More 5-4 Supreme Court Decisions Ahead

by

The court said Ginsburg canceled an annual summer visit to Santa Fe but otherwise has maintained an active schedule during treatment.

Ginsburg underwent lung cancer surgery in December and has had two previous bouts with cancer. She had colorectal cancer in 1999 and pancreatic cancer in 2009. While recovering from surgery she missed arguments at the court in January, her first illness-related absence in more than 25 years as a justice.

The Latest Victim in the Crucifixion of Julian Assange

The case of Ola Bini, a Swedish data privacy activist and associate of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, has been shrouded in mystery since his arrest in Quito, Ecuador, on April 11. He was detained on the same day Assange was forcibly removed from the Ecuadorian Embassy in the United Kingdom, inevitably raising questions about whether Bini was being held because of his connection with Assange and whether the United States was involved in the case in some form.

Bini, who initially wasn’t charged with a crime, was accused of being involved in a leak of documents that revealed that Ecuador’s right-wing president, Lenin Moreno, had several offshore bank accounts. Bini was released after two months in an Ecuadorian prison under terrible conditions but is still fighting to maintain his freedom. He was eventually charged by Ecuadorian authorities with “alleged participation in the crime of assault on the integrity of computer systems and attempts to destabilize the country,” though the evidence to support the accusations is dubious at best.

Speaking with Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer, Danny O’Brien discusses why Bini’s case is so important to follow, despite a general lack of media interest in his arrest. O’Brien, director of strategy at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, went to Ecuador to visit Bini on behalf of the EFF in order to learn more about the case and advocate for the Swedish activist’s rights.

Related Articles

First Julian Assange, Then Us

by Chris Hedges

18 Ways Julian Assange Changed the World

by Lee Camp

“Journalists, lawyers, human rights lawyers, human rights defenders, sort of viewed broadly, are often the canaries in the coal mines in authoritarian or veering-authoritarian regimes,” O’Brien tells Scheer in the latest installment of “Scheer Intelligence.” “I think many governments recognize that if you can either … silence, or just intimidate and chill, the key journalists or the prominent public defenders, then you have a huge sort of multiplier leverage effect on opposition groups, or groups fighting for justice in those countries.

“In the last few years,” O’Brien continues, “I think that governments around the world have recognized that technologists also fall into this category, or particular kinds of technologists.”

Scheer, whose most recent book “They Know Everything About You” is about mass data collection, highlights the threat activists like Bini pose to the powers that be at a time when big data translates to a mechanism for widespread control.

“You call him a world leader in trying to build safe places where people can communicate without being subject to government surveillance,” Scheer tells O’Brien. “And even though some people have a kinder view of the U.S. government, after all, we’re talking about a wide world that has to survive in even more overtly controlling environments, and explicitly totalitarian and authoritarian societies.”

Through his work at the EFF, an organization that has members from all parts of the political spectrum and advocates for free speech and privacy in the digital age, O’Brien has come to a harrowing conclusion that lies at the core of Bini’s case: Governments around the world are “the most clear and present threat to people’s privacy and security online.”

Listen to the Scheer and O’Brien’s full discussion as they discuss the details of Bini’s case and the origins and importance of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. You can also read a transcript of the interview below the media player and find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

—Introduction by Natasha Hakimi Zapata

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, and–where I have to point out, in due modesty, the intelligence comes from my guests. And in this case it’s Danny O’Brien of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. If you haven’t heard of EFF, you’ve missed out on the most important organization concerned with the freedom of the individual, privacy, and related issues in the world of the internet. Danny, welcome. And how long has EFF been in business, and how long have you been one of the leaders there? Your title has changed, I noticed.

Danny O’Brien: Yeah, so the Electronic Frontier Foundation has been around since 1990. So pre the web, but perhaps not pre the internet. And I’ve been there since 2005, and I’m director of strategy now, but I used to concentrate on the global side of the internet. A lot of what EFF does, and continues to do, is domestic in the United States. We sue the NSA for its mass surveillance of Americans, and we also sort of deal with the big tech companies in Silicon Valley, too. But of course the internet’s got international since 1990, and increasingly a lot of the edge cases, and maybe the indications of where things are going to go, don’t come from the cutting edge of American technology, they come from around the world.

RS: OK, but before we get lost in the weeds here of the technology, let me just explain my respect for EFF and the reason I wanted to interview you in this particular case involving Ola Bini–I hope I’m pronouncing it correctly–a renowned Swedish programmer who’s facing horrendous computer crime charges in Ecuador, the country that under a different regime supported or allowed Julian Assange to stay in their embassy in London, and then the government changed, and Julian Assange is now in jail. And what I want to really get at is the connection between the two cases. And just so there’s a little background, I haven’t seen much publicity to your trip or to this case. And one of the things I love about the Electronic Frontier Foundation is I don’t know whether you guys individually are conservative or liberal, you know, or libertarian or what have you, but I can count on you, speaking as a journalist, to really call it as honestly as you can in any of these situations. So why don’t you tell me the significance of this case, and really, why isn’t it getting more of a response?

