Chris Hedges's Blog, page 126

October 18, 2019

Will the GOP Become the Party of Blue-Collar Conservatism?

From the days of Franklin Delano Roosevelt onward through to the 1990s, the Democrats had long been considered the party of the working class. That perception lingered long after the fact that by the 1990s, they had more accurately become the party of Wall Street and Silicon Valley, often embracing policies at variance with their traditional blue-collar supporters. As Thomas Ferguson, Paul Jorgensen, and Jie Chen outline in a paper sponsored by the Institute for New Economic Thinking: “Within the Democratic Party, the desires of party leaders who continue to depend on big money from Wall Street, Silicon Valley, health insurers, and other power centers collides [sic] head on with the needs of average Americans these leaders claim to defend.” So the Democratic Party, a historically center-left political grouping, has increasingly embraced a neoliberal market fundamentalist framework over the past 40 years, and thereby facilitated the growth of financialization (whereby the influence and power of a country’s financial sector become vast relative to the overall economy).

Donald Trump exploited that shift during his 2016 campaign: Not only did he proclaim his love for “the poorly educated,” but he also campaigned as an old Rust Belt Democrat—not only by attacking illegal immigration and offshoring, but also coming out against globalization, free trade, Wall Street, and especially Goldman Sachs.

As president, of course, Trump has proven incapable of “walking the walk,” even as he continued to speak about “draining the swamp” and eliminating business as usual in Washington. But there is increasing evidence suggesting that some of the more ambitious and opportunistic politicians in the GOP are seeking to exploit the material abandonment of working-class voters by the Democrats. Both Senators Josh Hawley and Marco Rubio are trying to move the party in a more pro-worker direction, championing a new kind of blue-collar conservatism that is supportive of unions and policies that emphasizes the “dignity of work.” Likewise, Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas has recently introduced a tax rebate for lower-income Americans to offset the tariffs President Trump has proposed on Chinese goods—essentially an annual payment from the federal government to citizens to offset any increased cost in consumer goods that might arise from Trump’s proposed tariffs, thus neutralizing the economic impact, and countering the political argument that the president’s trade war on Chinese goods ultimately represents a tax on American consumers. As Henry Olsen notes in the Washington Post:

Related Articles

American Workers Have Little to Celebrate This Labor Day

by Juan Cole

The Capitalists Are Afraid

by Chris Hedges

Elizabeth Warren Introduces Plan to Strengthen Organized Labor

by

“Cotton’s approach addresses both the economic and political challenges arising from Trump’s tariffs. Economically, giving the revenue back to average Americans offsets the expected rise in prices they will face as a result of the tariffs. Consumer spending, which was feared would decline in response to the price hikes, would now likely stay high: Why cut back in spending when you’re not losing any money? That would keep the economy strong.”

In other words, it’s a tax-time Universal Basic Income.

Cotton’s proposals would augment a little-discussed feature emerging now in the U.S. labor market, as CNBC’s Jeff Cox writes: for the first time in this cycle (which started in 2009), “the bottom half of earners are benefiting more than the top half—in fact, about twice as much, according to calculations by Goldman Sachs,” using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. More recently, Derek Thompson of the Atlantic cites additional work by labor economist Nick Bunker, who makes the case that “wage growth is currently strongest for workers in low-wage industries, such as clothing stores, supermarkets, amusement parks, and casinos. And earnings are growing most slowly in higher-wage industries, such as medical labs, law firms, and broadcasting and telecom companies.” Absent a significant growth slowdown, these workers might increasingly identify their economic self-interest with Republicans, not Democrats, particularly given the increasingly restrictionist stance the GOP is adopting on immigration, which will further tighten the labor market structurally and enhance the relative bargaining position of American blue-collar workers.

The one lingering question is whether or not this trend will yet supersede the power and influence of the GOP’s historic corporate constituencies, notably oil, mining and chemical companies, Big Pharma, tobacco, the arms industry, and civil aviation. On the face of it, this could well prove to be a tall order. But it is conceivable if trade policy is ultimately rendered subordinate to national security concerns, as increasingly appears to be the case today. In the words of Michael Lind, all it would take is a national developmental industrial strategy predicated on sustaining U.S. military supremacy: “to identify and promote not specific companies but key ‘dual-use’ industries important in both defense and civilian commerce.” That would seem to be a more likely scenario for the GOP, one that would build on Trump’s steady inroads into the Democratic Party’s traditional blue-collar constituencies, while simultaneously catering to the party’s strong links to national defense interests.

Although a military-industrial strategy might run counter to some of the interests of the party’s traditional corporate backers (such as Charles Koch), it would likely prove hugely beneficial to America’s manufacturing heartland, particularly the country’s disaffected blue-collar workers. Historically, these workers have been Democrats, but their livelihoods have been decimated by decades of trade liberalization and other neoliberal policies. As Lind points out, a national industrial policy based on the model of Alexander Hamilton but married to “Cold War 2.0” could, therefore, consolidate the GOP’s efforts to become more of a party of the working class. And such a policy is not historically anomalous: during the original Cold War, free trade and globalization were always subject to the constraints of containing the expansion of Soviet-led communism. A large chunk of the world under the enemy sphere of influence was off-limits to American trade and capital.

Today, even with the overriding influence of the Koch brothers, and the Mercer family, a number of Republicans are geopolitical hawks first, and economic libertarians second. They increasingly see that it makes no sense to go to war against wage earners while claiming to protect the same wage earners from Chinese competition, especially if Beijing becomes the new locus of an emerging Cold War 2.0. Furthermore, if they are in safe, rock-solid GOP districts, they are less vulnerable to a primary attack from corporate interests antithetical to those positions. As geo-economics is increasingly remarried to geopolitics (as it was during the original Cold War), “blue-collar conservativism” will likely gain increasing policy traction in certain conservative circles, even though Republicans still have a ways to go before they can fully shift their party’s agenda toward a modern-day equivalent of “Bull Moose” progressivism.

Donald Trump is, first and foremost, a wrecker, as opposed to a builder. Arguably, that is one of the things that got him elected in the first place. But he has set the stage for a further political realignment, especially as more educated whites and elites migrate to the Democratic Party, and traditional Southern populists reside in the GOP. There are very few Fritz Hollings types left in the party, whose views on trade, immigration and manufacturing are closer to the Democrats’ historic New Deal constituencies. This theory, though, is not watertight, and new coalitions are still very much in flux. But as things stand today, ironically, the Democrats now have trade and open borders policies that are closer to those of the old Reagan/Bush Republicans and libertarians such as the Koch brothers, while the GOP policy under Trump is gravitating toward the old positions of the AFL/CIO on both trade and immigration, a policy combination that makes the embrace of a kind of blue-collar conservatism even more credible for the GOP. Furthermore, as trade issues (especially in regard to China) are increasingly conflated with national security concerns, the GOP may ultimately decide to build on Trump’s attempts to re-domicile key supply chains back to the U.S. From the national security hawk perspective, this will ensure that strategic industries necessary to sustain American military power remain on home shores, even if this conflicts with the principles of free trade, limited non-interventionist government. Sustaining permanent production on U.S. soil, not just innovation in America and production elsewhere, would be profoundly favorable to blue-collar workers (hitherto among the biggest casualties of globalization) and likely consolidate the GOP’s efforts to become the future party of the American working class, unless of course the Democrats suddenly and unexpectedly reclaim their New Deal legacy.

This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Marshall Auerback is a market analyst and commentator.

Why I Can’t Get Excited About Impeaching Trump

This piece originally appeared on Chicago Reader.

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi has begun an impeachment inquiry into President Trump for asking Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky to investigate former vice president Joe Biden and his son Hunter. I get that there is a strong desire for many Americans to be rid of what they see as the national nightmare of Trump’s presidency. But I urge caution for several reasons.

