Chris Hedges's Blog, page 159

September 8, 2019

Netanyahu’s Miscalculations About Iran Will Cost Him Dearly

This piece originally appeared on Informed Comment.

The Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu is one of the world players who pushed Trump to breach the 2015 treaty with Iran. Trump then slapped the severest economic sanctions on Iran ever imposed on any country in the absence of war. Trump went around the world menacing other countries into ceasing to buy Iranian petroleum and threatening billions in fines against any company anywhere in the world that invested in or traded with Iran.

Related Articles

The Pro-Israel Extremist Behind Trump's Economic War on Iran

by

How the U.S. and Iran Got to This Tense Moment

by Medea Benjamin

Israel Is Captive to Its 'Destructive Process'

by Chris Hedges

This economic and financial blockade was supposed to bring Iran to its knees, push it out of Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, and perhaps (it was hoped by some in Trump’s circles) even pave the way to the overthrow of the Islamic Republic of Iran in favor of the Marxist-Islamic People’s Jihadis (Mohahedin-e Khalq or MEK, which is alleged to have ties to Israeli intelligence).

Instead, Netanyahu and Trump have pushed Iran straight into the arms of China which is investing $400 billion in the country and which is now taking most of Iran’s oil exports. China seems intent on integrating Iran into its economy even more robustly than it had proposed with Pakistan.

In foreign policy, China supports the al-Assad government in Syria and so is a silent partner with Iran and Russia in this regard. Hawks in Washington had hoped to see al-Assad overthrown in favor of Sunni fundamentalists who might join a US-Saudi-Israel axis (this was always a pipe dream and some of the actual Sunni fundamentalists affiliated to al-Qaeda).

China has investments in Iraqi petroleum and was extremely alarmed by so-called Islamic State group or ISIL, which it was afraid would infect the 20 million Chinese Muslims with radicalism. It is therefore happy enough to have a strong Shiite anti-ISIL government in Baghdad allied with equally anti-ISIL Shiite Iran.

In short, China’s close embrace of Iran requires no significant change in Iranian foreign policy, and indeed, promises to strengthen Iran in such a way as to enable it to continue its present policies in the Middle East.

Nor is China interested in the least in Iran’s human rights record or how democratic its government is.

Let’s just imagine what might have happened if the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the 2015 Iran deal, had remained in place and the US had upheld its treaty obligations.

France, Germany and Italy were chomping at the bit to get into Iran. Some 100 French CEOs went to Tehran seeking markets. Iran was on the verge of being inundated with Western consumer goods. Iran was being normalized in diplomacy. It was planning to buy Boeing planes and Airbuses.

Closer integration of Iran into the European and American economy would have added to the country’s prosperity, and would have undercut regime hard liners. Such a dense network of economic ties has political and diplomatic implications. Iran would have had to moderate some of its policies in order to maintain good relations with its new trading partners. European leaders would have pressured it on human rights and democracy, and its hostility to Israel. Moreover, any backsliding on its commitments to keep its enrichment program limited to civilian production of electricity would also have threatened those trade ties.

This scenario would have had substantial benefits for Israel, even if it deprived the Israeli leadership of a pretext for or piece of misdirection for their brutal colonization of Palestine (the West Bank and Gaza).

Trump had his own reasons for canceling the 2015 Iran deal, in which Iran had given up 80% of its civilian nuclear enrichment program and was forestalled from militarizing the program by UN inspections. But it seems clear from the reporting of Ronen Bergman and Mark Mazetti at the New York Times Netanyahu has spent a decade and a half lobbying for the United States to strike Iran. Of course, so too have the Saudis, and the warmonger wing of the Republican Party is full of Genghis Khans dreaming of towers of skulls. Netanyahu and the Israeli political establishment, however, have much more weight in Washington than do the Saudis, and Netanyahu has openly campaigned as a sort of American Republican, working his constituency among evangelicals and deploying the powerful American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), which donates big money to US politicians, and mobilizing the full spectrum of what John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt termed “the Israel Lobby.”

To the extent that Netanyahu played a role here, his plot has backfired monumentally. If the China deal goes through, Iran is much strengthened and its hard liners are entirely unleashed. The positioning of Chinese security forces in Iran will make it increasingly risky for other countries such as Israel or the US to strike Iran, lest they come into conflict with nuclear-armed China.

Netanyahu may have been hoping that Trump would strike Iran for him, but that clearly is not going to happen– Trump’s reading of his base is that they are tired of seeing American blood and treasure squandered in the Middle East. Indeed, Trump may eventually actually hold talks with Iran, an eventuality that clearly scares Netanyahu half to death.

Netanyahu could have had an Iran under the JCPOA that integrated increasingly with the West and became open to Western pressure. He blew it.

The Only True Invaders of Planet Earth

He crossed the border without permission or, as far as I could tell, documentation of any sort. I’m speaking about Donald Trump’s uninvited, unasked-for invasion of my personal space. He’s there daily, often hourly, whether I like it or not, and I don’t have a Department of Homeland Security to separate him from his children, throw them all in degrading versions of prison — without even basic toiletries or edible food or clean water — and then send him back to whatever shithole tower he came from in the first place. (For that, I have to depend on the American people in 2020 and what still passes, however dubiously, for a democracy.)

And yes, the president has been an invader par excellence in these years — not a word I’d use idly, unlike so many among us these days. Think of the spreading use of “invasion,” particularly on the political right, in this season of the most invasive president ever to occupy the Oval Office, as a version of America’s wars coming home. Think of it, linguistically, as the equivalent of those menacing cops on the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, back in 2014, togged out to look like an occupying army with Pentagon surplus equipment, some of it directly off America’s distant battlefields.

Not that many are likely to think of what’s happening, invasion-wise, in such terms these days.

Admittedly, like so much else, the worst of what’s happening didn’t start with Donald Trump. “Invasion” and “invaders” first entered right-wing vocabularies as a description of immigration across our southern border in the late 1980s and 1990s. In his 1992 attempt to win the Republican presidential nomination, for instance, Patrick Buchanan used the phrase “illegal invasion” in relation to Hispanic immigrants. In the process, he highlighted them as a national threat in a fashion that would become familiar indeed in recent years.

Today, however, from White House tweets to the screed published by Patrick Crusius, the 21-year-old white nationalist who killed 22 people, including eight Mexican citizens, in an El Paso Walmart, the use of “invasion,” or in his case “the Hispanic invasion of Texas,” has become part of the American way of life (and death). Meanwhile, the language itself has, in some more general sense, has continued to be weaponized.

Of course, when you speak of invasions these days, as President Trump has done repeatedly — he used the word seven times in less than a minute at a recent rally and, by early August, his reelection campaign had posted more than 2,000 Facebook ads with invasion in them — you’re speaking of only one type of invasion. It’s a metaphorical-cum-political one in which they invade us (even though they may not know that they’re doing it). Hundreds of thousands of them have been crossing our southern border, mostly on their own individual initiative. In some cases, however, they have made it to the border in “caravans.” Just about every one of them, however, is arriving not with mayhem in mind, but in search of some version of safety and, if not well-being, at least better-being in this country.

That’s not the way the White House, most Republicans, or right-wing media figures are describing things, however. As the president put it at a White House Workforce advisory meeting in March:

“You see what’s going on at the border… We are doing an amazing job considering it’s really an onslaught very much. I call it ‘invasion.’ They always get upset when I say ‘an invasion.’ But it really is somewhat of an invasion.”

Or as Tucker Carlson said on Fox News, “We are so overwhelmed by this — it literally is an invasion of people crossing into Texas”; or as Jeanine Pirro plaintively asked on Fox & Friends, “Will anyone in power do anything to protect America this time, or will our leaders sit passively back while the invasion continues?” The examples of such statements are legion.

The True Invaders of Planet Earth

Here’s the strange thing, though: in this century, there has been only one true invader on planet Earth and it’s not those desperate Central Americans fleeing poverty, drugs, violence, and hunger (for significant aspects of which the U.S. is actually to blame).

