Chris Hedges's Blog, page 102

November 16, 2019

Trump Pardons 2 Army Officers Accused of War Crimes

WASHINGTON—President Donald Trump has pardoned a former U.S. Army commando set to stand trial next year in the killing of a suspected Afghan bomb-maker and a former Army lieutenant convicted of murder for ordering his men to fire upon three Afghans, killing two, the White House announced late Friday.

The commander in chief also ordered a promotion for a decorated Navy SEAL convicted of posing with a dead Islamic State captive in Iraq.

Related Articles

Whitewashing War Crimes Has Become the American Way

by Maj. Danny Sjursen

Trump Has a Soft Spot for American War Criminals

by

Putting the Warriors on Terror on Trial

by Maj. Danny Sjursen

Hina Shamsi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project, said the actions amounted to an “utterly shameful use of presidential powers.”

“Trump has sent a clear message of disrespect for law, morality, the military justice system, and those in the military who abide by the laws of war,” Shamsi said in a statement.

White House press secretary Stephanie Grisham said in a written statement that the president is responsible for ensuring the law is enforced and that “mercy is granted,” when appropriate.

“For more than 200 years, presidents have used their authority to offer second chances to deserving individuals, including those in uniform who have served our country,” she said. “These actions are in keeping with this long history.”

Trump said earlier this year that he was considering issuing the pardons.

“Some of these soldiers are people that have fought hard and long,” he said in May. “You know, we teach them how to be great fighters, and then when they fight sometimes they get really treated very unfairly.” At the time, Trump acknowledged opposition to the possible pardons by some veterans and other groups and said he could make a decision after trials had been held.

One of the pardons went to Maj. Mathew Golsteyn, a former Green Beret accused of killing a suspected bomb-maker during a 2010 deployment to Afghanistan. Golsteyn was leading a team of Army Special Forces at the time and believed that the man was responsible for an explosion that killed two U.S. Marines.

He has argued that the Afghan was a legal target because of his behavior at the time of the shooting.

The second pardon went to 1st Lt. Clint Lorance, who had been convicted of murder for ordering his soldiers to fire upon three unarmed Afghan men in July 2012, killing two. Lorance has served more than six years of a 19-year sentence at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Trump also ordered a promotion for Special Warfare Operator 1st Class Edward Gallagher, the Navy SEAL convicted of posing with a dead Islamic State captive in Iraq in 2017. Gallagher was in line for a promotion before he was prosecuted, but he lost that and was reduced in rank after the conviction.

Last month Adm. Mike Gilday, the U.S. chief of naval operations, denied a request for clemency for Gallagher and upheld a military jury’s sentence that reduced his rank by one step. One of Gallagher’s lawyers, Timothy Parlatore, said then that ruling would cost Gallagher up to $200,000 in retirement funds because of his loss of rank from a chief petty officer to a 1st class petty officer.

Gallagher ultimately was acquitted of the most serious charges against him. Grisham said the reinstatement of the promotion was “justified,” given Gallagher’s service.

“There are no words to adequately express how grateful my family and I are to our President – Donald J. Trump – for his intervention and decision,” Gallagher said in a statement on Instagram. “I truly believe that we are blessed as a nation to have a Commander-in-Chief that stands up for our warfighters, and cares about how they and their families are treated.”

Parlatore said Friday that his client had received a telephone call from Trump and Vice President Mike Pence informing him of the news.

Golsteyn’s trial by court-martial initially had been scheduled for December but was postponed until Feb. 19 to give attorneys more time to prepare.

In a statement Friday, Golsteyn said his family is “profoundly grateful” for Trump’s pardon.

“We have lived in constant fear of this runaway prosecution. Thanks to President Trump, we now have a chance to rebuild our family and lives. With time, I hope to regain my immense pride in having served in our military,” Golsteyn said.

His defense attorney, Phillip Stackhouse, said he was “confident we would have prevailed in trial, but this action by the President expedited justice in this case.”

___

Associated Press writer Lolita C. Baldor contributed to this report.

November 15, 2019

Fighting the Unprecedented ‘Proletarianization’ of the Human Mind

“The Age of Disruption: Technology and Madness in Computational Capitalism”

A book by Bernard Stiegler

Why is political hope becoming defunct in so many young people today? This is the question Bernard Stiegler poses in his new book, “The Age of Disruption: Technology and Madness in Computational Capitalism.” Early on, he quotes the words of a teenager whose nihilistic outlook, he claims, is representative of the zeitgeist of contemporary youth:

When I talk to young people of my generation […] they all say the same thing: we no longer have the dream of starting a family, of having children, or a trade, or ideals. […] All that is over and done with, because we’re sure that we will be the last generation, or one of the last, before the end.

These despairing words serve as a leitmotif to Stiegler’s fervent deconstruction of economic, political, and spiritual malaise. He dauntingly refers to the present’s “absence of epoch” — i.e., today’s lack of any significant political ethos. This “absence of epoch,” during a time of critical ecological changes, is why so many have been left disaffected, fast becoming (in Stiegler’s heavily italicized prose) “mad with sadness, mad with grief, mad with rage.”

Stiegler’s voice is by turns imperious, inveighing, confessional, and compassionate. His philosophical analysis — when the rhetorical wind in its sails slackens a bit — is intricate and brilliant, although grasping it requires some knowledge of the rhizomatic conceptual network that supports his argument, its tendrils often recognizable precisely by their italicization.

Stiegler’s origins as a philosopher perhaps explain his sense of urgency. In 1976, he tried to hold up a bank in Toulouse — his fourth bank robbery — only to be arrested, tried, and (thanks to a good lawyer) given a five-year prison sentence. It was during this incarceration that the erstwhile-jazz-café-owner-turned-bank-robber discovered philosophy, subjecting himself to a strict daily regimen of reading and writing (some of his notes from that period continue to feed into his books to this day). Following his release from prison, Stiegler, with the support of Jacques Derrida, began to teach philosophy. Thus was launched the improbable career of one of the most influential European philosophers of the 21st century.

Stiegler recounted his prison experience in his 2009 book “Acting Out,” and in “Age of Disruption” he extensively revisits this conversion narrative: an upward climb from physical and intellectual imprisonment toward liberation. Quoting a beautiful phrase from a letter by Malcolm X (who had a similar conversion experience), Stiegler observes that prison gave him the “gift of Time.” He describes a typical day of study in his cell: “In the morning I read, after a poem by Mallarmé, Husserl’s ‘Logical Investigations,’ and, in the evening, Proust’s ‘In Search of Lost Time.’” The following morning, “after a cup of Ricoré chicory coffee and a Gauloises cigarette,” he would “prepare a synthesis” of what he’d read the day before. It was this monastic, autodidactic program that enabled Stiegler to reach perhaps his most crucial insight — the discovery that “reading [is] an interpretation by the reader of his or her own memory through the interpretation of the text that he or she had read.”

That’s a simple enough idea on the surface, but it conceals depths of implications. To understand why, we need to consider Stiegler’s theorization of technics. In his ongoing project “Technics and Time” (1994–), Stiegler lays the foundations for all the philosophical books he has produced. He posits that technics (technology conceived in the broadest terms, encompassing writing, art, clothing, tools, and machines) is co-originary with Homo sapiens: what distinguishes our species from other life forms is our reliance on constructed prostheses for survival. Drawing on the work of paleoanthropologist André Leroi-Gourhan and historian of technology Bertrand Gille, Stiegler argues that tools are the material embodiments of past experience. Building on this insight, and incorporating the perspectives of Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida, as well as the views of influential but little-known French philosopher Gilbert Simondon, Stiegler claims that technics plays a constitutive role in the formation of subjectivity, opening up — and, if badly used, also closing down — horizons of possibility for individual and collective realization.

