Chris Hedges's Blog, page 166

August 30, 2019

Is America Finally Waking Up to Its White Nationalism Problem?

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published.

Late in 2017, ProPublica began writing about a California white supremacist group called the Rise Above Movement. Its members had been involved in violent clashes at rallies in Charlottesville, Virginia, and several cities in California. They were proud of their violent handiwork, sharing videos on the internet and recruiting more members. Our first article was titled “Racist, Violent, Unpunished: A White Hate Group’s Campaign of Menace.”

More articles followed, and another neo-Nazi group, Atomwaffen Division, was exposed.

Michael German, a former federal agent who spent years infiltrating white supremacist groups, said the work of the groups constituted “organized criminal activity,” and he asked, in so many words, “Where is the FBI?”

Federal authorities wound up arresting eight members of the Rise Above Movement, and five of them have since pleaded guilty to federal riot charges. This summer, FBI Director Christopher Wray testified that, over the last nine months, the bureau’s domestic terrorism investigations had led to 90 arrests, many of them involving white supremacists. And in recent weeks, there have been additional arrests: a Las Vegas man said to be affiliated with Atomwaffen and a young man in Chicago affiliated with Patriot Front, another white supremacist group.

The activity concerning the threat of white racists has gone beyond arrests. There have been a variety of proposals making their way through Congress aimed at creating federal criminal statutes that might make prosecuting domestic terrorism threats more effective. The FBI Agents Association has supported new laws.

We went back to German, a fellow with the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty and National Security Program and the author of the forthcoming book “Disrupt, Discredit, and Divide: How the New FBI Damages Democracy,” to inquire about the significance of the seeming burst of enforcement efforts.

The FBI, made aware of German’s observations and arguments, declined to comment, but it provided a link to recent testimony by bureau officials before Congress.

There have been a handful of arrests of alleged white supremacists in recent weeks. What do you make of them? A temporary reaction to the El Paso, Texas, massacre? Evidence of a deeper commitment by the FBI? Coincidence?

First, the arrests of several white nationalists allegedly planning acts of violence since the El Paso attack demonstrate beyond question that the FBI has all the authority it needs to act proactively against white supremacist violence. Claims from the FBI Agents Association and other current and former Justice Department officials that the government needs new laws to target this violence are false. I worked successful domestic terrorism undercover operations against white supremacists in the 1990s, and no one ever suggested we didn’t have all the authority we needed.

It is hard to know if these arrests mark a new increase in attention to far-right violence because the Justice Department doesn’t keep reliable data about how many investigations and prosecutions it conducts against white supremacists. It sometimes categorizes them as domestic terrorism, other times as hate crimes or even gang crimes, obscuring the true scope of the violence they inflict on our society. And since the Justice Department defers the investigation and prosecution of hate crimes to state and local law enforcement, the FBI doesn’t even know how many people white supremacists kill each year.

The Justice Department and FBI de-prioritize the investigation and prosecution of far-right violence as a matter of policy, not a lack of authority. These recent cases are a result of increased public pressure to do something about these crimes. But the Justice Department and FBI have done nothing to amend their policies that de-prioritize the investigation of white supremacist crimes. Maintaining public pressure and focusing on changing the biases that drive these policies is essential to forcing a change in priorities at these agencies.

At least two of the arrests appear to have involved a certain infiltration of white hate groups online. Noteworthy? Overdue?

Many researchers have suggested that the internet fuels white nationalist violence and therefore suppression of these online communities is necessary. But white supremacists have been killing people in this country for more than a 100 years before the internet was created. They use the internet more to communicate today than 20 years ago, just like all the rest of us do, but that doesn’t mean there is more violence. In fact, as the recent cases suggest, internet communications make them far easier to track and infiltrate, so it is more a boost to law enforcement more than to violent militants.

But mass monitoring of social media for clues isn’t an effective strategy, as there are far more people expressing racist ideas online than committing violence. The FBI would be very busy chasing down false leads, which would only dull the response. Instead, the FBI and other law enforcement agencies should work from reasonable criminal predicates. Where there is objectively credible evidence that someone is planning to do harm they should act. The number of homicides in the U.S. has fallen significantly since the 1980s and 1990s, but so has the clearance rate. Even though there are fewer homicides now, fewer are being solved. I think it is because we are spending so much time and resources on suspicion-less surveillance and intelligence gathering rather than traditional evidence-based law enforcement tactics.

There is a variety of proposed legislation aimed at creating more specific federal domestic terrorism statutes. Worthy? Wrongheaded?

Congress shouldn’t pass broad new laws or stiffer penalties, as there are already dozens of federal statutes outlawing domestic terrorism, hate crimes and organized violent crime that carry significant sentences. There are bills that demand better data collection by the Justice Department, which would reveal where counterterrorism resources should be devoted and where they are being wasted. This is the better approach. Proper policies can’t be developed without a better understanding of the crime problem.

In the meantime, Congress should explore mechanisms to fund and implement community-led restorative justice practices that would redress the communal injuries hate crimes are designed to inflict. White supremacists try to intimidate and marginalize the communities they attack. Making sure these communities are cared for, protected and supported after an attack frustrates that goal. More policing isn’t always the right answer, and certainly not the only one.

There was recently news coverage of leaked FBI threat assessments listing the promotion of an array of political conspiracy theories as a domestic menace. What did you make of that?

The FBI intelligence assessment declaring conspiracy theorists a domestic terrorism threat should worry all of us. It had a line defining conspiracy theorists as those who do not hold the “official” or “prevailing” view on a particular topic. Given that the intelligence community has often been the promoter of false narratives, particularly about the lawfulness of its own conduct, giving them license to target people who disagree with the “official” view is chilling. It is basically a declaration that the government will treat dissent as dangerous.

There was a recent case that has to puzzle the public. A Coast Guard lieutenant was arrested with guns and a target list of politicians and others, and held on firearms charges. At least one federal magistrate thought he deserved bail because the government had failed to provide evidence of terrorist acts and the simple gun charges didn’t merit him being held without bail. A judge overturned the magistrate and kept the lieutenant held. All that can be hard to follow for an American public concerned about safeguarding its rights and its citizens. Thoughts?

It’s difficult to talk about cases that have not yet gone to trial because there is little information available outside the government’s allegations, which haven’t been proven yet. But there are some principles of our legal system that should be applied in all cases, including this one, even though we seem to have moved far from them over the years. First, people are innocent until proven guilty. That means, absent government evidence that a defendant poses a threat to the public or to abscond, that person should be released until trial, and bond should only be used to guarantee appearance. Of course, many people with allegations that seem less serious than those against the Coast Guard officer don’t receive bond, but that is a question for those judges and prosecutors, not the ones involved in this case.

They train to fight. They post their beatings online. And so far, they have little reason to fear the authorities.

Obviously the government initially failed to present evidence that justified pretrial confinement, so based on the charged conduct the judge considered bond. This result should happen more often, not less. When the government got its act together, added charges and presented evidence of a potential threat to the public, the judge ordered him held. The burden is on the government and shouldn’t be met through sensationalized press releases but through reasonable evidence presented in court.

Second, prosecutors can only charge people with crimes they committed, not crimes the government thinks they might commit in the future. Lots of people stockpile weapons in this country. And if keeping a creepy diary is against the law, plenty of people will go to jail. Where the government has evidence that laws were broken, they have the power to act, which — ironically given the hyperbolic news coverage of this incident — they did here. The officer was arrested and is being prosecuted for crimes the government alleges he committed, so there seems to be no problem.

The Justice Department seems to have tried to make this into a test case for demanding new authorities, even though prosecutors obviously had enough evidence to address the threat. Compare this case to the Larry Hopkins case in New Mexico. There the FBI received a tip in 2017 that a formerly incarcerated felon who was the “commander” of a border militia group that harassed migrants was also planning to assassinate Hillary Clinton, George Soros and Barack Obama. The FBI went to Hopkins’ trailer and recovered nine firearms he was not permitted to own due to his previous felony convictions, which included weapons charges and impersonating a police officer. The FBI did not arrest Hopkins and instead let him continue to operate with his militia group for 18 months, harassing migrants in the desert, until a video of his group pointing weapons at a group of migrants they detained went viral and sparked public outrage. Only then did the FBI take action.