First, this impeachment inquiry will not succeed in getting rid of Trump. To win, a supermajority of the Senate must vote for impeachment. This will not happen. Even if the inquiry clearly shows that Trump withheld military aid to pressure President Zelensky to give him dirt on Joe and Hunter, the inquiry will also expose the sleaziness of the Bidens.

Related Articles

The Legal Biden Family Corruption Democrats Refuse to Acknowledge

by Max Blumenthal

Joe Biden Has Corporate Democrats in Panic Mode

by Norman Solomon

Joe Biden Unmasked

by Tangerine Bolen

After the successful overthrow of the elected Ukrainian government in 2014, Hunter Biden was paid $50,000 a month to sit on the board of Ukraine’s biggest gas producer, Burisma Holdings. While this shady deal might not provide a legal defense to Trump, an impeachment inquiry is political, not criminal, and the behavior of the Bidens will at least muddy the waters enough to assure that Trump will survive impeachment.

Second, the mere fact that our corporate-controlled Congress is willing to take up the impeachment inquiry guarantees that it will produce no major reforms to better the lives of most Americans. Keep in mind that our national politics is dominated by two political parties that are beholden to the interests of big-money donors. Sure, there are a few members of Congress who don’t rely on big donors, but they are the exception, and they do not control the agenda of their parties. Thus, rest assured that the big donors to Congress—big pharma, fossil fuel extractors, Wall Street, weapons manufacturers, agribusiness, big insurance, and for-profit health care—approve of its spending six months debating impeachment. Big business believes this impeachment inquiry will not threaten corporate profits or its ability to continue exerting control over government policy.

A dozen years ago, Speaker Pelosi rejected calls to begin an impeachment inquiry against President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney for lying us into the war in Iraq. The evidence there was clear and unambiguous. Bush and Cheney told the American people that there was “no doubt” that Iraqi president Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. In fact, as the Bush team knew, the evidence of Saddam’s WMDs was highly dubious. It was based on the word of a paid informant named Curveball, and on a crudely forged invoice purporting to show Saddam buying uranium from Africa. Both Curveball and the invoice were exposed as frauds, but Bush and Cheney continued lying to sell the war.

Bush’s lies resulted in the deaths of at least a million innocent people, the destruction of a country, and the creation of ISIS. He and Cheney committed monstrous crimes, similar to crimes resulting in the execution of German generals at Nuremberg after World War II. Why then did Speaker Pelosi announce in 2006 that impeachment was “off the table” for Bush? Because the big corporate donors didn’t want impeachment hearings over the Iraq war. Rather, the arms manufacturers, fossil fuel extractors, and other war profiteers want our presidents to be free to lie us into wars without any negative repercussions for the president, such as criminal penalties or impeachment.

The third reason I can’t get excited about impeachment hearings is that they won’t even be good entertainment. Back in October 1998, when Congress launched impeachment hearings against Bill Clinton relating to sex with an intern—another issue that was not in any way threatening to corporate profits—there were at least sordid details about a cigar and a stained dress that made it worthwhile turning on the TV.

To be sure, there are sordid details to the Ukraine story that could be exposed. After the U.S.-backed coup that overthrew the sovereign government, not only did Hunter Biden get a seat on the gas company board, but agricultural giant Monsanto got a big contract in Ukraine. Just last month, Trump’s special envoy for Ukraine negotiations, Kurt Volker, was forced to resign after it came out that he was advocating sending lethal tank-busting Javelin missiles, manufactured by Raytheon Co., to Ukraine, while Volker also worked for a lobbying firm and a think tank with financial ties to Raytheon.

These revelations about Ukraine could help expose the deep-seated and longstanding corruption of U.S. foreign policy, which includes overthrowing elected governments to serve the interests of corporations that then support the campaigns of lawmakers and presidents, producing the endless cycle of wars that are bankrupting our nation and accelerating the destruction of the planet. But this part of the Ukraine story would be very threatening to corporate profits. So don’t expect to hear much about it during the coming months of impeachment inquiries.

Leonard C. Goodman is a Chicago criminal defense attorney and co-owner of the newly independent Reader.

Trump’s Withdrawal From Forever War Is Just Another Con

On Monday, October 7, the U.S. withdrew 50 to 100 troops from positions near Syria’s border with Turkey, and two days later Turkey invaded Rojava, the de facto autonomous Kurdish region of northeast Syria. Trump is now taking credit for a temporary, tenuous ceasefire. In a blizzard of tweets and statements, Donald Trump has portrayed his chaotic tactical relocation of U.S. troops in Syria as a down payment on his endless promises to withdraw U.S. forces from endless wars in the greater Middle East.

On October 16, the U.S. Congress snatched the low-hanging political fruit of Trump’s muddled policy with a rare bipartisan vote of 354-60 to condemn the U.S. redeployment as a betrayal of the Kurds, a weakening of America’s credibility, a lifeline to ISIS, and a political gift to Russia, China and Iran.

But this is the same Congress that never mustered the integrity to debate or vote on the fateful decision to send U.S. troops into harm’s way in Syria in the first place. This vote still fails to fulfill Congress’s constitutional duty to decide whether U.S. troops should be risking their lives in illegal military operations in Syria, what they are supposed to be doing there or for how long. Members of Congress from both parties remain united in their shameful abdication of their constitutional authority over America’s illegal wars.

Related Articles

Ending the Afghan War Won’t End the Killing

by

What’s Driving the American Cult of Endless War?

by

Democrats Have No Answer for Trump's Anti-War Posture

by Maj. Danny Sjursen

Trump’s latest promises to “bring the troops home” were immediately exposed as empty rhetoric by a Pentagon press release on October 11, announcing that the Trump administration has actually increased its deployments of troops to the greater Middle East by 14,000 since May. There were already 60,000 troops stationed or deployed in the region, which the Congressional Research Service described in September as a long-term “baseline,” so the new deployments appear to have raised the total number of U.S. troops in the region to about 74,000.

Precise numbers of U.S. troops in each country are hard to pin down, especially since the Pentagon stopped publishing its troop strength in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria in 2017. Based mainly on reports by the Congressional Research Service, these are the most accurate and up-to-date numbers we have found:

14,000 -15,000 (plus 8,000 from other NATO countries) in Afghanistan

about 7,000 , mostly U.S. Navy, in Bahrain

280 in Egypt

5,000- 10,000 in Iraq, mostly at Al Asad Air Base in Anbar Province

2,800 in Jordan (some may now have been relocated to Iraq)

13,000 in Kuwait, the fourth-largest permanent U.S. base nation after Germany, Japan and South Korea

a “few hundred” in Oman

at least 13,000 in Qatar, where the Pentagon just approved a $1.8 billion expansion of Al Udeid Air Base, U.S. Central Command’s regional occupation headquarters

about 3,500 in Saudi Arabia, including 500 sent in July and 2,500 more since September

1,000- 2,000 in Syria, who may or may not really be leaving

1,750 at Incirlik and Izmir Air Bases in Turkey

more than 5,000 in the UAE, mostly at Al Dhafra Air Base

As for actually ending the wars that all these forces are waging or supporting, Trump escalated the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria in 2017, and these bombing campaigns rumble on regardless of peace talks with the Taliban and declarations of victory over the Islamic State. U.S. air wars are often more devastating than ground warfare, especially to civilians.

Between 2001 and October 2018, the U.S. and its allies dropped more than 290,000 bombs and missiles on other countries. This reign of terror has not stopped, for according to U.S. airpower statistics, from November 2018 to September 2019 the U.S. has now dropped another 6,811 bombs on Afghanistan and 7,889 on Iraq and Syria.

In Donald Trump’s first 32 months in office, he is responsible for dropping 17,100 bombs and missiles on Afghanistan and 48,941 on Iraq and Syria, an average of a bomb or missile every 20 minutes. Despite his endless promises to end these wars, Trump has instead been dropping more bombs and missiles on other countries than George H.W. Bush and Obama put together.