The role of technics in human life is cemented by what Stiegler calls “tertiary” memory. Here we return to the intimate kinship between the interpretation of a text and an interpretation of one’s own memory, Stiegler’s major insight from his time in prison. Technics, which makes these forms of interpretation possible in the first place, acts as a “third” memory for human beings because it encodes the past experience of others, and thus always remains external to the subject. Nonhuman life-forms have access to two kinds of memories: “primary memory,” or genetic information inscribed in the DNA code, and “secondary memory,” which is the acquired memory of an organism with a sufficiently complex nervous system. While secondary memory accumulates over an organism’s lifespan, it disappears with the death of the individual. Human beings, uniquely among higher life-forms, are prosthetic organisms that pass on their accumulated experience by means of exosomatic or “tertiary” memory, in the form of tools (especially written language).

So how does all of this relate to our present politico-economic malaise? Stiegler believes that digital technology, in the hands of technocrats whom he calls “the new barbarians,” now threatens to dominate our tertiary memory, leading to a historically unprecedented “proletarianization” of the human mind. For Stiegler, the stakes today are much higher than they were for Marx, from whom this term is derived: proletarianization is no longer a threat posed to physical labor but to the human spirit itself. This threat is realized as a collective loss of hope.

A key text for Stiegler is, predictably, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s “Dialectic of Enlightenment” (1944), which has long remained the flagship of critical theory. Adorno and Horkheimer anticipated a rise in cultural “barbarism,” spearheaded by Hollywood cinema and the so-called “culture industry.” Today, billions of people are reliant on information technology that reduces culture to bite-sized chunks (the thought-span of a Tweet), and which is used primarily for marketing purposes by a monopoly of tech giants. Stiegler believes that such a situation threatens to dissolve the social bonds that embed individuals in collective forms of life. Most worrying of all, social networks are becoming the main source of cultural memory for many people today; Facebook’s “Post a Memory” feature, for instance, is one superficial manifestation of the deeper long-term impact on subjectivity and identity.

“The Age of Disruption” attempts to unearth the historical and philosophical roots of the current politico-economic sickness. Drawing on Peter Sloterdijk’s “In the World Interior of Capital” (2013), Stiegler argues that the risk-taking ethos of modern capitalism has created a generalized spirit of “disinhibition” that is a threat to law, morality, and governance. It is, in essence, a secular nihilism that Sloterdijk found powerfully expressed in the “rational madness” of Raskolnikov in Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment,” who is willing to sacrifice others in the pursuit of his own greatness. Closer to home, we can glimpse the same overweening sociopathy in the likes of Bernie Madoff, Jordan Belfort, and the crews of speculators who gave us the 2008 global market meltdown. This nihilistic disinhibition is exacerbated by a second form of secular madness Stiegler traces: the conviction that rationality essentially consists of mathematical calculation. Ever since Descartes and Leibniz, European civilization has been driven by a dream of a mathesis universalis, the achievement of a hypothetical system of thought and language modeled solely on mathematics. If this dream sounds like ripe material for dystopian fiction, it is, for Stiegler, our very own present.

The above summary cannot do full justice to Stiegler’s painstaking deconstruction of the roots of “computational capitalism” — a phrase he uses to join these two interrelated forms of rationalized madness. Stiegler firmly believes that a distinction must always be upheld between “authentic thinking” and “computational cognitivism” and that today’s crisis lies in confusing the latter for the former: we have entrusted our rationality to computational technologies that now dominate everyday life, which is increasingly dependent on glowing screens driven by algorithmic anticipations of their users’ preferences and even writing habits (e.g., the repugnantly named “predictive text” feature that awaits typed-in characters to regurgitate stock phrases). Stiegler insists, however, that authentic thinking and calculative thinking are not mutually exclusive; indeed, mathematical rationality is one of our major prosthetic extensions. But the catastrophe of the digital age is that the global economy, powered by computational “reason” and driven by profit, is foreclosing the horizon of independent reflection for the majority of our species, in so far as we remain unaware that our thinking is so often being constricted by lines of code intended to anticipate, and actively shape, consciousness itself. As Stiegler’s translator, the philosopher and filmmaker Daniel Ross, puts it, our so-called post-truth age is one “where calculation becomes so hegemonic as to threaten the possibility of thinking itself.” [1]

One should not be misled into thinking that Stiegler is a philosophical Luddite who seeks to do away with digital technology. Far from it: the digital, like any technology, is double-edged, and is useful so long as it remains merely a tool. While his book does not propose practical solutions (Stiegler promises to address some of these in a future work), it does seek to inspire a collective realization of the extent to which future memory is currently being shaped by algorithmically determined and profit-driven information flow. Stiegler asks us to consider how much of our lives we wish to delegate to market-tailored computational rationality.

Atypically for a writer of contemporary philosophy, Stiegler does not shirk from sharing his personal struggles: obsessions with death, suicidal impulses, fears of madness. In this regard, his style closely resembles the heavily italicized prose of Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard. The following passage is from the opening of Bernhard’s 1982 novel, “Wittgenstein’s Nephew” (trans. David McLintock):

In 1967, one of the indefatigable nursing sisters in the Hermann Pavilion on the Baumgartnerhöhe placed on my bed a copy of my newly published book “Gargoyles” […] but I had not the strength to pick it up, having just come round from a general anesthesia lasting several hours, during which the doctors had cut open my neck and removed a fist-sized tumor from my thorax. […] I developed a moonlike face, just as the doctors had intended. During the ward round they would comment on my moon face in their witty fashion, which made even me laugh, although they had told me themselves that I had only weeks, or at best months, to live.

And the following is one of several confessional admissions grafted onto the rhizomatic network of Stiegler’s philosophical argument:

At the beginning of August [2014], finding myself increasingly obsessed by death, that is, by what I projected as being my death, and by the latter as my deliverance, waking up every night haunted by this suicidal urge, I called, somewhat at random, this clinic where I had received treatment. I asked for urgent help, seeming, so I thought, to be suffering from some kind of early dementia …

Although the Bernhard passage comes from a novel, albeit an autobiographical one, the comparison is suggestive. Stiegler confesses to having tried and failed to write fiction during the first months of his incarceration, producing “countless pages now lost, to tell a story that never took any form other than the same fruitless effort to write.” A sentence like this would be right at home in a Bernhard novel, and had Stiegler been successful as a novelist, he might well have written the sort of tortured monologue of obsessive phrases and motifs at which Bernhard excelled. Indeed, Stiegler is drawn toward this kind of frantic repetitiveness even in his philosophical exposition: the Arabic invocation, “Inshallah,” is used several times, and words and phrases such as “absence of epoch,” “madness,” “barbarians,” et cetera, recur almost like chants. But this comparison also signals a key difference in intention: while both writers often turn to thoughts of death and endings, Stiegler, despite his proclivity for portentous clauses in italics, remains committed to emerging out of (in his words) “the mortiferous energy of despair that we are accumulating everywhere.” The same cannot be said of Bernhard, whose outlook was willfully mortiferous, as he might have put it.

Despite his urgent talk of apocalypse, chaos, and epochal endings, despite the rampant italics of philosophical admonishment, his arguments are enunciated by a humane and compassionate voice. As he confesses, he often dictates his thoughts while cycling in the countryside, and his wife, Caroline Stiegler, subsequently transcribes the recordings (I can only assume all those italics are audible). Stiegler’s traversal of the philosophical genealogies of Western rationality and madness, and his urge to rethink their metastable composition in an all-too-rational digital world devoted to the algorithmic reduction of all aspects of existence, allows the presently unhoped-for to at least become thinkable. What Stiegler hopes for most of all is to get his readers to “dream again” — to become politically hopeful (without the scare quotes). The last words may be left to Heraclitus: “One who does not hope for the un-hoped for will not find it: it is undiscoverable so long as it is inaccessible.”