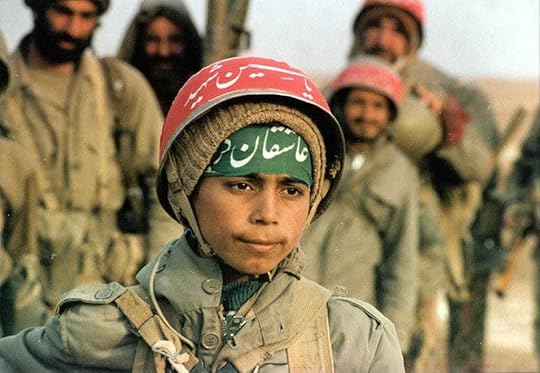

The real invader in this world of ours happens to be the United States of America. I’m speaking, of course, about the only nation in this century whose armed forces have, in the (once) normal sense of the term, invaded two other countries. In October 2001, the administration of President George W. Bush responded invasively to a nightmarish double act of terrorism here. An extremist Islamist outfit that called itself al-Qaeda and was led by a rich Saudi (whom Washington had, in the previous century, been allied with in a war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan) proved responsible. Instead of organizing an international policing operation to deal with bin Laden and crew, however, President Bush and his top officials launched what they quickly dubbed the Global War on Terror, or GWOT. While theoretically aimed at up to 60 countries across the planet, it began with the bombing and invasion of Afghanistan. Osama bin Laden and some of his crew were indeed there at the time, but the invasion’s aim was, above all, to overthrow another group of extreme Islamists, the Taliban, who controlled most of that land.

So, Washington began a war that has yet to end. Then, in the spring of 2003, the same set of officials did just what a number of them had been eager to do on September 12, 2001: they unleashed American forces in an invasion of Iraq meant to take down autocrat Saddam Hussein (a former U.S. ally who had nothing to do with 9/11 or al-Qaeda). In fact, we now know that, within hours of a hijacked jet crashing into the Pentagon, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was already thinking about just such an invasion. (“Go massive. Sweep it all up. Things related and not,” he reportedly said that day, while urging his aides to come up with a plan to invade Iraq.)

So American troops took Kabul and Baghdad, the capitals of both countries, where the Bush administration set up governments of its choice. In neither would the ensuing occupations and wars or the tumultuous events that evolved from them ever truly end. In both regions, terrorism is significantly more widespread now than it was then. In the intervening years, millions of the inhabitants of those two lands and others swept up in that American war on terror were displaced from their homes and hundreds of thousands killed or wounded as chaos, terror, and war spread across the Greater Middle East (later compounded by the “Arab Spring”) and finally deep into Africa.

In addition, the U.S. military — equally unsuccessfully, equally long-lastingly, equally usefully when it came to the spread of terrorism and of failed or failing states — took action in Libya, Somalia, Yemen (largely but not only via the Saudis), and even Syria. While those might have been considered interventions, not invasions, they were each unbelievably more invasive than anything the domestic right-wing is now calling an invasion on our southern border. In 2016, in Syria, for instance, the U.S. Air Force and its allies dropped an estimated 20,000 bombs on the “capital” of the Islamic State, Raqqa, a modest-sized provincial city. In doing so, with the help of artillery and of ISIS suicide bombers, they turned it into rubble. In a similar fashion from Mosul to Fallujah, major Iraqi cities were rubblized. All in all, it’s been quite a record of invasion, intervention, and destruction.

In addition, the U.S. military — equally unsuccessfully, equally long-lastingly, equally usefully when it came to the spread of terrorism and of failed or failing states — took action in Libya, Somalia, Yemen (largely but not only via the Saudis), and even Syria. While those might have been considered interventions, not invasions, they were each unbelievably more invasive than anything the domestic right-wing is now calling an invasion on our southern border. In 2016, in Syria, for instance, the U.S. Air Force and its allies dropped an estimated 20,000 bombs on the “capital” of the Islamic State, Raqqa, a modest-sized provincial city. In doing so, with the help of artillery and of ISIS suicide bombers, they turned it into rubble. In a similar fashion from Mosul to Fallujah, major Iraqi cities were rubblized. All in all, it’s been quite a record of invasion, intervention, and destruction.

Nor should we forget that, in those and other countries (including Pakistan), the U.S. dispatched Hellfire missile-armed drones to carry out “targeted” strikes that, once upon a time, would have been called “assassinations.” In addition, in 2017 alone, contingents of the still-growing elite Special Operations forces, now about 70,000 personnel, had been dispatched, in war and peace, to 149 countries, according to investigative journalist Nick Turse. Meanwhile, American military garrisons by the hundreds continued to dot the globe in a historically unprecedented fashion and have regularly been used in these years to facilitate those very invasions, interventions, and assassinations.

In addition, in this period the CIA set up “black sites” in a number of countries where prisoners, sometimes literally kidnapped off the streets of major cities (sometimes captured in the backlands of the planet), were for years subjected to unbearable cruelty and torture. U.S. Navy ships were similarly used as black sites. And all of this was just part of an offshore Bermuda Triangle of injustice set up by Washington, whose beating heart was a now notorious (and still open) prison in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

Since 2001, the U.S. has succeeded in squandering staggering amounts of taxpayer dollars unsettling a vast swath of the planet, killing startling numbers of people who didn’t deserve to die, driving yet more of them from their homes, and so helping to set in motion the very crisis of migrants and refugees that has roiled both Europe and the United States ever since. The three top countries sending unwanted asylum seekers to Europe have been Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, all deeply embroiled in the cauldron of the American war on terror. (Meanwhile, of course, we live in a country whose president, having called for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” during his election campaign in 2015, has done his best to follow through on just such a Muslim ban.)

And by the way, those original invasions and interventions were all surrounded by glorious explanations about the bringing of “democracy” to and the “liberation” of various societies, explanations no less bogus than those offered by the El Paso killer to explain his slaughter.

Still in the Land of the Metaphorically Invaded

Invaders, intruders, disrupters? You’ve got to be kidding, at least if you’re talking about undocumented immigrants from south of our border (even with the bogus claims that there were “terrorists” among them). When it comes to invasions, we should be chanting “USA! USA!” Perhaps, in fact, you could think of this country, its leadership, its military, and its war on terror as a version of the El Paso killer raised to a global scale. In this century at least, we have been the true invaders and disrupters on planet Earth (with the Russians in Crimea and the Ukraine coming in a distant second).

And how have Americans dealt with the real invaders of this world? It’s a reasonable question, even if seldom asked in a country where “invasion” is now a matter of almost obsessional discussion and debate. True, on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, a striking number of Americans had the urge not to go to war. The streets of major cities and small towns filled with protesters demanding that the Bush administration not do what it was obviously going to do anyway. When the invasion and occupation happened, it should have quickly been clear that it would be a destructive disaster. The initial shock-and-awe air campaign to “decapitate” Saddam Hussein’s regime, for example, managed not to touch a single key Iraqi official but, according to Human Rights Watch, killed “dozens of civilians.” In this way, the stage was set for so much of what would follow.

When the bad news (Mission Unaccomplished!) started coming in, however, those antiwar protestors disappeared from the streets of our country, never to return. In the years that followed, Americans generally ignored the harm the U.S. was doing across significant parts of the globe and went on with their lives. It did, however, become a tic of the times to “thank” the troops who had done the invading for their “service.”

In the meantime, much of what had transpired globally in that war on terror was simply forgotten (or never noted in the first place). That’s why when, in mid-August, an ISIS suicide bomber blew himself up at a wedding party in Kabul killing at least 63 people, the New York Times could report that “weddings, the celebration of union, had largely remained the exception” to an Afghan sense of risk-taking in public. And that would be a statement few Americans would blink at — as if no weddings had ever been destroyed in that country. Few here would remember the six weddings U.S. air power had obliterated in Afghanistan (as well as at least one each in Iraq and Yemen). The first of them, in December 2001, would kill about 100 revelers in a village in Eastern Afghanistan and that would just be the beginning of the nightmare to come. This was something I documented at TomDispatch years ago, but it’s generally not even in the memory bank here.

In 2016, of course, Americans elected a man who had riled up what soon be called his “base” by launching a presidential campaign on the fear of Mexican “rapists” coming to this country and the necessity of building a “big, fat, beautiful wall” to turn them away. From scratch, in other words, his focus was on stopping an “invasion” of this land. By August 2015, he was already using that term in his tweets.