DO: That’s a really good question. I can talk a little bit about the significance of the case, both kind of EFF as an organization and also for its wider implications. So EFF started–and I think this is why we always seem to be a bit hard to place on the political channel–as a combination of people from all over the political spectrum who all knew one thing, which was that the rise of digital technology, what we used to call the digital revolution, was going to transform people’s rights, whether for good or for ill. So our founders had John Perry Barlow, who was one of the lyricists of the Grateful Dead. We have Mitch Kapor, who was, still is, a businessman; he started Lotus 1-2-3, [which] the ancients among us will remember as the first real popular spreadsheet. [And John] Gilmore, who had a strong place both in programming and kind of the libertarian space. So our politics are all over. But one of the areas that we spent a lot of time in the early years was just trying to explain to people that–this was in the very end of the eighties–that these technologists who were coming along, especially teenage technologists with strangely colored hair, were not necessarily the horsemen of the apocalypse, right. That they had these skills, and there was a real potential here for them to create things that would be useful and powerful and good for open societies. So we spent a bunch of time in the courts explaining it to judges, sometimes actually defending hackers and technologists. So we have a long tradition of doing that. I think what’s interesting in the sort of era–the post-WikiLeaks era, you might describe it–is that that sort of model or fiction of what technologists of that kind are like has gone from being these are sort of scary teenagers, to these are people who could, are really going to disrupt society. Whether they’re the head of Facebook–you know, Mark Zuckerberg certainly describes himself as a hacker. The address, if you need to send snail mail to Facebook, is 1 Hacker Way. You have folks like Assange that definitely came from that hacker technologist community. And then you have people like Ola who are like thousands of people around the world, who really are keeping the privacy protective parts of the internet, and the stuff that keeps you safe from governments, corporations, and cybercriminals–they’re like another camp entirely. But they’re all from this community of people who understand the technology. And their politics are very varied, their impact is very varied, and their motivations are very varied. One of the challenges we’ve always had is that people look at the worst in that community, and kind of apply it to everyone else. And that’s sort of understandable if you’re trying to deal with a scary, new entrant into the power dynamics of modern society. But it can mean that you can throw out not only the good with the bad, but the people who might be solutions to the problems that the other actors are creating.

RS: And that’s one of the things that Ola Bini was a leader in. You call him a world leader in trying to build safe places where people can communicate without being subject to government surveillances. And even though people, some people, have a kinder view of the U.S. government, after all, we’re talking about a wide world that has to survive in even more overtly controlling environments, and explicitly totalitarian and authoritarian societies. And he has been one of the people–I gather he’s been a consultant to the European Union; he’s worked on your very successful sites to keep people [in] this kind of protection. So why don’t you just tell us about, you know, who this guy is, and how he connected somehow with Julian Assange. And then let me just give the punchline. You know, I only learned about this case because three of you from the EFF bothered to go down to Ecuador and find out what was going on. I know the justice minister there didn’t meet with you; you met with other people, and his defense team. And then you wrote a report when you came back. And for people who don’t get the EFF report, I would highly recommend it; we’ll cite it at the end. But you were really doing yeoman work here. And again, I beg the question: Why isn’t this of greater concern?

DO: So I think there’s two parts to this. One is sort of unpacking who Ola is, and maybe we can get to that in a moment. I think that the more pertinent question, certainly for me right now, is you know, why is there not more attention on cases like this. And I think that–I don’t think it’s new. I think that there’s a model for what we see here, which is–I used to work for the Committee to Protect Journalists, which is a great organization–

RS: I was once on the board, very early in the day, I myself, yeah. When I worked at the L.A. Times, yes.

DO: Right, right. And, well, you’ll know that they do really good and similar work for journalists around the world. Because I feel like journalists, lawyers, human rights lawyers, human rights defenders, sort of viewed broadly, are often the canaries in the coal mines in authoritarian or veering-authoritarian regimes. And that if you–I think many governments recognize that if you can either tug it, or silence, or just intimidate and chill, the key journalists or the prominent public defenders, then you have a huge sort of multiplier leverage effect on opposition groups, or groups fighting for justice in those countries. What’s happened in the last few years is I think that governments around the world have recognized that technologists also fall into this category, or particular kinds of technologists. Actually, I’m sort of dealing with this right now in China; China has been building up to intimidate and scare its own community of technologists who have been primarily involved in creating tools to bypass the Great Firewall of China. Now, of course, it’s coming a little bit more to a head, to the technologists who are protecting the privacy of the Hong Kong protesters. So we see this sort of move, but I think right now we’re sort of in an era where the world–and I think this is, I’ve already talked about the post-WikiLeaks world; I think this is the post- or mid-Facebook era–where people have gone from being, you know, actually quite engaged and excited by the promises of digital technology, to really quite cautious and intimidated by them. And so when somebody comes along who has these skills, I think it’s pretty easy for a government to whip up a moral panic about them. And that’s what happened with Ola in Ecuador. He was arrested shortly after a press conference that the current minister of the interior held–hours, I think, after the U.K. police were allowed into the Ecuadorian embassy, and Julian Assange was taken out pretty forcefully. So hours after that, the interior minister in Ecuador held a press conference and said, look, we know that there are members of WikiLeaks within Ecuador, and Russian hackers who are planning to attack and bring down the country’s systems. We’re going to arrest them. And then within hours, Ola–who is Swedish, but lives in Ecuador–was picked up and thrown in jail.

RS: And what is the connection between Ola and Julian Assange?

DO: So Ola Bini has–or the government has accused him of meeting with Julian Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy, I believe 12 to 13 times. They will know [Laughs], because they’ll see, they have the visitor’s book in the Ecuadorian embassy. Of course, apart from the fact that who you associate with isn’t actually, or shouldn’t be a crime that you can be arrested and thrown in jail for, it’s also the case–and this is after I spent some time trying to understand better who Ola Bini actually was, partly in talking to him, but mostly in talking to other technologists around the world–ah, Ola talks to a lot of people. And also, during that period of Julian Assange’s sort of exile in the embassy, a lot of people went and saw that man. From, again, all across the political spectrum, and with many different interests. So that’s the evidence that the Ecuadorian government has so far to claim–

RS: Including Google’s Eric Schmidt, right?