This review originally appeared on the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Deval Patrick Had Chris Christie’s Nod … a Year Ago

Here’s a political riddle: Why would a GOP operative like former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie want to give a Democrat like Deval Patrick a boost in the 2020 presidential race? And why would Christie pointedly name-check Patrick, the onetime Massachusetts governor who confirmed Wednesday that he was indeed making a run at the White House, a full year before Patrick announced?

Christie made this public display of prescience on Oct. 20, 2018 at Politicon, that annual power-huddle of pundits on the take, in downtown Los Angeles. Among the gems Christie scattered across a series of L.A. Convention Center stages, shared by the likes of Carter Page, Dennis Rodman and Tucker Carlson, was his response to moderator and MSNBC analyst Elise Jordan’s question about whether he’d spotted any formidable challengers to President Trump’s second term rising from Democratic ranks:

Deval Patrick. So, I want you all to think about this, ’cause no one’s talking about him right now. But like two years from now, if he really runs, you’re gonna look back at this and go, “Holy shit, at Politicon, Christie said Deval Patrick — and none of us were thinking about him!”

Nice flourish by Christie, there, in seeding Patrick’s future run while patting himself on the back for his own prognostication skills. Christie was so complimentary of Patrick, and so ready with his reasons as to why Patrick would make an “articulate” (a surefire sign that this is a politician of color being spoken about by a white pundit) and worthy opponent for Trump, it was almost as though his commentary were more rehearsed than extemporaneous:

I want you to think about Deval Patrick, and here’s why: Not of Washington, D.C., and never been there. Two-term executive from a significant state: Massachusetts. And very articulate and smart. Deval Patrick, I think, would give Donald Trump the best challenge, because he could challenge him on executive background, he can challenge him in terms of his ability to have gotten things done in government, and he’s a very articulate spokesman for his point of view. And he will not carry any of the Washington baggage with him that any of these United States Senators will. [Emphasis added.]

While it could be the case that he was expressing his sincere beliefs about Patrick’s chances at the polls, it’s typically not a good idea to take the words of a seasoned politician like Christie at face value. That, and Christie is still pursuing a not-at-all-mutually beneficial relationship with President Trump, in which all the benefit goes to President Trump.

Meanwhile, if Democratic candidates of any description need the Washington Post’s backing more than Christie’s in order to make their way through the already contentious and crowded 2020 field, it’s not looking good for Patrick.

The mystery of what, if anything, Christie stands to gain from boosting Patrick may be solvable only by Christie himself. But he may actually have dropped a hint about a broader motive that could serve his party at that same Politicon panel when he said:

I guarantee one other thing: If the Democrats nominate a sitting United States senator for president, they will lose and lose easily. There is no way Kamala Harris, Corey Booker, Elizabeth Warren, Amy Klobuchar, Kirsten Gillibrand [could win]. Forget it! Trump will eat them alive!

Of note is how that above description now applies to sitting Democratic senators and 2020 candidates Warren, Klobuchar, Booker and Harris, as well as to sitting independent Sen. Bernie Sanders. As for what their status as current office-holders has to do with their chances at beating Trump, Christie let that stand as an apparent given without overt justification. But politicians have been known to do that sort of thing.

Watch Christie in action in the video below from Politicon 2018 (video by Kasia Anderson):

A Crash Course on How to Handle Homelessness

I really discovered homelessness for the first time when I left my job at an upscale Hollywood radio station in 1987 to work at a downscale downtown newspaper.

Hollywood certainly had its homeless people, but at that time, in that place, their condition seemed minor, temporary, manageable: street kids, runaways, a smattering of burned-out hippies. Nothing that a little counseling, a little rehab, a little assistance in reconnecting with family members probably couldn’t fix easily enough.

It was certainly nothing systemic. Or so I thought, wrongly. What I’ve learned since is that the issue is far more complex than I could possibly have imagined. There are almost as many causes of homelessness as there are homeless individuals. Their homelessness may not just be a status they temporarily experience; it can become an existential condition, a syndrome they have fallen into that must be addressed incrementally, not a problem that can simply be solved in one swift, bold stroke. Bookshelves are groaning with 10-year plans that failed to deliver, if they were ever implemented at all.

I would eventually discover that it is simply not true that everyone wants to get off the street, clean up, submit to a conventional regimen. Whatever the professional advocates tell you, seasoned social workers know better. There are homeless individuals who genuinely are “service-resistant,” but that implies more agency and volition than many homeless street people actually possess. Even those who sincerely want to escape their homelessness simply may never be able to do what is necessary to regain their autonomy and self-sufficiency.

Liberals and progressives blame Darwinian social policy and the ravages of capitalism. Conservatives blame an indulgent society and personal moral failings. But imposing such an ideological overlay is profoundly unhelpful and leads inevitably to a false binary choice: Either more money or more discipline is needed. A more honest approach recognizes the need for both. Building shelter and providing support services demands more public investment than we historically have been willing to make, but not tending to the plight of people living on the street can no longer be an option for any community. It denotes not respect for their rights, but neglect of our obligations. As a practical political matter, we cannot continue asking the public for more funding without delivering something tangible in return. We must find an ethical and constitutional way to bring the homeless population in off the street.

* * *

When I joined the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, I got “woke” to the issue pretty fast. The Herald’s once-grand, Julia Morgan-designed building was located at 11th and Broadway, what we used to call the “ass-end” of downtown. It stood barely four blocks from the official boundary of skid row, a 50-square-block area bound by Third and Seventh Streets on the north and south, and by Alameda and Main Streets on the east and west.

In that era, there was no LA Live. There was no Staples Center. There was no new and improved Convention Center. There was only blight, neglect, decay and human wreckage on a scale I could never have imagined, and the local government seemed to be doing nothing about it. There, homelessness was an existential condition, signifying a greater pathology of severe illness, disability and official neglect.

By design, skid row had been left to rot by the city for decades; the policy was containment, not eradication. The strategy called for the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency to subsidize commercial and market-rate residential development in the area, with a token affordable-housing element to grease the approvals. The city would blunt political opposition to the resulting gentrification by throwing a few bucks to the skid row social-service agencies to keep them pacified and hopefully even win their support. The media would play its part by boosting the poverty agencies and their leaders with puffy human-interest features while promoting all the shiny new developments in the business and real estate news. But nothing really changed for the impoverished residents of skid row.

Downtown at that time was represented by Councilman Gilbert Lindsay, the self-proclaimed “Emperor of the Great Ninth District.” Gil was notorious for promoting new development at the expense of providing for displaced populations and offsetting the loss of affordable housing units. He actively resisted bringing more social services to skid row, insisting it would only attract more homeless and discourage the kind of big-ticket skyline he hoped would be his legacy.

In 1988, the 88-year-old Lindsay suffered a stroke but ran for reelection the next year, seeking a seventh term. His endorsement interview with us was a pathetic display. Mentally, he was clearly out of it; his girlfriend, some 50 years younger, perched on his knee for the entire meeting. He was reelected anyway. The following year, he suffered another stroke and died in office. Several years later, his family (represented by Johnnie Cochran) sued the girlfriend for ripping off the estate and won a $235,000 judgment. A 10-foot monument to the “Emperor” stands today in front of the Convention Center.

To say that city leadership was somewhat lacking in those twilight years of Mayor Tom Bradley’s long tenure would be an understatement.

I was shocked and sickened by what I saw downtown. A few months after joining the Herald, in a column titled “Los Angeles Doesn’t Care Anymore,” I had written:

The 1982 film “Blade Runner” has become the catch-all metaphor for the degraded future of urban life in Los Angeles. … The inescapable conclusion after living and working here is that Los Angeles, for all its purported affluence, glamor and sophistication, is becoming a city that is not unable, but unwilling, to care for itself. … On every street I drive, bag people are sleeping on benches, slumped in doorways, or huddled on the sidewalk. … On the radio, their voices plead for shelter and jobs. … I read about them being shuffled from the City Hall lawn to abandoned public buildings to vacant-lot “camps.” A county supervisor proposes to ship them out to a rusty hulk anchored in the LA harbor. One councilmember wants to truck them out to a military base, another would send them to Terminal Island. The city attorney sues the county over the problem.