So, under Donald Trump, as that word and the fears that went with it spread, we became the invaded and they the invaders. In other words, the world as it was (and largely remains) was somehow turned on its head. As a result, we all now live in the land of the metaphorically invaded and of El Paso killers who, in these years, have headed, armed with military-style weaponry, for places ranging from synagogues to garlic festivals to stop various “invaders” in their tracks. Meanwhile, the president and a bipartisan crew of politicians in Washington continued to pour ever more money into the U.S. military (and into little else, except the pockets of the 1%).

As for me, in all those years before Donald Trump launched his presidential campaign, I had never watched his reality TV shows. Though I lived in New York City, I had never walked into Trump Tower. I had never, in other words, invaded his space, no matter how metaphorically. So, with invasions in the air, I continue to wonder why, every day in every way, he invades mine. And speaking of invasions, he and his crew in Washington are now getting ready to invade the space not just of people like me, but of endangered species of every sort.

Of course, the president who feeds off those “invaders” from the south doesn’t recognize me as a species of anything. For him, the only endangered species on this planet may be oil, coal, and natural gas companies.

Believe me, you’re in his world, not mine, and welcome to it!

Gazan’s Death Abroad Shines Light on Middle-Class Exodus

GAZA CITY, Gaza Strip — With a family of five, a two-story home and a pharmacy, Tamer al-Sultan had a life many in the besieged and impoverished Gaza Strip would envy, but he still felt trapped.

Fed up with the heavy-handed rule of Hamas, al-Sultan braved a treacherous journey in hopes of starting a new life in the West — only to die along the way. His death has drawn attention to the growing exodus of middle-class Gazans who can no longer bear to live in the isolated coastal territory.

It has also struck a nerve among many Palestinians because he appears to have fled persecution by Hamas, rather than the territory’s dire economic conditions following a 12-year blockade by Israel and Egypt, imposed when the Islamic militant group seized power.

Al-Sultan had vented about Hamas’ rule on social media and joined rare protests against a Hamas tax hike in March that were quickly and violently suppressed. Amin Abed, a friend who was arrested with al-Sultan on three occasions over the protests, said they were doused with cold water and beaten with plastic whips.

So al-Sultan left, following in the footsteps of thousands of other educated, middle-class Palestinians. The exodus has gathered pace in recent years, raising fears that Gaza could lose its doctors, lawyers, teachers and thinkers, putting the Palestinians’ dream of establishing a prosperous independent state in even greater peril.

He had planned to go to Belgium, where he had relatives, and bring his family after gaining refugee status. But his journey ended in Bosnia, where he died last month at the age of 38.

The exact cause of his death is not known. A purported hospital report from Bosnia circulated online says he had blood cancer, but the document has not been authenticated, and his family says he was in good health prior to the journey.

“He left Gaza because of the oppression,” his brother, Ramadan al-Sultan, said at the family’s home in the northern town of Beit Lahiya. Mourners at the funeral last month marched with the yellow flags of the rival Fatah movement and chanted “Out, Out!” when Hamas supporters showed up.

Palestinians have long seen their steadfastness in remaining on the land as their best hope for one day gaining independence from Israeli military rule, and both the Western-backed Palestinian Authority and its rival Hamas are opposed to emigration. Hamas cleric Salem Salama recently issued a fatwa, or religious edict, against emigration, saying “those who leave our homeland with the intention of not coming back deserve the wrath of God.”

There is no official count of the number of Palestinians who have emigrated from Gaza. Israel does not control Rafah, the main exit point, and Hamas and Egypt do not track such figures.

The U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs says 104,600 Palestinians left Gaza in 2018 and 2019 and 75,783 returned. But it’s not clear whether all of the roughly 30,000 net departures are emigrants. Many Gazans leave for extended periods to study or work abroad, with the intention of returning.

“It’s certain that thousands have taken advantage of the opportunity to exit Gaza in the hopes of finding a better future, away from the poverty and feeling of hopelessness at home,” says Gisha, an Israeli rights group that advocates for Palestinian freedom of movement.

There is no official resettlement program, so many Palestinians resort to informal routes. Al-Sultan took one of the more popular ones.

He left through the Rafah crossing, which Egypt has kept open on a regular basis since May 2018 after years of largely restricting travel to humanitarian cases. From there, al-Sultan went to Turkey, which welcomes Palestinian visitors. Then he took a rickety boat to Greece and worked his way up through the Balkans.

The International Organization for Migration says 1,177 Palestinians have crossed from Turkey to Greece by sea since the start of the year, the fourth most crossings by nationality. Over the past year, at least six Gazans have died on that route, including al-Sultan, according to local media reports.

While al-Sultan left to escape Hamas, many others have fled poverty and isolation. The blockade, along with Palestinian infighting , has devastated the local economy. More than half of Gaza’s labor force is unemployed and some 80 percent rely on food assistance. Daily power cuts last for several hours, and the tap water is undrinkable.

Mohammed Nassir graduated with a degree in information technology three years ago and opened a computer shop in his hometown of Beit Hanoun, but soon went out of business. He found a part-time job at an advertising company, but the firm shut down two months later.

Last week he waited outside the Rafah crossing, hoping his name would be called so he could board one of the three buses Egypt allows in every day.

“There is nothing left for us here,” he said. “No work, no present, no future, and above all, no hope.”

His uncle lives in Germany and is working on getting him a visa to travel there. Until then, he intends to sojourn in Egypt.

“If things don’t work out, I don’t know what I will do. But any place would be better than Gaza,” he said.

At the other end of the long and uncertain journey is Karim Nashwan, a prominent lawyer who left Gaza with his family in 2016 after his children graduated from university and now lives outside Brussels. He says he wishes he had left even earlier.

“My children decided to leave, and I agreed with them. They have no jobs, no safety, no future and no life in Gaza,” he said in a phone interview.

His wife and five children risked everything to travel the Turkey-Greece route before eventually flying onward to Belgium. He was able to join them later by traveling to Belgium legally under a family reunification program.

“The children learned the language and are integrating in the society,” he said. “We lost hope in Gaza.”

The Madness of James Mattis

Last week, in a well-received Wall Street Journal op-ed, former Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis delivered a critique of Donald Trump that was as hollow as it was self-righteous. Explaining his decision to resign from the administration, the retired Marine general known as “Mad Dog” eagerly declared himself “apolitical,” peppering his narrative with cheerful vignettes about his much beloved grunts. “We all know that we’re better than our current politics,” he observed solemnly. “Tribalism must not be allowed to destroy our experiment.”

Yet absent from this personal reflection, which has earned bipartisan adulation, was any kind of out-of-the-box thinking and, more disturbingly, anything resembling a mea culpa—either for his role in the Trump administration or his complicity in America’s failing forever wars in the greater Middle East. For a military man, much less a four-star general, this is a cardinal sin. What’s worse, no one in the mainstream media appears willing to challenge the worldview presented in his essay, concurrent interviews and forthcoming book.

Related Articles

U.N. Report Finds U.S. Likely Guilty of War Crimes in Yemen

by Ilana Novick

The Pentagon Belongs to Silicon Valley Now

by

Liberals' Dangerous Love Affair With the U.S. Military

by Maj. Danny Sjursen

This was disconcerting if unsurprising. In Trump’s America, reflexive hatred for the president has led many in the media to foolishly pin their political hopes on generals like Mattis, leaders of the only public institution the people still trust. Even purportedly liberal journalists like MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, who was once critical of U.S. militarism, have reversed course, defending engagements in Syria and Afghanistan seemingly because the president has expressed interest in winding them down. The fallacy that Mattis and other generals were the voice of reason in the Trump White House, the so-called “adults in the room,” has precluded any serious critique of their actual strategy and advice.

The wildly unpopular, if not forbidden-to-be-uttered, truth is that Mattis, while an admittedly decorated Marine and a military strategist, was an abject failure. Despite being hailed as a “warrior monk,” he was and remains a conventional interventionist figure—prisoner to the tired old militarist ideas of the necessity for U.S. military forward deployment, counterinsurgency in Afghanistan, and the perpetual need to balance or “contain” Russia and China. His career-long defense of America’s post-9/11 engagements should be the first sentence of his obituary.