DO: That’s right. I’d forgotten about that, but yeah, ah–

RS: Yeah, he was in there, meeting with him and so forth, yeah.

DO: Right, and of course you’ve got to remember that, like, the arc of Julian Assange’s sort of rise and, you know, potentially fall, at least amongst the U.S. left, has meant that he has definitely ended up meeting with or associating with a huge range of different people. You know, I think he went from a point where he was a cause célèbre to now, where I think a lot of people accuse him, or certainly feel that he is implicated in the election of President Trump.

RS: Yeah, and we’re–we’re going to get to that. I already did an interview with the UN rapporteur on torture, and you’re familiar with his statement about how Assange was treated. I think it’s critical to observe here–and it is a real failure of a part of the left, or liberals, or people who care about individual freedom, whether they’re left or right–that somehow the whistleblower has gone from being an admired figure to being a scorned person. And there’s some irony in this. I’ve done some of these podcasts with Daniel Ellsberg, who I actually, you know, covered as a journalist during the Pentagon Papers trial. And now Ellsberg is remembered nostalgically as a heroic whistleblower, and somehow Julian Assange is a retrograde. And Ellsberg is very quick to point out that actually Julian Assange, in the case of the Pentagon Papers, would be in the position of the New York Times and the Washington Post as publishers. And that he, Daniel Ellsberg, was actually the person who had worked for the U.S. government, had been given these documents as an employee of the RAND Corporation, which then had a contract with the U.S. government. And so he was actually in a much more vulnerable position as a whistleblower. But I do want to stop on that for a minute. Because when you just said, oh, the guy visited Julian Assange 11 times or something in the embassy–slam dunk, guilty as charged. How did we get to this place where whistleblowers–after all, Julian Assange, whatever you think of him, revealed serious crimes on the part of the U.S. government. Deliberate shooting and targeting of civilians, journalists and what have you, and others. And yet no one’s talking about the crimes that were revealed; they’re talking about Julian Assange as if he’s the criminal.

DO: Right. And I think some of this is down to the fluidity of roles that we have now. That somebody can go from being, you know, just an ordinary person to becoming a whistleblower. You know, it’s really possible for anyone who has access to corporate or government data now to be able to not only extract that, or know about it, but also broadcast it to the world, right? You could tweet a zip file, right; you could do whatever you want. And also, what does it mean for someone to be a publisher? This is definitely the thing that we’re, the EFF’s most concerned about in the U.S. side of the Assange case. Which is that the prosecutors in that case seem very keen to charge Assange with both violations of the Espionage Act, where there has been a sort of understanding that publishers would not be prosecuted under that very broad, World War I statute. And also the CFAA, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which is a similarly broad law, but on the kind of technological side of things. So there we have a situation where Assange, as I said, sort of comes from this cybersecurity, technologist community. He was a familiar face in that community before he went off and became the face of WikiLeaks. But he had the skills and the ability to transform himself, or take part in what became one of the biggest publishing incidents of the last decade. And that’s something that he and millions of other people can do out of the blue now. And what that means, of course, is if you’re in a situation where–you know, the New York Times was definitely in a precarious position when it published the Pentagon Papers. You know, they were–I’m sure they were, and having read Dan Ellsberg’s books, we know that there were heated discussions about their vulnerability to prosecution in that incident. But they were also the New York Times, right? So they had some, they had some back record. And they had the resources to defend themselves.

RS: Well, let me just interrupt for a second. I mean, more than that they were–we have this freedom of the press guarantee in the First Amendment. Now, obviously you can interpret these guarantees however you want. But the idea of going after the press, as opposed to what the press is writing about, or principals or actors, was considered a very basic distinction. And that’s what The New York Times, The Washington Post, were counting on. Suddenly, that distinction has been obliterated. And I want to get back to Bini’s case, but I–so let me just put it in a more pointed way. Is this an extended way of getting at Assange and driving home a bigger political point? Why have they targeted this fellow?

DO: So I think what’s happened was that–so the current Ecuadorian administration is composed of people who were part of the Correa administration, the previous administration, but have taken a very different line. And in many ways, sort of distanced themselves from that previous administration. Part of what that involves is that I don’t think they wanted to take the consequences of holding Assange any longer. So they wanted a more American-friendly foreign policy. But that also meant that they had to change the narrative within Ecuador, where the–providing Assange with refuge was sort of a positive political step that Correa was very proud of, and talked a great deal about. So they had to shift that around pretty quickly. And one of the ways that they could do that was to implicate Assange, or create this idea that WikiLeaks people were going to directly target Ecuador itself. And we haven’t seen any evidence that any such thing was planned; we certainly haven’t seen any evidence that Bini himself was at all involved in this. I think the most important thing to say about Ola Bini is that there’s a particular set of skills that if you want to hack into governments, or extract data, or all of these things that you need, and Ola Bini is not that kind of technologist; Ola Bini builds secure systems that protect you against that kind of exfiltration. He doesn’t knock them down. But of course that’s a fine difference if a government needs to find a fall guy within 24 hours of throwing out Julian Assange from the embassy.

RS: I mean, the reason I’m doing this, aside from–you know, there’s a certain urgency. This fellow, Ola Bini, has been used as a fall guy in the effort to get Assange. And he’s been used as a political prop here. And I get back to my original question: Why aren’t more people concerned about this? I mean, this is a witch hunt. This is an effort–I mean, you came back from your trip, you know, more convinced than ever that this was basically a frame-up.