When Congress finally invoked the War Powers Act to extricate U.S. forces from the Saudi-led war on Yemen, Trump vetoed the bill. The House has now attached that provision to the FY2020 NDAA military spending bill, but the Senate has not yet agreed to it, and Trump may find another way to exclude it.

Even as Donald Trump rails against the military-industrial complex that “likes war” and sometimes sounds sincere in his desire to end these wars, he keeps hiring arms industry executives to run his foreign and military policy. His first defense secretary was General Dynamics board member and retired General James Mattis. Then he brought in Boeing’s senior vice president Patrick Shanahan as acting secretary of defense, and now Raytheon lobbyist Mark Esper as secretary of defense. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made his fortune as the co-founder of Thayer Aerospace. Trump boasts about being the best weapons salesman of all, touting his multibillion-dollar deals to provide the repressive Saudi regime with the weapons to commit crimes against humanity in Yemen.

And yet withdrawal from endless wars is one Trump campaign promise that Americans across the political spectrum hoped he would really fulfill. Tragically, like “drain the swamp” and other applause lines, Trump’s promises to end the “crazy, endless wars” have proven to be just another cynical ploy by this supremely cynical politician and con man.

The banal truism that ultimately defines Trump’s foreign policy is that actions speak louder than words. Behind the smokescreen of Trump’s alternating professions of faith to both sides on every issue, he always ends up rewarding the wealthy and powerful. His cronies in the arms industry are no exception.

Sober reflection leads us to conclude that Trump’s endless promises will not end the endless wars he has been waging and escalating, nor prevent the new ones he has threatened against North Korea, Venezuela and Iran. So it is up to the rest of us to grasp the horror, futility and criminality of the wars that three successive U.S. administrations have inflicted on the world and to organize effective political action to end them and prevent new ones.

We also need help from legitimate mediators from the UN and mutually trusted third parties to negotiate political and diplomatic solutions that U.S. leaders who are blinded by deeply ingrained militarism and persistent illusions of global military dominance cannot achieve by themselves.

In the real world, which does still exist beyond the fantasy world of Trump’s contradictory promises, that is how we will bring the troops home.

This article was produced by Local Peace Economy, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Medea Benjamin, co-founder of CODEPINK for Peace, is the author of several books, including Inside Iran: The Real History and Politics of the Islamic Republic of Iran and Kingdom of the Unjust: Behind the U.S.-Saudi Connection.

Nicolas J. S. Davies is an independent journalist, a researcher for CODEPINK, and the author of Blood on Our Hands: The American Invasion and Destruction of Iraq.

First All-Female Spacewalking Team Makes History

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla.—The world’s first all-female spacewalking team made history high above Earth on Friday, replacing a broken part of the International Space Station’s power grid.

As NASA astronauts Christina Koch and Jessica Meir completed the job with wrenches, screwdrivers and power-grip tools, it marked the first time in a half-century of spacewalking that men weren’t part of the action.

America’s first female spacewalker from 35 years ago, Kathy Sullivan, was delighted. She said it’s good to finally have enough women in the astronaut corps and trained for spacewalking for this to happen.

“We’ve got qualified women running the control, running space centers, commanding the station, commanding spaceships and doing spacewalks,” Sullivan told The Associated Press earlier this week. “And golly, gee whiz, every now and then there’s more than one woman in the same place.”

NASA leaders, Girl Scouts and others cheered Koch and Meir on. Parents also sent in messages of thanks and encouragement via social media. NASA included some in its TV coverage. “Go girls go,” two young sisters wrote on a sign in crayon. A group of middle schoolers held a long sign reading “The sky is not the limit!!”

At the same time, many expressed hope this will become routine in the future.

Tracy Caldwell Dyson, a three-time spacewalker who looked on from Mission Control in Houston, added: “Hopefully, this will now be considered normal.”

NASA originally wanted to conduct an all-female spacewalk last spring, but did not have enough medium-size suits ready to go until summer. Koch and Meir were supposed to install more new batteries in a spacewalk next week, but had to venture out three days earlier to deal with an equipment failure that occurred over the weekend. It was the second such failure of a battery charger this year, puzzling engineers and putting a hold on future battery installations for the solar power system.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine watched the big event unfold from Washington headquarters.

“We have the right people doing the right job at the right time,” he said. “They are an inspiration to people all over the world including me. And we’re very excited to get this mission underway.”

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi sent congratulations to Koch and Meir “for leaving their mark on history” and tweeted that they’re an inspiration to women and girls across America.

The spacewalkers’ main job was to replace the faulty 19-year-old old charge-regulating device — the size of a big, bulky box — for one of the three new batteries that was installed last week by Koch and Andrew Morgan. A preliminary check showed everything to be good 250 miles (400 kilometers) up, but several more hours were needed to confirm that.

“Jessica and Christina, we are so proud of you,” said Morgan, one of four astronauts inside. He called them his “astrosisters.”

Spacewalking is widely considered the most dangerous assignment in orbit. Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano, who operated the station’s robot arm from inside during Friday’s spacewalk, almost drowned in 2013 when his helmet flooded with water from his suit’s cooling system.

“Everyone ought to be sending some positive vibes by way of airwaves to space for these two top-notch spacewalkers,” Dyson said early in the spacewalk.

Meir, a marine biologist making her spacewalking debut, became the 228th person in the world to conduct a spacewalk and the 15th woman. It was the fourth spacewalk for Koch, an electrical engineer who is seven months into an 11-month mission that will be the longest ever by a woman. Both are members of NASA’s Astronaut Class of 2013, the only one equally split between women and men.

Pairing up for a spacewalk was especially meaningful for Koch and Meir; they’re close friends. They’re also both former Girl Scouts.

It took two decades for women to catch up with men in the spacewalking arena.

The world’s first spacewalker on March 18, 1965, Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, died last week. NASA astronaut Ed White became the first U.S. spacewalker less than three months after Leonov’s feat. Women did not follow out the hatch until 1984. The first was Soviet cosmonaut Svetlana Savitskaya. Sullivan followed three months later.

Friday’s milestone spacewalk was the 421st for team Earth.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

We’re Having the Wrong Mental Health Conversation

America’s mental health crisis is rooted in recent history that led not only to inadequate facilities and resources for those with illnesses, but also to a lack of understanding on a broader scale about the nature of the health issues. Another urgent problem inextricably linked to mental health is homelessness, given that not only do many people with psychological illnesses end up homeless due to a lack of options and resources, but that the conditions of living without adequate—or any—housing aggravate any mental health issues already present.

Psychiatrist and documentarian Kenneth Paul Rosenberg delves into these urgent topics in his latest book, “Bedlam: An Intimate Journey Into America’s Mental Health Crisis,” where he takes an objective look at the problem while interlacing the story of a nationwide system that failed his own sister, and including stories of others who’ve faced similar struggles.

Rosenberg, who is the featured guest on the most recent episode of Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer’s podcast, explains that part of the misguided drive behind closing down mental hospitals in the 20th century had to do with the idea that these institutions infringed on citizens’ civil liberties.

Related Articles

The Solution to Homelessness Is Staring Us in the Face

by Robert Scheer

“[In my book] I talk about a very brave family who spoke to me, Norm and Judy Ornstein, who unfortunately lost a son to serious mental illness,” Rosenberg says on the latest installment of “Scheer Intelligence.” “Judy said it better than anyone I’ve ever met. She said, ‘My son died with his civil liberties intact.’ He was able to live a life that was really substandard by any measure, where he was really living with his mental illness.

“I would have to say for my own sister,” the psychiatrist adds, “that it was very, very hard to get her treatment. And it’s very, very hard to keep someone more than three days or four days without a court order, without a conservatorship. And those things are changing. And at the same time, we must safeguard our personal autonomy, we must safeguard people’s civil liberties.”