I concluded: “The larger problem is that some time back, we collectively made an informal, unstated, but nevertheless binding decision to give up trying to make the city work. … The “Blade Runner” analogy actually has it backwards. In the film, frustrated replicant creatures yearn for human love and companionship. The inhabitants of today’s bleak cityscape, by contrast, seem ready to embrace their dehumanized, violent future.”

I wrote that in 1987. “Blade Runner” was set in 2019; its dystopian future is now.

* * *

After the Herald folded in 1989, I joined the office of Third District County Supervisor Ed Edelman. I was now part of a political staff actually trying to do something for homeless people, not just another journalist writing about them.

Ed’s supervisorial district, like Lindsay’s council district, at that time included downtown and skid row. Unlike Lindsay, Ed sincerely tried to improve the situation, but he was constrained by fiscal and political realities. Southern California was sinking into a serious post-Cold War economic recession that was driving up the demand for services while reducing the tax revenue to pay for them. And the Board of Supervisors was then ruled by a conservative Republican majority with little appetite for social-service spending in any event.

Some of it, frankly, was also probably due to a lack of vision. We never tried to reimagine homeless policy or champion major systemic change. We nibbled around the margin, raising the temperature triggers to extend the operating days of cold-weather homeless shelters. We fought against budget cuts to health, mental health care and substance-abuse programs. We tried to publicly shame skid row markets out of further exploiting and immiserating their alcoholic clientele by discouraging their marketing of king-size malt liquor and cheap fortified wines.

We tried, but failed, to avoid a punishing reduction in the county’s general relief payments, the minimal amount of public assistance available to single adults. Over Ed’s objections, the board slashed the monthly relief benefit from a high of $350 in 1991 down to $221, roughly the 1981 level, by scoring the “in-kind” cash value of health services and discounting the monthly cash benefit by that amount. Had we only indexed that 1981 benefit for inflation, relief recipients today would receive $624 per month. As it is, their benefits are only worth $78 in constant 1981 dollars. It is a shame and a scandal that today’s board still has not increased that stipend.

We also struggled over how to identify eligible recipients and quality them for the federal Supplemental Security Insurance program, which would have paid disabled recipients around $900 a month, saving the county money while greatly boosting their public assistance. Today, the internet offers expanded opportunities to accomplish that. But imagine, as a disabled relief recipient, trying to hack your way today through this online bureaucratic thicket to qualify, or getting yourself to a county Department of Public Social Services office to seek help in person.

After a federal civil rights lawsuit redrew the formerly gerrymandered districts and made possible Gloria Molina’s election in 1991, a new Democratic majority emerged. One of its first actions was to settle a five-year lawsuit in which the city and county had sued each other over who bore principal responsibility for addressing homelessness. As part of the settlement, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority was created as a joint-powers agency to better coordinate homeless policy. After more than 25 years, about the kindest thing you can say is that it’s still a work in progress—and still has a lot of problems, even as the homeless count continues to swell.

Ed retired from public office in 1994 but continued his homelessness efforts as a consultant to the city of Santa Monica. I joined the staff of his successor, Zev Yaroslavsky (who had earlier also succeeded Ed in his City Council seat). Midway through Zev’s first term, a major fiscal crisis in the county’s health department, with the potential for actually bankrupting the county, took precedence over everything else for several years. That was followed by public safety and law enforcement priorities in the wake of 9/11. It wasn’t until 2004-2005 that the county board began to refocus on homelessness.

In spring of 2006, at the supervisors’ direction, County Chief Administrative Officer David Janssen put forward a comprehensive new Homeless Prevention Initiative (HPI) that identified the three principal factors fueling the homeless crisis: 1) the lack of permanent, affordable housing; 2) insufficient resources and funding to help clients achieve and sustain self-sufficiency; and 3) severe psycho-emotional impairment of clients related to, and exacerbated by, substance abuse and/or mental illness.

The plan, with $100 million in new and previously committed county funding, offered a number of recommendations to address the shortage of emergency, transitional and permanent housing, the need for stepped-up medical care and substance abuse treatment, and assistance in finding housing, qualifying for benefits and dealing with law enforcement and criminal justice issues around homelessness and poverty. Recognizing the regional nature of homelessness, the HPI proposed five regional stabilization centers, one in each supervisorial district, which were intended as alternatives to jail for minor offenses, and for those discharged from jail or county hospitals as an alternative to the street.

Unsurprisingly, none of it was ever implemented. There was so much community opposition that not one stabilization center ever opened, and the rest of the plan fell by the wayside. The money ended up being shoveled instead into existing programs and departments, where it disappeared without a trace.

A year or two later, Zev revived the homeless issue with a bold, and then largely untested, approach: He called it Project 50, a pilot program intended to identify 50 of skid row’s most vulnerable homeless people, those most at risk of dying on the street based on multiple factors including age, health, substance abuse, mental illness and years of living on the street, and bring them into permanent supportive housing (PSH.) It was a “housing first” harm-reduction model, recognizing that they might not be sober and they might still be using, but that it was unrealistic to expect them to clean up on the street before they were eligible to come in out of the cold. If they could get shelter and services first, it would be easier to address their health needs and break the vicious cycle of street, emergency room, court, jail and street again.

The premise was that there were so-called “shot-callers” who functioned as de facto influencers and leaders in the homeless community, and the strategy was that if we could work with them to help cull out and assist the hardest of the hardcore homeless street people, we could certainly succeed with less intractable cases. It would create a new dynamic that would justify scaling up the pilot program to encompass more homeless in other parts of the county.

We also believed it would be less expensive to convert or build, and operate, permanent supportive housing than to keep subsidizing the enormously expensive “frequent flyers” who couldn’t stay out of jail or the ER.

It took months of effort to break down the bureaucratic silos that hampered interagency, law enforcement and judicial cooperation. In addition, what we called the homeless-industrial complex—the network of conventional, long-established soup kitchens, drug and alcohol treatment programs, midnight missions, shelters, transitional housing, community-based health care nonprofits and single-room occupancy operators—fiercely opposed a radically new service model that threatened their standing. They argued that building PSH units would take too long and drain too much money from other vital services, and that housing substance abusers while leaving nonusers out on the street was unfair, sent the wrong message, and would ultimately prove unworkable. And they had the political clout to really monkey-wrench the plan.

Our early evaluations showed that most of the clients were able to stabilize and remain in shelter. With a place to live and better medical treatment, they had fewer brushes with the law and needed fewer costly ER visits. But scaling up proved much more arduous than we anticipated—it was more costly and sparked more community resistance, more law enforcement and judicial opposition when they saw the plan as all carrot, no stick. In 2009, after we had just suffered the worst recession since the Great Depression, the Board of Supervisors balked when asked to expand the successful pilot from Project 50 to Project 500.

That was the last major homeless initiative undertaken before I left the county near the end of 2015. But from August 2015 to February 2016, county agencies mounted yet another County Homeless Initiative and formulated yet another bold new action plan to combat homelessness. Following up on that plan, in November 2016, while the country was electing Donald Trump president, city voters opened their wallets and approved Measure HHH, a $1.2 billion city housing bond that promised 10,000 new permanent supportive housing units within 10 years. Some of us have been deeply skeptical of that boast for some time, and a recent city audit also threw shade on the promise.

Meanwhile, county voters in March 2017 subsequently approved another 10-year homeless funding measure, a countywide parcel tax, which will generate about $355 million a year to be earmarked for a combination of services, rent subsidies and new housing. Its most recently posted roster of funding recommendations largely covers the same well-trod ground as all the other plans and proposals. Will this money be spent any more efficiently and effectively than all those earlier efforts? Will it take us where we need to go?