DO: Right, right. And you know, like I say, and like you said, we’re not a political organization. So it takes some steps for us to actually say that this was a political prosecution rather than a, you know, legitimate criminal prosecution. The question as to why more people don’t care about this, I think it’s happening in Ecuador; not everybody knows what’s going on in Ecuador. I think people, as I say, are often very confused and hazy about what it is that–if somebody says in a press conference, “This person is trying to bring down our government.” And then they show a photo, as they did after the arrest, of a person with shaved hair and a hacker T-shirt, and showed that he had over 10 USB sticks [Laughs], and as they said in his arraignment, he has books on cybersecurity written in English. Again, none of those are actual evidence of any malicious action, but to somebody who’s watched a lot of TV hackers and film hackers, it fits the type, right? So I think people are very hesitant–were very hesitant to doubt these statements when they were first made. And I do feel like people on the left, and more widely, are much more reticent these days to come to the immediate defense of technologists. Because they look at the big corporations that are now big tech corporations, and they see those are the people who are undermining people’s privacy and working in cahoots with repressive governments. What they don’t realize is that there’s a whole wider community of free-acting, human-rights defending technologists who look very similar, but are in fact, I still feel, the first and best hope against–for individuals to defend themselves against that kind of surveillance and that kind of insecurity.

RS: Yeah, that’s a good way to kind of–I don’t want to say wrap it up, but tie this all together. I did a book called They Know Everything About You, and in the course of it I interviewed Barlow, one of your founders. And to this day, I don’t know whether he was a conservative or a liberal or anything else; I guess he was part of the Grateful Dead organization. But when we talked–he was a really brilliant fellow–and when we talked we both agreed, and it seemed to me obvious, that the internet represents the best and worst of all worlds of communication. And that the only way to keep it from being the worst, and try to move it towards the best, is by having individual responsibility on the part of people who know how to work this stuff. That they tell us about the threats to privacy, which the EFF does; they tell us about the issues with net neutrality, they tell us about the issues of regulation of one kind or another. And that they do it in a way that is politically neutral. And so you mentioned, for instance, you have to be on guard against what the communist government of China is doing, and you have to be on guard against what the capitalist government of the United States is doing, and all forms of political activity in between. And at the core of it is, do you thrill to the act of freedom or not? That seems to me the big issue here. And the people who are upset with Julian Assange are saying that he represented an inconvenient truth. You know, he leaked material about the Democratic Party’s internal leaning towards Hillary Clinton, or he leaked material about what she said when she went to Wall Street, or that influenced the election. And then that becomes–the end is more important than the means in the debate. And what you people are about–I don’t want to characterize it, your organization–but basically, you think that if the means are free, the ends are likely to be better.

DO: I think that’s the hope. I think that sometimes that gets accused of being, and certainly Barlow was accused of being a techno-utopian. But I think that actually, it’s a recognition that we could be heading into a utopia, or we could be heading into a dystopia. And this is the moment where we choose which route we go down. This is the moment where you actually–and, talk about anybody, really; I mean, we have 40,000 supporters that pay my bills, and they’re the people who are taking action right now. And compared to many other levers that you can pull, like using technology or promoting technology or advocating for the protection of these systems, is a thing that you can concretely do now that will have a huge effect in the future. And Barlow recognized that in the early nineties. And it’s still true now, right; we’re still in the middle of determining whether we live in a world without privacy, or we live in a world where we can–we do have the freedom to think, and the freedom to do what we want.

RS: But you know, even though I wrote a book about privacy and I think it’s very critical, I think there’s something even more basic here. And it goes to the old slogan of whether the, you know, the truth will make you free. Whether it’s the truth about cops beating up protesters in Hong Kong, or beating them up in the streets of Chicago at different points. The fact of the matter is, there’s either an intrinsic utility to getting at the truth of what governments are doing, and the difference between what they claim they’re doing and what the real force is–or anybody, which is really what whistleblowers are about. Whatever their motives, whatever drives them, the very act of whistleblowing is to challenge secrecy. If you’re going to do it, do it out in the open, and let’s debate what you’re doing. And I think we’re at a pretty depressing moment where a whistleblower like Julian Assange, or even somebody who was only tangentially connected with him, Ola Bini, is without support from people who would normally value that act of the whistleblower, of the truth-seeker.

DO: Yeah. I think that–

RS: That was a–that “yeah,” tell me what’s behind that “yeah.” Is that [Laughs]–

DO: That is, it–I will unpack my “yeah” there. So I think right now, people feel very conflicted about the truth. In that they see a world where there appears to be hundreds of truths being pushed, right? “Truths” in quotation marks. Where they see people being misled by misinformation, and they begin to think, well, maybe what we need to do is to sort of quench this torrent of data at the source. Maybe the problem here is that we have too much, too many truths, too much information. And so they’re beginning to turn to the ideas of censorship, of punishing whistleblowers, of controlled and constrained sources of information. And I think you can concede one part of the world we live in, which is definitely awash with misinformation now, without coming to the conclusion that these old methods–which never worked before–are the correct response to that. I think people are turning away from whistleblowers, and turning away from the idea that finding out these secrets will help you better understand the world and better tackle the world. Because that responsibility is–feels too much to bear. And again, putting my EFF hat back on, I think that one of the things that we’re waiting for, and working towards, is to give individuals the tools to piece together what’s going on, right. Rather than have Facebook hand you what either the government thinks, or what its advertisers think, on a plate, you should have the tools to be able to pick what’s true and what’s not. And in order to do that you need both whistleblowers to, like, present the actual information that will build those conclusions, and you actually need people like Ola Bini who are, you know, complementary to that. I don’t think they’re strongly connected to it, but they allow you to have control over your own devices, control over your own communications, so that this technology you’re using is working for you, not for Mark Zuckerberg, not for Donald Trump, not for the Russian GRU. You know, not for anyone else.