None of these egregious errors in judgment have derailed Mattis’ career, of course. Can-do attitudes and compulsive optimism form the bedrock of today’s military culture, if not American society at large. Indeed, it was the general’s all-too-familiar view of the “War on Terror” that likely endeared him to successive promotion boards. As he notes in his own op-ed, “Institutions get the behaviors they reward.”

But Mattis and his entire generation of military leadership ultimately did a great disservice to their subordinates and the American people once they reached four-star rank. When given an (often absurd) mission by administration officials—be they Bush neoconservatives or Obama liberals—these generals and admirals offered “how” rather than “if” responses. Cultishly eager to please, they failed to tell their frequently ill-informed superiors that perhaps a proposed conflict couldn’t be won, at least with the resources available or at an acceptable human cost. Instead, Mattis, David Petraeus and their ilk debated whether counter-terror, advise-and-assist, or counterinsurgency was the best method to achieve an ill-defined “victory.” They effectively substituted high-level tactics for strategy.

Thanks to Mattis and company, Trump’s purported desire to withdraw from fruitless Middle Eastern wars has been stifled, the result being business as usual for the military-industrial-complex and national security state. And why not? Since resigning his post, Mattis has burst through the “revolving door” of the arms industry, reclaiming his seat on the board of the fifth largest defense contractor, General Dynamics. Albert Einstein famously (and perhaps apocryphally) said, “The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” He might just as easily have been describing the career of James Mattis, who has been proven wrong again and again and again, from Iraq to Afghanistan to Syria.

Perhaps the only thing more celebrated than Mattis’ ostensible intellectualism is his supposed integrity. Yet his record as defense secretary throws that into question as well. Lest we forget, the general only decided to resign when Trump dared suggest a modest troop withdrawal from an 18-year war in Afghanistan and a speedy end to a highly risky, and ill-defined, mission in Syria.

This man of principle apparently had no ethical or philosophical compunctions about his department’s support and complicity in the Saudi terror bombing and starvation campaign aimed at the people of Yemen. This ongoing war has killed tens of thousands of civilians, starved at least 85,000 children to death, unleashed the world’s worst cholera epidemic, and generated millions of refugees. Mattis offered not one word of public criticism as his boss sold Saudi Arabia bombs that were all too often dropped on the heads of Yemeni civilians.

Even after revelations that Saudi intelligence agents had murdered and dismembered The Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Mattis and Secretary of State Pompeo appeared before Congress to defend the Saudis and argue for continued U.S. support in its war on Yemen. That conflict alone should have prompted him to resign, but it did not.

Mattis, a supposed “warrior monk,” and cerebral strategist above the passions and viciousness of battle, also holds a tarnished legacy from his time commanding the siege and assault of Fallujah, Iraq, in late 2004. According to a well-documented report from the Center for Investigative Reporting, his Marines played fast and loose with their firepower, killing enough civilians to fill a soccer stadium. A year later, he reportedly used his status as a two-star general to “wipe away criminal charges” for Marines accused of massacring 24 Iraqi civilians in the village of Haditha.

His actions in Iraq earned Mattis the nickname “Mad Dog,” of which he is now reportedly embarrassed. The former defense secretary seems always to have been a disturbingly gleeful killer, and once famously said of fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan, that “Actually it’s quite fun to fight them, you know. It’s a hell of a hoot. It’s fun to shoot some people.” These aren’t the words of a reluctant warrior, even if they do demonstrate surprising candor about the dark side of war rarely uttered in polite company. It sounds instead like the irresponsible comments of a senior general who was busy playing sergeant.

Mattis ends his op-ed with a brief tale about the proverbial boys in the trenches. During the (predictably failed) assault on Marjah, Afghanistan, in 2010, he recounts asking an exhausted, sweaty Marine how he was doing and receiving a gleeful reply of “Living the dream, sir!” In my experience as a soldier, this kind of quip is usually meant sarcastically, but no matter. The exchange energized Mattis, and no one in the corporate press dared examine the real essence of the story he imparted.

By refusing to question the Marjah operation, or Obama’s Afghan “surge” in general, Mattis betrayed the very ground-pounders by whom he was so inspired. A more honorable figure, a true adult in the room, would have asked what we were doing there in the first place.

September 7, 2019

Russia and Ukraine Trade Prisoners, Each Flies 35 to Freedom

MOSCOW—Russia and Ukraine conducted a major prisoner exchange that freed 35 people detained in each country and flew them to the other, a deal that could help advance Russia-Ukraine relations and end five years of fighting in Ukraine’s east.

The trade involved some of the highest-profile prisoners caught up in a bitter standoff between Ukraine and Russia.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy greeted the freed prisoners as they stepped down from the airplane that had brought them from Moscow to Kyiv’s Boryspil airport. Relatives waiting on the tarmac surged forward to hug their loved ones.

Most of the ex-detainees appeared to be in good physical condition, although one struggled down the steps on crutches and another was held by the arms as he slowly navigated the steps.

Related Articles

Manufacturing War With Russia

by Chris Hedges

Among those Russia returned was Ukrainian film director Oleg Sentsov, whose conviction for preparing terrorist attacks was strongly denounced abroad, and 24 Ukrainian sailors taken with a ship the Russian navy seized last year.

“Hell has ended; everyone is alive and that is the main thing,” Vyacheslav Zinchenko, 30, one of the released sailors, said.

The prisoners released by Ukraine included Volodymyr Tsemakh, who commanded a separatist rebel air defense unit in the area of eastern Ukraine where a Malaysian airliner was shot down in 2014, killing all 298 people aboard.

Dozens of lawmakers urged Ukraine’s president not to make Tsemakh one of their country’s 35 traded prisoners.

Critics saw freeing Tsemakh as an act of submissiveness to Russia, but the exchange “allows Zelenskiy to fulfill one of his main pre-election promises,” Ukrainian analyst Vadim Karasev told The Associated Press

Zelenskiy, who was elected in a landslide in April, has promised new initiatives to resolve the war in eastern Ukraine between government troops and the separatist rebels.

The exchange of prisoners also raises hope in Russia for the reduction of European sanctions imposed because of its role in the conflict, Karasev said. Russia also is under sanctions for its annexation of Crimea in 2014, shortly before the separatist conflict in the east began, but that dispute is unlikely to be resolved.

At Moscow’s Vnukovo airport, the released prisoners remained on the plane for about 15 minutes for unknown reasons. When they came off, many toting baggage, a bus drove them to a medical facility for examination.

Russia said it would release a full list of its citizens freed by Ukraine but had not done so by Saturday night. .

The 24 sailors in the swap were seized after Russian ships fired on two Ukrainian vessels on Nov. 25 in the Kerch Strait, located between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov next to Russia-annexed Crimea.

Another passenger on the plane from Moscow was Nikolai Karpyuk, who was imprisoned in 2016 after he was convicted of killing Russians in Chechnya in the 1990s.

“Russia was not able to break me even though they tried hard to do this,” Karpyuk said in Kyiv.

Kirill Vyshinsky, head of Russian state news agency RIA-Novosti’s Ukraine branch, also had a seat. Vyshinsky had been jailed since 2018 on treason charges.

He thanked Harlem Desir, the media freedom representative for the Organization for Security and Cooperation In Europe, for calling for his release.

The exchange comes amid renewed hope that a solution can be found to the fighting in Ukraine’s east that has killed 13,000 people since 2014. A congratulatory tweet from U.S. President Donald Trump called the trade “good news.”

“Russia and Ukraine just swapped large numbers of prisoners. Very good news, perhaps a first giant step to peace,” Trump’s tweet said. “Congratulations to both countries!”

However, reaching a peace agreement faces many obstacles, such as determining the final territorial status of rebel-held areas. Russia insists it has not supported the rebels and the fighting is Ukraine’s internal affair.

A Russian Foreign Ministry statement welcoming the exchange touched on those difficulties, calling the war an “intra-Ukraine conflict.”

“Obviously, the habit of blaming Russia for all the troubles of Ukraine should remain in the past,” the ministry statement said.