I don’t think it will. When the city is spending a median cost of $531,000 to develop and construct a single unit of permanent supportive housing that was originally estimated to cost around $350,000-$414,000—and a recent Los Angeles Times analysis concluded that the percentage of street homeless suffering from mental illness and/or substance abuse was more than double LAHSA’s estimated 29%—it’s quite clear that there won’t be nearly enough money to build our way out of homelessness.

But my county experience also revealed a more fundamental dilemma that nobody in government even wants to talk about, much less attempt to address. Even if all the housing were somehow magically to be constructed, and all the social services were to be magically provided, there is no mechanism and no requirement to ensure that homeless people agree to use them. State legislation does not compel homeless people to seek or submit to treatment, even when available, and the courts have repeatedly rebuffed city efforts to conduct street sweeps and enforce vagrancy laws. Our public spaces on sidewalks, roadway medians, freeway ramps, underpasses, parks and public libraries are increasingly commandeered for the private use of homeless street people in ad hoc encampments that as a practical matter cannot legally be removed.

County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas and Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg, both former state legislators who are appointees to Gov. Gavin Newsom’s Homeless Task Force, have recently argued that California should recognize a right to shelter. Steinberg also argued in an op-ed that the homeless have a corresponding legal obligation to use it, but withering criticism from civil libertarians and homeless advocates backed them off calling for any obligation on the part of the homeless population to get off the street. Their revised policy position is now the same as homeless advocates have always taken: Build more housing, provide more services, and the homeless will avail themselves accordingly.

But what if they can’t, or won’t? Public officials will spend literally billions of dollars of public money with no visible progress on a problem that has been growing steadily worse for more than 50 years. The seeds were planted back in the early 1960s, when the deinstitutionalization movement emerged as purportedly more humane mental-health treatment than state mental hospitals or asylums; new wonder drugs promised to treat mental illness more effectively on an outpatient basis. Community-based group homes and board-and-care facilities offered a more intimate and natural setting than forbidding lockdown facilities where patients historically had been subjected to physical and sexual abuse. But virtually none of those promised community-based replacement facilities ever emerged.

In this respect, my own family has been fortunate. My grandmother’s younger sister, my mother’s aunt, was diagnosed with an incurable mental illness, probably schizophrenia, and was permanently institutionalized in Illinois in the 1930s. While I heard stories from my mother, I never had the opportunity to meet her Aunt Elaine, but I gathered that family members visited regularly, and although there were clearly some lapses, they found her generally well cared for. She apparently lived into her mid-80s. How long would a woman like her have survived on the street?

We must be prepared to create a new mental-health and wellness system for the 21st century, one that includes both community-based outpatient and congregate-living facilities as well as regional hospitals and long-term residential facilities, and we must be willing to accept the idea of reinstitutionalization. This will mean both a change of mindset and a change in state law. I don’t minimize the challenges of squaring respect for patient rights and individual liberty with the interests and needs of the larger community of which they are a part. But I believe it must be done.

Until we recognize that the most severely addicted, mentally ill or infirm among our street population not only cannot, and may never be able to, care for themselves—and are also unable to give informed consent even for their own lifesaving care and treatment—buildings alone will never solve the homelessness crisis that our own naiveté, indifference and cruelty has created.

Conflicting White House Accounts of 1st Trump-Zelenskiy Call

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump released the rough transcript Friday of a congratulatory phone call he had with the incoming president of Ukraine, holding it out as evidence that he did nothing wrong. Instead, the memorandum shows how White House descriptions of Trump’s communications with foreign leaders at times better reflect wishful thinking than the reality of the interactions.

As the House opened its second day of public impeachment hearings on Capitol Hill, Trump released the unclassified record of his April 21 call with then President-elect Volodymyr Zelenskiy. The document bears little resemblance to the paragraph-long official summary of the conversation that the White House released the same day as the 16-minute call.

The discrepancy highlights the gulf that often exists between the message that U.S. national security officials want to deliver to world leaders and the one that is actually delivered by Trump.

Related Articles

The U.S. Arming of Ukraine Is a Scandal on Its Own

by

Ralph Nader: Trump's High Crimes Go Way Beyond Ukraine

by

'Multiple Whistleblowers' Could Blow the Lid off Trump-Ukraine Call

by

For years, U.S. officials have stressed the importance of trying to support democratic norms and root out corruption in Ukraine, which has been fighting a war of attrition against Russian-backed separatists since Russia invaded and later annexed Crimea in 2014.

To that end, the official readout of the Zelenskiy call reported that Trump noted the “peaceful and democratic manner of the electoral process” that had led to Zelenskiy’s victory in Ukraine’s presidential election.

But there is no record of that in the rough transcript released Friday. Instead, it said Trump praised a “fantastic” and “incredible” election.

Current and former administration officials said it was consistent with a pattern in which Trump veers from — or ignores entirely — prepared talking points for his discussions with foreign leaders, and instead digresses into domestic politics or other unrelated matters. In the Ukraine call, for example, Trump praised the quality of the country’s contestants in a beauty pageant he used to oversee and compared Zelenskiy’s election to his own in 2016.

“When I owned Miss Universe, they always had great people,” Trump told Zelenskiy of his country.

The original readout also said Trump “underscored the unwavering support of the United States for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.” But there’s no indication of that in the rough transcript.

Likewise, the readout said the president expressed his commitment to help Ukraine “to implement reforms that strengthen democracy, increase prosperity, and root out corruption.” The word “corruption” is not mentioned in the rough transcript of the actual call.

Corruption did feature prominently in Trump’s second call with Zelenskiy on July 25, the call that helped spark the impeachment drama.

It’s highly unusual for a president to release the rough transcripts of calls with foreign leaders, which are generated by voice transcription software and edited by officials listening in on the call to ensure it is accurately memorialized. The official readout, by contrast, is issued as a news release meant to further foreign policy aims. It is typically the only public account of the calls that presidents have with their counterparts.

Several current and former administration officials told The Associated Press that the readouts of foreign leader calls that are routinely released are often pre-written, reflecting official U.S. policy and what National Security Council officials hope the leaders will discuss and the talking points they provide to guide the president’s conversations.

Those readouts are supposed to be revised after the calls to reflect what actually transpired. But that doesn’t always happen, according to seven current and former administration officials. They all spoke on condition of anonymity to describe internal deliberations.

The officials said that staffers tasked with writing the readouts typically haven’t listened in on the president’s calls and instead rely on others to brief them on the content. They are also often under a time crunch driven by NSC staffers eager to have the U.S. readouts come out before the other nations releases their own accounts. Sometimes, they said, the administration simply doesn’t want to recount everything discussed.

Asked why the rough transcript differs so much from the readout, White House spokesman Hogan Gidley said: “The president continues to push for transparency in light of these baseless accusations and has taken the unprecedented steps to release the transcripts of both phone calls with President Zelenskiy so that every American can see he did nothing wrong.”

“It is standard operating procedure for the National Security Council to provide readouts of the president’s phone calls with foreign leaders. This one was prepared by the NSC’s Ukraine expert.”

The current Ukraine expert at the NSC is Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, who testified to lawmakers last month behind closed doors and is scheduled to give public testimony on Tuesday.

The Obama administration made it practice to issue fairly general readouts that offered only broad details about the president and vice president’s conversations with foreign leaders. It was the Obama administration’s practice to assign someone who was listening in on the call to draft the readout for the media to ensure that what was being said about the call was accurate, according to a senior Obama administration official who took part in drafting readouts during that administration.

To write a readout that included things that weren’t discussed was “out of bounds,” said the official.

During the Obama and George W. Bush administrations, according to an official who worked on national security matters in both of those White Houses, it was practice to leave some details out of readouts to protect sensitive matters discussed on the call. But never were details or facts added or made up, the official said.

Ned Price, a former NSC spokesman under Obama and now director of policy at National Security Action, said it wasn’t uncommon for readouts to provide a “more artful and formal recap” of a foreign leader call.