Comparing the two cases, the FBI had much more significant evidence of potential dangerousness from Hopkins than from the Coast Guard officer, yet they took no action against Hopkins. I think they saw the Coast Guard officer’s case as a ready-made scandal near D.C. that they could sensationalize to pressure Congress into passing a broad new domestic terrorism law. Obviously, they already had enough authority to arrest him on the drug and weapons charge, and his possession of illegal silencers. So there was no lack of authority to arrest him in the first place. It was a manufactured scandal.

What, if anything, is different today than two summers ago in Charlottesville concerning the threat of white supremacists and the government’s response at all levels to it?

I think the violence in Charlottesville was a wake-up call for everyone. The media finally recognized that white supremacists were engaging in terrorism, too. The level of violence these far-right groups inflict has been persistent over time, but studies show that the media gave terrorist acts perpetrated by Muslims 350% more coverage than violence committed by other terrorists. The increased reporting post-Charlottesville eventually caused policymakers to take notice, which in turn compelled the FBI and Justice Department to begin to take these crimes more seriously. The media coverage drives public perception, which causes policymakers to act. It remains to be seen whether they react in a way that improves the situation and builds a more inclusive society, or makes it worse by giving law enforcement broad powers to continue targeting marginalized communities agitating for civil rights and changes in government policies.

Trump Eyes Mental Institutions as Answer to Gun Violence

WASHINGTON — When shots rang out last year at a high school in Parkland, Florida, leaving 17 people dead, President Donald Trump quickly turned his thoughts to creating more mental institutions.

When back-to-back mass shootings in Dayton, Ohio, and El Paso, Texas, jolted the nation earlier this month, Trump again spoke of “building new facilities” for the mentally ill as a way to reduce mass shootings.

“We don’t have those institutions anymore and people can’t get proper care,” Trump lamented at a New Hampshire campaign rally not long after the latest shootings.

Now, in response to Trump’s concerns, White House staff members are looking for ways to incorporate the president’s desire for more institutions into a long list of other measures aimed at reducing gun violence.

It’s the latest example of White House policy aides scrambling to come up with concrete policies or proposals to fill out ideas tossed out by the president. And it’s an idea that mental health professionals say reflects outdated thinking on the treatment of mental illness.

Trump sometimes harks back to his earlier years in New York to explain his thinking on preventing future mass shootings. He recently recalled to reporters how mentally ill people ended up on the streets and in jails in New York after the state closed large psychiatric hospitals in the 1960s and 1970s.

“Even as a young guy, I said, ‘How does that work? That’s not a good thing,’” Trump said.

As the White House looks for ways to fight gun violence, officials have looked at Indiana as one potential model in addressing mental illness.

The state opened a new 159-bed psychiatric hospital in March, Indiana’s first in more than 50 years. The hospital is focused on treating patients with the most challenging psychiatric illnesses and then moving them into treatment settings within the community or state mental health system.

Plans for the hospital were announced when Vice President Mike Pence was the state’s governor.

“Our prisons have become the state’s largest mental health provider,” Pence said in 2015. “Today, that begins to change.”

But Trump’s support for new “mental institutions” is drawing pushback from many in the mental health profession who say that approach would do little to reduce mass shootings in the United States and incorrectly associates mental illness with violence.

Paul Gionfriddo, president and chief executive of the advocacy group Mental Health America, said Trump is pursuing a 19th century solution to a 21st century problem.

“Anybody with any sense of history understands they were a complete failure. They were money down the drain,” said Gionfriddo.

The number of state hospital beds that serve the nation’s most seriously ill patients has fallen from more than 550,000 in the 1950s to fewer than 38,000 in the first half of 2016, according to a survey from the Treatment Advocacy Center, which seeks policies to overcome barriers to treatment.

John Snook, the group’s executive director, said Trump’s language “hasn’t been helpful to the broader conversation.” But he said the president has hit on an important problem — a shortage of beds for the serious mentally ill.

“There are headlines every day in almost every newspaper talking about the consequences of not having enough hospital beds, huge numbers of people in jails, homelessness and ridiculously high treatment costs because we’re trying to help people in crisis care,” Snook said.

While Snook is not advocating a return to the 1950s, when there were 337 state hospital beds per 100,000 people in the U.S., he says states went too far in reducing facilities. He said the 2016 level of 11.7 beds per 100,000 people is inadequate.

Gionfriddo agreed more resources for the mentally ill are needed, but said any beds added should go to local, general hospitals, where patients would receive care for a full range of physical and mental illnesses.

That will require more federal money and loosening Medicaid’s restrictions on mental health funding, he said. The first part is highly unlikely in the current fiscal environment, with the federal government expected to run a $1 trillion deficit in the next fiscal year.

But the administration has taken steps on the second part of the equation. A longstanding federal law has barred Medicaid from paying for mental health treatment in facilities with more than 16 beds to prevent “warehousing” of the mentally ill at the expense of federal taxpayers.

The administration in recent months said it will allow states to seek waivers from that restriction, provided they can satisfy certain requirements. Such waivers often take years to wind their way through the regulatory process.

The National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors has a different suggestion. After the El Paso and Dayton shootings, it recommended that Congress add $35 million for a block grant program to help states provide more community-based care to people in a mental health crisis.

When he ran for president, Trump issued a position paper on his gun positions that was more in line with what many mental health experts say: “We need to expand treatment programs, because most people with mental health problems aren’t violent, they just need help,” the paper said. “But for those who are violent, a danger to themselves or others, we need to get them off the street before they can terrorize our communities.”

Marvin Swartz, a professor in psychiatry at Duke University, said research has shown that even if society were to cure serious mental illness, total violence would decline by only about 4 percent. He said he’s seen no evidence that more psychiatric beds would reduce mass homicides or individual homicides.

“It would be a good thing to have more treatment resources, but the effect on gun violence would be minuscule,” Swartz said.

____

Associated Press writer Jill Colvin contributed to this report.

Does the New York Times Want Democrats to Lose in 2020?

Thomas Edsall’s demographic analysis is almost always misleading (FAIR.org, 2/10/15, 10/9/15, 6/5/16, 3/30/18, 7/24/19)—and his latest column for the New York Times (8/28/19) is no exception.

“We Aren’t Seeing White Support for Trump for What It Is,” the headline complains—with the subhead explaining, “A crucial part of his coalition is made up of better-off white people who did not graduate from college.”

Why does this matter? Edsall’s column is largely a write-up of a paper by two political scientists, Herbert Kitschelt and Philipp Rehm, who note that better-off whites without college degrees “tend to endorse authoritarian noneconomic policies and tend to oppose progressive economic policies,” and are therefore “a constituency that is now decisively committed to the Republican Party.” (By “authoritarian policies,” the researchers are mainly talking about racism and xenophobia.) Low-income, low-education whites, by contrast, “tend to support progressive economic policies and tend to endorse authoritarian policies on the noneconomic dimension,” and are therefore “conflicted in their partisan allegiance.”

What’s at stake in presenting one of these constituencies as “crucial” is how you approach the task of defeating Trump: If he’s turning out his key supporters through race-baiting and immigrant-bashing, the argument goes, then Democrats need to take care not to be too outspoken on issues of race and immigration. And so Edsall confidently concludes:

The 2020 election will be fought over the current loss of certainty—the absolute lack of consensus—on the issue of “race.”… Democrats are convinced of the justness of the liberal, humanistic, enlightenment tradition of expanding rights for racial and ethnic minorities. Republicans, less so…. If Democrats want to give themselves the best shot of getting Trump out of the White House…they must make concerted efforts at pragmatic diplomacy and persuasion—and show a new level of empathy.