Another factor was the discovery and popularization of psychiatric drugs that led many to believe hospitals and other facilities would become redundant.

“The thing that informed the whole deinstitutionalization,” Scheer says, “was that there were these new magic drugs—I’m not talking about illegal drugs, I’m talking about prescription drugs—that could basically solve the problem. And one of the revelations in your book is not only that the first generation of those drugs didn’t work very well—aside from the fact that you couldn’t get people to take them on a regular basis, but they just were not the panacea that had been predicted.

“There is no magic bullet of drugs for dealing with serious mental illness,” the Truthdig editor in chief concludes in conversation with Rosenberg about the book.

There is, however, one crucial thing, in tandem with other changes to laws and increased medical research, which the psychiatrist profoundly believes will change the course of this terrible episode in American history in which we’ve turned our most vulnerable members quite literally onto the streets.

“We have to realize that this is not someone else’s problem,” Rosenberg says. “The most important thing we have to do is have a conversation. … This is our problem that we have to confront. And I think the way to do it, trite as it sounds, is to have a conversation that we have not been having. And have it be a conversation not about the other, but about ourselves.”

Rosenberg also worked with producer Peter Miller to create a documentary series based on his book, also titled “Bedlam,” which will air on PBS in April. Below is a clip about the upcoming series.

Listen to the full discussion between Rosenberg and Scheer about the reasons behind the mental health crisis plaguing the U.S. as well as a possible path forward for the country. You can also read a transcript of the interview below the media player and find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

—Introduction by Natasha Hakimi Zapata

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of “Scheer Intelligence,” where the intelligence comes from my guests. And in this case, a man with great credentials, Kenneth Paul Rosenberg. He’s a fellow of the American Psychiatric Association; he’s associated with New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, and he’s a practitioner in his own right. And he’s a Peabody Award-winning filmmaker dealing with some of the topics of mental illness that we’re going to be dealing with. But he has written a book that–it’s called Bedlam, and I’ll let him explain the title, the historical roots–An Intimate Journey Into America’s Mental Health Crisis. And it’s also an important part of the homelessness crisis. And interestingly enough, we’re doing this recording from the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, and we’re very close to the epicenter of this whole mental health, homelessness crisis.

And in your book, you kind of single out the LAC + USC, L.A. County + USC Medical Center. And then you have the L.A. County Jail. And kind of an important part of the theme of this book can be wrapped up in a statement you make in it, where the sort of the two main places we have for dealing with health, mental health, are those two institutions–and they’re woefully inadequate to the task. So why don’t we just begin with that?

Kenneth Rosenberg: First of all, thanks so much for having me on the show. It’s a pleasure and an honor to be here, frankly. You know, they say we’ve deinstitutionalized people; I think we have trans-institutionalized people. We’ve sent them from the asylums–which were dreadful, no question–to the streets and the jails and the prisons, which are probably more dreadful. And we haven’t really done them a very good service. And as you say, where you are recording me from this moment is the epicenter of this nation’s crisis. I think, as a positive note, because of things that are changing in Los Angeles, it may also be the epicenter of change. But it’s definitely the epicenter of the crisis.

RS: You know, it’s interesting you should say that, because I’ve also done interviews on this show with people from the United Way; we’ve dealt with a movie called The Advocates, which is a very good inside look into these tents of the homeless. And the issues overlap in the sense that people have mental problems. And in your book, you’re very careful to point out we don’t really know the degree to which this is nature or nurture, to the degree that you’re born with it or it’s inflicted.

But one thing we do know is if you end up on the streets–and many people, I forget the number from the Federal Reserve, it’s something like 40% are a paycheck away from not having the ability to pay their rent. We live in an economy of increased, you know, for the last 40 years, of income gap between the well-off and this mass at the bottom. And the question is, that I had reading your book at first–there are many things to discuss. But one I had was, yes, you use the statistic 25% of the people in our vast homeless population here in L.A. and up in San Francisco, two incredibly prosperous cities, are there–are defined as seriously mentally ill. But the question then is, did they get that way by living on the streets? Or are they on the streets because they are that way?

KR: That’s a great question. I mean, if any one of us lived on the streets, Lord knows that we would probably, our sanity would be challenged if not completely lost. If any of us were exposed to the trauma of living on the streets, and the violence of living on the streets, and the drugs of living on the streets, and the alcohol abuse, and all those things, our minds would not be healthy. So I think it’s a great point.

However, it is estimated that 25% of males who are living on the streets, and 40%–four-zero percent–of women who are living on the streets, are there virtually because of their serious mental illness, because that’s the option that we’ve given them. We’ve taken away the hospitals, we’ve taken away the asylums, we’ve made the community mental health centers few and far between, so that people with mental illness end up on the streets, and they also end up in jails.

We’ve made having a mental illness largely a crime, so that at least 25% of people in the jails and prisons today have a serious mental illness. One in four. And we see, again, we’ve trans-institutionalized people; we’ve put them in–we had put them in dreadful asylums, and now we put them in dreadful institutions. And by the way, I think the jails and the prisons are doing the best they can, but law enforcement is not a medical treatment. And people didn’t go into law enforcement so they could be social workers, nor were the jails built to be mental health centers.

RS: So let’s just trace this deinstitutionalization, which as you point out just means we–instead of the big mental hospitals, I forget their names–one was Pilgrim here in California, I think, I forget the others–

KR: Yeah. Yeah, Pilgrim.

RS: And as I recall, when this all happened–and it’s interesting that California should be the epicenter. In part, some people think it’s the homelessness center because we have a better climate. But there is a real connection between the two in the history of the state. The deinstitutionalization as I understand it started here in California, and it started with a kind of an alliance between fiscal conservatives represented by Ronald Reagan and the Reagan Revolution when he was governor, and civil liberties organizations like the ACLU and others that were very concerned that people were being locked up in these dreadful institutions, they didn’t have basic rights, they were just being warehoused.

And the thing that informed the whole deinstitutionalization was that there were these new magic drugs–I’m not talking about illegal drugs, I’m talking about prescription drugs–that could basically solve the problem. And one of the revelations in your book is not only that the first generation of those drugs didn’t work very well–aside from the fact that you couldn’t get people to take them on a regular basis, but they just were not the panacea that had been predicted. But even after you trace the development of what you call the “me-too” drugs, all the different kinds of ways–and there is no magic bullet of drugs for dealing with mental illness, serious mental illness.

KR: Yes. Well, as you point out, the problem is multifactorial. And you know, it’s been said many times before that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. I think that the people who wanted to restore the civil liberties of people with serious mental illness meant well. The people who wanted to close down the institutions meant well. And the people who wanted to build community mental health centers in the sixties, that were completely ill-equipped to deal with people with serious mental illness, meant well. But it didn’t end up so well. The funding dried up; the facilities, community mental health centers, were not really equipped to deal with them, and people did end up on the streets.

There’s no Republican, Democratic governor to blame for this. Everyone was complicit. And I think as a society we’ve been complicit. We have said, you know–we’ve thrown up our hands. And you mentioned pharmacology–the medicines are very helpful, they’re very wonderful. But as you pointed out, Bob, there is no panacea, there is no magic bullet. The brain is very, very complicated, and the medicines are not what they should be. The molecules we use for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are effective, but they have serious side effects. And essentially, they’re molecules that are 70–seven-zero–70 years old. That’s not what we should be seeing in medicine, right?

So I think that it’s multi-factorial. But if you had to draw it down into one phrase or one sentence, I think as a society we just haven’t given a damn. We’ve really let the people with serious mental illness live on the streets, you know, go to the jails, go to the prisons, take outdated drugs with serious side effects. And said, you know, we wash our hands of it. I think, again, the ACLU has meant well; I think civil liberties and personal autonomy are the foundations of our American democracy. We should safeguard them. But we have to think about that, because in some ways, we’ve taken the expedient, the easy solution. We’ve said, you know, it’s their right to be mentally ill, it’s their right to live on the street, it’s their right to live and die on the streets. And in some ways, that’s kind of like the easy way out, without really caring and taking care of our neediest citizens.