The prospect of progress nevertheless appeared to rise last month with the announcement of a planned summit of the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, France and Germany – the four countries with representatives in the long-dormant “Normandy format,” a group seeking to end the conflict.

“We have made the first step. It was very complicated. Further, we will come closer to the return of our (war) prisoners,” Zelenskiy said of the prisoner exchange.

In July, a tentative agreement for the release of 69 Ukrainian prisoners and 208 held in Ukraine was reached by the Trilateral Contact Group of Russia, Ukraine and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe; negotiations on fulfilling it continue.

Konstantin Kosachev, head of the foreign relations committee in the Russian parliament’s upper house, said the exchange represented a move “in the direction of crossing from confrontation to dialogue, and one can only thank those thanks to whose strength this became possible.”

___

Yuras Karmanau in Minsk, Belarus, contributed to this story .

Iran Raises Nuclear Stakes, Threatens Higher Enrichment

TEHRAN, Iran—Iran on Saturday said it now uses arrays of advanced centrifuges prohibited by its 2015 nuclear deal and can enrich uranium “much more beyond” current levels to weapons-grade material, taking a third step away from the accord while warning Europe has little time to offer it new terms.

While insisting Iran doesn’t seek a nuclear weapon, the comments by Behrouz Kamalvandi of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran threatened pushing uranium enrichment far beyond levels ever reached in the country. Prior to the atomic deal, Iran only reached up to 20%, which itself still is only a short technical step away from weapons-grade levels of 90%.

Related Articles

We Are Teetering on the Brink of War With Iran

by

The Pro-Israel Extremist Behind Trump's Economic War on Iran

by

Scapegoating Iran

by Chris Hedges

The move threatened to push tensions between Iran and the U.S. even higher more than a year after President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew America from the nuclear deal and imposed sanctions now crushing Iran’s economy. Mysterious attacks on oil tankers near the Strait of Hormuz, Iran shooting down a U.S. military surveillance drone and other incidents across the wider Middle East followed Trump’s decision.

“So far, Iran has showed patience before the U.S. pressures and Europeans’ indifference,” said Qassem Babaei, a 33-year-old electrician in Tehran. “Now they should wait and see how Iran achieves its goals.”

Iran separately acknowledged Saturday it had seized another ship and detained 12 Filipino crewmembers, while satellite images suggested an Iranian oil tanker once held by Gibraltar was now off the coast of Syria despite Tehran promising its oil wouldn’t go there.

Speaking to journalists while flanked by advanced centrifuges, Kamalvandi said Iran has begun using an array of 20 IR-6 centrifuges and another 20 of IR-4 centrifuges. An IR-6 can produce enriched uranium 10 times as fast as an IR-1, Iranian officials say, while an IR-4 produces five times as fast.

The nuclear deal limited Iran to using only 5,060 first-generation IR-1 centrifuges to enrich uranium by rapidly spinning uranium hexafluoride gas. By starting up these advanced centrifuges, Iran further cuts into the one year that experts estimate Tehran would need to have enough material for building a nuclear weapon if it chose to pursue one.

“Under current circumstances, the Islamic Republic of Iran is capable of increasing its enriched uranium stockpile as well as its enrichment levels and that is not just limited to 20 percent,” Kamalvandi said. “We are capable inside the country to increase the enrichment much more beyond that.”

Iran plans to have two cascades, one with 164 advanced IR-2M centrifuges and another with 164 IR-5 centrifuges, running in two months as well, Kamalvandi said. A cascade is a group of centrifuges working together to more quickly enrich uranium.

Iran has already increased its enrichment up to 4.5%, above the 3.67% allowed under the deal, as well as gone beyond its 300-kilogram limit for low-enriched uranium.

While Kamalvandi stressed that “the Islamic Republic is not after the bomb,” he warned that Iran was running out of ways to stay in the accord.

“If Europeans want to make any decision, they should do it soon,” he said. France had floated a proposed $15 billion line of credit to allow Iran to sell its oil abroad despite U.S. sanctions. Another trade mechanism proposed by Europe called INSTEX also has faced difficulty.

Kamalvandi also said Iran would allow U.N. inspectors to continue to monitor sites in the country. A top official from the U.N.’s International Atomic Energy Agency was expected to meet with Iranian officials in Tehran on Sunday.

The IAEA said Saturday it was aware of Iran’s announcement and “agency inspectors are on the ground in Iran and they will report any relevant activities to IAEA headquarters in Vienna.” It did not elaborate.

In Paris, U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper said Iran’s announcement wasn’t a surprise.

“The Iranians are going to pursue what the Iranians have always intended to pursue,” Esper said at a news conference with his French counterpart, Florence Parly.

For his part, Trump has said he remains open for direct talks with Iran. A surprise visit by Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif to the Group of Seven summit in France last month raised the possibility of direct talks between Trump and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, perhaps at this month’s United Nations General Assembly in New York, though officials in Tehran later seemed to dismiss the idea.

Meanwhile Saturday, Iranian state TV said the tugboat and its 12 crewmembers were seized on suspicion of smuggling diesel fuel near the Strait of Hormuz. The report did not elaborate. In Manila, the Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs said it was checking details of the reported seizure.

Also Saturday, satellite images showed a once-detained Iranian oil tanker pursued by the U.S. appears to be off the coast of Syria, where Tehran reportedly promised the vessel would not go when authorities in Gibraltar agreed to release it several weeks ago.

Images obtained by The Associated Press from Maxar Technologies appeared to show the Adrian Darya-1, formerly known as the Grace-1, some 2 nautical miles (3.7 kilometers) off Syria’s coast.

Iranian and Syrian officials have not acknowledged the vessel’s presence there. Authorities in Tehran earlier said the 2.1 million barrels of crude oil onboard had been sold to an unnamed buyer. That oil is worth about $130 million on the global market, but it remains unclear who would buy the oil as they’d face the threat of U.S. sanctions.

The new images matched a black-and-white image earlier tweeted by John Bolton, the U.S. national security adviser.

“Anyone who said the Adrian Darya-1 wasn’t headed to #Syria is in denial,” Bolton tweeted. “We can talk, but #Iran’s not getting any sanctions relief until it stops lying and spreading terror!”

U.S. prosecutors in federal court allege the Adrian Darya’s owner is Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, which answers only to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. On Wednesday, the U.S. imposed new sanctions on an oil shipping network it alleged had ties to the Guard and offered up to $15 million for anyone with information that disrupts its paramilitary operations.

___

Gambrell reported from Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Associated Press writers Robert Burns in Paris, David Rising in Berlin and Jim Gomez in Manila, Philippines, contributed to this report.

Bahamas ‘Hour of Darkness’: 43 Dead, With Toll to Rise

ABACO, Bahamas—The hurricane death toll is rising in the Bahamas, in what its leader calls “this hour of darkness.”

Search and rescue teams were still trying to reach some Bahamian communities isolated by floodwaters and debris Saturday after Hurricane Dorian struck the northern part of the archipelago last Sunday. At least 43 people died.

Several hundred people, many of them Haitian immigrants, waited at Abaco island’s Marsh Harbour in hopes of leaving the disaster zone on vessels arriving with aid. Bahamian security forces were organizing evacuations on a landing craft. Other boats, including yachts and other private craft, were also helping to evacuate people.

Avery Parotti, a 19-year-old bartender, and partner Stephen Chidles, a 26-year-old gas station attendant had been waiting at the port since 1 a.m. During the hurricane, waves lifted a yacht that smashed against a cement wall, which in turn collapsed on their home and destroyed it.

“There’s nothing left here. There are no jobs,” said Parotti, who hopes to start a new life in the United States, where she has relatives.

Dorval Darlier, a Haitian diplomat who had come from the Bahamian capital of Nassau, shouted in Creole, telling the crowd that sick people along with women and children should be evacuated before men.

Prime Minister Hubert Minnis said late Friday that 35 people were known dead on Abaco and eight on Grand Bahama island.

“We acknowledge that there are many missing and that the number of deaths is expected to significantly increase,” he said. “This is one of the stark realities we are facing in this hour of darkness.”

On Saturday, U.S. President Donald Trump tweeted that Minnis had told him that there would have been “many more casualties” without U.S. help. Trump credited the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the U.S. Coast Guard and the “brave people of the Bahamas.”