(This is an argument Edsall has made before—see “What’s a Non-Racist Way to Appeal to Working-Class Whites? NYT’s Edsall Can’t Think of Any,” FAIR.org, 3/30/18.)

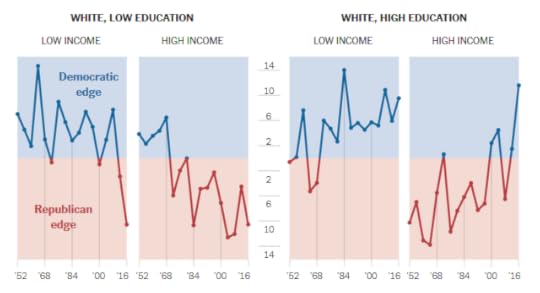

But there’s an entirely different conclusion that one can draw from the 21st century political terrain—one that is better supported by the data presented in Edsall’s column. Take a close look at the graphic he presents depicting “the shifting voting patterns of whites”:

Bear in mind that these are not equal slices of the electorate: As Edsall notes, the low-income, low-education voters are about 40% of white voters; the high-income, low-education voters are 22%; the low-income, high-education group is 14%; and the high-income, high-education make up 26% of the white vote.

So the supposedly “crucial” better-off white non–college grads are about half as plentiful as their poorer counterparts—and they have been voting Republican fairly consistently since 1972, through good years for Republicans and bad. What was actually crucial to Trump’s 2016 success is that the larger group of poorer less-educated whites, which traditionally leans Democratic or splits its vote, went decisively Republican.

And while this group was susceptible to Trump’s racist appeals, equally important (according to Edsall’s political scientist sources) was his “repeated campaign promise to protect Medicare and Social Security.” The false impression that Trump was a moderate Republican on economic issues “removed cognitive dissonance and inhibitions” that might deter such voters from supporting an economic conservative, leaving them free to be swayed by Trump’s appeal to a white racial identity.

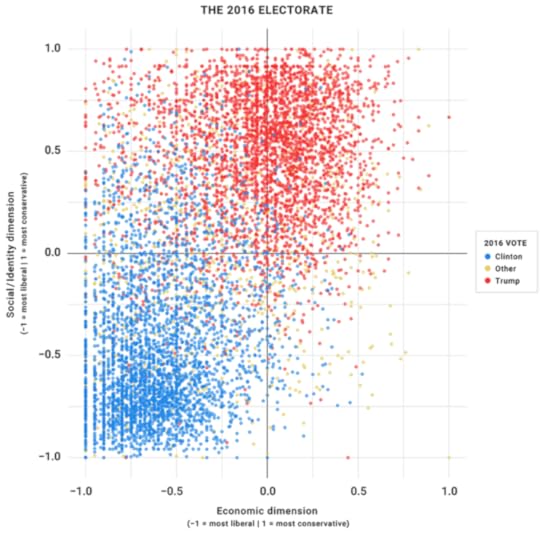

Where the votes are: sorting Trump and Clinton supporters by views on economic and social issues (New York, 6/18/17; see FAIR.org, 10/28/17).

If that’s the truly crucial group, then Democrats will not win the 2020 election by embracing, as Edsall seems to suggest, an agnosticism on the issue of race (or “the issue of ‘race,’” as he puts it), but rather by advancing a strongly progressive, redistributionist economic message. It’s political common sense that if the voters who are up for grabs are those who are socially conservative and economically progressive, then Democrats should emphasize left-wing economics and Republicans should stress right-wing social policies—while crucially reassuring their bases that they maintain their commitments to a progressive social agenda or a conservative economic program, respectively. (See FAIR.org, 6/20/17.)

But this common sense runs against the New York Times‘ historic role of guiding the Democratic Party away from positions that threaten the wealthy. This is why Adolph Ochs, great-great-grandfather of the current Times publisher, was bankrolled by bankers to buy the paper in 1896 (FAIR.org, 10/28/17), and it’s why the paper today has an editorial page editor who proudly declares, “The New York Times is in favor of capitalism” (FAIR.org, 3/1/18). Edsall, it seems, has the task of providing the intellectual arguments for why the Democrats should not adopt the progressive economic agenda that would benefit them electorally—a job that necessarily involves a great deal of doubletalk and hand-waving.

Hong Kong Protest March Banned; Democracy Activists Arrested

HONG KONG—Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong and another core member of a pro-democracy group were granted bail Friday after being charged with inciting people to join a protest in June, while authorities denied permission for a major march as they took what appears to be a harder line on this summer’s protests.

The organizers of Saturday’s march, the fifth anniversary of a decision by China against allowing fully democratic elections for the leader of Hong Kong, said they were calling it off after an appeals board denied permission. It was unclear whether some protesters would still demonstrate on their own.

The police commander of Hong Kong island, Kwok Pak Chung, appealed to people to stay away from any non-authorized rallies, warning that those caught could face a five-year jail term.

He told a daily news conference that he was aware of social media messages urging people to take strolls or hold rallies in the name of religion. Kwok urged the public to “make a clear break with all acts of violence and stay away from locations where violent clashes may take place.”

Police have been rejecting more applications for rallies and marches, citing violence at or after earlier ones. They also are arresting people for protests earlier this summer, a step they said was a natural development as investigations were completed.

Andy Chan, the leader of a pro-independence movement, was arrested at the airport Thursday night under suspicion of rioting and attacking police. Three other protesters were taken in earlier this week for alleged involvement in the storming of the legislative building on July 1, when protesters broke in and vandalized the main chamber.

A leader of the Civil Human Rights Front, which had called Saturday’s march, said that Hong Kong residents would have to think about other ways to voice their anger if the police keep banning protests.

“The first priority of the Civil Human Rights Front is to make sure that all of the participants who participate in our marches will be physically and legally safe. That’s our first priority,” said Bonnie Leung. “And because of the decision made by the appeal board, we feel very sorry but we have no choice but to cancel the march.”

Police arrested Wong and Agnes Chow on Friday morning. They were charged with participating in and inciting others to join an unauthorized protest outside a police station on June 21. Wong was also charged with organizing it.

“We will continue our fight no matter how they arrest and prosecute us,” Wong told reporters outside a courthouse after they were released on bail.

Wong, one of the student leaders of the Umbrella Movement in 2014, was released from prison in June after serving a two-month sentence related to that major pro-democracy protest.

Wong and Chow, both 22, are members of Demosisto, a group formed by Wong and others in 2016 to advocate self-determination for Hong Kong. Chow tried to run for office last year, but was disqualified because of the group’s stance on self-determination. China does not consider independence an option for the semi-autonomous territory.

Demosisto is not a leader of this year’s movement, which describes itself as “leaderless,” though Wong has spoken out regularly in support of the demonstrations.

The protests were set off by extradition legislation that would have allowed suspects to be sent to mainland China to face trial and expanded to general concerns that China is chipping away at the rights of Hong Kong residents.

The extradition bill was suspended but the protesters want it withdrawn and are also demanding democracy and an independent inquiry into police actions against protesters.

Demosisto first reported the arrests of Wong and Chow on its social media accounts, saying Wong was pushed into a private car as he was heading to a subway station around 7:30 a.m. and was taken to police headquarters. It later said Chow had also been arrested, at her home.

Chow echoed Wong’s comments, saying “we Hong Kong people won’t give up and won’t be scared … we will keep fighting for democracy.”

___

Associated Press writers Yanan Wang in Beijing and Eileen Ng in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and videojournalist Johnson Lai in Hong Kong contributed to this story.

August 29, 2019

Comey Said to Violate FBI Policies in Handling of Memos

WASHINGTON — Former FBI Director James Comey violated FBI policies in his handling of memos documenting private conversations with President Donald Trump, the Justice Department’s inspector general said Thursday.