RS: Yeah, let me challenge that. [Laughter] No, because I hear this all the time. The world is–what did you say, we’re now awash in false information, or misinformation. Somehow this is blamed on the internet. And I’m not always a defender of technology, but my goodness, when was the world not awash in misinformation?

DO: Right.

RS: I mean, how did the most advanced, well-educated, scientifically oriented community of the last century embrace Nazism in Germany? You know, and how did we–and I grew up in this country, I’m an old guy now. I grew up with a–always wondered, why are there no black baseball players? I mean, segregation was hardly discussed. We had a segregated armed forces in World War II; that was hardly discussed. You know, you could go down the list of controlled information, wars that were fought without reason–give me the photos, I’ll give you the story, and et cetera, et cetera. And so I think, frankly, I think this is a very dangerous argument. And it justifies the status quo of yore. You know, oh, if we could just go back to the good old days of three networks and four dominant newspapers, and you know, and Time magazine–why, we would have never had something as stupid as the Vietnam War. Or, you know, we wouldn’t have had a segregated South. But that’s garbage.

DO: Yeah.

RS: And I think right now–you know, I’m doing this from the University of Southern California, I’m going to have students in a week and a half. And I tell my students, look, thanks to the internet–and hopefully it’ll stay that way; we can get into discussions of net neutrality and freedom. But hopefully, as it is now, if I say something and you have the slightest doubt, question that it’s true, you can call me out within 20 minutes of research. You can just be googling anything I ever said, and anything I referred to, and you can get original documents. And so in many ways, this is exactly the wrong moment to be afraid of freedom. And certainly freedom from whistleblowers who add to the mix of information you can find out, you can get. And so I just wonder whether you’re–you’re losing heart here [Laughs], by entertaining this argument.

DO: I think I have to entertain it because so many people across the political spectrum feel it. Here’s what I think, is that when we look–you know, because we have to have these moments of doubt. You know, it’s like that old British comedy sketch–

RS: Doubt about freedom?

DO: Not so much about freedom, but like, what are the pros and cons of this technology, right. Is this technology–what’s our trajectory with this technology? And so we sit and, like, we do our research and we talk to people. And the conclusions that we came to, first of all, is that I think one of the biggest engines that people point to, is increasing polarization. And I think there are a couple of things about that. One, that polarization, at least in the United States, has been going on for a very long time. At least in the public space, right? Some of it may be that the public space was slowly introducing more points of view, and we went from kind of a WASP-dominated, public discourse to one that actually included the huge spectrum of opinions that exist within the United States. The other part of it, though, is that if there is a sort of greater polarization going on, it’s certainly pre-internet. And as you said, I think you have to separate sometimes what you see happening from changes in what you are able to see happening. I think that on the internet, a lot of people suddenly got to hear the things that people were saying in private, [that] perhaps they hadn’t wanted to know about, or hadn’t heard about before. And this is, you know, both positive and negative; both people who turned out to be much bigger racists than they would be in the public space, and also people who were suffering far more privation and isolation from the rest of the society than people were aware of.

RS: Let me cut to the chase here.

DO: Yeah.

RS: Let’s take, say, Edward Snowden, and what he revealed about the NSA. We didn’t know that our government was reading our emails and checking our phone conversations and doing all of these things, thanks to conventional journalism. Not the extent of it. And we didn’t know, really, what activities our government was up to, which was in violation of a number of laws, and what have you. Except that this whistleblower who had this, you know, bit of information, revealed it to us. Now, everyone’s conceded that that’s information that in a free society you should have. Right? You should know what your government’s doing; you should know what they can read. I don’t think the utility of that information can be disputed. And I don’t think even people can make an argument that it made us weaker in any way. But the fact is, it wouldn’t have happened if not for this rather rare, odd bird. Because after all, there were thousands of people who knew what Edward Snowden knew, but only one, really, who had the courage–or whatever, the motivation–to reveal it.

DO: Yeah. I mean, I–

RS: So what is the value of–we were emphasizing fake news. But the fake news was most of the news we were getting from the government.

DO: Right, right. And I think–well, so here’s the thing–

RS: And by the way, China is another example, since we don’t want to only be about the U.S. What are people getting in most of China about what’s happening in Hong Kong? They’re getting fake news. What is the alternative to it? People who can hack information and get the word out and get their own little [things] going, and so forth. That’s the only corrective we have in this state of civilization, no?

DO: So I’ll push back a little, but only to kind of agree with you more. Which is that we did actually know a huge chunk of what Edward Snowden said. I mean, we were–NSA court cases were based around evidence that we’d had, but it wasn’t the kind of evidence that gets headlines in the way that Ed Snowden was able to attract the world’s attention to this. So–

RS: Because he had–he had the thumb drive. Because he had the data–

DO: Yeah.

RS: –and they couldn’t dispute it. But let me push back. One of those cases–one of those cases involved the use of AT&T facilities in the Bay Area, right?

DO: Yes, it did.