The U.S. Coast Guard has evacuated some people from devastated areas by helicopter. The United Nations, the British Royal Navy, American Airlines and Royal Caribbean and other organizations have mobilized to send in food, water, generators, roof tarps, diapers, flashlights and other supplies.

Marvin Dames, security minister in the Bahamas, said authorities were striving to reach everyone, but the crews can’t just bulldoze their way through fallen trees and other rubble because there might be bodies not yet recovered.

“We have been through this before, but not at this level of devastation,” Dames said.

Dames said the runway at the airport on Grand Bahama island had been cleared and was ready for flights. Authorities also said that all ports had been reopened on that island and Abaco, both of which were devastated by the Category 5 storm.

On Grand Bahama, a long line formed at a cruise ship that had docked to distribute food and water. Among those waiting was Wellisy Taylor, a housewife.

“What we have to do as Bahamians, we have to band together. If your brother needs sugar, you’re going to have to give him sugar. If you need cream, they’ll have to give you cream,” she said. “That’s how I grew up. That’s the Bahamas that I know.”

September 6, 2019

Hemp Legalization Has Made It Harder to Prosecute People for Marijuana

After passage of the 2018 federal farm bill legalized hemp production, states scrambled to pass their own laws legalizing hemp and CBD. But in doing so, they may have inadvertently signed a death warrant for the enforcement of marijuana prohibition.

Forty-seven states have now legalized hemp, but only 11 have legalized marijuana. The other 36 may be in for a refresher course in the law of unintended consequences.

Hemp and recreational marijuana both come from the same plant species, cannabis sativa. The only thing that differentiates hemp and weed is the level of the intoxicating cannabinoid, THC. Under federal law and most state laws, hemp is defined as cannabis sativa containing less than 0.3 percent THC. In those states that have yet to legalize marijuana, hemp is thus legal, but THC-bearing weed is not.

Related Articles

Using Marijuana to Quash the Opioid Crisis

by

The Cheapest Way to Save the Planet Grows Like a Weed

by Ellen Brown

But what police and prosecutors in those states are finding is that they can’t tell the difference between the two. Their field drug tests can detect cannabis sativa, but they can’t detect THC levels. Likewise, police drug dogs can sniff out cannabis, but can’t distinguish between hemp and marijuana.

And if they can’t prove the substance in question is illegal marijuana and not legal hemp, they don’t have a case. Some state crime labs can test for THC levels, but those labs are busy, the tests are costly, and even police and prosecutors are questioning whether it’s worth tying up resources to try to nail someone for possessing a joint or two.

In Ohio, after the Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BCI) analyzed the state’s new hemp law, it sent an August 1 advisory to prosecutors warning that traditional tests could not differentiate between hemp and marijuana and that the agency was months away from “validating instrumental methods to meet this new legal requirement.”

In the meantime, the BCI suggested, prosecutors could turn to private, accredited laboratories, but it also recommended that they “suspend any identification” by traditional tests and not prosecute “any cannabis-related items […] prior to the crime laboratory you work with being capable to perform the necessary quantitative analysis.”

That prompted Columbus City Attorney Zach Klein to announce a week later that he will no longer prosecute misdemeanor marijuana possession cases and that he was dropping all current and pending cases, too.

“The prosecution of marijuana possession charges would require drug testing that distinguishes hemp from marijuana,” Klein said in a written statement. “Without this drug-testing capability, the city attorney’s office is not able to prove misdemeanor marijuana possession beyond a reasonable doubt” because “our current drug-testing technology is not able to differentiate.”

The prosecutor in surrounding Franklin County, Ron O’Brien, who would handle felony pot possession cases, said his office would probably put those cases on hold unless they involved very large quantities. That’s because even though there are labs in the state capable of measuring THC levels, they still have to be accredited to do so, a bureaucratic procedure that could take months, with a backlog of marijuana cases accumulating in the meantime.

And those tests cost money. That’s why state Attorney General Dave Yost (R) announced in mid-August that the state was creating a special grant program to help local police agencies pay for testing that can differentiate between hemp and marijuana. It allocates $50,000 to help with testing until state-budgeted funding to upgrade state crime labs kicks in next year.

“Just because the law changed, it doesn’t mean the bad guys get a ‘get of out of jail free’ card,” Yost said. “We are equipping law enforcement with the resources to do their jobs.”

He also took a pot shot at Columbus City Attorney Klein, saying: “It’s unfortunate that Columbus has decided to create an island within Franklin County where the general laws of the state of Ohio no longer apply.”

For now, though, it seems like “the general laws of the state of Ohio no longer apply” just about everywhere in the state when it comes to prosecuting marijuana cases.

In Texas, prosecutors have already dropped hundreds of low-level marijuana cases and said they won’t pursue more without further testing. Again, it’s that inability of standard tests to tell the difference between hemp and marijuana.

“The distinction between marijuana and hemp requires proof of the THC concentration of a specific product or contraband, and for now, that evidence can come only from a laboratory capable of determining that type of potency—a category which apparently excludes most, if not all, of the crime labs in Texas right now,” read a June advisory from the Texas District and County Attorneys Association.

Since then, top prosecutors from across the state and across the political spectrum, including those in Bexar (San Antonio), Harris (Houston), Tarrant (Fort Worth), and Travis (Austin), have dismissed hundreds of cases and are refusing more:

“‘In order to follow the Law as now enacted by the Texas Legislature and the Office of the Governor, the jurisdictions … will not accept criminal charges for Misdemeanor Possession of Marijuana (4 oz. and under) without a lab test result proving that the evidence seized has a THC concentration over 0.3%,’ wrote the district attorneys from Harris, Fort Bend, Bexar and Nueces counties in a new joint policy released … [in July].”

Travis County officials said they had dropped 32 felony and 61 misdemeanor marijuana cases, and they wouldn’t be doing any more—at least for now.

“I will also be informing the law enforcement agencies by letter not to file marijuana or THC felony cases without consulting with the DA’s Office first to determine whether the necessary lab testing can be obtained,” Travis County District Attorney Margaret Moore tweeted.

As in Ohio, law enforcement is awaiting the availability of certified testing labs, but in the meantime, pot prosecutions are basically nonexistent in most of the state’s largest cities. And now, some Austin city council members are even wondering whether cops there should bother to hand out tickets for pot possession.

It’s not just Texas and Ohio. Once Florida’s hemp law went into effect, the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office announced it would no longer prosecute small-time marijuana cases and police in numerous southwest Florida towns and cities are also putting marijuana arrests on pause.

“Since there is no visual or olfactory way to distinguish hemp from cannabis, the mere visual observation of suspected cannabis—or its odor alone—will no longer be sufficient to establish probable cause to believe that the substance is cannabis,” wrote Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle. “Since every marijuana case will now require an expert and necessitate a significant expenditure by the State of Florida, barring exceptional circumstances on a particular case, we will not be prosecuting misdemeanor marijuana possession cases.”

Other state attorneys across the state are issuing similar memos. In Gainesville, prosecutors are dropping all cannabis charges. But other prosecutors say they will continue to review each case individually, with some like Tallahassee saying they will try “a variety of arguments” before the courts, while other places like Orlando and the Treasure Coast say they will wait until after they receive lab tests before filing charges.

Just across the state line in Georgia, similar scenes are playing out. Gwinnett County Solicitor General Brian Whiteside has begun dropping marijuana cases brought forward since that state’s hemp law went into effect, and the Gwinnett County Police Department is now writing tickets for pot possession instead of making arrests.

In Cobb County, Solicitor General Barry Morgan warned there would be no blanket dismissal of marijuana cases, but the police chief there sent a memo to his staff saying that “arresting someone for misdemeanor marijuana possession is not recommended.”

In Athens-Clarke County, police have been instructed to stop making arrests or issuing citations. Instead, they will seize the substance in question and write a report. Once testing is available and the THC level is above legal limits, they will then seek an arrest warrant. And DeKalb County is dismissing marijuana cases too, with Solicitor General Donna Coleman-Stribling saying the county “will not proceed with any single-count marijuana cases occurring after the passage of this new law.”