The watchdog office said Comey broke bureau rules by giving one memo containing unclassified information to a friend with instructions to share the contents with a reporter. Comey also failed to return his memos to the FBI after he was dismissed in May 2017, retaining copies of some of them in a safe at home, and shared them with his personal lawyers without permission from the FBI, the report said.

“By not safeguarding sensitive information obtained during the course of his FBI employment, and by using it to create public pressure for official action, Comey set a dangerous example for the over 35,000 current FBI employees — and the many thousands more former FBI employees — who similarly have access to or knowledge of non-public information,” the report said.

Related Articles

The Mythical Integrity of Robert Mueller and James Comey

by

The report is the second in as many years to criticize Comey’s actions as FBI director, following a separate inspector general rebuke for decisions made during the investigation into Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server. It is one of multiple inspector general investigations undertaken in the last three years into the decisions and actions of Comey and other senior FBI leaders.

Trump, who has long regarded Comey as one of his principal antagonists in a law enforcement community he sees as biased against him, cheered the conclusions on Twitter. He wrote: “Perhaps never in the history of our Country has someone been more thoroughly disgraced and excoriated than James Comey in the just released Inspector General’s Report. He should be ashamed of himself!”

The White House in a separate statement called Comey a “proven liar and leaker.”

But the report denied Trump and his supporters, who have repeatedly accused Comey of leaking classified information, total vindication. It found that none of the information shared by him or his attorneys with anyone in the media was classified. The Justice Department has declined to prosecute Comey.

Comey seized on that point in defending himself on Twitter, saying, “I don’t need a public apology from those who defamed me, but a quick message with a ‘sorry we lied about you’ would be nice.”

He also added: “And to all those who’ve spent two years talking about me ‘going to jail’ or being a ‘liar and a leaker’ — ask yourselves why you still trust people who gave you bad info for so long, including the president.”

At issue in the report are seven memos Comey wrote between January 2017 and April 2017 about conversations with Trump that he found unnerving or unusual.

These include a Trump Tower briefing at which Comey advised the president-elect that there was salacious and unverified information about his ties to Moscow circulating in Washington; a dinner at which Comey says Trump asked him for loyalty and an Oval Office meeting weeks later at which Comey says the president asked him to drop an investigation into former national security adviser Michael Flynn.

One week after he was fired, Comey provided a copy of the memo about Flynn to Dan Richman, his personal lawyer and a close friend, and instructed him to share the contents with a specific reporter from The New York Times.

Comey has said he wanted to make details of that conversation public to prompt the appointment of a special counsel to lead the FBI’s investigation into ties between Russia and the Trump campaign. Former FBI Director Robert Mueller was appointed special counsel one day after the story broke.

The inspector general’s office found Comey’s rationale lacking.

“In a country built on the rule of law, it is of utmost importance that all FBI employees adhere to Department and FBI policies, particularly when confronted by what appear to be extraordinary circumstances or compelling personal convictions. Comey had several other lawful options available to him to advocate for the appointment of a Special Counsel, which he told us was his goal in making the disclosure,” the report says.

“What was not permitted was the unauthorized disclosure of sensitive investigative information, obtained during the course of FBI employment, in order to achieve a personally desired outcome,” it adds.

After Comey’s firing, the FBI determined that four of the memos contained information classified at either the “secret” or “confidential” level. The memo about the Flynn interaction that Comey sent to Richman did not contain any classified information, the report said.

Comey said he considered his memos to be personal rather than government documents, and that it never would’ve occurred to him to give them back to the FBI after he was fired. The inspector general’s office disagreed, citing policy that FBI employees must give up all documents containing FBI information once they leave the bureau.

FBI agents retrieved four of Comey’s memos from his house weeks after he was fired.

The office of Inspector General Michael Horowitz also is investigating the FBI’s Russia investigation and expected to wrap up soon.

Last year, the watchdog office concluded that former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe had misrepresented under oath his involvement in a news media disclosure, and referred him for possible prosecution. That matter remains open with the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Washington.

Florida Braces for Hurricane Dorian

MIAMI — Florida residents picked the shelves clean of bottled water and lined up at gas stations Thursday as an increasingly menacing-looking Hurricane Dorian threatened to broadside the state over Labor Day weekend.

Leaving lighter-than-expected damage in its wake in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, the second hurricane of the 2019 season swirled toward the U.S., with forecasters warning it will draw energy from the warm, open waters as it closes in.

The National Hurricane Center said the Category 1 storm is expected to strengthen into a potentially catastrophic Category 4 with winds of 130 mph (209 kph) and slam into the U.S. on Monday somewhere between the Florida Keys and southern Georgia — a 500-mile stretch that reflected the high degree of uncertainty this far out.

Related Articles

Puerto Rico Braces for Rain, Power Outages as Dorian Nears

by

“If it makes landfall as a Category 3 or 4 hurricane, that’s a big deal,” said University of Miami hurricane researcher Brian McNoldy. “A lot of people are going to be affected. A lot of insurance claims.”

President Donald Trump canceled his weekend trip to Poland and declared Florida is “going to be totally ready.”

With the storm’s track still unclear, no immediate mass evacuations were ordered.

Along Florida’s east coast, local governments began distributing sandbags, shoppers rushed to stock up on food, plywood and other emergency supplies at supermarkets and hardware stores, and motorists topped off their tanks and filled gasoline cans. Some fuel shortages were reported in the Cape Canaveral area.

Josefine Larrauri, a retired translator, went to a Publix supermarket in Miami only to find empty shelves in the water section and store employees unsure of when more cases would arrive.

“I feel helpless because the whole coast is threatened,” she said. “What’s the use of going all the way to Georgia if it can land there?”

Tiffany Miranda of Miami Springs waited well over 30 minutes in line at BJ’s Wholesale Club in Hialeah to buy hurricane supplies. Some 50 vehicles were bumper-to-bumper, waiting to fill up at the store’s 12 gas pumps.

“You never know with these hurricanes. It could be good, it could be bad. You just have to be prepared,” she said.

As of Thursday evening, Dorian was centered about 330 miles (535 kilometers) east of the Bahamas, its winds blowing at 85 mph (140 kph) as it moved northwest at 13 mph (20 kph).

It is expected to pick up steam as it pushes out into warm waters with favorable winds, the University of Miami’s McNoldy said, adding: “Starting tomorrow, it really has no obstacles left in its way.”

The National Hurricane Center’s projected track had the storm blowing ashore midway along the Florida peninsula, southeast of Orlando and well north of Miami or Fort Lauderdale. But because of the difficulty of predicting its course this far ahead, the “cone of uncertainty” covered nearly the entire state.

Forecasters said coastal areas of the Southeast could get 5 to 10 inches of rain, with 15 inches in some places, triggering life-threatening flash floods.

Also imperiled were the Bahamas, with Dorian’s expected track running just to the north of Great Abaco and Grand Bahama islands.

Jeff Byard, an associate administrator at the Federal Emergency Management Agency, warned that Dorian is likely to “create a lot of havoc with infrastructure, power and roads,” but gave assurances FEMA is prepared to handle it, even though the Trump administration is shifting hundreds of millions of dollars from FEMA and other agencies to deal with immigration at the Mexican border.

“This is going to be a big storm. We’re prepared for a big response,” Byard said.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis declared a state of emergency, clearing the way to bring in more fuel and call out the National Guard if necessary, and Georgia’s governor followed suit.

Royal Caribbean, Carnival and Norwegian began rerouting their cruise ships. Major airlines began allowing travelers to change their reservations without a fee.

At the Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, NASA decided to move indoors the mobile launch platform for its new mega rocket under development.

A Rolling Stones concert Saturday at the Hard Rock Stadium near Miami was moved up to Friday night.

The hurricane season typically peaks between mid-August and late October. One of the most powerful storms ever to hit the U.S. was on Labor Day 1935. The unnamed Category 5 hurricane crashed ashore along Florida’s Gulf Coast on Sept. 2. It was blamed for over 400 deaths.