“But it’s certainly not normal for the readout to be nearly entirely divorced from the reality of the call,” he said. “The discrepancies between the transcript and the readout in this case are profound.”

A former Trump White House official familiar with the current process said that readouts and rough transcripts are produced separately. The rough transcripts are created by those who listen in on the call and policy experts in the NSC. The readouts are prepared by media teams in the NSC and the White House press secretary’s office.

Typically, a draft readout of what Trump is expected to discuss is prepared by the policy team. In addition, talking points are prepared for president before the call, although Trump does not always use them, according to a former Trump White House official familiar with the process. The individual didn’t know whether the draft readouts were changed to reflect what is actually said, but said there is no “procedural step” that’s in place to ensure that the two are in agreement.

Another former Trump administration official familiar with the process also said draft readouts of calls were written ahead of time, but since Trump does not adhere to talking points for meetings or calls, “it’s a crap shoot on what is actually said.”

___

AP Writers Aamer Madhani and Jonathan Lemire contributed to this report.

Cap and Trade Can’t Be the Answer to Climate Change

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published.

Gov. Jerry Brown took the podium at a July 2017 press conference to lingering applause after a steady stream of politicians praised him for helping to extend California’s signature climate policy for another decade. Brown, flanked by the U.S. and California flags, with a backdrop of the gleaming San Francisco Bay, credited the hard work of the VIPs seated in the crowd. “It’s people in industry, and they’re here!” he said. “Shall we mention them? People representing oil, agriculture, business, Chamber of Commerce, food processing. … Plus, we have environmentalists. …”

Diverse, bipartisan interests working together to pass climate legislation — it was the polar opposite of Washington, where the Trump administration was rolling back environmental protections established under President Barack Obama.

Brown called California’s cap-and-trade program an answer to the “existential” crisis of climate change, the most reasonable way to manage the state’s massive output of greenhouse gasses while preserving its economy, which is powered by fossil fuels. “You can’t just say overnight, ‘OK, we’re not going to have oil anymore,’” he said.

But there are growing concerns with California’s much-admired, much-imitated program, with implications that stretch far beyond the state.

California’s cap-and-trade program was one of the first in the world, and it is among the largest. It is premised on the idea that instead of using regulations to force companies to curb their emissions, polluters can be made to pay for every ton of CO₂ they emit, providing them with an incentive to lower emissions on their own. This market-based approach has gained such traction that the Paris climate agreement emphasizes it as the primary way countries can meet their goals to lower worldwide emissions. More than 50 programs have been developed across the world, many inspired by California.

But while the state’s program has helped it meet some initial, easily attained benchmarks, experts are increasingly worried that it is allowing California’s biggest polluters to conduct business as usual and even increase their emissions.

ProPublica analyzed state data in a way the state doesn’t often report to the public, isolating how emissions have grown within the oil and gas industry. The analysis shows that carbon emissions from California’s oil and gas industry actually rose 3.5% since cap and trade began. Refineries, including one owned by Marathon Petroleum and two owned by Chevron, are consistently the largest polluters in the state. Emissions from vehicles, which burn the fuels processed in refineries, are also rising.

Critics attribute these increases, in part, to a bevy of concessions the state has made to the oil and gas industry to keep the program going. They say these compromises have blocked steps that would have mandated real emissions reductions and threaten the state’s ability to meet its ambitious goal of slashing its emissions 40% by 2030.

“There’s no question a well-designed regulation on oil and gas can have an effect,” said Danny Cullenward, a Stanford researcher and policy director at Near Zero, a climate policy think tank. “And that was traded away for a weak cap-and-trade program.”

Experts say cap and trade is rarely stringent enough when used alone; direct regulations on refineries and cars are crucial to reining in emissions. But oil representatives are engaged in a worldwide effort to make market-based solutions the primary or only way their emissions are regulated.

Officials with the state Air Resources Board, which oversees cap and trade, say those fears are exaggerated, that California’s program is doing what it needs to do and they can tweak it over time as needed. They point to the state’s overall drop in emissions since cap and trade began in 2013, even as its economy grew. They tout a host of other, more traditional climate regulations widely considered the best in the country.

But even with all those rules working together, California needs to more than double its yearly emissions cuts to be on track to meet the 2030 target. Meanwhile, the scope of the climate crisis and public pressure for strong regulations on fossil fuel companies have risen exponentially, even in the past year.

ProPublica delved into the mechanics of California’s cap-and-trade program, examining 13 years of political horse-trading, regulatory tinkering and industry lobbying to make sense of rising fears that it will not deliver the emissions reductions it is supposed to.

Five areas of concerns have emerged, some specific to the state’s program and some so fundamental that they raise questions about whether market solutions anywhere can do the work that is needed to take meaningful climate action while there is still time.

Cap and trade isn’t designed to hold any one company accountable.

It treats every polluting facility as if it were engaged in a giant group project. If enough companies in California reduce their emissions, the entire state gets an A, despite the slackers who didn’t pull their weight.

Here’s how it works: The state sets a cap, or limit, on CO₂ emissions from major polluters. The emissions under that cap are turned into permits, which each give the owner permission to release 1 metric ton of CO₂. Some are given out for free. Others are sold at auction by the state, and the funds are used for climate programs like electric vehicle rebates. Companies with more permits than they need can sell the extras, enabling other companies to buy the right to emit more, hence the trade.

Supply and demand helps determine how much each permit is worth. The cap gets lowered every year, theoretically applying increasing pressure on polluters to reduce emissions. There were 346 million available permits in 2019.

The program was born of a goal set in an executive order by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2005: for the state to lower its CO₂ emissions 25% by 2020. The following year, the Legislature put the Air Resources Board in charge of figuring out how to do it. Europe had already put into place a market solution, and a coalition of northeastern American states followed a few years later. In 2013, California launched its cap and trade program.

In 2016, the state hit its climate target four years early. But a government report concluded that the “cap is likely not having much, if any, effect on overall emissions,” and that reductions up to that point could be attributed to the 2008 recession, which slowed manufacturing, consumption and travel, as well as climate rules on renewable energy and vehicle standards.

The board predicted cap and trade would account for 30% of reductions in 2020 — but even after the state met its first benchmark, the board has not calculated how much the program has reduced emissions. This kind of study is hard to do; the only available analysis comes from Chris Busch of Energy Innovation, a climate policy think tank, who estimates that in 2015 and 2016, cap and trade was responsible for only 4% to 15% of the state’s reductions.

Erica Morehouse, a senior attorney at the Environmental Defense Fund, said California’s climate policy operates “as a team sport,” so it doesn’t matter how much of the heavy lifting is being done by cap and trade, as long as the state’s overall emissions stay under the cap. She said the other regulations alone can’t ensure California will meet the 2030 goal.

Now that cap and trade has been extended, the board predicts it will drive 47% of the CO₂ reductions in 2030, but critics wonder how much it will actually deliver. “It’s very difficult to have any faith in those projections,” given that the board hasn’t provided any “quantifiable evidence” of what cap and trade has achieved so far, said Kevin de León, former state Senate president and a candidate running for Los Angeles City Council.

What became most clear about the cap-and-trade program after it hit the first benchmark was how it can mask increases. According to a study from California researchers, almost all the CO₂ savings came from the electricity sector, which cut its use of imported power from out-of-state coal plants. It was low-hanging fruit, cheap savings that will be hard to repeat. The cut was enough to make up for emissions increases even within that sector; pollution from in-state power generation increased.

In fact, most facilities — 52% — increased average emissions within California during the first three years of cap and trade. These include cement and power plants as well as producers and suppliers of oil and gas.

The way market-based climate change solutions are set up provides loopholes and giveaways.