It’s not just marijuana arrests and prosecutions that are at stake. Neither police nor drug dogs can sniff out the difference between hemp and marijuana. That is going to make it more difficult for police to develop probable cause to search people or vehicles, and it’s likely to lead to the early retirement of a generation of drug dogs.

“The dogs are done,” said State Attorney Jeff Siegmeister of Florida’s Third Judicial District. “If they’re pot-trained, I don’t know how we can ever re-certify them. Unless they’re trained in the future in a different way, in my area, every dog is going to be retired.”

“The dog doesn’t put up one finger and say, ‘cocaine,’ two fingers and say, ‘heroin,’ and three fingers and say, ‘marijuana,’” admitted Florida Sheriff’s Association President Bob Gaultieri. “We had a very, very hard bright line up until this point that if a cop walks up to a car and you smell marijuana, well no matter what it was, any amount of THC is illegal, so if you smelled it, that gave you probable cause. … Now that bright line isn’t bright anymore. Now if you walk up to a car and you smell marijuana, you have to conduct an investigation, and that along with other things may give you probable cause.”

And it isn’t just a handful of states. Any state that has legalized hemp with less than 0.3 percent THC but hasn’t legalized marijuana could face similar quandaries.

“This is a nationwide issue,” said Duffie Stone, president of the National District Attorneys Association and a South Carolina prosecutor. “This problem will exist in just about every state you talk to.”

There is one quick fix, though: Legalize marijuana.

This article was produced by Drug Reporter , a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Phillip Smith is a writing fellow and the editor and chief correspondent of Drug Reporter, a project of the Independent Media Institute. He has been a drug policy journalist for the past two decades. He is the longtime author of the Drug War Chronicle, the online publication of the non-profit StopTheDrugWar.org, and has been the editor of AlterNet’s Drug Reporter since 2015. He was awarded the Drug Policy Alliance’s Edwin M. Brecher Award for Excellence in Media in 2013.

Lost in India

“The Twice-Born: Life and Death on the Ganges”

A book by Aatish Taseer

Aatish Taseer’s luscious passages about India’s many hidden worlds are as moving as his reflections on identity, place, and his search for an elusive “home.” Yet there is a whiff of fraudulence about Taseer. Hints of the impostor shadow him—a double-impostor really, since his deceptions seem designed to fool not only us but himself as well. He accomplishes neither. The odd thing is that his duplicitousness does not alienate us, but pulls us in closer. Somehow, we can’t abandon this trickster.

In “The Twice-Born: Life and Death on the Ganges,” Taseer writes of his journey to India, returning from London, where he currently lives. He grew up in Delhi, the son of a nonpracticing Sikh mother, a prominent journalist, and a Pakistani Muslim father. Taseer’s father and Taseer’s mother had a brief extramarital affair, and shortly afterward his father returned to his wife. His father, Salman Taseer, later became the governor of Punjab in Pakistan. He was assassinated in 2011, after speaking out against the blasphemy laws, which he considered archaic. He described himself to Taseer as a cultural Muslim.

Click here to read long excerpts from “The Twice-Born” at Google Books.

Taseer was raised by his mother and maternal grandparents, who were part of India’s English-speaking upper class. He had very little contact with his father during his formative years. Their few interactions were fraught with tension. Taseer wrote about their relationship in his earlier autobiographical work, “Stranger to History”; he openly criticized his father in the book, dismayed with his father’s more intolerant views and his erroneous proclamations about the Holocaust.

In his new work, Taseer shares with us his intentions:

“My time in the West had given me an outside view of my world in Delhi, robbing my life there of its easy, unthinking quality. I thought I should do something, by way of traveling or learning, that would help me establish a connection with India at large, the country that lay beyond the seemingly impermeable confines of life in Delhi. I wondered if I should learn Sanskrit, the ancient language of India. It was no longer spoken, but, like Latin or ancient Greek, it retained its liturgical function among India’s Hindu majority. I would have had some notion of a vast body of literature in Sanskrit, but, as more an absence than a presence, it was further proof of an intellectual inheritance that had not come down to me. Absences can be suggestive, and I wondered if a voice from the past might serve as a beginning point in my quest to reconnect with India’s history and language. That was why I went to see Mapu, an old friend of my mother’s. He was among the few people I knew who had sought to regain what a colonial education had denied him: he had attempted a version of Frantz Fanon’s ‘return to self.’”

When Taseer explains to Mapu his desire to study Sanskrit in Benares, Mapu is impressed with what he believes to be the young man’s religious zealousness. Taseer’s desire to learn Sanskrit, however, is more of an “attempt to deal intellectually with a country whose reality perturbed me.” Mapu describes Benares as a magical place where one can “see in miniature every major event that had etched itself onto India’s consciousness. The entire history of the subcontinent lay in bits and pieces on its river shore…”—bits and pieces like the British rule that came to India in 1794, and the eventual ascent of Nehru in 1947, two events that Mapu felt robbed India of its Hindu culture. Mapu sends Taseer to a potential guru, Kamlesh Dutt Tripathi, a Brahmin—a social class of priests and teachers—at the top of the Hindu caste system. Brahmins make up less than 10% of India’s enormous population, who mostly live in dire poverty. The Brahmins are considered “twice-born”: once at birth, and again when they are initiated by rite into the ancient vocation of the mind.

Taseer is too timid to approach Tripathi at first, as the great man speaks with other Sanskrit scholars, debating esoteric issues. But Taseer pours himself into his studies, learning the epics, plays, treatises, court poems, and literary analyses that are part of his cultural heritage. He begins to think that perhaps he had been raised with a “passionless aversion to his own culture.” But soon enough, doubts surface. Although it is incredibly stimulating to glimpse the antiquity of a “sacralized form of learning, to witness was not to participate.” The world of ritual was closed off to him: “a break had occurred, and I was on the other side of it.”

Taseer comes to see Tripathi, with whom he was initially so impressed, as inflexible, obsessed with the past, and blind to the contributions of modernity. Tripathi sends him to another Brahmin guide, P.K. Mukhopadhyay. Mukhopadhyay tells Taseer of a student he invited to supper in his home. He fed the student, but was “forced” to ask him to clean his own plate and utensils after eating because he was from a lower caste: “The deed of a past life had left the young man Mukhopadhyay spoke of, spiritually unclean.” Taseer, appalled, confronts Mukhopadhyay about the elitism and racism that he embraces; Mukhopadhyay is unmoved. The Indian constitution has outlawed caste, but it still remains an essential part of life in India. Taseer is not only disillusioned with Mukhopadhyay; he is angry. He no longer sees him as a mystic or someone with access to revelations closed off to him, but rather a privileged man who hides under the umbrella of caste, oblivious to the suffering that surrounds him. Taseer leaves him.

He roams the streets of Benares and is approached by soothsayers, palmists, witch doctors, astrologers, exorcists, and other “holy” men who offer prayers that start to sound like threats. He writes that the streets of Benares have a demonic energy that was “primal, cruel, full of laughter.”

Still uncertain about who he is or wants to be, Taseer returns to New York City and his new husband, a man he met from the American South on a dating app. But he doesn’t tell us much about him, or about his mother, besides how often she was away while he was a child. He discussed his anxieties about his father with multiple therapists. Taseer does mention his maternal grandmother, who delighted him with stories about the Hindu faith, and he recalls that at 5 or 6 he began lighting incense and chanting prayers and offering marigolds to the gods. But it didn’t last long. When Taseer was in India, a religious Brahmin asked him directly whether he believed in God. Taseer said no, and the Brahmin told him that he has no dharma: having no place in the world that is meaningful or righteous. In some ways, Taseer agrees with him.

A recent video on the internet of Taseer speaking at Amherst College about “The Twice-Born” is painful to watch. Taseer reads his prepared text quickly, swallowing his words, and rarely looks up at the students. Fielding the students’ questions, he seems lost and has trouble speaking extemporaneously. He still can’t explain why he went to India and what he was looking for. He has difficulty describing what he believes now. He has trouble defining who he is. He seems nervous. But he also seemed to me to be mourning all that he still could not say and feel—all the emotional wounds he could not confront. And yet, as with his book, he kept me pulled tightly into his orbit despite his fumbling presentation. Somehow, I could not look away.