Dorian rolled through the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico as a Category 1 hurricane on Wednesday.

The initial blow did not appear to be as bad as expected in Puerto Rico, which is still recovering from the devastation wrought by Hurricane Maria two years ago. Blue tarps cover some 30,000 homes, and the electrical grid is in fragile condition.

But the tail end of the storm unleashed heavy flooding along the eastern and southern coasts of Puerto Rico. Cars, homes and gravestones in the coastal town of Humacao became halfway submerged after a river burst its banks.

Police said an 80-year-old man in the town of Bayamón died after he fell trying to climb to his roof to clear it of debris ahead of the storm.

Dorian caused an island-wide blackout in St. Thomas and St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands and scattered outages in St. Croix, government spokesman Richard Motta said.

No serious damage was reported in the British Virgin Islands, where Gov. Augustus Jaspert said crews were already clearing roads and inspecting infrastructure by late Wednesday afternoon.

Back in Florida, Mark and Gisa Emeterio enjoyed a peaceful afternoon sunbathing and wading in the ocean at Vero Beach. The newly retired couple from Sacramento, California, wanted to relax after spending the morning shuttering their home.

Mark, a retired pipe layer, and Gina, a retired state employee, planned to wait it out the storm with local friends more experienced with hurricanes.

“We got each other,” Mark Emeterio said. “So we’re good.”

“I told him, ‘Whatever happens, hold my hand,'” his wife joked.

___

Associated Press writers Seth Borenstein and Michael Balsamo in Washington; Danica Coto in San Juan, Puerto Rico; Marcia Dunn in Cape Canaveral, Florida; Marcus Lim in Miami; Ellis Rua in Vero Beach and Mike Schneider in Orlando, Florida, contributed to this report.

Trump Declares New Space Command Key to American Defense

WASHINGTON — Declaring space crucial to the nation’s defense, President Donald Trump said Thursday the Pentagon has established U.S. Space Command to preserve American dominance on “the ultimate high ground.”

“This is a landmark day,” Trump said in a Rose Garden ceremony, “one that recognizes the centrality of space to America’s national security and defense.”

He said Space Command, headed by a four-star Air Force general, will “ensure that America’s superiority in space is never questioned and never threatened.”

But there’s still no Space Force.

Space Force, which has become a reliable applause line for Trump at his campaign rallies, has yet to win final approval by Congress.

The renewed focus on space as a military domain reflects concern about the vulnerability of U.S. satellites, both military and commercial, that are critical to U.S. interests and are potentially susceptible to disruption by Chinese and Russian anti-satellite weapons.

The role of the new Space Command is to conduct operations such as enabling satellite-based navigation and communications for troops and commanders in the field and providing warning of missile launches abroad. That is different from a Space Force, which would be a distinct military service like the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps and Coast Guard.

Congress has inched toward approving the creation of a Space Force despite skepticism from some lawmakers of both parties. The House and Senate bills differ on some points, and an effort to reconcile the two will begin after Congress returns from its August recess.

When Jim Mattis was defense secretary, the Pentagon was hesitant to embrace the idea of a Space Force. Trump’s first Pentagon chief initially saw it as potentially redundant and not the best use of defense dollars. His successor, Mark Esper, has cast himself as a strong supporter of creating both a Space Force and a command dedicated to space.

“To ensure the protection of America’s interests in space, we must apply the necessary focus, energy and resources to the task, and that is exactly what Space Command will do,” Esper said Wednesday.

“As a unified combatant command, the United States Space Command is the next crucial step toward the creation of an independent Space Force as an additional armed service,” he added.

Kaitlyn Johnson, a defense space expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said she considers it likely, but not certain, that Congress will approve a Space Force in the 2020 defense bill.

The people in Space Force would be assigned to missions directed by Space Command, just as members of the Army and other services are assigned to an organization like U.S. Strategic Command.

Like other branches of the military, Space Force would be headed by a four-star general who would have a seat at the table with the other Joint Chiefs of Staff. Trump wanted Space Force to be “separate but equal” to the other services, but instead it is expected to be made part of the Air Force, similar to how the Marine Corps is part of the Navy.

Reestablishing Space Command has been a less politically contentious matter. There is a consensus that it is the most straightforward step among those proposed to shore up space defenses.

“This step puts us on a path to maintain a competitive advantage,” Gen. Joseph Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said at a National Space Council meeting last week. He also endorsed creating Space Force, saying it would make a “profound difference.”

Initially, the opening of Space Command will have little practical effect on how the military handles its space responsibilities. Air Force Space Command currently deals with more than three-quarters of the military space mission, and it is expected to only gradually hand off those duties to the new command.

Johnson, the CSIS expert, said the attention to space during the Trump administration has led some to exaggerate the scope of change reflected in the moves to create Space Command and Space Force.

These moves, she said, “seem very flashy and fun” but are not.

“It’s really just a reorganization of functions that are already happening within the military,” she said.

Air Force Gen. John “Jay” Raymond will serve as the first commander of U.S. Space Command. He currently heads Air Force Space Command.

At his Senate confirmation hearing June 4, Raymond made the case for changing the way the military approaches its space mission.

“Unfortunately, our adversaries have had a front row seat into our many successes and have seen the advantages that they provide us,” he said. “And to be honest, they don’t like what they see. And they’re rapidly developing capabilities to negate our use of space and to negate the advantage that space provides.”

Trump’s Asylum Policies Could Get People Killed

In an April roundtable on U.S.-Mexico border security, President Trump called asylum seekers and their stories a “scam.” “They’re not afraid of anything … and they say ‘I fear for my life,’ ” he said, according to The Daily Beast. “It’s a scam, it’s a hoax.” Trump also claimed, according to CNN, that “the system is full,” and there is no more room for immigrants.

As a new report from BuzzFeed shows, this means victims of domestic violence are in danger of being deported back to their abusers. Kenia, a 38-year-old mother of two from El Salvador (she gave only her first name to BuzzFeed), was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in May. Following the arrest, she applied for a U visa, which provides undocumented immigrants and their immediate families who are the victims of crimes with a path to citizenship if they work with law enforcement.

As North Texas public radio station KERA reported earlier this week, the U visa is even seen as a source of hope for undocumented residents who were victims of the Aug. 3 mass shooting in El Paso. Immigration attorney Pamela Muñoz told the station that “It is kind of implied that there will be people who are eligible for this.”

Even with likely eligibility, however, the path to actually getting the U visa is difficult, and made more so by the Trump administration.

Kenia has been in the United States since 2004, at which time she sought asylum. She’s worked at a restaurant and taken care of children with disabilities. While she did receive a notice to appear in immigration court in 2004, it had no date or time, so she didn’t show up. The result was a deportation order, one which wasn’t enforced until ICE agents came to her home this May, a full 15 years later. She’s now in an immigration detention center, and her U visa was denied on Aug. 27.

Kenia was terrified, telling BuzzFeed, “What’s the point of a U visa if it doesn’t help people like me,” and, “I just want a chance. … I’m afraid I’ll be killed if I’m sent back to El Salvador.”

Prior to the Trump administration’s immigration policies, Kenia’s deportation order would likely have been paused while her visa application was processed, her attorney, Eileen Blessinger, explained to BuzzFeed.

Unfortunately, according to documents BuzzFeed reviewed, an ICE field office director told Kenia that “in light of ICE’s mission, current ICE policies and enforcement priorities,” there is “no compelling reason” to stop the deportation.

Kenia is not the only one suffering the consequences of the current polices on U visas.

In Lancaster County, Pa., a family is suing government officials, according to local CBS station WHP-TV (CBS-21). The daughter, now 20, who declined to give her name, was brought to the United States at six years old. She was the victim of sexual assault at nine years old, and, as a crime victim willing to cooperate with law enforcement, she’s a candidate for the U visa. Her lawyers, David Freeman and Barley Snyder, told CBS-21 that suing the government was a last resort before she’s made to leave the country.