RS: Well, that’s what makes your book so incredible, I think. Because you–you do what all of us should do; you say the other is not the other. And in your personal case, the other, this severely mentally impacted person, is your sister.

KR: Indeed.

RS: And the book is, as you call it, an intimate journey. And it’s an intimate journey where you encounter other professionals. This is what makes it, I think, a compelling read, because it’s not some abstraction. It begins with somebody you care a great deal about–your sister–and she cannot be reached by well-meaning parents, by the existing social system or so forth. You take us through the journey of others, people of means, hard-working taxpayers and so forth. You meet some fellow psychiatrists and other professionals who are in this business precisely because they’ve met the other in their own family.

And the conversation about, whether it’s about the homeless or the subset of severely mentally impacted people, it only becomes this reality when you have had a child or a sibling involved. And you weave that through the book. So you don’t let us off the hook, that these are just crazy people. Which is the way they were presented, it was throughout literature; you do an excellent job of tracing the history of mental illness, you know, and the way mentally ill people were dismissed, chained, abused, beaten. And then, yet, you bring it back to your sister–you don’t want your sister treated in that way. But that is what happens at some critical moment.

KR: Yeah, I think that’s–thank you for saying that. You know, 50% of us need some psychiatric care at some point in our lives. And serious psychiatric care, not just because we’re having a bad day or something like that. One in five families, maybe one in four families, have a family member with a serious mental illness. And that doesn’t even take into account substance abuse, which affects 15 to 20% of the population in terms of a lifetime prevalence. This is not about the other. We’d like it to be about the other, because we have such great stigma, such great shame.

You know, and I’m Jewish; we, my parents and family talked about it as a shanda, a great shame that cannot be discussed. And I think that’s just wrong. We’d like it to be the other, but it’s us. And when we realized it’s us, we realized it’s our family members, then we could not turn our back on ourselves and our family members, and wash–and allow society to wash their hands of the problem.

So I think it’s, you know, a very good point you make: It is not the other, it is us. And it doesn’t matter who the heck you are. You know, I’ve seen billionaires who have their children die on the streets, who can’t get their kids out of jail. It’s not an issue of any socioeconomic class–although poverty is a factor, and people of color are unfairly, you know, represented in people with serious mental illness because of the traumatic life and the stress of their lives. But still, it’s something that affects everyone, and it doesn’t matter who the heck you are. You know, you can’t manufacture a drug if you’re the richest person in the world. You can’t create a hospital bed for your relative if none exists. This is a problem that we have to address as a society, and no one is insulated from it.

RS: Well, let’s just trace the history very briefly. But we stopped with–OK, there was a movement in the post-war period–I mean, after there had been some movies that were quite sensationalist. I don’t know, I think one was The Snake Pit or something, and–

KR: The Snake Pit, Cuckoo’s Nest, yeah. I mean, brilliant films, but they–

RS: No, but I mean, and they had this whole idea that the traditional way of the big mental hospitals was barbaric, was awful. And then we grabbed this quick solution of outpatient, or some magic drug, and so forth. And that took hold. And I think it takes hold for the very reason that you outlined in your book. You’re not talking about your own child. Because if you’re talking about your own child, you want to know whether the new solution is actually working, and you check on it. And what we did is, as you say, we said, OK, that’s taken care of. And in fact, you bring us something I did not know before I read your book. But that when Medicare was written into law–and Medicaid–there was a restriction that none of this money could be used for mental illness treatment, unless it involved an institution that had fewer than 16 people. Correct me if I’m wrong.

KR: That’s correct, and we’re trying to change that in California. You have a lot of people in the Department of Health who are trying to change that. But it’s a–

RS: Right, but I want to focus on that, because the ideological blindness was that–

KR: It’s crazy.

RS: –that any larger institution would by its very nature become repressive, would violate the freedom and care about these people. So what do we end up, though? We end up–I’m teaching at a university here, the University of Southern California–we’re surrounded by people, many of whom obviously–I’m not talking about our student body, I’m talking about on the edges of our campus, where we have one of the–by the way, one of the larger private police forces making this campus supposedly safe from these other people. And they’re living there in what, under cardboard, with little pup tents or something. And there’s this incredible fear of this other. And yet periodically, I’ve had some friend or other come looking for their nephew, looking for their cousin. Right? And say, Bob, do you know where this street is, or something.

So I want to get at that kind of studied indifference, because you trace policy. And most of the policy is to sort of put people out of sight, out of mind, and not to raise serious questions about whether it’s working, how is it working, you know. And that’s what your book challenges, and I want to tip people off. They may not agree with everything in this book, because at the end, you really challenge the idea–and I challenge it every day when I drive home from school here. I live downtown, and I see people on the streets talking to themselves, yelling, deranged. And I–there’s a chapter, I forget the title of it. But you ask, did that–is that civil liberties? Or is that madness that’s indulged?

KR: Yes, exactly. I talk about a very brave family who spoke to me, Norm and Judy Ornstein, who unfortunately lost a son to serious mental illness. And they’ve spoken about it publicly, but in the book they were so kind and generous to talk about it with me. And basically, Judy said it better than anyone I’ve ever met. She said, “My son died with his civil liberties intact.” He was able to live a life that was, you know, really substandard by any measure, where he was really living with his mental illness.

And that story is, like every family story, is very complicated and nuanced. But I would have to say for my own sister, that it was very, very hard to get her treatment. And it’s very, very hard to keep someone more than three days or four days without a court order, without a conservatorship. And those things are changing. And at the same time, we must safeguard our personal autonomy, we must safeguard people’s civil liberties.

But we have to ask ourselves a very difficult question. Those people you drive by, Bob, when they’re screaming to themselves, when they’re sleeping under a bridge, is that really the life they deserve? Are we just turning our back on them? And are we really doing them a service by not offering them and urging them to have treatment, so they can make informed decisions?

Because, you know, there’s something in the medical terms called anosognosia, which means that you don’t know that you have a serious mental illness. Now, it’s a very slippery slope. And we have to, you know, again, I think the civil libertarians are absolutely right that we have to be very, very careful about this. But when the person that has a psychotic process that is taking over their brain, that is preventing them from knowing that they are in fact sick–whether it’s a form of denial, whether it’s just the stigma, or whether it’s a brain process, at the end of the day it doesn’t matter–their lives are really miserable. And we have to ask ourselves, is that really civil liberties? Is that the kind of society we want to live in? Where we say, ah–you know, it’s their problem.

But as you say, it’s our problem, because many people I know have family members who live on the streets who are seriously mentally ill. And it’s very, very hard to challenge that, very, very hard to get them help. And it’s a complicated question, but there now are some procedures to get people help. There’s something called assisted outpatient treatment–very controversial, but it uses what we call therapeutic jurisprudence. Having a judge who knows about these things say to the person, look, either you go to a hospital, or you get treatment. You know, very, very simple. And we have to provide the proper treatment; it has to be welcoming treatment, it has to be humane treatment. It can’t be these dreadful asylums that we used to throw people into. But still, I think that our citizens who are sick deserve treatment, deserve an opportunity to live healthy lives.

RS: Well, I think that’s the critical thing here, is whether we give a damn. And it’s interesting. As you mentioned, California is the epicenter of this, and it comes with a big cost to this society. Here you have two of the richest cities in the world in San Francisco and Los Angeles. And if you go to this new building, the Salesforce building in San Francisco, by day it’s the center of the new wired, internet world, and you know, apps and everything else. By night it’s like a campfire, an illusionary campfire, for homeless people. And just stretched out, block after block after block.