Lesbians Are a Target of Male Violence the World Over

Since coming out as a lesbian at the age of 15 in 1977, I have seen the world change for the better. When I met other lesbians soon after leaving home to find the “gay scene,” I was shocked to hear stories of women losing custody of their children, in some cases to violent ex-husbands, for the simple reason that they were in a same-sex relationship.

Over the decades in the U.K., I have seen and experienced anti-lesbian violence firsthand. I have been attacked on more than one occasion—physically assaulted by anti-gay bigots, and sexually assaulted by a man who thought he could “straighten me out.” I’ve lost housing and jobs as a result of being a lesbian.

The first time I was physically attacked was in a gay and lesbian bar in the U.K. I was 16, and out with David, a gay friend who had taken me under his wing. We were dancing and laughing, having great fun. David was encouraging me to talk to other girls, but I was too shy. Suddenly, a small group of men was upon us, pointing their fingers in our faces. “Are you a puff [faggot]?” one of them asked David. “Prove you are a proper man and fuck her,” another growled, pulling me over to David by my hair. I was terrified, and David started crying. People had begun to notice what was happening, but no one approached us.

Related Articles

Has Popular Feminism Failed Us All?

by

Activist Zeros In on Canada’s Indigenous Women

by Julie Bindel

The men were big and menacing, with shaven heads and combat clothing. I lived close to a garrison town, and there were high levels of sexual assaults by soldiers in the vicinity.

After a few minutes of being swung around by my arms and my hair, and David being jabbed in his stomach and groin, the men spat at us and left the club, laughing. David and I never spoke of the incident—he, I suspect, feeling the deep shame and stigma that I did.

A year later, I moved to a large city in the north of England. Leeds was far more diverse than my home town, but unfortunately had become a key base for a group of fascists known as Combat 18 (the numbers 1 and 8 representing the numerical order of Adolf Hitler’s initials in the alphabet).

I lived in a hostel with my girlfriend, who was black. Our windows were regularly broken by young fascist males, and graffiti daubed on our front door. One evening, we were chased through a park by skinheads brandishing chains, shouting that they were going to “skin and rape” the “black bastard” and her “n*****-loving queer.” We escaped into a neighbor’s house, where we had to endure a lecture on how we had brought “trouble to the neighborhood,” and the neighbor demanding to know whether we had to “shove what you are down everyone’s throats.”

At the time, I had a job cleaning in a gay and lesbian bar that was run by a straight couple, Bob and Doreen, and their son, Simon. Bob and Doreen had retired from the police service, and saw financial opportunities in running a bar for the many lesbians and gay men who had gravitated to the city from the surrounding rural areas and small towns. “The queers have loads of money,” Bob used to say. “They don’t have kids to feed.”

One day, when I was cleaning the apartment above the pub, Bob and Simon attempted to rape me. They were laughing, telling me I needed a “good fuck.” I managed to escape only because they heard Doreen come up the stairs.

There have been many other times when I have been attacked or endangered by men who targeted me for being a lesbian. I was once thrown down the stairs by a nightclub bouncer and punched in the face by a man in the street when I refused his advances. I learned to fight back, stay out of nightclubs, and to view these attacks as part of a misogynistic backlash by men who feel threatened by women’s sexual and social autonomy.

Throughout my early years, there were very few public role models. The depiction of lesbians was hardly flattering. Butch, predatory and deeply unattractive, these images served as a warning to women not to “cross over to the dark side.”

Lesbians in the U.K. have fought for and achieved legislative equality with heterosexuals. We can marry, adopt and foster children, and have next-of-kin rights with a same-sex partner. It is now illegal to fire us from our jobs or refuse goods and services on the grounds of our sexuality.

These changes also are prevalent across the majority of states in the U.S. and in numerous other countries around the world. But there are still plenty of places that have either rolled back the rights of lesbians, such as Russia under President Vladimir Putin, or, under the influence of religious fundamentalists, have introduced archaic and extremely punitive legislation affecting LGBTQ people.

I decided to investigate the horrific story of violence towards lesbians, because this is a tale that is rarely told. “We hear about the oppression of gay men and of trans people,” one senior U.N. official told me at a meeting on sexual orientation and gender identity rights, “but rarely do lesbians come anywhere near the top of the list, even when we are zoning in on LGBT rights.”

Uganda

My journey took me to Uganda, a beautiful country in East Africa that has some of the worst legislation on and social attitudes toward lesbian and gay rights on the planet.

Its Parliament passed an anti-homosexuality bill in 2013 that lengthened sentences for consensual homosexual sex and extended punishment to those promoting homosexuality. It is illegal to be gay in most African countries, and in Uganda, same-sex encounters can land a person in prison for, on average, seven years. Same-sex marriage is illegal.

The first LGBTQ organization in Uganda was Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG), founded in 2003 by three lesbians. I met Gloria, who joined FARUG in 2015, during a recent trip to Uganda. She explained what a struggle it has been to keep the organization afloat in a country so openly hostile to LGBTQ people.

“In our community, butch women, dykes and lesbians face the most stigma, discrimination and violence, because the world was seeing them as men,” Gloria said. “We knew they were going to be targeted, but what happened has a lot to do with the trans movement, especially trans men. Many of the out trans men started as lesbians. I think they discovered their identity as they went on. So, many people are going to be targeted, not only lesbians but even trans men still in the process of trying to deal with the changes to do with their sexuality.”

Homophobic legislation in Uganda has its roots in the religious right in the United States. In 2009, American evangelist Scott Lively traveled to Uganda to set up an anti-gay movement, enlisting support from local preachers such as Pastor Sember, who ran a church within Makerere University. “The evangelists started the anti-gay movement and would go into churches preaching hate against LGBT persons. Before then, there was hate, but there wasn’t a solid religious propaganda, so they started that movement,” explained Gloria, who was a student at Makerere at the time. “Pastor Sember stands in church one Sunday and says, ‘We’re going to have a huge crusade that is aimed at fighting homosexuality in Uganda.’ They got around 10,000 people on that crusade, and there was a lot of hate speech. During that crusade they were talking about how homosexuality is infiltrating the nation, and how white people have brought homosexuality here and how they are paying Ugandans to become homosexual.”

The result was a build-up of public anger toward the LGBT community in Uganda. “We knew they were coming after us,” Gloria said. “During that time, FARUG struggled a lot. In 2016, our organization operated without money. I remember having an extraordinary meeting, and the person who is now our director stood up and said, ‘This is our child. If we do not stand, this organization is going to fall, but I need you to understand that we started this movement. When I talk about the movement, it’s not just about me, it’s about you. It’s not just us the activists, it’s the fact that you can still move in the street, that you can still access medical care, that we can still represent you in court when people are being terrible to you.’”

I spoke with Amanda, 29, who came to FARUG for “social Friday,” a monthly gathering where LBQ women can relax with their friends, meet new members and, later in the day, drink and dance.

Amanda was present at the notorious police raid of the Venom bar in 2016. “There were police all over the place accusing us of holding a gay wedding,” she recalled. “They said we were thieves and arrested us on the premises. It was so scary. I phoned my sister and said, ‘If anything happens to me, I am at this place.’ We were there for hours. Then some kid jumped off the fourth floor of the building to escape the police. It was so bad.”

Simon Mpinga is the pastor at the Living Gospel World Mission church in Kawuga village, on the edge of Kampala. Mpinga also preaches at the Fellowship of Affirming Ministries church, known for its inclusion and acceptance of lesbians and gay men. I went to meet him with Nasiche, a lesbian who told me she refuses to give up her faith “just because of those pastors that hate us.”

Mpinga greeted us at the door of his small church, which was full of congregants enjoying a meal of rice and beans. Tall and handsome, he was wearing a bright T-shirt and a big smile. I asked what led him to open a LGBTQ-inclusive church in the face of such resistance. “As I was growing up,” he explained, “I saw bigotry towards LGBT people happening in the churches. The moment people discovered that someone was gay or bisexual, they would push them out of the ministry, discriminate against them, speak ill about them; they would be psychologically tortured and become depressed. It was a terrible thing.”