The success of any cap-and-trade program depends on how it is designed, starting with the cap. Experts warn that California set its early caps too high, allowing companies to buy permits and bank them for the future when the cap gets tougher. A peer-reviewed paper co-authored by Cullenward found that by the end of 2018, companies had banked more than 200 million permits — enough for almost as many tons of CO₂ as the total reductions expected from cap and trade from 2021 to 2030.

Though the purpose of the system is to apply financial pressure to industry, California gave away a bunch of free permits to companies they worried would face a competitive disadvantage compared with those outside the state. Those that couldn’t feasibly relocate had to buy permits at market price. A dozen industries, including oil and gas drilling, got most of their permits for free through 2020.

Refineries got the same treatment for the first few years, and the board planned to reduce the free permits in 2018. But when cap and trade was extended in 2017, state officials extended the same level of giveaways through 2030.

Cap and trade offers another way for polluters to avoid reducing emissions at their facilities: Many programs allow companies to cancel out some of their CO₂ by purchasing what are called offsets — paying to protect trees or clean up coal mine emissions in another city, state or country.

Studies raise serious questions about whether offsets in California’s program are canceling out the emissions they’re meant to. A ProPublica investigation highlighted similar concerns involving international forest offsets, which California supports. The biggest buyers of offsets are the worst polluters in the state, with oil companies at the top of the list.

Although state regulators have reduced the number of future allowable offsets, Barbara Haya, a University of California-Berkeley research fellow who studies carbon markets, said they could account for half of all emissions cuts expected to be achieved by cap and trade from 2021 to 2030, making the environmental integrity of the offsets paramount. Her research found that California regulators have oversold the climate benefit of offsets by underestimating how protecting one patch of forest pushes logging into other forests. The board stands by its calculations, and the two sides have continued to debate the issue.

Cap-and-trade programs usually include offsets, and “offset programs largely don’t work,” Haya said. At this critical moment, when so many people are developing market solutions, “it really worries me that we are going to implement policies that reduce emissions on paper and not in practice,” she said.

Among the most fundamental design elements of cap and trade is the price of carbon, ultimately what is supposed to force businesses to change. Economists have tried to find the lowest cost per ton that will move them. A new paper co-authored by Gernot Wagner, an economist at New York University, found that the accepted wisdom on carbon pricing — which aims for an initial cost of roughly $40 a ton that grows over time — is far from sufficient. His research concluded prices should start much higher, well above $100 a ton, and get lower over time as technologies improve and uncertainties about the extent of climate damage clear up.

California’s price is $17 a ton. Regulators can strengthen the program by setting a minimum permit price; in California, it’s currently $16. A World Bank report recommends prices of $40 to $80 by 2020 to be on track for the Paris climate goals. Only a handful of the world’s market programs meet that standard.

Stanley Young, the board’s communications director, said that it can take time for cap and trade to affect industries like oil and gas, and that the mere presence of a carbon price impacts corporate decisions in ways that aren’t always visible. Rajinder Sahota, an assistant division chief at the board, points to the fact that permit prices are climbing; state data shows they have increased from about $13 to $17 over the past three years. Sahota says that alone should serve as a warning signal to industry that one day, the cost to pollute will be unaffordable.

California’s oil industry has blocked efforts to make cap and trade tougher on them.

The Western States Petroleum Association, the main oil industry group in California, has lobbied on cap and trade every quarter since 2006, spending $88 million on it and other regulations. Records show the industry has advocated on virtually every aspect of its design, including offsets, fees and the allocation of permits.

Its biggest wins happened in 2017, when cap and trade was up for extension. Two bills aimed to make the extension contingent on forcing emissions reductions by restricting offsets and free permits.

One introduced by Sen. Bob Wieckowski tried to force banked permits to expire by 2020 and get rid of offsets. Vox called it “the most important advance in carbon-pricing policy in the U.S. in a decade. Maybe ever.” But it needed a two-thirds majority vote to pass the Legislature, thanks to an oil industry-sponsored ballot measure from 2010 that reclassified many state and local fees as taxes. The measure had a huge impact on environmental regulations; the only viable bills now were those that could gain broad political buy-in. Wieckowski’s bill was viewed as too radical to support and never got a vote. He said he couldn’t even get a meeting with the governor about it.

The other bill, by Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia, proposed using cap and trade to limit the toxic gases that streamed out of smokestacks alongside CO₂. Garcia’s district in Los Angeles was among the most polluted in the state. Her bill made companies with rising CO₂ or toxic pollutants ineligible for free permits. In three months in 2017, Chevron spent $6.3 million lobbying against her bill and related regulations, while WSPA lobbied against both Garcia’s bill and Wieckowski’s. Each effort had a lobbyist who was a former state legislator.

Garcia’s bill had initial support from a crucial constituency: labor unions representing construction workers. That changed after Chevron promised the unions a five-year contract to retrofit its refineries — the result of a safety bill inspired by a 2012 fire at its Richmond facility, which sent thousands of people to the hospital with breathing problems. Cesar Diaz, who lobbied for the unions, said his organization supports climate regulation. Its opposition to Garcia’s bill had nothing to do with the Chevron deal, he said, but was inspired by fears that it would hurt the economy.

The defeats prompted Brown to step in to save the extension, holding closed-door meetings with moderate legislators and oil interests deep into the night, according to several sources with knowledge of the negotiations.

The industry’s influence became clear after articles revealed how draft language in the emerging bill matched a “wish list” from a lobbying firm working for WSPA. The list included tools to slow rising carbon prices and increased free permits for oil and gas among other industries — all things that ended up in the final bill and subsequent amendments. Brown later testified in a state Senate hearing, where he called it the most important vote of the legislators’ lives.

Brown, whose term ended in January, declined to be interviewed for this story. In response to ProPublica’s inquiries about cap and trade, Brown’s spokesman pointed to the broad coalition of environmental, academic and industry interests that supported the bill, and he emphasized that program is just one part of California’s extensive climate regulations.

Morehouse, the EDF attorney, said the oil industry may have won a few battles with the bill, but it “lost the war.” California has maintained an extremely ambitious 2030 target, she said.

It’s no surprise the oil industry advocates for its own interests, Morehouse said. “First they want no climate policy. Then they want it delayed as long as it can be. Then they want it to be basically meaningless,” she said. By the time the industry starts focusing on something like free permits, “you can actually start negotiating.”

WSPA, which opposes direct regulations, praised the extension’s passage as “the best, most balanced” solution, “the best available path forward for our industry in the toughest regulatory environment in the world.”

Dean Florez, an Air Resources Board member critical of the concessions made, said the industry supports the new program because it “figured out how to game the system.” The industry got almost everything it wanted, he said, leaving it “offset happy and surplus rich.”

More meaningful regulations are being sacrificed.

One of the industry’s biggest victories from the 2017 bill was a provision that prohibits new CO₂ regulations on refineries and oil and gas production. Earlier that year, the Air Resources Board had proposed a regulation to lower refinery emissions 20% by 2030. The bill killed that plan.

The bill also prevented local air districts from imposing regional caps on CO₂, heading off a five-year grassroots effort from Bay Area residents. Incensed by the Richmond refinery fire, they packed into hearings held by the Bay Area Air Quality Management District and waited for hours to speak.

The residents lobbied for a cap on CO₂ as a way to force reductions in other pollutants. Their plan was on the verge of approval, with a draft rule that local regulators hailed as an unprecedented “model for the state and nation to follow.” Then, the state cap-and-trade bill rendered it moot.

For the oil industry, the strategy of embracing market solutions to avoid more direct regulation extends far beyond California.

At an international climate conference last year, Shell Oil executive David Hone boasted he had written a key part of the United Nations’ Paris agreement that makes market solutions the primary way to deal with climate change. “The ideal for a cap-and-trade system is to have no overlapping policies,” he told The Intercept.