RS: To spy on people. And the government had an agency there. And when that story came to the Los Angeles Times, where I had worked for 29 years, that story was discounted.

DO: Yeah.

RS: And in fact, I believe Dean Baquet was the editor then; I may have to check that, and now he’s the editor of The New York Times. But however that happened, I can’t hold up to that specific, somehow then The New York Times finally ran with that story. And what I’m saying is that, yes, maybe some aficionados of this world knew what was going on. But even the big–you know, Apple and Google and Facebook, they all said they didn’t know the extent. At least they claimed that.

DO: Well, I think that lots of–I mean, as you said, that’s not–thousands of people knew what Snowden knew, you know. There aren’t really secrets in the sense that, you know, no one knows it except for, like, a couple of people at Area 51. What is important is how you manage to propagate that more widely. And we have this incredible, powerful tool for doing that, for propagating. We have some parallel tools that we’re just beginning to learn to use to ascertain when somebody is propagating something, whether it is the truth or not, right? I think it’s fascinating to understand the process that journalists and the public alike had with something like the Snowden revelations. Which is, yeah, he had a USB key full of information–well, I mean, I could fill a USB key with fake information. How do we know that this is true? And part of the reason we know it’s true is because journalists went through it, and corroborated it, and double-checked it, and connected all of those dots. And also felt free to do that, right? I think that part of this is about why did the L.A. Times–you know, when Mark Klein, who was the whistleblower before Ed Snowden, came to them and came to EFF with this information. Well, they had a certain–perhaps, I’m just guessing here–a certain lack of confidence. Both in, like, their knowledge that they would have about this; maybe they were facing political pressures. Maybe, you know, there was some other story that they wanted to run that had political risks, and they had to choose the pros and cons of this. It’s great that we have millions and millions of people who have different motivations, and different inclinations, and different technical abilities to be able to get this information out. But we do also, part of that system has to also be to empower people to tell the–not the truth from the lies, but you know, the wheat from the chaff. Maybe that’s the best way of doing it. And right now we’re handing that responsibility either to Facebook or Google to do that for us, or the government is actually demanding that these big companies become the gatekeepers again. And like you say, I think this is a solution that didn’t work in the past [Laughs], and it’s a solution that demands better answers than having, you know, the moderators at YouTube or Twitter or Facebook have to decide what the truth is and what isn’t for billions of people around the world.

RS: Well, let me conclude by my own source of optimism. And that’s because even these big companies are multinational. And commerce is multinational, and travel is multinational. In fact, one could even argue the nation-state is a kind of dangerous anachronism, but that’s a whole ‘nother discussion to have. But the fact is, you’re very quickly up against the argument, if we–if our government can do it here, then why shouldn’t the Chinese government or the Saudi government be allowed to do it there? And that’s an argument that no sane person would really want to argue. Because the fact is, there’s a utility to searching for contrarian views, for facts that are inconvenient, and so forth. We know that. And what’s at risk here now is that people, because their ox was gored, their election was hurt, the wrong guy won, and so forth and so on, are losing sight of what I thought the EFF–its most valuable contribution, whether it comes from a libertarian bias or what have you–I thought its most valuable contribution is, really, you don’t trust any government to make that decision. Because any government–and that’s the whole warning of our Constitution–will seek to protect its own power. And that power will corrupt. Isn’t that the assumption? At least that’s what Barlow told me.

DO: Yeah, I think it goes wider than that, though. I think that you–I think that technology is incredibly empowering. And one of the things that we’ve been very fortunate to sort of stumble into is that the bulk of that power has landed in our pockets, rather than in Washington, D.C., or even Silicon Valley, right. That we have an opportunity to take that technology and spread it–spread its empowering ability as thinly and widely as possible. And I think that that’s probably the way I’d interpret what–for a huge chunk of when we were working, or EFF was working, the government was the most clear and present threat to people’s privacy and security online. And I take your point, I’m going to–let’s say freedom online, right? That’s much broader than those two, those two characteristics. I think we shifted into a place where people understandably are just as worried about the rise of these monolithic companies based not 50 miles away from where I’m sitting right now, and their capabilities. And I think what it’s about is about making sure that they don’t get to hoard this power, but we still keep it in people’s pockets. We still make sure that you can, you know, trust your phone or trust your laptop to collect all of this information and then give you what you want or need, based on what you’ve decided you want your life to be. And that’s a, that’s a big challenge right now, because I think people really do feel overwhelmed and frightened. And I think fear is always a very, very difficult place to make an argument for freedom.

RS: Yes, except it was Franklin Roosevelt who warned us the only thing we have to fear is fear itself. And I want to conclude this, after this interesting discussion, bringing it back to Ola Bini. And the reason I want to bring it back is, you know, it always turns out it’s the Tom Paines. It’s the Edward Snowdens. It’s the Ola Binis. It’s the Martin Luther Kings. There are these individuals who say, no, that doesn’t smell right, that doesn’t sound right, I’m not going to go along. You know, I’m going to reveal this. Whether it’s Chelsea Manning, or you know, you could go down the list. You may not like all these people, they may not be people you want to have as your closest friends, or what have you. But the fact of the matter is, they’re indispensable to human sanity. Because they are willing to, like the guy in Tiananmen Square who could stand in front of the tanks, it’s just a universal truth, anywhere in the world, most people will go along with power. Whether that’s power because they’re working at Facebook and they go along with it for their career, or they go along with a totalitarian government just for their safety. And what’s really at stake in this Ola Bini case–if I could make a feature film on it, maybe Oliver Stone or somebody will–here–tell us, let’s just end, and how do people get more information about this? You know, here’s a guy who, what, he just wanted to make the internet safer for dissent, for independent thought? Wasn’t that what drove him?