“If you are a victim of a qualifying crime, they’re very serious crimes, such as sexual assault, you have to cooperate with law enforcement or a prosecutor’s office,” Freeman explained, “and then you have to have the prosecutor or law enforcement agency certify that you’ve cooperated.”

Despite applying three years ago, the Pennsylvania woman’s application remains in limbo, and the threat of deportation hangs over her and her family’s lives. She tells CBS-21, “Our life is literally on pause.”

Attorney Freeman says he wants to know if there is a waiting list that could—at least temporarily—halt deportation.

According to the motion to dismiss, which CBS-21 obtained, U.S. attorneys are arguing that the application delay does not constitute a valid claim, the current wait isn’t out of the ordinary, and the woman will not be receiving special treatment.

In Blessinger’s experience, other of her clients who have applied for U visas have often successfully halted their deportations. They did so following an ICE consultation with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (the agency that grants visas) to confirm that they were good candidates.

Now, as BuzzFeed writer Adolfo Flores explains, “a fact sheet issued this month by ICE on revised policies stated that the agency is no longer required to request a determination from USCIS that they had met the basic requirements for a U visa.”

The fact sheet says that previous consultations with USCIS were a “simple confirmation that the petition was filed correctly and was not a substantive review of the petition. … As the number of U visa petitions submitted increased, this process became burdensome on both agencies and often did not impact ICE’s decisions.” Now that ICE isn’t required to check in with USCIS, the agency has more power in determining whether an applicant gets deported or is granted a stay.

“This is going to affect the entire judicial system, with fewer people coming forward to report crimes and more criminals remaining free,” Blessinger says. “Kenia’s story is not just about Kenia. It’s about how this is going to affect people in general.”

Insurance Companies Are Creating an Economy of Extortion

Editor’s note: This story was originally published by ProPublica.

On June 24, the mayor and council of Lake City, Florida, gathered in an emergency session to decide how to resolve a ransomware attack that had locked the city’s computer files for the preceding fortnight. Following the Pledge of Allegiance, Mayor Stephen Witt led an invocation. “Our heavenly father,” Witt said, “we ask for your guidance today, that we do what’s best for our city and our community.”

Witt and the council members also sought guidance from City Manager Joseph Helfenberger. He recommended that the city allow its cyber insurer, Beazley, an underwriter at Lloyd’s of London, to pay the ransom of 42 bitcoin, then worth about $460,000. Lake City, which was covered for ransomware under its cyber-insurance policy, would only be responsible for a $10,000 deductible. In exchange for the ransom, the hacker would provide a key to unlock the files.

“If this process works, it would save the city substantially in both time and money,” Helfenberger told them.

Without asking questions or deliberating, the mayor and the council unanimously approved paying the ransom. The six-figure payment, one of several that U.S. cities have handed over to hackers in recent months to retrieve files, made national headlines.

Related Articles

Who Exactly Is the Economy 'Booming' For?

by

Left unmentioned in Helfenberger’s briefing was that the city’s IT staff, together with an outside vendor, had been pursuing an alternative approach. Since the attack, they had been attempting to recover backup files that were deleted during the incident. On Beazley’s recommendation, the city chose to pay the ransom because the cost of a prolonged recovery from backups would have exceeded its $1 million coverage limit, and because it wanted to resume normal services as quickly as possible.

“Our insurance company made [the decision] for us,” city spokesman Michael Lee, a sergeant in the Lake City Police Department, said. “At the end of the day, it really boils down to a business decision on the insurance side of things: them looking at how much is it going to cost to fix it ourselves and how much is it going to cost to pay the ransom.”

The mayor, Witt, said in an interview that he was aware of the efforts to recover backup files but preferred to have the insurer pay the ransom because it was less expensive for the city. “We pay a $10,000 deductible, and we get back to business, hopefully,” he said. “Or we go, ‘No, we’re not going to do that,’ then we spend money we don’t have to just get back up and running. And so to me, it wasn’t a pleasant decision, but it was the only decision.”

Ransomware is proliferating across America, disabling computer systems of corporations, city governments, schools and police departments. This month, attackers seeking millions of dollars encrypted the files of 22 Texas municipalities. Overlooked in the ransomware spree is the role of an industry that is both fueling and benefiting from it: insurance. In recent years, cyber insurance sold by domestic and foreign companies has grown into an estimated $7 billion to $8 billion-a-year market in the U.S. alone, according to Fred Eslami, an associate director at AM Best, a credit rating agency that focuses on the insurance industry. While insurers do not release information about ransom payments, ProPublica has found that they often accommodate attackers’ demands, even when alternatives such as saved backup files may be available.

The FBI and security researchers say paying ransoms contributes to the profitability and spread of cybercrime and in some cases may ultimately be funding terrorist regimes. But for insurers, it makes financial sense, industry insiders said. It holds down claim costs by avoiding expenses such as covering lost revenue from snarled services and ongoing fees for consultants aiding in data recovery. And, by rewarding hackers, it encourages more ransomware attacks, which in turn frighten more businesses and government agencies into buying policies.

“The onus isn’t on the insurance company to stop the criminal, that’s not their mission. Their objective is to help you get back to business. But it does beg the question, when you pay out to these criminals, what happens in the future?” said Loretta Worters, spokeswoman for the Insurance Information Institute, a nonprofit industry group based in New York. Attackers “see the deep pockets. You’ve got the insurance industry that’s going to pay out, this is great.”

A spokesperson for Lloyd’s, which underwrites about one-third of the global cyber-insurance market, said that coverage is designed to mitigate losses and protect against future attacks, and that victims decide whether to pay ransoms. “Coverage is likely to include, in the event of an attack, access to experts who will help repair the damage caused by any cyberattack and ensure any weaknesses in a company’s cyberprotection are eliminated,” the spokesperson said. “A decision whether to pay a ransom will fall to the company or individual that has been attacked.” Beazley declined comment.

Fabian Wosar, chief technology officer for anti-virus provider Emsisoft, said he recently consulted for one U.S. corporation that was attacked by ransomware. After it was determined that restoring files from backups would take weeks, the company’s insurer pressured it to pay the ransom, he said. The insurer wanted to avoid having to reimburse the victim for revenues lost as a result of service interruptions during recovery of backup files, as its coverage required, Wosar said. The company agreed to have the insurer pay the approximately $100,000 ransom. But the decryptor obtained from the attacker in return didn’t work properly and Wosar was called in to fix it, which he did. He declined to identify the client and the insurer, which also covered his services.

“Paying the ransom was a lot cheaper for the insurer,” he said. “Cyber insurance is what’s keeping ransomware alive today. It’s a perverted relationship. They will pay anything, as long as it is cheaper than the loss of revenue they have to cover otherwise.”

Worters, the industry spokeswoman, said ransom payments aren’t the only example of insurers saving money by enriching criminals. For instance, the companies may pay fraudulent claims — for example, from a policyholder who sets a car on fire to collect auto insurance — when it’s cheaper than pursuing criminal charges. “You don’t want to perpetuate people committing fraud,” she said. “But there are some times, quite honestly, when companies say: ’This fraud is not a ton of money. We are better off paying this.’ … It’s much like the ransomware, where you’re paying all these experts and lawyers, and it becomes this huge thing.”

Insurers approve or recommend paying a ransom when doing so is likely to minimize costs by restoring operations quickly, regulators said. As in Lake City, recovering files from backups can be arduous and time-consuming, potentially leaving insurers on the hook for costs ranging from employee overtime to crisis management public relations efforts, they said.

“They’re going to look at their overall claim and dollar exposure and try to minimize their losses,” said Eric Nordman, a former director of the regulatory services division of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, or NAIC, the organization of state insurance regulators. “If it’s more expeditious to pay the ransom and get the key to unlock it, then that’s what they’ll do.”