In Washington state, oil interests led by BP defeated a statewide carbon tax ballot initiative partly because the proposal didn’t include provisions to preempt other climate rules. InsideClimate News reported that BP helped derail an earlier attempt to pass the tax through the Legislature after the governor wouldn’t make certain concessions, like allowing its refineries to use offsets to lower their tax payments or prohibiting local governments from creating or enforcing their own climate regulations.

On a national level, Exxon Mobil, BP and Shell helped economists, environmentalists and bipartisan former politicians with the Climate Leadership Council design a federal carbon tax of $40 a ton — one that’s contingent on eliminating all other federal climate regulations on major polluters such as power plants and refineries. The council cites a report by an energy policy group that says the tax would help the U.S. meet its Paris targets.

“Exceeding the U.S.’s Paris goals is, of course, good and a terrific start. But it’s only a start,” Wagner, the NYU economist, said. The Paris targets aren’t stringent enough to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Wagner said oil companies support the tax because it’s “much too little” for the kind of change that’s needed.

“That is a very clear instance where the single-minded push for a carbon tax gets in the way of ambitious climate policy,” he said. “Why settle for what Exxon wants?”

We’re dependant on fossil fuels.

Just 20 fossil fuel companies — including Chevron, BP and Exxon Mobil — are responsible for a third of all global emissions since 1965. There is overwhelming evidence that ensuring a livable planet requires keeping fossil fuels in the ground, unextracted and unburned.

But fossil fuels are so integrated into our lives that phasing them out would require us to change everything about how and where we live, how we get around and how we make money. Fuel prices affect everyone, and while higher carbon prices help the environment, they can be passed on to consumers. The industry is quick to remind everyone of this of any time an environmental regulation comes up.

When California’s Air Resources Board held a hearing last year to discuss the maximum allowed permit price, dozens of speakers turned up to testify, including a group of black pastors from Los Angeles who’d advocated against oil and gas drilling in their communities. One by one, the pastors said the board proposal would hurt low-income, minority families.

The group was organized by the Rev. Jonathan Moseley Sr., who said he heard about the event from a contact at Prime Strategies, a consulting firm that gave him free updates on policy discussions in Sacramento. Moseley said Prime offered to fly the pastors to the hearing, and he believed the money came from a group called Californians for Affordable and Reliable Energy, or CARE.

He said he didn’t know CARE was funded by oil interests. CARE’s 2017 tax forms, the most recent available, show it raised $9 million that year. Nearly two-thirds of the money came from Chevron and WSPA, according to lobbying records. CARE also gave Prime Strategies $53,000 around the time of the hearing.

Robert Lapsley, the chairman of CARE, said the group represents business interests beyond oil and gas. It is led by the California Business Roundtable, a trade group for the state’s biggest companies. Lapsley said CARE advocates for regulators to consider how climate regulations affect consumer costs. CARE helped craft and lobby for the cap-and-trade extension and solicited funds from donors like WSPA who had similar goals, he said.

CARE’s public campaigns have used the images of blue-collar workers and people of color to argue against initiatives promoting electric cars and other efforts aimed at reducing fossil fuel consumption. Its homepage features a young man and woman studying a piece of paper. The description, according to a stock images website that sells the photo, is, in part, “African Millennial stressed married couple sitting on sofa at home checking unpaid bills.” The page also features a photo and quote from Bishop Lovester Adams, another pastor who testified before the board. Adams and Prime Strategies did not return requests for comment.

At the hearing, the Rev. Oliver Buie said, “I’m here to stand and speak for the community which I represent, which is a brown community, which is deeply injured whenever there’s any increase in any cost. … We need to look at the people more than the corporations.” But he, too, acknowledged he was unaware that oil interests effectively backed his Sacramento trip. “They didn’t tell us they were a wolf,” he said. “We thought they were a sheep.”

The board seemed puzzled by the resistance at the hearing and voted to maintain the maximum allowable price of nearly $100 a ton by 2030. The effort was mostly symbolic, as regulators assured the crowd they didn’t expect prices to get that high. Instead, Sahota, the assistant division chief, predicted it would hover at the minimum price for the next few years, but rise above it by 2030.

Cullenward said the reality of society’s reliance on fossil fuels leaves regulators in a bind — stuck between knowing what it will take to manage climate change but adopting a market solution that’s too weak by design. Any attempt to seriously strengthen it risks a consumer backlash that makes it “politically toxic,” he said.

“Essentially, what we’re doing is kicking the can,” Cullenward said. “We’re saying, keep prices low, let’s not do a lot, and later, we’ll hope for a miracle.”

Sophie Chou and Lexi Churchill contributed to this report.

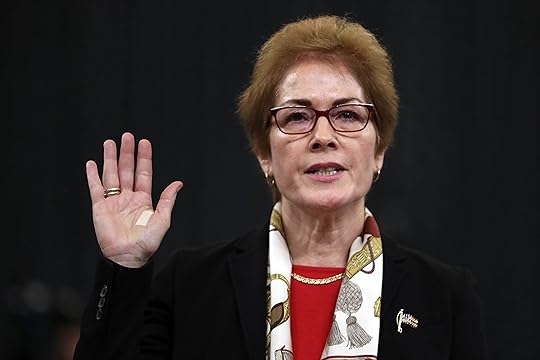

Yovanovitch Testifies for 5 Hours in House Probe

WASHINGTON — The Latest on President Donald Trump and House impeachment hearings (all times local):

3:22 p.m.

The second open House impeachment hearing is over.

Former U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Marie Yovanovitch testified for about five hours on Friday, telling investigators about her ouster in May at President Donald Trump’s direction and how she felt as she found out that he had criticized her in a July phone call with Ukraine’s president.

She also said it was “intimidating” as Trump went after her again on Twitter as she testified.

Related Articles

House Impeachment Panel Tables Motion to Subpoena Whistleblower

by

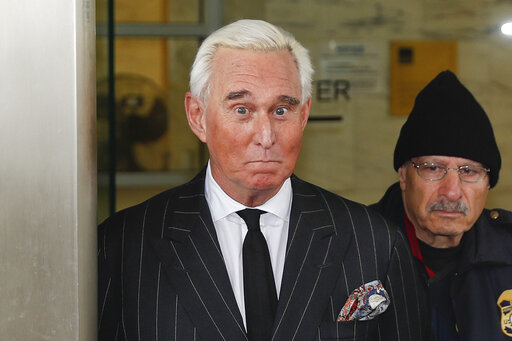

Roger Stone Guilty of Witness Tampering, Lying to Congress

by

Adam Schiff Accuses Trump of Witness Intimidation

by

Democrats are investigating Trump’s dealings with Ukraine and a shadow foreign policy there led by his lawyer, Rudy Giuliani. They said that Yovanovitch’s ouster set the stage for the president’s appeals to Ukraine’s leader to investigate Democrats.

The House Intelligence Committee will hear from eight more impeachment witnesses next week.

___

3 p.m.

President Donald Trump says he wasn’t trying to intimidate a witness in the House impeachment inquiry with his tweet and he’s entitled to speak his mind as the investigation plays out.

Trump says of impeachment, “it’s a political process, it’s not a legal process.” He says: “I’m allowed to speak up.”

Trump tweeted critically about Marie Yovanovitch, the former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine, as she was testifying Friday before the House Intelligence Committee.

Yovanovitch said she found Trump’s message “very intimidating” and Democratic committee chairman Adam Schiff suggested it could be used as evidence against the president. He said: “some of us here take witness intimidation very, very seriously.”

___

2:35 p.m.

The former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine says a political ally of President Donald Trump suggested she “send out a tweet, praise the president” when it became clear she was abruptly losing her job.

Marie Yovanovitch described her exchange with Gordon Sondland at the House impeachment hearing Friday. She says she rejected the advice.

Sondland was a Trump campaign contributor who’d become a State Department envoy to the European Union but wielded influence over U.S. policy in Ukraine.

Yovanovitch said Sondland’s advice was to “go big or go home,” which he explained meant lauding Trump.