DO: Yeah. Yeah, and I think, you know, one of the reasons why people turn their suspicion on him is that, you know, he built things that were super-secure; he, all his software was, his laptops were encrypted. And when they asked the passwords, he said no. Well, I’m not sure everybody would do that in that situation, particularly if they were innocent. But that’s an important principle, right? That’s an important principle, to be able to be secure in your documents and effects. And–

RS: Well, it’s what the Fourth Amendment guaranteed, yes.

DO: Right, right. And they didn’t have any evidence to charge him. He made that stand. I wonder sometimes if I would be as brave and stick to my principles as well as that when I was under, you know, that kind of pressure. But that’s what it takes, I think. That’s what it takes, and it is a shame when standing on a point of principle is the thing that gets you into trouble, far more than anything that they might imagine that you’re doing that might actually cause damage to the world, rather than maybe have a chance to fix it.

RS: So for people who want to–and they should want to follow up on this, what’s the best way? What is it called, the EFF EFFector or whatever?

DO: You can sign up for EFFector. You can also go to our blog and sign up for our Twitter. We’re at EFF.org, wherever you go. The Ola Bini campaign themselves have a website called Free Ola Bini, which can give you much more information on Ola himself. I sat and talked to him; he’s a very impressive young man, and I hope more people pay attention to what he’s having to face, and what he represents.

RS: So we just need John Lennon to come up with a song to free Ola Bini. And you know, I actually, I want to criticize myself here. I routinely, every month, give money to WikiLeaks–Wikipedia, Wikipedia, not WikiLeaks. [Laughter] Wikipedia, just because I think it’s, you know, good that they’re nonprofit and everything, and should be around. I don’t give a lot, but I give, you know, just some bucks. And I realized I haven’t done that with EFF. I’ve used EFF as a journalist; I didn’t know that your support base was 40,000 people who want to help you. And I want to end this the same way I began, by saying I really admire the independence of what you guys do there, or men and women do there. And that, you know, you call it as it is without fear or favor. And that’s really what’s required here, and that should apply to the internet world. So that’s it for this edition of Scheer Intelligence. We’ll be back next week. Our producer is Joshua Scheer. Here at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism we have Sebastian Grubaugh, who pulls it all together. And at Sports Byline in San Francisco, Darren Peck provided the services to bring our speaker to us. So, see you again next week with another edition of Scheer Intelligence.

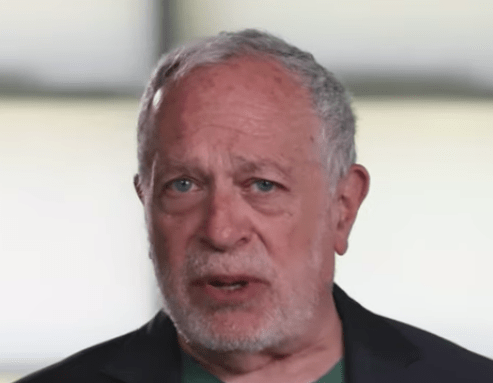

Robert Reich: CEOs Have the Whole System Gamed

Average CEO pay at big corporations topped 14.5 million dollars in 2018. That’s after an increase of 5.2 million dollars per CEO over the past decade, while the average worker’s pay has increased just 7,858 dollars over the decade.

Just to catch up to what their CEO made in 2018 alone, it would take the typical worker 158 years.

This explosion in CEO pay relative to the pay of average workers isn’t because CEOs have become so much more valuable than before. It’s not due to the so-called “free market.”

Related Articles

The Appalling Numbers Behind America's CEO Pay

by

The 4 Biggest Conservative Lies About Inequality

by Robert Reich

It’s due to CEOs gaming the stock market and playing politics.

How did CEOs pull this off? They followed these five steps:

First: They made sure their companies began paying their executives in shares of stock.

Second: They directed their companies to lobby Congress for giant corporate tax cuts and regulatory rollbacks.

Third: They used most of the savings from these tax cuts and rollbacks not to raise worker pay or to invest in the future, but to buy back the corporation’s outstanding shares of stock.

Fourth: This automatically drove up the price of the remaining shares of stock.

Fifth and finally: Since CEOs are paid mainly in shares of stock, CEO pay soared while typical workers were left in the dust.

How to stop this scandal? Five ways:

1. Ban stock buybacks. They were banned before 1982 when the Securities and Exchange Commission viewed them as vehicles for stock manipulation and fraud. Then Ronald Reagan’s SEC removed the restrictions. We should ban buybacks again.

2. Stop corporations from deducting executive pay in excess of 1 million dollars from their taxable income – even if the pay is tied to so-called company performance. There’s no reason other taxpayers ought to be subsidizing humongous CEO pay.

3. Stop corporations from receiving any tax deduction for executive pay unless the percent raise received by top executives matches the percent raise received by average employees.

4. Increase taxes on corporations whose CEOs make more than 100 times their average employees.

5. Finally, and most basically: Stop CEOs from corrupting American politics with big money. Get big money out of our democracy. Fight for campaign finance reform.

Grossly widening inequalities of income and wealth cannot be separated from grossly widening inequalities of political power in America. This corruption must end.

Bolsonaro May Send Army to Fight Massive Amazon Fires

RIO DE JANEIRO—Under increasing international pressure to contain record numbers of fires in the Amazon, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro said Friday he may send the military to battle the massive blazes.