And you see that in L.A.; we have this incredible gentrification of the downtown, building all over the place and everything, and yet you have these miles of despair that rival, I think, anything I’ve ever seen anywhere in the world. I mean, it’s unbelievable. You know, Bedlam is the title of your book; I mean, that’s what comes to mind. Well, the two can’t–they both can’t exist side by side. The fact is, this idea of the city of the future, which is how San Francisco–well, certainly New York has always been the city of the future. San Francisco, L.A.–they can’t coexist with this intense army of the dispossessed. They can’t. I mean, it’s unsafe, it’s costly–

KR: Yeah. Well, it’s a housing problem, right? I mean, above all else, these are cities that you point out in which housing is extremely expensive. And homelessness is fundamental–

RS: Right. Well, I want to separate the two and yet connect them. Because–and first of all, I want to go with your positive theme. The voters here in California did vote for–both in L.A. in the city, and on the county level–for spending money on building housing for the homeless. You know, they took that path rather than the traditional one of trying to zone them out of existence, and warehouse them somewhere far away where you don’t have to see ’em. So there is actually that sense that we need to get on top of it. And even, you know–not only even, but the United Way and business groups have led that battle. So that’s true.

However–however, they run up against the problem that your book addresses. Yes–get the housing. Yes, put people in that housing. And we featured a movie on this show, The Advocates–work with them. As you point out, it’s labor intensive. Psychiatry is not simple. Mental health is not simple. There isn’t a magic bullet. You say if you have supported housing, oh, you better have people that also watch what’s going on and helping people. And it seems to me what your book is demanding is the kind of seriousness of purpose that you exhibited towards your sister. Right?

KR: Yes. Well, we–

RS: The question is whether we’re going to exhibit that towards these people out there. Right? That are not related to us.

KR: Yes. We need wraparound services. We can’t just say, put them–give them a home, we need–ah, there’s very good diversion plans in California, but then what we need is follow-up. Because we could say, you know, we’re not going to put you in jail because you’ve committed a petty crime; we’re going to give you treatment, that’s the proper thing. But then we have to provide the treatment, and we have to provide the housing and the wraparound services–the mental health services, the pharmacology, all of those things that are really essential.

And I think that’s just really part of a civilized society. It also will save us money. It’s not cheap to put people in jails for mental health treatment. It’s not cheap to have 1500 men in Twin Towers Jail, mainly because they have a mental illness. It’s not cheap to treat people in emergency rooms. All of that’s extremely expensive. So we probably would save money and do the right thing at the same time.

RS: Well, you should give us some of those statistics about it not being cheap. Because actually, we’ve chosen the most expensive way of dealing with this. First of all, if you just do neglect, and people dying on the street, you’re also–you know, I hate to put it in these terms, but you’re also destroying your most valuable real estate. And you’re making an unstable society, because–

KR: Well, it’s very expensive. I mean, some people–you know, there are homeless mentally ill people who could cost a million dollars. Gavin Newsom, when he was Lieutenant Governor–you know, he’s in the book, and I’ve spoken to him many times about this–you know, realized that there were certain individuals in San Francisco, when he was mayor, who had cost literally a million dollars for the community. Because they were just getting the most expensive treatments, and it’s very expensive to keep someone in jail. A leading cost for the police is dealing with people with serious mental illness; a leading cost for people in jails and prisons is providing just the drugs.

The drugs alone are extremely expensive. And of course, when you’re in jail, when you’re in prison, my God, if you don’t have a mental illness to begin with, how traumatic and how difficult it is. But for someone with a serious mental illness, they decompensate severely. And I think it’s fair to say this is not the plan of law enforcement. This is not what they, as I said before, it’s not what they went into law enforcement to do. It’s not necessarily what they’re good at. They want to, you know, protect the public, not be treating people with serious mental illness.

RS: I should interrupt you just to read from your book. You point out, I’m quoting: “America’s three largest jails–the Twin Towers in Los Angeles, Chicago’s Cook County Jail, and Rikers Island in New York City–serve as the country’s three largest psychiatric inpatient facilities.”

KR: Yes.

RS: That’s a statement in itself of societal madness. As you point out, they were–

KR: I would have to agree. I mean, our jails and prisons are now the de facto asylums. And as bad as the asylums were, they’re probably worse.

RS: And as you point out, the irony of this is that it was done in the name of what, at least on the conservative side of saving money, right? Ah, you know–

KR: You know, I’m not questioning anyone’s reasons. I think that, you know, President Kennedy had good intentions when he speeded up the tearing-down of the asylums and created community mental health centers. I think Ronald Reagan, I would say had good intentions, because he saw the community mental health centers were wasteful, and they weren’t treating the sickest patients. So I think there were good intentions, and I think it’s a real mistake, and we’ve done this throughout the history of this discussion with people with serious mental illness. We’ve blamed people; we’ve blamed the doctors, we’ve blamed the police, we’ve blamed this one or that one. It’s really the illness, the illness is the enemy. But we also have to blame ourselves for our neglect of, as I say, our neediest citizens, who we’ve really turned our back on.

RS: Well, yeah, and I just want to make one correction right here. When I was saying that they were taking up expensive real estate, it wasn’t that I was equating human life with the cost of a block of real estate. What I was saying is there’s a contradiction in what people have in mind for cities. We care more about cities, all over the world the urbanization of population is moving very rapidly. And the fact of the matter is–and it comes across very clearly in your book–the two can’t coexist easily.

KR: It’s a great point. It’s not good for anyone to have a man or a woman living under a bridge and eating out of a garbage can. That is not what we want for our culture, is it.

RS: Right. But there isn’t a–you know, the easy alternative of jailing, that turns out to be more expensive, more inefficient. So I just want to get to a point that I think is very important in your book. We don’t have the luxury–it’s like people talking about climate change–we don’t have the luxury of ignoring it. Well, that’s true of how we’re ordering life in our cities. For one thing, the income inequality is not going away.

We’re going to have more poor people, and your book makes very clear, at some point you can’t really distinguish between the mentally ill and the poor. They’re sort of thrown in the same pot, you know, and there’s a general deterioration of life. And, you know, you can’t have a gated community that you know, cuts right down the middle of a city; it doesn’t work, and the numbers get larger. And there isn’t–again, I have to stress this. What I got from your book–you’re the expert, but what I got from the book is there isn’t likely to be some magic bullet, you know.

KR: No, there isn’t. And the point about poverty, just to note that–it’s not that the poor and people with mental illness are the same. It’s that poverty itself is a very traumatic thing, and exacerbates and stresses the human system. And if you have a vulnerability to having a serious mental illness, and you can’t pay the rent, and you don’t have a house to live in, and you can’t feed yourself or your children–my God, you know, that makes your life so much more stressful. And it opens up a window on all kinds of anxieties, depression, and so forth and so on.

RS: Well, all you have to do right now–I mean, when I leave here, you know, instead of going over to Staples Center to watch the Lakers game tonight I’m going to do. But, you know, normally I would go a bit south, what, six blocks away from a very glitzy scene. And I’m the middle of, again, Bedlam–that title of your book–I mean, it’s unbelievable. You know, and if you try to function–which people do; there are buildings here, you know.

In fact, one of the great contradictions with the Occupy Movement is when they came to crush Occupy here in Los Angeles, they said it was unruly, there were crimes against people, there was–you know, everything was going on, people were not using bathrooms and so forth. And I remember being there that night when they, you know, they militarily closed down the Occupy site, you know. But I had parked my car five blocks away, in the middle of the scene you’re describing. Far worse than any encampment around City Hall–but out of sight, you know. And there were people there, it was a wild scene of screaming, there was violence, and actually there were some murders committed that night. Five, six, seven blocks away from this City Hall thing, which was by comparison quite calm.