As insurance companies have approved six- and seven-figure ransom payments over the past year, criminals’ demands have climbed. The average ransom payment among clients of Coveware, a Connecticut firm that specializes in ransomware cases, is about $36,000, according to its quarterly report released in July, up sixfold from last October. Josh Zelonis, a principal analyst for the Massachusetts-based research company Forrester, said the increase in payments by cyber insurers has correlated with a resurgence in ransomware after it had started to fall out of favor in the criminal world about two years ago.

One cybersecurity company executive said his firm has been told by the FBI that hackers are specifically extorting American companies that they know have cyber insurance. After one small insurer highlighted the names of some of its cyber policyholders on its website, three of them were attacked by ransomware, Wosar said. Hackers could also identify insured targets from public filings; the Securities and Exchange Commission suggests that public companies consider reporting “insurance coverage relating to cybersecurity incidents.”

Even when the attackers don’t know that insurers are footing the bill, the repeated capitulations to their demands give them confidence to ask for ever-higher sums, said Thomas Hofmann, vice president of intelligence at Flashpoint, a cyber-risk intelligence firm that works with ransomware victims.

Ransom demands used to be “a lot less,” said Worters, the industry spokeswoman. But if hackers think they can get more, “they’re going to ask for more. So that’s what’s happening. … That’s certainly a concern.”

In the past year, dozens of public entities in the U.S. have been paralyzed by ransomware. Many have paid the ransoms, either from their own funds or through insurance, but others have refused on the grounds that it’s immoral to reward criminals. Rather than pay a $76,000 ransom in May, the city of Baltimore — which did not have cyber insurance — sacrificed more than $5.3 million to date in recovery expenses, a spokesman for the mayor said this month. Similarly, Atlanta, which did have a cyber policy, spurned a $51,000 ransom demand last year and has spent about $8.5 million responding to the attack and recovering files, a spokesman said this month. Spurred by those and other cities, the U.S. Conference of Mayors adopted a resolution this summer not to pay ransoms.

Still, many public agencies are delighted to have their insurers cover ransoms, especially when the ransomware has also encrypted backup files. Johannesburg-Lewiston Area Schools, a school district in Michigan, faced that predicament after being attacked in October. Beazley, the insurer handling the claim, helped the district conduct a cost-benefit analysis, which found that paying a ransom was preferable to rebuilding the systems from scratch, said Superintendent Kathleen Xenakis-Makowski.

“They sat down with our technology director and said, ‘This is what’s affected, and this is what it would take to re-create,’” said Xenakis-Makowski, who has since spoken at conferences for school officials about the importance of having cyber insurance. She said the district did not discuss the ransom decision publicly at the time in part to avoid a prolonged debate over the ethics of paying. “There’s just certain things you have to do to make things work,” she said.

Ransomware is one of the most common cybercrimes in the world. Although it is often cast as a foreign problem, because hacks tend to originate from countries such as Russia and Iran, ProPublica has found that American industries have fostered its proliferation. We reported in May on two ransomware data recovery firms that purported to use their own technology to disable ransomware but in reality often just paid the attackers. One of the firms, Proven Data, of Elmsford, New York, tells victims on its website that insurance is likely to cover the cost of ransomware recovery.

Lloyd’s of London, the world’s largest specialty insurance market, said it pioneered the first cyber liability policy in 1999. Today, it offers cyber coverage through 74 syndicates — formed by one or more Lloyd’s members such as Beazley joining together — that provide capital and accept and spread risk. Eighty percent of the cyber insurance written at Lloyd’s is for entities based in the U.S. The Lloyd’s market is famous for insuring complex, high-risk and unusual exposures, such as climate-change consequences, Arctic explorers and Bruce Springsteen’s voice.

Many insurers were initially reluctant to cover cyber disasters, in part because of the lack of reliable actuarial data. When they protect customers against traditional risks such as fires, floods and auto accidents, they price policies based on authoritative information from national and industry sources. But, as Lloyd’s noted in a 2017 report, “there are no equivalent sources for cyber-risk,” and the data used to set premiums is collected from the internet. Such publicly available data is likely to underestimate the potential financial impact of ransomware for an insurer. According to a report by global consulting firm PwC, both insurers and victimized companies are reluctant to disclose breaches because of concerns over loss of competitive advantage or reputational damage.

Despite the uncertainty over pricing, dozens of carriers eventually followed Lloyd’s in embracing cyber coverage. Other lines of insurance are expected to shrink in the coming decades, said Nordman, the former regulator. Self-driving cars, for example, are expected to lead to significantly fewer car accidents and a corresponding drop in premiums, according to estimates. Insurers are seeking new areas of opportunity, and “cyber is one of the small number of lines that is actually growing,” Nordman said.

Driven partly by the spread of ransomware, the cyber insurance market has grown rapidly. Between 2015 and 2017, total U.S. cyber premiums written by insurers that reported to the NAIC doubled to an estimated $3.1 billion, according to the most recent data available.

Cyber policies have been more profitable for insurers than other lines of insurance. The loss ratio for U.S. cyber policies was about 35% in 2018, according to a report by Aon, a London-based professional services firm. In other words, for every dollar in premiums collected from policyholders, insurers paid out roughly 35 cents in claims. That compares to a loss ratio of about 62% across all property and casualty insurance, according to data compiled by the NAIC of insurers that report to them. Besides ransomware, cyber insurance frequently covers costs for claims related to data breaches, identity theft and electronic financial scams.

During the underwriting process, insurers typically inquire about a prospective policyholder’s cyber security, such as the strength of its firewall or the viability of its backup files, Nordman said. If they believe the organization’s defenses are inadequate, they might decline to write a policy or charge more for it, he said. North Dakota Insurance Commissioner Jon Godfread, chairman of the NAIC’s innovation and technology task force, said some insurers suggest prospective policyholders hire outside firms to conduct “cyber audits” as a “risk mitigation tool” aimed to prevent attacks — and claims — by strengthening security.

“Ultimately, you’re going to see that prevention of the ransomware attack is likely going to come from the insurance carrier side,” Godfread said. “If they can prevent it, they don’t have to pay out a claim, it’s better for everybody.”

Not all cyber insurance policies cover ransom payments. After a ransomware attack on Jackson County, Georgia, last March, the county billed insurance for credit monitoring services and an attorney but had to pay the ransom of about $400,000, County Manager Kevin Poe said. Other victims have struggled to get insurers to pay cyber-related claims. Food company Mondelez International and pharmaceutical company Merck sued insurers last year in state courts after the carriers refused to reimburse costs associated with damage from NotPetya malware. The insurers cited “hostile or warlike action” or “act of war” exclusions because the malware was linked to the Russian military. The cases are pending.

The proliferation of cyber insurers willing to accommodate ransom demands has fostered an industry of data recovery and incident response firms that insurers hire to investigate attacks and negotiate with and pay hackers. This year, two FBI officials who recently retired from the bureau opened an incident response firm in Connecticut. The firm, The Aggeris Group, says on its website that it offers “an expedient response by providing cyber extortion negotiation services and support recovery from a ransomware attack.”

Ramarcus Baylor, a principal consultant for The Crypsis Group, a Virginia incident response firm, said he recently worked with two companies hit by ransomware. Although both clients had backup systems, insurers promised to cover the six-figure ransom payments rather than spend several days assessing whether the backups were working. Losing money every day the systems were down, the clients accepted the offer, he said.

Crypsis CEO Bret Padres said his company gets many of its clients from insurance referrals. There’s “really good money in ransomware” for the cyberattacker, recovery experts and insurers, he said. Routine ransom payments have created a “vicious circle,” he said. “It’s a hard cycle to break because everyone involved profits: We do, the insurance carriers do, the attackers do.”

Chris Loehr, executive vice president of Texas-based Solis Security, said there are “a lot of times” when backups are available but clients still pay ransoms. Everyone from the victim to the insurer wants the ransom paid and systems restored as fast as possible, Loehr said.

“They figure out that it’s going to take a month to restore from the cloud, and so even though they have the data backed up,” paying a ransom to obtain a decryption key is faster, he said.