“That’s the plan,” said Bolsonaro. He did not say when the armed forces would get involved but suggested that action could be imminent.

Bolsonaro has previously described rainforest protections as an obstacle to economic development, sparring with critics who note that the Amazon produces vast amounts of oxygen and is considered crucial in efforts to contain global warming.

In escalating tension over the fires, France accused Bolsonaro of having lied to French leader Emmanuel Macron and threatened to block a European Union trade deal with several South American states, including Brazil.

Related Articles

The Amazon Is Burning, and the Entire Planet Is at Risk

by

Scientists Definitively Debunk the Biggest Climate Change Lie

by

Small numbers of demonstrators gathered outside Brazilian diplomatic missions in Paris, London and Geneva to urge Brazil to do more to fight the fires.

Neighboring Bolivia and Paraguay have also struggled to contain fires that swept through woods and fields and, in many cases, got out of control in high winds after being set by residents clearing land for farming. About 7,500 square kilometers (2,900 square miles) of land has been affected in Bolivia, according to Defense Minister Javier Zavaleta.

On Friday, a B747-400 SuperTanker arrived in Bolivia to help with the firefighting effort. The U.S.-based aircraft can carry nearly 76,000 liters (20,000 gallons) of retardant, a substance used to stop fires.

Some 370 square kilometers (140 square miles) have burned in northern Paraguay, near the borders with Brazil and Bolivia, said Joaquín Roa, a Paraguayan state emergency official. He said the situation has stabilized.

In escalating tension over the fires, France accused Bolsonaro of having lied to French leader Emmanuel Macron and threatened to block a European Union trade deal with several South American states, including Brazil.

The specter of possible economic repercussions for Brazil and its South American neighbors show how the Amazon is becoming a battleground between Bolsonaro and Western governments alarmed that vast swathes of the region are going up in smoke on his watch.

Ahead of a Group of Seven summit in France this weekend, Macron’s office issued a statement questioning Bolsonaro’s trustworthiness.

Brazilian statements and decisions indicate Bolsonaro “has decided to not respect his commitments on the climate, nor to involve himself on the issue of biodiversity,” Macron’s statement said.

It added that France now opposes an EU trade deal “in its current state” with the Mercosur bloc of South American nations that includes Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay.

Finnish Prime Minister Antti Rinne also expressed concern, saying he is “truly worried about the attitude Brazil seems to have adopted right now regarding” fires in the Amazon.

“Brazilian rainforests are vital for the world’s climate” and Brazil should do whatever it can to stop the blazes, said Rinne, whose country holds the European Union’s rotating presidency.

Bolsonaro has accused Macron of politicizing the issue, and his government said European countries are exaggerating Brazil’s environmental problems in order to disrupt its commercial interests. Bolsonaro has said he wants to convert land for cattle pastures and soybean farms.

Even so, Brazilian state experts have reported a record of nearly 77,000 wildfires across the country so far this year, up 85% over the same period in 2018. Brazil contains about 60% of the Amazon rainforest, whose degradation could have severe consequences for global climate and rainfall.

___

Associated Press journalists John Leicester in Paris; Juan Karita in Santa Cruz, Bolivia; Pedro Servin in Asunción, Paraguay; and Christopher Torchia in Caracas, Venezuela contributed to this report.

Donald Trump Is Coming for Medicare and Social Security

After exploding the federal budget deficit with over a trillion dollars in tax cuts for the rich and massive corporations, President Donald Trump is reportedly considering using his possible second term in the White House to slash Medicare and Social Security—the final part of a two-step plan progressives have been warning about since before the GOP tax bill passed Congress in 2017.

The New York Times reported this week that, with the budget deficit set to surpass $1 trillion in 2020 thanks in large part to Trump’s tax cuts and trade war, Republicans and right-wing groups are pressuring the president to take a sledgehammer to Social Security and Medicare, widely popular programs Trump vowed not to touch during his 2016 campaign.

Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.) told the Times that his party has discussed cutting Medicare and Social Security with Trump and said the president has expressed openness to the idea.

“We’ve brought it up with President Trump, who has talked about it being a second-term project,” said Barrasso.

Senator John Thune (R-S.D.), the number two Republican in the Senate, echoed Barrasso, saying it is “going to take presidential leadership to [cut Social Security and Medicare], and it’s going to take courage by the Congress to make some hard votes. We can’t keep kicking the can down the road.”

All to pay for his #GOPTaxScam… Horrific. https://t.co/IiTC2EUHY1

— For Tax Fairness (@4TaxFairness) August 22, 2019

“The Trump/GOP tax cuts for the wealthy will add over $1.5 trillion in debt,” said the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare. “Now we know how they’ll pay for those tax cuts, by cutting Social Security and Medicare.”

According to the Washington Post, Trump has already “instructed aides to prepare for sweeping budget cuts if he wins a second term in the White House.”

“Trump’s advisers say he will be better positioned to crack down on spending and shrink or eliminate certain agencies after next year, particularly if Republicans regain control of the House of Representatives,” the Post reported last month.

The president, despite his campaign promises, has included major cuts to Social Security and Medicare in his budget proposals—while predictably demanding massive increases in Pentagon spending.

In his budget blueprint for fiscal year 2020, as Common Dreams reported, Trump called for $845 billion in cuts to Medicare and $25 billion in cuts to Social Security.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), a 2020 Democratic presidential candidate, tweeted Thursday his belief that Trump will not have a chance to carry out his “second-term project.”

“Mr. Trump, you are not going to have a second term,” said Sanders.