And so I want to end with, we’re really–how do we make this issue more visible? And what you use in your book is a literary device of introducing us to people that first of all, you and some of the other people you’re describing care a great deal about. So we learn their histories, and then we can’t just dismiss them as crazy people, and you know, lock them up or get rid of them or put them out of sight. And I just wonder whether journalism has failed in this regard. And even, not just journalism, but all the other institutions. I think here at the University of Southern California, in fact, we are administering the biggest hospital to deal with this issue, certainly in the western United States. And yet, it’s not a focus of attention. What we have done is actually gentrify the area, put up walls, and create indifference. And you know, you’re functioning in New York City; isn’t that what Manhattanization has all been about?

KR: Yeah, I think the most important thing to happen–there’s many important things. We have to change the laws, we need medical research. The cost burden of serious mental illness exceeds that of cancer, cardiac disease, all noncommunicable diseases. We have to realize that this is not someone else’s problem. The most important thing we have to do is have a conversation. And I’m very grateful, honestly, for you having me on the show, because this is exactly why I wrote the book. We have a film coming out on PBS on Independent Lens in April 2020 that will actually go into this in great detail. It lets us know that this is not something we could get habituated to, we could turn our back on, we could say–oh, that’s someone else’s problem. This is our problem that we have to confront. And I think the way to do it, trite as it sounds, is to have a conversation that we have not been having. And have it be a conversation not about the other, but about ourselves.

RS: Well, you raise a question, though. And there’s a phrase, “the throwaway people.”

KR: Yes.

RS: And, you know, I’m not going to get very religious here or anything. But one message, you know, we talk about being, people, some people talk about being a Christian nation. And you mentioned, you know, an accurate criticism of part of Jewish life, the keeping the shanda, you know, don’t make a shanda for outsiders. And you also have sort of lines where you want the gift of grandchildren and all that sort of thing. But you know, the fact of the matter is, there’s a part of Christian teaching that is stronger, maybe, than any other religious strain on the other.

You know, if you think of the tale of the parable of the Good Samaritan, for example, and that the standard is not how you treat those closest to you that you know. In your case, your sister, you did step up as best you could. But how do you treat these anonymous people? Do you recognize their life force, their fears? You know, and from my experience covering the homeless issue, I found terrified people. I found most people who didn’t go into, even when shelters existed, they were afraid to go into the shelters. You know, they thought they were–

KR: Right. We talk about them as violent, but they’re often the victims of violence, not the perpetrators. And by the way, you know, I think all religions are, you know, overall extremely kind and generous. But in every culture, religious or otherwise, we have really stigmatized mental illness. And I think that, you know, we all have done that, and that’s really what this conversation that we’re having in the book and the film, that you and I are having right now, is trying to do: to humanize the situation, and to stop stigmatizing people as being crazy or the other.

RS: Yeah. Well, finally, I do want to talk about the real danger in any problem thinking there is an easy solution. And then when you employ it and you don’t get the results, you get angry, you say it’s wasted money, you know, or so forth. And the great thing about your book–one of the great things, I think it’s very–first of all, it’s really so interesting that it’s so accessible. You know, this is not like reading some, you know, turgid medical text or something, but at the same time, it’s not simplistic. You get across that progress in this area is going to be difficult to come by. That it’s like knitting; you have to be patient, you have to get–you even have somebody who you quote saying she likes mental–I forget the way she put it, but I could understand–yeah, go ahead.

KR: Yeah, it was a psychiatrist who said that she finds psychiatry with people who are psychotic fascinating, because you know, this whole other world is extremely interesting to her.

RS: Well, not only is it another world, but it is also our world. We all have this capacity, we all have tensions. You know, I saw myself in some of these scenes, you know. And I think an important message of your book is a reminder, there is not a quick and easy solution. That doesn’t mean that these other steps that are taken are not meaningful. You know, and you mentioned you have some true heroes in this book. I mean, you had mentioned the wife of the New York mayor, I’m blocking on her name, the first lady of New York–

KR: Oh, Chirlane McCray, of course, yes.

RS: Yeah, and you know, when you talk about Monte’s sister, who’s–

KR: Oh, Patrisse, one of my heroes, of course.

RS: Yeah, and she’s here in L.A. Why don’t you–why don’t we end by talking about people who are really making a difference. That this is not a hopeless situation, this is a situation where if we were more focused, if we used our resources wisely, if we cared about the outcome, we actually could make great inroads here. And as a result, we’d all be winners, because you know, everyone will tell you they don’t enjoy being in the downtown area of any city with people constantly yelling at them, or scaring them in one way or another. So progress on this issue is in all our interests. But you know, what you’re asking for in this book is sort of a seriousness of purpose, a patience, you know; not looking for the quick fix. And watching a movie like The Advocates, which is all about people looking into these tents, engaging people in conversation. And people should be prepared for that if they’re really serious about it. This is going to be roll up your sleeves and, you know, work hard at it.

KR: No, I think that when, you know, as you’ll see in the PBS film that comes out in 2020 that I directed, you know, there are some real heroes in this. There are many heroes; I could, it would take me an hour to list them all. But in the film and in the book, we talk about them: Patrick Kennedy, a friend of mine; Adrienne Kennedy, who’s the president of the board of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. In Los Angeles, Patrisse Cullors, Jonathan Sherin, Colin Dias, Dr. McGhee, who’s there–so many people who are really trying to change it.

And I think that we are at a hopeful moment. This is a watershed moment when we’re having the conversation, when laws are being changed. We had a parity bill that passed in 2010; we have, you know, many acts that have occurred. You have a governor now in Gavin Newsom who cares deeply about this issue. So, I think that we’re at a positive turning point, but your point is very, very well taken, Bob. It’s not going to happen overnight. We’re not going to cure mental illness in a heartbeat. It’s not all going to go away with the best of governors, the best of presidents, the best of, you know, legislation, it’s not going to change, so we have to be patient. But we are patient with other diseases.

Cancer hasn’t gone away, but we still make progress. HIV hasn’t gone away, but we fight for the rights for people with HIV to live healthy and dignified lives. We have to do the same for our citizens with mental illness. And as we say over and over again, it’s not someone else; it’s our family members, it’s ourselves. We may not want to think about it. We may not want to realize it, but it’s everyone we know and love is often affected by this in some way, shape, or form.

RS: Yeah, I just want to follow up on one thing you just said about making progress. You do point out that the pharmaceutical industry is not the best agency alone for that–

KR: Of course not. Well, you know, I can’t blame them. They’re a business; their responsibility is to their stakeholders, and they need to make money, and they need to make quick money. I understand that. But we need as a society to be responsible for our neediest citizens. So we need university-based research, we need medical research that looks into the root causes of serious mental illness and comes up with novel treatments. And then the pharmaceutical companies will see an opportunity to make money, and then they’ll get involved. But I think to rely on pharmaceutical companies to do basic science research is a terrible thing.

It’s not their job, and it’s a business. As a society, we need to say this is important, we’re going to make it a priority, and march in the streets. And aside from Patrisse Cullors and a few others, there have been very few people who are willing to march in the streets on behalf of those with serious mental illness. That will change things.

RS: I just want to throw in, and then we’ll conclude this, a little editorial on my own part. Because I have tried as a journalist to cover this story. I spent some time in the psych emergency ward in San Francisco General, I’ve done that down here in L.A. and so forth. And I remember every time I tried covering this issue, I’d come back and say, you know, this is not an exercise in freedom that these people are doing down there in the streets. This is a weird romantic notion out of the sixties, or I don’t know what, that you know, that the crazy are really freer, or so forth–no. There is a situation, and you show it in your book, that the guy curled up and his sister lies down on the floor. She’s Patrisse, I think it is, right?

And she, you know–that sometimes you can’t do anything but hold someone. And that you know, there’s something about the–I don’t know, it’s a controversial point on which to end. But one way people get off the hook–and I’ve seen that in some of the recent television reporting, they’ll find somebody saying, oh, I like it down here on the street, and I’m not going anywhere, and this is my way of being free.