“Let’s get it negotiated very quickly, let’s just get the keys, and get the customer decrypted to minimize business interruption loss,” he continued. “It makes the client happy, it makes the attorneys happy, it makes the insurance happy.”

If clients morally oppose ransom payments, Loehr said, he reminds them where their financial interests lie, and of the high stakes for their businesses and employees. “I’ll ask, ‘The situation you’re in, how long can you go on like this?’” he said. “They’ll say, ‘Well, not for long.’ Insurance is only going to cover you for up to X amount of dollars, which gets burned up fast.”

“I know it sucks having to pay off assholes, but that’s what you gotta do,” he said. “And they’re like, ‘Yeah, OK, let’s get it done.’ You gotta kind of take charge and tell them, ‘This is the way it’s going to be or you’re dead in the water.’”

Lloyd’s-backed CFC, a specialist insurance provider based in London, uses Solis for some of its U.S. clients hit by ransomware. Graeme Newman, chief innovation officer at CFC, said “we work relentlessly” to help victims improve their backup security. “Our primary objective is always to get our clients back up and running as quickly as possible,” he said. “We would never recommend that our clients pay ransoms. This would only ever be a very final course of action, and any decision to do so would be taken by our clients, not us as an insurance company.”

As ransomware has burgeoned, the incident response division of Solis has “taken off like a rocket,” Loehr said. Loehr’s need for a reliable way to pay ransoms, which typically are transacted in digital currencies such as Bitcoin, spawned Sentinel Crypto, a Florida-based money services business managed by his friend, Wesley Spencer. Sentinel’s business is paying ransoms on behalf of clients whose insurers reimburse them, Loehr and Spencer said.

New York-based Flashpoint also pays ransoms for insurance companies. Hofmann, the vice president, said insurers typically give policyholders a toll-free number to dial as soon as they realize they’ve been hit. The number connects to a lawyer who provides a list of incident response firms and other contractors. Insurers tightly control expenses, approving or denying coverage for the recovery efforts advised by the vendors they suggest.

“Carriers are absolutely involved in the decision making,” Hofmann said. On both sides of the attack, “insurance is going to transform this entire market,” he said.

On June 10, Lake City government officials noticed they couldn’t make calls or send emails. IT staff then discovered encrypted files on the city’s servers and disconnected the infected servers from the internet. The city soon learned it was struck by Ryuk ransomware. Over the past year, unknown attackers using the Ryuk strain have besieged small municipalities and technology and logistics companies, demanding ransoms up to $5 million, according to the FBI.

Shortly after realizing it had been attacked, Lake City contacted the Florida League of Cities, which provides insurance for more than 550 public entities in the state. Beazley is the league’s reinsurer for cyber coverage, and they share the risk. The league declined to comment.

Initially, the city had hoped to restore its systems without paying a ransom. IT staff was “plugging along” and had taken server drives to a local vendor who’d had “moderate success at getting the stuff off of it,” Lee said. However, the process was slow and more challenging than anticipated, he said.

As the local technicians worked on the backups, Beazley requested a sample encrypted file and the ransom note so its approved vendor, Coveware, could open negotiations with the hackers, said Steve Roberts, Lake City’s director of risk management. The initial ransom demand was 86 bitcoin, or about $700,000 at the time, Coveware CEO Bill Siegel said. “Beazley was not happy with it — it was way too high,” Roberts said. “So [Coveware] started negotiations with the perps and got it down to the 42 bitcoin. Insurance stood by with the final negotiation amount, waiting for our decision.”

Lee said Lake City may have been able to achieve a “majority recovery” of its files without paying the ransom, but it probably would have cost “three times as much money trying to get there.” The city fired its IT director, Brian Hawkins, in the midst of the recovery efforts. Hawkins, who is suing the city, said in an interview posted online by his new employer that he was made “the scapegoat” for the city’s unpreparedness. The “recovery process on the files was taking a long time” and “the lengthy process was a major factor in paying the ransom,” he said in the interview.

On June 25, the day after the council meeting, the city said in a press release that while its backup recovery efforts “were initially successful, many systems were determined to be unrecoverable.” Lake City fronted the ransom amount to Coveware, which converted the money to bitcoin, paid the attackers and received a fee for its services. The Florida League of Cities reimbursed the city, Roberts said.

Lee acknowledged that paying ransoms spurs more ransomware attacks. But as cyber insurance becomes ubiquitous, he said, he trusts the industry’s judgment.

“The insurer is the one who is going to get hit with most of this if it continues,” he said. “And if they’re the ones deciding it’s still better to pay out, knowing that means they’re more likely to have to do it again — if they still find that it’s the financially correct decision — it’s kind of hard to argue with them because they know the cost-benefit of that. I have a hard time saying it’s the right decision, but maybe it makes sense with a certain perspective.”

ProPublica research reporter Doris Burke contributed to this story.

The Death of Arms Control

A deadly accident in northern Russia earlier this month caused the U.S. arms control community to stand up and take notice. The Russians claim they were testing “isotopic sources of fuel on a liquid propulsion unit,” and that only after the test was completed did the engine explode. There was a spike in radiation levels detected in the city of Severodvinsk, roughly 18 miles away, shortly after the accident. Seven people were killed as a result of the explosion, including at least two who died of acute radiation poisoning. Scores of others were exposed to radioactive materials, and subsequently decontaminated and placed under observation. Within days, the Russians declared that all radiation readings in and around the accident site were at normal levels.

Many Western experts believe that the Russians were testing a nuclear-powered cruise missile, the 9M730 “Burevestnik”—known in the West by its NATO designation, the SSC-X-9 “Skyfall”—and that a miniature nuclear reactor these experts believe was used to power the missile exploded. Other experts, including me, question this conclusion. But a recent report by Roshydromet, the Russian agency responsible for sampling air quality, showed the presence of four distinct isoptopes in the atmosphere after the accident that are uniquely sourced to the fission of uranium 235, strongly suggesting that a reactor of some sort was, in fact, involved (mitigating against this conclusion is the fact that no iodine 131 was detected; iodine 131 is the most prevalent isotope produced by the fission of uranium 235, and its absence would be highly unlikely in the event of any reactor explosion).

The bottom line, however, is that no one outside the Russians responsible for the failed test know exactly what system was being tested, why it was being tested, how it was being tested, and why that test failed. The Russian government has refused to provide any details about the test. “When it comes to activities of a military nature,” Russian President Vladimir Putin said in a press conference a few days after the accident, “there are certain restrictions on access to information. This is work in the military field, work on promising weapons systems. We are not hiding this,” he said, adding, “We must think of our own security.”

Related Articles

Donald Trump's Nuclear Doctrine Threatens Human Life on Earth

by

The Most Dangerous Weapon Ever Rolls Off the Nuclear Assembly Line

by

Others were thinking about their own security as well.

“Something obviously has gone badly wrong here,” U.S. national security adviser John Bolton said after the accident. Bolton observed that Russia is seeking to “modernize their nuclear arsenal to build new kinds of delivery vehicles, hypersonic glide vehicles, hypersonic cruise missiles,” noting that “dealing with this capability … remains a real challenge for the United States and its allies.” The U.S. and Russia are currently discussing the extension of the New START treaty on strategic arms reduction, scheduled to expire in early 2021. “If there is going to be an extension of the New START,” U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper said, “then we need to make sure that we include all these new weapons that Russia is pursuing.”

But this is problematic—the new Russian weapons under development are directly linked to the decision by the George W. Bush administration in 2002 to withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty, a 1972 agreement that limited the number and types of ABM weapons the U.S. and then-Soviet Union could deploy, thereby increasing the likelihood that any full-scale missile attack would succeed in reaching its target. By creating the inevitability of mutual nuclear annihilation (a practice referred to as “mutually assured destruction,” or MAD), both the U.S. and Soviet strategic nuclear forces served as a deterrent against one another.