But when you walk those streets, and when you enter those shelters and so forth, that is not a prevalent mood. What you have are people who don’t even comprehend, or very often, where they are and what’s happening to them. And then when the police come, they get really frightened and they fear the worst, and they’re traumatized by it. And your book captures that. And I think that’s an important reminder. And then just the–the way we handle it, oh, let me give the guy some change. Or you know what, instead of engaging in conversation, which is the real challenge of figuring out where these people are coming from, it is a great human test.

And you know, as I say, I’m going to wrap this up, but Bedlam: An Intimate Journey Into America’s Mental Health Crisis–and you know what, surprisingly enough, it’s not a depressing book. Because actually, and the last point you made, good things are happening. I mentioned that here in L.A.–and you mentioned our governor willing to put, Gavin Newsom willing to put resources toward this, or coming up with, you know, Third Way programs. You know, no, it’s not civil liberties, but on the other hand you don’t have the right to just throw someone into, you know, put them back and change the way it was done for hundreds of years.

And that it requires–I’m going to say the great takeaway from your book is that it is informed by your sister; that you would not have written this book just based on your professional psychiatric knowledge. And that’s what you tell us from the first page, that had you not had someone you love fall into this, or be in this–be one of them, the other–you would not have, in fact you would not have become a psychiatrist.

KR: That’s absolutely right. I decided when I was 14 to become a psychiatrist, because my sister was then 20, 21, the age when psychosis hits. And she, you know, became very, very sick. And I saw that there has to be a way out of this, and that’s why I wanted to become a psychiatrist. And in fact did, and the book and my film are dedicated to my beloved sister, who unfortunately died from this illness. But hopefully her death is not completely in vain. And we can really change things with, you know, with this dialogue that you and I are having tonight.

RS: Well, that’s a good positive point on which to end it. And the book, as I say, and at the end the book introduces us to people who are doing something about this, from New York to L.A. And so read it, Bedlam: An Intimate Journey Into America’s Mental Health Crisis. The author is Kenneth Paul Rosenberg, who is also a highly lauded and talented filmmaker, and his film I guess is coming out in April. Maybe we’ll keep broadcasting it until it comes out on PBS. Thank you, again. Our producer here at the University of Southern California–which, you know, I didn’t mean to put down our institution either. I think their efforts in running a county hospital are well-intentioned. There’s a lot of discussion about that. Our producer here is Sebastian Gruber. The producer for Scheer Intelligence overall is Josh Scheer, who found this book and this subject. And we’ll be back next week with another edition of “Scheer Intelligence.”

Blast at Afghan Mosque Kills 62 at Prayer

KABUL, Afghanistan—An explosion rocked a mosque in eastern Afghanistan as dozens of people gathered for Friday players, causing the roof to collapse and killing 62 worshippers, provincial officials said. The attack underscored the record-high number of civilians dying in the country’s 18-year war.

Attahullah Khogyani, spokesman for the governor of Nangarhar Province, said the militant attack wounded 36 others. He said it was not immediately clear if the mosque was attacked by a suicide bomber or by some other type of bombing.

“Both men and children are among those killed and wounded in the attack,” he said.

Related Articles

The U.S. Government Doesn’t Care About Afghan Women

by Maj. Danny Sjursen

#NeverForget the War in Afghanistan

by Sonali Kolhatkar

The Myth America Tells Itself About Afghanistan

by Maj. Danny Sjursen

Sediq Sediqqi, spokesman for Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, strongly condemned the attack on his official Twitter account. “The Afghan government strongly condemns today’s suicide attack in a mosque in Nangarhar province,” he tweeted.

“The Taliban and their partners heinous crimes continue to target civilians in time of worship,” he added.

No one immediately claimed responsibility for the attack, but both the Taliban and the Islamic State group are active in eastern Afghanistan, especially Nangarhar province.

However, Zabihullah Mujahid, the Taliban’s spokesman in a statement condemned the attack in Nangarhar and called it a serious crime.

Zahir Adil, spokesman for the public health department in Nangarhar Province, said 23 of the wounded were transferred to Jalalabad, the provincial capital, and the rest were being treated in the Haskamena district clinic.

The violence comes a day after a United Nations report said that Afghan civilians are dying in record numbers in the country’s increasingly brutal war, noting that more civilians died in July than in any previous one-month period since the U.N. began keeping statistics.

“Civilian casualties at record-high levels clearly show the need for all parties concerned to pay much more attention to protecting the civilian population, including through a review of conduct during combat operations,” said Tadamichi Yamamoto, the U.N. secretary-general’s special representative for Afghanistan.

The report said that pro-government forces caused 2,348 civilian casualties, including 1,149 killed and 1,199 wounded, a 26% increase from the same period in 2018.

The report said 2,563 civilians were killed and 5,676 were wounded in the first nine months of this year. Insurgents were responsible for 62 percent. July to September were the deadliest months so far this year.

Efforts to restart talks to end Afghanistan’s 18-year war picked up earlier this month, just weeks after President Donald Trump last month declared the talks “dead,” blaming a surge in violence by the Taliban that included the killing of a U.S. soldier.

U.S. peace envoy Zalmay Khalilzad visited Pakistan and met with the Taliban’s top negotiator, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar. Baradar is a co-founder of the hard-line Islamic movement and was head of a Taliban delegation to the Pakistani capital.

U.S. officials said Khalilzad was only in the Pakistani capital to follow up on talks he held in September in New York with Pakistani officials, including Prime Minister Imran Khan. They insisted he was not in Pakistan to restart U.S.-Taliban peace talks.

In western Herat province, six civilians including four children were killed Thursday when their vehicle was hit by a roadside bomb, said Jelani Farhad, spokesman for the provincial governor. He added that five other civilians were wounded in the attack in the Zawal district.

October 17, 2019

Democrats Have No Answer for Trump’s Anti-War Posture

I hate to say I told you so, but well … as predicted, in the wake of Trump’s commanded military withdrawal from northeast Syria, the once U.S.-backed Kurds cut a deal with the Assad regime. (And Vice President Mike Pence has now brokered a five-day cease-fire.) Admittedly, Trump the “dealmaker” ought to have brokered something similar before pulling out and before the Turkish Army—and its Sunni Arab Islamist proxies—invaded the region and inflicted significant civilian casualties.

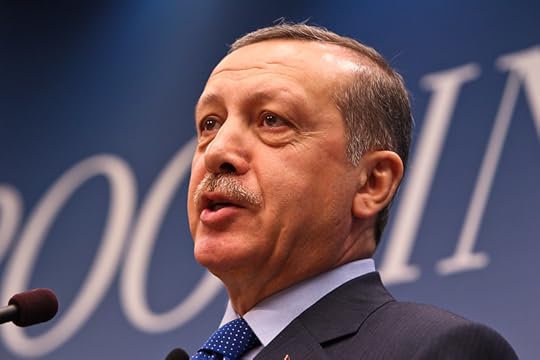

One must admit that a single phone call between Trump and President Erdogan of Turkey has turned the situation in Syria upside down in just over a week. The Kurds have requested protection from Assad’s army, Russian troops are now patrolling between the Kurds and invading Turks, and the U.S. is (for once) watching from the sidelines.

The execution has been sloppy, of course—a Trumpian trademark—and the human cost potentially heavy. Nonetheless, the U.S. withdrawal represents a significant instance of the president actually following through on campaign promises to end an endless American war in the Mideast. The situation isn’t simple, of course, and for the Kurds it is yet another fatalistic event in that people’s tragic history.

Still, while the situation in Northeast Syria constitutes a byzantine mess, it’s increasingly unclear that a continued U.S. military role there would be productive or strategic in the long term. After all, if Washington’s endgame wasn’t to establish a lasting, U.S.-guaranteed Kurdish nation-state of Rojava, and it hardly appeared that it ever was, then what exactly could America expect to accomplish through an all-risk, no-reward continued stalemate in Syria?